Abstract

Accurate hydrogen placement in molecular modeling is crucial for studying the interactions and dynamics of biomolecular systems. The carboxyl functional group is a prototypical example of a functional group that requires protonation during structure preparation. To our knowledge, when in their neutral form, carboxylic acids are typically protonated in the syn conformation by default in classical molecular modeling packages, with no consideration of alternative conformations, though we are not aware of any careful examination of this topic. Here, we investigate the general belief that carboxylic acids should always be protonated in the syn conformation. We calculate and compare the relative energetic stabilities of syn and anti acetic acid using ab initio quantum mechanical calculations and atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. We focus on the carboxyl torsional potential and configurations of microhydrated acetic acid from molecular dynamics simulations, probing the effects of solvent, force field (GAFF vs. GAFF2), and partial charge assignment of acetic acid. We show that while the syn conformation is the preferred state, the anti state may in some cases also be present under normal NPT conditions in solution.

1. Introduction

The carboxyl functional group, –COOH, is widespread in nature and highly biochemically relevant. It is present in amino acids that compose proteins, fatty acids of cell membranes, and naturally occurring organic compounds (e.g., niacin, citric acid, biotin). This group is very common in medicinal compounds, found in over 450 marketed drugs including nons-teroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., aspirin, ibuprofen), antibiotics (e.g., penicillin) and cholesterol-lowering statins (e.g., atorvastatin (Lipitor)).1,2 The presence of the hydrophilic carboxyl moiety on organic compounds can confer high solubility in water,3–5 which can be important to consider when designing new chemical reactions or developing new medicinal compounds. This group can also have important implications for pharmaceutical drugs; for example, drugs with a carboxyl functional group can be more metabolically unstable6 or have more difficulty diffusively crossing membranes.1,6 Given the carboxyl group’s ubiquitous presence in nature and its importance as a functional group, understanding its conformational preferences in various settings is fundamental for the design, modification, and property prediction of new and existing molecules.

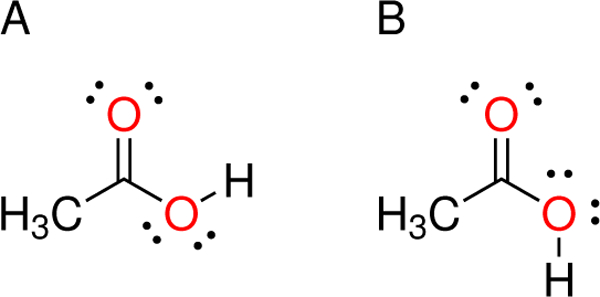

The preferred orientation of hydroxyl in the carboxyl functional group in solution is a matter of some debate, even for acetic acid, an archetypal carboxylic acid. Given a typical pKa of less than 5, the carboxyl group will usually be in the unprotonated, anionic form at neutral pH when exposed to the environment. However, the pKa may be significantly shifted as part of a ligand in a protein binding pocket or on protein side chains involved in reaction mechanisms. The two equilibrium conformations of the protonated carboxyl group are denoted syn (Figure 1(a)), where the O=C–O–H dihedral angle is defined here to be 0°, and anti (Figure 1(b)), where the O=C–O–H dihedral angle is defined here as 180°. It is widely believed that the preferred conformation of carboxyl is the syn arrangement, from which there is a large energetic penalty to reach the anti arrangement. The reasoning behind this idea lies in the perceived extra stability of intramolecular hydrogen bonding that occurs in the syn structure. This belief is supported by a number of experimental and theoretical studies done in gas phase, and there is no doubt that this is the preferred conformation in the gas phase.7–11

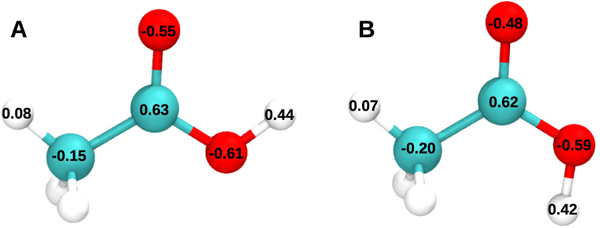

Figure 1:

Lewis structure of acetic acid in (a) syn and (b) anti conformation.

The orientational preference of COOH is considerably more complex outside of gas phase. While some workers remain convinced that syn will be more stable, a variety of evidence indicates that this may not always be the case. A recent review article12 discusses the competition between intramolecular and intermolecular hydrogen bonds in solution, stating that an intramolecular hydrogen bond may be disrupted in protic solution, such as water, when the increase in internal energy is offset by two or more solute-solvent intermolecular hydrogen bonds. Another study found that the carboxyl group has no strong preference, kinetically and thermodynamically, for the syn (or anti) conformation in proton transfer catalysis.13 The anti state may also be important to consider when calculating solvation free energies.14 In addition, the anti conformation is not insignificantly represented in structures from the Cambridge Structural Database,15 supported by related crystallographic and theoretical charge density studies.16,17 The carboxyl group may also be strongly influenced by its surroundings, such as that within a protein binding site, to prefer either the syn or anti state. In general, the local environment plays a large role in the conformational state of the carboxyl group, and the preferred orientation is not always obvious.

Past work investigating acetic acid in solvent predominantly considers the syn state, such as in studies characterizing hydrogen-bonding interactions of acetic acid microhydrates using DFT-B3LYP calculations,18 or assessing the dimer form in various stages of hydration theoretically 19,20 and experimentally.21 One recent work examining solvent stabilization using DFT-ωB97X-D calculations 22 indicates that water may modulate the conformational preferences of acetic acid; however, to our knowledge there has not been a systematic investigation of the preferred conformational state of the carboxyl group in solution. We believe that this collection of evidence on the orientational preference of COOH in solvent lacks a clear, definitive answer on whether both conformational states of the carboxyl group may reasonably be populated in normal aqueous solution when this group is in its neutral protonation state.

In this work, we aim to understand the relative conformational stability and energetic barrier for carboxyl functional group interconversion in both gas and aqueous phases. We present our investigation on monomeric acetic acid using both ab initio quantum mechanical (QM) calculations and atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

2. Methods

Past gas phase QM studies clearly indicate a preference for the syn structure of the COOH group such as in acetic acid. However, classical all-atom MD simulations show that both are equally favorable in solution, at least with the energy model (“force field”) employed.14 This could be a real effect of water on the conformational preferences, or a limitation of the force field employed. Therefore, we need to examine a more intermediate region between gas phase QM and solution phase atomistic MD to settle the issue more definitively. Specifically, we look at QM in implicit solvent as well as QM data of snapshots pulled from MD simulations; on the MD end, we consider the effects of force field as well as solvation state.

We present an overview of our approach then discuss the methods in further detail. A torsion drive was conducted on acetic acid over the aforementioned dihedral angle. We conduct restrained geometry optimizations using two different QM methods, each with and without the presence of implicit solvent. Then, we carry out a set of geometry optimizations on pentahydrated acetic acid with varied water configurations obtained from MD simulations. We compared these energies for both syn and anti structures.

On the MD side, we compute a series of free energy landscapes, also known as potentials of mean force (PMFs), from driving the relevant torsion in acetic acid. We evaluated the sensitivity of these one-dimensional free energy surfaces to the force field (GAFF or GAFF2), partial charge assignment, and solvation state. We consider the force field because this factor is likely to vary among users running MD simulations. The partial charge set assigned to a solute depends on the initial conformation and is typically fixed throughout MD simulations, so we investigate potential implications of choosing one set or another. Finally, we compare the results of gaseous and aqueous phases to shed light on how reasonably the syn and anti states may be occupied in either scenario.

2.1. Ab initio torsion drive of acetic acid

Acetic acid configurations of the carboxyl O=C–O–H dihedral angle were generated and used as input for both QM torsion drives and MD umbrella sampling simulations. The dihedral angle was rotated using VMD23 in 15° increments from 0° to 360°, yielding 24 total conformations.

The QM torsion drives were run using Turbomole version 7.124 with two different levels of theory: HF/6–31G* and TPSSh-D3BJ/def2-TZVP. The former method, using Hartree-Fock reference25 with the Pople 6–31G* basis set,26,27 was chosen for consistency with the methods often employed in parameterization of force fields used for molecular simulation. 28 This low level method also provides historical perspective contributing to the strong bias favoring the syn conformation of the carboxyl group. Taking a more rigorous approach, we employed the TPSSh hybrid functional29,30 with Grimme’s D3 dispersion correction31 and Becke-Johnson damping,32 in combination with the Karlsruhe triple-zeta basis set def2-TZVP.33 We chose the TPSSh functional because prior work indicates it is a suitable approach for treating the molecular dipole moments and polarizabilities of these hydrogen-bonding systems.34,35 We also run calculations in implicit solvent with each of the aforementioned methods using the conductor-like screening model (COSMO) with outlying charge corrections.36–39

2.2. Ab initio geometry optimizations from molecular dynamics configurations

We sample various configurations of water molecules around acetic acid by running separate MD simulations of the syn and anti conformations in a box of TIP3P water molecules. The structures were solvated using Antechamber40 within a cubic box with TIP3P waters41 such that the minimum distance between the solute and the edge of the periodic box was 12 Å. Dynamics were run using GROMACS version 5.0.4 with the leap-frog stochastic dynamics integrator and a 2 fs time step. We use a Langevin thermostat for the temperature at 298.15 K with a frictional constant of 2.0 ps-1. The pressure was maintained at 1 atm using the Parrinello-Rahman pressure coupling scheme with a time constant of 10 ps−1 and an isothermal compressibility of 4.5 ×10−5 bar-1. All bonds involving hydrogen atoms were constrained using the LINCS algorithm.42 The systems were simulated with 2500 steps of steepest descent minimization, 50 ps constant volume and temperature (NVT) equilibration, 5 ns of constant pressure and temperature (NPT) equilibration, and then 5 ns of NPT production. Trajectory snapshots were extracted of the most similar configurations for acetic acid and its five closest waters using a root-mean-square deviation clustering of geometries with a 2 A cutoff. This yielded 14 snapshots for the penta-hydrated syn conformation and 17 snapshots for the penta-hydrated anti conformation. Each snapshot was MM-optimized via OpenEye’s OEChem Python Toolkit43 using the MMFF94S force field,44–49 then subsequently QM-optimized using Turbomole version 7.124 with COSMO-TPSSh-D3BJ/def2-TZVP.29–33,36–39

2.3. MD simulations with umbrella sampling along carboxyl dihedral angle

We used umbrella sampling50 molecular dynamics to compute a potential of mean force (PMF) to analyze the free energy landscape projected onto this one-dimensional coordinate. We compared MD results with the GAFF51 and GAFF252 classical all-atom force fields, with partial charges assigned by the AM1-BCC53,54 approach. We consider effects of the solute partial charges in the MD simulations by carrying out MD simulations with AM1- BCC charges assigned from the syn configuration as well as charges assigned from the anti configuration. Energetics were examined in gas phase, then in solvent using explicit TIP3P water molecules.41

These simulations were run using GROMACS version 5.0.4.55 Each acetic acid configuration generated in VMD was set with partial charges from the AM1-BCC charge model53,54 on the syn (0°) conformation as implemented in OpenEye’s Python toolkits.43 The partial charges of the solute depend on initial configuration, so we also consider the anti (180°) conformation for computing partial charges. The O=C–O–H dihedral angle was restrained in both gas phase and aqueous MD simulations, using a harmonic force constant of 300 kJ/mol/(rad2) (approximately 0.022 kcal/mol/(deg2)).

For the gas phase simulations, the reference temperature of 298.15 K was maintained using Langevin dynamics with a frictional constant of 1.0 ps-1. Maintaining the GROMACS parameters described earlier, the systems underwent steepest descent minimization over 2500 steps, NVT equilibration for 50 ps, and NVT production for 1 ns.

For the explicit solvent simulations, the solvation parameters and other MD simulation settings were maintained as described earlier in the section, “Ab initio geometry optimizations from molecular dynamics configurations.” These systems were simulated with 2500 steps of steepest descent minimization, 50 ps NVT equilibration, 50 ps NPT equilibration, and 5 ns NPT production. The configurations with dihedral angle around 270° seemed not converged, so six conformations were extended 5 ns for a total of 10 ns each: 65°, 90°, 105°, 255°, 270°, 285°. However, there was little to no change in the resulting PMFs.

Analysis of all umbrella sampling simulations was completed with the MBAR algorithm56 to produce the potentials of mean force (PMFs) for rotation of the carboxyl dihedral angle.

3. Results and discussion

Results from both QM and MD approaches support former work and the general understanding that syn is favored in gas phase. They also indicate that the anti conformation may also be populated to a significant extent in water. We address our QM results first and then discuss MD results.

3.1. Ab initio torsion drive of acetic acid

Our QM calculations in gas phase and implicit solvent show that syn is highly favored in the gas phase but the difference becomes less significant in solvent. From the torsion drive obtained via ab initio QM calculations, the syn-anti energy difference is 7.14 kcal/mol with the basic HF/6–31G* method and decreases to 5.24 kcal/mol with the higher level of theory using the TPSSh functional (Figure 2). With COSMO, a similar trend is seen in which the higher level of theory yields a smaller energy difference between the syn and anti structures. With either level of theory, adding implicit solvent significantly lowers the relative energy difference between syn and anti from 5–7 kcal/mol to 2–3 kcal/mol. A 5–7 kcal/mol difference is large enough that such configurations would occur only extremely rarely, whereas 2–3 kcal/mol is enough that such conformations will occur sporadically in solution (3–7% of the time) and could potentially easily be stabilized by interactions with a nearby receptor or other biomolecule with a strain energy no larger than that reported in many binding interactions,57,58 making it potentially relevant functionally.

Figure 2:

QM torsion drive of acetic acid carboxyl dihedral angle for HF and TPSSh methods. In each case, implicit solvation with COSMO reduces the energy barrier and the relative minima energy to 5–7 kcal/mol and 2–3 kcal/mol respectively.

We now turn our focus to the energy barrier from the syn state to the anti state. This feature is not particularly critical in molecular simulation, as in most cases systems will be at equilibrium given sufficient relaxation time and sampling. That being said, the energy barrier has implications for interconversion between the two states. One conformation may be more structurally relevant than the other in certain scenarios, and a modeler may wish to achieve an accurate representation of the populations of both conformations. The barrier associated with the rotation of the carboxyl dihedral angle determines how easy it is to interconvert between and sample different conformations. From our QM results, we see a large energetic cost or barrier of 13–14 kcal/mol separating the syn form from the anti form in gas phase. Solvation with COSMO reduces this barrier height to around 11 kcal/mol.

Overall, the relative energy difference between the syn and anti conformations of acetic acid appears not very large, especially in the aqueous conditions relevant to biochemistry. The relative energy comparisons from the QM torsion drives are summarized in the top four lines of Table 1. Note that, from our QM results, these are relative energies rather than relative free energies; with MD in the following section; we obtain relative free energies.

Table 1:

Summary of relative energy differences between syn and anti conformations of acetic acid as well as free energy barriers of interconversion. The first four lines are results from QM torsion drives, and the last eight from umbrella sampling are from atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. Energies are listed in units of kcal/mol.

| Method | Solvation | minimaa | barrier |

|---|---|---|---|

| HF/6–31G* | gas | 7.1 | 13.7 |

| HF/6–31G* | COSMO | 2.8 | 11.2 |

| TPSSh/def2-TZVPb | gas | 5.2 | 13.2 |

| TPSSh/def2-TZVP | COSMO | 1.6 | 11.2 |

| vac_SC_GAFF | gas | 6.2±0.2 | 12.7±0.3 |

| vac_SC_GAFF2 | gas | 5.9±0.2 | 11.7±0.3 |

| vac_AC_GAFF | gas | 3.4±0.2 | 11.0±0.3 |

| vac_AC_GAFF2 | gas | 3.3±0.2 | 10.1±0.3 |

| sol_SC_GAFF | TIP3P | −0.8±0.1 | 7.0±0.2 |

| sol_SC_GAFF2 | TIP3P | −0.7±0.1 | 6.4±0.2 |

| sol_AC_GAFF | TIP3P | −1.3±0.1 | 6.7±0.2 |

| sol_AC_GAFF2 | TIP3P | −1.4±0.1 | 6.1±0.2 |

All relative energy differences are taken with respect to acetic acid’s syn conformation.

Dispersion corrections added with all TPSSh calculations in this work. See details in text.

3.2. Ab initio geometry optimizations from molecular dynamics configurations

To rule out the possibility that stabilization of the anti form in the torsion drive is due to implicit solvent model alone, and to determine whether explicit water might provide additional stabilization, we examined acetic acid with explicit water molecules. We first examined trihydrated syn and anti acetic acid (details in supporting information). However, recent work on the microhydration of acetic acid suggests that the particular arrangement of water molecules may be important when comparing energetic stabilities of acetic acid conformations.22 Given that we are interested in solution-phase behavior, the actual solutionphase geometry of water molecules around acetic acid then becomes very important. In order to reduce any artificial effects of water placement, we sample various conformations of water molecules around acetic acid by running molecular dynamics simulations for each of the syn and anti forms. Both simulations were run using the syn charges for context as these are predominantly used in present-day molecular simulations. Configurations of acetic acid with its five nearest waters were clustered by root-mean-square deviation of geometries. The most common arrangements were extracted for QM optimization in implicit solvent using the method COSMO-TPSSh-D3BJ/def2-TZVP.

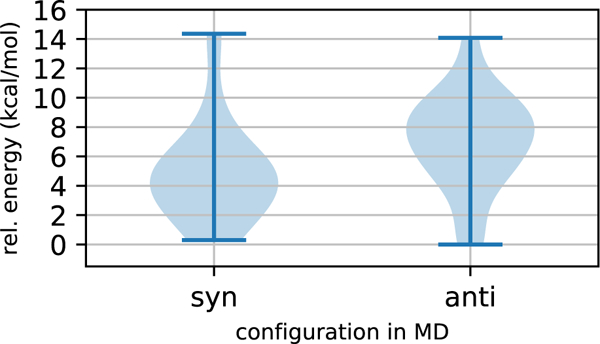

The violin plots in Figure 3 display the distributions for the relative energies of the syn (left side) and anti (right side) pentahydrated configurations of acetic acid. Here, we see that the distribution for the syn configurations skews toward lower energies compared to the anti configurations. However, the energy values of the extrema are quite similar, and the population of the anti form at low energies is nonnegligible.

Figure 3:

Violin plots for relative energy distributions of pentahydrated syn and anti conformations of acetic acid. The data represent COSMO-TPSSh-D3BJ/def2-TZVP energies of configurations taken from MD simulations of the syn form (14 snapshots) and the anti form (17 snapshots).

3.3. MD simulations with umbrella sampling along carboxyl dihedral angle

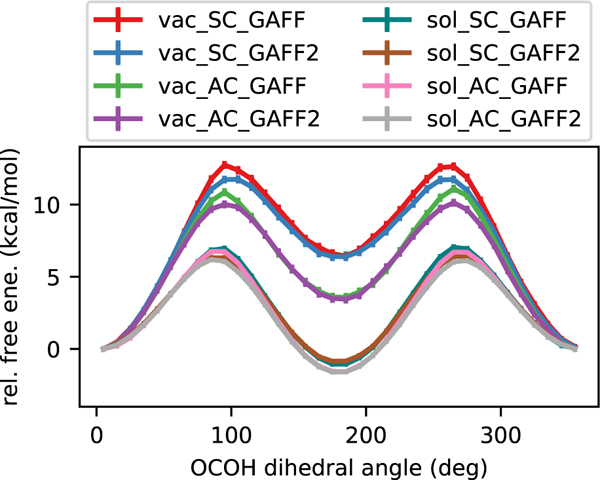

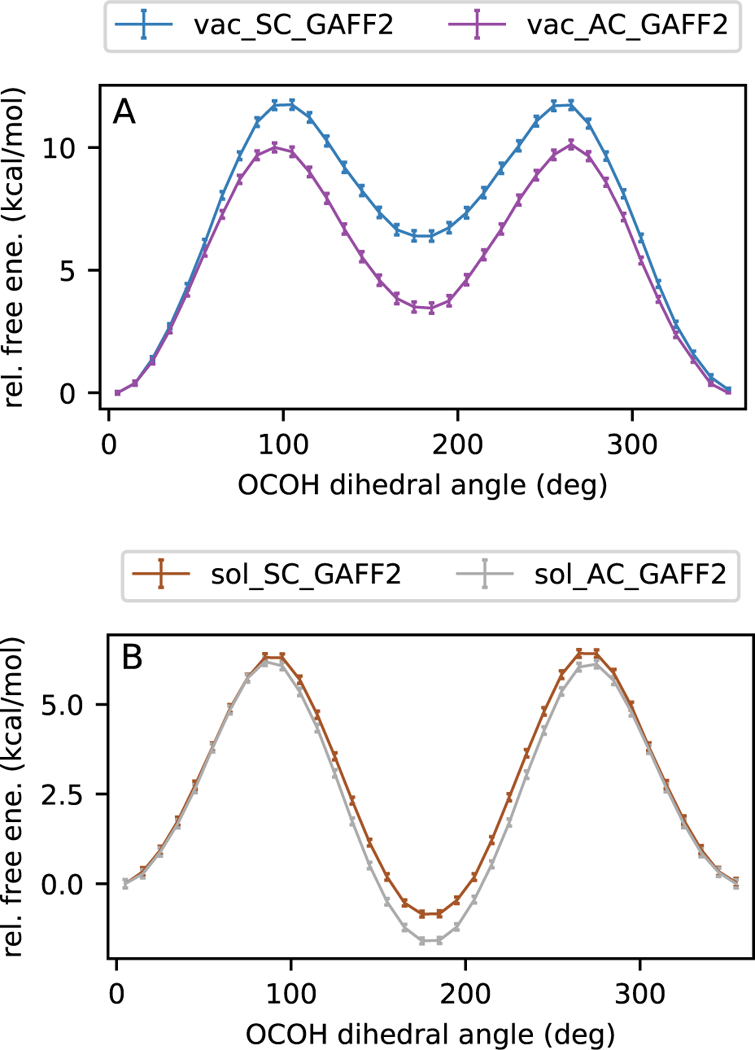

Our above QM calculations study only conformational energies, not free energies, so we computed the one-dimensional free energy landscape (the potential of mean force, or PMF) of rotating the acetic acid dihedral angle with classical molecular dynamics. The MD results in gas phase and in explicit solvent are in qualitative agreement with our QM data and indicate that water substantially increases the stability of the anti conformation. We considered various force fields, partial charge sets, and solvation states for a total of eight PMFs. Atomic partial charges are held fixed within our simulations, as is typical in MD, but these charges are sensitive to the molecular conformation when assigning charges, so we assigned charges using both conformations. Hereafter we use the notation SC for acetic acid partial charges obtained from the syn conformation and AC for charges obtained from the anti conformation. Error bars on the PMFs are obtained from the MBAR estimator.56 We present a comprehensive comparison in Figure 4 and in Table 1 and discuss each of these three factors (force field, charge set, and solvation state) separately.

Figure 4:

PMFs of rotating the acetic acid carboxyl dihedral angle. We consider variations on the force eld (GAFF, GAFF2), solute AM1-BCC partial charges (starting from syn or anti), and solvation state (gas phase, explicit TIP3P waters).

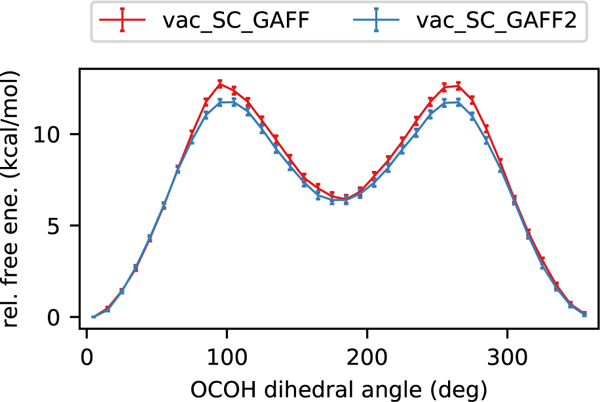

Considering the GAFF and GAFF2 force fields, the PMFs are in good agreement with each other in both gas and aqueous phases as well as with either SC or AC (Figures 4, 5). We observe consistent relative free energies between the syn and anti minima. In gas phase, for the SC solute, the syn structure is favored in free energy by 6.2±0.2 kcal/mol with GAFF and 5.9±0.2 kcal/mol with GAFF2 (Figure 5). In aqueous phase, the anti structure is favored in free energy by −0.7±0.1 kcal/mol with GAFF and −1.4±0.1 kcal/mol with GAFF2 (Figure 4, teal vs. brown). These qualitative conclusions are the same when considering the AC solute. Thus, GAFF and GAFF2 give very similar results for the conformational equilibrium of acetic acid which holds true regardless of the partial charge set. Overall these results, at least within the classical framework, indicate that explicit solvent provides approximately 5–8 kcal/mol of stabilization of the anti conformation relative to the syn conformation. This trend is in the same direction as that provided by COSMO implicit solvent, but provides further stabilization.

Figure 5:

Comparison of GAFF and GAFF2 force fields in PMFs of rotating the acetic acid carboxyl dihedral angle. Both are in strong agreement with each other. The PMFs displayed in this figure came from gas phase simulations with syn charges. Similar conclusions were drawn for PMFs from aqueous simulations and from using anti charges (Figure 4).

We also compare the two force fields in terms of the conformational transition barriers. We note that the GAFF barrier height is higher than the GAFF2 barrier in each pairwise combination of the two force fields with various solvent and charge models. The barrier height differences are 0.9±0.4 kcal/mol in gas phase (compare barrier heights in Figure 4 for red vs. blue and for green vs. purple). The rotational barriers differ by 0.6±0.2 kcal/mol in aqueous phase (compare barrier heights in Figure 4 for teal vs. brown and for pink vs. gray). For both gaseous and aqueous states, the effects of the partial charges on the PMFs are stronger than those of the force field. For example, in Figure 4, the red and green curves are more distinct from each other, while the red and blue curves are more similar. Since the partial charges of the solute may affect the PMFs more so than the force field, as shown here, one should carefully consider other likely conformations when assigning partial charges. Next we further investigate the solute partial charge sets.

There is a pronounced difference in the PMFs depending on the conformation used to charge acetic acid (Figure 6). Charges are typically fixed throughout a molecular dynamics simulation, meaning that initial charge assignment is important for capturing correct energetics throughout a simulation. The free energy difference between the syn and anti structures is notably larger in gas phase than in water. When we use the syn form to obtain AM1-BCC charges (SC), the gas phase PMFs are higher in energy for both the barrier height and the two minima (Figure 7 (a)) compared to using the anti form to obtain AM1-BCC charges (AC). Qualitatively, the SC set is slightly stronger in magnitude than the AC set, meaning a slightly stronger polarization along the bonds of the carboxyl group; this is consistent with the intramolecular hydrogen bonding aspect of the syn conformation. The stronger SC partial charges contribute to increased stabilization of the lower-energy syn structure in gas phase, which results in a greater free energy difference and barrier height compared to AC. On the other hand, in water, (Figure 7 (b)), syn and anti are closer in relative free energy for SC than for AC. In this setting, syn is higher in energy than anti. Once again, the stronger SC partial charges contribute to increased stabilization of syn, in this case via more stabilizing interactions with the solvent. Here, the two minima are closer in free energy. Therefore we see again that the relative free energies at the minima are governed more strongly by solute charges than by force field.

Figure 6:

AM1-BCC charges generated for (a) syn and (b) anti configurations of acetic acid.

Figure 7:

Comparison of syn and anti solute charges in PMFs of rotating the acetic acid carboxyl dihedral angle. In each situation with anti charges (A) and syn charges (B), the AC set more strongly stabilizes the anti conformation than the SC set.

We take a final look at the MD PMFs in the lens of gaseous versus aqueous phases. These results are in harmony with earlier work on ibuprofen (a carboxylic acid) which found that the syn conformation was favorable in vacuum but the anti conformation was slightly preferred in water.14 The major takeaway from the aqueous phase PMFs is that the anti conformation of acetic acid is the lower free energy state in solution due to an increased ability to form stabilizing interactions with the solvent. This conclusion qualitatively parallels the result obtained with COSMO-QM calculations on microhydrated acetic acid which showed that the anti conformation is lower in energy than the syn conformation by about 1.6 kcal/mol, at least for certain arrangements of water molecules.

Overall, the MD results are qualitatively consistent with QM calculations in determination of relative energy differences of the minima and energy barriers for conformational interconversion. The SC charge set seems better than the AC set in reproducing the relative energy differences obtained with QM DFT in gas phase and in implicit solvent, consistent with our previous practice of considering this conformation more important when assigning charges.

To summarize our PMF results, we considered the effects of force field, charge set, and solvation state on the relative minima free energies as well as on the transition barriers between the two minima. The force fields GAFF and GAFF2 yielded generally similar results to each other. The PMFs in both gas phase and aqueous phase revealed strong dependence on solute charges, especially at the minima. More specifically, the set of partial charges assigned to acetic acid is sensitive to the orientation of O–H in the carboxyl group, leading to variations of up to several kcal/mol in the free energy difference between the syn and anti structures. Lastly, the dihedral rotation free energy barriers between the syn - anti conformations are more dependent on the charge set than the force field in gas phase simulations, while they are more influenced by the force field in aqueous phase simulations. All eight PMFs, obtained from permutation of the force field, solute charges, and solvation state are summarized in Figure 4 and Table 1.

4. Conclusions

Our results call into question the conventional wisdom that carboxylic acids will almost always be in the “more stable” syn conformation in biomolecular systems. Typically, the increased stability of the syn form is understood to be from the stabilizing intramolecular interaction between the hydrogen atom in the hydroxyl group and the carbonyl oxygen. This idea is in tune with gas phase results we present in this work. However, in aqueous phase, we conclude that the anti state may nearly be as populated as the syn state due to stabilizing interactions from the solvent. Thus, for MD studies that involve a carboxylic acid or other functional group with possible intramolecular hydrogen bonds, it may be necessary to ensure sufficient sampling of all potentially relevant conformations in solution. This can be challenging given the particularly large barrier associated with rotation of the carboxylic acid torsion.

Our findings also have implications for partial charge calculations for parameter assignment for MD simulations. Carboxylic acids are a case in which neither partial charge set adequately represents the electrostatics of the solute as it samples various conformations. When generating an empirical force field, such as for a small molecule ligand, charges are typically computed for a particular given conformation. These fixed charges are then used for scenarios involving conformational change. In this work, we observe that different solute charges may lead to deviations in relative free energies to as large as 3 kcal/mol. Interconversion is not expected to be frequent, given that the torsional barrier is at least 6 kcal/mol. For that reason, one may wish to treat syn and anti conformation charges individually, though this could present difficulties in cases that interconversion is needed for convergence (e.g., a carboxylic acid in a binding site where one conformation forms better contacts than the other). As an alternative approach, the use of polarizable charges may provide a more holistic picture of the carboxyl group’s variable nature.

The carboxyl conformational equilibrium has implications for several other types of studies. Hydration free energy calculations may lead to results which depend substantially on the starting conformation. For example, kinetic trapping into one particular conformation can lead to computed hydration free energies which are sensitive to starting conformation and vary by more than 2 kcal/mol because of large torsional barriers.14 This work also informs efforts to accurately calculate pKa values for ionizable side chains in proteins, i.e., aspartate and glutamate.59–69 An accurate insight into the preferred aqueous phase structure of the carboxyl group is important for catalysis, with impacts in atmospheric science and industrial processes.70 Further impact may be in crystal engineering and drug co-crystallization, in which the carboxyl group is often used to promote aqueous solubility. 5 Theoretical studies on proton transfer such as on solvated acetic acid71 or on green fluorescent protein72,73 typically employ the syn conformation due to its expected energetic preference; however, it is worth investigating possible adaptations of carboxyl groups to their local environments. Being aware of the carboxyl moiety’s nuanced conformational preferences in different environments may thus lead to better insight for calculated properties, reactivity, and molecular design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Prof. Filipp Furche and Matthew Agee for helpful discussions on QM methods and for support in using the Turbomole software package, respectively. VTL acknowledges funding the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program. DLM appreciates financial support from the National Institutes of Health (1R01GM108889–01) and the National Science Foundation (CHE 1352608), and computing support from the UCI GreenPlanet cluster, supported in part by NSF Grant CHE-0840513.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available

Raw data and Python scripts for all figures, configuration input files for all calculations, initial and final coordinates of all structures, Python script for computing free energies from PMFs, computations and discussion on trihydrated acetic acid, comparison of acetic acid geometries to existing literature, discussion on choice of QM method with calculations on water hexamers.

Conflict of interest

David Mobley serves on the scientific advisory board of OpenEye Scientific Software and is an Open Science Fellow with Silicon Therapeutics.

References

- (1).Ballatore C; Huryn DM; Smith AB Carboxylic Acid (Bio)Isosteres in Drug Design. ChemMedChem 2013, 8, 385–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lou Y; Zhu J In Bioactive Carboxylic Compound Classes; Lamberth C, Dinges J, Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, 2016; pp 221–236. [Google Scholar]

- (3).David SE; Timmins P; Conway BR Impact of the Counterion on the Solubility and Physicochemical Properties of Salts of Carboxylic Acid Drugs. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2012, 38, 93–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).McNamara DP; Childs SL; Giordano J; Iarriccio A; Cassidy J; Shet MS; Mannion R; O’Donnell E; Park A Use of a Glutaric Acid Cocrystal to Improve Oral Bioavailability of a Low Solubility API. Pharm Res 2006, 23, 1888–1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Desiraju GR Crystal Engineering: From Molecule to Crystal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 9952–9967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Lassila T; Hokkanen J; Aatsinki S-M; Mattila S; Turpeinen M; Tolonen A Toxicity of Carboxylic Acid-Containing Drugs: The Role of Acyl Migration and CoA Conjugation Investigated. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2015, 28, 2292–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Nagy PI The Syn-Anti Equilibrium for the COOH Group Reinvestigated. Theoretical Conformation Analysis for Acetic Acid in the Gas Phase and in Solution. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2013, 1022, 59–69. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Nagy PI; Smith DA; Alagona G; Ghio C Ab Initio Studies of Free and Monohydrated Carboxylic Acids in the Gas Phase. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 486–493. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Sato H; Hirata F The Syn-/Anti-Conformational Equilibrium of Acetic Acid in Water Studied by the RISM-SCF/MCSCF Methodl. Journal of Molecular Structure: THEOCHEM 1999, 461–462, 113–120. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Wiberg KB; Laidig KE Barriers to Rotation Adjacent to Double Bonds. 3. The Carbon-Oxygen Barrier in Formic Acid, Methyl Formate, Acetic Acid, and Methyl Acetate. The Origin of Ester and Amide Resonance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987, 109, 5935–5943. [Google Scholar]

- (11).Derissen JL A Reinvestigation of the Molecular Structure of Acetic Acid Monomer and Dimer by Gas Electron Diffraction. Journal of Molecular Structure 1971, 7, 67–80. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Nagy PI Competing Intramolecular vs. Intermolecular Hydrogen Bonds in Solution. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2014, 15, 19562–19633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Montzka TA; Swaminathan S; Firestone RA Reversal of Syn-Anti Preference for Carboxylic Acids along the Reaction Coordinate for Proton Transfer. Implications for Intramolecular Catalysis. J. Phys. Chem. 1994, 98, 13171–13176. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Klimovich PV; Mobley DL Predicting Hydration Free Energies Using All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Multiple Starting Conformations. J Comput Aided Mol Des 2010, 24, 307–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).D’Ascenzo L; Auffinger P A Comprehensive Classification and Nomenclature of Car-boxyl–Carboxyl(Ate) Supramolecular Motifs and Related Catemers: Implications for Biomolecular Systems. Acta Cryst B 2015, 71, 164–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Pal R; Reddy MBM; Dinesh B; Venkatesha MA; Grabowsky S; Jelsch C; Guru Row T. N. Syn vs Anti Carboxylic Acids in Hybrid Peptides: Experimental and Theoretical Charge Density and Chemical Bonding Analysis. J. Phys. Chem. A 2018, 122, 3665–3679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).G. Medvedev M.; S. Bushmarinov I.; A. Lyssenko K. Z-Effect Reversal in Carboxylic Acid Associates. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 6593–6596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Gao Q; Leung KT Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions in Acetic Acid Monohydrates and Dihydrates by Density-Functional Theory Calculations. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2005, 123, 074325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Pašalić H; Tunega D; Aquino AJA; Haberhauer G; Gerzabek MH; Lischka H The Stability of the Acetic Acid Dimer in Microhydrated Environments and in Aqueous Solution. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2012, 14, 4162–4170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Chocholoušová J; Vacek J; Hobza P Acetic Acid Dimer in the Gas Phase, Nonpolar Solvent, Microhydrated Environment, and Dilute and Concentrated Acetic Acid: Ab Initio Quantum Chemical and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 3086–3092. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Ouyang B; Howard J, B. The Monohydrate and Dihydrate of Acetic Acid : A HighResolution Microwave Spectroscopic Study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Krishnakumar P; Maity DK Microhydration of Neutral and Charged Acetic Acid. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 493–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Humphrey W; Dalke A; Schulten K VMD: Visual Molecular Dynamics. Journal of Molecular Graphics 1996, 14, 33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).TURBOMOLE V7.1 2016, a development of University of Karlsruhe and Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, 1989–2007, TURBOMOLE GmbH, since 2007; available from http://www.turbomole.com.

- (25).Häser M; Ahlrichs R Improvements on the Direct SCF Method. J. Comput. Chem. 1989, 10, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Hehre WJ; Ditchfield R; Pople JA Self—Consistent Molecular Orbital Methods. XII. Further Extensions of Gaussian—Type Basis Sets for Use in Molecular Orbital Studies of Organic Molecules. The Journal of Chemical Physics 1972, 56, 2257–2261. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Hariharan PC; Pople JA The Influence of Polarization Functions on Molecular Orbital Hydrogenation Energies. Theoret. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213–222. [Google Scholar]

- (28).Cornell WD; Cieplak P; Bayly CI; Gould IR; Merz KM; Ferguson DM; Spellmeyer DC; Fox T; Caldwell JW; Kollman PA A Second Generation Force Field for the Simulation of Proteins, Nucleic Acids, and Organic Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- (29).Staroverov VN; Scuseria GE; Tao J; Perdew JP Comparative Assessment of a New Nonempirical Density Functional: Molecules and Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2003, 119, 12129–12137. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Staroverov VN; Scuseria GE; Tao J; Perdew JP Erratum: “Comparative Assessment of a New Nonempirical Density Functional: Molecules and Hydrogen-Bonded Complexes” [J. Chem. Phys. 119, 12129 (2003)]. The Journal of Chemical Physics 121,2004, 11507–11507. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Grimme S; Antony J; Ehrlich S; Krieg H A Consistent and Accurate Ab Initio Parametrization of Density Functional Dispersion Correction (DFT-D) for the 94 Elements H-Pu. The Journal of Chemical Physics 2010, 132, 154104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Grimme S; Ehrlich S; Goerigk L Effect of the Damping Function in Dispersion Corrected Density Functional Theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Weigend F; Ahlrichs R Balanced Basis Sets of Split Valence, Triple Zeta Valence and Quadruple Zeta Valence Quality for H to Rn: Design and Assessment of Accuracy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005, 7, 3297–3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Laurent AD; Jacquemin D TD-DFT Benchmarks: A Review. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2013, 113, 2019–2039. [Google Scholar]

- (35).Hickey AL; Rowley CN Benchmarking Quantum Chemical Methods for the Calculation of Molecular Dipole Moments and Polarizabilities. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 3678–3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Klamt A; Schüürmann G COSMO: A New Approach to Dielectric Screening in Solvents with Explicit Expressions for the Screening Energy and Its Gradient. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 799–805. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Klamt A; Jonas V; Bürger T; Lohrenz JCW Refinement and Parametrization of COSMO-RS. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 5074–5085. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Eckert F; Klamt A Fast Solvent Screening via Quantum Chemistry: COSMO-RS Approach. AIChE J. 2002, 48, 369–385. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Sinnecker S; Rajendran A; Klamt A; Diedenhofen M; Neese F Calculation of Solvent Shifts on Electronic G-Tensors with the Conductor-Like Screening Model (COSMO) and Its Self-Consistent Generalization to Real Solvents (Direct COSMO- RS). J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2235–2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Wang J; Wang W; Kollman PA; Case DA Automatic Atom Type and Bond Type Perception in Molecular Mechanical Calculations. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2006, 25, 247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Jorgensen WL; Chandrasekhar J; Madura JD; Impey RW; Klein ML Comparison of Simple Potential Functions for Simulating Liquid Water. J. Chem. Phys. 1983, 79, 926–935. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Hess B; Bekker H; Berendsen HJC; Fraaije JGEM LINCS: A Linear Constraint Solver for Molecular Simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 1997, 18, 1463–1472. [Google Scholar]

- (43).OEChem, version 2.1.1, OpenEye Scientific Software Inc.: Santa Fe, NM, USA

- (44).Halgren TA Merck Molecular Force Field. II. MMFF94 van Der Waals and Electrostatic Parameters for Intermolecular Interactions. J. Comput. Chem. 19–96, 17, 520–552. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Halgren TA Merck Molecular Force Field. I. Basis, Form, Scope, Parameterization, and Performance of MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 490–519. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Halgren TA Merck Molecular Force Field. III. Molecular Geometries and Vibrational Frequencies for MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 553–586. [Google Scholar]

- (47).Halgren TA; Nachbar RB Merck Molecular Force Field. IV. Conformational Energies and Geometries for MMFF94. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 587–615. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Halgren TA Merck Molecular Force Field. V. Extension of MMFF94 Using Experimental Data, Additional Computational Data, and Empirical Rules. J. Comput. Chem. 1996, 17, 616–641. [Google Scholar]

- (49).Halgren TA MMFF VI. MMFF94s Option for Energy Minimization Studies. J. Comput. Chem. 1999, 20, 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Torrie GM; Valleau JP Nonphysical Sampling Distributions in Monte Carlo Free-Energy Estimation: Umbrella Sampling. Journal of Computational Physics 1977, 23, 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- (51).Wang J; Wolf RM; Caldwell JW; Kollman PA; Case DA Development and Testing of a General Amber Force Field. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1157–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Case DA, Betz RM, Cerutti DS, Cheatham TE III, Darden TA, Duke RE, Giese TJ, Gohlke H, Goetz AW, Homeyer N, Izadi S, Janowski P, Kaus J, Kovalenko A, Lee TS, LeGrand S, Li P, Lin C, Luchko T, Luo R, Madej B, Mermelstein D, Merz KM, Monard G, Nguyen H, Nguyen HT, Omelyan I, Onufriev A, Roe DR, Roitberg A, Sagui C, Simmerling CL, Botello-Smith WM, Swails J, Walker RC, Wang J, Wolf RM, Wu X, Xiao L and Kollman PA, AMBER 2016, University of California, San Francisco: 2016, [Google Scholar]

- (53).Jakalian A; Bush BL; Jack DB; Bayly CI Fast, Efficient Generation of High-Quality Atomic Charges. AM1-BCC Model: I. Method. J. Comput. Chem. 2000, 21, 132–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Jakalian A; Jack DB; Bayly CI Fast, Efficient Generation of High-Quality Atomic Charges. AM1-BCC Model: II. Parameterization and Validation. J. Comput. Chem. 2002, 23, 1623–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Abraham MJ; Murtola T; Schulz R; Pall S; Smith JC; Hess B; Lindahl E GROMACS: High Performance Molecular Simulations through Multi-Level Parallelism from Laptops to Supercomputers. SoftwareX 2015, 1–2, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Shirts MR; Chodera JD Statistically Optimal Analysis of Samples from Multiple Equilibrium States. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Mobley DL; Dill KA Binding of Small-Molecule Ligands to Proteins: “What You See” Is Not Always “What You Get”. Structure 2009, 17, 489–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Sahai MA; Biggin PC Quantifying Water-Mediated Protein-Ligand Interactions in a Glutamate Receptor: A DFT Study. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 7085–7096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).van Vlijmen HWT; Schaefer M; Karplus M Improving the Accuracy of Protein pKa Calculations: Conformational Averaging versus the Average Structure. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 1998, 33, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Li H; Robertson AD; Jensen JH Very Fast Empirical Prediction and Rationalization of Protein pKa Values. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2005, 61, 704–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Bashford D; Karplus M pKa’s of Ionizable Groups in Proteins: Atomic Detail from a Continuum Electrostatic Model. Biochemistry 1990, 29, 10219–10225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Beroza P; Case DA Including Side Chain Flexibility in Continuum Electrostatic Calculations of Protein Titration. J. Phys. Chem. 1996, 100, 20156–20163. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Kilambi KP; Gray JJ Rapid Calculation of Protein pKa Values Using Rosetta. Biophysical Journal 2012, 103, 587–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Yang A-S; Gunner MR; Sampogna R; Sharp K; Honig B On the Calculation of pKas in Proteins. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 1993, 15, 252–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Thurlkill RL; Grimsley GR; Scholtz JM; Pace CN pK Values of the Ionizable Groups of Proteins. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 1214–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Song Y; Mao J; Gunner MR MCCE2: Improving Protein pKa Calculations with Extensive Side Chain Rotamer Sampling. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2231–2247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Warwicker J Simplified Methods for pKa and Acid pH-Dependent Stability Estimation in Proteins: Removing Dielectric and Counterion Boundaries. Protein Sci. 1999, 8, 418–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Antosiewicz J; McCammon JA; Gilson MK The Determinants of pKas in Proteins. Biochemistry 1996, 35, 7819–7833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Antosiewicz J; McCammon JA; Gilson MK Prediction of Ph-Dependent Properties of Proteins. Journal of Molecular Biology 1994, 238, 415–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kumar M; Busch DH; Subramaniam B; Thompson WH Organic Acids Tunably Catalyze Carbonic Acid Decomposition. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 5020–5028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Gu W; Frigato T; Straatsma TP; Helms V Dynamic Protonation Equilibrium of Solvated Acetic Acid. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2007, 46, 2939–2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Scharnagl C; Raupp-Kossmann R; Fischer SF Molecular Basis for pH Sensitivity and Proton Transfer in Green Fluorescent Protein: Protonation and Conformational Substates from Electrostatic Calculations. Biophysical Journal 1999, 77, 1839–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Lill MA; Helms V Proton Shuttle in Green Fluorescent Protein Studied by Dynamic Simulations. PNAS 2002, 99, 2778–2781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.