Abstract

Introduction:

Prevalence of adult deformity surgery in the elderly individuals continues to increase. These patients have additional considerations for the spine surgeon during surgical planning. We perform an informative review of the spinal and geriatric literature to assess preoperative and intraoperative factors that impact surgical complication occurrences in this population.

Significance:

There is a need to understand surgical risk assessment and prevention in geriatric patients who undergo thoracolumbar adult deformity surgery in order to prevent complications.

Methods:

Searches of relevant biomedical databases were conducted by a medical librarian. Databases searched included MEDLINE, Web of Science, CINAHL, IPA, Cochrane, PQ Health and Medical, SocINDEX, and WHO’s Global Health Library. Search strategies utilized Medical Subject Headings plus text words for extensive coverage of scoliosis and surgical technique concepts.

Results:

Degenerative scoliosis affects 68% of the geriatric population, and the rate of surgical interventions for this pathology continues to increase. Complications following spinal deformity surgery in this patient population range from 37% to 62%. Factors that impact outcomes include age, comorbidities, blood loss, and bone quality. Using these data, we summarize multimodal risk prevention strategies that can be easily implemented by spine surgeons.

Conclusions:

After evaluation of the latest literature on the complications associated with adult deformity surgery in geriatric patients, comprehensive perioperative management is necessary for improved outcomes. Preoperative strategies include assessing physiological age via frailty score, nutritional status, bone quality, dementia/delirium risk, and social activity support. Intraoperative strategies include methods to reduce blood loss and procedural time. Postoperatively, development of a multidisciplinary team approach that encourages early ambulation, decreases opiate use, and ensures supportive discharge planning is imperative for better outcomes for this patient population.

Keywords: adult deformity, degenerative scoliosis, elderly, geriatric, surgical risk, risk assessment, risk prevention

Introduction

Adult degenerative scoliosis results from the asymmetric degeneration of intervertebral disks and facet joints that lead to spinal column malalignment/deformity.1,2 The prevalence of adult degenerative scoliosis increases with age.3,4 As the population’s life span increases, the world’s population of people older than 60 will triple in size by 2050.5 Therefore, this is a significant public health issue as degenerative scoliosis affects 68% of the elderly population.6 Given recent surgical advances and further understanding of the etiopathology on this condition, there has been a paradigm shift in treating qualifying elderly patients with surgical intervention rather than medical management.7-9 Surgical intervention for adult spinal deformity among patients older than 60 increased 3.4-fold from 2004 to 2011.10 Among the adult population, the rate of spinal deformity cases increased from 4.16 per 100 000 adults to 13.9 per 100 000 adults from 2001 to 2013.11 From 2003 to 2012, surgical management of adult deformity increased and surgical morbidity decreased in the elderly individuals.12

Surgical management of degenerative scoliosis involves decompression of the neural elements and fusion to realign the involved spinal segments. Oftentimes extensive multilevel spine surgery is required to achieve both coronal and sagittal alignment.13 Surgical risk assessment is critical to estimating postoperative complications that impact a wide range of factors from informed consent discussions to operative planning.14 Complication rates following adult deformity surgery can be up to 55%.15-17 The risks–benefits analysis required in evaluating elderly patients for deformity spinal surgery for the treatment of degenerative scoliosis is complex.

Adult degenerative scoliosis causes progressive disability and severely impacts quality of life more than other chronic conditions such as diabetes and congestive heart failure.18 Few studies have evaluated outcomes in cohorts of elderly patients with this condition who have undergone surgery. However, given the continual increase in the aging population, spine surgeons will continue to be challenged to deliver adequate care to the elderly population. In this review, we analyzed both the surgical and geriatric literature to allow spine surgeons’ tools to critically evaluate surgical risk and subsequently develop risk prevention strategies for elderly adult deformity patients.

Methods

An informative review of the literature was performed using biomedical databases across 4 vendor platforms and the World Health Organization’s Global Health Library website. MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process & Daily Updates plus International Pharmaceutical Abstracts were searched via the OVID platform. The EBSCO platform was utilized for searching the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature-CINAHL Complete, SocINDEX, as well as Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Methodology Register, and Cochrane Clinical Answers. ProQuest’s interface was used to search the PQ Health and Medical database. Science Citation Index and Social Sciences Citations Index were both researched via Web of Science.

The research team identified all pertinent concepts and consulted on specific terminology. Search strategies were piloted and refined based on team’s reviews of sample results. All search strategies were created by medical librarian coauthor (S.C.S.), and final strategies were run in early to mid-October 2018. Controlled vocabulary terms were combined with advanced text word search techniques including adjacency, nesting, and truncation for each main concept. Specific Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) utilized and exploded (to incorporate more specific headings under the MeSH terms) for concept 1 included: spinal curvatures, scoliosis, kyphosis, lordosis or spinal diseases specific to spine deformity, degeneration, and misalignment. The surgical subheading was used in some search strings. Concept 2 was surgical techniques that included MeSH headings: surgical decompression, arthrodesis, osteotomy, spinal fusion, bone screws, or pedicle screws. The third concept covered age-related risk factors and outcomes: age factors, Alzheimer disease, dementia, delirium, hemorrhage, surgical blood loss, failed back surgery syndrome, treatment failure, and treatment outcome are a few of the MeSH headings utilized. The main MEDLINE strategy was adapted to include appropriate controlled vocabulary headings and text word searching combinations as required for specific database platforms. All final strategies covered 1998 to 2018 and were limited to English language. Articles that focused on scoliosis of the cervical region were excluded at the search strategy level. All results were filtered for the elderly individuals (65 and older). Results were exported to EndNote X6 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicate records were removed. The final unique set of results was then sent to the team for analysis.

Predictors of Complications

In order to evaluate factors that determine surgical risk, we assessed predictors of complications following spine surgery for scoliosis in the elderly individuals. Few studies were available that included this cohort of patients. In an analysis of over 2000 geriatric patients (aged older than 80) who underwent lumbar surgery, factors associated with increased risk of complication and readmission include baseline functional status and the length and complexity of the surgical procedure. All lumbar spinal surgeries performed for the diagnoses of lumbar stenosis and spondylolisthesis were included; the diagnosis of scoliosis was not explicitly queried.19 Blood loss and history of a previous spine surgery were associated with morbidity in another study of patients older than 80 years who had lumbar degenerative spine surgery.20 However, it is very likely that a portion of patients from both of these studies were treated for degenerative scoliosis, but results of patients who underwent multilevel fusion were not separated from the larger cohort.

Age greater than 80 was associated with the highest risk of mortality in patients who underwent spinal fusion.21 Patients older than 60 who required 5 or more levels of fusion for spinal deformity correction had an overall complication rate of 37%. Increasing age and undergoing a pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO) were associated with increased complications. A patient older than 69 had 9 times the risk of a major complication than a patient younger than 69. Patients who underwent a PSO were 7 times more likely to have a major complication than those who did not.22 Pedicle subtraction osteotomy and vertebral column resection can significantly improve sagittal and coronal balance in the elderly individuals but can lead to serious complications.23 The fusion of multiple segments in the elderly individuals is also a risk factor for postoperative complications.24 Patients older than 75 years undergoing spinal deformity surgery that required fusion of 5 or more levels had perioperative complication risks of 62%. Hypertension was the most predictive comorbidity of perioperative complication in this cohort.25 Increasing age also directly correlates with the need for revision surgery in adults following index spinal deformity surgery.26,27 Preexisting anemia was an independent predictor of 30-day readmission in elderly spine patients who underwent deformity correction.28

Despite age itself being a risk factor for complications in many studies, some studies did not find a correlation between age and complications in patients undergoing deformity surgery.10,24,29-31 Thirty-day morbidity and mortality were similar between elderly patients undergoing combined anterior/posterior compared to those undergoing posterior alone for spinal deformity.32 Medicare patients older than 65 years of age were less likely to be reoperated or readmitted in comparison to Medicare patients younger than 65 years of age following lumbar spine surgery.33 However, although there was a more than 3-fold increase in the first decade of the 21st century among spinal deformity surgery among the elderly individuals, the in-hospital complication rate was stable between all age groups.10 Yoshida et al developed a scale to predict perioperative complications following spinal deformity surgery based on a retrospective analysis of 304 patients. Patients’ age, medication, and type of deformity were independent preoperative predictors of risk.34

Adult patients who require revision surgery have higher complication rates than patients undergoing primary scoliosis surgery. Adjacent segment disease is the most common cause for revision surgery.35,36 Interestingly, in Cho et al’s cohort, patients older than 60 years of age who underwent primary or revision scoliosis surgery had similar clinical outcome measures.37 However, age and number of levels fused were most predictive of extended hospital stay and intraoperative blood loss.38 These data indicate that chronological age alone is not the main determinant of risk. An informative assessment of multiple factors is needed in this patient population.

Surgical Risk Assessment

Age and Frailty

Advanced age carries an increased risk of surgical complications, but chronological age is not the same as physiological age. Rather than focusing on age, frailty, a geriatric syndrome characterized by decreased physiological reserve, has been found to be a better predictor of postoperative morbidity and mortality.39 Frailty has been useful in predicting poor surgical outcomes for patients from multiple specialties including general surgery, surgical oncology, vascular surgery, orthopedics, and urology.40,41 Frailty assessment can be done based on clinical judgment or administering a questionnaire. Five common clinical tools used to evaluate frailty are outlined in Table 1. Two of the frailty scales involve the use of clinical judgment to ascertain functional capability similar to a performance score. However, for surgeons without significant experience in geriatrics, clinical judgment tools may not be the most accurate for risk assessment. Certain frailty scales, such as the Edmonton frailty scale, assess overall health status, cognition, social support, medication use, nutrition, continence, and functional performance.49 These scales involve questionnaires and can be filled out prior to the clinical encounter.

Table 1.

Frailty Assessment Tools.

| Name | Grades of Frailty | Assessment Method | Pros/Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edmonton Frail Scale42 | 0- to 17-point scale (ranging from not frail to severe frailty) | Questionnaire |

|

| Clinical Frailty Scale34,43; CSHA Frailty Scale39 | 1- to 9-point scale (ranging from very fit to terminally ill); 1- to 7-point scale (ranging from very fit to severely frail) | Clinical judgment |

|

| The Fatigue, Resistance, Ambulation, Illness and Loss of weight (FRAIL) Index17 | 0- to 5-point scale (ranging from health status to frail) | Questionnaire |

|

| Groningen Frailty Indicator (GFI)33,45 | 0- to 15-point scale (ranging from normal to completely disabled) | Questionnaire |

|

| Tilburg Frailty Indicator47,48 | 0- to 15-point scale (ranging from normal to frail) | Questionnaire |

Recent studies have begun to evaluate how frailty assessment can be used in surgical spine patients. An analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) data for patients undergoing spine surgery from 2006 to 2010 demonstrated that the modified frailty index was associated with an increased risk of a life-threatening complication and death.43 In patients undergoing spine surgery for degenerative disease, frailty was predictive of major complication, reoperation, and mortality.46,50,51 For adult patients who had surgery for spinal deformity, frailty was also found to be a predictor for these same 3 outcomes.52 This clinical parameter should be integrated into the preoperative risk assessment. A frailty index that uses a panel of urine and blood tests is also available and is comparable to other clinical frailty indexes.53 This allows for another method of evaluation with potential for practical utility in a busy spine practice.

Nutritional Status

Nutritional status is another important parameter in the elderly adult deformity patient as it plays a major role in postoperative recovery and wound healing.54,55 Malnutrition predisposes patients to infection as well. The main reason for reoperation in adult spinal deformity surgery is infection.56 Malnutrition is an independent risk factor for infection and wound complications following posterior lumbar surgery.57 In elderly orthopedic patients, malnutrition was found to correlate with prolonged hospitalization, delayed mobilization, and mortality.58,59 In patients aged 65 to 84 years who underwent elective 1- or 2-level spine surgery, malnutrition was correlated with incidence of major complication and was a predictor of increased infection and wound dehiscence.60

Nutrition assessment can be done by asking the patient about recent weight loss, obtaining body mass index (BMI), and physical examination. Patient self-reported weight loss is often integrated into many frailty indexes.49 Formal screening tools for malnutrition include the subjective global assessment of nutritional status, the nutritional risk screening tool, and the Mini-Nutritional Assessment questionnaire.61 These evaluations may be cumbersome, with the average time to complete the Mini-Nutritional Assessment questionnaire of 10 to 15 minutes.62

The assessment of protein status via laboratory data is used as a surrogate method to evaluate nutrition. Serum albumin of 3.5 g/dL or less (ie, hypoalbuminemia) is an independent risk factor for mortality, complications, wound infection, and thromboembolic disease in adults who had spinal fusion.21 Low preoperative albumin level is also a risk factor for patients after elective spine surgery for degeneration and deformity.63 Prealbumin can also be used with a threshold value of 11 mg/dL. Patients with low (<11 mg/dL) perioperative prealbumin levels who underwent long fusion constructs (≥7 segments) were more likely to develop an infectious complication.64

Malnutrition is often the focus of surgical risk assessment, but obesity is a consideration as well. In one study, morbidly obese patients who undergo elective spine surgery have increased odds of complications, readmission, and reoperation.65 However, in patients with degenerative scoliosis who required multiple levels of fusion, obesity did not increase postoperative complications.66 A more recent evaluation of data from the National Neurosurgery Quality and Outcomes Database also did not find significant outcome differences between obese and nonobese patient undergoing lumbar surgery.67 These contrasting results may be secondary to body mass distribution. Increased subcutaneous fat thickness was a better indicator of surgical site infection risk than BMI.42,68 When thoracolumbar scoliosis surgery was done with a combined anterior/posterior approach, outcomes were worse in obese patients likely related to the technical difficulty in this cohort.29 This indicates that body habitus should be considered when choosing surgical approach. How obesity affects outcomes in elderly patients who require spinal deformity surgery is unknown at this time.

Bone Density

Bone density is an important factor in surgical planning, especially when multiple levels of fusion are required. The prevalence of osteoporosis is increased in the elderly population and can create further considerations to altering the surgical plan. Bone quality evaluation for patients requiring spine surgery is recommended especially in women older than 50 years.69 The most common method to measure bone mineral density is by dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). However, trabecular bone score can aid in evaluating bone microarchitecture providing information not available by DXA.70 Vitamin D measurements with a goal serum 25(OH) D concentration of >30 ng/mL can be integrated in bone quality assessment of spine surgery patients.71 In elderly spinal deformity patients who required a minimum of 5 fusion levels, poor bone quality was associated with early complications such as pedicle and compression fractures. Bone quality also was associated with late complications of pseudarthrosis, adjacent-level disease, and progressive kyphosis.72 Bone density and quality evaluation is therefore an important measure for spine surgeons to conduct preoperatively.

Dementia/Delirium Risk

The prevalence of delirium in the perioperative period is increased in the elderly population. Preexisting dementia is one of the main risk factors for developing delirium.73 Among older patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery, the prevalence of preoperative cognitive impairment was 38%.74 In elderly patients undergoing elective spine, risk factors for the development of delirium during postoperative hospitalization included prolonged anesthesia greater than 3 hours, greater blood loss, intraoperative hypotension, intraoperative hypercapnia, and polypharmacy.75-78 The development of delirium is an independent risk factor for readmission in elderly spine surgical patients.79 For patients aged 70 years and older, delirium was a risk for longer hospital stay, increased cost over the admission period, and less likelihood of discharge to home.80 Depression was independently predictive of postoperative delirium in spinal deformity patients.81

Delirium risk can be determined with the AWOL stratification and can be derived from nursing assessment data.82 The AWOL screen consists of age, ability to spell “world” backwards, orientation assessment, and nursing illness severity assessment.83 Evaluation of baseline cognitive dysfunction is imperative in this group of patients as well. Several tools to evaluate dementia/cognition are outlined in Table 2. Patients with dementia oftentimes have issues with capacity, and this impacts the ability to obtain informed consent.89 Assessment of social support and the caregiving environment can be incorporated into cognition workup as these factors are interrelated.

Table 2.

Dementia Assessment Tools.

| Name | Assessment Method | Pros/Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE)84 | Questionnaire |

|

| Mini COG85 | Three-part diagnostic test |

|

| General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG)9 | Two-stage method composed of cognitive assessment and informant questionnaire |

|

| Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT)67 | Questionnaire |

|

| Trail Making Test (TMT)35 | Clinical testing |

|

| Clock Drawing Test61,88 | Clinical testing |

|

Intraoperative Parameters

Many intraoperative parameters are associated with increased complication rates following spinal surgery. Extended operative time is a known factor correlating with postoperative complications in elderly patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery and patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis.19,90,91 In adult spinal deformity surgery, operative time was more predictive of surgical outcomes than operative complexity (ie, increased levels fused, presence of interbody fusions, osteotomies, and pelvic fixation).47 Procedural time in excess of 309 minutes was associated with increased complication development for patients with spinal arthrodesis analyzed from NSQIP between 2005 and 2010.21 Oftentimes operative time and the levels of fusion are correlated. For patients aged 80 years or older, operative time increased with the amount of instrumentation. Instrumentation was associated with blood loss and delirium risk.20 Fusion to the sacrum and osteotomies correlated have negative effects on recovery in the elderly population.92

Length of construct is a known factor associated with risk. Short fusion constructs (ie, 1 to 3 segments) for lumbar degenerative scoliosis can result in restoration of sagittal and coronal balance.87 Whether or not an invasive technique is needed to achieve deformity correction is decided by the primary surgeon. Certain maneuvers such as 3-column osteotomy for adult spinal deformity is associated with a higher reoperation rate than patients who undergo standard surgical management.23 These maneuvers may increase blood loss, which is another risk for complications as outlined previously.

Risk Prevention Strategies

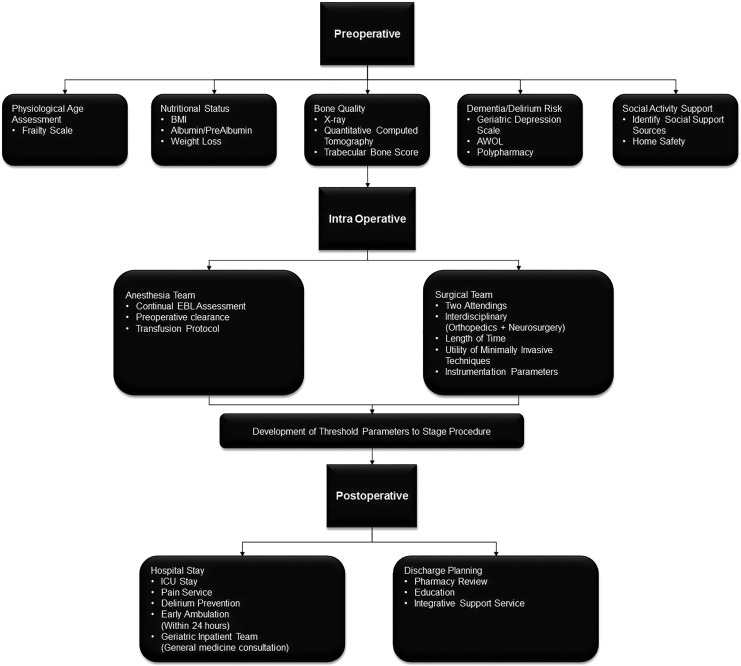

Decision-making for the planning of elderly adult deformity surgery is intricate. By understanding the risk factors for postoperative complications, spine surgeons can begin to alter their clinical practice. We summarize in Figure 1 preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative risk prevention strategies. In addition to standard preoperative screening, evaluation of frailty, nutrition, bone density, and cognition is important in the elderly adult deformity patient. The American College of Surgeons (ACS) has developed a surgical risk calculator based on data from the NSQIP.14 The ACS-NSQIP surgical risk calculator can be used for all specialties and in spine surgery underestimated complication occurrence.84 Risk prediction in elderly spine patients requires multimodal methods.

Figure 1.

Schematic of risk assessment and prevention strategies for adult spinal deformity patients during the perioperative period.

Intraoperative factors such as procedural time and blood loss can be directly affected by the surgeon. For spinal deformity surgery, multidisciplinary team initiatives can reduce perioperative complications. A multidisciplinary preoperative conference, dual attending surgeons, and a detailed protocol for coagulopathy/blood loss in the operating room are part of the Seattle spine team approach.48,93 The presence of dual attending surgeons can decrease operative time. Utilization of the anesthesia team to implement a transfusion protocol reduced perioperative blood loss and coagulopathy. Furthermore, some rigid deformities require both an anterior and a posterior fusion or vertebral body resection which is done with the aid of an approach surgeon.94 Coordination and communication is necessary for success of these large interdisciplinary surgical teams.

Another intraoperative factor is the use of minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS), which is becoming more widespread. In a comprehensive multicenter study, the use of MIS was associated with a reduction in construct length, blood loss, and length of stay. Despite reduction in construct length, deformity correction was achieved based on radiographic criterion.95 The rate of complications following adult spinal deformity surgery was lowest with minimally invasive techniques when compared to open or hybrid techniques.45 “Old-old” patients (>75 years of age) had a similar complication profile compared to younger patients when MIS was used for lumbar interbody fusion.96 A review of multiple studies demonstrated that rates of fusion and complications in the elderly individuals following MIS for deformity are acceptable.86,97,98

Besides the consideration of using MIS or traditional open techniques, the bone quality in elderly patients may warrant augmentation with polymethyl methacrylate or using longer screws with greater diameter.99 Changing the pedicle screw trajectory can also impact the screw–bone interface.44 The cortical bone trajectory for pedicle screws in osteoporotic bone provides better screw purchase than the traditional screw and has been used in elderly patients for this purpose.85,100 While these construct parameters are determined by the surgeon, interdisciplinary communication between the surgical and anesthesia teams is necessary. Determination of threshold parameters to stop surgery and potentially finish in a staged fashion should be communicated beforehand.

Postoperatively, multidisciplinary care in the elderly improves outcomes. Interventions to encourage early ambulation may also lead to decreased length of stay, less perioperative complications, and improved functional outcomes.88 Given the age-related changes in physiology and pharmacokinetics, pain management is particularly challenging in the elderly surgical patient. Adequate pain management can lead to earlier ambulation, earlier return of mental capacity, and shorter hospitalization. Multimodal adjuvant analgesia can help these patients manage pain.101 However, caution must be used in the elderly individuals as polypharmacy predisposes to delirium. As previously discussed, delirium is a significant risk factor for postoperative complications. A multidisciplinary postoperative care team can help reduce delirium.75 Spine surgeons should consider routine consultation of pain medicine and geriatricians for elderly adult deformity patients. For geriatric patients with hip fractures, discharge planning initiatives that maximize social support, ensure a safe discharge environment, and discuss advance care planning can help enhance quality of life.102 The integration of a geriatrician on the multidisciplinary team doing the in-hospital stay significantly decreases the use of critical care services following deformity surgery.103 Increasing age and critical care services are independent predictors of readmission for altered mental status for spinal deformity patients.104

Conclusion

Elderly adult deformity patients have a greater prevalence of complicated outcomes which include longer hospitalization, reoperation, and mortality. As the population continues to age, the frequency of surgery for these patients will increase. Surgical risk assessment and prevention in these patients can lead to improved outcomes and significantly impact surgical decision-making and patient counseling. In order to improve patient outcomes, assessing preoperative measures (ie, bone quality, dementia/delirium risk, and so on), intraoperative strategies (ie, reducing blood loss, proper communication between surgical and anesthesia teams, etc), and postoperative recovery (ie, early ambulation, pharmacy review, etc) can give patients with a spinal deformity better outcomes. By combining management principals from spine surgery and geriatric medicine, multidisciplinary perioperative strategies can be integrated into the spine surgeon’s armamentarium to reduce risk.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Kevin Thomas  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5716-9606

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5716-9606

References

- 1. Berven SH, Lowe T. The scoliosis research society classification for adult spinal deformity. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2007;18(2):207–213. doi:10.1016/j.nec.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wong E, Altaf F, Oh LJ, Gray RJ. Adult degenerative lumbar scoliosis. Orthopedics. 2017;40(6):e930–e939. doi:10.3928/01477447-20170606-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kebaish KM, Neubauer PR, Voros GD, Khoshnevisan MA, Skolasky RL. Scoliosis in adults aged forty years and older: prevalence and relationship to age, race, and gender. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(9):731–736. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e9f120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Urrutia J, Diaz-Ledezma C, Espinosa J, Berven SH. Lumbar scoliosis in postmenopausal women. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(9):737–740. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181db7456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reher DS. Baby booms, busts, and population ageing in the developed world. Popul Stud (NY). 2015;69(suppl 1):S57–S68. doi:10.1080/00324728.2014.963421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Falakassa J, Hu SS. Adult lumbar scoliosis: nonsurgical versus surgical management. Instr Course Lect. 2017;66:353–360. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28594511. Accessed July 31, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kotwal S, Pumberger M, Hughes A, Girardi F. Degenerative scoliosis: a review. HSS J. 2011;7(3):257–264. doi:10.1007/s11420-011-9204-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cho KJ, Kim YT, Shin SH, Suk SI. Surgical treatment of adult degenerative scoliosis. Asian Spine J. 2014;8(3):371–381. doi:10.4184/asj.2014.8.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Martin B, Mirza SK, Spina N, Spiker WR, Lawrence B, Brodke DS. Trends in lumbar fusion procedure rates and associated hospital costs for degenerative spinal diseases in the United States, 2004-2015. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;02:2 http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medp&AN=30074971 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+Epub+Ahead+of+Print+%3COctober+03%2C+2018%3E&genre=article. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sing DC, Berven SH, Burch S, Metz LN. Increase in spinal deformity surgery in patients age 60 and older is not associated with increased complications. Spine J. 2017;17(5):627–635. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zygourakis CC, Liu CY, Keefe M, et al. Analysis of national rates, cost, and sources of cost variation in adult spinal deformity. Neurosurgery. 2018;82:378–387. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyx218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Passias PG, Poorman GW, Jalai CM, et al. Morbidity of adult spinal deformity surgery in elderly has declined over time. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42:E978–E982. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=28059982 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3CJanuary+Week+1+2018+to+September+Week+4+2018%3E&genre=a. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta MC. Degenerative scoliosis. Options for surgical management. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(2):269–279. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12914267. Accessed July 29, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bilimoria KY, Liu Y, Paruch JL, et al. Development and evaluation of the universal ACS NSQIP surgical risk calculator: a decision aid and informed consent tool for patients and surgeons. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(5):833–842.e3. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.07.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sciubba DM, Yurter A, Smith JS, et al. A comprehensive review of complication rates after surgery for adult deformity: a reference for informed consent. Spine Deform. 2015;3(6):575–594. doi:10.1016/j.jspd.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zimmerman RM, Mohamed AS, Skolasky RL, Robinson MD, Kebaish KM. Functional outcomes and complications after primary spinal surgery for scoliosis in adults aged forty years or older a prospective study with minimum two-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35:1861–1866. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181e57827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Iyer S, Klineberg EO, Zebala LP, et al. Dural tears in adult deformity surgery: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Glob Spine J. 2018;8:25–31. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=prem&AN=29456912 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%2528R%2529+In-Process+%2526+Other+Non-Indexed+Citations+%253COctober+03%252. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pellisé F, Vila-Casademunt A, Ferrer M, et al. Impact on health related quality of life of adult spinal deformity (ASD) compared with other chronic conditions. Eur Spine J. 2015;24(1):3–11. doi:10.1007/s00586-014-3542 -1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Saleh A, Thirukumaran C, Mesfin A, Molinari RW. Complications and readmission after lumbar spine surgery in elderly patients: an analysis of 2,320 patients. Spine J. 2017;17(8):1106–1112. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2017.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Balabaud L, Pitel S, Caux I, et al. Lumbar spine surgery in patients 80 years of age or older: morbidity and mortality. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2015;25(S1):205–212. doi:10.1007/s00590-014-1556-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schoenfeld AJ, Carey PA, Cleveland AW, Bader JO, Bono CM. Patient factors, comorbidities, and surgical characteristics that increase mortality and complication risk after spinal arthrodesis: a prognostic study based on 5,887 patients. Spine J. 2013;13(10):1171–1179. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2013.02.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daubs MD, Lenke LG, Cheh G, Stobbs G, Bridwell KH. Adult spinal deformity surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(20):2238–2244. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31814cf24a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hassanzadeh H, Jain A, El Dafrawy MH, et al. Three-column osteotomies in the treatment of spinal deformity in adult patients 60 years old and older. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(9):726–731. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31827c2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Drazin D, Shirzadi A, Rosner J, et al. Complications and outcomes after spinal deformity surgery in the elderly: review of the existing literature and future directions. Neurosurg Focus. 2011;31(4):E3 doi:10.3171/2011.7.FOCUS11145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Acosta FL, Jr, McClendon J, Jr, O’Shaughnessy BA, et al. Morbidity and mortality after spinal deformity surgery in patients 75 years and older: complications and predictive factors. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011;15:667–674. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med7&AN=21888481 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2011+to+2013%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:21888481&id=doi:1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhu F, Bao H, Liu Z, et al. Unanticipated revision surgery in adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39:B36–B44. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shaw R, Skovrlj B, Cho SK. Association between age and complications in adult scoliosis surgery: an analysis of the scoliosis research society morbidity and mortality database. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41:508–514. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med8&AN=26693670 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2014+to+2017%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:26693670&id=doi:1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy A, Vuong V, et al. Patient history of anemia is an independent predictor of 30-day readmission in elderly (>= 60 years old) spine deformity patients after elective spinal fusion. J Neurosurg. 2018;128:18. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yagi M, Patel R, Boachie-Adjei O. Complications and unfavorable clinical outcomes in obese and overweight patients treated for adult lumbar or thoracolumbar scoliosis with combined anterior/posterior surgery. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2015;28(6):E368–E376. doi:10.1097/BSD.0b013e3182999526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Acosta FL, Cloyd JM, Aryan HE, Ames CP. Perioperative complications and clinical outcomes of multilevel circumferential lumbar spinal fusion in the elderly. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:69–73. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med6&AN=19019682 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2008+to+2010%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:19019682&id=doi:1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Worley N, Marascalchi B, Jalai CM, et al. Predictors of inpatient morbidity and mortality in adult spinal deformity surgery. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:819–827. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med8&AN=26155895 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2014+to+2017%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:26155895&id=doi:1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yue JK, Sing DC, Sharma S, et al. Spine deformity surgery in the elderly: risk factors and 30-day outcomes are comparable in posterior versus combined approaches. Neurol Res. 2017;39:1066–1072. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=28925332 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3CJanuary+Week+1+2018+to+September+Week+4+2018%3E&genre=a. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wadhwa RK, Ohya J, Vogel TD, et al. Risk factors for 30-day reoperation and 3-month readmission: analysis from the quality and outcomes Database lumbar spine registry. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(2):131–136. doi:10.3171/2016.12.SPINE16714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yoshida G, Hasegawa T, Yamato Y, et al. Predicting perioperative complications in adult spinal deformity surgery using a simple sliding scale. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43:562–570. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=mesx&AN=28885286 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+Daily+Update+%3COctober+03%2C+2018%3E&genre=article&id=pmi. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Zhong ZM, Deviren V, Tay B, Burch S, Berven SH. Adjacent segment disease after instrumented fusion for adult lumbar spondylolisthesis: incidence and risk factors. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2017;156:29–34. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=28288396 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3CJanuary+Week+1+2018+to+September+Week+4+2018%3E&genre=a. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Simon MJK, Halm HFH, Quante M. Perioperative complications after surgical treatment in degenerative adult de novo scoliosis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19:10 http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=29316936 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3CJanuary+Week+1+2018+to+September+Week+4+2018%3E&genre=a. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Cho SK, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG, et al. Comparative analysis of clinical outcome and complications in primary versus revision adult scoliosis surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(5):393–401. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31821f0126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zheng F, Cammisa FP, Jr, Sandhu HS, Girardi FP, Khan SN. Factors predicting hospital stay, operative time, blood loss, and transfusion in patients undergoing revision posterior lumbar spine decompression, fusion, and segmental instrumentation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:818–824. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med4&AN=11935103 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C1996+to+2003%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:11935103&id=doi:&. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Buigues C, Juarros-Folgado P, Fernández-Garrido J, Navarro-Martínez R, Cauli O. Frailty syndrome and pre-operative risk evaluation: a systematic review. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2015;61(3):309–321. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lin H-S, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: a systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):157 doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0329-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Revenig LM, Canter DJ, Taylor MD, et al. Too frail for surgery? Initial results of a large multidisciplinary prospective study examining preoperative variables predictive of poor surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;217(4):665–670.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2013.06.012 Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee JJ, Odeh KI, Holcombe SA, et al. Fat thickness as a risk factor for infection in lumbar spine surgery. Orthopedics. 2016;39(6):e1124–e1128. doi:10.3928/01477447-20160819-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ali R, Schwalb JM, Nerenz DR, Antoine HJ, Rubinfeld I. Use of the modified frailty index to predict 30-day morbidity and mortality from spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2016;25(4):537–541. doi:10.3171/2015.10.SPINE14582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Santoni BG, Hynes RA, McGilvray KC, et al. Cortical bone trajectory for lumbar pedicle screws. Spine J. 2009;9(5):366–373. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1529943008007213. Accessed November 8, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Uribe JS, Deukmedjian AR, Mummaneni PV, et al. Complications in adult spinal deformity surgery: an analysis of minimally invasive, hybrid, and open surgical techniques. Neurosurg Focus. 2014;36:E15 http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med8&AN=24785480 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2014+to+2017%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:24785480&id=doi:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Miller EK, Neuman BJ, Jain A, et al. An assessment of frailty as a tool for risk stratification in adult spinal deformity surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2017;43(6):E3 doi:10.3171/2017.10.focus17472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Samuel AM, Fu MC, Anandasivam NS, et al. After posterior fusions for adult spinal deformity, operative time is more predictive of perioperative morbidity, rather than surgical invasiveness. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(24):1880–1887. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sethi RK, Pong RP, Leveque JC, Dean TC, Olivar SJ, Rupp SM. The seattle spine team approach to adult deformity surgery: a systems-based approach to perioperative care and subsequent reduction in perioperative complication rates. Spine Deform. 2014;2(2):95–103. doi:10.1016/j.jspd.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Perna S, Francis MD, Bologna C, et al. Performance of edmonton frail scale on frailty assessment: its association with multi-dimensional geriatric conditions assessed with specific screening tools. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):2 doi:10.1186/s12877-016-0382-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flexman AM, Charest-Morin R, Stobart L, Street J, Ryerson CJ. Frailty and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spine disease. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1315–1323. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2016.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kessler RA, Rafael De la Garza R, Purvis TE, et al. Impact of frailty on complications in patients with thoracic and thoracolumbar spinal fracture. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2018;169:161–165. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2018.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Leven DM, Lee NJ, Kothari P, et al. Frailty index is a significant predictor of complications and mortality after surgery for adult spinal deformity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(23):E1394–E1401. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ritt M, Jäger J, Ritt J, Sieber C, Gaßmann K. Operationalizing a frailty index using routine blood and urine tests. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:1029–1040. doi:10.2147/CIA.S131987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Fearon KCH, Luff R. The nutritional management of surgical patients: enhanced recovery after surgery. Proc Nutr Soc. 2003;62(04):807–811. doi:10.1079/PNS2003299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Williams JZ, Barbul A. Nutrition and wound healing. Surg Clin North Am. 2003;83(3):571–596. doi:10.1016/S0039-6109(02)00193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mok JM, Cloyd JM, Bradford DS, et al. Reoperation after primary fusion for adult spinal deformity: rate, reason, and timing. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(8):832–839. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819f2080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Bohl DD, Shen MR, Mayo BC, et al. Malnutrition predicts infectious and wound complications following posterior lumbar spinal fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(21):1693–1699. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chu CS, Liang CK, Chou MY, Lu T, Lin YT, Chu CL. Mini-Nutritional Assessment Short-Form as a useful method of predicting poor 1-year outcome in elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(12):2361–2368. doi:10.1111/ggi.13075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ihle C, Freude T, Bahrs C, et al. Malnutrition—an underestimated factor in the inpatient treatment of traumatology and orthopedic patients. Injury. 2017;48(3):628–636. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Puvanesarajah V, Jain A, Kebaish K, et al. Poor nutrition status and lumbar spine fusion surgery in the elderly. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42(13):979–983. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Giridhar VU. Role of nutrition in oral and maxillofacial surgery patients. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2016;7(1):3–9. doi:10.4103/0975-5950.196146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Guigoz Y. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) review of the literature—what does it tell us? J Nutr Health Aging. 2006;10(6):466–485; discussion 485-487 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17183419. Accessed August 1, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Adogwa O, Martin JR, Huang K, et al. Preoperative serum albumin level as a predictor of postoperative complication after spine fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(18):1513–1519. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Guan J, Holland CM, Schmidt MH, Dailey AT, Mahan MA, Bisson EF. Association of low perioperative prealbumin level and surgical complications in long-segment spinal fusion patients: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2017;39:135–140. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Seicean A, Alan N, Seicean S, et al. Impact of increased body mass index on outcomes of elective spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(18):1520–1530. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fu L, Chang MS, Crandall DG, Revella J. Does obesity affect surgical outcomes in degenerative scoliosis? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2014;39(24):2049–2055. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Onyekwelu I, Glassman SD, Asher AL, Shaffrey CI, Mummaneni P V, Carreon LY. Impact of obesity on complications and outcomes: a comparison of fusion and nonfusion lumbar spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;26(2):158–162. doi:10.3171/2016.7.SPINE16448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mehta AI, Babu R, Karikari IO, et al. 2012 Young investigator award winner. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012;37(19):1652–1656. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e318241b186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chin DK, Park JY, Yoon YS, et al. Prevalence of osteoporosis in patients requiring spine surgery: incidence and significance of osteoporosis in spine disease. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18(9):1219–1224. doi:10.1007/s00198-007-0370-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Shevroja E, Lamy O, Kohlmeier L, Koromani F, Rivadeneira F, Hans D. Use of Trabecular Bone Score (TBS) as a complementary approach to dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for fracture risk assessment in clinical practice. J Clin Densitom. 2017;20(3):334–345. doi:10.1016/j.jocd.2017.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Rodriguez WJ, Gromelski J. Vitamin D status and spine surgery outcomes. ISRN Orthop. 2013;2013:471695 doi:10.1155/2013/471695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. DeWald CJ, Stanley T. Instrumentation-related complications of multilevel fusions for adult spinal deformity patients over age 65. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(suppl):S144–S151. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000236893.65878.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Bellelli G, Morandi A, Trabucchi M, et al. Italian intersociety consensus on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of delirium in hospitalized older persons. Intern Emerg Med. 2018;13(1):113–121. doi:10.1007/s11739-017-1705-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Lee YS, Kim YB, Lee SH, Park YS, Park SW. The prevalence of undiagnosed presurgical cognitive impairment and its postsurgical clinical impact in older patients undergoing lumbar spine surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2016;59(3):287 doi:10.3340/jkns.2016.59.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Nazemi AK, Gowd AK, Carmouche JJ, Kates SL, Albert TJ, Behrend CJ. Prevention and management of postoperative delirium in elderly patients following elective spinal surgery. Clin spine Surg. 2017;30(3):112–119. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Jiang X, Chen D, Lou Y, Li Z. Risk factors for postoperative delirium after spine surgery in middle- and old-aged patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2016;29(5):1039–1044. doi:10.1007/s40520-016-0640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Seo JS, Park SW, Lee YS, Chung C, Kim YB. Risk factors for delirium after spine surgery in elderly patients. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2014;56(1):28–33. doi:10.3340/jkns.2014.56.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Shi C, Yang C, Gao R, Yuan W. Risk factors for delirium after spinal surgery: a meta-analysis. World Neurosurg. 2015;84(5):1466–1472. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Elsamadicy AA, Wang TY, Back AG, et al. Post-operative delirium is an independent predictor of 30-day hospital readmission after spine surgery in the elderly (≥65 years old): a study of 453 consecutive elderly spine surgery patients. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;41:128–131. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2017.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Brown CH, LaFlam A, Max L, et al. Delirium after spine surgery in older adults: incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(10):2101–2108. doi:10.1111/jgs.14434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Lydon E, et al. Depression as an independent predictor of postoperative delirium in spine deformity patients undergoing elective spine surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(2):209–214. doi:10.3171/2017.4.SPINE161012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Brown EG, Josephson SA, Anderson N, Reid M, Lee M, Douglas VC. Predicting inpatient delirium: the AWOL delirium risk-stratification score in clinical practice. Geriatr Nurs. 2017;38(6):567–572. doi:10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Douglas VC, Hessler CS, Dhaliwal G, et al. The AWOL tool: derivation and validation of a delirium prediction rule. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(9):493–499. doi:10.1002/jhm.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Veeravagu A, Li A, Swinney C, et al. Predicting complication risk in spine surgery: a prospective analysis of a novel risk assessment tool. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;27(1):81–91. doi:10.3171/2016.12.SPINE16969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ueno M, Imura T, Inoue G, Takaso M. Posterior corrective fusion using a double-trajectory technique (cortical bone trajectory combined with traditional trajectory) for degenerative lumbar scoliosis with osteoporosis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19(5):600–607. doi:10.3171/2013.7.SPINE13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Shamji MF, Goldstein CL, Wang M, Uribe JS, Fehlings MG. Minimally invasive spinal surgery in the elderly. Neurosurgery. 2015;77:S108–S115. doi:10.1227/NEU.0000000000000941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Faldini C, Di Martino A, Borghi R, Perna F, Toscano A, Traina F. Long vs. short fusions for adult lumbar degenerative scoliosis: does balance matters? Eur Spine J. 2015;24(S7):887–892. doi:10.1007/s00586-015-4266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Fialkoff J, Cheng J, Karikari IO, Bagley C. Early ambulation decreases length of hospital stay, perioperative complications and improves functional outcomes in elderly patients undergoing surgery for correction of adult degenerative scoliosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2017;42:1420–1425. doi:10.1097/brs.0000000000002189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Loughlin D, Brown M. Improving surgical outcomes for people with dementia. Nurs Stand. 2015;29(38):50–58. doi:10.7748/ns.29.38.50.e9925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Tang H, Zhu J, Ji F, Wang S, Xie Y, Fei H. Risk factors for postoperative complication after spinal fusion and instrumentation in degenerative lumbar scoliosis patients. J Orthop Surg Res. 2014;9(1):15 doi:10.1186/1749-799X-9-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wang H, Zhang ZP, Qiu GX, Zhang JG, Shen JX. Risk factors of perioperative complications for posterior spinal fusion in degenerative scoliosis patients: a retrospective study. Bmc Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):242 doi:10.1186/s12891-018-2148-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Lin T, Meng YC, Li TB, Jiang H, Gao R, Zhou XH. predictors of postoperative recovery based on health-related quality of life in patients after degenerative lumbar scoliosis surgery. World Neurosurg. 2018;109: E539–E545. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Sethi R, Buchlak QD, Yanamadala V, et al. A systematic multidisciplinary initiative for reducing the risk of complications in adult scoliosis surgery. J Neurosurg Spine. 2017;26(6):744–750. doi:10.3171/2016.11.SPINE16537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhou CG, Liu LM, Song YM, Feng GJ, Yang X, Wang L. Comparison of anterior and posterior vertebral column resection versus anterior and posterior spinal fusion for severe and rigid scoliosis. Spine J. 2018;18:948–953. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Uribe JS, Beckman J, Mummaneni PV, et al. Does MIS surgery allow for shorter constructs in the surgical treatment of adult spinal deformity? Neurosurgery. 2017;80(3):489–497. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyw072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Nikhil NJ, Lim WAJ, Yeo W, Yue WM. Elderly patients achieving clinical and radiological outcomes comparable with those of younger patients following minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Asian Spine J. 2017;11(2):230 doi:10.4184/asj.2017.11.2.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Park P, Okonkwo DO, Nguyen S, et al. Can a minimal clinically important difference be achieved in elderly patients with adult spinal deformity who undergo minimally invasive spinal surgery? World Neurosurg. 2016;86:168–172. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2015.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Barbagallo GMV, Raudino G, Visocchi M, et al. Restoration of thoracolumbar spine stability and alignment in elderly patients using minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS). A safe and feasible option in degenerative and traumatic spine diseases. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2017;124:69–74. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=med8&AN=28120055 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3C2014+to+2017%3E&genre=article&id=pmid:28120055&id=doi:1. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Park SB, Chung CK. Strategies of spinal fusion on osteoporotic spine. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;49(6):317–322. doi:10.3340/jkns.2011.49.6.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Mai HT, Mitchell SM, Hashmi SZ, Jenkins TJ, Patel AA, Hsu WK. Differences in bone mineral density of fixation points between lumbar cortical and traditional pedicle screws. Spine J. 2016;16(7):835–841. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2015.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. McKeown JL. pain management issues for the geriatric surgical patient. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33(3):563–576. doi:10.1016/j.anclin.2015.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Bernstein J, Weintraub S, Hume E, Neuman MD, Kates SL, Ahn J. The new APGAR SCORE. J Bone Jt Surg. 2017;99(14):e77 doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.01149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Adogwa O, Elsamadicy AA, Sergesketter AR, et al. Interdisciplinary care model independently decreases use of critical care services after corrective surgery for adult degenerative scoliosis. World Neurosurg. 2018;111:e845–e849. http://libproxy.uams.edu/login?url=http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&CSC=Y&NEWS=N&PAGE=fulltext&D=medl&AN=29317368 http://BD4UZ2KJ6Y.search.serialssolutions.com/?sid=OVID:Ovid+MEDLINE%28R%29+%3CJanuary+Week+1+2018+to+September+Week+4+2018%3E&genre=a. Accessed January 1, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Elsamadicy AA, Adogwa O, Reddy GB, et al. Risk factors and independent predictors of 30-day readmission for altered mental status after elective spine surgery for spine deformity: a single-institutional study of 1090 patients. World Neurosurg. 2017;101:270–274. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2017.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]