Abstract

Objectives

Central America is a region with an elevated burden of chronic kidney disease (CKD); however, the cost of treatment for end-stage renal disease (ESRD) remains an understudied area. This study aimed to investigate the direct costs associated with haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) in public and private institutions in Panama in 2015, to perform a 5-year budget impact analysis and to calculate the years of life lost (YLL) due to CKD.

Design

A retrospective cost-analysis study using hospital costs and registry-based data.

Setting

Data on direct costs were derived from the public and private sectors from two institutions from Panama. Data on CKD-related mortality were obtained from the National Mortality Registry.

Methods

A budget impact analysis was performed from the payer perspective, and five scenarios were estimated, with the assumption that the mix of dialysis modality use shifts towards a greater use of PD over time. The YLL due to CKD was calculated using data recorded between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2015. The linear method was utilised for the analyses with the population aged 20–77 years old.

Results

In 2015, the total costs for dialysis in the public sector ranged from ~US$7.9 million (PD) to US$62 million (HD). The estimated costs were higher in the scenario in which a decrease in PD was assumed. The average annual loss due to CKD was 25 501 808.40 US$-YLL.

Conclusion

ESRD represents a major challenge for Panama. Our results suggest that an increased use of PD might provide an opportunity to substantially lower overall ESRD treatment costs.

Keywords: chronic renal failure, dialysis, costs, years of life lost, panama

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study on the economic costs of haemodialysis (HD) and peritoneal dialysis (PD) modalities performed in Panama.

Costs due to hospitalisation, complications and emergency medicines were not evaluated for HD. Therefore, any possible bias is likely to result in underestimation and not overestimation of the cost advantage of PD over HD.

Indirect costs were not assessed; however, the years of life lost, a contributor to indirect costs, were estimated using National Mortality Registry data.

Background

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive disease that imposes a substantial public health burden.1 Early detection can prevent or delay progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).2 The majority of individuals with CKD worldwide are living in low-income and middle-income countries,3 where there exists pressure on limited healthcare resources.4 In many countries, access to renal replacement therapy (RRT) has progressively increased, yet it remains largely unaffordable for most patients and imposes a major burden on health systems.5

The evaluation of the economic impact of CKD is important to provide information on which decisions regarding the allocation of healthcare resources can be based. However, estimating the costs associated with CKD is challenging given that underreporting is most common in the earliest stages of the disease, resulting in biased estimates.6 Dialysis remains the most commonly employed treatment option for patients with ESRD because not all patients are medically suitable for kidney transplantation, and the demand for kidneys far exceeds the supply.7 The total cost of dialysis is mostly composed of the costs of the treatment itself (including disposables, machines, accommodation, electricity, water and human resources) and the costs of medications, transportation, complications, additional hospital admissions and interventions.8

Central America is a region with an elevated burden of CKD9 10; however, very little is known regarding the costs associated with milder forms of CKD and ESRD. Panama is an upper-middle income country estimated to have a population of 4.1 million inhabitants as of 2018.11 The country is divided into 10 provinces and 5 ‘Comarcas,’ which are geographically defined areas populated by several indigenous American groups. Panama has a fragmented health system with public and private health coverage schemes that encompass three distinct entities.12 The Ministry of Health (MoH) and Social Security (Caja de Seguro Social; CSS), which belong to the public health system, operate independently from each other and cover ~30% and 70% of the population, respectively.13 The MoH provides health coverage to the unemployed population, whereas the CSS provides health coverage to formally employed persons. In addition, there are private insurers with which affiliation is voluntary.14 Therefore, the direct costs of medical care are at least partly covered by the CSS (the Panamanian public health insurance) or by the state.

Electronic health records are in the process of being implemented at public health facilities; consequently, there is currently no CKD national registry in Panama.12 Furthermore, national estimates of CKD derived from epidemiological studies are lacking. Recently, a cross-sectional study reported a CKD prevalence of 12.6% in the two provinces in which 60% of the population resides.15 Moreover, the study described geographical disparities in age-adjusted standardised mortality rates due to CKD.15 In 2001, the CSS calculated the annual costs of care for the peritoneal dialysis (PD) and haemodialysis (HD) programmes, resulting in average per patient costs of US$25 426.64 and US$18 857.21, respectively. However, neither the costs of RRT nor the years of life lost (YLL), which are useful measures to consider when prioritising public health interventions, has been recently evaluated.

The aim of this study was to (1) estimate the direct costs associated with ESRD treatment, whether HD or PD, in public and private Panamanian institutions in 2015, (2) to perform a 5-year budget impact analysis and (3) to calculate the YLL due to CKD in the country.

Materials and methods

Cost analysis–ESRD

The following three sectors were selected based on their dialysis coverage and formally invited to participate in the study via an institutional letter: CSS (comprising all HD and PD at the national level), Hospital Santo Tomás (MoH) and the major private HD outpatient clinic in the country Centro de Tratamiento de Enfermedades Renales, S.A. (CETRERSA).

Because the information was not homogenously systematised, data on costs were not available from the MoH. Therefore, in the present study, the data were derived from the public (CSS renal programme) and private (CETRERSA) sectors. Private data only included HD procedures, whereas CSS data included PD and HD. We used data collected from January 2015 to December 2015, and the results are presented in US$ and on a per-year basis.

The estimation of the costs of the CSS renal programme was based on data from the HD national coordinating office and included costs associated with administration, drugs and consumables and staff wages (online supplementary table 1). Data from CETRERSA were obtained from the administrative staff and included costs associated with administration, staff wages, cleaning services, drugs and consumables, electricity, capital expenses (ie, buildings, machines, instruments) and laundry and sterilisation (online supplementary table 2). Data were provided to researchers in different formats. For the private sector, data on HD costs were grouped according to categories using the format shown in online supplementary table 2. For the CSS, data on HD and PD costs were provided in several electronic PDF files, and costs were distributed according to the categories stipulated previously.

bmjopen-2018-027229supp001.pdf (291.4KB, pdf)

In the present study, PD includes both continuous ambulatory PD and automated PD. The prevalent HD/PD cost ratio was calculated for the public sector. The estimated annual increase in the rate of HD and PD utilisation was calculated according to the prevalence reported by the Latin America Dialysis and Transplant Registry in 201016 and the prevalence reported in 2015 by the CSS and CETRERSA. The calculated annual changes in rates from 2010 to 2015 were 10.65% and −4.23% for HD and PD, respectively, with a ratio of 2.5%. The cost analysis was performed using present values; therefore, no discounted rates were included.

We performed a 5-year time horizon budget impact analysis on the direct costs related to the renal programme in Panama, considering costs from both the CSS and the private sector. The budget impact analysis estimated how changes in the mix of dialysis modalities would impact the trajectory of the total spending for dialysis services (assuming that the mix of dialysis modalities used shifts towards a greater use of PD over time). The budget impact model was from the payer perspective and included the following five scenarios from 2015 until 2020: scenario 1 was a 2.5% yearly increase in the use of PD, scenario 2 was a 5% yearly increase in the use of PD, scenario 3 was a 7.5% yearly increase in the use of PD and scenario 4 was a 1% yearly decrease in the use of PD. Scenario 5 was the reference scenario. The scenarios were based on the ratio of sensibility (annual increase in the rate of HD utilisation/annual increase in the rate of PD utilisation)=2.5%. In addition, complementary analyses were performed with different arbitrary assumptions (10% annual increase in PD, 2.5% decrease in PD utilisation).

YLL due to premature CKD mortality

Data on CKD mortality for the year 2015 were retrieved from the National Mortality Registry at the Institute of Statistics and Census. Deaths recorded as N18 (CKD, n=221) and N19 (unspecified kidney failures, n=18) were included according to the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision codes. The linear method was utilised for the analyses in the population aged 20–77 years old.

The YLLs were calculated by subtracting the life expectancy from the age of death of each individual. We estimated the average life expectancy on the basis of the Institute of Statistics and Census life table (77.74 years) and the value of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) per capita in 2015. The YLLs for each individual were multiplied by the GDP per capita estimated for 2015, obtaining the YLLs in US$. We applied a 3% discounted present value at a social discount rate. The estimated total annual YLLs were reported stratified by sex and the following age categories: 20–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60 and 71–80 years. In addition, YLLs were stratified by province.

All analyses were performed in Excel and Stata V.14.

Ethical statement

Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the medical directors of the respective institutions. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics review Committee of the Gorgas Memorail Institute for Health Studies

Patient and public involvement

The study did not involve patients or the public in its planning or execution.

Results

Cost analysis

The mean direct expenditures for dialysis are summarised in table 1. As of 2015, 2075 persons were receiving RRT (PD or HD), and of those, 87% were receiving HD. The total costs for dialysis in the public sector ranged from ~US$7.9 million (PD) to US$62 million (HD). The total cost per year of the programmes in the public and private sectors combined was US$70.3 million. The HD/PD cost ratio in the public sector was 1.19.

Table 1.

Estimated costs of dialysis in the public and private sectors for the year 2015 in Panama

| Public (CSS) | Private | ||

| PD | HD | HD | |

| Number of patients (n) | 265 | 1746 | 64 |

| Total annual costs (US$) | 7 915 687.25 | 62 102 496.24 | 2 797 380.00 |

| Cost/patient/year (US$) | 29 870.52 | 35 568.44 | 43 447.96 |

| Public (CSS) | Public and Private | |

| PD + HD | PD + HD | |

| Number of patients (n) | 2011 | 2075 |

| Total cost of programmes (US$) | 67 553 921.23 | 70 351 301.23 |

CSS, Caja de Seguro Social; HD, haemodialysis; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

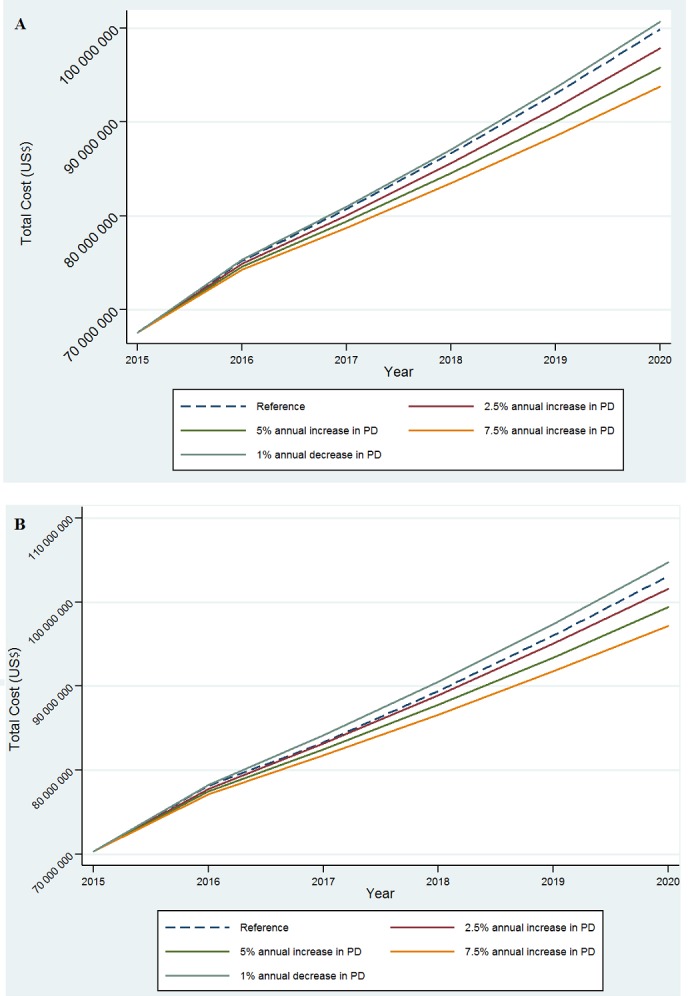

The total estimated costs (US$) during the 5 years for the reference scenarios were 503 million (CSS) and 520 million (combined sectors). Figure 1 shows the budget impact model according to the different scenarios for the public sector (CSS) (Figure 1A) and for the public and private sectors combined (Figure 1B). In the CSS, the estimated costs for the year 2020 ranged from US$93.8 million (assuming a 7.5% annual increase in the use of PD) to US$100.7 million (assuming a 1% decrease in the use of PD).

Figure 1.

Estimated cost (US$) of the dialysis program according to different scenarios (A) for the public sector (B) and for the public and private sectors combined. Estimations based on data from the public (CSS renal programme) and private (CETRERSA) sectors. CSS, Caja de Seguro Social; PD, peritoneal dialysis.

Likewise, in the public and private sectors, the estimated costs were higher in the scenario in which a 1% decrease in the use of PD was assumed (US$104.7 million) (Figure 1B). Sensitivity analyses were conducted to explore the model forecasts under varying assumptions. In general, the results of these analyses demonstrate that the savings will be greater if the shift towards greater PD use is accomplished sooner (a 10% annual increase in the use of PD in CSS resulted in reducing costs by US$4.5 million per year).

YLL-US$ due to premature CKD mortality

In 2015, CKD was the cause of 440 deaths in Panama, accounting for 2.4% of the total deaths registered. There were 279 male deaths (63.4%) and 161 female deaths (36.6%).

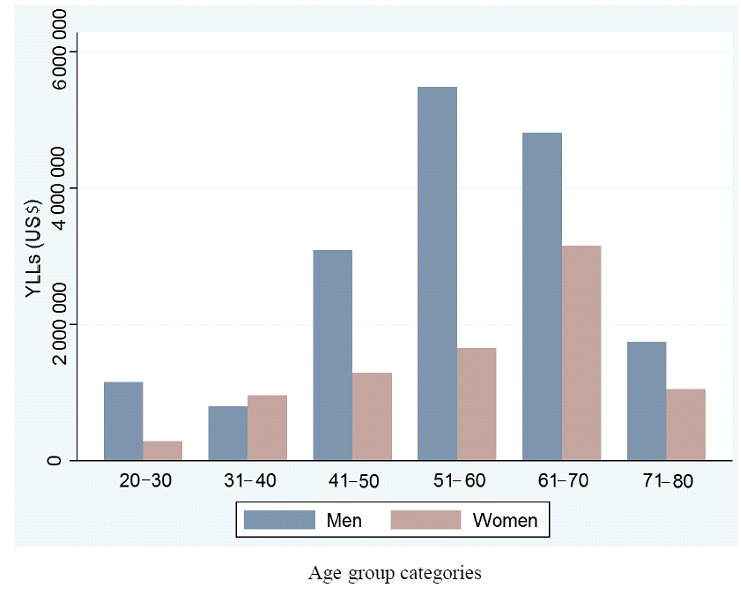

The average annual loss was 25 501 808.40 YLL-US$. In men, a higher YLL-US$ was observed in the 51–60 years age group than in the other age groups, whereas in women, a higher YLL-US$ was observed in the 61–70 years age group than in the other age groups, as shown in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Years of Life Lost-(US$) due to premature mortality, according to age group categories in Panama. Year 2015. Deaths recorded as N18 (chronic kidney disease, n=221) and N19 (unspecified kidney failures, n=18). YLLs, years of life lost.

The three provinces with the highest accumulated numbers of YLL-US$ due to CKD in the age group younger than 40 years were (1) the Province of Panama (1 548 252.11 YLLs), (2) the Province of Coclé (459 212.85 YLLs) and the Province of Colón (314 586.97 YLLs) (online supplementary table 3).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that treatment with dialysis imposes substantial burdens in terms of the provision of health services and YLLs.

In Panama, the total healthcare expenditure represented ~8% of the GDP in 2014. In the context of our findings, in 2015, ~1.6% of the healthcare budget was invested in dialysis, considering only the costs derived from the CSS. Notably, the costs associated with milder forms of CKD (early stages of the disease without RRT) were not evaluated, and it has been reported that the economic burden associated with milder forms of CKD is more than twice the total cost of ESRD.17 In addition, the average annual loss in terms of YLLs due to CKD represented 0.59% of the GDP allocated to health. Similar levels of expenditure have been reported in high-income countries.18 19

Assuming our reference scenario, it is estimated that the accumulated costs in 5 years will be ~US$505 million for the CSS and US$525 million for both the private and public sectors combined. Noteworthy, this estimate excludes the ongoing costs derived from the MoH, which also adds financial pressure to the health system. In this study, the cost of therapy per se and medicines were the major drivers of the total cost of HD for the CSS, whereas staff wages represented the highest cost in the private sector. Therefore, strategies aimed at reducing these costs would help reduce the annual cost in the short term.

All forms of dialysis that occur outside of the hospital setting are more cost effective than in-hospital-based dialysis forms.20 In fact, the number of patients treated with PD rose worldwide from 1997 to 2008, with a 2.5-fold increase in the prevalence of patients receiving PD in developing countries.21 In agreement with the results of previous studies, we observed a considerable cost savings related to the use of PD instead of HD.22 Our HD/PD cost ratio was lower than the one reported in Mexico but higher than those reported previously in other countries in the region.23 Despite several advantages, including the possibility of being offered in the remotest locations, our results indicate that PD is still an underused therapy in Panama; this contrasts with the results of reports from other countries, such as Mexico, El Salvador and Guatemala, where the PD utilisation rates are 66%, 76.5% and 56%, respectively.21 In this context, if the CSS increases the utilisation of PD by 7.5% per year, the proportion of dialysis accounted for by PD will reach 50% in 5 years. The reasons for the underutilisation of PD are presumably multifactorial and may partly be explained by the scarcity of trained nephrologists and nurses as well as the lack of relevant health policies.10 Currently, there are 32 nephrologists nationwide, which results in a relatively low number of nephrologists per million population.24 Furthermore, as opposed to other countries,22 Panama has a small market, lacks local manufacturing facilities for PD bags and largely depends on imported medicines/equipment. Notably, Colombia and Nicaragua have also reported a decrease in the use of PD and an expansion of the use of HD from 2000 to 2010.16

There is compelling evidence that kidney transplantations have led to substantial cost savings for healthcare systems in high-income countries.25 Kidney transplantations in Panama began in 1990, and the necessary human resources and infrastructure have been expanded. According to the Panamanian Transplant Organization (PTO), in 2015, there were 28 kidney transplantations performed in Panama, and the number of donors has increased over the years,26 although at a slow rate.

Taken together and considered from a macroeconomic standpoint, our results suggest that increasing PD utilisation might reduce the overall healthcare expenditure in Panama. Therefore, key strategies such as the implementation of policies and incentives favouring PD over HD should be advocated.27 A critical complementary approach is slowing the progression of CKD to ESRD. Likewise, enhancing kidney transplant programmes is strongly recommended

The burdens imposed by premature death and the loss of health due to CKD have been widely described. Between 1990 and 2013, the number of cases of CKD due to diabetes and other causes increased by >50% worldwide.28 In addition, the burden of CKD disproportionately impacts low-income and middle-income countries where the prevalences of diabetes, hypertension and obesity are growing the most.29 Moreover, poverty increases the risk of pathologies that predispose individuals to CKD and worsen outcomes in those who already have the disease.30 Previous studies have reported a relationship between progressive CKD and its impact on household income or poverty, including spending >10% of the household income on out of pocket payments.31 32

Remarkably, Latin America has the highest CKD-related death rate in the world,33 and diabetes mellitus, hypertension and, recently, CKD of unknown aetiology are contributors to CKD-related death in Central America.5 29 In Panama, the CKD-related mortality rate has been decreasing since 2006; however, geographical disparities exist.15 Interestingly, Coclé, a province with the highest age-adjusted mortality rate in the country,15 was found to have markedly elevated YLLs in the under 40 years age group. Taken together, the sum of the estimated YLLs and the costs of the dialysis is unsustainable for the health system, highlighting the importance of prevention. Recently, the legal framework for CKD registration in Panama started with a resolution signed by the MoH, establishing the notification of all stages of CKD as compulsory for private and public health institutions at a national level. In addition, the CKD guidelines are currently being revised. From a broader perspective, if the Sustainable Development Goal of poverty reduction is to be accomplished, it is essential that health systems protect individuals from the economic burdens imposed by CKD and other non-communicable diseases.34

This study has strengths and limitations. Costs due to hospitalisation, complications, emergency medicines and transportation were not included in the HD calculation; hence, any possible bias is likely to result in the underestimation and not the overestimation of the cost advantage of PD over HD. It is noteworthy that patients frequently have to travel long distances, often with their families, to receive specialised care, adding a dimension of social and economic consequences that was beyond the scope of this study. Although we excluded these costs, we estimated the YLLs, which is a measure of indirect costs. However, it is likely that the reliance on diagnostic code data alone to define CKD as a cause of death and the effects of underreporting resulted in the underestimation of people with early stages of CKD. Finally, because the public systems operate independently of each other and the information (health and costs) is not homogenously systematised, cost data could not be obtained from the MoH. Therefore, the total costs from the public sector were underestimated, and the estimated yearly increase in the rates of utilisation should be interpreted with caution. Likewise, we could not perform a cost-effectiveness analysis. Despite the lack of registries, the Panamanian Society of Nephrology and Hypertension and the PTO have been actively recording the number of cases undergoing RRT. Currently, there are three institutions in the MoH offering dialysis within the country. According to the PTO, in 2015, there were 26 and 204 patients receiving PD and HD treatment, respectively, in these institutions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, CKD represents a major challenge for Panama. Our results suggest that increasing the utilisation of PD will lower the overall ESRD treatment costs. In the long term, an important method of reducing the overall annual cost is to reduce the number of patients with ESRD. Consequently, patients with CKD in the early stages (who are more abundant and more frequent users of the health system) should not be ignored by policy makers. Altogether, the enormous cost associated with CKD provides a compelling economic incentive for improving the prevention, detection and management of CKD and the relevant health policies in Panama.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

IMV is supported by the Sistema Nacional de Investigación (SNI), Senacyt, Panama.

Footnotes

Contributors: IMV wrote the draft of the work. IMV, MTC and VH-B analysed the data. CC and RV provided the data. IMV, MTC, RV, BG, JM, CC and VH-B interpreted the data, critically revised the draft for important intellectual content and approved the final version. All the authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by an institutional research grant from Panama (Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas 9044.053).

Competing interests: IMV, RV, BG, JM, CC and VH-B declare no conflict of interest. MTC currently works at Sanofi Pasteur, nonetheless, her responsibilities do not relate with the submitted work.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Ethics Review Committee of the Gorgas Memorial Institute for Health Studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the authors on reasonable request via email.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Xie Y, Bowe B, Mokdad AH, et al. Analysis of the Global Burden of Disease study highlights the global, regional, and national trends of chronic kidney disease epidemiology from 1990 to 2016. Kidney Int 2018;94:567–81. 10.1016/j.kint.2018.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dienemann T, Fujii N, Orlandi P, et al. International Network of Chronic Kidney Disease cohort studies (iNET-CKD): a global network of chronic kidney disease cohorts. BMC Nephrol 2016;17:121 10.1186/s12882-016-0335-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mills KT, Xu Y, Zhang W, et al. A systematic analysis of worldwide population-based data on the global burden of chronic kidney disease in 2010. Kidney Int 2015;88:950–7. 10.1038/ki.2015.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet 2013;382:158–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Obrador GT, Rubilar X, Agazzi E, et al. The Challenge of Providing Renal Replacement Therapy in Developing Countries: The Latin American Perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 2016;67:499–506. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.08.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. System USRD. Medicare Expenditures for Persons with CKD. http://www.ajkd.org/article/S0272-6386(16)00099-8/pdf (Accessed April 2016).

- 7. Abecassis M, Bartlett ST, Collins AJ, et al. Kidney transplantation as primary therapy for end-stage renal disease: a National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQITM) conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2008;3:471–80. 10.2215/CJN.05021107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vanholder R, Van Biesen W, Lameire N. Renal replacement therapy: how can we contain the costs? Lancet 2014;383:1783–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60721-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Glassock RJ, Warnock DG, Delanaye P. The global burden of chronic kidney disease: estimates, variability and pitfalls. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:104–14. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosa-Diez G, Gonzalez-Bedat M, Pecoits-Filho R, et al. Renal replacement therapy in Latin American end-stage renal disease. Clin Kidney J 2014;7:431–6. 10.1093/ckj/sfu039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censo. Available at https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/Publicaciones/Publicaciones.aspx?ID_SUBCATEGORIA=10&ID_PUBLICACION=491&ID_IDIOMA=1&ID_CATEGORIA=3 (Accessed July 31, 2018).

- 12. Ministry of Health. Available at http://www.minsa.gob.pa/sites/default/files/publicaciones/asis_final_2018c.pdf (Accessed on December 2018).

- 13. Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Censo población asegurada. Available at https://www.contraloria.gob.pa/inec/archivos/P8401421-01.pdf (Accessed July 31, 2018).

- 14. Romero LI, Quental C. The Panamanian health research system: a baseline analysis for the construction of a new phase. Health Res Policy Syst 2013;11:33 10.1186/1478-4505-11-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moreno Velásquez I, Castro F, Gómez B, et al. Chronic Kidney Disease in Panama: Results From the PREFREC Study and National Mortality Trends. Kidney Int Rep 2017;2:1032–41. 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gonzalez-Bedat M, Rosa-Diez G, Pecoits-Filho R, et al. Burden of disease: prevalence and incidence of ESRD in Latin America. Clin Nephrol 2015;83(7 Suppl 1):3–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Couser WG, Remuzzi G, Mendis S, et al. The contribution of chronic kidney disease to the global burden of major noncommunicable diseases. Kidney Int 2011;80:1258–70. 10.1038/ki.2011.368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Essue BM, Wong G, Chapman J, et al. How are patients managing with the costs of care for chronic kidney disease in Australia? A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol 2013;14:5 10.1186/1471-2369-14-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zelmer JL. The economic burden of end-stage renal disease in Canada. Kidney Int 2007;72:1122–9. 10.1038/sj.ki.5002459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Beaudry A, Ferguson TW, Rigatto C, et al. Cost of Dialysis Therapy by Modality in Manitoba. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:1197–203. 10.2215/CJN.10180917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jain AK, Blake P, Cordy P, et al. Global trends in rates of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 2012;23:533–44. 10.1681/ASN.2011060607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Karopadi AN, Mason G, Rettore E, et al. Cost of peritoneal dialysis and haemodialysis across the world. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2013;28:2553–69. 10.1093/ndt/gft214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Neil N, Walker DR, Sesso R, et al. Gaining efficiencies: resources and demand for dialysis around the globe. Value Health 2009;12:73–9. 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Osman MA, Alrukhaimi M, Ashuntantang GE, et al. Global nephrology workforce: gaps and opportunities toward a sustainable kidney care system. Kidney Int Suppl 2018;8:52–63. 10.1016/j.kisu.2017.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jarl J, Desatnik P, Peetz Hansson U, et al. Do kidney transplantations save money? A study using a before-after design and multiple register-based data from Sweden. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:283–8. 10.1093/ckj/sfx088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Organización Panameña de Transplante. Available at: http://190.34.154.93/opt/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/2015anual.pdf Accessed 27 Jul 2018.

- 27. Li PK, Chow KM, Van de Luijtgaarden MW, et al. Changes in the worldwide epidemiology of peritoneal dialysis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:90–103. 10.1038/nrneph.2016.181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carney EF. Epidemiology: Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 reports that disability caused by CKD is increasing worldwide. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015;11:446 10.1038/nrneph.2015.98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Neuen BL, Chadban SJ, Demaio AR, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global NCDs agenda. BMJ Glob Health 2017;2:e000380 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, et al. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet 2013;382:260–72. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60687-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jaspers L, Colpani V, Chaker L, et al. The global impact of non-communicable diseases on households and impoverishment: a systematic review. Eur J Epidemiol 2015;30:163–88. 10.1007/s10654-014-9983-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Morton RL, Schlackow I, Gray A, et al. Impact of CKD on Household Income. Kidney Int Rep 2018;3:610–8. 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mortality GBD; GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1459–544. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jan S, Laba TL, Essue BM, et al. Action to address the household economic burden of non-communicable diseases. Lancet 2018;391:2047–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30323-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027229supp001.pdf (291.4KB, pdf)