Abstract

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric disorder that is characterised by major problems in emotion regulation. Affected persons frequently engage in non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) to regulate emotions. NSSI is associated with high emotionality in patients with BPD and it can be expected that stimuli depicting scenes of NSSI elicit an emotional response indicative of BPD. The present study protocol describes the development and validation of an emotional picture set of self-injury (EPSI) to advance future research on emotion regulation in BPD.

Methods and analysis

The present validation study aims to develop and validate an emotional picture set relevant for BPD. Emotional responses to EPSI as well as to a neutral picture set will be investigated in a sample of 30 patients with BPD compared with 30 matched, healthy controls and to 30 matched depressive controls. Emotional responses will be assessed by heart rate variability, facial expression and Self-Assessment Manikin.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval was obtained by the medical ethics committee of the Carl-von-Ossietzky University of Oldenburg, Germany (registration: 2017–044). The results of the trial will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Trial registration number

NCT03149926; Pre-results.

Keywords: borderline, emotion regulation, emotional stimuli, NSSI

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Controlled study design to develop emotional stimuli relevant for borderline personality disorder (BPD).

Emotional reaction is assessed by subjective as well as objective measurements.

Emotion evocation is limited to non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) however other emotional triggers (eg, social interaction) are not investigated.

Limited to patients with BPD who actually engage in NSSI.

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a severe psychiatric disorder that is characterised by impairments in interpersonal, cognitive and emotional functioning.1 2 Pervasive problems of affect regulation have been identified as the central dysfunction in BPD and it has been conceptualised as a disorder of the emotion regulation system.3 Emotion dysregulation comprises high emotional vulnerability in conjunction with an inability to regulate emotions. Emotional vulnerability in individuals with BPD is characterised by high sensitivity to emotional stimuli, unusual emotional intensity and a slow return to emotional baseline (emotions are long-lasting). In addition, the identification, expression and inhibition of emotions are impaired.3–5

Not surprisingly, emotionally evocative material is commonly used to investigate BPD pathology. Previous studies have employed various emotional stimuli such as emotional facial expression,6 7 pleasant or unpleasant pictures,8 9 pictures and video clips depicting social interactions10 11 or script-driven imagery of a self-injurious act.12 However, extant research utilising such emotionally evocative materials are inconsistent in their ability to provoke emotional responses in patients with BPD.13 14 Although some studies did not find evidence for abnormal emotional responsiveness in BPD9 15 16 others did.12 17 18 One possible explanation for these contradictory results might be that the stimulus material was not specific enough to elicit an emotional response in participants with BPD. For example, a recent study investigated differences in emotional response and specificity of the presented stimuli, as well as baseline emotional intensity and emotional reactivity in patients with BPD, compared with healthy controls (HC). Emotional response to six discrete emotion-eliciting film clips was evaluated by measuring physiological and subjective reactions. Furthermore, the two groups were compared regarding their emotional reaction to films with BPD-specific content (eg, sexual abuse, emotional dependence and abandonment/separation). Compared with HC, participants with BPD showed a significantly stronger emotional response to ‘BPD-specific content’ films18 compared with films with non-BPD-specific emotional content. These findings suggest that measuring emotional responses characteristic of BPD only make sense in contexts that are psychologically challenging.9 13 The actual emergence and intensity of emotions depend on an array of psychological characteristics such as personality, learning experiences and cognition and the situational context, but also on the type and intensity of the perceived stimulus.19 Emotional stimuli that activate specific, self-relevant information seem to arouse a more intense emotional reaction than more general emotional stimuli.5 20 Therefore, to elicit a distinctive and BPD-specific emotional response, the stimulus material needs to have high relevance for persons with BPD and needs to trigger sensitivities that relate to BPD.5 9 Such a BPD-specific event could include the presentation of material used for non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI).

NSSI is associated with clinical and functional impairments and occurs in a variety of psychiatric disorders.21 There is an ongoing scientific debate regarding the conceptualisation and diagnostic organisation of NSSI. The fifth version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders presents Non-Suicidal Self-Injury Disorder (NSSID) as a separate nosological entity, but only as a condition that still requires further investigation.21 22 Thus, NSSI is not unique to BPD. Nevertheless, there is a general consensus that NSSI is related to BPD and is considered to be a core symptom of the disorder.1 21 NSSI is defined as a deliberate, although non-suicidal destruction of healthy body tissue, in which approximately 90% of patients with BPD partake.23 NSSI typically includes repeated behaviours, such as skin cutting, banging or hitting, burning, scratching and interfering with wound healing.24 Further, emotion dysregulation is closely related to NSSI in persons with BPD. According to the experiential avoidance model, NSSI is applied to reduce or remove aversive emotional experiences and might be maintained by negative reinforcement.25–27

Empirical evidence suggests that NSSI is commonly performed as an emotion regulation strategy. Self-injurers use NSSI to reduce unpleasant feelings, overcome dissociation, for self-punishment or for the reduction of aversive inner tension.28 29 Typically, NSSI is preceded by high arousal of negative emotions. NSSI behaviour is then initiated to decrease these emotions.29 30 For example, a decrease in negative affect and arousal was observed in self-injurers who were asked to visualise cutting or to engage in another painful behaviour, whereas the performance of a non-NSSI-related task did not lead to a decrease.29 In addition, seeing blood during NSSI seems to be an important aspect for many self-injurers. Glenn and Klonsky31 investigated the role of seeing blood during NSSI in persons with a history of NSSI. Most participants (51.6%) reported that seeing blood during NSSI was important. Furthermore, participants reported that seeing blood fulfilled multiple functions such as to relieve tension (84.8%), to calm down (72.7%), to feel real (51.5%), to show the realness of NSSI (42.4%), to help focus (33.3%) and to show that NSSI has been performed correctly/deep enough (15.2%). A pilot study by Naoum et al 32 compared 20 female patients with BPD and 20 HC to investigate the effect of seeing blood during NSSI following stress and pain induction. The patients with BPD demonstrated a significantly stronger decrease in arousal compared with the HC group however, with no significant differences between blood and non-blood conditions. In addition, the urge for NSSI was associated with a significantly greater decrease in arousal in the blood condition in patients with BPD. Yet, seeing blood did not result in greater relief of tension.

Despite the connection between emotion regulation deficits and NSSI in BPD, there are currently no studies utilising stimuli depicting the varying stages of NSSI. Doing so would help investigate whether emotional reactions in patients with BPD gradually depends on the stage of NSSI presented by the stimuli. Thus, a specified stimuli database, validated in a BPD population for evoking emotional responses in BPD, is lacking.

This study

Although emotion dysregulation is recognised as a core symptom of BPD, current evidence is inconsistent and contradictory. This could be explained, at least partially, by the use of unsuitable and unspecific emotional stimuli that do not tap into BPD-relevant themes. However, to improve and extend research on emotion regulation in BPD, the availability of validated emotional stimuli, that reliably elicit emotional reactions specifically for BPD, is a necessary prerequisite.

This study aims to develop and validate an emotional picture set, emotional picture set with scenes of self-injury (EPSI), relevant for BPD. In a second step, emotional reactions will be assessed by means of a self-report measurement, as well as by a psychophysiological assessment of emotional reactions in participants with BPD who engage in NSSI, in a depressive control group and in a sample of matched HC. Furthermore, participants are asked to indicate how strong the pictures relate to their person or biography. EPSI depicts objects frequently used for NSSI and shows the application of these objects at different stages of NSSI (objects only, pre-NSSI and during-NSSI). As NSSI can be associated with different emotional reactions depending on the stage of NSSI, differences in the emotional reactions are expected for participants with BPD and their respective NSSI stage. In the pre-NSSI stage (preparing for NSSI), negative affect, arousal and tension are expected to be strongest. As NSSI behaviour begins, negative affect, arousal and tension might start to decrease. In the during-NSSI stage (successfully performed NSSI, ie, seeing blood), an even stronger decrease of emotions and a sense of relief and relaxation is expected. We predict that the control groups will show emotional reactions opposite that of BPD, that is, the control groups are expected to show low emotional responses when seeing pictures of NSSI objects and pictures of the pre-NSSI stage; they will show strong responses when watching pictures of the during-NSSI stage. Lastly, BPD participants are expected to report higher self-referencing in response to the pictures when compared with controls.

To investigate whether our database is BPD relevant, evaluations of the NSSI images will be compared with neutral images and with two separate control groups. In this way, the present study will investigate to what extent EPSI can elicit an emotional response specifically for persons with BPD and if the emotional response differs with regard to the stage of NSSI.

Objectives

The primary outcome variables include self-rated emotional reactions, as measured by the Self-Assessment-Manikin (SAM)33; psychophysiological parameters of emotional reactions will be assessed using heart rate variability (HRV), as an indicator of autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity. Finally, facial expressions will be analysed and measured with the Noldus FaceReader software (Noldus Information Technology, www.noldus.com). As a secondary outcome variable, self-reference of EPSI will be measured on a 5-point Likert-scale, using the item ‘How much do you see a relation to your own person/to your biography?’ from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much).18

Primary objectives

An NSSI image database will be created (EPSI) to develop a BPD-relevant stimulus set.

A within-groups comparison of emotional reactions to EPSI and neutral stimuli will be conducted to validate EPSI. Moreover, the emotional reactions to EPSI will be compared among patients with BPD, depressed patients and HC.

Secondary objectives

To assess how emotional reactions in participants with BPD, who engage in NSSI, gradually depend on seeing NSSI objects, pre-NSSI pictures and during NSSI pictures.

To investigate if participants with BPD who engage in NSSI rate EPSI as more self-referential than matched HC and depressive controls.

To determine if self-referential measurement correlates positively with the actual emotional response.

To assess if BPD symptomatology correlates positively with emotional responses.

To investigate if self-rated emotional responses correlate with psychophysiological measurements of emotional responses within and between groups.

Methods and analysis

Participants

In total, 90 participants (30 patients with BPD, 30 depressed patients with depression and 30 HC subjects) of 18–60 years of age will be recruited. To control for altered autonomic responses, all participants must be free of severe and persistent neurological disorders (in particular, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, stroke or neurodegenerative diseases). Participants are not allowed to be currently medicated with antihistamines, neuroleptic medication, tranquillisers or beta blockers. Further, the patients with BPD must have a lifetime history of self-injury. Exclusion criteria for the patients with BPD include psychotic disorders, current major depressive episode and acute suicidal crisis. Patients in the depressed control group need to have a current major depressive episode (depressive symptoms for at least 2 weeks). Patients with depression who also meet diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder will be excluded. The HCl group must not exhibit a current psychiatric disorder or a history of self-injury. Additional exclusion criteria for both control groups include attempted suicide or current suicidal ideation. Control groups will be matched to the BPD group on age and sex.

Patient and public involvement

Patients were not involved in the development of the research question, outcome measures or study design.

Diagnostic procedure

Assessments of DSM-IV Personality Disorders34 35 and the Borderline Symptom Checklist36 will be used to verify the diagnosis of BPD and to assess BPD symptoms. The structured clinical interview (SCID I,II) will be performed to assess psychiatric disorders.37 Further, a demographic questionnaire, as well as the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory,38 will be applied.

To record the history and methods of self-injury, the Inventory of Statements about Self-Injury (ISAS) and the Self-Harm Behavior Questionnaire (SHQ) will be applied.39 40 Any outcome above zero (meaning that NSSI has been performed) on the ISAS or SHQ will be an exclusion criterion. General psychopathology will be recorded with the symptom checklist-90.41 Depressive symptoms will be self-rated with the Beck Depression Inventory .42 As the study will assess the emotional processing of images, the current mood and stress of the participants could have an influence. Therefore, they will be asked how emotionally strained and charged they are at the moment before and during testing, using a Likert-scale ranging from 0 to 10. A short break is planned in the middle of the experiment to check on the patients’ psychological distress. Acute somatic and psychological dissociation will be assessed via the short version of the Dissociative State Scale.43

Stimuli

A professional photographer will photograph and process three NSSI-related object and scene categories. These will include objects that are frequently used for NSSI by patients with BPD (self-injury objects (SIOs)), scenic presentation of SIO use shortly before the injury (SIObi) and scenic presentation during SIO use (SIOdur). SIOs will be selected based on use frequency, psychiatrists’ expertise and the existing literature.4 29 44 Actors will be instructed by experimenters to mimic SIO use; only their arms will be visible. Each image involving body parts will be portrayed by a man and woman, to prevent gender-biased judgement (see figure 1 for examples from EPSI for the three categories of objects and scenes).

Figure 1.

Examples from EPSI for the three categories of objects and scenes for NSSI. From first in a row: objects that are frequently used for NSSI by patients with BPD (SIO), scenic presentation of usage shortly before the injury and scenic presentation during the usage of SIO. BPD, Borderline personality disorder; EPSI, emotional picture set of self-injury; NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; SIO, self-injury objects.

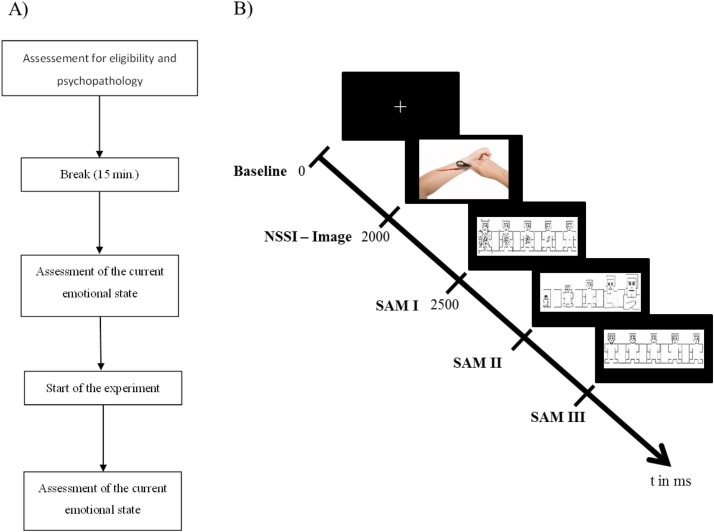

Experimental design

Participants will be asked to watch the images and to rate their current emotion on scales of arousal, dominance and valence, for which the SAM will be used.33 In addition, neutral objects will be displayed to provide control images (eg, towels and books; see figure 2 for examples of neutral images), which will be taken from an existing and validated database.45 A break will be included halfway through the stimulus presentation to assess participants’ emotional status and to prevent dissociations.46 Image presentation and SAM rating screens will be pseudorandomised across all categories. Medical professionals will be monitoring the participants to prevent overstraining and to intervene if necessary. In total, 90 images will be shown (45 EPSI/45 neutral), each for 500 ms, followed by the SAM evaluation (see figure 3 for the study design). At the end of the experiment, participants will perform a self-reference rating on all EPSI picture, using a 5-point scale with anchors: 1=‘not at all related to me’ and 5=‘definitely related to me’. See table 1 for the study timeline flow.

Figure 2.

Examples of neutral pictures from food-pics: an image database for experimental research on eating and appetite.

Figure 3.

(A) Study design. (B) Experimental paradigm; NSSI; SAM I/II/III (dominance, arousal and valence) presented pseudorandomised. NSSI, non-suicidal self-injury; SAM, Self-Assessment Manikin.

Table 1.

Study timeline flow

| Months | 1st year | 2nd year | 3rd year | |||||||||

| 1 | 4 | 7 | 10 | 13 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 31 | 34 | |

| Study preparation | X | X | ||||||||||

| Recruitment | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Clinical conduct | X | X | X | |||||||||

| Database clearing | X | X | ||||||||||

| Data analysis, publication | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

Physiological measurement

Autonomic nervous system

HRV is a valid and reliable indicator of ANS activity and is a transdiagnostic marker of psychopathology.47 48 Heart rate will be recorded continuously with an EC-12R PC-based resting ECG system (Labtech, Debrecen, Hungary). Three electrodes will be attached according to Einthoven’s triangle and ground at the right lower limb.49 To derive HRV, a frequency domain analysis will be conducted by taking a Fourier transformed time-domain representation of the interbeat interval (IBI).50 As we plan to record task concurrent HR, the low (LF: 0.04–0.15 Hz) and high (HF: 0.15–0.4 Hz) frequency bands will be of particular interest.51 The HRV data will be processed with the Kubios HRV software (www.kubios.com).52 A threshold-based artefact correction algorithm, as it is implemented in the Kubios software, will be performed. To separate ectopic and misplaced beats from the normal sinus rhythm, the automatic artefact correction algorithm will be used.52 Further, heart rate reactivity will be calculated.

Emotional face activation

The universal emotions of happy, sad, angry, surprised, scared, disgusted and neutral, as proposed by Ekman and Keltner,53 will be measured with Noldus FaceReader software (Noldus Information Technology, www.noldus.com). The programme reliably detects facial expressions and was successfully applied in numerous studies.54 55 Participants will be videotaped with a webcam throughout the session, using a frame-by-frame analysis during which 500+key points of the participant’s face will be localised and compared with a database of annotated images. The intensity of the universal emotions is then decoded on a scale from 0 to 1, where 0 indicates an absent emotion and 1 an intense emotional reaction. In addition to universal emotions, the software also captures valence and arousal. Valence is calculated by subtracting the intensity of negative expressions (angry, scared and disgusted) from the intensity of ‘happy’ expressions. Arousal is calculated by subtracting the mean activation of specific facial muscle groups, occurring over the last 60 s, from current muscle activation. The mean of the five highest values then yields the value of arousal.

To prevent biased responses, each session will be calibrated with a neutral stimulus per participant.

Statistical analysis

Stimulus validation

Interrater reliability will be assessed with Krippendorff’s alpha. The advantage of this method over competing methods is that Krippendorff’s alpha allows for more than two raters (unlike Cohen’s Kappa) and can handle missing data points (unlike Fleiss Kappa).56 The assumption of Krippendorff’s alpha is based on the observed disagreement corrected for disagreement by chance, which is calculable within a range of −1 to 1, where 1 illustrates perfect agreement, 0 no agreement beyond chance and negative values indicate inverse agreement.56 57 Bootstrapped confidence intervals will be used since the distribution is not known, the derivation of the correct SE is not straightforward and the type 1 error level is acceptable.56 58 59 Krippendorff’s alpha will be computed for each SAM dimension, for each stimuli category.

Behavioural data

If the data show a normal distribution, a 2×3×4 between-subjects analysis of variance (ANOVA) will be computed with the factors group, SAM evaluation and stimulus category. Further, the questionnaire scores will be correlated with the SAM evaluations for each stimulus category. To assess gender bias, linear regression will be performed to rule out possible performance differences.

Physiological data

HRV

Group-wise comparisons of HRV will be computed with a 2×2×4 ANOVA with the factors group, frequencies and stimulus category.

Emotional face activation

Facial expressions will be evaluated group-wise for each of the six universal emotions and stimulus categories, which results in a 2×4×6 ANOVA under the assumption of normally distributed data. Besides t-testing the group difference in valence and arousal, a correlation will be calculated with the SAM dimensions of valence and arousal. This serves as a further measure of the reliability of the participants’ behavioural response with their physiological reaction to the stimuli.

Sample size justification

Based on calculations with G*Power, a fixed effects ANOVA with 30 participants per group will yield a large effect size (0.62) with a power of 0.66.60 The size of the groups was derived from earlier studies comparing the affective reaction of patients with BPD with HC while watching images.18 61

Ethics and dissemination

The study will be conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki in order to ensure the well-being and rights of the participants. The project has received ethical approval by the local medical ethics committee of the Carl-von-Ossietzky University of Oldenburg (registration: 2017-044). Written informed consent will be obtained from all participants. Participants will be able to withdraw from the study at any time without giving any reasons. Medical professionals will be present at all times during the experiment. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials (URL), with the trial registration number: NCT03149926. Results of the main trial and each of the secondary endpoints will be submitted for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

KB and MS contributed equally.

Contributors: KB and MS: study design, literature search, figures and writing. PS and AP: study design, literature search, writing and supervision. CS: study design and supervision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: KB, MS, PS and CS declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. AP declares that she served on advisory boards, gave lectures, performed phase 3 studies or received travel grants within the last 3 years from Eli Lilly and Co, Lundbeck, MEDICE Arzneimittel, Pütter GmbH and Co KG, Novartis, Servier and Shire; and has authored books and articles on ADHD published by Elsevier, Hogrefe, Schattauer, Kohlhammer, Karger and Springer.

Ethics approval: The project has received ethical approval by the local medical ethics committee of the Carl-von-Ossietzky University of Oldenburg (registration: 2017-044).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edn Washington DC: Amer Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, et al. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004;364:453–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder: Guilford Publications, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Svaldi J, Dorn C, Matthies S, et al. Effects of suppression and acceptance of sadness on the urge for non-suicidal self-injury and self-punishment. Psychiatry Res 2012;200:404–16. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eddie D, Bates ME, Vaschillo EG, et al. Rest, reactivity, and recovery: a psychophysiological assessment of borderline personality disorder. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:505 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Baskin-Sommers AR, Hooley JM, Dahlgren MK, et al. Elevated preattentive affective processing in individuals with borderline personality disorder: a preliminary fMRI study. Front Psychol 2015;6:6 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cullen KR, LaRiviere LL, Vizueta N, et al. Brain activation in response to overt and covert fear and happy faces in women with borderline personality disorder. Brain Imaging Behav 2016;10:319–31. 10.1007/s11682-015-9406-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hazlett EA, Zhang J, New AS, et al. Potentiated amygdala response to repeated emotional pictures in borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2012;72:448–56. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suvak MK, Sege CT, Sloan DM, et al. Emotional processing in borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord 2012;3:273–82. 10.1037/a0027331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lobbestael J, Arntz A. Emotional hyperreactivity in response to childhood abuse by primary caregivers in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 2015;48:125–32. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2015.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koenigsberg HW, Fan J, Ochsner KN, et al. Neural correlates of the use of psychological distancing to regulate responses to negative social cues: a study of patients with borderline personality disorder. Biol Psychiatry 2009;66:854–63. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kraus A, Valerius G, Seifritz E, et al. Script-driven imagery of self-injurious behavior in patients with borderline personality disorder: a pilot FMRI study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;121:41–51. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01417.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sloan DM, Sege CT, McSweeney LB, et al. Development of a borderline personality disorder-relevant picture stimulus set. J Pers Disord 2010;24:664–75. 10.1521/pedi.2010.24.5.664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. van Zutphen L, Siep N, Jacob GA, et al. Emotional sensitivity, emotion regulation and impulsivity in borderline personality disorder: a critical review of fMRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2015;51:64–76. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feliu-Soler A, Pascual JC, Soler J, et al. Emotional responses to a negative emotion induction procedure in Borderline Personality Disorder. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology 2013;13:9–17. 10.1016/S1697-2600(13)70002-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kuo JR, Linehan MM. Disentangling emotion processes in borderline personality disorder: physiological and self-reported assessment of biological vulnerability, baseline intensity, and reactivity to emotionally evocative stimuli. J Abnorm Psychol 2009;118:531–44. 10.1037/a0016392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eddie D, Bates ME. Toward validation of a borderline personality disorder-relevant picture set. Personal Disord 2017;8:255–60. 10.1037/per0000173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sauer C, Arens EA, Stopsack M, et al. Emotional hyper-reactivity in borderline personality disorder is related to trauma and interpersonal themes. Psychiatry Res 2014;220:468–76. 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.06.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kučera D, Haviger J. Using Mood Induction Procedures in Psychological Research. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2012;69(Supplement C):31–40. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.11.380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Philippot P, Schaefer A, Herbette G. Consequences of specific processing of emotional information: Impact of general versus specific autobiographical memory priming on emotion elicitation. Emotion 2003;3:270–83. 10.1037/1528-3542.3.3.270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zetterqvist M. The DSM-5 diagnosis of nonsuicidal self-injury disorder: a review of the empirical literature. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health 2015;9:31 10.1186/s13034-015-0062-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Association AP. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Dsm-5: Amer Psychiatric Pub Incorporated, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. The 10-year course of physically self-destructive acts reported by borderline patients and axis II comparison subjects. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2008;117:177–84. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2008.01155.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Favazza AR. The coming of age of self-mutilation. J Nerv Ment Dis 1998;186:259–68. 10.1097/00005053-199805000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reitz S, Kluetsch R, Niedtfeld I, et al. Incision and stress regulation in borderline personality disorder: neurobiological mechanisms of self-injurious behaviour. Br J Psychiatry 2015;207:165–72. 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.153379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chapman AL, Gratz KL, Brown MZ. Solving the puzzle of deliberate self-harm: the experiential avoidance model. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:371–94. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nock MK, Prinstein MJ. A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol 2004;72:885–90. 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andover MS, Morris BW. Expanding and clarifying the role of emotion regulation in nonsuicidal self-injury. Can J Psychiatry 2014;59:569–75. 10.1177/070674371405901102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Klonsky ED. The functions of deliberate self-injury: a review of the evidence. Clin Psychol Rev 2007;27:226–39. 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Victor SE, Klonsky ED. Daily emotion in non-suicidal self-injury. J Clin Psychol 2014;70:364–75. 10.1002/jclp.22037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Glenn CR, Klonsky ED. The role of seeing blood in non-suicidal self-injury. J Clin Psychol 2010;66:466–73. 10.1002/jclp.20661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Naoum J, Reitz S, Krause-Utz A, et al. The role of seeing blood in non-suicidal self-injury in female patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2016;246:676–82. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.10.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bradley MM, Lang PJ. Measuring emotion: the Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 1994;25:49–59. 10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schotte C, De Doncker D. ADP-IV Questionnaire. Antwerp: University Hospital Antwerp, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Doering S, Renn D, Höfer S, et al. Validierung der deutschen Version des Fragebogens zur Erfassung von DSM-IV Persönlichkeitsstörungen (ADP-IV). Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie 2007;53:111–28. 10.13109/zptm.2007.53.2.111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wolf M, Limberger M, Kleindienst N, et al. Kurzversion der Borderline-Symptom-Liste (BSL-23): Entwicklung und Überprüfung der psychometrischen Eigenschaften. Psychiatrie, Psychosomatik und Medizinische Psychologie. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2009;59:321–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wittchen H-U, Wunderlich U, Gruschwitz S, et al. SKID I. Strukturiertes Klinisches Interview für DSM-IV. Achse I: Psychische Störungen. Interviewheft und Beurteilungsheft. Eine deutschsprachige, erweiterte Bearb. d. amerikanischen Originalversion des SKID I, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oldfield RC. The assessment and analysis of handedness: the Edinburgh inventory. Neuropsychologia 1971;9:97–113. 10.1016/0028-3932(71)90067-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Klonsky ED, Glenn CR. Assessing the functions of non-suicidal self-injury: Psychometric properties of the Inventory of Statements About Self-injury (ISAS). J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2009;31:215–9. 10.1007/s10862-008-9107-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gutierrez PM, Osman A, Barrios FX, et al. Development and initial validation of the Self-harm Behavior Questionnaire. J Pers Assess 2001;77:475–90. 10.1207/S15327752JPA7703_08 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Franke GH. Symptom-Checkliste von Derogatis (SCL-90-R): Beltz Test, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. BDI-II Beck Depression Inventory: Manual: Psychological Corporation, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Stiglmayr CE, Braakmann D, Haaf B, et al. Entwicklung und psychometrische Charakteristika der Dissoziations-Spannungs-Skala akut (DSS-akut). PPmP-Psychotherapie· Psychosomatik· Medizinische Psychologie 2003;53:287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Brown RC, Fischer T, Goldwich AD, et al. #cutting: Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) on Instagram. Psychol Med 2018;48:337–46. 10.1017/S0033291717001751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Blechert J, Meule A, Busch NA, et al. Food-pics: an image database for experimental research on eating and appetite. Front Psychol 2014;5:617 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jaeger S, Steinert T, Uhlmann C, et al. Dissociation in patients with borderline personality disorder in acute inpatient care - A latent profile analysis. Compr Psychiatry 2017;78:67–75. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2017.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Koenig J, Rinnewitz L, Parzer P, et al. Resting cardiac function in adolescent non-suicidal self-injury: The impact of borderline personality disorder symptoms and psychosocial functioning. Psychiatry Res 2017;248:117–20. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.12.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wilson ST, Chesin M, Fertuck E, et al. Heart rate variability and suicidal behavior. Psychiatry Res 2016;240:241–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Einthoven W, Fahr G, de Waart A. Über die Richtung und die manifeste Grösse der Potentialschwankungen im menschlichen Herzen und über den Einfluss der Herzlage auf die Form des Elektrokardiogramms. Pflüger’s Archiv für die gesamte Physiologie des Menschen und der Tiere 1913;150:275–315. 10.1007/BF01697566 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Allen JJ, Chambers AS, Towers DN. The many metrics of cardiac chronotropy: a pragmatic primer and a brief comparison of metrics. Biol Psychol 2007;74:243–62. 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Thayer JF, Hansen AL, Johnsen BH. The non-invasive assessment of autonomic influences on the heart using impedance cardiography and heart rate variability Handbook of behavioral medicine: Springer, 2010:723–40. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tarvainen MP, Niskanen JP, Lipponen JA, et al. Kubios HRV--heart rate variability analysis software. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2014;113:210–20. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ekman P, Keltner D. Universal facial expressions of emotion. California mental health research digest 1970;8:151–8. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boerner KE, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, et al. The Effect of Parental Modeling on Child Pain Responses: The Role of Parent and Child Sex. J Pain 2017;18:702–15. 10.1016/j.jpain.2017.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dalton PS, Gonzalez Jimenez VH, Noussair CN. Exposure to Poverty and Productivity. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170231 10.1371/journal.pone.0170231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zapf A, Castell S, Morawietz L, et al. Measuring inter-rater reliability for nominal data - which coefficients and confidence intervals are appropriate? BMC Med Res Methodol 2016;16:93 10.1186/s12874-016-0200-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krippendorff K. Estimating the reliability, systematic error and random error of interval data. Educ Psychol Meas 1970;30:61–70. 10.1177/001316447003000105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vanbelle S, Albert A. A bootstrap method for comparing correlated kappa coefficients. J Stat Comput Simul 2008;78:1009–15. 10.1080/00949650701410249 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. McKenzie DP, Mackinnon AJ, Péladeau N, et al. Comparing correlated kappas by resampling: is one level of agreement significantly different from another? J Psychiatr Res 1996;30:483–92. 10.1016/S0022-3956(96)00033-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Eddie D, Bates ME. Toward validation of a borderline personality disorder–relevant picture set. Personal Disord 2017;8:255–60. 10.1037/per0000173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.