Abstract

Molecular (nucleic acid)-based diagnostics tests have many advantages over immunoassays, particularly with regard to sensitivity and specificity. Most on-site diagnostic tests, however, are immunoassay-based because conventional nucleic acid-based tests (NATs) require extensive sample processing, trained operators, and specialized equipment. To make NATs more convenient, especially for point-of-care diagnostics and on-site testing, a simple plastic microfluidic cassette (“chip”) has been developed for nucleic acid-based testing of blood, other clinical specimens, food, water, and environmental samples. The chip combines nucleic acid isolation by solid-phase extraction; isothermal enzymatic amplification such as LAMP (Loop-mediated AMPlification), NASBA (Nucleic Acid Sequence Based Amplification), and RPA (Recombinase Polymerase Amplification); and real-time optical detection of DNA or RNA analytes. The microfluidic cassette incorporates an embedded nucleic acid binding membrane in the amplification reaction chamber. Target nucleic acids extracted from a lysate are captured on the membrane and amplified at a constant incubation temperature. The amplification product, labeled with a fluorophore reporter, is excited with a LED light source and monitored in situ in real time with a photodiode or a CCD detector (such as available in a smartphone). For blood analysis, a companion filtration device that separates plasma from whole blood to provide cell-free samples for virus and bacterial lysis and nucleic acid testing in the microfluidic chip has also been developed. For HIV virus detection in blood, the microfluidic NAT chip achieves a sensitivity and specificity that are nearly comparable to conventional benchtop protocols using spin columns and thermal cyclers.

Keywords: Point-of-care, On-site, Molecular diagnostics, DNA, RNA, Infectious diseases, Pathogen, Microfluidics, Enzymatic, Amplification, LAMP, Isothermal

1. Introduction

On-site detection of pathogens and other disease markers can improve the quality and lower the costs of health care [1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9., 10]. Portable on-site tests can also monitor the safety of food [11, 12] and water supplies [13]. Clinical specimens can be processed in credit-card sized, plastic microfluidic cartridges (“chips”) that can be coupled to cell phones and other portable devices for detection, data analysis, and communications. In particular, a cell phone camera can be used to detect fluorescent signals such as used to monitor the production of amplicons during the enzymatic amplification process. This “lab-on-a-chip” technology provides for Point-of-Care (POC) diagnostics and serves as crucial enabling technology for mobile health care (mHealth). For example, the smartphone will transmit the test results to the patient’s medical files, to the health provider, and, when appropriate and/or required by law, to public health officials. Based on the test results, the smartphone application could download instructions from the cloud to guide the patient. The health provider can contact a pharmacy and order prescriptions, provide additional guidance remotely, and encourage/discourage an office visit as appropriate.

This chapter describes the development of a microfluidic cassette for nucleic acid based pathogen assays (with specific application to HIV viral load testing), and which is compatible with cell phone-based end-point detection of fluorescence signals generated in real-time enzymatic amplification of a pathogen target. The approach and methods reported here are sufficiently generic and can be readily adapted to other POC diagnostics applications.

Broadly, in vitro bioanalytical methods can be classified into three categories: (1) immunoassays that rely on specific antigen–antibody binding (or analogous protein interactions) for isolation and labeling of analytes such as antibodies and/or antigens; (2) nucleic acid-based (molecular) tests (NATs) that utilize sequence-specific nucleic acid hybridization, and for which the sensitivity can be greatly enhanced by enzymatic amplification; and (3) cell-based methods incorporating cell fractionation and sorting, selective labeling, and/or cytometry which are often amenable to target amplification via cell culturing. Most existing rapid (<hour), on-site test devices are based on immunoassays [14, 15] since NATs are comparatively complicated and culturing and other cell-based methods are time-consuming.

Immunoassays are operationally simple because they are tolerant of sample heterogeneity and require few, if any, sample preparation and processing steps. Immunoassays can be performed with raw or minimally processed specimens such as blood, urine, saliva, cell culture, tissue, water, and environmental samples. For example, the lateral flow (LF) strip format offers an elegant, simple, and inexpensive implementation of immunoassays [16]. LF strip immunoassay tests, such as home pregnancy tests and drugs-of-abuse tests, are widely available.

Nucleic acid tests (NAT), also known as molecular assays, have a crucial advantage over immunoassays in that nucleic acids can be amplified in vitro by sequence-specific enzymatic reactions, thus facilitating highly sensitive detection. A single target DNA molecule can be replicated a billion times within an hour. The specificity of the test can be tailored by appropriate primer design. Typically, nucleic acid-based tests offer much greater (often 1,000-fold or more) sensitivity and specificity than immunoassays. Nucleic acid-based tests can also provide information that cannot be readily obtained with immunoassays such as discrimination between drug-susceptible and drug-resistant pathogens and the identification of genes and gene transcription profiles. Despite their many advantages, molecular assays are still not commonly used at the point of care and are generally restricted to centralized laboratories since nucleic acid-based tests typically require elaborate sample processing to release, isolate, and concentrate the nucleic acids and remove substances that inhibit enzymatic amplification. Conventional nucleic acid testing requires benchtop equipment such as centrifuges, water baths, thermal cyclers, and gel readers; cold storage for labile reagents; dedicated lab areas and hoods to avoid contamination, and highly trained personnel. Moreover, for molecular analysis of blood specimens, cell-free plasma is preferred. The use of plasma instead of whole blood in NATs avoids problems associated with inhibitors (such as hemoglobin in red blood cells) [17, 18, 19.], clogging of filters or porous membranes with cells and cell debris, and complications in interpretation of results related to nucleic acids associated with white blood cells [20]. The plasma is typically separated from whole blood by centrifugation. However, such and similar plasma extraction adds an extra processing step to NAT, further burdening point of care (POC) applications.

The objective of microfluidics implementations of nucleic acid tests is to make NAT almost as easy-to-use as LF strip test devices. As an illustration, we describe a single-use (disposable), plastic, microfluidic cassette or cartridge (“chip”) that hosts fluidic networks of conduits, reaction chambers, porous membrane filters, and inlet/outlet ports for sample processing and analysis. The sequential steps of sample metering, lysis of the pathogen target, NA isolation, reverse transcription (for RNA targets), enzymatic amplification primed with target-sequence oligos, amplicon labeling, and detection are integrated in the microfluidic chip. Fluid actuation and flow control, temperature control, and optical detection are provided by supporting instrumentation. Completely automated operation (without any human intervention) is feasible. Many microfluidic NAT devices [21, 22, 23], including our earlier prototypes [24, 25, 26, 27], utilize PCR (polymerase chain reaction) for nucleic acid amplification. For example, Chen et al. [26] describe a microfluidic cassette for PCR-based nucleic acid detection. The palm-sized cassette mates with a portable instrument [28] that provides temperature regulation using thermoelectric elements, solenoid actuation of pouches and diaphragm valves formed on the chip for flow control and pumping, and LED/photodiode detection of amplification products labeled with an intercalating fluorescent dye. The time needed from sample loading to obtaining test results is typically less than 1 h.

Although PCR technology is highly developed and PCR primers sequences are available for many targets, PCR is not optimal for on-site applications. PCR requires precise (±1 °C or better) temperature control and rapid (>5 °C/s) temperature ramping, which complicates implementation and increases the cost of instrumentation. The high temperatures (~95 °C) required for PCR places demands on chip design, necessitating strong bonding of chip components to withstand the pressure of the heated reaction mixture due to expanding trapped air and thermal expansion of the liquid phase and tight sealing of the amplification chamber to avoid evaporation. As an alternative to PCR, isothermal amplification methods are much easier to implement in on-site applications. Constant-temperature operation lowers energy consumption and even allows the use of small-scale exothermic chemical reactions for heating without a need for any electric power [29.]. Thus, a considerable simplification in chip design and operation is realized with isothermal amplification methods [30, 31, 32, 33, 34] that require, depending on the amplification scheme, an incubation temperature ranging from 40 to 65 °C. Examples of isothermal amplification include Loop-mediated AMPlification (LAMP) to detect DNA targets [35], one-step reverse transcription (RT) with cDNA LAMP (RT-LAMP) to detect RNA targets [36, 37, 38], Nucleic Acid Sequence Based Amplification (NASBA) [39., 40], Recombinase Polymerase Amplification (RPA) [41, 42], and helicase-dependent amplification (HDA) [43, 44, 45]. Tests using isothermal amplification are typically faster than PCR (roughly, 30 min vs. 60 min). Also, LAMP appears to be more robust than PCR. It is more tolerant of temperature variations and less susceptible to the adverse effects of inhibitors [46]. In this chapter, we focus on LAMP. We have, however, successfully tested our chips with NASBA and RPA (results not shown) and obtained comparable results to the ones obtained with LAMP.

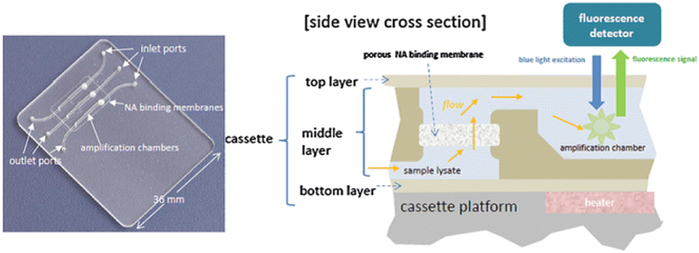

To streamline sample processing and flow control, we use “multifunctional” amplification reactors that incorporate porous flow-through membranes for immobilization of nucleic acids [47, 48]. A disc-shaped silica- or cellulose-based membrane is embedded in the chip at the inlet of each reaction chamber. Nucleic acid capture, washing, amplification, and detection are all combined in a single chamber that houses the NA binding membrane. The target nucleic acid captured on the membrane serves as a template for amplification, thus obviating the need for a separate membrane elution step (as done in spin column formats), and thereby simplifying chip design and flow control. Multiple amplification reactors can be accommodated in the same chip (Fig. 1) for concurrent detection of several targets, as well as calibration reactions, and positive and negative controls.

Fig. 1.

(Left) Photograph of a chip containing an array of three multifunctional amplification reactors. (Right) A cross section of a multifunctional amplification reactor featuring the flow-through membrane for the capture and immobilization of nucleic acids

The lab-on-a-chip format can facilitate autonomous point-of-care molecular diagnostics with various levels of automation, instrumentation, and functionality. For more convenient use, the chips can be preloaded with lyophilized amplification reagents [49., 50, 51, 52, 53]. During chip assembly, the LAMP reagents (enzymes, primers, dyes, salts) are measured and mixed in correct proportions and pipetted into the chip amplification chamber, dried by sublimation, and coated with a low-melting point (~55 °C) paraffin wax layer [52]. The chip is then sealed with a capping layer. The wax encapsulation protects the pre-stored reagents when the sample and wash solutions flow through the amplification reactor. When the chamber is filled with water and heated to the LAMP incubation temperature (~65 °C), the wax coating melts, just in time, and releases the LAMP reagents to amplify the target NAs captured on the membrane.

For brevity, we describe in this chapter a manually operated NAT module. The sample and reagents are loaded into the chip by pipetting in the appropriate sequence. This manually operated version realizes only some of the advantages of microfluidic systems. For a commercially viable system, the reagents will be pre-stored in the chip and the fluid delivery automated. The module described here is, however, a substantial step towards the ultimate goal of fully automated operation. We describe the design, fabrication, and operation of the multifunctional reactor module. As a representative application, we describe the detection of an RNA virus (HIV) in blood plasma samples. Adaptations of the chip and protocol for other targets and applications are comparatively minor. We have used approaches similar to the one reported here for the detection of lambda phage in water, Gram-positive bacteria (B. cereus) [24] and gram-negative bacteria (Salmonella) in buffer, E. coli in urine and stool samples, and HIV virus in saliva [25], and for genotyping malaria-transmitting mosquito subspecies using insect tissue [48]. The chips, with modifications, can also be used for gene profiling as may be needed for cancer screening [54]. To accommodate blood-based samples, we describe a simple uninstrumented filtration device for separating plasma from whole blood. The extracted plasma is then subjected to a chemical lysis step to solubilize nucleic acids from viral or bacterial pathogens in the extracted plasma. The plasma-derived lysate is then loaded into the microfluidic chip for assay of a sequence-specific nucleic acid biomarker.

2. Materials

Materials used include:

-

1. 1.

Polymer chip materials stock: acrylic (polymethylmethacrylate PMMA, CYRO Industries, Rockaway, NJ or various suppliers such as McMaster-Carr) or polycarbonate (PC, e.g., Lexan™ from ePlastics.com or various suppliers such as McMaster Carr) or cyclic olefin polymer (COC, Topas, Florence, KY), approx. 0.1 and 1 mm thick sheets.

-

2. 2.

Bonding solvent for PMMA: acetonitrile (Sigma-Aldrich); for PC: acetone (Sigma-Aldrich).

-

3. 3.

Chip sealing tape: Microseal “B” Adhesive (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA).

-

4. 4.Surface passivants (optional).

-

1. (a)BSA (bovine serum albumin, 1–2 %, Sigma-Aldrich),

-

2. (b)PVP-40 (polyvinylpyrrolidone 40, Sigma-Aldrich) or polyethylene glycol (1–2 % PEG, 6,000 MW, Sigma-Aldrich).

-

1. (a)

-

5. 5.

Polyimide-based, thin film heater (HK5572R7.5L23A, Minco Products, Inc., Minneapolis, MN).

-

6. 6.

DC power supply (e.g., Model 1611, B&K Precision Corporation, CA).

-

7. 7.Nucleic Acid binding phases:

-

1. (a)Silica-based phases: Whatman™ GF/F borosilicate glass fiber filter paper (0.42 mm thick, 0.7 μm pore size), or

-

2. (b)Cellulose-based membranes (Whatman FTA™ paper: 3MM Whatman cellulose filter paper, 0.5 mm thick, with dried Tris–HCl, EDTA, and SDS, which can be washed off the FTA paper before mounting in the chip).

-

1. (a)

-

8. 8.

Harris Unicore™ (2 or 3-mm diameter, Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA) for cutting discs of binding phase for insertion in chip.

-

9. 9.Commercial kits with reagents (binding/lysis buffer, wash buffers, elution buffers) for isolation of nucleic acids:

-

1. (a)Qiagen Blood and Tissue kit (Valencia, CA).

-

2. (b)Roche HighPure™ Viral RNA kit or Qiagen QIAamp® kit were used for RNA isolation.

-

3. (c)Elution buffer: Tris-acetate EDTA (TAE) buffer (10×) (Sigma-Aldrich).

-

1. (a)

-

10. 10.Enzymatic Amplification Kits

-

1. (a)Loopamp™ DNA amplification kit (Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd.,Tochigi, Japan).

-

2. (b)RPA kit (TwistDX, Cambridge, UK), and the

-

3. (c)NASBA kit (Biomérieux, Durham, NC).

-

1. (a)

-

11. 11.

RNase inhibitor (Ambion®, Life Technologies) for amplification reactions with the reverse transcription steps.

-

12. 12.Fluorescent dyes for nucleic acid detection:

-

1. (a)SYTO-9 Green (Invitrogen Corp. Carlsbad, CA) or

-

2. (b)EvaGreen (Biotium, Hayward, CA).

-

1. (a)

-

13. 13.

Positive HIV controls of known virus concentration (Acrometrix®, Benecia, CA).

-

14. 14.

Published LAMP primer sets [38], HPLC purified (e.g., custom synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich).

(Suggested vendors are included for convenience, but comparable substitutions are generally permissible.)

3. Methods

3.1. Chip Design and Fabrication

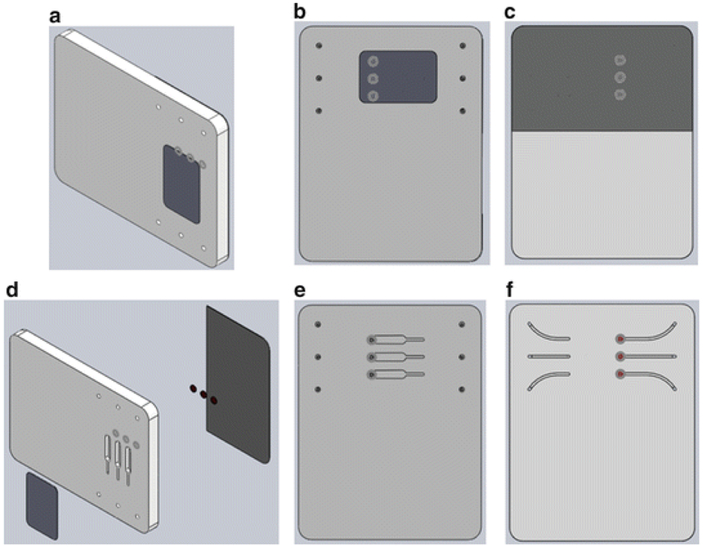

The microfluidic chips (Fig. 1) are fabricated in clear (transparent) plastic materials as bonded laminates. We have tested three different thermoplastic polymers: polycarbonate (PC), acrylic (PMMA), and cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) (Table 1). The chips have been rapidly prototyped using computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided manufacturing software (SolidWorks™, MasterCAM™, or AutoCAD™). The 0.1–1-mm thick plastic sheets are cut with a computer-controlled (CNC) milling machine (e.g., Haas Office Mill OM-1, Haas Automation, Oxnard, CA) or with a CO2 laser (e.g., Universal Laser Systems, Scottsdale, AZ, 30–50 W power) to define the microfluidic circuit(s) and other features (Fig. 2). Chip fabrication and bonding methods for these materials are discussed in more details in references [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62]. The smallest feature size is the channel width, which is ~800 μm. For acrylic-based chips, the component layers are bonded with a weak solvent such as acetonitrile. These polymer materials exhibit low surface adsorption and usually do not require any special surface treatments; however, dynamic surface passivation with BSA (bovine serum albumin, 1–2 %), PVP-40 (polyvinylpyrrolidone 40), or polyethylene glycol (1–2 % PEG, 6,000 MW), added to the reagent mix, can enhance the amplification efficiency, presumably by reducing surface adsorption of template, enzymes, and primers [63, 64, 65, 66]. The chip materials are generally optically transparent and allow observation of fluid flow during operation. Portions of the chip that require transmission of exciting light and fluorescence emission are made sufficiently thin to minimize autofluorescence. Autofluorescence associated with various chip materials has been characterized [67]. We note that the use of PCR-compatible sealing tapes for sealing the chamber avoid any unwanted adsorption of bonding solvent on the NA binding membrane.

Table 1.

Thermoplastic polymer stock for chipsa

| Material | Trade names |

CO2 Laser cutting |

Optical transparency (nm) |

Autofluore- scene |

Bonding | Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “Acrylic” Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) | Plexiglass®, Lucite®, Perspex® | Yes | 300–1,200 | Moderate to high, depending on particular PMMA | Thermal/pressure, solvent (acetonitrile), ultrasonic welding | Low |

| Polycarbonate (PC) | Lexan® | No | 250–1,200 | Moderate to relatively high | Thermal/pressure, solvent (acetone) | Low |

| Cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) | TOPAS® COC | Yes | 200–1,200 | Low | Thermal/pressure, solvent (hexane) | Moderate |

These materials are available in sheets of thicknesses ranging from 0.1 to 3 mm. One layer of the chip is made from a PCR sealing film (PCR Sealers™ Microseal B, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). This is a PCR-compatible adhesive tape with good transparency and low autofluorescence

Fig. 2.

Microcluidic NAT chip CAD drawings (SolidWorks™) showing assembled, bonded structure and component layers. (a) Assembled chip. (b) Top view showing the inlets and outlets and the PMMA tape covering the reaction chambers. (c) Underside view showing the PCR tape covering the membrane isolation chamber and conduits. (d) Exploded view. (e) Top view of the main slab showing the uncovered amplification chambers. (f) Underside view of the main slab (without the PCR sealing tape) showing the isolation chambers with embedded membranes and the conduits

The chip shown in Fig. 1 measures 46 mm χ 36 mm χ 3.50 mm and consists of three layers: a top layer made with 250 μm (0.01 in.) thick PMMA film, a 3 mm (0.118 in.) thick PMMA chip body, and a 250 μm (0.01 in.) thick PCR Sealers™ tape bottom. Each reaction chamber is ~5 mm long, ~1 mm wide, and 3 mm deep, to form a volume of ~15 μl. Smaller volumes are also feasible. Both the top PMMA film and the PCR Sealers™ tape bottom were cut with a CO2 laser. The chip body (middle layer) was milled with a (CNC) milling machine to form three separate reactors, membrane disc supports, and access conduits [47, 48]. The top PMMA film was solvent-bonded with acetonitrile at room temperature. Residual solvent was removed by overnight heating at 50 °C. The solvent bonding can be effected by stacking and aligning the layers and running a bead (~5–10 μl) of solvent around the periphery of the stack using a pipette. The solvent wicks into the interface between adjacent layers and forms a strong bond after about 10 min (see Note 1.

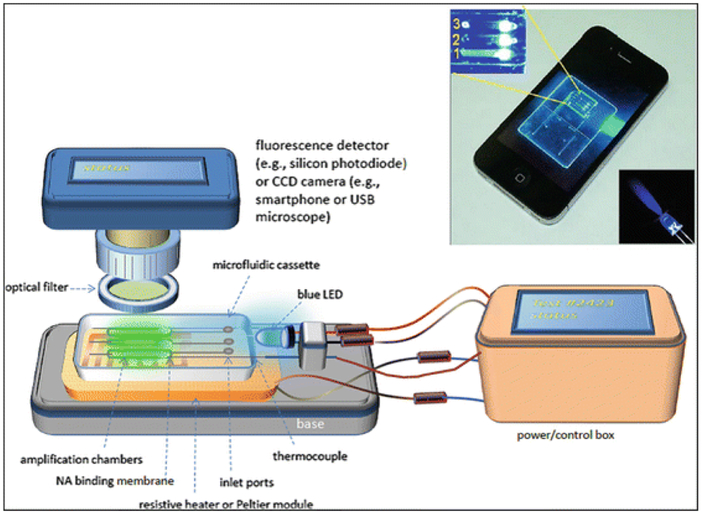

The experimental setup for on-chip LAMP amplification and end-point fluorescent detection is shown in Fig. 3. Briefly, the resistive heating system consists of a chip support equipped with a flexible, polyimide-based, thin film heater (HK5572R7.5L23A, Minco Products, Inc., Minneapolis, MN) and a type T thermocouple (Omega Engineering, each wire 75 μm in diameter, and a junction diameter of 170 μm). The thermocouple junction was placed at the interface between the heater and the chip. The chip, once filled with the LAMP master mix, was fixed to the chip support with a doublesided adhesive tape, allowing the reactors to form a good thermal contact with the thin film heater. The heater was powered by a DC power supply (Model 1611, B&K Precision Corporation, CA). The power supply was adjusted to maintain the reactors at 63 ± 0.5 °C. Although the LAMP process is fairly forgiving to temperature variations, in field applications, it would be necessary to use a closed-loop thermal controller to accommodate operation over the broad range of ambient temperatures that may be encountered in various regions and times.

Fig. 3.

Experimental Setup for operating microfluidic cassette showing cassette mounted on base supporting heater and blue LED. Detector or camera is positioned over cassette. Optical filter blocks blue excitation light to allow detection of green fluorescence from LAMP reaction(s) on cassette. A power/control box provides power for heater and LED, and auxilliary functions such as data logging and communication with smartphone. Inset shows photo of real-time LAMP reaction on cassette

3.2. Use of Nucleic Acid Binding Phases for Isolation of Nucleic Acids

The chip features solid-phase extraction to isolate nucleic acids from samples. The chip described here is based on the method of Boom et al. [68, 69., 70] using chaotropic salts to promote selective binding of NAs to a (silica-based) solid phase, and as adapted by others [71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77] for microfluidic implementation. Several types of porous membranes for the nucleic acid (NA) binding phase have been employed, including “silica” (Whatman™ GF/F borosilicate glass fiber filter paper, 0.42 mm thick, 0.7 μm pore size) and cellulose-based membranes (Whatman FTA™ paper: 3MM Whatman cellulose filter paper, 0.5 mm thick, with dried Tris–HCl, EDTA, and SDS, which can be washed off the FTA paper before mounting in the chip). Both these membranes can be readily cut to the desired shape and size (e.g., 1.5 mm diameter) using a hole punch (Harris Unicore™, Ted Pella, Inc., Redding, CA), and then inserted into the chip during its assembly. Other membranes such as nanoporous alumina (Whatman Nanopore™) can also function as nucleic acid binding phases, but are difficult to cut to size and mount in the chip due to their brittleness [52, 53] (see Note 2).

3.3. Reagents

During development stages, reagents from commercial nucleic acid isolation kits can be used, or alternatively, NA isolation can be done with generic components as specified in Tables 2, 3 and 4. DNeasy™ Blood and Tissue kit, which includes AL (lysis and binding) buffer and AW1 and AW2 ethanol-based wash buffers, was purchased from Qiagen Inc. (Valencia, CA). Roche HighPure™ Viral RNA kit or Qiagen QIAamp® kit were used for RNA isolation. The Loopamp™ DNA amplification kit was obtained from Eiken Chemical Co. Ltd. (Tochigi, Japan). The RPA kit was supplied by TwistDX (Cambridge, UK), and the NASBA kit was from Biomérieux (Durham, NC). RNase inhibitor (Ambion®, Life Technologies) was added to the amplification reactions with the reverse transcription steps. SYTO-9 Green (Invitrogen Corp. Carlsbad, CA) or EvaGreen (Biotium, Hayward, CA) were used as DNA binding dyes and were added directly to the amplification reaction mix at recommended dilutions. Acetonitrile, acetone, ethanol, and Tris-acetate EDTA (TAE) buffer (10×) were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich and were used without further purification. For HIV LAMP testing, we used dilutions of positive controls of known virus concentration (Acrometrix®, Benecia, CA) and published LAMP primer sets [38].

Table 2.

Reagents and buffers for on-chip isolation of DNA targets (i.e., B. cereus)

| Reagents | Qiagen DNEasy™ kit | Generic reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Lysis/binding buffer | AL lysis buffer (with 5 M guanidine HCl) | 6 M Guanidine HCl, 1 % Tween®, SDS (sodium dodecyl sulfate), or Triton X® |

| Proteinase K (optional) | ||

| Wash buffer 1 | AW1 buffer | 50 % ethanol; 50 % water |

| Wash buffer 2 | AW2 buffer | 50 % ethanol; 50 % water |

Table 3.

Reagents and buffers for on-chip isolation of viral RNA targets (i.e., HIV virus)

| Reagent step |

Qiagen QIAamp™ viral RNAkit |

Roche High Pure™ Viral RNA kit |

Generic reagents |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lysis/binding buffer | AVL buffer (contains guanidine thiocyanate) | Lysis/binding buffer Inhibitor removal buffer (4.5 M guanidine-HCl, 50 mM Tris–HCl, 30 % Triton® X-100) | 6 M Guanidine HCl or 6 M guanidine thiocyanate |

| Wash buffer 1 | AW1 buffer (contains guanidine HCl), ~50 % ethanol | Inhibitor removal buffer (5 M guanidine-HCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 40 % (v/v) ethanol, pH 6.6) | 50 % ethanol; 50 % water |

| Wash buffer 2 | AW2 buffer, ~50 % ethanol | Wash Buffer (approx. 50 % (v/v) ethanol, 20 mM NaCl, 2 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5) | 50 % ethanol; 50 % water |

Table 4.

Isothermal amplification specifications

| Amplification method |

Supplier | Reaction mix (25 μl, total volume) |

Incubation temperature Primers (°C) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAMP (Loop-mediated amplification) | Eiken Chemical (Tochigi, Japan) | 20 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.8), 10 mM KCl, 10 mM (NH2)SO4, 8 mM MgSO4, 0.1 % Tween 20, 0.8 M betaine, 8 U Bst DNA polymerase, 1.4 mM dNTPs, and 4.0 μM SYTO® 9 Green intercalating dye, 8 U RNase inhibitor | 60–65 | 6 primers: FIP 1.6 μM BIP 1.6 μM Loop-F 0.8 μM Loop-B 0.8 μM F3 0.2 μM B3 0.2 μM |

| RPA (recombinase polymerase amplification) | TwistDX (Cambridge, UK) | Rehydration buffer 30 μl Freeze-dried reaction mix Template + H2O to 47.5 μl total volume, 4.0 μM SYTO® 9 Green intercalating dye; Add 2.5 μl of 280 mM MgActo initiate reaction, 8 U RNase inhibitor |

37–40 | 2 primers: primer A 10 μM primer B 10 μM |

| NASBA (nucleic acid sequence based amplification) | Biomérieux (Durham, NC) | 5 μl enzyme mix (RNase H, T7-RNA polymerase, reverse transcriptase), 10 μl NASBA buffer + 5 μl sample, 4.0 μM SYTO® 9 Green intercalating dye, 8 U RNase inhibitor | 55–60 | 2 primers primer F 0.2 μM primer R 0.2 μM |

Positive Controls and their primers are included in these kits

Reverse transcriptase is added to reaction mix for RNA targets, e.g., 0.63 U AMV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA)

3.4. Fluorescent Reporters

Fluorescence detection of the amplification products requires a nucleic acid binding dye [78] or a molecular beacon [79] as a reporter of amplicons. For real-time detection, the dye or beacon is included in the amplification reaction mix. The intercalating dye nonspecifically binds the double-stranded amplification product as well as sample “background” DNA co-isolated with the target, and any artifacts such as primer-dimers or misprimed amplicons. The fluorescence emission signal monotonically increases as more amplicons are produced. Molecular beacons work by hybridization of a doubly functionalized (fluorophore and quencher) oligo probe to the amplicon, such that quenching of the fluorophore by the otherwise proximal quencher is relieved, and a fluorescence signal proportional to amplicons concentration is produced. Molecular beacons generally produce weaker fluorescence than intercalating dyes but are less prone to nonspecific targeting. The selection of a particular reporter determines the excitation and emission wavelengths of the fluorescence, which informs the choice of light source, detector spectral response, spectral optical filters (if needed), and spectral transparency range of the chip material. A few common fluorescent reporters that can be used in these devices are listed in Table 5. These dyes are selected for their known compatibility with enzymatic amplification, i.e., they are not strong inhibitors of PCR or isothermal amplification at the recommended dye concentrations. Too high a dye concentration can, however, inhibit amplification. The autofluorescence of the plastic chip material creates a background signal (see below). The NA-binding membrane material also fluoresces and must be excluded from the detector’s field of view. The active area of the chip for fluorescence detection can be framed with opaque (non-fluorescing) tape. We have also successfully used molecular beacon probes based on fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) to measure amplicon production.

Table 5.

A few fluorescent reporters for real-time amplification

| Dye | Mechanism | Excitation wavelength (nm) |

Emission wavelength (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethidium bromide | Intercalation of ds-DNA | 300/360 | 590 |

| Loop-Amp Fluorescent (calcein) | Amplification phosphate by product binds Mg and induces fluorescence | 240–370 340 (peak) |

515 |

| SYBR Green I | Intercalation of ds-DNA | 497 | 520 |

| SYTO-9 | Intercalation of ds-CNA | 485 | 498 |

| EvaGreen™ | Hybridization/intercalation | 490 | 530 |

3.5. Real-Time Detection

On-chip real-time detection of amplicons requires: (1) an excitation light source with spectral emission that matches the strong absorption band of the fluorophore; (2) the transmission of the excitation light into the amplification chamber(s); (3) filtering out the excitation spectra to prevent its detection; and (4) the detection of the (longer wavelength) light emitted from the reaction chamber with a detector having appropriate spectral responsivity. Various approaches to fluorescence detection on chips are feasible [80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85]. To detect the fluorescence signal on the chip, we have used either (1) a commercial compact fluorometer such as the Qiagen ESE Fluo-Sens reader (Model ESE Model ESML 10-MB-3007 with 520 nm excitation and silicon photodiode detector); (2) a portable (palm-sized) fluorescence microscope (DinoLite™ Model AM4113TGFBW) with seven built-in blue LEDs for illumination, an emission filter with a 510-nm wavelength cutoff, a CCD camera detection, and a USB connection; and (3) a cell phone camera in conjunction with LED excitation and an appropriate filter. Both the Qiagen ESE reader and the portable fluorescence microscope have their own excitation sources and optical filters and are suitable for detection with SYTO Green, SYBR Green, and EVA Green dyes. The Qiagen ESE reader can view only one reactor at a time and must be mounted on a scanner when the chip houses an array of reactors. In contrast, the USB-based microscope and the CCD camera can monitor multiple reactors simultaneously and do not require scanning. Both the USB-based microscope and the smartphone camera require imaging software (e.g., ImageJ® or MATLAB®) to quantify and process the detected signal. Given the ubiquity of cell phones even in Third World countries, the use of a cell phone is an attractive option. By taking advantage of mobile devices, we can reduce the cost of the instrumentation needed for the diagnostic devices while at the same time providing the ability of transferring test results wirelessly to a centralized depository for archiving, analysis, and public health monitoring.

For smart cell phone-based detection, one can illuminate the edge of the chip with blue light LED or laser. The light is guided into the reaction chambers through the transparent chip material. Lensing and waveguide structures can also be formed in the chip during the microfluidic circuit machining process to attain more uniform excitation of the reactor array [86]. LEDs with emission wavelengths of 450–500 nm are needed to excite many of the common dyes (Table 5). Unfortunately, many nominally “blue” LEDs have a significant green component that overlaps with the emission of the fluorophore. To minimize interference from the excitation source, suitable bandpass and longpass colored glass or interference coating optical filters (Thor Labs, Newton, NJ or Edmund Scientific, Barrington, NJ) must be used to block excitation light from the detector. For example, when using blue emission (450–500 nm), we employed a Thor Labs LED465E filter (2.5-mm diameter, nominal emission peak at 465 nm with spectral FWHM, full-width half maximum of 50 nm). Note that the plastic chip materials are not very transmissive for UV (for dyes such as EtBr or calcein), so waveguiding light into the edge of the chip may not be always feasible. As an alternative to fluorescence-based detection, several colorimetric and turbidity assays have been reported for isothermal amplification [87, 88].

3.6. Plasma Extraction from Whole Blood Using a Filtration Module

For the analysis of blood samples, plasma is first separated from whole blood. Traditionally, plasma is separated from blood by centrifugation. Centrifugation is, however, inappropriate for on-site applications. As an alternative means, we developed a passive, low-cost, pump-free separator (Fig. 4) that utilizes both sedimentation and filtration to extract plasma from whole blood [89]. The sedimentation process reduces the concentration of the cells in the blood that is then filtered through an asymmetric plasma separation membrane (polysulfone, Vivid™ GR, Pall Corp., Port Washington, NY). Red cells, white cells, and platelets are trapped without lysis in the large pores on the upstream side of the membrane. The plasma outflows through the smaller pores on the membrane’s downstream side. The separated plasma is collected with a pipette. The plasma separation module was tested by extracting about 275 μl of plasma from 1.8 ml of whole blood with known titer of HIV, in less than 7 min, using only a pipette to load and retrieve the sample. The plasma was then subjected to lysis to solubilize target nucleic acids from the virus (or bacteria) of interest, and processed in our microfluidic chip as described in the next section.

Fig. 4.

Plasma separation device: (a) whole blood inserted into the separator chamber, (b) sedimentation of blood components, (c) extraction of plasma. (d) A photograph of a standalone version of the plasma separation device

3.7. Chip Operation

We focus on the operation of a microfluidic module that integrates nucleic acid isolation, amplification, and detection using the multifunctional amplification reactor described above. For clarity and brevity, only manual operation of the chip is described. The sample is lysed off-chip by mixing it with a chaotropic salt (guanidinium chloride) and other optional lysing agents (e.g., detergents, proteinase K, lysozyme). The lysis deactivates any infectious agents in the sample as well as nucleases that might degrade target NAs. The lysate is then pipetted through the membrane and the reaction chamber (see Note 3). The chaotropic salt promotes binding of the nucleic acids to the membrane. The membrane-bound nucleic acids are then washed with buffer to remove debris and inhibitors. In the normal mode of solid-phase extraction (i.e., spin column), the captured nucleic acids are eluted from the membrane into the amplification chamber with a low-salt, pH-neutral buffer. In contrast, in our device, we simplify the process by forgoing a separate elution step. The membrane is sited at the inlet of the amplification chamber and is in contact with the amplification reaction mixture. The membrane-bound nucleic acids serve directly as templates for amplification. An important advantage of this configuration is that the sample volume (the amount of lysate filtered through the membrane) is largely decoupled from the volume of the amplification reaction. Nevertheless, there is an optimum membrane size for a given sample volume and amplification chamber size. The membrane must be large enough to capture a high fraction of the NA from the perfusing lysate, but not too large as to impede desorption of captured NA during amplification. Also, the silica-based membrane material partially inhibits enzymatic amplification. The cellulose-based FTA membrane shows a better compatibility with enzymatic amplification, i.e., less inhibition of amplification. We speculate that inhibition of amplification by the membrane material results from irreversible adsorption of template, primers, and/or polymerase to the membrane since experience teaches that inhibition effects are reduced when the concentrations of these three components are increased in the reaction mix.

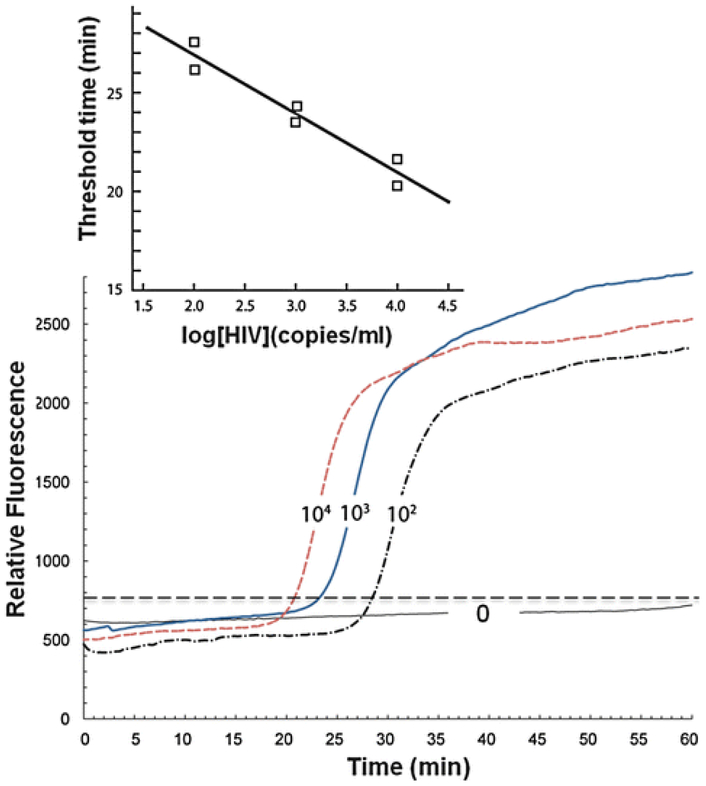

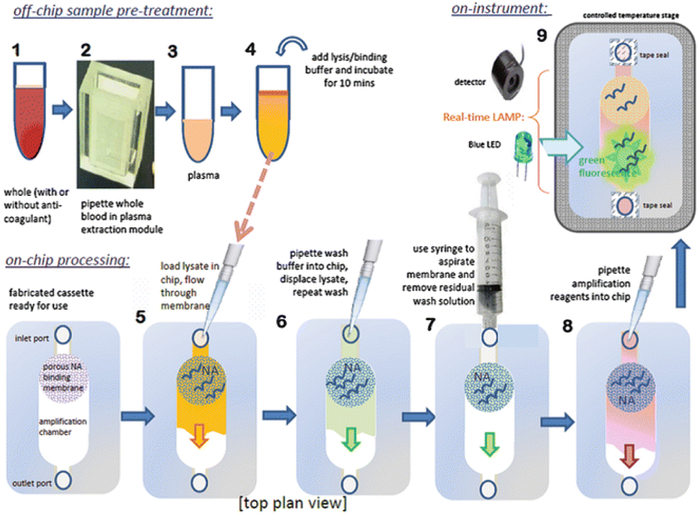

As an example of the chip operation, we describe the detection of HIV virus in blood. The various processing steps are depicted schematically in Fig. 5. Plasma separated from whole blood was subjected to a chemical lysis step using a combination of chaotropic salts, detergents, and enzymes. Nucleic acids were isolated from the lysate by solid-phase extraction, and the purified, concentrated, immobilized nucleic acids were subjected to sequence-specific enzymatic amplification using targeted oligo primer sequences. The production of amplicon was then monitored by a DNA-binding fluorescent dye (Fig. 6). Troubleshooting for Amplification/Detection Step: See Notes 4–6.

Fig. 5.

Processing steps for plasma extraction and microfluidic NAT

Fig. 6.

An example of real time detection. Fluorescence emission intensity as a function of time when the sample contains 0 (negative control), 102, 103, and 104 HIV copies/ml. (Inset) The threshold time as a function of HIV concentration

3.8. Steps for a Blood Sample Molecular Analysis on a Chip

-

1. 1.

A blood sample laden with the suspected pathogen (e.g., HIV virus), ranging in volume from 100 μl to 1 ml (depending on the required limit of detection), is inserted into the plasma separator. The plasma separator utilizes a combination of filtration and sedimentation to separate the plasma from the blood.

-

2. 2.

Add 4 volumes of lysis/binding buffer to 1 volume of plasma (e.g., add 400 μl lysing buffer to 100 μl plasma) and incubate for 10 min at room temperature.

-

3. 3.

Optionally, add carrier RNA suspension (20 ng per sample) to the lysis buffer.

-

4. 4.

Pipette a volume of lysate (50–500 μl) into the chip, perfusing the membrane.

-

5. 5.

Pipette 100 μl ethanol-based wash solution through the membrane, washing the membrane.

-

6. 6.

Repeat the wash step above.

-

7. 7.

Dry the membrane to remove residual ethanol by aspirating or blowing dry air through inlet port with a 10-ml syringe.

-

8. 8.

Inject amplification mix (with correct proportion of enzymes, primers, nucleotides, salts, and dye) into the reactor as proportioned for volume of amplification chamber. Flow the reaction mix through the membrane and fill the amplification chamber.

-

9. 9.

Seal the chip inlet and outlet with PCR sealing tape.

-

10. 10.

For isothermal LAMP amplification, incubate chip at 65 °C on a hotplate. (Use a “dummy” calibration chip with embedded thermocouple to adjust hotplate settings.) Foam rubber can be placed around the chip (with portal opening for camera) to reduce temperature fluctuations from ambient room drafts.

-

11. 11.

Excite the fluorescent dye and monitor the emission with either a fluorometer or a camera.

-

12. 12.

(optional) If desired, a melting curve can be constructed to verify that the melting temperature is consistent with the expected amplicons. Alternatively, the amplification products can be removed from the reaction chamber and subjected to gel electrophoresis to verify that the size of the amplicons is consistent with expectations. As yet another option, instead of real time detection, the amplification products (when the primers are appropriately functionalized) can be run on a lateral flow strip for end point detection.

3.9. Analysis

Real-time fluorescence emission intensity as a function of amplification time for a LAMP-based chip is shown in Fig. 6. The curves correspond to samples spiked with different HIV virus concentrations and have a characteristic sigmoidal shape (similar to real-time PCR). The rapid increase in the fluorescence intensity occurs sooner as the number of target copies in the sample increases [47]. In other words, the threshold time needed to observe emission intensity above background level can be correlated with the concentration of target copies in the sample (Fig. 6, inset). The threshold time is a linear function of the logarithm of the target concentration. By developing appropriate calibration curves, one can infer the unknown number of virus copies in a sample. The results indicate that our cassette’s detection limit is smaller than 1,000 HIV copies/ml.

3.10. Conclusion and Discussion

The microfluidic module and protocol for nucleic acid isolation and amplification described here are a convenient alternative to benchtop molecular assays. The microfluidic device combines nucleic acid isolation typically done using commercial spin column kits with enzymatic amplification and detection as conventionally done in Eppendorf tubes in a benchtop thermal cycler instrument. A sample can be processed in the microfluidic chip in less than an hour. In several applications, such as analysis of an RNA virus in blood plasma, limits of detection comparable to benchtop assays (<1,000 virus particles per ml sample) have been realized. This “lab-on-a-chip” approach is attractive for processing of a small number of samples. More importantly, the microfluidic module described here can serve as a component of an autonomous, portable, on-site molecular diagnostic system. Such next-generation devices may incorporate programmed fluidic actuation and flow control, as well as smartphone detection of amplicons’ fluorescence emission. Chips, preloaded with lyophilized reagents, primers for a specified target, and buffers, could be hermetically packaged, barcoded, and stored (without refrigeration) with a shelf-life of a year or more. Chips, customized for various targets, could operate with the same portable processor. A simple filtration separation device that extracts plasma samples from whole blood for microfluidic nucleic acid testing could be combined with the NAT chip into a single integrated microfluidic cartridge. The chip designs are compatible with high-volume, low-cost injection molding, and a microfluidic test cartridge is projected to cost several dollars per test. As such, this approach may make molecular diagnostics feasible in doctors’ and dentists’ offices, home settings, clinics, ambulances, hospital bedsides, laboratory animal facilities, food processing and retail outlets.

4. Notes

-

1. 1.

Chip delamination or leaks may be the result of poor bonding. Weak bonds may result from inadequate cleaning of the chip materials prior to bonding. Fortunately, the use of relatively low-temperature (≤65 °C) isothermal amplification as distinguished from PCR (rapid thermal cycling up to 95 °C) imposes less stress on the chips, and delamination and leak problems are rare in these isothermal amplification chips.

-

2. 2.

Addition of “carrier” RNA to the sample often proves helpful and sometimes crucial, especially for samples with a low number of target molecules. Lyophilized poly-A RNA (approx. 20 ng per sample) is added to the sample to improve NA isolation yield [90, 91, 92]. This may be beneficial due to one or a combination of several effects: (1) the carrier RNA acts as a sacrificial substrate for RNAases that would otherwise degrade the template; (2) the carrier RNA enhances precipitation and binding of NA to the solid-phase membrane, and (3) small amounts of NA are strongly and irreversibly adsorbed on the NA binding phase and cannot be desorbed to serve as templates for amplification. The added carrier RNA occupies the strong binding sites on the NA membrane, so that the weakly bound target NA can be desorbed. The effect of carrier RNA appears to help DNA analysis as well.

-

3. 3.

Air bubbles in the fluids may interfere with NA isolation and amplification, so introduction of air bubbles should be avoided when pipetting liquids into the chip.

-

4. 4.No amplification observed from positive controls. Possible causes include:

-

1. (a)The template has degraded. If sufficient amount of material is available, obtain gel electropherograms of the template. RNA samples are most susceptible to degradation. To avoid contamination, extract amplicons for gel analysis as remotely as possible from where the LAMP reagents are prepared and loaded into the chips (see below).

-

2. (b)Reagents are spoiled. Many kits combine reagent components so only mixtures of components can be tested. Reverse transcriptase is most susceptible to degradation and is the component that should be examined first.

-

3. (c)Inhibitors persist. The solid-phase extraction process should generally remove inhibitors. Inhibitors may be intrinsic to the sample and/or to the chip due to residual bonding solvent left over in the chip or membrane or due to residual ethanol. Sample dilution will reduce the concentration of inhibitors and help mitigate the effects of sample inhibitors. Increasing membrane drying duration will help to remove any residual ethanol left over from the wash steps. In the case of blood samples, anticoagulants (e.g., EDTA chelates Mg needed for polymerases) may interfere with the amplification process. Proteinase K and other lysing agents may degrade polymerases, and unlike in PCR, there is no high temperature heating (>90 °C) in the isothermal amplification process to inactivate nucleases and proteinases. If certain lysing agents are suspected of inhibiting amplification, their necessity in the protocol should be reconsidered, or else more rigorous washes (repetitions and greater total wash buffer volume) should be used to enhance their removal.

-

4. (d)Incorrect or suboptimal incubation temperature. Temperature overshoots of 10 °C over the recommended incubation temperature can degrade enzymes. Verify there is no overshoot in temperature during heat-up which may abolish enzyme activity. Also, too low a temperature will reduce amplification efficiency.

-

1. (a)

-

5. 5.Limit of detection in the chip is significantly lower than parallel benchtop assay. Possible causes:

-

1. (a)Non-optimal temperature control. Check amplification reactor temperature with a calibration chip equipped with temperature sensor.

-

2. (b)Fluorescent dyes degraded. Dyes lose their fluorescence over time due to bleaching and excessive freeze-thaw. Minimize exposure of dyes to light as much as possible. Dyes can be mixed with calibration DNA (such as gel marker ladders) and tested in chip with fluorometer.

-

3. (c)Low NA yield. Add more carrier RNA to the sample to improve yield of on-chip NA isolation. Check NA yield: Assay nucleic acid captured on the NA binding membrane by eluting with 10–50 μl of warm (−50 °C) water or TE buffer, and measure (total) NA concentration and purity (260/280 ratio) with a spectrophotometer (e.g., Nanodrop™, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, Delaware) or fluorometer (TBS-380 with PicoGreen™ dye for DNA and RiboGreen™ dye for RNA, Turner Bio Systems, Sunnyvale, California). Since depending on sample matrix, (total) NA can range from hundreds of picograms to hundreds of nanograms, it is probably more meaningful to compare chip NA yields to spin-column yields of comparable samples.

-

1. (a)

-

6. 6.Amplification is detected for nominally negative samples/controls. Possible causes include:

-

1. (a)Primer-dimer or nonspecific amplification is creating a false signal. Run amplification product on gel or produce a melting curve in a benchtop PCR to verify that the amplification product has the expected size.

-

2. (b)Excessive incubation time may lead to the production of artifacts such as primer dimers. When using LAMP, limit the duration of the amplification process to less than 45 min.

-

3. (c)Excess Mg results in nonspecific amplification. Adjust Mg concentration according to manufacturer’s protocol for amplification. Note that EDTA and some other anticoagulants used in blood samples are chelators for Mg.

-

4. (d)Contamination from previous runs. Due to their very high efficiency, the isothermal amplification techniques are particularly sensitive to contamination. This problem affects the assay developers, not on-site users. As a precaution, we prepare reagents and load the chips in separate labs and use dedicated pipettes. Chips should be left sealed after amplification to avoid the spreading of any amplicons. Gel electrophoresis of amplification product creates an aerosol of amplicons, and so should be done as far away from the sample prep and test area as possible. Experience shows that molecular biology grade water is often the source of contamination. When you purchase primers, aliquot the primers (25–50 runs worth) and cold store separately (preferably in a distant lab) to avoid contaminating the entire primer batch. Unfortunately, once the lab area is contaminated with amplicons, it may prove difficult to alleviate, so constant diligence is strongly advised.

-

1. (a)

Acknowledgments

The work reported here was supported, in part, by NIH Grants U01DE017855 (Bau, Mauk) and K25AI099160 (Liu), and a grant from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s Ben Franklin Technology Development Authority through the Ben Franklin Technology Partners of Southeastern Pennsylvania (Bau, Sadik).

References

- 1.Olasagasasti F, Ruiz de Gordoa J (2012) Miniaturized technology for protein and nucleic acid point-of-care testing. Transl Res 160(5)1332–345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weigl B, Domingo G, LaBarre P, Gerlach J (2008) Towards non- and minimally instrumented, microfluidics-based diagnostics devices. Lab Chip 81:1999–2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang S, Xu F, Demirci U (2010) Advances in developing HIV-1 viral load assays for resource-limited settings. Biotechnol Adv 28:770–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chin CD, Linder V, Sia SK (2012) Commercialization of microfluidic point-of-care diagnostic devices. Lab Chip 12:2118–2134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers FB, Henrikson RH, Bone J, Lee LP (2013) A handheld point-of-care genomic diagnostic system. PLoS One 8(8):e70266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giljohann DA, Mirkin CA (2009) Drivers of biodiagnostic development. Nature 402(26):461–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gubala V, Harris LF, Ricco AJ, Tan MX, Williams DE (2012) Point of care diagnostics: status and future. Anal Chem 84(2):487–515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu E, Yager P, Fioriano PN, Christodoulides N, McDevitt J (2011) Perspectives on diagnostics for global health. IEEE Pulse 2(6):40–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mairfair J, Roppert K, Ertl P (2009) Microfluidic systems for pathogen sensing: a review. Sensors 9:4804–4823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mondal S, Venkataraman V (2007) Miniaturized devices for DNA amplification and fluorescence based detection. J Indian Inst Sci 87(3):309–332 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoon J-Y, Kim B (2012) Lab-on-a-chip pathogen sensors for food safety. Sensors 12:10713–10741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tourlousse DM, Ahmad F, Stedtfeld RD, Seyrig G, Tiedje JM, Hashham SA (2012) A polymer microfluidic chip for quantitative detection of multiple water and foodborne pathogens using real-time fluorogenic loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biomed Microdevices 14:769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sakamoto C, Yamaguchi N, Yamada M, Nagase H, Seki M, Nasu M (2007) Rapid quantification of bacterial cells in potable water using a simplified microfluidic device. J Microbiol Methods 68:643–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lochhead MJ, Todorof K, Delaney M, Ives JT, Greef C, Moll K, Rowley K, Vogel K, Myatt C, Zhang X-Q, Logan C, Benson C, Reed S, Schooley RT (2011) Rapid multiplexed immunoassay for simultaneous serodiagnosis of HIV-1 and coinfections. J Clin Microbiol 49(10):3584–3590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin C-C, Wang J-H, Wu H-W, Lee G-B (2010) Microfluidic immunoassays. J Lab Autom 15:253–274 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngom B, Guo Y, Wang X, Bi D (2010) Development of lateral flow strip technology for detection of infectious agents and chemical contaminants. Anal Bioanal Chem 397(3):1113–1135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Al-Soud WA, Rådström P (2001) Purification and characterization of PCR-inhibitory components in blood cells. J Clin Microbiol 39(2)1485–493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Opel KL, Chang D, McCord BR (2010) A study of PCR inhibition mechanisms using real time PCR. J Forensic Sri 55(1):25–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiedbrauk DL, Werner JC, Drevon AM (1995) Inhibition of PCR by aqueous and vitreous fluids. J Clin Microbiol 33(10):2043–3046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burns DE, Ashwood ER, Burtis CA (2007) Fundamentals of molecular diagnostics. Saunders, St. Louis [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C, Xing D (2007) Minaturized chips for nucleic acid amplification and analysis: latest advances and future trends. Nucleic Acids Res 35(13):4223–4237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park S, Zhang Y, Lin S, Wang T-H, Yang S (2011) Advances in microfluidic PCR for point-of-care infectious disease diagnostics. Biotechnol Adv 29:830–839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J-G, Cheong KH, Huh N, Kim S, Choi J-W, Ki C (2006) Microchip-based one step DNA extraction and real-time PCR in one chamber for rapid pathogen identification. Lab Chip 6:886–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Chen Z, Corstjens PL, Mauk MG, Bau HH (2006) A disposable microfluidic cassette for DNA amplification and detection. Lab Chip 6(1):146–53 ( 10.1039/b511494b) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Z, Mauk MG, Wang J, Abrams WR, Corstjens PL, Niedbala RS, Malamud D, Bau HH (2007) A microfluidic system for saliva-based detection of infectious diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1098:429–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen D, Mauk M, Qiu X, Liu C, Kim J, Ramprasad S, Ongagna S, Abrams WR, Malamud D, Corstjens PLAM, Bau HH (2010) An integrated, self-contained microfluidic cassette for isolation, amplification, and detection of nucleic acids. Biomed Microdevices 12(4):705–719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qiu X, Mauk MG, Chen D, Liu C, Bau HH (2010) A large volume, portable, real-time PCR reactor. Lab Chip 10(22):3170–3177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qiu X, Chen D, Liu C, Mauk MG, Kientz T, Bau HH (2011) A portable, integrated analyzer for microfluidic-based molecular analysis. Biomed Microdevices 13:809–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu C, Mauk MG, Hart R, Qiu X, Bau HH (2011) A self-heating cartridge for molecular diagnostics. Lab Chip 11:2686–2692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chang C-C, Chen C-C, Wei S-C, Lu H-H, Liang Y-H, Lin C-W(2012) Diagnostic devices for isothermal nucleic acid amplification. Sensors 12:8319–8337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duarte C, Salm E, Dorvel B, Reddy B Jr, Bashir R (2013) On-chip parallel detection of foodborne pathogens using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Biomed Microdevices 15(5):821–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fang X, Liu Y, Kong J, Jiang X (2010) Loop-mediated isothermal amplification integrated on microfluidic chips for point-of-care quantitative detection of pathogens. Anal Chem 82:3002–3006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu Q, Jin W, Zhou C, Han S, Yang W, Zhu Q, Jin Q, Mu Y (2011) Integrated glass microdevice for nucleic acid purification, loop-mediated isothermal amplification, and online detection. Anal Chem 83:3336–3342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L-Y, Jin W, Zhu Q-Y, Yang W-X, Wu Q-Q, Jin Q-H, Mu Y (2011) Real-time detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction on microfluidic chip. 2011 5th International conference on bioinformatics and biomedical engineering, Wuhan, China, IEEE, Piscataway, New Jersey, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Notomi T, Okayama H, Masubuchi H, Yonekawa T, Watanabe K, Amino N, Hase T (2000) Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 28(12):E63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T (2013) Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP): recent progress in research and development. J Infect Chemother 19(3):404–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parida M, Posadas G, Inoue S, Hasebe F, Morita K (2004) Real-time reverse transcription loop-mediated isothermal amplification for rapid detection of West Nile virus. J Clin Microbiol 42(1):257–263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curtis KA, Rudoph DL, Owen SM (2008) Rapid detection HIV-1 by reverse-transcription, loop-mediated isothermal amplification (RT-LAMP). J Virol Methods 151:264–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Compton J (1991) Nucleic acid sequence-based amplification. Nature 350:91–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gulliksen A, Solli LA, Drese KS, Sörensen O, Karlsen F, Rogne H, Hovig E, Sirevåg R (2005) Parallel nanoliter detection of cancer markers using polymer chips. Lab Chip 5(4):416–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piepenburg O, Williams CH, Stemple DL, Ames NA (2006) DNA detection using recombination proteins. PLoS Biol 4(7):e204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lutz S, Weber P, Focke M, Faltin B, Hoffman J, Müller C, Mark D, Roth G, Munday P, Armes N, Piepenberg O, Zengerle R, von Stetten F (2010) Microfluidic lab-on-foil for nucleic acid analysis based on isothermal recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA). Lab Chip 10:887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vincent M, Xu Y, Kong H (2004) Helicase-dependent isothermal DNA amplification. EMBO Rep 5(8)1795–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chow WH, McCloskey C, Tong Y, Hu L, You Q, Kelly CP, Kong H, Tang YW, Tang W (2008) Application of isothermal helicase-dependent amplification with a disposable detection device in a simple sensitive stool test for toxigenic Clostridium difficile. J Mol Diagn 10(5)1452–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mahalanabis M, Do J, Al-Muayad H, Zhang JY, Klapperich CM (2010) An integrated disposable device for DNA extraction and helicase dependent amplification. Biomed Microdevices 12:353–359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francois P, Tangomo M, Hibbs J, Bonetti E-J, Boehme CC, Notomi T, Perkins MD, Shrenzel J (2011) Robustness of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction for diagnostics applications. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 62:41–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu C, Geva E, Mauk MG, Qiu X, Abrams WR, Malamud D, Curtis K, Owen SM, Bau HH (2011) An isothermal amplification reactor with an integrated isolation membrane for point-of-care detection of infectious diseases. Analyst 136:2069–2076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu C, Mauk MG, Hart R, Bonizzoni M, Yan G, Bau HH (2012) A low-cost microfluidic chip for rapid genotyping of malaria-transmitted mosquitoes. PLoS One 7(8):e42222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stevens DY, Petri CR, Osborn JL, Spicar-Mihalic P, McKenzie KG, Yager P (2008) Enabling a microfluidic immunoassay for the developing world by integration of on-card dry reagent storage. Lab Chip 8(12):2038–2045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fridley GE, Le HQ, Fu E, Yager P (2012) Controlled release of dry reagents in porous media for tunable temporal and spatial distribution upon rehydration. Lab Chip 12(21):4321–4327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hitzbleck M, Gervais L, Delamarche E (2011) Controlled release of reagents in capillary-driven microfluidics using reagent integrators. Lab Chip 11:2680–2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kim J, Byun D, Mauk MG, Bau HH (2009) A disposable, self-contained PCR chip. Lab Chip 9(4):606–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim J, Mauk MG, Chen D, Qiu X, Kim J, Gale B, Bau HH (2010) A PCR reactor with an integrated alumina membrane for nucleic acid isolation. Analyst 135:2408–2414 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziober B, Mauk M, Chen Z, Bau HH (2008) Lab-on-a-chip for oral cancer screening and diagnosis. Head Neck 30(1):111–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Becker H, Gärtner C (2008) Polymer microfabrication technologies for microfluidic systems. Anal Bioanal Chem 390:89–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Black I (1998) Laser cutting of perspex. J Mater Sci Lett 17:1531–1533 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pfleging W, Baldus O (2006) Laser patterning and welding of transparent polymers for microfluidic device fabrication. Laser-based micropackaging. Proc SPIE 6107:e610705 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Steigert J, Haeberle S, Brenner T, Müller C, Steinert CP, Koltay P, Gottschlich N, Reinecke H, Rühe J, Zengerle R, Ducrée J (2007) Rapid prototyping of microfluidic chips in COC.J Micromech Microeng 17:333–341 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Snakenborg D, Klank H, Kutter JP (2004) Microstructure fabrication with a CO2 laser system. J Micromech Microeng 14:182–189 [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tsao C-W, DeVoe DL (2009) Bonding of thermoplastic polymer microfluidics. Microfluid Nanofluid 6:1–16 [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hsu Y-C, Chen T-Y (2007) Applying Taguchi methods for solvent-assistant PMMA bonding technique for static and dynamic μ-TAS devices. Biomed Microdevices 9:513–522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Umbrecht F, Müller D, Gattiker F, Boutry CM, Neuenschwander J, Sennhauser U, Hierold C (2009) Solvent assisted bonding of polymethylmethacrylate: characterization using the response surface methodology. Sens Actuators A Phys 156:121–128 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kodzius R, Xiang K, Wu J, Yi X, Gong X, Foulds IG, Wen W (2012) Inhibitory effect of common microfluidic materials on PCR. Sens Actuators B 161:349–358 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Giordano BC, Copeland ER, Landers JP (2001) Towards dynamic coating of glass microchip chambers for amplifying DNA via polymerase chain reaction. Electrophoresis 22:334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gonzalez A, Grimes R, Walsh EJ, Dalton T, Davies M (2007) Interaction of quantitative PCR with polymeric surfaces. Biomed Microdevices 9:261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lou XJ, Panaro NJ, Wilding P, Fortina P, Kricka LJ (2004) Increased amplification efficiency of microchip-based PCR by dynamic surface passivation. Biotechniques 36:248–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piruska A, Nikcevic I, Lee SH, Ahn C, Heineman WR, Limbach PA, Seliskar CJ (2005) The autofluorescence of plastic materials and chips measured under laser fluorescence. Lab Chip 5:1348–1354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Boom R, Sol CJ, Salimans MM, Jansen CL, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, van der Noordaa J (1990) Rapid and simple method for purification of nucleic acids. J Clin Microbiol 28:495–503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Greenfield L, White TJ (1993) Sample preparation methods In: Persing DH, Smith TF, Tenover FC, White TJ (eds) Diagnostic molecular biology: principles and applications. American Soc. Microbiology, Washington, DC, pp 122–137 [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kemp BM, Monroe C, Smith DG (2006) Repeat silica extraction: a simple technique for the removal of PCR inhibitors from DNA extracts. J Archaeol Sci 33:1680–1689 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Breadmore MC, Wolfe KA, Arcibal IG, Leung WK, Dickson D, Giordano BC, Power ME, Ferrance JP, Feldman SH, Norris PM, Landers JP (2003) Microchip-based purification of DNA from biological samples. Anal Chem 75:1880–1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen X, Cui DF, Liu C (2006) High purity DNA extraction with a SPE microfluidic chip using KI as the binding salt. Chin Chem Lett 17(8):1101–1104 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen X, Cui D, Sun J, Zhang L, Li H (2013) Microdevice-based DNA extraction method using green reagent. Key Eng Mater 562–565:1111–1115 [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cady NC, Stelick S, Batt CA (2003) Nucleic acid purification using microfabricated structures. Biosens Bioelectron 30(19):159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wen J, Legendre LA, Bienvenue JM, Landers JP (2008) Purification of nucleic acids in microfluidic devices. Anal Chem 80:6472–6479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wolfe KA, Breadmore MC, Ferrance JP, Power ME, Conroy JF, Norris PM, Landers JP (2002) Toward a microchip-based solid-phase extraction method for isolation of nucleic acids. Electrophoresis 23:727–733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chung YC, Jan M-S, Lin Y-C, Lin J-H, Cheng W-C, Fan C-Y (2004) Microfluidic chip for high efficiency DNA extraction. Lab Chip 4:141–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gudnason H, Dufva M, Bang DD, Wolff A (2007) Comparison of multiple DNA dyes for real-time PCR: effects of dye concentration and sequence composition on DNA amplification and melting temperature. Nucleic Acids Res 35(19):e127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Leone G, van Schijndel H, van Gemen B, Kramer FR, Schoen CD (1998) Molecular beacon probes combined with amplification by NASBA enable homogeneous, real-time detection of RNA. Nucleic Acids Res 20(9):2150–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lee D-S, Chang B-H, Chen P-H (2005) Development of a CCD-based fluorimeter for real-time PCR machine. Sens Actuators B 107:872–881 [Google Scholar]

- 81.Walczak R, Bembnowicz P, Szczepanska P, Dziuban JA, Golonka L, Koszur J, Bang DD (2008), Miniaturized system for real-time PCR in low-cost disposable LTCC chip with integrated optical waveguide. Twelfth Int’l conference on miniaturized systems for chemistry and the life sciences, San Diego, pp 1078–1080 [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhu H, Yaglidere O, Su T-W, Tseng D, Ozcan A (2011) Cost-effective and compact wide-field fluorescent imaging on a cell-phone. Lab Chip 11:315–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lee D-S, Chou WP, Yeh SH, Chen PJ, Chen PH (2011) DNA detection using commercial mobile phones. Biosens Bioelectron 26:4349–4354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ahmad F, Seyrig G, Tourlousse DM, Stedtfeld RD, Tiedje JM, Hashsham SA (2011) A CCDbased fluorescence imaging for real-time loop-mediated isothermal amplification-based rapid and sensitive detection of waterborne pathogens on microchips. Biomed Microdevices 13:929–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Myers FB, Lee LP (2008) Innovations in optical microfluidic technologies for point-of-care diagnostics. Lab Chip 8:2015–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ogilvie IRG, Sieben VJ, Floquet CFA, Zmijan R, Mowlem MC, Morgan H (2010) Reduction of surface roughness for optical quality microfluidic devices in PMMA and COC.J Micromech Microeng 20:065016 [Google Scholar]

- 87.Goto M, Honda E, Ogura A, Nomoto A, Hanaki K (2009) Colorimetric detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction using hydroxy naphthol blue. Biotechniques 46(3):167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tomita N, Mori Y, Kanda H, Notomi T (2008) Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) of gene sequences and simple visual detection of products. Nat Protoc 3(5):877–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Liu C, Mauk M, Gross R, Bushman FD, Edelstein PH, Colman RG, Bau HH (2013) Membrane-based, sedimentation-assisted plasma separator for point-of-care applications. Anal Chem 85:10463–10470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Gallagher ML, Burke WF Jr, Orzech K (1987) Carrier RNA enhancement of recovery from dilute solutions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 144(1):271–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Shaw KJ, Thain L, Docker PT, Dyer CE, Greenman J, Greenway GM, Haswell SJ (2009) The use of carrier RNA to enhance DNA extraction from microfluidic-based silica monoliths. Anal Chim Acta 652:231–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Shaw KJ, Oakley J, Docker PT, Dyer CE, Greenman J, Greenway GM, Haswell SJ (2008) DNA extraction, using carrier RNA, integrated with agarose gel-based polymerase reaction in a microfluidic device. Twelfth international conference on miniaturized systems in chemistry and the life sciences, San Diego, pp 1069–1071 [Google Scholar]