Abstract

Head and neck cancer is the sixth most common cancer with over 500000 annually reported incident cases worldwide. Besides major risk factors tobacco and alcohol, oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC) show increased association with human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV-associated and HPV-negative OSCC are 2 different entities regarding biological characteristics, therapeutic response, and patient prognosis. In HPV OSCC, viral oncoprotein activity, as well as genetic (mutations and chromosomal aberrations) and epigenetic alterations plays a key role during carcinogenesis. Based on improved treatment response, the introduction of therapy de-intensification and targeted therapy is discussed for patients with HPV OSCC. A promising targeted therapy concept is immunotherapy. The use of checkpoint inhibitors (e.g. anti-PD1) is currently investigated. By means of liquid biopsies, biomarkers such as viral DNA or tumor mutations in the will soon be available for disease monitoring, as well as detection of treatment failure. By now, primary prophylaxis of HPV OSCC can be achieved by vaccination of girls and boys.

Key words: Head and neck cancer, Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, Carcinogenesis, Human Papillomavirus, Immunotherapy

1. Introduction and Summary

Oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the only head and neck tumor entity with clearly increasing incidence. Infections with oncogenic high-risk (HR) human papillomaviruses (HPV) are responsible for this development as they are increasingly found in OSCC. The transmission pathways and persistence of HPV in the oropharynx are still unknown. However, there are numerous hints that the transmission of HR HPV occurs through sexual contact. The carcinogenesis of HPV-positive OSCC (HPV OSCC) is mainly promoted by viral oncoproteins. However, genetic modifications also play a key role and often additional risk factors of classic carcinogenesis are observed (tobacco). Up to now, genetic examinations do not show a clear picture of HPV OSCC-specific mutations. Investigations of epigenetic modifications (DNA methylation, microRNA, tumor metabolism, immune escape, gene expression) identified HPV-specific aberrations that reveal approaches to future targeted therapies. Patients with HPV OSCC are often rather young, relatively healthy, and have accumulated less lifestyle risks; in comparison to HPV-negative OSCC, the overall survival (OS) of those patients is significantly better. The better OS and less additional risk factors make these patients suitable to benefit from de-intensification of the treatment or targeted therapy options. Since January 2017, revised TNM classifications and staging are applied for HPV OSCC. As test procedure, the p16INK4a (p16) test is suggested internationally. However, testing of HPV OSCC should be performed by means of dual detection of HPV DNA and p16 expression if possible. HPV OSCC will then, in contrast to former times, be classified into lower UICC stage groups. After therapy, patients with HPV OSCC have about 30% better 5-year OS rates in all therapeutic modalities. HPV is no predictor for surgery or radiotherapy (RT) so that surgical tumor resection still has a high significance. Currently, numerous studies are conducted with less intensive therapy; however, up to now results have not been published. Other trials focus on the significance of new immunotherapies for HPV OSCC. Surgical therapy options for distant metastasis are noteworthy; there are still possibilities of curative therapy in cases of distant failure. Beside the assessment of functional impairment, this is relevant for the follow-up of our patients. In the future, it is very probable that specific as well as de-intensified therapies are available for patients with HPV OSCC. Regarding the assignment to specific therapies, risk models are currently developed and discussed. Possibly, the viral carcinogenesis provides a valuable option for molecular early detection and follow-up by means of blood samples (so-called liquid biopsy). Finally, ENT-specialists should promote HPV vaccination for girls and boys because probably nearly all cases of HPV OSCC might hereby be avoided.

2. Epidemiology

2.1 Update on increased incidence of oropharyngeal cancer

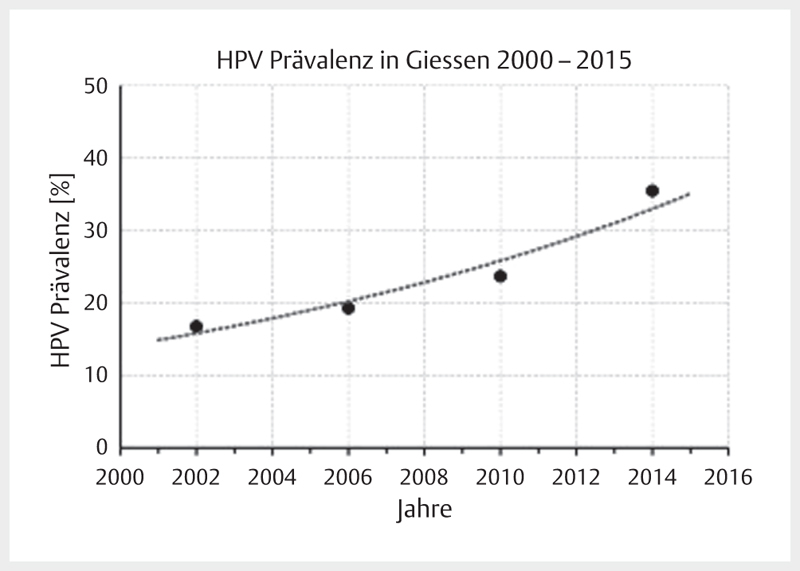

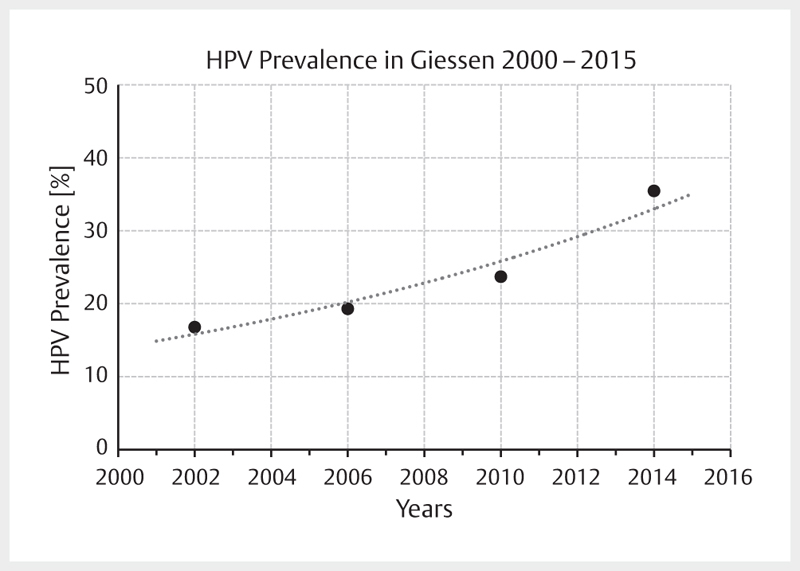

Increasing incidence rates are described for HPV-associated head and neck tumors whereas the incidence of all other head and neck carcinomas decreases in developed countries. A comparative analysis of data of US American registries from 1973–2012 and 2000–2012 revealed a doubling for OSCC (frequently HPV-associated) with simultaneous decrease of the incidence for cancer of the oral cavity (rarely HPV-associated) 1 . Canadian registries currently also report a decrease of the general incidence of head and neck cancer with simultaneous increase of OSCC 2 . This epidemiological trend is explained by the increasing prevalence of oncogenic HPV in OSCC, based on nearly all published original papers 3 . Depending on the study design and detection procedures, the prevalence of oncogenic HPV in OSCC reaches up to 85% in recently published series from Scandinavia 4 . It may at least be assumed that the increased prevalence described is already overestimated because of methodical flaws. With regard to the design, for example older specimens were compared with newer ones, this might explain a systematic incorrectness. In German-speaking countries, a HPV prevalence for OSCC is currently assumed with 20–40% 5 6 7 . For tonsillar carcinomas, oncogenic HPV was detected in more than 50% of the cases already 15 years ago 8 , here the percentage of HPV-associated OSCC can be expected to be much higher. A comparative investigation of 599 patients of our own patient population ( Fig. 1 ) with OSCC showed an increase of the HPV prevalence of about 20% of the early patients to currently over 50% 7 . A comparative analysis of the HPV prevalence in cervical CUP syndrome could reveal a clear increase of currently nearly 75% HPV-positivity rate at our department. In summary, the published data show a continuous increase of OSCC incidence rates and correspondingly, the increased incidence rates are due to the HPV epidemic.

Fig. 1.

Prevalence of oncogenic HPV in OSCC patients who were treated in Giessen is increasing. Currently the prevalence amounts to more than 50%. The data points represent the mean value of 4 years each.

2.2 Significance of HPV detection outside the oropharynx

From a health economic point of view, the percentage of HPV-associated head and neck tumors in other anatomical locations than the oropharynx is of high interest, too. For example, those cases might be avoided by HPV vaccination. Furthermore, patients could also benefit from de-intensified therapy and reduced side effects. The first question that is relevant in this context is, if the detection of HPV in tissues outside the oropharynx reveals true HPV-associated carcinogenesis or if it is an incidentally detected infection without further relevance. The second question in this context is, if the detection of HPV in non-OSCC is associated with an improved prognosis of the patients.

A recent US American publication from 2015 could reveal a high rate of HPV-positive DNA test results (70.1% in the oropharynx, 32.0% in the oral cavity, and 20.9% in the larynx) also outside the oropharynx 9 . However, considering all publications and meta-analyses on HPV positivity outside the oropharynx, the results are inconsistent 10 11 12 . A data set of a meta-analysis of 12,263 patients showed HPV association in the oral cavity (24.2%) and the larynx (22.1%) based on DNA test. Outside the oropharynx, however, very few data sets with dual test results (HPV DNA and p16 test) are published 13 . Currently, an extensive investigation from Spain was presented with results from 3,680 patients with head and neck tumors after combined testing for DNA, RNA, and p16. Hereby, the HPV prevalence for oral cavity cancer amounted to 4.4% and for laryngeal cancer to 3.5%; in cases of positivity of all 3 tests, the results were even much lower. This relativizes significantly the mentioned, sometimes very high rates of HPV-associated head and neck tumors outside the oropharynx 14 . A high percentage of positive HPV test results outside the oropharynx probably does not show HPV-associated carcinogenesis but acute infections or false-positive test results.

Prospective investigations on the relevance of HPV detection outside the oropharynx with regard to prognosis of the patients are not available. However, based on retrospective data of patients who underwent radiotherapy (RT) or combined radiochemotherapy (RCT) in the context of clinical studies, it can be assumed that a positive p16 test outside the oropharynx has low prognostic significance. The DAHANCA consortium in Denmark treated 1,294 patients with advanced head and neck cancer by means of RT or RCT; and in head and neck cancer outside the oropharynx no prognostic significance could be elaborated 15 . In addition, p16 positive non-OSCC patients were evaluated after treatment in 3 RTOG studies. In comparison to p16 positive OSCC patients, non-OSCC patients had a mortality risk increase of 50% 16 . For patients with laryngeal cancer and positive p16 test, even poorer survival rates have been published 17 . Serological examinations also contradict to a correlation between the risk of head and neck tumor disease (apart from oropharynx) and HR HPV infection. In an analysis of HPV 16 specific antibodies, the odds ratios for the risk to develop OSCC amounted to 14.6 compared to 3.6 (oral cavity) and 2.4 (larynx) 18 . A more recent investigation (ARCAGE study) evaluated 1,496 head and neck cancer patients. Positivity for HPV16 L1 and E6 antibodies increased the risk for the development of OSCC by factor 8.6 and 132.0, respectively. In contrast, marginal values of 1.54 and 4.18, respectively, were described for laryngeal cancer 19 .

In summary, the prevalence of HPV-induced tumors outside the oropharynx is clearly lower than assumed and roughly estimated to be less than 5%. There is no reliable evidence that the prognosis of those patients is better in comparison to OSCC patients.

2.3 Epidemiology of carcinogenic HPV infections

Since nearly all adults in Germany have contact to oncogenic HPV during adolescence, it is important to understand why HPV OSCC increases during the last decades and develops mainly in male patients. The most common manifestation of HPV infection are warts and genital condylomas. In more than 90% of cases, these diseases are caused by non-oncogenic HPV types 6 and 11. The infection can already be transmitted at birth and presents to ENT specialists in particular as respiratory papillomatosis. True neoplastic lesions of the cervix are sometimes caused by type 6 and type 11, too. However, in the majority cervical lesions typical oncogenic HPV types 16, 18, 31, and 45 are found.

Regarding the prevalence of oral infection with HPV in the general population, cross-sectional studies are available, but only few data are published on the temporal dynamics. A review of 18 trials with 4,581 healthy adults described an estimated incidence of oral HR HPV infection with 1.3% 20 . The age distribution of oral HPV infection shows a bimodal distribution. The first peak could be found between 30 and 34 years of age and the second peak between 60 and 64 years. The infection occurred significantly more frequently in males 21 . Generally, the data situation is not evident because in another investigation, females had genital oncogenic HPV infections with the same frequency than males 22 , only the duration to “clearance” was (slightly) different to the disadvantage of the men. Incidence and type of sexual contact (oral sex, deep kisses, promiscuity) as well as age at first sexual intercourse, marihuana consumption, cigarette consumption, and genital HPV infections could be identified as risk factors 23 . The average duration of an oral HPV infection was assessed in 1,626 male persons and amounted to about 7 months; the follow-up, however, was only 13 months 24 . The majority of oral HPV infections heal within several months without further consequences. Reinfections occur only rarely. It is worth mentioning that even partners of HPV OSCC patients only have an infection rate slightly above 1% 25 . In addition, immunodeficiency (HIV infection), cigarette consumption, and high age are reported as risk factors for persisting oral HPV infection 26 . For better understanding the increased incidence of oral HPV infections in males, other data describe a higher number of sexual partners, younger age at the first sexual contact, and numerous oral sexual contacts 27 . Another hint to the susceptibility of males for HPV type 16 (HPV16)-caused OSCC is that genital HPV infections in men are mainly due to HPV 16 and not type 18 28 .

Reliable data why mostly men develop HPV 16-induced OSCC are not available, but numerous hints are found for an accumulation of risks (kinetics of the infection, nicotine, sexual risks, see chapter 4). Overall, this may explain why currently an estimated percentage of 75% of the patients with HPV OSCC are male. In contrast to the data for an increased incidence of OSCC, no data are available that confirm an increase of oral HR HPV infections.

2.4 Development in regions with consequent primary prophylaxis

Primary prophylaxis against carcinogenic HPV is available as HPV vaccination. The Sanofi Pasteur MSD Company produced the quadrivalent vaccine Gardasil that was approved in the USA and Europe in 2006. One year later, the bivalent vaccine Cervarix was approved. Both vaccines contain the recombinant capsid protein L1 of the HPV types 16 and 18, and 6, 11, and 18, respectively. Since April 2016, the 9-valent vaccine Gardasil 9 is available and additionally protects against the HR HPV strains 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58. The advantages are an extended protection given by vaccination and a 2 dose scheme (in intervals of 5-13 months). The HPV vaccines are approved as of the age of 9 years and vaccination should be performed before the first sexual contact. The approval applies for girls and boys, however, currently the German Standing Committee on Immunization (Ständige Impfkommission, STIKO) currently recommends only vaccination of girls, which is also paid by the health insurers.

In Germany, the HPV vaccine is currently not widely administered. According to an analysis of health insurance data of the AOK of Baden-Württemberg, only 37% of young women born in 1996 had complete protection provided by vaccination. In comparison, the vaccination rate against mumps and rubella is about 92% according to the Robert Koch Institute. Comparable data with vaccination rates of <40% in girls were published by the ministry of health in 2014 29 . The data clearly indicate vaccination of boys. However, the registration trials was naturally conducted based on precancerous lesions of the cervix and accordingly, the cost-benefit analyses refer to the diseases of the uterine cervix 30 .

In 2015, 34% of the countries worldwide had a HPV immunization program. However, population-related only less than 5% of all nations (in countries with high incidences often no program was established) benefited from vaccination in this time. From countries with a high coverage, numerous data are available that report an effect on HPV-associated diseases even apart from cervix cancer. For example, a review of the literature from 2015 could reveal that HR HPV infections were reduced by 68% and anogenital warts decreased by 60%, in countries with an immunization rate of more than 50% 31 . The highest decrease of HR HPV-related new diseases apart from cervix cancer were consistently reported from countries with vaccination programs and so-called catch-up vaccination of older, non-vaccinated people (Australia, Canada, Denmark, and New Zealand). The programs were implemented nearly always accompanying school education.

Convincing data on respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) are available from Australia 32 . Between 2011 and 2015, pediatricians and otolaryngologists collected data of newly diagnosed cases of juvenile RRP and published them in a meeting report. Only 13 cases had been registered (7 in 2012, 3 in 2013, 2 in 2014, and 1 case in 2015). None of the mothers of those cases had received vaccination. Two strategies are additionally discussed regarding the prophylaxis of RRP in children: first, vaccination of newborns if the mother had condylomas, and second, vaccination of pregnant women with confirmed HPV 6 or 11 infection in order to protect the child against infection by transmission of antibodies. In cases of vaccinated mothers, a similar antibody titer could be measured in newborns 33 .

Oropharyngeal cancer mostly occurs in male patients, in RRP the gender distribution is nearly the same. Numerous other diseases with high stress for the affected patients are related to carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic HPV. What is the benefit that can be expected for other diseases apart from cervix cancer? If consequent vaccination prophylaxis is performed, a dramatic effect might be expected for the incidence of HPV OSCC. Hence, many publications also recommend vaccination of boys, which is absolutely supported by the authors.

3. Carcinogenesis

Carcinogenesis is a process consisting of several steps where genetic and epigenetic modifications in cancer-associated signaling pathways accumulate over time. This results in the typical phenotype of malignant cells characterized by: unlimited replication potential, independence of growth factors, suppressed ability of apoptosis, invasive growth, and metastatic potential as well as increased angiogenesis 34 35 . The individual risk to develop cancer disease depends on extremely diverse and sometimes interdepending factors and is therefore difficult to be determined. The most important risk factor groups include: environmental influences (UV and other natural radiation, anthropogenic substances/radiation), noxae (tobacco/alcohol consumption, HPV infection), genetic predisposition (e. g., BRCA1/2 mutations in hereditary breast and ovarian cancer), immune factors (vaccination, immunosuppression), and age.

The majority of head and neck cancers are squamous cell carcinomas that are mainly associated with the risk factors of tobacco and alcohol consumption or oncogenic HPV. The carcinogenesis of HPV-associated and HPV-negative head and neck cancer is associated with other specific risk factors (see chapter 2). A separate risk to develop one of those two cancer diseases is difficult to estimate because none of the risk factors appears isolated and overlapping of risks is not the exception but the rule.

3.1 Leukoplakia – premalignant alterations

Regarding HPV-negative head and neck cancer, premalignant alterations have been known for several decades, especially in the oral cavity 36 37 . Depending on different risk factors (gender, extent of the lesion, and WHO stage of dysplasia), a transformation rate of 1-2% is estimated. Genetic changes seem to be most probably responsible for malignant transformation while HPV could only be found in 1% of the leukoplakia 38 39 . Generally, the aberration probability of premalignancies cannot be safely predicted and precancerous stages in HPV OSCC could not be reliably identified (see below).

3.2 Field cancerization

Leukoplakias are visible changes that are preceded by macroscopically invisible premalignant lesions. Those invisible lesions may possibly explain the tendency to develop locoregional recurrences after treatment. The correlation of locoregional recurrences with the occurrence of dysplastic changes in neighboring regions coined the term of field cancerization in 1953 40 . Meanwhile this term could be defined with molecular biological and genetic methods. A multistep development model consisting of morphological and genetic modifications was already suggested in 1996 including typical genetic alterations of dysplasia (loss of heterozygosity [LOH] on the chromosomes 3p, 9p, and 17p) and carcinomas (LOH on chromosomes 11q, 4q, and 8) 41 . After some time, it could be shown that at least 35% of oral and oropharyngeal tumors had genetic mutations in mucosal cells in the environment of the carcinomas whereas the epithelium in this area appeared to be normal. This allows the assumption that the carcinogenesis comprises a range of different precancerous stages that are macroscopically invisible and go beyond the resection margins developing locoregional recurrences. Furthermore, focal areas with immunohistological p53 positivity were identified in the neighborhood of carcinomas that characterized “clonal units” and originate from a common precancerous lesion 42 . Mutations in TP53 lead to the expression of an (inactive) tumor suppressor protein p53 and are considered as the earliest oncogenic modification. Together with field cancerization, the multistep development represents the current model of carcinogenesis of HPV-negative head and neck cancer 43 .

3.3 HPV

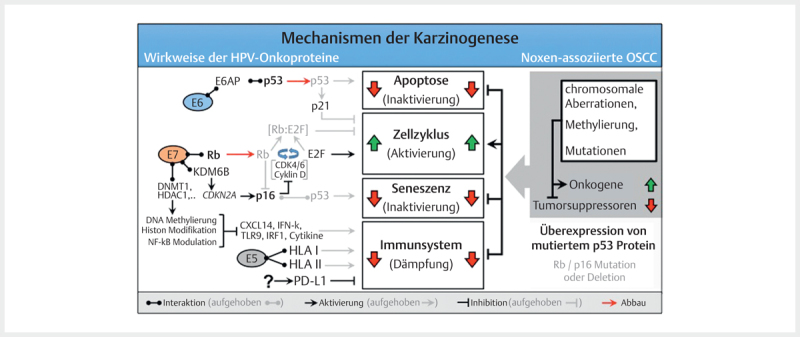

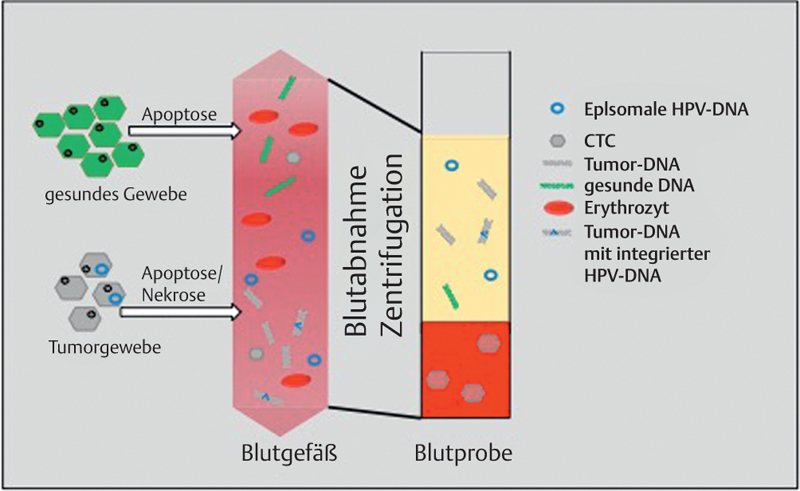

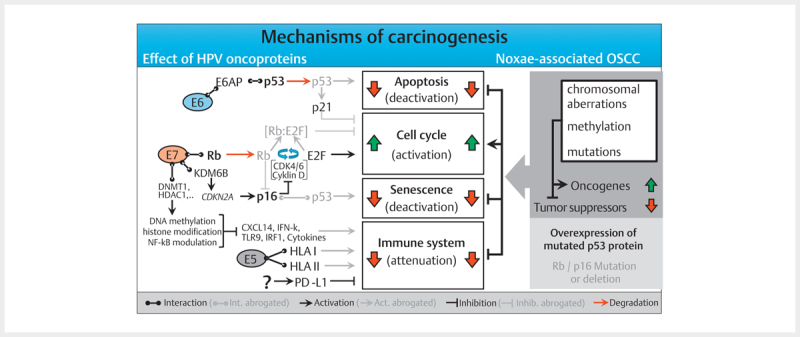

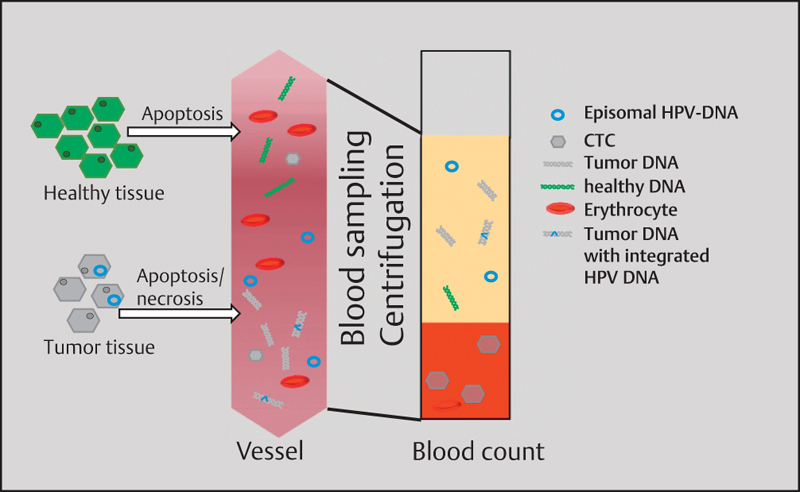

The classic assumption is that viral DNA is integrated into the host cell´s genome during a latently persisting infection with oncogenic HPV. This integration requires linearization of the viral DNA that often occurs as break within the E2 reading frame. The viral E2 protein controls the activity of the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 and the disruption of the E2 reading frame leads to its enhanced expression. In the natural epidermal life cycle of HPV, E6 and E7 inhibit apoptosis and promote the cell cycle, which leads to proliferation of the epithelial cells, and the infections persists ( Fig. 2 ). As a consequence, infected cells are moved into higher skin layers where the activity of E6 and E7 decreases and envelope proteins of the viral capsids are produced. During HPV-associated carcinogenesis, p53 is marked for proteolytic degradation by E6 activity and thus inactivated. E7 binds to the retinoblastoma protein (RB) that triggers the cell cycle and releases the transcription factor E2F. This increases the transcription of genes that are relevant for cell proliferation.

Fig. 2.

The molecular mechanisms of carcinogenesis of HPV- and noxae-associated OSCC (simplified). Dysfunction of the same cellular programs (apoptosis, cell cycle, senescence, and immune system) leads to carcinogenesis in both groups. Multiple genetic mutations that may affect numerous components of the signaling pathways, lead to activation of oncogenes in noxae-associated OSCC and inactivation of tumor suppressors. In contrast, the HPV oncoproteins E5, E6, and E7 lead to interventions in the signaling pathways which dysregulate the same cellular programs. Characteristic for noxae-associated OSCC are mutations of TP53 resulting in inactive p53 overexpression, as well as mutations in the genes coding for Rb and p16INK4A (p16) so that both proteins are reduced. Generally, those mutations are not found in HPV-associated OSCC, and due to the activity of E7, p16 is overexpressed.

In contrast to the stepwise accumulation of genetic modifications in HPV-negative head and neck cancer, these two significant steps occur due to the activity of viral oncoproteins in HPV OSCC. Mutations in TP53 (and the associated overexpression of p53) and HPV induced fields of carcinogenesis are unknown in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. This could be confirmed experimentally by the absence of viral E6 transcription at the resection margins of HPV-associated head and neck cancer 44 . In contrast to cervix carcinoma, where premalignant stages can be detected by staining with acetic acid, premalignancies of HPV-associated OSCC are unknown.

3.4 Genetic modifications

3.4.1 Mutations

In solid tumors, TP53 is the gene most frequently affected by mutations. In a comparative study, whole exome analyses were performed in 15 types of solid tumors, 11 of them revealed TP53 as the most frequently mutated gene, in the other entities it ranked second twice and third once (preceded by KRAS or BRAF and NRAF , respectively) 45 . In HNSCC, the mutation rate of TP53 is in the upper third of solid tumors with about 40%. Interestingly, the cervix carcinoma shows a particularly low percentage of only 6% TP53 mutations, which depends on the very high rate of HPV-associated carcinomas 46 . Mutations appear in many locations of TP53 ; 12 hotspots are known with more than 1% of all mutations each. Nine of those hotspots concern amino acids that contribute directly to the specific DNA binding domain of TP53 or those that are responsible for correct folding of the DNA binding domain. Other mutations are located in introns and influence an alternative splicing of TP53 which has an effect on TP53 isoforms.

Besides TP53 , mutations of CDKN2a and RB1 (RB, retinoblastoma-associated protein) are often observed in HPV-negative head and neck cancer, however, they are missing in HPV-associated OSCC. RB1 encodes RB and such as in p53, the activity of this signaling pathway is dysregulated in HPV-associated head and neck cancer by viral oncoproteins, which may explain the low mutation rate. CDKN2a (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2 A) encodes the tumor suppressor protein p16; its effect in HPV-associated head and neck cancer is eliminated by downstream inactivation of RB. Activating mutations of catalytic subunits of PI3K (phosphoinsitid-3-kinases), in particular in PIK3CA , have been described in several studies, mainly for HPV OSCC 47 48 . In contrast, inactivating mutations in the PIK3CA inhibitor PTEN were often found in HPV-negative HNSCC 49 . PI3K is a multiprotein complex that is involved in the regulation of important functions such as cell growth/proliferation, cell adhesion/migration, differentiation, and survival and that is important for HPV-negative and HPV-associated HNSCC to the same extent.

In several studies, other activating mutations were detected in FGFR3 and FBXW7 in HPV OSCC 47 48 50 51 . The membrane-bound fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) is an activator of the PI3K signaling pathway and FBXW7 is involved in the inactivation of cyclin E, c-Jun, c-Myc, and Notch 1. Mutations in KRAS were also described for HPV OSCC 47 48 , however, this could not be confirmed by own studies 49 . Currently, mutations in HLA and β2 microglobulin genes seem to be relevant that are more often found in HPV OSCC 50 . This could be confirmed by immunohistochemical examinations 52 and might become relevant with regard to immune checkpoint therapies.

3.4.2 Genetic aberrations (copy number variation, CNV)

Because of their extent reaching up to the loss of entire chromosomes or their arms, chromosomal aberrations were the first genetic mutations that could be confirmed in malignant cells. Complex karyotypes with comprehensive numeric and structural chromosomal aberrations are characteristic for head and neck cancer 53 . According to the model of field cancerization, distinct chromosomal modifications with progression of a dysplasia up to invasive carcinoma could be correlated in CGH (comparative genomic hybridization) analyses. The transition from light to moderate dysplasia was characterized by gains on chromosomes 3q26-qter, 5p15, 8q11-21, and 8q24.1-qter and losses on 18q22-qter. Gains on 11q13, 14q, 17q11-22, and 20q and losses on 9p, however, were typical for the transition from moderate to severe dysplasia. Invasive growth correlated with losses occurring together on chromosomes 3p14-21 and 5q12-22 and lymphogenic metastasis with loss on 4p 54 . For the latter ones, also gains on chromosomes 10p11-12 and 11p as well as losses on 4q22-31, 9p13-24, and 14q were described that were not present in respective primary tumors 55 . Interestingly, in the mentioned areas, genes are found that are involved in cell adhesion as well as factors of the MAP (mitogen-activated protein) kinase and PI3K (phosphoinositide-3-kinase) signaling pathway that are also frequently affected by mutations.

Amplifications that are often described for head and neck cancer, are found on the chromosomes 3q-, 8q-, and 20p, independent from the HPV status 47 48 50 56 . Important genes in this region are for example PIK3CA, TP63, SOX2 as well as the oncogene MYC that probably has enhanced activity due to gene amplification. However, 3q amplification was described in the context of the integration of the HPV genome in cervix cancer 57 . In addition, deletions of 13q in HPV-associated and HPV-negative HNSCC have been described, but more rarely in HPV-associated ones which could also be confirmed by whole genome NGS (next generation sequencing) analysis 50 . The chromosomal segment 11q codes genes such as RB1 and CCNA1 (cyclin A) that are involved in the regulation of the cell cycle and that seem to be dysregulated in HPV OSCC by viral oncoproteins.

Generally, an increased chromosomal instability in head and neck cancer seems to be associated with inferior prognosis, which could also be demonstrated in HPV OSCC 58 . Even if nearly the same, but differently dysregulated signaling pathways may be crucial for carcinogenesis of HPV OSCC and HPV-negative head and neck cancer, a series of specific genetic aberrations can be defined for both subgroups. For example, amplifications of 5p, 7p, 8p, 11q, 17q, and 18q could not be verified for HPV OSCC. Clearly more rarely, also losses of 3p, 4q, 5q, 18, and 9p are found. On the last one, for example p16 is encoded which allows the interpretation why the p16 expression works as marker in HPV-associated carcinomas 8 59 60 61 62 .

HPV-specific aberrations are losses on chromosome 16q that are associated with a better prognosis of the patients 50 56 63 . Interestingly, the tumor suppressor gene WWOX is located on 16q. WWOX spans one of 3 most frequent “common chromosomal fragile sites” (FRA16D). Aberrations of FRA16D with dysregulated WWOX expression are known for different tumor types and are associated with a poor prognosis of the patients 64 . Data of the cancer genome project (TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas) identified a HPV-specific amplification on chromosome 20q11 ( E2F1 gene) and a deletion on chromosome 14q32.32 ( TRAF3 gene, TNF receptor associated factor 3) by means of NGS in 279 head and neck carcinomas 50 . An overexpression of E2F caused by amplification of 20q11 might develop synergistic effects in the context of viral oncoproteins (E6&E7 that also activate E2F). TRAF3 loss interferes with the NFκB signaling pathway and thus plays a role in inflammatory reactions as well as the innate and adaptive immune response against viruses 65 .

3.4.3 HPV integration

Although linearization in the E2 reading frame of the HPV genome is understood as first step in the classic model of HPV-induced carcinogenesis, the expression of the oncogene E6 and E7 is independent from the number of copies or the integration of viral DNA, and in more than 60% of HPV OSCC only episomal virus DNA was detected by means of PCR 66 67 . Data of current sequence analyses show that all 3 possible stages of the HPV genome (only episomal or integrated, or a mixture of both) occur with nearly the same frequency and probably several mechanisms lead to dysregulated expression of the viral oncoproteins 68 , including methylation of E2 in the regulator region of E6 and E7 (see below).

It could be shown in HPV transfected keratinocytes that viral DNA integration occurs at many positions within the cellular genome, and also in or near important regulator genes of cell proliferation 69 . In one case of malignant transformation of juvenile (HPV type 6 associated) RRP, HPV DNA integration into the human AKR1C3 gene was described. AKR1C3 encodes an enzyme (aldo-keto reductase family 1 member C3) of the androgen and estrogen metabolism and is described for prostate cancer in the context of PSA production, however, it is mostly undescribed in HNSCC 70 . The role of the virus DNA integration in HPV-associated carcinogenesis is not finally clarified. There seems to be a correlation between chromosomal instability and tumor progression. In contrast, in the same study, HPV DNA integration was associated with a better prognosis of patients with tonsillar carcinomas 58 .

3.5 Epigenetic modifications

3.5.1 Epigenetic modifications of nucleic acids

Epigenetic modifications describe modifications of the hereditary information, whereby the “gene activity” but not the sequence of the nucleic acid is changed. The modification of the nucleic acid influences the phenotype and can be transferred to daughter cells. The most important types are methylation of the DNA and modification of histones. Methylation of DNA (such as the modification of histones) is reversible and its function is to use static information of the nucleic acid sequence in a variable manner. By methylation of transcription factor binding site, the activity of single genes, groups of genes, or entire chromosomes can be controlled, for example in the context of gender-specific inactivation of the X chromosome or genomic imprinting in dependence of the parents’ origin of certain alleles.

Different methylation patterns were described in the context of tumor viruses including HPV 71 72 . The most important example of epigenetic gene regulation with regard to HPV is CDKN2A that is located on the chromosome 9p and encodes the tumor suppressor gene p16. p16 inhibits the cell cycle and its expression is often inhibited in head and neck cancer by gene promotor methylation, mutation, or homozygous deletion of the gene 50 73 . In contrast, a strong overexpression of p16 is observed in HPV OSCC that is understood as surrogate marker for this entity. Contrary to earlier assumptions, this overexpression is not due to the E7-related transcriptional activation of p16 by releasing E2F. Moreover, a direct activation of the cellular senescence by expression of E7 was detected. In this way, the histone H3K27-specific lysine demethylase 6B ( KDM6B ) and its downstream target gene CDKN2A is activated 74 . In HPV-associated tumor cells, Rb is inhibited by E7. Thus, the overexpression of p16 does not lead to an inhibitory effect on tumor cells ( Fig. 2 ). Moreover, the activity of the cyclin-depending kinases 4 and 6 (CDK4/6) seems to be intolerable in the context of Rb inhibition of tumor cells, which causes dependence from the expression of CDK4/6 inhibitor protein p16 and its overexpression promotes carcinogenesis in contrast to HPV-negative tumors 75 .

Besides p16, alternative splicing of CDKN2A produces another gene product, p14ARF. The protein sequence of p14ARF develops through reading an alternative reading frame ( ARF ) of CDKN2A and differs fundamentally from p16. p14ARF inhibits ubiquitin ligase MDM2, whereby p53 is stabilized and the cell cycle regulator p21 is expressed. p21 interacts with and inhibits cyclin CDK complexes, which stops the cell cycle between G2 and the metaphase. The regulation of p14ARF expression occurs by modification of CpG loci downstream the transcription start of p14ARF and p16. Correlation was found regarding their methylation in OSCC with positive HPV status and increased expression of p14ARF but not p16 76 . A relationship of the increasing methylation degree of CDKN2A with increasing grade of dysplasia was observed in the cervix, which in fact does not concern the according promotor region 77 . Also in patients with head and neck cancer, a correlation exists between the methylation pattern and the clinical course. For example, the therapy success could be successfully predicted in head and neck cancer patients based on promotor methylation of only 5 genes ( ALDH1A2, OSR2, GRIA4, IRX4 , and GATA4 ) 71 78 .

The classic explanation model of HPV-associated carcinogenesis is based on an integration of viral DNA into the human genome, which leads to an interruption of the E2 reading frame and an elimination of the inhibition of viral oncoproteins E6 and E7. Frequently, further episomal HPV copies are present beside integrated HPV DNA; and in about one third of HPV-associated OSCC, exclusively episomal virus DNA is detected. Here, the classic explanation model is apparently not satisfactory and a methylation of the E2 binding site in the regulation region for E6 and E7 in the HPV genome was identified as further integration-independent regulatory mechanism for the expression of E6 and E7 79 80 .

3.5.2 microRNA expression

microRNAs (miRNA) develop from hairpin bend-like precursor transcripts of 60-70 nucleotides that are shortened to a length of about 22 nucleotides. Together with the proteins DICER1 and Argonaute (AGO) they are integrated in the miRNA-induced silencing complex (miRISC) and guide it, based on their sequence, to corresponding target sequences of the mRNA that is subsequently cleaved enzymatically and thereby inactivated. This relatively simple regulatory mechanism of gene expression is clearly more complex in reality because miRNAs – depending on the conservation grade of their target sequence – may bind to different mRNAs and mRNA may dispose of binding sites for more than one miRNA.

Despite methodical progress during the last years, only few comparative studies have been conducted on the differential expression of miRNAs with regard to the HPV status in head and neck cancer; only a “handful” of miRNAs have been mentioned in more than one study 81 . In one of the most recent trials, 1,719 miRNA sequences were evaluated in 15 HPV-negative and 11 HPV-associated OSCC by means of microarrays. A total of 25 differentially expressed miRNAs could be identified, their functions were elaborated in silico in the context of the PI3K and Wnt signaling pathways, the regulation of the cytoskeleton, and the focal adhesion 82 . The mostly known miRNAs include Has-miR-363 that is upregulated in HPV-associated HNSCC in contrast to HPV-negative ones 83 84 85 . Target sequences of Has-miR-363 are found for example in CDKN1A (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1), CASP3 (Caspase-3), and CD274 (programmed cell death 1 ligand 1, PD-L1) and they indicate regulatory functions in apoptosis, cell cycle, transcription, and immunology. Another example is miRNA203; its expression is downregulated by the HPV oncoprotein E7 during cellular differentiation. A target gene of miRNA203 is the transcription factor p63; and the expression of p63 as well as its downstream target genes like CARM-1, p21 , and Bax , are increased by the inhibition of miRNA203 by E7 86 . Hereby, epithelial cells remain proliferative and in an undifferentiated stage which is required for the natural lifecycle of HPV. In the HPV E6/E7 induced tumor model in human keratinocytes, p63 enhances the invasiveness by modulation of the Src-FAK (focal adhesion kinase) signaling pathway by dissolving focal cell contacts (cell adhesion) and restructuring the extracellular matrix (ECM) 87 .

Beside cellular miRNAs, miRNAs were detected encoded in the HPV genome, which could be confirmed experimentally. Potential target sequences of those miRNAs are found in the HPV genome but also in the human genome 88 . Interestingly, target sequences of two less frequent human miRNAs were also identified in the HPV- E6 gene (miR-875 and miR-3144). In HPV16-positive cell cultures, both inhibit growth and induce apoptosis 89 , which demonstrates the complex regulatory possibilities by means of miRNAs.

3.6 Dysregulation of tumor metabolism

Tumor hypoxia was described as being important for the survival and therapy response of head and neck cancer 90 91 92 . It is well-known that patients with tumor hypoxia respond poorly to irradiation because of the reduced presence of reactive oxygen species (ROS). During the tumor growth, also a tumor-specific metabolism develops in order to assure the supply and the proliferation of the cells. A specific feature of this metabolism is the increased decomposition of glucose to lactate which was first described under aerobic conditions as “Warburg effect” in 1924. The decomposition of glucose to lactate, however, only provides 2 Mol ATP per Mol of glucose, which is compensated by an increased glucose rate 93 94 95 . Beside energy, this adapted glucose metabolism of the tumor serves for providing important basic building blocks (e. g., nucleic acids, amino acids, and lipids) 96 .

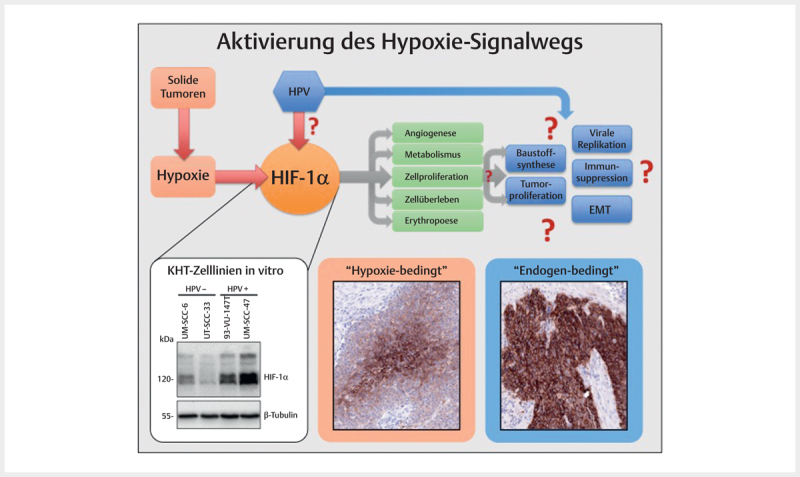

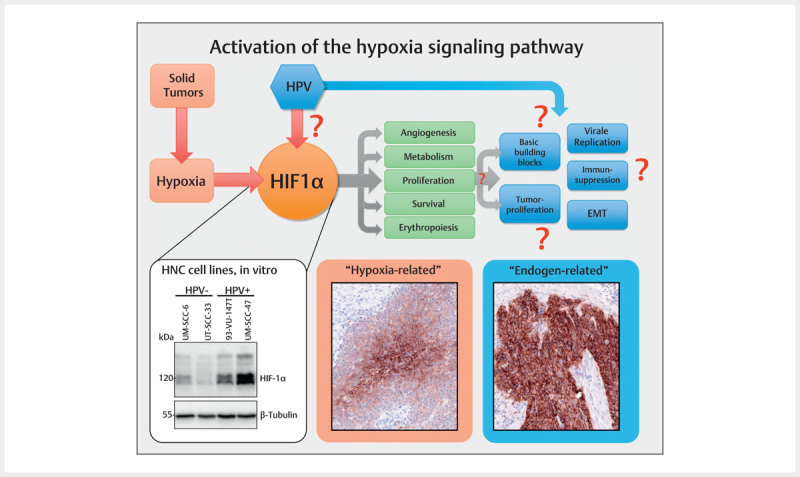

Hypoxia occurs frequently in many solid tumors and arises because tumor cells proliferate rapidly,exceeding a critical mass which leads to obstruction and compression of the blood vessels in the direct neighborhood of the tumor. This finally results in poor oxygen supply of the tumor centers so that the tumor cells adapt to this oxygen deprivation and several signaling pathways are switched on in order to secure cell survival and to change the glucose metabolism from efficient oxidative phosphorylation to inefficient glycolytic metabolism 97 . Hereby, the group of HIF (hypoxia-inducing factor) transcription factors, in particular HIF-1 (HIF-1α & HIF-1β), play a key role for the cellular adaptation to hypoxic conditions. HIF-1 activates a series of target genes that secure cell survival, serve for the modification of the metabolism, and promote invasion, cell proliferation, metastasis, erythropoiesis, and angiogenesis 97 98 99 . Beside real tumor hypoxia, it could be demonstrated in cell lines that HPV oncoproteins contribute to hypoxia pathway dysregulation by stabilizing HIF-1α ( Fig. 3 ) 100 101 102 .

Fig. 3.

Frequently, in solid tumors an activation of the hypoxia signaling pathway is found that is obvious due to the central expression of respective marker proteins (here: Glut I) in tumor nests and that can be confirmed by immunohistochemistry (hypoxia-related). Some tumors, however, show a consistently high expression of the same marker that suggest other activation mechanisms of the signaling pathway (endogen-related). The central regulator protein of the hypoxia signaling pathway HIF-1α is present in HPV associated tumor cells in an overexpressed way compared to HPV-negative tumor cells (Western-blot, bottom left). In analogy to fig. 2 , the viral activity leads to activation of the hypoxia signaling pathways and thus to processes that are favorable for carcinogenesis.

Thus, oncogenic viruses are able to influence the tumor metabolism by direct and indirect interaction with cellular regulators such as HIF-1α, in order to adapt cellular pathways for viral replication and synthesis, which also promotes carcinogenesis and progression. This metabolic phenotype allows tumor cells to proliferate despite adverse circumstances like oxygen deprivation 103 . Hence, the signaling pathways that are used for modification of the metabolism and their regulators such as e. g., HIF-1 represent potential targets for an inhibition, in particular for those tumors that largely depend on glucose and aerobic glycolysis.

3.7 Tumor environment/immune escape mechanisms

During the development of invasive, HPV-associated squamous cell carcinoma, several lines of defense mechanisms have to be overcome. Viral infection is the first step, for which the physical barrier of skin/mucosa plays a crucial role. After absorption of viral particles, those have to traverse the cell and reach the nucleus. In the following persisting infection, the HPV oncoproteins E5, E6, and E7 have important functions to remain undetected by the immune system as long as possible and to maintain the production of new viruses in the epithelial cells. In the microenvironment of HPV-infected cells, increasingly cells of the innate immune response are found such as dendritic cells (DC) Langerhans cells (LC), natural killer cells (NK), and natural killer T cells (NKT) 104 .

To a high percentage, HPV infections heal by themselves, and only in a small part, cancer develops. In such cases, further modifications have to take place that enable infected cells to overcome the physical barrier of the basement membrane and to be resistant against the continuous attacks of the immune system. For example, higher rates of HPV infections and HPV-associated carcinomas are known in patients with different NK cell dysfunction 105 . In the context of viral reproduction and evolution, this last step of carcinogenesis has a dead end, because due to the missing differentiation of the epithelial cells, virus particles can neither be produced nor transmitted to the outside. HPV-associated tumors, as well as HPV-negative tumors, are in a steady-state with the immune system and when the disease is diagnosed, this equilibrium has already been shifted to the benefit of the tumor, and growth is observed that cannot be controlled by the immune system. The understanding of the immune escape mechanisms can be used to restore the equilibrium or to shift it to the benefit of the immune system.

A physical immune escape mechanism of HPV consists in operating its complete lifecycle within the epithelial cells and not releasing virus particles into blood or tissue. Thus, HPV antigens are barely exposed to the immune system and antibody titers are not high enough during natural HPV infection to have a protective effect 106 . Nonetheless, apparently T cell response is required for regression of an infection because it correlates with the presence of granzyme B positive cytotoxic T cells in the context of cervix premalignancies 107 .

The oncoproteins E5, E6, and E7 have an effect on many cellular mechanisms, among others they suppress signaling pathways that are necessary for the recognition of virus-infected cells by the immune system. For example, the surface protein CXCL14 works as chemokine and attracts different cells of the immune system such as DC, LC, NK, and NKT cells. E7 interacts with the cellular DNA methyltransferase DNMT1; and an E7 dependent promotor methylation and thus repression of CXCL14 could be shown 108 . Furthermore, E7 modulates the methylation and acetylation of histones, which lead (among others) to the reduction of the TLR9 (toll-like receptor 9) expression and transcriptional activity of IRF1. TLR9 is able to recognize viral DNA and to activate the innate immune system 109 . IRF1 response elements are found in promotors of a series of genes such as TAP1 (transporter associated with antigen processing 1), which plays a role in antigen charging of HLA-I in the endoplasmatic reticulum 110 . In addition, E7 interacts with NFκB and inhibits its translocation in the nucleus. Hereby, for example activation of IFN-α, IL-6, and TNF-α is stopped, which leads to attenuation of the inflammatory reaction 111 .

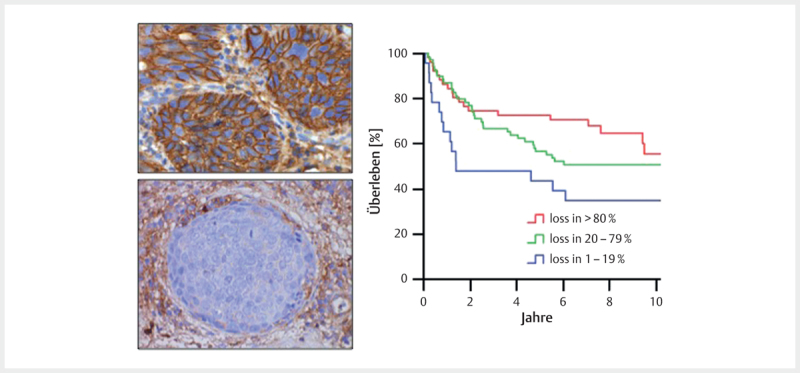

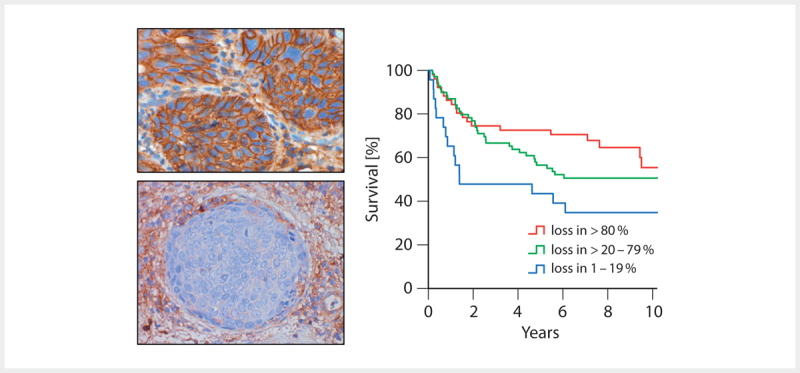

Inflammation inhibiting functions could be revealed for E6 in the context of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β. Depending on E6AP, E6 causes the ubiquitination of the precursor of IL-1β (pro-IL-1β), which is followed by its proteasomal degradation 112 . For the E5 protein, an interaction with the heavy chain of HLA-A and -B could be detected, which leads to retention of the HLA-I complex in the Golgi apparatus and in the endoplasmatic reticulum 113 114 . HLA-C and HLA-E seem to be downregulated by other mechanisms. The loss of HLA-I on the cell surface correlates with a reduced response of CD8+ T cells in E5 expressing cells. However, loss of HLA-I leads to attraction and activation of NK cells, which was already described for HPV-associated OSCC and correlates with an improved overall survival of the patients ( Fig. 4 ) 115 . Beside HLA-I, the functional surface location of HLA-II as well as CD1d is also inhibited by E5 116 117 . The viral capsid protein L2 seems to block the maturation and antigen presentation of DC and LC by disturbing the intracellular transportation and processing of virus particles after integration of DC and LC 118 .

Fig. 4.

Immunohistochemical proof of the expression of β2 microglobulin (β2M) as marker of functional membrane-based HLA I expression (top left). The loss of the expression of β2M on tumor cells (bottom left) correlates with a better overall survival of patients with OSCC (right).

3.8 Molecular subtypes and gene expression profiles

Whole genome gene expression analysis are generally based on a comparative hybridization (microarrays) or sequencing of mRNA. The capacity of microarrays as well as the sequencing techniques have continuously improved over time, which leads to an increasing coverage of the genome, but also to limited comparability of former and current data.

In one of the first gene expression studies of head and neck cancer, 60 differentially expressed genes were identified from 1,187 examined tumor-associated genes on a cDNA microarray. They correlated with the radioresistance or the response to radiotherapy 119 . Already 3 years later, 60 head and neck tumors were examined on a cDNA microarray with probes against 12,814 human genes. In this study, 4 subtypes could be identified based on the gene expression. Signatures were found with a focus in the EGFR signaling pathway, a mesenchymal subtype, a subtype with expression pattern of normal epithelium, and a subtype with enhanced antioxydase enzymes 120 . However, in all early studies, no attention was paid to the HPV status of the samples. Similar gene expression profile groups, called basal, mesenchymal, atypical, and classic types, were identified in another study by means of Agilent 44 K microarrays. An enhancement of HPV associated specimens was observed in the group of atypical gene expression (e. g., with increased expression of CDKN2A ) 121 . By means of another platform (Illumina Expression BeadChips) also 4 subtypes were identified. However, only the classic expression type was confirmed as being comparable to the above-mentioned study 122 , which is probably due to technical differences or the heterogeneity of the specimens.

In 2015, a clinically relatively homogenous cohort of 134 head and neck tumors with a percentage of 44% HPV-association, was examined with an Agilent 4×44Kv2 expression array. Afterwards, the data were summarized with already published data to a cohort of more than 900 patients. In this trial, 5 subtypes were identified that included 2 groups of HPV-associated and 3 groups of HPV-negative head and neck tumors. One HPV-associated and one HPV-negative subgroup showed an immune/mesenchymal expression pattern as well as the expression type that was described above as “classic” 123 124 125 . The remaining HPV-negative group showed a basal expression pattern with overrepresentation of hypoxia-associated genes (e. g., HIF1A, CA9 , and VEGF ), epithelial markers (P-cadherin, cytokeratin KRT1 and KRT9 ), and components of the neuregulin signaling pathway. In contrast to this basal expression group, both HPV-associated groups did not reveal modification regarding the number of copies or the expression of EGFR/HER ligands 126 .

The knowledge gained from genome-wide expression analyses could not be implemented translationally until now. This is due to missing technical standards, which limits comparability of the results. On the other hand, the total number of analyzed samples is relatively low, so that for example heterogeneity because of patient characteristics cannot be subtracted. In the future, this might be different due to technical advances analyzing retrospective, formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) archive specimens. In a pilot study, 4 tumor samples of HPV-associated and 2 HPV-negative OSCC were analyzed by means of a NanoString gene expression assay and Ion Torrent AmpliSeq cancer panel tNGS. From 230 tumor-associated genes, several ones were correlated with a positive HPV status (e. g., WNT1, PDGFA , and OGG1 ). By hierarchic classification, 6 groups of differentially expressed genes were identified 127 . Thus, the use of FFPE materials that are currently not broadly analyzed, might increase the significance and reliability of data from expression analyses in future.

4. Clinical Particularities

4.1 Is HPV-associated OSCC a sexually transmitted disease?

The transmission of HPV occurs mainly via skin contact or contaminated objects. Afterwards, infection of epithelial cells may develop with extremely high host specificity. HPV infects undifferentiated cells directly above the basement membrane through microwounds or in very thin epithelia. While the infected cells remain close to the basement membrane, the viral DNA replication is reduced. This is due to the fact that the viral development processes are coupled with the differentiation processes of the infected cells while they move up to the epithelial surface. Whereas the regulatory “early” proteins (E) are produced in the early HPV cycle, the “late” proteins L1 and L2 that represent the capsular structure of the viral particles are processed later in the life cycle. Together with viral DNA they build infectious virus particles that are released to the environment together with the external epithelial cells.

Typically, for example after visiting swimming pools children develop plantar warts because of infections with the low risk HPV types 1, 2, and 4. Another transmission pathway is the perivaginal transmission during birth which may induce the development of laryngeal papillomatosis in infants and toddlers 128 . For the HPV-associated OSCC, the sexual transmission pathway with the high-risk papillomaviruses 16 and 18 is in the focus of discussion. The severely increasing incidence in the last decades is mainly explained by changed sexual behavior, younger age at first sexual contact as well as the increased practice of oral sex 129 . Even if the genital-genital transmission of HPV infection seems to be predominant, also other transmission pathways such as anal-genital, oral-genital, manual-genital contact, the use of sex toys as well as autoinoculation are possible 130 . In 2 cohorts in the USA, it could be shown that patients with HPV OSCC had a higher rate of promiscuity (vaginal, anal, oral) in comparison to patients with HPV-negative tumor. Furthermore, (oral) sex with frequently changing partners, casual sex as well as rare use of condoms were reported. Light-skinned patients, singles as well as divorced patients mentioned a higher number of sex partners. Regarding the income, no difference could be found concerning the number of sex partners, while patients with a higher educational status reported a higher number of sex partners. After performing gender stratification, the changed sexual behavior could be confirmed mainly in men 131 132 .

For new life partners, there seems to be the risk of transmission. But the data up to now do not allow valid conclusions. Since the intermittent or missing use of condoms is associated with an increased risk of oral HPV infection or HPV-associated OSCC, the use of condoms probably protects against transmission of oncogenic HPV 21 129 . For nicotine and alcohol, no association with HPV OSCC could be detected. However, the consumption of marihuana was strongly associated with HPV-associated tumors. Patients with more than 10 pack-years of tobacco consumption had a higher number of sex partners than patients without or only low nicotine abuse. There was no evidence for multiplicative effects for HPV OSCC between nicotine and alcohol, marihuana and nicotine, or marihuana and alcohol 131 132 .

In summary, the reason for the increased occurrence of HPV OSCC is seen in the changed sexual behavior. However, it must be questioned in which way and actually if it has really changed over the years. The causal reason for the increase of HPV associated carcinomas in the oropharynx still cannot be answered with certainty.

4.2 Clinical particularities of HPV-associated OSCC

In some countries, patients with HPV-associated OSCC are often rather young 131 133 , but regional differences are observed. In our own cohort of 396 patients who were treated in Giessen between 2000 and 2009, no significant age difference could be detected in OSCC patients depending on the HPV status ( Table 1 ). Often a higher socio-demographic as well as socio-economic status (higher education level, higher profession position as well as income) is found in comparison to patients with HPV-negative OSCC 134 . Especially in the USA, males are generally more frequently affected (ratio male/female: 1.5), while the quotient for Asia and some European countries is only 0.7 135 . It is assumed that this is due to a higher transmission rate of HPV infections during orogenital sex 130 , and the higher nicotine abuse of males predisposes them for infection 21 .

Table 1 Clinical differences in HPV OSCC, n=396.

| Non-HPV OSCC | HPV OSCC | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N | % | N | % | p value | |||

| 308 | 80.6 | 74 | 19.4 | |||||

| Gender | Male | 306 | 238 | 80.7 | 57 | 19.3 | 0.964 | |

| Female | 90 | 70 | 80.5 | 17 | 19.5 | |||

| Comorbidity | ECOG | |||||||

| Healthy | 0 | 257 | 87 | 76.0 | 59 | 24.0 | 0.002 | |

| 1–2 | ||||||||

| Sick | 3–4 | 134 | 118 | 89.4 | 14 | 10.6 | ||

| ≥5 | ||||||||

| Age | Young | (<60 years) | 210 | 162 | 80.6 | 39 | 19.4 | 0.987 |

| Old | (≥60 years) | 186 | 146 | 80.7 | 35 | 19.3 | ||

| Alcohol | >2 standard glasses | 161 | 144 | 92.3 | 12 | 7.7 | 0.000 | |

| <2 standard glasses | 123 | 69 | 59.0 | 48 | 41.0 | |||

| Nicotin | >10 py | 319 | 270 | 87.7 | 38 | 12.3 | 0.000 | |

| No | 60 | 29 | 50.0 | 29 | 50.0 | |||

First symptoms that occur in patients with OSCC include sore throat, odynophagia, or globus sensation. In the further course, dysphagia or cervical swelling may be observed. Frequently, the cervical swelling is the first and only symptom of HPV OSCC that lets patients seek for medical advice. This is mainly due to the already advanced N stage with low T stage. In the context of HPV association, the primary tumor is often located at the tonsil or the base of the tongue 133 136 whereas other locations of the oropharynx are rarely affected.

While smoking and alcohol abuse are the classic risk factors for head and neck cancer, there are important geographic differences with regard to the incidence of nicotine abuse. A significant decrease could be observed between 1980 and 2012 in Northern Europe as well as North America 137 . While HPV 16 and nicotine abuse were considered as independent risk factor till recently 131 , a patient cohort in the USA revealed a higher risk of HPV OSCC after nicotine abuse 138 . In cases of HPV OSCC, nicotine abuse seems to have a negative impact on the survival whereas alcohol seems to play only a secondary role 139 140 . In total, the mortality risk of patients with HPV-associated tumors, however, seems to be reduced by more than 50% in comparison to patients with HPV-negative OSCC. This improved therapy outcome is most likely associated with the improved locoregional control, among others by increased radiation sensitivity (see chapter 6).

Second primaries are significantly more rarely observed in patients with HPV OSCC. If this is possibly due to missing risk factors such as nicotine or alcohol abuse is unclear because more recent studies report about increased nicotine abuse also in patients with HPV-associated OSCC. The good prognosis of those patients increases the number of patients in follow-up examinations and the duration of follow-up is longer so that therapy-associated long-term complications such as dysphagia, xerostomia, or dysgeusia are in the focus. In future, therapy de-escalation plays a key role in order to improve the patients’ quality of life. Furthermore, the implementation of a sufficient tertiary prophylaxis in those patients with long-term survival might be important in order to early detect recurrences or distant metastases even in the long-term follow-up (see chapter 7).

5. Diagnostics and Staging

HPV-negative and HPV-associated OSCC vary significantly regarding their clinical course and biology. It is worth mentioning that a clear and valid procedure for the diagnosis of HPV-induced head and neck carcinoma does not exist. In single cases, even after performing extensive laboratory examinations, it is not evident if a tumor is HPV induced or not. Probably, it can be assumed that the triggering factors of carcinogenesis coincide in many cases of OSCC. The established methods include immunohistochemical p16 staining (p16 test), the detection of HPV-specific nucleic acids (HPV DNA test), and in situ hybridization (HPV ISH) in tissue section.

5.1 Test procedures for the diagnosis of HPV-associated oropharyngeal cancer

For clear definition of the HPV status in head and neck cancer, the presence of HPV as well as the detection of oncogenic activity in tissue specimens is required. The test results are then applicable as prognostic markers for patient counseling and also for planning future therapies. Testing of both preconditions, however, may also provide false-positive or false-negative results because of technical and biological reasons. So the misinterpretation of a test may have substantial consequences for the patients. Up to now, prospective studies are not available that justify concrete adaption of the therapy based on the HPV status, although a recent study from the USA reveals that already more than half of the physicians choose treatment strategies based on HPV tests 141 .

The laboratory diagnosis of the HPV status generally consists of the detection of viral DNA in biopsies and is performed mainly by sensitive PCR-based test procedures or the less sensitive ISH 142 . The high sensitivity of PCR-based procedures bears the disadvantage of contamination, for example due to parallel HPV infections. Biologically inactive HPV DNA in the tumor tissue show signals that cannot be differentiated. In contrast, the signal distribution in HPV ISH may provide hints regarding the HPV association, which, however, requires more efforts and does not differentiate biologically inactive HPV DNA as well. As “gold standard” for oncogenic activity, the detection of viral mRNA transcripts of the oncogenes E6 and E7 by means of RT-PCR is acknowledged. The natural instability of mRNA leads to a high specificity because free mRNA can practically be excluded as basis of contamination, but hereby also the sensitivity is lower. Furthermore, the examination of specimens for mRNA is more complex, unfixed tissue is needed in most cases and the detection of mRNA transcripts does not necessarily correlate with a protein expression of viral oncoproteins or their biological activity.

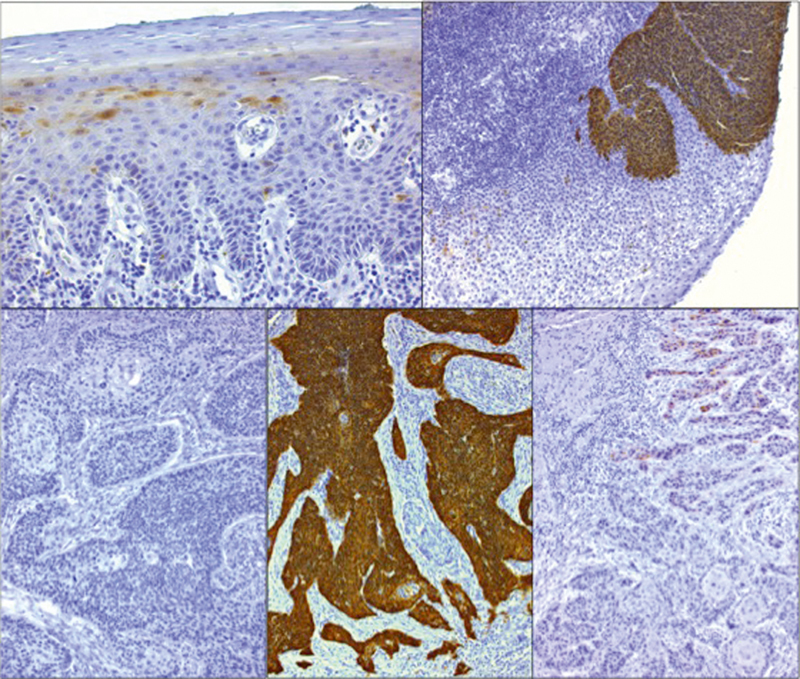

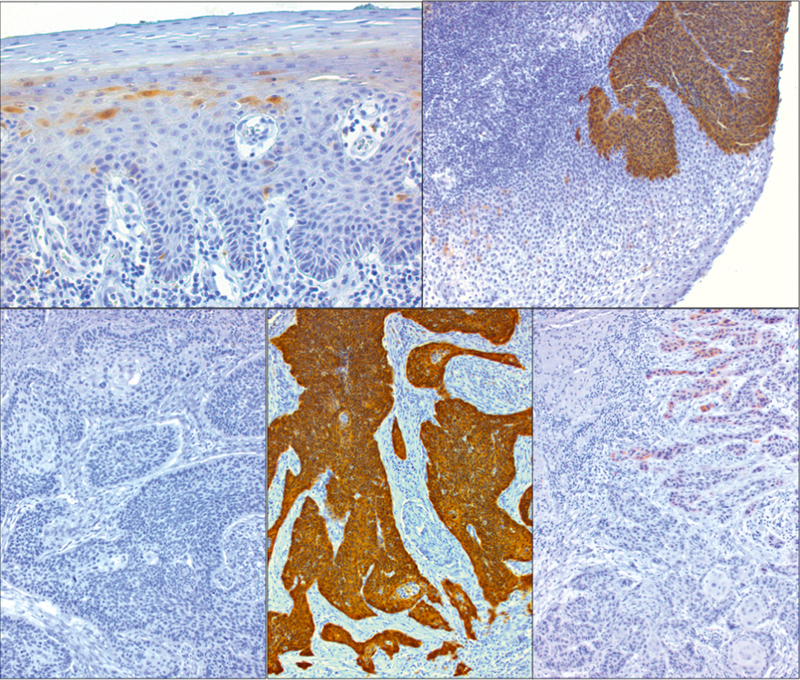

The relevant characteristic of HPV-associated carcinogenesis is the virus-oncoprotein-caused dysregulation of the cell cycle via the Rb signaling pathway and the inhibition of apoptosis by inactivation of p53 (see chapter 3). Also in HPV-negative tumors, inactivation of p53 occurs, however, generally due to mutations in TP53 , which may become obvious immunohistologically by detection of overexpressed but inactivated p53. In HPV-associated carcinomas, p53 is missing and the tumor suppressor protein p16 is overexpressed due to viral oncoprotein activity ( Fig. 5 ). The overexpression of p16 in tumor cells is rare, however, it is observed in different cancer entities and in about 5% of oropharyngeal carcinomas even independent from HPV 59 . Because of a moderate specificity, the p16 test alone is only partially sufficient for determination of the HPV status. In combination with a detection of viral nucleic acids, the sensitivity and specificity can be increased significantly ( Fig. 6 ). The combination of p16 test with HPV DNA tests is acknowledged to be the most practicable test combination for the clinical use 142 .

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical proof of p16INK4A protein expression in single cells of healthy squamous epithelium (top left). Generally, p16INK4A is missing in HPV-negative squamous cell carcinomas of the oropharynx (bottom left). However, strongly overexpressed p16INK4A is present in HPV-associated OSCC (bottom, in the middle) and dysplasia (top right). Single OSCC sometimes show a weak expression of p16INK4A (bottom right) that cannot be considered as positive in the context of HPV-diagnostics.

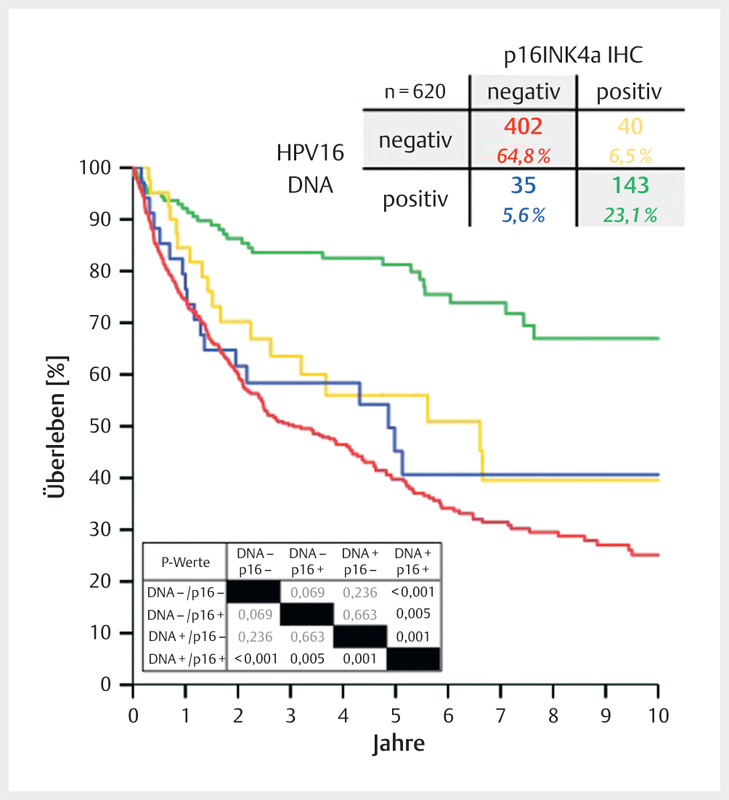

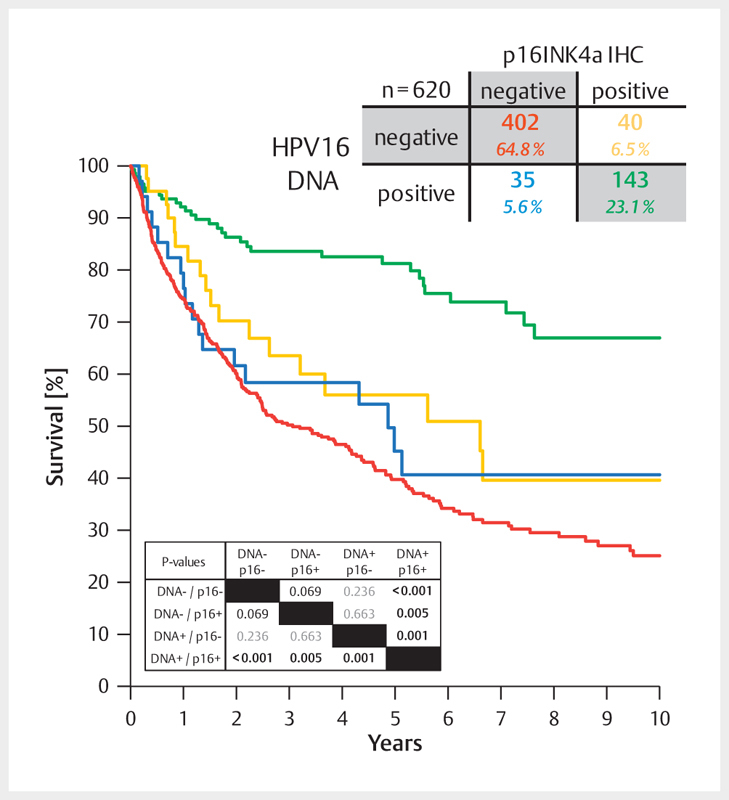

Fig. 6.

Between 2000 and 2015, the average prevalence of HPV-associated OSCC (HR-HPV DNA and p16INK4A-positive samples) amounted to 23% in Giessen. About 6% of all cases revealed discordant results of HPV DNA and p16INK4A tests, each. The survival of those patients (blue and yellow lines) was significantly inferior compared to patients with HPV-associated OSCC. However, it hardly differed from the survival of patients with HPV-negative OSCC (red line).

The examination of saliva was also evaluated regarding HPV association. This method is easy, inexpensive, and might be applicable for prophylaxis, therapy monitoring, and follow-up. First articles on this topic were already published more than 20 years ago; a good correlation of PCR test results from saliva (oral rinses) and tumor biopsies of 190 patients could be elaborated 143 . However, a really convincing specificity and sensitivity (between 50 and 70%) could not even be reported in recent investigations 144 . In the context of local tumor recurrences, it could be shown exemplarily that the detection of HPV material is possible 145 . The results, however, are naturally falsified by frequent oral HPV infections. Also the detection of oncogenic active HPV infections could not be successfully performed.

In most patients with HPV-associated OSCC, HPV-specific antibodies are found in the blood already several years before diagnosis 146 147 . The antibodies directed against the oncoproteins of HPV probably do not develop during infection but only years later during malignant transformation. This could be demonstrated in a cohort of young men with HPV infections who had no seropositivity against HPV 16 E6 protein 148 . The detection of antibodies against HR-HPV E6 and E7 correlates well with the prognosis of patients, comparable to the tissue HPV test 149 . Based on annual blood tests, a recently published investigation of about 1000 control patients calculated the risk to develop HPV OSCC with more than 5% (more than 100 times higher than with negative test) when E6 antibodies could be found at the testing time 150 . A positive antibody test cannot be assigned to a certain lesion, neither under a time nor a spatial aspect, so the diagnostic benefit for the determination of the HPV status is rather low. However, excellent applications are possible for early detection. As a limitation, however, it must be mentioned that the test procedures are not generally available.

5.2 Significance of tumor endoscopy

Tumor endoscopy is mainly used for painless histology gaining as well as estimation of the tumor size in order to determine the resectability of the tumor and possible reconstructive procedures. Furthermore, in the context of tumor endoscopy the presence of a secondary carcinoma shall be excluded, this mainly applies for patients with noxae abuse. However, the performance of tumor endoscopy or panendoscopy or triple endoscopy is critically discussed for all head and neck tumors. So there is nearly no international consensus regarding the significance and technique. Based on the further development of imaging procedures, the risk of rigid endoscopy, and unclear incidence of second primaries, it is increasingly negatively discussed 151 . The significance of tumor endoscopy in the context of HPV OSCC can be questioned most critically because those patients often do not have a positive history of noxae abuse that might lead to secondary carcinoma 152 153 . So the value of endoscopy is rather low regarding the question of secondary carcinoma in those cases. In Germany, the performance of tumor endoscopy with rigid instruments is still widespread 154 . As long as there is no reliable evidence, endoscopy may be performed in the current standardized way, however, for HPV OSCC also system oriented biopsy under general or local anesthesia can be performed without any concern.

5.3 Imaging

Imaging diagnostics of HPV OSCC correspond to the standardized imaging of head and neck cancer. For example, ultrasound of the neck is performed for imaging of regional tumor disease. Also computed tomography (CT) and magnet resonance imaging (MRI) are routinely applied. Those procedures are used for morphological description of head and neck tumors. In comparison, positron emission tomography (PET) in combination with CT scan is a hybrid procedure that shows a functional image of the metabolic situation in the affected tissue. Hereby the radioactive isotope 18 F of fluorine is the nuclide that is mostly used in PET and can be combined with several pharmaceutics. The combination that is most frequently applied, is the metabolic radiotracer 18 F-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-glucose (FDG), possible alternatives are hypoxic radiotracers such as 18 F-fluoromisonidazol (FMISO) or the next generation 18 F-fluoroazomycin arabinoside (FAZA) 155 .

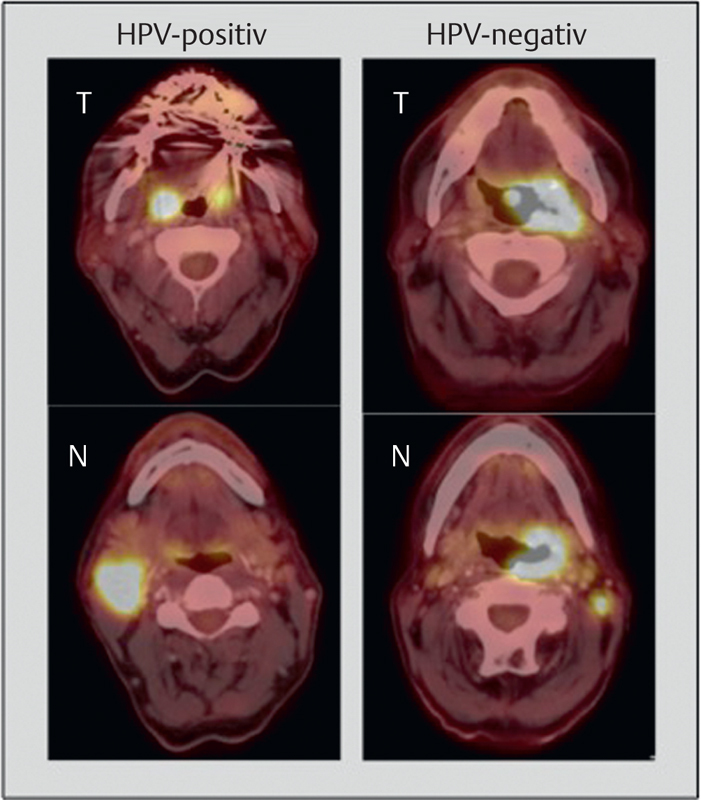

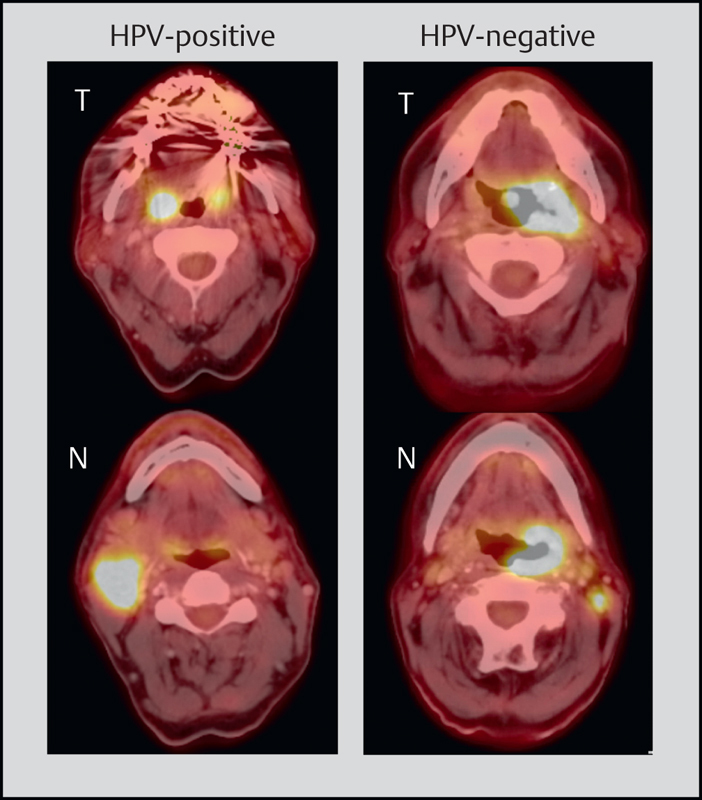

Because of the distinct tumor metabolism of HPV associated OSCC in comparison to HPV-negative OSCC (see chapter 3.6) ( Fig. 7 ), differences in the functional imaging may be expected 156 . So HPV-specific tumor characteristics possibly reflect in 18 F-FDG PET-CT. For example, it could be shown that HPV-associated OSCC in the context of epithelial mesenchymal transition (EMT) has clearly more homogenous FDG and FAZA tracer uptake 155 157 , and own data (in press)]. In concordance, a significant increase of the PET parameters of HPV-negative OSCC is observed with increased size of the primary tumor 155 . In comparison, HPV OSCC provide a clearly more homogenous image of tracer uptake in different tumor stages.

Fig. 7.

The current staging for HPV-positive and HPV-negative OSCC was changed significantly. On the left, metastatic HPV OSCC (ipsilateral, <6 cm) is displayed, this means tumor stage I; according to the former edition, the tumor would have to be classified as stage IVa (T1, N2b). On the right, a T3N1 OSCC, HPV-negative, is displayed, to be classified as stage III. Thus, the tumor stage of the patient on the left is lower in comparison to the patient on the right.

But functional imaging is not only applied in the context of staging procedures, it serves also as therapy monitoring. Currently, the controversially discussed therapy de-escalation for HPV OSCC is in the focus. In a prospective study (DAHANCA 24), it was recently possible to demonstrate that performing FAZA-PET/CT in the context of primary radiotherapy may be promising as monitoring for positive therapy response 158 . In another pilot study, it could be shown for HPV-positive OSCC patients that FMISO PET before and during therapy reflects the tumor charge. It might also be possible to reduce the irradiation dose in cases of positive treatment response 159 . Furthermore, the functional imaging has become essential for follow-up. In a prospective multicenter trial, a high significance of 18 F-FDG PET CT could be revealed for the follow-up of OSCC primarily treated with RCT. Hereby it became obvious that 18 F-FDG PET-CT as diagnostic tool for detection of regional residues was not inferior to a standard arm with post-therapeutic salvage neck dissection, which is due to the high sensitivity of this test procedure. In addition, complications and expenses could be reduced by imaging 160 .

A new option of imaging are radiomics procedures. Hereby image features are quantified by computer assistance, clusters are created and then compared with imaging databases in order to draw conclusions regarding tissue properties, diagnosis, and courses of the disease. For example, such a computer-assisted prediction of the HPV status is relatively reliable based on a CT dataset 161 . Radiomics signatures were applied successfully as prognosticators for example in breast cancer patients, but also in lung and head and neck cancer 162 163 . By combining the radiomics signature and the p16 test, the prognostic selectivity between 2 groups of head and neck cancer patients could be improved 164 . In the future, radiomics datasets might be included in prognostic models.

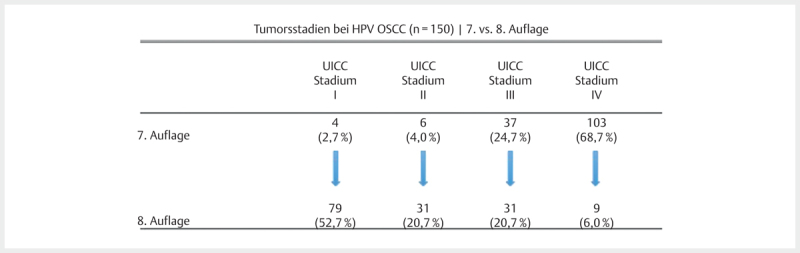

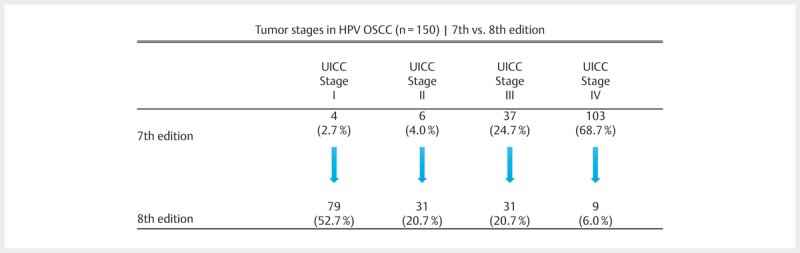

5.4 Revised TNM classification and staging rules

The TNM classification of malignant tumors mainly serves as prognosticator. The increasing incidence, different biology of the disease, and the clearly improved prognosis after therapy justify the necessity to consider HPV OSCC as independent tumor entity. The main reason is the fact that the established staging rules only insufficiently reflect the prognosis of the patients. In particular regarding the nodal status, it was demonstrated several times that there is no significant influence on the prognosis of the patients based on former TNM rules 165 166 . Only with regard to advanced T stages, a selectivity for the prognosis based on former TNM rules was reported 167 168 . With the recent publication of the 8 th edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumors, the HPV status of OSCC is considered. Also the TNM rules for HPV-negative OSCC were modified, the factor extracapsular spread (ECS) or extranodal extension (ENE) is now included. HPV-negative OSCC are classified as hypopharyngeal carcinomas and described in an own chapter of the cancer staging manual. Since January 1, 2017, the TNM rules are modified with regard to the nodal status of HPV OSCC – this relevantly influences the tumor stage according to the UICC (Union internationale contre le cancer).

Regarding HPV OSCC, the new edition follows study results of the ICON-S group (International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal Cancer Network for Staging) in Canada, USA, Denmark, and the Netherlands. In this multicenter cohort study, 2,603 patients with known HPV status were included. Nearly all patients received primary RCT (98% of the patients) and more than 70% of the examined patients were HPV-positive 169 . For both groups, the overall survival was analyzed according to previous recursive partition analysis with deduction of a revised staging system for the group of HPV-associated OSCC and HPV-negative OSCC. The proposals of the authors were implemented unchanged in the 8 th edition for patients treated without surgery. Since the applicability is not confirmed for patients who underwent tumor surgery, modified criteria were suggested for those patients. For this purpose, retrospectively assessed results of a surgically treated cohort of 220 American patients were included for whom the presence of 5 or more lymph node metastases was associated with a high risk of tumor recurrence 170 . All patients were p16 positive and underwent transoral surgery; 80% had ECS-positive lymph nodes, this factor was not relevant for prognosis.

Up to now, ECS was considered as indicator for poor prognosis and had a decisive impact on the therapy 171 172 . So the extranodal growth is an indication for adjuvant platinum application during postoperative RT 173 . The exclusion of ECS in the new staging system for HPV OSCC is based – in analogy to the procedure described above – on results of other publications. Retrospective investigations could confirm that the factor ECS is probably not relevant for the outcome of HPV OSCC 174 175 . In addition, the factor ECS is assessed with high interobserver variance 176 . Based on these results, the value of RCT in adjuvant settings of ECS positive HPV OSCC can be doubted 177 . The prospective verification of this assumption is urgently needed because this question is often discussed in tumor boards. Currently 3 prospective studies are conducted that deal with therapy de-escalation including ECS positive HPV OSCC to avoid acute and late toxicity (ECOG 3311, ADEPT, PATHOS, see Table 2 ). Only as a consequence, it will be possible to state if therapy de-escalation is justified despite the presence of ECS in HPV OSCC.

Table 2 Adaptive de-escalation treatment in HPV-positive OSCC.

| Beginning of the study | NCT code | Short name | Phase | HPV diagnosis | Strategy for patients with HPV OSCC | Primary aim of the study | Study title | Recruiting | Ongoing | Completed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | NCT01088802 | 2 | HPV DNA and/or p16INK4A | De-intensification of radiation dose | Comparable therapeutic outcome with lower long-term toxicity | Treatment de-intensification for squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx | X | |||

| 2010 | NCT01084083 | 2 | HPV ISH and/or p16INK4A | Induction chemotherapy, reduction of radiation dose, followed by Cetuximab | Comparable therapy outcome | Induction chemotherapy followed by Cetuximab and radiation in HPV-associated resectable stage III/IV oropharyngeal cancer | X | |||

| 2011 | NCT01302834 | RTOG-1016 | 3 | p16INK4A | Substitution of Cisplatin by Cetuximab in RCT | Comparable therapy outcome | Radiation therapy with Cisplatin or Cetuximab in treating patients with oropharyngeal cancer | X | ||

| NCT01530997 | 2 | HPV DNA and/or p16INK4A | Reduction of chemotherapy and radiation dose, limited neck dissection | Comparable therapy outcome with lower toxicity | Phase-II-study of de-intensification of radiation and chemotherapy for low-risk HPV-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma | X | ||||

| 2012 | NCT01530997 | 2 | HPV DNA and/or p16INK4A | Reduction of chemotherapy and radiation dose | Comparable therapy outcome with lower toxicity | De-intensification of radiation and chemotherapy for low-risk human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma | X | |||

| NCT01687413 | ADEPT | 3 | p16INK4A | Postoperative radiotherapy with and without Cisplatin (in R0 and N>0) | Comparable therapy outcome and toxicity | Post-operative adjuvant therapy de-intensification trial for human papilloavirus-related, p16+ oropharynx cancer | X | |||

| NCT01716195 | 2 | p16INK4A | Induction chemotherapy (Carboplatin/ Paclitaxel), reduction of radiation dose and chemotherapy (Paclitaxel) | Comparable therapy outcome with lower toxicity | Induction chemotherapy followed by chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer | X | ||||

| 2012 | NCT01706939 | Quarterback Trial | 3 | HPV DNA and p16INK4A | Reduction of the radiation dose (56 Gy) with weekly Carboplatin vs. 70 Gy radiation dose and weekly Carboplatin | Comparable therapy outcome with reduced radiation dose | The Quarterback Trial: A randomized phase III clinical trial comparing reduced and standard radiation therapy doses for locally advanced HPV-positive oropharynx cancer | X | ||

| NCT01663259 | HPV DNA and/or p16INK4A | Substitution of Cisplatin by Cetuximab in radiochemotherapy | Comparable therapy outcome with lower toxicity | Reduced intensity therapy for oropharyngeal cancer in non-smoking HPV 16 positive patients | X | |||||

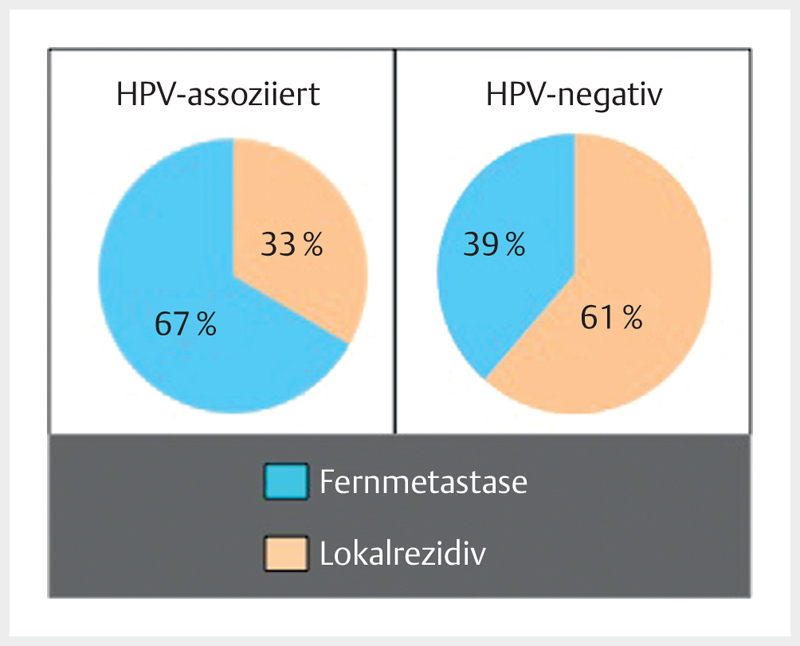

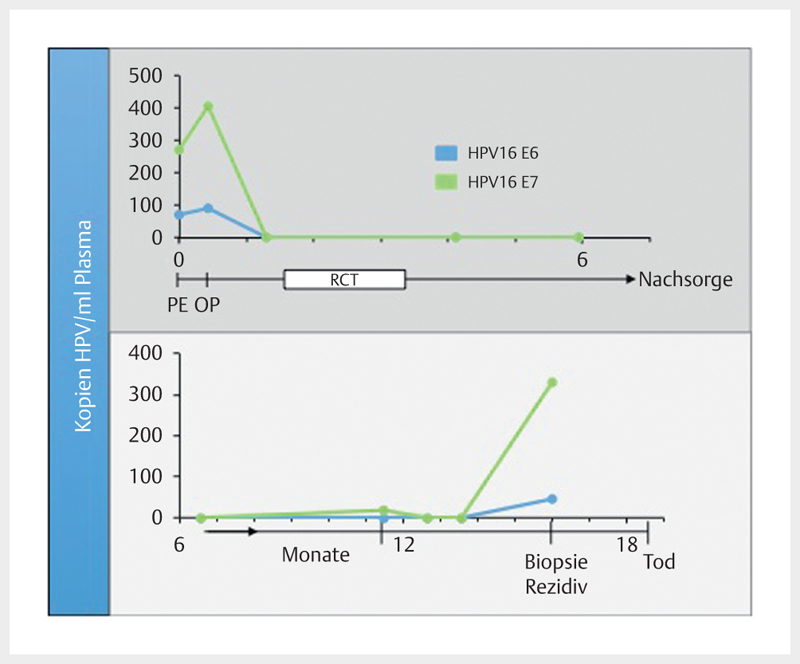

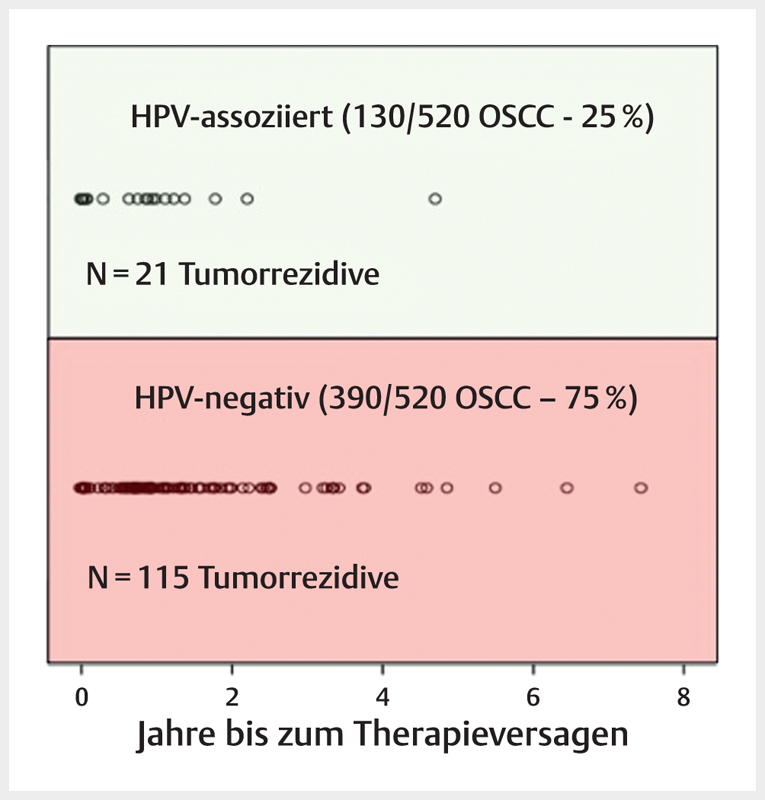

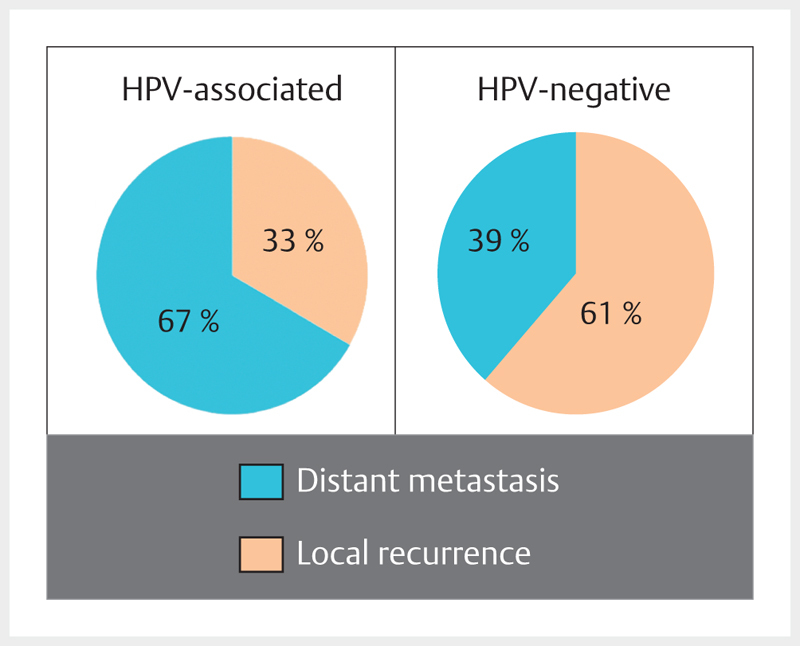

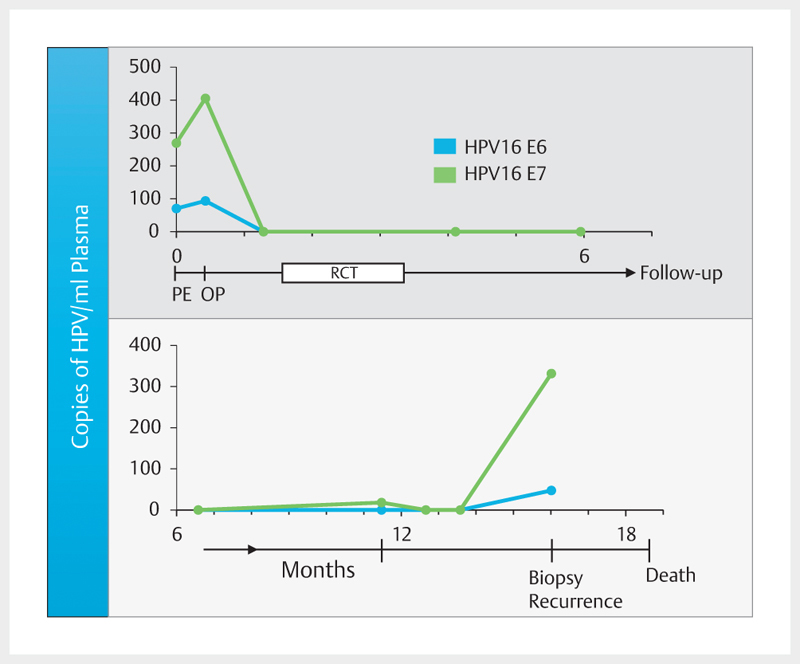

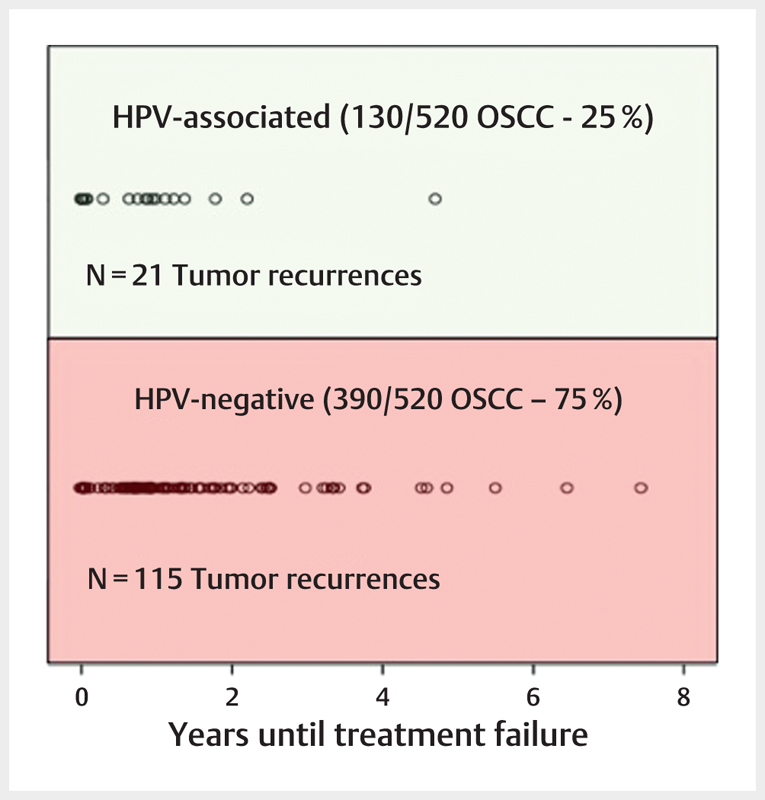

| 2013 | NCT01898494 | ECOG 3311 | 2 | p16INK4A | Reduction of the radiation dose after transoral tumor resection (advanced OSCC) | Comparable therapy outcome | Transoral surgery followed by low-dose or standard-dose radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy in treating patients with HPV positive stage III-IVA oropharyngeal cancer | X | ||