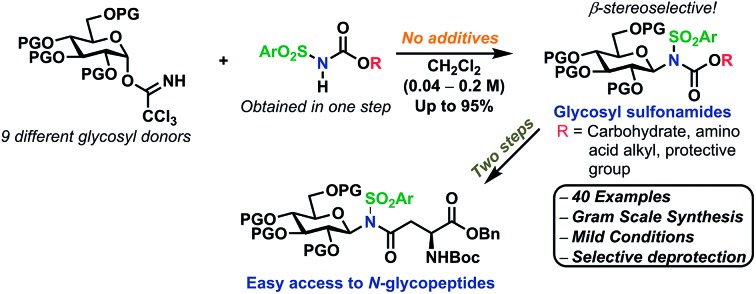

A stereoselective and self-promoted glycosylation for the synthesis of various N-glycosides and glycosyl sulfonamides from trichloroacetimidates is presented.

A stereoselective and self-promoted glycosylation for the synthesis of various N-glycosides and glycosyl sulfonamides from trichloroacetimidates is presented.

Abstract

A stereoselective and self-promoted glycosylation for the synthesis of various N-glycosides and glycosyl sulfonamides from trichloroacetimidates is presented. No additional catalysts or promoters are needed in what is essentially a two-component reaction. When α-glucosyl trichloroacetimidates are employed, the reaction resulted in the stereospecific formation of the corresponding β-N-glucosides in high yields at ambient conditions. On the other hand, when equatorial glucosyl donors were used, the stereospecificity decreased and resulted in a mixture of anomers. By NMR-studies, it was concluded that this decrease in stereospecificity was due to an, until now, unpresented anomerization of the trichloroacetimidate under the very mildly acidic conditions. The mechanism and kinetics of the glycosylations have been studied by NMR-experiments, which gave an insight into the activation of trichloroacetimidates, suggesting an SNi-like mechanism involving ion pairs. The scope of glycosyl donors and sulfonamides was found to be very broad including popular N-protective groups and common glycosyl donors of various reactivity. Peracetylated GlcNAc trichloroacetimidate could be used without the need for any promotors or additives and a tyrosine side chain was glycosylated as an N-glycosyl carbamate. The N-carbamates and the N-sulfonyl groups functioned as orthogonal protective groups of the N-glycoside and hence allowed further N-functionalization without risking mutarotation of the N-glycoside. The N-glycosylation was also performed on a gram scale, without a drop in stereoselectivity nor yield.

Introduction

Trichloroacetimidates (TCAs) remain one of the most popular glycosyl donors in catalytic glycosylations.1 Since the introduction of TCA donors by Schmidt,2 numerous Lewis- and Brønsted acids have been shown to catalyze their activation.2–4 In common for many of the methods is the formation of an oxocarbenium ion intermediate or similar, i.e. with no memory of the stereochemistry of the donor.5 The TCAs are synthesized from reacting the hemiacetal with trichloroacetonitrile under basic conditions and depending on the conditions, mainly the α- or the β-anomer can be synthesized.6–8 Since it is possible to access the TCAs stereoselectively, several researchers have been interested in utilizing this particular glycosyl donor in stereospecific glycosylations.9

Stereospecific glycosylations have previously been performed via pre-complexation in O-glycoside synthesis by using additives such as chloral,3 boron fluorides10 or silanes11 to complex the acceptor alcohol making it more acidic and hence able to activate the trichloroacetimidate. This method was however initially limited to a few glycosyl donor types and simple glycosyl acceptors. Still, the early results sparked a wide interest in this concept that has since led to substantial advances, which has recently been reviewed in detail.9,12

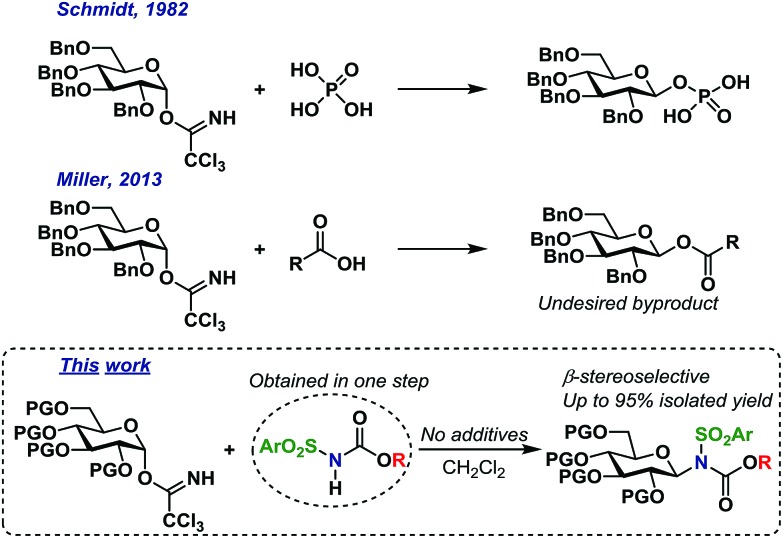

In the early eighties, the Schmidt group reported that certain carboxylic acids and phosphorous acid derivatives could activate the α-trichloroacetimidates and substitute these with inversion of stereochemistry (Scheme 1).13 The inversion of stereochemistry was explained by pre-complexation of the TCA donor and acid, leading to a pseudo six-membered transition state3 and a concerted mechanism, without the formation of an oxocarbenium intermediate.

Scheme 1. Self-promoted O- and N-glycosylations.

Likewise, the Miller group have shown more recently14 that a wide range of carboxylic acids can act as catalytic activators of TCA donors, concluding that the catalytic efficiency of these catalysts was inversely proportional to their pKa-value; carboxylic acids with higher pKa-values simply resulted in self-condensation of the catalyst and TCA donor, thus yielding undesired glycosyl esters. It is important to note that these glycosyl ester by-products were produced with inverted stereochemistry compared to the TCA donors (Scheme 1). There have been numerous reports of the in situ formation of several different intermediates,15 but the concept of self-condensation of the glycosyl donor and an acidic reactant in the context of glycoside synthesis has only received little attention. However, it seems quite clear that this reaction could have interesting applications considering the apparent stereospecific formation of the undesired by-products.

As part of our ongoing interest in stereospecific catalytic glycosylations, we have studied acidic N–H groups as potential self-promoters in glycosylation (Scheme 1).

Glycosyl sulfonamides are an important group of compounds that have been shown to be carbonic anhydrase inhibitors16–20 and more recently, the antitumor activity of this class of compounds has been recognized.17,21,22 Their synthesis has mainly been from reduction of the corresponding β-glycosyl azide,23–27 reductive amination of the lactol,28 from 1,2 diols using Burgess reagent,29 from glycals16,19,21,30–36 or via anomeric substitution under strongly acidic conditions.17,37,38 Thus, it would be of interest to get access to this class of compounds via a milder, higher-yielding route.

The Miller group have reported that sulfonamides are sufficiently acidic to act as catalytic activators of TCA glycosyl donors, enabling the synthesis of O-glycosides in good yields, albeit with low stereoselectivity.39 This inspired us to develop a glycosylation procedure in which a glycosyl TCA donor is condensed with a sulfonamide, leading to the stereoselective formation of the desired N-glycosides. This reaction takes place in common organic solvents without the addition of any additives and is, to the best of our knowledge, the first example of a self-promoted N-glycosylation. This has resulted in the stereoselective formation of various glycosyl sulfonamides in high yields on a gram scale, including the synthesis of an amino acid-functionalized N-glycoside. We believe that this method serves as the simplest possible method for selective N-glycosylations and seek to further broaden its scope and possibilities in future studies.

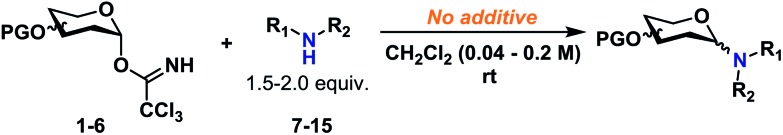

Synthesis of N-glycosides

Initial glycosylation reactions

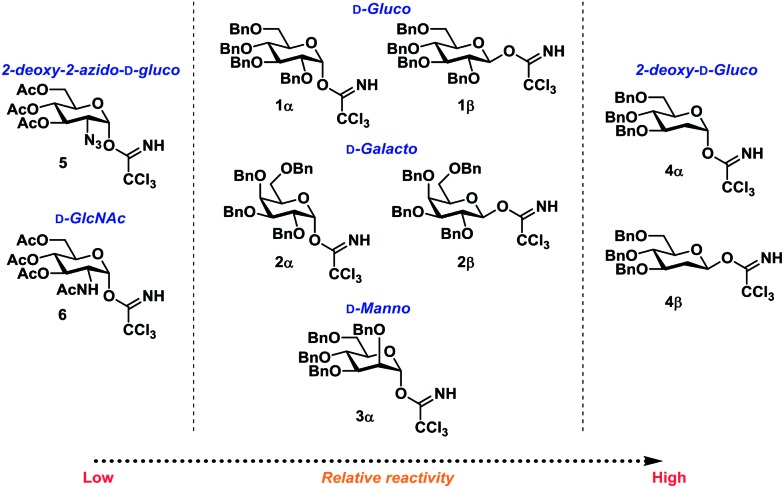

Glycosyl donors 1–6 (Chart 1) were investigated in a series of self-promoted N-glycosylations to investigate the effect of various protecting group patterns, donor reactivities and configurations; 1–3 represents the three most common glycosyl donors employed in carbohydrate synthesis, deoxysugar 4 represents a highly reactive glycosyl donor whereas donors 5 and 6 exemplifies unreactive, but synthetically interesting glycosyl donors.

Chart 1. Glycosyl donors used in this study.

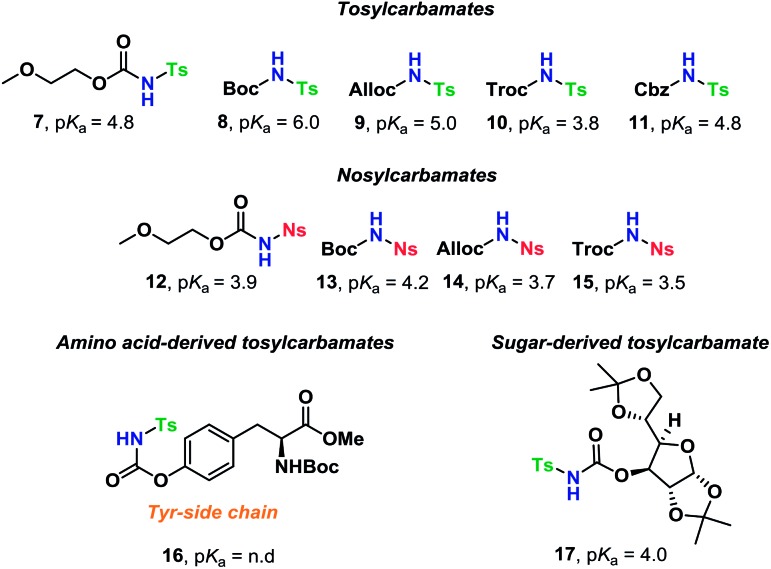

The scope of glycosyl acceptors consisted of various functional groups (Chart 2), namely tosylcarbamates 7–11, 16 and 17 and nosylcarbamates 12–15. These carbamates are selected for various reasons; 7–15 represent a wide pKa-range, which could give an indication of the limits of the self-promoted glycosylation procedure, but also vary significantly in size, allowing an investigation of how steric bulk influences this particular glycosylation reaction. Also, it was found that both the tosyl- and nosyl groups can be selectively removed after the glycosylation using two different procedures, further widening the scope of post-glycosylational N-functionalization (vide infra).

Chart 2. Glycosyl acceptors employed for self-promoted N-glycosylations.

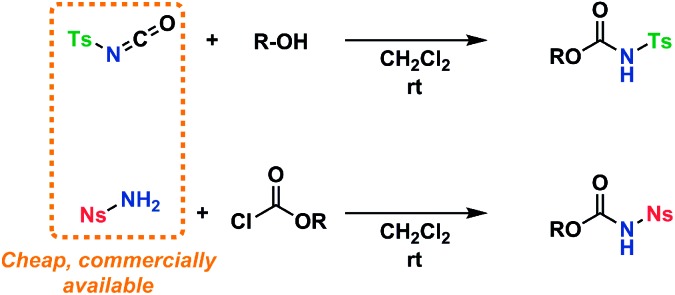

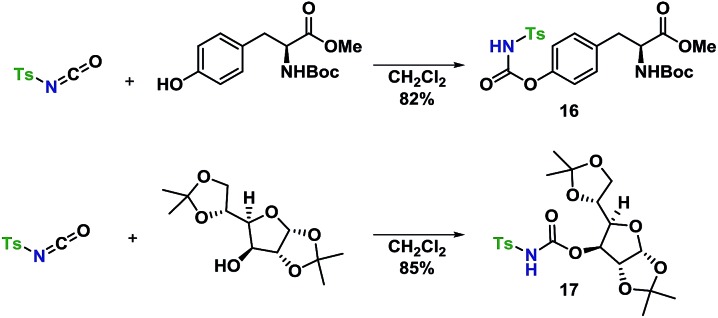

An amino acid-derived glycosyl acceptor was also investigated in this study, namely tyrosine-derivative, 16. Also carbamate 17 was found as an interesting O-functionalized carbamate for the self-promoted glycosylations. Compounds 7–11, 13–15, 16 and 17 were all obtained in a single step from commercially available starting materials (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. General reaction scheme for the preparation of tosylcarbamates and nosylcarbamates.

Certain trends were clear from the initial series of glycosylations carried out from the α-glycosyl donors (Table 1). Glycosylations with 1α (entries 1–10) were essentially β-stereospecific, resulting in yields of 78–95% at various concentrations. Even notoriously unreactive glycosyl donors such as 5 and 6 (entries 25–27) served as suitable glycosyl donors in this glycosylation procedure, both resulting in formation of the corresponding β-glycosides in good yields, albeit at elevated temperatures. No formation of the common oxazoline by-product40,41 was observed during the glycosylation with donor 6.

Table 1. Overview of initial glycosylations employing α-TCA donors 1–6.

| ||||||

| Entry | Donor | Acceptor | t (h) | c a (M) | Yield b (%) | α/β c |

| 1 | 1α | 7 | o.n. | 0.15 | 92 | 0 : 100 |

| 2 | 1α | 9 | 16 | 0.1 | 80 | 0 : 100 |

| 3 | 1α | 9 | 16 | 0.2 | 90 | 0 : 100 |

| 4 | 1α | 10 | o.n. | 0.2 | 95 | 0 : 100 |

| 5 | 1α | 11 | o.n. | 0.2 | 93 | 0 : 100 |

| 6 | 1α | 12 | o.n. | 0.08 | 67 | 1 : 99 |

| 7 | 1α | 14 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 62 | 6 : 94 |

| 8 | 1α | 15 | 1 | 0.04 | 85 | 0 : 100 |

| 9 | 1α | 15 | 1 | 0.08 | 95 | 6 : 94 |

| 10 | 1α | 15 | 0.75 | 0.2 | 78 | 6 : 94 |

| 11 | 1α | 8 | 24 | 0.2 | 35 d | 0 : 100 d |

| 12 | 1α | 13 | 4 | 0.2 | 33 d | n.d. d |

| 13 | 1α | 13 | o.n. | 0.05 | 79 d | 0 : 100 d |

| 14 | 2α | 9 | 18 | 0.2 | 63 | 29 : 71 |

| 15 | 2α | 11 | 16 | 0.2 | 61 | 34 : 66 |

| 16 | 2α | 14 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 79 | 25 : 75 |

| 17 | 2α | 15 | 3 | 0.04 | 90 | 26 : 74 |

| 18 | 2α | 15 | 5 | 0.2 | 90 | 33 : 67 |

| 19 | 3α | 7 | 24 | 0.2 | 78 | 100 : 0 |

| 20 | 3α | 9 | 20 | 0.2 | 64 | 100 : 0 |

| 21 | 3α | 10 | o.n. | 0.2 | 74 | 100 : 0 |

| 22 | 3α | 11 | 24 | 0.2 | 72 | 100 : 0 |

| 23 | 3α | 14 | 6.5 | 0.2 | 79 | 100 : 0 |

| 24 e | 3α | 14 | o.n. | 0.2 | 66 | 100 : 0 |

| 25 f | 5 | 15 | 3.25 | 0.2 | 70 | 0 : 100 |

| 26 f | 6 | 14 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 44 | 19 : 81 |

| 27 f | 6 | 15 | 1.5 | 0.2 | 45 | 5 : 95 |

aConcentration of glycosyl donor.

bIsolated yield.

cDetermined from crude 1H-NMR.

dThe Boc-derivatives 8 and 13 were found to give rise to various by-products, making it challenging to precisely determine yield and selectivity.

eReaction was stirred at –78 °C for 3 h and then allowed to reach 0 °C.

fReaction carried out in 1,2-dichloroethane at 80 °C.

Boc-derivatives 8 and 13 (Table 1, entries 11–13) were unsuitable for this type of reaction and led to the formation of by-products which made both purification and determination of stereoselectivity troublesome. This indicated a certain limit for the size of the N-substituents for this particular reaction to proceed successfully. Despite this, the desired N-glycosides were obtained, although in relatively lowered yields.

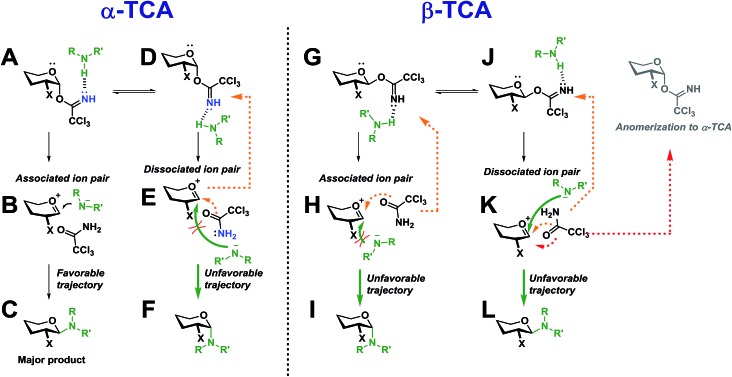

Glycosylations involving donor 2α (entries 14–18) proceeded in high yields of 61–90%, with a clear preference for the formation of the desired β-glycoside. Glycosylations with mannopyranosyl TCA donor 3α were α-selective, indicating that the formation of 1,2-cis glycosidic linkages were likely disfavored by the steric factors due to the bulkiness of the acceptors. This was also the case when the same glycosylation was carried out at lowered temperature (entry 24). The steric bulk of the acceptors was also apparent when analyzing the 1H-NMR spectra of the α-glycosides since these were found to adopt a skew boat conformation, whereas all the β-glycosides all adopted a 4C1-like conformation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Observed conformations of N-glycosides determined from 1H-NMR coupling constants.

It was investigated whether altering the reaction concentration would have an effect on the yield and selectivity (Table 1). This gave rise to alternating variations in yield depending on which acceptor was used, but the stereoselectivity seemingly remained unaffected by the change in concentration.

In practice, this glycosylation method was incredibly easy as it only required mixing two compounds in CH2Cl2. Furthermore, the excess of acceptor could be removed by an extraction with 1 M aq. NaOH.42 The excess of acceptor could alternatively be recovered by flash column chromatography.

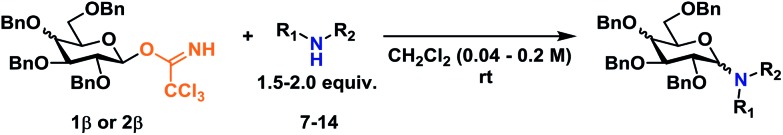

Next, it was investigated whether a glycosylation with β-TCA glycosyl donors would produce the corresponding α-glycosides with a similar stereospecific inversion of stereochemistry as was found in the initial glycosylations with α-TCA donors. These results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Overview of glycosylations employing β-TCA donors 1 and 2.

| ||||||

| Entry | Donor | Acceptor | t (h) | c a (M) | Yield b (%) | α/β c |

| 1 | 1β | 7 | 4 d | 0.15 | 96 | 66 : 34 |

| 2 | 1β | 9 | 16 | 0.2 | 73 | 43 : 57 |

| 3 | 1β | 10 | o.n. | 0.2 | 80 | 50 : 50 |

| 4 | 1β | 11 | o.n. | 0.2 | 82 | 45 : 55 |

| 5 | 1β | 12 | 24 | 0.04 | 45 | 76 : 24 |

| 6 | 1β | 14 | 4.5 | 0.2 | 78 | 52 : 48 |

| 7 | 2β | 7 | o.n. | 0.2 | 71 | 77 : 23 |

| 8 | 2β | 14 | 2.5 | 0.2 | 67 | 80 : 20 |

aConcentration of glycosyl donor.

bIsolated yield.

cDetermined from crude 1H-NMR.

Generally, the glycosylations proceeded in high yields of 67–82% and with a higher degree of α-selectivity. It was clear that although a significantly higher selectivity for the desired α-glycosides was achieved, the stereospecificity was lower than in the previous glycosylations summarized in Table 1, indicative of unfavorable configuration of 1,2-cis-glycosides with bulky glycosyl acceptors. It is also noteworthy that the galactosylations (entries 7 and 8) proceeded with a higher degree of stereospecificity than the corresponding glucosylations (entries 1–6).

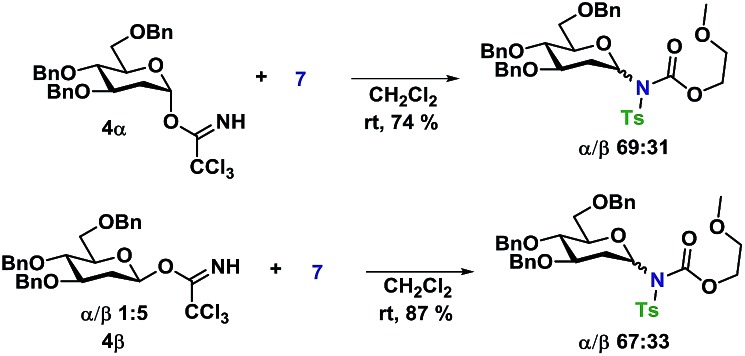

In an attempt to rule out whether it was a sterically repulsive effect from the C2-substituents that was inhibiting the formation of 1,2-cis glycosidic linkages, 2-deoxyglucosyl TCA donors 4α and 4β were synthesized (Scheme 3). It was however found that both glycosylations gave rise to essentially identical stereoselectivity independent on the configuration of the glycosyl donor, which strongly suggests the formation a common intermediate, which reacts with a reaction rate near the diffusion limit, seemingly negating the stereochemical information from the glycosyl donors.

Scheme 3. Glycosylations employing 2-deoxy-glycosyl TCA donors 4α and 4β.

Glycosylations with functionalized carbamates

With a well-established glycosylation procedure in hand, it was investigated whether this glycosylation strategy could be employed to make biologically relevant model-compounds derived from carbohydrates. It was found that the general conditions for synthesizing the carbamate acceptors (Scheme 2) were also suitable for the synthesis of two amino acid- or carbohydrate-derived carbamates, 16 and 17 from cheap, commercially available starting materials (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of carbamates 18 and 19.

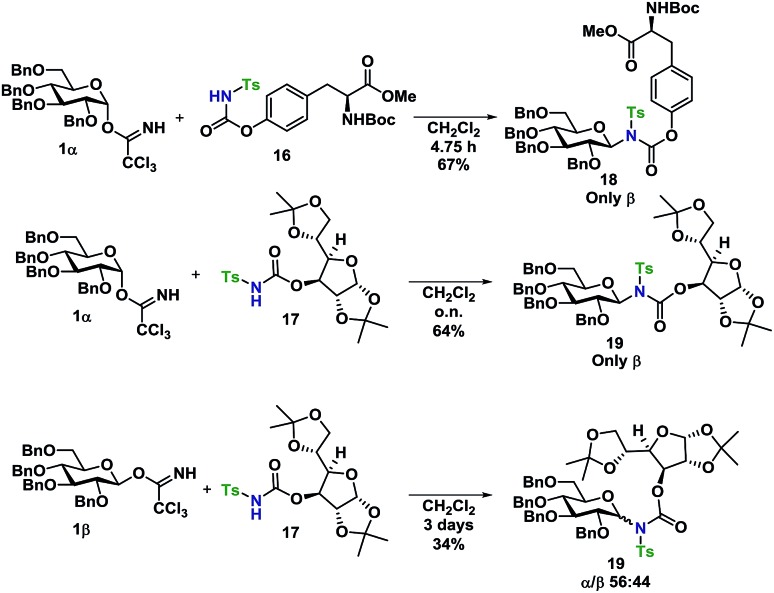

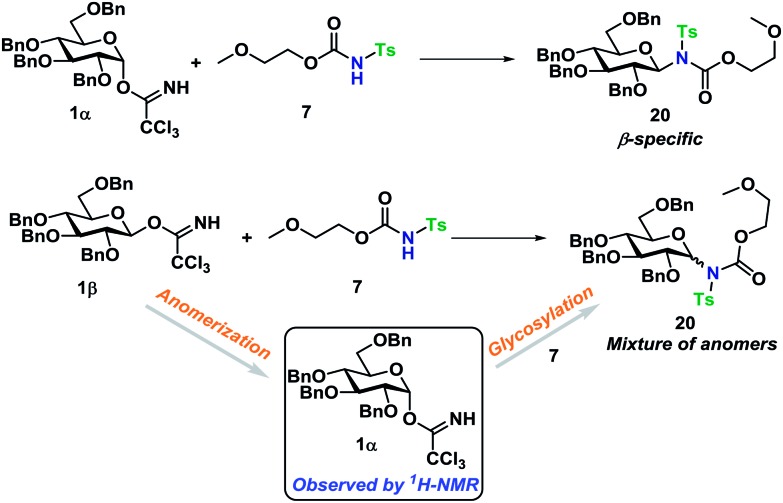

Glycosyl acceptors 16 and 17 were found to perform convincingly in glycosylations, following similar conditions as previously described for the glycosylations in Tables 1 and 2, underlining that even in these more complex systems, there was still no need for further additives. The glycosylations with TCA donor 1α (Scheme 5) proceeded with complete β-stereoselectivity and in high yields, whereas the glycosylation starting from 1β was reacting slower and resulted a mixture of anomers.

Scheme 5. Glycosylations of carbamates 18 and 19 with donors 1α and 1β.

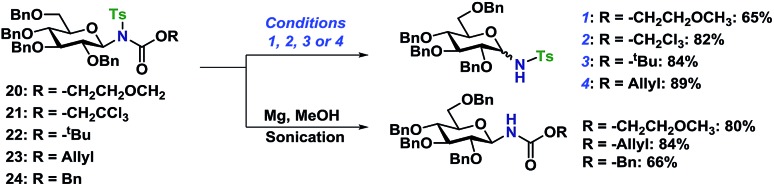

Orthogonal deprotections of N-glycosides

With access to the fully protected or selectively functionalized N-glycosides, the orthogonality of the protective groups was evaluated. Initially, the deprotection of the tosylderivatives was investigated (Scheme 6). Using Zemplén conditions on 20 (K2CO3 in MeOH) under reflux resulted in the deprotected N-glycoside as a 1 : 1 mixture of anomers. The same results and ratio was achieved when using an anomeric mixture of 20. The in situ anomerization was confirmed by applying the same conditions on the pure β-anomer of the desired glycosyl sulfonamide, which again gave the same anomeric ratio. The anomeric ratio was eventually 1 : 0.6 after five days of heating (see ESI†).

Scheme 6. Orthogonal deprotection of tosyl-protected N-glycosides. Reaction conditions: (1) K2CO3 (2 equiv.), 0.02 M in MeOH, reflux, 4 h. (2) Zn (8 equiv.), 0.12 M in AcOH, 70 °C, 2 h. (3) TFA (20 equiv.), 0.03 M in CH2Cl2, rt, 8 h. (4) PhSiH3 (4 equiv.), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.05 equiv.), 0.75 M in CH2Cl2, rt, overnight.

The orthogonal N-deprotections were then studied using different carbamates, which are more commonly used as protective groups. The Troc protective group in 21 was deprotected using Zn in AcOH at 70 °C giving the glycosyl sulfonamide in 82% yield albeit still with some anomerization (α/β 28 : 72). The Boc protective group in 22 was deprotected under acidic conditions, TFA in CH2Cl2, and gave the glycosyl sulfonamide in 84% as a mixture of anomers. The problems with anomerization under acidic or basic conditions could be overcome by using the Alloc protective group (23), as it was deprotected under milder conditions using palladium catalysis in combination with a mild acid or nucleophile.29 The removal of the Alloc protective group was performed on a variety of substrates, with different stereochemistry, and both the Ts or Ns group. No anomerization was observed under these conditions and the glycosyl sulfonamides could be isolated in high yields (89 and 87% respectively, Schemes 6 and 7). With the protocols for carbamate deprotections in place, the attention was turned to the desulfonylation to give the corresponding N-glycosyl carbamates.

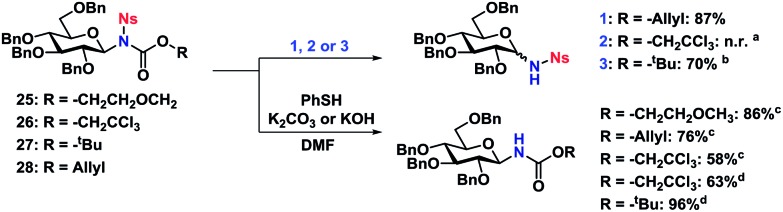

Scheme 7. Orthogonal deprotection of nosyl-protected N-glycosides. Reaction conditions (1) sodium p-toluenesulfinate (1.1 equiv.), Pd(PPh3)4 (0.1 equiv.), 0.012 M in MeOH/THF 1 : 2, rt, 1.5 h. (2) Zn (20 equiv.), 0.025 M in AcOH, rt, 0.5 h. (3) TFA (20 equiv.), 0.4 M in CH2Cl2, rt, o.n. aResulted in reduction of the Ns nitro group to the corresponding amine. bGlycosylation and deprotection carried out in a single step, 70% overall yield. cK2CO3 used as base. dKOH used as base.

The Ts-group has a somewhat bad reputation as an N-protective group and the first attempts to remove it were indeed not very successful. As an example, deprotection using lithium naphthalide only gave 22% of the desired product. Instead, employing the protocol by Nyasse et al.43 turned out to be the solution (Scheme 6). Magnesium turnings were used as the reductant in anhydrous MeOH at rt and under these mild conditions, the desired carbamate-protected N-glycosides could be obtained in high yields. The major byproduct was found to be the glycosyl sulfonamides, i.e. carbamate deprotection, which increased if water was present. The reductive removal of the Ts-group worked well on the various N-glycosides with different carbamate protective groups. Removal of the Ns-group (Scheme 7) was more straightforward using thiophenolate in DMF, employing either K2CO3 or KOH as the base. This reaction was generally fast and clean giving isolated yields in the range of 58–96% depending on the conditions. Caution should however be taken not to leave the reaction at prolonged reaction times, as anomerization eventually takes place.

The carbamate-deprotection of nosyl-protected N-glycosides 25–28 (Scheme 7) proved to be somewhat more challenging compared to the tosyl-derivatives, since the Ns-group is generally more sensitive towards various reaction conditions. Thus it was reduced to the amine with Zn in AcOH when trying to remove the Troc group in 26. The deprotection of the Alloc- and Boc-groups (27 and 28 respectively) was however efficient, resulting in yields of 70–77%. Thus it seemed that for both tosyl- and nosyl-protected N-glycosides, the ideal combination with both was the Alloc protective group.

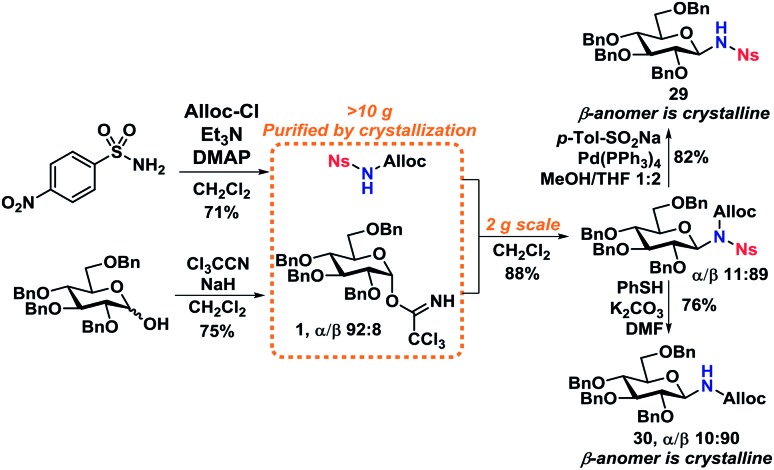

Scale-up and N-functionalization

With optimized deprotection-procedures in hand, a significant upscaling of the reaction was carried out (Scheme 8). It was found that N-deprotected glycosides 29 and 30 could be obtained in 82% and 76% yields accordingly in a glycosylation/deprotection procedure following optimized reaction conditions from Scheme 6. Furthermore, the two products, 29 and 30, are crystalline which simplifies purification and isolation on a large scale, yielding two ideal starting materials for further N-functionalization.

Scheme 8. Gram-scale synthesis of 1-amino-1-deoxy-glycosides.

Worth mentioning is the formation of a minor byproduct during the Alloc-deprotection to give 29, namely allyl p-tolyl sulfone,44via a sulfonate-sulfone rearrangement that has previously been shown to take place under similar conditions.45,46

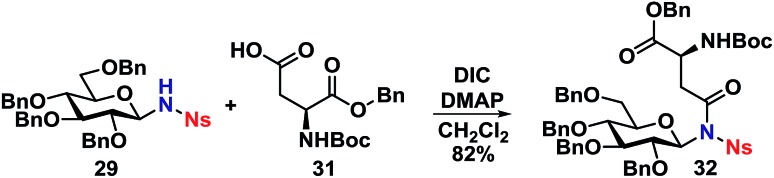

With the deprotected N-glycoside 29 in hand, it was investigated whether this would be a suitable starting material for synthesis of glycopeptides. Several methods were investigated, but it was found that the NH of 29 could undergo a DIC coupling with a commercially available aspartic acid building block 31, facilitating the synthesis of 32 in an 82% yield with no anomerization taking place. This underlines the efficiency of the self-promoted glycosylations, since relatively complex compounds such as 32 can be achieved in very few simple and high-yielding steps (Scheme 9).

Scheme 9. Synthesis of glycopeptide model 32.

Mechanistic studies

Reaction kinetics

Having established a solid understanding of the scope of the reaction, the reaction mechanism was scrutinized via NMR-experiments and kinetic studies. Since the glycosyl acceptors all have different pKa-values ranging from 3.5–6.0, a series of glycosylations were followed by 1H-NMR to clarify whether the pKa-values corresponded to the observed rate of reaction. All reactions follow a first-order kinetic profile in the glycosyl donors (see ESI†) and the relative rate constants are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Comparison of relative rate constants and pKa-values of glycosyl acceptors.

| Acceptor | pKa | k rel a | R 2 b |

| 7 | 3.9 | 0.019 | 0.99 |

| 9 | 5.0 | 0.014 | 0.99 |

| 10 | 3.8 | 0.53 | 0.99 |

| 11 | 4.8 | 0.15 | 0.95 |

| 13 | 4.2 | 0.0053 | 1.00 |

| 14 | 3.7 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 15 | 3.5 | ∼25 c | — c |

aRelative rate. krel for consumption of 1α under reaction with acceptor 14 set to 1.00. Determined from 1H-NMR in CD2Cl2 at 300 K using mesitylene as internal standard. Donor concentration was 0.032 mM and 1.5 equiv. of acceptor was used in all cases.

bLinear fit to ln[1α] vs. time.

cStarting material was already consumed when two 1H-NMR spectrums had been acquired.

From Table 3 it is clear that there is no clear correlation between the acidity of the glycosyl acceptors and the relative rate of glycosylation, which underlines that steric parameters may be similarly important. It is however noteworthy that all the nosyl-derivatives 14–15 react considerably faster than the tosyl-derivatives 7–11.

To determine the overall reaction order, a series of glycosylation reactions with varying concentrations were carried out and followed by 1H-NMR-spectroscopy. Acceptor 10 was chosen as the model compound for this experiment as it expressed mid-range reactivity according to Table 3. When doubling the concentration of either 1α or 10, the estimated initial rate of product formation was approximately doubled, hence suggesting a second order reaction mechanism. Graphs S1 and S2 (see ESI†) clearly demonstrates the dependence of initial rates on changing concentrations of 1α and 10 (Table 4).

Table 4. Overview of estimated initial rates at various concentrations.

| c ( 1α ) (mM) | c ( 10 ) (mM) | v (initial) a (mM hr–1) |

| 29 | 58 | 15 |

| 58 | 58 | 25 |

| 117 | 58 | 58 |

| 234 | 58 | 157 |

| 58 | 29 | 15 |

| 58 | 117 | 55 |

| 58 | 234 | 162 |

aDetermined from 1H-NMR in CD2Cl2 at 300 K using mesitylene as internal standard.

NMR-studies

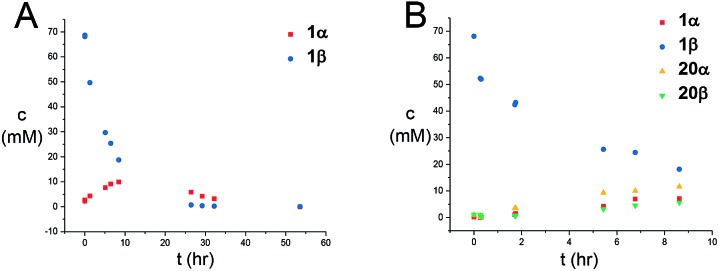

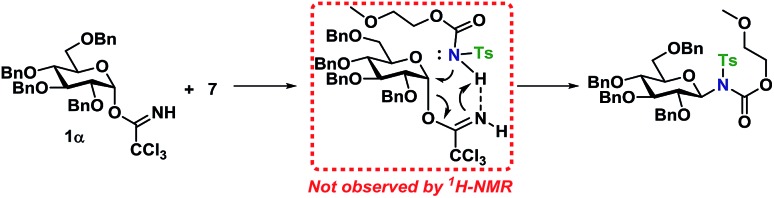

Next, the reaction mechanism was investigated by 1H-NMR. It was decided to use carbamate 7 as a model acceptor since this particular acceptor reacted somewhat slowly, thus being suitable for the 1H-NMR time scale. Furthermore, the progress of the reaction could also easily be determined due to the –OCH3 group, which is distinguished from other signals in the crude spectra. The glycosylation of glycosyl donors 1α and 1β were followed by 1H-NMR at room temperature to identify possible intermediates or by-products formed during the reaction. The glycosylation of 1α proceeded as expected (Scheme 10), yielding only the desired product 20β. However, during the glycosylation of 1β, it was found that the β-TCA donor partly anomerized in situ to the corresponding α-TCA donor as a competing reaction, which was then glycosylated, yielding the β-N-glycoside (Fig. 2A and B). This in situ anomerization is unprecedented in organic solvents and has only previously been reported by Poletti when performing glycosylations in ionic liquids.47,48 Thus, it seems that the β-TCA donor reacts via two competing reaction pathways: either it reacts in a glycosylation, apparently yielding primarily the α-N-glycoside, but the competing reaction yields the α-TCA donor that is then converted exclusively into the β-N-glycoside, thus giving rise to anomeric mixtures of 20α and 20β.

Scheme 10. Observed difference in the glycosylation behavior of glycosyl donors 1α and 1β. Conditions: T = 300 K 0.075 M in dry, neutralized CDCl3 (passed through basic Al2O3) using 3 equiv. of acceptor 7.

Fig. 2. (A) Graphical illustration of the anomerization of 1β to 1α under the reaction conditions shown in Scheme 10. (B) Graphical illustration of the formation of either 20α or 20β during the anomerization of 1β. Mesitylene was used as an internal standard for concentration determination.

The mechanistic details of the glycosylation reaction have been discussed thoroughly for more than half a century.49–51 Recently, the interest in mechanistic studies in glycosylation chemistry received renewed interest with the appearance of new methods for selective glycosylations, suggesting SN2-like mechanisms.5,52 Also, the conformation of the oxocarbenium ion has been found to influence the stereochemical outcome of glycosylations.53

From the results of the mechanistic investigation, it is clear that the glycosylation of the α- and the β-TCA donors do not necessarily pass through the same intermediate and hence can follow different reaction paths. In many cases, the reaction gave inversion of stereochemistry, which was most pronounced using the axial TCA in 1,2-cis glycosyl donors. On the other hand, the equatorial TCA donors gave lower selectivity, which could be because of certain steric requirements for a donor–acceptor complex. Therefore, it was investigated whether a complex between donor 1α and acceptor 7 was initially formed during the glycosylations (Scheme 11). However, no change in the 1H-NMR spectrum of either 1α or 7 was observed when titrating the donor with acceptor (0.2–1.0 equiv., see ESI†), ruling out the formation of a stable donor–acceptor complex.

Scheme 11. Proposed complex favoring an SN2-like reaction mechanism.

The kinetics are of first order for both glycosyl donor and acceptor. The selectivity observed, with inversion of stereochemistry, suggests an SN2-like reaction, which could be on the protonated acetimidate, i.e. involving associated ion-pair and therefore an SNi-type of mechanism as recently suggested by Tanaka et al. for a glycosylation reaction.54 When the solvent polarity is increased, e.g. by using acetonitrile (Scheme 12), 33 is formed. This indicates the formation of a glycosyl cation, and competition from the solvent when the ion-pair is more dissociated. It should be emphasized that the reaction mechanism can change and these conditions cannot be directly transferred to reactions in CH2Cl2.

Scheme 12. Trapping of glycosyl cation by using acetonitrile as the solvent.

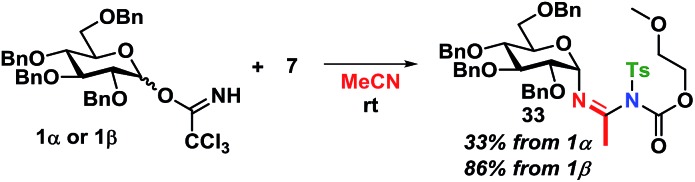

Two simplified mechanistic scenarios for both the α- and β-anomer are shown in Scheme 13. Two different conformers (A and D) have been proposed for the α-TCA donors of which A has previously been found to be energetically favorable.3 Upon activation of A, the associated ion pair, B, will be formed. In this ion pair, the amide ion is in close proximity to the glycosyl cation intermediate, and should thus react to form C much more readily than its counterpart E in which the nucleophilic attack is sterically hindered by the C-2 substituent, blocking the required trajectory leading to F.

Scheme 13. Proposed intermediates during an SNi-like glycosylation with both α- and β-TCA glycosyl donors.

Also, the back reaction to form the TCA donor D could be a competing reaction (orange dotted arrow). This can explain why such a high preference for the formation of 1,2-trans-glycosides was found for both the gluco and galacto α-TCA donors. The manno donors (not shown) also yielded 1,2-trans-glycosides, as the associated ion pair B would be obscured by the axial C-2 substituent, instead making the dissociated ion pair E the more favorable intermediate leading to F.

For the β-TCA donors (Scheme 13, right side), two different conformers (G and J) are also presented. Here, however, the associated ion pair H will not be as favorable as its counterpart B since the C-2 substituent of H will block the trajectory of the incoming nucleophile, impeding the formation of I. On the other hand, the dissociated ion pair, K, should have less hindered trajectory for the nucleophilic attack, leading to L, but since the nucleophile will be further away from the glycosyl cation, and possibly hydrogen-bonded to the leaving group, the anomerization to the corresponding α-TCA donor (as observed by 1H-NMR) will be a competing reaction. Thus, it seems that both reaction pathways leading to products I and L will have certain drawbacks, possibly explaining the lowered stereoselectivity observed during glycosylations with β-TCA donors. The lowered stereoselectivity is also a natural consequence of the observed formation of the α-TCA as this will result in a loss of stereochemical information from the glycosyl donor.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed a self-promoted N-glycosylation using TCA donors and easily obtainable N-sulfonyl carbamates. It has been shown that tosylcarbamates, easily obtained from amino acids or carbohydrates, are capable of reacting in this self-promoted glycosylation, which could be of great interest in the glycosylation of e.g. peptide side chains or other biomolecules. The obtained N-glycosides are stable and hence could be a useful linker for biomolecules in general as they can be used for classic coupling reactions with carboxylic acids, giving glycosyl amides in high yields.

Besides the very mild reaction conditions, it was found that the reaction often was stereospecific, especially when substituting an axial TCA, even in the absence of neighboring group participation. In addition, this glycosylation method allows for the orthogonal deprotection of the N-glycosides, enabling easily accessible 1-amino-1-deoxy glycosides for further functionalization.

The selectivity and reaction mechanism has been investigated on basis and NMR-experiments and an SNi-like mechanism has been proposed.

The self-promoted glycosylation was shown to allow acceptors with a wide range of pKa-values (3.5–6.0) and very different steric bulk. It was also shown that the procedure was easily scaled up to a column-free procedure on multiple grams without observing a drop in selectivity and yield, which underlines that this glycosylation protocol represents a way of simplifying N-glycosylations, whilst still achieving high yield and selectivity.

It is our belief that this method could prove very valuable in the synthesis of various biomolecules and a further investigation into the scope of this method for the functionalization of proteins and other relevant biomolecules is currently on-going in our laboratory.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Christian Tortzen for his help with NMR-experiments. Professor Richard R. Schmidt is acknowledged for fruitful discussions. PM acknowledge grant no. POWR.03.02.00-00-I026/16 co-financed by the European Union through the European Social Fund under the Operational Program Knowledge Education Development, for support. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their comments and valuable input for the discussion of the mechanistic studies.

Footnotes

†Electronic supplementary information (ESI) available. See DOI: 10.1039/c9sc00857h

References

- Nielsen M. M., Pedersen C. M. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:8285–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R., Michel J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1980;19:731–732. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R., Gaden H., Jatzke H. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:327–329. [Google Scholar]

- Urban F. J., Moore B. S., Breitenbach R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4421–4424. [Google Scholar]

- Adero P. O., Amarasekara H., Wen P., Bohé L., Crich D. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:8242–8284. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R., Michel J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:821–824. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1986;25:212–235. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R., Michel J., Roos M. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1984;1984:1343–1357. [Google Scholar]

- Peng P., Schmidt R. R. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:1171–1183. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Kumar V., Dere R. T., Schmidt R. R. Org. Lett. 2011;13:3612–3615. doi: 10.1021/ol201231v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Geng Y., Schmidt R. R. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012;354:1489–1499. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen M. M., Pedersen C. M. Chem. Rev. 2018;118:8285–8358. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt R. R., Stumpp M., Michel J. Tetrahedron Lett. 1982;23:405–408. [Google Scholar]

- Gould N. D., Liana Allen C., Nam B. C., Schepartz A., Miller S. Carbohydr. Res. 2013;382:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frihed T. G., Bols M., Pedersen C. M. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:4963–5013. doi: 10.1021/cr500434x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colinas P. A., Bravo R. D. Carbohydr. Res. 2007;342:2297–2302. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez O. M., Maresca A., Témpera C. A., Bravo R. D., Colinas P. A., Supuran C. T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:4447–4450. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavecchia M. J., Diez R. P., Colinas P. A. Carbohydr. Res. 2011;346:442–448. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ombouma J., Vullo D., Supuran C. T., Winum J.-Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014;22:6353–6359. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2014.09.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winum J.-Y., Colinas P. A., Supuran C. T. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:1419–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crespo R., de Bravo M. G., Colinas P. A., Bravo R. D. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:6469–6471. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xavier N. M., Porcheron A., Batista D., Jorda R., Řezníčková E., Kryštof V., Oliveira M. C. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:4667–4680. doi: 10.1039/c7ob00472a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G. S., Neuberger A. J. Chem. Soc. 1961:4872–4879. [Google Scholar]

- Garg H. G., Jeanloz R. W. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1985;43:135–201. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60068-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg H. G., Von Dem Bruch K., Kunz H. Adv. Carbohydr. Chem. Biochem. 1994;50:277–310. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2318(08)60153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava A., Varghese B., Loganathan D. Chem.–Eur. J. 2013;19:17720–17732. doi: 10.1002/chem.201302018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco L. L., Brandão M. C., Filho J. D. S., Alves R. J. Quim. Nova. 2015:1044–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Likhosherstov L. M., Novikova O. S., Derevitskaja V. A., Kochetkov N. K. Carbohydr. Res. 1986;146:C1–C5. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolaou K. C., Snyder S. A., Nalbandian A. Z., Longbottom D. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6234–6235. doi: 10.1021/ja049293c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colinas P. A., Bravo R. D. Org. Lett. 2003;5:4509–4511. doi: 10.1021/ol035838g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nardi M., Cano N. H., De Nino A., Di Gioia M. L., Maiuolo L., Oliverio M., Santiago A., Sorrentino D., Procopio A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:1721–1726. [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., William R., Liu X.-W. J. Org. Chem. 2013;78:1293–1299. doi: 10.1021/jo302619b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ombouma J., Vullo D., Dumy P., Supuran C. T., Winum J.-Y. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015;6:819–821. doi: 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y., Zheng J., Zhang Q. Org. Lett. 2018;20:3923–3927. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b01506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battina S. K., Kashyap S. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2015;34:133–144. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw G. A., Colgan A. C., Allen N. P., Pongener I., Boland M. B., Ortin Y., McGarrigle E. M. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:508–514. doi: 10.1039/c8sc02788a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthagar K., Polson M. I. J., Fairbanks A. J. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:6573–6579. doi: 10.1039/c5ob00851d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colinas P. A., Núñez N. A., Bravo R. D. J. Carbohydr. Chem. 2008;27:141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Griswold K. S., Horstmann T. E., Miller S. J. Synlett. 2003;2003:1923–1926. [Google Scholar]

- Krag J., Christiansen M. S., Petersen J. G., Jensen H. H. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:872–879. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marqvorsen M. H. S., Pedersen M. J., Rasmussen M. R., Kristensen S. K., Dahl-Lassen R., Jensen H. H. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:143–156. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuckendorff M., Jensen H. H. Carbohydr. Res. 2017;439:50–56. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyasse B., Grehn L., Ragnarsson U. Chem. Commun. 1997;11:1017–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Chang M.-Y., Wu M.-H., Chen Y.-L. Org. Lett. 2013;15:2822–2825. doi: 10.1021/ol401152w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi K., Kitayama R., Sato S. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984;5:303–305. [Google Scholar]

- Hiroi K., Makino K. Chem. Lett. 1986;15:617–620. [Google Scholar]

- Rencurosi A., Lay L., Russo G., Caneva E., Poletti L. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:7765–7768. doi: 10.1021/jo050704x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rencurosi A., Lay L., Russo G., Caneva E., Poletti L. Carbohydr. Res. 2006;341:903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochkov A. F. and Zaikov G. E., Chemistry of the O-Glycosidic Bond, Pergamon, 1979, pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkov A. F. and Zaikov G. E., Chemistry of the O-Glycosidic Bond, Pergamon, 1979, pp. 5–79. [Google Scholar]

- Capon B. Chem. Rev. 1969;69:407–498. [Google Scholar]

- Huang M., Garrett G. E., Birlirakis N., Bohé L., Pratt D. A., Crich D. Nat. Chem. 2012;4:663. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walvoort M. T. C., Dinkelaar J., van den Bos L. J., Lodder G., Overkleeft H. S., Codée J. D. C., van der Marel G. A. Carbohydr. Res. 2010;345:1252–1263. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2010.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M., Nakagawa A., Nishi N., Iijima K., Sawa R., Takahashi D., Toshima K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:3644–3651. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.