Abstract

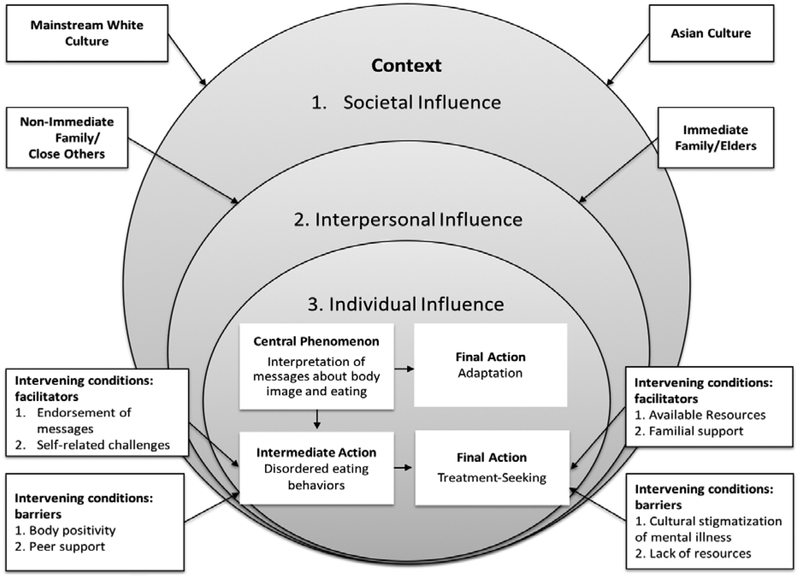

The purpose of the current study was to examine the relationships between body image, eating disorders, and treatment-seeking motivations among Asian American women in emerging adulthood (ages 18–24). Twenty-six Asian American women participated in qualitative focus groups of 4 to 6 individuals each from December 2015 to February 2016. Constructivist grounded theory was used to analyze focus group data. The resulting theoretical model, the “Asian American Body Image Evolutionary Model,” maintains that a central phenomenon of perceptions and interpretation of messages about body image and eating, is rooted in three influencing factors: (1) Societal influence of mainstream White culture and Asian culture; (2) interpersonal influences of immediate family and close others; and (3) individual influence. An individual’s perceptions and subsequent interpretation of messages may lead to disordered eating and decisions around treatment-seeking. The model developed can be utilized by practitioners or clinicians to help obtain a better understanding of the societal, interpersonal, and intrapersonal forces that may shape conceptualizations about body image and eating behaviors among Asian American women. In addition, findings from this study can be incorporated into prevention programs and interventions that focus on mental health among this population.

Keywords: Asian American, body image, eating disorders, qualitative, focus groups

Body image problems have been highly documented across racial and ethnic groups (Bucchianeri et al., 2016; Blostein, Assari, & Caldwell, 2017; Herbozo, Stevens, Moldovan, & Morrell, 2017). These issues become especially prevalent during emerging adulthood (i.e., 18 to 24) when a large percentage of women attend college or university (Rowling, 2006). Asian American women in emerging adulthood are at risk of suffering from body image problems. Across several studies, Asian American women maintain levels of body dissatisfaction at rates equal to or higher than representative samples of other racial and ethnic groups (Frederick, Forbes, Grigorian, & Jarcho, 2007; Frederick, Kelly, Latner, Sandhu, & Tsong, 2016; Stark-Wroblewski, Yanico, & Lupe, 2005). Given these findings, the current study sought to determine Asian American women’s perspectives on both body image and eating disorders using a grounded theoretical framework. Qualitative analyses of the data can be used to inform future research on the onset of eating disorders among this group.

Disordered Eating Behaviors

Historically, White females were considered the population with the highest prevalence of eating disorders (Gordon, Brattole, Wingate, & Joiner Jr., 2006; Wonderlich, Joiner, Keel, Williamson, & Crosby, 2007). However, there is some evidence that eating pathology is a significant problem among racial and ethnic minorities, including Asian American women. For instance, in a meta-analysis conducted across U.S. and non-U.S. samples by Wildes, Emery, and Simons (2001), women of Asian ancestry exhibited higher levels of eating pathology for behaviors such as weight and dieting concerns, dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, smaller ideal body, and lower reported weight than White women. Other studies indicate that Asian American women manifest eating disorders such as anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder at rates equivalent to or higher than White women (Franko, Becker, Thomas, & Herzog, 2007; Marques et al., 2011). However, research in this population is limited, and there remains a dearth of research on the prevalence rates of eating disorders.

Diagnosis and treatment.

One contributing factor to why eating disorders are not widely examined among Asian American women is a lack of conceptual understanding of what constitutes disordered eating behaviors. Indeed, several diagnostic tools for eating disorders were developed primarily using European American female samples (Fairburn & Beglin, 1994; Garner & Garfinkel, 1979; Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983; Kelly, Cotter, Lydecker, & Mazzeo, 2017) and eating disorder diagnostic criteria according to the DSM-V do not take intercultural differences into account (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A lack of culturally-appropriate diagnostic tools may indicate that symptoms remain hidden from the view of clinicians and practitioners, resulting in possible underdiagnoses of these and other disorders. In fact, some research has found that Asian Americans were less likely than Europeans Americans to be referred for evaluation for not only eating disorders (Franko et al., 2007), but also major depressive disorder and postpartum depression (Goyal, Wang, Shen, Wong, & Palaniappan, 2012; Shao, Richie, & Bailey, 2016).

Aside from problems in diagnoses, Asian women have low rates of treatment-seeking for eating disorders overall (Abbas et al., 2010; Lee-Winn, Mendelson, & Mojtabai, 2014), as well as low rates of treatment-seeking across all psychiatric conditions (Meyer, Zane, Cho, & Takeuchi, 2009). The majority of data around treatment-seeking among Asian women have been analyzed in the aggregate, thus examining treatment-seeking among racial and ethnic minorities in general. However, some literature has examined barriers to and facilitators of treatment-seeking among unique populations. Culture, in particular, has been found to be an especially important determinant of help-seeking behaviors.

Culture and Eating Disorders

A growing body of literature has examined the role of culture as a factor in the development of eating disorders and treatment-seeking among racial and ethnic minority groups. For instance, the work of Cachelin, Gil-Rivas, and Vela (2014) has found that acculturation to U.S. society was associated with greater motivation to seek treatment for eating disorders among Latinas. Conversely, Latinas cited barriers such as shame, stigma, lack of financial resources, and lack of confidence in health care providers (Cachelin & Striegel-Moore, 2006). Literature among Asian Americans is sparser but has indicated that cultural stressors including acculturative stress and perceived racial discrimination may motivate Asian American women to engage in disordered eating behaviors.

Acculturative stress.

One factor that may play an important role in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology among Asian Americans is acculturative stress (Claudat, White, & Warren, 2016; Kwan, Gordon, & Minnich, 2018). Acculturative stress has been described as physiological and psychological distress that results from an individual’s attempt to maintain a balance between a dominant culture and their native culture in a certain life domain (Berry, Kim, Minde, & Mok, 1987; Berry, 1998). For instance, among Asian American women who are not native U.S. citizens, eating disorders may be a coping mechanism in response to rapid cultural changes and conflicting messages about body image from the dominant U.S. culture and an individual’s native, Asian culture (Claudat et al., 2016).

Asian American women who are especially vulnerable to endorsing cultural expectations of beauty might be motivated to engage in disordered eating behaviors when their perceived appearance does not match up to societal messages about appearance (Yokoyama, 2007). For instance, in a study conducted by Kroon Van Diest and colleagues (2014), acculturative stress was significantly associated with bulimic symptomatology (e.g., binge and purging behaviors) among Asian American women. In another study by Guan, Lee, and Cole (2012), Asian American women who identified more highly with Asian culture held stronger belief ideals about having a thin appearance. However, when exposed to Asian cultural cues (i.e., images yielded from internet searches including the terms “Asian culture”), they held thicker ideals.

Intergenerational cultural conflict.

One factor related to acculturative stress is intergenerational cultural conflict, or acculturation-based conflict. This type of disharmony arises when core values between familial generations diverge as younger generations endorse more mainstream American values while the older generations maintain traditional ideals (Lui, 2015). Some research among minority populations has assessed the relationships between acculturation, generation levels, and eating disorders. For instance, Chamorro and Flores-Ortiz (2000) examined the relationship between acculturation and disordered eating among different generations of Mexican American women. Study findings precluded that second-generation Mexican Americans (i.e., women born in the United States to parents with international origins) had both the highest acculturation scores and disordered eating scores across a sample of multigenerational women.

Additionally, the Chamorro et al. study may indicate that, among second-generation women, the impact of intergenerational cultural conflict may heighten other mental health issues and maladaptive coping behaviors. For instance, some studies have found that second-generation status among Asian Americans is associated with poorer mental health outcomes (Lee et al., 2017; Lui, 2015; Ying & Han, 2007). Among women specifically, intergenerational differences in appearance ideals may also induce culture-specific stressors that promote eating pathology. For instance, interpersonal shame, or Asian and Asian Americans’ culturally salient experiences of shame, is manifested by perceptions that others have negatively evaluated the individual (i.e., external shame) or perceptions that the individual has brought shame to the family (i.e., family shame) (Wong, Kim, Nguyen, Cheng, & Saw, 2014). The construct of interpersonal shame as it relates to eating pathology may indicate that the perceptions of close others’ values is integral in the development of attitudes and behaviors around appearance and eating.

Perceived racial discrimination and objectification.

Another potentially related influence to acculturative stress is perceived racial discrimination. Specifically, some research has examined the path by which racial discrimination acts as an impetus for the development of eating disorders by affecting an individual’s self-perceptions (Cheng, 2014; Velez, Campos, & Moradi, 2015). Theorists have posited that this pathway occurs when instances of racial discrimination transmit negative or stereotypical messages about appearance. These messages then lead to self-objectification and disordered eating among targets of discrimination (Cheng, 2014; Moradi, 2010, 2011, & 2013; Velez, Campos, & Moradi, 2015). Asian American women, in particular, are subject to racial stereotypes such as exoticism and a marked difference in facial appearance from White women (Hall, 1995; Kawamura, 2002; Sue, Buccieri, Lin, Nadal, & Torino, 2007; Yokoyama, 2007). Theoretically, Asian American women that observe these stereotypes may then internalize them (Cummins & Lehman, 2007), thus leading them to engage in eating disorders (Cheng, 2014; Cheng, Tran, Miyake, & Kim, 2017).

Theoretical Framework

The current study’s theoretical framework was largely influenced by extant models based on bioecological systems theories (e.g., Process-Person-Context-Time Model, PPCT; Bronfenbrenner & Ceci, 1994) as well as previous literature examining cultural influences on eating symptomatology (e.g., Cheng, 2014). In Bronfenbrenner and Ceci’s (1994) PPCT, the interactions of interpersonal relationships, intrapersonal characteristics, environmental contexts, and time shape the attitudes and behaviors of an individual. Following the collection and analysis of data, the authors discussed how themes from qualitative interviews could be conceptualized in a way such that each component of the PPCT could be represented in a theoretical model. As authors continued to develop the model, a prototype resembling PPCT emerged. This approach accounted for the interwoven influences of culture, family, and innate processes in the development of attitudes among Asian American women across time.

Purpose

The putative relationships between body image, disordered eating behaviors, and cultural perceptions of these constructs may be integral in the development of health-related beliefs among Asian American women. The purpose of this study was to use grounded theory to explain the process by which Asian American women in emerging adulthood perceive and interpret messages about body image and eating disorders and whether these interpretations encourage treatment-seeking behaviors. The model developed can be utilized by practitioners, helping them to better understand the forces that shape conceptualizations about body image and eating behaviors among Asian American women. In addition, findings from this study can be incorporated into prevention programs and interventions aimed at reducing unhealthy weight and appearance beliefs among Asian American women.

Methods

Grounded Theory

Compared with other qualitative methodologies, grounded theory is distinguished by its use of constant comparative analysis (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). In constant comparison, the processes of data collection and data analysis occur simultaneously to allow for later stages of data collection to be informed by analytic outcomes from the initial sets of data. Additionally, the specific framework of social constructivist grounded theory from the perspective of Charmaz (2006) was employed. Charmaz’s (2005, 2006) methodology aims primarily to describe how individuals construct their social realities through both an individual and a collective lens. In order for a representative theory to emerge, the current study used both rigorous, yet flexible methods in line with social constructivist grounded theory recommendations.

Participants

Participants were recruited primarily via purposeful sampling, which involves “selecting information-rich cases strategically and purposefully” (Patton, 2002, p. 243). A previous study by the authors established that Asian American women in emerging adulthood, specifically those in a college environment, have distinctively high levels of body image problems and body dissatisfaction (Javier & Belgrave, 2015). Thus, participants were recruited from a diverse college setting via the undergraduate psychology research platform.

Women were pre-screened using a variety of inclusion criteria including: 1) Identify as Asian American; 2) Be between the ages of 18 and 30; and 3) Report having some body image problems (i.e., “Do you report any body image concerns?”). Criteria 1 and 2 were generalizable enough to yield a diverse group of Asian women, ranging in age. The current study was not focused specifically on women who had clinically-significant levels of eating disorders and criterion 3 was included in order to yield a sample of women that were at risk for developing eating disorders. This criterion was taken directly from The Body Project, an evidence-based eating disorder prevention program aimed at reducing risk of eating pathology among women with body image problems (Becker, Bull, Schaumberg, Cauble, & Franco, 2008). If women met all three criteria, they were contacted by the first author and scheduled for a group. Overall, 30 participants were scheduled to participate, but 4 individuals did not complete the study. The final sample included 26 Asian American women ranging in age from 18 to 24 (M = 19.25, SD = 0.78). Diverse Asian subgroups were represented throughout this sample as well (Korean: N = 6; Chinese: N = 1; Vietnamese: N = 5; Indian N = 6; Filipino: N = 3; Pakistani: N = 3; Nepali: N = 1; Half-Vietnamese, Half-Lao: N = 1).

Data Collection Procedures

This study was first approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board as a part of a larger study examining the effect of a culturally tailored intervention on treatment-seeking motivations among Asian and African American women. Data were collected in the form of audio-recorded transcriptions of focus group discussions held in-person at a private and secure location on the university’s campus. Focus groups ranged in size from 4 to 6 participants each, which was acceptable according to sample size benchmarks for focus group discussions (Prince & Davies, 2001) (N = 26). The first author was the facilitator for the focus groups, and a trained research assistant was present at every session to take detailed notes about observed group processes. Focus groups lasted between 30 to 35 minutes each and were held from December 2015 to February 2016.

Upon arrival, participants completed informed consent and confidentiality and anonymity were discussed and questions were answered. To assist with ease of transcription and analyses, women were asked to choose a pseudonym and identify themselves by their pseudonyms prior to answering any questions. At the conclusion of the session, participants were asked once again if they had any questions. After answers were provided, they were given course credit and thanked for their time and contributions.

Focus Group Questions

A semi-structured list of interview questions was developed, reviewed, and refined by reviewers (i.e., psychology faculty) with interests and background in body image of ethnic minority women. The focus group questions were semi-structured to allow the facilitator to have the flexibility to ask a follow-up question or clarify if needed (Braun & Clarke, 2006). In line with social constructivist grounded theory, the list and wording of the questions were refined and clarified as emerging analyses demonstrated a need for alteration in order to accurately reflect participant responses. The following set of questions constituted the final set of questions used:

What is body image to you?

How would you define “disordered eating behaviors”?

Using your own, or others’ experiences, how do you think body image and/or body dissatisfaction develop among ethnic minority women?

What about culture would cause women to have body dissatisfaction?

What are the consequences of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among ethnic minority women?

What are the barriers to treatment-seeking for eating disorders among ethnic minority women?

What may prevent ethnic minority women from staying in eating disorder treatment programs?

There were no changes to the list of questions as data collection process continued but wording slightly changed in some cases. For instance, in questions 3, 5, 6, and 7, the facilitator began to use the term “Asian American women” in place of “ethnic minority women.” This change was made as it became apparent that participants correlated the term “ethnic minority” with their experiences as Asian American women. In addition, question 4 was altered slightly to clarify what was meant by the term “culture.” In most cases, the facilitator had to clarify that “culture” could indicate native, Asian culture or the dominant, U.S. culture.

Data Analytic Procedure

Data collection occurred until saturation was reached, at 6 focus groups (N = 26). During the course of data collection, focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed by two trained research assistants according to a preliminary set of guidelines determined by the first author. These transcriptions were then verified by the first author. Data were then uploaded into ATLAS.ti version 6.0 (Dowling, 2008) and a constant comparison analytic process was undertaken. ATLAS.ti was used to both code and prepare memos of the data (i.e., notes that comment on emerging categories of pieces of text). Charmaz has stated that memo-writing is an integral part of the data analytic process and allows for a researcher to link “analytic interpretation with empirical reality” (Charmaz, 2000, p. 517).

The major characteristics of social constructivist grounded theory involves the iterative processes of initial coding, focused coding, and theoretical coding (Charmaz, 2006). As recommended with grounded theory research, the process of refining codes and themes was iterative, and constant comparison occurred at each review of the data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). During the initial coding process, transcripts were thoroughly reviewed and memo writing was used to comment on emergent categories. Then, a list of preliminary codes was developed. Quotations which encapsulated multiple preliminary codes were sorted accordingly, and then were further broken down during subsequent coding stages. During the focused coding stage, codes developed during the initial coding state were narrowed down to those that occurred most frequently and were considered most integral to the emergent theory. Transcripts were then reviewed and individual quotes were placed under these narrowed codes. Finally, during the theoretical coding stage, relationships between codes and categories were delineated. A grounded theoretical model emerged from these interrelationships, from which a group process theory could be derived (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Asian American Body Image Evolutionary Model (AABIEM)

In order to improve methodological rigor, several steps were used. First, the primary researcher reviewed on-going findings with trained research assistants in several on going meetings in order to reach consensus and an appropriate level of inter-rater reliability These individuals were helpful in bias-checking and ensuring that the emergent codes fit in with their perceptions of what the participants were stating around the focus group questions. Second, detailed focus group notes taken by trained research assistants were analyzed and used to triangulate the emergent themes, thus ensuring greater reliability and validity of the data. Third, research assistants trained in qualitative methodology independently coded 30% of the manuscripts. These coded manuscripts were checked against those coded by the first author, and yielded kappa values ranging from K = 0.74 to K = 0.79, indicating a substantial degree of interrater reliability according to established benchmarks (Cohen, 1960; Landis & Koch, 1977). Finally, the on-going process of bracketing was used by the primary researcher throughout both the data collection and data analyses processes (Charmaz, 2000). The first author is an Asian American woman within the target age range and bracketed her personal experiences via setting aside of personal assumptions and continual hermeneutic reflection in the data analytic process. As an example, during the analytic process, the first author had initially coded quotes pertaining to participant’s experiences in the U.S. (i.e., “Mainstream White Culture” in the final model) as “Western Culture.” However, when discussing this code with the second author, she thought about whether the term “Western Culture” was too broad to capture nuances in the data. Specifically, participants mainly referred to White culture when discussing U.S. influence. Subsequently, this code was changed to reflect these nuances in the data.

Results

Figure 1 presents the final model, entitled the “Asian American Body Image Evolutionary Model.” Thirteen prevalent codes were grouped into three major themes of: (1) Societal Influence; (2) Interpersonal Influence; and (3) Individual Influence.

The illustrative discussions among Asian American women provided the framework for the process of developing attitudes and behaviors about body image and eating behaviors in this population. Overall, the three main thematic categories that emerged from analysis were that of perceptions of societal, interpersonal, and individual influence in determining an individual’s attitudes towards and interpretation of body image and eating messages. Interestingly enough, these influences were interwoven throughout the discussion and affected almost every subsequent theme gleaned from the model. These attitudes and the central phenomenon of interpretation, in turn, led to hypothesized actionable behaviors including: 1) engaging in disordered eating behaviors; or 3) adaptation to one’s current body image. Finally, the actions gleaned from these focus groups were found to be directly linked to participants’ feelings about treatment seeking. It should be noted that there may exist reciprocal relationships between attitudes, interpretations (or perceptions), and consequences. These relationships are reflected in Figure 1.

Definitions of Disordered Eating

At the start of focus groups, participants were asked to express how they conceptualized eating disorders. Table 1 indicates the terms used by women to describe eating disorders and the number of women mentioning these terms across focus groups. These responses indicate variation across women, with the most common responses including perceiving eating disorders to be negative perceptions of one’s body, bingeing, and restriction of food intake.

Table 1.

Definitions of disordered eating (N = 33 responses across 26 participants)

| Terms Used | Number of Responses | % of Total Response |

|---|---|---|

| Negative perceptions of one’s body | 6 | 9.09% |

| Bingeing | 5 | 15.15% |

| Restricting food intake | 5 | 15.15% |

| Unhealthy behaviors | 3 | 18.18% |

| Negative perceptions of eating | 3 | 9.09% |

| Control | 2 | 6.06% |

| Guilt about eating habits | 2 | 6.06% |

| Anorexia | 2 | 6.06% |

| Bulimia | 2 | 6.06% |

| Mental disorder | 2 | 6.06% |

| Addiction | 1 | 3.03% |

Dichotomy of American VS. Asian Cultures

The contextual theme of societal influence provided the systematic context within which thoughts and behaviors about body image and eating emerged among Asian American women. One-hundred and thirty-one quotes were coded for “Asian Culture” and “American Culture” across the six focus groups. Two societal influences in particular were discussed by the majority of participants: 1) mainstream White or U.S. culture (50 quotes); and 2) native Asian culture (81 quotes). Throughout focus group discussions, the dichotomy of the U.S. culture versus Asian culture became very apparent. For instance, some participants remarked on the contradictory nature of ideal appearance in U.S. culture versus Asian culture. Jessica, a Vietnamese woman (20), commented,

And I think it’s sort of like what I notice in my culture is that the Vietnamese body image … and the U.S. body ideal body image is, like, they sorta contradict each other … We prefer someone who works out and like tanner but in … Vietnam, they it’s more like you should have a slim body but don’t work out and things like that. And then you should be pale. It’s sorta, sorta hard to live here when it’s like two things all at once.

Grace, a Korean woman (18), discussed that relatives or family members in particular may experience this discrepancy especially if they are recent transplants or visitors to the United States:

My cousins that came to America recently, they’re uncomfortable here because they’re more related to Korean culture, and then being kinda forced to American culture is different for them. So their idea of body image, about how they should look, how they should eat and stuff like that, is a lot different I guess…

The negative impact of Asian culture at the societal level on positive body image was also present throughout the discussions. Yonda, a Vietnamese-Laotian woman (20), discussed how there is one standard of beauty in Asia that is different from the U.S. ideal of beauty when she stated, “But then in the Asia especially, there’s like one set standard of what beauty is supposed to be and I guess if you don’t kind of fit that, then you’re not considered actually pretty or good enough, I guess.”

Christine, a Korean woman (19), discussed the specific influence of Asian media in shaping attitudes towards body image and eating behaviors:

I also watch a lot of like Korean shows and stuff, and all the like Korean stars are always like-they’re all like stick skinny and stuff and I feel like a lot of that plays into, you know, oh they look so good I wish I could look like them, maybe I should diet like them.

Taken collectively, participants actively discussed that there exist clear dichotomies of beauty in the United States versus their native Asian cultures. There were specific nuances for individual Asian cultures. For instance, Christine discussed the importance of the media and of Korean stars in determining beauty standards among Korean women. However, there appeared to be a general sense that, among Asian subgroups, the ideal that women should be small or “skinny” is prevalent, but this ideal is different from messages about appearance that permeate in U.S. culture.

Interpersonal Influence

There were 2 subthemes that emerged under the major theme of interpersonal influence: immediate family or elders, and non-immediate family or close others.

Immediate family/elders.

Seventy-four quotes were coded under “Immediate Family/Elders” across the 6 focus groups. Focus group participants often emphasized the influence of immediate family, especially in the form of elders (e.g. mother, father, grandparents), on body image and eating behaviors. Grace, an Indian woman (19), discussed how her parents and grandparents had expectations that she should be a certain weight or else she might suffer the consequences of being unmarried:

No matter how much I eat I just stay one weight. And um, this is like a problem to like, my grandparents and stuff like that, because they’ll be like, “Oh, if you’re not a healthier weight, like, you’re not going to get married one day.”

This sentiment was shared by another young Pakistani woman, Kelly (18), who reported that her family members stated that a curvier body shape was important for marriage and partnership. This theme may be especially salient among South Asian American women and families, as the mention of marriage in relation to appearance was not discussed among other subgroups.

Immediate maternal family members’ influences seem to have particular salience across Asian subgroups. Several focus group members discussed the opinions of their mothers and grandmothers specifically in shaping attitudes about body image and eating behaviors. For instance, Jess, a Chinese Korean woman (18), stated,

In my family, like, especially my mom and grandma, they don’t want to see me get big or gain weight but they’re just like, they don’t want me to starve either, so whenever I come home from college they’ll be like, “Oh, you gained some weight, but what do you want to eat?”

Jess discusses a problem that highlights the conflicting opinions and views of immediate Asian family members in relation to appearance and eating behaviors, i.e. that women in general are expected to appear slim but are often encouraged to eat copiously. In addition, Jess’s statement touches on the dichotomies of U.S. versus Asian cultural expectations about appearance and eating in that she tends to hear these messages while in contact with her family but does not necessarily hear these messages when she is in a college environment.

Another individual, Hannah (20), discussed how her grandmother’s influence extends to her own views of appearance:

My grandma, especially since she’s only lived in Korea her whole life, and our culture is like, you see all the women, or just the way, um, the media advertises women – that they should have pale skin and be like, really skinny. So I think since she grew up with that atmosphere, she brought it along with her to America, so that’s how we’re learned to view ourselves …

In addition to the above statements, several participants also remarked on how negative conversations about body and appearance occurred within the immediate family. For instance, Danni, an Indian woman (18) stated,

But like, pulling myself away from that and like, just seeing our generation, we don’t bash the way our family does. Like, I had a little bit of a body image problem and it’s not like I realized it there, because I thought it was just the norm.

Hannah, a Korean woman (20), remarked,

Based on experience, I was really chubby in middle school and my mom would always make fun of me for that. So um, like, whenever it was dinnertime, I used to eat a lot, but because of those constant nagging, I tried to eat less.

Danni, an Indian woman (18) said, “Like, mine {parents} would be like, we’d be driving to {the grocery store} and she’d go off, and I’m like, Mom! Like, every conversation we’d have a serious conversation and it’d end in a body image thing.”

These statements touch in general on the state of ease that immediate family members have when it comes to remarking about their daughter’s body image and appearance.

Non-immediate family or close others.

The family unit in Asian culture does not just encompass immediate family, but often includes extended family. Indeed, many participants remarked on the input of extended family members including aunts, uncles, and cousins, in influencing body image and eating behaviors. Thirty-three quotes were coded under this category across focus groups. Yonda, a Vietnamese-Laotian woman (20) remarked that the presence of an eating disorder in an individual is not contained within the family but will “spread around their society.” She continued to say, “They talk,” indicating that eating disorders may also be a point of gossip with non-immediate family or close others. Christine, a Vietnamese woman (19), stated,

I’ve always had this problem with my family, we’ve always like had discussions on you know our cousins being like overweight and stuff like that. Like we’d come back from Christmas break or something and all of our aunts and uncles would always be like “Oh, you gained a lot of weight”, “Oh, you should lose weight.”

Christine discusses the idea that in certain Asian subgroups, it may be common for non-immediate, extended family to freely voice their opinions about appearance and eating behaviors. These comments, in turn, may encourage individuals to engage in dietary behaviors in order to avoid these types of comments. This negative perception is seen in use of words and phrases with negative connotations (e.g., “problem,” “jabs,” “made fun of”).

Mindy, another Vietnamese individual (18), expanded on these sentiments. She said,

…when you meet um, other parents, like other aunts or uncles, um, they definitely judge based on what you’re like, how well you fit in that dress, or what you’re wearing, or what you look like compared … to their son or daughter so like, there’s a lot of comparison going on in our cultures.

Jade, a Korean woman (18) stated, “My relatives are a lot more open about, like, criticizing your appearance [inaudible]. Like if they, like, if you put on a little weight, they’ll be like, ‘Oh you put on weight! Eat more! Eat more!’”

An Indian woman named Veronica (19) had a slightly different perception of immediate family versus extended family. She stated,

Honestly in my family, like, my mom has never, or like, my family in general, they’ve never been like, “Oh you’re too skinny or you’re too fat.” … But when you go outside the family and you see your relatives from India, or like, see your relatives that live around here, they will probably say something like, “Oh you’re a little chubby” or “Oh, you’re little.” So I think, I don’t know, I get mixed signals all the time as to what their ideal thing is though.

Veronica indicates that while immediate family members may not engage in appearance-related comments with their daughters, non-immediate family members in the family often feel comfortable enough to do so.

Interpretation of Messages

Based on attitudes developed within interpersonal and societal contexts, women appeared to make a conscious interpretation of whether or not these messages would affect them personally or not. Interpretations of these messages were found to be the central phenomenon in the development of tangible and intangible body-related behaviors and encompassed 89 quotes across 6 focus groups. These interpretations presented themselves mostly in the form of comparisons leading to value statements about appearance. For instance, Lisa, a Nepali woman (18) stated,

I think one other side to that is media too ‘cause um, as Nepali, I have, I have like grown up watching movies and everything, so like, when you see in the movie they’re like all skinny and stuff, you’re like, “Oh, why can’t I be like that?” And then I think it puts pressure on people to be kind of like, like that, because I think that kind of body is idealized in this society.

In some cases, the disjunction of appearance ideals from the conflicting viewpoints of Asian and American cultures at both the systemic and interpersonal levels resulted in a negative overall interpretation of self-appearance. Grace, an Indian woman (19), stated,

I feel like for girls who are Asian and live in the United States there’s already this [problem]- ‘cause I know when I was younger … I lived in Kansas, and … I was a minority and there were so many girls that were White and pretty and skinny, and it’s just like I’m not White, I have to be pretty and skinny.

Disordered Behaviors or Adaptation

Once an individual receives and interprets messages about body image and eating, they develop attitudes concerning these constructs. It then logically follows that they reconcile their behaviors to align with these attitudes. In this sample, resulting behaviors included either engaging in disordered behaviors or adaptation. In the current study, “adaptation” indicated that participants were able to successfully reconcile any negative perceptions of body image and eating behaviors in order to avoid disordered eating. In other words, adaptation can be defined as not engaging in disordered eating behaviors. Facilitators of engaging in disordered behaviors included endorsement of messages about disordered eating and self-related challenges. Barriers to disordered behaviors that ultimately led to adaptation included body positivity and peer support.

Facilitators.

There were two main factors in the promotion, or “facilitation” of disordered eating behaviors among Asian American women in the focus groups: (1) endorsement of messages about disordered eating (31 quotes); and (2) self-related challenges (39 quotes).

Endorsement of messages about eating behaviors were discussed as resulting from listening to and internalizing messages from family members and the media. “Self-related challenges” is the term that is used to describe how participants reported mental health problems and internalized problems that were associated with eating behaviors. Several participants mentioned that lack of self-confidence plays a role in eating disorders. Anxiety was also mentioned a number of times.

In addition, the topic of ‘lack of control’ was discussed by several participants in relation to engaging in the behavior of disordered eating. For instance, Yonda, a Vietnamese-Laotian woman (20), said, “[Disordered eating behaviors are] not being able to control yourself [like] when it comes to eating and then, being too controlling about your eating habits.” Helplessness as a self-related challenge also seemed to be common, and Yonda also stated,

There’s certain things you can’t change. Like no matter how much you try, you can’t make your skin lighter. That’s not something you can physically do, so it’s something that I guess hurts certain people. Um, not personally, but like, other people. And then it’s not like they can do anything about their skin color, so.

Barriers.

Two main barriers, or protective factors, for disordered eating presented in the focus groups and were associated with adaptation: (1) Body positivity (10 quotes); and (2) Peer support (17 quotes).

Several participants discussed how the United States was generally more “body positive” than their native Asian cultures in that a greater variety of body types were seen as attractive in the U.S. Sophia, a Pakistani woman (18), stated, “I feel like here, everybody’s taught to be, like, everyone’s told that you’re a special butterfly and you’re like, however you look like, perfect just the way you are.”

The general theme of diversity in beauty in the United States was seen throughout focus groups, as was discussed in the theme of dichotomy of U.S. versus Asian culture. In Sophia’s statement, she touches on the American sentiment of uniqueness as opposed to collectivism. This might be an indicator of endorsement of an individualistic versus a collectivist culture. Although individualism and collectivism have been discussed in terms of group behaviors on a general level, it also appears to extend specifically to women’s body image as well.

Another participant, Hannah, age 20, stated that “[In America], people are protesting for women like, women should not care about how they look. They should embrace how they look.”

Messages about diversity in beauty seemed to extend also to peer communication and was mostly seen via statements about peer support. Several participants noted the dichotomy between negative family interactions about body image and positive peer interactions about body image. For instance, Danni, an Indian woman (18), remarked on the generational differences between older individuals and younger women, stating,

I had a little bit of a body image problem and it’s not like I realized it there {home} because I thought it was just the norm. But like, pulling myself away, like the first semester I was here {college}, I was like, whoa! This is weird, everybody’s like, ‘You look fine!’”

She goes on to remark about eating behaviors being different among peers versus family, describing that, “When I’d go out with my family, I wouldn’t eat dessert. But when I went out with my friends, I’d eat like a whole dessert by myself.”

Christine, a Vietnamese woman (19), described that, “Luckily for me, like, I came to college and I had the good friends that gave me confidence in my own body image, and I grew to love how I looked.”

Overall, the concepts of body positivity and peer support seem to act as a barrier to disordered eating behaviors, and specifically restrictive behaviors. These concepts also appear to boost individual confidence in body image.

Treatment-Seeking

Two subthemes were categorized under this theme, including facilitators of treatment (e.g., the presence of available resources and familial support) and barriers to treatment-seeking.

Facilitators.

Individuals discussed facilitators of treatment-seeking for disordered eating in the form of available resources (9 quotations) and familial support (17 quotations).

Available resources.

Individuals discussed the presence of resources as a vital factor in an individual’s decision to seek treatment for disordered eating behaviors. For instance, Christine, a Vietnamese individual (19) described that having a “nutritionist or to follow or to have a dietary plan” would be a good preventive measure for eating disorders. Other individuals, such as Lisa, a Nepali woman (18) described that having available finances for these types of treatments is key. She stated, “Maybe I’m just wasting my money to go to these therapies and stuff, so I think that’s one thing that might, she just might not go and stop going to therapy sessions.” Mary, a Korean individual (19), also discussed that having financial resources is important: “Uh another reason I believe is like, her financing, if she’s able to pay for all the therapy because I think it’s expensive.” Chloe, a Korean individual (18), talked about the importance of resources in the form of family members with a medical background. She stated,

I did develop an eating disorder in seventh grade, and I would have to go to different therapies and stuff cause my family is pretty, my like close family is pretty uh, White washed so they can like, they really believe in therapy and stuff. And my dad’s also like a doctor too, so he like, got me a nutritionist and everything …

Time was another resource mentioned by participants in the context that individuals had to have time to attend these therapies and treatments in order to be motivated to go. For instance, Natasha, an Indian woman (19), stated that, “It feels like it’s not worth it, like the time you’re putting in is not worth it.”

Familial support.

Participants also talked about the importance of familial support in their decision to seek treatment for eating disorders. Hannah, a Korean woman (20) stated, “If a woman like, really cares about how society thinks of her, then if her family is discouraging her to like, get help, then she’ll probably stop getting the treatment if her family’s perspective matters a lot.” Sophia, a Pakistani woman (18), contrasted familial support within an Asian family to that of a White family:

If you were just like a Caucasian and you had an issue, I feel like your family would support you way more than an Asian family would support you ‘cause they’d be like, “You’re perfect, nothing’s wrong with you.”

Another individual identifying as Grace (Korean woman, 18), tied in the concept of familial support with ethnic identity. She stated,

We have a higher standard for our families, for ourselves, for our race, like we have so much pride in our race. … when we are put into these programs where we know it’s going to be good for us, a little bit of us are worried about judgment for our families, for ourselves, etc.

Barriers.

The biggest barrier to treatment seeking apart from lack of available resources (coded as “Available Resources” in the Facilitation section, seen above) was cultural stigmatization of mental illness. This concept presented in 37 quotations across groups.

For the purposes of this section, “stigmatization” is defined in both a negative and neutral sense. For instance, several of the quotations discuss a lack of acknowledgement that mental illness exists, which can be seen as neutral. Other individuals describe mental illness using a negative perspective or mention that members of their cultural and ethnic groups see mental illness in a negative way.

Sophia, a Pakistani individual (18), described a lack of acknowledgment that mental illness exists when she stated,

I personally have a lot of Asian friends that tell me that if they ever went through depression, their parents would be like, ‘No, nothing’s wrong with you. You’re fine.’ But, if you were a Caucasian, they’d be like, no we need to trigger this out, let’s help you.

In terms of viewing mental illness negatively, some women reported that older Asian generations might acknowledge that something is wrong with their daughter, but do not attribute the problem to mental health. For instance, Kelly, age 18, expanded on this point in regards to a Pakistani friend:

One of my friends actually has really bad anxiety and she doesn’t eat, like she wakes up with night terrors and everything and like, her whole family, even her sisters who are born and raised here, like they just don’t think she has any problems, even though she wakes up screaming and she wasn’t doing well in school and everything, and um they were all just like, “No, um, you should just pray more or you just need to focus.”

Overall, individuals expressed the sentiment that family members were the primary individuals who did not believe in mental illness, or that mental illness could be treated via methods other than psychotherapy or via psychological counseling.

Discussion

The influx of literature around the phenomena of eating disorders among Asian American women calls attention to the need for research on determinants of these disorders. The current qualitative study formed a grounded theoretical model, the “Asian American Body Image Evolutionary Model (AABIEM),” which can be used as a starting point for intervention in this group. The AABIEM is based on the premise that society and family affect an individual’s attitudes about body image and eating behaviors, which in turn leads to the central phenomenon of interpreting these messages. From this point, an individual may either choose to reject body negative perceptions and disordered eating behaviors or accept these expectations. The decision to reject body negativity and disordered eating is called “adaptation” within this model.

The first major influence on the evolution of attitudes towards body image and eating was culture. More specifically, there appears to be a clash of ideals from mainstream U.S. society and one’s native, Asian culture, that may influence attitudes. Several women spoke of Eurocentric ideals that are promoted within U.S. society (e.g., being thin, tan, and athletic). In contrast, idyllic Asian bodies varied from European ideals, with some women commenting that women in their home countries desire to be small, while others stated that a wider body was more desirable.

Despite variability in stated ideals, the overarching impression of these collective statements was that of conflict. In other words, women portrayed that one societal influence told them certain features were beautiful and desirable, but then another society held an opposing ideal. One potential explanation for how conflicting ideals affect attitudes is through acculturative stress. Previous literature has explored the idea of acculturative stress as integral in the formation of attitudes towards appearance and eating (Claudat et al., 2016; Kwan et al., 2018). In the AABIEM, conflicting cultural ideals both directly and indirectly influence attitudes among women and may be partially explained by acculturative stress. In other words, Asian American females may feel a disconnect between U.S. ideals and their native cultural ideals on the body image and eating behaviors. The direct influence occurs when the societal ideals shape internal attitudes and perceptions of beauty. Societal influences indirectly affect these attitudes through the proxy mediums of interpersonal relationships. For Asian American women, interpersonal influences manifest in the form of family members and non-immediate family members, or close others, whose values regarding beauty and eating behaviors may contrast with that of the individual. These interpersonal influences further may lead to the internalization of ideals within the individual and shape their interpretations of body image and eating.

In general, the influencing factors of society, family and non-family members seem to be inevitable to individuals at this age. Thus, for Asian American women in emerging adulthood, it seems as though the critical point of intervention to prevent future disordered eating behaviors is at the intrapersonal level. The family unit was seen as a major driving factor in the development of beauty ideals and eating behaviors among Asian American women. It seems as though family members, and especially elders, held onto beauty ideals from their native cultures, as was seen across ethnic subgroups. Women spoke often of comments that were made by elders such as grandparents and parents of how women in their native countries look starkly different from Asian women in the United States. Individuals seemed to take comments from direct family members to heart the most, although indirect family members and close others also seemed to have an effect on the development of attitudes around body image and eating.

Several women compared and contrasted the body positive views of their peer groups with their more critical native cultures and/or families. Peers appeared to be an integral factor in the decision of women to accept notions of body negativity and engage in alternate solutions or behaviors. It makes sense, then, that the most widely accepted evidence-based prevention intervention among women is conducted among peer groups (Becker et al., 2008). However, when one considers individuals who have already accepted body negative perceptions and may be more likely to engage in disordered eating behaviors, a different intervention point needs to be considered. This prevention point is for individuals who do not “adapt” to body positive messages and peer support and thus, may be at higher risk for developing these behaviors. Within the scope of this grounded theoretical model, Asian American women may largely fit within this category. What makes these individuals different from predominantly White individuals is that they seem to be negotiating ideals from their native Asian cultures, and ideals from a predominantly Eurocentric, or White society. Some women discussed that throughout childhood and/or adolescence, they were exposed to media ideals about beauty within their own native countries. Although these ideals seem to be similar to thin-ideal internalization within White culture, it is unclear whether they can be equated. In addition, some individuals perceived mainstream U.S. culture as, in actuality, being more accepting of diverse body types, which is in contrast with the thin, tan, Eurocentric ideal discussed previously. However, in Asian cultures, the beauty ideals around weight and shape appear to be promoted within the family unit.

The family unit permeated not only body image ideals, but also treatment-seeking motivations among Asian American women. In fact, family seems to be the single most prevalent driving factor in an individual’s decisions to both seek out and remain in treatment for an eating disorder. Family influence did not occur in a vacuum, however, and may extend from cultural stigmatization of mental illness in general. Asian American women in the groups spoke of eating disorders as a small part of a larger issue of stigma against mental illness. One factor to consider is that the majority of study participants were in their 1st and 2nd years of college and may not have felt autonomy to take control of health decisions. Thus, the majority of the women spoke about treatment-seeking as not feasible if family support and other tangible resources did not exist. One potential future study should examine if individuals in older emerging adulthood on an individual health care plan feel more positively towards treatment-seeking.

Limitations

Overall, the study contains some limitations. For instance, there was much diversity within the Asian American groups, with subgroup ethnicities ranging from Indian to Pakistani to Filipino to Chinese, and so on. The number of women that participated in the focus groups was not enough to draw valid conclusions about different subgroups of Asian women. However, the central themes found in the grounded theoretical model seemed to extend across Asian subgroups, so subgroup differences may take a backseat to the larger picture.

A second limitation lies within the age range of the sample. This range was small and included only women in early adulthood. Perceptions of the individuals in this age range may not speak to women experiencing other barriers in middle-to-late adulthood. For instance, several individuals mentioned the presence of health care as a motivating factor for a woman to seek out treatment or stay in treatment for eating disorders. Under the current Affordable Care Act, individuals can stay on their parents’ health care plans until the age of 26 (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 2010). For women who are able to obtain their own health care after this age, the security of having health care, as well as the autonomy to obtain treatment within the guidelines of their own health care plan, might motivate them to seek treatment for mental illness and eating disorders.

A third limitation is that women in this study were mainly college-educated. Racial and ethnic minority women who are students at a predominantly White university in the United States may have a different perspective when it comes to body image and eating behaviors than non-college-educated women in this age group. Future studies should examine Asian American women who are non-college educated in order to examine other potential differences or themes.

Another potential limitation in the current study was the duration of each focus group, which lasted anywhere from 30 to 35 minutes each. Literature suggests that focus groups should last anywhere from 30 minutes to 120 minutes each (Greenbaum, 1998) and groups in the current study were on the shorter end of this criterion. However, the size of the focus groups (i.e., 4 to 6 women each) allowed for more targeted conversation than would occur in larger groups. In addition, each question was thoroughly answered in each focus group and the saturation of themes was met by the time data collection ended.

A fifth in the current study is that reasons for participant dropout were not explored. As the authors previously stated, 30 individuals were scheduled to participate in data collection, but data were only collected from 26 individuals. The psychology research recruitment platform is set up in a way that participants can cancel participation in a study without having to reply directly to the primary investigator. Although the first author contacted participants via e-mail to confirm their scheduled times, none of the 4 non-participants responded with reasons why they could not or did not make it to their scheduled session. Future studies should solicit information on reasons for dropout to determine best practices in recruiting among ethnic minority groups.

A final, potential limitation of the current study is the use of the Body Project criteria as an inclusion criterion. Specifically, individuals were asked whether they experienced body image issues and, if the response was yes, were invited to participate in the focus group. This criterion may not have captured a high-risk group of Asian American women. However, self-reported responses indicated that at least 3 participants had been diagnosed with an eating disorder in the past and thus, the present sample included a range of women who could speak to these phenomena.

Implications

Implications for assessment.

Some prior research (e.g., Smart, Tsong, Mejía, Hayashino, & Braaten, 2011) has explored the influence of acculturative stress and Asian culture on the emergence of eating disorders among Asian American women. The current study provides additional evidence for the importance of incorporating culturally-tailored strategies into treatment for Asian American women with eating disorders or who are at risk for eating disorders. For example, a study by Shea and colleagues (2016) examined culturally-tailored cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) as a potentially effective intervention method to reduce binge eating among Mexican American women. Their findings precluded that the combination of cultural adaptation and family and peer involvement in women’s treatment may be the most effective treatment route for this population. Given findings from the current study of the importance of interpersonal input on the development of eating pathology, an approach similar to that used by Shea and colleagues may be promising among Asian American women. Findings from the current study can also be used to inform common treatment practices by incentivizing clinicians to explore phenomenological experiences of eating disorders in a cultural context and address issues such as acculturative stress in the development of these and other psychological disorders.

Implications for prevention and intervention.

Given findings about peer influences on the development of body image attitudes among women in emerging adulthood, it would be beneficial to include peer teaching and body positivity messages in an evidence-based eating disorder prevention intervention. Peers were found to have a mostly positive impact on beliefs about body image among Asian American women in the current study. They promoted positive messages about body image, contrary to messages from family members. For Asian American women, peer interventions may be especially efficacious in reducing unhealthy weight behaviors.

In addition, family members were found to strongly influence attitudes around body image, eating, and treatment-seeking in this group. Potential future research should examine the efficacy of interventions incorporating family members, especially mothers and grandmothers, in reducing unhealthy body image and eating behaviors among Asian women.

Implications for research.

Findings from the current study can lead to several potential new lines of research. For instance, while eating disorders were examined in a general way in the current study, future studies could tease out factors most important in the onset of specific eating disorders among Asian American women. These studies can then be leveraged to create tailored treatment plans for individuals diagnosed with these disorders. In addition, one area that remains stagnant in the literature is the specific effect of intergenerational cultural conflict on the development of eating and body image attitudes among Asian Americans. Further, this type of study could be enhanced by examining cultural constructs specific to Asian American populations, such as external and familial shame. A final line of research left unexplored is the impact of societal and interpersonal ideals on body image and eating disorders among Asian American men and adolescent boys. Given that marginalized groups of men experience body image and disordered eating issues (e.g., Brennan et al., 2013), this area of research is imperative.

Conclusion

There are a host of unique determinants of body image and eating behaviors among Asian American women. These factors vary by cultural group and may be integral in the motivation for individuals to seek treatment not only for eating disorders, but for other mental illnesses. Thus, while treatment protocols may be generalized across populations for certain conditions including mental health, it may be important to take individual nuances into account in order to develop more culturally competent programs for women.

Public Significance Statement.

Asian American women experience unique stressors that place them at risk for eating disorders. Findings from this study can be used to develop culturally-informed prevention programs and interventions for mental health among Asian American women.

Footnotes

Note: This work was conducted at Virginia Commonwealth University.

References

- Abbas S, Damani S, Malik I, Button E, Aldridge S, & Palmer RL (2010). A comparative study of South Asian and non- Asian referrals to an eating disorders service in Leicester, UK. European Eating Disorders Review, 18, 404–409. doi: 10.1002/erv.1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Bull S, Schaumberg K, Cauble A, & Franco A (2008). Effectiveness of peer-led eating disorders prevention: A replication trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 347–354. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW (1998). Acculturation and health In Kazarian SS & Evans DR (Eds.), Cultural clinical psychology: Theory, research and practice (pp. 39–57). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, & Mok D (1987). Comparative studies of acculturation stress. International Migration Reviews, 21, 491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Blostein F, Assari S, Caldwell CH (2016). Gender and ethnic differences in the association between body image dissatisfaction and binge eating disorder among Blacks. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. [E-pub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U, & Ceci SJ (1994). Nature-nurture reconceptualized in developmental perspective: A bioecological model. Psychological Review, 101(4), 568–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucchianeri MM, Fernandes N, Loth K, Hannan PJ, Eisenberg ME, & Neumark-Sztainer D (2016). Body dissatisfaction: Do associations with disordered eating and psychological well-being differ across race/ethnicity in adolescent girls and boys? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(1), 137–46. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, & Striegel-Moore RH (2006). Help seeking and barriers to treatment seeking in a community sample of Mexican American and European women with eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(2), 154–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Gil-Rivas V, & Vela A (2014). Understanding eating disorders among Latinas. Advances in Eating Disorders: Theory, Research and Practice, 2(2), 204–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro R, & Flores-Ortiz Y (2000). Acculturation and disordered eating patterns among Mexican American women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 28, 125–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2000). Grounded theory: Objectivist and constructivist methods In Denzin NK & Lincoln YE (Eds). Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2005). Grounded theory in the 21st century: A qualitative method for advancing social justice research In Denzin NK & Lincoln YE (Eds.) Handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 507–535). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng H (2014). Disordered eating among Asian/Asian American women: Racial and cultural factors as correlates. The Counseling Psychologist, 42, 821–851. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng HL, Tran AGTT, Miyake ER, & Kim HY (2017). Disordered eating among Asian American college women: A racially expanded model of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(2), 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claudat K, White EK, & Warren CS (2016). Acculturative stress, self-esteem and eating and eating pathology in Latina and Asian female college students. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(1), 88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins LH, & Lehman J (2007). Eating disorders and body image concerns in Asian American women: Assessment and treatment from a multicultural and feminist perspective. Eating Disorders, 15, 217–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowling M (2008). Atlas.ti (software) In Given L (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (pp. 37–38). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, & Bèglin SJ (1994). Assessment of eating disorders: Interview or self-report questionnaire? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(4), 363–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, & Herzog DB (2007). Cross-ethnic differences in disorder symptoms and related distress. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(2), 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick DA, Forbes GB, Grigorian K, & Jarcho JM (2007). The UCLA Body Project I: Gender and ethnic differences in self-objectification and body satisfaction among 2,206 undergraduates. Sex Roles, 57, 317–327. [Google Scholar]

- Frederick DA, Kelly MC, Latner JD, Sandhu G, & Tsong Y (2016). Body image and face image in Asian American and white women: Examining associations with surveillance, construal of self, perfectionism, and sociocultural pressures. Body Image, 16, 113–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, & Garfinkel PE (1979). The Eating Attitudes Test: An index of the symptoms of anorexia nervosa. Psychological Medicine, 9, 273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DM, Olmstead MP, & Polivy J (1983). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2(2), 15–34. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser BG, & Strauss AL (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KH, Brattole M, Wingate LR, & Joiner TE Jr. (2006). The impact of client race on clinician detection of eating disorder symptoms. Behavior Therapy, 37, 319–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KH, Perez M, & Joiner TE (2002). The impact of racial stereotypes on eating disorder recognition. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 32(2), 219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum T (1998). The handbook for focus group research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Guan M, Lee F, & Cole ER (2012). Complexity of culture: The role of identity and context in bicultural individuals’ body ideals. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 247–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall CC (1995). Asian eyes: Body image and eating disorders of Asian and Asian American women. Eating Disorders, 3, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Herbozo S, Stevens SD, Moldovan CP, & Morrell HER (2017). Positive comments, negative outcomes? The potential downsides of appearance-related commentary in ethnically diverse women. Body Image, 21, 6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javier SJ, & Belgrave FZ (2015). An examination of influences on body dissatisfaction among Asian American college females: Do family, media, or peers play a role? Journal of American College Health. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2015.1031240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawamura KY (2002). Asian American body image In Cash TF & Pruzinsky T (Eds.), Body Image: A handbook of theory, research, and clinical practice (pp. 243–249). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly NR, Cotter EW, Lydecker JA, & Mazzeo SE (2017). Missing and discrepant data on the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): Quantity, quality, and implications. Eating Behaviors, 24, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon Van Diest AM, Tartakovsky M, Stachon C, Pettit JW, & Perez M (2014). The relationship between acculturative stress and eating disorder symptoms: Is it unique from general life stress? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 37(3), 445–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan MY, Gordon KH, & Minnich AM (2018). An examination of the relationships between acculturative stress, perceived discrimination, and eating disorder symptoms among ethnic minority college students. Eating Behaviors, 28, 25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, & Koch GG (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Takeuchi D, Gellis Z, Kendall P, Zhu L, Zhao S, & Ma GX (2017). The impact of perceived need and relational factors on mental health service use among generations of Asian Americans. Journal of Community Health, 42(4), 688–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee-Winn A, Mendelson T, & Mojtabai R (2014). Racial/ethnic disparities in binge eating: disorder prevalence, symptom presentation, and help-seeking among Asian Americans and non-Latino Whites. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7), 1263–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lui PP (2015). Intergenerational cultural conflict, mental health, and educational outcomes among Asian and Latino/a Americans: Qualitative and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 141(2), 404–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton MQ (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Marques L, Alegría M, Becker AE, Chen C, Fang A, Chosak A, & Belo Diniz J (2011). Comparative prevalence, correlates of impairment, and service utilization for eating disorders across U.S. ethnic groups: Implications for reducing ethnic disparities in health care access for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 44(5), 412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer OL, Zane N, Cho YI, & Takeuchi DT (2009). Use of specialty mental health services by Asian Americans with psychiatric disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 1000–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B (2010). Addressing gender and cultural diversity in body image: Objectification theory as a framework for integrating theories and grounding research. Sex Roles, 63, 138–148. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B (2011). Objectification theory: Areas of promise and refinement. The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 153–163. [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B (2013). Discrimination, objectification, and dehumanization: Toward a pantheoretical framework In Gervais SJ (Ed.), Objectification and dehumanization (pp. 153–181). New York, NY: Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, 42 U.S.C. § 18001 (2010).

- Prince M, & Davies M (2001). Moderator teams: an extension to focus group methodology. Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, 4(4), 207–216 [Google Scholar]

- Rowling L (2006). Adolescence and emerging adulthood (12–17 years and 18–24 years) In Cattan M & Tilford S (Eds.) Mental Health Promotion: A Lifespan Approach (pp. 100–136). United Kingdom: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Shea M, Cachelin FM, Gutierrez G, Wang S, & Phimpasone P (2016). Mexican American women’s perspectives on a culturally adapted cognitive-behavioral therapy guided self-help program for binge eating. Psychological Services, 13(1), 31–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart R, Tsong Y, Mejía OL, Hayashino D, & Braaten MET (2011). Therapists’ experiences treating Asian American women with eating disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 42, 308–315. [Google Scholar]

- Stark-Wroblewski K, Yanico BJ, & Lupe S (2005). Acculturation, internalization of Western appearance norms, and eating pathology among Japanese and Chinese international student women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29(1), 38–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Bucceri J, Lin AI, Nadal KL, & Torino GC (2007). Racial microaggressions and the Asian American experience. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velez BL, Campos ID, & Moradi B (2015). Relations of sexual objectification and racist discrimination with Latina women’s body image and mental health. The Counseling Psychologist, 43, 906–935. [Google Scholar]

- Wildes J, Emery R, & Simons A (2001). The roles of ethnicity and culture in the development of eating disturbance and body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 521–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wonderlich SA, Joiner TE, Keel PK, Williamson DA, & Crosby RD (2007). Eating disorder diagnoses: Empirical approaches to classification. American Psychologist, 62(3), 167–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Kim BSK, Nguyen CP, Cheng JK, & Saw A (2014). The interpersonal shame inventory for Asian Americans: Scale development and psychometric properties. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61(1), 119–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying YW, & Han M (2007). The longitudinal effect of intergenerational gap in acculturation on conflict and mental health in Southeast Asian American adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77(1), 61–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama K (2007). The double binds of our bodies: Multiculturally-informed feminist therapy considerations for body image and eating disorders among Asian American women. Women & Therapy, 30(3–4), 177–192. [Google Scholar]