Abstract

Posterior dislocations are rare and diagnostically difficult injuries. Diagnosis is often delayed and this leads to a locked posteriorly dislocated humeral head.

Treatment options include conservative methods and surgical anatomic reconstruction options as well as non-anatomic surgical procedures such as subscapularis tendon transfer, hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty.

Decision-making for treatment as well as prognosis depend on the extent of the articular defect size of the humeral head, duration of the dislocation and patient-specific conditions such as age and activity levels.

Cite this article: EFORT Open Rev 2019;4:194-200. DOI: 10.1302/2058-5241.4.180043

Keywords: locked posterior shoulder dislocation, treatment options, clinical outcomes, shoulder instability, epidemiology, McLaughlin procedure

Introduction

The shoulder is the most frequently dislocated joint in the human body.1 There are three main types of dislocations regarding the direction of the humeral head displacement: anterior; inferior; and posterior. Anterior shoulder dislocation is the most common type while inferior dislocation is the rarest, making up to 95% and 1%, respectively. Posterior dislocations are rare and diagnostically difficult injuries. Diagnosis is often delayed because of subtle radiological findings and this results as a posteriorly locked humeral head. Due to the low number of the patients with locked posterior shoulder dislocations, there is not a large patient cohort and it is not possible to conclude an evidence-based treatment strategy from the literature. In this review article, posterior shoulder dislocation, its treatment options and its clinical results are discussed to determine the best available treatment strategy according to the pathology and injury mechanism.

Epidemiology and mechanism

Posterior dislocation of the shoulder is a rare injury. It accounts for up to 4% of all shoulder dislocations.2 The diagnosis of this injury is often missed on initial examination, despite highly suggestive injury circumstances, notable clinical signs and radiographic evidence.3 In up to 79% of cases, the diagnosis is made only once the injury has become chronic and the shoulder has been locked, which unfortunately has a negative effect on prognosis. McLaughlin described the resulting condition as a ‘diagnostic trap’ due to its occasional occurrence and possible neglection by unwary surgeons.4 As the duration of dislocation lengthens, patients suffer from chronic pain, stiffness, disability and decreased range of motion (ROM). Delayed diagnosis is caused by insufficient examination, misinterpreted radiological images and patient negligence.

Anterior trauma to an abducted and externally rotated shoulder is the most common mechanism for unilateral posterior dislocations.5 Seizures (epileptic, hypoglycaemic, drug-induced, etc.) or electric shocks can also cause unilateral or bilateral posterior dislocations due to unbalanced muscle contraction. The internal rotator muscles of the shoulder contract with greater force than the external rotators, which causes the humeral head to move superiorly and posteriorly.

Physical examination

Severe oedema after the injury hinders the diagnosis so the clinical examination must be done carefully. Cooper first reported the signs of posterior shoulder dislocation as the appearance of posterior fullness on the affected side.6 As a result of this, the anterior aspect of the shoulder seems to be flattened. The patient suffers from pain at both the anterior and the posterior aspects of the shoulder region with limited ROM, especially in abduction and external rotation. The locking of the shoulder in an internally rotated position generates pain, especially in flexion, adduction and internal rotation. If there is mild pain during external rotation, this situation may indicate a chronic dislocation. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder gives only a few evident symptoms and the clinical picture may resemble other shoulder pathologies such as frozen shoulder, shoulder sprain or rotator cuff tear. The physician has to be suspicious about special circumstances such as severe trauma, electric shock and epileptic seizures. If the patient has such a history, physical examination and radiological evaluation should be done carefully and properly.

Imaging

In anterior shoulder dislocation, humeral head dislocates antero-inferiorly and consequently glenoid seems to be empty on anteroposterior (AP) shoulder view. However, the humeral head dislocates posteriorly without inferior translation in posterior dislocations and this results in an overlapped view of the head in relationship to the glenoid and misleads the clinician. An internally rotated humeral head gives a rounded appearance on AP views, which is called the lightbulb sign. The rim sign is defined as the space between the anterior glenoid rim and the humeral head being > 6 mm in AP shoulder views, indicating a widened glenohumeral space.7 In case of a suspicion about posterior dislocation of the shoulder without the aforementioned radiological signs, additional radiographs such as axillary view or scapular Y view are necessary. Although the axillary view is the best one to demonstrate a posterior dislocation, it is sometimes difficult to obtain routine axillary views in acute cases because of severe pain.

In a systematic review by Xu et al, the initial diagnosis of posterior shoulder dislocations was missed in 150 (73.2%) of 205 shoulders. In this review of 53 articles, the average age was 47.6 years and 18% of cases were affected bilaterally. The cause of dislocation was trauma in 121 (59%), seizure in 82 (40%) and electric shock in two (1%). The average time delay between injury and diagnosis was 5.88 months (0 to 300). Almost all patients with neglected dislocation had AP radiographs (147 patients, 98%) but none of them had axillary view or CT scan. Among 166 cases with an AP view alone, only 19 patients (11.4%) were diagnosed initially. The diagnosis rate using AP views of 11.4% increased to 100% when axillary views or CT scans were added.8

While providing important assistance in establishing the diagnosis (especially in seizure-related and bilateral dislocations), CT scans also help the physicians to analyse the location and the percentage of bone loss in both the humeral head and glenoid in addition to the associated fractures. These factors help determining the treatment strategies for each patient. Reverse Hill Sachs lesion, posterior glenoid rim fracture, lesser tuberosity fracture and anatomical humeral neck fracture are associated injuries easily recognized by CT scan. MRI is a useful tool to reveal the soft-tissue damage such as rotator cuff and labral tears along with its help to establish the diagnosis and analyse the bone defects. Posterior or reverse Bankart lesion and posterior labrocapsular periosteal sleeve avulsion (POLPSA lesion) are associated injuries, which are easily recognized by MRI.

Treatment

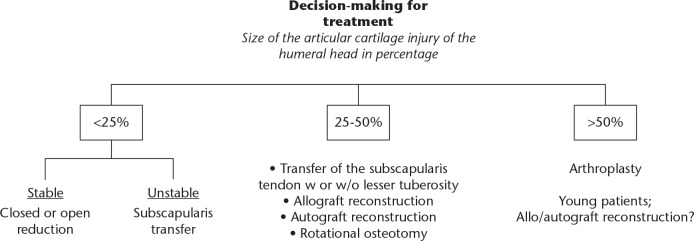

Once the diagnosis has been made, additional possible lesions must be detected as soon as possible in order to determine the right treatment strategy. According to the factors such as age, percentage of bone loss (Fig. 1), time to diagnosis and accompanying lesions, a treatment strategy is chosen which varies from non-operative options to total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) (Table 1). Goga et al reported that if the surgeons did not treat the chronic shoulder dislocations, it would lead to much worse outcomes than surgical treatment in terms of pain, ROM and function.9 The surgical treatment options are explained below.

Fig. 1.

Decision-making for the treatment of locked posterior shoulder dislocations.

Table 1.

List of treatment options for posterior shoulder dislocations

| Treatment |

|---|

|

Conservative

Closed reduction Supervised neglect Operative Open reduction Transfer of the subscapularis tendon with or without lesser tuberosity McLaughlin method (transfer of the subscapularis tendon) Hughes and Neer method (osteotomy of the lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis) Reconstruction with autograft Reconstruction with allograft Rotational osteotomy of the humerus Arthroplasty |

Acute reduction and immobilization

As an initial treatment, for all acute posterior dislocations, acute reduction and immobilization should be attempted. Most dislocations have a chance to reduce with closed manipulation, if the injury is < 6 weeks old. The prognosis is good if the reverse Hill Sachs lesion is < 25% of the humeral head articular surface.

Closed reduction should be attempted under general anaesthesia.10 The reduction manoeuvres must be done gently and carefully. In order to reduce the humeral head into the glenoid fossa, forward pressure on the humeral head must be applied with the arm in the flexed, adducted and internally rotated position. The physician needs an assistant who will perform cross-body traction to the arm when the digital pressure is placed on the posterior of the humeral head. The relocation is marked by the ability to rotate the shoulder externally.11 The reduction attempts should be done under an image intensifier to confirm the reduction and its stability.

After the closed reduction, immobilization is required with 10° of abduction and neutral rotation. If there is a risk of instability, the arm can be positioned in 20° of external rotation.12 For six weeks, the arm must be kept in a gunslinger splint. During this period, the patient performs gripping and gentle elbow stretching exercises. After six weeks, the splint is removed; physical therapy including rotator cuff strengthening and periscapular stabilization exercises are initiated. The activities placing the arm in high-risk positions (especially hyper internal rotation) are prohibited until 12 weeks.

Open reduction and surgical stabilization

Open reduction is indicated in dislocations in which closed reduction cannot be achieved. Reverse Hill Sachs lesions > 25% of the humeral head articular surface in size are often unstable after closed reduction and they also require surgical intervention. Open reduction and surgical stabilization are indicated in such cases with defects 25% to 45% of the humeral head articular surface. The deltopectoral approach is used to reconstruct the humeral head bony defect by the transfer of the subscapularis tendon with transosseous sutures described by McLaughlin13 or by suture anchors described by Spencer and Brems.14 The posterior subdeltoid approach can also be used and this approach lets the surgeon to fill the defect with autograft and perform a Bankart type capsulorrhaphy.15 If the injury is < 3 weeks old, disimpaction and bone grafting of the defect can be performed. For any glenoid bone loss, an iliac crest bone graft can be used as a block and both approaches can be preferred.16

McLaughlin procedure

McLaughlin described a method to use in posterior dislocations with moderate humeral head defects (from 25% to 45% of the humeral head articular surface) by tenotomizing subscapularis tendon and burying it into the defective area.17 Hawkins et al reported that if the period of delay is > 6 months, the articular cartilage of humeral head gets non-viable; therefore, the McLaughlin procedure should not be preferred.3 Several authors modified this method and described osteotomizing the lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis tendon and fixing it to the defective area.18,19 The modified McLaughlin method provides additional bony support for the defective area and is preferred for patients when the injury is older than three weeks.20

The surgery is performed in a beach chair position. The deltopectoral approach is used. First, the biceps tendon is identified as a landmark for the bicipital groove. The lower edge of the subscapularis tendon is detected in order to mark lesser tuberosity. Osteotomy of the lesser tuberosity is performed from lateral to medial, starting from the bicipital groove to the defect of the humeral head.20 The lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis tendon is elevated in order to demonstrate the head and the glenoid. Reduction is performed with the help of an elevator. If the reduction cannot be managed by an elevator, a lamina spreader device can be used to accomplish reduction of the joint. When reduction is achieved, the lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis tendon is fixed into the humeral head defect using two or more transosseous non-absorbable sutures. There are many minor modifications of this technique by different authors in the literature.

Khira and Salama published successful results of their modified technique on 12 patients who were followed up for 30 months. They used autograft in the defective area and performed modified McLaughlin procedure simultaneously for defects 20% to 45% claiming lesser tuberosity itself was not large enough to fill the defect.21 Shams et al operated 11 patients with defects of 25% to 50% with a modified McLaughlin technique by fixing the tuberosity with non-absorbable sutures instead of screws and obtained good to excellent results in most of the patients who were followed up for 29 months.22 Banerjee et al used the modified McLaughlin procedure in seven male patients with acute trauma (within three weeks of injury), who were followed up for 41 months and obtained excellent results.23 Kokkalis et al used morselized bone allograft (fresh-frozen femoral head bone allograft) in the defective area and then transferred the lesser tuberosity with the attached subscapularis tendon and secured it with absorbable suture anchors. Five male patients underwent surgery; the mean follow-up time was 20 months and clinical results were excellent.24

Allograft reconstruction

Bone grafting is an unavoidable procedure in insufficient bone reserve to reconstruct the anatomical sphericity and preserve the stability of the reconstructed humeral head after locked posterior shoulder dislocations. Allo- and autografting are both described in the literature. Some authors advocated the use of allografts in obtaining the anatomical sphericity of humeral head rather than preferring non-anatomical techniques by using osteochondral allografts from fresh-frozen femoral heads. Especially in the case of larger defects of up to 50% and young patients with viable humeral bone reserve, fixation of the allografts in defective areas with partially threaded cancellous screws yielded excellent results.25,26

Martinez et al treated six patients who had segmental defects (involving 40% of the articular surface) with a frozen allogeneic segment of humeral head. They followed up the patients for a mean of ten years and concluded that allograft reconstruction has a good long-term follow-up in 50% of the cases. They suggested that an arthroscopic technique could be developed in the future.27 Gerber et al operated on 22 shoulders that had segmental defects (involving 30% to 55% of the articular surface) with a segmental reconstruction using either a fresh-frozen femoral or humeral allograft segment (in 17 patients) or a structural iliac autograft (in five patients). At a mean follow-up of 10.7 years, the clinical results of the patients were as good as the results reported for alternative treatment methods with only half of their follow-up duration. The ultimate failure rate was found to be 13%.28

Autograft reconstruction

In case of bilateral posterior humeral head dislocations, harvesting osteochondral autograft from the side that will undergo hemiarthroplasty and using this graft on the contralateral side is also described in the literature by several authors.29,30 Even in one-sided posterior dislocations, osteochondral autograft might become of use in case of posteroinferior only glenoid defects in patients with arthroplasty indication. The autograft bone material from the humeral head can be used to reconstruct the glenoid and hemiarthroplasty can be applied instead of TSA.31 Besides these procedures, autografts from the iliac crest are also used in conjunction with other techniques such as the McLaughlin procedure and derotational osteotomies.

Osteotomy

Derotational osteotomy of the humerus was suggested as a procedure for younger patients with significant humeral head depression.32,33 Less favourable results of arthoplasty in younger patients compared with older patients have also made osteotomy a valuable option for these groups of patients.34 Keppler et al defined the usage of this rotational osteotomy in locked posterior shoulder dislocations. They operated on ten patients with an average age of 53 years. They concluded that rotational osteotomy is an effective procedure at restoring glenohumeral congruity and early functional activity in patients with locked posterior shoulder dislocation, if the following criteria are all met: a healthy articular cartilage; a humeral head defect involving < 40% of the articular surface; and a patient who is able to participate in an active rehabilitation programme.32 Ziran and Nourbakhsh defined the proximal derotational humeral osteotomy for internal rotation instability of the shoulder after locked posterior dislocations. They reported the outcomes of four patients with a mean age of 40 years and a mean follow-up of 22 months. They concluded that this technique can be a viable option for younger age groups since it can facilitate rehabilitation by providing immediate stability.33

Arthroplasty

Arthroplasty is a viable option in patients with a large humeral head defects and less bone reserve after locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. If the defect is larger than 45% to 50% of the articular surface and if the glenoid cavity is intact in a chronic dislocation aged > 6 months, hemiarthroplasty is recommended.35,36 When concomitant glenoid damage or significant glenoid arthritis is present, TSA should be preferred.37,38 Wooten et al operated 32 patients for locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder with an anatomic shoulder arthroplasty. They operated on 18 patients with a hemiarthroplasty and on 14 with a TSA. All patients were followed up for a mean of 8.2 years. They concluded an inferior overall satisfaction rate in their patients compared with the patients who underwent anatomic arthroplasty due to glenohumeral osteoarthritis, although their treatment provided pain relief, improved shoulder external rotation and a low rate of recurrent instability.39 Cheng et al operated on seven shoulders of five patients with a TSA. Average patient age was 58 years and the average follow-up time was 27 months. They concluded that TSA in patients with extensive damage to the articular surfaces of glenoid and humerus reliably decreases the patients’ level of pain and improves their ROM and level of function.40 Sperling et al operated on 12 patients with a mean follow-up of five years. They operated on six patients with hemiarthroplasty and six with TSA. They noted significant pain relief as well as improvement in external rotation and concluded that shoulder arthroplasty for locked posterior dislocation is associated with satisfactory pain relief and improvement in motion.41

The aforementioned studies are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of studies evaluating posterior shoulder dislocations

| Author and journal | Study design | Defect of the humeral head (%) | Method | Patients (n) | Mean age (years) | Time to intervention | Mean time interval between injury and diagnosis | Mean follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TT Duralde and Fogle11 |

Retrospective | 18 to 32 | Closed reduction and conservative therapy | 7 | 52 | Acute (within 2 weeks) | 4 days | 46 months | ASES: 93 |

| Khira and Salama21 | Prospective case study | 40 (30 to 45) | Modified McLaughlin with iliac autograft | 12 | 26 | ND | 8 weeks | 30 months | UCLA: 30 |

| Shams et al22 | Prospective case study | 35 (30 to 40) | Modified McLaughlin | 11 | 39 | 9 weeks | ND | 29 months | UCLA: 30 |

| Banerjee et al23 | Retrospective | 32 (25 to 45) | Modified McLaughlin | 7 | 39 | 14 days | 0 days | 41 months | Constant: 92, ASES: 98 |

| Kokkalis et al24 | Retrospective | 38 (30 to 45) | Modified McLaughlin with morselized bone allograft | 5 (6 shoulders) | 53 | 8 weeks | ND | 20 months | Constant: 84 |

| Diklic et al25 | Retrospective | 25 to 50 | Allograft reconstruction | 13 | 42 | ND | 4 months | 54 months | Constant: 86.8 |

| Martinez et al27 | Retrospective | 40 | Allograft reconstruction | 6 | 32 | 7 to 8 weeks | ND | 10 years | Constant: 69 |

| Gerber et al28 | Prospective case study | 43 | Allograft (in 17 patients) or autograft (in 5 patients) reconstruction | 19 | 44 | 4 cases in 7 days, 5 cases between 1 week and 1 month, 13 cases with a mean of 6.3 months | ND | 128 months | Constant: 77 |

| Keppler et al32 | Retrospective | 20 to 40 | Rotational osteotomy | 10 | 53 | ND | 155 days | 20 months | Rowe and Zarins: excellent in 2, good in 5 |

| Ziran and Nourbakhsh33 | Retrospective | ‘Significant depression’ | Rotational osteotomy | 4 | 40 | ND | 10 days | 22 months | No functional analysis |

| Wooten et al39 | Retrospective | > 45 | Hemiarthroplasty in 18 patients, TSA in 14 patients | 32 | 54 | 24 months | ND | 8.2 years | 3 excellent (13%), 15 satisfactory (65%), and 5 unsatisfactory (22%) |

| Cheng et al40 | Prospective case study | Extensive | TSA | 7 | 58 | 23 months | ND | 27 months | ASES: 55.6 |

| Sperling et al41 | Prospective case study | ND | Hemiarthroplasty in 6 patients, TSA in 6 patients | 12 | 56 | 26 months | ND | 108 months | Neer result rating system: 1 excellent, 6 satisfactory, and 5 unsatisfactory |

The modified McLaughlin method is the transfer of the subscapularis tendon with the attached lesser tuberosity.

ASES, The American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons Shoulder Score; ND, no data; UCLA, University of California at Los Angeles Score; Constant, Constant-Murley Shoulder Outcome Score.

Prognosis and complications

The functional outcomes depend mainly on the duration of the dislocation and the extent of the articular injury. Prognosis worsens as the duration of the dislocation lengthens as well as the extent of the articular injury increases.42

Patients with recalcitrant epileptic seizures are more prone to re-dislocations. A careful bone reconstruction is advised to diminish recurrence rates. When reconstruction is not possible, arthroplasty procedures can be considered but the clinical outcomes are not well-known since the number of studies and patients are few. Both hemiarthroplasty and anatomical, reverse or constrained TSAs are among the treatment options. Anatomical TSA is recommended over hemiarthroplasty due to a more concentric glenoid.43 Glenohumeral arthrodesis can also be considered.

Complications are specific to patient subsets. Chronic shoulder pain, recurrent instability, allograft collapse, avascular necrosis, non-union, stiffness and omarthrosis can be seen.20,41

Conclusions

Posterior dislocations are rare and diagnostically difficult injuries. Diagnosis is often delayed and this results as a locked posteriorly dislocated humeral head. The patient suffers from pain both at the anterior and posterior aspects of the shoulder region with limited ROM, especially in abduction and external rotation. The posterior fullness on the affected side can be detected on physical examination. An internally rotated humeral head gives a rounded appearance on AP views, which is called the lightbulb sign. In case of a suspicion about posterior dislocation of the shoulder, additional radiographs such as axillary view or scapular Y view are necessary. CT and MRI are also helpful to establish the diagnosis. Decision-making for treatment as well as prognosis depends on the extent of the articular defect size of the humeral head, duration of the dislocation and patient-specific conditions such as age and activity levels. Treatment options include conservative methods and surgical anatomic reconstruction options as well as non-anatomic surgical procedures such as subscapularis tendon transfer, hemiarthroplasty and TSA. Reverse Hill Sachs lesions > 25% of the humeral head articular surface in size are often unstable after closed reduction and also require surgical intervention. Open reduction and surgical stabilization are indicated in such cases with defects 25% to 45% of the humeral head articular surface. The humeral head bony defect can be reconstructed by the transfer of the subscapularis tendon with or without lesser tuberosity. Allo-/autograft reconstruction is valuable, especially in case of larger defects up to 50% and in young patients with viable humeral bone reserve. Derotational osteotomy of the humerus is also suggested for younger patients with significant humeral head depression. Arthroplasty is a viable option in patients with a large humeral head defects and less bone reserve after locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder.

Footnotes

ICMJE Conflict of interest statement: The author declares no conflict of interest relevant to this work.

Funding statement

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article.

References

- 1. Robinson CM, Dobson RJ. Anterior instability of the shoulder after trauma. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2004;86-B(4):469–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rowe CR, Zarins B. Chronic unreduced dislocations of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1982;64-A(4):494–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hawkins RJ, Neer CS, II, Pianta RM, Mendoza FX. Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1987;69-A(1):9–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McLaughlin HL. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1952;24-A(3):584–590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Robinson CM, Seah M, Akhtar MA. The epidemiology, risk of recurrence, and functional outcome after an acute traumatic posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2011;93(17):1605–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cooper A. On the dislocations of the os humeri upon the dorsum scapulae, and upon fractures near the shoulder joint. Guys Hosp Rep 1839;4:265–284. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cicak N. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2004;86-B(3):324–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xu W, Huang L-X, Guo JJ, et al. Neglected posterior dislocation of the shoulder: A systematic literature review. J Orthop Translat 2015;3(2):89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goga IE. Chronic shoulder dislocations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003;12(5):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walch G, Boileau P, Martin B, Dejour H. Unreduced posterior luxations and fractures-luxations of the shoulder. Apropos of 30 cases. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1990;76(8):546–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duralde XA, Fogle EF. The success of closed reduction in acute locked posterior fracture-dislocations of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15(6):701–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dimon JH., III Posterior dislocation and posterior fracture dislocation of the shoulder: a report of 25 cases. South Med J 1967;60(6):661–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McLaughlin HL. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder (follow-up note). J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1962;44-A:1477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spencer EE, Jr, Brems JJ. A simple technique for management of locked posterior shoulder dislocations: report of two cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005;14(6):650–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dubousset J. Posterior dislocations of the shoulder. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1967;53(1):65–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Augereau B, Leyder P, Apoil A. Treatment of inveterate posterior shoulder dislocation by the double approach and retroglenoid bone support. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 1983;69(Suppl. 2):89–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. McLaughlin HL. Locked posterior subluxation of the shoulder: diagnosis and treatment. Surg Clin North Am 1963;43:1621–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spencer EE, Jr, Brems JJ. A simple technique for management of locked posterior shoulder dislocations: report of two cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005;14(6):650–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Delcogliano A, Caporaso A, Chiossi S, et al. Surgical management of chronic, unreduced posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2005;13(2):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Castagna A, Delle Rose G, Borroni M, et al. Modified MacLaughlin procedure in the treatment of neglected posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Chir Organi Mov 2009;93(1):1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khira YM, Salama AM. Treatment of locked posterior shoulder dislocation with bone defect. Orthopedics 2017;40(3):e501–e505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shams A, El-Sayed M, Gamal O, ElSawy M, Azzam W. Modified technique for reconstructing reverse Hill-Sachs lesion in locked chronic posterior shoulder dislocation. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2016;26(8):843–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Banerjee M, Balke M, Bouillon B, et al. Excellent results of lesser tuberosity transfer in acute locked posterior shoulder dislocation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21(12):2884–2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kokkalis ZT, Mavrogenis AF, Ballas EG, Papanastasiou J, Papagelopoulos PJ. Modified McLaughlin technique for neglected locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Orthopedics 2013;36(7):e912–e916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diklic ID, Ganic ZD, Blagojevic ZD, Nho SJ, Romeo AA. Treatment of locked chronic posterior dislocation of the shoulder by reconstruction of the defect in the humeral head with an allograft. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2010;92(1):71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gerber C, Lambert SM. Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1996;78(3):376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Martinez AA, Navarro E, Iglesias D, et al. Long-term follow-up of allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Injury 2013;44(4):488–491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gerber C, Catanzaro S, Jundt-Ecker M, Farshad M. Long-term outcome of segmental reconstruction of the humeral head for the treatment of locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23(11):1682–1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ivkovic A, Boric I, Cicak N. One-stage operation for locked bilateral posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2007;89-B(6):825–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Torrens C, Santana F, Melendo E, Marlet V, Caceres E. Osteochondral autograft and hemiarthroplasty for bilateral locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2012;41(8):362–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Riggenbach MD, Najarian RG, Bishop JY. Recurrent, locked posterior glenohumeral dislocation requiring hemiarthroplasty and posterior bone block with humeral head autograft. Orthopedics 2012;35(2):e277–e282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keppler P, Holz U, Thielemann FW, Meinig R. Locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder: treatment using rotational osteotomy of the humerus. J Orthop Trauma 1994;8(4):286–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ziran B, Nourbakhsh A. Proximal humerus derotational osteotomy for internal rotation instability after locked posterior shoulder dislocation: early experience in four patients. Patient Saf Surg 2015;9:15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schoch B, Schleck C, Cofield RH, Sperling JW. Shoulder arthroplasty in patients younger than 50 years: minimum 20-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015;24(5):705–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Page AE, Meinhard BP, Schulz E, Toledano B. Bilateral posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulders: management by bilateral shoulder hemiarthroplasties. J Orthop Trauma 1995;9(6):526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hawkins RJ. Unrecognised dislocations of the shoulder. Inst Course Lect 1985;34:258–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Checchia SL, Santos PD, Miyazaki AN. Surgical treatment of acute and chronic posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1998;7(1):53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Pritchett JW, Clark JM. Prosthetic replacement for chronic unreduced dislocations of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987;(216):89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wooten C, Klika B, Schleck CD, et al. Anatomic shoulder arthroplasty as treatment for locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2014;96-A(3):e19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng SL, Mackay MB, Richards RR. Treatment of locked posterior fracture-dislocations of the shoulder by total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997;6(1):11–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sperling JW, Pring M, Antuna SA, Cofield RH. Shoulder arthroplasty for locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004;13(5):522–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schliemann B, Muder D, Gessmann J, Schildhauer TA, Seybold D. Locked posterior shoulder dislocation: treatment options and clinical outcomes. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011;131(8):1127–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Thangarajah T, Falworth M, Lambert SM. Anatomical shoulder arthroplasty in epileptic patients with instability arthropathy and persistent seizures. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017;25(2):2309499017717198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]