Abstract

Anaerobic ammonia oxidation (anammox) combined with partial nitritation (PN) is an innovative treatment process for energy-efficient nitrogen removal from wastewater. In this study, we used genome-based metagenomics to investigate the overall community structure and anammox species enriched in suspended growth (SGR) and attached growth packed-bed (AGR) anammox reactors after 220 days of operation. Both reactors removed more than 85% of the total inorganic nitrogen. Metagenomic binning and phylogenetic analysis revealed that two anammox population genomes, affiliated with the genus Candidatus Brocadia, were differentially abundant between the SGR and AGR. Both of the genomes shared an average nucleotide identify of 83%, suggesting the presence of two different species enriched in both of the reactors. Metabolic reconstruction of both population genomes revealed key aspects of their metabolism in comparison to known anammox species. The community composition of both the reactors was also investigated to identify the presence of flanking community members. Metagenomics and 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing revealed the dominant flanking community members in both reactors were affiliated with the phyla Anaerolinea, Ignavibacteria, and Proteobacteria. Findings from this research adds two new species, Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 and Ca. Brocadia sp. 2, to the genus Ca. Brocadia and sheds light on their metabolism in engineered ecosystems.

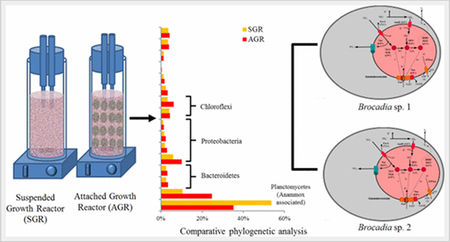

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

There is a need for energy neutrality and resource positivity in municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs). Subsequently, the wastewater community is being proactive as it embraces new treatment technologies that rely on minimum aeration and smaller carbon footprints. The anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process has evolved as a powerful process to address energy autarky and carbon footprints. The anammox process is the oxidation of ammonia to nitrogen gas with nitrite as an electron acceptor.(1, 2) When applied together with partial nitration, it reduces oxygen demand and organic carbon requirements.(3) Anammox provides a more-sustainable solution to the need for energy autarky and smaller carbon footprints of modern WWTPs than conventional aerobic nitrification and heterotrophic denitrification.(4) Within the past decade, wastewater practitioners have accelerated the adoption of anammox systems. Many full-scale anammox plants are already running successfully in Europe and Asia, while several are being constructed in the United States.

Engineering applications of the anammox process rely on strategies where ammonium (NH4 +–N) is partially oxidized to nitrite (NO2−–N) (nitritation) by ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB). Subsequently, anammox (AMX) bacteria oxidize the remaining NH4 +–N to nitrogen gas, using the formed NO2−–N as an electron acceptor.(5) When combined, nitritation and anammox are known as partial nitritation anammox (PN/A) systems. The success of PN/A systems depends on the synergy between AMX and AOB. Several PN/A configurations have been developed to achieve this synergy, including two-stage PN/A systems where nitritation and anammox occur in separate reactors(6, 7) or single-stage PN/A systems in which nitritation and anammox processes occur in a single reactor.(8) Additionally, different strategies have been used for biomass cultivation that encourage the community to either form highly organized granular structures (suspended growth) or to adhere to the plastic carrier media (attached growth).(9–14)

Appropriate microbial community assembly is a necessary step in successfully implementing PN/A systems. Consequently, understanding the microbial ecology of organisms living in PN/A systems has been the focus of many studies.(14–16) These studies have focused on analyzing the diversity of the microbial communities using phylogenetic markers such as the 16S rRNA gene(15) and the diversity of anammox organisms using sequence analyses of a primary anammox functional genes, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (HAO) and hydrazine synthase (HZS).(17–21) However, efforts have seldom focused on applying whole community metagenomics to study the function and diversity of microbial communities present in PN/A reactors.

Direct random shotgun sequencing of total DNA extracted from environmental samples (i.e., metagenomics), followed by functional and taxonomic analysis, can provide a higher resolution of microbial and anammox diversity in comparison to a phylogenetic marker gene-based approach.(22–28) To date, only two studies have used metagenomic approaches to investigate the microbial community structure of anammox reactors.(14, 16) This research provided information on key flanking communities and as well as on anammox bacteria in PN/A systems. The use of metagenomics helped to elucidate the differences in the overall microbial ecology in attached growth and suspended growth anammox systems as well as to study the overall functional gene repertoire in two laboratory scale anammox reactors operated for over 220 days. Possible metabolic pathways were constructed on the basis of the extracted anammox genomes from metagenomic sequencing data.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Reactor Setup, Operational Strategy, and Sampling Suspended Growth with Partially Nitrifying and Anammox Reactors

A suspended growth anammox reactor (SGR) has been in operation in Goel’s laboratory at the University of Utah for the past 6 years. The start-up seed for the reactor was received from an ongoing anammox reactor stationed at the City College of New York, which was reported to be enriched with Candidatus Brocadia fulgida.(29) The SGR has been fed with partially nitrified real reject water from an ongoing suspended growth nitritation reactor (S-PN). Details of both reactors (i.e., nitritation reactor and SGR) have been provided elsewhere.(5) Briefly, the SGR has a working volume of 4L with a hydraulic retention time (HRT) of 2 days, and a pH was maintained at 7.8 ± 0.3.

Attached Growth with Partially Nitrifying and Anammox Reactor

An attached growth packed-bed anammox reactor (AGR) was initiated at the University of Utah with seed from the ongoing SGR and fed with the partially nitrified effluent from an attached growth packed-bed nitritation reactor (A-PN). The A-PN reactor was seeded from the S-PN reactor. The AGR was filled with Bio-Balls (diameter of 2.54 cm and surface area of 88.9 cm2; Coralife, WI) as the biofilm support media. It had an effective pore volume of 4 L. Initially, diluted feed was used for the reactor system to establish healthy nitritation and anammox biofilm communities. The amount of nitrogen loading was gradually increased as the biofilm developed and the reactor performance improved. Anaerobic conditions in both anammox reactors (i.e., SGR and AGR) were maintained by continuously purging with a mixture of 95% nitrogen gas and 5% carbon dioxide. A schematic of the SGR and AGR setups, as well as their corresponding nitritation reactors, are included in Supplementary Figure 1. Influent and effluent samples were routinely collected, filtered (0.45 μm). These were analyzed for NH4+–N, NO2−–N and NO3−–N concentrations using HACH methods 10031 (salicylate method), 10020 (chromotropic acid method), and 8153 (ferrous sulfate method), respectively. Schematics of both suspended and attached growth PN/A systems are provided in Supplementary Figure 1.

2.2. DNA Extraction

Biomass sampling for genomic DNA extraction from SGR and AGR was performed when the total inorganic nitrogen (TIN) removal efficiency was consistently greater than 80%, and the reactors appeared to be at steady state. Approximately 2 g of biomass from each anammox reactor were collected aseptically and suspended in 500 μL of 1× TE buffer (Fisher Scientific). For the AGR, five Bioballs were taken out from the mid-depth of the reactor, and the biomass was aseptically scraped off using a sterile 1 mL pipet tip. The biomass collection procedure was repeated three times. DNA from each biomass sample was extracted using the PowerMax soil DNA isolation kit (MoBio Laboratories), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted triplicate DNA samples were mixed to create one homogenized single DNA sample. The concentration of DNA was measured with a Nanodrop 1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific), and the quality was verified by running the genomic DNA on a 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

2.3. Microbial Community Analysis Using 16S rRNA Gene-Based Sequencing

The overall bacterial community was obtained by sequencing 16S rRNA gene fragments through high-throughput amplicon sequencing as described by Kapoor et al.,(30) with some modifications. Specifically, barcoded PCR primers 515F/806R were used to partially amplify the 16S rRNA gene.(31) PCR conditions were adopted from Kapoor et al.(30) PCR products were visualized on an agarose gel and pooled in an equimolar ratio prior to sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA), using pair-end 250 bp kits at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital DNA Core facility.

A total of 101 192 and 38 537 of 16S rRNA partial gene sequences were obtained from both the SGR and AGR, respectively. Reads obtained were processed using the Quantitative Insights into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) version 1.8.0.(32) Paired-end MiSeq reads were first assembled using the FLASH version 1.2.11 with default parameters.(33) Sequences with a quality score less than 20 and ambiguous N bases were removed before chimera detection. Chimeric sequences were identified with QIIME via USEARCH and removed prior to taxonomic assignment.(34) Nonchimeric 16S rRNA gene sequences were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using UCLUST(35) with a 97% nucleotide similarity. Representative sequences from each cluster were queried against the SILVA 119 rRNA database,(36) using UCLUST(35) to assign taxonomy. Singleton OTUs (represented by one read only) were omitted from downstream analysis to reduce over prediction of rare OTUs.(37) Prior to analysis, data sets were normalized to the total number of reads per sample.

2.4. Whole-Community Metagenomics, Assembly, and Analysis

A total of 1 μg of genomic DNA from both the SGR and AGR reactors were submitted to the high-throughput sequencing core facility, Huntsman Cancer Institute (HCI) at the University of Utah. Genomic DNA was sequenced on a MiSeq sequencer (Illumina) to generate 300 nt paired-end reads. The raw reads obtained were quality filtered using Sickle version 1.33.(38) Reads were filtered using a minimum quality score of 20 with a minimum length of 100 bp. The quality filtered reads were interleaved using the shuffleSequences_fasta.pl Perl script from MetaVelvet.(39) A phylogenetic analysis of the metagenomes for high-resolution microbial community assemblages was generated using PhyloSift.(40) A set of 37 elite marker gene families, along with 16S, 18S rRNA genes, mitochondrial, eukaryotic-specific, and viral gene families, were used for classification. Assembly of interleaved reads for the AGR and SGR were performed using omega with an overlap length of 150 bp.(42) The contigs generated were binned into population genomes based on (a) differential coverage, (b) tetranucleotide frequency, and (c) single-copy marker genes analysis with MaxBin.(42) A pair of anammox genomes were recovered from both the SGR and AGR reactors. CheckM was used to assess the completeness and quality of each binned genome using collocated sets of marker genes that are a single copy but ubiquitous within a phylogenetic lineage.(43) Scaffolding of anammox genome contigs was performed by multidraft-based scaffolder (MeDuSa).(44) To identify the correct order and orientation of the contigs, five published draft anammox genomes available in the NCBI database were used as templates; (a) CandidatusBrocadia fulgida (PRJNA263557), (b) Candidatus Jettenia caeni (PRJDB68), (c) CandidatusBrocadia sinica (PRJDB103), (d) Candidatus Kuenenia stuttgartiensis (PRJNA16685), and (e) Candidatus Scalindua brodae (PRJNA262561). The rRNA and tRNA prediction for the anammox genomes were recovered from both reactors was performed using webMGA(45) and ARAGORN,(46) respectively. Annotation of the scaffolded genome bins was performed using Metapathways v2.0.(47)

To appraise the bins depicting anammox lineages enriched in the SGR and AGR reactors, phylogenetic classification was performed on the basis of hydrazine synthase among the five known genera of anammox bacteria; Ca. Brocadia, Ca. Kuenenia, Ca. Scalindua, Ca. Anammoxoglobus, and Ca. Jettenia. A maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree of the hzsA gene was constructed using MEGA 5 along with reference sequences of anammox bacteria.(48)Genome-wide average nucleotide identity (gANI), along with the alignment frequency (AF) between the anammox draft genomes recovered from SGR, AGR, and other available anammox genomes, were calculated using the microbial species identified (MiSI) method.(49)

The raw reads were deposited in the MG-RAST repository with ID 4537331.3 and 4537777.3 for the SGR and AGR metagenome, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). Additionally, DNA sequences from the SGR and AGR have been submitted to the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) repository with BioProject PRJNA343219.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Reactor Performance

The performances of suspended growth and attached growth partial nitritation reactors are shown in supplementary Figure 2 (panels a and b respectively). The average NH4+–N concentration in the influent of the suspended growth partial nitritation (S-PN) reactor was 1260 ± 120 mg/L (supplementary Figure 2a). The reactor was able to produce an influent for SGR with 570 ± 60 mg/L of NH4+–N and 690 ± 70 mg/L of NO2−–N, yielding an NO2−-to-NH4+ ratio of 1.24 ± 0.09. On the other hand, NH4+–N in the influent was gradually increased from an initial concentration of 120 mg/L to a final concentration of 920 mg/L in the attached growth partial nitritation (A-PN) reactor (supplementary Figure 2b). At the highest NH4+–N influent concentration, the resulting NO2−–N/NH4+–N ratio in the effluent of the A-PN reactor was 1.07. Effluent from each partial nitritation reactor was fed to respective anammox reactor counterpart. Hence, under the steady-state conditions, both S-PN and A-PN reactors enabled the required ratio of nitrite and ammonium needed for anammox bacteria in SGR and AGR reactors.

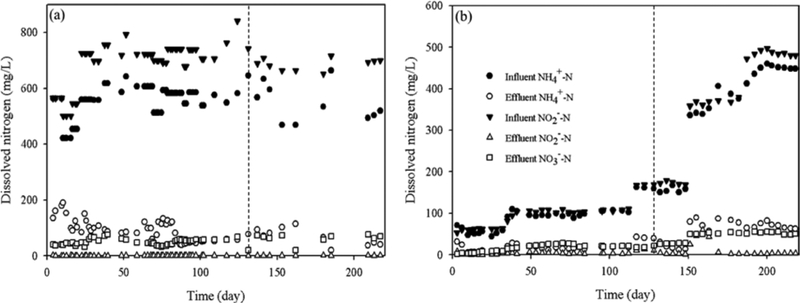

During the 220-day operation, the SGR consistently removed more than 85% total inorganic nitrogen (TIN), as shown in Figure 1a. The average NH4+–N, NO2−–N and NO3−–N in the effluent were 93.7 ± 45.8, 0.38 ± 0.30, and 51.3 ± 13.3 mg/L, resulting in an average 88 ± 2% TIN removal. The AGR, fed with the effluent from the attached growth partial nitritation (A-PN) reactor, did not initially have high biomass quantities so a step-feeding technique was adopted to ensure stable reactor operation. Figure 1b shows changes in NH4+–N, NO2−–N, and NO3−–N concentrations in the influent and effluent of the AGR. When the loading was increased, the N removal rate also increased steadily. The total inorganic nitrogen (TIN) removal efficiency was close to 80% on day 163. After day 169, the influent NH4+–N and NO2 −–N concentrations to the AGR were increased to 430 ± 30 and 460 ± 50 mg/L, respectively. A TIN removal of 86 ± 2% was observed during this phase. The nitrogen removal efficiencies observed in this study were like efficiencies observed by other researchers using anammox enrichment in sequencing batch reactors and membrane bioreactors. (1, 13, 50)

Figure 1.

Nitrogen concentration (NH4+–N, NO2––N, and NO3––N) in influent and effluent and the removal efficiency for anammox in (a) suspended growth and (b) attached growth reactor. The dotted line represents the day of biomass sampling, and the dotted line depicts the time (130th day) of biomass sampling for DNA extraction from SGR and AGR reactors.

3.2. Microbial Community in SGR and AGR Anammox Reactors Revealed by 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing

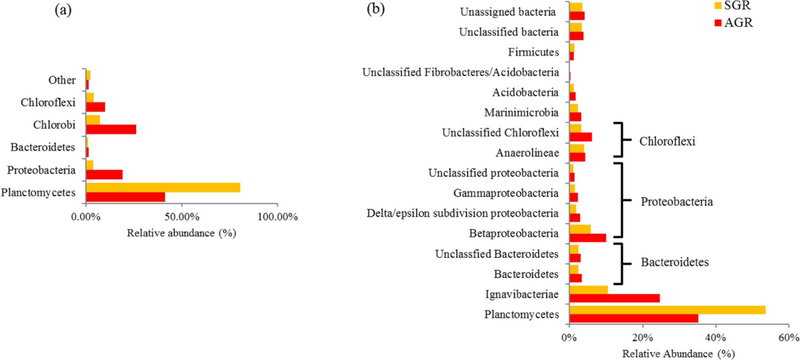

The purpose of 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing was to get a snapshot of the overall microbial community in both anammox reactors. 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing was performed to identify the microbial phylotypes in the SGR and AGR reactors. 16S rRNA gene being an excellent phylogenetic marker provides insight into the microbial taxa present in the sample. (31) When the 16S rRNA gene sequencing data were analyzed at the phylum level from both reactors (Figure 2a), Planctomycetes was the dominant phylum, with an abundance of 80.6% in SGR and 41.3% in AGR. Chlorobi accounted for 7.4% of total reads in SGR and 26.3% in AGR. Moreover, Proteobacteria in AGR was as high as 19.2% compared to 3.8% in SGR. The phyla Bacteroidetes and Chlorolipid were responsible for 1.4% and 4.3% of total reads for SGR and 1.7% and 10.0% for AGR, respectively. Because both reactors were highly enriched with anammox bacteria affiliated with the genus Brocadia, the genera level for the microbial communities was studied. The SGR was dominated by two genera: Ignavibacteria (Chlorobi) and Candidatus Brocadia (Planctomycetes), while in the AGR, an unclassified organism within the order Rhodocyclales (Proteobacteria), represented by Dok59 in the database, was detected with a relative abundance of 15.7%. The genus Ignavibacteria is classified within the phylum Chlorobi in Silva SSU r119. To compare the community diversity between both reactors (Table 1), Shannon, Chao1, and Simpson indices were calculated. On the basis of the results obtained, it could be concluded that the AGR harbored a more-diverse microbial community than the SGR.

Figure 2.

Taxonomic classification of QC filtered reads using (a) 16S itag sequencing and (b) PhyloSift (phylum and class).

Table 1.

Summary of 16S Sequencing Processing and Results

| sample name | total sequences | OTU counts | Shannon index | Chao1 | Simpson index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGR-Amplicon | 101192 | 2008 | 1.72 | 2501.8 | 0.595 |

| AGR-Amplicon | 15549 | 1301 | 2.83 | 2011.4 | 0.174 |

3.3. Microbial Community Analysis in Anammox Reactors Using Whole-Community Metagenomics

After obtaining information on the overall community structure using 16S rRNA gene amplicon sequencing, “deep” metagenomic sequencing using representative DNA samples from both reactors was employed to obtain a genome-scale view of the microbial community. This allowed for the examination of the functional potential of each reactor community and extract nearly complete genomes of key anammox lineages present in both SGR and AGR reactors. The metagenomes of SGR and AGR provides insight into all the genes present in the representative community. (31)

The taxonomic compositions of quality filtered metagenomic reads from each reactor were analyzed using PhyloSift. (40) The analysis indicated the presence of anammox-associated Planctomycetes as the dominant phylum in both the SGR (54%) and AGR (35%) metagenomes (Figure 2b). These results were consistent with those obtained using 16S rRNA gene-based amplicon analysis (Figure 2a). The second-most-dominant phylum in both SGR and AGR was found to be the phylum Ignavibacteriae (11 and 25%, respectively). Taxonomic classification published by NCBI classifies Ignavibacteriae and Chlorobi as separate phyla, both belonging to the Bacteriodetes and Chlorobi group. The third-most-abundant phylum was Chloroflexi composed of unclassified Chloroflexi and Anaerolineae (7 and 10%). Class Beta-proteobacteria (6 and 10%) (Figure 2b) belonging to phylum Proteobacteria was the fourth most abundant in the reactors.

Bacteria belonging to the phylum Ignavibacteriae and class Anaerolineae are not yet completely understood, but they are thought to be polymer-degrading, fermentative anaerobes. (15) Ignavibacteriae was found to encode the respiratory nitrate reducatase (Nar) gene involved in denitrification. Therefore, presence of these bacteria as dominant taxa among the flanking community indicates that nitrate respiration coupled to organic carbon oxidation may be occurring in both reactors. Biomass degradation is most likely important for the overall reactor operation because hydrolysis of larger biomass components into smaller organic molecules may support denitrification activity of heterotrophic bacteria abundant in the system while recycling dead biomass and reducing sludge yields.(15, 51) In summary, 16S rRNA gene amplicon results obtained independently (Figure 2a) of the taxonomic information gathered from the whole community metagenomics showed a similar microbial composition (Figure 2b and Supplementary Figures 3 and 4).

Recovery of Anammox Draft Genomes

The ability to assemble metagenomic sequences into draft population-genomes allowed the investigation of the role that individual microbial lineages play in natural and engineered ecosystems. Anammox bacteria are currently classified with an interim taxonomic status of Candidatus and remain a challenge to get into pure culture. Therefore, it becomes imperative to recover more genome sequences of uncultivated prokaryotes to begin to understand their ecology and metabolism.

Metagenomic sequencing, assembly, (41) and binning (42) of assembled contigs yielded two high-quality draft anammox bacterial genomes (BROC1 and BROC2) with differential coverage in the SGR and AGR metagenomes. BROC1 and BROC2 were found to be 94.4% and 97.2% complete (Table 2), determined based on the number of single-copy marker genes present in each genome.(42) Contig scaffolding and genome reorganization yielded 75 and 13 contigs for BROC1 and BROC2, respectively, comparable to other anammox draft genomes.(16) The relative abundance for both anammox genomes present in each reactor was calculated using coverage data generated using MaxBin.(42) The relative abundance (%) of BROC1 was 56.1 and 15.8% for SGR and AGR, respectively; BROC2 had a relative abundance of 23.5% and 7.1% for AGR and SGR, respectively. This suggests that anammox bacteria are a significant fraction of the microbial community present in the SGR and AGR systems, consistent with 16S and raw metagenomic sequencing results (Figure 2a, b).

Table 2.

Quality of Anammox Bacterial Bins

| abundance | relative abundance (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| bin name | SGR | AGR | SGR | AGR | total marker | unique Marker | completeness | genome size (bps) | features (23S/16S/5SrRNA/tRNA) | GC content (%) |

| Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 | 263.51 | 82.05 | 56.1 | 15.8 | 113 | 101 | 94.40% | 4476597 | 2*/2*/1/55 | 44.9 |

| Ca. Brocadia sp. 2 | 33.18 | 122.45 | 7.1 | 23.43 | 109 | 104 | 97.20% | 3334435 | 1/1/1/48 | 42.2 |

Phylogeny of Anammox Draft Genomes

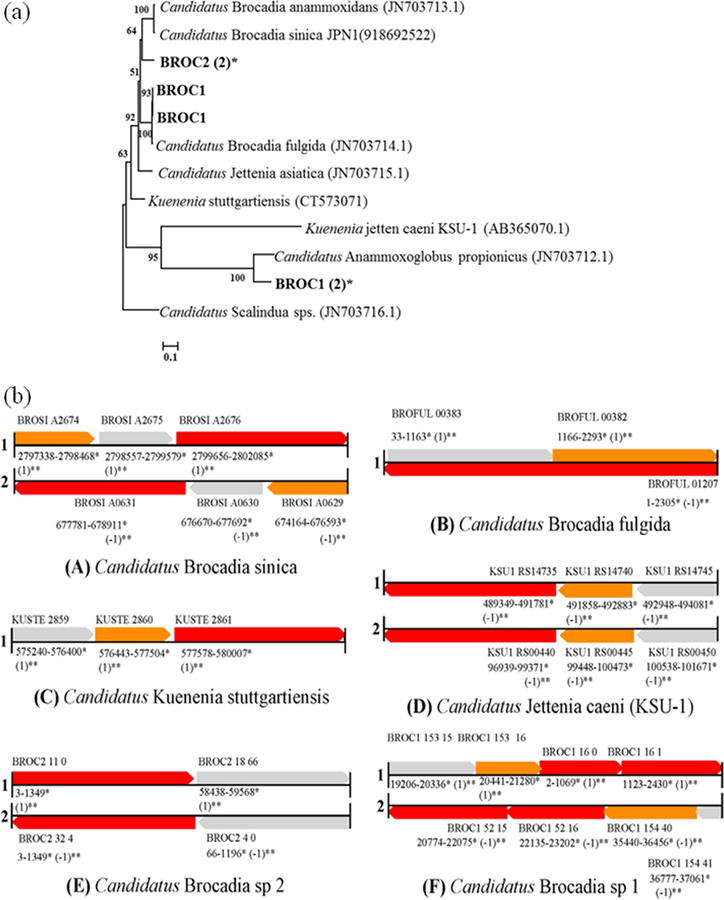

To assess the phylogenetic distance between all previously identified and characterized anammox species as well as the recovered anammox genomes from SGR and AGR, a functional gene-based marker approach was employed. Hydrazine synthase enzyme has been used to investigate the diversity of anammox organisms.(21) The central metabolic pathways of anammox organisms have been proposed by Katal et al.,(13) where nitrite is first reduced to nitric oxide (NO) by a cd1-type nitric oxide–nitrite oxidoreductase (nirS) in Kuenenia(24) and Scalindua.(23) Other anammox bacteria, such as Jettenia KSU-1, may employ a copper-based nirK-type nitrite reductase.(52, 53)Oshiki et al.(54, 55) suggested that the anammox species belonging to genus Ca. Brocadia (Ca. B. sinica and Ca. B. fulgida) may employ an unidentified nitrite reductase for NO2− reduction. This is due to the absence of both nirS and nirK genes in their genome. (55, 56) Hydrazine synthase enzyme is the most suitable biomarker to investigate the diversity of anammox organisms. (21, 28) Therefore, HzsA encoding genes were used to assess the phylogenetic relationship of the recovered anammox draft genomes by alignment with known hzsA genes (Figure 3a). A total of four copies of the hzsA gene from the BROC1 lineage aligned with 89, 89, 87, and 87% nucleotide identities to Ca. J. caenis, respectively. For the BROC2 lineage, both hzsA gene copies aligned with 86% identity to Ca. J. caeni.

Figure 3.

(A) Neighbor-joining trees indicating the phylogenetic relationships within the Brocadiales based on hydrazine synthase subunit A (HzsA) nucleotide sequences. ORFs from the BROC1 and BROC2 recovered from the SGR and AGR metagenome are highlighted in bold. Numbers of the nodes are percentages of bootstrap values based on 1000 replicates. NCBI accession numbers for the reference sequences have been mentioned in parentheses. (B) Gene diagram representing the syteny of hzsCBA gene cluster encoding for HZS enzyme among five anammox species (a) Ca. B. sinica, (b) Ca. B. fulgida, (c) Ca. K. stuttgartiensis, (d) Ca. J. caeni, (e) Ca. Brocadia sp 2, and (f) Ca′ Brocadia sp 1 recovered from SGR and SGR metagenome. Color represents each gene among the hzsCBA gene cluster (red, hzsA; orange, hzsB; gray, hzsC gene). A single asterisk represents the start and end position of the genes. Double asterisks represent the orientation (+) and (−) as (1) and (−1), respectively.

Phylogenetic analysis revealed two copies each of the hzsA gene encoded by BROC1 and BROC2 population genomes clustered within the genus Ca′ Brocadia genus. The third and fourth copies of hzsA gene from the BROC1 draft genome formed a separate cluster with Ca. Anammoxoglobus propionicus (JN703712.1) (Figure 3). This analysis suggests that both enriched BROC1 and BROC2 from SGR and AGR belong to the genus Ca. Brocadia. The organization and arrangement of the hzsCBA gene cluster was investigated to determine unifying themes among recovered and published anammox genomes. The synteny of the gene cluster neighborhood within each genome (57) was examined to reveal gene organization in genomes. Figure 3b represents the hzsCBA gene clusters of five anammox species (a) Ca. B. sinica, (b) Ca. B. fulgida, (c) Ca. K. stuttgartiensis, (d) Ca. J. caeni, (e) BROC2 (Ca. Brocadia sp. 2), and (f) BROC1 (Ca. Brocadia sp. 1) as well as anammox lineages recovered from the SGR and AGR metagenomes. For Ca. K. stuttgartiensis HZS, a heterotrimeric protein was encoded by kuste2859–2861 as hzsC, hzsB, and hzsA. (13, 24, 58) A similar organization of the hzsCBA gene cluster was also observed in Ca. J. caeni (two copies: forward and reverse), as well as in the Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 (two copies: forward and reverse). In the case of Ca. B. fulgida, the hzsCBA genes were not co-localized; hzsC and hzsB genes are on separate operons compared to the hzsA gene identified on the antisense strand (Figure 3b). We also observed that the Ca. B. sinica genome did not have syntenic regions for the gene cluster compared to other anammox genomes. Notably, in the Ca. Brocadia sp. 2 genome, only hzsA and hzsC genes were recovered, which may be a result of gaps in the draft genome.

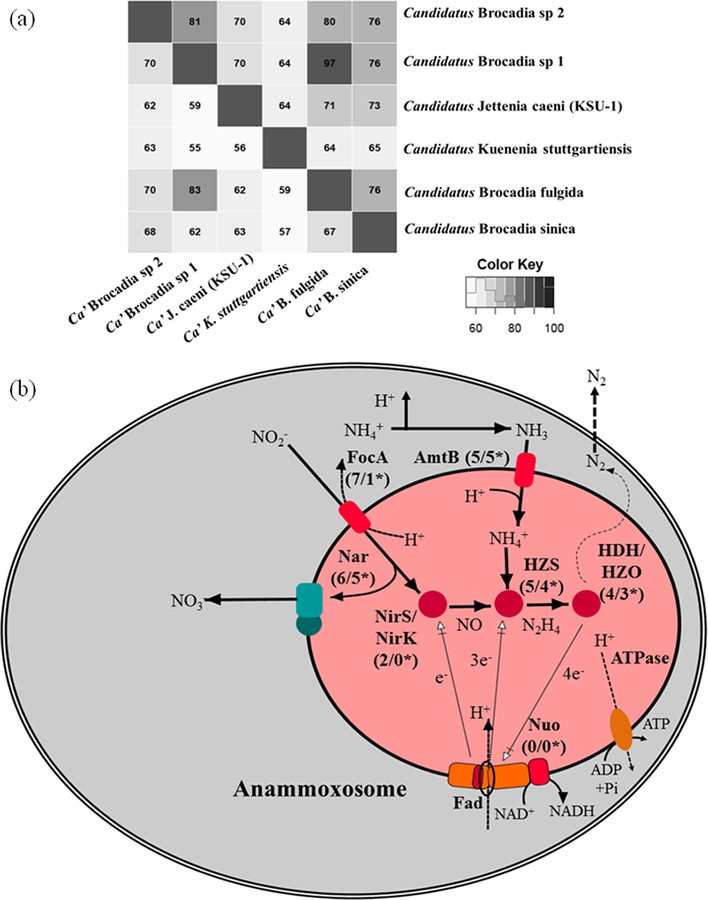

Taxonomic Classification of the Anammox Draft Genomes

Average nucleotide identity (gANI) of the whole genome has been proposed as an accurate means of comparing genetic relatedness among strains of interest.(59) A gANI of >~94% among strains corresponds to 70% DNA–DNA hybridization standard for species definition. Therefore, gANI combined with genome alignment fraction (AF) is useful for tentative taxonomic classification of Candidatus organisms,(49) including genomes recovered from metagenomes. For determining the taxonomic positions of the recovered anammox draft genomes from the SGR and AGR metagenomes, gANI with AF was performed against five published anammox genomes (Figure 4). gANI was calculated using BLASTn with a minimum of 30% sequence identity match over an alignment region of at least 70% for each genome length. The gANI and AF result reflects the relatedness of BROC1 and BROC2 genomes to Ca. B. fulgida followed by Ca. B. sinica. Based on the analysis performed, it is concluded that the BROC1 and BROC2 population genomes from the SGR and AGR are two different species belonging to the genus Ca. Brocadia. The relatedness between anammox lineage genomes from SGR and AGR were observed to be lower than 94%, suggesting an enrichment of two distinct species of anammox bacteria in different reactor configurations. Therefore, the results from the hzsA gene phylogenetic analysis, synteny, and gANI indicated that the anammox genomes (BROC1 and BROC2) recovered from SGR and AGR belong to the genus Ca. Brocadia, providing an increase in the diversity of anammox species known to date.

Figure 4.

(A) gANI, AF, and percent protein identification between all anammox genomes from public databases and Ca. Brocadia sp 1 and Ca.′ Brocadia sp 2 extracted from SGR and AGR metagenomes. (B) Overview of anammox metabolism of Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 and Ca. Brocadia sp. 2.

Anammox Catabolism

To judge the performance of anammox bioreactors, it is vital to understand the pathways involved in nitrogen removal by the anammox bacteria. Therefore, catabolic pathways of anammox lineages BROC1 and BROC2 were investigated. Anammox bacteria are known to take up inorganic nitrogen substrates (NH4+ and NO2) and fix CO2. To date, several genes coding for nitrite, nitrate, and ammonium transporters have been reported in genomes for all known anammox lineages.(60, 61) Anammox genomes recovered from both of these metagenomes were found to contain the formate and nitrite transporter focA (7 for BROC1 and 1 for BROC2), the nitrate and nitrite antiporter narK (1 for BROC1 and 1 for BROC2), and the ammonium transporter amtB (5 for BROC1 and 5 for BROC2) (Figure 4b and Supplementary Table 2a,b). Multiple copies of focA genes in our SGR-anammox lineage suggest that it has the potential to survive in oligotrophic environments where the concentrations of inorganic nitrogenous compounds are low.(28, 61, 62) To facilitate transport, anammox bacteria carry genes that encode for two nitrate channel proteins narK (a) high-affinity nitrate/H+ symporters and (b) low-affinity nitrate/H+antiporters. The BROC1 and BROC2 genomes contained only a single copy of low-affinity nitrate and H+ antiporter (narK) each (Supplementary Table 2a,b).

Nitrite (inorganic nitrogen substrate) is reduced to NO by cytochrome cd1-type nitrite reductase NIRS.(24) No genes encoding NIRS were recovered from the BROC1 and BROC2. This finding was similar to earlier research in which Ca. B. fulgida and Ca. J. caeni genomes seemed to lack NIRS encoding genes.(56) Instead, a copper-containing nitrite reductase, NIRK was identified in the Ca. J. caeni genome. Much like Ca. J. caeni, two copies of the gene encoding for copper-containing nitrite reductase, NIRK, were observed in the BROC1, whereas none was recovered for the BROC2 genome. To date, anammox genomes affiliated with the genus Ca. Brocadia have been reported to miss both (copper) nirK and nirS encoding for cd1-type nitric oxide and nitrite oxidoreductase.(54–56) This finding suggests that the Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 abundant in the SGR have developed the metabolic flexibility to generate the essential intermediate NO. The nitrate reductase complex including narG and narH is required to reduce nitrate to nitrite. Here, four and two copies of narG and narH encoding genes, respectively, were identified in the BROC1. However, the BROC2 only contained two identifiable copies each of narG and narH.

Anammox bacteria have developed an intrinsic mechanism to take advantage of the oxidative potential of highly reactive free radical NO. Bacteria employ NorVW flavorubredoxin for detoxification of this free radical molecule.(63) Genes encoding a protein similar to flavoproteins, norVW and fprA, were also identified in the SGR and AGR anammox genomes (Supplementary Table 2a,b).

The ability to synthesize hydrazine (N2H4) is arguably the most intriguing property of anammox bacteria. The direct precursor of hydrazine production is NO, produced through reduction of nitrite and ammonium. HZS is the second known enzyme, after nitric oxide reductase, that has the ability to forge the N–N bond.(13, 28, 56) Multiple copies of genes encoding hzsA (four copies for BROC1 and two copies for BROC2) were identified. However, in the case of hzsC, only one and two copies were identified for BROC1 and BROC2, respectively (Supplementary Table 2a,b). Such observations of variable numbers for components of hzs gene cluster could be due to gaps in draft genomes. The final step of converting hydrazine to dinitrogen gas is catalyzed by hydrazine oxidoreductase (hzo) or hydroxylamine oxidoreductase (hao) (Figure 4b). The anammox lineage genomes recovered from both metagenomes showed the presence of multiple copies of these genes (Supplementary Table 2a,b).

CO2 fixation performed by anammox bacteria is accomplished through acetyl-coenzyme A pathway or the Wood–Ljungdahl pathway.(58, 64) Both acsA and acsB genes encoding synthase were recovered from the BROC1 and BROC2 genomes (Supplementary Table 2a,b), much like the ones present in Ca. K. stuttgartiensis.

The practical question that arises is “How do observations from reactor performance and metagenomics help to investigate the importance in the implementation of lower energy treatment technology, such as anammox, for real-world applications?” Microbial communities play important roles in the nutrient cycles in natural and engineered ecosystems. Understanding the microbial diversity has become an integral part of reactor operation and a way to gain more insight into reactor performance. Based on these metagenomic data, measured reactor performances, and chemical concentrations, a conceptual nitrogen-cycling network for anammox reactors can be constructed.

Suspended (SGR) and attached (AGR) growth reactor configurations achieved comparable rates in total inorganic nitrogen (TIN) removal of 88 ± 4% and 86 ± 2%, respectively, in a period of 220 days. A major factor influencing start-up of the anammox process is the slow growth rate of anammox organisms (0.072 per day when grown at 32 °C).(1, 65) Even seemingly insignificant amounts of biomass loss via effluent could become an impediment to a quick start-up process. Therefore, reducing chances of biomass loss via a suitable reactor configuration is being considered as a possible solution. Attached growth anammox reactors (AGR) immobilize the biomass on the surface of media (K3, and K5; Veolia Municipal Solutions) or on Bio-Balls (for this study).

Our metagenomics analysis revealed enrichment of two anammox-affiliated prokaryotes, BROC1 and BROC2, in both of the reactors. The dominant flanking community in SGR and AGR reactors consisted of prokaryotes affiliated with the phyla Anaerolinea, Ignavibacteria, and Proteobacteria. The dominant flanking community remains similar, even for reactors operated with different configurations. However, the relative abundances of specific microbial groups were different in both reactors despite similar reactor performances. For example, Ignavibacteria and Anaerolinea relative abundances in the AGR were relatively more than in the SGR, whereas the relative abundance of BROC1 and BROC2, two different anammox species, were higher in the SGR. However, the total nitrogen removal percentages in both reactors were nearly identical. This suggests that engineering reactors need not to be highly enriched in anammox biomass to accomplish efficient total inorganic N removal.

Degradation of biomass by Ignavibacteria and Anaerolinea may support community interactions in the system, as hydrolysis processes could provide short-chain volatile fatty acids (VFAs) and alcohols to Proteobacteria. The abundance of Ignavibacteria and Anaerolinea was higher in the AGR, which could be explained by the fact that AGR has theoretically infinite solid retention time (SRT) (no biomass wastage). High SRT can lead to a greater degree of bacterial decay in the system. Therefore, higher Ignavibacteria and Anaerolinea abundances in the AGR may improve the degradation of organics generated via cell decay.(15, 51) Detailed genome analysis of BROC1 and BROC2 genomes extracted from the SGR and AGR metagenomes revealed both species could be placed within the genus Ca. Brocadia. gANI and AF analysis concluded that the Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 and Ca. Brocadia sp. 2 are two different species as their relatedness is >~94%. Additionally, through the investigation of the anammox catabolism process inferred via genome annotations, it was observed that Ca. Brocadia sp. 1 and Ca. Brocadia sp. 2 were metabolically well-suited to grow in inorganic nitrogen environments.

In conclusion, the findings from this research offer much-needed insight into the microbial functions occurring in anammox bioreactors and should guide future efforts aimed at developing strategies for optimizing and controlling process performance. This research provided a detailed understanding of the microbial community structure and reactor performance. The system-based approach detailed in this manuscript provided a better understanding of the molecular responses of molecular community in two different anammox reactors to complex bioreactor conditions. The metabolic pathway depicted in this manuscript, based on whole-community metagenomics, illustrated the presence of the dominant flanking community in enriched anammox reactor. The high abundance of heterotrophic organisms in the SGR and AGR systems investigated here suggests that they play an important role in community function, which should be investigated in future studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We appreciate the North Davis Sewer District, Utah for funding this study. V.K. was supported by U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) via a postdoctoral appointment administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education. We thank Michael Elk for technical support. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through its Office of Research and Development, partially funded and collaborated in the research described herein. Any opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the agency; therefore, no official endorsement should be inferred. Any mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

References

This article references 65 other publications.

- 1.Strous M; Heijnen JJ; Kuenen JG; Jetten MSM The sequencing batch reactor as a powerful tool for the study of slowly growing anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing microorganisms Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol 1998, 50 (5) 589–596 DOI: 10.1007/s002530051340 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thamdrup B New pathways and processes in the global nitrogen cycle Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst 2012,43, 407–428 DOI: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strous M; Fuerst JA; Kramer EH; Logemann S; Muyzer G; van de Pas-Schoonen KT; Webb R;Kuenen JG; Jetten MS Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete Nature 1999, 400 (6743)446–449 DOI: 10.1038/22749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hauck M; Maalcke-Luesken FA; Jetten MS; Huijbregts MA Removing nitrogen from wastewater with side stream anammox: What are the trade-offs between environmental impacts? Resour. Conserv. Recycl 2016, 107, 212–219 DOI: 10.1016/j.resconrec.2015.11.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotay SM; Mansell BL; Hogsett M; Pei H; Goel R Anaerobic ammonia oxidation (ANAMMOX) for side-stream treatment of anaerobic digester filtrate process performance and microbiology Biotechnol. Bioeng 2013, 110 (4) 1180–1192 DOI: 10.1002/bit.24767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van-Dongen UGJM; Jetten MS; Van-Loosdrecht MCM The SHARON®-Anammox® process for treatment of ammonium rich wastewater Water Sci. Technol 2001, 44 (1) 153–160 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Volcke EIP; Van Hulle SWH; Donckels BMR; Van Loosdrecht MCM; Vanrolleghem PA Coupling the SHARON process with Anammox: Model-based scenario analysis with focus on operating costs Water Sci. Technol 2005, 52 (4) 107–115 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kuai L; Verstraete W Ammonium removal by the oxygen-limited autotrophic nitrification-denitrification system Appl. Environ. Microbiol 1998, 64 (11) 4500–4506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strous M; Van Gerven E; Zheng P; Kuenen JG; Jetten MS Ammonium removal from concentrated waste streams with the anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) process in different reactor configurations Water Res. 1997, 31 (8) 1955–1962 DOI: 10.1016/S0043-1354(97)00055-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt I; Sliekers O; Schmid M; Bock E; Fuerst J; Kuenen JG; Jetten MS; Strous M New concepts of microbial treatment processes for the nitrogen removal in wastewater FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2003, 27 (4) 481–492 DOI: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00039-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van der Star WR; Miclea AI; van Dongen UG; Muyzer G; Picioreanu C; van Loosdrecht M The membrane bioreactor: a novel tool to grow anammox bacteria as free cells Biotechnol. Bioeng 2008, 101(2) 286–294 DOI: 10.1002/bit.21891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ni BJ; Hu BL; Fang F; Xie WM; Kartal B; Liu XW; Sheng GP; Jetten M; Zheng P; Yu HQ Microbial and physicochemical characteristics of compact anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing granules in an upflow anaerobic sludge blanket reactor Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2010, 76 (8) 2652–2656 DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02271-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kartal B; Maalcke WJ; de Almeida NM; Cirpus I; Gloerich J; Geerts W; den Camp HJO;Harhangi HR; Janssen-Megens EM; Francoijs KJ Molecular mechanism of anaerobic ammonium oxidation Nature 2011, 479 (7371) 127–130 DOI: 10.1038/nature10453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo J; Peng Y; Fan L; Zhang L; Ni BJ; Kartal B; Feng X; Jetten MS; Yuan Z Metagenomic analysis of anammox communities in three different microbial aggregates Environ. Microbiol 2016, 18 (9)2979–2993 DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.13132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Gil G; Sougrat R; Behzad AR; Lens PN; Saikaly PE Microbial community composition and ultrastructure of granules from a full-scale anammox reactor Microb. Ecol 2015, 70 (1) 118–131 DOI: 10.1007/s00248-014-0546-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speth DR; Guerrero-Cruz S; Dutilh BE; Jetten MS; in’t Zandt MH Genome-based microbial ecology of anammox granules in a full-scale wastewater treatment system Nat. Commun 2016, 7, 1–10 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langone M; Yan J; Haaijer SC; den Camp HJO; Jetten MS; Andreottola G Coexistence of nitrifying, anammox and denitrifying bacteria in a sequencing batch reactor Front. Microbiol 2014, 5, 1–12 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Third KA; Sliekers AO; Kuenen JG; Jetten MSM The CANON system (completely autotrophic nitrogen-removal over nitrite) under ammonium limitation: interaction and competition between three groups of bacteria Syst. Appl. Microbiol 2001, 24 (4) 588–596 DOI: 10.1078/0723-2020-00077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vázquez-Padín JR; Mosquera-Corral A; Campos JL; Méndez R; Carrera J; Pérez J Modelling aerobic granular SBR at variable COD/N ratios including accurate description of total solids concentration Biochem. Eng. J 2010, 49 (2) 173–184 DOI: 10.1016/j.bej.2009.12.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang CC; Lee PH; Kumar M; Huang YT; Sung S; Lin JG Simultaneous partial nitrification, anaerobic ammonium oxidation and denitrification (SNAD) in a full-scale landfill-leachate treatment plant J. Hazard. Mater 2010, 175 (1) 622–628 DOI: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.10.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harhangi HR; Le Roy M; van Alen T; Hu BL; Groen J; Kartal B; Tringe SG; Quan ZX;Jetten MS; den Camp HJO Hydrazine synthase, a unique phylomarker with which to study the presence and biodiversity of anammox bacteria Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2012, 78 (3) 752–758 DOI: 10.1128/AEM.07113-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tyson GW; Chapman J; Hugenholtz P; Allen EE; Ram RJ; Richardson PM; Solovyev VV;Rubin EM; Rokhsar DS; Banfield JF Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment Nature 2004, 428 (6978) 37–43 DOI: 10.1038/nature02340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Venter JC; Remington K; Heidelberg JF; Halpern AL; Rusch D; Eisen JA; Wu D; Paulsen I;Nelson KE; Nelson W Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea Science 2004, 304 (5667) 66–74 DOI: 10.1126/science.1093857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strous M; Pelletier E; Mangenot S; Rattei T; Lehner A; Taylor MW; Horn M; Daims H;Bartol-Mavel D; Wincker P; Barbe V Deciphering the evolution and metabolism of an anammox bacterium from a community genome Nature 2006, 440 (7085) 790–794 DOI: 10.1038/nature04647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon C; Daniel R Metagenomic analyses: past and future trends Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2011, 77 (4)1153–1161 DOI: 10.1128/AEM.02345-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu Z; Speth DR; Francoijs KJ; Quan ZX; Jetten M Metagenome analysis of a complex community reveals the metabolic blueprint of anammox bacterium “Candidatus Jettenia asiatica Front. Microbiol 2012,3, 366 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas T; Gilbert J; Meyer F Metagenomics-a guide from sampling to data analysis Microb. Inf. Exp 2012, 2 (1) 3 DOI: 10.1186/2042-5783-2-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van de Vossenberg J; Woebken D; Maalcke WJ; Wessels HJCT; Dutilh BE; Kartal B;Janssen-Megens EM; Roeselers G; Yan J; Speth DR; Gloerich J; Op den Camp HJM;Stunnenberg HG; Amann R; Kuypers MMM; Jetten MSM The metagenome of the marine anammox bacterium ‘Candidatus Scalindua profunda’ illustrates the versatility of this globally important nitrogen cycle bacterium Environ. Microbiol 2013, 15 (5) 1275–1289 DOI: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02774.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park H; Rosenthal A; Jezek R; Ramalingam K; Fillos J; Chandran K Impact of inocula and growth mode on the molecular microbial ecology of anaerobic ammonia oxidation (anammox) bioreactor communities Water Res. 2010, 44 (17) 5005–5013 DOI: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.07.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kapoor V; Li X; Elk M; Chandran K; Impellitteri CA; Santo Domingo JW Impact of heavy metals on transcriptional and physiological activity of nitrifying bacteria Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49 (22) 13454–13462 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caporaso JG; Lauber CL; Walters WA; Berg-Lyons D; Lozupone CA; Turnbaugh PJ;Fierer N; Knight R Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caporaso JG; Kuczynski J; Stombaugh J; Bittinger K; Bushman FD; Costello EK; Fierer N;Pena AG; Goodrich JK; Gordon JI; Huttley GA QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data Nat. Methods 2010, 7 (5) 335–336 DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Magoč T; Salzberg SL FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies Bioinformatics 2011, 27 (21) 2957–2963 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edgar RC; Haas BJ; Clemente JC; Quince C; Knight R UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection Bioinformatics 2011, 27 (16) 2194–2200 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edgar RC Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST Bioinformatics 2010, 26 (19)2460–2461 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quast C; Pruesse E; Yilmaz P; Gerken J; Schweer T; Yarza P; Peplies J; Glöckner FO The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools Nucleic Acids Res.2013, 41 (D1) D590–D596 DOI: 10.1093/nar/gks1219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kunin V; Engelbrektson A; Ochman H; Hugenholtz P Wrinkles in the rare biosphere: pyrosequencing errors can lead to artificial inflation of diversity estimates Environ. Microbiol 2010, 12 (1) 118–123 DOI: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02051.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joshi N; Fass JN Sickle-A windowed adaptive trimming tool for FASTQ files using quality; UC Davis:California. URL: http://bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/software/ (accessed: September 7, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Namiki T; Hachiya T; Tanaka H; Sakakibara Y MetaVelvet: an extension of Velvet assembler to de novo metagenome assembly from short sequence reads Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40 (20) e155–e155 DOI: 10.1093/nar/gks678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Darling AE; Jospin G; Lowe E; Matsen FA IV; Bik HM; Eisen JA PhyloSift: phylogenetic analysis of genomes and metagenomes PeerJ 2014, 2, e243 DOI: 10.7717/peerj.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haider B; Ahn TH; Bushnell B; Chai J; Copeland A; Pan C Omega: an Overlap-graph de novo Assembler for Metagenomics Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (19) 2717–2722 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu YW; Tang YH; Tringe SG; Simmons BA; Singer SW MaxBin: an automated binning method to recover individual genomes from metagenomes using an expectation-maximization algorithm Microbiome 2014, 2 (1) 1 DOI: 10.1186/2049-2618-2-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parks DH; Imelfort M; Skennerton CT; Hugenholtz P; Tyson GW Check M: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes Genome Res. 2015, 25 (7)1043–1055 DOI: 10.1101/gr.186072.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bosi E; Donati B; Galardini M; Brunetti S; Sagot MF; Lió P; Crescenzi P; Fani R; Fondi M MeDuSa: a multi-draft based scaffolder Bioinformatics 2015, 31 (15) 2443–2451 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu S; Zhu Z; Fu L; Niu B; Li W WebMGA: a customizable web server for fast metagenomic sequence analysis BMC Genomics 2011, 12 (1) 1 DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laslett D; Canback B ARAGORN, a program to detect tRNA genes and tmRNA genes in nucleotide sequences Nucleic Acids Res. 2004, 32 (1) 11–16 DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkh152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Konwar KM; Hanson NW; Pagé AP; Hallam SJ MetaPathways: a modular pipeline for constructing pathway/genome databases from environmental sequence information BMC Bioinf. 2013, 14 (1) 202 DOI: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamura K; Peterson D; Peterson N; Stecher G; Nei M; Kumar S MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods Mol. Biol. Evol 2011, 28 (10) 2731–2739 DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msr121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varghese NJ; Mukherjee S; Ivanova N; Konstantinidis KT; Mavrommatis K; Kyrpides NC; Pati A Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43 (14) 6761–6771 DOI: 10.1093/nar/gkv657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.López H; Puig S; Ganigué R; Ruscalleda M; Balaguer MD; Colprim J Start-up and enrichment of a granular anammox SBR to treat high nitrogen load wastewaters. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol, 2008, 83(3), pp 233–241. DOI: DOI: 10.1002/jctb.1796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kindaichi T; Yuri S; Ozaki N; Ohashi A Ecophysiological role and function of uncultured Chloroflexi in an anammox reactor Water Sci. Technol 2012, 66 (12) 2556–2561 DOI: 10.2166/wst.2012.479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hira D; Toh H; Migita CT; Okubo H; Nishiyama T; Hattori M; Furukawa K; Fujii T Anammox organism KSU-1 expresses a NirK-type copper containing nitrite reductase instead of a NirS-type with cytochrome cd 1 FEBS Lett. 2012, 586 (11) 1658–1663 DOI: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ali M; Oshiki M; Okabe S Simple, rapid and effective preservation and reactivation of anaerobic ammonium oxidizing bacterium “Candidatus Brocadia sinica Water Res. 2014, 57, 215–222 DOI: 10.1016/j.watres.2014.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oshiki M; Ali M; Shinyako-Hata K; Satoh H; Okabe S Hydroxylamine-dependent anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) by “Candidatus Brocadia sinica Environ. Microbiol 2016, 18 (9) 3133–3143 DOI: 10.1111/1462-2920.13355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oshiki M; Shinyako-Hata K; Satoh H; Okabe S Draft Genome Sequence of an Anaerobic Ammonium-Oxidizing Bacterium,”Candidatus Brocadia sinica Genome Announc 2015, 3 (2) e00267–15 DOI: 10.1128/genomeA.00267-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gori F; Tringe SG; Kartal B; Machiori E; Jetten MS The metagenomic basis of anammox metabolism in Candidatus ‘Brocadia fulgida’ Biochem. Soc. Trans 2011, 39 (6) 1799–1804 DOI: 10.1042/BST20110707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghiurcuta CG; Moret BM Evaluating synteny for improved comparative studies Bioinformatics 2014, 30 (12) i9–i18 DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kartal B; de Almeida NM; Maalcke WJ; den Camp HJO; Jetten MS; Keltjens JT How to make a living from anaerobic ammonium oxidation FEMS Microbiol. Rev 2013, 37 (3) 428–461 DOI: 10.1111/1574-6976.12014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Konstantinidis KT; Tiedje JM Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2005, 102 (7) 2567–2572 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Füssel J; Lam P; Lavik G; Jensen MM; Holtappels M; Günter M; Kuypers MM Nitrite oxidation in the Namibian oxygen minimum zone ISME J. 2012, 6 (6) 1200–1209 DOI: 10.1038/ismej.2011.178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hu Z; Speth DR; Francoijs KJ; Quan ZX; Jetten M Metagenome analysis of a complex community reveals the metabolic blueprint of anammox bacterium “Candidatus Jettenia asiatica” Front. Microbiol 2012,3, 366 DOI: 10.3389/fmicb.2012.00366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lam P; Kuypers MM Microbial nitrogen cycling processes in oxygen minimum zones Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci 2011, 3, 317–345 DOI: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kartal B; Kuenen JG; Van Loosdrecht MCM Sewage treatment with anammox Science 2010, 328 (5979) 702–703 DOI: 10.1126/science.1185941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schouten S; Strous M; Kuypers MM; Rijpstra WIC; Baas M; Schubert CJ; Jetten MS;Damsté JSS Stable carbon isotopic fractionations associated with inorganic carbon fixation by anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria Appl. Environ. Microbiol 2004, 70 (6) 3785–3788 DOI: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3785-3788.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jetten MS; Strous M; Van de Pas-Schoonen KT; Schalk J; van Dongen UG; van de Graaf AA;Logemann S; Muyzer G; van Loosdrecht MC; Kuenen JG The anaerobic oxidation of ammonium FEMS Microbiol. Rev 1998, 22 (5) 421–437 DOI: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.