Abstract

Introduction

Antiplatelet therapy combining aspirin and clopidogrel is considered to be a key intervention for acute ischaemic minor stroke (AIMS) and transient ischaemic attack (TIA). However, the interindividual variability in response to clopidogrel resulting from the polymorphisms in clopidogrel metabolism-related genes has greatly limited its efficacy. To date, there are no reports on individualised antiplatelet therapy for AIMS and TIA based on the genetic testing and clinical features. Therefore, we conduct this randomised controlled trial to validate the hypothesis that the individualised antiplatelet therapy selected on the basis of a combination of genetic information and clinical features would lead to better clinical outcomes compared with the standard care based only on clinical features in patients with AIMS or TIA.

Methods and analysis

This trial will recruit 2382 patients with AIMS or TIA who meet eligibility criteria. Patients are randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to pharmacogenetic group and standard group. Both groups receive a loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel on day 1, followed by 100 mg aspirin per day on days 2–365. The P2Y12 receptor antagonist is selected by the clinician according to the genetic information and clinical features for pharmacogenetic group and clinical features for the standard group on days 2–21. The primary efficacy endpoint is a new stroke event (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) that happens within 1 year. The secondary efficacy endpoint is analysed as the individual or composite outcomes of the new clinical vascular event (ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction or vascular death). Baseline characteristics and outcomes after treatment will be evaluated.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol has been approved by the ethics committee of Yangpu Hospital, Tongji University School of Medicine (No. LL-2018-KY-012). We will submit the results of this trial for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1800019911; Pre-results.

Keywords: personlized antiplatelet therapy, clopidogrel, pharmacogenomics, acute ischemic minor stroke, transient ischemic attack

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is a study to assess the efficacy and safety of individualised antiplatelet therapy selected on the basis of a combination of genetic information and a patient’s clinical features in patients with acute ischaemic minor stroke (AIMS) or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

The results from this randomised controlled trial will provide new evidence of the efficacy of individualised antiplatelet therapy on the basis of genetic information for AIMS or TIA.

This study will help clinicians predict and estimate the risk of clopidogrel resistance in patients with AIMS or TIA, and then take corresponding measures to reduce the risk of stroke recurrence.

The study is mainly focused on the CYP2C19 genotype (*2, *3 and *17 alleles), which might neglect the potential impact of other alleles.

The trial implementation is not multicentred and only Chinese population are included, which might limit its generalisability.

Introduction

Acute ischaemic minor stroke (AIMS) and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) are common cerebrovascular events with a high tendency to cause disability. Patients with AIMS or TIA have a high risk of subsequent ischaemic events, especially during the first 90 days after the cerebrovascular event.1 During this acute phase, there is still a risk of previous ischaemic tissue, with ruptured plaques in a state of high thrombus formation and high platelet activation, which may lead to more severe acute instability events.2 Therefore, antiplatelet therapy is considered to be a key intervention for AIMS and TIA at present.

Clopidogrel is one of the commonly used antiplatelet drugs in clinic, which is recommended for the secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke. The Clopidogrel in High-Risk Patients with Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (CHANCE) trial reported that compared with aspirin alone, the combination of clopidogrel with aspirin decreased the risk of stroke among patients with AIMS or TIA who can be treated within 24 hours after the onset of symptoms.3 However, there is interindividual variability in response to clopidogrel, which leads to the result that a large number of subsequent strokes still occur despite clopidogrel treatment and even among those treated with dual-antiplatelet agents.4 Compared with the inhibition of platelet aggregation expected, poor inhibition using antiplatelet therapy is referred to high on-treatment platelet reactivity (HPR).5 Those patients who show HPR to clopidogrel and are therefore at greater risk of ischaemic events are suffering from clopidogrel resistance.5 6 Clopidogrel resistance is an important cause of failure in the prevention and treatment of patients with partial ischaemic stroke, and will greatly increase the recurrence of ischaemic stroke. To date, the mechanisms related to variability in clopidogrel responsiveness are not fully elucidated.7

Mounting evidence has shown that genetic factors may play a crucial role in mediating clopidogrel resistance.8 As clopidogrel is a prodrug that requires hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP) for its conversion into an active metabolite,9 polymorphisms of its encoded gene CYP2C19 have been identified as strong predictors of clopidogrel non-responsiveness.10 Among them, CYP2C19 loss-of-function genotype (*2 and/or *3 alleles) is found to be related to low responsiveness to clopidogrel, which is a risk factor for ischaemic events, whereas the presence of gain-of-function CYP2C19 allele (*17) is associated with a high platelet inhibition and increased risk of bleeding.11 The genetic substudy of the CHANCE trial also showed that only in patients with AIMS or TIA who did not carry the CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles, the combined treatment of clopidogrel and aspirin could reduce the risk of a new stroke in comparison with aspirin alone.12 This study provided evidence to support the genetic testing that may allow clinicians to personalise antiplatelet therapy, especially in East Asian patient populations for whom the prevalence of CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele is high.12 13

To date, the clinical factors and genetic factors affecting clopidogrel responses have not reached a consistent conclusion. Besides, most of the study endpoints are cardiovascular events, and the research on cerebrovascular events is lacking. For example, Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines recommend that non-carriers of CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) continue to take clopidogrel 75 mg daily, and carriers are advised to increase the dose of clopidogrel or switch to other antiplatelet agents such as ticagrelor.14 Wallentin et al researched on the genetics of the CYP2C19 gene polymorphism in patients with ACS and found that compared with clopidogrel, treatment with ticagrelor significantly reduced the death rate from vascular causes in patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles.11 However, for patients with AIMS or TIA with clopidogrel resistance, it is unclear whether there will be a more clinical benefit when switching to ticagrelor. Based on the above, we conduct this randomised controlled trial (RCT) to validate the hypothesis that the individualised antiplatelet therapy selected on the basis of a combination of genetic information and a patient’s clinical features would lead to better clinical outcomes compared with the standard care based only on clinical features in patients with AIMS or TIA.

Method

Design

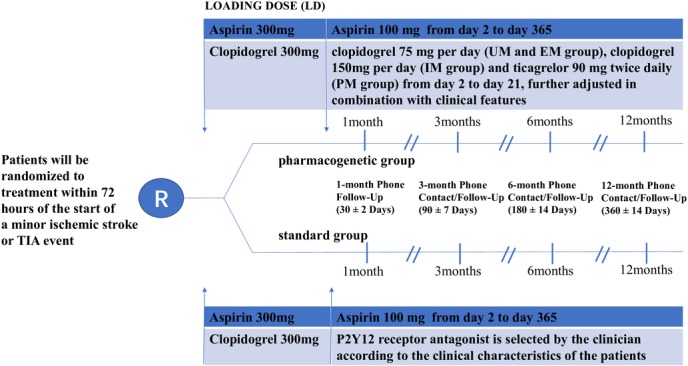

The design of study is shown in figure 1. The pharmacogenetics of clopidogrel in patients with AIMS or TIA study is a prospective, open-label RCT, aiming to evaluate whether selecting antiplatelet therapy (label recommended or doubled dosage of clopidogrel or ticagrelor) on the basis of a patient’s both genetic and clinical features leads to more clinical benefits compared with the standard care which bases selection only on clinical features. Collection and genetic analysis of samples are subjected to informed consent from all patients.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart. EM, extensive metabolisers; IM, intermediate metabolisers; PM, poor metabolisers; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; UM, ultra metabolisers.

Patient population

Patients are included into this study if they meet all the following criteria: (1) age of 18 years or older; (2) diagnosis of an AIMS or TIA; AIMS is defined as a sudden focal neurological dysfunction caused by vascular causes, and score of 3 or less at the time of randomisation on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (scores range from 0 to 42, with higher scores indicating greater deficits).3 TIA is defined as a transient episode of neurological dysfunction caused by focal brain, spinal cord or retinal ischaemia, without acute infarction15 and (3) onset of the AIMS or TIA symptoms less than 72 hours.

Patients are excluded from study participation if one of the following criteria is met:

(1)haemorrhage; other conditions, such as vascular malformation, trauma, tumour, abscess, degenerative neurological disease or other major non-ischaemic brain disease; (2) systemic infectious diseases, autoimmune diseases, severe heart, liver and kidney diseases; (3) any contraindication to the use of aspirin or P2Y12 receptor antagonists; (4) prior knowledge of the patients’ CYP2C19*2, CYP2C19*3 or CYP2C19*17 genotype; (5) ongoing treatment in another observational or registry randomised trial and (6) an inability to provide informed consent or unavailability for follow-up.

Based on the Platelet Inhibition and Patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial and Pharmacogenetics of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes (PHARMCLO) trial exclusion criteria, ticagrelor is contraindicated in patients: (1) with active pathological bleeding; (2) with a history of intracranial bleeding; (3) requiring dialysis, (4) taking oral anticoagulant therapy that could not be stopped; (5) with known clinically important thrombocytopaenia; (6) receiving fibrinolytic therapy within the previous 24 hours and (7) taking concomitant therapy with strong CYP3A inhibitors or inducers.16 17

Patients and public involvement

Patients in this trial will not be involved in the design, recruitment and conduction of the study. Clopidogrel genes of patients in pharmacogenetic group will be detected as soon as possible after the random assignment. The individual genetic information and the corresponding antiplatelet aggregation drug adjustment regimen will be disseminated to study participants as soon as possible after the gene detection. Satisfaction of the intervention and the burden of involvement in this RCT will be assessed as part of the evaluation.

Randomisation and treatments

Patients are consented and randomised in a 1:1 ratio to the pharmacogenetic or standard group as soon as feasible after the diagnosis of AIMS or TIA is made and no later 72 hours after initial symptom onset. A blood sample is obtained from every participant right after randomisation. Three single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) for CYP2C19 (National Center for Biotechnology Information Genome build 37.1, GenBank NG_008384), including CYP2C19*2 (681G>A, dbSNP rs4244285), CYP2C19*3 (636G>A, dbSNP rs4986893) and CYP2C19*17 (−806C>T, dbSNP rs12248560), are genotyped in the participants assigned to the pharmacogenetical strategy. Genotyping of the 3 SNPs is done at the Central laboratory of Yangpu Hospital Tongji University School of Medicine with microarray-based method (CapitalBio Technology). Patients are categorised by CYP2C19 metaboliser status based on *2, *3 and *17 genotypes within 24 hours of admission. And they are divided into four metabolite types: ultra metabolisers (UM, *1/*17, *17/*17), extensive metabolisers (EM, *1/*1), intermediate metabolisers (IM, *1/*2, *1/*3, *17/*2, *17/*3), poor metabolisers (PM, *2/*2, *2/*3, *3/ *3).

Both pharmacogenetic group and standard group receive a loading dose of 300 mg aspirin and 300 mg clopidogrel on day 1, followed by a dose of 100 mg of aspirin per day on days 2–365. Patients randomly assigned to the pharmacogenetic group receive a dose of 75 mg clopidogrel per day (UM and EM group), 150 mg clopidogrel per day (IM group) or ticagrelor 90 mg two times daily (PM group) on days 2–21, which can be further adjusted in combination with clinical features. While for standard group, the P2Y12 receptor antagonist is selected by the clinician according to the clinical features of the patients. The clinical features include age, weight, ischaemic risk, prior history of stroke/TIA, bleeding risk, intracranial bleeding, active bleeding, history of bleeding, anaemia, diabetes or chronic kidney disease.

Primary efficacy endpoint

The primary efficacy endpoint for this trial is a new stroke event (ischaemic or haemorrhagic) that happens within 1 year. Ischaemic stroke is defined as a sudden focal neurological dysfunction caused by vascular causes, duration ≥24 hours or neurological dysfunction due to imaging and clinical symptoms caused by bloody infarction rather than cerebral haemorrhage found by imaging examination. Haemorrhagic stroke is defined as acute extravasation of blood into the brain parenchyma or subarachnoid space with associated neurological symptoms.

Secondary efficacy endpoint

The secondary efficacy endpoint is analysed as the individual or composite outcomes of the new clinical vascular event (ischaemic stroke, haemorrhagic stroke, myocardial infarction or vascular death). The definition of vascular death is adapted from the CHANCE trial.3 Briefly, vascular death is defined as death resulting from stroke (ischaemic or haemorrhagic), systemic haemorrhage, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, sudden death or arrhythmia.

Safety assessments

Safety endpoint is a major bleeding event, according to the definitions in International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis18 and Platelet-Oriented Inhibition in New TIA and Minor Ischemic Stroke) Trial.19 Major haemorrhage is defined as symptomatic intracranial haemorrhage or intraocular bleeding causing loss of vision, requiring two or more units of red cells or equivalent amount of whole blood replacement, or requiring hospitalisation or prolongation of an existing hospitalisation, surgical intervention or death. An independent clinical event adjudication committee evaluates all components of the primary and secondary outcomes and safety endpoint.

Sample size

Based on data from the 1-year outcomes of the CHANCE trial with a primary endpoint (ischaemic or haemorrhagic stroke) rate of 10.6%,20 and considering that the time point when patients start to receive treatments in our study is later than that in the CHANCE trial, we estimate a higher incidence of primary efficacy endpoint in the standard group and define it as 15%. As we expect an absolute risk reduction of 5% in the pharmacogenomic group, so we define it as 10%. Given a 5% missed follow-up rate, 95% power and a two-sided type I error of 0.05, the calculated sample size is 1191 patients in each group.

Statistical analyses

The distributions of baseline characteristics are compared between two study groups using t-test. Proportions and χ2 test are used for categorical variables and continuous variables will be reported as median (IQR). Cox proportional hazard model is used to estimate the HR and 95% CIs relating to the primary and secondary outcomes. Schoenfeld residuals test is used to confirm the proportional hazards assumption for the Cox regression model. For estimating the cumulative incidence of endpoints during the 1-year follow-up, we perform the Kaplan-Meier analyses by means of Aalen-Johansen estimator. And, Fine-Gray model is used to test the significance of the differences between the subdistribution of the hazards. Values of p<0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Discussion

Currently, clopidogrel combined with aspirin has become the preferred short-term treatment for patients with AIMS or TIA for many clinicians.21 However, the pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel could be influenced by metabolic status. PM will cause insufficient antiplatelet effect and impaired clinical benefit.22 At present, the mechanisms of clopidogrel resistance are not fully elucidated and evidences from the genetic substudy of CHANCE trail showed the correlation between CYP2C19 polymorphisms with clopidogrel non-responsiveness. For patients with AIMS or TIA treated with clopidogrel and aspirin, CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles carriers were prone to have increased risk for subsequent stroke and composite vascular events compared with non-carriers.12 Although these genetic associations with clinical benefits have been widely replicated and the sample sizes are large enough to be predictive in the clinical setting, there are few examples using the pharmacogenetic data concerning clopidogrel metabolism to guide the clinical practice.23–25 Regarding to cardiovascular diseases, mounting evidence has shown that for patients with CYP2C19 loss-of-function alleles, obtaining genotype data early after percutaneous coronary intervention and thus making genotype-guided personalised antiplatelet therapeutic regimen could reduce risks for major adverse cardiovascular events.26 27 Thus, genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy may be regarded as a prospective alternative approach to personalised treatment in AIMS or TIA.

Given the fact that clopidogrel is currently the most widely used antiplatelet agent for AIMS or TIA with aspirin and there are indeed differences in reactivity among individuals, varying the dose of clopidogrel or shifting to new antiplatelet agents based on genetic data may be alternatives, but it has not been adequately evaluated.28 The ongoing Platelet Reactivity in Acute Non-disabling Cerebrovascular Events (PRINCE) study intends to investigate whether the combination of ticagrelor and aspirin is superior to the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in reducing the 90-day HPR for AIMS or TIA, especially for carriers of CYP2C19 loss-of-function allele.29 The interim results of PRINCE trial have shown that although ticagrelor could significantly reduce HPR better than clopidogrel, there were no significant differences between the two groups in reducing stroke and the composite endpoint events.30 More future randomised studies of genotype-guided antiplatelet therapy may be of value. Thus, this RCT will provide evidence for the assumption that using pharmacogenetic data to select P2Y12 receptor antagonists can be successfully incorporated into the clinical care of patients with AIMS or TIA. The selection of a P2Y12 receptor antagonist in our trial (label recommended or doubled dosage of clopidogrel or ticagrelor) is based on their pharmacogenetic data and individual clinical features in order to acquire the best trade-off between ischaemic events and bleeding complications. Furthermore, for the sake of racial and geographical differences in genetic factors, we will collect patients of AIMS or TIA from both Han and Uygur population in different regions of Shanghai and Xinjiang of China. The North-South differences make the participants more representative, ensuring the effectiveness of clinical trial. In addition, due to the fact that the clinical course of most patients in clinical practice is long, we appropriately expand the time of patient enrolment, so that it can be applied to more people in the future.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Chang Shan

(Department of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Shanghai Clinical Center for Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Rui-jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai Institute of Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases, Shanghai, China)

for her help in

revising the manuscript.

Footnotes

X-GZ and X-QZ contributed equally.

Contributors: LH and Y-HY conceived and designed this study. X-GZ, X-QZ, JX and Z-ZL wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. H-YJ and Y-HY refined the protocol. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This project is supported by Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (18411970100).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Collection and genetic analysis of samples are approved by ethics committee of Yangpu Hospital, Tongji University School of medicine (No. LL-2018-KY-012).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM. Oxford Vascular Study. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. BMJ 2004;328:326 10.1136/bmj.37991.635266.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Johnston SC. Clinical practice. Transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2002;347:1687–92. 10.1056/NEJMcp020891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med 2013;369:11–19. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mijajlovic MD, Shulga O, Bloch S, et al. Clinical consequences of aspirin and clopidogrel resistance: an overview. Acta Neurol Scand 2013;128:213–9. 10.1111/ane.12111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tantry US, Bonello L, Aradi D, et al. Consensus and update on the definition of on-treatment platelet reactivity to adenosine diphosphate associated with ischemia and bleeding. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:2261–73. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guirgis M, Thompson P, Jansen S. Review of aspirin and clopidogrel resistance in peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2017;66:1576–86. 10.1016/j.jvs.2017.07.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, et al. Variability in individual responsiveness to clopidogrel: clinical implications, management, and future perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1505–16. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.11.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Juth V, Holman EA, Chan MK, et al. Genetics as a molecular window into recovery, its treatment, and stress responses after stroke. J Investig Med 2016;64:983–8. 10.1136/jim-2016-000126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kazui M, Nishiya Y, Ishizuka T, et al. Identification of the human cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the two oxidative steps in the bioactivation of clopidogrel to its pharmacologically active metabolite. Drug Metab Dispos 2010;38:92–9. 10.1124/dmd.109.029132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med 2009;360:354–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wallentin L, James S, Storey RF, et al. Effect of CYP2C19 and ABCB1 single nucleotide polymorphisms on outcomes of treatment with ticagrelor versus clopidogrel for acute coronary syndromes: a genetic substudy of the PLATO trial. Lancet 2010;376:1320–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61274-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Zhao X, Lin J, et al. Association Between CYP2C19 Loss-of-Function Allele Status and Efficacy of Clopidogrel for Risk Reduction Among Patients With Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack. JAMA 2016;316:70–8. 10.1001/jama.2016.8662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kitzmiller JP, Groen DK, Phelps MA, et al. Pharmacogenomic testing: relevance in medical practice: why drugs work in some patients but not in others. Cleve Clin J Med 2011;78:243–57. 10.3949/ccjm.78a.10145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Scott SA, Sangkuhl K, Stein CM, et al. Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for CYP2C19 genotype and clopidogrel therapy: 2013 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013;94:317–23. 10.1038/clpt.2013.105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2009;40:2276–93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shuldiner AR, Palmer K, Pakyz RE, et al. Implementation of pharmacogenetics: the University of Maryland Personalized Anti-platelet Pharmacogenetics Program. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 2014;166C:76–84. 10.1002/ajmg.c.31396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Notarangelo FM, Maglietta G, Bevilacqua P, et al. Pharmacogenomic Approach to Selecting Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: The PHARMCLO Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1869–77. 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schulman S, Kearon C. Subcommittee on Control of Anticoagulation of the Scientific and Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in non-surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost 2005;3:692–4. 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01204.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Johnston SC, Easton JD, Farrant M, et al. Platelet-oriented inhibition in new TIA and minor ischemic stroke (POINT) trial: rationale and design. Int J Stroke 2013;8:479–83. 10.1111/ijs.12129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang Y, Pan Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel With Aspirin in Acute Minor Stroke or Transient Ischemic Attack (CHANCE) Trial: one-year outcomes. Circulation 2015;132:40–6. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.014791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:2160–236. 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmes MV, Perel P, Shah T, et al. CYP2C19 genotype, clopidogrel metabolism, platelet function, and cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;306:2704–14. 10.1001/jama.2011.1880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Peterson JF, Field JR, Unertl KM, et al. Physician response to implementation of genotype-tailored antiplatelet therapy. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2016;100:67–74. 10.1002/cpt.331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price MJ, Berger PB, Teirstein PS, et al. Standard- vs high-dose clopidogrel based on platelet function testing after percutaneous coronary intervention: the GRAVITAS randomized trial. JAMA 2011;305:1097–105. 10.1001/jama.2011.290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cavallari LH, Weitzel KW, Elsey AR, et al. Institutional profile: University of Florida Health Personalized Medicine Program. Pharmacogenomics 2017;18:421–6. 10.2217/pgs-2017-0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cavallari LH, Lee CR, Beitelshees AL, et al. Multisite Investigation of Outcomes With Implementation of CYP2C19 Genotype-Guided Antiplatelet Therapy After Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2018;11:181–91. 10.1016/j.jcin.2017.07.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kheiri B, Abdalla A, Osman M, et al. Personalized antiplatelet therapy in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A network meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2019. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28075 [Epub ahead of print 10 Jan 2019]. 10.1002/ccd.28075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roberts JD, Wells GA, Le May MR, et al. Point-of-care genetic testing for personalisation of antiplatelet treatment (RAPID GENE): a prospective, randomised, proof-of-concept trial. Lancet 2012;379:1705–11. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60161-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wang Y, Lin Y, Meng X, et al. Effect of ticagrelor with clopidogrel on high on-treatment platelet reactivity in acute stroke or transient ischemic attack (PRINCE) trial: Rationale and design. Int J Stroke 2017;12:321–5. 10.1177/1747493017694390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang Y, Meng X, Chen W, et al. Ticagrelor with Aspirin on Platelet Reactivity in Acute Nondisabling Cerebrovascular Events (PRINCE) Trial--Final Analysis. International Stroke Conference, 2018. https://www.wesrch.com/medical/pdfME1XXF000PAZG [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.