Abstract

Introduction

Physically active cancer survivors have substantially less cancer recurrence and improved survival compared with those who are inactive. However, the majority of survivors (70%–90%) are not meeting the physical activity (PA) guidelines. There are also significant geographic inequalities in cancer survival with poorer survival rates for the third of Australians who live in non-metropolitan areas compared with those living in major cities. The primary objective of the trial is to increase moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) among cancer survivors living in regional and remote Western Australia. Secondary objectives are to reduce sedentary behaviour and in conjunction with increased PA, improve quality of life (QoL) in non-metropolitan survivors. Tertiary objectives are to assess the effectiveness of the health action process approach (HAPA) model variables, on which the intervention is based, to predict change in MVPA.

Methods and analysis

Eighty-six cancer survivors will be randomised into either the intervention or control group. Intervention group participants will receive a Fitbit and up to six telephone health-coaching sessions. MVPA (using Actigraph), QoL and psychological variables (based on the HAPA model via questionnaire) will be assessed at baseline, 12 weeks (end of intervention) and 24 weeks (end of follow-up). A general linear mixed model will be used to assess the effectiveness of the intervention.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval has been obtained from St John of God Hospital Subiaco (HREC/#1201). We plan to submit a manuscript of the results to a peer-reviewed journal. Results will be presented at conferences, community and consumer forums and hospital research conferences.

Trial registration number

ACTRN12618001743257; pre-results, U1111-1222-5698

Keywords: cology, wearable technology, physical activity, health coaching, intervention.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The intervention has the potential to be a low-cost and scalable and hence, integrated into existing healthcare pathways.

An objective measure of physical activity (PA) is used to provide accurate assessment of PA.

Due to the postal nature of recruitment, the responders may not be a representative sample of regional and remote cancer survivors.

The relatively short follow-up period limits our assessment of the extended acceptance of wearable technology in this population.

Introduction

Compared with the general population, cancer survivors are at an increased risk of the development of secondary cancers, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and functional decline.1 2 There are several possible explanations for the increased risk, one of which is shared lifestyle risk factors.3 Insufficient physical activity (PA), low fruit and vegetable intake, smoking and alcohol consumption make individuals susceptible to cancer recurrence, CVD and other chronic diseases.3

The American Cancer Society PA guidelines for survivors are to participate in 150 min of moderate-to-vigorous intensity PA per week.4 However, the majority of Australian survivors (~70%–90%) do not meet the PA recommendations.5

PA is associated with lower CVD-related comorbidity in survivors.2 Physically active survivors have significantly less cancer recurrence and improved survival compared with those who are inactive, and these findings have been found across multiple cancer types.6 7 Many survivors suffer additional comorbidities that put them at risk of developing CVD.8 As a result, insufficiently active survivors (ie, those not meeting the PA guidelines) who fail to make healthy lifestyle changes post-treatment are likely to have substantially higher risk of developing CVD.

Together, colorectal, breast, prostate and uterine cancer account for 41% of all cancer incidence in Western Australia.9 Our rationale for targeting survivors of these cancers is based on established risk or comorbid cardiometabolic disease, and a high prevalence of physical inactivity.10

There are also substantial geographic inequalities in cancer survival.8 11 Survival rates for Australians who live in non-metropolitan areas are poorer than for those living in major cities.12 Those living in remote areas of Australia are often disadvantaged in relation to access to services, education, employment and income. Mortality rates for all cancers combined are 1.4 times higher in remote areas compared with major cities.12

Existing PA programmes for survivors tend to be based in major cities but rarely operate beyond the inner regional areas. Further, facility-based programmes that are offered for free initially, eventually incur a cost that may present a barrier to long-term exercise adherence. Previous work with survivors has identified cost, and availability of and access to exercise programmes to be significant barriers to participation.13–15 Survivors have also expressed a preference for home-based PA.13 15 16

Home-based interventions are advantageous because they mitigate access and transport issues, and are less expensive than facility-based programmes that require participants to attend classes or maintain a health club membership.17 There is a current gap in the literature on the effectiveness of less intensive home-based interventions that could more easily translate into practice. A further novel component of the present study is the specific targeting of underserved regional and remote survivors with a home-based intervention. If effective, the intervention would be low cost and has the potential to be scalable and could be integrated into existing healthcare pathways.

Notwithstanding the obvious advantages of home-based interventions, a recent review and meta-analysis revealed only a small effect (standardised mean difference) 0.21 for distance-based PA interventions.18 However, most of the studies included in the review relied on self-reported PA. Further, most interventions predominantly utilised print and telephone modes of delivery. Few interventions used electronic health platforms or smart technology such as wearables. Distance-based interventions in survivors who utilise wearables show promise with a recent trial revealing a between group difference in moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) of 103 min/week favouring the intervention group.19

Interventions that meet support needs and offer opportunities for self-monitoring have been found to be effective in improving PA in survivors.20–22 Wearable technology holds great potential as a low-cost self-monitoring tool to increase PA in cancer survivors. Lyons et al 23 recently reviewed 13 different wearables and their associated mobile apps, and concluded that they use many of the same techniques employed in typical PA interventions (ie, self-monitoring, feedback, goal setting, social support). Wearables are perceived as useful and acceptable to individuals with chronic conditions.24 Wearables are acceptable to older cancer survivors in metropolitan areas25 and those living in regional and remote areas.26 Thus, wearables may represent a relatively low-cost, feasible and scalable approach for widespread PA promotion.

The primary aim of the study is to increase PA in adult cancer survivors residing in regional and remote areas in Australia. Secondary objectives are to reduce sedentary behaviour and in conjunction with increased PA, improve quality of life (QoL) in non-metropolitan survivors. Tertiary objectives are to assess the effectiveness of the health action process approach (HAPA) model variables, on which the intervention is based, to predict change in PA.

Methods and analysis

Study design

A randomised controlled parallel group design will be employed. Participants will be randomised into one of two arms: control versus intervention, and assessments will be made at baseline (T1), end of intervention (12 weeks) (T2) and at 24 weeks (T3). The outcome (dependent) measures will include an objective measure of PA, sedentary behaviour, QoL, plus measures that indicate constructs from the HAPA model27 such as action self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, action planning and maintenance self-efficacy on which the intervention is designed. We will also measure a number of covariates that may influence effects of the intervention including age, gender, socioeconomic status, cancer type, months since diagnosis, disease stage, adjuvant treatment and CVD risk factors. The trial will comply with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials and Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT).28 29 A completed SPIRIT checklist for the trial can be found in supporting information.

Setting and participants

Participants will be cancer survivors diagnosed with cancer and completed active treatment in the previous 5 years. Participants will reside in Australia and will have been treated for either breast, prostate, colorectal or uterine cancer. Participants will be recruited on the basis of (1) remoteness and (2) low levels of PA. Remoteness will be measured according to the accessibility/remoteness index of Australia and the Australian Statistical Geography Standard which define five major areas: major cities, inner regional, outer regional, remote and very remote.30 Participants will be recruited on the basis that they reside in either a regional or remote area. Eligible participants must also be (1) insufficiently physically active (ie, engaging in <150 min of moderate-intensity or 75 min of vigorous-intensity PA per week),4 31 (2) aged between 18 and 80 years, (3) proficient in English-reading and speaking, (4) have no known presence of cancer at the time of recruitment and (5) have internet access at home. Exclusion criteria include individuals who (1) are still undergoing treatment for cancer except for maintenance therapy such as tamoxifen, (2) have known cardiac abnormalities including unstable angina or recent myocardial infarction, (3) have any severe disability that may affect physical function including severe arthritis, (4) have a current diagnosis of a severe psychiatric illness (those with minor psychiatric diagnoses will be eligible if they are well enough to participate) and (5) are currently enrolled in a health behaviour trial or programme.

Recruitment

Participants will be recruited using purposive sampling methods, involving screening the hospital records of participating oncologists, to collate a pool of eligible survivors. The preliminary participating oncologists are based at St John of God Subiaco and Murdoch Hospitals, Hollywood Private Hospital, the Women Centre in West Leederville. Oncologists in South Australia, Victoria and New South Wales may also participate in the trial depending on recruitment uptake. Eligible individuals will be mailed an invitation letter and information sheet from their treating oncologist.

Intervention

The 12-week intervention includes two components: (1) a Fitbit Charge 2 activity tracker providing real-time monitoring and feedback on PA, (2) up to six sessions of health coaching (four fixed sessions) via skype/facetime/and so on or phone depending on participant preferences.

WAT tracker

Participants will be provided with a Fitbit Charge 2 activity tracker. This is a slim, wrist-worn device that displays steps, distance, heart rate, active minutes (MVPA) and provides automated prompts which nudge participants to accumulate at least 250 steps/hour. The Fitbit Charge 2 was chosen because previous work demonstrates its usefulness and acceptance among survivors25 26 and older adults (>70 years).32 Data from the device can be uploaded to the Fitbit application via Bluetooth. Participants will receive clear and simple written instructions guiding the installation of apps and device usage. Technical support will also be provided through follow-up calls to maximise uptake.

Health coaching

The purpose of the health coaching is to motivate and support increased PA (ie, deliberate bouts of MVPA) and reduced sedentary behaviour through supporting self-efficacy, action planning and problem solving, based on the principles of the HAPA. The health coaching is important to help guide action planning and problem solving since these behaviour change techniques are absent from the apps associated with wearable devices.23 Telephone health coaching has been successfully used in Australian and US survivors to increase PA.5 33 The first session (week 1; ~60 min) will cover technical issues and the features of the Fitbit, including the importance of MVPA. It will also foster positive outcome expectancies and confidence towards PA and guide the participant to create PA action plans for the following 3 weeks and self-monitor their activity. The purpose of the three follow-up health-coaching sessions (week 2, 4 and 8; ~30 min each) will be to provide support, problem solving and help the participant to update goals and action plans as they progress. We will adopt a patient-centred and stepped-care approach by providing additional health-coaching sessions (ie, at week 6 and 10) to those who may need them in order to achieve meaningful sustained PA change. Additional health-coaching sessions will be negotiated between the health coach and the participant, and will be based on both data from the Fitbit dashboard concerning progress and participants’ perceptions concerning support needs. Additional sessions will be negotiated during the previous follow-up call. The weekly exercise target will be at least 180 min of moderate-intensity PA, based on research demonstrating better survival in patients who engaged in 3–5 hours of moderate activity per week.7 20 A web-based application programming interface (API) to collect user’s activity data from the Fitbit server will be developed. On user consent via Fitbit authentication page, we will be able to collect participants' daily activity (step count, active minutes, hourly activity, heart rate, stairs climbed). The health coach will log hourly activity (accumulation of 250 steps/hour), step count, active minutes (MVPA bouts of at least 10 min) for each participant on a weekly basis. The health coach will also review weekly activity and engagement via the Fitbit app prior to each health-coaching session to provide feedback, encouragement and technical support if needed. API monitoring will cease at the end of the trial (after 24 weeks) and a deauthorisation email sent to participants to confirm the end of API participation.

Quality assurance

The health coach employed to deliver the intervention will be required to have a background in psychology or allied health discipline (at least to degree level). The health coach will undertake training including the theoretical bases of the intervention, PA messaging and implementation of behaviour change techniques. Training will include role plays with supervised feedback. Health-coaching consistency will be achieved by following a semistructured script with a clear structure of questions, and behaviour change techniques to be covered in each call. Competency and quality control will be monitored by direct observation and/or audio recordings (with feedback to the health coach) and will continue until consistent and adequate health-coaching performance is confirmed. All telephone calls to participants will be audiotaped.

Procedure

Participants will be sent an invitation letter, information sheet, consent form (supplementary file, appendix A) and a reply paid envelope from their treating surgical, medical or radiation oncologist. On receipt of written consent, participants will be telephoned and an initial screening questionnaire (including the Active Australia Survey; AAS34 to assess PA status) administered to determine eligibility. The AAS has demonstrated acceptable convergent validity for community-dwelling older adults.35 Only those who report participating in <150 min of MVPA per week will be eligible to participate in the trial.

bmjopen-2018-028369supp001.pdf (177.4KB, pdf)

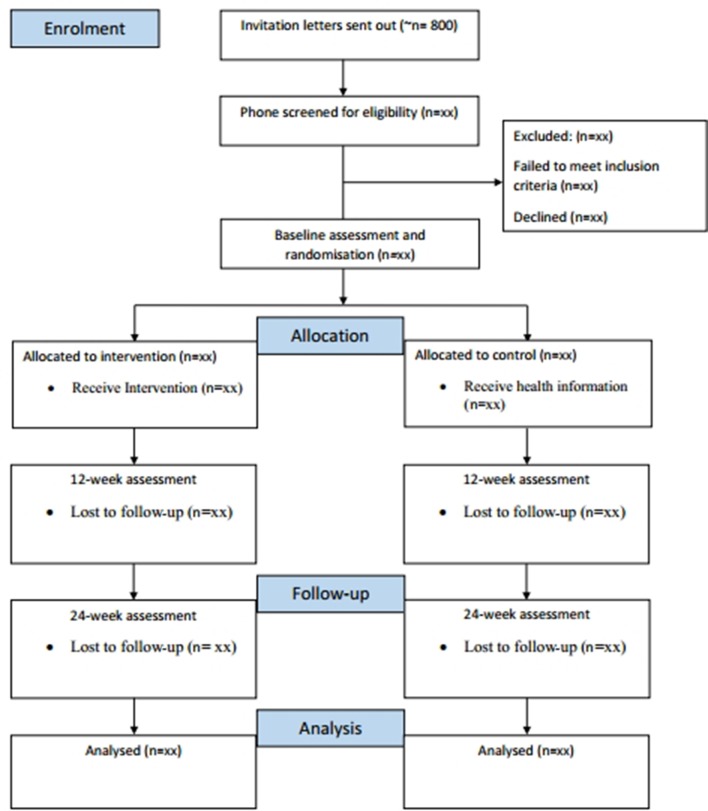

If the criteria are met, participants will be mailed the study questionnaire, an Actigraph GTX9 accelerometer, written accelerometer instructions and a reply paid envelope. Participants will be asked to complete the questionnaire and wear the accelerometer on their right hip for 7 days during waking hours, and then return the questionnaire and accelerometer in the reply paid envelope. Figure 1 represents the flow of research participants through the trial.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of trial design.

The statistician will generate the randomisation sequence using STATA V.15 with a 1:1 allocation using random block sizes of 4 and 6 to support allocation concealment. Participant allocation will be implemented using sequentially numbered, opaque sealed envelopes and the researchers involved in assessing and enrolling participants will not be involved in the generation of the randomisation sequence. Following consent and baseline assessment, the trial coordinator will choose the next envelope in the sequence and write the participant study number onto the envelope prior to allocating the participant to that group. Carbon paper inside the envelope will transfer the number onto the card containing the details of allocation.

The trial coordinator will post the accelerometers to participants with clear instructions on how to use them, and will contact participants after the 7 days to remind them to post them back to the researchers. Participants will also complete questionnaires that measure sociodemographic variables, QoL and HAPA model constructs.27

Both the control and intervention group will receive a mailed booklet designed to educate and motivate improvements in PA. Materials will be based on the current guidelines for PA31 and include examples of home-based strength exercises and a guide to exercise intensity. The control group will receive minimal intervention to mimic usual care so that we are able to compare the effects of the intervention to usual care. The booklet provided: ‘exercise for people living with cancer’ is freely available from Cancer Council Australia and may be found in oncology reception areas, and as such, may be considered to represent usual care.

After 12 weeks, participants in both groups will complete a questionnaire that measures variables from the HAPA, QoL and psychosocial variables again for a second time and wear an accelerometer for a 7-day period. The trial coordinator will post out the accelerometers and questionnaires. Between 12 and 24 weeks, participants will keep the Fitbit but there will be no further health coaching. At 24 weeks, all participants will complete the questionnaires for a third time and will receive an accelerometer to wear for a 7-day period. All Fitbits will be returned after the 24-week assessment alongside the accelerometer. Following trial completion (T3), participants in the control group will be offered the opportunity to trial a Fitbit for 12 weeks.

Measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome will be minutes of MVPA and sedentary behaviour ascertained from the Actigraph GT9X (Actigraph, LLC, Pensacola, Florida, USA). Participants will be mailed the accelerometer and instructed to wear on their right hip for all waking hours for 1 week at baseline, 12 weeks and 24 weeks. Wear time must exceed 10 hours/day to be considered valid for analysis. Non-wear periods will be defined as intervals of at least 60 consecutive minutes of zero counts will be excluded from analyses. Activity counts will be categorised as: sedentary (<100 cpm), light-intensity (100–1951 cpm), moderate-intensity (1952–5724 cpm) and vigorous-intensity (>5725 cpm), using data recorded in 60 s epochs, according to Freedson cut points.36 MVPA will be examined as both weekly time accumulated (minutes/week), and time in bouts of 10 consecutive minutes (minutes/week).

Sedentary behaviour

Sedentary behaviour will be defined by accelerometer activity counts of <100 cpm, for 20 consecutive minutes or more, which corresponds to clinical changes in cardiometabolic biomarkers.37 The accelerometer log completed will assist in differentiating sedentary time from non-wear time.

Quality of life

QoL will be measured using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, QoL Core Questionnaire (QLQ-C30)38 The QLQ-C30 is a feasible, reliable and a valid questionnaire and is used in clinical trials of cancer worldwide.38–40 It includes five function domains (physical, emotional, social, role, cognitive), eight symptoms (eg, fatigue, pain) in addition to global health/QoL.

PA attitudes

PA attitudes will be assessed using previously validated items, with Cronbach’s alpha scores for the subscales below ranging from 0.73 to 0.87.41 Some items have been amended, based on previous formative work in survivors,13 16 42 43 and PA recommendations.4 All items are assessed using a 6-point Likert scale. The following constructs will be assessed.

Outcome expectations

Twelve items will assess outcome expectations. Five items are derived from the validated exercise pros subscale44 and seven items are based on formative research with survivors.14 42 43 The items measure magnitude that regular PA will help to reduce tension or stress, feel more confident about my own health, sleep better, have a positive outlook, control my weight, regain lost strength, prevent cancer recurrence, increase fatigue, increase joint pain, weaken my immune system, feel better about my body and increase my longevity.

Action self-efficacy

Four items will assess action self-efficacy, based on previous research with survivors.45 Items assess participants’ confidence to complete 150 min of MVPA per week, with the item stems: ‘I believe I have the ability to…’; ‘I am confident I can do…’; ‘If I wanted to I could…’ and ‘For me to do…’.

Maintenance self-efficacy

Thirteen items will assess maintenance self-efficacy, based on formative research.14 43 Items assess confidence to participate in regular MVPA over the next 12 weeks when, for example, I lack discipline, and I am feeling tired.

Action planning

Four items will assess action planning for the next 3 weeks.46 Participants will be asked to respond about whether they have made plan concerning what, when, where and how they will engage in regular PA.

Intention

Two items will measure intention to engage in MVPA for at least 150 min/week in the next 12 weeks, based on previously established measures.47 Items are ‘I intend to participate…’ and ‘I will try to participate…’.

Covariates

Sociodemographic information and CVD risk factors will be self-reported. The following variables will be assessed: marital status, educational attainment, gross household income and smoking status. Comorbidity will be assessed using the self-administered comorbidity questionnaire.48

Power calculations and sample size

The primary outcome is change in MVPA at T2. A sample size of 86 participants (43 in each arm) is required in order to achieve 80% power to detect a group (control vs intervention) by time (T1 vs T2) interaction at 0.05 level. Our calculations are based on the covariance matrix from a previous wearable technology trial in survivors using accelerometers to assess MVPA49 assuming a 70 min increase in MVPA at T2 in the intervention group, but no change in the control arm. We aim to recruit 100 participants, ensuring that if 15% are lost to follow-up, the intervention will still be adequately powered at 80% to detect a meaningful change.

Patient and public involvement

We have published several papers13–16 from qualitative work with consumers. Such consumer engagement has informed the present intervention. For example, this work has identified ‘poor self-discipline’ and ‘not the sporty type’ as the main PA barriers. Some participants held the perception that they were already ‘doing sufficient PA’. Participants also referred to the need for monitoring, support and accountability to help them in their behaviour change efforts. These findings have fed into the design of the intervention in the following ways: the promotion of lifestyle-related exercise such as walking takes away the ‘sporty type’ barrier; the use of wearables to provide objective feedback on PA can be helpful for those who erroneously think they are undertaking sufficient PA; and the use of wearables and health-coaching provides the self-monitoring, and support that consumers have identified as important. Consumers who have trialled the wearable trackers have reported the intervention to be acceptable and not burdensome.26 Study participants will be asked whether they wish to receive a report of the results, and asked to provide an email address for dissemination of study results.

Data management

All personal data collected will be stored in accordance with the Data Protection Act and applicable regulatory requirements and access to deidentified data will be available on request. Data will be stored securely to maintain confidentiality. To preserve participant anonymity, only allocated trial numbers will be recorded on trial documentation or computer software except for the consent form and contact details. Documents with identifiable information will be stored separately to other study documents. Pseudonyms will be used when reporting findings from the process evaluation.

Data monitoring and timeline

The trial will be overseen by the trial management group, consisting the principal investigator, the trial coordinator and health coach. The trial management group will oversee all aspects of the conduct of the trial including performing safety oversight activities and will meet every 4 weeks. Any significant adverse events will be reported to the human research ethics committee (HREC) within 72 hours, and managed by the HREC alongside the principal investigator (SH). The principal investigator will keep an audit trail and maintain responsibility for the trial including conduct and management of the trial. Recruitment is expected to commence in Februry 2019 and the project completed by December 2020.

Data analysis

The effectiveness of the intervention versus control on MVPA/week will be assessed using a linear mixed model, with group (intervention vs control), time (T1 vs T2) and their interaction as fixed effects, and with a random effect for participant included to account for the correlations in observations inherent in a repeated measures design. Secondary adjusted models will include age, gender, baseline PA level, adjuvant therapy, cancer type, months since diagnosis and intervention dose (number of health-coaching sessions received) as covariates. Between-group comparisons will be performed for all secondary outcomes (sedentary behaviour, other PA and psychological variables, QoL) and HAPA constructs using mixed models, including adjustment for confounding where appropriate. Missing data will be investigated for patterns in terms of observed study variables. Multiple imputation will be considered if data are arguably missing at random and <20% of the data are missing. We will impute 25 datasets based on all relevant observed variables, including the interaction term and outcome measure of interest for each specific analysis. Sensitivity analyses will be conducted to consider the effect of potential missing not at random mechanisms on parameter estimates from imputed datasets. Intention-to-treat analysis will be conducted where there is participant attrition. Appropriate longitudinal mediation models will be used to investigate whether (1) intervention associated changes in MVPA are mediated (at least partially) via the HAPA model and (2) changes in QoL are partially mediated via changes in MVPA. All data will be analysed with p<0.05 considered significant.

Process evaluation

Acceptability and feasibility of the intervention will form the process evaluation. Feasibility of the intervention will be evaluated by comparing intervention costs (intervention equipment, staff time) with uptake rates, adherence (to wearing the wearable tracker, receipt of health-coaching sessions) and completion. Acceptability and utility of the intervention, and an understanding of the active ingredients will be examined using semistructured interviews.

Discussion

The trial will assess the effectiveness of an intervention that combines wearable technology with behaviour change techniques (action planning, goal setting and coping planning, feedback) to increase MVPA and reduce sedentary behaviour in cancer survivors living in non-metropolitan areas of Australia. This protocol describes one of the first trials using wearable technology to promote PA in non-metropolitan survivors, contributing to research on the effectiveness of distance-based interventions to promote PA.

Despite increasing evidence that PA reduces the risk of CVD and cancer recurrence,6 50 few survivors meet the PA guidelines.4 Furthermore, there are significant geographic inequalities in cancer survival that urgently need to be addressed, with significantly poorer survival in rural areas compared with major cities. Existing PA programmes for survivors tend to be based in major cities with scarce provision outside of major cities. Less intensive home-based interventions could be more acceptable to consumers, scalable and more cost-effective.

Conclusion

The trial is pragmatic and primarily concerned with evaluating whether a low-intensity, distance-based intervention is effective for increasing MVPA and reducing sedentary behaviour in survivors. If effective, the intervention, that employs resource deployment according to patient need, would be low-cost and scalable, and could be integrated into existing healthcare pathways.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the consumers who have kindly given their time to participate in our previous projects that have contributed to the design of the prospective intervention.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH led the study conceptualisation, development of intervention content and writing of the protocol. GM, PT, SS, JT, GRM, ML, PAC, CS and CP contributed to study conceptualisation and will recruit patients for the trial. RJ-C edited the protocol and will assist in the process evaluation. TB and VC contributed to physical activity measurement protocol and will be responsible for Actigraph data cleaning and analysis. DH contributed to statistical analysis and the process for randomisation and data management and will undertake data analysis. All authors edited the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from The Tonkinson Colorectal Cancer Research Foundation (Grant reference #59395).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was obtained from the St John of God Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (#1201), and reciprocal approval will be approved from other participating hospitals and sites.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Baade PD, Frischi L. & Eakin E. Non-cancer mortality among people diagnosed with cancer. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:287–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Keats MR, Cui Y, Grandy SA, et al. . Cardiovascular disease and physical activity in adult cancer survivors: a nested, retrospective study from the Atlantic PATH cohort. J Cancer Surviv 2017;11:264–73. 10.1007/s11764-016-0584-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, et al. . Nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56:323–53. 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. . Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:242–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hawkes AL, Chambers SK, Pakenham KI, et al. . Effects of a telephone-delivered multiple health behavior change intervention (CanChange) on health and behavioral outcomes in survivors of colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:2313–21. 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.5873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Friedenreich CM, Neilson HK, Farris MS, et al. . Physical Activity and Cancer Outcomes: A Precision Medicine Approach. Clin Cancer Res 2016;22:4766–75. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li T, Wei S, Shi Y, et al. . The dose-response effect of physical activity on cancer mortality: findings from 71 prospective cohort studies. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:339–45. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Weaver KE, Foraker RE, Alfano CM, et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors among long-term survivors of breast, prostate, colorectal, and gynecologic cancers: a gap in survivorship care? J Cancer Surviv 2013;7:253–61. 10.1007/s11764-013-0267-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Threlfall TJ, Thompson JR. Cancer incidence and mortality in Western Australia, 2014 Department of Health, Western Australia, Perth. Statistical Series Number 103.. Perth, WA: Department of Health, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Leach CR, Weaver KE, Aziz NM, et al. . The complex health profile of long-term cancer survivors: prevalence and predictors of comorbid conditions. J Cancer Surviv 2015;9:239–51. 10.1007/s11764-014-0403-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tervonen HE, Aranda S, Roder D, et al. . Cancer survival disparities worsening by socio-economic disadvantage over the last 3 decades in new South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health 2017;17:691–702. 10.1186/s12889-017-4692-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australians’ health. Canberra: AIHW, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hardcastle SJ, Glassey R, Salfinger S, et al. . Factors influencing participation in health behaviors in endometrial cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017;26:1099–104. 10.1002/pon.4288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hardcastle SJ, Maxwell-Smith C, Zeps N, et al. . A qualitative study exploring health perceptions and factors influencing participation in health behaviors in colorectal cancer survivors. Psychooncology 2017;26:199–205. 10.1002/pon.4111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hardcastle SJ, Maxwell-Smith C, Kamarova S, et al. . Factors influencing non-participation in an exercise program and attitudes towards physical activity amongst cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1289–95. 10.1007/s00520-017-3952-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maxwell-Smith C, Zeps N, Hagger MS, et al. . Barriers to physical activity participation in colorectal cancer survivors at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Psychooncology 2017;26:808–14. 10.1002/pon.4234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hardcastle SJ, Cohen PA. Effective Physical Activity Promotion to Survivors of Cancer Is Likely to Be Home Based and to Require Oncologist Participation. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3635–7. 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.6032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Groen WG, van Harten WH, Vallance JK. Systematic review and meta-analysis of distance-based physical activity interventions for cancer survivors (2013-2018): We still haven’t found what we’re looking for. Cancer Treat Rev 2018;69:188–203. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hartman SJ, Nelson SH, Myers E, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of increasing physical activity on objectively measured and self-reported cognitive functioning among breast cancer survivors: The memory & motion study. Cancer 2018;124:192–202. 10.1002/cncr.30987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, et al. . Randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical activity intervention in breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2016;16:234–47. 10.1186/s12885-016-2258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. James E, Stacey F, Chapman K, et al. . Impact of a nutrition and physical activity intervention (ENRICH) on health behaviours of cancer survivors and carers: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2015;15:710–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Anton PM, et al. . Social cognitive constructs did not mediate the cancer intervention effects on objective physical activity behaviour based on multivariate path analysis. Ann Beh Med 2017;51:321–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lyons EJ, Lewis ZH, Mayrsohn BG, et al. . Behaviour change techniques implemented in electronic lifestyle activity monitors: A systematic content analysis. Journal Med Internet Res 2014;16:e192–e206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mercer K, Giangregorio L, Schneider E, et al. . Acceptance of commercially available wearable activity trackers among adults aged over 50 and with chronic illness: A mixed-methods evaluation. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e7 10.2196/mhealth.4225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nguyen NH, Hadgraft NT, Moore MM, et al. . A qualitative evaluation of breast cancer survivors' acceptance of and preferences for consumer wearable technology activity trackers. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:3375–84. 10.1007/s00520-017-3756-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hardcastle SJ, Galliott M, Lynch BM, et al. . Acceptability and utility of, and preference for wearable activity trackers amongst non-metropolitan cancer survivors. PLoS One 2018;13:e0210039 https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0210039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy in the adoption and maintenance of health behaviours: Theoretical approaches and a new model Schwarzer R, Self-efficacy: Thought control of action. Washington, DC: Hemisphere, 1992:217–42. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. . Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276:637–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. . SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann Intern Med 2013;158:200–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Australian Statistical Geography Standard. Volume 5- Remoteness structure. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Department of Health. Australia’s physical activity and sedentary behavior guidelines. Canberra: Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 32. McMahon SK, Lewis B, Oakes M, et al. . Older adults’ experiences using a commercially available monitor to self-track their physical activity. J Med Internet Res 2016;4:e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, et al. . Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;132:205–13. 10.1007/s10549-011-1882-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brown WJ, Burton NW, Marshall AL, et al. . Reliability and validity of a modified self-administered version of the Active Australia physical activity survey in a sample of mid-age women. Aust N Z J Public Health 2008;32:535–41. 10.1111/j.1753-6405.2008.00305.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Heesch KC, Hill RL, van Uffelen JG, et al. . Are Active Australia physical activity questions valid for older adults? J Sci Med Sport 2011;14:233–7. 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Freedson PS, Melanson E, Sirard J. Calibration of the Computer Science and Applications, Inc. accelerometer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1998;30:777–81. 10.1097/00005768-199805000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lynch BM, Boyle T, Winkler E, et al. . Patterns and correlates of accelerometer-assessed physical activity and sedentary time among colon cancer survivors. Cancer Causes Control 2016;27:59–68. 10.1007/s10552-015-0683-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, Bergman B, et al. . The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. J Natl Cancer Inst 1993;85:365–76. 10.1093/jnci/85.5.365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Guzelant A, Goksel T, Ozkok S, et al. . The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: an examination into the cultural validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the EORTC QLQ-C30. Eur J Cancer Care 2004;13:135–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2003.00435.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ozturk A, Sarihan S, Ercan I, et al. . Evaluating quality of life and pulmonary function of long-term survivors of non-small cell lung cancer treated with radical or postoperative radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 2009;32:65–72. 10.1097/COC.0b013e31817e6ec2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Parschau L, Barz M, Richert J, et al. . Physical activity among adults with obesity: testing the Health Action Process Approach. Rehabil Psychol 2014;59:42–9. 10.1037/a0035290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Bennett JA, Lyons KS, Winters-Stone K, et al. . Motivational interviewing to increase physical activity in long-term cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Nurs Res 2007;56:18–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Short CE, James EL, Girgis A, et al. . Move more for life: the protocol for a randomised efficacy trial of a tailored-print physical activity intervention for post-treatment breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer 2012;12:172–81. 10.1186/1471-2407-12-172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Plotnikoff RC, Blanchard CM, Hotz SB, et al. . Validation of the decisional balance scales in the exercise domain from the transtheoretical model: A longitudinal test. Meas Phys Educ Exerc Sci 2001;5:191–206. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Rogers LQ, Shah P, Dunnington G, et al. . Social cognitive theory and physical activity during breast cancer treatment. Oncol Nurs Forum 2005;32:807–15. 10.1188/05.ONF.807-815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Rhodes RE, Blanchard CM, Matheson DH, et al. . Disentangling motivation, intention, and planning in the physical activity domain. Psychol Sport Exerc 2006;7:15–27. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ajzen I, Brown TC, Carvajal F. Explaining the discrepancy between intentions and actions: the case of hypothetical bias in contingent valuation. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2004;30:1108–21. 10.1177/0146167204264079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, et al. . The Self-Administered Comorbidity Questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:156–63. 10.1002/art.10993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Maxwell-Smith C, Cohen PA, Platell C, et al. . Wearable Activity Technology And Action-Planning (WATAAP) to promote physical activity in cancer survivors: Randomised controlled trial protocol. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2018;18:124–32. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hamer J. & Warner E. Lifestyle modifications for patients with breast cancer to improve prognosis and optimize overall health. Can Med Assoc J 2017;189:E268–E274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-028369supp001.pdf (177.4KB, pdf)