Abstract

Introduction:

The main therapeutic intervention for sickle cell disease (SCD) is hydroxyurea (HU). The effect of HU is largely through dose-dependent induction of fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Poor HU adherence is common among adolescents.

Methods:

Our 6-month, two-site pilot intervention trial, “HABIT,” was led by culturally aligned community health workers (CHWs). CHWs performed support primarily through home visits, augmented by tailored text message reminders. Dyads of youth with SCD ages 10–18 years and a parent were enrolled. A customized HbF biomarker, the percentage decrease from each patients’ highest historical HU-induced HbF, “Personal best,” was used to qualify for enrollment and assess HU adherence. Two primary outcomes were as follows: (1) intervention feasibility and acceptability and (2) HU adherence measured in three ways: monthly percentage improvement toward HbF Personal best, proportion of days covered (PDC) by HU, and self-report.

Results:

Twenty-eight dyads were enrolled, of which 89% were retained. Feasibility and acceptability were excellent. Controlling for group assignment and month of intervention, the intervention group improved percentage decrease from Personal best by 2.3% per month during months 0–4 (P = 0.30), with similar improvement in adherence demonstrated using pharmacy records. Self-reported adherence did not correlate. Dyads viewed CHWs as supportive for learning about SCD and HU, living with SCD and making progress in coordinated self-management responsibility to support a daily HU habit. Most parents and youth appreciated text message HU reminders.

Conclusions:

The HABIT pilot intervention demonstrated feasibility and acceptability with promising effect toward improved medication adherence. Testing in a larger multisite intervention trial is warranted.

Keywords: hydroxyurea, medication adherence, self-management, sickle cell disease

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an inherited blood disease characterized by pain, fatigue, organ damage, and reduced quality of life (QOL).1,2 The disease primarily affects Americans of African descent, including Caribbean Latinos and other underserved communities.3,4 Offering hydroxyurea (HU), the sole FDA-approved treatment for SCD, for pediatric use is recommended as standard pediatric practice for patients with a severe phenotype.5 HU use in children with SCD reduces symptoms and improves QOL for two sickle subtypes, HbSS and HbS-B0 thalassemia.5 Effects of HU are largely through induction of a dose-dependent increase in fetal hemoglobin (HbF). Anti-inflammatory effects of HU also contribute to its clinical impact, such as reducing neutrophil count and inflammatory mediators.6,7

Despite its benefits, poor HU adherence in adolescents and young adults is common8–14 and can be associated with increased health-care utilization8 and reduced health QOL.14 Similar to medication use among underserved populations with other chronic conditions, barriers to adherence include cultural misalignment with medical staff15–18 and incomplete knowledge of drug benefit.12,15–17 Forgetting to take medication and lapses in teen self-efficacy are common self-reported patient barriers to adherence in chronic conditions.12,18–21 Adherence may be improved by integration of use into a daily medication habit.22 Improved adherence to HU through a developmentally appropriate self-managed habit may improve the health of youth with SCD.23

We describe a two-site randomized pilot intervention, HABIT, to improve HU adherence in a sample of youth with SCD. The study focused on patients with apparent suboptimal HU adherence, as measured by decreased HbF responses compared to previous levels on comparable HU doses. Transition of responsibility for self-management should occur during adolescence.24–26 Our intervention was led by culturally aligned community health workers (CHWs) and was loosely based on a previously successful pediatric asthma intervention.27,28 CHWs are an accepted mode of community-based support for improving health in underserved communities and have improved medical adherence among adults with other chronic conditions.28–32 Results of CHW-based patient support have not previously been reported in SCD or in CHW partnering with youth– parent dyads. Here, we assessed if study dyads would work with CHWs toward the goals of improved understanding of SCD and HU, identifying and addressing barriers to medication adherence, building youth– parent disease self-management partnerships, and identifying a cue on which a medication habit could be built. CHW support was augmented by tailored automated text message reminders that appeared as sent by the CHWs.

As no standard biomarker exists to assess HU adherence,9,11,13,33,34 we used the highest historical HU-induced HbF at stable HU dose, “Personal best,” as a target for an individualized self-management goal.35,36 In this context, clinic-based Personal best may be considered as comparable to study-based maximum tolerated dose. We have previously reported on the utility of this biomarker for tracking HU use in a retrospective sample of youth on HU therapy from these same two study sites. In that study, youth on stable HU doses were grouped as having stable or substantially decreased HbF from Personal best at a recent assessment. Reversing of other hematologic parameters affected by HU (e.g., hemoglobin, absolute neutrophil, and reticulocytes counts) and urgent hospital use over 1-year periods were found only in the group with greater decline from Personal best.36

Primary aims of this pilot study were to assess the following: (1) Feasibility and acceptability of the randomized intervention and (2) the effect size on adherence relative to controls using a composite of primary endpoints to estimate the necessary sample size needed to power an efficacy trial. As an adherence study, the non-intervention arm was designed as an attention control. An attention control arm in this pilot intervention study was used to reduce study bias and to approximate an effect size upon which sample size for a future efficacy trial could be estimated. The results of these aims are reported here.

2 |. METHODS

All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at each participating site. The study protocol has been described in detail elsewhere35 and is briefly summarized below.

Subjects:

Subjects 10–18 years of age and a parent (or legal guardian) were recruited from two pediatric sickle cell clinical sites, Columbia University Medical Center and Children’s Hospital at Montefiore, both in New York City. Subjects were enrolled as youth–parent dyads.

Eligible patients had a ≥10% decrease in their HbF from their Personal best HbF during clinical care based on the average of ≥3 HbF levels during the year prior to study enrollment.36 Additional eligibility criteria were as follows: youth with HbSS or HbS-B0 thalassemia prescribed HU ≥18 months, not cognitively impaired (defined as >1 level below expected grade due to school performance issues), and youth and parent were able to speak and read in English or Spanish and were willing to use a cell phone with text message capability. All HbF values were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography and recorded only if at >90 days from transfusions. Dyads meeting eligibility criteria provided consent and/or assent that included release of pharmacy records for the 1 year prior to study entry through the duration of study participation.35

Intervention:

Randomization with 2:1 allocation to the intervention by a computerized random number generator was used to gain maximum feedback about the 6-month HABIT intervention. Subjects were blinded to study hypotheses, although not to group allocation. Upon enrollment, intervention dyads were contacted by CHWs to schedule the first visit either at home or at a mutually agreeable alternate site per dyad preference. During the first 3 months, monthly or bimonthly CHW visits covered social issues, SCD and HU education, dyad perception of their medical and social needs, and identification of a preexisting habit upon which HU adherence could be fostered. During months 4–6, CHW visits were replaced by automated text messages sent to each dyad member tailored by language (Spanish or English), time of day, and medication reminder based on the identified habit. Through-out the intervention, CHWs and dyads were able to contact each other by telephone or text message, as needed.

At the start of the study, parental perspective on their child’s ill-ness was obtained using a questionnaire on use of urgent emergency department (ED) and hospitalizations covering 1 year prior to enrollment. Both study groups received two educational brochures about SCD and HU. These and all other study materials were revised by Columbia’s Health Literacy service to conform to the community’s health literacy standards. Study participation required 6 monthly clinic visits with their regular SCD providers for obtaining HbF levels and completing a set of scheduled questionnaires.

CHW training and supervision:

Both study CHWs had previously been trained on patient empowerment and community-led support. A 3-day group training session was held for the study CHWs, including 1 day of general refresher training focused issues, such as parental empowerment and CHW roles and responsibilities.29,35,37 Training days 2–3 by the study PIs (Green and Smaldone) included information about SCD and HU, working with dyads, intervention protocol and goals of each visit, and potential “red flag issues”, which required immediate communication with PIs.

Our partner community-based organization, Community League of the Heights (CLOTH), participated in designing the intervention, orienting study staff to CHW-led work, hiring and training the CHWs regarding collaboration with CLOTH, and referral to community resources. In addition, CLOTH offered assistance with access to local services as needed by subjects’ families. A brochure describing CLOTH programs was provided to all study dyads.

CHW supervision was held through weekly meetings with the study PIs. A mid-study meeting with CHW trainers (Matos and Hicks) refreshed CHW training. The HABIT operations manual contained CHW structured encounter forms, monthly schedules and objectives to guide family discussion, key messages to promote HU adherence and youth–parent self-management partnership, exemplars of cues for text messaging reminders, and information for families on SCD and HU to be reviewed with dyads. Intervention subjects lacking a personal mobile telephone were supplied with a low-cost phone during months 4–6 to enable receipt of text messages.

Primary outcome measurement:

HU adherence was measured in three ways: decrease from HbF Personal best at monthly intervals from months 0 to 6, prescription refill adherence measured by proportion of days covered (PDC), and a four-item-modified Morisky self-report scale.38 Each item is answered as yes or no. Scores can range from 0 to 4, with lower scores signifying higher adherence. A score of 0 was considered as indicating high adherence, a score of 1–2 to as moderate adherence, and a score of 3–4 as low adherence. Feasibility and acceptability was measured by subject retention, monthly postcard comments from intervention dyads, and evaluation surveys at study completion.

Decrease from HbF Personal best was measured as the proportional difference between current HbF assessment and HbF at Personal best [(Personal best − current HbF)/Personal best × 100]. For example, if a Personal best HbF was 25% and current HbF was 20%, then decrease from Personal best was 20%. Where the current HbF assessment was lower than Personal best, deviation was reported as a negative percentage (e.g. −20%); where current assessment was higher than Personal best, deviation is reported as a positive percentage.

Prescription refill adherence was measured as the PDC.39 The PDC calculation is based on prescription fill dates and days supplied for each prescription refill. The denominator for the PDC is the number of days between the first and last fill dates of the medication during the measurement period. PDC was calculated for the 12 months prior to study entry and for the 6 months of study participation.

At study completion, youth and parents completed a 5-point evaluation survey about usefulness of the educational materials, with responses ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” Intervention dyads were also asked about their perceptions regarding working with the CHW and utility of the text messages.

Data analysis:

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.3 (Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to profile outcome measures at each data collection point for the intervention and control groups. Baseline group characteristics and adherence measures were compared using chi-square, Fisher’s exact, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. Evaluation survey responses were dichotomized as strongly agree/agree and strongly disagree/disagree/not sure. A growth model,41 a type of linear mixed model with random intercepts and slopes, was used to examine the difference in trend of improvement to Personal best, controlling for group assignment and month of study.

3 |. RESULTS

Enrollment and retention:

Of 74 youth screened at two study sites, 48 met all inclusion/exclusion criteria. Of these, 28 dyads (58%) participated in the study (targeted 30 dyads). Subject attrition was 10.7% (two intervention dyads and one control dyad). Reasons for dyad attrition were incarceration (one youth), illicit drug activity (one youth), and study procedures perceived as too burdensome (one parent).

The multiethnic sample of 28 dyads was similar in most demographic characteristics (Table 1). On average, youth were 14.3 ± 2.6 years, 43% female and 50% Hispanic. The majority (64.3%) of parents was single and/or separated from a spouse, had a high school education or less (57%), and was employed full or part time (71.4%). Spanish language surveys were selected for use by 42% of parents and 25% of youth.

TABLE 1.

Subject demographics for subjects and their parents in the intervention and control groups

| Intervention group (n = 18) |

Control Group (n = 10) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | P values | |

| Recruitment site | 0.11 | ||||

| Columbia | 7 | 38.9 | 7 | 70.0 | |

| Montefiore | 11 | 61.1 | 3 | 30.0 | |

| Completion of surveys in Spanish | |||||

| Youth | 2 | 11.1 | 5 | 50.0 | 0.19 |

| Parent | 6 | 33.3 | 6 | 60.0 | 1.0 |

| Youth demographics | |||||

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 14.5 ± 2.7 | 13.9 ± 3.0 | 0.41 | ||

| Gender (female) | 8 | 44.4 | 4 | 40.0 | 1.0 |

| Race | 0.64 | ||||

| Black | 10 | 55.6 | 4 | 40 | |

| Other | 7 | 38.9 | 6 | 60 | |

| Latino | 8 | 44.4 | 6 | 60 | 0.43 |

| Born in the United States | 14 | 77.8 | 8 | 80.0 | 1.0 |

| Current grade level | 0.89 | ||||

| Grade 4–6 | 4 | 22.2 | 3 | 30.0 | |

| Grade 7–8 | 4 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | |

| Grade 9–11 | 10 | 55.6 | 4 | 40.0 | |

| Living with a parent | 17 | 94.4 | 9 | 90.0 | 1.0 |

| Mother is the primary caretaker | 16 | 88.9 | 9 | 90.0 | 1.0 |

| Others living in the home have SCD | 3 | 16.7 | 3 | 30.0 | 0.37 |

| Parent demographics | |||||

| Latino | 8 | 44.4 | 6 | 60.0 | 0.43 |

| Born in the United States | 3 | 16.7 | 2 | 20.0 | 1.0 |

| Marital status | 0.02 | ||||

| Married/living with spouse | 9 | 50.0 | 1 | 10.0 | |

| Married but living separately | 3 | 16.7 | 2 | 20.0 | |

| Single | 6 | 33.3 | 7 | 70.0 | |

| Education level | 0.31 | ||||

| High school or less | 11 | 61.1 | 5 | 50.0 | |

| Some college or graduate | 7 | 38.9 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Employment | 0.44 | ||||

| Full time (≥35 hr) | 10 | 55.6 | 3 | 30.0 | |

| Part time | 4 | 22.2 | 2 | 20.0 | |

| Unemployed or in school | 4 | 22.2 | 4 | 40.0 | |

| Clinicala | |||||

| One-year prestudy (self-report) | |||||

| Number with hospitalizations | 11 | 61.1 | 5 | 50.0 | 0.70 |

| Number with ED visits | 11 | 61.1 | 6 | 60.0 | 1.0 |

| Hospitalizations (mean ± SD) | 3.7 | 4.2 | 2.0 | 1.5 | 0.78 |

| ED visits (mean ± SD) | 4.4 | 5.0 | 2.2 | 1.6 | 0.40 |

Fischer’s exact test; ED, emergency department. Bold P value means statistical significance.

By parental self-report for the 1-year prestudy enrollment period, urgent hospital resource use was similar between the two groups: approximately 60% of each group reported having been hospitalized and having one or more ED visits (Table 1). Of those receiving urgent care, there was no difference by group in the numbers of admissions and ED visits.

Feasibility of the intervention:

Coordinators called parents the night before to remind them of study-based clinic visits, and none were missed. On average, CHWs met with dyads for the first time within 31 ± 19.5 days of enrollment, with shorter time for the second half of recruited intervention subjects. On average, CHWs completed 4.9 ± 0.9 study visits prior to initiation of text messaging component. Most CHW visits were scheduled during afternoons or evenings. Some meetings occurred on Saturdays to accommodate working parents. The majority of parents and youth (81%) found these times to be convenient. Visits usually lasted 1 hour, with longer visits (90 minutes) if pressing issues arose. Outside of scheduled visits, CHW communicated with dyad members by telephone and/or text message, depending on need, for example, for arranging visits, follow-up of referrals or dyad’s alerts about urgent medical or psychosocial issues.

Among the 16 intervention dyads who completed the study, 10 (62.5%) required at least one CHW referral for services. One dyad received three referrals. The most common referrals were for mental health services (n = 5) and housing (n = 5). Two youth required urgent referrals to their clinic-based social workers for serious depressive or behavioral symptoms.

3.1 |. HU adherence measures

Fetal hemoglobin:

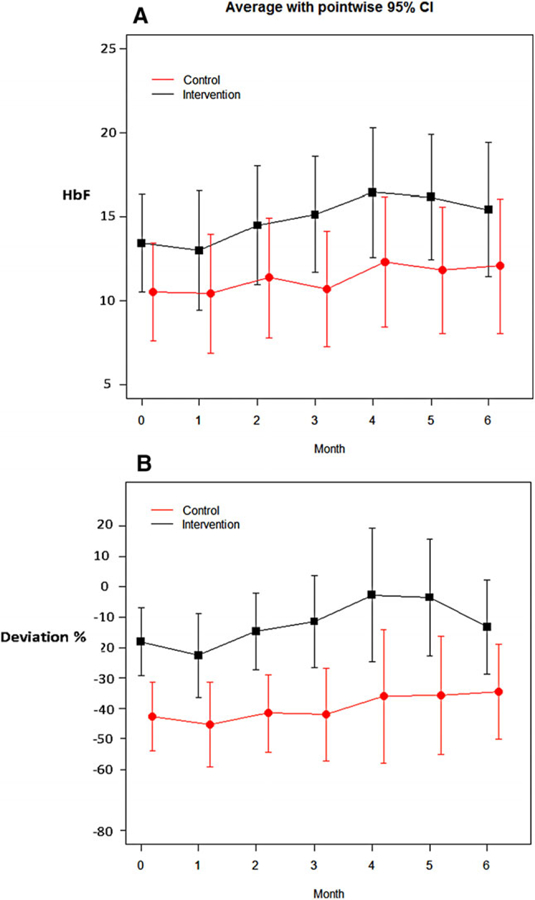

Personal best HbF was similar between the two study groups (P = 0.88) (Table 2). At study baseline, while mean HbF was similar (P = 0.25), there was less decrease from Personal best HbF in the intervention group compared to controls (−18.1 ± 23.6 vs. −42.6 ± 21.3, P = 0.009) (Table 2, Fig. 1). Controlling for intervention month and group assignment, the intervention group progressed to Personal best by 2.3% per month during months 0–4 (P = 0.30). Four (one control and three intervention) subjects who completed the study (16%) exceeded their Personal best HbF.

TABLE 2.

Measures of HbF during the intervention by the subject group

| HbF |

Percentage decrease from Personal best HbF |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HbF or decrease from Personal best | Intervention (n =18b) | Control (n =10) | P value | Intervention (n =18) | Control (n =10) | P value | P valuec |

| Historical Personal best HbF | 17.3 ± 7.7 | 16.6 ± 3.5 | 0.88 | ||||

| Study month: 0 | 13.4 ± 6.1 | 10.5 ± 5.2 | 0.25 | −18.1 ± 23.6 | −42.6 ± 21.3 | 0.009 | |

| 2 | 14.5 ± 7.0 | 11.4 ± 4.4 | 0.33 | −14.7 ± 24.9 | −40.8 ± 18.7 | 0.10 | 0.77 |

| 4 | 16.4 ± 7.4 | 12.3 ± 5.0 | 0.16 | −2.7 ± 41.8 | −34.3 ± 24.2 | 0.14 | 0.30 |

| 6 | 15.4 ± 7.6 | 12.1 ± 6.1 | 0.24 | −13.2 ± 29.7 | −32.9 ± 31.5 | 0.29 | 0.83 |

| Proportion of days covered (PDC)a | n = 18 | n = 8 | P value | ||||

| During year prestudy | 64.6 ± 32.6 | 79.2 ± 28.2 | 0.15 | ||||

| At study completion | 75.6 ± 20.7 | 82.9 ± 20.5 | 0.33 | ||||

For HbF values expressed as percent decreased from each patients’ Personal best HbF, a growth model, controlling for group assignment and time, was used to compare intervention patients to the controls. For HU proportion of days covered, values shown were derived from pharmacy refill data. Mean values are shown ± standard deviation.

For poststudy HU refill data, n = 14 for the intervention group.

For months 4 and 6, n = 16 for the intervention group and n = 9 for the control group.

Adjusting for study group and time. Bold P value means statistical significance.

FIGURE 1.

Primary trial outcomes using HbF and decreased HbF from Personal best: Changes to fetal hemoglobin (HbF) by absolute number (A) or by decrease from Personal best (B) in the intervention and control groups (black and red lines, respectively). HbF and decrease from Personal best HbF improved for the intervention compared to the control group. Dashed line in lower panel marks Personal best (no deviation) (shown as mean values with pointwise 95% confidence interval, by group)

Clinical data:

Parents reported the numbers of ED visits and hospitalizations for their child during the 1 year prior to study start (Table 1). During the study, five (20%) subjects (two control and three intervention) required red cell transfusions. Due to interference of transfused blood for 90 days with HbF measurement, each transfused subject missed one or more monthly HbF measurements (mean and median of 3) for the 6-month intervention (Table 2).

By the study group, blood count values that are sensitive to HU such as absolute neutrophil count were not different at Personal best, first (M0) and last (M6) study visits (Table 3). HU dose was significantly higher in the Intervention group at M0.

TABLE 3.

Blood count measurements at Personal best HbF, study initiation month 0 (M0), and at completion (M6) by the study group

| Parameters | At Personal best HbF |

Study month 0 |

Study month 6a |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention n = 18 |

Control n = 10 |

P value | Intervention n = 18 |

Control n = 10 |

P value | Intervention n = 16 |

Control n = 8 |

P valueb | |

| HU dose | 24.9 ± 4.8 | 23.8 ± 4.6 | 0.52 | 25.9 ± 3.9 | 21.7 ± 4.4 | 0.03 | 24.3 ± 7.6 | 22.5 ± 3.5 | 0.11 |

| Hb | 8.9 ± 1.6 | 9.1 ± 0.7 | 0.70 | 8.6 ± 1.3 | 9.3 ± 1.3 | 0.25 | 8.9 ± 1.2 | 9.5 ± 1.8 | 0.44 |

| MCV | 96.9 ± 11.7 | 101.1 ± 10.2 | 0.35 | 94.5 ± 13.0 | 86.8 ± 30.8 | 0.94 | 98.0 ± 11.3 | 89.0 ± 35.7 | 0.76 |

| ARC | 258 ± 181 | 204 ± 69 | 0.76 | 321 ± 183 | 307 ± 141 | 0.94 | 253 ± 133 | 248 ± 143 | 0.71 |

| WBC | 10.1 ± 3.8 | 9.1 ± 3.0 | 0.64 | 9.5 ± 2.8 | 10.5 ± 3.8 | 0.54 | 9.0 ± 2.7 | 7.9 ± 2.6 | 0.26 |

| ANC | 4.7 ± 2.0 | 4.7 ± 3.0 | 0.60 | 4.5 ± 1.9 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 0.59 | 3.2 ± 2.0 | 3.6 ± 1.5 | 0.71 |

| Platelets | 474 ± 338 | 439 ± 175 | 0.54 | 485 ± 262 | 350 ± 159 | 0.36 | 453 ± 248 | 438 ± 179 | 0.92 |

PB, Personal best HbF.

Intervention group: one withdrawal and one with multiple transfusions; Control group: two withdrawals.

Wilcoxon rank sum. Bold P value means statistical significance.

HU pharmacy refill:

Results were consistent with Personal best when adherence was measured using HU pharmacy refill data (Table 2). PDC for the year prior to study entry was 64.6 ± 32.6% and 79.4 ± 28.2% for the intervention and control groups, respectively (P = 0.15). At study completion, adherence modestly improved to 75.6 ± 20.7% (14.6%) and to 82.9 ± 20.5% (4.5%) for the intervention and control groups, respectively, with no significant difference between groups (P = 0.33).

Morisky self-reports of HU adherence:

Youth and parents in both groups uniformly reported low scores indicating good adherence. No significant differences were seen at month 0 for youth (1.6 ± 1.1 and 1.4 ± 1.1 for intervention and control groups, respectively) and their parents (0.7 ± 0.8 and 1.1 ± 1.4) and at month 6 for youth (1.1 ± 1.2 and 1.0 ± 1.1) and parents (0.6 ± 1.0 and 0.6 ± 0). Overall, 17.9% of youth and 10.7% of parents reported their adherence to HU as low. Scores were inconsistent with the two other methods used to assess HU adherence.

Text messaging:

Three parents and six youth required a mobile telephone for the texting (Table 4). Most youth did not have a regular time for taking HU. They required CHW coaching to identify a cue-based time to take their HU and for the text message reminder. Most dyads scheduled their tailored text messages to arrive during the evening (n = 11, 69%) or at subject bedtime (n = 4, 25%). All but one parent chose to receive their texts 15 or 30 min following their child’s message.

TABLE 4.

Subject views on the intervention by self-reporta

| Parents (n = 16) |

Youth (n = 16)b |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| CHW intervention | ||||

| Meeting times with CHWs were convenient | 13 | 81.2 | 13 | 81.2 |

| There were the right number of CHW visits | 12 | 75.0 | 13 | 81.2 |

| CHWs valued my opinion | 15 | 93.8 | 14 | 87.5 |

| I learned useful information about SCD from the CHW | 16 | 100 | 14 | 87.5 |

| I learned useful information about HU from the CHW | 16 | 100 | 13 | 81.2 |

| It was easy to talk about SCD with my CHW | 16 | 100 | 14 | 87.5 |

| Working with the CHWs made it easier to care for SCD | 16 | 100 | 13 | 80.0 |

| Working with the CHWs has helped my child (parent) and me work together better to take care of SCD | 14 | 87.5 | 11 | 73.3 |

| Choosing a time/event during the day made it easier to remember to take HU | 13 | 81.2 | 12 | 75.5 |

| Text messaging | ||||

| Subjects needing a mobile phone for texting | 3 | 19 | 6 | 38 |

| I like receiving text reminders every day | 13 | 81.2 | 9 | 56.3 |

| Receiving texts helped me to remember to take HU | 14 | 93.3 | 13 | 86.7 |

Numbers are reported as study subjects stating that they agreed or strongly agreed with these statements.

Some data are missing from one youth.

Acceptability of the intervention:

Nearly all parents (96%) and youth (80%) reported high levels of satisfaction with educational materials about SCD and HU and had learned new things from both brochures (Table 4). Dyad members liked the number of CHW visits, with one youth wanting more visits. Subjects reported that they felt the CHW valued their opinion. All parents and most of youth reported that the CHWs were easy to talk to about SCD and helped the dyad to cooperatively manage SCD. When asked about working with the CHWs, a typically positive parent remark was that “I like the way they were caring and not about work. They got into my life and helped me with that.” For youth, typical comments were “I like that the CHWs were friendly toward me and my parents” and that the intervention “gave me a better mindset.” Dyad members reported feeling better informed about HU benefits: “They answered all questions and help[ed] with our concerns” (parent) and “working with the CHWs … I learned new things, why I should take my HU” (youth). When asked what subjects disliked about working with CHWs, no parent had negative comments (e.g., “I liked everything.”). Only one youth stated that he/she did not like “the extra tube for blood.”

Parents liked receiving daily text message reminders more than youth (81.2 vs. 56.3%) (Table 4). Nonetheless, nearly all (93.3% of parents, 86.7% of youth) thought that the texts were helpful reminders for taking HU. A parent reported “I liked that the text was a set time every day and always on time”; a youth stated that the texts “reminded me every night to take my HU” and “I never forget my medication.” When dislikes about the texts were solicited, one youth stated that “some-times texts me at the wrong moment” and another that “I don’t like that they came mostly every day.”

4 |. DISCUSSION

The HABIT pilot trial demonstrated feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. Youth–parent dyads valued the intervention and were satisfied by the support provided for disease self-management and development of a daily HU habit. Obtaining pharmacy refill data for calculating HU PDC during the prestudy and intervention periods was feasible, despite multiple urban pharmacies. Moreover, the intervention effect on medication adherence, while not statistically significant, was promising as demonstrated by two objective measures: biomarker, controlling for group assignment and month of study, and pharmacy records.

While the study was not powered to demonstrate efficacy, the intervention group had reduced regression from the youth’s Personal best HBF, compared to the control group. Indeed, some youth receiving the intervention exceeded their Personal best goal, suggesting that HU adherence during the period of Personal best had been suboptimal. Within the context of a stable per weight HU dose, this outcome probably reflected longstanding challenges to HU adherence for these families. Encouraging subjects to reach their Personal best may have complemented coaching to develop a cue-based daily HU habit. Improved HbF peaked at completion of the CHW visits at month 4. This finding suggests that effective behavioral intervention for developing an HU habit may take more time than what was provided in this pilot intervention, and that text messaging alone in months 4–6 did not sustain the effect from CHW support.

Dyads in the intervention group appreciated that the CHWs provided personalized support. Most intervention dyads needed or requested referrals for mental health, housing, or other major issues. This finding suggests that pressing psychosocial issues and other unmet needs existed despite clinic-based resources.32 CHWs seemed to have provided an environment for dyads to address issues that can be barriers to maintaining adherence.

Dyads from both study groups reported having learned something new about SCD and HU from the education handouts. This finding suggested that information routinely conveyed by clinical providers may not be entirely effective in reaching youth and their parents. Effectively communicating fundamental health concepts may require culturally and linguistically aligned messengers and materials.32,42

Differences in deviation from HbF between study groups occurred despite randomization, especially in subject deviation from Personal best at month 0. If or how these differences may have impacted the study results are uncertain. Perhaps youth starting at lower HbF levels may have been more resistant to changes in adherence. Planning for an efficacy trial will allow for subgroup analyses, for example, by study site.

Adolescence is a critical time to improve adherence as preparation for the transition to chronic disease self-management.24,43–46 Our retrospective assessment of youth from these two clinical sites suggested that a large proportion had suboptimal HU adherence.36 The HABIT intervention focused on HU adherence through structured but tailored interactions with CHWs, supplemented by customized text message reminders, and encouraged developmentally appropriate youth–parent partnerships for self-management. Intervention trials to improve adherence among underserved children with chronic illness reinforce the importance of community-based support.28 Adolescents with SCD have previously accepted daily text reminders aimed to improve HU adherence.47,48

Trials to improve HU adherence are limited and, to date, have focused largely on HbF levels42 Here, we utilize outcomes of HbF, self-reported formation of a daily medication habit, and parent–child cooperative self-management. The use of dyad report of the Morisky scale for adherence was found to be inconsistent with objective biomarker and pharmacy refill data, a finding that is generally consistent with self-reported adherence.11,49

Study limitations included the modest sample size that limited statistical power and ability to examine specific factors associated with response to the intervention, as well as differences between study groups despite randomization. Study arm assignment could not be blinded. HU dose adjustments were not standardized during the study, although few minor changes were made for subject weight at both study sites. Monthly clinic visits were more frequent than the standard of visits every 2–3 months for patients on HU. Potential effects on adherence would be applicable to subjects in both study arms. As HbF induction with HU can take several months to occur, the 6-month pilot intervention may have been too brief to assess the full impact of improved adherence on HbF, blood count parameters or on health, or for testing sustainability of improved outcome measures. At the same time, modest study size may have contributed to inadequate power for detecting incremental changes in biomarkers, including HbF, mean red cell volume or absolute neutrophil count. Mobile phones were provided to several of the youth receiving the intervention, which may be a potential confounder in assessing adherence. Parental report of their child’s urgent hospital use prestudy was not validated.

In summary, this pilot trial demonstrated feasibility and accept-ability of the HABIT intervention, with promising effect toward improved medication adherence. Testing efficacy and sustainability in a larger multisite intervention trial is warranted. Design of an efficacy trial should take into account the impact of duration and intensity of the intervention on subject recruitment. Identifying successful interventions to support adherence to HU through developmentally appropriate self-management have the potential to improve the health of youth with SCD. Given that HU adherence is a widespread problem among adolescents, investment in structured support through CHWs may be worthwhile to share the responsibilities with clinic-based staff for youth–parent education, support, and social services.32

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by NIH R21NR013745 (Green and Smal-done, Principal Investigators) and the Irving Institute for Clinical-Translational Science (5ULTR000040-09).

Funding Information

Grant sponsor: NIH; Grant number: R21NR013745; Grant sponsor: NIH to the Irving Institute for Clinical-Translational Science; Grant number: 5ULTR000040-09.

Abbreviations:

- CHW

community health worker

- CLOTH

Community League of the Heights

- ED

emergency department

- HbF

fetal hemoglobin

- HU

hydroxyurea

- PDC

proportion of days covered

- QOL

quality of life

- SCD

sickle cell disease

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raphael JL, Mei M, Mueller BU, Giordano T. High resource hospitalizations among children with vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;58:584–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(Suppl):S512–S521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brousseau DC, Panepinto JA, Nimmer M, Hoffmann RG. The number of people with sickle-cell disease in the United States: national and state estimates. Am J Hematol 2010;85:77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yawn BP, Buchanan GR, Afenyi-Annan AN, et al. Management of sickle cell disease: summary of the 2014 evidence-based report by expert panel members. JAMA 2014;312:1033–1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Segal JB, Strouse JJ, Beach MC, et al. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell disease. Evid Rep Technol Assess 2008:1–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Ikuta T, Adekile AD, Gutsaeva DR, et al. The proinflammatory cytokine GM-CSF downregulates fetal hemoglobin expression by attenuating the cAMP-dependent pathway in sickle cell disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis 2011;47:235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Candrilli SD, O’Brien SH, Ware RE, Nahata MC, Seiber EE, Balkrishnan R. Hydroxyurea adherence and associated outcomes among Medicaid enrollees with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2011;86:273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brandow AM, Panepinto JA. Monitoring toxicity, impact, and adherence of hydroxyurea in children with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2011;86:804–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritho J, Liu H, Hartzema AG, Lottenberg R. Hydroxyurea use in patients with sickle cell disease in a Medicaid population. Am JHematol 2011;86:888–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thornburg CD, Calatroni A, Telen M, Kemper AR. Adherence to hydroxyurea therapy in children with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr 2010;156:415–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Walsh KE, Cutrona SL, Kavanagh PL, et al. Medication adherence among pediatric patients with sickle cell disease: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2014;134:1175–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drotar D Treatment adherence in patients with sickle cell anemia. J Pediatr 2010;156:350–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Lai JS, Penedo FJ, Rychlik K, Liem RI. Health-related quality of life and adherence to hydroxyurea in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2017;64:e26369 10.1111/pbc.26369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oyeku SO, Driscoll MC, Cohen HW, et al. Parental and other factors associated with hydroxyurea use for pediatric sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Loiselle K, Lee JL, Szulczewski L, Drake S, Crosby LE, Pai AL. Systematic and meta-analytic review: medication adherence among pediatric patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol 2016;41:406–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haywood C Jr., Beach MC, Bediako S, et al. Examining the characteristics and beliefs of hydroxyurea users and nonusers among adults with sickle cell disease. Am J Hematol 2011;86:85–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster ES, Philbert D, de Vries TW, van Dijk L, Bouvy ML. “I just forget to take it”: asthma self-management needs and preferences in adolescents. J Asthma 2015;52:831–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modi AC, Quittner AL. Barriers to treatment adherence for children with cystic fibrosis and asthma: what gets in the way? J Pediatr Psychol 2006;31:846–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strouse JJ, Heeney MM. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell disease: efficacy, barriers, toxicity, and management in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012;59:365–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Penedo FJ, Lai JS, Rychlik K, Liem RI. Barriers to hydroxyurea adherence and health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Eur J Haematol 2017; 98:608–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reach G Role of habit in adherence to medical treatment. Diabet Med 2005;22(4):415–420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Darbari DS, Panepinto JA. What is the evidence that hydroxyurea improves health-related quality of life in patients with sickle cell disease? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program 2012;2012:290–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naar-King S, Montepiedra G, Nichols S, et al. Allocation of family responsibility for illness management in pediatric HIV. J Pediatr Psychol 2009;34:187–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ingerski LM, Anderson BJ, Dolan LM, Hood KK. Blood glucose monitoring and glycemic control in adolescence: contribution of diabetes-specific responsibility and family conflict. J Adolesc Health 2010;47:191–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Helgeson VS, Reynolds KA, Siminerio L, Escobar O, Becker D. Parent and adolescent distribution of responsibility for diabetes self-care: links to health outcomes. J Pediatr Psychol 2008;33:497–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Findley S, Rosenthal M, Bryant-Stephens T, et al. Community-based care coordination: practical applications for childhood asthma. Health Promot Pract 2011;12(Suppl 1):52S–62S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peretz PJ, Matiz LA, Findley S, Lizardo M, Evans D, McCord M. Community health workers as drivers of a successful community-based disease management initiative. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1443–1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Findley SE, Matos S, Hicks AL, Campbell A, Moore A, Diaz D. Building a consensus on community health workers’ scope of practice: lessons from New York. Am J Public Health 2012;102:1981–1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ayala GX, Vaz L, Earp JA, Elder JP, Cherrington A. Outcome effectiveness of the lay health advisor model among Latinos in the United States: an examination by role. Health Educ Res 2010;25:815–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen JK, Himmelfarb CR, Szanton SL, Bone L, Hill MN, Levine DM. COACH trial: a randomized controlled trial of nurse practitioner/community health worker cardiovascular disease risk reduction in urban community health centers: rationale and design. Contemp Clin Trials 2011;32:403–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hsu LL, Green NS, Donnell Ivy E, et al. Community health workers as support for sickle cell care. Am J Prev Med 2016;51(Suppl 1):S87–S98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Platt OS. Hydroxyurea for the treatment of sickle cell anemia. N EnglJ Med 2008;358:1362–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware RE. How I use hydroxyurea to treat young patients with sickle cell anemia. Blood 2010;115:5300–5311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smaldone A, Findley S, Bakken S, et al. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial to assess the feasibility of an open label intervention to improve hydroxyurea adherence in youth with sickle cell disease. Contemp Clin Trials 2016;49:134–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green NS, Manwani D, Qureshi M, Ireland K, Sinha A, Smaldone AM. Decreased fetal hemoglobin over time among youth with sickle cell disease on hydroxyurea is associated with higher urgent hospital use. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:2146–2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Findley S, Matos S, Hicks A, Chang J, Reich D. Community health worker integration into the health care team accomplishes the triple aim in a patient-centered medical home: a Bronx tale. J Ambul Care Manage 2014;37:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morisky DE, Green LW, Levine DM. Concurrent and predictive validity of a self-reported measure of medication adherence. Med Care 1986;24:67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nau DP. Proportion of days covered (PDC) as a preferred method of measuring medication adherence 2016. http://ep.yimg.com/ty/cdn/epill/pdcmpr.pdf.

- 40.Morisky DE, Ang A, Krousel-Wood M, Ward HJ. Predictive validity of a medication adherence measure in an outpatient setting. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2008;10:348–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 41.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis: Modeling Change and Event Occurrence New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Washington DL, Bowles J, Saha S, et al. Transforming clinical practice to eliminate racial-ethnic disparities in healthcare. J Gen Intern Med 2008;23:685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anderson B, Ho J, Brackett J, Finkelstein D, Laffel L. Parental involvement in diabetes management tasks: relationships to blood glucose monitoring adherence and metabolic control in young adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Pediatr 1997;130:257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McQuaid EL, Kopel SJ, Klein RB, Fritz GK. Medication adherence in pediatric asthma: reasoning, responsibility, and behavior. J Pediatr Psychol 2003;28:323–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McQuaid EL, Everhart RS, Seifer R, et al. Medication adherence among Latino and non-Latino white children with asthma. Pediatrics 2012;129:e1404–e1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orrell-Valente JK, Jarlsberg LG, Hill LG, Cabana MD. At what age do children start taking daily asthma medicines on their own? Pediatrics 2008;122:e1186–e1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Badawy SM, Thompson AA, Liem RI. Technology access and smart-phone app preferences for medication adherence in adolescents and young adults with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016;63:848–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Estepp JH, Winter B, Johnson M, Smeltzer MP, Howard SC, Hankins JS. Improved hydroxyurea effect with the use of text messaging in children with sickle cell anemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:2031–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garber MC, Nau DP, Erickson SR, Aikens JE, Lawrence JB. The concor-dance of self-report with other measures of medication adherence: a summary of the literature. Med Care 2004;42:649–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]