Abstract

Introduction

Polyp detection rate is a surrogate marker for adenoma detection rate and therefore a surrogate marker of quality colonoscopy. To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares distance from the monitor to the endoscopist on polyp detection rate.

Methods

This was a retrospective study comparing polyp detection rate across two different endoscopy room set-ups. All colonoscopies performed between December 2013 and November 2014 were retrieved. The difference in the room set-up was the distance from the endoscopist to the endoscopy monitor. Room A had a distance of 219 cm and Room B had 147 cm. We used two identical rooms, C and D, as a control arm with a distance of 190 cm between the endoscopist and the monitor.

Results

There were significant differences in polyp detection rates between Room A and Room B in the bowel cancer screening lists. For these lists, the room with the closest distance from the endoscopist to the monitor (147 cm) had a statistically significant higher polyp detection rate than the room that had a further monitor to endoscopist distance of 219 cm (p<0.0006) and a trend towards a higher polyp detection rate compared with the room where the distance between the monitor and the endoscopist was 190 cm (p=0.08). This effect was not noticed across the service lists.

Conclusions

This study has suggested that the distance from the endoscopist to the monitor can affect polyp detection rate. It appears that for bowel cancer screening lists, the further the endoscopist from the monitor the lower their polyp detection rate.

Keywords: endoscopy, polyp, adenoma

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is considered a quality marker for colonoscopy. Polyp detection rate (PDR) is a surrogate marker of ADR. Many factors have been shown to affect ADR including scope withdrawal time, bowel preparation, high-definition scopes and time of day the procedure is performed.

What this study adds

This is the first study to suggest that the set-up of the endoscopy room may also be a modifiable variable that can affect PDR. Specially, the distance from the endoscopist to the monitor may have an effect on PDR.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Optimisation of the endoscopy room set-up may be an important factor in optimising PDR rates. Future research is required to find the optimum set-up of the endoscopy room which should include the optimum distance from the endoscopist to the monitor to maximise PDR.

Introduction

Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is considered a quality marker for colonoscopy.1 The implication is that careful and optimal mucosal visualisation enhances adenoma detection and is a reliable marker of a colonoscopist performing appropriately and effectively.1 2 It has been shown that polyp detection rate (PDR) is a useful surrogate marker for ADR and therefore a surrogate marker of quality colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy.3–5 PDR has the advantage of not requiring manual entry of pathology data and correlates well with ADR in several studies.5–7

Bowel cancer is the fourth most common cancer in the UK (2014), accounting for 12% of all new cases.8 It is the third most common cancer in both men (14% of the male total) and women (11%).8 More than 90% of bowel cancer cases are adenocarcinomas and the majority of these arise from adenomatous polyps (adenomas). These common benign tumours develop from normal colonic mucosa and are present in about a third of the European and US populations.9

The more difficult to detect flat adenomas account for about 10% of all lesions and may have a greater propensity to malignant change.10 11 Only a small proportion of polyps (1%–10%) develop into invasive bowel cancer.12 Indicators for progression from adenomas to cancer include large size, villous histology and severe dysplasia.13

Target ADR should be ≥15%1 but it may be that the ideal ADR is as high as 30% for male patients as indicators of adequate colonoscopy quality.14 However, a systematic review has shown that ADR can vary widely.15 Factors that have been shown to affect ADR are withdrawal time,16 bowel preparation,17 high-definition scopes,18 technological advances in endoscopy19 and time of day the procedure is performed.20

It is therefore important to optimise as many modifiable factors to enable the highest quality endoscopy. The endoscopy room set-up itself may have a role in optimising ADR and both the Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) and the world endoscopy organisation have issued guidelines on the construction of an endoscopy unit but no standard endoscopy suite set-up has been defined.21 22 Furthermore, the effect of distance between the endoscopy monitor and the endoscopist has never been studied. To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares distance from the monitor to the endoscopist on PDR.

Methods

Study design

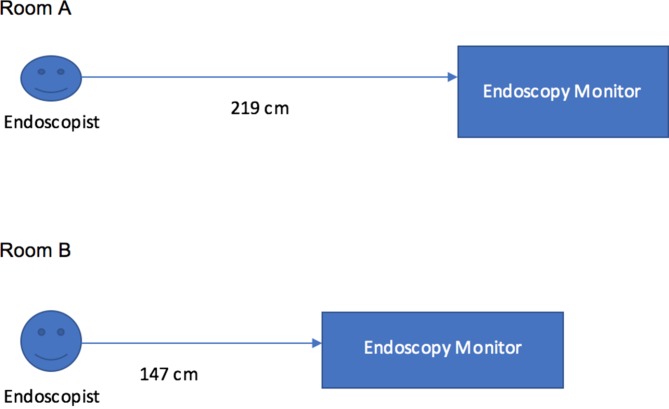

At the time of the study (2013–2014) the East and North Herts NHS Trust comprised the QE2 Hospital (Hospital 1) and the Lister Hospital (Hospital 2). This was a retrospective study comparing PDR across two different endoscopy room set-ups. The key significant difference in the room set-up was the distance from the endoscopist to the endoscopy monitor at the QE2 Hospital. Room A had a distance of 219 cm and Room B had a distance of 147 cm between the endoscopist and the monitor. The Lister Hospital had two identical rooms (Room C and Room D) which were used as a control arm and here the distance between the endoscopist and the monitor was 190 cm (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of differences between rooms at the QE2 Hospital.

Setting

All colonoscopies performed between December 2013 and November 2014 were retrieved using Clinical Information and Patient Tracking System endoscopy database (Delian Systems, Chelmsford, Essex) across two hospitals within the same NHS Trust.

Using endoscopy reports and search criteria we retrospectively compared the PDR at colonoscopy in two separate hospitals each with two endoscopy rooms over a 12-month period. Endoscopists work across both sites in both rooms.

We included 13 endoscopists in the study all of which were consultant grades. Three of the 13 endoscopists also were bowel cancer screening programme (BCSP) endoscopist and we did a further subanalysis on this group. Only endoscopists who scoped across all four rooms were included. We excluded colonoscopies done by trainees, and all colonoscopies where bowel preparation was considered ‘poor’ by the endoscopist.

Participants

Patients ≥18 years old who had a colonoscopy in either Room A, B, C or D.

We included only completed procedures which were defined as identification of at least the caecum.

Patients where bowel preparation was marked as ‘excellent’ by the endoscopist.

Incomplete procedures were excluded.

Variables

Data recorded were total procedures performed in each room, polyps detected and overall detection rate PDR.

Measurement of variables

Distance from endoscopist to monitor was measured prospectively from the fixed endoscopy monitor to the forehead of the endoscopist when standing by the bedside just before starting the colonoscopy in each room. This was measured using three different endoscopists on three different days and an average distance was taken for analysis. The distance was measured using a standard tape measure to the nearest centimetre.

Bias

Bias was minimised by using objective measurements.

Statistical methods

PDR was compared across the following rooms:

Room A versus Room B (Hospital 1).

Lister 1 versus Lister 2 (Hospital 2).

Lister (Hospital 2) versus each individual room in Hospital 1.

For each of the above comparisons, first the analyses were performed for each consultant separately. Due to the binary nature of the outcome (polyp detected, no polyp detected), the analysis was performed using logistic regression.

Subsequently, the data from all consultants were combined. To allow for the clustering of patients within consultants (who may have different PDRs), the analysis was performed using multilevel logistic regression. Two-level models were used with individual patients nested within consultants. Separate analyses were performed for service cases and those from the BCSP. Stata (StataCorp, Texas, USA) package was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Service cases

The first set of analyses compared the difference in polyp detection between endoscopy rooms for the service cases (table 1). The results suggested no strong evidence that the Room A and Room B differed for any of the individual consultants. There was slight evidence of greater polyp detection in the Room B for consultant 13, but this did not quite reach statistical significance. There was no difference between rooms when the results for all consultants were combined.

Table 1.

Polyp detection rate for room A vs room B for service lists

| Consultant | Room A PDR (n/N) |

Room B PDR (n/N) |

OR* (95% CI) |

P values |

| 1 | 60% (3/5) | 21% (3/14) | 0.18 (0.02 to 1.64) | 0.13 |

| 2 | 32% (8/25) | 33% (5/15) | 1.06 (0.27 to 4.15) | 0.93 |

| 3 | 33% (10/30) | 29% (8/28) | 0.80 (0.26 to 2.44) | 0.70 |

| 4 | 60% (3/5) | 67% (4/6) | 1.33 (0.11 to 15.7) | 0.82 |

| 5 | 28% (9/32) | 67% (4/6) | 5.11 (0.79 to 33.0) | 0.09 |

| 6 | 50% (2/4) | 38% (3/8) | 0.60 (0.05 to 6.79) | 0.68 |

| 7 | 40% (4/10) | 67% (2/3) | 3.00 (0.20 to 45.2) | 0.43 |

| 8 | 14% (29/209) | 33% (1/3) | 3.10 (0.27 to 35.3) | 0.36 |

| 9 | 45% (5/11) | 100% (2/2) | † | 0.46 |

| 10 | 50% (28/56) | 34% (34/44) | 0.52 (0.23 to 1.17) | 0.11 |

| 11 | 38% (6/16) | 34% (30/87) | 0.88 (0.29 to 2.65) | 0.82 |

| 12 | 15% (6/41) | 18% (5/28) | 1.27 (0.35 to 4.64) | 0.72 |

| 13 | 7% (2/30) | 23% (75/320) | 4.29 (1.00 to 18.4) | 0.05 |

| All combined | 24% (115/474) | 28% (157/564) | 1.15 (0.82 to 1.62) | 0.43 |

*OR expressed as odds of polyp detection in Room B relative to odds in Room A.

†Unable to calculate ORs due to 100% PDR in one room. Analysis using Fisher’s exact test.

PDR, polyp detection rate.

Comparisons were made between the two Lister rooms which were identical to the second hospital. The results are summarised in the online supplementary appendix table 1 and demonstrate that overall for all consultants combined there was no significant difference between rooms. Furthermore, comparison was between the Lister rooms (combined) and the Room A. The results are shown in the online supplementary appendix table 2 and highlight that there were no significant differences observed between the Lister room and the Room A, either for consultants separately or combined.

flgastro-2017-100945supp001.docx (87.2KB, docx)

Comparison was made between the Lister rooms and Room B. The results are summarised in table 2. The results for each consultant separately suggested a difference for one only (consultant 4), with polyp detection higher in the Room B. When the results from the consultants combined, there was slight evidence that polyp detection was higher in the Room B than in the Lister rooms, although the results were not quite significant. The odds of polyp detection were a third higher for the Room B than for the Lister room.

Table 2 Polyp detection rate for Lister rooms combined vs room B for service lists.

| Consultant | Lister PDR (n/N) |

Room B PDR (n/N) |

OR* (95% CI) |

P values |

| 1 | 38% (28/73) | 21% (3/14) | 0.44 (0.11 to 1.71) | 0.24 |

| 2 | 26% (38/146) | 33% (5/15) | 1.42 (0.46 to 4.42) | 0.54 |

| 3 | 18% (6/34) | 29% (8/28) | 1.87 (0.56 to 6.22) | 0.31 |

| 4 | 20% (12/61) | 67% (4/6) | 8.17 (1.34 to 50.0) | 0.02 |

| 5 | 17% (1/6) | 67% (4/6) | 10.0 (0.65 to 154) | 0.10 |

| 6 | 28% (71/250) | 38% (3/8) | 1.51 (0.35 to 6.50) | 0.58 |

| 7 | 21% (32/151) | 67% (2/3) | 7.44 (0.65 to 84.6) | 0.11 |

| 8 | 20% (3/15) | 33% (1/3) | 2.00 (0.13 to 30.2) | 0.62 |

| 9 | 31% (43/137) | 100% (2/2) | † | 0.10 |

| 10 | 35% (7/20) | 34% (34/44) | 0.96 (0.32 to 2.92) | 0.94 |

| 11 | 25% (30/119) | 34% (30/87) | 1.56 (0.85 to 2.86) | 0.15 |

| 12 | 29% (31/106) | 18% (5/28) | 0.53 (0.18 to 1.51) | 0.23 |

| 13 | 19% (7/36) | 23% (75/320) | 1.27 (0.53 to 3.01) | 0.59 |

| All combined | 27% (309/1154) | 28% (157/564) | 1.33 (0.99 to 1.79) | 0.06 |

Bold values represent statistically significant events.

*OR expressed as odds of polyp detection in Room B relative to odds in Lister.

†Unable to calculate ORs due to 100% PDR in one room. Analysis using Fisher’s exact test.

PDR, polyp detection rate.

BCSP cases

A second set of analyses compared the difference in polyp detection between endoscopy rooms for the cases from the BCSP. A comparison of Room A and Room B at the first hospital is summarised in table 3. The results suggested significantly better detection in Room B for one of the consultant 3 and also for the consultants combined. The combined results suggested that the odds of detection were almost twice as great in the Room B as the Room A.

Table 3 Polyp detection rate for room A vs room B for BCSP lists.

| Consultant | Room A PDR (n/N) |

Room B PDR (n/N) |

OR* (95% CI) |

P values |

| 1 | 60% (65/109) | 60% (9/15) | 1.02 (0.34 to 3.06) | 0.98 |

| 2 | – | 75% (44/59) | – | – |

| 3 | 52% (15/29) | 75% (62/83) | 2.78 (1.14 to 6.65) | 0.02 |

| All combined | 58% (80/138) | 73% (115/157) | 1.99 (1.22 to 3.24) | 0.006 |

*OR expressed as odds of polyp detection in Room B relative to odds in Room A.

Bold values represent statistically significant events.

PDR, polyp detection rate.

Comparisons were between the two Lister rooms from the second hospital for BCSP lists. The results are summarised in the online supplementary appendix table 3 and highlighted no strong evidence of a difference between rooms. Furthermore, comparison was made between the Lister rooms (combined) and the Room A. The results are shown in table 4 and highlight a trend towards lower polyp detection in Room A when compared with the Lister rooms for consultant 3 and overall. However, neither result quite reached statistical significance. For consultants combined, the odds of detection were around a third lower in the Room A than in the Lister rooms. The final analysis compared the Lister rooms with the Room B. The results are summarised in the online supplementary appendix table 4 and suggested no difference between rooms for any of the consultants or combined.

Table 4.

Polyp detection rate for Lister room combined vs room A for BCSP lists

| Consultant | Lister PDR (n/N) |

Room A PDR (n/N) |

OR* (95% CI) |

P values |

| 1 | 61% (43/70) | 60% (65/109) | 0.93 (0.50 to 1.72) | 0.81 |

| 2 | 70% (63/90) | – | – | – |

| 3 | 75% (21/28) | 52% (15/29) | 0.36 (0.12 to 1.10) | 0.07 |

| All combined | 68% (127/188) | 58% (80/138) | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.04) | 0.08 |

*OR expressed as odds of polyp detection in Room A relative to odds in Lister.

PDR, polyp detection rate.

Discussion

Our data suggest that the distance between the endoscopist and the monitor may have significant effects on PDR which shows greater effect on bowel cancer screening lists. The most noticeable increase in PDR was observed in the room where the monitor was closest to the endoscopist (Room B). This suggests that possibly the closer the distance the monitor is to the endoscopist the higher the PDR. Interestingly, this phenomenon was not noticed across service lists which suggests that the room set-up is less an important factor when a high polyp burden is not expected.

This is the first study to our knowledge to review the effect on distance from the endoscopist to the monitor and may have implications for endoscopy suite design in the future. Both JAG and the world endoscopy organisation have issued guidelines on the construction of an endoscopy unit.21 22 However, there are no current guidelines on how far an endoscopy monitor should be from the endoscopist.

It has been shown that ADR can be affected by multiple factors to include bowel preparation,17 withdrawal time,16 as well as other confounding factors and it is important to optimise as many modifiable factors to ensure the highest quality endoscopy. With the potential serious complications of missed adenomas that could lead to cancer optimising as many factors to achieve the highest ADR rates are essential.

This study suggests that the endoscopy room itself may be a modifiable variable that may alter PDR. It is likely not necessarily a ‘one size fits all’ approach will work. It is likely that endoscopists have better vision at different lengths dependent on their baseline vision, height and use of glasses. This is reflected in the individual breakdown of PDR between consultants which shows variation across different endoscopy set-ups.

The room differences had significant effects on the BCSP lists; possible explanations for this may be that the room distance from the endoscopist to the monitor has its biggest effect when the polyp burdens are expected to be higher. It is also important to highlight, however, that there were only three endoscopists who performed bowel cancer screening which may skew the results. Further limitations of this study are the retrospective nature and the potential for confounding factors which were not adjusted in this study. It is assumed that patient demographics and characteristics were similar across the whole cohort and across all rooms but we were unable to retrieve these data. The other significant weakness is that we are using PDR as a surrogate marker of ADR and were unable to retrieve histology to remark on how many polyps were adenomatous. Furthermore, we were unable to perform regression analysis to tease out important confounding factors that may account for differences highlighted.

Future prospective studies comparing directly different monitors with endoscopic lengths may help find an optimal length that maximises ADR. This may have to take into account endoscopist vision, need for glasses, as well as other factors that may affect an endoscopist near and far vision. Furthermore, with additional baseline factors it may be possible to use regression analysis to determine risk factors for low PDR. Future studies should also include histological assessment to address the ADR as a more accurate assessment of quality of lower gastrointestinal endoscopy.

Conclusions

This study has suggested that the distance from the endoscopist to the monitor can affect PDR which can be a surrogate marker for ADR. It appears that the further the endoscopist from the monitor the lower their PDR, and that this may have the biggest effect with bowel cancer screening lists. It is important to determine the optimum distance from the endoscopist to the endoscopy monitor in order to maximise PDR and standardisation of endoscopy rooms may help achieve better PDR.

Footnotes

Contributors: JPS collected, managed and analysed the data. PM extracted the data. JPS and SMG reviewed the literature and prepared the manuscript. SMG developed the concept and provided critical revisions to the manuscript. CK and PB helped with the statistical analysis and revisions of the manuscript. All authors agreed to the final version of the manuscript. SMG is the guarantor of the article.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Rees CJ, Gibson ST, Rutter MD, et al. UK key performance indicators and quality assurance standards for colonoscopy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, et al. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2533–41. 10.1056/NEJMoa055498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Singh S. Polyp detection rates: a possible surrogate for colonoscopy competency in addition to cecal intubation. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1925 10.1038/ajg.2012.349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Delavari A, Salimzadeh H, Bishehsari F, et al. Mean Polyp per Patient Is an Accurate and Readily Obtainable Surrogate for Adenoma Detection Rate: Results from an Opportunistic Screening Colonoscopy Program. Middle East J Dig Dis 2015;7:214–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Williams JE, Holub JL, Faigel DO. Polypectomy rate is a valid quality measure for colonoscopy: results from a national endoscopy database. Gastrointest Endosc 2012;75:576–82. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Williams JE, Le TD, Faigel DO. Polypectomy rate as a quality measure for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:498–506. 10.1016/j.gie.2010.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Francis DL, Rodriguez-Correa DT, Buchner A, et al. Application of a conversion factor to estimate the adenoma detection rate from the polyp detection rate. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:493–7. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bowel cancer statistics | Cancer Research UK [Internet]. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer (cited 1 Dec 2017).

- 9. Midgley R, Kerr D. Colorectal cancer. Lancet 1999;353:391–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)07127-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardy RG, Meltzer SJ, Jankowski JA. ABC of colorectal cancer. Molecular basis for risk factors. BMJ 2000;321:886–9. 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. O’brien MJ, Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, et al. Flat adenomas in the National Polyp Study: is there increased risk for high-grade dysplasia initially or during surveillance? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;2:905–11. 10.1016/S1542-3565(04)00392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Scholefield JH. ABC of colorectal cancer: screening. BMJ 2000;321:1004–6. 10.1136/bmj.321.7267.1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Terry MB, Neugut AI, Bostick RM, et al. Risk factors for advanced colorectal adenomas: a pooled analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2002;11:622–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Raju GS, Vadyala V, Slack R, et al. Adenoma detection in patients undergoing a comprehensive colonoscopy screening. Cancer Med 2013;2:391–402. 10.1002/cam4.73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Corley DA, Jensen CD, Marks AR. Can we improve adenoma detection rates? A systematic review of intervention studies. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:656–65. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jover R, Zapater P, Polanía E, et al. Modifiable endoscopic factors that influence the adenoma detection rate in colorectal cancer screening colonoscopies. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:381–9. 10.1016/j.gie.2012.09.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lebwohl B, Kastrinos F, Glick M, et al. The impact of suboptimal bowel preparation on adenoma miss rates and the factors associated with early repeat colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:1207–14. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adler A, Aminalai A, Aschenbeck J, et al. Latest generation, wide-angle, high-definition colonoscopes increase adenoma detection rate. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:155–9. 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishaq S, Siau K, Harrison E, et al. Technological advances for improving adenoma detection rates: The changing face of colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:721–7. 10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Munson GW, Harewood GC, Francis DL. Time of day variation in polyp detection rate for colonoscopies performed on a 3-hour shift schedule. Gastrointest Endosc 2011;73:467–75. 10.1016/j.gie.2010.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Advisory Group on Endoscopy JG. Joint Advisory Group on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (JAG) accreditation standards for endoscopy services.

- 22. Mulder CJJ, Jacobs M, Leicester RJ, et al. Guidelines for designing a digestive disease endoscopy unit: Report of the World Endoscopy Organization. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2017-100945supp001.docx (87.2KB, docx)