Abstract

Protein ubiquitination is an important post-translational modification that is associated with multiple diseases, including pituitary adenomas (PAs). Protein ubiquitination profiling in human pituitary and PAs remains unknown. Here, we performed the first ubiquitination analysis with an anti-ubiquitin antibody (specific to K-ε-GG)-based label-free quantitative proteomics method and bioinformatics to investigate protein ubiquitination profiling between PA and control tissues. A total of 158 ubiquitinated sites and 142 ubiquitinated peptides in 108 proteins were identified, and five ubiquitination motifs were found. KEGG pathway network analysis of 108 ubiquitinated proteins identified four statistically significant signaling pathways, including PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, hippo signaling pathway, ribosome, and nucleotide excision repair. R software Gene Ontology (GO) analysis of 108 ubiquitinated proteins revealed that protein ubiquitination was involved in multiple biological processes, cellular components, and molecule functions. The randomly selected ubiquitinated 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein was further analyzed with Western blot, and it was found that upregulated 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein in nonfunctional PAs might be derived from the significantly decreased level of its ubiquitination compared to control pituitaries, which indicated a contribution of 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein to pituitary tumorigenesis. These findings provided the first ubiquitinated proteomic profiling and ubiquitination-involved signaling pathway networks in human PAs. This study offers new scientific evidence and basic data to elucidate the biological functions of ubiquitination in PAs, insights into its novel molecular mechanisms of pituitary tumorigenesis, and discovery of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for effective treatment of PAs.

Keywords: pituitary adenoma, ubiquitination, quantitative proteomics, mass spectrometry, bioinformatics

Introduction

Pituitary adenomas (PAs) are a common type of intracranial tumor (1) that accounts for about 10% of intracranial tumors (2). Clinical manifestations include abnormalities of hormone secretion, pituitary apoplexy, compressing syndromes of tumor that surrounds the pituitary gland, and other anterior pituitary dysfunctions. PAs are divided into functional PAs (FPAs) and nonfunctional PAs (NFPAs) according to their hormone-secreting functions (3). FPAs display hormone hypersecretion. Because an FPA has its secondary symptoms and signs of excessive secretion of tumor hormones, it is easily diagnosed and treated at an earlier stage. NFPAs do not have any hormone hypersecretion and are more difficult to diagnosis (4). An NFPA usually has a larger volume at the time of diagnosis, and is often characterized by hypophysis dysfunction, visual field defect, and headache (5). Although a PA is commonly a benign tumor (6), secondary symptoms are caused by a large number of hormones produced by FPA and compression of surrounding tissues—causing vision loss, headaches, and so on by NFPA (7). Therefore, it is necessary to in-depth understand its molecular mechanisms of PAs and to discover novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for effective treatment of PAs.

Protein ubiquitination is an important post-translational modification (PTM), which plays important roles in maintenance of the balance between protein synthesis and degradation, and in cell signaling, and associates with multiples diseases, including cancers (8, 9). For example, Luo et al. (10) found that TRAF6 regulates melanoma invasion and metastasis through ubiquitination of Basigin. Ubiquitin is a highly conserved small protein that consists of 76 amino acids, and is a heat-stable protein. In structure, ubiquitin is a polypeptide of 8.5 kDa (9, 11, 12). The full length of the ubiquitin molecule contains seven lysine sites (K6, K11, K27, K29, K33, K48, and K63), a methionine site at the N-terminus, and one glycine site at the C-terminus (13, 14). Ubiquitin can be covalently bound to the target protein under catalysis of a series of enzymes. This process is called ubiquitination. Ubiquitination is a process that modulates the PTMs of multiple cells and modifies protein function, stability, and localization (15–19). The ubiquitination process involves the synergy of three enzymes: ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1, ubiquitin-coupled enzyme E2, and ubiquitin ligase E3 (20–22). First, E1 utilizes the energy provided by ATP to form a high-energy thioester bond between the carboxyl group on the lysine C-terminal Lys residue and the thiol group on its own cysteine residue to activate the ubiquitin molecule. The activated ubiquitin is re-bound to the Cys residue of E2 through the thioester bond. Finally, the activated ubiquitin is either directly linked to the protein substrate via E2, or the ubiquitin is transferred to the ubiquitin to form an amino isopeptide bond between the carboxyl terminal of ubiquitin and the amino group of the Lys residue of the target protein under the action of E3 (9, 11). In this series of enzymatic cascades, E3 plays the most-important role in the specific recognition of target proteins and the regulation of ubiquitination system activity (20, 23), because E3 ligase recognizes substrates through specific protein-protein interactions (21). E1, E2, and E3 can form several different ubiquitination substrates. Some substrate proteins are only monoubiquitinated, and some have multiple lysine residues. Under appropriate conditions, multiple sites are monoubiquitinated, and some proteins form polyubiquitin chains at a single lysine site.

NFPAs are more common than FPAs in the population of PA patients. However, it is difficult for NFPA patients to obtain an early accurate diagnosis. The treatment of PA patients is generally surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy; however, it is often difficult to achieve a complete cure. It is necessary to investigate new molecular mechanisms of pituitary tumorigenesis and biomarkers for treatment of PAs. Protein ubiquitination is one of PTMs that contribute to the generation of proteoforms. It is well-known that an important function of protein ubiquitination is in the degradation of proteins to maintain the balance of synthesis and degradation of proteins in human body. Furthermore, studies found that the ubiquitin proteasome system changes in pituitary adenomas (24), and that ubiquitination is involved in pituitary tumorigenesis (25). Our previous study also identified ubiquitin-proteasome, and that its proteasome subunit alpha type 2 was nitrated in pituitary adenomas, which affected the function of the proteasome that is a multicatalytic proteinase complex in the cytoplasmic and nuclear regions and is involved in an intracellular, ATP/ubiquitin-dependent, nonlysosomal proteolytic pathway (26). In addition, in our previous series of studies on PA comparative proteomics, an interesting phenomenon is that the number of down-regulated proteins is much more than the number of up-regulated proteins in PAs (27–30), the mRNA expression of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes E2 and E3 was significantly increased in NFPAs (28), the mRNA expression of ubiquitin specific protease 34 was significantly decreased in PAs (29), ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase isozyme L1 was identified in NFPAs (27), and the protein ubiquitination pathway was changed in NFPAs (30). Therefore, it is hypothesized that ubiquitination plays important roles in this interesting phenomenon to discover the key protein ubquitinations for in-depth insights into molecular mechanisms of NFPAs, and to discover reliable biomarkers and effective therapeutic targets. It is important to investigate protein ubiquitinations in human NFPAs.

Anti-ubiquitin antibody-based label-free quantitative proteomics is an effective method to globally detect, identify, and quantify protein ubiquination in a given condition, such as tumors vs. controls (31–43). Briefly, the total proteins extracted from tumor and control tissues were digested with trypsin, respectively. The ubiquitinated tryptic peptides in the tryptic peptide mixture were isolated and enriched with an anti-ubiquitin antibody specific to a K-ε-GG group. Isolated ubiquitinated peptides were analyzed with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). The MS/MS data were used to search protein database to identify proteins and determine ubiquitinated sites, and the level of protein ubiquitination was determined with MaxQuant algorithms. MaxQuant is the leading qualitative and quantitative algorithm for label-free quantitative proteomics.

Trypsin digestion, anti-ubiquitin antibody-based enrichment, and label-free quantitative proteomics are addressed here. The ubiquitin molecule is made up of 76 amino acids, and the C-terminal glycine is conjugated via its carboxy group to the amino group of a lysine side-chain or to the N-terminus. Trypsin digestion of ubiquitinated proteins cleaves off all but the two C-terminal glycine residues of ubiquitin from the modified protein. These two C-terminal glycine (GG) residues remain linked to the ε-amino group of the modified lysine residue in the tryptic peptide derived from digestion of the substrate protein. The presence of the GG on the side chain of that lysine prevents cleavage by trypsin at that site, to result in an internal modified lysine residue in a formerly ubiquitinated peptide. The K-ε-GG group is recognized and enriched with an antibody specific to K-ε-GG (37). For the ubiquitinated K (Ub-K) residue at the C-terminus, N-terminus, or the middle in a peptide, it mainly results from steric bulk hindrance, which does not affect the MS identification (42). The distinct mass shift (114.04 Da) caused by the GG remnant enables identification and precise localization of ubiquitylation sites based on peptide fragments (41). The identified ubiquitinated peptides were quantified with MaxQuant algorithms (43).

This study used anti-ubiquitin antibody-based label-free quantitative proteomics to identify ubiquitinated proteins and sites, and to quantify the level of ubiquitination. Pathway network analysis was used to investigate any molecular network alteration that protein ubiquitination is involved in. Selected ubiquitinated proteins were further analyzed to reveal the roles of ubiquitinated proteins in PAs. These findings will help to elucidate the molecular mechanisms, and discover biomarkers and therapeutic targets for PAs.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Samples

Eight PA tissues were obtained from the Department of Neurosurgery of Xiangya Hospital, China, as approved by the Xiangya Hospital Medical Ethics Committee of Central South University. Post-mortem control pituitary tissues were obtained from the Memphis Regional Medical Center (n = 5), as approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Internal Review Board. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient or the family of each control pituitary subject (post-mortem tissues) after full explanation of the purpose and nature of all experimental procedures. The detailed information of PA and control pituitary tissue samples are collected in Table 1. Quantitative ubiquitination proteomics was performed between the four mixed NFPA samples and the four mixed control samples. Western blot experiments were performed between the six mixed NFPA samples and the three mixed control samples.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristic of NFPA and control tissue samples.

| Group | Sex | Age | Clinical information | Immunohistochemistry | Experiments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Female | 40 | White, Multiple toxic compounds. Blood: HepB (+), HepC (+), HIV(–). | DNT | Proteomics; Western blot |

| Male | 45 | White, Drowning. Blood alcohol = 3.1 g/L; no other drugs detected. Blood: HepB (+), HepC (+), HIV (–). | DNT | Western blot | |

| Male | 36 | White, Multiple toxic materials. Blood alcohol = 0.5 g/L. Blood: HepB (+), HepC (–), HIV (–). | DNT | Proteomics; Western blot | |

| Female | 34 | Black, Gunshot wound to chest. Blood alcohol = 0.3 g/L; no drugs. Blood: HepB (+), HepC (–), HIV (–). | DNT | Proteomics | |

| Female | White, 15 h gunshot wound to head. No drugs or alcohol. Blood: HepB (–), HepC (–), HIV (–). | DNT | Proteomics | ||

| NFPA | Female | 43 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone thinning, enriched blood supply in tumor, and tumor size: 4 × 3 × 3 cm3 | ACTH (–), hGH (–), PRL (–), FSH (+), LH (–), TSH (–) | Proteomics |

| Male | 53 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone thinning, and tumor size: 3 × 3 × 2.5 cm3 | ACTH (–), hGH (–), PRL (–), FSH (–), LH (–), TSH (–) | Proteomics | |

| Female | 43 | NFPA in sellar region. Adhesion of surrounding tissues, and tumor size: 4.5 × 4 × 6 cm3 | ACTH (–), hGH (–), PRL (–), FSH (+), LH (–), TSH (–) | Proteomics; Western blot | |

| Male | 58 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone destruction, enriched blood supply in tumor, and tumor size: 4.5 × 3 × 3 cm3 | ACTH (–), hGH (–), PRL (–), FSH (–), LH (–), TSH (–) | Proteomics; Western blot | |

| Male | 40 | NFPA in sellar region. Recurrent tumor, old blooding in tumor, and tumor size 2 × 2 × 1.8 cm3. | ACTH(–), hGH(–), PRL(–), FSH(+), LH(–), TSH(–) | Western blot | |

| Male | 59 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone thinning, and enriched blood supply in tumor, and tumor size 2.1 × 1.8 × 2 cm3. | ACTH(–), hGH(–), PRL(–), FSH(+), LH(–), TSH(–) | Western blot | |

| Male | 49 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone thinning, old blooding in tumor, and tumor size 2 × 4 × 3 cm3. | ACTH(–), hGH(–), PRL(–), FSH(–), LH(–), TSH(–) | Western blot | |

| Female | 53 | NFPA in sellar region. Sellar floor bone thinning, enriched blood supply, and tumor size 3 × 3.5 × 2.5 cm3. | ACTH(–), hGH(–), PRL(–), FSH(–), LH(–), TSH(–) | Western blot |

DNT, do not test.

Cleavage and Quantification of Proteins

A volume (1 ml) of urea pyrolysis solution [20 mM 2-hydroxyethyl (HEPES), 9 M urea, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, pH 8.0] was added to each tissue sample (100 mg) for an ice-bath ultrasonic treatment (100 W, 10 s, interval 10 s, 10 times). The solution was centrifuged (18,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C). The supernatant was the protein extraction, and its protein content was determined with a Bradford Protein Quantification Kit (YEASEN, Cat# 20202ES76).

Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Proteins

Four NFPA protein samples (1.5 mg/each sample) were equally mixed as tumor protein sample (6 mg), and four control protein samples (1.5 mg/each sample) were equally mixed as control protein sample (6 mg). Each mixed sample (tumor; control) was equally divided into three parts (2 mg/part) for proteomics experiment. A volume of 1 M dithiothreitol (DTT) was added to each sample part (tumor: n = 3; control: n = 3) to produce a final concentration of 10 mM; the mixture was incubated (37°C for 2.5 h), and cooled to room temperature. A volume of 1 M iodoacetamide was added to the mixture to achieve a final concentration of 50 mM, and the mixture was incubated in the dark for 30 min. Five volumes of water were added to dilute the urea concentration to 1.5 M. Trypsin (2 μg/μL) was added at 1:50 (v:v) and the mixture was digested (37°C for 18 h). The tryptic peptide mixture was desalted and lyophilized with an SPE C18 column (Waters WAT051910).

Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides

Each lyophilized tryptic peptide sample (tumor; control) was reconstituted in 1.4 mL of pre-cooled immunoaffinity purification (IAP) buffer. The pretreated anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads [PTMScan ubiquitin remnant motif (K-ε-GG) kit, Cell Signal Technology] were added. The mixture was incubated (1.5 h at 4°C) and centrifuged (2,000 × g, 30 s, 4°C). The supernatant was discarded (44). The pretreated anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads with peptides were washed three times with 1 mL of pre-cooled IAP buffer, and washed three times with 1 mL of pre-chilled water. After washing the anti-K-ε-GG antibody beads with peptides, 40 μL of 0.15% trifluoroacetate (TFA) was added. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 10 min and centrifuged (30 s at 2,000 × g). The above incubation with 0.15% TFA and centrifugation steps (2,000 × g, 30 s) was performed three times. The supernatant that contained ubiquitinated peptides was desalted with C18 STAGE Tips (45).

LC-MS/MS Analysis of Enriched Ubiquitinated Peptides

The enriched ubiquitinated peptides from PA and control tissues were analyzed with LC-MS/MS. Peptides of each sample were separated with a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system EASY-nLC1000 at nanoliter flow rate. The solution A was 0.1% formic acid and 2% acetonitrile aqueous solution. The solution B was 0.1% formic acid and 84% acetonitrile aqueous solution. The chromatographic column was equilibrated with 100% solution A. The enriched ubiquitinated peptide sample was loaded with an autosampler onto a sample-spindle Thermo Scientific EASY column (2 cm*100 μm 5 μm-C18), and peptides were separated with an analytical column of 75 μm × 250 mm 3 μm-C18 at a flow rate of 250 nL/min. The HPLC liquid-phase gradients were as follows: solution B linear gradient from 0 to 55% during 0–220 min, solution B linear gradient from 55 to 100% during 220–228 min, and solution B maintained at 100% during 228–240 min. The enriched peptide products were separated with capillary HPLC according to the HPLC liquid-phase gradients within 240 min, and analyzed with a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Finnigan). The mass spectrometry (MS) detection was in the positive-ion mode. The scan range of the precursor ion was m/z 350–1800. The most-intense 20 ions in each MS spectrum were selected for higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) fragmentation for MS/MS analysis. The MS resolution was 70,000 at m/z 200, and the resolution of MS/MS was 17,500 at m/z 200. The enriched ubiquitinated peptide products from PAs or controls were analyzed three times with LC-MS/MS.

Label-Free Analysis With MaxQuant

Six LC-MS/MS original files (tumor: n = 3; Control: n = 3) were imported into MaxQuant software (version 1.3.0.5) for database review, protein identification, ubiquitination-site determination, and quantification of ubiquitination level. The protein database was uniprot_human_154578_20160815.fasta (list of 154,578 entries, downloaded on 15 August 2016). The main search parameters were: main search ppm was 6, missed cleavage was 4, MS/MS tolerance ppm was 20, de-isotopic was TRUE, enzyme was trypsin, database was uniprot_human_154578_20160815.fasta, fixed modification was carbamidomethyl (C), variable modification was oxidation (M), acetyl (protein N-term), and GlyGly (K), decoy database pattern was reverse, iBAQ was TRUE, match between analyses was 2 min, peptide false discovery rate (FDR) was 0.01, and protein FDR was 0.01. Thus, the protein was characterized, ubiquitination site was determined with amino acid sequence analysis, and its ubiquitination level was quantified with MaxQuant algorithms.

Statistical and Bioinformatics Analysis

The checksum files obtained by MaxQuant were analyzed with Perseus software (version 1.3.0.4). The DAVID database was used to perform KEGG signaling pathway-enrichment analysis of the ubiquitinated proteins. Gene ontology (GO) was used to annotate proteome with R software, and these ubiquitinated proteins were classified with GO annotation based on three categories: cellular components (CC), biological processes (BP), and molecular functions (MF). Motif-X software (http://motif-x.med.harvard.edu/motif-x.html) was used to analyze the model of ubiquitinated peptide sequences in specific positions of ubiquityl-31-mers (15 amino acid upstream and 15 amino acid downstream at the ubiquitination site) in all protein sequences. The International Protein Index (IPI) human proteome was used as the background database; setting parameters were width = 15, occurrences = 20, significance = 0.005; other parameters were set to default values.

Western Blot Analysis of 14-3-3 Zeta/Delta Protein

Six NFPA protein samples were equally mixed as the tumor protein sample, and three control protein samples were equally mixed as the control protein sample (Table 1); the equal-load amount (tumor: 22 μg; control: 22 μg) of mixed samples were used for Western blot experiment. Based on the enriched signaling pathways, which include the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and the Hippo signaling pathway, protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was the key molecule, and was ubiquitinated in theses pathways; therefore, protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was selected for Western blot (WB) analysis, and detailed experimental steps for protein extraction was described previously (46). The anti-protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta antibody (Cusabio, China) was diluted with Tris-buffered saline tween (TBST) (v1: v2 = 1:1000). The secondary antibody (Signalway Antibody, U.S.A.) was diluted with TBST (v1: v2 = 1:5000). The detailed experimental steps for WB were described previously (47–49). Briefly, proteins from PA and control samples were separated with 10% SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane, incubated with anti-protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta antibody, incubated with secondary antibody, and visualized.

Results

Protein Ubiquitination in Control Pituitaries and Pituitary Adenomas

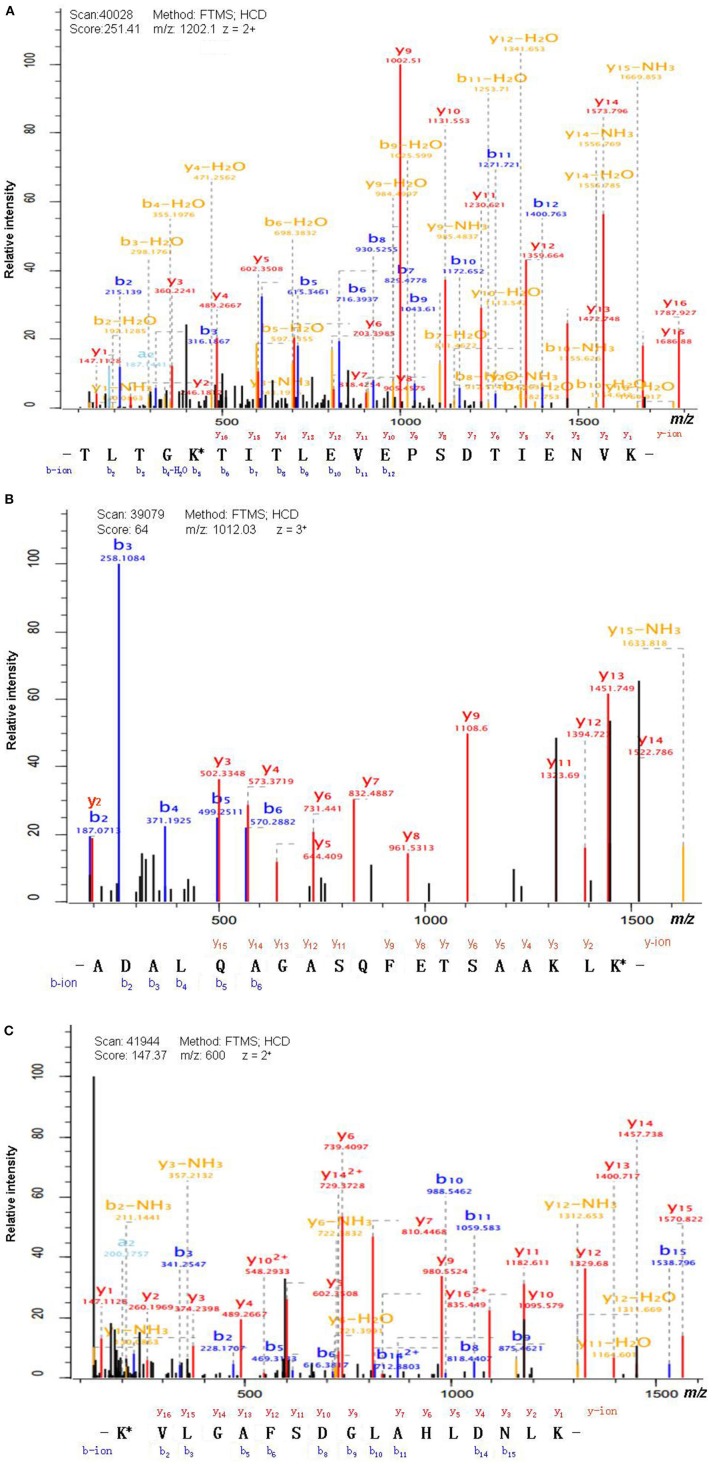

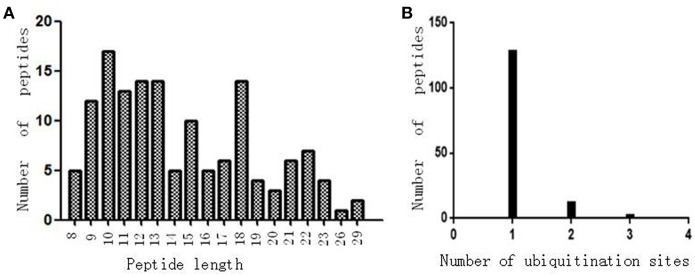

Antibody enrichment-based label-free quantitative proteomics identified 158 ubiquitinated sites and 142 ubiquitinated peptides from 108 proteins in PAs and control pituitaries (Table 2). A representative MS/MS spectrum was from ubiquitinated peptides 7TLTGK*TITLEVEPSDTIENVK27 ([M + 2H]2+, m/z = 1202.14; K* = ubiquitinated lysine residue) of epididymis luminal protein 112 (B2RDW1) or ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a (P62979) (Figure 1A), with a high-quality MS/MS spectrum, excellent signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio, and extensive product-ion b-ion and y-ion series (b2, b3, b4-H2O, b5, b6, b7, b8, b9, b10, b11, and b12; y1, y2, y3, y4, y5, y6, y7, y8, y9, y10, y11, y12, y13, y14, y15, and y16). The ubiquitination site was localized to amino acid residue K, and the ubiquitination level was significantly increased in PAs compared to controls (Table 2). Another representative MS/MS spectrum was from ubiquitinated peptide 67ADALQAGASQFETSAAKLK*85 of uncharacterized protein (L7N2F9) (Figure 1B), which localized the ubiquitination sites at K residue in the peptide C-terminal, with a high-quality MS/MS spectrum, excellent S/N ratio, and extensive product-ion b-ion and y-ion series (b2, b3, b4, b5, and b6; y2, y3, y4, y5, y6, y7, y8, y9, y11, y12, y13, y14, and y15). The ubiquitination site was localized to amino acid residue K, and the protein was ubiquitinated in PAs but not in controls (Table 2). The third representative MS/MS spectrum was from ubiquitinated peptide 67K*VLGAFSDGLAHLDNLK83 of hemoglobin subunit beta (P68871) or beta-globin (D9YZU5) (Figure 1C), which localized the ubiquitination site at K residue in the peptide N-terminal, with a high-quality MS/MS spectrum, excellent S/N ratio, and extensive product-ion b-ion and y-ion series (b2, b3, b5, b6, b8, b9, b10, b11, b14, and b15; y1, y2, y3, y4, y5, y6, y7, y9, y10, y11, y12, y13, y14, y15, and y16). The ubiquitination site was localized to amino acid residue K, and the ubiquitination level was significantly increased in PAs compared to controls (Table 2). With the same method, each ubiquitinated peptide and ubiquitination site was identified with MS/MS data, and quantified. Among the 142 ubiquitinated peptides that were identified, 45 ubiquitinated peptides were quantified in PA and control tissues, including 30 statistically significantly differentially ubiquitinated peptides in PAs compared to controls (p < 0.05). A total of 56 ubiquitinated peptides were quantified in PAs, but not in control pituitaries, and six ubiquitinated peptides were quantified in control pituitaries, but not in PAs. A total of 35 ubiquitinated peptides were identified but not quantified in PAs and controls. Moreover, most ubiquitinated peptides were 8–22 amino acids long (Figure 2A). Among 142 ubiquitinated peptides 90.1% (128/142) peptides contained only one ubiquitinated site, 8.5% peptides contained two ubiquitinated sites, 7.8% peptides contained three ubiquitinated sites, and 1.4% peptides contained over three ubiquitinated sites (Figure 2B).

Table 2.

Ubiquitinated proteins identified in nonfunctional pituitary adenomas relative to controls.

| Accession No. | Gene name | Protein name | Modified peptides | Peptide length | Modified positions | Modified probabilities | Modified level (N) | Modified level (T) | Ratio (T/N) | t-test p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A0A0A6YY96 | IREB2 | Iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 | GFQIAAEK*QK* | 10 | 483;485 | 1; 1 | 3.59E+07 | 1.62E+08 | 4.52 | 4.55E-06 |

| P16104 | H2AFX | Histone H2AX | K*TSATVGPK | 9 | 120 | 1 | 3.50E+07 | 1.43E+09 | 40.96 | 1.39E-05 |

| P48200 | IREB2 | Iron-responsive element-binding protein 2 | GFQIAAEK*QK* | 10 | 483;485 | 1; 1 | 3.46E+07 | 1.63E+08 | 4.71 | 3.31E-05 |

| B2RDW1 | RPS30A | Epididymis luminal protein 112 | TLTGK*TITLEVEPSDTIENVK | 21 | 11 | 1 | 1.70E+08 | 1.26E+09 | 7.40 | 3.64E-05 |

| TLSDYNIQK*ESTLHLVLR | 18 | 63 | 1 | 3.71E+07 | 1.64E+08 | 4.43 | 6.07E-03 | |||

| LIFAGK*QLEDGR | 12 | 48 | 1 | 2.91E+09 | 7.32E+09 | 2.52 | 6.88E-03 | |||

| IQDK*EGIPPDQQR | 13 | 33 | 1 | 2.68E+06 | 3.68E+07 | 13.74 | 9.55E-03 | |||

| TITLEVEPSDTIENVK*AK | 18 | 27 | 0.956 | 1.95E+07 | ||||||

| MQIFVK*TLTGK | 11 | 6 | 0.923 | |||||||

| TITLEVEPSDTIENVKAK* | 18 | 29 | 0.594 | |||||||

| VDENGK*ISR | 9 | 113 | 1 | |||||||

| P62979 | RPS27A | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a | TLTGK*TITLEVEPSDTIENVK | 21 | 11 | 1 | 1.72E+08 | 1.27E+09 | 7.37 | 3.78E-05 |

| TLSDYNIQK*ESTLHLVLR | 18 | 63 | 1 | 3.71E+07 | 1.96E+08 | 5.27 | 6.89E-04 | |||

| P68871 | HBB | Hemoglobin subunit beta | FFESFGDLSTPDAVMGNPK*VK* | 21 | 60;62 | 0.5; 0.5 | 1.69E+06 | 2.01E+07 | 11.87 | 3.71E-04 |

| GTFATLSELHCDK*LHVDPENFR | 22 | 96 | 1 | 1.89E+07 | 9.13E+07 | 4.83 | 1.23E-02 | |||

| K*VLGAFSDGLAHLDNLK | 17 | 67 | 1 | 2.07E+06 | 1.02E+07 | 4.92 | 1.22E-01 | |||

| L7N2F9 | Uncharacterized protein | VNVDK*VLER | 9 | 52 | 1 | 1.04E+07 | 1.23E+08 | 11.86 | 8.99E-04 | |

| ADALQAGASQFETSAAK*LK | 19 | 83 | 0.876 | 2.01E+07 | ||||||

| ADALQAGASQFETSAAKLK* | 19 | 85 | 0.539 | 4.61E+07 | ||||||

| DQK*LSELDDR | 10 | 59 | 1 | 6.10E+06 | 5.24E+07 | 8.60 | 2.47E-03 | |||

| D9YZU5 | HBB | Beta-globin | FFESFGDLSTPDAVMGNPK*VK* | 21 | 60;62 | 0.5; 0.5 | 2.48E+06 | 2.02E+07 | 8.14 | 1.14E-03 |

| K*VLGAFSDGLAHLDNLK | 17 | 67 | 1 | 1.79E+06 | 1.02E+07 | 5.69 | 4.65E-02 | |||

| P62979 | RPS27A | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a | IQDK*EGIPPDQQR | 13 | 33 | 1 | 3.34E+06 | 5.10E+07 | 15.27 | 1.16E-03 |

| LIFAGK*QLEDGR | 12 | 48 | 1 | 2.90E+09 | 7.33E+09 | 2.53 | 6.90E-03 | |||

| F5H5D3 | TUBA1C | Tubulin alpha-1C chain1 | VGINYQPPTVVPGGDLAK*VQR | 21 | 370 | 1 | 2.27E+07 | 3.78E+07 | 1.67 | 1.38E-03 |

| DVNAAIATIK*TK* | 12 | 336;338 | 0.679;0.57 | 2.98E+06 | ||||||

| Q9HCC9 | ZFYVE28 | Lateral signaling target protein 2 | DFCVK*FPEEIR | 11 | 87 | 1 | 7.36E+06 | 2.31E+07 | 3.14 | 1.50E-03 |

| A0A024R017 | HIST1H2AC | Histone H2A | NDEELNK*LLGR | 11 | 96 | 1 | 3.45E+06 | |||

| VTIAQGGVLPNIQAVLLPK*K* | 20 | 119;120 | 0.5; 0.5 | 6.31E+07 | 1.13E+08 | 1.80 | 1.52E-03 | |||

| P69905 | HBA1 | Hemoglobin subunit alpha | AAWGK*VGAHAGEYGAEALER | 20 | 17 | 1 | 7.09E+06 | |||

| TYFPHFDLSHGSAQVK* | 16 | 57 | 1 | 1.94E+06 | 2.06E+08 | 106.34 | 5.10E-03 | |||

| P08670 | VIM | Vimentin | K*LLEGEESR | 9 | 402 | 1 | 1.70E+06 | 5.54E+06 | 3.26 | 5.62E-03 |

| EK*LQEEMLQR | 10 | 188 | 1 | 1.40E+07 | 2.02E+07 | 1.44 | 2.44E-01 | |||

| QVDQLTNDK*AR | 11 | 168 | 1 | 1.99E+06 | 2.97E+06 | 1.49 | 2.74E-01 | |||

| K*LLEGEESR | 9 | 393 | 1 | 5.54E+06 | ||||||

| C8C504 | HBB | Beta-globin | GTFATLSELHCDK*LHVDPENFR | 22 | 96 | 1 | 2.04E+07 | 8.43E+07 | 4.14 | 5.79E-03 |

| Q96T46 | HBA2 | Hemoglobin alpha 2 | TYFPHFDLSHGSAQVK* | 16 | 33 | 1 | 1.94E+06 | 2.03E+08 | 104.44 | 6.08E-03 |

| Q9H582 | ZNF644 | Zinc finger protein 644 | RSFLQQDVNK* | 10 | 11 | 1 | 9.99E+06 | 4.56E+07 | 4.56 | 6.13E-03 |

| Q9H3H9 | TCEAL2 | Transcription elongation factor A protein-like 2 | QYK*EAIHDMNFSNEDMIR | 18 | 154 | 1 | 3.49E+06 | 1.77E+07 | 5.07 | 6.49E-03 |

| E9PL57 | NEDD8-MDP1 | Protein NEDD8-MDP1 | TLTGK*EIEIDIEPTDKVER | 19 | 11 | 1 | 3.50E+06 | 1.20E+07 | 3.43 | 6.76E-03 |

| Q59EJ3 | Heat shock 70kDa protein 1A variant | MVQEAEK*YK | 9 | 592 | 0.891 | 9.34E+05 | 9.36E+06 | 10.02 | 1.11E-02 | |

| D6R956 | UCHL1 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase | CFEK*NEAIQAAHDAVAQEGQCR | 22 | 135 | 1 | 5.86E+06 | |||

| MQLK*PMEINPEMLNK | 15 | 4 | 1 | 2.77E+06 | 8.80E+06 | 3.17 | 1.61E-02 | |||

| P14735 | IDE | Insulin-degrading enzyme | EVNAVDSEHEK*NVMNDAWR | 19 | 192 | 1 | 2.05E+06 | 7.47E+06 | 3.65 | 1.94E-02 |

| Q6ZUF2 | cDNA FLJ43763 fis, clone TESTI2048603 | FFSPPNMSVTHK*EAHERK | 18 | 19 | 0.977 | 1.39E+08 | 2.50E+08 | 1.80 | 5.15E-02 | |

| P61088 | UBE2N | Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 N | ICLDILKDK* | 9 | 94 | 0.962 | 1.74E+07 | 2.27E+07 | 1.30 | 7.06E-02 |

| D1MGQ2 | HBA2 | Alpha-2 globin chain | AAWGK*VGAHAGEYGAEALER | 20 | 17 | 1 | 7.09E+06 | |||

| TYFPHFDLSHGSAQVK* | 16 | 57 | 1 | 2.22E+06 | 1.26E+08 | 56.71 | 1.21E-01 | |||

| P02042 | HBD | Hemoglobin subunit delta | GTFSQLSELHCDK*LHVDPENFR | 22 | 96 | 1 | 1.57E+07 | 2.01E+07 | 1.28 | 1.43E-01 |

| D3DQ48 | TMEM59 | Transmembrane protein 59, isoform CRA_e | TEDHEEAGPLPTK*VNLAHSEI | 21 | 316 | 1 | 3.64E+06 | 1.31E+07 | 3.61 | 1.63E-01 |

| K7EPI4 | GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein | GGK*STK*DGENHK* | 12 | 10;13;19 | 1;1;1 | 2.32E+06 | 2.06E+07 | 8.87 | 2.34E-01 |

| A0A024R5H9 | PLEKHB1 | Pleckstrin homology domain containing, family B (Evectins) member 1, isoform CRA_a | LHLCAETK*DDALAWK | 15 | 113 | 0.999 | 6.23E+06 | 0.00E+00 | 0.00 | 1.39E-01 |

| B7WPA5 | PLEKHB2 | Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family B member 2 | QNIEDK*VHMPMDCINIR | 17 | 46 | 1 | 1.30E+07 | 7.08E+06 | 0.54 | 3.41E-01 |

| Q3BBV0 | NBPF1 | Neuroblastoma breakpoint family member 1 | VGWALDMDEIEK* | 12 | 950 | 1 | 8.76E+06 | 5.34E+06 | 0.61 | 4.18E-01 |

| A4UGR9 | XIRP2 | Xin actin-binding repeat-containing protein 2 | WLFETQPMESLYEK* | 14 | 934 | 1 | 1.82E+07 | 2.61E+07 | 1.44 | 5.39E-01 |

| B7ZMF0 | CEP192 | CEP192 protein | IVSPK*NSDLK | 10 | 556 | 0.908 | 1.14E+07 | 1.96E+07 | 1.71 | 6.03E-01 |

| A0N071 | HBD | Delta globin | GTFSQLSELHCDK*LHVDPENFR | 22 | 96 | 1 | 2.08E+07 | 2.20E+07 | 1.05 | 8.73E-01 |

| A0A024QZP6 | H2AFY2 | Core histone macro-H2A | IHPELLAK*K* | 9 | 116;117 | 0.705; 0.585 | ||||

| A0A024R466 | ITM2C | Integral membrane protein 2C, isoform CRA_a | ISFQPAVAGIK*GDK | 14 | 14 | 0.855 | 1.33E+07 | |||

| A0A024R6B3 | TMEM63C | Transmembrane protein 63C, isoform CRA_a | DIEDPELIIK*HFHEAYPGSVVTR | 23 | 239 | 1 | 3.89E+06 | |||

| A0A024R7G8 | RAD23A | RAD23 homolog A (S. cerevisiae), isoform CRA_a | LIYAGK*ILSDDVPIR | 15 | 53 | 1 | 1.24E+07 | |||

| A0A024RDB0 | UBE1L2 | Ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1-like 2, isoform CRA_a | IDAHLNK*VCPTTETIYNDEFYTK | 23 | 544 | 1 | 4.66E+06 | |||

| A0A087WZE4 | SPTA1 | Spectrin alpha chain, erythrocytic 1 | VNILTDK*SYEDPTNIQGK | 18 | 79 | 1 | 6.34E+06 | |||

| A0A0K0KMI2 | POU5F1 | POU class 5 homeobox 1 transcript variant OCT4B4 | K*LGGQLGR | 8 | 1 | 1 | 7.82E+06 | |||

| A0A0U1RRH7 | Histone H2A | NDEELNK*LLGK | 11 | 96 | 0.996 | |||||

| A0A140VJZ1 | Testicular tissue protein Li 218 | LEK*IFQNAPTDPTQDFSTQVAK | 22 | 360 | 1 | |||||

| A0AVT1 | UBA6 | Ubiquitin-like modifier-activating enzyme 6 | IDAHLNK*VCPTTETIYNDEFYTK | 23 | 544 | 1 | 4.54E+06 | |||

| A4D2P6 | GRID2IP | Delphilin | GK*MGTVSK*SR | 10 | 570;576 | 1; 1 | ||||

| A6NNT2 | C16orf96 | Uncharacterized protein C16orf96 | SALAGK*ASR | 9 | 819 | 1 | ||||

| A6ZKI3 | FAM127A | Protein FAM127A | K*ESPLLNDYR | 10 | 86 | 1 | 1.64E+07 | |||

| A8K6M4 | cDNA FLJ75725, highly similar to Homo sapiens vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs homolog 1B (yeast) (VTI1B), mRNA | ASSAASSEHFEK*LHEIFR | 18 | 13 | 1 | 9.09E+06 | ||||

| B1A4G6 | GH1 | Growth hormone 1 isoform 1 | EETQQK*SNLELLR | 13 | 96 | 1 | 5.87E+06 | |||

| B4DPP6 | cDNA FLJ54371, highly similar to Serum albumin | K*LVAASQAALGL | 12 | 607 | 1 | |||||

| K*QTALVELVK | 10 | 558 | 1 | |||||||

| B4DR52 | Histone H2B | HAVSEGTK*AVTK | 12 | 117 | 1 | 4.70E+07 | ||||

| B4E1J8 | cDNA FLJ56285, highly similar to ADP-ribosylation factor-like protein 8B | DLPNALDEK*QLIEK | 14 | 193 | 1 | |||||

| B9EGU6 | RC3H1 | Ring finger and CCCH-type zinc finger domains 1 | KEIMAQLEERK* | 11 | 769 | 0.999 | 7.15E+06 | |||

| C9JLQ8 | AEBP1 | Adipocyte enhancer-binding protein 1 | MPPEKTK*DK* | 9 | 7;9 | 0.985;1 | ||||

| E7EX29 | YWHAZ | 14-3-3 protein zeta/delta | MDKNELVQKAK* | 11 | 11 | 0.537 | 2.35E+06 | |||

| K7EPF9 | APOC1 | Apolipoprotein C-I | EFGNTLEDK*AR | 11 | 47 | 1 | 7.55E+06 | |||

| M1VKI3 | SDC4-ROS1_S4;R32 | Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor | AGSGSQVPTEPKK* | 13 | 105 | 0.554 | 1.53E+07 | |||

| P01241 | GH1 | Somatotropin | EETQQK*SNLELLR | 13 | 96 | 1 | 4.23E+06 | |||

| P02671 | FGA | Fibrinogen alpha chain | EK*VTSGSTTTTR | 12 | 448 | 1 | 4.06E+06 | |||

| TVIGPDGHK*EVTK | 13 | 476 | 0.86 | |||||||

| P02768 | ALB | Serum albumin | K*LVAASQAALGL | 12 | 598 | 1 | ||||

| K*QTALVELVK | 10 | 549 | 1 | |||||||

| P04908 | HIST1H2AB | Histone H2A type 1-B/E | NDEELNK*LLGR | 11 | 96 | 1 | 3.45E+06 | |||

| P09960 | LTA4H | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase | FSYK*SITTDDWK | 12 | 418 | 1 | 4.10E+06 | |||

| P19021 | PAM | Peptidyl-glycine alpha-amidating monooxygenase | AFGDSEHK*LETSSGR | 15 | 901 | 1 | ||||

| P23396 | RPS3 | 40S ribosomal protein S3 | KPLPDHVSIVEPK*DEILPTTPISEQK | 26 | 214 | 1 | 2.84E+07 | |||

| P31946 | YWHAB | 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha | SELVQKAK* | 8 | 13 | 0.672 | ||||

| P35212 | GJA4 | Gap junction alpha-4 protein | ALPAK*DPQVER | 11 | 119 | 1 | 2.26E+06 | |||

| P35251 | RFC1 | Replication factor C | KLVSETVK* | 8 | 22 | 1 | ||||

| P45974 | USP5 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase 5 | LEK*IFQNAPTDPTQDFSTQVAK | 22 | 360 | 1 | 9.83E+06 | |||

| P54725 | RAD23A | UV excision repair protein RAD23 homolog A | LIYAGK*ILSDDVPIR | 15 | 53 | 1 | 1.39E+07 | |||

| LIYAGK*ILNDDTALK | 15 | 51 | 0.993 | |||||||

| P54727 | RAD23B | UV excision repair protein RAD23 homolog B | LIYAGK*ILNDDTALK | 15 | 51 | 0.993 | ||||

| P55072 | VCP | Transitional endoplasmic reticulum ATPase | ASGADSK*GDDLSTAILK | 17 | 8 | 1 | 7.91E+06 | |||

| P60709 | ACTB | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | DSYVGDEAQSK*R | 12 | 61 | 1 | 2.05E+06 | |||

| P60866 | RPS20 | 40S ribosomal protein S20 | DTGK*TPVEPEVAIHR | 15 | 8 | 1 | 9.48E+06 | |||

| P61981 | YWHAG | 14-3-3 protein gamma | EQLVQK*AR | 8 | 10 | 1 | ||||

| P62979 | RPS27A | Ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a | TITLEVEPSDTIENVK*AK | 18 | 27 | 0.956 | 1.72E+07 | |||

| MQIFVK*TLTGK | 11 | 6 | 0.923 | |||||||

| TITLEVEPSDTIENVKAK* | 18 | 29 | 0.594 | |||||||

| VDENGK*ISR | 9 | 113 | 1 | |||||||

| P83916 | CBX1 | Chromobox protein homolog 1 | KEESEK*PR | 8 | 109 | 1 | ||||

| Q0VDD8 | DNAH14 | Dynein heavy chain 14, axonemal | SLLSNVSQWDTFK* | 13 | 2919 | 1 | ||||

| Q13753 | LAMC2 | Laminin subunit gamma-2 | ITSTFHQDVDGWK* | 13 | 219 | 1 | 1.99E+07 | |||

| Q15149 | PLEC | Plectin | SELELTLGK*LEQVR | 14 | 1210 | 1 | 2.72E+06 | |||

| Q4LE39 | ARID4B | AT-rich interactive domain-containing protein 4B | K*ENIK*PSLGSK* | 11 | 462;466;472 | 1;1;1 | 2.05E+07 | |||

| Q59EQ3 | Nudix-type motif 6 isoform a variant | LDAAAFQK*GLQGK* | 13 | 84;89 | 1;1 | 5.22E+06 | ||||

| Q5I0G2 | PRL | Growth hormone A1 | AVEIEEQTK*R | 10 | 153 | 1 | 5.21E+06 | |||

| Q5JWF2 | GNAS | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(s) subunit alpha isoforms XLas | IDVIK*QADYVPSDQDLLR | 18 | 829 | 1 | ||||

| Q5VXU3 | CHIC1 | Cysteine-rich hydrophobic domain-containing protein 1 | SIQK*LIEWENNR | 12 | 176 | 1 | ||||

| Q92625 | ANKS1A | Ankyrin repeat and SAM domain-containing protein 1A | GK*EQELLEAAR | 11 | 3 | 1 | 8.07E+06 | |||

| Q93045 | STMN2 | Stathmin-2 | DLSLEEIQKK* | 10 | 87 | 0.569 | 2.05E+06 | |||

| DLSLEEIQK*K | 10 | 86 | 0.5 | |||||||

| Q93100 | PHKB | Phosphorylase b kinase regulatory subunit beta | AYLQLGINEK* | 10 | 546 | 1 | 2.91E+07 | |||

| Q96AP7 | ESAM | Endothelial cell-selective adhesion molecule | ALEEPANDIK*EDAIAPR | 17 | 286 | 1 | ||||

| Q96EI5 | TCEAL4 | Transcription elongation factor A protein-like 4 | EYK*EAIHDMNFSNEDMIR | 18 | 142 | 1 | 8.59E+06 | |||

| Q96N64 | PWWP2A | PWWP domain-containing protein 2A | TGLEK*MRSGK* | 10 | 496;501 | 1; 1 | 1.06E+07 | |||

| Q9BT67 | NDFIP1 | NEDD4 family-interacting protein 1 | TK*AEATIPLVPGR | 13 | 83 | 1 | ||||

| Q9BUL8 | PDCD10 | Programmed cell death protein 10 | QILSK*IPDEINDR | 13 | 116 | 1 | 2.54E+07 | |||

| Q9BWQ8 | FAIM2 | Protein lifeguard 2 | APGTEGQQQVHGEK*K | 15 | 25 | 0.822 | 2.50E+06 | |||

| Q9H3Z4 | DNAJC5 | DnaJ homolog subfamily C member 5 | FK*EINNAHAILTDATK | 16 | 58 | 1 | 4.81E+06 | |||

| Q9H598 | SLC32A1 | Vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter | DQVGGGGEFGGHDK*PK | 16 | 113 | 0.832 | 9.03E+06 | |||

| Q9NQX7 | ITM2C | Integral membrane protein 2C | ISFQPAVAGIK*GDK | 14 | 14 | 0.855 | 1.33E+07 | |||

| Q9NV96 | TMEM30A | Cell cycle control protein 50A | DEVDGGPPCAPGGTAK*TR | 18 | 24 | 1 | 3.72E+06 | |||

| Q9NX12 | cDNA FLJ20496 fis, clone KAT08729 | SGEEALIIPPDAVAVDCK*DPDDVVPVGQR | 29 | 39 | 1 | 6.69E+06 | ||||

| VTFNSALAQK*EAK | 13 | 13 | 0.733 | |||||||

| Q9P0M6 | H2AFY2 | Core histone macro-H2A.2 | IHPELLAK*K* | 9 | 116;117 | 0.705; 0.585 | ||||

| Q9P1W3 | TMEM63C | Calcium permeable stress-gated cation channel 1 | DIEDPELIIK*HFHEAYPGSVVTR | 23 | 239 | 1 | 5.57E+06 | |||

| Q9UBB4 | ATXN10 | Ataxin-10 | ITSDEPLTK*DDIPVFLR | 17 | 262 | 1 | 1.14E+07 | |||

| Q9UEU0 | VTI1B | Vesicle transport through interaction with t-SNAREs homolog 1B | ASSAASSEHFEK*LHEIFR | 18 | 13 | 1 | 9.35E+06 | |||

| Q9UF11 | PLEKHB1 | Pleckstrin homology domain-containing family B member 1 | LHLCAETK*DDALAWK | 15 | 113 | 0.999 | 6.23E+06 | |||

| Q9UKJ5 | CHIC2 | Cysteine-rich hydrophobic domain-containing protein 2 | SIEK*LLEWENNR | 12 | 117 | 1 | 4.92E+06 | |||

| Q9UQB3 | CTNND2 | Catenin delta-2 | SPSIDSIQK*DPR | 12 | 540 | 1 | 3.06E+06 | |||

| Q9Y287 | ITM2B | Integral membrane protein 2B | SGEEALIIPPDAVAVDCK*DPDDVVPVGQR | 29 | 39 | 1 | 6.69E+06 | |||

| VTFNSALAQK*EAK | 13 | 13 | 0.733 | |||||||

| S4R435 | RPS10-NUDT3 | Protein RPS10-NUDT3 | SAVPPGADKK* | 10 | 139 | 0.574 | 5.99E+07 | |||

| SAVPPGADK*K | 10 | 138 | 0.846 | 6.91E+07 | ||||||

| U6FSN9 | Mprip-Ntrk1 fusion gene | Tyrosine-protein kinase receptor | GWLTK*QYEDGQWK | 13 | 396 | 1 |

Ratio (T/N), Ration of tumors (B) to controls(A). K*, Ubiquitinated lysine residue.

Figure 1.

MS/MS spectrum of the tryptic peptide. (A) The tryptic peptide TLTGK*TITLEVEPSDTIENVK from epididymis luminal protein 112 (B2RDW1) or ubiquitin-40S ribosomal protein S27a (P62979). (B) The tryptic peptide ADALQAGASQFETSAAKLK* from uncharacterized protein (L7N2F9). (C) The tryptic peptide K*VLGAFSDGLAHLDNLK from hemoglobin subunit beta (P68871) or beta-globin (D9YZU5). The observed b- and y-ions were labeled in each MS/MS spectrum. K* = ubiquitinated lysine residue.

Figure 2.

The ubiquitination profile in normal pituitaries and pituitary tumors. (A) Peptide length distribution of all ubiquitinated peptides. (B) Distribution of ubiquitinated peptides based on number of ubiquitination sites.

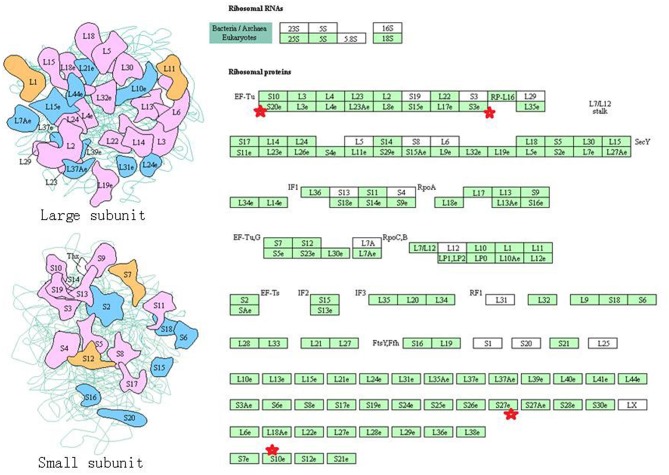

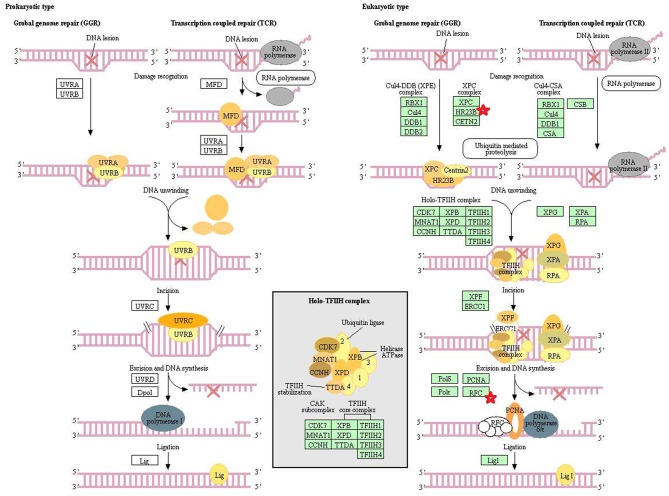

Signaling Pathways Involved in Ubiquitinated Proteins

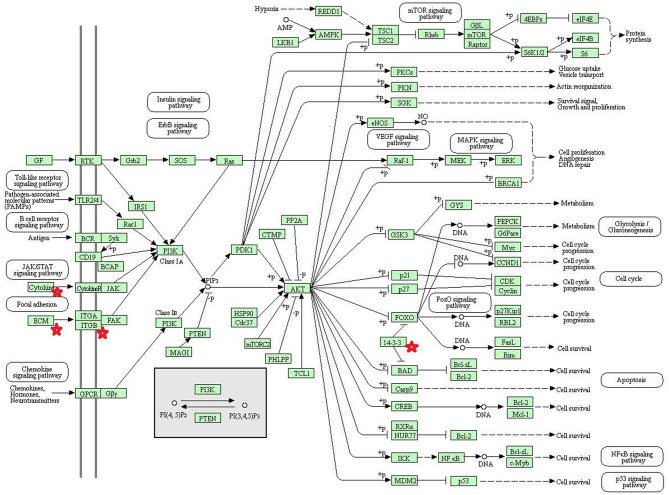

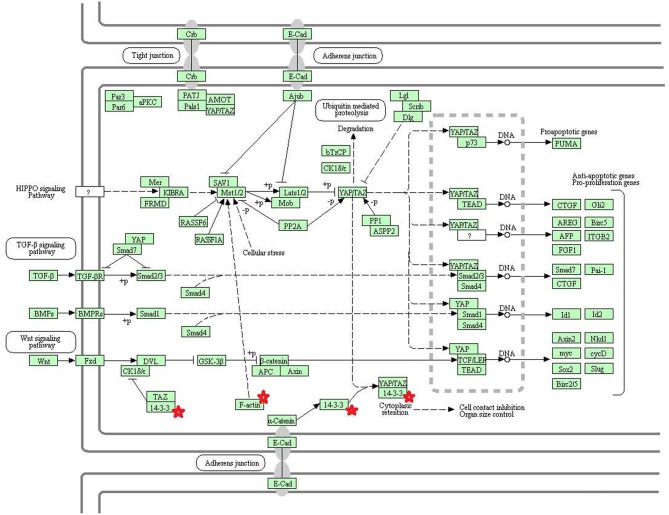

Eight statistically significant KEGG signaling pathways (p < 0.05) were identified with DAVID KEGG pathway-enrichment analysis from 108 ubiquitinated proteins, including PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, Hippo signaling pathway, ribosome, nucleotide excision repair, alcoholism, systemic lupus erythematosus, African trypanosomiasis, and malaria. Among them, PI3K-AKT signaling pathway (Figure 3) is activated by many types of cellular stimulation and toxic damage, and regulates essential cellular functions such as transcription, translation, proliferation, survival, and growth. Hippo signaling pathway (Figure 4) is an evolutionarily conserved signaling pathway that controls the size of organs from flies to humans. For human and mouse, Hippo signaling pathway consists of MST1 and MST2 kinases, their cofactors Salvador, LATS1, and LATS2. In response to high cell density, activated LATS1/2 phosphorylates the transcriptional coactivators YAP and TAZ to promote their cytoplasmic localization, leads to apoptosis, and limits organ-size overgrowth. When the Hippo signaling pathway is inactivated at low cell densities, YAP/TAZ translocate into the nucleus to bind to the transcriptional factor enhancer (TEAD/TEF) family to promote cell growth and proliferation. YAP/TAZ also interact with other transcriptional factors or signaling molecules to allow Hippo pathway-mediated processes interact with other key signaling cascade processes, such as TGF-β and Wnt signaling pathways. Because the function of ribosomes is to translate the genetic code (nucleotide sequence) on the mRNA into the amino acid sequence on the polypeptide chain, the ribosome is closely related to protein synthesis. Ribosome signaling pathway (Figure 5) was enriched, and indicated that certain ubiquitinated proteins are closely related to this signaling pathway to thus affect protein synthesis. Nucleotide Excision repair (NER) (Figure 6) is a mechanism to recognize and repair large amounts of DNA damage caused by compounds, environmental carcinogens, and ultraviolet radiation. Protein ubiquitination might be involved in the nucleotide excision repair process to affect protein synthesis and the corresponding biological functions in PAs. Therefore, protein ubiquitination participated in multiple signaling pathway systems and biological processes in human PAs.

Figure 3.

The PI3K-AKT signaling pathway which was achieved by DAVID pathway analysis. The ubiquitinated proteins are shown by red stars.

Figure 4.

The Hippo signaling pathway which was achieved by DAVID pathway analysis. The ubiquitinated subunits are shown by red stars.

Figure 5.

The ribosome signaling pathway which was achieved by DAVID pathway analysis. The ubiquitinated subunits are shown by red stars.

Figure 6.

The nucleotide excision repair which was achieved by DAVID pathway analysis. The ubiquitinated subunits are shown by red stars.

Functional Characteristics of Ubiquitinated Proteins

In order to further understand the biological function of the ubiquitinated proteins in the development of PAs, GO enrichment analysis of identified ubiquitinated proteins revealed multiple CCs, BPs, and MFs. For CC analysis (Table 3), 33 ubiquitinated proteins were assigned to different CCs. A large number of ubiquitinated proteins were located on ribosome and vesicle. It is well-known that ribosomes are complexes composed of rRNA and proteins, and are important sites for protein synthesis. In addition, vesicles and ribosomal subunits also play an important role in protein synthesis. Ubiquitinated proteins can be degraded by the proteasome pathway (8). When the protein on ribosome or vesicle is usually ubiquitinated, the protein might degrade and affect the synthesis and secretion of other proteins, affect the normal physiological function of the body, and lead to PAs. For BP analysis (Table 4), most ubiquitinated proteins were associated with some important biological processes such as cellular responses to certain substances, self-regulation of cells, DNA repair, etc. Abnormal DNA repair was involved in the occurrence and development of tumors (50). When the proteins involved in DNA repair were ubiquitinated, abnormal DNA repair might occur and lead to PAs. In PA patients, the primary treatment was surgery; however, prolactinomas were usually treated with dopamine agonists (51, 52). The ubiquitinated proteins were associated with drug transport, which might make it difficult for drugs in PA patients to get to the target and thus allow development of tumors. For MF analysis (Table 5), 31 ubiquitinated proteins were significantly enriched in different MFs. The molecular functions of enriched ubiquitinated proteins were mainly combined with other substances, such as oxygen, organic acids, cofactors, etc. An important tumor marker was the infinite proliferation of tumor cells and angiogenesis (53). The proliferation of cells and the production of new blood vessels were inseparable from oxygen and nutrients. Ubiquitinated proteins could bind to oxygen, which might affect the transport of oxygen and nutrients, to thus affect the occurrence and development of PAs.

Table 3.

Statistically significant GO cellular components (CC) derived from ubiquitinated proteins in human pituitary adenomas.

| ID | Cellular components | GeneRatio | BgRatio | P-value | P.adjust | Q-value | GeneID | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0022627 | Cytosolic small ribosomal subunit | 4/33 | 45/19659 | 9.34E-07 | 1.33E-04 | 8.26E-05 | RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0015935 | Small ribosomal subunit | 4/33 | 73/19659 | 6.60E-06 | 4.68E-04 | 2.92E-04 | RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0022626 | Cytosolic ribosome | 4/33 | 115/19659 | 3.99E-05 | 1.89E-03 | 1.18E-03 | RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0044445 | Cytosolic part | 5/33 | 250/19659 | 5.67E-05 | 2.01E-03 | 1.25E-03 | IDE/RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 5 |

| GO:0072562 | Blood microparticle | 4/33 | 147/19659 | 1.04E-04 | 2.95E-03 | 1.83E-03 | FGA/ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0031838 | Haptoglobin-hemoglobin complex | 2/33 | 11/19659 | 1.49E-04 | 3.17E-03 | 1.97E-03 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0005833 | Hemoglobin complex | 2/33 | 12/19659 | 1.78E-04 | 3.17E-03 | 1.97E-03 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0060198 | Clathrin-sculpted vesicle | 2/33 | 12/19659 | 1.78E-04 | 3.17E-03 | 1.97E-03 | DNAJC5/SLC32A1 | 2 |

| GO:0044391 | Ribosomal subunit | 4/33 | 191/19659 | 2.83E-04 | 4.47E-03 | 2.78E-03 | RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0071682 | Endocytic vesicle lumen | 2/33 | 19/19659 | 4.59E-04 | 6.52E-03 | 4.06E-03 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0005840 | Ribosome | 4/33 | 276/19659 | 1.13E-03 | 1.46E-02 | 9.07E-03 | RPS3/RPS20/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0060205 | Cytoplasmic vesicle lumen | 4/33 | 338/19659 | 2.37E-03 | 2.62E-02 | 1.63E-02 | FGA/ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0031983 | Vesicle lumen | 4/33 | 339/19659 | 2.40E-03 | 2.62E-02 | 1.63E-02 | FGA/ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0098563 | Intrinsic component of synaptic vesicle membrane | 2/33 | 46/19659 | 2.70E-03 | 2.74E-02 | 1.71E-02 | DNAJC5/SLC32A1 | 2 |

| GO:0035577 | Azurophil granule membrane | 2/33 | 58/19659 | 4.26E-03 | 4.03E-02 | 2.51E-02 | DNAJC5/TMEM30A | 2 |

| GO:0030658 | Transport vesicle membrane | 3/33 | 204/19659 | 4.78E-03 | 4.24E-02 | 2.64E-02 | DNAJC5/SLC32A1/TMEM30A | 3 |

| GO:0031093 | Platelet alpha granule lumen | 2/33 | 67/19659 | 5.64E-03 | 4.71E-02 | 2.94E-02 | FGA/ALB | 2 |

| GO:0031300 | Intrinsic component of organelle membrane | 3/33 | 226/19659 | 6.34E-03 | 4.98E-02 | 3.10E-02 | DNAJC5/SLC32A1/ITM2B | 3 |

| GO:0005844 | Polysome | 2/33 | 73/19659 | 6.67E-03 | 4.98E-02 | 3.10E-02 | VIM/RPS3 | 2 |

GeneRatio = The ratio of the number of genes enriched by the CC to the total number of genes enriched. BgRatio = The ratio of the number of genes contained in the CC to the number of genes in the BP database.

Table 4.

Statistically significant GO biological processes (BP) derived from ubiquitinated proteins in human pituitary adenomas.

| ID | Biological process | GeneRatio | BgRatio | P-value | P.adjust | Q-value | GeneID | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0097237 | Cellular response to toxic substance | 5/30 | 235/18493 | 3.49E-05 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | ALB/RPS3/HBA1/HBA2/PDCD10 | 5 |

| GO:0042542 | Response to hydrogen peroxide | 4/30 | 141/18493 | 7.61E-05 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | RPS3/HBA1/HBA2/PDCD10 | 4 |

| GO:0045739 | Positive regulation of DNA repair | 3/30 | 61/18493 | 1.30E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | H2AFX/RPS3/UBE2N | 3 |

| GO:0042983 | Amyloid precursor protein biosynthetic process | 2/30 | 11/18493 | 1.39E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | ITM2C/ITM2B | 2 |

| GO:0042984 | Regulation of amyloid precursor protein biosynthetic process | 2/30 | 11/18493 | 1.39E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | ITM2C/ITM2B | 2 |

| GO:0046677 | Response to antibiotic | 5/30 | 323/18493 | 1.57E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | RPS3/HBA1/PRL/HBA2/PDCD10 | 5 |

| GO:0010561 | Negative regulation of glycoprotein biosynthetic process | 2/30 | 12/18493 | 1.66E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | ITM2C/ITM2B | 2 |

| GO:0031581 | Hemidesmosome assembly | 2/30 | 12/18493 | 1.66E-04 | 1.66E-02 | 1.27E-02 | LAMC2/PLEC | 2 |

| GO:0015671 | Oxygen transport | 2/30 | 15/18493 | 2.64E-04 | 2.11E-02 | 1.62E-02 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:1903019 | Negative regulation of glycoprotein metabolic process | 2/30 | 15/18493 | 2.64E-04 | 2.11E-02 | 1.62E-02 | ITM2C/ITM2B | 2 |

| GO:0015893 | Drug transport | 4/30 | 217/18493 | 3.98E-04 | 2.56E-02 | 1.96E-02 | HBA1/HBA2/SLC32A1/TMEM30A | 4 |

| GO:0015669 | Gas transport | 2/30 | 19/18493 | 4.28E-04 | 2.56E-02 | 1.96E-02 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:2001022 | Positive regulation of response to DNA damage stimulus | 3/30 | 92/18493 | 4.39E-04 | 2.56E-02 | 1.96E-02 | H2AFX/RPS3/UBE2N | 3 |

| GO:0000302 | Response to reactive oxygen species | 4/30 | 224/18493 | 4.48E-04 | 2.56E-02 | 1.96E-02 | RPS3/HBA1/HBA2/PDCD10 | 4 |

| GO:0098869 | Cellular oxidant detoxification | 3/30 | 101/18493 | 5.77E-04 | 3.08E-02 | 2.36E-02 | ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

| GO:1990748 | Cellular detoxification | 3/30 | 105/18493 | 6.46E-04 | 3.23E-02 | 2.47E-02 | ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

| GO:0006282 | Regulation of DNA repair | 3/30 | 115/18493 | 8.41E-04 | 3.96E-02 | 3.03E-02 | H2AFX/RPS3/UBE2N | 3 |

| GO:0031112 | Positive regulation of microtubule polymerization or depolymerization | 2/30 | 29/18493 | 1.01E-03 | 4.30E-02 | 3.30E-02 | RPS3/STMN2 | 2 |

| GO:0098754 | Detoxification | 3/30 | 123/18493 | 1.02E-03 | 4.30E-02 | 3.30E-02 | ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

| GO:0042744 | Hydrogen peroxide catabolic process | 2/30 | 32/18493 | 1.22E-03 | 4.77E-02 | 3.66E-02 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0051291 | Protein heterooligomerization | 3/30 | 132/18493 | 1.25E-03 | 4.77E-02 | 3.66E-02 | IDE/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

GeneRatio = The ratio of the number of genes enriched by the BP to the total number of genes enriched. BgRatio = The ratio of the number of genes contained in the BP to the number of genes in the BP database.

Table 5.

Statistically significant GO molecular functions (MF) derived from ubiquitinated proteins in human pituitary adenomas.

| ID | Molecular functions | GeneRatio | BgRatio | P-value | P.adjust | Q-value | GeneID | Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0019825 | Oxygen binding | 3/31 | 36/17632 | 3.38E-05 | 4.97E-03 | 3.48E-03 | ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

| GO:0031720 | Haptoglobin binding | 2/31 | 10/17632 | 1.33E-04 | 8.10E-03 | 5.68E-03 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0001540 | Amyloid-beta binding | 3/31 | 61/17632 | 1.65E-04 | 8.10E-03 | 5.68E-03 | IDE/ITM2C/ITM2B | 3 |

| GO:0005344 | Oxygen carrier activity | 2/31 | 14/17632 | 2.69E-04 | 9.87E-03 | 6.93E-03 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

| GO:0043177 | Organic acid binding | 4/31 | 204/17632 | 4.29E-04 | 1.12E-02 | 7.84E-03 | ALB/PAM/HBA1/HBA2 | 4 |

| GO:0016209 | Antioxidant activity | 3/31 | 86/17632 | 4.56E-04 | 1.12E-02 | 7.84E-03 | ALB/HBA1/HBA2 | 3 |

| GO:0050699 | WW domain binding | 2/31 | 31/17632 | 1.35E-03 | 2.83E-02 | 1.99E-02 | NDFIP1/TCEAL2 | 2 |

| GO:0048037 | Cofactor binding | 5/31 | 495/17632 | 1.59E-03 | 2.92E-02 | 2.05E-02 | ALB/PAM/RPS3/HBA1/HBA2 | 5 |

| GO:0140104 | Molecular carrier activity | 2/31 | 43/17632 | 2.58E-03 | 4.22E-02 | 2.96E-02 | HBA1/HBA2 | 2 |

GeneRatio = The ratio of the number of genes enriched by the MF to the total number of genes enriched. BgRatio = The ratio of the number of genes contained in the MF to the number of genes in the BP database.

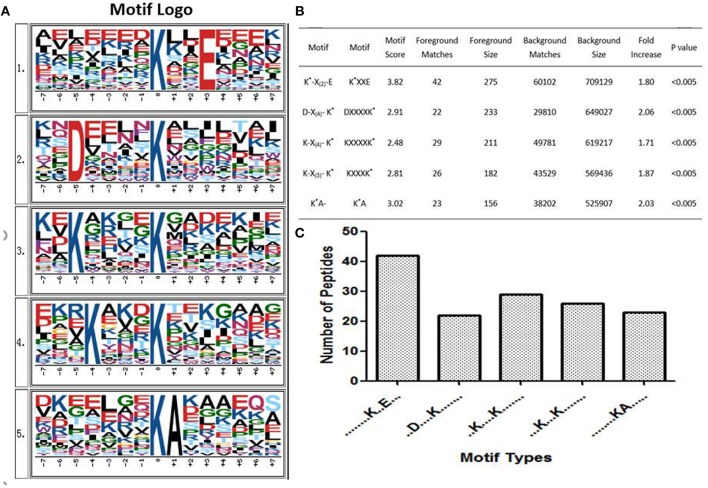

Characterization of Ubiquitinated Peptides

Some studies showed that conservative ubiquitination motifs might not exist in humans (34, 40, 54). To elucidate regulation of ubiquitination in human PAs, ubiquitination motif analysis was carried out by examining the sequences from −15 to +15 amino acid residues in the ubiquitination sites of the 142 ubiquitinated peptides with Motif-X software. Five significantly distinguished motifs were identified (Figures 7A,B), including K*-X(2)-E, D-X(4)-K*, K-X(4)-K*, K-X(3)-K*, and K*A, which refers to 42, 22, 29, 26, and 23 unique ubiquitinated peptides, respectively (K* = the ubiquitinated lysine residue; X = any amino acid residue). Those ubiquitinated peptides had different abundances, which together accounted for 99.3% of the identified ubiquitinated peptides (Figure 7C). Although Zhang et al. studied the ubiquitination modification of wheat (55), the ubiquitination motifs of wheat are completely different from the human ubiquitination motif. This result might reveal differences in ubiquitination motifs among different species. The ubiquitination motifs of human proteins obtained in this study might provide ubiquitin-binding loci for future research. However, one must realize that because this study incorporated a small number of ubiquitinated peptides, the characterized human protein ubiquitination motifs still need to be validated from a large number of ubiquitinated peptide sequences.

Figure 7.

Ubiquitinated protein motifs in human. (A) Ubiquitination motifs and the conservation of ubiquitination sites. The central K stands for the ubiquitinated protein. The size of each letter is related to the frequency of amino acid residues occurring at that position. (B) Taking the ubiquitinated peptide sequence as a foreground, the sequence window of the ubiquitinated related protein non-ubiquitinated lysine was used as a background control. (C) The number of identified ubiquitinated peptides in each motif. K* = ubiquitinated lysine residue. X = any amino acid residue.

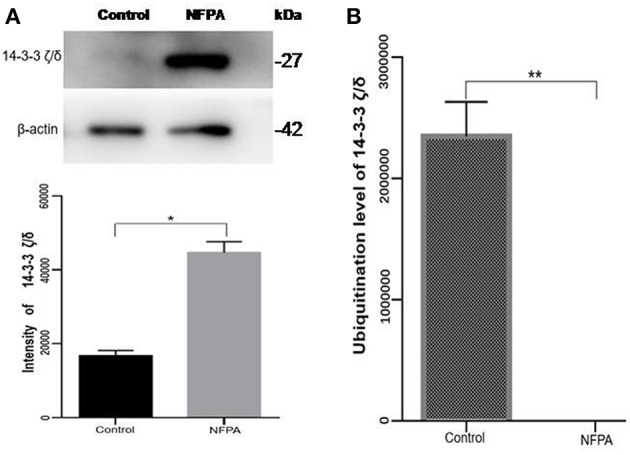

Further Analysis of Ubiquitinated Proteins in Pituitary Adenomas

After comprehensive analysis of ubiquitination data, KEGG pathways, and GO enrichment data, eight statistically significant KEGG signaling pathways (p < 0.05) were identified. Only four of these enriched signaling pathways were associated with tumors, and the protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was an important molecule in the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway and the Hippo signaling pathway. Also, the peptide from protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta underwent ubiquitination in control pituitary tissues, but not in NFPA tissues (Table 2). Therefore, the ubiquitinated protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was chosen for further analysis with Western immunoaffinity blot. The result showed that protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was significantly upregulated in NFPAs compared to controls. Quantitative ubiquitinated proteomics showed that the peptide from protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta was ubiquitinated in controls but not in NFPAs (Figure 8; Table 2). The decreased ubiquitination level of protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta in NFPAs might inhibit degradation of this protein and change the signaling transduction of this protein in PAs.

Figure 8.

The protein expression level and its ubiquitinated level of protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta in NFPAs compared to controls. (A) Western blot analysis of the protein expression level of protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta in NFPAs compared to controls. (B) The ubiquitination level of protein 14-3-3 zeta/delta in NFPAs compared to controls. *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. NFPA, nonfunctional pituitary adenomas; Control, control pituitaries.

Discussion

The Functions of Protein Ubiquitination

Ubiquitination in a protein is under a wide range of functions, and regulates a variety of basic cellular processes, including gene transcription, DNA repair and replication, protein degradation, viral particle sprouting, and intracellular trafficking (56). Monoubiquitination is involved in the regulation of lysosome targeting, endocytosis, and chromatin remodeling and meiosis. Polyubiquitination involves DNA damage and repair, targets modified proteins to proteasomal degradation, and includes immune signal transduction (17). Chen et al. suggest that ubiquitination has become a key regulator of the immune system involved in transduction of intracellular signals, control of T cell differentiation, and induction of immune tolerance (57). The ubiquitination regulatory pattern recognizes receptor signaling, initiates adaptive immune responses, and maturates dendritic cells required to mediate innate immune responses. For T cells, ubiquitination regulates their development, activation, and differentiation to thereby maintain immune tolerance to their own tissues and an effective adaptive immune response to pathogens (20). The role of ubiquitination in immune regulation was first discovered in studies of antigen presentation and transcription factor nuclear factor NFκB family (58). The transcription factor nuclear factor NF-κB controls basic functions of many cells, including cell proliferation, immune responses, and apoptosis (59). Excessive apoptosis can result in anemia, neurodegenerative diseases, and graft rejection. A reduction of apoptosis can lead to autoimmune diseases and cancer. Therefore, moderate apoptosis is of great importance to the body. Ubiquitination of apoptotic proteins is a key component of the apoptosis signaling cascade (60). The ubiquitination mentioned above has an effect on DNA damage and repair. Improper response of DNA damage might accelerate the aging process, cause genomic instability, and eventually lead to various human diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases and cancer (61). Ubiquitination plays an important role to regulate the tumor suppressor function of Beclin1 (62). Thus, ubiquitination might play a crucial part in cancer. Some publications have described that ubiquitination disorders affect the occurrence, development, and metastasis of cancer (22, 63, 64).

Ubiquitinated Proteins Regulated Diverse Biological Process

This study found the mainly GO biological processes were related to synthesis and metabolism of proteins, which included glycoprotein, amyloid precursor protein, regulation of proteasomal ubiquitin-dependent protein, etc. This result suggests that ubiquitinated proteins might be involved in the synthesis and metabolism of certain proteins. Our long-term proteomics studies found that the number of down-regulated proteins was much more than up-regulated proteins in different subtypes of NFPAs compared to control pituitaries (28), mRNA expressions of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes E2 and E3 were significantly increased in NFPAs (28), mRNA expression of ubiquitin specific protease 34 was significantly decreased in PAs (29), proteasome subunit alpha type 2 was nitrated in PAs (26), and the protein ubiquitination pathway was changed in NFPAs (30). It is well-known that synthesis and degradation of proteins in humans maintain in a dynamic balance. The increased number of down-regulated proteins in PAs might mean a disrupted balance between synthesis and degradation of proteins compared to control pituitaries. This study clearly found that ubiquitinated proteins in PAs were related to the synthesis and metabolism of proteins. The ubiquitinated proteasome system is one of the main pathways for intracellular protein degradation (8, 65, 66). Ubiquitination can achieve protein degradation by ubiquitinating the proteasome. Therefore, the increased number of these downregulated proteins in human NFPAs might undergo ubiquitination to result in more degradation of the proteins relative to normal pituitaries.

The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT signaling pathway is activated by many types of cellular and toxic damage and regulates basic cellular functions such as transcription, translation, proliferation, growth, and survival. Binding of growth factors to their receptor tyrosine kinase or G protein-coupled receptor stimulates the Ia and Ib PI3K subtypes, respectively. PI3K catalyzes the production of phosphatidylinositol-3, 4, 5-triphosphate on the cell membrane. PIP3 in turn acts as a second messenger to activate AKT. The activated AKT can control key cellular processes through phosphorylation involved in apoptosis, protein synthesis, metabolism, and cell cycle substrates. The PI3K-AKT signaling pathway is an important signaling pathway in cells, and its main function is to inhibit apoptosis and promote proliferation. In various malignant tumors, the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway is abnormally regulated to promote formation of new blood vessels, proliferation of tumor cells, and inhibition of apoptosis, and is closely related to tumor metastasis and invasion. The HVP90 inhibitor NVPAUY922 and the PI3K-mTOR inhibitor NVP-BEZ235, alone or in combination, have a significant effect on the apoptosis of cholangiocarcinoma cells; and these inhibitors act on the rat model of cholangiocarcinoma to decrease the tumor (67). These results indirectly indicate that activation of PI3K-AKT signaling pathway contributes to the proliferation of cholangiocarcinoma cells. Study also found that the P110α subunit of PI3K is a regulator of angiogenesis, and the inactivation of P110α leads to non-functional angiogenesis, which in turn prevents tumor growth (68). In the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, the key molecules are cytokine, ECM, ITGB, and 14-3-3. Lamnin subunit gamma2 (LAMC2), which is a molecule in ECM, has been reported to be involved in the development and progression of various tumors (69). Smith et al. (70) found that LAMC2 was associated with bladder cancer metastasis, and its expression level increased with an increase of human tumor stage. In colorectal cancer, stable overexpressed LAMC2 promotes proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells (71). The grade of LAMC2 expression was significantly associated with the pattern and depth of invasion of oral squamous cell carcinoma (72). This study found that LAMC2 was ubiquitinated at position 219. PAs are generally benign tumors, and do not metastasize; however, they do proliferate and invade of tumor cells.

The core components of the Hippo signaling pathway include upstream and downstream regulatory factors, core kinase cassettes, and downstream oncogenes. The core kinase cassette includes Lats1/2, Mst2, SAV1, and Mob. Activation of the Lats1/2 phosphorylation of the transcriptional coactivators YAP and TAZ ultimately leads to apoptosis, limits organ size overgrowth, or promotes cell growth and proliferation (73). Therefore, the Hippo signaling pathway prevents tissue growth and tumorigenesis (74). However, the abnormality of this pathway usually leads to the occurrence of tumors (75). For example, when Lats1 is ubiquitinated, the kinase activity of Lats1 is reduced and subsequently inhibited by Hippo signaling only promotes cell proliferation, but also inhibits cell apoptosis and attenuates tumor suppressor function (76). NEDD4, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, can directly interact with Lats1 to lead to its ubiquitination and decreased levels of Lats to thereby increase the localization of nuclear YAP, and activate proliferative and anti-apoptotic genes (77). Lignitto et al. (78) found that the ubiquitination-proteasome system can degrade Mob to attenuate the Hippo cascade and maintain the growth of glioblastoma cells in vivo. So what is the impact of ubiquitination on the Hippo signaling pathway? Toloczko et al. (73) found that USP9X, a deubiquitinating protease, can enhance LATS kinase to inhibit tumor growth. Therefore, the Hippo signaling pathway is closely related to tumorigenesis, and the ubiquitination and deubiquitination of the core kinase cassette in the Hippo signaling pathway have a great influence on tumor growth. Therefore, ubiquitination and deubiquitination of the core kinase cassette are worthy of further study, and might lead to the development of new treatments for tumors. In addition, some key molecules in the Hippo signaling pathway are 14-3-3 protein and F-actin. The 14-3-3 protein in the Hippo signaling pathway is closely related to tumors.

The Ubiquitination of 14-3-3 Proteins in Pituitary Adenomas

Humans 14-3-3 proteins have many subtypes, including 14-3-3 protein beta/alpha, 14-3-3 protein gamma, 14-3-3 protein theta, etc. 14-3-3 subtypes are considered to play nocogenic roles in a variety of tumors (79). Raungrut et al. (80) found that 14-3-3 gamma is involved in the metastasis of lung cancer cells, and found that knockdown of 14-3-3 gamma could inhibit lung cancer metastasis. The 14-3-3 beta protein has been shown to possess carcinogenic potential, and its increased expression has been detected in many types of cancers. Tang et al. (81) found that 14-3-3 beta promotes migration and invasion of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells by modulating expression of MMP2 and MMP9 through the PI3K/Akt/NF-κB pathway. Also, 14-3-3 τ can promote breast cancer invasion and metastasis by inhibiting RhoGDI (82). However, few studies are involved in the relationship of 14-3-3 zeta/delta proteins and tumorigenesis. This study found the 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein was ubiquitinated in pituitary control tissues but not in PA tissues. However, Western blot analysis found that 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein was highly expressed in NFPAs compared to control tissues. The ubiquitinated proteasome system is one of the major pathways for intracellular protein degradation (8, 65, 66). Ubiquitination can achieve protein degradation by ubiquitination of the proteasome. Thus, it is hypothesized that proteins can be degraded by ubiquitination modification to result in lower protein levels in tumors than control tissues. Therefore, up-regulated expression of 14-3-3 zeta/delta protein in NFPAs might be due to the decreased ubiquitination level, and contribute to pituitary tumorigenesis. These findings might provide a better basis for biomarker discovery and the early treatment of PA patients.

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

This study, for the first time, used anti-ubiquitin antibody (specific to K-ε-GG)-based label-free quantitative proteomics to identify protein ubiquitination profiling between NFPAs and control pituitaries. A total of 158 ubiquitinated sites in 108 ubiquitinated proteins was identified and quantified, which is the first ubiquitinome profile in NFPAs compared to controls. Further, pathway network analysis revealed alterations of multiple ubiquitination-involved signaling pathway systems in NFPAs to offer novel insights into molecular mechanisms of NFPAs and to provide a new source to discover new biomarkers for NFPAs. However, one must realize that a ubiquitinome is dynamic, and varies with different conditions and pathophysiological status. PAs are highly heterogeneous among tumor individuals, different subtype of NFPAs, and different subtypes of FPAs. In order to further in-depth insight into functional significance of each ubiquitination in PA pathogenesis, one must significantly expand the number of human tissue samples studied to validate and quantify each ubiquitination among individuals and different PA subtypes; also, biological functions of each ubiquitination should be examined in the cell model and animal model. For this current study, due to the very limited, precious pituitary adenoma and control tissue samples, only very limited amount of proteins were used for trypsin digestion, anti-ubiquitin antibody-based enrichment, and LC-MS/MS analysis. The number of ubiquitinated sites and ubiquitinated proteins might be significantly increased with an increased amount of proteins in future ubiquitinomics analysis among PA individuals and among different PA subtypes, to significantly expand the ubiquitinome database of PAs, which will offer the increased opportunity to in-depth explore biological roles of protein ubiquitination in PAs.

Conclusion

Ant-ubiquitin antibody-based label-free quantitative proteomics effectively identified and quantified protein lysine ubiquitination in human PAs compared to controls. This study provides the first protein ubiquitination profiling of human PAs and control pituitaries to understand ubiquitination-mediated multiple cellular functions and biological processes. This study expanded the range of physiological processes regulated by ubiquitination, and serves as a valuable reference for biological functions of protein ubiquitination in human PAs.

Ethics Statement

PA tissues were obtained from the Department of Neurosurgery of Xiangya Hospital, China, as approved by the Xiangya Hospital Medical Ethics Committee of Central South University. Control pituitary tissues were obtained from the Memphis Regional Medical Center (n = 5), as approved by University of Tennessee Health Science Center Internal Review Board. The consent was attained from each patient or the family of each control pituitary subject (post-mortem tissues) after full explanation of the purpose and nature of all experimental procedures.

Author Contributions

SQ analyzed data, carried out Western blot experiment, prepared figures and tables, designed and wrote the manuscript. XhZ participated in the analysis, and revised the manuscript. ML and NL participated in partial data analysis. YL prepared the protein samples. XL collected tissue samples and performed clinical diagnosis. DD provided the control tissues, and critically evaluated and revised the manuscript. XqZ conceived the concept, designed experiments and manuscript, instructed experiments, analyzed data, obtained the ubiquitinated proteomic data, supervised results, coordinated, wrote and critically revised manuscript, and was responsible for its financial supports and the corresponding works. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BP

biological process

- CC

cellular component

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- FPA

functional pituitary adenoma

- GO

gene ontology

- HCD

higher-energy collisional dissociation

- HPLC

high performance liquid chromatography

- IAP

immunoaffinity purification

- LAMC2

lamnin subunit gamma 2

- LC

liquid chromatography

- MF

molecular function

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- NER

nucleotide excision repair

- NFPA

nonfunctional pituitary adenoma

- PA

pituitary adenoma

- PI3K

phosphatidylinostiol 3-kinase

- PTMs

post-translational modifications

- TFA

trifluoroacetate.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the grants from the China 863 Plan Project (Grant No. 2014AA020610-1 to XqZ), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81572278, 81272798, and 81770781), the Hunan Provincial Hundred Talent Plan (to XqZ), the Xiangya Hospital Funds for Talent Introduction (to XqZ), and the Hunan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 14JJ7008 to XqZ).

References

- 1.Zhan X, Wang X, Cheng T. Human pituitary adenoma proteomics: new progresses and perspectives. Front Endocrinol. (2016) 7:54. 10.3389/fendo.2016.00054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy A. Molecular and trophic mechanisms of tumorigenesis. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. (2008) 37:23–50. 10.1016/j.ecl.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaffe CA. Clinically non-functioning pituitary adenoma. Pituitary. (2006) 9:317–21. 10.1007/s11102-006-0412-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andela CD, Lobatto DJ, Pereira AM, van Furth WR, Biermasz NR. How non-functioning pituitary adenomas can affect health-related quality of life: a conceptual model and literature review. Pituitary. (2018) 21:208–16. 10.1007/s11102-017-0860-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenman Y, Stern N. Non-functioning pituitary adenomas. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2009) 23:625–38. 10.1016/j.beem.2009.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tampourlou M, Fountas A, Ntali G, Karavitaki N. Mortality in patients with non-functioning pituitary adenoma. Pituitary. (2018) 21:203–7. 10.1007/s11102-018-0863-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penn DL, Burke WT, Laws ER. Management of non-functioning pituitary adenomas: surgery. Pituitary. (2018) 21:145–53. 10.1007/s11102-017-0854-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mettouchi A, Lemichez E. Ubiquitylation of active Rac1 by the E3 ubiquitin-ligase HACE1. Small GTPases. (2012) 3:102–6. 10.4161/sgtp.19221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Popovic D, Vucic D, Dikic I. Ubiquitination in disease pathogenesis and treatment. Nat Med. (2014) 20:1242–53. 10.1038/nm.3739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo Z, Zhang X, Zeng W, Su J, Yang K, Lu L, et al. TRAF6 regulates melanoma invasion and metastasis through ubiquitination of Basigin. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:7179–92. 10.18632/oncotarget.6886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin AW, Man HY. Ubiquitination of neurotransmitter receptors and postsynaptic scaffolding proteins. Neural Plast. (2013) 2013:432057. 10.1155/2013/432057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao C, Huang W, Kanasaki K, Xu Y. The role of ubiquitination and sumoylation in diabetic nephropathy. Biomed Res Int. (2014) 2014:160692. 10.1155/2014/160692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xiao Z, Zhang P, Ma L. The role of deubiquitinases in breast cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. (2016) 35:589–600. 10.1007/s10555-016-9640-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hock AK, Vousden KH. The role of ubiquitin modification in the regulation of p53. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1843:137–49. 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.05.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ding F, Yin Z, Wang HR. Ubiquitination in rho signaling. Curr Top Med Chem. (2011) 11:2879–87 10.2174/156802611798281357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulda S, Rajalingam K, Dikic I. Ubiquitylation in immune disorders and cancer: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. EMBO Mol Med. (2012) 4:545–56. 10.1002/emmm.201100707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou MJ, Chen FZ, Chen HC. Ubiquitination involved enzymes and cancer. Med Oncol. (2014) 31:93. 10.1007/s12032-014-0093-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vadasz I, Weiss CH, Sznajder JI. Ubiquitination and proteolysis in acute lung injury. Chest. (2012) 141:763–71. 10.1378/chest.11-1660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebner P, Versteeg GA, Ikeda F. Ubiquitin enzymes in the regulation of immune responses. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. (2017) 52:425–60. 10.1080/10409238.2017.1325829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu H, Sun SC. Ubiquitin signaling in immune responses. Cell Res. (2016) 26:457–83. 10.1038/cr.2016.40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawabe H, Brose N. The role of ubiquitylation in nerve cell development. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2011) 12:251–68. 10.1038/nrn3009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrow JK, Lin HK, Sun SC, Zhang S. Targeting ubiquitination for cancer therapies. Future Med Chem. (2015) 7:2333–50. 10.4155/fmc.15.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng N, Shabek N. Ubiquitin ligases: structure, function, and regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. (2017) 86:129–57. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehman NL. The ubiquitin proteasome system in neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. (2009) 118:329–47. 10.1007/s00401-009-0560-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu M, Knox AJ, Michaelis KA, Kiseljak-Vassiliades K, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Lillehei KO, et al. Reprimo (RPRM) is a novel tumor suppressor in pituitary tumors and regulates survival, proliferation, and tumorigenicity. Endocrinology. (2012) 153:2963–73. 10.1210/en.2011-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhan X, Desiderio DM. Nitroproteins from a human pituitary adenoma tissue discovered with a nitrotyrosine affinity column and tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. (2006) 354:279–89. 10.1016/j.ab.2006.05.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhan X, Desiderio DM. A reference map of a human pituitary adenoma proteome. Proteomics. (2003) 3:699–713. 10.1002/pmic.200300408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moreno CS, Evans CO, Zhan X, Okor M, Desiderio DM, Oyesiku NM. Novel molecular signaling and classification of human clinically nonfunctional pituitary adenomas identified by gene expression profiling and proteomic analyses. Cancer Res. (2005) 65:10214–22. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Evans CO, Moreno CS, Zhan X, McCabe MT, Vertino PM, Desiderio DM, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of human prolactinomas identified by gene expression profiling, RT-qPCR, and proteomic analyses. Pituitary. (2008) 11:231–45. 10.1007/s11102-007-0082-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhan X, Wang X, Long Y, Desiderio DM. Heterogeneity analysis of the proteomes in clinically nonfunctional pituitary adenomas. BMC Med Genomics. (2014) 7:69. 10.1186/s12920-014-0069-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Fang L, Zhu X, Wang D, Xiao S. Global analysis of ubiquitome in PRRSV-infected pulmonary alveolar macrophages. J Proteomics. (2018) 184:16–24. 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen XL, Xie X, Wu L, Liu C, Zeng L, Zhou X, et al. Proteomic analysis of ubiquitinated proteins in rice (Oryza sativa) after treatment with pathogen-associated molecular pattern (PAMP) elicitors. Front Plant Sci. (2018) 9:1064. 10.3389/fpls.2018.01064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]