Summary

Carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4), a member of the metallo‐carboxypeptidase family, is overexpressed in liver cancer and is associated with cancer progression. The role of CPA4 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains unclear. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the relevance of CPA4 to the proliferation and expression of stem cell characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Western blot analysis showed high CPA4 expression in the liver cancer cell line Bel7402 and low expression in HepG2 cells. Knock‐down of CPA4 decreased cancer cell proliferation as detected by MTT and clone formation assays. The serum‐free culture system revealed that downregulated CPA4 suppressed the sphere formation capacities of tumour cells. However, upregulated CPA4 increased the proliferation and sphere formation capacity. In addition, the protein expression of CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 also increased in cells with upregulated CPA4. In vivo, the overexpression of CPA4 in tumour cells that were subcutaneously injected into nude mice markedly increased the growth of the tumours. These data suggest that CPA4 expression leads to poor prognoses by regulating tumour proliferation and the expression of stem cell characteristics and may therefore serve as a potential therapeutic target of HCC.

Keywords: cancer stem cell, carboxypeptidase A4, hepatocellular carcinoma, proliferation

1. INTRODUCTION

Liver cancer is one of the most common malignant tumours and causes of death worldwide.1 Although great improvements have been made in the treatment of liver cancer, the 5‐year survival rates still need to be improved. The activation of multiple signalling pathways stimulates proliferation; cancer stem cell‐like properties, which lead to poor prognoses for liver cancer patients, are considered key factors for tumour progression.2, 3 Therefore, it is necessary to explore new molecular mechanisms of liver cancer progression that can be potential therapeutic targets for therapy.

Carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4) belongs to the Zn‐containing metallo‐carboxypeptidase family.4 CPA4 catalyses the release of carboxy‐terminal amino acids and is synthesized as zymogens that are activated by proteolytic cleavage to regulate inflammation and facilitate cancer progression.5 Studies have reported that CPA4 is a strong candidate gene for prostate cancer aggressiveness.6 CPA4 was significantly elevated in non‐small‐cell lung cancer tissues and was closely associated with tumour progression and poor prognosis.7, 8, 9, 10 In liver cancer, elevated levels of CPA4 were significantly correlated with high cancer grade, advanced stage and poor prognosis. There was also a significant positive correlation between the aberrant elevation of CPA4 and the overexpression of stem cell markers, including CD90, AFP and CD34.11 However, all of these studies mainly investigated cancer tissues by immunohistochemistry. The role of CPA4 in tumour progression requires further identification.

In this study, the functions of CPA4 in regulating tumour cell proliferation and metastasis in vitro and in vivo were investigated in two liver cancer cell lines to confirm the important role of CPA4 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) progression.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Cell lines and transfections

The HCC cell lines HepG2 and Bel7402 used in this study were purchased from the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, School of Basic Medicine, and Peking Union Medical College). The cells were cultured at 37°C in 5% CO2 and propagated in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Gibco) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen).

Carboxypeptidase A4 was downregulated by transfection with a CPA4 shRNA plasmid (catalogue no. HSH059037‐LVRH1GP; GeneCopoeia, USA) in HepG2 cells to establish HepG2‐shCPA4 cells and upregulated by transfection with a CPA4 cDNA plasmid (catalogue no. EX‐U0805‐Lv105; GeneCopoeia) in Bel7402 cells to establish Bel7402‐CPA4. The cell lines were transfected by following the protocol for the Lenti‐Pac™ HIV expression kit (catalogue no. HPK‐LvTR‐20; GeneCopoeia).

2.2. Ethical approval

All animal experiments were approved by the Tianjin Medical University Ethical and Welfare Committee (Approval No.TMUaMEC2017056). All of the experimental protocols were conducted in accordance with the Tianjin Medical University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

2.3. Antibodies and reagents

The primary antibodies for this study are as follows: rabbit polyclonal anti‐carboxypeptidase A4 (1:500; ab81543), anti‐CD133 (1:200; ab16518) and anti‐CD44 (1:800; ab157107) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA); mouse monoclonal anti‐ALDH1 (1:200; sc‐166362) was purchased from Invitrogen (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Oregon, USA).

2.4. Western blot analysis

Cell lysate protein was resolved by 10% SDS‐PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. The PVDF membranes were blocked with 5% non‐fat milk and incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C, washed in TBS, incubated with goat anti‐mouse or goat anti‐rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)‐conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and then visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Amersham Pharmacia) on an autoradiography film (Blue X‐Ray Film; Phoenix Research, Candler, NC, USA). β‐actin (ab1801; Abcam) was used as the internal control.

2.5. Cell proliferation assay

Cell suspensions were prepared at a density of 5 × 103 cells/mL in 96‐well plates, and the volume of each well was 100 μL. After culturing for 24, 48 and 72 hours, 10 μL MTT (5 mg/mL; Sigma‐Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) solution was added to each well. After 4 hours of incubation at 37°C, 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide was used to dissolve the purple crystals by shaking for 10 minutes. The optical density was determined at 490 nm on a Spectra MaxM2 (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). A control well was set (only medium, no cells). The OD value of the control well was 100%, and the cell proliferation rate was the OD value of the cancer cell well/OD value of the control well.

2.6. Cell colony formation assay

In the clone formation assay, 100 cells were seeded into each well of a 6‐well plate. After 5 days of culture, the cell clones were fixed with methanol and stained with 0.5% crystal violet. The number of clones was counted under the microscope.

2.7. Sphere formation assay for assessing stem cell characteristics

The sphere formation ability of the cells was evaluated using a serum‐free culture system. Cells were digested and suspended in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/F12 (1:1; Gibco) without FBS, and 104 cells were seeded into ultra‐low attachment culture dishes (no. 3261; Corning, NY, USA). Each dish was supplemented with 2% B27 (Gibco), 0.5% epidermal growth factor (EGF; PeproTech) and 0.5% basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; PeproTech). The culture medium with additional growth factors was replaced every three days. The tumour spheres were observed under a microscope and counted after nine days of culture.

2.8. Immunofluorescence studies

Cells were grown in a monolayer on poly‐D‐lysine‐coated glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 37°C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100/PBS for 15 minutes at room temperature, and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibody. For the spheres, intact tertiary spheres were plated directly onto poly‐D‐lysine‐coated glass coverslips, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at 37°C, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X‐100/PBS for 30 minutes at room temperature, and incubated overnight with the primary antibodies. FITC‐conjugated rabbit anti‐mouse IgG (Dako) was used as the secondary antibody. The cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and the images were recorded on a Leica TCS SP2 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany).

2.9. Tumour xenograft model in nude mice

For the in vivo xenograft model, a total of 12 male BALB/c nude mice (4 weeks old; purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience, Beijing, China) were divided into two groups (6 mice for each group); a total of 5 × 106 Bel7402 cells or stably transfected Bel7402‐CPA4 cells were suspended in 0.1 mL serum‐free DMEM and subcutaneously injected into the upper right flank region of the mice. The tumour volume was monitored weekly using digital callipers and calculated as follows: volume = (length [mm] × width2 [mm])/2. The mice were sacrificed after 4 weeks. The tumour samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin, and then cut into 4‐μm‐thick sections for immunohistochemistry staining.

2.10. Immunohistochemistry

The paraffin‐embedded xenograft sections were deparaffinized by sequential washing with xylene, graded ethanol and phosphate‐buffered saline. Antigen retrieval was accomplished through heat retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked using 3% hydrogen peroxide (in fresh methanol) for 15 minutes at room temperature. Then, the tissue sections were stained with the primary antibodies. HRP‐labelled goat anti‐mouse/rabbit IgG (Dako EnVision Plus System) was used as the secondary antibody. Positive staining was visualized with diaminobenzidine. Finally, all of the sections were counterstained with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted.

2.11. Statistical analysis

spss 17.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. The data are presented as the means ± SD. Student's t tests were used to compare the differences between the two groups. Statistical significance was considered as P‐value ≤ 0.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. CPA4 induces HCC cell proliferation

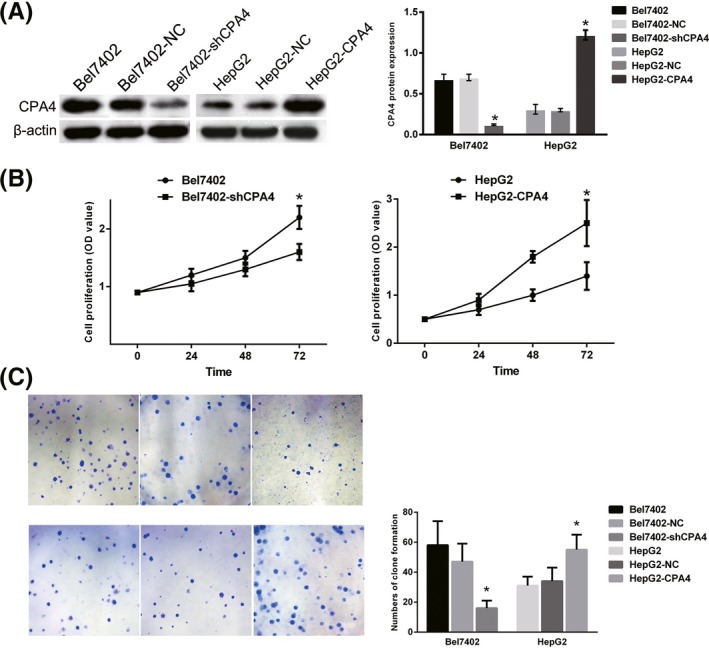

To demonstrate the function of CPA4 in HCC cells, CPA4 expression was first measured in the HCC cell lines HepG2 and Bel7402. Western blot analysis confirmed that both of these cell lines expressed CPA4, and the expression of CPA4 in Bel7402 cells was higher than in HepG2 cells. Then, we overexpressed CPA4 in HepG2 cells while downregulating CPA4 expression in Bel7402 cells to examine the effect of CPA4 on cell proliferation (Figure 1A). The results of the MTT (Figure 1B) assay and cell colony formation assay (Figure 1C) showed that the overexpression of CPA4 promoted HepG2 cell proliferation and that downregulated CPA4 expression inhibited Bel7402 cell proliferation compared with the corresponding control groups.

Figure 1.

Investigating carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4) expression in liver cancer cell lines and its role in tumour cell proliferation. A, Western blot analysis indicated that CPA4 was highly expressed in the CRC cell line Bel7402 but was lowly expressed in HepG2 cells. CPA4 was successfully downregulated in Bel7402 cells by shRNA and upregulated in HepG2 cells by a CPA4 overexpression plasmid (*P < 0.05). B, The in vitro cell proliferation capacities were detected via MTT and clone formation assays. The MTT assay results showed that the proliferate rate of the Bel7402‐shCPA4 cells (1.60 ± 0.11) was significantly slower than that of the Bel7402 cells (2.20 ± 0.29, P = 0.005), whereas the proliferation rate of HepG2‐CPA4 cells (2.50 ± 0.48) was significantly faster than that of the HepG2 group (1.40 ± 0.49, P = 0.008) (*P < 0.05). C, Clone formation assays indicated that the number and the size of the clones formed by Bel7402‐shCPA4 were lower and smaller than those of Bel7402 cells, and the HepG2‐CPA4 cells formed more and larger clone than the HepG2 cells (*P < 0.05) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.2. CPA4 induces cell sphere formation in serum‐free medium

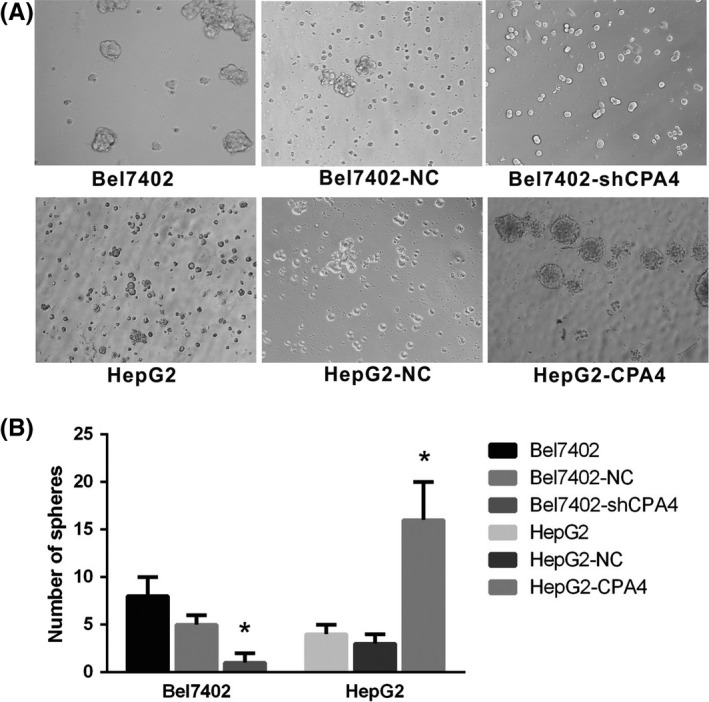

Reports have shown that the aberrant elevation of CPA4 is associated with the overexpression of stem cell markers in HCC tissues. To evaluate the relationship between CPA4 and stem cell characteristics, cell sphere formation assays in serum‐free medium were first used to assess self‐renewing capacity, which is considered a characteristic of stem cells. After 10 days of culture, HepG2‐CPA4 cells and Bel7402 cells formed tightly connected, ball‐like spheres. In the HepG2 and Bel7402‐shCPA4 groups, the bulk cells were apoptotic, and the few cells that survived exhibited a suspended growth pattern. The number of spheres formed in HepG2‐CPA4 cells and Bel7402 cells was significantly higher than that in HepG2 and Bel7402‐shCPA4 cells. High CPA4‐expressing cells displayed a higher sphere‐forming efficiency than low expressing cells, suggesting that high expression cells contain more stem‐like cells (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Detection of stem cell properties by sphere formation assays. A, Cell spheres formed after 10 d of culture in ultra‐low adsorption dishes with serum‐free medium. B, The number of round lucent spheres generated from Bel7402 and HepG2‐CPA4 cells was compared with that of Bel7402‐shCPA4 and HepG2 cells (*P < 0.05)

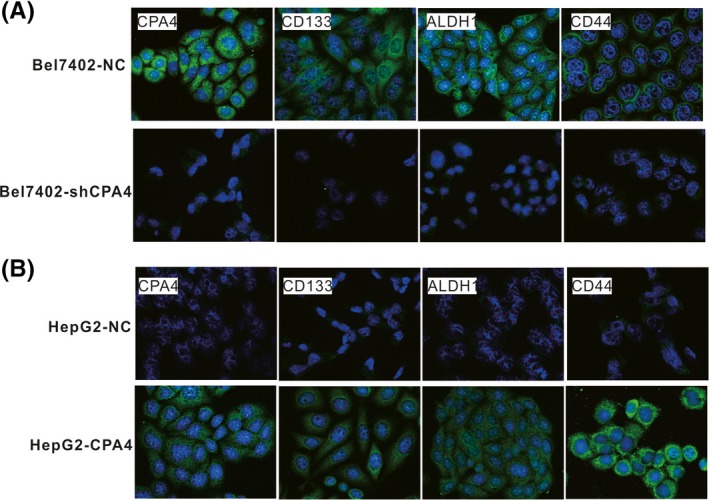

3.3. The expression of stem cell markers was affected by CPA4

Immunofluorescence results showed that compared with that in HepG2 parental cells, the expression of the stem cell markers CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 was higher in HepG2‐CPA4 cells. In addition, the expression of CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 was decreased in the CPA4‐downregulated Bel7402‐shCPA4 cells compared with that in the Bel7402 parental cells (Figure 3). These data indicate that CPA4 induces the expression of stem cell markers.

Figure 3.

Stem cell marker expression in different cell groups. A, The immunofluorescence staining results showed that Bel7402 cells, which express high levels of carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4), also showed increased expression of CD133, ALDH1 and CD44. When CPA4 was downregulated in Bel7402 cells, the stem cell marker expression was decreased. B, Upregulated CPA4 in HepG2 cells increased stem cell marker expression [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

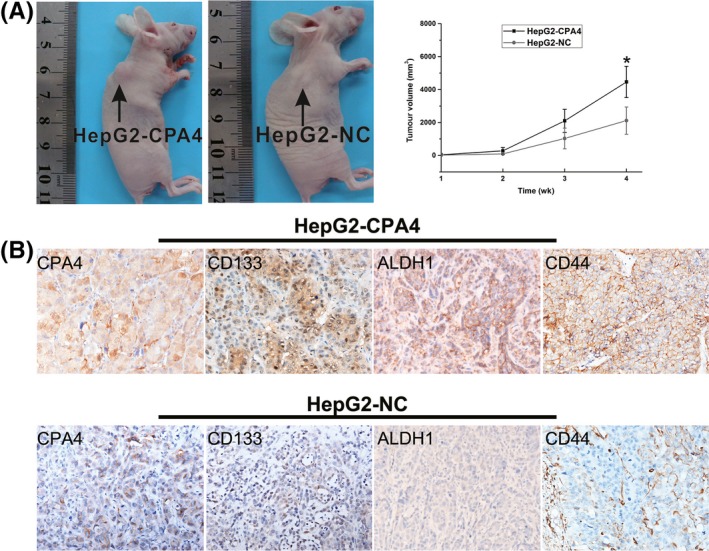

3.4. CPA4 promoted tumour growth in vivo

To confirm the function of CPA4 in tumour growth in vivo, experiments were performed using a nude mouse tumour xenograft model. As shown in Figure 4A, the average tumour volume was larger in the HepG2‐CPA4 group than in the HepG2‐NC group. Immunohistochemistry staining showed that the expression of CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 in the HepG2‐CPA4 xenograft tissues was significantly higher than in the HepG2 xenograft tissues (Figure 4B). These findings indicate that CPA4 promotes tumour growth and stem cell marker expression in vivo.

Figure 4.

A mouse xenograft model was utilized to study the effect of carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4) on tumour growth and how CPA4 correlates with stem cell marker expression in vivo. Mouse tumours were obtained and dissected 4 wk after the subcutaneous injection of the transfected HepG2‐CPA4 and HepG2 cells. A, The comparison of tumour volumes between the HepG2‐CPA4 and HepG2 groups (*P < 0.05). B, The expression of stem cell markers CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 was immunohistochemically evaluated in the HepG2‐CPA4 and HepG2 groups. The expression of CD133, ALDH1 and CD44 was higher in the HepG2‐CPA4 tumour tissues than in the HepG2 tumour tissues [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

4. DISCUSSION

Carboxypeptidase A4 was originally found in a screen of mRNAs upregulated by the sodium butyrate‐induced differentiation of cancer cells. Huang et al12 reported that CPA4 mRNA expression was associated with hormone‐regulated tissues that have a role in cell growth and differentiation. Further studies suggested that some of the peptides identified as CPA4 substrates have functions in cell proliferation and differentiation, potentially explaining the link between CPA4 and cancer aggressiveness. The abnormal expression of CPA4 was highly prevalent in gastric cancer (GC) tissues, positively associated with Ki67 and reversely correlated with p53 in GC.7, 8, 9, 10 In pancreatic cancer, serum samples overexpressing CPA4 were significantly correlated with tumour size.7, 8, 9, 10 These studies potentially explain the link between CPA4 and cell proliferation. In our study, the MTT assay and cell colony formation assay confirmed that the overexpression of CPA4 induced HCC cell proliferation and that the downregulation of CPA4 could reduce cell proliferation. In addition, the CPA4 concentration was also correlated with distant metastasis, lymph node involvement, advanced disease stage and poor overall survival of patients with pancreatic cancer and CRC.7, 8, 9, 10 Thus, CPA4 not only influences cell proliferation but is also involved in other malignant cell processes.

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are assumed to be a group of cells with the ability to initiate tumour growth, self‐renew and differentiate and are implicated in tumour initiation, progression, metastasis, recurrence and resistance to therapy.13, 14, 15, 16 Researchers have now provided evidence of the existence of CSCs that were isolated from several types of human tumours, such as brain tumours, breast cancer and colon cancer.17, 18, 19 It has been previously shown that stem cells cultured in suspension could generate non‐adherent spherical clusters of cells composed of stem cells and progenitor cells.20, 21 We showed that the overexpression of CPA4 causes a more dramatic induction of sphere clonogenicity, whereas repression of CPA4 leads to a reduction in sphere clonogenicity. Furthermore, variations in CPA4 expression levels in cells correlated with the expression of CD133, ALDH and CD44 markers. CD133 was the first marker used for enriching CSCs in human solid tumours.22 CD133 expression has been used to enrich CSCs in solid cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma,23 colon cancer,24 human melanoma 25 and many others. ALDH1 activation and high CD44 expression have also been reported as markers to identify cell populations enriched for CSCs in breast cancer,26 gastric cancer 27 and lung cancer.28 In general, only a minority of cells (<5%) in the total tumour cell population are believed to be stem cells, but the flow cytometric analysis of several studies revealed that the percentage of cells expressing CD133, CD44 or ALDH1 differed between several HCC cell lines (from <1% to more than 90%).29, 30, 31 In our study, the results shown in Figure 3 indicate that more cells with high CPA4 expression expressed stem cell markers; more Bel7402 cells expressed stem cell markers than HepG2 cells. Transfection with CPA4 plasmids increased stem cell marker expression, indicating that CPA4 may induce the proportion of stem cell marker‐expressing cells. The overexpression of CPA4 increased cell sphere formation in serum‐free medium, and the high expression of stem cell markers indicated that cells with high CPA4 expression exhibit more stem cell capacity. In addition, the role of CPA4 in regulating cell proliferation and stem cell characteristics was also confirmed in vivo. In this study, the tumours of the cells with upregulated CPA4 expression grew faster than those of the control group tumours in vivo. Since knock‐down in bel7402 cells was seemingly also associated with more apoptosis in vitro, the cause of CPA4‐accelerated tumour growth through stimulating cell proliferation or reducing apoptosis needs further identification. In xenograft tissues, the expression of CD133, ALDH and CD44 was higher in the tissues with overexpressed CPA4 than in the control group tissues.

Overall, the results of our study suggest that CPA4 can regulate tumour proliferation and stem cell capacity in HCC. However, further studies are needed to fully elucidate the function and mechanisms of CPA4 in tumour development and confirm its potential as a therapeutic target for HCC.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was partly supported by the Scientific Research Foundation of Tianjin Education Commission (No. 2017KJ225).

Zhang H, Hao C, Wang H, Shang H, Li Z. Carboxypeptidase A4 promotes proliferation and stem cell characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Exp Path. 2019;100:133–138. 10.1111/iep.12315

H. Zhang and C. Hao contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ding LJ, Li Y, Wang SD, et al. Long noncoding RNA lncCAMTA1 promotes proliferation and cancer stem cell‐like properties of liver cancer by inhibiting CAMTA1. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:E1617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Galuppo R, Maynard E, Shah M, et al. Synergistic inhibition of HCC and liver cancer stem cell proliferation by targeting RAS/RAF/MAPK and WNT/beta‐catenin pathways. Anticancer Res. 2014;34:1709‐1713. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kayashima T, Yamasaki K, Yamada T, et al. The novel imprinted carboxypeptidase A4 gene (CPA4) in the 7q32 imprinting domain. Hum Genet. 2003;112:220‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tanco S, Zhang X, Morano C, Aviles FX, Lorenzo J, Fricker LD. Characterization of the substrate specificity of human carboxypeptidase A4 and implications for a role in extracellular peptide processing. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18385‐18396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ross PL, Cheng I, Liu X, et al. Carboxypeptidase 4 gene variants and early‐onset intermediate‐to‐high risk prostate cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun L, Burnett J, Guo C, et al. CPA4 is a promising diagnostic serum biomarker for pancreatic cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2016a;6:91‐96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sun L, Guo C, Burnett J, Yang Z, Ran Y, Sun D. Serum carboxypeptidaseA4 levels predict liver metastasis in colorectal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016b;7:78688‐78697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun L, Guo C, Yuan H, et al. Overexpression of carboxypeptidase A4 (CPA4) is associated with poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2016c;8:5071‐5075. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun L, Wang Y, Yuan H, et al. CPA4 is a novel diagnostic and prognostic marker for human non‐small‐cell lung cancer. J Cancer. 2016;7:1197‐1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sun L, Guo C, Burnett J, et al. Association between expression of Carboxypeptidase 4 and stem cell markers and their clinical significance in liver cancer development. J Cancer. 2017;8:111‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Huang H, Reed CP, Zhang JS, Shridhar V, Wang L, Smith DI. Carboxypeptidase A3 (CPA3): a novel gene highly induced by histone deacetylase inhibitors during differentiation of prostate epithelial cancer cells. Can Res. 1999;59:2981‐2988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Konrad CV, Murali R, Varghese BA, Nair R. The role of cancer stem cells in tumor heterogeneity and resistance to therapy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;95:133‐15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ni XG, Zhao P. Progress of cancer stem cells of solid tumor. Ai Zheng. 2006;25:775‐778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. O'Brien CA, Kreso A, Jamieson CH. Cancer stem cells and self‐renewal. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3113‐3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wu XZ. Origin of cancer stem cells: the role of self‐renewal and differentiation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:407‐414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Crabtree JS, Miele L. Breast cancer stem cells. Biomedicines. 2018;6:E77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dirks PB. Brain tumor stem cells: the cancer stem cell hypothesis writ large. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:420‐430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pannequin J. Cancer stem cells in colon cancer. Bull Cancer. 2017;104:1072‐1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cao L, Zhou Y, Zhai B, et al. Sphere‐forming cell subpopulations with cancer stem cell properties in human hepatoma cell lines. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen SF, Chang YC, Nieh S, Liu CL, Yang CY, Lin YS. Nonadhesive culture system as a model of rapid sphere formation with cancer stem cell properties. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grosse‐Gehling P, Fargeas CA, Dittfeld C, et al. CD133 as a biomarker for putative cancer stem cells in solid tumours: limitations, problems and challenges. J Pathol. 2013;229:355‐378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ma S. Biology and clinical implications of CD133(+) liver cancer stem cells. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:126‐132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kawamoto H, Yuasa T, Kubota Y, et al. Characteristics of CD133(+) human colon cancer SW620 cells. Cell Transplant. 2010;19:857‐864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Welte Y, Davies C, Schafer R, Regenbrecht CR. Patient derived cell culture and isolation of CD133(+) putative cancer stem cells from melanoma. J Vis Exp. 2013:e50200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Adams A, Warner K, Pearson AT, et al. ALDH/CD44 identifies uniquely tumorigenic cancer stem cells in salivary gland mucoepidermoid carcinomas. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26633‐26650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wakamatsu Y, Sakamoto N, Oo HZ, et al. Expression of cancer stem cell markers ALDH1, CD44 and CD133 in primary tumor and lymph node metastasis of gastric cancer. Pathol Int. 2012;62:112‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu J, Xiao Z, Wong SK, et al. Lung cancer tumorigenicity and drug resistance are maintained through ALDH(hi)CD44(hi) tumor initiating cells. Oncotarget. 2013;4:1698‐1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lin B, Chen T, Zhang Q, et al. FAM83D associates with high tumor recurrence after liver transplantation involving expansion of CD44+ carcinoma stem cells. Oncotarget. 2016;7:77495‐77507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Song Y, Jang J, Shin TH, et al. Sulfasalazine attenuates evading anticancer response of CD133‐positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhu Z, Hao X, Yan M, et al. Cancer stem/progenitor cells are highly enriched in CD133+CD44+ population in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:2067‐2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]