Abstract

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is the leading cause of blindness in the US. Polymorphisms in complement components are associated with increased AMD risk, and it has been hypothesized that an overactive complement system is partially responsible for AMD pathology. Choroidal neovascularization (CNV) has two phases, injury/angiogenesis and repair/fibrosis. Complement activation has been shown to be involved in the angiogenesis phase of murine CNV, but has not been investigated during repair. Anaphylatoxin (C3a and C5a) signaling in particular has been shown to be involved in both tissue injury and repair in other models. CNV was triggered by laser-induced photocoagulation in C57BL/6J mice, and lesion sizes measured by optical coherence tomography. Alternative pathway (AP) activation or C3a-receptor (C3aR) and C5a-receptor (C5aR) engagement was inhibited during the repair phase only of CNV with the AP-inhibitor CR2-fH, a C3aR antagonist (N2-[(2,2-diphenylethoxy)acetyl]-L-arginine, TFA), or a C5a blocking antibody (CLS026), respectively. Repair after CNV was also investigated in C3aR/C5aR double knockout mice. CR2-fH treatment normalized anaphylatoxin levels in the eye and accelerated regression of CNV lesions. In contrast, blockade of anaphylatoxin-receptor signaling pharmacologically or genetically did not significantly alter the course of lesion repair. These results suggest that continued complement activation prevents fibrotic scar resolution, and emphasizes the importance of reducing anaphylatoxins to homeostatic levels. This duality of complement, playing a role in injury and repair, will need to be considered when selecting a complement inhibitory strategy for AMD.

Keywords: complement system, choroidal neovascularization, anaphylatoxin, targeted alternative pathway inhibitor CR2-fH, injury, repair

Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is a slowly progressing disease and the leading cause of blindness for Americans over sixty. The late stage of disease has two forms; wet (neovascular, characterized by angiogenesis) and dry (characterized by atrophy). Based on histological, biochemical and genetic data, it has been hypothesized that an overactive complement system is tied to the incidence of AMD (Mullins et al., 2017). The complement system is part of the adaptive and innate immune systems, and can be activation via three different pathways, namely the classical pathway (CP), lectin pathway (LP) and alternative pathway (AP). All pathways culminate in a common terminal pathway to generate the cytolytic membrane attack complex (MAC) (Muller-Eberhard, 1988). Other complement-derived effector molecules generated during complement activation are the soluble anaphylatoxins (C3a and C5a), and membrane-bound opsonins (C3b/iC3b/C3d/C3dg). Complement is activated by insult or injury, resulting in the recruitment of inflammatory cells and the release of mediators such as enzymes and cytokines, which control tissue damage or repair. Activation of the complement system is controlled by soluble or membrane-bound inhibitors that act either specifically in the activation arms, or jointly to block the common terminal pathway (Noris and Remuzzi, 2013). Importantly, the AP amplifies complement activation triggered by the CP and/or LP (Muller-Eberhard, 1988), making it a particularly attractive therapeutic target.

The complement system in AMD has been the subject of many reviews (e.g., (Geerlings et al., 2016; van Lookeren Campagne et al., 2016)), and key findings can be summarized as follows: 1. Pathological features of AMD contain many proteins, including complement components C3a and C5a, 2. A high concentration of MAC has been reported in the area of Bruch’s membrane in AMD eyes, in particular those with high risk complement factor H genotypes, 3. Complement regulatory proteins required to prevent or limit complement activation, are reduced or mislocalized in AMD eyes. The hypothesis that the AP is critical to AMD pathogenesis was strengthened significantly by reports showing that a polymorphism in the AP control protein factor H is strongly associated with AMD. Based on these findings, many current therapeutic developments focus on reducing complement activation for treatment in AMD.

The most popular animal model to study wet AMD is the model of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization (CNV). By rupturing the RPE and Bruch's membrane by laser treatment, the procedure triggers angiogenesis, modeling the hallmark pathology observed in wet AMD. We have shown that all complement activation pathways participate in CNV development (Rohrer et al., 2011), but have not identified the biological effector molecules of the complement system essential for pathology. The anaphylatoxins C3a and C5a that signal through their respective G-protein-coupled receptors, have been explored initially. The first report demonstrated that C3aR and C5aR signaling augments angiogenesis (Nozaki et al., 2006). A follow-up manuscript however reported that C5a receptor inhibition did not reduce CNV, while C3−/− or C5−/− mice had increased neovascularization compared to controls (Poor et al., 2014). Neither of the two studies identified potential target cells for anaphylatoxin-receptor signaling, which could include retinal pigment epithelial cells, choroidal endothelial cells, fibroblasts, or invading immune cells. These cell types express C3aR and C5aR and respond to anaphylatoxin stimulation (Klos et al., 2009; Rohrer, 2018). The anaphylatoxins are generally considered to contribute to inflammation as part of the host defense system, resulting in the recruitment and activation of leukocytes and macrophages. However, a recent publication suggested that anaphylatoxins may also play a role in tissue repair and regeneration (Alawieh et al., 2015). Hence, we tested the primary hypothesis that continued complement activation interferes with regression of murine CNV, followed by the secondary hypothesis that anaphylatoxin-receptor signaling is required for this repair.

C57BL/6J and C3aR/C5aR double-deficient mice (C3aR−/− C5aR−/−) on a C57BL/6J background (Kwan et al., 2013) were randomly assigned to different treatment groups, and CNV lesions induced as described previously, using argon laser photocoagulation (532 nm, 100 μm spot size, 0.1s duration, 100 mW) to generate four laser spots per eye centered around the optic nerve in 3-4-month-old anesthetized (xylazine and ketamine, 20 and 80 mg/kg, respectively) mice (Rohrer et al., 2009). Inclusion/exclusion criteria for successful lesions proposed by Poor et al., were adopted (Poor et al., 2014). All experiments were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research and were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee. CNV lesion sizes were measured by optical coherence tomography (OCT) analysis, using a SD-OCT Bioptigen® Spectral Domain Ophthalmic Imaging System (Bioptigen Inc.) as reported (Coughlin et al., 2016). Using the Bioptigen® InVivoVue software, rectangular volume scans were performed (1.6 × 1.6 mm; 100 B-scans, 1000 A-scans per B scan), and using the systems en face fundus reconstruction tool the center of the lesion was determined and the image saved. ImageJ software (Wayne Rasband, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) was used to determine the volume of the hyporeflective spots in the fundus image (Giani et al., 2011). Treatments were initiated on day 6 after the lesion and commenced through day 22. The C3aR antagonist TFA (1 μg/g bodyweight; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc), or the AP inhibitor CR2-1H (10 μg/g bodyweight) (Rohrer et al., 2009) were injected intraperitoneally every 48 hrs, the anti-C5a blocking antibody (40 μg/g; CLS026, Alexion Pharmaceuticals) twice a week. TFA has previously been shown to block mouse C3aR (Ames et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2007) and to reduce CNV when used via intravitreal injections (Nozaki et al., 2006). TFA has also been shown to inhibit C3a-receptor signaling in mice when injected systemically at the same dose used here (Kandasamy et al., 2013). Likewise, C5aR antagonist activity of CLS026 has been shown by us and others to reduce T-cell mediated inflammatory diseases in mouse models such as CNV (Coughlin et al., 2016) and allograft vasculopathy (Qin et al., 2016). The fusion protein CR2-fH specifically targets to sites of complement activation via the CR2 moiety that binds C3d, and has been shown to reduce complement-dependent pathology in two ocular models when administered systemically (Rohrer et al., 2009; Woodell et al., 2016). For quantitative determination of mouse C3a (LifeSpan Biosciences, Inc) and C5a (Abcam) in the retina, RPE/choroid tissue homogenates and serum, a sandwich enzyme immunoassay was used. Tissues were rinsed with ice cold PBS to remove excess blood, cells lysed by ultrasonication in the presence of a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich), and homogenates cleared by centrifugation. Measurements were obtained according to the manufacturer’s instructions and as we have previously described (Coughlin et al., 2016)

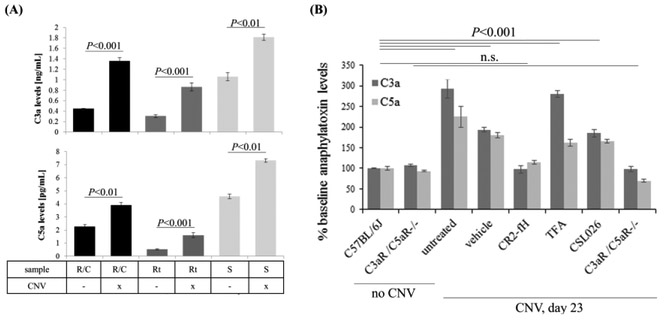

Induction of CNV was shown to result in a rapid increase in C3a and C5a in RPE/choroid samples, with maximum levels reached at 12 hours after injury (Nozaki et al., 2006). We previously demonstrated that C5a levels were still elevated in the RPE/choroid at day 6 after the laser burn (Coughlin et al., 2016). Here we build on these data and show that both C5a and C3a are elevated in RPE/choroid, retina and serum samples of mice 6 days after lesion induction. In serum, both anaphylatoxins were elevated to ~150% over baseline levels, whereas in the retina and RPE/choroid, C3a levels were increased to ~260%, and C5a levels to ~150% (Fig. 1A). Given the fact that the anaphylatoxins remained elevated at the peak of angiogenesis (also considered the onset of the repair period), we hypothesized that they play a role in CNV regression and repair.

Figure 1. Anaphylatoxins are elevated long-term in ocular tissues after induction of choroidal neovascularization.

(A) Anaphylatoxin measurements obtained by ELISA in mouse RPE/choroid (R/C), retina (Rt) and serum (S) samples in control mice and after induction of choroidal neovascularization (CNV). Measurements were obtained on day 6 after CNV induction. R/C, Rt and S samples were collected and analyzed from the same 3 animals per group. C3a levels (top panel) increased ~2.5 fold in the ocular tissues, and ~1.5 in serum; C5a levels (bottom panel) increased ~1.5-1.8 fold in tissues and serum. (B) Effects of treatments (PBS, CR2-fH and C3aR antagonist) and gene knockout (C3aR−/− C5aR−/−) on CNV-mediated changes in anaphylatoxins in mouse RPE/choroid when compared to controls (no CNV) on day 23 after the induction of CNV. CR2-fH prevented the rise in anaphylatoxins when compared to vehicle- and C3aR antagonist-treated mice. C3a and C5a levels were measured using ELISA assays in 2-11 independent tissue samples per condition. Data are presented as mean ±SEM. Statistical significance as indicated reflects changes in individual anaphylatoxin levels in response to CNV (A) or both anaphylatoxins in response to CNV and treatment (B).

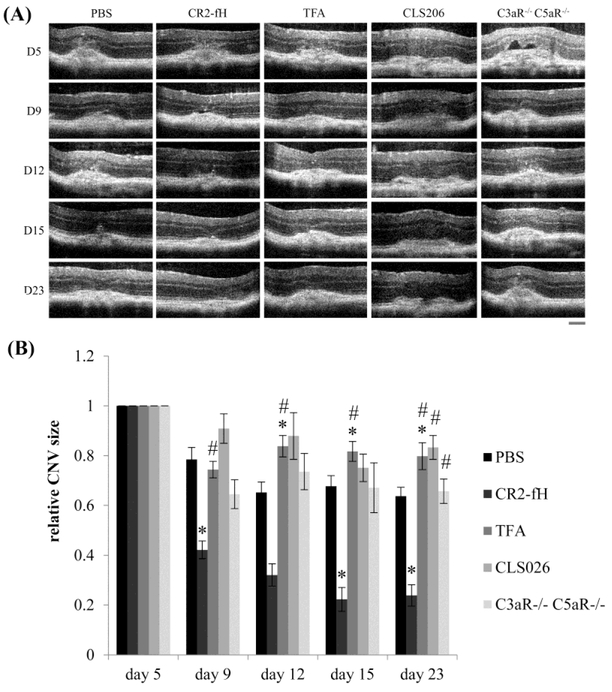

Mouse choroidal neovascularization has two phases, injury/angiogenesis and repair. Maximum size for both CNV lesion area and fluid accumulation is observed at day 5 after the laser burn, followed by slow regression of these parameters (Giani et al., 2011). Hence, we tested whether reducing complement activation by AP inhibition (CR2-fH), or administering either a C3a-receptor antagonist (TFA) or an anti-C5a blocking antibody (CLS026) during the regression phase of CNV starting at day 6 post lesion, would alter the course of repair. Rates of repair were also compared to those in mice in which both anaphylatoxin receptors were eliminated (C3aR−/− C5aR−/−). Repair was examined in a longitudinal study, measuring lesion sizes by OCT over time (Fig. 2A). Repeat measurements reduce the number of animals required for longitudinal studies and decrease inter-animal variability. Here we relied on the observation by Giani and coworkers, who have shown that CNV lesion size and fluid dome assessment by OCT correlates with anatomic markers of cellular infiltration and fibrosis as well as functional activity on fluorescein angiography (Giani et al., 2011). To allow for comparison, all CNV sizes were set to 100% at day 5, and scaled accordingly through day 23 (Fig. 2B). When analyzing lesion sizes at the final time point on day 23 using post-hoc testing (Fisher’s PLSD; StatView, SAS Institute), CR2-fH-treated animals had significantly smaller lesions (P< 0.0001), and TFA- and CLS026-treated animals had larger lesions as compared to PBS-treated mice (P< 0.005). However compared to CR2-fH-treated animals, all other groups had significantly larger lesions (Fig. 2B). For more rigorous testing, treatment responses over time were evaluated using a repeated measure ANOVA. In the analysis of response over time, there was a significant effect of treatment (P<0.0001), time (P<0.0001), and a treatment by time interactions (P<0.005). To determine the contribution of the different treatments to these effects, the mean differences in lesion sizes and slopes of recovery were analyzed, correcting for multiple comparisons. For lesion sizes, when compared to the PBS group, only the CLS026-treated animals were significantly worse (P<0.01). Mice treated with CR2-fH showed improved lesion repair (P<0.0001). When comparing the slopes of repair between the treated groups and controls (PBS), the rate of repair was only affected by CR2-fH, which was faster as compared to PBS (P<0.005).

Figure 2. Tissue repair after induction of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) is dependent on anaphylatoxin signaling.

(A) Lesion sizes were imaged using optical coherence tomography (OCT) in animals that were treated with PBS (n=8; 67 spots), CR2-fH (n=5; 36 spots), C3aR-antagonist (n=5; 40 spots) or anti-C5a blocking antibody (n=10; 78 spots) during the repair phase of CNV (treatment from day 6 through day 23) and the C3aR−/− C5aR−/− mice (n=7; 32 spots). Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Quantification of lesion sizes over time. To be able to compare rates of repair, all lesion sizes per animal were normalized to the respective size at day 5. Slow repair was noted in the PBS-treated mice. Repair was accelerated in mice treated with CR2-fH when compared to PBS controls; whereas in those lacking C3aR-signaling or C5aR-signaling due to pharmacological (receptor antagonists or ligand blocking antibodies) interference, repair was impaired. Data are presented as mean ±stdev. Pairwise comparisons revealed statistically significant changes for comparisons with PBS (*) or CR2-fH (#).

To assess the effects of the treatments on anaphylatoxin levels, C3a and C5a measurements were performed in RPE/choroid fractions at day 23 (Fig. 1B). In PBS treated animals, C3a and C5a levels did not return to baseline by day 23, but rather remained significantly elevated. In comparison, in mice treated with CR2-fH, C3a and C5a levels were normalized to levels seen in age-matched mice without CNV. This is in contrast to mice treated with TFA or CLS026, in which anaphylatoxin levels remained elevated, whereas in C3aR−/− C5aR−/− mice, no CNV-mediated changes in anaphylatoxin levels were observed.

The main results of the study are: 1) CNV triggeres long-lasting complement activation in the eye, such that increased levels of anaphylatoxins were still present 6 and 23 days post lesion; 2) mouse CNV lesions undergo some spontaneous repair; 3) AP-inhibition accelerated CNV regression; and 4) inhibition of anaphylatonxin-receptor signaling does not alter the time course of CNV regression. Thus, our data suggests that CNV lesions trigger long-lasting complement activation in the eye, and that complement inhibition and normalization of anaphylatoxin levels appears to be required for repair mechanisms during the regression phase of CNV.

As a clinically relevant observation, we found that CNV is associated with increased levels of anaphylatoxins in serum and in ocular tissues. It is unlikely that the systemic levels were derived from the eye, but rather, it is more likely due to independent systemic complement activation in response to the release of damaging components from the eye into the circulation. A contribution of the splenic immune response to CNV lesions has been shown by us (Coughlin et al., 2016) and others (Tan et al., 2016). However, irrespective of the source of the anaphylatoxins, it can be argued that elevated serum anaphylatoxin levels, as are found in late-stage neovascular AMD patients (Smailhodzic et al., 2012) and in mouse CNV (our data here), are associated with higher anaphylatoxin levels in the eye.

We also confirmed and extended previously reported data on ocular anaphylatoxin levels in the eye (Nozaki et al., 2006), but our data suggest that changes are long-lasting rather than transient. An order of magnitude calculation, assuming a 1.5 mm3 of RPE/choroid volume and not factoring in the percent extracellular space, suggests basal C3a and C5a levels of 10 nM and 40 pM, respectively, with 4x or 2x increases in response to CNV. Those concentrations are well within functional range, since responses have been detected below nanomolar concentrations for C3a and below picomolar concentrations for purified C5a (Ross, 1986).

CNV in rodents has many contributing factors. Our current understanding is that laser burns lead to local RPE tissue destruction, with a surrounding peri-lesional area marked by oxidative stress (Rohrer, 2012). Within the RPE, an increase in VEGF expression as well as complement production and activation is noted (Nozaki et al., 2006; Rohrer et al., 2009). Immune cells infiltrate the eye rapidly (Tsutsumi-Miyahara et al., 2004), and mononuclear phagocytes (microglia, resident immune cells, or tissue infiltrating macrophages) are present in CNV lesions (Will-Orrego et al., 2018). VEGF-mediated angiogenesis is triggered early (Campa et al., 2008), followed by conversion to fibrosis (He and Marneros, 2013; Liu et al., 2011). While the cellular origins and the underlying mechanisms of how the fibrovascular scars are formed are still incompletely understood (He and Marneros, 2013), the presence of vascular endothelial and fibrotic markers appear to be elevated within one week after CNV, and are sustained over time (Liu et al., 2011).

To date, complement activation has only been analyzed in the angiogenesis phase, and not the fibrosis and regression phase. During the angiogenesis phase, AP inhibition or prevention of MAC formation reduces CNV size when initiated at the time of, or prior to the lesion (Bora et al., 2010; Cashman et al., 2011; Rohrer et al., 2009), and AP inhibition reduces progression even when initiated during the linear phase of CNV growth (Rohrer et al., 2009). The role of anaphylatoxin receptor signaling in angiogenesis has been controversial, with reports documenting smaller CNV sizes in the presence of TFA (Nozaki et al., 2006) or CLS026 (Coughlin et al., 2016), or reporting no effects (Poor et al., 2014). Nevertheless, this combined body of work suggests that the onset of CNV (days 0-6) is a result of multifactorial injury in the eye by a combination of common terminal pathway and/or MAC effects, since inhibition of MAC formation, inhibition of the AP or a combined inhibition of the LP and CP, each individually reduces CNV growth (Bora et al., 2010; Cashman et al., 2011; Rohrer et al., 2011; Rohrer et al., 2009). In comparison, no report has yet focused on the phase of fibrotic scar formation and lesion regression and its ability to be modified by complement inhibitors. Here we show that AP-inhibition accelerated CNV regression, whereas lack of anaphylatoxin-receptor signaling had little or no effect. These observations allow for two conclusions. First, continued complement activation appears to be required to maintain the fibrotic scar, since CNV regression can be accelerated beyond the normal rate by AP inhibition. Second, continued C3a and C5a signaling does not appear to contribute significantly to late stage damage or repair, since elimination of signaling for both receptors did not interfere with regression of the lesions. The results showing that CR2-fH accelerates repair are reminiscent of our data on smoke-induced ocular pathology (Woodell et al., 2016). In that model, we found that mice exposed to long-term smoke develop RPE dysfunction, Bruch’s membrane thickening, and vision loss. Upon smoking cessation, over the course of 3 months, animals treated with CR2-fH showed significant improvement in vision compared to PBS-treated mice, and most morphologic changes in RPE and Bruch's membrane were reversed (Woodell et al., 2016). Taken together; our data support the hypothesis that AP activity plays an important role in driving angiogenesis and fibrosis. The involvement of anaphylatoxins in either tissue damage or repair could not be assessed unequivocally. At the final time point measured (day 23), lesion sizes of TFA- and CLS026-treated animals, but not C3aR−/− C5aR−/− animals, had larger lesions than PBS-treated mice; whereas lesion size over the entire time course was only increased in CLS026-treated animals, .and the time course of repair was not affected by inhibition of either anaphylatoxin receptor. Our receptor inhibitor studies have some limitations. TFA has been reported to have both antagonist and agonist activities on C3aR, depending on the cell type on which the receptor is expressed (Woodruff and Tenner, 2015). Also, we did not perform studies to confirm that the inhibitors are available at therapeutic concentrations in the eye. We have shown previously, however that systemic treatment with CLS026 prevents infiltration of γδT-cells into the eye of CNV animals, and as we found in this study, did not affect ocular C5a levels. A potential technical explanation for this finding may be due to the anti-C5a antibody used in the ELISA recognizing both bound and free C5a (Coughlin et al., 2016). Despite these limitations, the results from the C3aR−/− C5aR−/− mice, which verified the lack of an effect of combined inhibition of anaphylatoxin signaling on the rate of lesion repair, seems to suggest that anaphylatoxin receptor signaling does not play a critical role in tissue repair in CNV.

In summary, appreciating the different phases of CNV and the contributions of the complement system to injury and repair, will be an important consideration when developing a complement inhibitory strategy for the treatment of AMD.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. P Heeger from Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai (New York, USA) for providing us with C3aR−/− C5aR−/− mice for our experiments and Yi Wang at Alexion Pharmaceuticals for providing us with the anti-C5a blocking antibody. This work was sponsored in part by a Department of Veterans Affairs awards RX000444 (BR), RX00114, BX001218 and RX002363 (ST), National Institutes of Health grants EY019320 (BR) and DK102912 (ST), as well as the SmartState Centers of Excellence Endowment (BR). Animal studies were conducted in a facility constructed with support from the NIH (C06 RR015455). NIH (R01DK102912).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Alawieh A, Elvington A, Zhu H, Yu J, Kindy MS, Atkinson C, Tomlinson S, 2015. Modulation of post-stroke degenerative and regenerative processes and subacute protection by site-targeted inhibition of the alternative pathway of complement. J Neuroinflammation 12, 247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames RS, Lee D, Foley JJ, Jurewicz AJ, Tornetta MA, Bautsch W, Settmacher B, Klos A, Erhard KF, Cousins RD, Sulpizio AC, Hieble JP, McCafferty G, Ward KW, Adams JL, Bondinell WE, Underwood DC, Osborn RR, Badger AM, Sarau HM, 2001. Identification of a selective nonpeptide antagonist of the anaphylatoxin C3a receptor that demonstrates antiinflammatory activity in animal models. J Immunol 166, 6341–6348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bora NS, Jha P, Lyzogubov VV, Kaliappan S, Liu J, Tytarenko RG, Fraser DA, Morgan BP, Bora PS, 2010. Recombinant membrane-targeted form of CD59 inhibits the growth of choroidal neovascular complex in mice. J Biol Chem 285, 33826–33833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campa C, Kasman I, Ye W, Lee WP, Fuh G, Ferrara N, 2008. Effects of an anti-VEGF-A monoclonal antibody on laser-induced choroidal neovascularization in mice: optimizing methods to quantify vascular changes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 49, 1178–1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashman SM, Ramo K, Kumar-Singh R, 2011. A Non Membrane-Targeted Human Soluble CD59 Attenuates Choroidal Neovascularization in a Model of Age Related Macular Degeneration. PLoS ONE 6, e19078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin B, Schnabolk G, Joseph K, Raikwar H, Kunchithapautham K, Johnson K, Moore K, Wang Y, Rohrer B, 2016. Connecting the innate and adaptive immune responses in mouse choroidal neovascularization via the anaphylatoxin C5a and gammadeltaT-cells. Sci Rep 6, 23794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerlings MJ, de Jong EK, den Hollander AI, 2016. The complement system in age-related macular degeneration: A review of rare genetic variants and implications for personalized treatment. Mol Immunol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giani A, Thanos A, Roh MI, Connolly E, Trichonas G, Kim I, Gragoudas E, Vavvas D, Miller JW, 2011. In vivo evaluation of laser-induced choroidal neovascularization using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 52, 3880–3887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Marneros AG, 2013. Macrophages are essential for the early wound healing response and the formation of a fibrovascular scar. Am J Pathol 182, 2407–2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandasamy M, Ying PC, Ho AW, Sumatoh HR, Schlitzer A, Hughes TR, Kemeny DM, Morgan BP, Ginhoux F, Sivasankar B, 2013. Complement mediated signaling on pulmonary CD103(+) dendritic cells is critical for their migratory function in response to influenza infection. PLoS Pathog 9, e1003115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klos A, Tenner AJ, Johswich KO, Ager RR, Reis ES, Kohl J, 2009. The role of the anaphylatoxins in health and disease. Mol Immunol 46, 2753–2766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan WH, van der Touw W, Paz-Artal E, Li MO, Heeger PS, 2013. Signaling through C5a receptor and C3a receptor diminishes function of murine natural regulatory T cells. J Exp Med 210, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Wang Y, Cao S, Le R, Bingaman DP, Ornberg R, Sharif N, Romano C, 2011. Natural History of Collagen and Endothelial Markers in Mouse Laser-induced CNV/Subretinal Fibrosis. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 52, 1786–1786. [Google Scholar]

- Muller-Eberhard HJ, 1988. Molecular organization and function of the complement system. Annu Rev Biochem 57, 321–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins RF, Warwick AN, Sohn EH, Lotery AJ, 2017. From Compliment to Insult- Genetics of the Complement System in Physiology and Disease in the Human Retina. Hum Mol Genet. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noris M, Remuzzi G, 2013. Overview of complement activation and regulation. Semin Nephrol 33, 479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozaki M, Raisler BJ, Sakurai E, Sarma JV, Barnum SR, Lambris JD, Chen Y, Zhang K, Ambati BK, Baffi JZ, Ambati J, 2006. Drusen complement components C3a and C5a promote choroidal neovascularization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103, 2328–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poor SH, Qiu Y, Fassbender ES, Shen S, Woolfenden A, Delpero A, Kim Y, Buchanan N, Gebuhr TC, Hanks SM, Meredith EL, Jaffee BD, Dryja TP, 2014. Reliability of the mouse model of choroidal neovascularization induced by laser photocoagulation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 55, 6525–6534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Li G, Kirkiles-Smith N, Clark P, Fang C, Wang Y, Yu ZX, Devore D, Tellides G, Pober JS, Jane-Wit D, 2016. Complement C5 Inhibition Reduces T Cell-Mediated Allograft Vasculopathy Caused by Both Alloantibody and Ischemia Reperfusion Injury in Humanized Mice. Am J Transplant 16, 2865–2876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer B, 2018. Anaphylatoxin Signaling in Retinal Pigment and Choroidal Endothelial Cells: Characteristics and Relevance to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Adv Exp Med Biol 1074, 45–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer B, Bandyopadhyay M, Kunchithapautham K, Thurman JM, 2012. Complement pathways and oxidative stress in Models of Age-Related Macular Degeneration, in: Stratton RD, H.W.W., Gardner TW (Ed.), Studies on retinal and choroidal disorders. Springer, New York Dordrecht Heidelberg London, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer B, Coughlin B, Kunchithapautham K, Long Q, Tomlinson S, Takahashi K, Holers VM, 2011. The alternative pathway is required, but not alone sufficient, for retinal pathology in mouse laser-induced choroidal neovascularization. Mol Immunol 48, e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrer B, Long Q, Coughlin B, Wilson RB, Huang Y, Qiao F, Tang PH, Kunchithapautham K, Gilkeson GS, Tomlinson S, 2009. A targeted inhibitor of the alternative complement pathway reduces angiogenesis in a mouse model of age-related macular degeneration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 50, 3056–3064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross GD, 1986. Immunobiology of the complement system : an introduction for research and clinical medicine. Academic Press, Orlando. [Google Scholar]

- Smailhodzic D, Klaver CC, Klevering BJ, Boon CJ, Groenewoud JM, Kirchhof B, Daha MR, den Hollander AI, Hoyng CB, 2012. Risk alleles in CFH and ARMS2 are independently associated with systemic complement activation in age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmology 119, 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan X, Fujiu K, Manabe I, Nishida J, Yamagishi R, Terashima Y, Matsushima K, Kaburaki T, Nagai R, Yanagi Y, 2016. Choroidal Neovascularization Is Inhibited in Splenic-Denervated or Splenectomized Mice with a Concomitant Decrease in Intraocular Macrophage. PLoS One 11, e0160985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsumi-Miyahara C, Sonoda KH, Egashira K, Ishibashi M, Qiao H, Oshima T, Murata T, Miyazaki M, Charo IF, Hamano S, Ishibashi T, 2004. The relative contributions of each subset of ocular infiltrated cells in experimental choroidal neovascularisation. Br J Ophthalmol 88, 1217–1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Lookeren Campagne M, Strauss EC, Yaspan BL, 2016. Age-related macular degeneration: Complement in action. Immunobiology 221, 733–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will-Orrego A, Qiu Y, Fassbender ES, Shen S, Aranda J, Kotagiri N, Maker M, Liao SM, Jaffee BD, Poor SH, 2018. Amount of Mononuclear Phagocyte Infiltrate Does Not Predict Area of Experimental Choroidal Neovascularization (CNV). J Ocul Pharmacol Ther 34, 489–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodell A, Jones BW, Williamson T, Schnabolk G, Tomlinson S, Atkinson C, Rohrer B, 2016. A Targeted Inhibitor of the Alternative Complement Pathway Accelerates Recovery From Smoke-Induced Ocular Injury. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57, 1728–1737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff TM, Tenner AJ, 2015. A Commentary On: "NFkappaB-Activated Astroglial Release of Complement C3 Compromises Neuronal Morphology and Function Associated with Alzheimer's Disease". A cautionary note regarding C3aR. Front Immunol 6, 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Kimura Y, Fang C, Zhou L, Sfyroera G, Lambris JD, Wetsel RA, Miwa T, Song WC, 2007. Regulation of Toll-like receptor-mediated inflammatory response by complement in vivo. Blood 110, 228–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]