Abstract

Zinc levels are high in pancreatic β-cells, and zinc is involved in the synthesis, processing and secretion of insulin in these cells. However, precisely how cellular zinc homeostasis is regulated in pancreatic β-cells is poorly understood. By screening the expression of 14 Slc39a metal importer family member genes, we found that the zinc transporter Slc39a5 is significantly down-regulated in pancreatic β-cells in diabetic db/db mice, obese ob/ob mice and high-fat diet-fed mice. Moreover, β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout mice have impaired insulin secretion. In addition, Slc39a5-deficient pancreatic islets have reduced glucose tolerance accompanied by reduced expression of Pgc-1α and its downstream target gene Glut2. The down-regulation of Glut2 in Slc39a5-deficient islets was rescued using agonists of Sirt1, Pgc-1α and Ppar-γ. At the mechanistic level, we found that Slc39a5-mediated zinc influx induces Glut2 expression via Sirt1-mediated Pgc-1α activation. These findings suggest that Slc39a5 may serve as a possible therapeutic target for diabetes-related conditions.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13238-018-0580-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: zinc, zinc transporter, pancreatic islets, β-cells, insulin secretion

Introduction

Diabetes is the one of most common chronic diseases in the global population, giving rise to tissue damage and secondary complications. Impaired insulin secretion has become the principal cause of the recent drastic increase in the incidence of diabetes (Ashcroft and Rorsman, 2012). Most recently, the zinc and zinc transporters have been increasing associated with diabetes (Rutter et al., 2016).

Zinc, an essential trace element, has long been recognized as an important player in the biosynthesis, processing and secretion of insulin (Li, 2014). During exocytosis, zinc is co-secreted with insulin into the extracellular space and can be transported back into β-cells and neighboring cells (Franklin et al., 2005). Moreover, perfusing pancreatic islets and MIN6 cells (a pancreatic β-cell line) with stimulating levels of glucose or KCl drastically increases the rate of zinc transport into the cytosol (Gyulkhandanyan et al., 2006). In addition, in diabetes, pancreatic zinc levels are reduced by approximately half compared to levels in the non-diabetic pancreas (Scott and Fisher, 1938). In contrast, rats fed a zinc-deficient diet have reduced serum and total pancreatic zinc levels, but normal zinc levels in pancreatic islets of Langerhans (Sondergaard et al., 2006). Although several studies have investigated zinc levels in pancreatic islets, how zinc homeostasis is regulated under physiological and pathological conditions remains unclear.

In mammals, zinc homeostasis is regulated primarily by two transporter family members, with 14 genes encoding the SLC39A importers (Zrt- and Irt-like proteins, or ZIPs) and 10 genes encoding the SLC30A exporters (zinc efflux transporters, or ZnTs) (Huang and Tepaamorndech, 2013; Jeong and Eide, 2013). Among these zinc transporters, Slc30a8 is the most well-studied zinc exporter in pancreatic β-cells. Slc30a8 is highly expressed in β-cells, where it plays a role in insulin processing and secretion by transporting zinc via granules (Pound et al., 2009). In contrast, the SLC39A family of zinc importers has not been studied in detail. Down-regulation of Slc39a6 and Slc39a7 expression significantly decreases: I) cytosolic zinc influx, II) the insulin granule exocytosis rate, and III) insulin secretion in both MIN6 β-cells and primary mouse islet cells (Liu et al., 2015). Conversely, increasing cellular zinc levels by overexpressing Slc39a6 or Slc39a7 has no effect on insulin secretion in healthy β-cells, suggesting that zinc does not directly stimulate insulin secretion, but rather suggesting that intracellular zinc content must be tightly regulated in order to maintain β-cell function (Liu et al., 2015). Of the 14 Slc39a family members, only Slc39a4 has been knocked out in murine β-cells, with no resulting effect on glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) in vivo (Hardy et al., 2015).

To investigate further the role of Slc39a family members in diabetes, we measured the mRNA levels of all 14 Slc39a family members in pancreatic β-cells in three mouse models of diabetes. Our screen revealed that Slc39a5 was the only gene with consistently reduced expression. We therefore generated β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout mice and global Slc39a5 knockout (Slc39a5−/−) mice in order to examine the function of Slc39a5 in β-cells in vivo.

Results

Slc39a5 is significantly down-regulated in pancreatic islets obtained from high-fat diet (HFD)-fed, ob/ob and db/db mice

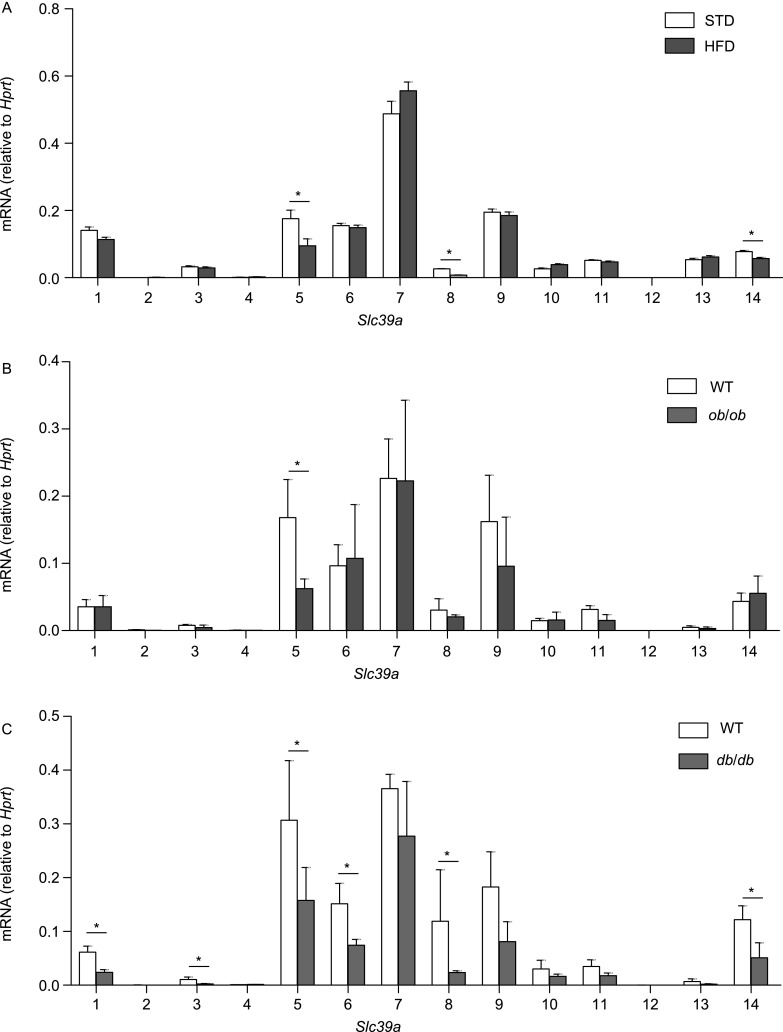

First, we measured the mRNA levels of all 14 Slc39a genes (Slc39a1 through Slc39a14) in the pancreatic islets of HFD-fed, ob/ob, and db/db mice. Mice carrying a spontaneous mutation in leptin (ob/ob) and mice carrying a spontaneous mutation in the leptin receptor (db/db) were first characterized back in 1950 (Ingalls et al., 1950) and 1966 (Hummel et al., 1966), respectively. Together, these three mouse models have been widely used to investigate the pathological processes that underlie obesity and diabetes(Fellmann et al., 2013). As shown in Figure 1, our analysis revealed that the expression level of Slc39a5 was decreased by 46% (HFD-fed mice), 63% (ob/ob mice) and 49% (db/db mice) in these models relative to control littermates. Among all 14 Slc39a genes, only Slc39a5 was significantly reduced in all three mouse models.

Figure 1.

Summary of mRNA levels of all Slc39a gene family members measured in pancreatic islets isolated from HFD-fed, ob/ob and db/db mice. The mRNA levels of all 14 Slc39a genes were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type mice fed either a standard chow diet (STD) or a HFD (A), wild-type and ob/ob mice (B), and wild-type and db/db mice (C); n = 3 mice per group. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test)

Impaired glucose tolerance and GSIS in Slc39a5-deficient pancreatic β-cells

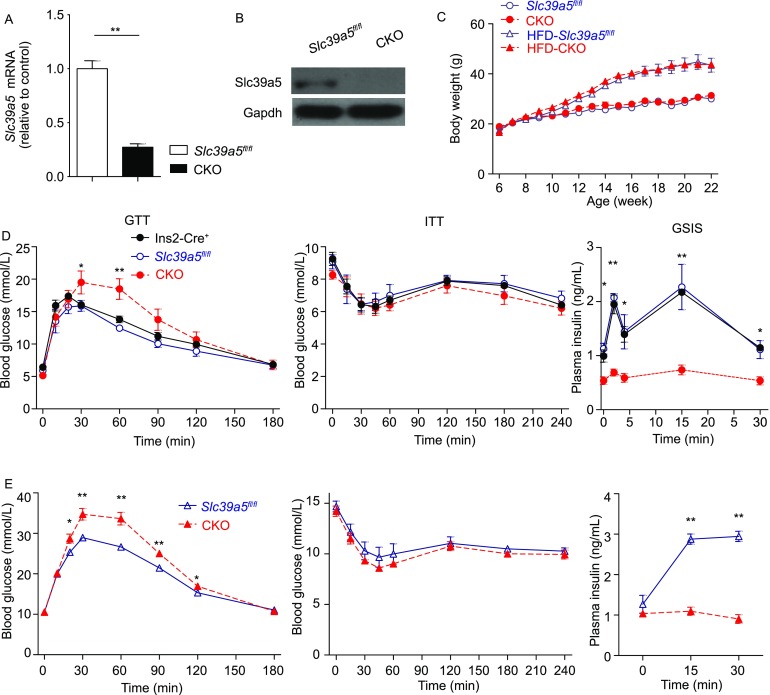

Next, to study the function of Slc39a5 in vivo, we generated a conditional Slc39a5 knockout mouse using a LoxP insertion strategy (Fig. S1). Crossing the resulting Slc39a5fl/fl mice with mice that express Cre recombinase driven by the rat insulin (Ins2) promoter yielded Slc39a5fl/fl;Ins2-Cre+ mice (hereafter referred to as CKO mice), which lack Slc39a5 expression selectively in pancreatic β-cells (Fig. S2A). Loss of Slc39a5 expression in the pancreatic islets of CKO mice was confirmed at the mRNA (Fig. 2A) and protein (Fig. 2B) levels. The expression levels of other Slc39a genes were quantified using qPCR in islets of Slc39a5 knockout and their controls. As shown in Figure S3, we found that there are no compensational changes of other Slc39a genes in Slc39a5 deficient islets. The offspring of Slc39a5fl/fl × Ins2-Cre+ crosses were born at the expected Mendelian ratio.

Figure 2.

β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout (CKO) mice have impaired glucose tolerance and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. (A and B) Slc39a5 mRNA (A) and Slc39a5 protein levels (B) were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (C) The body weight of Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice fed either normal chow diet or a high-fat diet starting at 6 weeks of age (n = 6 mice per group). (D and E) Control (Slc39a5fl/fl or Ins2-Cre+) and CKO mice fed either normal chow diet (D) or a high-fat diet (E), followed by the glucose tolerance test (GTT, left), insulin tolerance test (ITT, middle), and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS, right) (n = 6 mice per group). *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test)

The body weight of CKO mice was similar to control (Slc39a5fl/fl) littermates, even at six months of age (Fig. 2C). In addition, fasting glucose levels were similar between CKO mice and Slc39a5fl/fl mice. However, when challenged with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of glucose (1 g/kg body weight) in a glucose tolerance test (GTT), blood glucose levels in CKO mice were significantly increased both 30 and 60 min after stimulation compared to control (Slc39a5fl/fl or Ins2-Cre+) littermates (Fig. 2D, left). In contrast, insulin sensitivity was similar between CKO and control (Slc39a5fl/fl or Ins2-Cre+) mice (Fig. 2D, middle). Finally, intraperitoneal GSIS was detected at 0, 2, 5, 15 and 30 min following glucose injection. Both first and second phases of GSIS were significantly increased in Slc39a5fl/fl or Ins2-Cre+ mice, but were blunted in CKO mice (Fig. 2D, right).

Next, we examined the role of Slc39a5 in the pathogenesis of HFD-induced diabetes by feeding 6-week-old Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice with a high-fat diet containing 60% of calories derived from fat. Although both groups progressively gained more weight compared to their respective control-fed groups, we found no difference in body weight between HFD-Slc39a5fl/fl and HFD-CKO, even after 16 weeks on the HFD (Fig. 2C). When both HFD-Slc39a5fl/fl and HFD-CKO mice were subjected to a GTT assay, the HFD-CKO mice had significantly increased blood glucose levels starting 30 min after glucose injection, and this increase lasted until 120 min after glucose injection (Fig. 2E, left). In contrast, although HFD significantly decreased insulin sensitivity in both the CKO and Slc39a5fl/fl mice, there was no difference between HFD-CKO and HFD-Slc39a5fl/fl mice (Fig. 2E, middle). Finally, HFD-fed Slc39a5fl/fl mice had a prolonged increase in insulin secretion following glucose injection; in contrast—and similar to CKO mice fed a standard diet—GSIS was unchanged in the HFD-fed CKO mice (Fig. 2E, right). Since the majority mice used in this study were 3 to 6 months old, we next address the possibility of age-effect on the observed phenotypes. GTT has been conducted for 2 or 12 months old mice, and CKO mice showed similar phenotypes among different ages (Fig. S4). Taken together, these results show that β-cell-specific deletion of Slc39a5 reduces both glucose tolerance and GSIS, but has no effect on insulin sensitivity under either normal or high-fat dietary conditions.

Pancreatic islet function is impaired in CKO mice

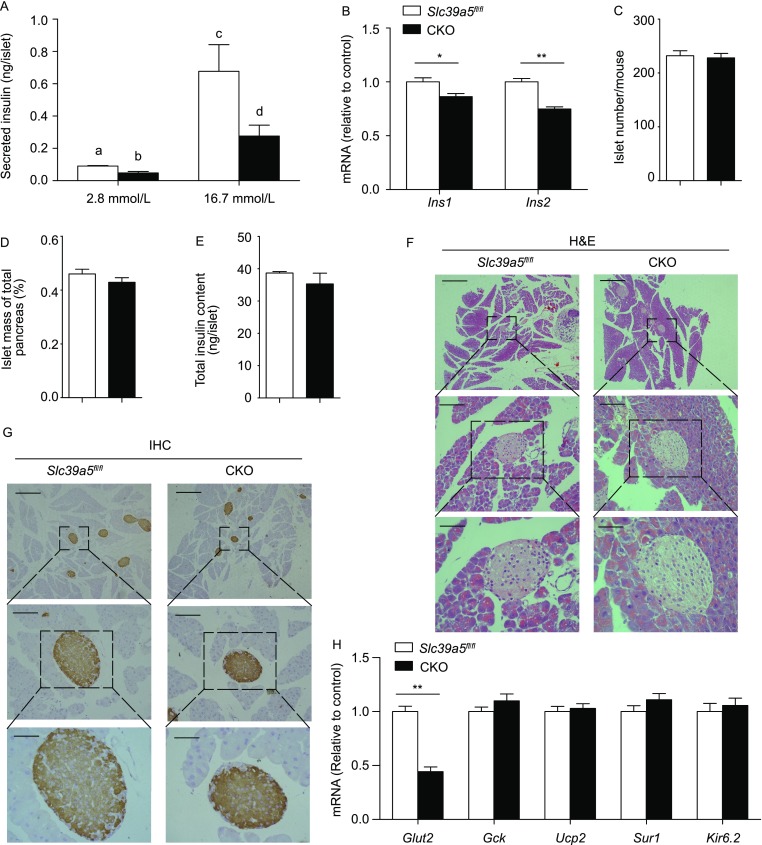

To examine the functional changes induced by the loss of Slc39a5 in pancreatic β-cells, primary pancreatic islets were isolated from CKO and Slc39a5fl/fl mice, cultured ex vivo, and then stimulated with 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose. Stimulation with 16.7 mmol/L glucose significantly increased insulin secretion in both Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO islets; however, insulin secretion was significantly reduced in CKO islets compared to Slc39a5fl/fl islets (Fig. 3A). In addition, the mRNA levels of both Ins1 and Ins2 were significantly lower in CKO islets compared to control islets (Fig. 3B). On the other hand, the number of islets, the mass of the islet relative to the total pancreas, and the total insulin content were similar between Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (Fig. 3C–E). Moreover, islet morphology (Fig. 3F) and pancreatic insulin staining (Fig. 3G) were also similar between Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice. These results suggest that Slc39a5 regulates β-cell function primarily via GSIS, not via islet integrity or insulin storage.

Figure 3.

CKO pancreatic β-cells have impaired function. (A) Insulin secretion measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice and incubated in 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose (n = 5 mice per group). (B) Ins1 and Ins2 mRNA levels were measured in islets obtained from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (C–E) Summary of the number of pancreatic islets (C), relative islet mass (D), and total islet insulin content (E) in Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (n = 3 mice per group). (F) Example H&E-stained pancreatic islets in Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice. (G) Example immunohistochemical staining for insulin in pancreatic islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice. The scale bars in panels (F) and (G) represent 250 μm (top), 50 μm (middle) and 25 μm (bottom). (H) The mRNA levels of the indicated genes were measured in pancreatic islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice and are expressed relative to the respective Slc39a5fl/fl level (n = 4 mice per group). (I) The mRNA levels of the indicated Glut genes were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type mice and are expressed relative to β-actin (n = 3 mice per group). (J) Western blot analysis of Glut2 protein in islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice. (K) Islets were obtained from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice and incubated with 2-NBDG (20 mmol/L) (n = 4 mice per group). (L) Islets were obtained from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice, incubated in 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose, and the ATP/ADP ratio was measured (n = 5 mice per group). The data in panels (A) and (L) were analyzed by ANOVA, and groups with different letters differed significantly; the data in panels (B–E), (H) and (K) were analyzing using a Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01)

Next, we measured the mRNA levels of several genes that encode key regulators of GSIS, including Glut2, Gck, Ucp2, Sur1 and Kir6.2. We found that Glut2 was the only gene significantly down-regulated in CKO islets (Fig. 3H). Glut2 is the major glucose transporter expressed in β-cells (Fig. 3I), and consistent with our mRNA analysis, Glut2 protein levels were significantly decreased in CKO islets (Fig. 3J). In addition, using a 2-NBDG uptake assay, we found that CKO islets have impaired glucose uptake compared to control (Fig. 3K). Finally, the ATP/ADP ratio was significantly lower in CKO islets compared to control islets following stimulation with 16.7 mmol/L glucose (Fig. 3L).

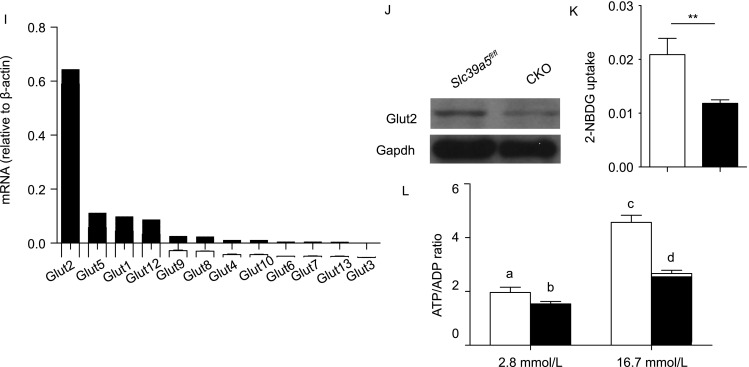

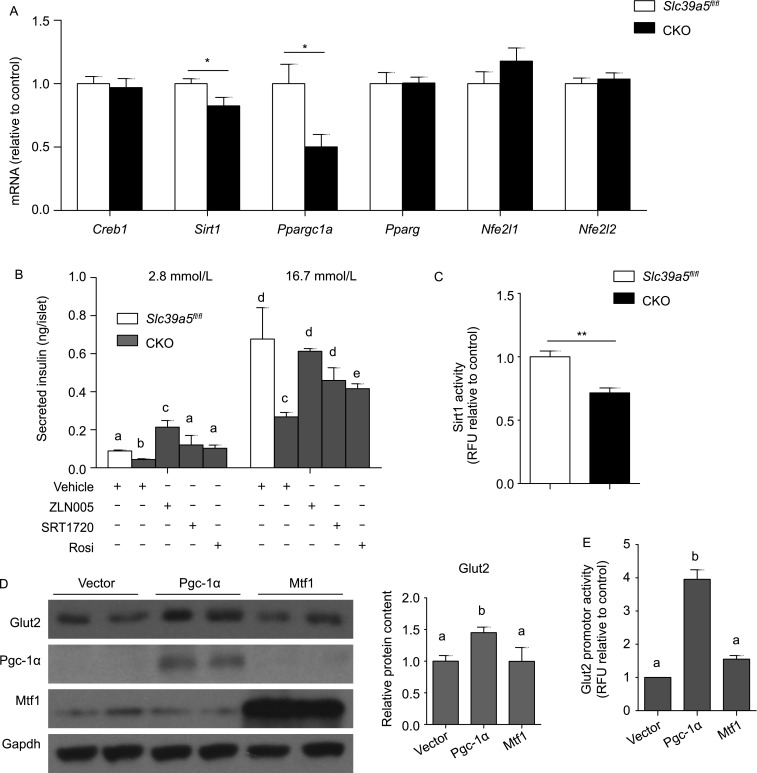

Slc39a5 regulates insulin secretion via Pgc-1α

In an attempt to identify the underlying mechanism by which Slc39a5 regulates GSIS, we measured the mRNA levels of genes involved in the major signaling pathways related to Glut2, Ins1 and Ins2 expression (Huang et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2014a; Wang et al., 2014b). Our analysis revealed that genes involved in the antioxidant responsive element (ARE) and metal responsive element (MRE) signaling pathways are down-regulated in CKO islets compared to control islets (Figs. 4A and S5A), whereas genes in the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) and wingless-type MMTV integration site (WNT) pathways did not differ between CKO and control mice (Fig. S5B–D). Specifically, the mRNA levels of Sirt1, Ppargc1a and Mtf1 expression were significantly lower in CKO islets compared to Slc39a5fl/fl islets (Figs. 4A and S5A).

Figure 4.

Slc39a5-regulated insulin secretion in β-cells is mediated by Pgc-1α. (A) Creb1, Sirt1, Ppargc1a, Pparg, Nfe2l1 and Nfe2l2 mRNA levels were measured in pancreatic islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (n = 4 mice per group). (B) Secreted insulin levels were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice after treated with ZLN005, SRT1720, or rosiglitazone (Rosi) and stimulated with 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose. (C) Sirt1 enzyme activity was measured in islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice (n = 4 mice per group). (D) MIN6 cells were transfected with either Pgc-1α or Mtf1, and Western blot analysis was performed for the indicated proteins. The relative Glut2 expresion was quantified by using integrated optical densitometry of blots. (E) Glut2 promoter activity was measured using a dual luciferase reporter assay in MIN6 cells transfected with either Pgc-1α or Mtf1 (n = 3 per group). The data in panels (B) and (E) were analyzed by ANOVA, and groups with different letters differed significantly; the data in panels a and c were analyzed using a Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01)

Next, we treated islets with the Pgc-1α activator ZLN005 and found that ZLN005 (20 μmol/L for 12 h) rescued insulin in CKO islets (Fig. 4B). Similarly, both the Sirt1 activator SRT1720 (2 μmol/L for 12 h) and the Ppar-γ agonist rosiglitazone (1 μmol/L for 12 h) rescued insulin secretion in CKO islets (Fig. 4B). Moreover, consistent with our finding of reduced Sirt1 mRNA in CKO islets, we found significantly reduced Sirt1 activity in CKO β-cells compared to control cells (Fig. 4C). In addition, overexpressing Pgc-1α in MIN6 cells increased Glut2 expression, whereas overexpressing Mtf1 had no effect on Glut2 expression, even though Mtf1 expression was decreased in CKO islets (Fig. 4D). Finally, overexpressing Pgc-1α, but not Mtf1, significantly up-regulated Glut2 promotor activity in MIN6 cells (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these results indicated that loss of Slc39a5 expression in mouse pancreatic islets significantly reduces the expression and activity of Sirt1, as well as Ppargc1a expression, and activating ARE signaling rescues both Glut2 expression and impaired insulin secretion.

Given the role that Pgc-1α plays in the mitochondria, we looked for morphological changes in the mitochondria of CKO and control β-cells using transmission electron microscopy. We found that CKO β-cells—but not control β-cells—have mitochondrial swelling (Fig. S6A). In addition, Rhodamine 123 uptake was significantly higher in CKO cells compared to control cells (Fig. S6B), suggesting altered mitochondrial membrane potential. In contrast, the expression of mitochondrial complexes I, II, III, IV and V in pancreatic islets did not differ between CKO and control mice (Fig. S6C). Similarly, we found no difference between CKO and control islets with respect to expression of the mitochondrial genes Atp6, Nd4, Cytb or Cox3 (Fig. S6D), or the electron transfer chain complex genes Ndufs3, Cycs, Cox8b, Atp5c1, Atp5d or Atp5 (Fig. S6E). Thus, we conclude that deleting Slc39a5 expression in pancreatic β-cells only mildly affects mitochondrial function.

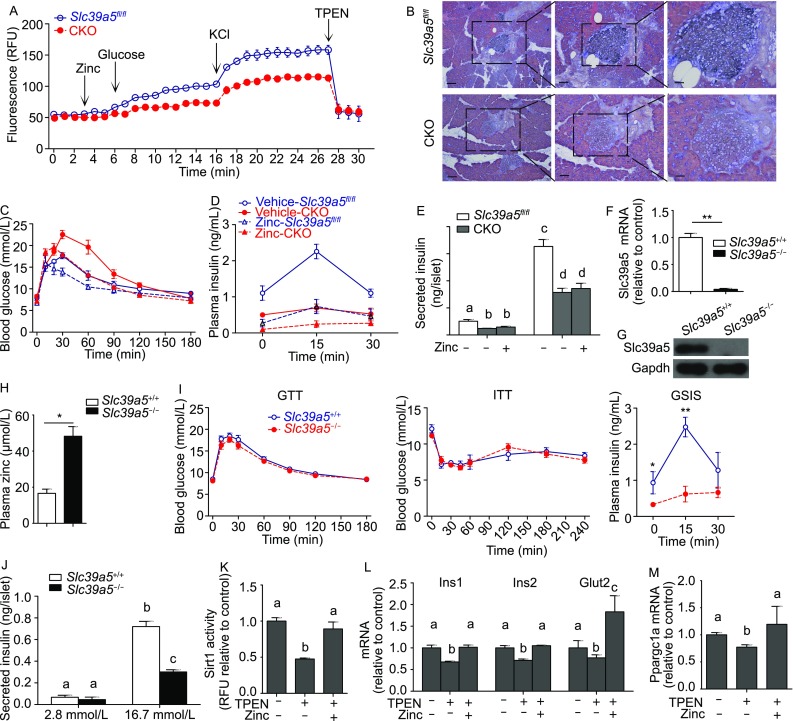

Zinc-dependent effects of Slc39a5 deletion on insulin secretion

Next, we examined the capacity of CKO β-cells to take up zinc by measuring zinc levels in CKO and control β-cells following treatment with glucose (16.7 mmol/L) and KCl (30 mmol/L) in the continued presence of 10 μmol/L ZnCl2. We found that both glucose- and KCl-induced zinc uptake was significantly impaired in CKO β-cells compared to control cells (Fig. 5A). In addition, Timm’s staining of pancreatic islets to stain zinc showed significantly reduced zinc in CKO mice compared to control mice (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Slc39a5 deficiency reduces zinc, Ppargc1a expression and insulin secretion. (A) Time course of zinc content measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice and loaded with the fluorescent zinc indicator FluoZin-3AM. Where indicated, ZnCl2 (10 μmol/L), glucose (16.7 mmol/L), KCl (30 mmol/L), and TPEN (10 μmol/L) were applied (n = 5 mice per group). (B) Timm’s zinc staining of pancreas islets from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice. From left to right, the scale bars indicate 100 μm, 50 μm and 25 μm. GTT (C) and GSIS (D) were measured in Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice treated with vehicle or ZnSO4 (10 mg/kg body weight, i.p.) for 5 consecutive days (n = 6 mice per group). (E) Secreted insulin levels were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5fl/fl and CKO mice after treated with zinc and stimulated with 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose. (F) Slc39a5 mRNA was measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice (n = 3 mice per group). (G) Western blot analysis of Slc39a5 protein in isolated islets from Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice; the data are representative of 3 mice each. (H) Plasma zinc content was measure in Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice (n = 3 mice per group). (I) GTT, ITT, and GSIS were performed in Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice (n = 6 mice each). (J) Secreted insulin levels were measured in pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice after stimulated with 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose (n = 5 mice per group). (K) Sirt1 activity was measured in islets isolated from wild-type mice treated with TPEN or TPEN plus zinc (n = 3 mice per group). (L) mRNA levels of Ins1, Ins2 and Glut2 were measured in islets from wild-type mice treated with TPEN or TPEN plus zinc (n = 4). (M) mRNA levels of Ppargc1a were measured in the islets of wild-type mice treated with TPEN or TPEN plus zinc (n = 4 mice each). The data in panels (E) and (J–M) were analyzed by ANOVA, and groups with different letters differed significantly; the data in panels (A), (C), (D), (F), (H) and (I) were analyzed using a Student’s t-test (*P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01)

We then treated CKO mice with ZnSO4 (10 mg/kg/day, i.p.) for 5 consecutive days and found that this treatment restored glucose tolerance to the same level as untreated Slc39a5fl/fl mice (Fig. 5C). In contrast, this treatment had no significant effect on GSIS in CKO mice (Fig. 5D). Furthermore, zinc rescue experiments in cultured CKO islets were conducted, and the results showed that supplementation of zinc (20 μmol/L for 12 h) in the medium failed to rescue the impaired GSIS in CKO islets (Fig. 5E).

Previous studies showed that global Slc39a5 knockout (Slc39a5−l−) mice have increased zinc accumulation in the body (Geiser et al., 2013); we generated a global Slc39a5 knockout (Slc39a5−l−) mouse by crossing our Slc39a5fl/fl mice with CMV-Cre+ mice (Fig. S2B). We confirmed the loss of Slc39a5 expression at both the mRNA (Fig. 5F) and protein (Fig. 5G) levels. Compared to Slc39a5+l+ mice, Slc39a5−l− mice had significantly increased plasma zinc levels (Fig. 5H). We then performed the GTT and ITT in these mice and found no difference between Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice (Fig. 5I, left and middle). However, GSIS was significantly lower in the Slc39a5−l− mice compared to Slc39a5+l+ littermates (Fig. 5I, right). We then measured ex vivo GSIS in primary pancreatic islets isolated from Slc39a5−l− and Slc39a5+l+ mice following stimulation with 2.8 or 16.7 mmol/L glucose. Consistent with our in vivo results, Slc39a5−l− islets had significantly reduced GSIS compared to Slc39a5+l+ islets (Fig. 5J).

Next, we treated islets obtained from wild-type mice treated with TPEN (N,N,N’,N’-Tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl) ethylenediamine) in the absence or presence of zinc. We found that TPEN reduced Sirt1 activity in wild-type islets, and zinc treatment restored Sirt1 activity to baseline levels (Fig. 5K). Moreover, TPEN treatment reduced the levels of Ins1, Ins2, Glut2 and Ppargc1a mRNA, and zinc treatment restored the full expression of all four genes (Fig. 5L and 5M). Taken together, these results suggest that Slc39a5 deficiency impairs zinc uptake, ARE-mediated signaling, and GSIS in pancreatic β-cells.

Discussion

Genome-wide association studies found that a nonsynonymous polymorphism in the human SLC30A8 gene is associated with type 2 diabetes (T2D) (Saxena et al., 2007; Sladek et al., 2007). In mice, deleting Slc30a8 expression selectively in pancreatic β-cells causes reduced glucose tolerance accompanied by impaired insulin synthesis, processing, and secretion (Wijesekara et al., 2010). Recently, Li et al. reported that transgenic mice that overexpress human SLC30A8 with the R325W polymorphism have reduced levels of zinc and proinsulin in pancreatic islets (Li et al., 2017). After consuming a high-fat diet, however, these mice have increased glucose tolerance (Li et al., 2017), supporting the notion that zinc plays an important role in maintaining β-cell function in pancreatic islets. In this study, since only Slc39a5 was consistently down-regulated in all three obese T2D mouse models, we mainly focused on functional characterization of the role of Slc39a5 in pancreatic β-cells. However, it will be interesting to see whether other Slc39a family members such as Slc39a6 (Liu et al., 2015), Slc39a8 and Slc39a14 also play roles in regulating zinc homeostasis in β-cells.

Despite these findings, the effects of zinc on GSIS remain poorly understood. Previous studies found that robust zinc uptake is related to glucose stimulation and/or high KCl stimulation (Gyulkhandanyan et al., 2006). However, the physiological role and underlying regulatory mechanisms remain unclear. Here, we screened 14 genes that encode Slc39a family members and identified Slc39a5 as the sole gene down-regulated in three mouse models of obesity. Although the leptin signaling is activated in HFD-induced obese mice (Lin et al., 2000), it is actually absent in ob/ob and db/db mice. The expression of Slc39a5 was significantly reduced in all three obese and diabetes murine models, which suggests that the leptin signaling does not directly regulate Slc39a5 expression. Using β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout (CKO) mice, we found that: I) these mice have reduced glucose tolerance and impaired GSIS, but no change in fasting glucose levels or insulin sensitivity; II) primary islets isolated from these mice have impaired GSIS, decreased glucose uptake capacity, and reduced Glut2 expression, with no change in islet integrity or insulin storage; and III) CKO islets have decreased zinc influx, Sirt1 activity, and Pgc-1α expression.

Deleting Slc39a5 selectively in pancreatic β-cells decreased zinc levels in pancreatic islets but did not affect serum zinc levels. Interestingly, global Slc39a5 knockout mice also have decreased zinc levels in islets as well as increased serum zinc levels. Based on these observations, our β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout mice—and other β-cell-specific Slc39a knockout mice—will likely serve as a valuable tool for precisely controlling zinc transport selectively in pancreatic islets and will likely facilitate the study of their physiological function and underlying regulatory mechanisms.

Because zinc has pleiotropic effects on glucose homeostasis (Chimienti, 2013), we tested the effect of zinc on glucose homeostasis in mice. Surprisingly, we found that injecting CKO mice with zinc did not restore GSIS, although it did return GTT to control levels. A previous study reported that zinc has an insulin-like effect on facilitating glucose uptake in periphery tissues mainly through phosphoinositol-3-kinase/AKT signaling and GLUT4 translocation (Tang and Shay, 2001). This insulin-like effect of zinc could be the major factor attributed to the different impacts of zinc treatment on GTT (Fig. 5C) and GSIS (Fig. 5D) in the CKO mice. Slc39a5 also plays a role in zinc homeostasis in the intestine, liver and exocrine pancreatic acinar tissue (Wang et al., 2004), and global deletion of Slc39a5 causes zinc accumulation in the serum (Geiser et al., 2013), which is consistent with our results. Similar to zinc-treated CKO mice, Slc39a5−/− mice also have impaired GSIS compared to control littermates, although they still have normal blood glucose levels. The normal GTT in the Slc39a5−/− mice (Fig. 5I) could also result from the increased zinc levels in the circulation (Fig. 5H), which could directly facilitate glucose uptake in periphery tissues despite impaired GSIS (Fig. 5I and 5J). Thus, our results further support the notion that excess zinc reduces blood glucose levels directly via an insulino-mimetic effect, not by stimulating insulin secretion.

One of our significant findings is that Sirt1-Pgc-1α signaling—and its downstream target Glut2—is decreased in pancreatic islets in CKO mice. Mitochondrial morphology and mitochondrial membrane potential were also affected—albeit mildly—in CKO islets. Together, impaired glucose uptake and reduced mitochondrial function result in reduced ATP production and impaired GSIS. In humans, SIRT1 has been associated with T2D (Cruz et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2011). In addition, variants in the PPARGC1A gene have been associated with T2D (Bhat et al., 2007; Yang et al., 2011; Chand et al., 2016). Interestingly, the PPARGC1A Gly482Ser polymorphism is associated with reduced PPARGC1A expression and reduced insulin secretion (Ling et al., 2008). In some T2D patients, the expression of PPARGC1A is reduced by 90% and is correlated with impaired insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. Furthermore, using siRNA to knock down PPARGC1A in human pancreatic islets reduced insulin secretion by 41% (Ling et al., 2008). Furthermore, we previously reported increased GSIS and increased Glut2 expression in mice treated with the glutathione peroxidase mimic ebselen; these effects were mediated primarily through Pgc-1α-mediated activation of ARE signaling (Wang et al., 2014b). Taken together, the results of the present study provide key insight into the molecular mechanisms underlying impaired islet function in response to β-cell-specific zinc deficiency.

Notably, our data suggest that the phenotypic change of GTT and GSIS was mainly due to impaired insulin secretion but not synthesis. Although the transcripts of Ins1 and Ins2 were indeed decreased in the Slc39a5-deficient islets, the protein levels of pancreatic insulin measured by total insulin content (Fig. 3E) and immunohistochemistry staining (Fig. 3G) remain unchanged between Slc39a5-deficient and control islets. The unchanged protein level of insulin could result from blunted insulin secretion despite the transcripts of Ins1 and Ins2 were slightly decreased. In addition, the first and second phases of GSIS were detected and the result clearly showed diminished insulin secretion in both phases (Fig. 2D), which may also implicate a direct impairment of glucose response.

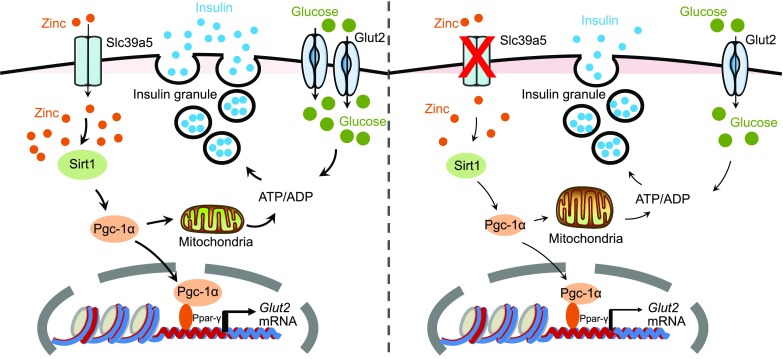

In summary, we functionally characterized the role of the zinc transporter Slc39a5 in pancreatic β-cells. With respect to the underlying mechanism, we show that Slc39a5 regulates GSIS in islets primarily through the zinc-activated Sirt1-Pgc-1α axis (Fig. 6). Our results suggest that Slc39a5 deficiency leads to significantly lower intracellular zinc levels. As a result, zinc deficiency down-regulates Sirt1 activity and Pgc-1α expression, which further affects Glut2 expression and mitochondrial function. Consequently, Slc39a5 deficiency in β-cells attenuates both glucose sensing and insulin secretion. These findings pave the way to better understanding how islet function is regulated by zinc and zinc transporters, and they provide possible therapeutic targets for diabetes. We propose that specific zinc transporters have evolved in order to tightly regulate intracellular zinc homeostasis in pancreatic β-cells under a wide range of metabolic conditions, thereby controlling insulin secretion. Further studies should be designed to dissect the unique functions played by various zinc transporters with respect to regulating β-cell function.

Figure 6.

Schematic model depicting the proposed role of Slc39a5 in pancreatic β-cells. An appropriate level of intracellular zinc is required for glucose-stimulated ATP synthesis and insulin secretion (left). Slc39a5 deficiency (right) results in impaired glucose-stimulated zinc uptake, Sirt1-Pgc-1α signaling, Glut2 expression, ATP synthesis and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

Materials and methods

Generation of Slc39a5fl/fl mice, breeding and genotyping

Slc39a5-floxed (Slc39a5fl/fl) mice containing LoxP sites flanking exon 4 in the Slc39a5 gene (Shanghai Biomodel Organism Science & Technology Development Co. Ltd) were crossed with Ins2-Cre (Postic et al., 1999) and CMV-Cre(Schwenk et al., 1995) mice to generate β-cell-specific Slc39a5 knockout (Slc39a5fl/fl;Ins2-Cre+) and global Slc39a5 knockout (Slc39a5−/−) mice, respectively. All mice were kept on the C57BL/6 background. Detailed breeding strategies for generating conditional and global knockout mice were shown in Fig. S2. Tail biopsies were analyzed by genomic polymerase chain reaction (forward primer, CCTCTCACACCAACTGCTCA; reverse primer, AGCTTTGTCTGCCACCTTGT), and 3 different sizes of PCR products, including 735 bp, 959 bp and 528 bp represent wild-type, floxed and knockout alleles for Slc39a5 gene, respectively. A 350 bp PCR product was generated for Cre gene (forward, ATTTGCCTGCATTACCGGTC; reverse, ATCAACGTTTTCTTTTCGG).

Animal studies and high-fat diet

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Zhejiang University and were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for animal care. Leptin mutant (ob/ob, Stock No: 000632) and leptin receptor mutant (db/db, Stock No: 000697) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Most of the experimental mice were 3–6 months of age (with an exception in Fig. S4, 2 and 12 months old mice were applied for GTT) and were housed in plastic cages at a constant ambient temperature under a 12 h/12 h light-dark cycle. The mice were supplied with distilled water and pelleted AIN-76A (Research Diets, New Brunswick, NJ) chow containing standard fat content (12% kcal derived from fat). High-fat diet used in this study was purchased from Research Diets (cat# D12492) with 60% kcal derived from fat (2,205 kcal from lard per 4,057 kcal in diet).

Reagents

HEPES sodium salt, HEPES, potassium chloride, calcium chloride dihydrate, D-(+)-glucose, collagenase V, insulin, rosiglitazone, ZnCl2, ZnSO4 and TPEN (an intracellular membrane-permeable chelator for various ions, including zinc) were purchased from Sigma (Saint Louis, MO). Total OXPHOS Rodent WB was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA). The Dual Luciferase Assay Kit was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). Fluo-4 AM, cell-permeant Rhodamine 123 and 2-NBDG were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). SRT1720 and ZLN005 were purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX). The zinc detection kit was purchased from Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, JS, China).

Metabolic assays

The GTT, GSIS and insulin tolerance test (ITT) were conducted as described previously (Wang et al., 2011). For GTT and GSIS, the mice were fasted for 8 h and then injected i.p. with 1 g/kg body weight of glucose. For ITT, the mice were fasted for 2 h and then injected i.p. with 0.5 units/kg body weight of insulin. For blood glucose measurements, blood was drawn from the tail vein at the indicated times, and blood glucose was measured using an Accu-Check glucometer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). To measure plasma insulin, blood was collected from the retro-orbital plexus; the plasma was isolated, and plasma insulin was measured using a rat/mouse insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit with mouse insulin as the standard (Crystal Chem, Downers Grove, IL).

Pancreatic islet isolation and dissociation

Pancreatic Langerhans’ islets were isolated from individual (fasted overnight for 8 h) mice for different treatments and GSIS tests. Isolation and culture islets were performed as previously described (Wang et al., 2011). Briefly, Langerhans’ islets were isolated from the mice using a standard procedure with minor modifications (Gotoh et al., 1985; Hansen et al., 2012). Pancreas was inflated with 2 mg/mL collagenase V (Sigma) solution, excised, and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C in a water bath for full digestion. Islets were then hand-picked to remove all exocrine tissues. Isolated islets were recovered in RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 5.5 mmol/L glucose and 10% fetal bovine serum for 2 h before designated treatments. To obtain dissociated cells, pancreatic islets were incubated in 0.125% dispase II (Roche Diagnostics) for 5 min at 37 °C with occasional gentle mixing. The cells were then plated on glass coverslips precoated with poly-L-lysine solution (Sigma) and used for culture, staining and/or treatment.

Measurements of mRNA and protein levels

Islet mRNA and protein levels were analyzed as described previously (Wang et al., 2014b). Total RNA was extracted from islets using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using Super Script III reverse transcriptase, RNase-OUT Ribonuclease Inhibitor, and Oligo(dT)12–18 (Invitrogen). Relative mRNA levels were determined using the LightCycler 480 II system (Roche) with the primers listed in Table S1. Islet samples used for Western blot analysis were homogenized in phosphate buffer (50 mmol/L, pH 7.4) containing 0.1% Triton X-100 and protease inhibitor cocktail. A total of 10 μg of protein per lane was used for Western blot analysis. The membranes were first incubated with the respective primary antibodies (rabbit anti-Glut2, anti-Pdx1, or anti-Ucp2; Millipore, Billerica, MA), followed by an anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Gapdh was used as a loading control (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA).

Insulin content and islet morphology

Insulin content, islets number and β-cell mass were determined as described previously (Wang et al., 2008). Briefly, total pancreatic insulin concentration was determined (n = 6 mice per genotype) using the insulin enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Crystal Chem) after acid-ethanol extraction. Islets number was counted (n = 9 mice per genotype) using microscope for hand-picked islets from each mouse after full digestion with collagenase V as described above. For immunohistochemistry assay, tissues were fixed in 4% PFA for 30 min at 4 °C, embedded in paraffin, and 8-mm sections were cut, affixed to glass slides, and stained with antibodies. Pancreatic β-cell mass was determined by immunostaining of paraffin-embedded pancreatic sections (n = 3 mice × 3 slides per genotype) with a rabbit anti-insulin primary antibody (Abcam), and was quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, ML).

2-NBDG uptake test

Dissociated pancreatic islet cells were incubated for 30 min in 20 mmol/L 2-NBDG (ThermoFisher Scientific) in Krebs-Henseleit buffer and measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (Arya et al., 2012).

ATP/ADP ratio

The ATP/ADP ratio was measured using an ATP/ADP ratio assay kit (Abcam) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Gray et al., 2011).

Luciferase assay

The luciferase assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using a luminometer (Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA).

Transmission electron microscopy

Transmission electron microscopy was performed using a Tecnai 10 microscope (FEI, Hillsboro, OR) at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility, Zhejiang University.

Statistical analysis

Except where indicated otherwise, summary data are presented as the mean ± SEM. The Student’s t-test was used to compare two groups. Multiple groups were compared using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test. Differences with a P-value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Wang and Min laboratories for helpful discussions. This study was supported by research grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31600953 to X. Wang; 31530034 and 31330036 to F. Wang; 31570791 and 91542205 to J. Min), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0507801 to J. Min and 2018YFA0507802 to F. Wang), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LQ15C110002 to X. Wang and LZ15H160002 to J. Min) and the Nation Science and Technology Major Projects for Major New Drugs Innovation and Develop 2017ZX09101-005-004-002 (L. Chen).

Abbreviations

ARE, antioxidant responsive element; CKO, Slc39a5fl/fl;Ins2-Cre+; Creb1, cAMP responsive element binding protein 1; Gck, glucokinase; Glut2, glucose transporter type 2; GR, glucocorticoid receptor; GSIS, glucose-stimulated insulin secretion; GTT, glucose tolerance test; HFD, high-fat diet; Ins1, preproinsulin 1; Ins2, preproinsulin 2; ITT, insulin tolerance test; Kir6.2, potassium inwardly rectifying channel, subfamily J, member 11; MRE, metal responsive element; Mtf1, metal response element binding transcription factor 1; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; Nfe2l1, nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2,-like 1; Nfe2l2, nuclear factor, erythroid derived 2, like 2; Pgc-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha; Ppar-γ, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma; Sirt1, NAD-dependent deacetylase sirtuin-1; Slc30a, zinc efflux transporters; Slc39a, Zrt- and Irt-like proteins; STD, standard chow diet; Sur1, ATP-binding cassette, sub-family C (CFTR/MRP), member 8; T2D, type 2 diabetes; TPEN, N,N,N’,N’-Tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine; Ucp2, uncoupling protein 2; WNT, wingless-type MMTV integration site.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Xinhui Wang, Hong Gao, Wenhui Wu, Enjun Xie, Yingying Yu, Xuyan He, Jin Li, Wanru Zheng, Xudong Wang, Xizhi Cao, Zhuoxian Meng, Ligong Chen, Junxia Min and Fudi Wang declare that they have no conflict of interest. All institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals were followed.

Author Contributions

X. Wang, H. Gao, J. Min and F. Wang designed experiments and; X. Wang, H. Gao, W. Wu, E. Xie, Y. Yu, X. He, J. Li, W. Zheng, X. Wang and X. Cao performed the experiments; X. Wang, J. Min and F. Wang analyzed data. X. Wang, H. Gao, L. Chen, Z. Meng, J. Min and F. Wang wrote the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ligong Chen, Email: ligongchen@tsinghua.edu.edu.

Junxia Min, Email: junxiamin@zju.edu.cn.

Fudi Wang, Email: fwang@zju.edu.cn.

References

- Arya A, Looi CY, Cheah SC, Mustafa MR, Mohd MA. Anti-diabetic effects of Centratherum anthelminticum seeds methanolic fraction on pancreatic cells, beta-TC6 and its alleviating role in type 2 diabetic rats. J Ethnopharmacol. 2012;144:22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashcroft FM, Rorsman P. Diabetes mellitus and the beta cell: the last ten years. Cell. 2012;148:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhat A, Koul A, Rai E, Sharma S, Dhar MK, Bamezai RN. PGC-1alpha Thr394Thr and Gly482Ser variants are significantly associated with T2DM in two North Indian populations: a replicate case-control study. Hum Genet. 2007;121:609–614. doi: 10.1007/s00439-007-0352-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chand S, McKnight AJ, Shabir S, Chan W, McCaughan JA, Maxwell AP, Harper L, Borrows R. Analysis of single nucleotide polymorphisms implicate mTOR signalling in the development of new-onset diabetes after transplantation. BBA Clin. 2016;5:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.bbacli.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimienti F. Zinc, pancreatic islet cell function and diabetes: new insights into an old story. Nutr Res Rev. 2013;26:1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0954422412000212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz M, Valladares-Salgado A, Garcia-Mena J, Ross K, Edwards M, Angeles-Martinez J, Ortega-Camarillo C, de la Pena JE, Burguete-Garcia AI, Wacher-Rodarte N, et al. Candidate gene association study conditioning on individual ancestry in patients with type 2 diabetes and metabolic syndrome from Mexico City. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2010;26:261–270. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y, Guo T, Traurig M, Mason CC, Kobes S, Perez J, Knowler WC, Bogardus C, Hanson RL, Baier LJ. SIRT1 is associated with a decrease in acute insulin secretion and a sex specific increase in risk for type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians. Mol Genet Metab. 2011;104:661–665. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellmann L, Nascimento AR, Tibirica E, Bousquet P. Murine models for pharmacological studies of the metabolic syndrome. Pharmacol Ther. 2013;137:331–340. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franklin I, Gromada J, Gjinovci A, Theander S, Wollheim CB. Beta-cell secretory products activate alpha-cell ATP-dependent potassium channels to inhibit glucagon release. Diabetes. 2005;54:1808–1815. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiser J, De Lisle RC, Andrews GK. The zinc transporter Zip5 (Slc39a5) regulates intestinal zinc excretion and protects the pancreas against zinc toxicity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e82149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh M, Maki T, Kiyoizumi T, Satomi S, Monaco AP. An improved method for isolation of mouse pancreatic islets. Transplantation. 1985;40:437–438. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198510000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JP, Eisen T, Cline GW, Smith PJ, Heart E. Plasma membrane electron transport in pancreatic beta-cells is mediated in part by NQO1. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;301:E113–E121. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00673.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyulkhandanyan AV, Lee SC, Bikopoulos G, Dai F, Wheeler MB. The Zn2+-transporting pathways in pancreatic beta-cells: a role for the L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9361–9372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508542200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JB, Tonnesen MF, Madsen AN, Hagedorn PH, Friberg J, Grunnet LG, Heller RS, Nielsen AO, Storling J, Baeyens L, et al. Divalent metal transporter 1 regulates iron-mediated ROS and pancreatic beta cell fate in response to cytokines. Cell Metab. 2012;16:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy AB, Prentice KJ, Froese S, Liu Y, Andrews GK, Wheeler MB. Zip4 mediated zinc influx stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic beta cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0119136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Tepaamorndech S. The SLC30 family of zinc transporters - a review of current understanding of their biological and pathophysiological roles. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:548–560. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Yan M, Kirschke CP. Over-expression of ZnT7 increases insulin synthesis and secretion in pancreatic beta-cells by promoting insulin gene transcription. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2630–2643. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel KP, Dickie MM, Coleman DL. Diabetes, a new mutation in the mouse. Science. 1966;153:1127–1128. doi: 10.1126/science.153.3740.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingalls AM, Dickie MM, Snell GD. Obese, a new mutation in the house mouse. J Hered. 1950;41:317–318. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jhered.a106073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong J, Eide DJ. The SLC39 family of zinc transporters. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:612–619. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bai S, Sheline CT. hZnT8 (Slc30a8) transgenic mice that overexpress the R325W polymorph have reduced islet Zn2+ and proinsulin levels, increased glucose tolerance after a high-fat diet, and altered levels of pancreatic zinc binding proteins. Diabetes. 2017;66:551–559. doi: 10.2337/db16-0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YV. Zinc and insulin in pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrine. 2014;45:178–189. doi: 10.1007/s12020-013-0032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S, Thomas TC, Storlien LH, Huang XF. Development of high fat diet-induced obesity and leptin resistance in C57Bl/6J mice. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:639–646. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Del Guerra S, Lupi R, Ronn T, Granhall C, Luthman H, Masiello P, Marchetti P, Groop L, Del Prato S. Epigenetic regulation of PPARGC1A in human type 2 diabetic islets and effect on insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 2008;51:615–622. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0916-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Batchuluun B, Ho L, Zhu D, Prentice KJ, Bhattacharjee A, Zhang M, Pourasgari F, Hardy AB, Taylor KM, et al. Characterization of zinc influx transporters (ZIPs) in pancreatic beta cells: roles in regulating cytosolic zinc homeostasis and insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18757–18769. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.640524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postic C, Shiota M, Niswender KD, Jetton TL, Chen Y, Moates JM, Shelton KD, Lindner J, Cherrington AD, Magnuson MA. Dual roles for glucokinase in glucose homeostasis as determined by liver and pancreatic beta cell-specific gene knock-outs using Cre recombinase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:305–315. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.1.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pound LD, Sarkar SA, Benninger RK, Wang Y, Suwanichkul A, Shadoan MK, Printz RL, Oeser JK, Lee CE, Piston DW, et al. Deletion of the mouse Slc30a8 gene encoding zinc transporter-8 results in impaired insulin secretion. Biochem J. 2009;421:371–376. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter GA, Chabosseau P, Bellomo EA, Maret W, Mitchell RK, Hodson DJ, Solomou A, Hu M. Intracellular zinc in insulin secretion and action: a determinant of diabetes risk? Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:61–72. doi: 10.1017/S0029665115003237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saxena R, Voight BF, Lyssenko V, Burtt NP, de Bakker PI, Chen H, Roix JJ, Kathiresan S, Hirschhorn JN, Daly MJ, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies loci for type 2 diabetes and triglyceride levels. Science. 2007;316:1331–1336. doi: 10.1126/science.1142358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk F, Baron U, Rajewsky K. A cre-transgenic mouse strain for the ubiquitous deletion of loxP-flanked gene segments including deletion in germ cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:5080–5081. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.24.5080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DA, Fisher AM. The insulin and the zinc content of normal and diabetic pancreas. J Clin Investig. 1938;17:725–728. doi: 10.1172/JCI101000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sladek R, Rocheleau G, Rung J, Dina C, Shen L, Serre D, Boutin P, Vincent D, Belisle A, Hadjadj S, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies novel risk loci for type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2007;445:881–885. doi: 10.1038/nature05616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondergaard LG, Stoltenberg M, Doering P, Flyvbjerg A, Rungby J. Zinc ions in the endocrine and exocrine pancreas of zinc deficient rats. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:619–625. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang X, Shay NF. Zinc has an insulin-like effect on glucose transport mediated by phosphoinositol-3-kinase and Akt in 3T3-L1 fibroblasts and adipocytes. J Nutr. 2001;131:1414–1420. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.5.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F, Kim BE, Petris MJ, Eide DJ. The mammalian Zip5 protein is a zinc transporter that localizes to the basolateral surface of polarized cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51433–51441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408361200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Lei XG, Wang J. Malondialdehyde regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in murine islets via TCF7L2-dependent Wnt signaling pathway. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2014;382:8–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Vatamaniuk MZ, Roneker CA, Pepper MP, Hu LG, Simmons RA, Lei XG. Knockouts of SOD1 and GPX1 exert different impacts on murine islet function and pancreatic integrity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:391–401. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Yun JW, Lei XG. Glutathione peroxidase mimic ebselen improves glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in murine islets. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20:191–203. doi: 10.1089/ars.2013.5361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XD, Vatamaniuk MZ, Wang SK, Roneker CA, Simmons RA, Lei XG. Molecular mechanisms for hyperinsulinaemia induced by overproduction of selenium-dependent glutathione peroxidase-1 in mice. Diabetologia. 2008;51:1515–1524. doi: 10.1007/s00125-008-1055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wijesekara N, Dai FF, Hardy AB, Giglou PR, Bhattacharjee A, Koshkin V, Chimienti F, Gaisano HY, Rutter GA, Wheeler MB. Beta cell-specific Znt8 deletion in mice causes marked defects in insulin processing, crystallisation and secretion. Diabetologia. 2010;53:1656–1668. doi: 10.1007/s00125-010-1733-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Mo X, Chen S, Lu X, Gu D. Association of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PPARGC1A) gene polymorphisms and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2011;27:177–184. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.