Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) regulates various fundamental cellular processes, and its constitutive activation is a common driver for cancer. Anti-EGFR therapies have shown benefit in cancer patients, yet drug resistance almost inevitably develops, emphasizing the need for a better understanding of the mechanisms that govern EGFR activation. Here we report that CD317, a surface molecule with a unique topology, activated EGFR in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells by regulating its localization on the plasma membrane. CD317 was upregulated in HCC cells, promoting cell cycle progression and enhancing tumorigenic potential in a manner dependent on EGFR. Mechanistically, CD317 associated with lipid rafts and released EGFR from these ordered membrane domains, facilitating the activation of EGFR and the initiation of downstream signaling pathways including the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK and JAK-STAT pathways. Moreover, in HCC mouse models and patient samples, upregulation of CD317 correlated with EGFR activation. These results reveal a previously unrecognized mode of regulation for EGFR and suggest CD317 as an alternative target for treating EGFR-driven malignancies.

Keywords: CD317, Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC), EGFR, signal transduction, Cell cycle

Introduction

Liver cancer is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, resulting in ~800,000 deaths annually (1). Unlike most other cancers for which the mortality has declined, rates for new liver cancer cases have been rising each year over the last 10 years in the US and other countries (2, 3). The vast majority (~90%) of liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HCC can be treated at early stages by liver transplantation or surgical resection; however, the overwhelming majority of patients are in advanced stages at the time of diagnosis with few treatment options. The five-year survival remains at a dismal rate of ~18% (4). Although the risk factors for HCC are well known—including chronic infection of hepatitis B and C viruses (HBV and HCV) and alcohol abuse, the molecular events driving the pathogenesis are poorly defined (2, 3).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR, also known as ErbB1 or HER1) belongs to the EGFR/ErbB sub-family of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), along with ErbB2/HER2, ErbB3/HER3, and ErbB4/HER4 (5). The cognate ligands for EGFR include EGF, transforming growth factor-α (TGF-α), and amphiregulin (AREG) (6), which induce EGFR homo-dimerization or its hetero-dimerization with the closely related RTKs leading to phosphorylation of EGFR at multiple tyrosine residues in its intracellular region (5). This enables the recruitment of various signaling molecules and the initiation of intracellular signaling pathways (e.g., Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK, JAK-STAT, and PI3K-AKT pathways) to modulate proliferation, survival, mobility, metabolism, differentiation, and other fundamental cellular processes (7). Dysregulation of EGFR drives the development and progression of various tumors (8). Therapies that inhibit EGFR, including monoclonal antibodies (e.g., trastuzumab) and small-molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib), are among the most successful examples of targeted cancer therapies, benefiting patients with metastatic lung, colorectal, pancreatic, or head and neck cancers (9). However, resistance to these therapies almost invariably develops (9). Moreover, EGFR is overexpressed in 40–70% of human HCCs (10). Still, EGFR inhibitors (cetuximab, gefitinib and erlotinib) did not show significant efficacy in unselected patients with advanced HCC in clinical trials (11, 12). Therefore, a better understanding of the regulation of EGFR signaling is critical for the therapy of cancer in general and HCC in particular.

EGFR is associated with lipid rafts (13). These specialized membrane microdomains—which are enriched in cholesterol, sphingolipids, and certain proteins—are involved in intracellular signaling, trafficking, and pathogen-host interactions. In general, lipid rafts promote interactions among signaling molecules, and their disruption (e.g., by cholesterol depletion) impairs receptor activation (14). However, EGFR appears to be an exception, as it is kept in an auto-inhibitory conformation upon localization in lipid rafts (13). Release of EGFR from lipid rafts can lead to ligand-independent EGFR dimerization and auto-activation (15, 16). Given the importance of lipid rafts in EGFR activation, a salient, yet poorly understood question, is how the association of EGFR with lipid rafts is regulated.

CD317 (also known as BST2, HM1.24, or tetherin) is a type II transmembrane protein with an unusual structure, comprising a short cytoplasmic N-terminal region, a transmembrane (TM) domain, a coiled-coil extracellular domain, and a C-terminal glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor (Figure S1A) (17, 18). As such, CD317 is double anchored into the membrane through both the TM domain and GPI, a topology that is unique among human proteins (19, 20). CD317 is thought to be inserted both inside (via the GPI anchor) and outside (via the TM domain) lipid rafts (19, 21). Thus, it may influence the high-order structures of these lipid microdomains. CD317 plays a multifaceted role in regulating host-pathogen relationship. It is an important restriction factor for various enveloped viruses such as HIV, HBV, and HCV, preventing their release from infected cells (22). When physically sequestering retroviral particles, CD317 also potently activates NF-κB leading to the expression of proinflammatory gene (23–26). Of note, CD317 is implicated in tumorigenesis. It is overexpressed in multiple myeloma and several other cancers (23, 27–30), and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against CD317 showed tumor toxicity in animal models (31, 32). Nevertheless, it remains unclear whether CD317 affords a proliferative advantage to tumor cells and if so, what the underlying molecular mechanism may be.

In the present study, we investigate the role of CD317 in HCC. We find that CD317 is up-regulated in HCC samples. CD317 strongly promotes HCC proliferation and cell cycle progression and enhances its tumorigenicity. Interestingly, the effect of CD317 is mediated by EGFR. CD317 promotes the release of EGFR from the lipid rafts, promoting its auto-activation. These results establish a critical role for CD317 in tumorigenesis and reveal a new mode of regulation for EGFR that likely influences the pathogenesis of HCC and other tumors.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

DMEM medium and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from HyClone (Logan, USA); L-glutamine from Gibco (CA, USA); Annexin V-FITC/PI apoptosis detection kit from TransGen Biotech (Beijing, China); cell cycle analysis kit from KeyGEN BioTECH (Nanjing, China); methyl-β-cyclodextrin (C4555) and cholesterol (C3045) from Sigma-Aldrich, and Erlotinib-HCl (OSI-744) from Selleckchem.

Cell culture

Bel7402, HepG2, and Huh 7 were purchased from Shanghai Cell Bank of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and were authenticated by the vendor using short tandem repeat profiling (STR). HEK293T was purchased from ATCC and confirmed by STR (GENEWIZ). Cell lines were cultured in DMEM medium (Hyclone, Utah, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Victoria, Australia) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco, CA, USA), and periodically authenticated by morphologic inspection and biomarkers detection (if applicable). All cells were used within 6 months of continuous passage and checked for the absence of Mycoplasma using detection kit (LT27–710, LONZA).

Human samples and immunohistochemical staining

Two human hepatocellular carcinoma arrays were used in this study. The first one contained 35 tumor samples and 8 normal liver tissues (Xi’an Alena Biotech), and the second one contained 75 tumor samples (Shanghai Outdo Biotech). The other 5 specimens (3 HCC and 2 normal liver tissues) were obtained from Second People’s Hospital of Shenzhen, which was approved by the Research Committee of Shenzhen Institutes of Advanced Technology (SIAT), Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed as previously described (33) using following antibodies: anti-CD317 (ab134061; Abcam), anti-pY845 EGFR (BS5013; Bioworld) or (GTX133600) (GeneTex), and anti-PCNA (10205–2-AP, Proteintech). All slides were independently analyzed by two pathologists in a blinded manner and scored according to staining intensity (no staining = 0, weak staining = 1, moderate staining = 2, strong staining = 3) and the number of stained cells (0% = 0, 1–25% = 1, 26–50% = 2, 51–75% = 3, 76–100% = 4). Final immunoreactive scores were determined by multiplying the staining intensity by the number of stained cells, with minimum and maximum scores of 0 and 12, respectively (34). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the results.

Xenograft tumor models

Male BALB/c nude mice at 6–8 weeks of age were purchased from Guangdong Medical Laboratory Animal Center (Guangzhou, China) and housed in the SIAT facility under pathogen-free conditions.

To investigate the effects of CD317 on established tumor growth, we performed both overexpression and knockdown experiments. For overexpression, 5×106 CD317-stable expression HepG2 cells or control cells in 100 μl PBS containing 50% Matrigel (BD, Bedford, MA, USA) were injected subcutaneously into flanks of nude mice. Tumor incidence and growth were monitored. Twenty-eight days later, tumor-bearing and control mice were sacrificed, and tumors were dissected for the measurement of tumor weights and volumes using the formula [length × (width)2]/2. For knockdown, 1.5×107 HepG2 cells stably expressing CD317 or control shRNA were injected. Tumor growth was monitored, and tumors were harvested at day 23. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at SIAT.

Bioinformatics analysis of CD317 expression in human HCC

CD317 protein expression in HCC tissues and normal tissues was determined from the human protein atlas (www.proteinatlas.org). HCC CD317 gene expression was determined through analysis of Mas Liver and Wurmbach Liver databases, which are available through Oncomine (www.oncomine.org).

Plasmids and siRNAs

CD317 (the long isoform) was transiently expressed using MigR1- or pCMV-based plasmids, or stably expressed using PLVX-based lentiviral vectors. The full-length human CD317 cDNA was generated from Jurkat cells by RT-PCR, digested with Bgl II and Xho I, and cloned into MigR1 or PLVX. The extracellular domain of CD317 (ECD, amino acids: 44–159) (35) was generated via PCR reaction and cloned into pCMV-C-His vector. The plasmids encoding CD317 mutants in which the two N-linked glycosylation sites (Asn-65 and Asn-92) were replaced with Asp, were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis. The delCT and delGPI variants of CD317, which lacked the N-terminal 20 amino acids and C-terminal 19 amino acids, respectively, were fused with HA tag in the N or C terminus and cloned into pCMV-C-His or PLVX vector. siRNA-resistant (SR) CD317, delCT and delGPI constructs, each tagged with HA, were generated via PCR by making three synonymous mutations in the siRNA recognition site of human CD317, and they are called HA-CD317-SR, HA-delCT-SR and HA-delGPI-SR, respectively. Specific siRNA for human CD317 and nonspecific negative control were described previously (36). For stable transfection, two shRNAs targeting human CD317 (sh317) and control shRNA (shCtrl) were cloned into pLVTHM vectors. Forward oligonucleotide sequences for shRNAs and siRNAs were provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Transfection and lentiviral infection

Transfection of tumor cells with plasmids or siRNAs was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For lentivirus production, HEK293T cells were transfected with each lentiviral vector together with helper plasmids Gag, Rev and VSVG. 48 to 72 h after transfection, virus-containing media was collected by centrifugation at 100 × g for 5 min and concentrated by centrifugation at 50,000 × g for 2 h. Cells were transduced using lentiviruses with 6 μg/ml polybrene and selected with FACS.

Cell viability and colony formation assay

24 h following transfection, Bel7402, Huh7 or HepG2 cells were seeded in triplicates in 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well and maintained in medium containing 10% FBS. Cells were strained with 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Promega) at the indicated time points, and relative viable cells were determined by measuring the OD at an absorbance wavelength of 490 nm.

For colony formation assays, transfected Bel7402 or HepG2 cells were plated in triplicates in 6-well plate at 1,500 cells/well and maintained in medium containing 10% FBS for 7–10 days. Colonies were fixed with methanol and stained with crystal violet staining solution (Beyotime, China).

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis

Cell cycle and apoptosis were assessed by flow cytometry (FACS Canto II, BD). For cell cycle analysis, 48 h following transfection, Bel7402, HepG2, or Huh7 cells were seeded in triplicates in 12-well plates at 1 × 105 cells/well, synchronized by serum starvation, and allowed to grow for 18–24 h. Cells were collected, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed in cool ethanol at −20 °C overnight before being stained with propidium iodide (PI) (KeyGEN BioTECH, China) at room temperature for 30 min. For apoptosis analysis, cells were collected, washed with PBS, double-stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI using an Apoptosis Detection Kit (TransGen Biotech, China) at room temperature for 15 min in the dark

RNA isolation and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen) and used to generate cDNA. Specific primers used for quantitative real-time PCR assays were synthesized by Invitrogen Corporation. Their sequences were shown in Supplemental Table 2.

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Whole-cell lysate was prepared by suspending cells in the RIPA buffer (Beyotime, China) supplemented with 1× complete protease inhibitors mixture and 1× phosphatase inhibitor (Roche). Protein concentration was determined by BCA assay (Pierce, Rockford, USA). Equal quantities of proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane, and blotted with specific antibodies. Protein in the membrane was visualized by an enhanced chemiluminescense detection kit (Millipore, USA). Rabbit antibodies against the following proteins or modifications were used with the catalogue numbers and sources indicated: CD317 (ab134061), TGF-α (ab208156) (Abcam); caspase3 (9662) (CST); pY1068 EGFR (BS5010), pY845 EGFR (BS5013), pY705 STAT3 (BS4181), STAT3 (AP0365), ERK½ (BS1112), pT202/Y204 ERK½ (BS5016), cyclin D1 (BS6352), and p16 INK4a (BS6431), caveolin-1 (BS9878M) (Bioworld Technology), and AREG (16036–1-AP) (Proteintech). Mouse antibodies against the following proteins/epitopes were used: HA.11 (MMS-101P) (Covance); Ki67 (P6834) (Sigma); transferrin receptor (13–6800) (Invitrogen); GAPDH (MB001) (Bioworld Technology); β-actin (sc-47778) and EGFR (sc-373746) (Santa Cruz Biotech). HRP-conjugated mouse anti-His (M20020) was purchase from Abmart., mouse HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (074–1806) from KPL, and HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (E030120–02) from EARTHOX.

Lipid raft and non-raft proteins isolation

Lipid raft and non-raft proteins were isolated using the Focus Global Fractionation kit (G Biosciences, St Louis, MO, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

HepG2 cells were lysed in immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 50 mM EDTA, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM PMSF) supplemented with 1× complete protease inhibitors mixture (Roche). Extracts were assayed for protein content, using the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce, Rockford, USA) after clarification by high-speed centrifugation at 4 °C. Immunoprecipitation was performed using protein-A/G Dynabeads (Pierce, 88803). In brief, 400 μg protein-A/G Dynabeads was coated with 1 μg specific antibody (Rabbit anti-CD317, sc-99191, or mouse anti-EGFR, sc373746; Santa Cruz) or Ig control for 1 h at room temperature with rotation. After removing unbound antibody, the bead-antibody complex was incubated with 500 μL cell lysate for 6 h at 4 °C with rotation. The captured immunoprecipitates were washed five times with IP buffer and boiled in 2× loading buffer. The eluted proteins were fractionated by SDS/PAGE and detected by Western blot.

ELISA

Supernatant was collected from HepG2 or Bel7402 cells at 48 h after transfection and kept at −80 °C. The concentration of TGF-α and AREG was measured using ELISA kits purchased from ThermoFisher (ThermoFisher, Frederick, MD, USA) and BOSTER (BOSTER, Wuhan, China) respectively according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

Immunofluorescence and microscopy

Immunofluorescent staining was performed as previous description (36) using the following antibodies: mouse anti-EGFR (Santa Cruz, sc-120), rabbit anti-pY1068 EGFR (Bioworld Technology, BS5010) and rabbit anti-pY845EGFR (Bioworld Technology, BS5013), rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG and goat anti-mouse IgG (Molecular Probes). 4, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Roche) and Alexa Fluor 488-Conjugated Cholera Toxin Subunit B (C-34775, Life Technology) were used to label nuclei and lipid raft, respectively. 10–15 high-powered fields were evaluated on optical microscopy (Olympus IX71, Tokyo, Japan), and fixed fluorescence images were analyzed by ImagePro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD).

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism Software (San Diego, CA). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous data for two groups, Pearson correlation co-efficiency was used to analyze the relationship between the phosphor-Y845 EGFR and the CD317 staining levels in tissue sections. Tumor incidences of CD317-overexpression and control group were analyzed using the log-rank test. P values < 0.05 were considered to be significant.

Results

CD317 is upregulated in HCC and enhances tumorigenicity of HCC cells

To investigate the role of CD317 in HCC, we examined its expression in thirty-eight HCC tumor samples and ten normal liver samples using immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 1A, the level of CD317 was significantly increased in the majority of the HCC samples compared with the normal liver samples. A survey of a public database (Human Protein Atlas, www.proteinatlas.org) also showed that expression of the CD317 protein was significantly increased in HCCs (Supplementary Fig. S1B). In addition, CD317 mRNA levels were elevated in HCCs compared to normal liver tissues (www.oncomine.org) (Supplementary Fig. S1C).

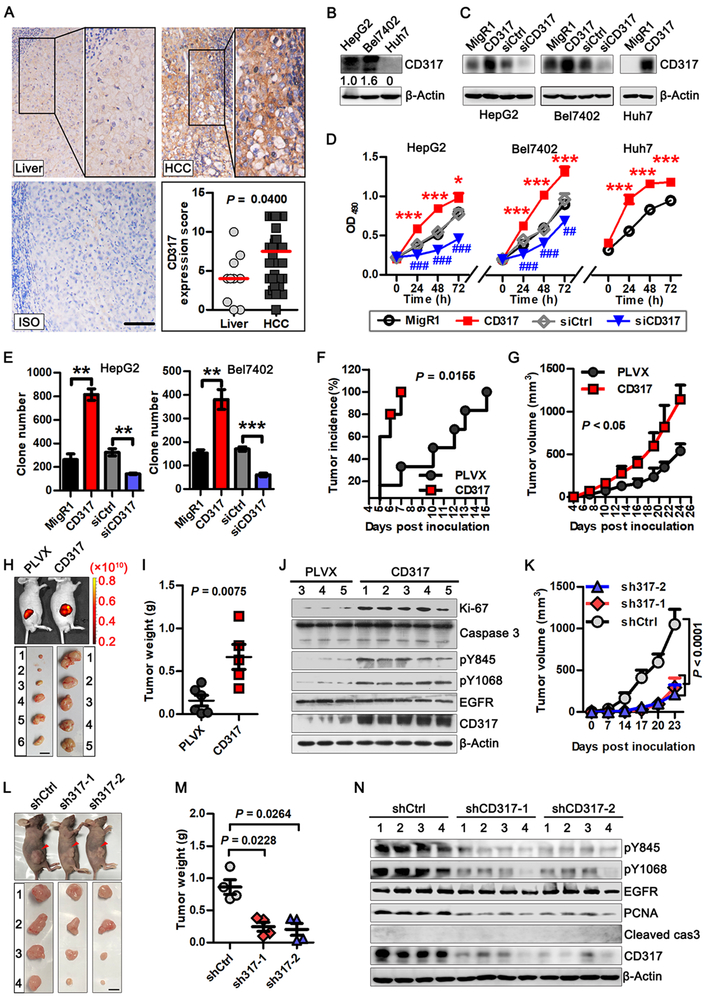

Fig. 1. Upregulation of CD317 expression correlates with tumorigenesis.

(A) CD317 upregulation in hepatocellular carcinoma. CD317 protein expression in tumors and normal tissues from patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma was analyzed by immunohistochemistry. CD317-positive cells are shown in brown. Quantitation of the CD317 expression in tumors (n = 38) and normal tissues (n = 10) was performed as described in Methods. Each data point represents a CD317 expression score of patients. The horizontal bars represent the medians. Scale bar: 100 μm.

(B) Levels of CD317 protein in the human cell lines.

(C) Immunoblot analysis of HCC cells with or without CD317 overexpression or knockdown.

(D) Proliferation of HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells transiently transfected with control (MigR1) or CD317 plasmid, or with control (siCtrl) or CD317 siRNA (siCD317). * P < 0.05 and *** P < 0.001 for CD317 vs MigR1 group. ## P < 0.005 and ### P < 0.001 for CD317 siRNA vs control siRNA group.

(E) Colony formation of HepG2 and Bel7402 cells transiently transfected with MigR1, CD317, siCD317 or control siRNA. ** P < 0.005, *** P < 0.001.

(F-I) HepG2 cells transfected with control (PLVX) or CD317 plasmid were injected s.c. into nude mice. Shown are tumor incidences (F) and tumor growth (G) overtime, and typical whole-body fluorescence images (H, upper panel), tumor appearance (H, bottom panel), and weight (I, mean ± SEM) at 28 days post-injection. ** P < 0.005.

(J) Total lysates from PLVX and CD317 tumors were analyzed by western blotting.

(K-M) HepG2 cells transfected with control (shCtrl), CD317 shRNA-1 (sh317–1), or CD317 shRNA-2 (sh317–2) were injected s.c. into nude mice. Shown are tumor growth (K) overtime, and typical whole-body images (L, upper panel), tumor appearance (L, bottom panel), and weight (M, mean ± SEM) at 23 days post-injection.

(N) Total lysates from shCtrl, sh317–1 and sh317–2 tumors were analyzed by western blotting.

To test the function of CD317 in HCC cells, we used three cell lines—HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7, which express low to high levels of endogenous CD317 mRNA and protein (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S1D). We knocked down CD317 in HepG2 and Bel7402 cells using small interfering RNA (siRNA) (Fig. 1C). This led to a strong reduction in cell proliferation (Fig. 1D and 1E, and Supplementary Fig. S1E). Conversely, we overexpressed exogenous CD317 in HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells (Fig. 1C), and observed a marked increase in proliferation (Fig. 1D and 1E, and Supplementary Fig. S1E). Neither knockdown nor overexpression of CD317 affected apoptosis (Supplementary Fig. S1–S1G), consistent with our previous observations (36).

To investigate the role of CD317 in tumor formation in vivo, we implanted control and CD317-overexpressing HepG2 cells (Fig. S2A) into immunodeficient nude mice. Compared to control cells, HepG2 cells with CD317 overexpression generated tumors with an earlier onset and a faster rate (Fig. 1F and 1G). By day 28 following xenograft, CD317-overexpressing cells grew into tumors that were three times as large as those generated by control cells (P < 0.05, n = 5–6) (Fig. 1H and 1I, and Supplementary Fig. S2B). The increased tumorigenic potential of CD317-overexpressing cells was likely due to enhanced proliferation instead of reduced apoptosis, as tumors generated from these cells showed increased Ki-67 levels, but unchanged caspase-3 activation, compared to tumors generated from control cells (Fig. 1J). Conversely, CD317 knockdown markedly suppressed tumor growth (Fig. 1K–1M and Supplementary Fig. S2C) and reduced proliferation, characterizing by low PCNA expression (Fig. 1N). These results indicate that CD317 is required for optimal proliferation and tumor formation of HCC cells.

CD317 promotes cell cycle progression in HCC cells

Given that CD317 promotes cell proliferation, we analyzed how it affects cell cycle progression. Compared to their corresponding control cells, CD317-overexpressing HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells displayed accelerated cell cycle progression, as evident by a noticeable increase in S-phase cells and a concomitant decrease in G0/G1-phase cells (Fig. 2A and Supplementary Fig. S3A). Conversely, CD317-depleted HepG2 and Bel7402 cells showed a significant reduction in cell cycle progression, with fewer S-phase cells and more G0/G1-phase cells (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Fig. S3B).

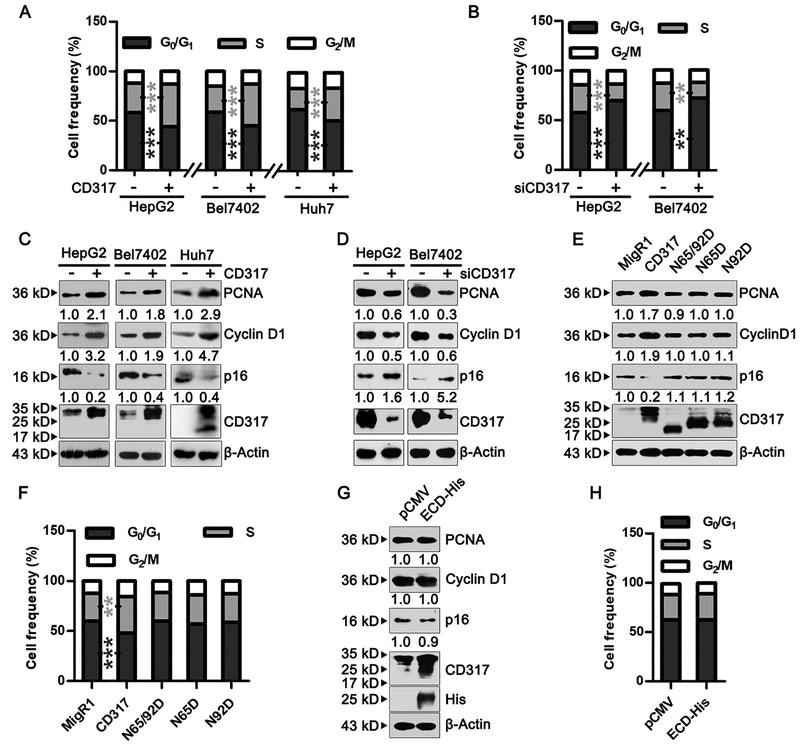

Fig. 2. CD317 accelerates cell cycle transition in vitro.

(A, B) HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells were transfected with the control vector (MigR1) or either CD317 (A), or HepG2 and Bel7402 cells were transfected with control or CD317 siRNA (B). Percentage of cells in G0/G1, S, and G2/M phase was quantified (means ± SEM). ** P < 0.005, *** P < 0.001

(C, D) Expression of cell cycle-related proteins in HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells transfected with MigR1 or CD317 (C), or in HepG2, Bel7402 cells transfected with control or CD317 siRNA (D). Blots in C and D were exposed for different times to better show the effects of CD317 overexpression or knockdown.

(E, G) Expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins in HepG2 cells transfected with MigR1 vector, wild type CD317, or the indicated CD317 mutants (E), or with the control vector pCMV and CD317-ECD-His (G). In (G), the endogenous CD317 and CD317-ECD-His was detected by anti-CD317 antibody, while CD317-ECD-His was also detected by anti-His antibody.

(F, H) Cell cycle progression of HepG2 cells transfected with MigR1 vector, wild type CD317, or the indicated CD317 mutants (F), or with the control vector pCMV and CD317-ECD-His (H). Values represent means ± SEM. ** P < 0.005, *** P <0.001.

The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Forced expression of CD317 in HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells elevated the levels of the CDK4/6 activator cyclin D1 and the DNA polymerase co-factor PCNA, while reducing the levels of the CDK inhibitor p16 (Fig. 2C). Conversely, knockdown of CD317 in HepG2 and Bel7402 cells markedly decreased the expression of cyclin D1 and PCNA, while enhancing the expression of p16 (Fig. 2D).

Glycosylation and membrane localization are essential for CD317 function

CD317 is a type II transmembrane protein, with its ectodomain containing two N-linked glycosylation sites, Asn65 and Asn92. Previous studies suggested that N-linked glycosylation at these residues may be required for the correct folding, but not antiviral activity, of CD317 (37). However, the role of this modification in tumor cells has not been addressed. We mutated Asn65 and Asn92 to Asp individually (N65D and N92D, respectively) or in combination (N65D/N92D). Consistent with a previous report (37), the N65D and N92D mutations reduced the apparent molecular weight of CD317 from 30–36 kDa to ~28 kDa, while the N65D/N92D mutation further reduced the apparent molecular weight to ~21 kDa (Fig. 2E). Unlike wild-type CD317, none of the glycosylation-defective mutants affected the levels of PCNA, cyclin D1, or p16 (Fig. 2E). Consistently, in contrast to wild type CD317, cells expressing these mutations showed no difference in cell cycle progression compared to the parental cells (Fig. 2F and Supplementary Fig. S3C). Additionally, we generated CD317-ECD, a truncated mutant that contained only the ectodomain and hence was not anchored in the plasma membrane. CD317-ECD did not affect the progression of cell cycle or the levels of cell cycle regulators either (Fig. 2G, 2H, and Supplementary Fig. S3D). Thus, both glycosylation and membrane localization are required for the function of CD317 in cell cycle progression.

CD317 activates the EGFR-STAT/ERK pathway

Next, we investigated the mechanism through which CD317 promotes cell proliferation. By analyzing various mitogenic pathways, we observed that CD317 strongly influenced both the RAS-Raf-MEK-ERK and JAK-STAT signaling pathways. Specifically, overexpression of CD317 increased, while knocking down CD317 decreased, the activation of ERK½ and STAT3 in HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells (Fig. 3A). While evaluating the signaling events upstream of both pathways, we noticed that CD317 is a potent activator for EGFR. Specifically, forced expression of CD317 led to a strong increase in the auto-phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr1068, as well as Src-mediated phosphorylation of EGFR at Tyr845 (Fig. 3B). Conversely, depletion of CD317 by siRNA resulted in a noticeable reduction in these phosphorylation events (Fig. 3B). In contrast, CD317-N65D/N92D, the glycosylation mutant that failed to accelerate cell cycle, did not affect EGFR activation (Fig. 3B).

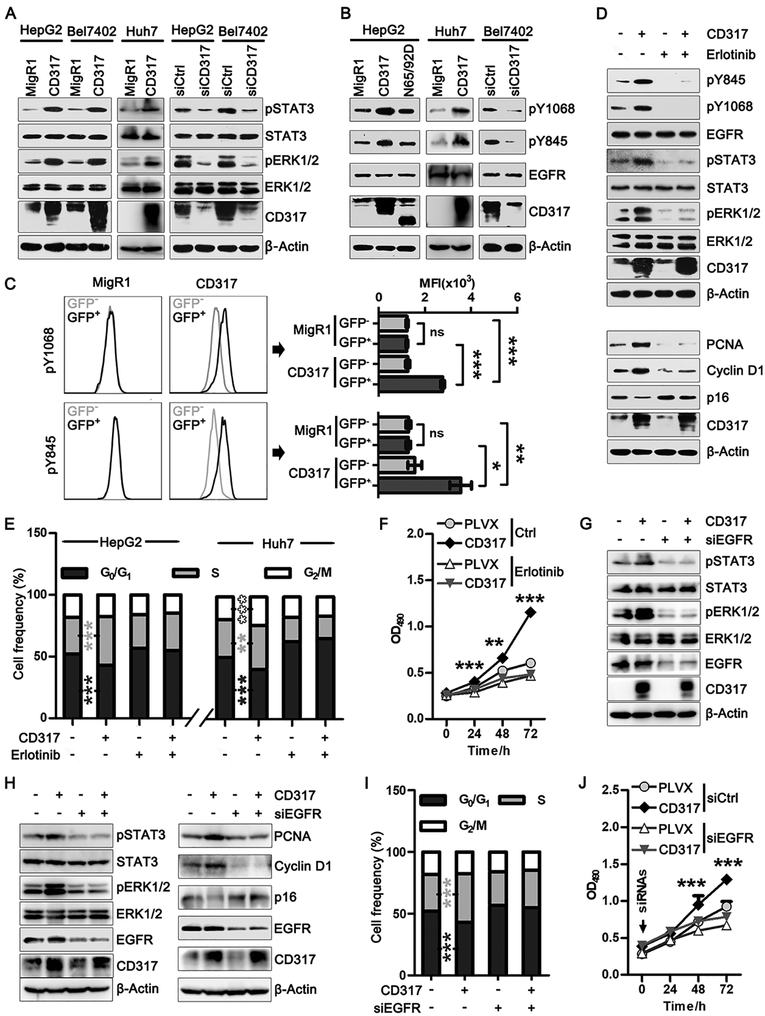

Fig. 3. CD317 function is dependent on EGFR-STAT3/ERK axis.

(A) STAT3 and ERK½ phosphorylation levels in HepG2, Bel7402 and Huh7 cells transiently transfected with MigR1 or CD317 (left), or with control siRNA or CD317 siRNA (right). The levels of CD317, pSTAT3, total STAT3, pERK½, and total ERK½ were determined by Western blot.

(B) HepG2 cells were transfected with control MigR1 vector, CD317, or CD317 N65/92D (left), Huh7 cells were transfected with control MigR1 vector or CD317 (centered), and Bel7402 cells were transfected with control or CD317 siRNA (right). The levels of CD317, pY845 EGFR, pY1068 EGFR, and total EGFR were analyzed by Western blot.

(C) Representative FACS graphs (left) and statistical analysis (right) of EGFR phosphorylation levels in HepG2 cells transiently transfected with control MigR1 vector or CD317. Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) values of GFP-negative and -positive cells was analyzed as indicated. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.005, *** P < 0.001.

(D) HepG2 cells transfected with MigR1 or CD317 were treated with or without Erlotinib (50 μM). Cells were analyzed for the activation of EGFR, STAT3, and ERK½ (top), expression of cell cycle-related proteins (bottom).

(E, F) HepG2 cells stably infected with control (PLVX) or CD317-expressing lentiviruses, and Huh7 cells transfected with control (MigR1) or CD317 vectors were treated with or without Erlotinib (50 μM). Cell cycle distribution (E) and cell proliferation (F) were analyzed. ** P < 0.005, *** P < 0.001 for CD317 vs control group.

(G) Huh7 cells transfected with control (MigR1) or CD317 vectors were treated with control or EGFR siRNA (siEGFR). Activation of STAT3 and ERK½ were analyzed.

(H-J) HepG2 cells stably infected with PLVX or CD317 lentiviruses were treated with control or EGFR siRNA. Activation of EGFR, STAT3, and ERK½ (H, left), expression of cell cycle-related proteins (H, right), cell cycle distribution (I), and cell proliferation (J) were analyzed. *** P < 0.001 for CD317 vs PLVX group.

To confirm these results, we analyzed the levels of phosphorylated EGFR using immunofluorescence staining and FACS analysis. We transfected HepG2 cells with a CD317 plasmid that co-expressed GFP, as well as the control plasmid expressing only GFP. By staining cells with anti-phospho-Tyr845 (anti-pY845) and anti-pY1068 antibodies, we observed that phosphorylation of endogenous EGFR was significantly enhanced in cells with CD317 overexpression (CD317 group, GFP-positive), but not in cells without CD317 overexpression (CD317 group, GFP-negative; and control group, GFP-positive and -negative) (Supplementary Fig. S4A). A FACS analysis further confirmed that forced expression of CD317 enhanced the levels of pY845 and pY1068 EGFR in HepG2 cells (Fig. 3C). Additionally, CD317 knockdown sensitized tumor cells to Erlotinib treatment, as shown by a decreased IC50 in CD317-depleted tumor cells (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Moreover, tumors formed by the CD317-overexpressing HepG2 cells showed noticeably higher EGFR activation compared to tumors formed by control HepG2 cells (Fig. 1J), while CD317-knockdwon tumors showed substantially lower EGFR activation compared to control tumors (Fig. 1N).

To determine whether CD317 activates RAS-Raf-MEK-MAPK and JAK-STAT pathways via EGFR, we treated HepG2 cells with the EGFR inhibitor Erlotinib at a dose that almost completely blocked EGFR activation (Fig. 3D). Under this condition, CD317 was no longer able to stimulate the activation of STAT3 and ERK (Fig. 3D, top) or alter the expression of cyclin D1, PCNA, and p16 (Fig. 3D, bottom). Moreover, Erlotinib effectively negated CD317-mediated acceleration in cell cycle progression (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. S4C) and proliferation (Fig. 3F). We also used siRNAs to knock down EGFR in HepG2 and Huh7 cells. This markedly impaired CD317-induced activation of STAT3 and ERK (Fig 3G and Fig. 3H, left), and effectively abrogated the effect of CD317 on cyclin D1, PCNA, and p16 (Fig. 3H, right). Knocking down EGFR also rendered CD317 incapable of stimulating cell cycle progression (Fig. 3I and Supplementary Fig. S4D) or proliferation (Fig. 3J). Collectively, these data show that CD317 promotes mitogenic signaling, as well as cell cycle progression and proliferation, via the activation of EGFR.

CD317 regulates EGFR in a lipid raft-dependent manner

CD317 did not influence the expression of EGFR (Fig. 4A and 4B). Moreover, CD317 did not appear to stably associate with EGFR, as shown by a co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 4C). EGFR is activated by binding to its cognate ligands, including EGF, TGF-α (5), and AREG (6). However, the expression of EGF was minimal in HepG2 and Bel7402 cells (Fig. 4A and 4B). Moreover, neither CD317 overexpression (in HepG2 cells) nor knockdown (in Bel7402 cells) significantly altered the protein and mRNA levels of TGF-α or AREG (Fig. 4A and 4B). Moreover, knockdown of both TGF-α and AREG did not influence CD317-mediated EGFR activation (Supplementary Fig. S4E), suggesting that CD137-induced EGFR activation is not mediated by these EGFR ligands.

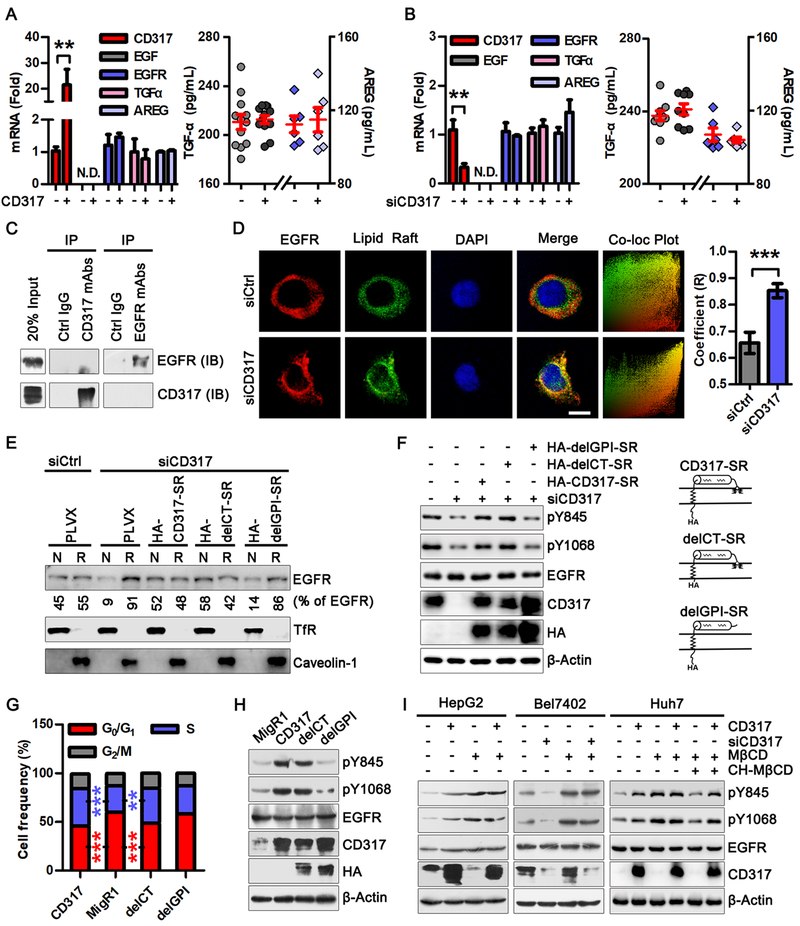

Fig. 4. CD317 regulates EGFR in a lipid raft-dependent manner.

(A, B) HepG2 cells were transfected with MigR1 or CD317 plasmid (A), and Bel7402 cells were transfected with control or CD317 siRNA (B). 48 h later, mRNA levels of CD317, EGFR, EGF, TGF-α and AREG were determined by real-time PCR (left), the protein levels of TGF-α and AREG in culture supernatants were detected by ELISA (right). Values represent means ± SEM, ** P < 0.005. The experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

(C) Lysates of HepG2 cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-CD317 or anti-EGFR antibodies as indicated. Cell lysates (input) and immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting.

(D) HepG2 cells transfected with control or CD317 siRNA were immunostained for EGFR (red), lipid rafts (green), and DNA (DAPI, blue). Shown are representative fluorescence images and EGFR-lipid rafts co-localization plot (left), and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (R) (right; mean ± SEM for at least 30 cells). *** P < 0.001. Scale bar: 20 μm.

(E) HepG2 cells were transfected with control or CD317 siRNA, along with control (pLVX) or siRNAs-resistant (SR) CD317, delCT, and delGPI plasmids. EGFR in non-lipid raft (N) and lipid raft fractions were analyzed by Western blot. Transferrin receptor (TfR) and Caveolin-1 serve as loading controls for non-raft proteins and lipid raft proteins, respectively.

(F) EGFR activation in CD317-knockdown HepG2 cells expressing the indicated siRNAs-resistant CD317 plasmids or the PLVX control vector.

(G, H) HepG2 cells expressing MigR1, CD317, HA-delCT-CD317 (delCT), and delGPI-CD317-HA (delGPI) (H, right) were analyzed for cell cycle progression (G) and EGFR activation (H, left). ** P < 0.005, *** P < 0.001 for CD317 or delCT vs PLVX group.

(I) HepG2 and Huh7 cells were transfected with MigR1 or CD317 plasmid, and Bel7402 cells were transfected with Ctrl or CD317 siRNA and treated with or without 10 mM Methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) for 30 min. Thereafter, cholesterol was reloaded for 90 min using cholesterol-saturated MβCD (2:10 chol-MβCD, 2 mM cholesterol, and 10 mM MβCD) in Huh7 cells. The levels of CD317, pY845-EGFR, pY1068-EGFR, and total EGFR were determined by Western blot.

The activation of EGFR is regulated by its localization to lipid rafts (13, 15, 16). Considering that CD317 is associated with lipid rafts (38), we investigated whether CD317 affects the raft versus non-raft distribution of EGFR. Using a fluorescently-tagged cholera toxin B subunit (CTB) that specifically labels lipid rafts (39), we observed that CD317 knockdown cells exhibited high levels of co-localization of EGFR with lipid rafts, characterized by an increased coefficient value between EGFR and lipid raft staining (Fig. 4D). We also detected EGFR by western blot and found that knocking down CD317 led to a dramatic re-distribution of EGFR to the lipid raft fraction (Fig. 4E). Upon the expression of an siRNA-resistant form of CD317 in the CD317-knockdown cells, the localization of EGFR was essentially restored to that in control cells (Fig. 4E), confirming the specificity of the CD317 siRNA.

The extracellular C-terminal GPI anchor of CD317 enables its association with the lipid rafts, and the cytoplasmic N-terminal region of CD317 links to the actin cytoskeleton (17, 40). We generated siRNA-resistant CD317 variants, delGPI and delCT, in which the GPI modification signal and the cytoplasmic tail were deleted, respectively (Fig. 4E). delCT, like the siRNA-resistant full-length CD317, was able to reverse the association of EGFR with lipid rafts in CD317 knockdown HepG2 cells, whereas delGPI showed no such an activity (Fig. 4E). Also, delCT elicited a similar effect as the full-length CD317 in promoting EGFR activation in HepG2 cells devoid of CD317, but delGPI failed to do so (Fig. 4F). Consistently, delCT, but not delGPI, promoted cell cycle progression (Fig. 4G and Supplementary Fig. S4F) and EGFR activation (Fig. 4H) as effectively as the full-length CD317.

Furthermore, we disrupted lipid rafts by depleting cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD). In accordance with previous reports (41), this treatment resulted in EGFR activation in HepG2, Bel7402, and Huh7 cells (Fig. 4I). Importantly, under this condition, neither CD317 overexpression nor CD317 depletion influenced the activation of EGFR in these cells (Fig. 4I). However, this effect of MβCD on CD317-mediated EGFR activation can be reverted by replenishment with cholesterol (Fig. 4I), further supporting the notion that lipid raft is required for effect of CD317 on EGFR. Collectively, these data indicate that CD317 regulates EGFR activation by promoting the release of EGFR from lipid rafts.

Activation of EGFR correlates with CD317 expression in human HCCs

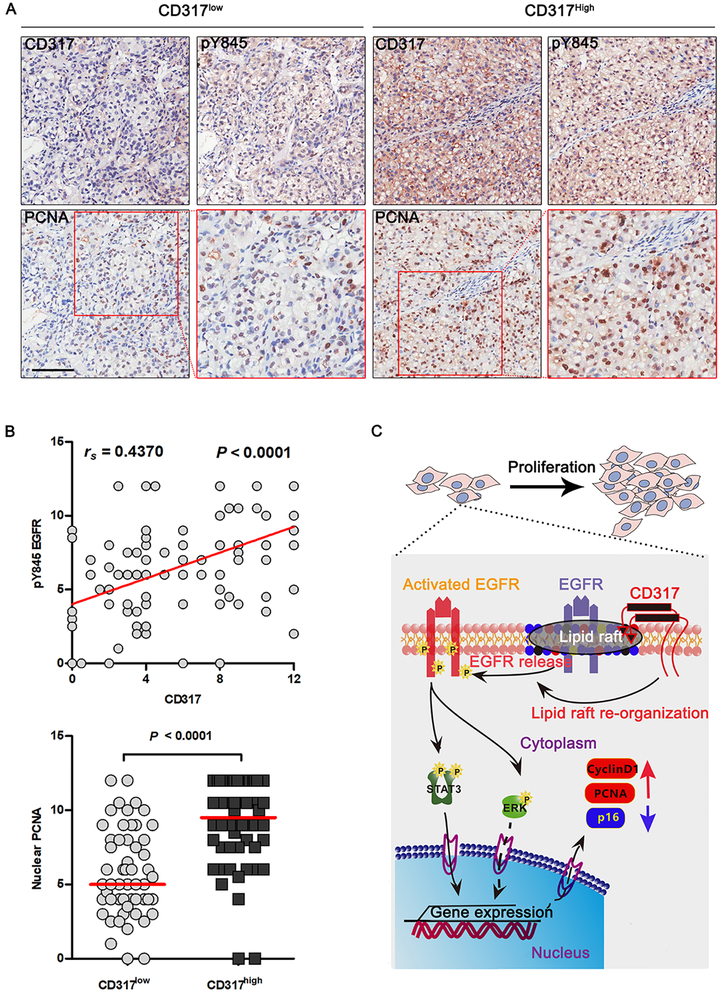

To investigate the role of CD317 in EGFR activation in human tumors, we analyzed CD317 expression, EGFR activation, and hepatocyte proliferation (using nuclear PCNA as a marker) in 110 HCC samples. Interestingly, the activated form of EGFR (pY845 EGFR) positively correlated with the CD317 expression (rs = 0.4370, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 5A and 5B). Patients with low CD317 expression (expression score < 6, N = 56) also showed reduced nuclear PCNA than patients with high CD317 expression (expression score ≥ 6, N = 54) (Fig. 5B, bottom). These results suggest that CD317 promotes HCC development through EGFR-mediated mitogenic signals.

Fig. 5. Upregulation of CD317 correlates with the activation of EGFR in HCC.

(A) Immunohistological staining of CD317, pY845-EGFR, and PCNA in HCC sections. Scale bars in black and white indicate 50 and 20 μm, respectively.

(B) Statistical results of data shown in (a). Shown are correlation co-efficiency between the phosphor-Y845 EGFR and the CD317 staining levels in tissue sections (n = 110) (upper), and nuclear PCNA expression in CD317high (score ≥ 6, n = 56) and CD317low (score < 6, n = 54) patients (bottom). Each data point represents a patient. The horizontal bars represent the medians.

(C) Proposed role of CD317 in HCC development. CD317 expression is markedly up-regulated in HCC, leading to over-activation of EGFR and the downstream molecules, such as STAT3 and ERK½, by modulating lipid raft dynamic. STAT3 collaborated with ERK½ signaling to activate the expression of Cyclin D1 and PCNA, inhibits p16 expression meanwhile, which consequently accelerates G1/S phase transition and uncontrolled proliferation. At last, CD317 promotes HCC development.

Discussion

EGFR was among the very first RTKs that were identified and is frequently dysregulated in tumors (5, 42). As such, EGFR has been extensively studied as a prototype for RTK-mediated signaling and a target for cancer therapy (5, 9, 42). Here we reveal that the activation of EGFR is controlled via CD317-mediated release from the lipid rafts (Fig. 5C). This finding has important implications in the development of more effective treatments for EGFR-driven tumors.

The activation mechanism of EGFR (and the other EGFR/ErbB family members) is unique among RTKs in several important aspects. The ligands for EGFR are monomers, rather than dimers, and they promote receptor dimerization by inducing a dramatic conformational change that exposes a dimerization region (43). The subsequently EGFR activation involves the formation of an asymmetric dimer of the intracellular kinase domain, instead of auto-phosphorylation in the activation-loop as seen in the other RTKs (43). Importantly, EGFR is associated from lipid raft, and its activation requires its release from these highly organized membrane microdomains (15). Although the molecular basis for this requirement remains unclear, the dramatic conformational changes required for the activation of EGFR might be constrained in lipid rafts.

The organizational principle of lipid rafts, as well as the localization of proteins in and out of these ordered lipid domains, is poorly defined. Nevertheless, the ability of CD317 to release EGFR from lipid rafts is likely related to its unique topology. CD317 is thought to be associated with lipid rafts via the GPI anchor, but its TM domain is likely anchored outside lipid rafts (19, 21). Moreover, the rigid CD317 dimers formed by the coiled-coil extracellular domain can further dimerize through the anti-parallel association of the N-terminal region of the dimer (17). As such, CD317 can form a tetrameric complex that may bring micro-lipid rafts close to each other while, at the same time, preventing their coalescing into large assemblies. This may facilitate the release of EGFR into the space between lipid rafts. An alternative, but not mutually exclusive, scenario may be related to the recently-identified palmitoylation of EGFR. Proteins modified by palmitate, like GPI-anchored proteins, are often found in lipid rafts. Interestingly, a recent study showed that EGFR is modified by the palmitoyltransferase DHHC20 in the intracellular tail, which enables the insertion of the disordered region C-terminal to the kinase domain into the plasma membrane (44). Presumably, the C-terminal region of EGFR may insert into lipid rafts, impeding EGFR activation. CD317 might inhibit EGFR palmitoylation or increase its de-palmitoylation, for example, by influencing the interaction of EGFR with acyl-transferases or acyl-protein thioesterases. Regardless of the mechanism, CD317-mediated release of EGFR from lipid rafts likely represents a previously unrecognized, important mode of regulation. Further characterization of this regulation will likely help unravel intricate mechanisms that govern the activation of EGFR and the closely-related RTKs.

Constitutive signaling emanating from EGFR and other members of the EGFR/ErbB family contributes to a wide range of malignancies (8). Mechanisms underlying aberrant EGFR signaling include increased expression of EGFR, overproduction of its ligands, and mutations of EGFR especially in the extracellular and kinase domains (5, 45). Here we find that the levels of CD317 proteins are increased in HCC, and a survey of public database show that CD317 transcripts are enhanced in several cancers, including pancreatic and ovarian cancers, suggesting a mechanism for EGFR activation that is distinct from the canonical mode of dysregulation. These cancers with high CD317 expression showed poor prognosis (27, 29, 46, 47), but neutralizing monoclonal antibodies and small molecule tyrosine inhibitors of EGFR offer marginal therapeutic benefit for these tumors. Thus, our findings provide a rationale for targeting CD317 as alternative therapy strategy for EGFR-driven tumors. In this context, it is noted that monoclonal antibodies for CD317 have been generated and tested in animal models for multiple myeloma (31, 32). These antibodies may be applied to treat cancers with CD317 upregulation. Moreover, as shown recently, activation of EGFR via de-palmitoylation renders tumor cells addicted to EGFR, creating a vulnerability (44). Upregulation of CD317 may induce a similar reliance on EGFR signaling, hence sensitizing tumor cells to therapies targeting EGFR. Therefore, for tumors that are initially responsive to therapies targeting EGFR, combination with CD317-targeted therapies may help resolve the problem of resistance in the clinic.

Supplementary Material

Significance:

Activation of EGFR by CD317 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells suggests CD317 as an alternative target for treating EGFR-dependent tumors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Witze for helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (81373112, 81701559) to X. Wan and G. Zhang respectively; the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2016M602541) to G. Zhang; Special Funds for Major Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (2013A022100037), Shenzhen Special Funds for Industry of the Future (Shenzhen municipal development and reform commission [2015] No. 971), and Shenzhen Basic Science Research Project (JCYJ20170413153158716) to X. Wan; and the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01CA182675 and R01CA184867) to X. Yang.

Abbreviations

- AIF

apoptosis inducing factor

- AREG

amphiregulin

- DAPI

4, 6-diamino-2-phenylindole

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- Co-IP

Co-immunoprecipitation

- MFI

Mean fluorescence intensity

- MβCD

methyl-β-cyclodextrin

- mRNA

messenger RNA

- MTT

3- (4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- qRT-PCR

quantitative real time polymerase chain reaction

- PI

propidium iodide

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- TGF-α

transforming growth factor-α

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Reference

- 1.Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65(2): 87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Farazi PA, DePinho RA. Hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis: from genes to environment. Nat Rev Cancer 2006; 6(9): 674–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Llovet JM, Zucman-Rossi J, Pikarsky E, Sangro B, Schwartz M, Sherman M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mederacke I, Schwabe RF. NAD(+) supplementation as a novel approach to cURIng HCC? Cancer Cell 2014; 26(6): 777–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2001; 2(2): 127–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castillo J, Erroba E, Perugorria MJ, Santamaria M, Lee DC, Prieto J, et al. Amphiregulin contributes to the transformed phenotype of human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 2006; 66(12): 6129–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med 2008; 358(11): 1160–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shostak K, Chariot A. EGFR and NF-kappaB: partners in cancer. Trends Mol Med 2015; 21(6): 385–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chong CR, Janne PA. The quest to overcome resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer. Nat Med 2013; 19(11): 1389–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buckley AF, Burgart LJ, Sahai V, Kakar S. Epidermal growth factor receptor expression and gene copy number in conventional hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2008; 129(2): 245–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whittaker S, Marais R, Zhu AX. The role of signaling pathways in the development and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2010; 29(36): 4989–5005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mallarkey G, Coombes RC. Targeted therapies in medical oncology: successes, failures and next steps. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2013; 5(1): 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mineo C, James GL, Smart EJ, Anderson RG. Localization of epidermal growth factor-stimulated Ras/Raf-1 interaction to caveolae membrane. J Biol Chem 1996; 271(20): 11930–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 2010; 327(5961): 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mineo C, Gill GN, Anderson RG. Regulated migration of epidermal growth factor receptor from caveolae. J Biol Chem 1999; 274(43): 30636–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert S, Ameels H, Gniadecki R, Herin M, Poumay Y. Internalization of EGF receptor following lipid rafts disruption in keratinocytes is delayed and dependent on p38 MAPK activation. J Cell Physiol 2008; 217(3): 834–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schubert HL, Zhai Q, Sandrin V, Eckert DM, Garcia-Maya M, Saul L, et al. Structural and functional studies on the extracellular domain of BST2/tetherin in reduced and oxidized conformations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(42): 17951–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Swiecki M, Scheaffer SM, Allaire M, Fremont DH, Colonna M, Brett TJ. Structural and biophysical analysis of BST-2/tetherin ectodomains reveals an evolutionary conserved design to inhibit virus release. J Biol Chem 2011; 286(4): 2987–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kupzig S, Korolchuk V, Rollason R, Sugden A, Wilde A, Banting G. Bst-2/HM1.24 is a raft-associated apical membrane protein with an unusual topology. Traffic 2003; 4(10): 694–709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swiecki M, Omattage NS, Brett TJ. BST-2/tetherin: structural biology, viral antagonism, and immunobiology of a potent host antiviral factor. Mol Immunol 2013; 54(2): 132–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Billcliff PG, Gorleku OA, Chamberlain LH, Banting G. The cytosolic N-terminus of CD317/tetherin is a membrane microdomain exclusion motif. Biol Open 2013; 2(11): 1253–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Evans DT, Serra-Moreno R, Singh RK, Guatelli JC. BST-2/tetherin: a new component of the innate immune response to enveloped viruses. Trends Microbiol 2010; 18(9): 388–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galao RP, Le Tortorec A, Pickering S, Kueck T, Neil SJ. Innate sensing of HIV-1 assembly by Tetherin induces NFkappaB-dependent proinflammatory responses. Cell Host Microbe 2012; 12(5): 633–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galao RP, Pickering S, Curnock R, Neil SJ. Retroviral retention activates a Syk-dependent HemITAM in human tetherin. Cell Host Microbe 2014; 16(3): 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cocka LJ, Bates P. Identification of alternatively translated Tetherin isoforms with differing antiviral and signaling activities. PLoS Pathog 2012; 8(9): e1002931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tokarev A, Suarez M, Kwan W, Fitzpatrick K, Singh R, Guatelli J. Stimulation of NF-kappaB activity by the HIV restriction factor BST2. J Virol 2013; 87(4): 2046–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fang KH, Kao HK, Chi LM, Liang Y, Liu SC, Hseuh C, et al. Overexpression of BST2 Is Associated With Nodal Metastasis and Poorer Prognosis in Oral Cavity Cancer. Laryngoscope 2014; 124(9): E354–E360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chiang SF, Kan CY, Hsiao YC, Tang R, Hsieh LL, Chiang JM, et al. Bone Marrow Stromal Antigen 2 Is a Novel Plasma Biomarker and Prognosticator for Colorectal Carcinoma: A Secretome-Based Verification Study. Dis Markers 2015; 2015: 874054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukai S, Oue N, Oshima T, Mukai R, Tatsumoto Y, Sakamoto N, et al. Overexpression of Transmembrane Protein BST2 is Associated with Poor Survival of Patients with Esophageal, Gastric, or Colorectal Cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24(2): 594–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gong S, Osei ES, Kaplan D, Chen YH, Meyerson H. CD317 is over-expressed in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but not B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 2015; 8(2): 1613–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kawai S, Yoshimura Y, Iida SI, Kinoshita Y, Koishihara Y, Ozaki S, et al. Antitumor activity of humanized monoclonal antibody against HM1.24 antigen in human myeloma xenograft models. Oncology Reports 2006; 15(2): 361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harada T, Ozaki S. Targeted Therapy for HM1.24 (CD317) on Multiple Myeloma Cells. Biomed Research International 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang G, Hao C, Lou Y, Xi W, Wang X, Wang Y, et al. Tissue-specific expression of TIPE2 provides insights into its function. Mol Immunol 2010; 47(15): 2435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yue X, Zhang Z, Liang X, Gao L, Zhang X, Zhao D, et al. Zinc fingers and homeoboxes 2 inhibits hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and represses expression of Cyclins A and E. Gastroenterology 2012; 142(7): 1559–70 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yoo H, Park SH, Ye SK, Kim M. IFN-gamma-induced BST2 mediates monocyte adhesion to human endothelial cells. Cell Immunol 2011; 267(1): 23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, Zhang G, Chen Q, Lin Y, Li J, Ruan Q, et al. CD317 Promotes the survival of cancer cells through apoptosis-inducing factor. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2016; 35(1): 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez-Caballero D, Zang T, Ebrahimi A, McNatt MW, Gregory DA, Johnson MC, et al. Tetherin inhibits HIV-1 release by directly tethering virions to cells. Cell 2009; 139(3): 499–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Billcliff PG, Rollason R, Prior I, Owen DM, Gaus K, Banting G. CD317/tetherin is an organiser of membrane microdomains. J Cell Sci 2013; 126(Pt 7): 1553–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harder T, Scheiffele P, Verkade P, Simons K. Lipid domain structure of the plasma membrane revealed by patching of membrane components. J Cell Biol 1998; 141(4): 929–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rollason R, Korolchuk V, Hamilton C, Jepson M, Banting G. A CD317/tetherin-RICH2 complex plays a critical role in the organization of the subapical actin cytoskeleton in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol 2009; 184(5): 721–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lambert S, Vind-Kezunovic D, Karvinen S, Gniadecki R. Ligand-independent activation of the EGFR by lipid raft disruption. J Invest Dermatol 2006; 126(5): 954–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitsudomi T, Yatabe Y. Epidermal growth factor receptor in relation to tumor development: EGFR gene and cancer. FEBS J 2010; 277(2): 301–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaplan M, Narasimhan S, de Heus C, Mance D, van Doorn S, Houben K, et al. EGFR Dynamics Change during Activation in Native Membranes as Revealed by NMR. Cell 2016; 167(5): 1241–1251 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Runkle KB, Kharbanda A, Stypulkowski E, Cao XJ, Wang W, Garcia BA, et al. Inhibition of DHHC20-Mediated EGFR Palmitoylation Creates a Dependence on EGFR Signaling. Mol Cell 2016; 62(3): 385–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gullick WJ. Prevalence of aberrant expression of the epidermal growth factor receptor in human cancers. Br Med Bull 1991; 47(1): 87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai DQ, Cao J, Li Z, Zheng X, Yao Y, Li WL, et al. Up-regulation of bone marrow stromal protein 2 (BST2) in breast cancer with bone metastasis. Bmc Cancer 2009; 9: 102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sayeed A, Luciani-Torres G, Meng ZH, Bennington JL, Moore DH, Dairkee SH. Aberrant Regulation of the BST2 (Tetherin) Promoter Enhances Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis Evasion in High Grade Breast Cancer Cells. Plos One 2013; 8(6): e67191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.