Abstract

Background:

Salmonella is a major bacterial pathogen transmitted commonly through food. Increasing resistance to antimicrobial agents (e.g., ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin) used to treat serious Salmonella infections threatens the utility of these agents. Infection with antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella has been associated with increased risk of severe infection, hospitalization, and death. We describe changes in antimicrobial resistance among nontyphoidal Salmonella in the United States from 1996 through 2009.

Methods:

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System conducts surveillance of resistance among Salmonella isolated from humans. From 1996 through 2009, public health laboratories submitted isolates for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. We used interpretive criteria from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute and defined isolates with ciprofloxacin resistance or intermediate susceptibility as nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin. Using logistic regression, we modeled annual data to assess changes in antimicrobial resistance.

Results:

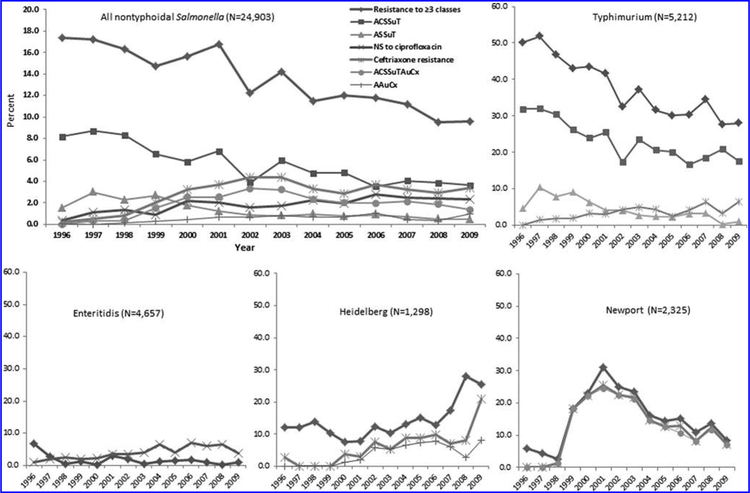

From 1996 through 2009, the percentage of nontyphoidal Salmonella isolates resistant to ceftriaxone increased from 0.2% to 3.4% (odds ratio [OR] = 20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6.3–64), and the percentage with nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin increased from 0.4% to 2.4% (OR = 8.3, 95% CI 3.3–21). The percentage of isolates that were multidrug resistant (resistant to ≥ 3 antimicrobial classes) decreased from 17% to 9.6% (OR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.5–0.7), which was driven mainly by a decline among serotype Typhimurium. However, multidrug resistance increased from 5.9% in 1996 to a peak of 31% in 2001 among serotype Newport and increased from 12% in 1996 to 26% in 2009 (OR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) among serotype Heidelberg.

Conclusions:

We describe an increase in resistance to ceftriaxone and nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin and an overall decline in multidrug resistance. Trends varied by serotype. Because of evidence that antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella is predominantly a consequence of antimicrobial use in food animals, efforts are needed to reduce unnecessary use, especially of critically important agents.

Introduction

EACH YEAR IN THE UNITED STATES, nontyphoidal Salmonella is estimated to cause 1.2 million illnesses, with 23,000 hospitalizations and 450 deaths (Scallan et al., 2011). Five serotypes (Enteritidis, Typhimurium, Newport, Javiana, and Heidelberg) typically account for about half of laboratory-confirmed illnesses (CDC, 2005–2009). The predominant serotypes reflect their different abilities to persist in animals, be transmitted through the food supply, and cause human illness (McDermott, 2006; Jones et al., 2008). Infections have been linked to a variety of food sources, particularly foods of animal origin (e.g., beef, poultry, eggs, dairy products), and fruits and vegetables consumed raw (Braden, 2006; Varma et al., 2006; CDC, 2006; Greene et al., 2008; CDC, 2011a).

Most nontyphoidal Salmonella infections result in gastroenteritis and do not require treatment with antimicrobial agents. However, these agents are essential for the treatment of invasive infections such as bacteremia and meningitis (Pegues and Miller, 2010). Fluoroquinolones, such as ciprofloxacin, are frequently prescribed as first-line treatment for adults with severe infections (Crump et al., 2003; Pegues and Miller, 2010). Because fluoroquinolones are not routinely prescribed for children, ceftriaxone, a third-generation ceph-alosporin, is important in the management of invasive infections in children (Gupta et al., 2003; Pegues and Miller, 2010). Increasing resistance threatens the utility of these agents. Infection with antimicrobial-resistant Salmonella has been associated with increased risk of severe infection, hospitalization, and death (Helms et al., 2004; Fisk et al., 2005; Varma et al., 2005a; Varma et al., 2005b). Multidrug resistance further complicates management by limiting treatment options. We describe an increase in resistance to ceftriaxone and nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin among nontyphoidal Salmonella. We describe an overall decline in multidrug resistance, although we note an increase among some serotypes and an increase in specific resistance patterns.

Methods

Participating sites and isolate submission

Public health laboratories routinely receive human Salmonella isolates from clinical diagnostic laboratories as part of public health surveillance. Isolates are confirmed as Salmonella and serotyped according to the Kaufmann-White Scheme at public health laboratories (WHO, 2007). Established in 1996, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS) is a collaboration between the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), U.S. Department of Agriculture, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and state and local health departments to monitor resistance among Salmonella and other foodborne bacteria (CDC, 2012). In 1996, 13 states participated; by 2003, NARMS included 50 states (Table 1). Sites submitted every 10th isolate from 1996 through 2002 and every 20th from 2003 through 2009.

TABLE 1.

PARTICIPATING STATES IN THE NATIONAL ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE MONITORING SYSTEM, BY YEAR, 1996–2009

| Year | No. statesa | New sites |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 13 | California (Alameda, Los Angeles, and San Francisco counties), Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Kansas, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York (Bronx, Brooklyn, New York, Queens, and Richmond counties), Oregon, Washington, and West Virginia |

| 1997 | 14 | Maryland |

| 1999 | 15 | Tennessee |

| 2002 | 26 | Arizona, Hawaii, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, South Dakota, Texas (excluding Houston), and Wisconsin; New York began statewide participation |

| 2003 | 50 | Alaska, Alabama, Arkansas, Delaware, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Mississippi, North Carolina, North Dakota, New Hampshire, Nevada, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Virginia, Vermont, Wyoming, remaining counties in California, and Houston |

| 2008 | 50 | District of Columbia |

| 2009 | 50 |

Represented by state and local health departments and their public health laboratories.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

At CDC, isolates were tested for susceptibility to antimicrobial agents representing eight classes (CDC, 2012; CLSI, 2012): aminoglycosides, β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations, cephems, folate pathway inhibitors, penicillins, phenicols, quinolones, and tetracyclines. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) were determined using a broth microdilution method (Sensititre, Trek Diagnostics, Westlake, OH). We used interpretive criteria from the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) when available (CDC, 2012; CLSI, 2012). Ceftriaxone resistance was defined as MIC ≥ 4 μg/mL and ceftiofur resistance as MIC ≥ 8 μg/mL. In January 2012, CLSI established new ciprofloxacin MIC interpretive criteria for extraintestinal Salmonella spp. We used the new criteria for all isolates; resistance was defined as MIC ≥ 1 μg/mL, intermediate as MIC = 0.12–0.5 μg/mL, and susceptible as MIC ≥ 0.06 μg/mL. We defined isolates that were resistant or intermediate as nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Except for analyses of nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin, isolates were categorized as resistant or not resistant (susceptible or intermediate). We included 15 agents in the analysis of antimicrobial class resistance. Multidrug resistance (MDR) was defined as resistance to ≥ 3 classes. Among isolates with MDR, we identified the most common patterns based on seven agents: ampicillin (A), chloramphenicol (C), streptomycin (S), sulfonamide (Su), tetracycline (T), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Au), and ceftriaxone (Cx). These seven agents were chosen because MDR patterns (e.g., ACSSuTAuCx, ACSSuT, AAuCx) that include many of them have been associated with more severe Salmonella infections (Gupta, et al. 2003; Fisk et al., 2005), and these agents represent seven of eight classes tested. The patterns as assigned were mutually exclusive. A chi-square test was used to test for association with resistance/nonsusceptibility patterns. Typhoidal Salmonella isolates (serotypes Typhi, Paratyphi A, Paratyphi B [tartrate negative], and Paratyphi C) were excluded in the analysis. Hereafter, the term Salmonella refers to nontyphoidal Salmonella. Using logistic regression, we modeled annual data from 1996 through 2009 to assess changes in resistance (Kleinbaum et al., 2008; CDC, 2012). Only the comparisons between 1996 and 2009 are presented. Except where noted, regression models were adjusted for the submitting site using nine regions (CDC, 2012): East North Central, East South Central, Mid-Atlantic, Mountain, New England, Pacific, South Atlantic, West North Central, and West South Central. For calculations of the percentage of a serotype with a given resistance pattern, only serotypes with at least three isolates with that pattern were included.

Results

From 1996 through 2009, 24,903 nontyphoidal Salmonella isolates were tested; the most common serotypes were Typhimurium (21%), Enteritidis (19%), Newport (9%), and Heidelberg (5%). Of 22,532 (90%) patients with reported age, 9% were < 1 year old, 19% 1–4 years, 9% 5–9 years, 10% 10–19 years, 39% 20–59 years, and 14% ≥ 60 years. Of 23,199 (93%) patients for whom sex was known, 52% were female. Of 24,248 isolates (97%) with reported specimen source, 88% were from stool, 5% from blood, 4% from urine, and 3% from other or undefined sources.

Resistance to ceftriaxone

Among the 24,903 isolates, 730 (2.9%) were resistant to ceftriaxone. They were of 40 serotypes; most were Newport (45%), Typhimurium (25%), or Heidelberg (11%) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

NUMBER AND PERCENTAGEa OF NONTYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA ISOLATES WITH SELECTED RESISTANCE PATTERNS, BY SEROTYPE,b 1996–2009

| Resistance to ceftriaxonec (MIC ≥4μg/mL) (N = 730) | Nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacind (MIC ≥0.12μg/mL) (N = 482) | Resistance to ≥ 3 antimicrobial classes (N=3247) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotype | No. | % R | % Serotype | Serotype | No. | % R or % I | % Serotype | Serotype | No. | % R | % Serotype |

| Newport | 331 | 45 | 14 | Resistant (R): | Typhimurium | 1935 | 60 | 37 | |||

| Typhimurium | 184 | 25 | 3.5 | Senftenberg | 15 | 38 | 13 | Newport | 379 | 12 | 16 |

| Heidelberg | 81 | 11 | 6.2 | Typhimurium | 6 | 15 | 0.1 | Heidelberg | 182 | 5.6 | 14 |

| Agona | 28 | 3.8 | 7.5 | Litchfield | 4 | 10 | 2.9 | Enteritidis | 78 | 2.4 | 1.7 |

| I 4,[5],12:i:- | 16 | 2.2 | 3.1 | Schwarzengrund | 3 | 7.5 | 2.2 | Hadar | 64 | 2.0 | 22 |

| Enteritidis | 10 | 1.4 | 0.2 | Stanley | 52 | 1.6 | 29 | ||||

| Dublin | 8 | 1.1 | 12 | Intermediate (I): | Paratyphi B var. L( + ) tartrate + | 48 | 1.5 | 13 | |||

| Infantis | 8 | 1.1 | 2.0 | Enteritidis | 186 | 42 | 4.0 | Agona | 46 | 1.4 | 12 |

| Saintpaul | 6 | 0.8 | 1.1 | Typhimurium | 57 | 13 | 1.1 | I 4,[5],12:i:- | 41 | 1.3 | 8.0 |

| Concord | 5 | 0.7 | 71 | Virchow | 36 | 8.1 | 43 | Montevideo | 35 | 1.1 | 5.4 |

| Reading | 4 | 0.5 | 9.5 | Hadar | 10 | 2.3 | 3.4 | Derby | 34 | 1.0 | 34 |

| Mbandaka | 3 | 0.4 | 2.0 | Agona | 8 | 1.8 | 2.2 | Saintpaul | 32 | 1.0 | 5.7 |

| Senftenberg | 3 | 0.4 | 2.6 | Blockley | 8 | 1.8 | 20 | Dublin | 28 | 0.9 | 42 |

| Uganda | 3 | 0.4 | 5.9 | Infantis | 8 | 1.8 | 2.0 | Infantis | 19 | 0.6 | 4.8 |

| Newport | 8 | 1.8 | 0.3 | Senftenberg | 17 | 0.5 | 15 | ||||

| Berta | 7 | 1.6 | 4.4 | Berta | 14 | 0.4 | 8.8 | ||||

| Corvallis | 7 | 1.6 | 88 | Virchow | 14 | 0.4 | 17 | ||||

| Heidelberg | 6 | 1.4 | 0.5 | Muenchen | 12 | 0.4 | 2.2 | ||||

| Saintpaul | 6 | 1.4 | 1.1 | Blockley | 10 | 0.3 | 25 | ||||

| laviana | 5 | 1.1 | 0.5 | Choleraesuis | 7 | 0.2 | 58 | ||||

| Stanley | 5 | 1.1 | 2.8 | laviana | 7 | 0.2 | 0.7 | ||||

| I 4,[5],12:i:- | 4 | 0.9 | 0.8 | Schwarzengrund | 7 | 0.2 | 5.0 | ||||

| Montevideo | 4 | 0.9 | 0.6 | Bovismorbificans | 6 | 0.2 | 11 | ||||

| Uganda | 4 | 0.9 | 7.8 | Reading | 6 | 0.2 | 14 | ||||

| Bareilly | 3 | 0.7 | 2.3 | Bredeney | 5 | 0.2 | 14 | ||||

| Choleraesuis | 3 | 0.7 | 25 | Concord | 5 | 0.2 | 71 | ||||

| Concord | 3 | 0.7 | 43 | Kentucky | 5 | 0.2 | 11 | ||||

| Dublin | 3 | 0.7 | 4.5 | Thompson | 5 | 0.2 | 1.3 | ||||

| Mbandaka | 3 | 0.7 | 2.0 | Brandenburg | 4 | 0.1 | 5.0 | ||||

| Schwarzengrund | 3 | 0.7 | 2.2 | Chester | 4 | 0.1 | 17 | ||||

| Thompson | 3 | 0.7 | 0.8 | Litchfield | 4 | 0.1 | 2.9 | ||||

| Mbandaka | 4 | 0.1 | 2.7 | ||||||||

| Muenster | 4 | 0.1 | 6.8 | ||||||||

| Uganda | 4 | 0.1 | 7.8 | ||||||||

| Anatum | 3 | 0.1 | 1.8 | ||||||||

| Corvallis | 3 | 0.1 | 38 | ||||||||

| Mississippi | 3 | 0.1 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| Ohio | 3 | 0.1 | 5.7 | ||||||||

Percentage of total isolates with resistance pattern (% R or % I) and percentage of the serotype with resistance pattern (% serotype).

Data are not shown for additional serotypes with < 3 resistant isolates: 26 serotypes (34 isolates) plus 6 isolates of unknown serotypes were resistant to ceftriaxone, 9 serotypes (11 isolates) plus 1 isolate of unknown serotype were resistant to ciprofloxacin; 33 serotypes (42 isolates) plus 10 isolates of unknown serotypes had intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, and 47 serotypes (60 isolates) plus 58 isolates of unknown serotypes were resistant to ≥ 3 classes.

The same 14 serotypes with ≥ 3 ceftriaxone-resistant isolates also had ≥ 3 ceftiofur-resistant isolates. Of 741 isolates resistant to ceftriaxone or ceftiofur, 15 were resistant to only 1 of the 2 agents; 11 were resistant to only ceftiofur and 4 to only ceftriaxone. Except for Enteritidis and Senftenberg, > 98% of isolates resistant to 1 agent among these serotypes were resistant to the other agent. Among Enteritidis and Senftenberg, although all ceftriaxone-resistant isolates were resistant to ceftiofur, only 77% (10/13) of ceftiofur-resistant isolates among Enteritidis and 75% (3/4) among Senftenberg were resistant to ceftriaxone.

The 482 isolates include 40 that were resistant (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] ≥ 1 μg/mL) and 442 with intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin (MIC= 0.12–0.5 μg/mL). Of the 40 ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates, 33 (83%) were resistant and 7 (17%) were susceptible to nalidixic acid. Of the 442 ciprofloxacin-intermediate isolates, 382 (86%) were resistant and 60 (14%) were susceptible to nalidixic acid. The 67 isolates that were nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin and susceptible to nalidixic acid were of 25 serotypes; most were Typhimurium (25%), Enteritidis (12%), Corvallis (10%), or Litchfield (7%).

Resistance to ceftriaxone was most common among serotypes Concord (71% of this serotype) and Newport (14%). Among Salmonella, ceftriaxone resistance increased from 0.2% in 1996 to 3.4% in 2009 (odds ratio [OR] = 20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 6.3–64); it peaked at 4.4% in 2002 and 2003 (Table 3, Fig. 1). Resistance in Newport isolates was found in 0% in 1996 and increased to 7.1% in 2009; it peaked at 25% in 2001. Among serotype Typhimurium isolates, resistance increased from 0% in 1996 to 6.5% in 2009 (95% CI 6.6–infinity). Among serotype Heidelberg isolates, resistance increased from 2.7% in 1996 to 8.0% in 2008, then jumped to 21% in 2009 (1996 vs. 2009; OR = 9.4, 95% CI 2.1–87) (Table 3, Figure 1). Of 24 resistant Typhimurium isolates in 2009, 6 (25%) were from California. Of 18 resistant Heidelberg isolates in 2009, 9 (50%) were from California and 3 (17%) were from Washington.

TABLE 3.

TRENDS IN SELECTED RESISTANCE PATTERNS AMONG ALL NONTYPHOIDAL SALMONELLA AND THE FOUR MOST COMMONLY ISOLATED SEROTYPES: 1996 VS. 2009

| Resistance pattern | Serotype | % Resistance | Odds ratioa | 95% CIa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1966 | 2009 | ||||

| Resistance to ceftriaxone (MIC ≥ 4 µg/mL) | All | 0.2 | 3.4 | 20 | 6.3–64 |

| Typhimurium | 0 | 6.5 | —b | 6.6-infinity | |

| Newport | 0 | 7.1 | —b | 1.2-infinity | |

| Heidelberg | 2.7 | 21 | 9.4b | 2.1–87 | |

| Nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin | All | 0.4 | 2.4 | 8.3 | 3.3–21 |

| (MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/mL) | Enteritidis | 0.9 | 3.7 | 5.3 | 1.5–19 |

| Resistance to ≥ 3 antimicrobial classesc | All | 17 | 9.6 | 0.6 | 0.5–0.7 |

| Typhimurium | 50 | 28 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 | |

| Enteritidis | 6.8 | 1.0 | 0.1b | 0.03–0.4 | |

| Newport | 5.9 | 8.4 | 3.1 | 0.9–11 | |

| Heidelberg | 12 | 26 | 2.6 | 1.1–6.2 | |

| ACSSuTc | All | 8.2 | 3.6 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.6 |

| Typhimurium | 32 | 18 | 0.5 | 0.3–0.7 | |

| ACSSuTAuCxc | All | 0 | 1.4 | —b | 5.8-infinity |

| Newport | 0 | 7.1 | —b | 1.2-infinity | |

| ASSuTc | All | 1.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.2–0.8 |

| Typhimurium | 4.6 | 1.1 | 0.3 | 0.1–0.9 | |

| SSuTc | All | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.3–1.5 |

| Typhimurium | 2.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.2–2.5 | |

| AAuCxc | All | 0.1 | 1.0 | 18 | 2.3–131 |

| Heidelberg | 0 | 8.1 | —b | 1.7-infinity | |

Odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) that do not include 1.0 are reported as statistically significant.

Models include year but not site because of small numbers; ORs and 95% CIs were calculated using exact unconditional methods. In the analysis where the maximum likelihood estimate of the ORs did not exist, only the 95% CIs are reported.

Antimicrobial classes defined by the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute were used to categorize 15 agents: aminoglycosides (amikacin, gentamicin, kanamycin, streptomycin [S]), β-lactam/β-lactamase inhibitor combinations (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid [Au]), cephems (cefoxitin, ceftiofur, ceftriaxone [Cx]), folate pathway inhibitors (sulfonamide [Su], trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole), penicillins (ampicillin [A]), phenicols (chloramphenicol [C]), quinolones (ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid), and tetracyclines (tetracycline [T]).Multidrug resistance patterns were defined based on resistance to the seven agents: A, C, S, Su, T, Au, and Cx. Resistance to any of the other agents tested may be present.

MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration.

FIG. 1.

Percentage of selected resistance patterns among all nontyphoidal Salmonella isolates and the four most commonly isolated serotypes, by year, 1996–2009. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) interpretive criteria (when available) for resistance and classes of antimicrobial agents defined by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute were used. Nonsusceptibility (NS) to ciprofloxacin was defined as MIC ≥ 0.12 μg/mL. Multidrug resistance patterns were based on resistance to 7 of 15 agents: ampicillin (A), chloramphenicol (C), streptomycin (S), sulfonamide (Su), tetracycline (T), amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (Au), and ceftriaxone (Cx), e.g., ACSSuT includes resistance to A, C, S, Su, and T, and no resistance to Au and Cx. Resistance to the other agents may be present.

Ceftiofur resistance also increased and was correlated with ceftriaxone resistance (p < 0.01). Among all isolates, 737 (3.0%) were resistant to ceftiofur; 99% of the ceftiofur-resistant isolates were resistant to ceftriaxone (Table 2).

Resistance and nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin

Among the 24,903 isolates, 40 (0.2%) were resistant to ciprofloxacin. They were of 13 serotypes; most were Senftenberg (38%), Typhimurium (15%), or Litchfield (10%), and no other serotype comprised ≥ 10% of resistant isolates (Table 2). Serotypes with the highest proportion of isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin were Senftenberg (13%) and Litchfield (2.9%). In addition, 442 (1.8%) isolates had intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. They were of 57 serotypes; most were Enteritidis (42%), Typhimurium (13%), or Virchow (8.1%). However, only 4.0% of Enteritidis isolates had intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin. Serotypes for which a high proportion of isolates had intermediate susceptibility were Corvallis (88%), Virchow (43%), Concord (43%), Choleraesuis (25%), and Blockley (20%) (Table 2). Among Salmonella, nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin increased from 0.4% in 1996 to 2.4% in 2009 (OR = 8.3, 95% CI 3.3–21). Among serotype Enteritidis isolates, the percentage increased from 0.9% in 1996 to 3.7% in 2009 (OR = 5.3, 95% CI 1.5–19); it peaked at 7.0% in 2006 (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Nalidixic acid resistance also increased and was correlated with nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin (p < 0.01). Among all isolates, 445 (1.8%) were resistant to nalidixic acid; 93% of the nalidixic acid–resistant isolates were nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin (Table 2).

Three Senftenberg and 1 Typhimurium isolates were resistant to both ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone. In addition, 27 isolates of 10 serotypes showed both intermediate susceptibility to ciprofloxacin and ceftriaxone resistance. Only serotype Concord had a high proportion of isolates with this pattern (three isolates; 43% of this serotype); all other serotypes had fewer than 5% of isolates with this pattern.

Multidrug resistance

Among the 24,903 isolates, 3,247 (13%) were MDR (resistant to ≥ 3 classes). These were of 85 serotypes; most were Typhimurium (60%), Newport (12%), or Heidelberg (5.6%) (Table 2). MDR was most common in serotypes Concord (71%), Choleraesuis (58%), Dublin (42%), Corvallis (38%), Typhimurium (37%), Derby (34%), Stanley (29%), Blockley (25%), and Hadar (22%). Overall, MDR decreased from 17% in 1996 to 9.6% in 2009 (OR = 0.6, 95% CI 0.5–0.7) (Table 3, Fig. 1). Among serotype Typhimurium, MDR declined from 50% in 1996 to 28% in 2009 (OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.3–0.6). Among serotype Newport isolates, MDR increased from 5.9% in 1996 to a peak of 31% in 2001, declining to 8.4% in 2009 (Fig. 1). Among serotype Heidelberg isolates, MDR increased from 12% in 1996 to 17% in 2007, jumped to 28% in 2008, and was found in 26% in 2009 (1996 vs. 2009; OR = 2.6, 95% CI 1.1–6.2) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

The five most common MDR phenotypes were ACSSuT (41% of MDR isolates), ACSSuTAuCx (15%), ASSuT (9.1%), SSuT (8.5%), and AAuCx (4.3%). Many of these isolates were also resistant to some of the agents not included in defining resistance patterns.

The 1323 ACSSuT isolates were of 26 serotypes; 90% were Typhimurium. This serotype had the highest percentage of isolates with the ACSSuT pattern (23%). ACSSuT resistance declined from 8.2% in 1996 to 3.6% in 2009 (OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.3–0.6). Among serotype Typhimurium, ACSSuT resistance declined from 32% in 1996 to 18% in 2009 (OR = 0.5, 95% CI 0.3–0.7) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

The 476 ACSSuTAuCx isolates were of 16 serotypes; 68% were Newport. This serotype had the highest percentage of isolates with the ACSSuTAuCx pattern (14%). ACSSuTAuCx resistance increased from 0% in 1996 to 1.4% in 2009 (95% CI 5.8–infinity) (Table 3, Fig. 1). Among serotype Newport, ACSSuTAuCx increased from 0% in 1996 to a peak of 25% in 2001, declining to 7.1% in 2009 (Fig. 1). Most (65%) ceftriaxone-resistant isolates were ACSSuTAuCx. Among serotype Newport, 97% of ceftriaxone-resistant isolates were ACSSuTAuCx.

The 295 ASSuT isolates were of 27 serotypes; 75% were Typhimurium. The serotypes with the highest percentage of ASSuT-resistant isolates were Choleraesuis (25%), Bovismorbificans (5.4%), and Typhimurium (4.2%). The ASSuT pattern declined from 1.5% in 1996 to 0.5% in 2009 (OR = 0.4, 95% CI 0.2–0.8). Among serotype Typhimurium, it declined from 4.6% to 1.1% (OR = 0.3, 95% CI 0.1–0.9) (Table 3, Fig. 1).

The 275 SSuT isolates were of 31 serotypes; most were Typhimurium (27%), Stanley (13%), Derby (10%), or Heidelberg (10%). The serotypes with the highest percentage of SSuT-resistant isolates were Corvallis (38%), Derby (28%), and Stanley (20%). There was no change in SSuT resistance (Table 3, Fig. 1).

The 140 AAuCx isolates were of 18 serotypes; most were serotype Heidelberg (37%) or Typhimurium (36%). The serotype with the highest percentage of AAuCx resistant isolates was Heidelberg (4.0%). AAuCx increased from 0.1% in 1996 to 1.0% in 2009 (OR = 18, 95% CI 2.3–131). Among serotype Heidelberg, AAuCx was first detected in 2000 and increased to 8.1% in 2009 (1996 vs. 2009, 95% CI 1.7–infinity) (Table 3, Fig. 1). Of the 81 ceftriaxone-resistant Heidelberg isolates, 52 (64%) had the AAuCx pattern, and 28 (35%) were resistant to A, Au, Cx, and at least one of the other four agents (C, S, Su, T).

Discussion

We describe an increase in resistance to ceftriaxone and a similar trend in resistance to ceftiofur, a closely related extended-spectrum cephalosporin used in some food animals in the United States (Alcaine et al., 2005; McDermott, 2006). Resistance to ceftriaxone and ceftiofur in Salmonella results from the presence of a plasmid-encoded AmpC-like β-lactamase, CMY-2 (Giles et al., 2004; Alcaine et al., 2005; Whichard et al., 2007). A fivefold increase in the proportion of human Salmonella isolates resistant to extended-spectrum cephalosporins reported from 1998 through 2001 was primarily attributed to the emergence of Newport strains with the ACSSuTAuCx phenotype; cattle on local dairy farms were identified as a reservoir (Gupta et al., 2003). A study of sporadic infections implicated bovine and possibly poultry sources (Varma et al., 2006). In general, sources of susceptible infections appear to be different from those of MDR infections (Greene et al., 2008). Because cattle are a major source of human serotype Newport infections resistant to ACSSuTAuCx, a decline in this MDR pattern in human isolates may be attributed mainly to a decline in ACSSuTAuCx resistance among serotype Newport in cattle (Gupta et al., 2003; NARMS, 2011).

The parallel increase in ceftriaxone resistance and the ACSSuTAuCx pattern observed in serotype Newport has not been observed in Heidelberg, another serotype in which ceftriaxone resistance has increased. In serotype Heidelberg, resistance is mediated by an IncI group of plasmids that appear less prone to acquire multiple resistance genes than the IncA/C plasmids mediating resistance in serotype Newport (Giles et al., 2004; Whichard et al., 2007; Folster et al., 2009). This helps explain our observation that serotype Heidelberg has the highest percentage of isolates with the AAuCx pattern. Infection with serotype Heidelberg has been mainly attributed to consumption of poultry and eggs (McDermott, 2006; Dutil et al., 2010; CDC, 2011b). There is evidence that use of ceftiofur in poultry is contributing to third-generation cephalosporin resistance in human Heidelberg infections (Dutil et al., 2010).

The increase in nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin, which correlates with nalidixic acid resistance, is of concern because it has been associated with increased risk for treatment failure in invasive infections (CLSI, 2012; Crump et al., 2003). It is notable that nonsusceptibility to ciprofloxacin has increased in serotype Enteritidis, which is rarely resistant to other agents (CDC, 2012). Enteritidis was the most common serotype among isolates with this pattern. Shell eggs are a major vehicle for Enteritidis infection (Braden, 2006). Enteritidis infections have also been linked to international travel and to consuming chicken (Kimura et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2011). United Kingdom studies have associated quinolone-resistant infections with foreign travel and consumption of imported foods (Threlfall et al., 2006).

The decline in MDR among Salmonella has been driven mainly by decreased MDR among serotype Typhimurium. However, MDR peaked in serotype Newport in 2001 and has increased in serotype Heidelberg. Of the five most common patterns, ACSSuT and ASSuT have declined, SSuT has not changed, but patterns containing ceftriaxone resistance (i.e., ACSSuTAuCx and AAuCx) have increased. The predominance of ACSSuTAuCx in ceftriaxone-resistant isolates, particularly in serotype Newport, illustrates the accumulation of linked genes on transmissible plasmids (McDermott, 2006). Because MDR plasmids may be maintained by selection pressure from a single agent for which there is resistance, populations carrying these plasmids may be difficult to eradicate. For example, multidrug-resistant Salmonella may be selected for by use of agents that are routinely added to feed or water of healthy food animals, such as tetracyclines (Mellon et al., 2001). Of the five most common MDR patterns, four include tetracycline resistance.

To account for the change in NARMS catchment over time, possible confounding by site, and to assess interaction between site and year, we adjusted for site in most of the regression models. However, because of sparse data, we categorized site by nine regions instead of 50 states (CDC, 2012). Thus, our analysis lacked power to determine the effect of state-to-state variation in resistance. In models that did not adjust for site, reported OR represents a summary of possibly unequal trends across sites. We also did not adjust for multiple comparisons. If illness caused by resistant Salmonella tends to be more severe and thus more likely to receive medical attention, we may have overestimated the percentage of resistant infections. However, this could not have changed the direction of trends in resistance over time.

Identification of rare but worrisome resistance patterns can help alert clinicians and target prevention efforts. We detected resistance to ceftriaxone and ciprofloxacin in four isolates, three of which were serotype Senftenberg (Whichard et al., 2007). An outbreak that involved several health care facilities and affected mostly elderly patients was linked to serotype Senftenberg with this pattern (Kay et al., 2007). Many other serotypes in which a high proportion of isolates had important resistance patterns cause a relatively small proportion of human Salmonella infections (CDC, 2012). These include serotypes Blockley, Choleraesuis, Concord, Corvallis, Derby, Dublin, Hadar, Stanley, and Virchow. However, identifying their reservoirs and determining ways to decrease selective pressure may decrease the likelihood of further emergence of resistant strains and spread of their plasmids.

There is evidence that antimicrobial resistance among Salmonella is predominantly a consequence of antimicrobial use in food animals (Angulo et al., 2004). The FDA has taken steps to contain the spread of antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in food animals and prolong the usefulness of antimicrobial agents. In 2003, the FDA incorporated a qualitative review process into the pre-approval safety assessment of agents for food-producing animals (FDA, 2003). In 2005, the FDA withdrew approval of the fluoroquinolone enrofloxacin from use in poultry (FDA, 2005). In 2012, the FDA introduced restrictions on extra-label use of extended-spectrum cephalosporins in food animals (FDA, 2012a). In 2012, the FDA also announced plans for initiating a strategy for limiting use of important agents in food-producing animals to those that are for therapeutic purposes and are administered under veterinary supervision (FDA, 2012b). These and other approaches are needed to prevent the emergence and spread of resistant Salmonella in food animals and transmission to humans. Because of concerns that nontherapeutic use of agents selects for resistance and that resistance genes can disseminate via the food chain, many European Union countries have banned use of antimicrobial growth promoters in food animal production and coupled these bans to improved production practices (Cogliani et al., 2011). U.S. efforts are needed to reduce unnecessary use of antimicrobial agents in food animals to slow the emergence and spread of resistance and maintain efficacy of agents for the treatment of human infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank state and local health departments and their public health laboratories for their contributions. We acknowledge Fred Angulo for his guidance and critical review. This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Center for Veterinary Medicine.

Footnotes

The contents of this work are solely the responsibilities of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Alcaine SD, Sukhnanand SS, Warnick LD, Su WL, McGann P, McDonough P, Wiedmann M. Ceftiofur-resistant Salmonella strains isolated from dairy farms represent multiple widely distributed subtypes that evolved by independent horizontal gene transfer. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005;49:4061–4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angulo FJ, Nargrund VN, Chiller TC. Evidence of an association between use of anti-microbial agents in food animals and antimicrobial resistance among bacteria isolated from humans and the human health consequences of such resistance. J Vet Med B Infect Dis Vet Public Health 2004;51:374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braden CR. Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis and eggs: A national epidemic in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2006;43:512–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 1998–2002. MMWR 2006;55(suppl 10):1–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Salmonella surveillance annual summary. 2005–2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/dfwed/edeb/reports.html#Salmonella, accessed April 30, 2012.

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Surveillance for foodborne disease outbreaks—United States, 2008. MMWR 2011a;60:1197–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Investigation update: Multistate outbreak of human Salmonella Heidelberg infections linked to ground turkey. 2011b. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/Salmonella/heidelberg/111011/index.html, accessed April 4, 2012.

- [CDC] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System for Enteric Bacteria (NARMS): Human Isolates Final Report, 2010. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [CLSI] Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twenty-Second Informational Supplement. CLSI Document M100-S22. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Cogliani C, Goossens H, Greko C. Restricting antimicrobial use in food animals: Lessons from Europe. Microbe 2011;6:274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Crump JA, Barrett TJ, Nelson JT, Angulo FJ. Reevaluating fluoroquinolone breakpoints for Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi and for non-Typhi Salmonellae. Clin Infect Dis 2003; 37:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutil L, Irwin R, Finley R, Ng LK, Avery B, Boerlin P, Bourgault AM, Cole L, Daignault D, Desruisseau A, Demczuk W, Hoang L, Horsman GB, Ismail J, Jamieson F, Maki A, Pacagnella A, Pillai DR. Ceftiofur resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg from chicken meat and humans, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis 2010;16:48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [FDA] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry #152: Evaluating the safety of antimicrobial new animal drugs with regard to their microbiological effects on bacteria of human health concern. 2003. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AnimalVeterinary/GuidanceComplianceEnforcement/GuidanceforIndustry/UCM052519.pdf, accessed May 11, 2012.

- [FDA] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Federal Register Volume 70, Number 146: Enrofloxacin for poultry; final decision on withdrawal of new animal drug application following formal evidentiary public hearing. 2005. Available at: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2005-08-01/html/05-15224.htm, accessed May 16, 2012.

- [FDA] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Cephalosporin order of prohibition goes into effect. 2012a. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/AnimalVeterinary/NewsEvents/CVMUpdates/ucm299054.htm, accessed May 16, 2012.

- [FDA] U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry #209: The judicious use of medically important antimicrobial drugs in food-producing animals. 2012b. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Animal-Veterinary/GuidanceComplianceEnforcement/GuidanceforIndustry/UCM216936.pdf, accessed May 16, 2012.

- Fisk TL, Lundberg BE, Guest JL, Ray S, Barrett TJ, Holland B, Stamey K, Angulo FJ, Farley MM. Invasive infection with multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium definitive type 104 among HIV-infected adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005;40:1016–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folster JP, Pecic G, Bolcen S, Theobald L, Hise K, Carattoli A, Zhao S, McDermott PF, Whichard JM. Characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolated from humans in the United States. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2009;7:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles WP, Benson AK, Olson ME, Hutkins RW, Whichard JM, Winokur PL, Fey PD. DNA sequence analysis of regions surrounding blaCMY-2 from multiple Salmonella plasmid backbones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004;48:2845–2852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene SK, Daly ER, Talbot EA, Demma LJ, Holzbauer S, Patel NJ, Hill TA, Walderhaug MO, Hoekstra RM, Lynch MF, Painter JA. Recurrent multistate outbreak of Salmonella Newport associated with tomatoes from contaminated fields, 2005. Epidemiol Infect 2008;136:157–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Fontana J, Crowe C, Bolstorff B, Stout A, Van Duyne S, Hoekstra MP, Whichard JM, Barrett TJ, Angulo FJ, the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System PulseNet Working Group. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Newport infections resistant to expandedspectrum cephalosporins in the United States. J Infect Dis 2003;188:1707–1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helms M, Simonsen J, Mølbak K. Quinolone resistance is associated with increased risk of invasive illness or death during infection with Salmonella serotype Typhimurium. J Infect Dis 2004;190:1652–1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson LR, Gould LH, Dunn JR, Berkelman R, Mahon BE; Foodnet Travel Working Group. Salmonella infections associated with international travel: A Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network (FoodNet) study. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2011;8:1031–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones TF, Ingram LA, Cieslak PR, Vugia DJ, Tobin-D’Angelo M, Hurd S, Medus C, Cronquist A, Angulo FJ. Salmonellosis outcomes differ substantially by serotype. J Infect Dis 2008;198:109–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay RS, Vandevelde AG, Fiorella PD, Crouse R, Blackmore C, Sanderson R, Bailey CL, Sands ML. Outbreak of healthcareassociated infection and colonization with multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Senftenberg in Florida. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2007;28:805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura AC, Reddy V, Marcus R, Cieslak PR, Mohle-Boetani JC, Kassenborg HD, Segler SD, Hardnett FP, Barrett T, Swerdlow DL; Emerging Infections Program FoodNet Working Group. Chicken consumption is a newly identified risk factor for sporadic Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis infections in the United States: A case-control study in FoodNet sites. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38(suppl 3):244–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Nizam A, Muller KE. Applied Regression Analysis and Other Multivariable Methods, 4th ed. Belmont, CA: Duxbury, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott PF. Antimicrobial resistance in nontyphoidal Salmonellae In: Antimicrobial Resistance in Bacteria of Animal Origin. Aarestrup FM (ed.). Washington: ASM Press, 2006, pp. 293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Mellon M, Benbrook C, Benbrook KL. Hogging It: Estimates of Antimicrobial Abuse in Livestock. Cambridge, MA: UCS Publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [NARMS] National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. NARMS 2009 Executive Report, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AnimalVeterinary/SafetyHealth/AntimicrobialResistance/NationalAntimicrobialResistanceMonitoringSystem/UCM268954.pdf, accessed April 30, 2012.

- Pegues DA, Miller SI. Salmonella species, including Salmonella Typhi In: Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 7th ed. Mandell GL, Bennett JE, Dollin R (eds.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2010: 2887–2903. [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E, Hoekstra RM, Angulo FJ, Tauxe RV, Widdowson MA, Roy SL, Jones JL, Griffin PM. Foodborne illness acquired in the United States: Major pathogens. Emerg Infect Dis 2011;17: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Threlfall EJ, Day M, de Pinna E, Charlett A, Goodyear KL. Assessment of factors contributing to changes in the incidence of antimicrobial drug resistance in Salmonella enterica serotypes Enteritidis and Typhimurium from humans in England and Wales in 2000, 2002 and 2004. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2006;28:389–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma JK, Greene KD, Ovitt J, Barrett TJ, Medalla F, Angulo FJ. Hospitalization and antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella outbreaks, 1984–2002. Emerg Infect Dis 2005a;11:943–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma JK, Molbak K, Barrett TJ, Beebe JL, Jones TF, Rabastky-Ehrr T, Smith KE, Vugia DJ, Chang HQ, Angulo FJ. Antimicrobial-resistant nontyphoidal Salmonella is associated with excess bloodstream infections and hospitalizations. J Infect Dis 2005b;191:554–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma JK, Marcus R, Stenzel SA, Hanna SS, Gettner S, Anderson BJ, Hayes T, Shiferaw B, Crume TL, Joyce K, Fullerton KE, Voetsch AC, Angulo FJ. Highly resistant Salmonella Newport-MDRAmpC transmitted through the domestic US food supply: A FoodNet case-control study of sporadic Salmonella Newport infections, 2002–2003. J Infect Dis 2006;194: 222–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whichard JM, Gay K, Stevenson JE, Joyce KJ, Cooper KL, Omondi M, Medalla F, Jacoby GA, Barrett TJ. Human Salmonella and concurrent decreased susceptibility to quinolones and extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Emerg Infect Dis 2007;13:1681–1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [WHO] World Health Organization. Antigenic formulae of the Salmonella serovars. 2007. Available at: http://www.pasteur.fr/ip/portal/action/WebdriveActionEvent/oid/01s-000036-089, accessed April 27, 2012.