Abstract

Background

This is an updated version of the original Cochrane review published in Issue 1, 1999. Patient surveys have shown that postoperative pain is often not managed well, and there is a need to assess the efficacy and safety of commonly used analgesics as newer treatments become available. Dextropropoxyphene is one example of an opioid analgesic that used to be widely prescribed for pain relief in combination with paracetamol under names such as Co‐proxamol and Distalgesic. This drug is now only available on a named patient basis in the UK. For this group there is a provision for the supply of unlicensed co‐proxamol on the responsibility of the prescriber.

Objectives

To determine the analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of single dose oral dextropropoxyphene alone and in combination with paracetamol (acetaminophen) for moderate to severe postoperative pain.

Search methods

Published studies were identified from: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane CENTRAL up to December 2007, and the Oxford Pain Relief Database (1954 to 1994).

Selection criteria

The inclusion criteria used were: full journal publication, postoperative pain, postoperative oral administration, adult participants, baseline pain of moderate to severe intensity, double‐blind design, and random allocation to treatment groups which included dextropropoxyphene and placebo or a combination of dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol and placebo.

Data collection and analysis

Data were extracted by two review authors, and studies were quality scored.

Summed pain intensity and pain relief data were extracted and converted into dichotomous information to yield the number of participants with at least 50% pain relief. This was used to calculate the relative benefit and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT) for one participant to achieve at least 50% pain relief.

Main results

Eleven studies met the inclusion criteria. Six studies (440 participants) compared dextropropoxyphene with placebo, four studies (325 participants) and one individual patient meta‐analysis (638 participant) compared dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol 650 mg with placebo.

For a single dose of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg in postoperative pain the NNT for at least 50% pain relief was 7.7 (95% confidence interval (CI) 4.6 to 22) when compared with placebo over four to six hours. There was no significant difference between the proportion of participants remedicating within four to eight hours with dextroporpoxyphene 65 mg (35%) and placebo (43%), relative risk 0.8 (0.7 to 1.03).

For the equivalent dose of dextropropoxyphene combined with paracetamol 650 mg the NNT was 4.4 (3.5 to 5.6) when compared with placebo. These results were compared with those for other analgesics obtained from equivalent systematic reviews. Significantly fewer participants remedicated within four to eight hours with dextropropoxyphene 65 mg combined with paracetamol 650 mg (34%) than with placebo (57%), relative risk 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8).

Pooled data showed increased incidence of central nervous system adverse effects for dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol compared with placebo.

Authors' conclusions

Since the last version of this review no new relevant studies have been identified. The combination of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg with paracetamol 650 mg shows similar efficacy to tramadol 100 mg for single dose studies in postoperative pain but with a lower incidence of adverse effects. The same dose of paracetamol combined with 60 mg codeine appears more effective but, with the slight overlap in the 95% CI, this conclusion is not robust. Adverse effects of both combinations were similar.

Ibuprofen 400 mg has a lower (better) NNT than both dextropropoxyphene 65 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg and tramadol 100 mg.

Plain language summary

Dextropropoxyphene in a single dose taken on its own and also with paracetamol to treat postoperative pain

This review assessed the analgesic efficacy and adverse effects that single dose oral dextropropoxyphene taken alone or in combination with paracetamol had in treating moderate to severe postoperative pain. The combination of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg with paracetamol 650 mg showed similar efficacy to that of tramadol 100 mg for single dose studies in postoperative pain but with a lower incidence of side effects. This review also highlighted that Ibuprofen 400 mg was yet more effective than both tramadol 100 mg and dextropropoxyphene 65 mg.

Background

This is an update of a previously published review in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 1, 1999) on 'Single dose dextropropoxyphene for the treatment of acute postoperative pain'.

Dextropropoxyphene is an opioid analgesic which has been widely available since the 1950s. It used to be commonly available, particularly in combination with paracetamol under such names as Co‐proxamol and Distalgesic. In 1996, there were ten million prescriptions in England for Co‐proxamol alone, representing one fifth of all analgesics prescribed (opioid, non‐opioid centrally acting, non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS)) though it is not clear how much was used for postoperative pain (GSS 1996). There have been increasing limits on prescribing in recent years, especially in the UK, and to some extent in Australia. The reason for this was concern about intentional overdose in the community, and as many as 300 to 400 deaths per year were attributed to dextropropoxyphene combinations with paracetamol. The result is that the combination of dextropropoxyphene combined with paracetamol is much less prescribed in the UK with 2006 prescriptions down to 1.4 million of dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol. This drug is now only available on a named patient basis in the UK. For this group there is a provision for the supply of unlicensed co‐proxamol on the responsibility of the prescriber.

Patient surveys have shown that postoperative pain is often not managed well (Bruster 1994). There is no report of significant improvement in acute pain treatment in hospital in recent decades with the use of dextropropoxyphene, although individual units can often demonstrate excellent results. In part this is because of managerial problems rather than a lack of analgesic efficacy. The efficacy and safety of commonly used analgesics and newer treatments still require evaluation. Judging relative analgesic efficacy is difficult as clinical trials use a variety of comparators; more recent clinical trials tend to be better conducted and reported, and are larger than older ones. Efficacy can be determined indirectly by comparing analgesics with placebo in similar clinical circumstances to produce a common analgesic descriptor such as number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT) to achieve at least 50% pain relief.

A reliable method has been developed to convert mean pain outcome values from categorical scales (percent of maximum possible pain intensity or pain relief; %maxSPID and %maxTOTPAR) into dichotomous information (number of participants with at least 50% pain relief) (Moore 1996; Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b). Other possible outcomes of interest include the requirement of patients to remedicate within a particular time window.

Objectives

To quantitatively evaluate the analgesic efficacy and adverse effects of dextropropoxyphene, both with and without paracetamol, in postoperative pain. To compare the results with those for other analgesics assessed in the same way in order to provide evidence‐based recommendations for clinical practice.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Studies were included if they were a full journal publication of single dose, randomised, double‐blind, placebo controlled trials in postoperative pain. Multiple dose studies were included if the appropriate data from the first dose was available.

Studies were excluded if they did not clearly state that the interventions had been randomly allocated. Also excluded were studies of experimental pain, case reports and clinical observations. Abstracts and unpublished data were not included.

Types of participants

Only studies of adult participants with established postoperative pain of moderate to severe intensity were included.

Types of interventions

Studies were included if they contained a treatment group allocated to either dextropropoxyphene alone or a combination of dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol. Treatments and placebo were administered orally.

Types of outcome measures

The derived pain relief outcomes used were TOTPAR (total pain relief) or SPID (summed pain intensity difference) over four to six hours or sufficient data provided to allow their calculation. The pain measures used for the calculation of TOTPAR or SPID were the five point pain relief (PR) scale with standard or comparable wording (none, slight, moderate, good, complete) or the four point pain intensity (PI) scale (none, mild, moderate, severe) or a visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain relief or pain intensity.

Also accepted were global evaluations of pain relief over four to six hours if measured on a five point scale by the participant and not the investigator. The data were extracted as dichotomous information (number of participants reporting good or excellent).

The number of participants who remedicated in the period of four to eight hours was also used, and the median time to remedication, if information was available was also assessed.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic databases The following electronic databases were searched: Cochrane CENTRAL (Issue 2, 2004 for original review and Issue 4, 2007 for the update); MEDLINE and Pre‐MEDLINE from 1966 to July 1998 for the original review, and MEDLINE from January 1998 to December 2007 for the update; EMBASE from 1980 to July 1998 for the original review and January 1998 to December 2007 for the update; the Oxford Pain Relief database (handsearch records for the years 1954 to 1995 (Jadad 1996a).

The search for MEDLINE can be seen in Appendix 1 which was adapted to search other databases.

Reference lists of retrieved reports were also manually searched. Unpublished data were not sought.

Data collection and analysis

From each study we extracted: the number of participants treated, the mean TOTPAR or mean SPID, study duration, the dose of dextropropoxyphene and paracetamol where appropriate, and information on adverse effects. Mean TOTPAR and mean SPID values were converted to %maxTOTPAR or %maxSPID by division into the calculated maximum value (Cooper 1991). The following equations were used to estimate the proportion of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR (Moore 1997a; Moore 1997b):

Proportion with >50% maxTOTPAR = 1.33 x mean %maxTOTPAR ‐ 11.5

Proportion with >50% maxTOTPAR = 1.36 x mean %maxSPID ‐ 2.3

The proportions were converted to the number of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR by multiplying by the total number of participants in the treatment group. The number of participants with at least 50% maxTOTPAR was then used to calculate relative benefit and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐benefit (NNT).

Relative benefit (RB) and relative risk (RR) estimates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated using the fixed‐effect model (Gardner 1986). Homogeneity was assumed when P > 0.1. A statistically significant benefit of active treatment over placebo was assumed when the lower limit of the 95% CI of the RB was >1. A statistically significant benefit of placebo over active treatment was assumed when the upper limit of the 95% CI of the RB was <1. NNT and number‐needed‐to‐treat‐to‐harm (NNH) with 95% CI were calculated (Cook 1995). The CI includes no benefit of one treatment over the other when the upper limit is represented as infinity. Calculations were performed using Excel v 5.0 on a Macintosh Performa 6320.

Dextropropoxyphene is available as either a hydrochloride or napsylate salt. Equivalent molar doses are 65 mg of dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride and 100 mg of dextropropoxyphene napsylate. We did not distinguish between the different salts, other than to combine equivalent doses of dextropropoxyphene base.

Results

Description of studies

One hundred and thirty two published studies were identified from the search as potential single dose RCTs. Two could not be obtained through either Oxford University Library or the British Library and attempts to contact the authors were unsuccessful. Five citations obtained from reference lists of the retrieved studies could not be traced by the British Library. Of the 125 retrieved studies 34 were not RCTs, 21 were not postoperative pain models or included other pain conditions, 27 were not placebo controlled, in five dextropropoxyphene was administered but was not the intervention being investigated, one was a preliminary report of a trial in progress which contained no data, one was an abstract and one was intra‐muscular administration.

Of the 35 RCTs that were placebo controlled 23 were excluded. In 16 studies participants did not have baseline pain of at least moderate severity. This is methodologically important as testing the intervention on participants with established pain ensures adequate sensitivity (Lasagna 1962). In six studies pain outcome measurements other than those described in the selection criteria were used. As the method for generating dichotomous data has only been verified for the most commonly used pain scales (those described in the selection criteria) applied over four to six hours, other outcome measurements cannot be legitimately used with this technique. One study was not double‐blind. The data from one study was duplicated and therefore added to the primary study which was Moore 1997. Eleven reports met our inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis.

Risk of bias in included studies

Each report was independently scored for quality by two of the review authors using a three‐item scale with a maximum score of five (see below) (Jadad 1996b); all of the review authors then met to agree upon a 'consensus' score for each report.

The quality scores for individual studies are reported in the notes section of the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. These scores were not used to weight the results in any way.

The scale used is as follows: Is the study randomised ? If yes ‐ 1 point Is the randomisation procedure reported and is it appropriate ? If yes add 1 point, if no deduct 1 point Is the study double blind ? If yes add 1 point Is the double blind method reported and is it appropriate ? If yes add 1 point, if no deduct 1 point Are the reasons for patient withdrawals and dropouts described ? If yes add 1 point

Effects of interventions

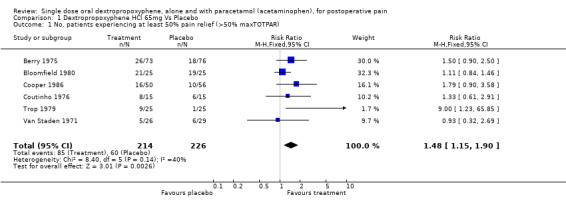

Dextropropoxyphene versus placebo Six studies compared dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride 65 mg (214 participants) with placebo (226 participants), and one study also compared a dose of 130 mg (25 participants) with placebo (25 participants). Two studies (Berry 1975; Bloomfield 1980) investigated postpartum pain (episiotomy), one pain following peridontal surgery (Cooper 1986), one post‐urogenital surgery (Coutinho 1976), one post‐gynaecological surgery (Van Staden 1971), and one after various surgical interventions (Trop 1979).

The placebo response rate (the proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with placebo) varied between 4 and 76%. The dextropropoxyphene response rate (the proportion of participants experiencing at least 50% pain relief with dextropropoxyphene) varied between 19 and 84%. Dextropropoxyphene 65 mg was significantly different from placebo, RB 1.5 (1.2 to 1.9).

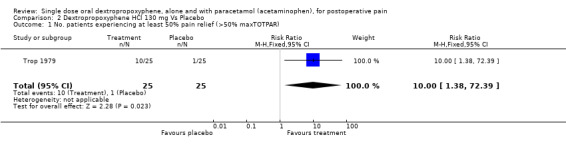

For a single dose of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg the NNT was 7.7 (4.6 to 22) for at least 50% pain relief over a period of four to six hours compared with placebo for pain of moderate to severe intensity. One study (Trop 1979) used a dose of 130 mg of dextropropoxyphene (25 participants). The RB estimate for dextropropoxyphene 130 mg compared with placebo was 10 (1.4 to 72) and the NNT was 2.8 (1.8 to 6.5) for at least 50% relief of pain of moderate to severe intensity over a period of five hours compared with placebo.

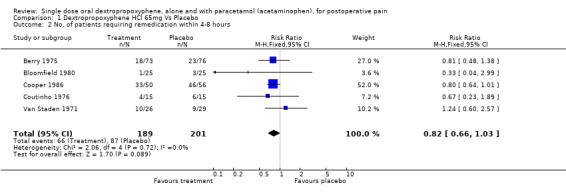

There was no significant difference between the proportion of participants remedicating within four to eight hours with dextroporpoxyphene 65 mg (35%) and placebo (43%), RR 0.8 (0.7 to 1.03).

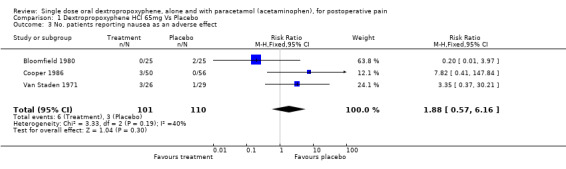

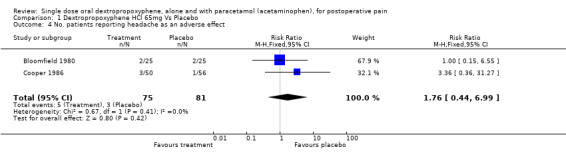

Adverse effects: Details of adverse effects are given in the notes section of the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. No participants withdrew as a result of adverse effects. All were reported as transient and of mild to moderate severity. One study reported no adverse effects with either placebo or active treatment (Berry 1975).

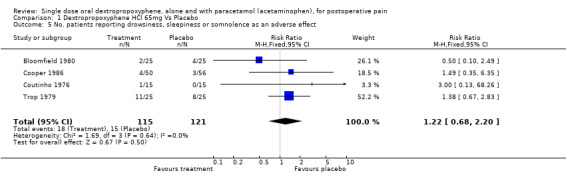

In one study the authors reported both dextropropoxyphene 65 mg and 130 mg to have a significantly higher incidence of 'grogginess', 'sleepiness', and 'light‐headedness' than placebo (P = 0.05) (Trop 1979). However, pooled data from the four studies reporting either drowsiness, sleepiness or somnolence (Bloomfield 1980; Cooper 1986; Coutinho 1976; Trop 1979) showed no significant difference in incidence between dextropropoxyphene 65 mg (18/115) and placebo (15/121), with a RR of 1.3 (0.7 to 2.2). No other study reported light‐headedness or 'grogginess' in the dextropropoxyphene group.

Dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol versus placebo Four studies compared dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg with placebo, and one used dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride 65 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg. A total of 478 participants received dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol, and 485 participants received placebo. Two studies (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981) looked at pain following dental surgery (impacted third molar), two (Evans 1982; Honig 1981) post‐orthopaedic surgery, and one (Moore 1997) pain following both dental and general surgery (abdominal, orthopaedic and gynaecological).

One study (Moore 1997) was a meta‐analysis of individual patient data from 18 original studies providing dichotomous information (the number of participants achieving at least 50% maxTOTPAR). Eight of these studies investigated dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg plus paracetamol 650 mg; one of these eight studies had been published separately by Sunshine et al and was added as a secondary study to Moore 1997.

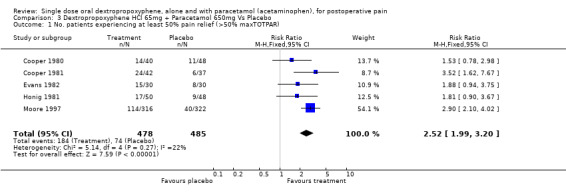

The placebo response rate varied between 6% and 27%. The dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol response rate varied between 25% and 57%. Dextropropoxyphene (65 mg hydrochloride or 100 mg napsylate) plus paracetamol 650 mg was significantly superior to placebo, relative benefit 2.5 (2.0 to 3.2). For a single dose of dextropropoxyphene (65 mg hydrochloride or 100 mg napsylate) plus paracetamol 650 mg the NNT was 4.4 (3.5 to 5.6) for at least 50% pain relief over four to six hours compared with placebo for pain of moderate to severe intensity.

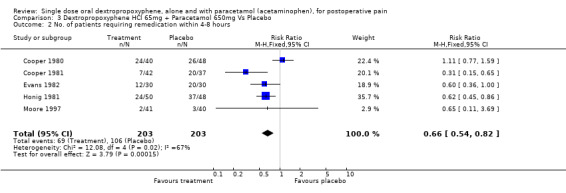

Significantly fewer participants remedicated within four to eight hours with dextropropoxyphene 65 mg combined with paracetamol 650 mg (34%) than with placebo (57%), RR 0.7 (0.5 to 0.8).

Adverse effects Details of adverse effects are given in the notes section of the 'Characteristics of included studies' table. No participants withdrew as a result of adverse effects and all were reported as transient and of mild to moderate severity. One study (Honig 1981) did not give details of adverse effects but reported that there was no significant difference between active and placebo groups. The individual patient meta‐analysis (Moore 1997) pooled data on adverse effects from all 18 placebo groups; 714 participants received placebo. Where possible the NNH has been calculated. This is the number of participants who need to receive the treatment in order for one of them to suffer the adverse event.

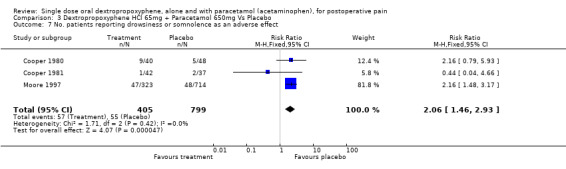

Three studies reported the incidence of drowsiness or somnolence (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Moore 1997). The pooled data indicated a significantly higher incidence of drowsiness and somnolence in the dextropropoxyphene combination group (57/405) than in the placebo group (55/799), with a RR of 2.1 (1.5 to 2.9) and a NNH of 14 (9.1 to 30).

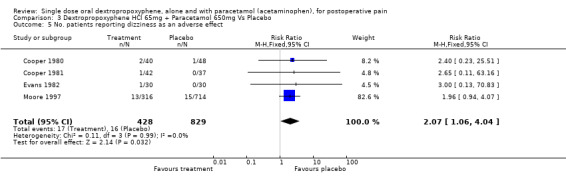

Four studies reported dizziness (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Evans 1982; Moore 1997). Pooled data indicated a significantly higher incidence of dizziness with dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (17/428) compared with placebo (16/829), with a RR of 2.2 (1.1 to 4.3) and NNH of 50 (24 to infinity).

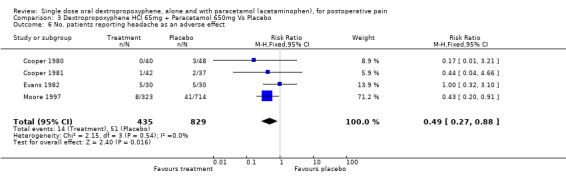

Four studies reported the incidence of headache (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Evans 1982; Honig 1981). The pooled data showed dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (14/435) to have a significantly lower incidence of headache than placebo (51/829), with a RR of 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) and number‐needed‐to‐harm of ‐33 (‐170 to ‐19).

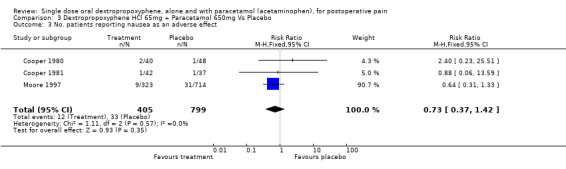

Three studies reported the incidence of nausea (Cooper 1980; Cooper 1981; Moore 1997). Pooled data showed no significant difference with dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (12/405) than with placebo (33/799), RR 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4).

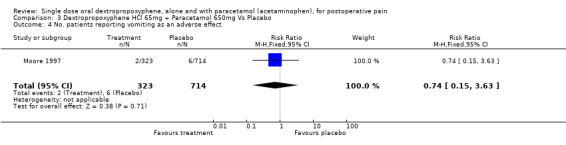

Vomiting was reported in one study (Moore 1997). The incidence of vomiting with dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (2/323) was not significantly different from placebo (6/714), RR 1.4 (0.3 to 6.7).

Discussion

For a single dose of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg the NNT was 7.7 (4.6 to 22) for at least 50% pain relief compared with placebo. This means that one in every eight participants with pain of moderate to severe intensity would experience at least 50% pain relief with dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride 65 mg who would not have done so with placebo. The equivalent NNT for a single dose of dextropropoxyphene (65 mg hydrochloride or 100 mg napsylate) plus paracetamol 650 mg was 4.4 (3.5 to 5.6), indicating higher efficacy. The CIs of the NNT for dextropropoxyphene alone and for the combination with paracetamol overlapped.

For a single dose of dextropropoxyphene 130 mg the NNT was 2.8 (1.8 to 6.5). This difference in NNTs appears to show a dose response for dextropropoxyphene. However, given the overlapping CIs and the very small number of participants in the dextropropoxyphene 130 mg trial (50) this conclusion is not robust.

It was surprising that there were so few eligible randomised studies comparing either dextropropoxyphene alone or in combination with paracetamol against placebo considering the background of ten million prescriptions in 1996 in the UK for combinations with paracetamol. This probably reflects the fact that many of the studies were performed over 20 years ago when the now well established and validated methodology for single dose analgesic trials was still being developed.

A rank order of single dose analgesic efficacy in postoperative pain of moderate to severe intensity was presented previously (Collins 1998a). The additional information came from systematic reviews of single dose studies of a wide range of analgesics tested in postoperative pain which used a similar method (Collins 1998b; Moore 1997; Moore 1997c). The only analgesic whose 95% CIs does not overlap the lower limit CI for the dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol combination was ibuprofen 400 mg (CI 2.5 to 3.0), which has a lower (better) NNT of 2.7. However, as some patients cannot be prescribed NSAIDS it may be more appropriate to compare dextropropoxyphene with tramadol or a combination of paracetamol and codeine. The dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (65 mg/650 mg) combination has a slightly lower NNT than that for tramadol 100 mg (NNT 4.8 (3.8 to 6.1)), although the CIs overlap substantially. Paracetamol 650 mg with codeine 60 mg has a lower NNT than both (NNT 3.6 (2.9 to 4.5)) with less overlap of the CIs.

With dextropropoxyphene with and without paracetamol, about 35% of participants remedicated within four to eight hours. With placebo, the percentage remedicating was higher at 43% and 57% respectively. For the latter, but not the former, the difference achieved statistical significance. It is possible that, with more comparative information for other analgesics, and especially with reporting at the level of the individual patient, more and better outcomes can be found, one of which is likely to be remedication time or percentage (Moore 2005).

A single dose of dextropropoxyphene plus paracetamol (65 mg/650 mg) showed a significantly higher incidence of central nervous system adverse effects (somnolence, dizziness) than placebo. The same dose of paracetamol when combined with codeine 60 mg also showed a significantly higher incidence of dizziness and drowsiness than placebo, NNH of 25 (7.7 to 257) and 10 (4.6 to 31) respectively. These adverse effects have also been shown for tramadol 100 mg with a lower (worse) NNH for both dizziness (NNH 13 (9 to 20)) and somnolence (NNH 9 (6 to 13)) (Moore 1997). Tramadol 100 mg also showed a significantly higher incidence of nausea and vomiting than placebo. Nausea and vomiting were reported with both paracetamol combinations (dextropropoxyphene 65 mg or codeine 60 mg) but the incidence for either combination was not significantly different from placebo.

The combination of dextropropoxyphene 65 mg with paracetamol 650 mg showed similar efficacy to tramadol 100 mg for single dose studies in postoperative pain but the combination had a lower incidence of adverse effects. The same dose of paracetamol in combination with 60 mg codeine appears more effective, but with the slight overlap in the 95% CIs this conclusion is not robust. The two paracetamol combinations could not be separated for adverse effects as the NNH CIs for both dizziness and drowsiness/somnolence overlap considerably.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Dextropropoxyphene is not particularly effective on its own in single dose postoperative use. It is far more commonly used in combination with paracetamol and our results support the assertion that this provides more effective analgesia. However, evidence produced by the same methodology suggests that ibuprofen 400 mg provides better analgesia for postoperative pain than the paracetamol/dextropropoxyphene combination. In some parts of the world limitations on prescribing make dextropropoxyphene increasingly difficult to obtain.

Implications for research.

Dextropropoxyphene alone and in combination with paracetamol was previously extensively used. One of the major problems with reviewing such well established interventions is that the original studies may predate the development of validated analgesic trial methodology. However, a quantitative assessment of these interventions is required as a comparison for novel analgesics. Potentially more evidence may be produced by using the combination as the 'gold standard' analgesic in RCTs of new interventions. It is unlikely that new studies in acute pain will feature dextropropoxyphene alone or in combination with paracetamol, and there does not appear to be any pressing need for new studies because there are many alternative analgesics now available.

The combination of dextropropoxyphene with paracetamol has been widely used in chronic pain. Although results from single dose studies usually translate reasonably well to multiple dose situations, a method needs to be developed to quantitatively assess both efficacy and adverse effects in prolonged usage.

Feedback

Plain language summary correction, 2 September 2009

Summary

Name: Patrick McAuliffe Feedback: Pertaining to the last sentence of the plain language summary; was the last part supposed to refer to dextropropoxyphene 65 mg, or 650 mg, as stated?

Reply

Sheena Derry: Yes, we're agreed, it should be dextropropoxyphene 65 mg, and not 650 mg, the text has now been revised.

Contributors

Patrick McAuliffe, Sheena Derry

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 29 May 2019 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 5 June 2008 | Review declared as stable | The review authors consider that additional relevant studies are unlikely to be conducted, and that further updates of this review are unnecessary. |

History

Review first published: Issue 4, 1998

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 24 September 2010 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 4 July 2010 | Amended | Jayne Rees reverted to Jayne Edwards so that citations from the Cochrane Library match those from bibliographic databases outside Cochrane |

| 2 September 2009 | Feedback has been incorporated | Error in Plain language summary relating to dose of dextropopoxyphene corrected. |

| 13 May 2009 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

| 12 November 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

| 28 May 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 21 January 2008 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Further studies satisfying our inclusion criteria were sought in MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid) and Cochrane CENTRAL from January 2002 to December 2007. No further studies were identified, but some additional data was identified and included on remedication. The conclusions of the review are unchanged. There have been recent changes with regards to prescribing of the drug. |

| 21 January 2008 | New search has been performed | Review updated with new authors |

| 25 January 2002 | Amended | New studies sought but not yet excluded or included |

Notes

The review authors consider that additional relevant studies are unlikely to be conducted, and that further updates of this review are unnecessary.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Eija Kalso, Pascale Picard, Tomohide Suzuki and Martin Tramèr for translating studies.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy

Search strategy in MEDLINE 1. dextropropxyphene [single term MeSH] 2. dextropropoxyphene 3. OR/1‐2 4. PAIN, POSTOPERATIVE [single term MeSH] 5. ((postoperative adj4 pain$) or (post‐operative adj4 pain$) or post‐operative‐pain$ or (post$ NEAR pain$) or (postoperative adj4 analgesi$) or (post‐operative adj4 analgesi$) or ("post‐operative analgesi$")) [in title, abstract or keywords] 6. ((post‐surgical adj4 pain$) or ("post surgical" adj4 pain$) or (post‐surgery adj4 pain$)) [in title, abstract or keywords] 7. (("pain‐relief after surg$") or ("pain following surg$") or ("pain control after")) [in title, abstract or keywords] 8. (("post surg$" or post‐surg$) AND (pain$ or discomfort)) [in title, abstract or keywords] 9. ((pain$ adj4 "after surg$") or (pain$ adj4 "after operat$") or (pain$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (pain$ adj4 follow$ surg$")) [in title, abstract or keywords] 10. ((analgesi$ adj4 "after surg$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "after operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 "follow$ operat$") or (analgesi$ adj4 follow$ surg$")) 11. OR/5‐10 12. randomized controlled trial.pt. 13. controlled clinical trial.pt. 14. randomized controlled trials.sh. 15. random allocation.sh. 16. double‐blind method.sh. 17. single blind method.sh. 18. clinical trial.pt. 19. exp clinical trials/ 20. (clin$ adj25 trial$).ti,ab. 21. ((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj25 (blind$ or mask$)).ti,ab. 22. placebos.sh. 23. placebo$.ti,ab. 24. random$.ti,ab. 25. research design.sh. 26. OR/12‐25 27. 3 AND 11 AND 26

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR) | 6 | 440 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.48 [1.15, 1.90] |

| 2 No. of patients requiring remedication within 4‐8 hours | 5 | 390 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.82 [0.66, 1.03] |

| 3 No. patients reporting nausea as an adverse effect | 3 | 211 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.88 [0.57, 6.16] |

| 4 No. patients reporting headache as an adverse effect | 2 | 156 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.76 [0.44, 6.99] |

| 5 No. patients reporting drowsiness, sleepiness or somnolence as an adverse effect | 4 | 236 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.22 [0.68, 2.20] |

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 2 No. of patients requiring remedication within 4‐8 hours.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 3 No. patients reporting nausea as an adverse effect.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 4 No. patients reporting headache as an adverse effect.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 5 No. patients reporting drowsiness, sleepiness or somnolence as an adverse effect.

Comparison 2. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 130 mg Vs Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR) | 1 | 50 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 10.0 [1.38, 72.39] |

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 130 mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR).

Comparison 3. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR) | 5 | 963 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.52 [1.99, 3.20] |

| 2 No. of patients requiring remedication within 4‐8 hours | 5 | 406 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.66 [0.54, 0.82] |

| 3 No. patients reporting nausea as an adverse effect | 3 | 1204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [0.37, 1.42] |

| 4 No. patients reporting vomiting as an adverse effect | 1 | 1037 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.15, 3.63] |

| 5 No. patients reporting dizziness as an adverse effect | 4 | 1257 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.07 [1.06, 4.04] |

| 6 No. patients reporting headache as an adverse effect | 4 | 1264 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.27, 0.88] |

| 7 No. patients reporting drowsiness or somnolence as an adverse effect | 3 | 1204 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.06 [1.46, 2.93] |

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 1 No. patients experiencing at least 50% pain relief (>50% maxTOTPAR).

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 2 No. of patients requiring remedication within 4‐8 hours.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 3 No. patients reporting nausea as an adverse effect.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 4 No. patients reporting vomiting as an adverse effect.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 5 No. patients reporting dizziness as an adverse effect.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 6 No. patients reporting headache as an adverse effect.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65mg + Paracetamol 650mg Vs Placebo, Outcome 7 No. patients reporting drowsiness or somnolence as an adverse effect.

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Berry 1975.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups. Assessed by observer in hospital at 1/2, 1 hr, then hourly for 4 hrs. Medication taken when pain was of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Postpartum pain (episiotomy) n=225 Age: 15‐39 | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n=73 Placebo, n=76 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) non‐standard Global evaluation (good or excellent): Dextropropoxyphene 26/73 Placebo 18/76 r | |

| Notes | Patients were allowed to remedicate "after a reasonable amount of time". No adverse effects were reported with either active treatment or placebo. 225 patients data analysed. No details given of withdrawals or dropouts. QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Bloomfield 1980.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups. Assessed, in hospital, by same nurse observer at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 6 hours. Medication taken when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Postpartum pain (episiotomy) n = 100 Age: adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n = 25 Placebo, n = 25 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR not measured Dextropropoxyphene was not significantly better than placebo at the 10% probability level SPID at 6 hours: Dextropropoxyphene = 9.32 Placebo = 8.12 | |

| Notes | If patients remedicated they were withdrawn from the study. Subsequent PR readings were set to the pre‐treatment score. 100 patients data were analysed. 6 withdrew: either no pain relief or patients remedicated No serious adverse effects were reported & no patients withdrew as a result Dextropropoxyphene: 6/25 patients reported 12 adverse events Placebo: 9/25 patients reported 9 adverse events QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cooper 1980.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, mostly local anaesthetic. Self‐assessed at 0, 1 hr then hourly for 4 hrs. Medication given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Dental surgery n = 179 Age: Adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 40 Placebo, n= 48 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) standard Global evaluation by patient (5 point scale) at 4 hrs Combination of dextropropoxyphene with paracetamol was significantly better than placebo for SPID and TOTPAR (P < 0.05). 4 hr TOTPAR: Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 5.65 Placebo: 4.17 | |

| Notes | Did not state when remedication allowed. If remedicated last PR and PI score before remedication were used for all further time points. 179 patients data were analysed. No withdrawals were reported. No serious adverse events reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 10/40 patients reported 13 adverse events. Placebo: 13/48 patients reported 17 adverse events. QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cooper 1981.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, general or local anaesthetic. Self‐assessed at home at 0, 1 hr then hourly for 4 hours. Medication given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Dental surgery n = 248 Age: Adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene napsylate100 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 42 Placebo, n = 37 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) standard Global evaluation by patient (5 point scale) at 4 hrs Combination of dextropropoxyphene with paracetamol was significantly better than placebo for SPID and TOTPAR (P < 0.001). 4 hr TOTPAR: Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 8.31 Placebo: 3.38 | |

| Notes | Remedication allowed at > 1 hr; if remedicated before patient withdrawn from study. If remedicated after PR recorded as 0, and last PI score prior to remedication taken for all further time points. 200 patients data were analysed. 48 excluded: 31 violated protocol, 17 did not take medication. No serious adverse events were reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 5/42 patients reported 5 adverse events. Placebo: 4/37 patients reported 5 adverse events. QS = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Cooper 1986.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, local anaesthetic. Self‐assessed at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 6 hours. Medication taken when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Periodontal surgery n = 301 Age: adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n = 50 Placebo, n = 56 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) standard Global evaluation by patient at 6 hrs (5 point) Dextropropoxyphene was significantly better than placebo (P < 0.1) TOTPAR at 6 hrs: Dextropropoxyphene: 7.7 Placebo: 5.2 | |

| Notes | Remedication allowed after 1 hour. Last score prior to remedication was used for the duration of the study. 212 patients data were analysed. 91 excluded: 48 did not medicate, 17 missed readings, 9 lost to follow‐up, 4 remedicated at < 1 hour, 3 remedicated with slight pain, 4 uninterpretable data, 2 took other medication, 2 did not receive study medicine, 1 lost form. No serious adverse effects were reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene: 10/50 patients reported 10 adverse effects Placebo: 5/56 patients reported 5 adverse events QS = 5 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Coutinho 1976.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, local anaesthetic. Assessed by observer at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 5 hours. Medication taken when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Urogenital surgery n = 90 (30 relevant patients) Age: adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n = 15 Placebo, n = 15 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) nonstandard Dextropropoxyphene was not significantly better than placebo (P not given) Mean SPID @ 5 hrs: Dextropropoxyphene :4.5 Placebo: 3.3 | |

| Notes | Remedication allowed at 4 hours if no pain relief. If remedicated before 4 hours patients were withdrawn from the study. There were no exclusions or withdrawals. No serious adverse effects were reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene: 1/15 patients reported 1 adverse event Placebo: 0/15 QS = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Evans 1982.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, general anaesthetic. Assessed by same nurse observer at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 4 hrs. Medication given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Minor orthopaedic surgery n = 120 Age: Adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 30 Placebo, n = 30 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) standard Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol was significantly better than placebo (P < 0.05) for TOTPAR 4 hr TOTPAR: Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 7.37 Placebo: 4.70 | |

| Notes | If remedicated before 4 hrs, last PI and PR score prior to remedication were used for all further time points. 120 participants data were analysed. No withdrawals were reported. No serious adverse events were reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 16/30 patients reported 16 adverse events. Placebo: 13/30 patients reported 13 adverse events. QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Honig 1981.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups. Assessed by nurse observer at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 6 hrs. Medication given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Postoperative ‐ primarily orthopaedic surgery n = 196 Age: 19 ‐ 74 | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 50 Placebo, n = 48 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) nonstandard Global evaluation by patient at 5 hrs (5 point) Combination of dextropropoxyphene with paracetamol was significantly better than placebo (P < 0.05) for SPID & TOTPAR. 6 hr TOTPAR: Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 8.04 Placebo: 5.49 | |

| Notes | If patient remedicated within 6 hrs patient's overall rating of the drug was taken at time of remedication. 196 patients data were analysed. No withdrawals were reported. Authors did not give details of adverse events but reported that there was no significant difference between active and placebo groups. QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Moore 1997.

| Methods | Individual patient data from 18 Double blind, RCTs. Study duration 8 hrs. Single oral dose, parallel groups. Medication was given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Dental + general surgery n = 638 Age: Adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 316 Placebo, n = 322 | |

| Outcomes | Number of patients with at least 50% of maxTOTPAR Dextropropoxyphene napsylate 100 mg + paracetamol 650 mg, n = 112/316 Placebo, n = 41/322 | |

| Notes | No remedication, withdrawals or exclusions were reported. No serious adverse events were reported & no patients withdrew as a result. Dextropropoxyphene + paracetamol: 88/316 patients reported adverse events. Placebo: 66/322 patients reported adverse events. Significantly higher incidence of adverse events with active treatment than placebo for; Dizziness: RR 2.0 (1.1 ‐ 4.0) Drowsiness/somnolence: RR 2.16 (1.5 ‐ 3.2) QS = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Trop 1979.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, single oral dose, parallel groups, local anaesthetic. Assessed by observer at 0, 1/2, 1 hr then hourly for 5 hours. Medication taken when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Postoperative pain ‐ various procedures n= 125 Age: 18 ‐ 73 | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n = 25 Dextropropoxyphene HCl 130 mg, n = 25 Placebo, n = 25 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR (5 point scale) standard Dextropropoxyphene 130 mg was significantly better than placebo (P < 0.01). SPID and TOTPAR given at 6 hours. TOTPAR: Dextropropoxyphene 65 mg: 8.54 Dextropropoxyphene 130 mg: 9.03 Placebo: 2.68 | |

| Notes | Did not state minimum time allowed for remedication. If remedicate last PR score before remedication was used for all further time points. 78 patients data were analysed. 47 were excluded due to "protocol violation". Authors reported a significant difference from placebo for CNS AEs (P= 0.05). None serious & no withdrawals. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg: 19/25 patients reported 27 adverse events. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 130 mg:23/25 patients reported 34 adverse events. Placebo:10/25 patients reported 12 adverse events. QS = 3 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

Van Staden 1971.

| Methods | RCT, Double blind, crossover design, general anaesthetic. Self‐assessed at 1 hour then hourly for 8 hrs. Medication given when pain of moderate to severe intensity. | |

| Participants | Gynaecological surgery n = 91 Age: adult | |

| Interventions | Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg, n = 26 Placebo, n = 29 | |

| Outcomes | PI (4 point scale) standard PR measured as PID (pain intensity difference) Dextropropoxyphene was not significantly better than placebo (P not given). SPID at 4 hrs: Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg: 1.64 Placebo: 1.57 | |

| Notes | Remedication allowed after 1 hour if no pain relief. PR scored as zero for all subsequent time points. 80 patients data were analysed. 11 excluded: 6 violated protocol, 2 vomited, 3 had insufficient pain. Authors reported a significant difference from placebo for CNS adverse events (P= 0.05). None serious & no withdrawals. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 65 mg: 19/25 patients reported 27 adverse events. Dextropropoxyphene HCl 130 mg:23/25 patients reported 34 adverse events. Placebo:10/25 patients reported 12 adverse events. QS = 4 | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | A ‐ Adequate |

QS = quality score PR ‐ pain relief PI ‐ pain intensity CNS ‐ central nervous system

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Berdon 1964 | Intervention given irrespective of baseline pain. Participants included children. Multiple dose regimen with no separate analysis of initial dose. 3 point pain and duration scales used after 48 hrs ‐ not validated for the data extraction method used. |

| Chilton 1961 | Baseline pain of moderate to severe intensity not established, multiple doses of intervention taken 4 hourly "when necessary". Global evaluation of efficacy of first and subsequent doses estimated by patient 48 hrs after surgery on a binary scale (analgesia or no analgesia). |

| Finch 1971 | Included patients with mild baseline pain. Non standard pain scale and calculation of results. |

| Forbes 1982 | Pain measured over 12 hours. Data presented as 12 hour SPID and TOTPAR. No other data given to allow calculation of values at 4 to 6 hours. |

| Gruber 1977 | Does not report whether the patients had pain of at least moderate intensity on entering the trial or the pain scales used. |

| Hellem 1979 | The first tablet was taken immediately after the dental surgery before the local anaesthetic had worn off. Therefore the included patients did not have established pain of at least moderate intensity. |

| Hopkinson 1973 | 5 point pain intensity scale and 5 point pain relief scale (including "worse") neither of which are validated for the data extraction method used. Global evaluation was the opinion of the investigators rather than the patient. |

| Hopkinson 1976 | 5 point pain intensity scale and 5 point pain relief scale (including "worse") neither of which are validated for the data extraction method used. Global evaluation was the opinion of the investigators rather than the patient. |

| Hopkinson 1980 | 5 point pain intensity scale and 5 point pain relief scale (including "worse") neither of which are validated for the data extraction method used. Global evaluation was the opinion of the investigators rather than the patient. |

| Liashek 1987 | First dose was administered pre‐operatively, data was provided for the second dose which was administered when pain was at least moderate but as a cumulative effect cannot be ruled out data from second doses was not included in the analysis. |

| Petti 1985 | Only single blind |

| Prockop 1960 | Analgesic regimen was prescribed as routine irrespective of baseline pain. |

| Reiss 1961 | Interventions administered irrespective of patient's baseline pain; "469 capsules were given when patients were pain free". |

| Rejman 1967 | Baseline pain levels were not defined, patient inclusion was based on the surgeon's preoperative judgement as to whether the patient would require postoperative analgesia. |

| Sadove 1961 | Included patients with baseline pain defined as "slight". |

| Scopp 1967 | Included patients with mild baseline pain. |

| Shiba 1972 | Included patients with light (mild) baseline pain. Also assessed patients 1 week after the study medication had been administered. |

| Smith 1975 | 5 point pain intensity scale and 5 point pain relief scale (including "worse") neither of which are validated for the data extraction method used. Global evaluation was the opinion of the investigators rather than the patient. |

| Valentine 1959 | Did not specify moderate to severe baseline pain. Used 3 point pain relief scales at unknown intervals to gauge outcome, therefore cannot extract any data. |

| Van Bergen 1960 | "No attempt was made to determine hourly pain scores." Therefore no extractable data available. Also does not state the level of baseline pain. |

| Winter 1973 | Included patients with baseline pain of mild intensity. |

| Winter 1978 | Did not state patients had baseline pain of at least moderate intensity. Also used 3 point pain relief scale not validated for the data extraction method. |

| Young 1978 | Included patients with mild to moderate baseline pain. |

Contributions of authors

Original review SC: involved with searching, data extraction, analysis and writing. JR: involved with data extraction, analysis and writing. AM and HJM: involved with analysis and writing.

Update 2008 SD and AM: carried out the searching, data extraction and analysis, and writing.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Oxford Pain Research Funds, UK.

External sources

Biotechnology & Biological Sciences Research Council, UK.

European Union Biomed 2, UK.

SmithKline Beecham Consumer Healthcare, UK.

NHS Research and Development Health Technology Evaluation Programmes, UK.

NHS Cochrane Collaboration Programme Grant Scheme, UK.

Declarations of interest

SC and SD have no interests to declare. RAM has been a consultant for MSD. RAM and HJM have consulted for various pharmaceutical companies. RAM, HJM and JR have received lecture fees from pharmaceutical companies related to analgesics and other healthcare interventions. All authors have received research support from charities, government and industry sources at various times: no such support was received for this work.

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

Berry 1975 {published data only}

- Berry FN, Miller JM, Levin HM, Bare WW, Hopkinson JH, Feldman AJ. Relief of severe pain with acetaminophen in a new dose formulation versus propoxyphene hydrochloride 65mg and placebo: a comparative double blind study. Current Therapeutic Research 1975;17(4):361‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bloomfield 1980 {published data only}

- Bloomfield SS, Barden TP, Mitchell J. Nefopam and propoxyphene in episiotomy pain. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1980;27(4):502‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1980 {published data only}

- Cooper SA. Double‐blind comparison of zomepirac sodium, propoxyphene/acetaminophen, and placebo in the treatment of oral surgical pain. Current Therapeutic Research 1980;28(5):630‐8. [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1981 {published data only}

- Cooper SA, Breen JF, Giuliani RL. The relative efficacy of indoprofen compared with opioid‐analgesic combinations. Journal of Oral Surgery 1981;39(1):21‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1986 {published data only}

- Cooper SA, Wagenberg B, Zissu J, Kruger GO, Reynolds DC, Gallegos LT, et al. The analgesic efficacy of Suprofen in peridontal and oral surgical pain. Pharmacotherapy 1986;6(5):267‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Coutinho 1976 {published data only}

- Coutinho A, Bonelli J, Nanci de Carvelho P. A double‐blind study of the analgesic effects of fenbufen, codeine, aspirin, propoxyphene and placebo. Current Therapeutic Research 1976;19(1):58‐65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Evans 1982 {published data only}

- Evans PJD, McQuay HJ, Rolfe M, Sullivan G, Bullingham RES, Moore RA. Zomepirac, placebo and paracetamol/dextropropoxyphene combination compared in orthopaedic postoperative pain. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1982;54(9):927‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Honig 1981 {published data only}

- Honig S, Murray KA. Postsurgical pain: zomepirac sodium, propoxyphene/acetaminophen combination, and placebo. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1981;21(10):443‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997 {published data only}

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single‐patient data meta‐analysis of 3453 postoperative patients: oral tramadol versus placebo, codeine and combination analgesics. Pain 1997;69(3):287‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sunshine A, Olson NZ, Zighelboim I, DeCastro, Minn FL. Analgesic oral efficacy of tramadol hydrochloride in postoperative pain. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics 1992;51(6):740‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Trop 1979 {published data only}

- Trop D, Kenny L, Grad BR. Comparison of nefopam hydrochloride and propoxyphene hydrochloride in the treatment of postoperative pain. Canadian Anaesthetist's Society Journal 1979;26(4):296‐304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van Staden 1971 {published data only}

- Staden MJ. The use of Glifanan in postoperative pain. South African Medical Journal 1971;45(43):1235‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Berdon 1964 {published data only}

- Berdon JK, Strahan JD, Mirza KB, Wade B. The effectiveness of dextropropoxyphene hydrochloride in the control of pain after peridontal surgery. Journal of Periodontology 1964;35:106‐11. [Google Scholar]

Chilton 1961 {published data only}

- Chilton NW, Lewandowski A, Cameron JR. Double blind evaluation of a new analgesic agent in postextraction pain. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1961;242:702‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Finch 1971 {published data only}

- Finch JS, DeKornfeld TJ. Clonixin: a clinical evaluation of a new oral analgesic. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology and New Drugs 1971;11(5):371‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Forbes 1982 {published data only}

- Forbes JA, Foor VM, Bowser MW, Calderazzo JP, Shackleford RW, Beaver WT. A 12‐hour evaluation of the analgesic efficacy of Diflunisal, propoxyphene, a propoxyphene‐acetaminophen combination and placebo in postoperative oral surgery pain. Pharmacotherapy 1982;2(1):43‐9. [Google Scholar]

Gruber 1977 {published data only}

- Gruber CM Jr. Codeine and propoxyphene in postepisiotomy pain. A two dose evaluation. The Journal of the American Medical Association 1977;237(25):2734‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hellem 1979 {published data only}

- Hellem S, Persson G, Freiberg N, Nord PG, Gustafsson B, Huitfeldt B. A model for evaluating the analgesic effect of a new fixed ratio combination analgesic in patients undergoing oral surgery. International Journal of Oral Surgery 1979;8(6):435‐42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hopkinson 1973 {published data only}

- Hopkinson JH, Bartlett FHJr, Steffens AO, McGlumphy TH, Macht EL, Smith M. Acetaminophen versus propoxyphene hydrochloride for relief of pain in episiotomy patients. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1973;13(7):251‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hopkinson 1976 {published data only}

- Hopkinson JH, Blatt G, Cooper M, Levin HM, Berry FN, Cohn H. Effective pain relief: comparative results with acetaminophen in a new dose formulation, propoxyphene napsylate acetaminophen combination, and placebo. Current Therapeutic Research 1976;19(6):622‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hopkinson 1980 {published data only}

- Hopkinson JH. Ibuprofen versus propoxyphene hydrochloride and placebo in the relief of postepisiotomy pain. Current Therapeutic Research 1980;27(1):55‐63. [Google Scholar]

Liashek 1987 {published data only}

- Liashek PJr, Desjardins PJ, Triplett RG. Effect of pretreatment with acetaminophen propoxyphene for oral surgery pain. Journal of Oral Maxillofacial Surgery 1987;45(2):99‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Petti 1985 {published data only}

- Petti A. Postoperative pain relief with pentazocine and acetaminophen: comparison with other analgesic combinations and placebo. Clinical Therapeutics 1985;8(1):126‐33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Prockop 1960 {published data only}

- Prockop LD, Eckenhoff JE, McElroy RC. Evaluation of dextropropoxyphene, codeine and acetylsalicylic compound. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology 1960;16:113‐8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Reiss 1961 {published data only}

- Reiss R, Aufses AH. Dextropropoxyphene versus meperidine; an evaluation of analgesic activity of these hydrochlorides in postoperative patients. Archives of Surgery 1961;62:429‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rejman 1967 {published data only}

- Rejman F, Mattsson T. The effects of Doleron in postoperative pain [Doleron postoperatiivisissa kivuissa]. Duodecim: Laaketieteellinen Aikakauskirja 1967;83(24):1427‐34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sadove 1961 {published data only}

- Sadove MS, Schiffrin MJ, Ali SM. A controlled study of codeine, dextropropoxyphene and RO 4‐1778/1. The American Journal of the Medical Sciences 1961;241:103‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Scopp 1967 {published data only}

- Scopp IW, Morgan FH, Gillette WB, Fredrics HJ, Peskin MJ, Kleinman D. Dialog. A double‐blind clinical study of Dialog, Darvon and a placebo in the management of postoperative dental pain. Journal of Oral Therapeutics and Pharmacology 1967;4:123‐7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shiba 1972 {published data only}

- Shiba R, Nakajo N, Goto S, Kodama H. [Analgesic effects of d propoxyphene napsylate for the pain following tooth extraction comparison of Sedes and placebo in the double blind study]. Masui. The Japanese Journal of Anesthesiology 1972;21(1):32‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Smith 1975 {published data only}

- Smith MT, Levin HM, Bare WW, Berry FN, Miller JM. Acetaminophen extra strength capsules versus propoxyphene compound 65 versus placebo: a double blind study of effectiveness and safety. Current Therapeutic Research 1975;17(5):452‐9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Valentine 1959 {published data only}

- Valentine G, Martin SJ. D‐Propoxyphene hydrochloride (Darvon) in preanesthetic and postanesthetic management. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1959;38(1):50‐5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Van Bergen 1960 {published data only}

- Bergen WS, North WC, Karp M. Effect of dextropropoxyphene, meperidine, and codeine on postoperative pain. The Journal of the American Medical Association 1960;172(13):1372‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Winter 1973 {published data only}

- Winter L Jr, Calman HI, Caruso WA, Post A. A double blind comparison of ethoheptazine citrate, propoxyphene hydrochloride, and placebo. Current Therapeutic Research 1973;15(7):383‐90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Winter 1978 {published data only}

- Winter LJr, Bass E, Recant B, Cahaly JF. Analgesic activity of ibuprofen (Motrin) in postoperative oral surgical pain. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, and Oral Pathology 1978;45(2):159‐66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Young 1978 {published data only}

- Young RES. A two‐dose evaluation of propoxyphene napsylate and codeine in postoperative pain. Current Therapeutic Research 1978;24(5):495‐502. [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Bruster 1994

- Bruster S, Jarman B, Bosanquet N, Weston D, Erens R, Delbanco TL. National survey of hospital patients. British Medical Journal 1994;309(6968):1542‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Collins 1998b

- Collins SL, Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Wiffen PJ. Oral ibuprofen and diclofenac in postoperative pain: a quantitative systematic review. European Journal of Pain 1998;2:285‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook 1995

- Cook RJ, Sackett DL. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. British Medical Journal 1995;310:452‐4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cooper 1991

- Cooper SA. Single‐dose analgesic studies: the upside and downside of assay sensitivity. In: Max MB, Portenoy RK, Laska EM editor(s). The Design of Analgesic Clinical Trials (Advances in Pain Research and Therapy Vol. 18). New York: Raven Press, 1991:117‐124. [Google Scholar]

Gardner 1986

- Gardner MJ, Altman DG. Confidence intervals rather than p values: estimation rather than hypothesis testing. British Medical Journal 1986;292:746‐50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

GSS 1996

- Government Statistical Service. Prescription Cost Analysis for England 1995. London: Department of Health, 1996. [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996a

- Jadad AR, Carroll D, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Developing a database of published reports of randomised clinical trials in pain research. Pain 1996;66:239‐46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jadad 1996b

- Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJM, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary?. Controlled Clinical Trials 1996;17:1‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lasagna 1962

- Lasagna L. The psychophysics of clinical pain. Lancet 1962;2:572‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1996

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics. Pain 1996;66(2‐3):229‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997a

- Moore RA, McQuay HJ, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: Verification from independent data. Pain 1997;69(1‐2):127‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997b

- Moore RA, Moore O, McQuay HJ, Gavaghan D. Deriving dichotomous outcome measures from continuous data in randomised controlled trials of analgesics: Use of pain intensity and visual analogue scales. Pain 1997;69(3):311‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 1997c

- Moore RA, Collins SL, Carroll D, McQuay HJ. Paracetamol with and without codeine in acute pain: a quantitative systematic review. Pain 1997;70:193‐201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Moore 2005

- Moore RA, Edwards JE, McQuay HJ. Acute pain: Individual patient meta‐analysis shows the impact of different ways of analysing and presenting results. Pain 2005;116:322‐31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

Collins 1998a

- Collins SL, Edwards J, Moore RA, McQuay HJ. Single dose dextropropoxyphene in postoperative pain: a quantitative systematic review. European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 1998;54:107‐12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McQuay 1998

- McQuay HJ, Moore RA. An Evidence‐Based Resource for Pain Relief. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]