Abstract

Objectives:

Examine the effects of maturation on single leg jumping performance in elite male youth soccer players.

Design:

Cross sectional.

Setting:

Academy soccer clubs.

Participants:

347 male youth players classified as either pre, circa or post-peak height velocity (PHV).

Main outcome measures:

Single leg countermovement jump (SLCMJ) height, peak vertical landing forces (pVGRF), knee valgus and trunk side flexion.

Results:

Vertical jump height and absolute pVGRF increased with each stage of maturation (p < 0.001; d = 0.85–2.35). Relative to body weight, significantly higher landing forces were recorded on the left leg in circa versus post-PHV players (p < 0.05; d = −0.40). Knee valgus reduced with maturation but the only notable between-group differences were shown in post-PHV players (p < 0.05; d = 0.67); however, greater ipsilateral lateral trunk flexion angles was also present and these differences were significantly increased relative to circa-PHV players (p < 0.05; d = 0.85).

Conclusion:

Periods of rapid growth are associated with landing kinetics which may heighten injury risk. While reductions in knee valgus were displayed with maturation; a compensatory strategy of greater trunk lateral flexion was evident in post-PHV players and this may increase the risk of injury.

1. Introduction

The sport of soccer places significant physical and physiological demands on youth athletes (Buchheit, Mendez-Villanueva, Simpson, & Bourdon, 2010), and thus, an inherent risk of injury is present (Price, Hawkins, Hulse, & Hodson, 2004). The highest incidence of injury has been shown in older players (Price et al., 2004; Read, Oliver, de Ste Croix, Myer, & Lloyd, 2017); however, elevated risk has also been indicated during periods of accelerated growth (Read, Oliver, Croix, Myer, & Lloyd, 2016; Read, Oliver, de Ste Croix, et al., 2018; van der Sluis et al., 2014). This could be attributed to a temporary reduction in motor control which is characterized by a reduced ability to effectively control limb motion and complete athletic tasks (Philippaerts et al., 2006). As movement strategies are influenced by physical maturation, assessments of ecologically valid sporting actions that involve force attenuation and control are warranted to examine potential changes in injury risk at different stages of physical development.

Kinematic assessments have been used as a clinical tool to aid in the identification of non-contact knee injury risk factors (Hewett et al., 2005; Myer, Ford, Khoury, Succop, & Hewett, 2010; Paterno et al., 2010; Read, Oliver, de Ste Croix, Myer, & Lloyd, 2016; Read, Oliver, Croix, Myer, & Lloyd, 2017). Medial frontal plane motion of the knee during landing places a large amount of force on the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) (Yu & Garrett, 2007). In addition, maintenance of trunk control plays a crucial role in reducing forces occurring at the knee and subsequent risk of lower body injury (Hewett & Myer, 2011). Specifically, the combination of knee valgus and ipsilateral trunk frontal plane motion has shown greater sensitivity in prospectively identifying female games players at greater risk of non-contact knee injury than knee valgus alone (Dingenen et al., 2015).

In recreational youth athletes, the magnitude of knee valgus appears to be influenced by the stage of maturation (Schmitz, Shultz, & Nguyen, 2009). Reductions in valgus alignment are evidenced in boys as they mature (Read, Oliver, Croix, et al., 2018; Schmitz et al., 2009; Swartz, Decoster, Russell, & Croce, 2005). Conversely, Barber-Westin et al. (Barber-Westin, Noyes, & Galloway, 2006) showed no significant differences in landing kinematics based on chronological age in males aged 9–17. Chronological age does not account for the variation in biological maturity of players in the same age group, who may be at different stages of maturation (Malina, Bouchard, & Bar-Or, 2004). The existing literature has focused largely on the kinematics of the knee joint during landing tasks in youth athletes, but less is known about the effects of maturation on trunk control.

In addition to the assessment of kinematics during jumping assessments, poor attenuation of ground reaction forces upon landing may also heighten injury risk in youth soccer players. The existing literature indicates a concomitant reduction in landing forces with the later stages of maturation in male youth basketball players (Quatman, Ford, Myer, & Hewett, 2006). Furthermore, Sigward et al. (Sigwardet al, 2012) reported large increases in knee and hip moments during periods of rapid growth. However, these studies utilized non-elite participants and bilateral drop vertical jump landing tasks (Ford, Shapiro, Myer, van den, & Hewett, 2010; Hewett & Myer, 2011; Quatman et al., 2006; Sigwardet al, 2012). Single leg jump-landing assessments display greater ecological validity for soccer players and may be more suitable for identifying youth athletes who display landing mechanics that are indicative of a greater risk of injury (Yeow, Lee, & Goh, 2010).

Collectively, there is a paucity of data available to examine the effects of maturation on landing kinetics and kinematics in elite male youth soccer players despite the high frequency of lower extremity injuries. Coaches and practitioners would benefit from testing protocols that aid in the identification of players who demonstrate high risk movement patterns, from which targeted training programs can be implemented. The aim of this study was to examine possible maturation-related differences in unilateral landing mechanics using coach and clinician friendly diagnostics. It was hypothesized that improved landing mechanics would be displayed by players in the later stages of maturation; however, during periods of rapid growth, kinetic and kinematic deficits will be shown in players during this developmental stage.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental design

This study employed cross sectional design to examine the effects of maturity status on landing kinetics and kinematics in elite male youth soccer players. Participants completed one familiarization and one testing session separated by a period of seven days, each involving the performance of single leg counter-movement jumps (SLCMJ). Testing took place at each clubs respective training ground during the pre-season period of the 2015–2016 season. A standardized dynamic warm-up was completed before each test session. Participants were also instructed to wear shorts which clearly displayed their knees, avoid strenuous exercise for 48 h prior to testing, eat according to their normal diet and avoid eating and drinking substances other than water one hour prior to each test session.

2.2. Participants

Four hundred elite male youth soccer players (aged 10–18 years) registered at six professional academy soccer clubs in the United Kingdom volunteered to take part in this study. Descriptive statistics for each maturation group are displayed in Table 1. All players were required to be injury free at the time of testing and participating regularly in training and competing in accordance with the guidelines set out in the Premier League’s Elite Player Performance Plan (EPPP). Parental consent, participant assent and physical activity readiness questionnaires were collected prior to the commencement of testing. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Table 1.

Mean (s) values for participant details for each maturation group.

| Maturation group | N | Age (years) | Body mass (kg) | Stature (cm) | Leg length (cm) | Maturity offset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre PHV | 135 | 11.9 ± 1.1 | 39.7 ± 6.4 | 148.2 ± 7.5 | 74.6 ± 3.5 | −2.2 ± 0.6 |

| Circa PHV | 83 | 14.4 ± 0.9 | 51.8 ± 6.7 | 164.8 ± 7.6 | 82.3 ± 3.6 | 0.0 ± 0.3 |

| Post PHV | 129 | 16.1 ± 1.1 | 66.8 ± 8.0 | 176.6 ± 6.7 | 88.6 ± 4.7 | 2.0 ± 0.8 |

PHV = peak height velocity.

2.3. Procedures

2.3.1. Anthropometrics and biological maturation

Body mass (kg) was measured on a calibrated physician scale (Seca 786 Culta, Milan, Italy). Standing and sitting height (cm) were recorded to the nearest 0.1 cm on a measurement platform (Seca 274, Milan, Italy) with seated height measured using a box. Leg length was calculated as the difference between the players height in both standing and seated conditions. Biological maturation was estimated using a validated and non-invasive regression equation, which has shown to be accurate with a reported error of approximately 6 months (Mirwald, Baxter-Jones, Bailey, & Beunen, 2002).

Players were grouped into discrete bands according to their stage of maturation based on the number of years from peak height velocity (PHV) (pre-, circa- or post- PHV) as follows: (pre –PHV = <−1, circa-PHV = −0.5 to 0.5, post-PHV >1). Participants who recorded a maturational offset between −1 and −0.5 and 0.5 to 1 were subsequently removed from the data set to account for the reported error in the regression equation (Mirwald et al., 2002); the final sample consisted of three hundred and fourty seven players.

2.4. Single leg countermovement jump

Participants were instructed to stand on one leg in the centre of a force plate with their hands placed on their hips and the opposite hip and knee flexed at 90°. Players then performed a counter-movement to a self-selected depth followed immediately by a maximal effort vertical jump, landing on the same leg and holding a stable position for a period of five seconds (Read et al., 2016c). Three jumps on each leg were completed in a randomized and counter-balanced order with a one-minute rest period between each maximal effort.

2.5. Kinetics and kinematics

Peak vertical ground reaction force (pVGRF) was measured using a force platform (Pasco, Roseville, California, USA) and values were normalized to body weight to allow for between group comparisons. All data were recorded at a sampling rate of 1000 Hz and filtered through a fourth-order Butterworth filter at a cut-off frequency of 18 Hz. The reliability of these measures has been reported previously and deemed acceptable in this cohort (coefficient of variation (CV): 9.5–10% for post and pre-PHV players respectively) (Read et al., 2016c). Jump height was calculated in centimeters using the impulse–momentum method (Linthorne, 2001).

Kinematic data were recorded using 50 Hz Panasonic camcorders HC-V210 HD and HC-V720 HD (Panasonic UK Ltd. Berkshire, UK), positioned at a height of 70 cm and a triangulated distance of 5 m from the capture area in the frontal plane. Knee valgus was measured via the frontal plane projection angle which was calculated by measuring the angle drawn between the hip, knee and ankle joint centres (Noyes, Barber-Westin, Fleckenstein, Walsh, & West, 2005), where values less than 180° were indicative of knee valgus. Trunk side flexion was calculated on the contralateral side to the jumping leg by measuring the angle between two lines drawn from the anterior superior iliac spine, one directly vertical and one to the medial shoulder joint centre. A positive score was characteristic of ipsilateral trunk flexion. This method has been shown to optimize reliability in the assessment of lateral trunk movement during landing tasks (DiCesare, Bates, Myer, & Hewett, 2014). All angles were quantified at the point of maximal knee flexion using Kinovea 0.8.23 (Free Software Foundation, Boston, USA). Maximal knee flexion was determined as one frame before the participant started to increase knee extension in order to perform the maximum vertical jump.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each sub-group using Microsoft Excel® 2010. A one-way analysis of variance was performed in SPSS® (V.21. Chicago Illinois) to determine the existence of any between group differences for all outcome measures, with the level of significance set at p ≤ 0.05. Post-hoc analysis to determine significant between group differences was assessed using Gabriel’s or Games-Howell tests when equal variance was, or was not, assumed respectively. Cohen’s d effect sizes (ES) were calculated to interpret the magnitude of between group differences using the following classifications: standardized mean differences of 0.2, 0.5, and 0.8 for small, medium, and large effect sizes respectively (Cohen, 1992). The kinematic analysis was completed by one rater. Intra-rater reliability for both frontal plane projection and trunk lateral flexion angles was assessed using intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) on a sub-section of participants (N = 20). Two conduct the analysis, the rater viewed the same videos in a randomized order on two separate occasions, separated by a period of 7 days.

The estimation of sample size was calculated using equation (1) as suggested by Hopkins (2004). The highest predicted sample size for each test measure was N = 40. Therefore, sample sizes greater than this magnitude were deemed necessary to accurately determine any significant between-group differences for any outcome measure.

| (1) |

3. Results

3.1. Kinetics

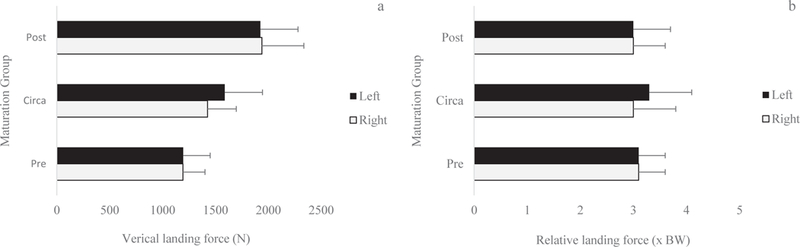

Vertical jump height (pre-PHV 10.93 ± 2.57 cm: circa-PHV 13.17 ± 2.65 cm; post-PHV 15.79 ± 2.87 cm) and absolute pVGRF (Fig. 1 a) increased linearly with each stage of maturation (p < 0.001; d = 0.85–2.35). Relative to body mass, significantly higher landing forces were recorded on the left leg in circa versus post-PHV players (p < 0.05; d = −0.40; Fig. 1 b). No other significant between-group differences were shown and effect sizes were trivial to small.

Fig. 1.

a – b. Vertical absolute (figure a) and relative (figure b) landing forces for each maturation group.

3.2. Kinematics

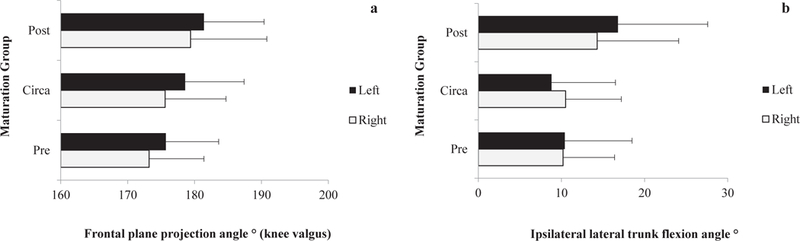

Intra-rater reliability was strong (ICC = 0.88 and 0.90) for frontal plane knee projection and trunk lateral flexion angles respectively. Frontal plane projection angles indicated a trend where the degree of knee valgus reduces with advancing maturation on both legs (Fig. 2 a). No between-group differences and small to moderate effect sizes were shown on the right leg (d = 0.28–0.62). On the left leg, significantly less valgus was indicated in post-PHV players when compared to those in the pre-PHV group (p < 0.05; d = 0.67). No other group comparisons were significant and effect sizes were small (d = 0.31–0.35).

Fig. 2.

a – b. Frontal plane projection angles (figure a) and lateral trunk flexion angles (figure b) for each maturation group.

Post-PHV players displayed greater lateral trunk flexion angles on both legs than all other groups (Fig. 2 b) and these differences were magnified when compared to the circa-PHV group on the left leg (p < 0.05; d = 0.85). No other group comparisons were significant and effect sizes were trivial to moderate (d = 0.05–0.67).

4. Discussion

The aim of the current study was to examine the effects of maturation on single leg vertical jumping and landing mechanics in elite male youth soccer players. Results showed that jump height and absolute pVGRF increased with each stage of maturation. Normalized to body mass, landing forces were higher in circa-PHV players. Knee valgus reduced with advancing maturation but significant differences were only evident between post-PHV and pre-PHV players for the left leg; however, this reduction in frontal plane knee motion was combined with greater ipsilateral lateral trunk flexion angles in the more mature cohort.

Greater absolute landing forces with advancing maturation are likely due to increases in body and muscle mass as indicated in Table 1. Relative values showed a more varied pattern with the only notable between-group difference in circa versus post-PHV players. Previous data indicate reduced ground reaction forces in older youth relative to bodyweight in bilateral landing tasks (Quatman et al., 2006; Swartz et al., 2005), suggesting that in the later stages of maturation, athletes are better able to attenuate landing forces. Conversely, younger children have been shown to land with reduced knee and hip flexion angles (Swartz et al., 2005), indicative of a ‘stiffer’ landing position resulting in heightened relative peak ground reaction forces (Swartz et al., 2005). Disparity between the findings of the current study and those of previous research may in part be explained by the difference in bilateral versus unilateral jumping tasks. Also, vertical jump height increased linearly with each stage of maturation. Greater vertical displacement of the centre of mass will challenge dynamic stability and the ability to dissipate landing forces. Poor attenuation of ground reaction forces upon landing in-spite of improvements in jump height may increase injury risk in youth players, especially in those who are older and possess greater stature and body mass.

Heightened normalized landing forces in circa-PHV players are consistent with previous research. Hewett et al. (Hewett, Myer, Ford, & Slauterbeck, 2006) showed that landing forces increased in male youth around the period associated with the peak growth spurt. Elevated normalized forces in the circa-PHV group in the current study may be indicative of an increased injury risk around the time of PHV. This maturity-related risk factor is a concept that has been previously reported in male youth soccer players (van der Sluis et al., 2014). In the current study, the most notable increases in limb length (as shown in Table 1) were shown between pre and circa-PHV players, and this may have resulted in temporary decrements in motor skill performance. It should also be noted that these differences were only evident during the SLCMJ on the left leg, and for the majority of the players this would be their dominant stance limb for kicking actions (274 out of 347 players (79%) stated their preferred kicking leg was the right). Repeated exposures to intensive training and competitions will expose these individuals to muscle loading patterns that asymmetrically strengthen the quadriceps (Iga, George, & Lees, 2009). Speculatively, the interaction of rapid growth and heightened training volumes which are required for elite male youth soccer players in the United Kingdom around this time (Read et al., 2016a; Read et al., 2017) may have resulted in under activation of hamstrings leading to a more quadriceps dominant landing strategy (Hewett et al., 2005) and subsequently players were exposed to higher ground reaction forces upon landing. These data highlight the importance of training interventions that focus on developing appropriate landing mechanics around the time of PHV.

Kinematic assessment showed reductions in knee valgus with advancing maturation which is consistent with previous research (Swartz et al., 2005; Yu & Garrett, 2007). Heightened strength levels occurring concomitantly with a more mature state could in part explain this trend (Schmitz et al., 2009). However, effective kinematics during jump-landing tasks are multifaceted; while heavily underpinned by strength, coordination, neuromuscular control, movement skill and anatomical alignment are also contributing factors that should be considered (Schmitz et al., 2009). In-spite of the observed reductions in knee valgus with progression towards a more mature state, post-PHV players appeared to utilize a strategy of increased lateral trunk flexion during landing. This was evident via an ipsilateral trunk lean towards the stance limb; a pattern that has been shown to heighten knee injury risk (Hewett & Myer, 2011; Zazulak, Hewett, Reeves, Goldberg, & Cholewicki, 2007), and associated with patellofemoral pain syndrome (Nakagawa, Moriya, Maciel, & Serrao, 2012). This is likely due to increases in the knee abduction moment and placement of the ground reaction force vector more lateral to the knee joint (Hewett & Myer, 2011).

A possible explanation for the increases in lateral trunk motion shown by more mature players in the current study could be the likelihood for increased incidence of ankle sprains, a frequent injury occurring in this cohort (Read et al., 2018). Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness is more prevalent following the occurrence of an inversion ankle sprain (Friel, McLean, Myers, & Caceres, 2006). Furthermore, when postural control can no longer be maintained by motion at the ankle, larger adjustments in the upper segments are required in those with functional ankle instability (Tropp & Odenrick, 1988). Alterations in joint motion should be considered in the context of a kinetic chain, characterized by a linkage of interdependent joints where movement at one joint will effect another occurring in series (Hewett & Myer, 2011; Myer, Chu, Brent, & Hewett, 2008). During actions such as landing where effective deceleration of the centre of mass requires maintenance of the athlete’s body mass over the lower extremity, ipsilateral trunk lean is an indication of a compensatory strategy for weakness in the hip abductors and lateral trunk stabilizers as the centre of mass is moved closer to the stance limb (Crossley, Zhang, Schache, Bryant, & Cowan, 2011). This is magnified during unilateral landing tasks, with research showing that in comparison to bilateral landings, a unilateral base of support increased lateral trunk flexion by 6–10° (Pappas, Hagins, Sheikhzadeh, Nordin, & Rose, 2007). Subsequently, the external moment arm and torque around the hip joint is reduced, decreasing the demand on the gluteus medius (Pappas et al., 2007). Thus, assessment and correction of lower limb control during unilateral tasks should consider both proximal and distal factors to maximize their effectiveness.

More pronounced lateral trunk motion in older players could also be due to increases in body mass and height of the centre of mass following periods of rapid growth, making effective neuromuscular control of the trunk more challenging (Myer et al., 2008). This will be further magnified by increases in jump height as shown with advanced maturation in the current study due to a greater velocity at impact. Of note, there is an increased risk of ligament sprain and a concomitant decrease in bone fractures with advanced maturation, which are likely due to increased body mass, with altered bony lever lengths influencing increased joint loads and greater intensities of play (Adrim & Cheng, 2003). While a neuromuscular spurt in strength has been indicated in boys following the onset of peak height velocity (Malina et al., 2004), measures of functional strength have reported weak relationships with the degree of valgus alignment during landing tasks in youth athletes (Schmitz et al., 2009).

When interpreting the results of this study, clinicians and coaches should be cognizant of the fact that the kinematic variables assessed during the SLCMJ were recorded using two-dimensional video capture. The gold standard for kinematic assessment is via three-dimensional motion analysis; however, this approach requires specialized equipment and labour intensive data collection, limiting the ability to effectively utilize this technique when screening large numbers of athletes. Subsequently, alternative time-efficient and non-invasive clinic-based methods have been proposed which correlate significantly with more sophisticated laboratory techniques (Myer et al., 2010). Due to the applied, field-based nature of this study and the large sample of participants, the use of two-dimensional analysis was deemed to have greater clinical utility.

The collective findings of the current study indicate that targeted neuromuscular training is required for male youth soccer players using a multi-faceted approach inclusive of movement reeducation, strength training, plyometrics, balance, motor control and coordination training to reduce injury risk in this cohort (Dingenen, Malfait, Vanrenterghem, Verschueren, & Staes, 2014; Hewett & Myer, 2011; Myer et al., 2008). To enhance their effectiveness, these interventions should commence pre-puberty and be maintained throughout a player’s growth and development with the aim of reducing injury risk during periods associated with rapid growth and advanced maturation when injury risk is heightened (Myer et al., 2011).

5. Conclusion

Cross-sectional SLCMJ data for a large sample of elite male youth soccer players are now available to assist practitioners by providing normative data for players at different stages of maturation, from which reduced performances and potential injury risk factors can be identified. Periods of rapid growth appear to be associated with landing kinetics indicative of heightened injury risk as shown be increased relative landing forces in circa-PHV players. When examining kinematic strategies, reductions in valgus were displayed with advancing maturation; however, a concomitant increase in trunk lateral flexion was evident in post-PHV players which could be considered a compensatory strategy to reduce the demand on the hip and trunk stabilizers. These data indicate that unilateral landing mechanics are effected by the stage of maturation. Also, knee valgus should not be monitored in isolation and measurement of trunk position during landing is also warranted to examine joint motion and control at different points along the kinetic chain.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Ethical statement

Parental consent, participant assent and physical activity readiness questionnaires were collected prior to the commencement of testing. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional ethics committee in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. All procedures were conducted in accordance with those stated to ensure ethical compliance at all time.

Ethical approval

This research was approved by the institutional ethics committee and subjects provided informed consent to the work Funding.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ptsp.2018.07.001.

References

- Adrim TA, & Cheng TL (2003). Overview of injuries in the young athlete. Sports Medicine, 33, 75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber-Westin SD, Noyes FR, & Galloway M (2006). Jump-land characteristics and muscle strength development in young athletes a gender comparison of 1140 athletes 9 to 17 years of age. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34, 375–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchheit M, Mendez-Villanueva A, Simpson BM, & Bourdon PC (2010). Match running performance and fitness in youth soccer. Int J Sports Med, 31, 818–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JA (1992). Power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley KM, Zhang WJ, Schache AG, Bryant A, & Cowan SM (2011). Performance on the single-leg squat task indicates hip abductor muscle function. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 39, 866–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiCesare CA, Bates NA, Myer GD, & Hewett TE (2014). The validity of 2-dimensional measurement of trunk angle during dynamic tasks. Int J Sports Phys Ther, 9, 420. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingenen B, Malfait B, Nijs S, Peers KHE, Vereecken S, Verschuren SMP, et al. (2015). Can two-dimensional video analysis during single-leg drop vertical jumps help identify non-contact knee injury risk? A one-year prospective study. Clinical Biomechanics, 30, 781–787. 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2015.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingenen B, Malfait B, Vanrenterghem J, Verschueren SM, & Staes FF (2014). The reliability and validity of the measurement of lateral trunk motion in two-dimensional video analysis during unipodal functional screening tests in elite female athletes. Physical Therapy in Sport, 15, 117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford KR, Shapiro R, Myer GD, van den BAJ, & Hewett TE (2010). Longitudinal sex differences during landing in knee abduction in young athletes. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 42, 1923–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friel K, McLean N, Myers C, & Caceres M (2006). Ipsilateral hip abductor weakness after inversion ankle sprain. Journal of Athletic Training, 41, 74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, & Myer GD (2011). The mechanistic connection between the trunk, knee, and anterior cruciate ligament injury. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews, 39, 161–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, et al. (2005). Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: A prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 33, 492–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, & Slauterbeck JR (2006). Preparticipation physical examination using a box drop vertical jump test in young athletes: The effects of puberty and sex. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 16, 298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins WG (2004). How to interpret changes in an athletic performance test. Sportscience, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Iga J, George K, & Lees A (2009). Cross-sectional investigation of indices of isokinetic leg strength in youth soccer players and untrained individuals. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 19, 714–719 ( ). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linthorne NP (2001). Analysis of standing vertical jumps using a force platform. American Journal of Physics, 69, 1198–1204. [Google Scholar]

- Malina RM, Bouchard C, & Bar-Or O (2004). Timing and sequence of changes during adolescence. In Growth, maturation and physical activity (pp. 307–333). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics. [Google Scholar]

- Mirwald RL, Baxter-Jones AD, Bailey DA, & Beunen GP (2002). An assessment of maturity from anthropometric measurements. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 34, 689–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer GD, Chu DA, Brent JE, & Hewett TE (2008). Trunk and hip control neuromuscular training for the prevention of knee joint injury. Clinics in Sports Medicine, 27, 425–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer GD, Faigenbaum AD, Ford KR, Best TM, Bergeron MF, & Hewett TE (2011). When to initiate integrative neuromuscular training to reduce sports-related injuries and enhance health in youth? Current Sports Medicine Reports, 10, 155–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myer GD, Ford KR, Khoury J, Succop P, & Hewett TE (2010). Development and validation of a clinic-based prediction tool to identify female athletes at high risk for anterior cruciate ligament injury. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38, 2025–2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa TH, Moriya ET, Maciel CD, & Serrao FV (2012). Trunk, pelvis, hip, and knee kinematics, hip strength, and gluteal muscle activation during a single leg squat in males and females with and without patellofemoral pain syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 42, 491–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD, Fleckenstein C, Walsh C, & West J (2005). The drop-jump screening test difference in lower limb control by gender and effect of neuromuscular training in female athletes. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 33, 197–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas E, Hagins M, Sheikhzadeh A, Nordin M, & Rose D (2007). Biomechanical differences between unilateral and bilateral landings from a jump: Gender differences. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 17, 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterno MV, Schmitt LC, Ford KR, Rauh MJ, Myer GD, Huang B, et al. (2010). Biomechanical measures during landing and postural stability predict second anterior cruciate ligament injury after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and return to sport. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 38, 1968–1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippaerts RM, Vaeyens R, Janssens M, Van Renterghem B, Matthys D, Craen R, et al. (2006). The relationship between peak height velocity and physical performance in youth soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 24, 221–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price RJ, Hawkins RD, Hulse MA, & Hodson A (2004). The football association medical research programme: An audit of injuries in academy youth football. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 38, 466–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quatman CE, Ford KR, Myer GD, & Hewett TE (2006). Maturation leads to gender differences in landing force and vertical jump performance: A longitudinal study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34, 806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read PJ, Oliver JL, Croix MD, Myer GD, & Lloyd RS (2016). Consistency of field-based measures of neuromuscular control using force-plate diagnostics in elite male youth soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30, 3304–3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read PJ, Oliver JL, De Ste Croix MBA, Myer GD, & Lloyd RS (2016). The scientific foundations and associated injury risks of early soccer specialization. Journal of Sports Sciences, 34 10.1080/02640414.2016.1173221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read PJ, Oliver JL, de Ste Croix MBA, Myer GD, & Lloyd RS (2016). Reliability of the tuck jump injury risk screening assessment in elite male youth soccer players. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 30, 1510–1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read PJ, Oliver JL, Croix MD, Myer GD, & Lloyd RS (2018). The effects of chronological age and stage of maturation on landing kinematics in elite male soccer players. Journal of Athletic Training, 53(4). 10.4085/1062-6050-493-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read PJ, Oliver JL, de Ste Croix MBA, Myer GD, & Lloyd RS (2018). An audit of injuries in six English professional soccer academies. Journal of Sports Sciences, 36(13), 1542–1548. 10.1080/02640414.2017.1402535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz RJ, Shultz SJ, & Nguyen AD (2009). Dynamic valgus alignment and functional strength in males and females during maturation. Journal of Athletic Training, 44, 26–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigward et al. , 2012.

- van der Sluis A, Elferink-Gemser MT, Coelho-e-Silva MJ, Nijboer JA, Brink MS, & Visscher C (2014). Sport injuries aligned to peak height velocity in talented pubertal soccer players. Int J Sports Med, 35, 351–355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz EE, Decoster LC, Russell PJ, & Croce RV (2005). Effects of developmental stage and sex on lower extremity kinematics and vertical ground reaction forces during landing. Journal of Athletic Training, 40, 9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp H, & Odenrick P (1988). Postural control in single-limb stance. Journal of Orthopaedic Research, 6, 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeow CH, Lee PVS, & Goh JCH (2010). Sagittal knee joint kinematics and energetics in response to different landing heights and techniques. The Knee, 17, 127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, & Garrett WE (2007). Mechanisms of non-contact ACL injuries. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 41, 47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zazulak BT, Hewett TE, Reeves NP, Goldberg B, & Cholewicki J (2007). Deficits in neuromuscular control of the trunk predict knee injury risk: A prospective biomechanical-epidemiologic study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 35, 1123–1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]