Abstract

Objectives

To investigate role and mechanism of microglial β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (NOX2) activation in minimally toxic dose of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and α-Synuclein (Syn)-elicited synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration.

Experimental design of the paper

NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/− mice and multiple primary cultures were treated with LPS and/or Syn in vivo and in vitro. Neuronal function and morphology were evaluated by uptake of related neurotransmitter and immunostaining with specific antibody. Levels of superoxide, intracellular reactive oxygen species, mRNA and protein of relevant molecules and dopamine were detected.

Principal observations

LPS and Syn synergistically induce selective and progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration. Microglia are functionally and morphologically activated, contributing to synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity elicited by LPS and Syn. NOX2−/− mice are more resistant to synergistic neurotoxicity than NOX2+/+mice in vivo and in vitro, and NOX2 inhibitor protects against synergistic neurotoxicity through decreasing microglial superoxide production, illustrating a critical role of microglial NOX2. Microglial NOX2 is activated by LPS and Syn as mRNA and protein levels of NOX2 subunits P47and gp91 are enhanced. Molecules relevant to microglial NOX2 activation include protein kinase C-σ, P38, extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2, c-Jun N-terminal kinase and nuclear factor-КBP50 as their mRNA and protein levels are elevated after treatment with LPS and Syn.

Conclusions

Combination of exogenous and endogenous environmental factors with minimally toxic dose synergistically propagates dopaminergic neurodegeneration through activating microglial NOX2 and relevant signaling molecules, casting a new light for the pathogenesis Parkinson disease.

Keywords: Parkinson disease, environmental factors, lipopolysaccharide, α-Synuclein, synergistic, dopaminergic neurodegeneration, microglial activation, β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2, superoxide

Introduction

In Parkinson disease (PD), the conspicuous loss of dopaminergic neurons has already occurred by the time of clinical presentation, which etiology and pathogenesis are not fully understood yet. Currently, it is generally accepted that PD is propagated by the complex interplay of multiple factors, including environmental factors, aging and genetic predisposition, in which environmental exposures greatly increase the risk of developing PD. A body of environmental factors have been demonstrated to contribute to the development of PD(Block et al. 2007), however, neither is believed to be independently sufficient to induce PD.

More recently, neuroinflammation featured by microglial activation has been implicated as an engine driving the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons(Block et al. 2007). Microglia reside in brain, comprise approximately12% of total cell and serve as the immune defense of brain(Lull ME et al. 2010). At resting state, microglia are protective for brain through surveillance of environment and removal of cell debris. However, microglia can be activated by a variety of stimuli after exposure to pathological conditions(Kannarkat GT et al. 2013).

There are more microglia with higher activity in substantia nigra (SN) comparing with other brain regions, which determines that microglia in SN are readily activated by an extensive list of exogenous environmental stimuli, such as diesel exhaust particles(Levesque S et al. 2013), paraquat(Mangano EN et al. 2012) and rotenone (Yuan YH et al. 2013), and cause deleterious effect on dopaminergic neurons. Remarkably, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria, is a very potent exogenous stimulus of microglial immune response. Mounting evidences display that LPS activates microglia and produces a line of neuroinflammatory factors in both animal and human, propagating cumulative loss of dopaminergic neurons with time extending(Gao HM et al.2002; Ling Z et al. 2006;Jung et al. 2010). Accordingly, LPS-elicited neuroinflammation and subsequent dopaminergic neurodegeneration is relevant to PD. Additionally, a variety of endogenous factors, such as neuromelanin(Zhang W et al. 2011), 6-hydroxydopamine (Bernstein et al. 2011), matrix metalloproteinase-3(Cho et al. 2009), μ-Calpain (Levesque et al. 2010), are toxic to dopaminergic neurons through microglial activation. α-Synuclein (Syn) is the major protein component of Lewy bodies (LB), the pathological hallmark of PD, in dopaminergic neurons. However, investigators observe excessive toxic oligomer Syn in the extracellular space, which may be attributed to its enhanced release driven by environmental factors as well as neurodegeneration(McGeerP et al.1988; Yamada, T et al. 1992; Kaźmierczak A et al. 2013). Our previous works have demonstrated that both aggregated(Zhang et al. 2005) and mutant Syn isoforms(Zhang et al. 2007) in the extracellular space propagate the sustained dopaminergic degeneration via surrounding microglial activation.

However, it is too late to investigate the neurodegenerative mechanisms when dopaminergic neurons are excessively exposed to above environmental factors. Thus, we ask an array of following questions: does exposure to exogenous factor (LPS) and endogenous factor (Syn) with minimally toxic dose synergistically elicit progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration? Do glia surrounding dopaminergic neurons in SN play a role in dopaminergic neurodegenerative process? Are microglia or astroglia contributable to the synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration? What are the underlying mechanisms of glial activation? Less is known about these issues yet.

In this study, we explored the role of minimally toxic dose of LPS and Syn on dopaminergic neurodegeneration both in vivo and in vitro, and investigated the potential mechanisms of microglial activation by using multiple well-established primary midbrain cultures(Zhang et al. 2011), in which we especially focused on the critical role of microglial β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 2 (NOX2), a superoxide (O2.-)-generating enzyme, by using NOX2 knock out (NOX2−/−) mice and a NOX2 inhibitor, and relevant signaling molecules of NOX2 activation.

Methods

Reagent

Materials relating cell cultures were from Invitrogen(Carlsbad, CA, USA). [3H]dopamine (DA) (28Ci/mmol) and [3H] gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (81Ci/mmol) were from Perkin Elmer Life Science (Boston, MA, USA). Polyclonal anti-tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), anti-complement receptors 3 (OX-42), anti-neuron-specific neuclear protein (Neu N), anti-protein kinase C-σ (PKC-σ), anti-P38, anti-extracellular signal-regulated kinase1/2 (ERK1/2), anti-c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and anti-nuclear factor-КBP50 (NF-КB P50) antibodies were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Anti-ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule-1 (Iba-1) antibody was from Abcam (330 Cambridge Science Park, Cambridge, UK). Vectastain ABC kit and biotinylated secondary antibodies were from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA, USA); Fluorescence probe 2’,7’-dichlorodi-hydrofluorescein (DCFH-DA), cytosine arabinoside (Ara-C), Leu-Leu methyl ester hydrobromedia (LME), superoxide dismutase (SOD), 2-(4 lodophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)-5-(2,4-disulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazo1ium (WST-1) and diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). SYBR green PCR master mix was from Applied Biosystems (Foster City, CA, USA).

Animals

SD rats were from Peking Vital River Laboratory and Centre of Experimental Animal of Peking University. C57 BL/6J (NOX2 wild type, NOX2+/+) and NOX2−/− mice were from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, Maine, USA). Breeding schedules were designed to achieve accurately timed-pregnancy of 14 ± 0.5 days for rats and 13 ± 0.5 days for mice. Housing, breeding and experimental use of the animals were performed in strict accordance with the National Institutes of Health guidelines.

Primary midbrainneuron-glia (neuron-microglia-astroglia) cultures

Primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures were prepared from the brains of embryonic day 14 ± 0.5 days of SD rats and 13 ± 0.5 days of NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/− mice. Ventral midbrain tissues were removed and dissociated. Cells were seeded at culture plate precoated with poly-D-lysine and maintained at 37°C incubator with humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Seven-day cultures were used for treatment. The composition of the cultures included about 48% astroglia, 11% microglia and 40% neurons, of which 2–3% was TH-immunoreactive (TH-ir) dopaminergic neurons (see Supplemental Material, p. 1).

Primarymidbrain neuron-enriched cultures

Rat primarymidbrain neuron-enriched cultures, with a purity of > 95%, were established as described previously (Zhang W. 2005). Briefly, 1 day after seeding neuron-glia cultures, Ara-C was added to at a final concentration of 7.5 μM to suppress glial proliferation, and 3 days later, cultures were changed back to maintenance medium. Seven days after initial seeding, cultures were used for treatment.

Primarymidbrain neuron-astroglia cultures (microglia-depleted cultures)

Primarymidbrain neuron-astroglia cultures, with 54% astroglia, 1% microglia and 45% neurons, were established as described previously (Zhang W. 2005). Briefly, 1 day after seeding neuron-glia cultures, LME was added at a final concentration of 1.5 mM to suppress microglia proliferation, and 3 days later, cultures were changed back to maintenance medium. Seven days after initial seeding, cultures were used for treatment.

Primary mixed glia cultures, microglia cultures and astroglia cultures

Whole brains tissues of 1-d-old pups from SD rats, NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/− mice were triturated after removing meninges and blood vessels. Cells were seeded in a 150 cm2 culture flask. After a confluent monolayer of primary glia cultures were obtained, microglia were shaken off and seeded in culture plate. After at least 4 separations of microglia, astroglia were detached with trypsin-EDTA and seeded in the same culture medium as that used for microglia (see Supplemental Material, p. 2).

Primary microglia-reconstituted cultures and astroglia-reconstituted cultures

Primary microglia-reconstituted cultures were established by adding 10% (5.0×104/well) and 20% (1.0×105/well) of microglia back to neuron-enriched cultures 1 day before treatment. Primary astroglia-reconstituted cultures were established by adding 40% (2.0×105/well) and 50% (2.5×105/well) of astroglia back to neuron-enriched cultures 1 day before treatment(Zhang W. 2005).

Treatment

Minimally toxic dose of Syn or LPS produces minor damage to dopaminergic neurons functionally and morphologically, which is not statistically significant compared with normal control.

In our previous study, commercially purified Syn was aged in PBS at 37°C for 0–14 days. Remarkably, at day 7 of aging, most Syn aggregates were oligomers detected by Western blot and electron microscopic examination(Zhang W. 2005). We found that the minimally toxic dose of Syn was 20 nmol/L. LPS was freshly prepared as a stock solution with PBS and diluted to the minimally toxic dose of 0.5 ng/mL in the treatment medium based on our previous work. Multiple cultures were treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L) in a final volume of 1 mL/well for 8 days.

Neurotoxicity measurement by [3H] DA and [3H] GABA uptake assays

Primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures treated with LPS and/or Syn for 8 days were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C with 1 μM [3H] DA or GABA in Krebs-Ringer buffer. After washing 3 times with ice-cold Krebs-Ringer buffer, cells were collected in 1N NaOH. Radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. Nonspecific DA and GABA uptake observed in the presence of mazindol, and NO711 with β-alanine, respectively, was subtracted(see Supplemental Material, p. 2).

Immunostainings

Primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures exposed with LPS and/or Syn for 8 days were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde, treated with 1% hydrogen peroxide followed by sequential incubation with blocking solution, related primary antibodies, biotinylated secondary antibodies and ABC reagents. Color was developed and images were recorded. TH-ir dopaminergic neurons in a well, Neu N-ir total neurons, OX-42-ir microglia and dendrite length in 9 representative areas per well were visualized under microscope at ×100 magnification (see Supplemental Material, p. 2).

O2.- assay

Primary microglia cultures were seeded for 1 day, washed 2 times with Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS) and treated with LPS and/or Syn followed by WST-1 in HBSS with or without SOD. The absorbance at 450 nm was read for a period of 40 min. O2.−level was measured by the increased absorbance in 30 minutes and expressed as the percentage of control group (see Supplemental Material, p. 3).

iROS assay

Primary microglia cultures were seeded for 1 day, washed for 2 times with HBSS, incubated with DCFH-DA for 2 hours at 37°C and finally treated with vehicle, LPS and/or Syn. Fluorescence intensity was measured at 485 nm for excitation and 530 nm for emission. iROS level was measured by the increased absorbance in 2 hours and expressed as the percentage of control group(see Supplemental Material, p. 3).

RT and real-time PCR

mRNA levels of microglial NOX2 subunits P47and gp91, PKC-σ, P38, ERK1/2, JNK and NF-КBP50after LPS and/or Syn treatment were detected by RT and real-time PCR, which sequences of forward and reverse primers were as followed:

β-actin:5’-GAGACCTTCAACACCCCAGC-3’ (F), 5’-ATGTCACGCACGATTTCCC-3’ (R);

P47:5’-ACCTGAAGCTGCCCAATGAC-3’ (F),5’-ATGGCCCGATAGGTCTGAAG-3’(R);

gp91:5’-GACAGATTTGCTCTGCACAAGGT-3’(F),5’-AGGAGAGGTTGTGTGCACCATAG-3’(R);

PKC-σ: 5’-TCCCCGCCATCCGAGCAACA-3’(F), 5’-TTGCGGCATCTCTCCGCCAG-3’(R);

P38: 5’-TGGCTCGGCACACTGATGAC-3’(F), 5’-CCGGTCAACAGCTCAGCCAT-3’(R);

ERK1/2:5’-GACCCTGAGCACGACCACAC-3’ (F), 5’-ATAGGCCGGTTGGAGAGCAT-3’(R);

JNK:5’-CCCACCACCAAAGATCCCTG-3’ (F), 5’-TGACAGACGGCGAAGACGAC-3’(R);

NF-КBP50:5’-GCCGGCCTCGGGACAAACAG-3’(F),5’-TCGCCAGAGGCGGAAATGCG-3’(R).

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent, followed by purification, reversed transcription and real-time PCR analysis. Relative differences in expressions between groups were determined by cycle time (Ct) values as follows: Ct values for the genes of interest were first normalized with β-actin of same sample, then relative differences between control and LPS and/or Syn-treated groups were calculated and expressed as the percentage of control. Standard curve analysis was performed and used for the calculation(see Supplemental Material, p. 4).

Western blot

Primary microglia cultures treated with LPS and/or Syn were detached by scraping in sampling buffer.NOX2 subunits P47and gp91, PKC-σ, P38, ERK1/2, JNK and NF-КBP50 were isolated via acid extraction adjusted to equal protein concentrations and separated by 4–12% polyacrylamide-0.1% SDS miningels, then were transferred onto a PVDF membrane. Blots were incubated with related primary antibody, then probed with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Detection was performed by using ECL kit.

Animal studies

Eight-week-old NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/− mice were kept on a 12-hour light/dark cycle with ad libitum access to food and water and acclimated to their environment for 2–4 week before use. Mice (25–30 g) received vehicle saline, Syn (0.0125 ug/uL) and/or LPS (0.2 ug/uL). For SNpc injection, mice were deeply anesthetized by chloral hydrate (300 mg/kg, s.c.), then fixed on stereotaxic frame. LPS was injected bilaterally to 0.7 mm anterior from bregma, 1.0 mm lateral from midline and 3.4 mm from dura. Mice were sacrificed 4 weeks later. Striatal tissues were rapidly dissected, immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at −80°C until use. The rest of the brain was fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde followed by cryoprotection in 30% sucrose before use.

Immunohistochemistry and cell counting

Immunohistochemistry and cell counting were conducted as described previously(Liu, B. 2000). Briefly, coronal sections (35 μm) covering entire SN and striatum were obtained. After blocking, sections were incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-TH and anti-Iba1 antibodies followed by biotinylated secondary antibody and Vectastain ABC reagents. The first (rostral) and every forth section of 24 sections of each brain from 8animals for each group were counted under microscope at×100 magnification. Mean value of the numbers of TH-ir dopaminergic neurons and Iba1-ir microglia in SNpc were deduced by averaging the counts of6 sections for each animal. Results were expressed as the percentage of control group (see Supplemental Material, p5).

Analysis of DA level in striatum

DA level in striatum was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with electrochemical detection as described (Ali, S. F. 1994). Briefly, striatal tissues were sonicated in 0.2 M perchloric acid (20% W/V), containing internal standard 3,4-dihydroxybenzylamine (10 mg wet tissue/ml). The homogenate was centrifuged and 20 μl aliquot of supernatant was injected into HPLC equipped with a 3 μm C18 column. Mobile phase was comprised of 26 ml of acetonitrile, 21 ml of tetrahydrofuran and 960 ml of 0.15 M monochloroacetic acid (PH 3.0), containing 50 mg/L of EDTA and 200 mg/L of sodium octyl sulfate. DA level was determined by comparison of peak height ratio of tissue sample with standards and expressed as the percentage of control group.

Statistical Analysis

Three wells were used in each treatment, which was considered as an independent experiment. Standard errors were calculated from 3 independent experiments. Results were expressed as the mean ± SE. Statistical significance was assessed with an analysis of one-way ANOVA, with the freedom representing the numbers of experiments minus one, followed by Bonferroni’s t-test using SPSS20.0 software. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

LPS and Syn synergistically elicit dopaminergic neurotoxicity through multiple manners

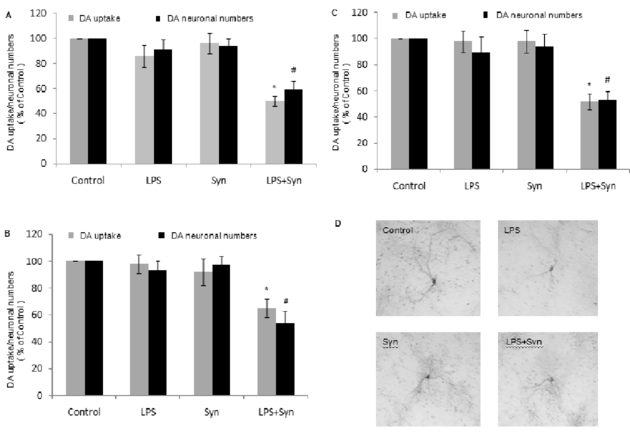

In the real word, we may be exposed to the environmental factors in different way, thus, in this investigation, rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures were treated with LPS and Syn in three methods: simultaneous treatment with LPS and Syn for 8 days, 4 days of LPS followed by 4 days of Syn and 4 days of Syn followed by 4 days of LPS. Control, LPS, Syn, and LPS+Syn groups were included in each method. The results indicate that, comparing with either LPS or Syn group, LPS+Syn group synergistically reduces DA uptake and dopamniergic neuronal numbers in above treatment methods (Fig.1A, 1B, 1C), and causes damage to dopaminergic neurons morphologically indicated by the small cell bodies, reduced cytoplasmic stainings and shortened dendrites (Fig. 1D, 1E).

Figure 1. LPS and Syn synergistically elicit dopaminergic neurotoxicity through multiple manners.

Rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures were seeded in a 24-well plate at 5× 105 /well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L) in three methods: simultaneous treatment with LPS and Syn for 8 days (A), 4 days of LPS followed by 4 days of Syn (B) and 4 days of Syn followed by 4 days of LPS (C). Control, LPS, Syn, and LPS+Syn groups were includedin each method. Eight days after treatment, effects of LPS and/or Syn on dopaminergic neurons were assessed with [3H]DA uptake and TH staining. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ±SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 forLPS+Syn groupvs.LPS or Syn group. Representative microscopic images are shown for dopaminergic neurons (TH staining, 100 × magnification). Scale bar=100μm (D).

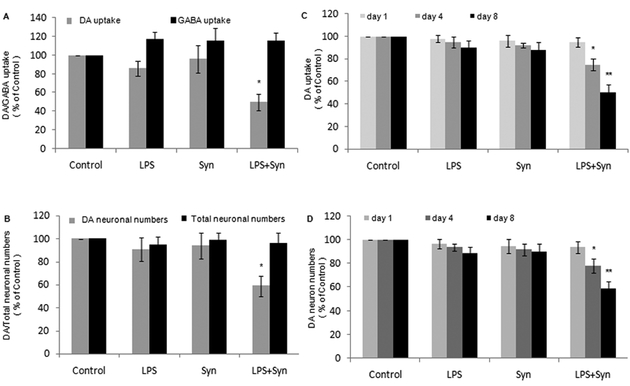

Synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn is selective and progressive

LPS and Syn synergistically elicit dopaminergic neurotoxicity, we then raised two questions here: is this neurotoxicity selective to dopaminergic neurons? is this neurotoxicity progressive with time extending? We found that, in rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures, comparing with LPS or Syn group, GABA uptake is largely preserved comparing with DA uptake (Fig. 2A), and Neu N-ir total neurons are mostly saved comparing with TH-ir dopamniergic neurons in LPS+Syn group (Fig. 2B); meanwhile, DA uptake and TH-ir dopamniergic neurons in LPS+Syn group are significantly reduced with time extending, in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2C, 2D).

Figure 2. Synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPSandSynis selective and progressive.

Rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures were seeded in a 24-well plate at 5× 105 /well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L) for 8 days. Dopaminergic and GABA neuronswere assessed with [3H]DA and [3H]GABA uptakes, respectively (A). Dopaminergic neurons and total neurons were counted after TH and Neu N staining, respectively (B). Dopaminergic neurons were evaluated by measuring [3H]DAuptake (C) and counting neuronal numbers (D) 1,4 and 8 day (s) after treatments with LPS and/or Syn. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group.

Microglia are the major players for the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity elicited by LPS and Syn

LPS and Syn synergistically induce dopaminergic neurotoxicity in rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures, we next used different cell cultures to identify the role of each cell type in neurotoxicity.

Comparing with LPS or Syn group, DA uptake in rat primary neuron-enriched cultures is remarkably spared comparing with that in neuron-glia cultures in LPS+Syn group (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Microglia are the major players for the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity elicited by LPS and Syn.

Rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures and neuron-enriched cultures (5× 105 /well) (A), rat primary midbrain neuron-astroglia cultures, 40% (2.0×105/well) and 50% (2.5×105/well) astroglia-reconstituted cultures (B), microglia-depleted cultures, 10% (5.0×104/well) and 20% (1.0×105/well) of microglia-reconstituted cultures (C) were seeded in a 24-well plate and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L).Eight days later, [3H]DA uptake were measured. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ±SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group.

In rat primary midbrain neuron-astroglia cultures by depleting microglia, DA uptake in LPS+Syn group is not different with that in LPS or Syn group (Fig. 3B). In the reconstituted cultures with 40% and 50% astroglia back to neuron-enrichend cultures, DA uptake in LPS+Syn group shows no discrepancy comparing with that in LPS or Syn group (Fig. 3B).

In rat primary microglia-depleted cultures, DA uptake in LPS+Syn group displays no marked difference comparing with LPS or Syn group (Fig. 3C).In the reconstituted cultures with 10% and 20% microglia back to neuron-enrichend cultures, the more the microglia added, the greater the DA uptake abolished (Fig. 3C).

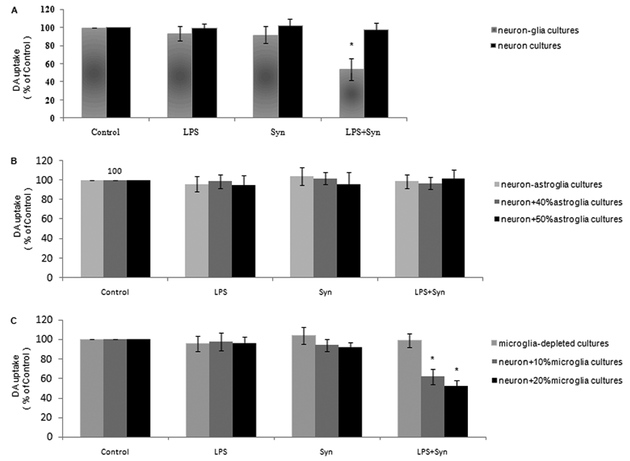

LPS and Syn elicit progressive microglial activation functionally and morphologically

Why microglia served as the major players for the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity elicited by LPS and Syn? We furtherly explored the functional and morphological changes of microglia after treatment with LPS and Syn.

In rat primary microglia cultures, extracellular O2.−and iROS in LPS+Syn group are robustly produced 30 minutes and 2 hours, respectively, comparing with that in LPS or Syn group (Fig. 4A, 4B).In rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures, activated microgliain LPS+Syn group are gradually enhanced with time extending comparing with that in LPS or Syn group (Fig. 4C). Comparing with LPS or Syn group, microglia in LPS+Syn group are essentially activated morphologically, which is indicated by the enlarged cell bodies, irregular shape and intensified OX-42 stainings (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. LPS and Syn elicit progressive microglial activation functionally and morphologically.

In rat primary microglia cultures, the levels of extracellular O2•– (probed with WST-1) (A) and iROS (probed with DCFH-DA) (B) were determined 30 minutes and 2 hours, respectively, after treatments with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L). In rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures treated with LPS and/or Syn for 1, 4 and 8 day (s), microglia were counted and visualized (C) after OX-42 staining. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05a and **P<0.05 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group. Representative microscopic images are shown for dopaminergic neurons (TH staining, 100 × magnification). Scale bar=100μm (D).

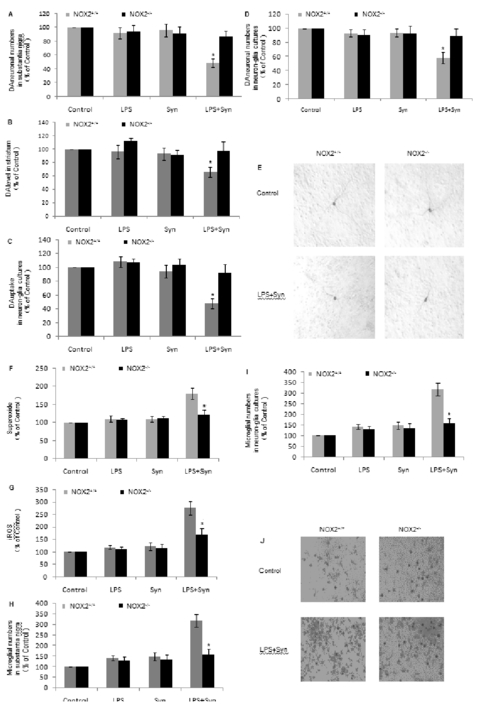

NOX2−/− mice are more resistant to the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn due to the less microglial activation

NOX2 is a ROS-generating enzyme in microglia, which is easily activated and produces oxidative stress after exposure to various of toxic elements. Is microglial activation elicited by LPS and Syn through NOX2? We performed a line of investigation both in vivo and in vitro by using NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/−mice.

Nigral dopaminergic neurons and striatal DA in LPS+Syn group in NOX2+/+mice are greatly NOX2−/−mice and the indecreased comparing with that in NOX2−/−mice (Fig. 5A,5B). DA uptake and TH-ir dopamniergic neuronsin LPS+Syn group in primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures derived from NOX2+/+mice are significantly reduced comparing with that in the cultures derived from NOX2−/−mice (Fig. 5C,5D). Comparing with NOX2−/−mice, the morphologies of dopaminergic neurons in LPS+Synin primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures in NOX2+/+mice are drastically damaged, which is indicated by small cell bodies, reduced cytoplasmic stainings and decreased, shorter dendrites (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5. NOX2−/− mice are more resistant to the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn due to the less microglial activation.

NOX2+/+ and NOX2−/− mice were treated with vehicle saline, Syn (0.0125 ug/uL) and/or LPS (0.2 ug/uL) in substantia nigra. The numbers of dopaminergic neurons (A) and microglia (H) in substantia nigra were counted after TH and Iba-1stainings respectively, and DA level in striatum was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (B). Results are expressed as a percentage of the saline-injected control group and are the mean ±SE from8mice in each group. Primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures derived from NOX2+/+and NOX2−/− mice were seeded in a 24-well plate at 5× 105 /well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L) for 8 days;Dopaminergic neurons were quantified by measuring [3H] DA uptake (C) and counting neuron numbers after TH staining (D); microglia were visualized after OX-42 staining(I). Microglial cultures derived from NOX2+/+and NOX2−/− mice were treated with LPS and/or Syn, and the levels of extracellular O2•– (probed with WST-1) (F) and iROS (probed with DCFH-DA) (G) were measured 30 minutes and 2 hours later, respectively. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ±SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group. Representative microscopic images of dopaminergic neurons (TH staining, 100 × magnification) (E) and microglia (OX-42 staining, 100 × magnification) (J) are shown. Scale bar=100 μm.

The levels of O2.−and iROS in LPS+Syn group in primary microglia cultures derived from NOX2+/+ mice are evidently increased 30 minutes and 2 hours later, respectively, comparing with that in the cultures derived from NOX2−/− mice (Fig.5F, 5G).

Activated microglia in LPS+Syn group in substantia nigra and neuron-glia cultures inNOX2+/+ mice are remarkably enhanced comparing with that inNOX2−/−mice (Fig.5H, 5I). Microglia derived from NOX2+/+ mice in LPS+Syn group are strikingly activated morphologically comparing with that in the cultures derived fromNOX2+/+ mice (Fig. 5J).

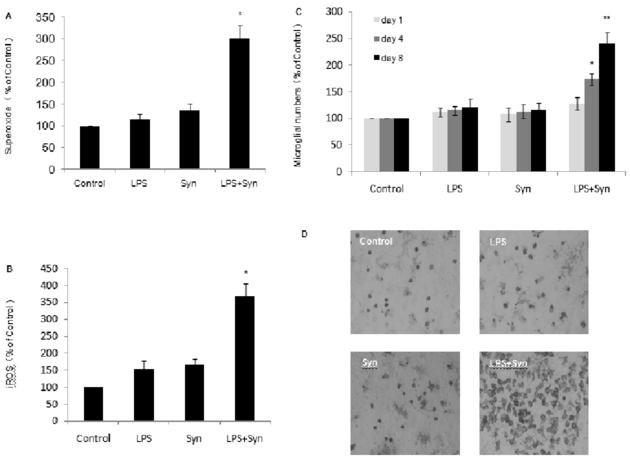

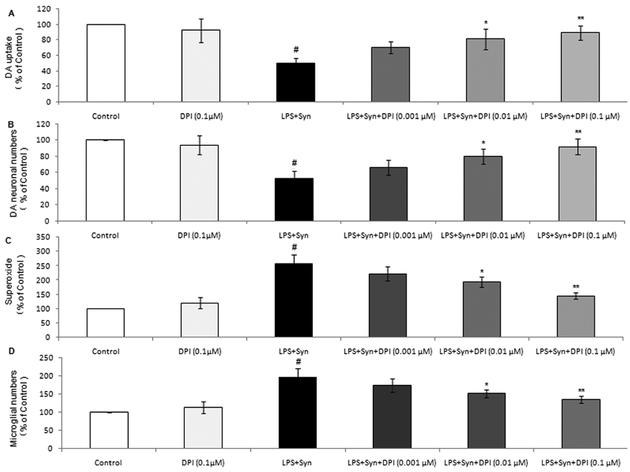

Microglial NOX2 inhibitor alleviates microglial activation induced by LPS and Syn and protects dopaminergic neurons

The novel findings that NOX2−/− mice are more resistant to the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn due to the less microglial activation imply the pivotal role of NOX2. Here, we used NOX2 inhibitor to further confirm this conclusion.

In rat primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures, DA uptake and TH-ir dopaminergic neurons in LPS+Syn group are conspicuously reduced 8 days after treatment comparing with LPS or Syngroup. Pretreatment with DPI, a potential NOX2 inhibitor, at 0.01 and 0.1 μM significantly increases DA uptake and restores dopaminergic neuronal survival (Fig. 6A, 6B). 0.1 μM DPI alone shows no significant effect on both DA uptake and dopaminergic neuronal numbers (Fig. 6A, 6B).

Figure 6. Microglial NOX2 inhibitor alleviates microglial activation induced by LPS and Syn and protects dopaminergic neurons.

Rat primary midbrain neuron-microglia-astroglia cultures were seeded in a 24-well plate at 5 × 105/well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L). Eight days later, effect of NOX2 inhibitor DPI (0.001, 0.01 and 0.1 μM, added 30 minutes before LPS and/or Syn treatment) on dopaminergic neurons were assessed by [3H]DA(A) and neuron countingafter TH staining (B). Rat microglial cultures were seeded in a 96-well plate at 1 × 105/welltreated withLPS and/or Syn. Effect of DPI on microglial activation was assessed by measuring the levelsof extracellular O2.- (C) and counting the numbers of microglia (D). Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. #P<0.05 for LPS+Syn group vs.control group,*P<0.05 and **P<0.01 for DPI pre-treatment groups vs. LPS+Syn group.

In rat primary microglia cultures, the levels of O2.−and iROS in LPS+Syn group are remarkably enhanced 30 minutes and 2 hours after treatment, respectively. Pretreatment with DPI at 0.01 and 0.1 μM 30 minutes before treatment with LPS and Syn drastically decreases O2.−leveland activated microglial numbers (Fig. 6C, 6D) .0.1 μM DPI alone exerts no significant effect on O2.- productions and microglial numbers (Fig. 6C, 6D).

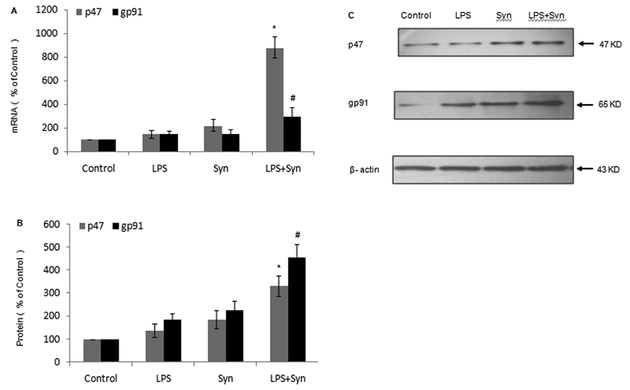

Expressions of NOX2 cytoplasm subunit P47 and cell membrane subunit gp91 are elevated by LPS and Syn

There are several subunits of NOX2, among which, P47 and gp 91 are the important subunits located in cytoplasm and cell membrane, respectively. Are the expressions of these two subunits elevated after NOX2 activated by LPS and Syn?

In rat primary microglia cultures, mRNA and protein levels of NOX2 cytoplasm subunit P47 and cell membrane subunit gp91in LPS+Syn group are observably enhanced 20 minutes and 25 minutes after treatment, respectively (Fig. 7A, 7B, 7C).

Figure 7. Expressions of NOX2 cytoplasm subunit P47 and cell membrane subunit gp91 are elevated by LPS and Syn.

Rat primary microglial cultures were seeded in a 6-well plate at 2 × 106/well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L).20 minutes later, mRNA expressions of NOX2 cytoplasm subunit P47 and cell membrane subunit gp91 were measured by Real-time PCR (A); 25 minutes later, protein expressions of P47and gp91 were measured by Western blot (B). Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group. Representativepictures of protein expressions of P47 and gp91 by Western blot are shown (C).

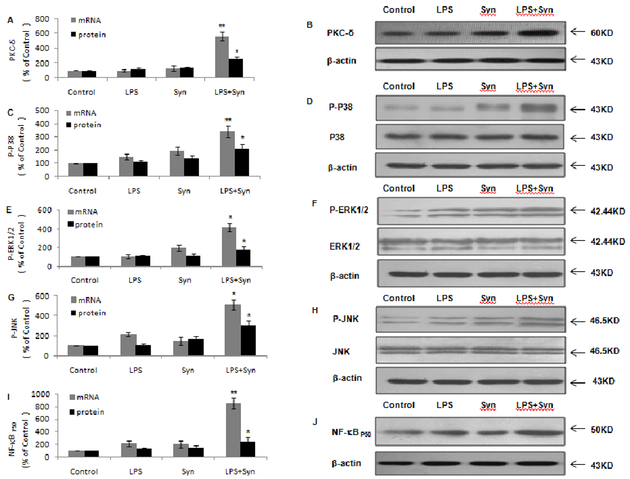

Expressions of PKC-δ, P38, ERK1/2, JNK and NF-κBP50 are upregulated by LPS and Syn

PKC-δ, P38, ERK1/2, JNK and NF-κB are the molecular involved in neurodegenerative disorders. It has never been investigated whether these molecular are relevant to NOX2 activation by LPS and Syn.

In rat primary microglia cultures, mRNA and protein levels of PKC-δ at 3and5 minutes, (Fig. 8A, 8B), P38 (Fig. 8C, 8D), ERK1/2 (Fig. 8E, 8F) and JNK (Fig. 8G, 8H) at 10and 15 minutes, and NF-κBP65at 2 and3 hours (Fig. 8I, 8J) in LPS+Syn group are drastically upregulated comparing with LPS or Syn group.

Figure 8. Expressions of NOX2 cytoplasm subunit P47 and cell membrane subunit gp91 are elevated by LPS and Syn.

Rat primary microglial cultures were seeded in a 6-well plate at 2 × 106/well and treated with LPS (0.5 ng/mL) and/or Syn (20 nmol/L). mRNA levels of PKC-δ 3 minutes after treatment, P38 (C), ERK1/2 (E) andJNK (G) 10 minutes after treatment andNF-κBP50 2 hours after treatment were detected by Real-time PCR, respectively. Proteinlevels of PKC-δ 5 minutes after treatment, P38 (C), ERK1/2 (E) and JNK (G)15 minutes after treatment and NF-κBP503 hours after treatment (I) were detected by Western blot, respectively. Results are expressed as a percentage of the vehicle-treated control group and are the mean ± SE from 3 independent experiments in triplicate. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 for LPS+Syn group vs. LPS or Syn group. Representative pictures of protein expressions of PKC-δ (B), P38 (D), ERK1/2 (F), JNK (H) and NF-κBP50 (J) by Western blot are shown.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the role of minimally toxic dose of LPS and Syn on dopaminergic neurodegeneration both in vivo and in vitro, and the underlying mechanisms of microglial NOX2activationand relevant signaling molecules by using knockout mice and inhibitor of NOX2.

Rodent primary midbrain neuron-glia cultures with the composition similar to human is a well-established tool for studying the pathogenesis of dopaminergic neurodegeneration in PD. Function of dopaminergic neuron is assessed by the uptake of neurotransmitter DA and the morphology is evaluated by TH staining. In this study, LPS and Syn synergistically decrease DA uptake and TH-ir dopaminergic neuronal numbers when comparing with LPS or Synalone,8 days after treatment in three manners. Morphologically, dopaminergic neuronal bodies are shrunk, cytoplasmic stainings are reduced, neuronal dendrites are decreased, shortened, broken and even disappeared. These data indicate that LPS and Syn cause synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration both functionally and morphologically.

Effects of LPS and Syn on dopaminergic and GABA neurons are compared by measuring uptake capacities of DA and GABA and visualizing the numbers of TH-ir dopaminergic neurons and NeuN-ir total neurons. Although Neu N is a marker of all neurons, it is used for assessing non-dopaminergic neurons because dopaminergic neurons merely account for 2%~3% of total neurons in SNpc. Data from this study indicate that DA uptake capacity is robustly decreased when comparing with GABA uptake capacity, and dopaminergic neuronal numbers are greatly reduced when comparing with NeuN-ir total neurons, demonstrating that neurodegeneration elicited by LPS and Syn is relatively selective to dopaminergic neurons. Furthermore, DA uptake capacity and dopaminergic neuronal numbers are gradually reduced with time extending, indicating that LPS and Syninduce progressive dopaminergic neurodegeneration.

LPS and Syn induce synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity in primary neuron-microglia-astroglia cultures, however, it is not clear whether the neurotoxicity is attributed to their direct effect on dopaminergic neurons or indirect effect via microglial activation. These questions have been answered by using multiple primary cell cultures. Firstly, inprimary neuron-enriched cultures, synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity is not found after treatment with LPS and Syn, implying that glial cells, astroglia or microglia, may play a critical role. Secondly, in neuron-astroglia cultures by depleting microglia or in reconstituted cultures with different percentage of astroglia added to neuron-enriched cultures, dopaminergic neurotoxicity is not observed after stimulation with LPS and Syn, indicating that astroglia are not the player in the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Finally, treatment with LPS and Synis not toxic to dopaminergic neuronsin microglia-depleted cultures, whereas, is dramatically toxic in microglia-reconstituted cultures, in a percentage-depedent manner, illucidating that microglia are the contributors for the synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn.

Increasing evidences show that, upon some stimuli, microglia are activated and generate a line of neuroinflammatory factors(Zhang W et al.2005; Zhang W et al. 2007; Zhang W et al. 2011),which may be relevant to dopaminergic neurotoxicity in PD. However, it has not been investigated how microglia induce synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity after treatment with LPS and Syn. Our data show that, upon stimlation with LPS and Syn, microglia generate magnitude of neurotoxic ROS, in which, extracellular O2.- is the factor quickly produce dafter activation of NOX2, the key O2.--producing enzyme in brain microglia(Infanger et al. 2006). O2.−can promote the generation and release of downstream neuroinflammatory factors such as TNF-α(Qin et al. 2007) and PGE2(Zhang et al. 2005) through formation of hydrogen peroxide(McGeer and McGeer 2008; Ouchi et al. 2009). Hence, O2.- generated by microglial NOX2 may be the potential trigger of dopaminergic neurotoxicity mediated by LPS and Syn. Mounting evidences illustrate pivotal role of iROS as a second messenger in the cascade event of neuroinflammation(Zhang et al. 2011). Multiple sources contribute the production of iROS, among which, NOX2-generating O2.−account for the most of total iROS(Block 2008). It is demonstrated that iROS initiates the upregulation of NF-КB, which subsequently produces an array of neuroinflammatory factors. Each neuroinflammatory factor may not be sufficient in the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons, however, they may work together and intensify the neurotoxic effect of each other, propagating dopaminergic neurotoxicity (data not shown). Morphologically, microglial are activated by LPS and Syn, which is featured by the enlarged cell bodies, irregular cell shape, intensified OX-42 staining and increased number with time extending. Thus, microglial activation may be an engine driving the synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration during the entire degenerative process.

NOX family is composed of NOX1~5 and Dual Oxidase 1~2(Infanger et al. 2006), among which, NOX2 is mainly distributed in brain regions of SN, striatum, hippocampus and cortex (Tammariello et al. 2000). Previous investigations show that, in a LPS in vitro model, microglia derived from NOX2+/+ mice produce more O2.−and neuroinflammatory factors than that derived from NOX2−/− mice, thus, it is the activation of NOX2 in micoglia but not in astroglia and neurons, that causes toxic effect to dopaminergic neurons(Block 2008; Qin et al. 2004). Results from this investigation demonstrate that synergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity induced by LPS and Syn is indicated by significantly reduced DA uptake capacity, dopaminergic neuronal numbers in SNpc and depleted DA level in striatum in NOX2+/+ mice compared with NOX2−/− mice. Furthermore, comparing with NOX2−/− mice, microglial productions of O2.- and iROS are robustly elicited and activated microglia are prominently enhanced in NOX2+/+mice,implying that microglia are the major sources of NOX2-generated O2.- after stimulation with LPS and Syn.. Simultaneously, data from this study indicate that DPI, a potential NOX2inhibitor, protects against dopaminergic neurodegeneration synergistically provoked by LPS and Syn, which is revealed by the dramatically preserved DA uptake and restored dopaminergic neuron through reducing O2.−generation and activated microglia. Thus, the progressive and selective dopaminergic neurodegeneration synergistically induced by LPS and Syn is microglial NOX2-dependent.

What are the potential molecular mechanisms of microglial NOX2 activation elicited by LPS and Syn?P47 and gp91are two critical subunits for NOX2 activation, which are located in cytoplasm and cell membrane separately in resting state(Sorce and Krause 2009). However, P47translocates to membrane and combines with gp91 when exposed to various of stimuli, during which O2.−is produced. In this study, levels of mRNA and protein levels of P47 and gp91 are strikingly upregulated20 minutes and 25 minutes after exposure to LPS and Syn, respectively, revealing the significance of microglial NOX2 activation insynergistic dopaminergic neurotoxicity.

PKC, MAPKs and NF-КB are reported to be the potential signaling pathways relating to neurodegenerative diseases(Kozikowski et al. 2003) and neuroinflammation(Miller et al. 2009). PKC-δ, a member of PKC family, is observed to has an relevance to microglial NOX2 activation in PD(Zhao et al. 2005). Activity of microlgial NOX2 is reduced for more than 90% when expression of PKC-δ is largely inhibited(Bey et al. 2004). ROS level is attenuated by GF109203X, a PKC-δ inhibitor in addition to DPI (Min et al. 2004). PKC-δ is found to enhance P47 expression and provoke translocation of P47 from cytoplasm to membrane (Zhao et al. 2005). Accordingly, PKC-δmay be a potential signaling molecule for microglial NOX2 activation.In this investigation, mRNA and protein levels of PKC-δ are robustly elevated as early as 3 and 5 minutes after treatment with LPS and Syn, respectively, implying that PKC-δ is an earliest molecule triggering microglial NOX2 activation after stimulation with LPS and Syn. MAPKs includes several molecules, including P38, ERK1/2 and JNK, which can be activated by a host of environmental factors(Murphy and Blenis 2006; Zhang et al. 2005)and correlated with the elevated expressions of a variety of neuroinflammatory proteins that are highly relevant to microglial NOX2 activation (Bardwell 2006). In this study, both mRNA and protein levels of P38, ERK1/2 and JNK are significantly increased10 and 15 minutes, respectively, after stimulation with LPS and Syn, which are prior to that of P47 and gp91, illustrating that MAPKs are the next signaling molecules of microglial NOX2 activation induced by LPS+Syn. NF-КB, a neuclear transcription factor, initiates the generations of series of downstream neuroinflammatory factors(Flohe et al. 1997). A close relationship between NF-КB and NOX2 has been demonstrated through attenuating NF-КB activation by NOX2 inhibitor(Flohe et al. 1997). NF-κB has cross talks with MAPKs and PKC (Yang et al. 2006). In this investigation, mRNA and protein levels of NF-КBp50 are significantly elevated 2 and 3 hours, respectively, after stimulation with LPS and Syn. We speculate that NOX2-generated O2.- byLPS+Syn enters microglia and elevates iROS level, triggers the upregulation of NF-КB p50and production of neuroinflammatory factors, and causes the synergistic dopaminergic neurodegeneration.

Conclusion

In brief, results from this investigation elucidate that combination of exogenous and endogenous environmental factors with minimally toxic dose synergistically propagates dopaminergic neurodegeneration through activating microglial NOX2. Thus, PD is the outcome of multiple etiologies through neuroinflammatory mechanism. Inhibition of microglial NOX2 activation elicited by various of environmental factors may be a novel target for PD therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30770745, 81071015, 81571229), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, China (7082032), Key Project of Beijing Natural Science Foundation, China (kz201610025030, ,4161004, kz200910025001), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2011CB504100), National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2013BAI09B03),The project of Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders (BIBD-PXM2013_014226_07_000084), High Level Technical Personnel Training Project of Beijing Health System, China (2009-3-26), The Project of Construction of Innovative Teams and Teacher Career Development for Universities and Colleges Under Beijing Municipality (IDHT20140514), Capital Clinical Characteristic Application Research (Z121107001012161), the Beijing Healthcare Research Project, China (JING-15–2, JING-15–3), Excellent Personnel Training Project of Beijing, China (20071D0300400076), Important National Science & Technology Specific Projects (2011ZX09102-003-01), Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81030062) and Basic-Clinical Research Cooperation Funding of Capital Medical University (2015-JL-PT-X04, 10JL49, 14JL15), Youth Research Fund, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China (2014-YQN-YS-18, 2015-YQN-15, 2015-YQN-05, 2015-YQN-14, 2015-YQN-17).

Footnotes

This work was performed at Beijing Tian Tan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China

Reference

- Block ML, Zecca L, Hong JS. Microglia-mediated neurotoxicity: uncovering the molecular mechanisms. Nat Rev Neurosci.2007;8 (1) : 57–69. doi: 10.1038/nrn2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lull ME, Block ML. Microglial activation and chronic neurodegeneration. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7(4):354–365. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannarkat GT, Boss JM, Tansey MG. The role of innate and adaptive immunity in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis. 2013;3(4):493–514. doi: 10.3233/JPD-130250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Taetzsch T, Lull ME, Johnson JA, McGraw C, Block ML. The role of MAC1 in diesel exhaust particle-induced microglial activation and loss of dopaminergic neuron function. J Neurochem. 2013;125(5):756–765. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12231. Epub 2013 Apr 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangano EN1, Litteljohn D, So R, Nelson E, Peters S, Bethune C, Bobyn J, Hayley S. Interferon-γ plays a role in paraquat-induced neurodegeneration involving oxidative and proinflammatory pathways.Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33(7):1411–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.02.016. Epub 2011 Apr 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YH1, Sun JD, Wu MM, Hu JF, Peng SY, Chen NH. Rotenone could activate microglia through NFκB associated pathway.Neurochem Res. 2013;38(8):1553–1560. doi: 10.1007/s11064-013-1055-7. Epub 2013 May 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao HM, Jiang J, Wilson B, Zhang W, Hong JS, Liu B. Microglial activation-mediated delayed and progressive degeneration of rat nigral dopaminergic neurons: relevance to Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2002;81(6):1285–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Z, Zhu Y, Tong CW, Snyder JA, Lipton JW, Carvey PM. Progressive dopamine neuron loss following supra-nigral lipopolysaccharide (LPS) infusion into rats exposed to LPS prenatally. Exp Neurol. 2006;199(2):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung BD, Shin EJ, Nguyen XK, Jin CH, Bach JH, Park SJ,Nah SY, Wie MB, Bing G, Kim HC. Potentiation of methamphetamine neurotoxicity by intrastriatal lipopolysaccharideadministration. Neurochem Int. 2010;56(2): 229–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.10.005. Epub: 2009 Oct 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Phillips K, Wielgus AR, Liu J, Albertini A, Zucca FA Faust R, Qian SY, Miller DS, Chignell CF, Wilson B, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Joset D,Loike J, Hong JS, Sulzer D, Zecca L.Neuromelanin activates microglia and induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons: implications for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox Res.2011;19(1): 63–72. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9140-z. Epub: 2009 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein AI, Garrison SP, Zambetti GP, O’Malley KL. 6-OHDA generated ROS induces DNA damage and p53- and PUMA-dependent cell death. Mol Neurodegener.2011; 6(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-2. Epub: 2011 Jan 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho Y, Son HJ, Kim EM, Choi JH, Kim ST, Ji IJ, Choi DH, Joh TH, Kim YS, Hwang O. Doxycycline is neuroprotective against nigral dopaminergic degeneration by a dual mechanism involving MMP-3. Neurotox Res. 2009;16(4): 361–371. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9078-1. Epub: 2009 Jul 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque S, Wilson B, Gregoria V, Thorpe LB, Dallas S, Polikov VS, Hong JS, Block ML.Reactive microgliosis: extracellular micro-calpain and microglia-mediateddopaminergic neurotoxicity. Brain. 2010; 133(Pt 3): 808–821. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp333. Epub: 2010 Jan 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, Itagaki S, Boyes BE, and McGeer EG Reactive microglia are positive for HLA-DR in the substantianigra of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease brains. Neurology.1988; 38(8) :1285–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, McGeer PL, McGeer EG Lewybodies in Parkinson’s disease are recognized by antibodies tocomplement proteins. Acta Neuropathol. 1992; 84(1) :100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaźmierczak A, Adamczyk A, Benigna-Strosznajder J. Author information. The role of extracellular α-synuclein in molecular mechanisms of cell death. Postepy Hig Med Dosw. 2013;67:1047–1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang T, Pei Z, Miller DS, Wu X, Block ML, Wilson B, Zhang W, Zhou Y, Hong JS, Zhang J. Aggregated alpha-synuclein activates microglia: a process leading to disease progression in Parkinson’s disease. FASEB J.2005; 19(6): 533–542. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2751com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Dallas S, Zhang D, Guo JP, Pang H, Wilson B,Miller DS, Chen B, Zhang W, McGeer PL, Hong JS, Zhang J. Microglial PHOX and Mac-1 are essential to the enhanced dopaminergic neurodegeneration elicited by A30P and A53T mutant alpha-synuclein. Glia.2007;55(11):1178–1188. doi: 10.1002/glia.20532. Epub: 2007 Jun 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Phillips K, Wielgus AR, Liu J, Albertini A, Zucca FA, Faust R, Qian SY, Miller DS, Chignell CF, Wilson B, Jackson-Lewis V, Przedborski S, Joset D,Loike J, Hong JS, Sulzer D, Zecca L.Neuromelanin activates microglia and induces degeneration of dopaminergic neurons: implications for progression of Parkinson’s disease. Neurotox Res. 2011; 19(1): 63–72. doi: 10.1007/s12640-009-9140-z. Epub 2009 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Jiang JW, Wilson B, Du L, Yang SN, Wang JY, Wu GC, Cao XD, and Hong JS Systemic infusion of naloxone reduces degeneration of rat substantia nigral dopaminergic neurons induced by intranigral injection of lipopolysaccharide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 2000; 295(1), 125.132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali SF, Newport GD, Holson RR, Slikker W Jr, Bowyer JF. Low environmental temperatures or pharmacologic agents that produce hypothermia decrease methamphetamine neurotoxicity in mice. Brain Res. 1994; 658(1–2), 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infanger DW, Sharma RV, Davisson RL. NADPH oxidases of the brain: distribution, regulation, and function. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006; 8(9–10):1583–1596. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Wu X, Block ML, Liu Y, Breese GR, Hong JS,Knapp DJ, Crews FT.Systemic LPS causes chronic neuroinflammation and progressive neurodegeneration. Glia.2007; 55(5): 453–462. doi: 10.1002/glia.20467. Epub 2007 Jan 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGeer PL, McGeer EG. Glial reactions in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008; 23(4):474–483. doi: 10.1002/mds.21751. Epub: 2007 Nov 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouchi Y, Yagi S, Yokokura M, Sakamoto M. Neuroinflammation in the living brain of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism .Relat Disord 2009; Suppl 3: S200–204. doi: 10.1016/S1353-8020(09)70814-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block ML. NADPH oxidase as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Neurosci. 2008; 9 Suppl 2: S8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S2-S8. Epub 2008 Dec 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tammariello SP, Quinn MT, Estus S. NADPH oxidase contributes directly to oxidative stress and apoptosis in nerve growth factor-deprived sympathetic neurons. J Neurosci.2000; 20(1): RC53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Liu Y, Wang T, Wei SJ, Block ML, Wilson B et al. NADPH oxidase mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced neurotoxicity and proinflammatory gene expression in activated microglia. J Biol Chem.2004; 279(2): 1415–1421. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307657200. Epub 2003 Oct 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorce S, Krause KH. NOX enzymes in the central nervous system: from signaling to disease. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009; 11(10): 2481–2504. doi: 10.1089/ARS.2009.2578. Epub 2009 Aug 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozikowski AP, Nowak I, Petukhov PA, Etcheberrigaray R, Mohamed A, Tan M, Lewin N, Hennings H, Pearce LL, Blumberg PM. New amide-bearing benzolactam-based protein kinase C modulators induce enhanced secretion of the amyloid precursor protein metabolite sAPPalpha.J Med Chem. 2003; 30;46(3):364–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RL, James-Kracke M, Sun GY, Sun AY. Oxidative and inflammatory pathways in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem Res.2009; 34(1): 55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9656-2. Epub 2008 Mar 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Xu B, Bhattacharjee A, Oldfield CM, Wientjes FB, Feldman GM,Cathcart MK. Protein kinase Cdelta regulates p67phox phosphorylation in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2005; 77(3): 414–420. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0504284. Epub 2004 Dec 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey EA, Xu B, Bhattacharjee A, Oldfield CM, Zhao X, Li Q, Subbulakshmi V, Feldman GM, Wientjes FB, Cathcart MK.Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J Immunol. 2004; 173(9): 5730–5738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Min KJ, Pyo HK, Yang MS, Ji KA, Jou I, Joe EH. Gangliosides activate microglia via protein kinase C and NADPH oxidase. Glia.2004; 48(3): 197–206. doi: 10.1002/glia.20069. Epub 2004 Jun 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy LO, Blenis J. MAPK signal specificity: the right place at the right time. Trends Biochem Sci. 2006; 31(5): 268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.03.009. Epub 2006 Apr 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell L Mechanisms of MAPK signalling specificity. BiochemSoc Trans. 2006; 34(Pt5): 837–841. doi: 10.1042/BST0340837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flohe L, Brigelius-Flohe R, Saliou C, Traber MG, Packer L. Redox regulation of NF-kappa B activation. Free RadicBiol Med. 1997; 22(6): 1115–1126. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(96)00501-1. Epub 1998 Aug 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Yang J, Yang Z, Chen P, Fraser A, Zhang W, Pang H, Gao X, Wilson B, Hong JS, Block ML.Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) 38 and PACAP4–6 are neuroprotective through inhibition of NADPH oxidase: potent regulators of microglia-mediated oxidative stress. J Pharmacol Exp Ther.2006; 319(2): 595–603. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.102236. Epub 2006 Aug 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.