Abstract

We conducted a bilingual literature review of the existing studies focusing on person-centered dementia care in China. We synthesized key findings from included articles according to three overarching themes: Chinese cultural relevance of person-centered care (PCC), perceived needs for PCC for older adults in China, implementation and measurement of PCC in China, and person-centered dementia care model. We also drew on frameworks, theories, and other contents from the examined articles to develop a person-centered dementia care model with specific relevance to China. The model is a good starting point to help us operationalize globally relevant core principles of PCC in the specific sociocultural context of China. The framework will be informed by more empirical studies and evolve with the ongoing operationalization of PCC. Although PCC is a new concept and has not been vigorously or systematically studied in China, it is attracting increasing attention from Chinese researchers. More empirical studies are needed to link PCC to measurable outcomes, enrich the framework for applying PCC, and construct assessment and evaluation systems to facilitate the provision of PCC across countries and cultures. Global consortia and collaborations with multidisciplinary expertise to develop a PCC common data infrastructure that is internationally relevant for data sharing and comparison are needed.

Keywords: person-centered care, dementia care, China, culture, literature review

Introduction

In 2018, more than 50 million people worldwide were living with dementia, nearly 60% in developing countries, with the fastest growth taking place in China (Prince et al., 2013; Wimo et al., 2017; Winblad et al., 2016). The current number of older adults diagnosed with dementia in China reached 8.18 million in 2015; on average, more than 360,000 new cases are diagnosed every year (Li et al., 2015). Overall, there is a shortage of quality workforce at all levels and a lack of variety of services and programs provided in China’s long-term care (LTC) system (Song, Anderson, Corazzini, & Wu, 2014). In contrast to the substantial increase in the overall population with dementia in China, there is very limited availability of residential care services and a severe lack of community-based services for persons with dementia and their informal caregivers (Hsiao, Liu, Xu, Huang, & Chi, 2016; Wang, Xiao, & Li, 2018). Many LTC facilities do not admit persons with dementia, mainly due to lack of trained staff and limited space in these facilities (Wang, Wang, Cao, Jia, & Wu, 2018; Wu, Mao, & Zhong, 2009). Also, there is a strong cultural preference for aging in place among older adults and their family members (Sereny, 2011). Thus, informal caregivers (i.e., their family members, relatives, friends, and other unpaid caregivers) play a major role in caring for persons with dementia in China (Wang, Xiao, He, & De Bellis, 2014). This contrasts sharply with care approaches in community and LTC settings. In big cities of China, older adults with cognitive impairment can go to memory clinics in tertiary hospitals for diagnosis, cognitive assessment, and prescriptions. Some older adults with dementia reside in LTC facilities or community hospitals despite the limited availability of dementia-specific programs. The ethos of caring for persons with dementia in health care systems is medically dominated, disease oriented, and task focused (Xu, Hsiao, Deng, & Chi, 2018). Care providers tend to prioritize routines and tasks ahead of the individualized preferences of persons with dementia (Wang, Wang, Cao, Jia, & Wu, 2016). In contrast, in Western Europe and North America, the past decade has seen a significantly increased commitment to person-centered care (PCC) that is relationship focused, collaborative, and holistic for persons with dementia, where the focus is on quality of life as perceived by care recipients/patients, and staff and care recipients share a feeling of community and belonging (Fazio, Pace, Flinner, & Kallmyer, 2018; Love & Pinkowitz, 2013; Winblad et al., 2016).

Generally known as the founder of the concept of person-centered dementia care, Tom Kitwood’s influential work emphasized the importance of giving voice to, and supporting, personhood of persons with dementia by establishing systems of care that facilitate deep and mutually empathic relationships between people (Kitwood & Bredin, 1992). Kitwood’s work recognizes that the personhood of persons with dementia is neither diminished nor lost, but rather is concealed, as those relationships become impaired over the progression of the disease (Kitwood, 1993). Since then, there has been significant conceptual and theoretical advancement in PCC, such as the “senses framework” (Nolan, Davies, Brown, Keady, & Nolan, 2004), conceptualization of core concepts of person-centered dementia care (Edvardsson & Innes, 2010), and the person-centered nursing framework (McCormack & McCance, 2006, 2010). The most consistently applied and fundamental philosophical prerequisites of person-centered dementia care in the literature are that all persons with dementia are recognized as valuable and competent; as having dignity, autonomy, and worth; and deserving of full respect (Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh, & Nay, 2010; Kitwood, 1993). Core principles of person-centered dementia care include knowing and valuing the person with dementia, interpreting behaviors from the person’s viewpoint, promoting a continuation of self and normality, providing a positive social environment in which they can live well, with opportunities to establish relationships that have therapeutic benefits and nurture relationships in the wider community (Love & Pinkowitz, 2013; McCormack & McCance, 2006). This has profound implications for how care is provided to people with dementia. Person-centered dementia care is responsive to the preference of the person with dementia and contingent upon knowing the person through an interpersonal relationship. Shifting the focus of PCC from individual needs to a relationship-centered focus on interactions among all persons involved in caring relationships is also recommended (Nolan et al., 2004). Strategies for delivery of PCC include weaving information about the person into every interaction and activity, providing validation therapy, prioritizing the person’s well-being ahead of routines and care tasks, staying in the present, and looking for opportunities for meaningful engagement beyond scheduled activities (Edvardsson et al., 2010). Although little empirically rigorous research has tested the effects of person-centered dementia care, person-centered dementia care has been shown to promote caregivers’ sense of achievement and improve caregiver relationships with care recipients by guiding caregivers to increase focus on interactions with care recipients (Edvardsson, 2015). The literature also indicates that caregivers are less likely to experience role strain with a focus on relationship than with a focus on care tasks, specific conditions, and symptoms (Edvardsson, Winblad, & Sandman, 2008).

Currently available studies have been predominantly focused on populations in Western European and North American countries. Although PCC has become a priority in dementia care in these countries (Bartlett & O’Connor, 2007; Chenoweth et al., 2009; Penrod et al., 2007), it is still a relatively new concept in China. Although the core principles of person-centered dementia care may be globally relevant and not culturally specific, however, how to implement person-centered dementia care in daily practice is influenced by social and cultural contexts. Medically dominated and task-oriented care models interfere with the awareness and appreciation of person-centered dementia care. Furthermore, even though some caregivers might innovate their own person-centered approaches based on their knowledge of the person with dementia, such strategies can be unsustainable if not fully supported and appreciated. Thus, with the growing population of people with dementia in China, and the need to improve quality of care for persons with dementia in LTC and community care settings, it is important to explore the concept of person-centered dementia care in China. Therefore, we conducted a literature review to understand the relevance and appreciation for person-centered dementia care in China and to identify any cultural concepts that might affect uptake of person-centered dementia care in China.

Approach

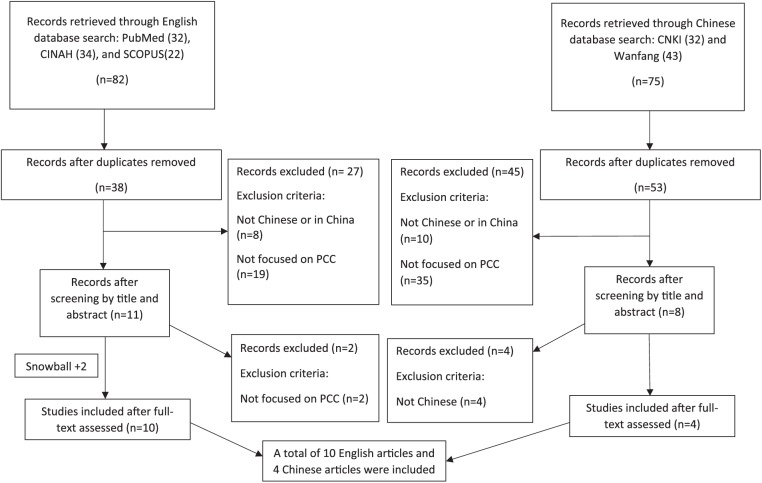

Our team is transnational and bilingual and emerged from the WE-THRIVE collaborative, which engaged LTC researchers in China, United States, and numerous other countries in collaborative international LTC research (Corazzini et al., 2019). We conducted a bilingual, English and Chinese, literature review on person-centered dementia care in China. Our initial literature search had scant results, so we broadened the search terms to include literature on PCC in China. We collected, screened, and analyzed literature in English and Chinese, as described below and depicted in the flow chart (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Databases search results

In English, we searched PubMed, the Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and SCOPUS. We used indexed vocabulary and keywords—including “person-centered (centred) care,” “person-centeredness (centredness),” “personhood,” “individualized (individualised) care,” “senses framework,” “relationship-centred care,” “empowerment,” and “shared decision making”—and found 82 articles with our search terms in their titles or abstracts. After removing duplicates, 38 articles remained. We reviewed the titles and abstracts and excluded articles that did not address person-centered dementia care, PCC, or core concepts of PCC of older adults and that did not occur in China. Two additional articles were culled from article reference lists. At the end of this search process, we retained 10 English articles, with five conducted in Mainland China and five in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

We also searched two Chinese databases, that is, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and Wanfang, using Chinese keywords related to PCC. After removing duplicates, 53 articles were retrieved, among which, most articles used PCC as a not clearly defined concept in health care that is consistent with the Chinese socialist concepts “harmonious society” and “human-oriented outlook on development.” The full text of the remaining eight articles was then reviewed. Two articles reviewed person-centered therapeutic interventions among persons with dementia in Western countries (excluded); two articles talked about benefits of PCC based on studies and experience in Western countries (excluded). Finally, four articles were retained. Therefore, we included nine English and four Chinese articles (see Figure 1).

We extracted information from each article into a matrix (Garrard, 2013) summarizing basic information and key findings (see Table 1). We read through the articles to extract content related to how PCC is defined, operationalized, measured, and discussed to identify themes among articles, and we analyzed and synthesized the findings by themes in the current literature review. We drew upon the PCC conceptual frameworks and models in Western Europe and North America, including the person-centered nursing framework (McCormack & McCance., 2006) and senses framework (Nolan et al., 2004) to outline a conceptual framework of person-centered dementia care in China. We used the synthesized findings from the included articles to further develop and describe the person-centered dementia care model (see Figure 2).

Table 1.

Summary of Literature Review Findings.

| Year | Author | Research country | Title | Type | Journal | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | F-J. Shih | China | “Concepts Related to Chinese Patients’ Perceptions of Health, Illness, and Person: Issues of Conceptual Clarity” | Concept analysis | Accident and Emergency Nursing | The philosophies related to the concept of personhood not only influence Chinese patients’ values and beliefs but also determine their perceptions of health, illness and nursing care |

| 2007 | Julia Tao and Lai Po Wah | Hong Kong, China | “Dignity in Long-Term Care for Older Persons: A Confucian Perspective” | Theoretical | Journal of Medicine and Philosophy | The insights of the Mencian theory of human dignity are used to provide a moral foundation for LTC for elder persons in a context of diminishing personhood and shrinking autonomy |

| 2017 | Sui-Ting Kong, Christine Meng-Sang Fang, and Vivian W. Q. Lou | Hong Kong, China | “Solving the ‘Personhood Jigsaw Puzzle’ in Residential Care Homes for the Elderly in the Hong Kong Chinese Context” | Empirical | Qualitative Health Research | Narratives from medical and social care practitioners in care homes demonstrated their understanding of the practice processes: “understanding the person-in-relationship and person-in-time,” “identifying the personhood-inhibiting experiences,” and “enabling personalized care for enhanced psychosocial outcomes” |

| 2010 | N. L. Chappell and K. L. Chou | Hong Kong, China | “Chinese Version of Staff-Based Measures of Individualized Care for Institutionalized Persons With Dementia” | Empirical | Asian Journal of Gerontology and Geriatrics | Staff-based measures of three domains of IC for institutionalized persons with dementia can be used in Chinese for both research and administrative purposes |

| 2013 | Xuebing Zhong, and Vivian Lou | Xi’an, China (Mainland) | “Person-Centered Care in Chinese Residential Care Facilities: A Preliminary Measure” | Empirical | Aging & Mental Health | P-CAT-C is a culturally adapted version of the original P-CAT, and showed satisfactory reliability and validity for evaluating person-centered dementia care in Chinese LTC care facilities |

| 2016 | Mao, P., Xiao, D., Zhang, M., Xie, F., and Feng, H. | Hunan, China | “Hunan Sheng Yanglao Jigou Chidai Zhaohu Danyuan Yirenweizhongxin de Zhaohu Xianzhuang Fenxi” [“Person-Centered Dementia Care in Eldercare Institutions in Hunan Province”] | Empirical | Journal of Nursing Sciences (Chinese) | The Chinese version of the P-CAT was used to evaluate the person centeredness of Chinese nursing homes. Results showed that the organizational support for PCC is extremely low. It also found that staff’s age and educational level is significantly associated with P-CAT scores |

| 2017 | Le Cai, Gerd Ahlström, Pingfen Tang, Ke Ma, David Edvardsson, Lina Behm, Haiyan Fu, Jie Zhang, and Jiqun Yang | Kunming, China (Mainland) | “Psychometric Evaluation of the Chinese Version of the PCQ-S” | Empirical | BMJ Open | The Chinese version of the PCQ-S showed satisfactory reliability and validity for assessing staff perceptions of person-centered care in Chinese hospital environments |

| 2018 | Yang, Yun., Xiao, D., Mao, P., Xia, M., Zhang, W., and Feng, H. | China (Mainland) | “Yirenweizhongxin de Yanglaojigou Zhaohuhuanjing Wenjuan” [“Research on Reliability and Validity of Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire-Staff Version in Pension Institution”] | Empirical | Chinese Nursing Research (Chinese) | The Chinese version of the PCQ-S showed satisfactory reliability and validity for assessing the person-centered climate among staff in nursing homes in China |

| 2012 | Xuebing Zhong and Vivian Lou | Hong Kong, China | “Practice Person-Centered Care for Demented Older Adults in Hong Kong Residential Care Facilities: A Qualitative Exploration” | Empirical | Asian Health Care Journal | Managers from different residential care facilities have a diversified understanding of PCC; a variety of practices have been identified as a strong identification toward PCC |

| 2018 | Yao Wang, Lily Dongxia Xiao, Yang Luo, Shui-Yuan Xiao, Craig Whitehead, and Owen Davies | Shangshai, China (Mainland) | “Community Health Professionals’ Dementia Knowledge, Attitudes and Care Approach: A Cross-Sectional Survey in Changsha, China” | Empirical | BMC Geriatrics | Health care professionals from community health service centers have positive attitudes toward PCC and their attitudes are influenced by age, professional group, gender, and care experience |

| 2018 | Jing Wang, Junqiao Wang, Yuling Cao, Shoumei Jia, and Bei Wu | Shanghai, China (Mainland) | “Perceived Empowerment, Social Support, and Quality of Life Among Chinese Older Residents in Long-Term Care Facilities” | Empirical | Journal of Aging and Health | Older residents’ perceived empowerment is positively associated with their QOL. The low scored items are related to lack of knowledge and awareness of facility staff |

| 2017 | Yao Wang, Lily Dongxia Xiao, Shahid Ullah, Guo-Ping He, and Anita De Bellis | Changsha, China (Mainland) | “Evaluation of a Nurse-Led Dementia Education and Knowledge Translation Program in Primary Care: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial” | Empirical | Nurse Education Today | Findings revealed significant effects of the education and knowledge translation program on participants’ knowledge, attitudes, and tendency to employ a person-centered dementia care approach |

| 2016 | Zhao, J., Wang, J., Jiang, Y., Han, L., Liu, X., Gao, S., and Hao, Y. | China (Mainland) | “Yirenweizhongxin de Laonian Zhaohu Moshi Yanjiu Jinzhan” [“A Review of Person-Centered Care for the Elderly”] | Review | Journal of Nursing Sciences (Chinese) | There is a lack of understanding of PCC in China. There is an urgent need to explore and develop a culturally sensitive PCC model in China |

| 2017 | Zhao, X. | China (Mainland) | “Weirao Yi Laorenweizhongxin zhaohu Linian Jinxing Sheji” [“Older Adults-Centered Care Design”]. Ei | Review | City & House (Chinese) | There is an urgent need of creating a person-centered environment for older adults to improve quality of care in nursing homes in China |

Note. IC = individualized care; P-CAT = Person-Centered Care Assessment Tool; LTC = long-term care; PCC = person-centered care; PCQ-S = Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire–Staff Version; QOL = quality of life; P-CAT = Person-centered Care.

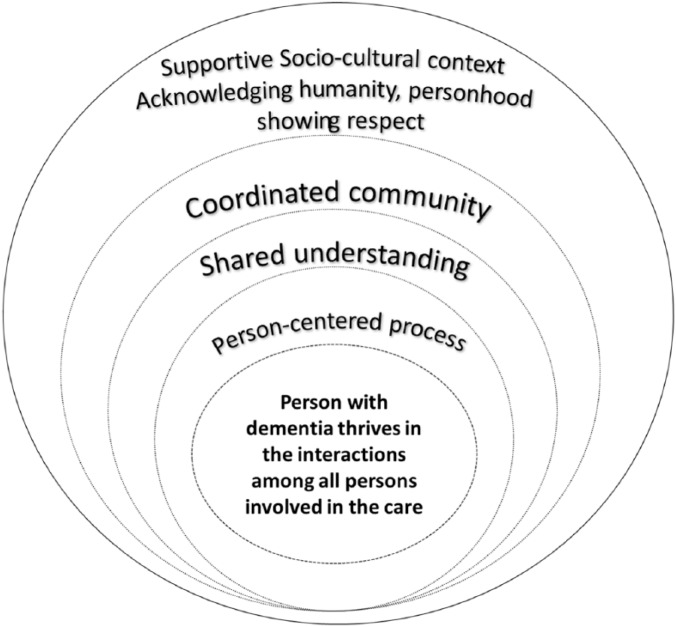

Figure 2.

Model of person-centered dementia care in China.

Findings

We learned from the four Chinese language articles that PCC is a new concept in China, organizational support for PCC is extremely limited, and there is an identified need to understand, develop, and implement PCC in China. The 10 English language articles provided information on cultural understandings of personhood, operationalization, and measurement of core concepts of PCC, and barriers and facilitators of implementing PCC in China. Across the literature, three articles identified the importance of and need for having PCC in LTC facilities in China (Wang et al., 2018; X. Zhao, 2017; J. Zhao et al., 2016). Four articles assessed LTC managers’ and employees’ knowledge of and attitudes toward PCC, not only showing that community health care providers, managers, and staff tend to have positive attitudes toward PCC but also demonstrating a relatively poor understanding of and a lack of skill competence toward PCC (Kong, Fang, & Lou, 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2017; Zhong & Lou, 2012). Mao, Xiao, Zhang, Xie, and Feng (2016) used the Person-Centered Care Assessment Tool (P-CAT) to assess the level of person centeredness in LTC facilities in China and found that direct care staff rated organizational support for PCC as extremely low. Four articles adapted person-centered dementia care tools, including P-CAT (Zhong et al., 2013), Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire–Staff Version (PCQ-S; Cai et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018), and staff-based measures of individualized care (IC; Chappell & Chou, 2010), and tested their validity and credibility. One article evaluated an educational intervention to promote community health care providers’ knowledge of and tendency to use a person-centered dementia care approach (Wang, Xiao, & Li, 2016). We organized our analysis and synthesis of these articles into the following themes: Chinese cultural relevance of PCC, perceived needs for PCC for older adults in China, implementation and measurement of PCC in China, and person-centered dementia care model.

Chinese Cultural Relevance of PCC

Chinese culture can serve as a premise or facilitator for operationalizing PCC but some values and notions in Chinese culture can be barriers to applying PCC in China. In Confucian philosophies, interpersonal and social interactions are based on reciprocity, loyalty, benevolence, self-respect, self-control, and face saving (Wah & Tao, 2007). The Chinese concept of personhood emphasizes interpersonal transactions. It focuses on whether the individuals’ behavior fits or fails to fit the interpersonal standards of society and culture (Kong et al., 2017). Maintaining a long-term harmonious relationship with their caregivers is a basic expectation for older adults in China. An unstable or distrustful relationship with their caregivers will make them feel insecure, and, therefore, discourages them from expressing their needs and challenges (Liou & Jarrott, 2013). They also tend to value caregivers’ attitudes more than professional knowledge and skills. Older adults would expect paid caregivers to be as supportive and caring as they would be to their own families (Wah & Tao, 2007). If caregivers fail to use verbal and nonverbal symbols perceived as supportive and caring, such as hand holding and smiling, older adults might become anxious, self-blaming, and reluctant to communicate with caregivers about their feelings and needs (Shih, 1996; Wah & Tao, 2007).

Chinese family values and the social expectations of filial piety work together to place relationships at the very core, consistent with applying PCC in different care settings. It is a social obligation for them to provide their family in need with direct care at home or assistive care and supervision in LTC settings (Holroyd, 2001). Thus, incorporating the family in the plan of care and supporting their care is consistent with both Chinese cultural expectation and PCC. In traditional culture, Chinese strive to maintain harmony with nature, social institutions, and in human relationships. To be in harmony means to follow the expectations of “sincerity, loyalty, filial piety, and benevolence and to avoid negativism and emotional outburst” (Chen-Louie, 1983, p. 200). Thus, Chinese older adults and caregivers tend to avoid direct confrontations and disclosures of personal difficulties within the family (Au, Shardlow, Teng, Tsien, & Chan, 2013). This may prevent them from directly expressing their feelings and dissatisfaction with significant others.

Traditional Chinese culture, particularly Confucianism, recognizes treating others with dignity as a core concept in thought and moral practice. It fully acknowledges one’s humanity, particularly those with cognitive challenges or functional limitations (Kong et al., 2017). It recognizes human dignity as realized through relationships and interactions between self and others, which echoes the values of PCC and the senses framework (Nolan et al., 2004). The Chinese term for dementia has negative connotations such as being confused and losing one’s mind or being catatonic, triggering social and individual stigma. This situation may also cause an individual and their family to lose face in interpersonal relationships (Dai et al., 2013). Despite the Confucianist mandate to respect the dignity of others, patients are seen as weak, dependent, and vulnerable persons, needing help and protection from their families (Kong et al., 2017). In contrast to the defining of the person in PCC, persons with dementia in Chinese culture tend to be regarded as patients who passively receive care from their formal or informal caregivers (Dai et al., 2013). This perception serves as a potential cultural barrier to acknowledging persons with dementia as valuable and competent persons who deserve opportunities to be engaged in meaningful social networking and make decisions for themselves.

Perceived Need for PCC for Older Adults in China

Studies offer evidence that PCC is valued by older adults in LTC facilities and is much needed in China. We found that older adults in China value and desire autonomy, a sense of identity, meaning in life, and a sense of empowerment in LTC facilities, consistent with the core concepts of PCC. A study focusing on dignity and personhood in LTC facilities in Hong Kong found that older adults fear losing autonomy, personal independence, freedom, and choice in LTC facilities (Wah & Tao, 2007). The authors highlighted a profound need to maintain older adults’ human dignity through helping them to obtain a sense of identity and meaning in life. A study investigated the relationship among older adults’ perceived empowerment, social support, quality of life, and their lived experience in the LTC facilities (Wang et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). The findings identify multiple challenges facing older residents, including threats to their senses of belonging and dignity deriving from the care model and facility culture that inhibit their ability to interact with other residents and staff in a personally meaningful manner. Some older residents’ sense of belonging and dignity were threatened when LTC facilities put efficiency of care ahead of residents’ well-being. Residents expressed a strong desire for greater respect for their dignity, privacy, and personal values; they longed for a home-like environment where services and care were tailored to their personal preferences. They hoped to have more opportunities for social interactions and recreation within and outside LTC facilities (Wang et al., 2016). The study also found that older residents reported a significant lack of perceived empowerment, whereas a higher level of perceived empowerment from the care that they received is associated with a better self-rated quality of life (Wang et al., 2018). The study pointed out the importance of implementing PCC, which also was emphasized by one of the literature reviews in Chinese, which suggested a need to develop a PCC model with culturally specific implementation approaches in China (J. Zhao et al., 2016).

Implementation and Measurement of PCC in China

Implementation of PCC in Chinese LTC facilities is just beginning to be studied systematically. Three articles addressed the staff/caregiver-based measurements of PCC in LTC facilities in China, advancing the ability to measure and conduct research on PCC. A staff-based scale related to IC for older residents in LTC facilities was introduced and validated in Hong Kong (Chappell & Chou, 2010). The tool includes four subscales that measure staff perceptions of their knowledge of residents (Know scale), the general environment in which the staff work (Autonomy scale), staff communication with one another and supervisors within the LTC home (Communication-SS scale reflects), and staff communication with residents (Communication-SR scale). Results show that the tool is valid and can be used among caregivers in Hong Kong for both research and care purposes. Zhong et al. (2013) validated the Chinese version of P-CAT among 330 formal caregivers in 34 LTC facilities in a northwestern city in China after translation, back translation, and adaptation of the tool based on literature review and expert consultation. Results show that further study is needed to test the cultural sensitivity, reliability, and validity of the tool among Chinese caregivers in LTC settings. Mao et al. (2016) used P-CAT among 112 formal caregivers in 20 LTC facilities in Hunan Province, China. They found that caregivers’ age and educational background were positively associated with the P-CAT scores and called for hiring nursing aides who are younger and have a higher educational level. Yang et al. (2018) validated the Chinese version of PCQ-S in LTC facilities in Hunan, China. Cai et al. (2017) translated and validated PCQ-S tool in three hospitals in Yunan, China. The two studies showed that PCQ-S can be used to assess the person-centered climate in both nursing homes and hospitals in China with a good validity and reliability.

Several studies identified good practices toward, and major barriers to, implementing PCC in Hong Kong and Mainland China. Zhong and Lou., (2012) explored PCC practices for older residents with dementia in LTC facilities in Hong Kong using Brooker’s four major elements of PCC to guide the interview. They interviewed 11 managers of LTC facilities in Hong Kong about their perceptions, daily practices, and barriers relating to PCC for older residents with dementia. They found that managers had varied and inconsistent understandings of PCC. Some put more weight on IC. Some viewed PCC as a similar approach to holistic care. And, others emphasized the importance of maintaining the dignity of persons with dementia. Good practices identified toward PCC are related to elements of the VIPS framework: (a) valuing older adults with dementia and their caregivers as a stepping stone of practicing PCC, (b) IC as a mechanism of practicing PCC, (c) continuous assessment as a pathway to practicing PCC, and (d) nurturing environment as a facilitator in practicing PCC (Røsvik, Kirkevold, Engedal, Brooker, & Kirkevold, 2011). Inconsistency of the conceptualization of PCC, an underprepared workforce, high work stress, and environmental constraints were reported as major barriers to integrating PCC in daily practices. One study conducted in Mainland China assessed community health care providers’ dementia knowledge, attitudes, and care approaches (Wang et al., 2018). They found that community health care providers tended not to use a PCC approach in dementia care due to a lack of knowledge, support from organizations, and experience caring for persons with dementia. Two studies in Mainland China identified lack of communication between staff and older residents and poor management support as major problems in providing PCC for frail older adults in China (X. Zhao, 2017; J. Zhao et al., 2016).

Person-Centered Dementia Care Model

Findings were combined in an overarching model of person-centered dementia care in China (see Figure 2). The person with dementia is at the heart of the model, thriving in interactions with all the persons who are involved in their care, which can be signified and evaluated by the achievement of favorable person-centered outcomes for the person, as well as from staff/managers and family caregivers, including senses of security, belonging, purpose, achievement, continuity, and significance (Nolan et al., 2004). Other PCC measures that were used and validated in the reviewed literature—such as P-CAT, IC, and PCQ-S—can also be adopted to evaluate PCC outcomes (Cai et al., 2017; Chappell & Chou, 2010; Yang et al., 2018; Zhong et al., 2013). Person-centered process—the next inner ring in the model of person-centered dementia care in China—supports the partnerships between persons with dementia and their care partners. Examples of person-centered process and practices include understanding care from the perspectives of the person with dementia, having sympathetic presence, sharing decision making, and prioritizing well-being ahead of routines and scheduled tasks (Edvardsson, Fetherstonhaugh and Lay, 2010; Fazio et al., 2018; Kong et al., 2017). The process is influenced by the shared understanding of core values and philosophies of PCC, which is currently lacking in China (Kong et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2018; Yao et al., 2017; Zhong & Lou, 2012). The next ring is coordinated community where all persons involved in the care of a person with dementia openly communicate with one other. Our literature informed us that family is the most important unit within the community (Wah & Tao, 2007). Chinese family values and the social expectations of filial piety place family relationships at the very core of the community. Thus, incorporating family in the plan of care and supporting family caregiving are the keys to building a coordinated community. Understanding of person-centered dementia care is never complete without taking culture and social values into consideration. Values and attitudes in the culture can serve as facilitators but can also be barriers to implementing PCC.

Discussion

PCC has not yet been clearly conceptualized in China. In Chinese literature, it is more of an abstract concept in health care that is consistent with the value of building a harmonious society and promoting human-oriented outlook or development. PCC has not been clearly operationalized or applied in daily practices nor has it been included in quality of care evaluations in the Chinese literature. Among the four articles in the Chinese language literature that we included, two research teams collaborated with researchers in Western Europe and Australia to introduce and validate PCC measures in China and to assess the person centeredness of LTC facilities using available tools. English-language literature discussed benefits of PCC, barriers to PCC, and introduced and validated self-rated caregiver-based tools that measure to what extent care staff rate their working setting and their care provided as person centered for older adults. Person-centered dementia care has gained increasing attention from researchers in China and the basic tenets of PCC are consistent with Chinese philosophy and culture but more studies are needed to define and understand it.

Understanding of PCC is never complete without taking traditional culture and social values into consideration. Chinese culture can serve as a premise or facilitator for operationalizing PCC in China, such as the concept of showing respect and treating others with dignity. However, some values and notions in Chinese culture can be barriers to applying PCC, such as the understanding of personhood, maintaining relational or family harmony at the expense of communicating or expressing oneself (Kong et al., 2017). Persons with dementia require a holistic, collaborative, and ongoing understanding from their care partners of their needs and preferred self to maintain meaningful social relationships and achieve a sense of belonging and continuity (McCormack & McCance., 2006). Because family members have major roles in caring for persons with cognitive impairment in China, it is not only important to carry out research on helping formal caregivers to initiate effective communication, build relationships with and involving family members in the care but also to guide informal caregivers to resources, and support them in person-centered, relationship-based approaches to maintaining well-being.

The model of person-centered dementia care in China that we developed based on the literature review may provide a starting point to help operationalize globally important principles of PCC in specific sociocultural contexts. It can also assist in understanding how the core of PCC—all persons involved in the care and their relationships—is influenced by the interplay of person-centered practices, shared understanding and value of PCC, and coordinated community, and how all these factors connect to the family values, personhood, and filial piety in Chinese culture. The framework can be further developed by more empirical studies and evolve with the ongoing operationalization of PCC.

The increasing understanding and recognition of the value of person-centered dementia care is significant particularly due to the growing prevalence of dementia in China and globally. This bilingual literature review informed us that the core values of personhood, as understood in other countries, are consistent with personhood in China. For example, The Chinese concept of personhood emphasizes interpersonal transactions (Kong et al., 2017), consistent with the senses framework (Nolan et al., 2004) and Kitwood’s (1993) theory. The review also helped us identify potential first steps toward understanding, developing, and implementing PCC in China, that is, to distinguish PCC practice from an abstracted concept and to better understand it by conducting more empirical studies that examine globally relevant PCC concepts with culturally specific approaches to gather information needed to provide PCC in China.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/ or publication of this article: The study was funded in part by a Duke University Graduate School Fellowship (PI: Wang) and Duke University School of Nursing Center for Nursing Research (Corazzini).

ORCID iDs: Jing Wang  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7791-671X

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7791-671X

Michael J. Lepore  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7117-4919

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7117-4919

Eleanor S. McConnell  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2896-8596

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2896-8596

References

- Au A., Shardlow S. M., Teng Y., Tsien T., Chan C. (2013). Coping strategies and social support-seeking behaviour among Chinese caring for older people with dementia. Ageing & Society, 33, 1422-1441. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R., O’Connor D. (2007). From personhood to citizenship: Broadening the lens for dementia practice and research. Journal of Aging Studies, 21(2), 107-118. [Google Scholar]

- Cai L., Ahlstrom G., Tang P., Ma K., Edvardsson D., Behm L., Yang J. (2017). Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Person-Centred Climate Questionnaire—Staff version (PCQ-S). BMJ Open, 7(8), e017250. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell N. L., Chou K. L. (2010). Chinese version of staff-based measures of individualized care for institutionalized persons with dementia. Asian Journal of Gerontology & Geriatrics, 5, 5-13. [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth L., King M. T., Jeon Y. H., Brodaty H., Stein-Parbury J., Norman R., …Luscombe G. (2009). Caring for Aged Dementia Care Resident Study (CADRES) of person-centred care, dementia-care mapping, and usual care in dementia: a cluster-randomised trial; The Lancet Neurology, 8(4), 317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen-Louie T. (1983). Nursing care of Chinese American patients. In Orque M. S., Bloch B., Ahumada Monrroy L. S. (Eds.), Ethnic nursing care: A multicultural approach (p. 200). St. Louis, MO: C. V. Mosby. [Google Scholar]

- Corazzini K., Anderson R. A., Bowers B. J., Chu C., Edvardsson D., Fagertun A., . . .Lepore M. (2019). Toward common data elements for international research in long-term care homes: advancing person-centered care. JAMDA: Journal of Post-acute and Long-term Care, 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.01.123 [epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Dai B., Mao Z., Mei J., Levkoff S., Wang H., Pacheco M., Wu B. (2013). Caregivers in China: Knowledge of mild cognitive impairment. PLoS ONE, 8(1), e53928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Fetherstonhaugh D., Nay R. (2010). Promoting a continuation of self and normality: person-centred care as described by people with dementia, their family members and aged care staff. Journal of clinical nursing, 19(17-18), 2611-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D. (2015). Notes on person-centred care: What it is and what it is not. Nordic Journal of Nursing Research, 35, 65-66. [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Fetherstonhaugh D., Nay R. (2010). Promoting a continuation of self and normality: Person-centred care as described by people with dementia, their family members and aged care staff. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 19, 2611-2618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Innes A. (2010). Measuring person-centered care: A critical comparative review of published tools. The Gerontologist, 50, 834-846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edvardsson D., Winblad B., Sandman P. O. (2008). Person-centred care of people with severe Alzheimer’s disease: Current status and ways forward. The Lancet Neurology, 7, 362-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio S., Pace D., Flinner J., Kallmyer B. (2018). The fundamentals of person-centered care for individuals with dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(Suppl. 1), S10-S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard J. (2013). Health sciences literature review made easy. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett. [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd E. (2001). Hong Kong Chinese daughters’ intergenerational caregiving obligations: A cultural model approach. Social Science & Medicine, 53, 1125-1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao H. Y., Liu Z., Xu L., Huang Y., Chi I. (2016). Knowledge, attitudes, and clinical practices for patients with dementia among mental health providers in China: City and town differences. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 37, 342-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T. (1993). Towards a theory of dementia care: The interpersonal process. Ageing & Society, 13, 51-67. [Google Scholar]

- Kitwood T., Bredin K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing & Society, 12, 269-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong S., Fang C., Lou V. (2017). Organizational capacities for “residential care homes for the elderly” to provide culturally appropriate end-of-life care for Chinese elders and their families. Journal of Aging Studies, 40, 1-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N., Zhang L., Du W., Pang L., Guo C., Chen G., Zheng X. (2015). Prevalence of dementia-associated disability among Chinese older adults: Results from a National Sample Survey. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 320-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou C., Jarrott E. (2013). Dementia and dementia care in Asia-Taiwanese experiences: Elders with dementia in two different adult day service (ADS) environments. Aging & Mental Health, 17, 942-951. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.788998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love K., Pinkowitz J. (2013). Person-centered care for people with dementia: A theoretical and conceptual framework. Generations, 37(3), 23-29. [Google Scholar]

- Mao P., Xiao D., Zhang M., Xie F., Feng H. (2016). Hunan Sheng Yanglao Jigou Chidai Zhaohu Danyuan Yirenweizhongxin de Zhaohu Xianzhuang Fenxi [Person-centered dementia care in eldercare institutions in Hunan Province]. Journal of Nursing Sciences, 31(21), 1-4. [Google Scholar]

- McCormack B., McCance T. (2006). Development of a framework for person-centred nursing. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56, 472-479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack B., McCance T. (2010). Person-centred nursing: Theory, models and methods. Oxford, UK: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan M. R., Davies S., Brown J., Keady J., Nolan J. (2004). Beyond “person-centred” care: A new vision for gerontological nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13, 45-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J., Yu F., Kolanowski A., Fick D. M., Loeb S. J., Hupcey J. E. (2007). Reframing person-centered nursing care for persons with dementia. Research and theory for nursing practice, 21(1), 57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M., Bryce R., Albanese E., Wimo A., Ribeiro W., Ferri C. P. (2013). The global prevalence of dementia: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 9(1), 63-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Røsvik J., Kirkevold M., Engedal K., Brooker D., Kirkevold Ø. (2011). A model for using the VIPS framework for person-centred care for persons with dementia in nursing homes: A qualitative evaluative study. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 6, 227-236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sereny M. (2011). Living arrangements of older adults in China: The interplay among preferences, realities, and health. Research on Aging, 33, 172-204. [Google Scholar]

- Shih F. (1996). Concepts related to Chinese patients’ perceptions of health, illness and person: Issues of conceptual clarity. International Emergency Nursing, 4, 208-215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y., Anderson R. A., Corazzini K. N., Wu B. (2014). Staff characteristics and care in Chinese nursing homes: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 1, 423-436. [Google Scholar]

- Wah J., Tao L. (2007). Dignity in long-term care for older persons: A Confucian perspective. The Journal of Medicine & Philosophy, 32, 465-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang J., Cao Y., Jia S., Wu B. (2016). Older residents’ perspectives of long-term care facilities in China. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 42(8), 34-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wang J., Cao Y., Jia S., Wu B. (2018). Perceived empowerment, social support, and quality of life among Chinese older residents in long-term care facilities. Journal of Aging and Health, 30, 1595-1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Xiao L. D., He G. P., De Bellis A. (2014). Family caregiver challenges in dementia care in a country with undeveloped dementia services. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70, 1369-1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Xiao L. D., Li X. (2018). Health professionals’ perceptions of developing dementia services in primary care settings in China: a qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 1-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xiao L. D., Luo Y., Xiao S. Y., Whitehead C., Davies O. (2018). Community health professionals’ dementia knowledge, attitudes and care approach: A cross-sectional survey in Changsha, China. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Xiao L.D., Ullah S., He G., Bellis A.D. (2017). Evaluation of a nurse-led dementia education and knowledge translation programme in primary care: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Nurse education today, 49, 1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A., Guerchet M., Ali G. C., Wu Y. T., Prina A. M., Winblad B., . . . Prince M. (2017). The worldwide costs of dementia 2015 and comparisons with 2010. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 13(1), 1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B., Amouyel P., Andrieu S., Ballard C., Brayne C., Brodaty H., . . . Fratiglioni L. (2016). Defeating Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias: A priority for European science and society. The Lancet Neurology, 15, 455-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Mao Z. F., Zhong R. (2009). Long-term care arrangements in rural China: Review of recent developments. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 10, 472-477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu L., Hsiao H. Y., Deng W., Chi I. (2018). Training needs for dementia care in China from the perspectives of mental health providers: Who, what, and how. International Psychogeriatrics, 30, 929-940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Xiao D., Mao P., Xia M., Zhang W., Feng H. (2018). Yirenweizhongxin de Yanglaojigou Zhaohuhuanjing Wenjuan [Research on reliability and validity of Person-Centered Climate Questionnaire-staff version in pension institution]. Chinese Nursing Research, 32, 878-882. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J., Wang J., Jiang Y., Han L., Liu X., Gao S., Hao Y. (2016). Yirenweizhongxin de Laonian Zhaohu Moshi Yanjiu Jinzhan [A review of person-centered care for the elderly]. Journal of Nursing Sciences, 31(19), 107-110. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. (2017). Weirao Yi Laorenweizhongxin zhaohu Linian Jinxing Sheji [Older adults-centered care design]. City & House, 2, 45-48. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X. B., Lou V. W. Q. (2012). Practice person-centred care for demented older adults in Hong Kong residential care facilities: A qualitative exploration. Asian Health Care Journal, 7, 14-19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X. B., Lou V. W. (2013). Person-centered care in Chinese residential care facilities: a preliminary measure. Aging & mental health, 17(8), 952-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong X. B., Lou V. W. Q. (2013). Person-centered care in Chinese residential care facilities: A preliminary measure. Aging & Mental Health, 17, 952-958. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.790925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]