Summary

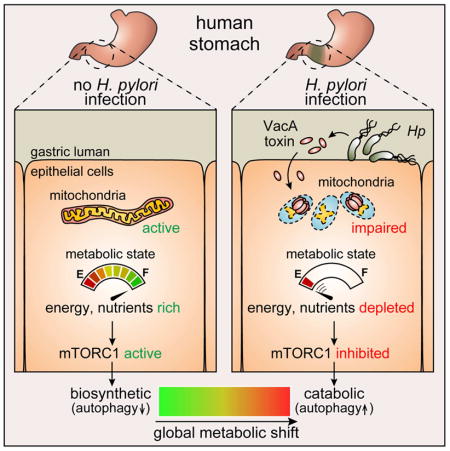

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA) is a bacterial exotoxin that enters host cells and induces mitochondrial dysfunction. However, the extent to which VacA-dependent mitochondrial perturbations affect overall cellular metabolism is poorly understood. We report that VacA perturbations in mitochondria are linked to alterations in cellular amino acid homeostasis, which results in the inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and subsequent autophagy. mTORC1, which regulates cellular metabolism during nutrient stress, is inhibited during Hp infection by a VacA-dependent mechanism. This VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling is linked to the dissociation of mTORC1 from the lysosomal surface, and results in activation of cellular autophagy through the Unc 51-like kinase 1 (Ulk1) complex. VacA intoxication results in reduced cellular amino acids, and bolstering amino acid pools prevents VacA-mediated mTORC1 inhibition. Overall, these studies support a model that Hp modulate host cell metabolism through the action of VacA at mitochondria.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, VacA, vacuolating cytotoxin, metabolism, mTORC1, mTOR, autophagy, mitochondria, mitochondrial dysfunction, amino acid homeostasis, Ulk 1

In Brief

Dysregulation of host metabolism is emerging as an important strategy for microbial remodeling of the infection microenvironment. Kim et al. report a key sensor of host nutritional status, mTORC1, is inhibited by a mitochondrial-targeting bacterial toxin, Helicobacter pylori VacA, resulting in an overall cellular shift from biosynthetic to catabolic metabolism.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (Hp) is a human gastric pathogen that chronically infects approximately half the world’s population (Suerbaum and Josenhans, 2007), resulting in an increased risk for the development of gastric ulcer disease and adenocarcinoma (Polk and Peek, 2010). Colonization of the human gastric epithelium requires that Hp survive the harsh conditions of the stomach, as well as a robust host inflammatory response to infection (Salama et al., 2013). Success in establishing chronic infection largely depends on Hp-mediated remodeling of the gastric environment into a suitable niche for colonization and long-term survival (Salama et al., 2013). There is increasing evidence that pathogenic microbes often target host cell metabolism in order to remodel host epithelial barriers (Eisenreich et al., 2013).

Most strains of Hp secrete vacuolating cytotoxin (VacA), an intracellular-acting, channel-forming toxin (Cover and Blanke, 2005; Kim and Blanke, 2012). The gene encoding VacA is characterized by allelic mosaicism, and several alleles are associated with an elevated risk for gastric disease (Atherton et al., 1995). Intoxication of epithelial cells with VacA results in several well-characterized alterations in cellular physiology, including cytosolic vacuole biogenesis (Leunk et al., 1988), and, the induction of autophagy (Terebiznik et al., 2009; Raju et al., 2012).

VacA is one of the most well studied members of a growing class of microbial effectors that target mitochondria within host cells (Blanke, 2005; Arnoult et al., 2009). Subsequent to cellular internalization, VacA localizes to mitochondria (Galmiche et al., 2000; Calore et al., 2010), and induces organelle dysfunction (Willhite et al., 2003), as manifested by the dissipation of mitochondrial transmembrane potential (ΔΨm) (Kimura et al., 1999; Willhite and Blanke, 2004), increased mitochondrial fragmentation (Jain et al., 2011), and depletion of ATP (Kimura et al., 1999). However, the full extent to which VacA-dependent mitochondrial perturbations affect overall cellular metabolism is poorly understood.

Here, we describe studies demonstrating that Hp infection of gastric cells results in VacA-dependent inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1). In response to nutrient or energy stress, mTORC1 coordinates cellular responses with the goal of re-establishing metabolic homeostasis (Deretic and Levine, 2009; Kroemer et al., 2010; Levine et al., 2011). Within VacA intoxicated cells, we demonstrated that inhibition of mTORC1 signaling positively regulates autophagy, which has been previously linked to VacA (Terebiznik et al., 2009; Raju et al., 2012). Finally, our studies indicated that disruption of amino acid homeostasis within VacA intoxicated cells is causally linked to mTORC1 inhibition. Collectively, these studies indicate that Hp modulate host cell metabolism through the action of VacA.

Results

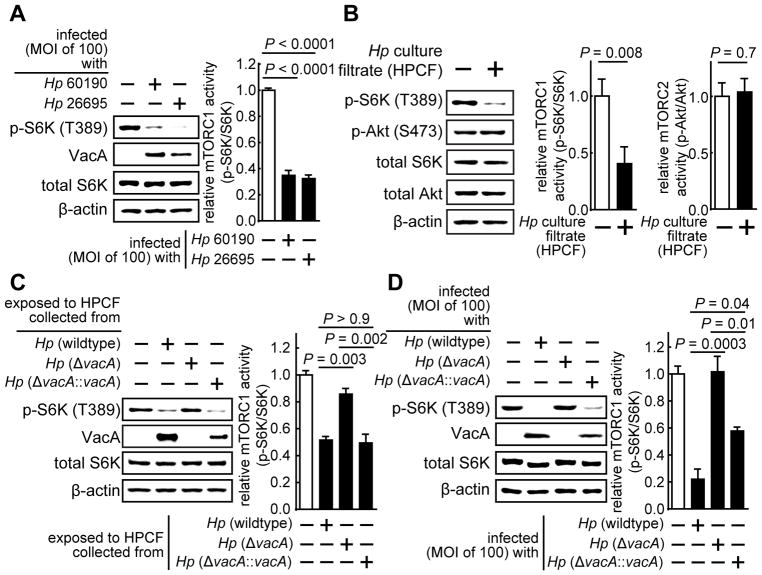

H. pylori inhibit mTORC1 signaling by a VacA-dependent mechanism

In mammalian cells, mTORC1 senses nutrient and energy stress, and, coordinates cellular responses with the goal of re-establishing metabolic homeostasis. To evaluate mTORC1 signaling activity in response to H. pylori (Hp) infection, monolayers of HEK293T cells, which are extensively employed as an in vitro model system for studying mTORC1-mediated regulation (Peterson et al., 2009; Hsu et al., 2011), were incubated, at 37 °C and under 5% CO 2, in the absence or presence of Hp 60190 or Hp 26695 (MOI 100). After 4 h, cell lysates were evaluated using immunoblot analysis to determine relative levels of p70 S6 kinase (S6K) phosphorylated at threonine 389 (p-S6K (T389)), which is a commonly used marker for monitoring cellular mTORC1 signaling activity (Hay and Sonenberg, 2004). In these studies, lower levels of p-S6K (T389) were detected within cells infected with Hp 60190 or Hp 26695 than in mock-infected cells (Fig. 1A), although total cellular S6K levels were not altered. Moreover, lower p-S6K (T389) levels were detected in HEK293T cells exposed to Hp 60190-derived culture filtrates (HPCF) (150 μg/mL) (Fig. 1B), suggesting that the inhibitory factor is a secreted factor. Pretreatment of HPCF at 100 °C for 10 min abolished HPCF-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling activity (Fig. S1A), indicating the involvement of one or more heat-sensitive components. Notably, HPCF did not alter the cellular activity of the mTORC2 complex (Fig. 1B), which regulates cytoskeletal organization and cell proliferation (Laplante and Sabatini, 2009).

Figure 1. H. pylori (Hp) inhibits cellular mTORC1 signaling activity in a VacA dependent manner.

HEK293T cells were infected (MOI of 100) at 37 °C for 4 h in the absence or presence of Hp 26695 strain (A), Hp 60190 (A, D), Hp (ΔvacA) (D), or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA) (D). Alternatively, HEK293T cells were incubated at 37 °C with HPCF prepared from Hp 60190 (B, C), Hp (ΔvacA) (C), or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA) (C). After 4 h, the monolayers were lysed and evaluated by immunoblot analyses for total p70 S6K (total S6K) (A - D), p70 S6K phosphorylated at Thr 389 (p-S6K) (A – D), total Akt (B), Akt phosphorylated at Ser 473 (p-Akt) (B), or, β-actin (A - D). The absence or presence of VacA was confirmed by immunoblot analyses using rabbit VacA antiserum (A, C, D). Immunoblots representative of those collected from 3 independent experiments are shown. For quantification purposes, longer development times for each blot revealed the presence of visible bands in each lane corresponding to p-S6K, which were quantified by densitometry. The data were combined from the 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test (B), or, one-way ANOVA (corrected using the Dunnett’s (A) or the Tukey’s test (C, D)). See also Figure S1.

VacA, which is secreted by Hp, induces mitochondrial dysfunction within gastric epithelial cells. Because mTORC1 is a cellular sensor of energy stress (Inoki et al., 2012), we evaluated whether VacA might be important for HPCF-dependent mTORC1 inhibition. These studies indicated that the inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity was not detected in HEK293T cells when HPCF was pre-incubated with VacA neutralizing antibodies (Fig. S1B). In addition, inhibition of cellular mTORC1 was not detected in HEK293T cells exposed to HPCF prepared from a mutant strain of Hp 60190 lacking the gene encoding VacA (Hp (ΔvacA)) (Fig. 1C). (Vinion-Dubiel et al., 1999). However, inhibition was again detected (Fig. 1C) when HEK293T cells were incubated with HPCF prepared from a complemented Hp strain (Hp(ΔvacA::vacA)) generated by the reintroduction of vacA into Hp (ΔvacA) (McClain et al., 2001). Finally, inhibition of cellular mTORC1 was not detected in cells infected at MOI 100 with Hp (ΔvacA), while, in contrast, cells infected with Hp (ΔvacA::vacA) demonstrated inhibition similar to that detected in cells infected with wildtype Hp 60190 (Fig. 1D). Together, these studies indicated that VacA is required for HPCF-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity.

Phylogenetic analysis of vacA sequences has revealed several distinct groups of vacA alleles (Rudi et al., 1998). Regions of VacA sequence diversity include the signal sequence region (s-region) and the middle region (m-region), with the s1m1 form of VacA generally considered to more cytotoxic in cell culture-based assays than s2m2 (Atherton et al., 1995). Moreover, epidemiological studies have indicated that the risk of gastric disease is higher in persons infected with strains containing type s1 or m1 forms of vacA (Rudi et al., 1998). In our studies, lower levels of p-S6K (T389) were detected within cells infected with Hp 60190 or Hp 26695, both of which secrete the highly active s1m1 allelic form of VacA, than in mock-infected cells (Fig. 1A). Additional studies revealed significantly higher levels of p-S6K (T389) within cells infected with Hp J198 or Hp Tx30a, which secrete the s1m2 or s2m2 forms of VacA, respectively (Fig. S1C), than in cells infected with Hp 26695.

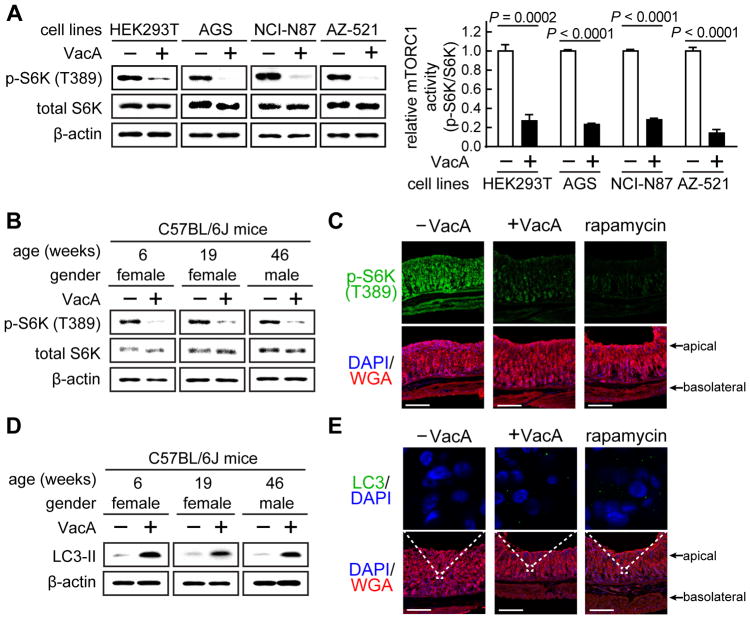

VacA is sufficient for inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity

To evaluate whether VacA alone is sufficient among Hp factors to inhibit cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, monolayers of HEK293T cells were incubated for 4 h at 37 °C in the absence or presence of purified VacA (Fig. S2A). These studies revealed that mTORC1 activity is inhibited in HEK293T cells exposed to purified VacA, but not when toxin was pretreated with VacA-specific antibodies (Fig. S2B). VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 activity is not idiosyncratic to HEK293T cells, but is recapitulated within human-derived AGS (Radin et al., 2011; Raju et al., 2012) and NCI-N87 gastric epithelial cells, as well as AZ-521 duodenal epithelial cells (Fig. 2A), which have been used as in vitro models for studying VacA biology (Gupta et al., 2008; Gupta et al., 2010; Jain et al., 2011). VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity was also detected within primary gastric epithelial cells from C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 2B). Finally, we observed VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling activity within an ex vivo gastric tissue slice model derived from the stomachs of C57BL/6J mice (Koerfer et al., 2016) (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2. VacA is sufficient to modulate cellular mTORC1 signaling and autophagic activities.

HEK293T, AGS, NCI-N87, AZ-521 (A), or, primary gastric epithelial cells (B, D) and gastric tissue slices (C, E) isolated from C57BL/6J mice were incubated for 4 h with VacA (250 nM), or, rapamycin (1 μM) (C, E), followed by immunoblot analyses for total S6K (A, B), p-S6K (Thr 389) (A, B), LC3-II (D), or, β-actin (A, B, D). The tissue slices were fixed and evaluated by fluorescence microscopy analyses for relative p-S6K (C) or the presence of LC3-enriched puncta (E). Immunoblots representative of those collected from 3 independent experiments are shown in A. For each cell line, the data were combined from the 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) in A was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test. Immunoblots shown in B and D were generated using primary cells collected on 3 separate days from 3 different mice differing in age and gender as indicated. Fluorescence images shown in C and E are representative of those using tissue collected from stomachs of 3 different mice. White bars indicate 200 μm. See also Figure S2 and S3.

VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity is causally linked to autophagy induction

In response to metabolic stress, inhibition of mTORC1 activates several cellular processes in order to re-establish metabolic homeostasis (Kroemer et al., 2010). Autophagy is a mechanism by which intracellular components are engulfed and degraded within specialized autophagic vesicles, called autophagosomes, resulting in the recycling and redirecting of biosynthetic building blocks to mitochondria for ATP production (Kaur and Debnath, 2015). Previous studies reported VacA to be both essential and sufficient for Hp activation of autophagy (Terebiznik et al., 2009; Raju et al., 2012; Tsugawa et al., 2012), but did not address the mechanism underlying VacA-dependent autophagy induction. In preliminary studies, we confirmed VacA-dependent activation of cellular autophagy in HEK293T cells, which had not been previously reported, as indicated by toxin-dependent increases in levels of microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain (LC3-II) levels (Fig. S3). LC3-II is commonly used as a surrogate marker for autophagic flux, and previous studies have demonstrated that increases in LC3-II within VacA intoxicated cells reflect toxin-dependent increases in cellular autophagic vesicles (Terebiznik et al., 2009; Raju et al., 2012; Tsugawa et al., 2012). Additional studies revealed that cellular LC3-II levels were significantly greater in HEK293T cells infected at MOI of 100 with either wildtype Hp 60190 or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA), than with Hp (ΔvacA) (Fig. S4A), supporting the importance of VacA during Hp infection for autophagy activation. VacA-dependent autophagy activation was also detected in primary murine gastric epithelial cells (Fig. 2D), and, in our ex vivo derived gastric tissue slice model (Fig. 2E). VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling and activation of autophagy were both detected after 4 h at VacA concentrations as low as 35 nM (Fig. S3A), and, as soon as 1 h after exposure of cells to VacA at 250 nM (Fig. S3B).

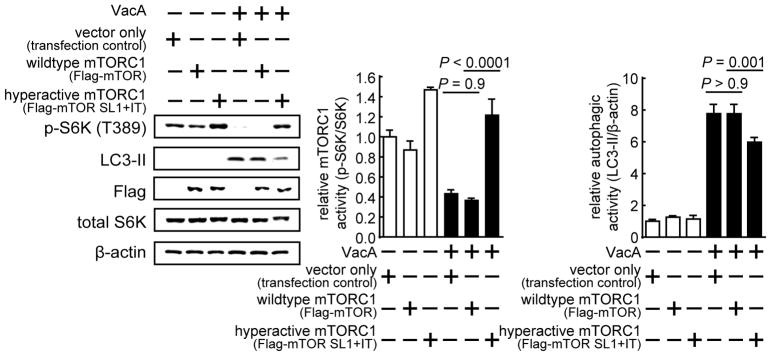

Cellular autophagy can be induced by mTORC1-dependent and -independent mechanisms (Sarkar, 2013). To evaluate whether VacA-dependent mTORC1 inhibition is causally linked to autophagy, we examined VacA intoxication of cells expressing a constitutively active form of mTORC1. HEK293T cells were transfected with a plasmid harboring the gene encoding an altered form of mTORC1, which in the literature has been referred to as “hyperactive mTOR” (mTOR SL1+IT) (Ohne et al., 2008). mTOR SL1+IT possesses mutations that confer sustained mTORC1 activity, even under conditions of nutrient deprivation that normally result in the inhibition of mTORC1. If VacA-dependent autophagy induction occurs via an mTORC1-dependent mechanism, we would predict at least a partial reduction in autophagy within VacA intoxicated cells expressing hyperactive mTOR. To test this prediction, HEK293T cells overexpressing either wildtype mTOR or mTOR SL1+IT were incubated for 4 h in the absence or presence of purified VacA (250 nM). Immunoblot analyses confirmed the expression of FLAG-mTOR SL+IT or wildtype FLAG-mTOR (Fig. 3). These studies revealed that, in VacA intoxicated cells overexpressing FLAG-mTOR SL+IT, there was both an increase in cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, and, a reduction in cellular autophagy, relative to cells overexpressing wildtype FLAG-mTOR (Fig. 3). These results are consistent with a model that cellular autophagy within VacA intoxicated cells is induced by an mTORC1-dependent mechanism.

Figure 3. VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity is causally linked to autophagy induction.

Transiently transfected HEK293T cells overexpressing Flag-mTOR, Flag-mTOR SL1+IT, or, the vector only, were incubated at 37 ° C for 4 h with VacA (250 nM), followed by immu noblot analyses for total S6K, p-S6K (Thr 389), LC3-II, β-actin, or, the Flag-tagged mTOR constructs. The data were combined from 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using one-way ANOVA (corrected using the Tukey’s test). See also Figure S3.

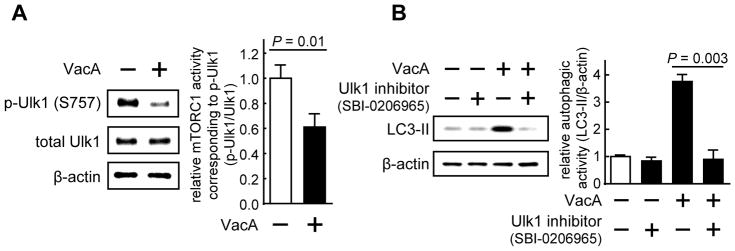

VacA inhibition of mTORC1 activates Ulk1, a positive regulator of autophagy

To further investigate the mechanistic link between VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity and increases in cellular autophagy, we evaluated the potential involvement of the Unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1 (Ulk1) complex in mediating mTORC1-dependent regulation of autophagy induction in VacA intoxicated cells. When activated, the Ulk1 complex positively regulates VPS34 lipid kinase-dependent autophagosome biogenesis (Russell et al., 2013). In the absence of cellular metabolic stress, mTORC1 negatively regulates the Ulk1 complex through phosphorylation of serine 757 (p-Ulk1 (S757)), resulting in suppression of Ulk1 complex activation and autophagy induction (Kim et al., 2011). Conversely, during cellular stress, inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling results in the reduction of cellular p-Ulk1 (S757), thereby activating the Ulk1 protein kinase complex to promote autophagosome biogenesis. Within HEK293T cells, our studies revealed a significant VacA-dependent reduction in cellular p-Ulk1 (S757) levels (Fig. 4A). Additional studies revealed that cellular levels of p-Ulk1 (S757) were significantly lower in HEK293T cells infected at MOI of 100 with either wildtype Hp 60190 or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA), than with Hp (ΔvacA) (Fig. S4B), supporting the importance of VacA during Hp infection for the activation of the Ulk1 protein kinase complex. These results are consistent with a model that mTORC1-dependent regulation of autophagy induction within VacA intoxicated cells is mediated through activation of the Ulk1 protein kinase complex.

Figure 4. VacA inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity is associated with decreased Ulk1-mediated repression of autophagosome biogenesis.

HEK293T cells were pre-incubated at 37 °C for 30 min without (A) or with (A, B) SBI-0206965 (50 μM), and then incubated for 4 h with VacA (250 nM), and then analyzed for total Ulk1 (A), p-Ulk1 (S757) (A), LC3-II (B), or, β-actin (A, B). Data were combined from 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test. See also Figure S4.

VacA-dependent increases in cellular LC3-II levels require Ulk1 protein kinase activity

To evaluate a direct role for the Ulk1 protein kinase complex in VacA-dependent autophagy activation, we examined the effects of inhibiting Ulk1 kinase activity on cellular LC3-II levels. HEK293T cells were pre-incubated at 37 °C with an Ulk1 inhibitor SBI-0206965 (50 μM) (Egan et al., 2015). After 30 min, the cells were further incubated for 4 h in the presence of purified VacA (250 nM). These experiments revealed significantly less LC3-II in the presence than absence of SBI-0206965 (Fig. 4B), indicating that induction of VacA-dependent autophagy requires Ulk1 protein kinase activity. Because Ulk1 protein kinase activity is directly regulated by mTORC1 signaling, these results further support a model that VacA-dependent activation of cellular autophagy occurs by an mTORC1-dependent mechanism.

mTORC1 dissociates from lysosomal membranes in a VacA-dependent manner

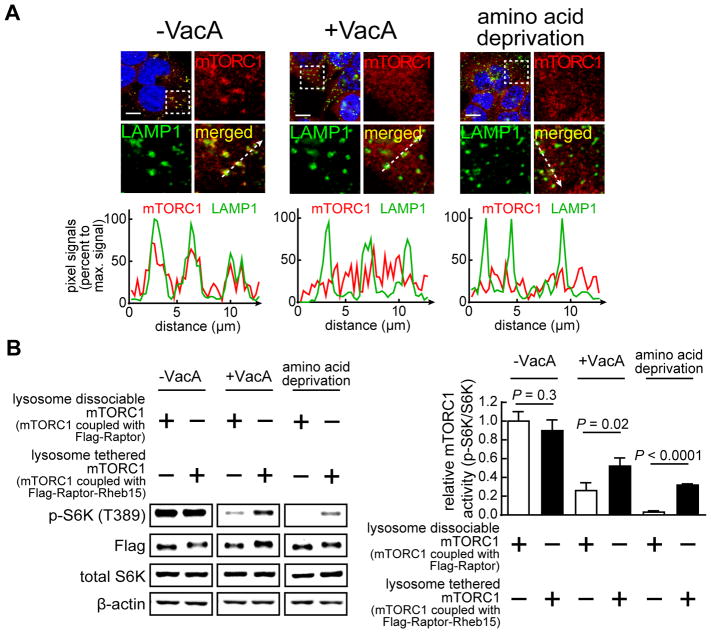

Our studies thus far have not addressed the mechanism by which VacA intoxication ultimately inhibits cellular mTORC1 signaling. Because VacA induces mitochondrial dysfunction, we considered the possibility that nutrient stress might contribute to the reduction in mTORC1 signaling activity. Under nutrient-rich conditions, mTORC1 signaling is activated through direct interactions with a lysosomal membrane protein complex called the Ragulator-Rag docking platform (Sancak et al., 2010). The mTORC1 docking to Ragulator-Rag stabilizes interaction of mTORC1 with the lysosomal membrane protein called “Ras homolog enriched in brain” (Rheb), which functions as a direct activator of mTORC1 signaling (Laplante and Sabatini, 2009; Sancak et al., 2010). Conversely, under conditions of nutrient stress, mTORC1 dissociates from the lysosomal Ragulator-Rag docking platform into the cytosol as an inactive complex, thereby resulting in a loss of mTORC1-mediated signaling (Sancak et al., 2010). To evaluate the possibility that the VacA-dependent reduction in cellular mTORC1 activity might involve the dissociation of mTORC1 from lysosomal compartments, we investigated whether mTORC1 localization is altered within VacA intoxicated cells. Fluorescence microscopy revealed reduced mTORC1 localization to lysosomal compartments in cells exposed to VacA, compared to cells not exposed to toxin (Fig. 5A). Additional studies revealed less mTORC1 localization to lysosomal compartments in HEK293T cells infected at MOI of 100 with either wildtype Hp 60190 or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA) than with Hp (ΔvacA) (Fig. S5). Together, these results support a model that VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity might result from inactivation of mTORC1 upon dissociation from lysosomal compartments.

Figure 5. VacA-dependent mTORC1 dissociation from lysosomal-enriched compartments is causal for toxin-dependent reduction in cellular mTORC1 activity.

(A) Monolayers of HEK293T cells were incubated at 37 °C for 4 h with VacA (250 nM), or, for 1 h in amino acid depleted medium before imaging with confocal fluorescence microscopy. Red puncta indicate mTORC1; green puncta indicate LAMP1; yellow puncta indicate mTORC1 co-localized with LAMP1; blue staining indicates nuclei; white bars indicate 10 μm. The white dashed boxes were digitally enlarged and shown in the other quadrants. The relative pixel signals for mTORC1 and LAMP1 (normalized to maximum pixel intensity) along the white dashed arrows (bottom right quadrants) were rendered as intensity profile graphs. The degree of overlay for the two-dimensional pixel intensity plots corresponds to the relative level of co-localization of mTORC1 with LAMP1. (B) Stably transfected HEK293T cells overexpressing Flag-Raptor, or, Flag-Raptor-Rheb15 were incubated at 37 ° for 4 h without or with VacA (250 nM), or, for 1 h in amino acid depleted medium. After incubation, the cells were evaluated by immunoblot analyses for total S6K, p-S6K, and, β-actin. Data were combined from the 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test. See also Figure S5.

VacA-dependent mTORC1 dissociation from lysosomal-enriched compartments is causal for toxin-dependent reduction in cellular mTORC1 activity

To evaluate whether lysosomal dissociation of mTORC1 is required for VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1, we investigated VacA-dependent changes in cellular mTORC1 signaling under conditions where a portion of cellular mTORC1 was prevented from dissociating from the surface of lysosomal compartments. For these studies, we employed cells overexpressing a chimeric protein called Raptor-Rheb15, consisting of Raptor, a component of mTORC1 that mediates interactions between mTORC1 and the lysosomal Ragulator-Rag docking platform (Laplante and Sabatini, 2009), and, the carboxyl-terminal 15 residues of Rheb comprising the lysosomal targeting motif (Sancak et al., 2010). In cells expressing Raptor-Rheb15, mTORC1 is effectively tethered to lysosomal membranes in a manner that mTORC1 dissociation cannot occur, even under conditions of nutrient stress, thereby resulting in sustained mTORC1 cellular signaling. Studies conducted with VacA-intoxicated HEK293T monolayers yielded higher levels of p-S6K (T389) within cells overexpressing the Raptor-Rheb15 chimera than in cells expressing wild type Raptor (Fig. 5B). These results are consistent with a mechanism of VacA-dependent mTORC1 inhibition requiring mTORC1 dissociation from lysosomal compartments. These results also suggest that nutrient stress within VacA intoxicated cells might underlie toxin-dependent reduction in mTORC1 signaling activity.

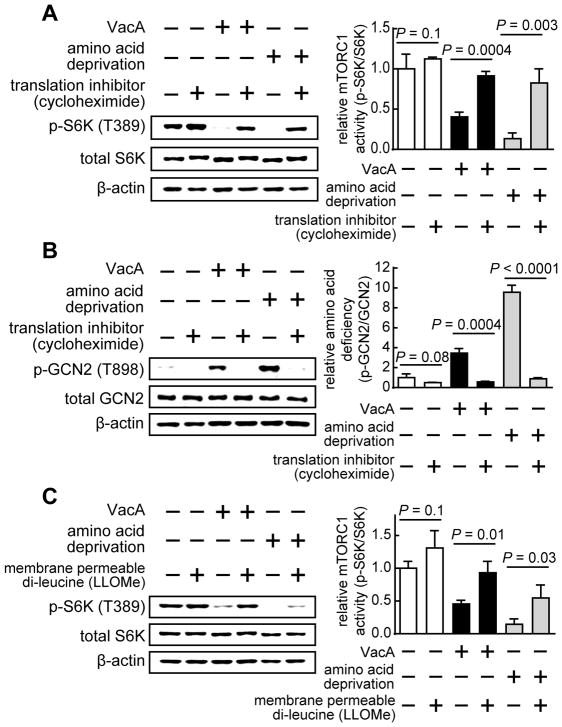

Inhibition of de novo protein synthesis prevents VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity

Amino acid starvation is a form of nutrient stress that can promote mTORC1 dissociation from lysosomes (Zoncu et al., 2011). To evaluate the possibility that VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity might result from depletion of available amino acid pools, we examined whether inhibition of cellular protein synthesis, which has been employed as a strategy to limit deficiencies in cellular amino acid levels (Zoncu et al., 2011), might mitigate VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity. HEK293T cells were incubated at 37 °C in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM) for 3.5 h, and then further incubated for 30 min at 37 °C in the absence or presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (10 μM). In monolayers exposed to VacA, these studies revealed higher levels of cellular p-S6K (T389) in the presence than absence of cycloheximide (Fig. 6A). These results suggest that disruption of amino acid homeostasis within VacA intoxicated cells might be linked to toxin-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling.

Figure 6. Cellular amino acid deficiency is detected within VacA intoxicated cells, which is causally associated with the inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity.

HEK293T cells were incubated for 3.5 h in the absence or presence of purified VacA (250 nM), or, for 30 min in amino acid depleted medium, and then for 30 min in the absence or presence of cycloheximide (10 μM) (A, B), or LLOMe (0.5 mM) (C). The cells were evaluated for total S6K (A, C), p-S6K (A, C), total GCN2 (B), p-GCN2 (B), or, β-actin (A - C). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test for data combined from the 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). See also Figure S6.

VacA intoxication leads to depletion of cellular amino acid pools

To more directly evaluate the possibility that VacA intoxication might result in disruption of cellular amino acid homeostasis, we monitored the phosphorylation state of the general control nonderepressible 2 (GCN2) protein, a serine/threonine kinase that senses cellular amino acid deficiencies (Dever and Hinnebusch, 2005). Specifically, we examined the autophosphorylation state at Thr 898 of GCN2 (p-GCN2 (T898)), which increases as available pools of amino acids are depleted (Dever and Hinnebusch, 2005). These studies revealed a VacA-dependent elevation in cellular levels of p-GCN2 (T898) (Fig. 6B), indicating that intracellular levels of amino acids had been depleted. In support of this conclusion, the elevation of cellular p-GCN2 (T898) was not detected in cells exposed to both VacA and the protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide (Fig. 6B). Additional studies revealed that cellular levels of p-GCN2 (T898) were significantly higher in HEK293T cells infected at MOI of 100 with either wildtype Hp 60190 or Hp (ΔvacA::vacA), than with Hp (ΔvacA) (Fig. S6A). Finally, we observed VacA-dependent increases in p-GCN2 (T898) within an ex vivo gastric tissue slice model derived from the stomachs of C57BL/6J mice (Fig. S6B). These results are all consistent with the model that intracellular levels of amino acids are depleted in a VacA-dependent manner. Indeed, the levels of intracellular amino acids were experimentally determined to be significantly lower in HEK293T cells that had been incubated in the presence than absence of VacA (Fig. S6C). Together, these results further supported the idea that disruption of intracellular amino acid homeostasis is a consequence of VacA cellular intoxication that may contribute to toxin-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling activity and autophagy activation.

Blocking mTORC1 sensing of VacA-dependent disruption of amino acid homeostasis impedes inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity

Amino acids play an important role in regulating mTORC1 signaling by promoting the lysosomal localization and activation of mTORC1 (Zoncu et al., 2011). Leucine is of particular importance because Sestrin2, an intracellular leucine sensor, positively regulates the capacity of the lysosomal Ragulator-Rag complex to serve as a docking platform and activate mTORC1 (Wolfson et al., 2016). To more directly evaluate a potential association between a shortage of intracellular amino acids and VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 cellular signaling, we examined whether VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity could be alleviated in the presence of L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester (LLOMe), a membrane permeable derivative of leucine that can rapidly enter cells in a manner not requiring a transporter-mediated uptake mechanism (Manifava et al., 2016). LLOMe has been previously used to rescue mTORC1 activity under conditions of amino acid starvation (Manifava et al., 2016). Our studies revealed that cellular p-S6K (T389) levels were greater in the presence than absence of LLOMe (Fig. 6C) within VacA intoxicated HEK293T cells, providing additional support for a model that VacA-mediated inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity is a consequence of intracellular amino acid depletion.

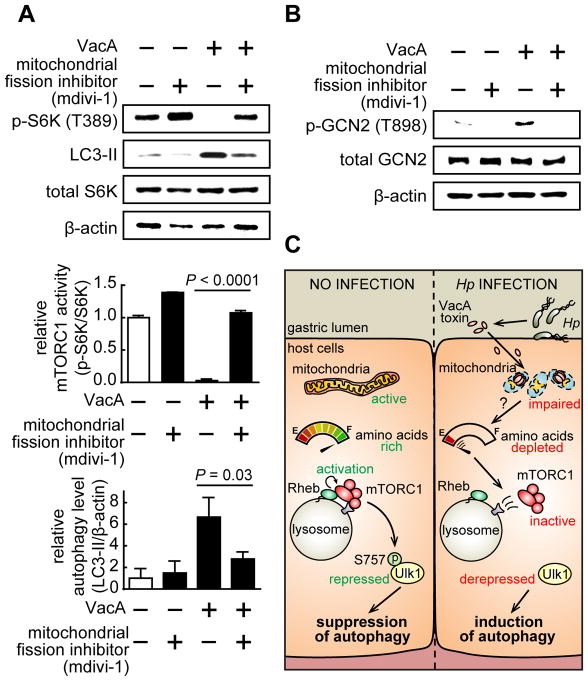

VacA disruption of host mitochondrial dynamics is associated with the inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity and autophagy activation

To evaluate the causal relationships between VacA-mediated mitochondrial perturbations, inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, and, autophagy activation, HEK293T cells were pre-incubated in the absence or presence of mdivi-1 (200 μM), a mitochondrial fission inhibitor that was previously reported to block VacA-dependent fragmentation of mitochondria (Jain et al., 2011). These studies revealed that in the presence of mdivi-1, VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, as well as autophagy activation, was effectively blocked (Fig. 7A). Moreover, mdivi-1 inhibited VacA-dependent phosphorylation of Thr 898 of GCN2 that normally accompanies amino acid depletion (Fig. 7B). These data suggest that VacA perturbations in mitochondrial structure disrupt cellular amino acid homeostasis, which is sensed by mTORC1, and, ultimately results in autophagy activation.

Figure 7. VacA disruption of host mitochondrial dynamics is associated with the inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity and autophagy activation.

(A and B) HEK293T cells were pre-incubated at 37 °C with mdiv i-1 (200 μM), and then further incubated with 37 °C with purified VacA (250 nM) in 3 independent experiments (represented as mean ± SD). After 4 h, the cells were evaluated for total S6K (A), p-S6K (A), total GCN2 (B), p-GCN2 (B), LC3-II (A) or, β-actin (A, B). Statistical significance (α = 0.05) was calculated using the two-tailed Student’s t test. (C) Proposed model for the mechanism of VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling and autophagy induction. See also Figure S7.

The mitochondrial-targeting, amino-terminal p34 fragment of VacA is sufficient for inhibition of cellular mTORC1 activity

To further characterize VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, we ectopically expressed, within the cytosol of HEK293T cells, an amino-terminal fragment of VacA (p34) that, despite lacking the carboxyl-terminal domain (p55) required for the cell-surface binding and uptake of full-length VacA, is sufficient to target mitochondria and induce mitochondrial dysfunction (Galmiche et al., 2000). In our studies, a significant depletion of cellular p-S6K (T389) was detected in transiently transfected HEK293T cells ectopically expressing p34 (Fig. S7A). The sufficiency of the mitochondrial-targeting p34 fragment of VacA for modulating mTORC1 signaling activity strongly supports the importance of VacA-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction for inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity.

The cytosol of cells intoxicated with VacA are often vacuolated (Cover and Blaser, 1992), but the functional relationship between vacuole biogenesis and VacA-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction is poorly understood. In our studies, cellular vacuolation was not detected in transiently transfected HEK293T cells ectopically expressing p34 (Fig. S7B), as previously reported (Ye et al., 1999). These results suggest that cellular vacuolation is not causally linked to VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1. In further support of this model, inhibition of the vacuolar ATPase with bafilomycin A1 fully blocked vacuolation in HEK293T cells intoxicated with full length VacA (Fig. S7C), as previously reported (Papini et al., 1993). In contrast, bafilomycin A1 did not detectably affect VacA-dependent inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity, or, activation of the Ulk1 protein kinase complex (Fig. S7D).

Discussion

There is increasing evidence that host metabolism is frequently targeted by microbes for modulation (Eisenreich et al., 2013). VacA is an intracellular-acting bacterial exotoxin produced by Hp that, subsequent to uptake into gastric cells, alters mitochondrial function (Kimura et al., 1999) and dynamics (Jain et al., 2011). Given the importance of mitochondria for energy production, we predicted that, during Hp infection, biosynthetic metabolism within host cells might be altered through the action of VacA. Here, our studies revealed that VacA is both necessary and sufficient for Hp-mediated inhibition of mTORC1 regulatory signaling. (Fig. 7C). mTORC1 is an energy and nutrient sensor that integrates both intracellular and extracellular signals. Nutritional or energy stress negatively regulates mTORC1 (Dibble and Manning, 2013), resulting in a global cellular shift to catabolic processes, such as autophagy, which contribute to re-establishing metabolic balance (Kroemer et al., 2010). Indeed, our data indicate that VacA-dependent reduction in cellular amino acid levels leads to the activation of cellular autophagy through the inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling.

Several previous studies reported Hp-mediated changes within infected cells that involve mTORC1-mediated signaling. Hp-mediated activation of hemeoxygenase-1 (HO-1), an inflammatory regulator of adaptive immune responses, requires mTORC1 positive regulation (Ko et al., 2016). mTORC1 signaling also mediates hypoxia inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) driven G0/G1 cell cycle arrest during Hp infection (Canales et al., 2017). Most recently, Hp strains lacking active VacA were demonstrated to negatively regulate autophagy through c-Met-PI3K/Akt-mTOR, by a mechanism involving the Hp type IV secretion effector, cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) (Li et al., 2017). In these same studies, infection with Hp strains expressing active VacA, but lacking active CagA, was reported to upregulate cellular autophagy (Li et al., 2017). These results imply that VacA and CagA affect host cell mTOR signaling in distinct ways and, as previously suggested, these two virulence factors may function antagonistically during Hp infection (Yokoyama et al., 2005; Oldani et al., 2009). We did not investigate potential antagonistic interactions between CagA and VacA in these studies, but our results here extend earlier work by demonstrating that VacA, both alone and in the context of Hp infection, is both necessary and sufficient to modulate mTORC1 signaling leading to autophagy activation.

Our studies revealed that inhibition of cellular mTORC1 is associated with VacA-dependent amino acid starvation. Amino acid homeostasis in cells is tightly controlled through the balance of amino acid synthesis, uptake, and utilization. While the exact mechanism underlying disruption of cellular amino acid homeostasis within VacA intoxicated cells is currently unknown, several cell surface pore-forming toxins including Streptoccocal α-toxin, Streptolysin O, and, Vibrio cholerae cytolysin are thought to induce amino acid starvation in host cells (Kloft et al., 2010) by disrupting the electrochemical ion gradients across the plasma membrane required for amino acid transport uptake systems (Hyde et al., 2003). In the case of Hp, we speculate that VacA-dependent perturbations in mitochondrial structure may be important, as inhibition of toxin mediated mitochondrial fragmentation prevented amino acid depletion (Fig. 7B), as well as mTORC1 inhibition and autophagy activation (Fig. 7A). Although a mechanistic association between mitochondrial dynamics and mTORC1 has not been explored in depth, it is noteworthy that a potential link was recently reported between mitochondrial fission and mTORC1-mediated regulation of autophagy in cells exposed to ionizing radiation-induced stress (Wu et al., 2017).

Evidence is emerging that mTORC1 functions as a center of host cell signaling during bacterial infections (Jaramillo et al., 2011; Mohr and Sonenberg, 2012; Tattoli et al., 2012; Lu et al., 2015). For example, within a Drosophila infection model, the intracellular action of monalysin, a pore-forming toxin of Pseudomonas entomophila, impairs mTOR-dependent host innate immune responses and repair programs (Chakrabarti et al., 2012). A second example is the enhancement of mTORC1 signaling activity by the Shigella type-III effector OspB in a manner that depends on IQGAP1, thereby promoting proliferation of host cells as a replicative niche during intracellular infection (Lu et al., 2015). As a third example, during Legionella pneumophila infection, two distinct families of the bacterial effectors can positively or negatively impact mTORC1 signaling activity within host cells as a means of regulating the availability of amino acid pools for the auxotrophic intracellular bacterium (De Leon et al., 2017). As these examples illustrate, mTORC1, as a central sensor and regulator of host cell nutrient availability, would be expected to be an attractive target of pathogens attempting to establish an intracellular niche.

In addition, because of the importance of mTORC1 in regulating protein translation, microbial modulation of mTORC1 activity might also be expected to affect the capacity of host cells to synthesize the components necessary to mount an effective antimicrobial response. Indeed, we speculate that VacA-dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling downregulates biosynthetic metabolism in a manner that might impede the production of immune effectors at the gastric barrier required to clear Hp infection. Although this idea remains to evaluated experimentally, the results described here provide the framework for ongoing studies to understand how mitochondrial alterations induced by VacA reshape the overall metabolic state of host cells during Hp infection.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Steven Blanke (sblanke@illinois.edu)

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Mammalian cell lines

Mammalian cells were maintained within a humidified environment and under 5% CO2 at 37 °C. HEK293T (human embryonic kidney, fetus), NCI-N87 (human gastric epithelial, male), AGS (human gastric epithelial, female), AZ521 cells (human duodenal epithelial, male) were maintained in Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with FBS (10%; Sigma-Aldrich) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%; Sigma-Aldrich). AZ521 cells were maintained in Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEM) (Cellgro) supplemented with FBS (10%) and penicillin/streptomycin (1%). Cells were seeded in 24 well plates or in chamber microscopy slides (Thermo Fisher) at an appropriate cell confluency not exceeding 90% (3 × 104 cells/well). To enhance cellular attachment for HEK293T cells, plates and slides were pre-coated with Rat tail-purified collagen I (50 μg/mL; Gibco), as described by the manufacturer.

H. pylori infection studies

H. pylori (Hp) 60190 strain (cag PAI+, vacA s1m1, ATCC 49503), VM022 (a strain that is isogenic to 60190, except for deletion of vacA) (Vinion-Dubiel et al., 1999), VM084 (VM022 complemented by the reintroduction of vacA) (McClain et al., 2001), 26695 (cag PAI+, vacA s1m1), J198 (cag PAI+, vacA s1m2), or, Tx30a (cag PAI-, vacA s2m2) were inoculated as a suspension in 4 mL bisulfite/sulfite-free Brucella (BSFB) broth (0.1% dextrose, 0.2% β-cyclodextrin, 0.5% NaCl (all from Sigma-Aldrich), and, 1% tryptone, 1% peptone, and 0.2% yeast extract (all from BD Bacto), and incubated at 37 °C and with humidification on top of 2% agar pla tes made of Ham’s F-12 media (Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Sigma-Aldrich), in a microaerophilic environment (10% O2, 5% CO2). After 2 days, the bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation at 5000 xg for 1 min, and the bacterial pellets were suspended in the infection medium (Dulbecco’s Modification of Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% FBS. The concentration of motile, curved bacilli, which are highly associated with CFU, was determined by hemocytometer counting using phase contrast microscopy. HEK293T cells were infected with Hp bacteria (MOI of 100) at 37 °C, with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment. After 3.5 h, fresh infection medium containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) (4 times the volume of the initial infection volume) was added to the infections (to supplement nutrients that may have been depleted by Hp bacteria). In the absence of Hp, inhibition of cellular mTORC1 signaling activity in mammalian cells was not detected after 4 h incubation under the conditions described above.

Housing conditions for experimental animals

All experiments involving the use of live vertebrate animals were conducted under the approval of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (protocol number: 15238). Animal populations were composed of 9 male and 9 female C57BL\6J mice (Jackson Laboratory), aged 6 to 19 weeks. Animals were group housed within humidified environment (50%) with a mean temperature of 22.1 °C, under a 12 h light-dark cyc le, and provided food and water ad libitum. Mice were randomly selected for experiment without gender preference, with both male and female mice included in experiments. Influence of gender between male and female was not observed in this study, hence not further investigated.

Preparation of primary gastric epithelial cells from mice

Cultures of primary mouse gastric epithelial cells were established as previously described (Smoot et al., 2000), with modifications. Whole stomach specimens were collected by necropsy following euthanasia by CO2 inhalation. The fore stomach was removed by gross dissection, and the remaining gastric tissue was opened along the greater curvature. The mucosal surface was rinsed thoroughly with ice cold PBS (pH 7.4). The tissue was minced using scissors, and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and under 5% CO2 within a humidified environment, in the cell dissociation medium, which was comprised of DMEM/Ham’s F-12 (Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 125 U/mL collagenase type IV (Gibco), 2.5% FBS, 2 U/mL dispase II, 5 mM CaCl2, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich), and 10 nM Y-27632 dihydrochloride (Selleck Chemicals). After 1 h, the larger chunks of the tissue debris were removed by use of a 100 μm cell strainer (Corning). The collagenase and dispase activities within the filtrate containing the dissociated cells were neutralized by adding PBS (pH 7.4) that contains 5 mM EDTA (pH 8.0; Invitrogen). The dissociated cells within the filtrate were pelleted by centrifugation at 100 xg for 7 min at 4 °C, and resuspended in ice cold, EDTA-free PBS (pH 7.4). The epithelial cells within the cell suspension were enriched using a 70 μm cell strainer (Corning). The epithelial cells within the filtrates that passed through the strainer were pelleted by centrifugation at 100 xg for 7 min at 4 °C, and then resuspended in the cul ture medium consisting of DMEM/Ham’s F-12 supplemented with 2.5% FBS, 125 mg/mL amphotericin B, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM NAC (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich), plus 1% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS) cocktail and 10 μg/mL mouse derived epidermal growth factor (EGF) (both purchased from Gemini Bio-Products), 10 nM Y-27632 dichloride (Selleck Chemicals), and then seeded in 24-well plates (2 × 104 cells/mL) that were pre-coated with 2% Matrigel (prepared as indicated within the manufacturer’s instruction manual; Corning Life Sciences). Using immunofluorescence microscopy, epithelial cells were identified by positive staining for ZO-1 (tight junction marker, Thermo Fisher Scientific), E-cadherin (adherins junctions, Sigma-Aldrich), cytokeratin 18 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), as well as negative staining for both Vimentin (mesenchymal marker, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and Smooth Muscle Actin (endothelial/fibroblast marker, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Preparation of stomach sections from mice

Stomachs from 6–19 weeks old mice (C57BL/6J) were collected by necropsy and prepared for sectioning as described above in “Preparation of primary gastric epithelial cells from mice”. After cutting the stomach along the lesser curvature, the tissue was further cut into a rectangular shape by trimming the lesser curvature side. The remaining stomach tissue was rinsed thoroughly with ice cold PBS (pH 7.4), and transferred into mounting agarose (6% low gelling temperature agarose, Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 40% glycerol, and pre-cooled to 37 °C. Immediately after embedding, the stomachs were maintained at 4 °C until ready fo r sectioning. 350 μm tissue cross-sections were prepared using a vibratome (VT 1000S, frequency unit: 10, feed unit: 400, speed unit: 3.5, Leica), and each section was placed onto a transwell membrane insert (MilliCell, pore size, 0.4 μm, Thermo Fisher) in a 6-well plate with each well containing 1 mL culture medium consisting of DMEM/Ham’s F-12 supplemented with 2.5% FBS, 125 mg/mL amphotericin B, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 2 mM NAC (all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich), plus 1% Insulin-Transferrin-Selenium (ITS) cocktail and 10 μg/mL mouse derived epidermal growth factor (EGF) (both purchased from Gemini Bio-Products), 10 nM Y-27632 dichloride (Selleck Chemicals). The sections were maintained at 37 °C and under an oxygen-enriched co ndition (95% O2, 5% CO2) for 30 min prior to each experiment. Tissue sections prepared in this manner were evaluated using fluorescence microscopy for viability and metabolic activities. Tissue sections were consistently confirmed to be negative for cell death markers (TUNEL staining, and, ethidium homodimer-1 staining, both purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific), positive for viability markers (CellTracker green staining, and, calcein-AM staining, both purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific), and, positive for metabolic activity (MTS assay, Promega).

METHOD DETAILS

Immunoblot analyses

Cell lysates were prepared by incubating monolayers at 4 °C in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 100 uM Na3VO4, 25 mM NAF, 25 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 2 mM EGTA, 2 mM EDTA, 0.3% Triton X-100, all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich) that was supplemented with complete Mini EDTA-free, protease inhibitor cocktail tablets (1 tablet/25 mL, Roche Diagnostics). After 10 min, the lysates were transferred to fresh tubes and mixed with an equivalent volume of 2x sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer (100 mM, SDS Tris, pH 6.8, 4%, bromophenol blue, 0.2% glycerol, 20% 2-mercaptoethanol, all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich), and then incubated at 100 °C for 10 min. After SDS-PAGE, the gel proteins were electro-transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane (Millipore). Transfer membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer (Tris-buffered (pH 7.4) saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T, Sigma-Aldrich) supplemented with 5% skim milk (Lab Scientific). The blots were briefly washed with TBS-T for 5 min, and then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling) diluted in the blocking buffer. After washing 4 times with TBS-T for 5 min each, the blots were incubated with HRP substrates (SuperSignal West, Pico and Femto mixed at 1:1 ratio; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The luminescent signals from the blots were imaged using a ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system (Bio-Rad), and, analyzed using Image Lab software (Version 4.1; Bio-Rad) to quantify the relative band intensities.

Measurement of mTOR activities

The relative mTORC1 activity within whole cell lysates was determined by immunoblot analysis using p-S6K (T389) antibodies (1:3000 dilution, Cell Signaling), or S6K antibodies (1:2000 dilution, Cell Signaling), calculated by the intensity of the immuno-specific signal corresponding to p-S6K divided by the intensity of the band corresponding to total S6K. The relative mTORC2 activity was measured by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for protein B kinase (Akt) phosphorylated at Serine 473 or p-Akt (1:10000 dilution, Cell Signaling), or total Akt (1:10000 dilution, Cell Signaling), calculated by dividing the intensity of the immuno-specific signal corresponding to p-Akt by the intensity of the band corresponding to total Akt.

Preparation of Hp culture filtrate

Hp culture filtrate (HPCF) was prepared from cultivation of Hp 60190 as previously described (Jain et al., 2011). Briefly, Hp were inoculated in 4 mL BSFB broth onto the surface of 2% agar plates made of Ham’s F-12 media supplemented with 5% FBS. The biphasic cultures were incubated at 37 °C within a humidified, microaerophilic environment (10% O2, 5% CO2). After 1–2 days, the liquid phase of the biphasic culture was transferred to a fresh BSFB liquid culture (300 mL) and incubated with shaking at 37 °C with 5% CO 2. After 2 days, the cultures were centrifuged at 5000 xg for 30 min, and the VacA in the supernatant was precipitated out of solution by dissolving ammonium sulfate (Fisher Scientific) to 90% saturation (662 g/L) at 4 °C with stirring. After 4 h, the precipitated material was collected by centrifugation at 5000 xg at 4 °C. The pelleted material was dissolved in wash buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, pH 7.0; Sigma-Aldrich) and dialyzed at 4 °C for 12 h (with four buffer changes) in the wash buffer (100 times the volume of the precipitate solution), using 50 kDa molecular weight cutoff (MWCO) dialysis tubing (Spectra/Por 6 RC, Spectrum Labs). After pelleting the insoluble fractions by centrifugation at 5000 xg for 30 min, followed by filtration using a 0.22 μm MWCO filtration funnel (Stericup, EMD Millipore), the supernatant was concentrated using a 10 kDa, MWCO centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra, Merck Millipore), and then dialyzed for 12 h at 4 °C in PBS pH 7.4 with stirring, using a 10 kDa MWCO dialysis cassette (Slide-A-Lyzer, Thermo Fisher Scientific). During dialysis, the dialysis buffer (PBS pH 7.4, at 100 times the volume of the concentrate) was changed three times. The total protein concentration was measured using the BCA assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The presence of VacA within HPCF was confirmed by immunoblot analysis using rabbit VacA antiserum (generated at the University of Illinois).

Inactivation of VacA

The VacA within HPCF, or, within purified VacA preparations was heat-inactivated by boiling at 100 °C for 10 min, or, removed by incuba ting for 1 h at 4 °C with Protein A magnetic beads (Cell Signaling), which were pre-incubated for overnight at 4 °C with rabbit VacA antiserum (generated at the University of Illinois), or rabbit Campylobacter jejuni cytolethal distending toxin A (CdtA) antiserum (custom ordered; Rockland Immunochemicals).

Purification and Acid-activation of VacA

After removing the insoluble fractions as described above under “Preparation of Hp culture filtrate (HPCF)”, the VacA-containing soluble fraction was loaded into a column packed with anion exchange resin (DEAE Sephacel, GE Healthcare) that had been pre-equilibrated with wash buffer (10 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, pH 7.0). After washing the column with 3 bed volumes of wash buffer, VacA was eluted with wash buffer supplemented with 0.2 M NaCl, and collected in 1 mL fractions. After evaluating the purity of VacA within the fractions by SDS-PAGE gel separation and staining with G-250 Coomassie Brilliant Blue (Sigma-Aldrich), the fractions containing VacA with no additional visible bands were combined and concentrated using a 10 kDa MWCO centrifugal filter (Amicon Ultra, Millipore), and then dialyzed for 12 h at 4 °C in PBS pH 7.4 (at 100 times the volume of the concentrate) with stirring using a 10 kDa MWCO dialysis cassette (Slide-A-Lyzer). The concentration of purified VacA was determined by the Bradford or BCA assay (both from Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Just prior to addition to cultured host cells or tissue, VacA was activated by mixing 10% (v/v) HCl (0.3 M) to purified toxin, and then incubating at 37 °C. After 30 min, the solution was neutralized by adding NaOH (0.3 M) at an equivalent volume as the HCl added.

Autophagy activation

Autophagy activation within whole cell lysates was evaluated by immunoblot analysis, using LC3 antibodies (1:10000 dilution, Cell Signaling), or β-actin (1:5000 dilution, Cell Signaling), calculated by the intensity of the immuno-specific signal corresponding to LC3-II normalized by the intensity of the band corresponding to β-actin.

Immunostaining of tissue section specimens

After each experiment, the tissue sections were fixed overnight at 4 °C with PBS (pH 7.4) buffered formalin (4%), and then incubated in PBS (pH 7.4) buffered 30% sucrose until sucrose pervaded the entire tissue section, which was indicated when the fixed tissues floating on the buffer surface started to sink down in the buffer. The tissues were then mounted in a mold containing Optimum Cutting Temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetek USA), and snap-frozen by incubating the mold for 3 min in isopentane (Sigma Aldrich) that had been pre-chilled with dry ice. The frozen blocks were sectioned into 10 μm sections using a cryostat (CM3050S, Leica) and placed on glass slides.

For immunostaining, the OCT compound was first removed by washing slices once with PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 min with gentle shaking, and then slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies (p-S6K an d LC3; 1:200 dilution, Cell Signaling) (p-GCN2; 1:200 dilution, Abcam) diluted in blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum (Cell Signaling) in Tris-buffered (pH 7.4) saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (TBS-T). After washing the slides with PBS (pH 7.4) for 5 min, the slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the goat anti-Rabbit Alexa 488 Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400 dilution, Invitrogen) diluted in the blocking buffer containing counter staining dyes (1 μM DAPI, 5 μM wheat germ agglutinin (WGA), both purchased from Invitrogen). After washing 3 times with PBS (pH 7.4), for 10 min each wash, samples were mounted using Prolong Gold Antifade Mounting Reagent (Invitrogen). The sections were observed using a laser scanning confocal microscope (LSM 700, Carl Zeiss Microscopy) with either a 10X objective (EC Plan-Neofluar, NA; 0.3, Carl Zeiss Microscopy) or a 40X objective (EC Plan-Neofluar, NA; 1.3, Carl Zeiss Microscopy), and imaged using a digital microscope camera (Axio Imager Z1, 512× 512 pixels, Carl Zeiss Microscopy). The images were processed and analyzed using ZEN 2012 software (Version 1.1.2., Carl Zeiss Microscopy).

Overexpression of mTOR constructs

Cells overexpressing mTOR constructs were prepared as described previously (Ohne et al., 2008). Using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), cells were transiently transfected, as indicated within the manufacturer’s instruction manual, with the pIRES-puro3 plasmid encoding Flag-wild type mTOR, or, Flag-mTOR SL+LT1, the hyperactive mTOR mutant (Ohne et al., 2008). After overnight incubation, the cells that had been transfected were selected by incubating at 37 °C and under a humidified environment in the presence of 2 μg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich), which kills cells not transfected with pIRES-puro3 plasmid, and therefore not expressing active puromycin-N-acetyl-transferase. After 24 h, the cells were incubated in the absence of puromycin for 4 h before commencing specific experiments. Overexpression of the Flag-mTOR constructs was confirmed by immunoblot analysis for the Flag motif, using an anti-Flag antibody (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling).

Measurement of mTORC1 mediated phosphorylation of Ulk1

The specific mTORC1 activity corresponding to phosphorylation of Ulk1 at Ser757 was measured by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for Ulk1 at Serine 757 (p-Ulk1, 1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling), or total Ulk1 (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling), calculated by the intensity of the band corresponding to p-Ulk1 divided by the intensity of the band corresponding to total Ulk1.

Inhibition of Ulk1 activities

Ulk1 kinase activity was inhibited using the ULK1 specific inhibitor (SBI-0206965, Cayman Chemical). Cells were pre-incubated in the absence or presence of 50 μM SBI-0206965, at 37 °C in DMEM with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment for 30 min, and then further incubated at 37 °C in DMEM with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM) for 4 h.

Amino acid deprivation of mammalian cells

Cells were briefly washed with PBS pH 7.4 and incubated in pre-warmed amino acid depleted medium, which is comprised of the custom formulated DMEM, not containing any amino acids (Hyclone), supplemented with dialyzed 10% FBS (Gibco) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich).

Measurement of co-localization between mTORC1 and lysosomal compartments

Mammalian cells, that were seeded in 8-well chamber slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific), were incubated in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM) in DMEM for 4 h, or in amino acid depleted medium (as defined under “Amino acid deprivation of mammalian cells”) for 1 h, at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment. After incubation, the cells were prepared for microscopy analysis as described previously (Zoncu et al., 2011). Briefly, the cells were fixed for 20 min in PBS (pH 7.4) buffered 4% formaldehyde (Fisher Scientific), and the membrane permeability increased by incubating the monolayers for 10 min in PBS (pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). Cellular mTOR and LAMP-1 were detected using immunofluorescence by incubating the cells at 4 °C with rabbit anti-mT OR antibody (1:500 dilution; Cell Signaling) and mouse anti-LAMP-1 (1:100 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), both diluted in blocking buffer (PBS (pH 7.4) containing 1% BSA (Sigma-Aldrich). After an overnight incubation, the monolayers were briefly rinsed with the blocking buffer once and then incubated in the dark and at room temperature with goat Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (1:500 dilution, Invitrogen), goat Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse antibody, (1:500 dilution, Invitrogen) and 50 nM DAPI, all diluted in the blocking buffer. After 30 min, the cells were washed 3 times (5 min each) with PBS pH 7.4 and were mounted on slides, using a mounting reagent (Prolong Gold Antifade, Invitrogen), with a coverslip. The cells were observed using a LSM 700 laser scanning confocal microscope with a 63X objective (Apochromat, NA; 1.42, Carl Zeiss Microscopy), and, imaged using an Axio Imager Z1digital microscope camera (512 × 512 pixels). The images were processed and analyzed using ZEN 2012 software, Version 1.1.2.

Tethering of mTORC1 to lysosomal membranes

Cells were stably transfected with lentiviral particles prepared as described previously (Yoon et al., 2015), packaged with either pLJM1 encoding Flag-Raptor (Flag tagged wild type Raptor, Addgene), or, Flag-Raptor-Rheb15 (Flag tagged chimeric Raptor fused with the lysosomal transmembrane motif of Rheb, which tethers the coupled mTORC1 to lysosomal membranes, Addgene) (Sancak et al., 2010), both of which were originally deposited at Addgene by Dr. David M. Sabatini. After 2 days, the successfully transfected cells were selected by incubating in the presence of puromycin (2 μg/mL), which kills cells not expressing active puromycin-N-acetyl-transferase, a selection marker that was encoded along with the Raptor construct within the pLJM1 vector and packaged together within the lentiviral particles. The overexpression of the Flag-Raptor constructs was confirmed by immunoblot analysis for the Flag motif within the whole cell lysates, using anti-Flag antibody (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling).

Inhibiting de novo protein synthesis

Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of VacA (250 nM) in DMEM for 3.5 h, or in the amino acid depleted medium (as defined under “Amino acid deprivation of mammalian cells”) for 30 min, at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment. After each incubation, cells were further incubated in the absence or presence of 10 μM cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich) at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment in the same medium for 30 min.

Measuring GCN2 dependent cellular sensing of relative intracellular amino acid deficiency

The GCN2 dependent cellular sensing of relative intracellular amino acid levels within whole cell lysates was measured by immunoblot analysis using antibodies specific for GCN2 phosphorylated at Thr 898 (p-GCN2, 1:1000 dilution; Abcam), or, total GCN2 (1:5000 dilution; Cell Signaling), calculated by the intensity of the band corresponding to p-GCN2, divided by the intensity of the band corresponding to total GCN2.

Use of L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester for inhibiting VacA dependent inhibition of mTORC1 signaling activity

Cells were incubated in the presence or absence of VacA (250 nM), at 37 °C in DMEM for 3.5 h, or in the amino acid depleted medium (as defined under “Amino acid deprivation of mammalian cells”) for 30 min, at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment. After each incubation, cells were further incubated in the absence or presence of L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester or LLOMe (0.5 mM; Cayman Chemical) at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in a humidified environment in the same medium for 30 min.

Measurement of relative levels of intracellular amino acids

Monolayers of HEK293T cells seeded in 6 cm plates were incubated in a humidified environment at 37 °C with 5% CO 2 in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM). After 4 h, the cells were immediately chilled on ice, thoroughly washed with ice cold PBS pH 7.4 twice, and collected in 300 μL of ice-cold 60 % methanol using a cell scraper. The intracellular compartments were further disrupted by sonication (Thermo Fisher, 20 % power, 5 repeats of 1 sec pulses, using 3 sec intervals). A small fraction of each sample was reserved for immunoblot analyses. The cellular debris were removed by centrifuging the cell suspension at 12,000 xg at 4 °C for 15 min, yielding a clear supernatant, which was transferred to a fresh Eppendorf tube. The samples were kept at − 80 °C until submitted to the Metabolomics Cent er at the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center (University of Illinois) for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analyses designed for quantitatively measuring amino acids. As a control, samples were harvested using the same methodology from cells that were incubated for 5 min on ice in PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with 50 μg/mL digitonin (a reagent that selectively permeabilizes plasma membrane at the indicated dose, Sigma), and, confirmed to be negative in the amino acid levels. The relative levels of intracellular amino acids from different cell samples were normalized by the intensity of immune specific-bands corresponding to Histone H3 (1: 1000 dilution, Cell Signaling).

Inhibiting VacA-dependent mitochondrial fragmentation with mdivi-1

Cells were pre-incubated at 37 °C in DMEM and under 5% CO2 within a humidified environment in the absence or presence of 200 μM mdivi-1 (EMD Millipore). After 30 min, and cells were then further incubated at 37 °C in DMEM, and under 5% CO2 within a humidified environment, for 4 h in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM).

Ectopic overexpression of the p34 subunit of VacA

Monolayers of cells were transiently co-transfected with plasmids harboring the genes encoding p34-GFP (pEGFP-C1::p34) (Galmiche et al., 2000), GFP alone (pAc-GFP-N1), or the pCDNA3.1 vector (transfection control for a mock overexpression), along with a plasmid harboring the gene encoding Myc-tagged S6K1 (pCDNA-Myc-S6K1) (at 4:1 ratio), using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher). After 24 h, the relative cellular levels of mTORC1 were determined by immunoblot analysis using p-S6K (T389) antibodies (1:3000 dilution, Cell Signaling), or Myc antibodies (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling), calculated by dividing the intensities of the immune-specific signals corresponding to p-Myc-S6K (distinguishable from p-endogenous S6K by size) by the intensity of the immune-specific signals corresponding to Myc.

Evaluating VacA-dependent cellular vacuolation

The VacA dependent cellular vacuolation was evaluated by incubating cells at 37 °C and under 5% CO2 within a humidified environment in the absence or presence of VacA (250 nM) in DMEM and NH4Cl (5 mM). After 4 h, cellular vacuolation was visualized using phase contrast microscopy (Thermo Fisher, EVOS FL)). Otherwise indicated, all the Hp infection and VacA intoxication studies were carried out using culture medium not supplemented with NH4Cl. In indicated experiments, the cells were pre-incubated for 30 min at 37 °C and under 5% CO 2 within a humidified environment in the absence or presence of Bafilomycin A1 (10 nM, Sigma-Aldrich), and then further incubated in the absence or presence of VacA.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

As indicated in the figure legends, each experiment was performed independently at least three times. For each experiment using samples collected from mice, a whole experimental set used for different treatments was harvested from a single animal. Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (ver. 7.0). Error bars indicated standard deviations. P values were calculated using either the Students’ t test with paired, two-tailed distribution, or, one-way ANOVA, corrected using either the Dunnett’s, or, the Tukey’s test. P values smaller than 0.05 were considered statistically significant (a = 0.05).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Helicobacter pylori inhibit mTORC1 signaling activity by a VacA-dependent mechanism

Mitochondrial targeting by VacA disrupts amino acid homeostasis sensed by mTORC1

VacA intoxication drives mTORC1 dissociation from lysosomes into an inactive complex

Inhibition of mTORC1 activates autophagy through the Ulk-1 protein kinase complex

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Core Facilities at the Carl R. Woese Institute for Genomic Biology the Metabolomics Center at the Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Karen Guillemin and Timothy L. Cover for Hp strains, Joachim Rassow for the GFP constructs, and David M. Sabatini for the Raptor constructs. This project was financially supported by NIH (AI045928, AI117497 to S.R.B., GM089771 to J.C.), the Clark Fellowship to I.K. (UIUC, Microbiology), and JSPS KAKENHI (25291042 and 17H03802 to T.M.).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

I.K. conducted the majority of experiments and wrote the manuscript with S.R.B. J.L. optimized and conducted experiments for Fig. 2C, 2E, and S6B. S.J.O. optimized experiments for Fig. 2B and 2D. Invaluable materials and consultation were provided by M.Y. and J.C. for Fig. 5, S.J and H.J.C for Fig. 2C, 2E, and S6B, and T.M. for Fig. 3. R.L.H and M.L.R. contributed to animal husbandry and sample collection for Fig. 2B through 2E and S6B. M.N.H. contributed to purification and quality control of VacA, which were essential for Fig. 2 through 7. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- ARNOULT D, CARNEIRO L, TATTOLI I, GIRARDIN SE. The role of mitochondria in cellular defense against microbial infection. Semin Immunol. 2009;21:223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2009.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ATHERTON JC, CAO P, PEEK RM, JR, TUMMURU MK, BLASER MJ, COVER TL. Mosaicism in vacuolating cytotoxin alleles of Helicobacter pylori. Association of specific vacA types with cytotoxin production and peptic ulceration. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17771–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLANKE SR. Micro-managing the executioner: pathogen targeting of mitochondria. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13:64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CALORE F, GENISSET C, CASELLATO A, ROSSATO M, CODOLO G, ESPOSTI MD, SCORRANO L, DE BERNARD M. Endosome-mitochondria juxtaposition during apoptosis induced by H. pylori VacA. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:1707–16. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CANALES J, VALENZUELA M, BRAVO J, CERDA-OPAZO P, JORQUERA C, TOLEDO H, BRAVO D, QUEST AF. Helicobacter pylori Induced Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH Kinase/mTOR Activation Increases Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1alpha to Promote Loss of Cyclin D1 and G0/G1 Cell Cycle Arrest in Human Gastric Cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:92. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAKRABARTI S, LIEHL P, BUCHON N, LEMAITRE B. Infection-induced host translational blockage inhibits immune responses and epithelial renewal in the Drosophila gut. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVER TL, BLANKE SR. Helicobacter pylori VacA, a paradigm for toxin multifunctionality. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2005;3:320–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVER TL, BLASER MJ. Purification and characterization of the vacuolating toxin from Helicobacter pylori. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10570–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE LEON JA, QIU J, NICOLAI CJ, COUNIHAN JL, BARRY KC, XU L, LAWRENCE RE, CASTELLANO BM, ZONCU R, NOMURA DK, et al. Positive and Negative Regulation of the Master Metabolic Regulator mTORC1 by Two Families of Legionella pneumophila Effectors. Cell Rep. 2017;21:2031–2038. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.10.088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DERETIC V, LEVINE B. Autophagy, immunity, and microbial adaptations. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:527–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEVER TE, HINNEBUSCH AG. GCN2 whets the appetite for amino acids. Mol Cell. 2005;18:141–2. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIBBLE CC, MANNING BD. Signal integration by mTORC1 coordinates nutrient input with biosynthetic output. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:555–64. doi: 10.1038/ncb2763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EGAN DF, CHUN MG, VAMOS M, ZOU H, RONG J, MILLER CJ, LOU HJ, RAVEENDRA-PANICKAR D, YANG CC, SHEFFLER DJ, et al. Small Molecule Inhibition of the Autophagy Kinase ULK1 and Identification of ULK1 Substrates. Mol Cell. 2015;59:285–97. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EISENREICH W, HEESEMANN J, RUDEL T, GOEBEL W. Metabolic host responses to infection by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2013;3:24. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GALMICHE A, RASSOW J, DOYE A, CAGNOL S, CHAMBARD JC, CONTAMIN S, DE THILLOT V, JUST I, RICCI V, SOLCIA E, et al. The N-terminal 34 kDa fragment of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin targets mitochondria and induces cytochrome c release. EMBO J. 2000;19:6361–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA VR, PATEL HK, KOSTOLANSKY SS, BALLIVIAN RA, EICHBERG J, BLANKE SR. Sphingomyelin functions as a novel receptor for Helicobacter pylori VacA. PLoS pathogens. 2008;4:e1000073. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUPTA VR, WILSON BA, BLANKE SR. Sphingomyelin is important for the cellular entry and intracellular localization of Helicobacter pylori VacA. Cell Microbiol. 2010;12:1517–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAY N, SONENBERG N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–45. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HSU PP, KANG SA, RAMESEDER J, ZHANG Y, OTTINA KA, LIM D, PETERSON TR, CHOI Y, GRAY NS, YAFFE MB, et al. The mTOR-regulated phosphoproteome reveals a mechanism of mTORC1-mediated inhibition of growth factor signaling. Science. 2011;332:1317–22. doi: 10.1126/science.1199498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HYDE R, TAYLOR PM, HUNDAL HS. Amino acid transporters: roles in amino acid sensing and signalling in animal cells. Biochem J. 2003;373:1–18. doi: 10.1042/bj20030405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- INOKI K, KIM J, GUAN KL. AMPK and mTOR in cellular energy homeostasis and drug targets. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;52:381–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010611-134537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAIN P, LUO ZQ, BLANKE SR. Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin A (VacA) engages the mitochondrial fission machinery to induce host cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:16032–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105175108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JARAMILLO M, GOMEZ MA, LARSSON O, SHIO MT, TOPISIROVIC I, CONTRERAS I, LUXENBURG R, ROSENFELD A, COLINA R, MCMASTER RW, et al. Leishmania repression of host translation through mTOR cleavage is required for parasite survival and infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAUR J, DEBNATH J. Autophagy at the crossroads of catabolism and anabolism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2015;16:461–72. doi: 10.1038/nrm4024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM IJ, BLANKE SR. Remodeling the host environment: modulation of the gastric epithelium by the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating toxin (VacA) Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:37. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM J, KUNDU M, VIOLLET B, GUAN KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:132–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIMURA M, GOTO S, WADA A, YAHIRO K, NIIDOME T, HATAKEYAMA T, AOYAGI H, HIRAYAMA T, KONDO T. Vacuolating cytotoxin purified from Helicobacter pylori causes mitochondrial damage in human gastric cells. Microb Pathog. 1999;26:45–52. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1998.0241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLOFT N, NEUKIRCH C, BOBKIEWICZ W, VEERACHATO G, BUSCH T, VON HOVEN G, BOLLER K, HUSMANN M. Pro-autophagic signal induction by bacterial pore-forming toxins. Med Microbiol Immunol. 2010;199:299–309. doi: 10.1007/s00430-010-0163-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KO SH, RHO DA J, JEON JI, KIM YJ, WOO HA, KIM N, KIM JM. Crude Preparations of Helicobacter pylori Outer Membrane Vesicles Induce Upregulation of Heme Oxygenase-1 via Activating Akt-Nrf2 and mTOR-IκB Kinase-NF-κB Pathways in Dendritic Cells. Infect Immun. 2016;84:2162–74. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00190-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KOERFER J, KALLENDRUSCH S, MERZ F, WITTEKIND C, KUBICK C, KASSAHUN WT, SCHUMACHER G, MOEBIUS C, GASSLER N, SCHOPOW N, et al. Organotypic slice cultures of human gastric and esophagogastric junction cancer. Cancer Med. 2016;5:1444–53. doi: 10.1002/cam4.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KROEMER G, MARINO G, LEVINE B. Autophagy and the integrated stress response. Mol Cell. 2010;40:280–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAPLANTE M, SABATINI DM. mTOR signaling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:3589–94. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEUNK RD, JOHNSON PT, DAVID BC, KRAFT WG, MORGAN DR. Cytotoxic activity in broth-culture filtrates of Campylobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1988;26:93–9. doi: 10.1099/00222615-26-2-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE B, MIZUSHIMA N, VIRGIN HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–35. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI N, TANG B, JIA YP, ZHU P, ZHUANG Y, FANG Y, LI Q, WANG K, ZHANG WJ, GUO G, et al. Helicobacter pylori CagA Protein Negatively Regulates Autophagy and Promotes Inflammatory Response via c-Met-PI3K/Akt-mTOR Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:417. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LU R, HERRERA BB, ESHLEMAN HD, FU Y, BLOOM A, LI Z, SACKS DB, GOLDBERG MB. Shigella Effector OspB Activates mTORC1 in a Manner That Depends on IQGAP1 and Promotes Cell Proliferation. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MANIFAVA M, SMITH M, ROTONDO S, WALKER S, NIEWCZAS I, ZONCU R, CLARK J, KTISTAKIS NT. Dynamics of mTORC1 activation in response to amino acids. Elife. 2016:5. doi: 10.7554/eLife.19960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCCLAIN MS, CAO P, IWAMOTO H, VINION-DUBIEL AD, SZABO G, SHAO Z, COVER TL. A 12-amino-acid segment, present in type s2 but not type s1 Helicobacter pylori VacA proteins, abolishes cytotoxin activity and alters membrane channel formation. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:6499–508. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6499-6508.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHR I, SONENBERG N. Host translation at the nexus of infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:470–83. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]