Abstract

Purpose

To improve the care of survivors of head and neck cancer, we developed the Head and Neck Survivorship Tool: Assessment and Recommendations (HN-STAR). HN-STAR is an electronic platform that incorporates patient-reported outcomes into a clinical decision support tool for use at a survivorship visit. Selections in the clinical decision support tool automatically populate a survivorship care plan (SCP). We aimed to refine HN-STAR by eliciting and incorporating feedback on its ease of use and usefulness.

Methods

Human-computer interaction (HCI) experts reviewed HN-STAR using think-aloud testing and the Nielsen Heuristic Checklist. Nurse practitioners (NPs) thought aloud while reviewing the clinical decision support tool and SCP and responded to an interview. Survivors used HN-STAR as part of a routine visit and were interviewed afterward. We analyzed themes from the feedback. We described how we addressed each theme to improve the usability of HN-STAR.

Results

Five HCI experts, 10 NPs, and 10 cancer survivors provided complementary usability insight that we categorized into themes of improvements. For ease of use, themes included technical design considerations to enhance user interface, ease of completion of a self-assessment, streamlining text, disruption of the clinic visit, and threshold for symptoms to appear on the SCP. The theme addressing usefulness was efficiency and comprehensiveness of the clinic visit. For each theme, we report revisions to HN-STAR in response to the feedback.

Conclusion

HCI experts provided key technical design insights into HN-STAR, whereas NPs and survivors provided usability feedback and clinical perspectives. We incorporated the feedback into the preparation for additional testing of HN-STAR. This method can inform and improve the ease of use and usefulness of the survivorship applications.

INTRODUCTION

After cancer treatment is complete, survivors need comprehensive ongoing care to address a complex range of needs: detecting and managing persistent and late-developing toxicities (together called late effects), managing comorbidities, monitoring for recurrence and new cancers, and communicating among providers.1 The provision of survivorship care can be particularly challenging for survivors of head and neck cancer (HNC). Their treatment can cause serious toxicities to the upper aerodigestive tract, which can affect swallowing, speaking, and breathing.2-8 Chronic alcohol and tobacco use, which are prevalent in this population, contribute to long-term comorbidity.5,6,9-13 Survivors also face ongoing risks of recurrent or new cancers.14-16 HNC survivors thus require the coordinated involvement of oncology providers, primary care providers, and other specialists.17

Survivorship care plans (SCPs) are widely promoted as a method to improve care coordination and to enhance the provision of comprehensive survivorship care.18 SCPs are documents that include a treatment summary and a plan for ongoing care.18 However, SCPs are notoriously burdensome for oncology providers to create and deliver.19-23 The burden may be exacerbated for survivors of HNC, who have complicated clinical histories and whose SCPs must address the management of numerous late effects, treatment of comorbidities, modification of multiple risk factors, and surveillance for recurrence.To address these challenges, we sought to develop a user-friendly survivorship platform for HNC.24 The Head and Neck Survivorship Tool: Assessment and Recommendations (HN-STAR) uses an electronic platform to facilitate the identification of all late effects and to enable evidence-based care for survivors of HNC. HN-STAR ultimately produces an SCP for survivors and their providers. Our process for developing HN-STAR focused on making it easy to use and useful for both survivors of HNC and their providers. Optimizing HN-STAR positions us to conduct additional research on its effectiveness in coordinating care and promoting late-effects management.

METHODS

Users’ perceptions of a technology’s ease of use and usefulness influence whether and how they use the technology.25 In developing HN-STAR, we therefore tested key stakeholders’ perceptions of the ease of use and usefulness of both the provider-facing and the survivor-facing components of HN-STAR. We refined HN-STAR in response to end-user feedback.

Description of the Platform

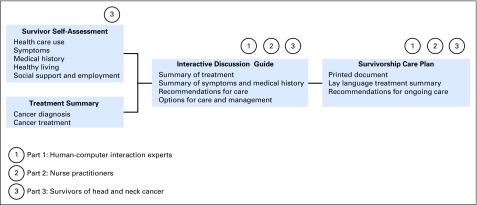

HN-STAR is intended for use by patients who have completed treatment of HNC (survivors) and by their providers, before and during routine clinic visits. HN-STAR consists of four components (Fig 1):

Fig 1.

Components of the Head and Neck Survivorship Tool: Assessment and Recommendations and stakeholder assessments.

(1) HN-STAR generates a Treatment Summary using diagnostic and billing codes. Before the clinic visit, the provider verifies the Treatment Summary against the medical record and corrects any inaccuracies.

(2) Also before the clinic visit, survivors complete the Survivor Self-Assessment, an electronic survey of late effects and health behaviors (Data Supplement). The assessment identifies symptoms using the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events and assesses medical history, preventive health, and behavioral health (eg, depression, alcohol use, and physical activity).26-34

(3) HN-STAR integrates responses from the Survivor Self-Assessment and the Treatment Summary to generate an individualized electronic Clinical Decision Support Tool, which is presented to the provider in clinic to facilitate discussion (Data Supplement). Symptom management composes the bulk of the Clinical Decision Support Tool, with each reported symptom accompanied by diagnoses to consider, recommendations for focused evaluation, and evidence-based management strategies from disease-specific and general medicine literature.7,17,35-55 The Clinical Decision Support Tool prompts the provider and the survivor to discuss each symptom and to agree on management strategies, which could include work-up, referrals, follow-up recommendations, prescriptions, self-management suggestions, or education. The provider enters the selected strategies into HN-STAR. Because not all symptoms merit detailed discussion, the provider can opt not to discuss any symptom.

(4) After the provider completes the Clinical Decision Support Tool, HN-STAR generates an SCP. The SCP consists of a treatment summary and management plans for each symptom and health behavior issue. The survivor and primary care provider each receive a printed SCP. The survivor may share the SCP with the oncologist, other providers, family members, and friends. The provider can save the SCP electronically to import into the electronic health record. By collecting symptom reports directly from survivors, HN-STAR ensures that no relevant symptoms are overlooked and enables access to evidence-based symptom management recommendations. HN-STAR automatically creates an SCP as part of the clinic visit, thereby integrating the use of an SCP into the clinical flow. The SCP presents a lay-language treatment summary and explicitly delineates coordination of care for issues discussed in the visit. By directly incorporating current symptoms, the SCP is personalized to the symptoms and risks that are relevant to each survivor. HN-STAR operates independently of any electronic health record to facilitate scalability across clinics. A detailed description of the protocol is provided elsewhere by Salz and colleagues.24

Usability Evaluation

To optimize HN-STAR for additional effectiveness testing, we elicited feedback on HN-STAR from human-computer interaction (HCI) experts, nurse practitioners (NPs), and survivors of HNC on the Survivor Self-Assessment, the Clinical Decision Support Tool, and the resulting SCP. (Because verification of the Treatment Summary is neither an interactive process nor patient facing, we did not conduct usability testing for this component of HN-STAR.)

HCI Expert Feedback

We invited five HCI experts to assess the two provider-facing components of HN-STAR: the Clinical Decision Support Tool and the SCP. We provided a use case that included a summary of the treatment and symptoms of a mock survivor. Experts were told to use this information to complete the Treatment Checklist and the Clinical Decision Support Tool with minimal instruction. To capture feedback, we used a think-aloud protocol using Morae software (TechSmith, Okemos, MI), which records mouse movements and vocalizations. The HCI experts completed a Usability Checklist derived from Nielsen Heuristics to identify usability issues with the interface.56-58 Ease of use was operationalized in terms of 10 factors, scored from 0 (no usability problem) to 4 (usability catastrophe).

NP Feedback

We engaged NPs from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center to complete a mock visit using HN-STAR’s Clinical Decision Support Tool, with one author (T.S.) playing an HNC survivor . To ensure that HN-STAR would be usable for providers who do not routinely treat survivors of HNC, we limited this study to NPs who had treated survivors of other cancers. The same Clinical Decision Support Tool was generated for each mock clinic visit. Each visit included the usual practice of taking a medical history. The NPs were asked to think aloud while using the Clinical Decision Support Tool and reviewing the resulting SCP. A research assistant interviewed the NPs about the usability of the HN-STAR interface and the feasibility of its use in clinic. All sessions were audio recorded.

Survivor Feedback

We recruited consecutive English-speaking survivors who were ≥ 3 years from treatment and who were scheduled to visit Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center’s HNC survivorship clinic for a routine visit. Before each visit, the survivorship clinic NP (J.M.) verified the Treatment Summary, which populated the Clinical Decision Support Tool. The NP used the Clinical Decision Support Tool on a laptop computer in the clinic. Each participant completed the Survivor Self-Assessment at the clinic and was interviewed immediately regarding that experience. After the visit, the printed SCP was provided to the survivor. Each survivor was interviewed about the visit and the SCP. This study received institutional review board approval. Each survivor provided informed consent.

Analysis

We integrated feedback from HCI experts, NPs, and survivors regarding features and functionality. We calculated descriptive statistics for each of the usability factors for the Nielsen Heuristics Checklist completed by HCI experts. We used the usability factors to code data from HCI experts’ comments on the Nielsen Heuristics Checklist and the NPs’ think-aloud comments. We qualitatively analyzed feedback from survivors and NPs and organized them by theme under the categories of ease of use and usefulness. This approach revealed opportunities for addressing users’ needs and for optimizing HN-STAR for future testing.

RESULTS

Sample

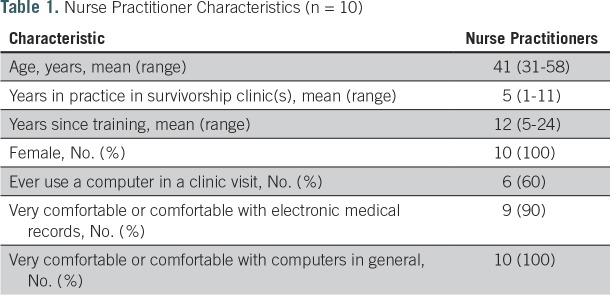

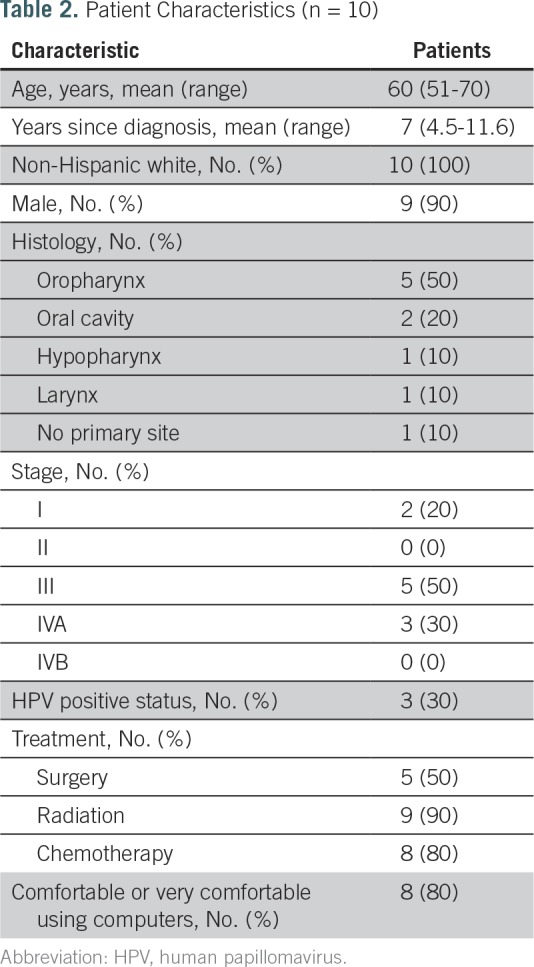

The five HCI informatics experts had completed at least a master’s degree in clinical informatics. The 10 NPs had been in practice in survivorship clinics for 5 years, on average, and all were comfortable or very comfortable with computers (Table 1). The 10 survivors had a range of sites of disease within the head and neck. The average age was 60 years; 90% were male; and 80% were either comfortable or very comfortable with computers (Table 2). Survivors took 22 minutes, on average, to complete the Survivor Self-Assessment. The average duration of clinic visits, which included a physical examination and cancer surveillance in addition to the HN-STAR-guided discussion, was 63 minutes. After 10 mock clinic visits and 10 survivor interviews, we reached thematic saturation.

Table 1.

Nurse Practitioner Characteristics (n = 10)

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (n = 10)

Ease of Use

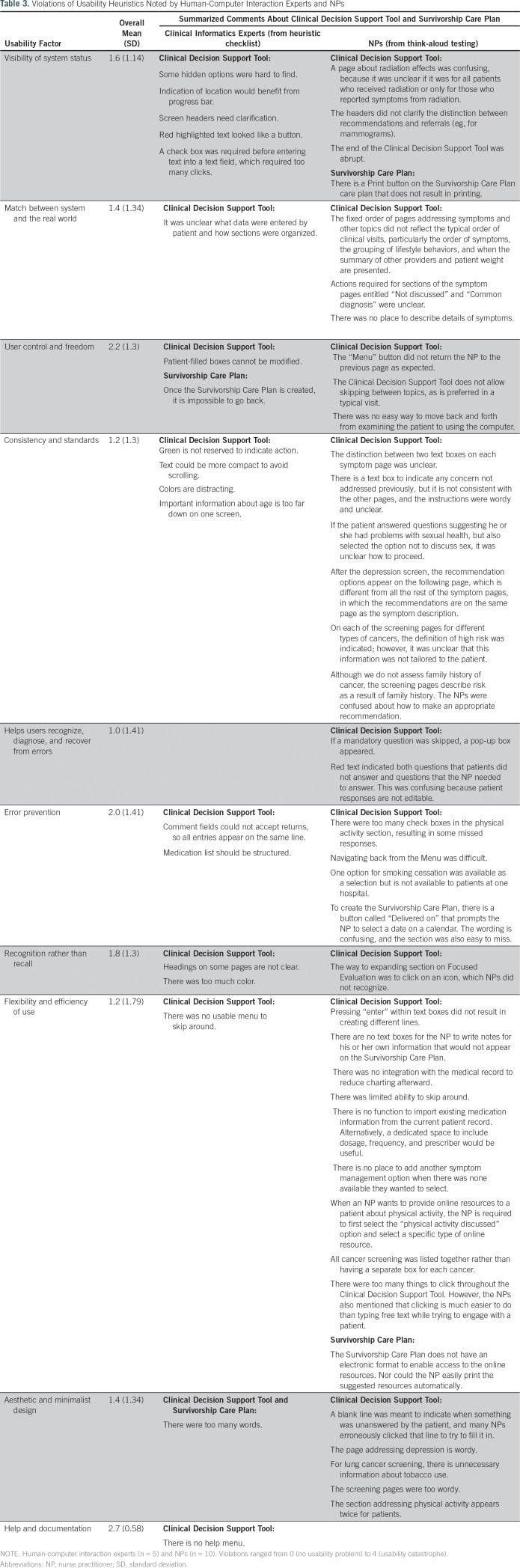

Technical design considerations for user interface.

Table 3 presents usability factor scores and summarized feedback from HCI experts and NPs. HCI experts’ mean ratings on the Nielsen Heuristics Checklist ranged from 1.0 (cosmetic problem only) to 2.7 (between minor and major usability problem). Think-aloud responses from NPs described usability issues across all usability factor categories, with the category of Flexibility and Efficiency of Use containing the greatest number of issues. The HCI experts’ comments on the Heuristic Evaluation Checklist identified opportunities to refine some of the technical aspects of HN-STAR. Both HCI experts and NPs suggested using clearer icons and headers and making fields easier to find. HCI experts offered more technical critiques than did NPs; these included suggesting a more intuitive use of color and a more standard indicator for required fields.NPs provided technical feedback that addressed the clinical context of HN-STAR. For example, NPs wanted text boxes to insert additional details about symptoms.Survivors, in turn, commented on the visual design of the SCP. They suggested improving the plan’s readability, including using less narrative text and using color for emphasis.In response, we altered the design of HN-STAR to better engage and guide users. For example, in the Clinical Decision Support Tool, we reserved the color red for situations in which an alert was needed; we used a green background to indicate sections that users must complete. Asterisks were added to draw attention to required responses, and a menu button was added to facilitate navigation. We made the SCP more readable by increasing the use of bullet points and by adding color.

Table 3.

Violations of Usability Heuristics Noted by Human-Computer Interaction Experts and NPs

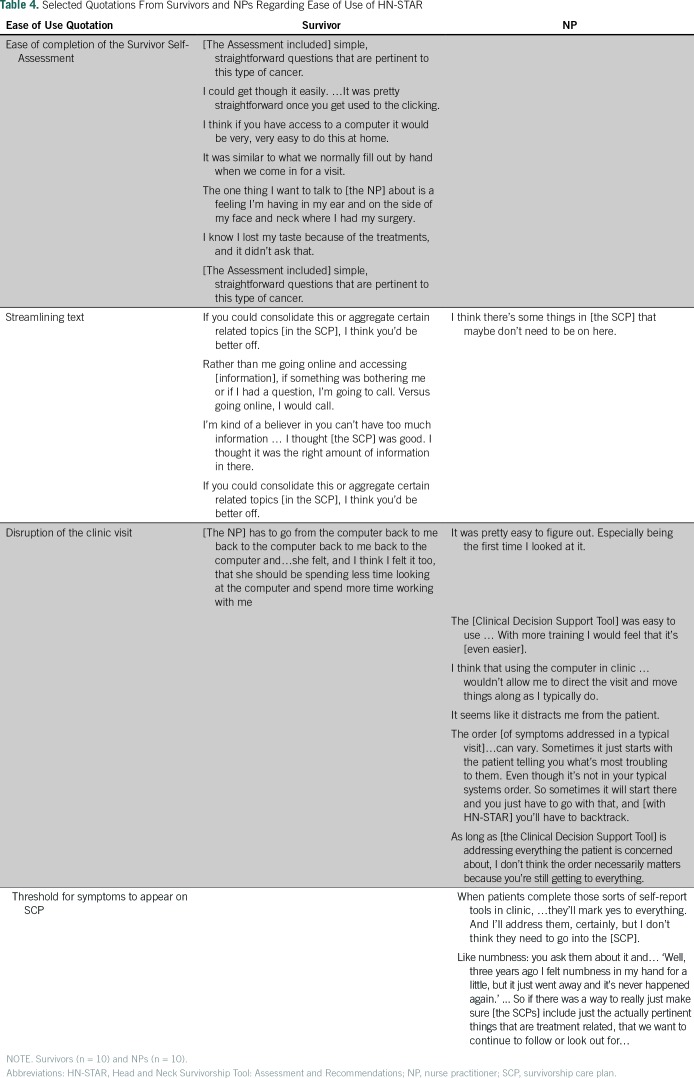

Ease of completion of the Survivor Self-Assessment.

Table 4 presents selected quotes from survivors and NPs illustrating themes regarding the ease of use of HN-STAR. Survivors reported no difficulty in completing the Survivor Self-Assessment. However, they noticed that certain symptoms were not addressed. To fix this, we added an explanation about how survivors can enter information about any remaining symptoms.

Table 4.

Selected Quotations From Survivors and NPs Regarding Ease of Use of HN-STAR

Streamlining text.

HCI experts, NPs, and survivors agreed that text should be limited in various parts of HN-STAR. Specifically, the NPs noted that pages addressing cancer screening in the Clinical Decision Support Tool were unnecessarily long. Similarly, survivors and NPs thought the SCP was too long and they suggested areas to condense.In response, we streamlined the text in the Clinical Decision Support Tool, especially limiting the level of detail in recommendations under the purview of other providers. This change will shorten the Clinical Decision Support Tool and generate more concise SCPs.

Disruption of the clinic visit.

NPs agreed that learning to use the Clinical Decision Support Tool was easy, although some felt that using the computer in clinic was disruptive. Some survivors also disliked NPs shifting attention between the computer and the survivor.The process of displaying each symptom in a predetermined order also disrupted the NPs’ usual practice styles. As NPs proceeded through the mock visits, they were unaware of which symptoms, or how many symptoms, they would be shown.To minimize disruption, we revised the Clinical Decision Support Tool to begin with a summary screen listing all reported symptoms. This alerts the NP to the symptoms that require attention; the symptom list also facilitates a physical examination that addresses each symptom. In addition, the summary screen enables the NP to pace the visit and to ensure that all important issues are covered, particularly if there is a long list of problems.

Threshold for symptoms to appear on SCP.

Every symptom that a survivor reports in the Survivor Self-Assessment appears in the Clinical Decision Support Tool and SCP. However, NPs reported that some symptoms reported by survivors are unrelated to their cancer and should not appear on the SCP, because they distract from more salient treatment-related toxicities.We used this feedback to give NPs more control in addressing symptoms. We added a feature to the Clinical Decision Support Tool to allow NPs to omit unrelated or unimportant symptoms from the resulting SCP. This improvement also reduces the amount of text in the SCP.

Usefulness

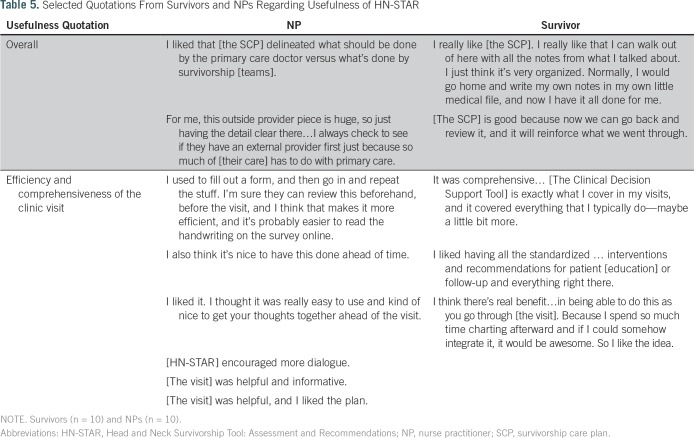

Survivors and NPs offered largely positive feedback about the usefulness of HN-STAR (Table 5). NPs appreciated how the SCP could improve care coordination by including information regarding other providers involved in the survivor’s care. Survivors, in turn, saw the SCP as a helpful record of the visit. Survivors reported that the Survivor Self-Assessment would make visits more efficient by reducing the forms to fill out in advance and by guiding them to think about their needs in preparation for a visit. NPs noted that using the Clinical Decision Support Tool facilitated the conduct of a comprehensive visit. Survivors agreed that the visit was comprehensive and informative. NPs welcomed the potential for the SCP to reduce visit documentation by using electronic symptom reporting and having a summary of actions from the visit in the SCP. However, there were concerns that documentation from HN-STAR would not replace the clinical note required for billing.To reduce duplicative work, we added a free-text field to every screen, in which the NP can type notes that can be cut and pasted into the electronic medical record.

Table 5.

Selected Quotations From Survivors and NPs Regarding Usefulness of HN-STAR

DISCUSSION

The multitude of issues complex cancer survivors experience complicates the provision of survivorship care and SCPs. HN-STAR was designed to facilitate the dissemination of SCPs to improve care coordination and to facilitate late-effects management among HNC survivors. Our goal was to develop a platform that minimized implementation challenges so that we could advance a strong survivorship intervention for additional evaluation. To this end, we assessed ease of use and usefulness from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders. HCI experts brought attention to the technical design aspects of HN-STAR. They found it easy to use overall, and they highlighted usability issues that we were able to address in almost all cases. NPs demonstrated how HN-STAR needed adaptation to function in a clinical setting. Survivors provided feedback on making the computer interface user friendly and on adapting HN-STAR to improve the clinic experience. We incorporated these insights into improvements in HN-STAR, enhancing its ease of use and usefulness for survivors and NPs.

Our study has several limitations. It involved a single refinement of HN-STAR; a more iterative process could involve adapting HN-STAR numerous times in response to feedback.59 By design, HN-STAR functions independently of any electronic health record platform. However, for providers who use an electronic health record in clinic, having a separate computer interface for the Clinical Decision Support Tool may decrease ease of use. We limited participation to English-speaking survivors, and most were comfortable using computers. Furthermore, our edits to HN-STAR were based on NPs and a survivor population in a large cancer center, and we did not elicit usability feedback about the SCP from primary care providers. HN-STAR has the capacity to track symptoms over time; however, we tested usability at a single clinic visit only. Future studies should examine feasibility in multiple survivorship clinics, should include the perspectives of diverse survivors and primary care providers, and should test the usability of longitudinal symptom tracking.

Previous research on SCPs has yielded null results with respect to improving the processes and outcomes of survivorship care.60-64 A critique of existing trials is a lack of reporting on implementation details, and it is therefore unclear whether null findings indicate poor SCP effectiveness or poor clinical implementation of SCPs.65 It is vital to focus on the metrics of ease of use and usefulness during development, to increase the chance of smooth implementation. By integrating systematically elicited insights from multiple end users into a revised version of HN-STAR, we aim to increase uptake of and engagement with HN-STAR in future studies. An improved HN-STAR is more likely to demonstrate improved care coordination and late-effects management.

Although other studies have investigated survivors’ and physicians’ responses to and need for SCPs, to our knowledge, this is the first study to gather systematic stakeholder feedback to inform the early development and implementation of an SCP. Moreover, there has been little work evaluating SCPs for people with HNC, and our study adds to that literature.66,67Our findings suggest that incorporating electronic patient-reported outcomes (and accompanying recommendations) into clinical practice for cancer survivors can benefit from usability and feasibility testing. There is growing evidence that eliciting symptoms from survivors and reporting directly to providers will improve the accuracy of assessment, quality of care, and health outcomes (including survival), but to our knowledge this has never been tested in ongoing cancer survivorship care.26,68-72 Assessing the usability and feasibility of presenting symptom reports with accompanying evidence-based recommendations is critical as health systems move forward with the integration of patient-reported outcomes into clinical practice.

Our usability study identified important end points to consider when testing the feasibility, implementation, and effectiveness of HN-STAR. For example, survivors in our study reported being receptive to entering their health information online at the clinic, but future testing will elucidate to what extent survivors complete this testing at home before their clinic visit. For NPs, feasibility testing must assess whether NPs use the newly added features of the platform to streamline their documentation. The shortened SCP will be assessed in terms of whether it is given to the survivor, whether the NP discusses it in clinic, and whether the survivor finds the information trustworthy and useful. This study to optimize HN-STAR for additional testing is an important first step in improving the care of survivors of complex cancer, where provision of ongoing care and delivery of SCPs can be especially difficult. Usability testing enabled us to shape the content and delivery of HN-STAR in response to expert and end-user feedback, creating a robust clinical platform for additional clinical testing.

Footnotes

Supported by Grant CA187441 (S.B. and T.S.) and P30 Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748 from the National Institutes of Health (Memorial Sloan Kettering).

Presented as a poster at the Biennial Cancer Survivorship Symposium, Washington, DC, June 16-18, 2016 and as an abstract at the ASCO Annual Meeting, Chicago, IL, June 1-5, 2017.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Talya Salz, Rebecca B. Schnall, Mary S. McCabe, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Stacie Corcoran, Andrew Salner, Nirupa Raghunathan, Schrujal Baxi

Financial support: Talya Salz, Shrujal Baxi

Administrative support: Talya Salz, Elizabeth Fortier

Provision of study material or patients: Talya Salz, Andrew L. Salner, Ellen Dornelas, Janet McKiernan

Collection and assembly of data: Talya Salz, Rebecca B. Schnall, Mary S. McCabe, Stacie Corcoran, Ellen Dornelas, Elizabeth Fortier, Janet McKiernan, David J. Finitsis, Shrujal Baxi

Data analysis and interpretation: Talya Salz, Rebecca B. Schnall, Mary S. McCabe, Kevin C. Oeffinger, Andrew J. Vickers, Andrew L. Salner, Ellen Dornelas, Susan Chimonas, Shrujal Baxi

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHOR’S DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwcorascopubs.org/jco/site/ifc.

Talya Salz

No relationship to disclose

Rebecca B. Schnall

No relationship to disclose

Mary S. McCabe

No relationship to disclose

Kevin C. Oeffinger

No relationship to disclose

Stacie Corcoran

No relationship to disclose

Andrew J. Vickers

No relationship to disclose

Andrew Salner

Consulting or Advisory Role: IBM Watson Oncology

Ellen Dornelas

No relationship to disclose

Nirupa Raghunathan

No relationship to disclose

Elizabeth Fortier

No relationship to disclose

Janet McKiernan

Employment: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center

David Finitsis

No relationship to disclose

Susan Chimonas

No relationship to disclose

Schrujal Baxi

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, Merck

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Bristol-Myers Squibb (Inst), AstraZeneca (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: AstraZeneca

REFERENCES

- 1.Nord C, Mykletun A, Thorsen L, et al. Self-reported health and use of health care services in long-term cancer survivors. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:307–316. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ringash J. Quality of life in head and neck cancer: Where we are, and where we are going. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;97:662–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringash J. Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3322–3327. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.61.4115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor JC, Terrell JE, Ronis DL, et al. Disability in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:764–769. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.6.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terrell JE, Ronis DL, Fowler KE, et al. Clinical predictors of quality of life in patients with head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:401–408. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duke RL, Campbell BH, Indresano AT, et al. Dental status and quality of life in long-term head and neck cancer survivors. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:678–683. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161354.28073.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy BA, Gilbert J, Ridner SH. Systemic and global toxicities of head and neck treatment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2007;7:1043–1053. doi: 10.1586/14737140.7.7.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rathod S, Livergant J, Klein J, et al. A systematic review of quality of life in head and neck cancer treated with surgery with or without adjuvant treatment. Oral Oncol. 2015;51:888–900. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell BH, Spinelli K, Marbella AM, et al. Aspiration, weight loss, and quality of life in head and neck cancer survivors. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1100–1103. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.9.1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen AY, Frankowski R, Bishop-Leone J, et al. The development and validation of a dysphagia-specific quality-of-life questionnaire for patients with head and neck cancer: The M. D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:870–876. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwivedi RC, Kazi RA, Agrawal N, et al. Evaluation of speech outcomes following treatment of oral and oropharyngeal cancers. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skoner JM, Andersen PE, Cohen JI, et al. Swallowing function and tracheotomy dependence after combined-modality treatment including free tissue transfer for advanced-stage oropharyngeal cancer. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:1294–1298. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200308000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curi MM, Oliveira dos Santos M, Feher O, et al. Management of extensive osteoradionecrosis of the mandible with radical resection and immediate microvascular reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65:434–438. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2005.12.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris LGT, Sikora AG, Patel SG, et al. Second primary cancers after an index head and neck cancer: Subsite-specific trends in the era of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:739–746. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Argiris A, Brockstein BE, Haraf DJ, et al. Competing causes of death and second primary tumors in patients with locoregionally advanced head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:1956–1962. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper JS, Pajak TF, Rubin P, et al. Second malignancies in patients who have head and neck cancer: Incidence, effect on survival and implications based on the RTOG experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17:449–456. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90094-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pfister DG, Spencer S, Brizel DM, et al. Head and neck cancers, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:847–855, quiz 856. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Institute of Medicine and National Research Council . From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birken SA, Deal AM, Mayer DK, et al. Determinants of survivorship care plan use in US cancer programs. J Cancer Educ. 2014;29:720–727. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0645-7. [Erratum: J Cancer Educ 29:608-610, 2014] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Birken SA, Mayer DK, Weiner BJ. Survivorship care plans: Prevalence and barriers to use. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28:290–296. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0469-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer DK, Nekhlyudov L, Snyder CF, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical expert statement on cancer survivorship care planning. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:345–351. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.001321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salz T, McCabe MS, Onstad EE, et al. Survivorship care plans: Is there buy-in from community oncology providers? Cancer. 2014;120:722–730. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salz T, Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS, et al. Survivorship care plans in research and practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:101–117. doi: 10.3322/caac.20142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salz T, McCabe MS, Oeffinger KC, et al. A head and neck cancer intervention for use in survivorship clinics: A protocol for a feasibility study. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2016;2:23. doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0061-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. Manage Inf Syst Q. 1989;13:319–340. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basch E, Pugh SL, Dueck AC, et al. Feasibility of patient reporting of symptomatic adverse events via the Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) in a chemoradiotherapy cooperative group multicenter clinical trial. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2017;98:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett AV, Dueck AC, Mitchell SA, et al. Mode equivalence and acceptability of tablet computer-, interactive voice response system-, and paper-based administration of the U.S. National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:24. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0426-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA, et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute’s Patient-Reported Outcomes Version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1051–1059. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ewing JA. Detecting alcoholism. The CAGE questionnaire. JAMA. 1984;252:1905–1907. doi: 10.1001/jama.252.14.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Gräfe K. Detecting and monitoring depression with a two-item questionnaire (PHQ-2) J Psychosom Res. 2005;58:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Godin G, Shephard RJ. Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1997;26(suppl 6):S36–S38. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey Questionnaire, in U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (ed). Atlanta, GA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010.

- 34.Bergman B, Aaronson NK, Ahmedzai S, et al. The EORTC QLQ-LC13: A modular supplement to the EORTC Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (QLQ-C30) for use in lung cancer clinical trials. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:635–642. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90535-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:203–239. doi: 10.3322/caac.21343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nekhlyudov L, Lacchetti C, Davis NB, et al. Head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline endorsement of the American Cancer Society guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:1606–1621. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.8478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Buglione M, Cavagnini R, Di Rosario F, et al. Oral toxicity management in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Xerostomia and trismus (Part 2). Literature review and consensus statement. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;102:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Buglione M, Cavagnini R, Di Rosario F, et al. Oral toxicity management in head and neck cancer patients treated with chemotherapy and radiation: Dental pathologies and osteoradionecrosis (Part 1) literature review and consensus statement. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;97:131–142. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.DeVault KR, Castell DO, American College of Gastroenterology Updated guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:190–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Epstein JB, Barasch A. Taste disorders in cancer patients: Pathogenesis, and approach to assessment and management. Oral Oncol. 2010;46:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eubanks JD. Cervical radiculopathy: Nonoperative management of neck pain and radicular symptoms. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ho FY-Y, Chung K-F, Yeung W-F, et al. Self-help cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Sleep Med Rev. 2015;19:17–28. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hojan K, Milecki P. Opportunities for rehabilitation of patients with radiation fibrosis syndrome. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2013;19:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jensen SB, Pedersen AML, Vissink A, et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: Management strategies and economic impact. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1061–1079. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0837-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marinho VCC. Cochrane reviews of randomized trials of fluoride therapies for preventing dental caries. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10:183–191. doi: 10.1007/BF03262681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ogino T, Sugawara M, Minami A, et al. Accessory nerve injury: Conservative or surgical treatment? J Hand Surg [Br] 1991;16:531–536. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(91)90109-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Queiroz MA, Chien HF, Sekeff-Sallem FA, et al. Physical therapy program for cervical dystonia: A study of 20 cases. Funct Neurol. 2012;27:187–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thompson AJ, Jarrett L, Lockley L, et al. Clinical management of spasticity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:459–463. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.035972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McNeely ML, Parliament MB, Seikaly H, et al. Effect of exercise on upper extremity pain and dysfunction in head and neck cancer survivors: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2008;113:214–222. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hutcheson KA, Bhayani MK, Beadle BM, et al. Eat and exercise during radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy for pharyngeal cancers: Use it or lose it. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.4715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hutcheson KA, Lewin JS, Barringer DA, et al. Late dysphagia after radiotherapy-based treatment of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2012;118:5793–5799. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Andersen BL, Rowland JH, Somerfield MR. Screening, assessment, and care of anxiety and depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: An American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline adaptation. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11:133–134. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.LeFevre ML, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:587–593. doi: 10.7326/M14-1796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moyer VA, Preventive Services Task Force Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:210–218. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-3-201308060-00652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Smith RA, Andrews KS, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2017: A review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:100–121. doi: 10.3322/caac.21392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bright TJ, Bakken S, Johnson SB. Heuristic evaluation of eNote: An electronic notes system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:864. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nielsen J, Mack R, editors. Usability Inspection Methods. New York, NY: Wiley; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 58. Techsmith: Usability testing with Morae. https://www.techsmith.com/morae.html.

- 59.Smith KC, Brundage MD, Tolbert E, et al. Engaging stakeholders to improve presentation of patient-reported outcomes data in clinical practice. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:4149–4157. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3240-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Boekhout AH, Maunsell E, Pond GR, et al. A survivorship care plan for breast cancer survivors: Extended results of a randomized clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9:683–691. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0443-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brothers BM, Easley A, Salani R, et al. Do survivorship care plans impact patients’ evaluations of care? A randomized evaluation with gynecologic oncology patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;129:554–558. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Grunfeld E, Julian JA, Pond G, et al. Evaluating survivorship care plans: Results of a randomized clinical trial of patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4755–4762. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hershman DL, Greenlee H, Awad D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based survivorship intervention following adjuvant therapy in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;138:795–806. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2486-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nicolaije KA, Ezendam NP, Vos MC, et al. Impact of an automatically generated cancer survivorship care plan on patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical practice: Longitudinal outcomes of a pragmatic, cluster randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3550–3559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.3399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mayer DK, Birken SA, Chen RC. Avoiding implementation errors in cancer survivorship care plan effectiveness studies. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3528–3530. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.6937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manne S, Hudson SV, Baredes S, et al. Survivorship care experiences, information, and support needs of patients with oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Head Neck. 2016;38:E1935–E1946. doi: 10.1002/hed.24351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hill-Kayser CE, Vachani C, Hampshire MK, et al. Use of Internet-based survivorship care plans by survivors of head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2009;75:S388. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK, Choucair AK, et al. Implementing patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice: A review of the options and considerations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:1305–1314. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-0054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Snyder CF, Aaronson NK. Use of patient-reported outcomes in clinical practice. Lancet. 2009;374:369–370. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61400-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kotronoulas G, Kearney N, Maguire R, et al. What is the value of the routine use of patient-reported outcome measures toward improvement of patient outcomes, processes of care, and health service outcomes in cancer care? A systematic review of controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1480–1501. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wu AW, White SM, Blackford AL, et al. Improving an electronic system for measuring PROs in routine oncology practice. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10:573–582. doi: 10.1007/s11764-015-0503-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall survival results of a trial assessing patient-reported outcomes for symptom monitoring during routine cancer treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–198. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]