Abstract

Visual information influences speech perception both in infants and adults. It is still unknown whether lexical representations are multisensory. To address this question, we exposed 18-month-old infants (n=32) and adults (n=32) to new word-object pairings: participants either heard the acoustic form of the words, or saw the talking face in silence. They were then tested on recognition in the same or the other modality. Both 18-month-old infants and adults learned the lexical mappings when the words were presented auditorily and recognized the mapping at test when the word was presented in either modality, but only adults learned new words in a visual-only presentation. These results suggest developmental changes in the sensory format of lexical representations.

Keywords: audio-visual speech perception, lexical development, word-learning

While we typically think of speech as an acoustic signal, the speech signal is richly multisensory or at least bisensory (for reviews, see Campbell, 2008). Available to the ears and to the eyes, it can be perceived as both a dynamic acoustic and articulatory event. Partly redundant, partly complementary, visible speech has been shown to facilitate auditory phonetic perception. In adults, empirical studies have revealed that visible speech highlights distinctions that are not acoustically salient and can override auditory confusion (Sumby & Pollack, 1954). Studies have also found complementarity in the translation of phonetic information from the visual and auditory domains. Visible information can help disambiguate acoustic information that is easily confusable (i.e., consonant place, vowel roundness), while acoustic information highlights what is easily confused by the eyes (i.e., consonant manner, consonant voicing, vowel height, vowel backness; Miller & Nicely, 1955; Robert-Ribes, Schwartz, Lallouache, & Escudier, 1998).

Basic intersensory binding has been found at birth, albeit in an immature form (for a review: Soto-Faraco, Calabresi, Navarra, Werker, & Lewkowicz, 2012). Infants are able to recognize the correspondence of auditory and visible speech signals along different dimensions (i.e., at 2 to 9 months for vowels: Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1982; Patterson & Werker, 2003; Streri, Coulon, Marie, & Yeung, 2015; at 6 months for consonants: Pons, Lewkowicz, Soto-Faraco, & Sebastián-Gallés, 2009). Infants use this correspondence to identify the language in use and to facilitate phonetic discrimination. For example, 4-month-old infants easily differentiate between their native language and an unfamiliar language just from viewing silently presented articulations (Weikum et al., 2007). At 6 months of age, they successfully perceive a difficult auditory place contrast (e.g., bilabial/ba/versus alveolar/da/synthesized to be acoustically close) only when also shown the consistent visible speech information (e.g., a facial bilabial versus alveolar gesture, Teinonen, Aslin, Alku, & Csibra, 2008).

Yet, little is known about how consistent and appropriate visual input becomes part of, or is accessible from, lexical representations. In adults, visible speech has been found to facilitate the processing of nonsense forms (i.e., Ostrand, Blumstein, & Morgan, 2011; Samuel & Lieblich, 2014) and initiate lexical access, either in conjunction with auditory information (Barutchu, Crewther, Kiely, Murphy, & Crewther, 2008; Brancazio, 2004; Buchwald, Winters, & Pisoni, 2009; Fort, Spinelli, Savariaux, & Kandel, 2010), or on the basis of the visual modality exclusively (Fort et al., 2013; Mattys, Bernstein, & Auer, 2002). For instance, when simultaneously presented with a familiar word in the visual modality (e.g., seen ‘desk’) and a phonetically similar pseudo-word in the auditory modality (e.g., heard ‘besk’), adults typically interpret the input to the advantage of the visual modality (e.g., seen ‘desk’). When presented with a familiar word in the auditory modality (e.g., heard ‘beg’) combined with a pseudo-word (e.g., seen ‘deg’) in the visual modality, adults typically interpret the input in favor of the auditory modality (e.g., heard ‘beg’, Brancazio, 2004). These findings, of a lexical superiority effect in both modalities, provide evidence that visible and auditory speech information together exert a strong influence in the activation of lexical representations.

Still unclear, however, is the contribution of visible speech in early lexical representations. Given the tight relationship between auditory and visible speech information, infants should be able to use the visual input to identify and access word forms. However, converging evidence suggests that the use of visible speech is susceptible to developmental changes and that visible speech information may not be represented initially at the lexical level.

First, young infants do not consistently integrate visible and audible speech in phonetic perception tasks. While some ERP studies reveal some neural evidence for audio-visual matching in infants as young as 2 months (Bristow et al., 2009), other ERP studies indicate individual differences in performance between 6 to 8 months of age (Kushnerenko et al., 2013; Nath, Fava, & Beauchamp, 2011). Similarly, behavioral studies with infants reveal visual influences on auditory speech perception in some (Burnham & Dodd, 2004), but not other (Desjardins & Werker, 2004) tasks. But the influence of visible speech on auditory phonetic perception clearly increases over childhood (i.e., preschool-aged children: McGurk & MacDonald, 1976; Sekiyama & Burnham, 2008; 6- to 11-year-old children: Baart, Bortfield, & Vroomen, 2015; Maidment, Kang, Stewart, & Amitay, 2014).

Second, in the few studies that have explored the use of visible speech at the lexical level in children, results appear to be unclear. Studies with 4-year-old children have found that visible speech can facilitate word recognition (picture naming, word repetition), when the auditory signal is intact (Jerger, Damian, Spence, Tye-Murray, & Abdi, 2009) or partly degraded (Lalonde & Holt, 2015). However, further studies document that children do not consistently get a lexical boost from the visual input (Fort, Spinelli, Savariaux, & Kandel, 2012; Jerger, Damian, Tye-Murray, & Abdi, 2014). For example, Jerger et al. (2014) found that 4-year-old children were able to use visible speech to restore the excised onset (e.g., /b/) of pseudo-words presented auditorily (e.g., ‘beece’) but had difficulty doing so with words (e.g., ‘bean’). Yet, at 14 years, the visible speech fill-in effect was larger for pseudo-words than words. Along with this work, Fort et al. found that 6-to-10-year-old children and adults were able to identify whether a target phoneme (e.g., /o/) was present in a word (e.g., in French ‘bateau’), or a pseudo-word (e.g., ‘lateau’), when presented in an audio-visual or in an auditory-only modality with white noise in the acoustic signal (Fort et al., 2010, for adults; Fort et al., 2012, for children and adults). Identification performance was higher in the audio-visual than in the auditory modality, and overall higher for words than pseudo-words (lexical superiority effect). While adults demonstrated a higher lexical superiority effect in the audio-visual modality than in the auditory modality, children did not show such a difference. This was interpreted as evidence that in late childhood, visible speech might spread activation to pre-lexical units (sounds, sound combinations, pseudo-words with no associated meaning) more than to lexical units (word forms with meaning, Fort et al., 2012).

Yet, task demands account for a large part of the observed variability and in the studies reported so far, children were tested using procedures requiring overt responses, tasks primarily designed for adults (Jerger et al., 2014). As argued in the literature, word recognition is susceptible to task demands which are often greater in younger age groups (Jerger et al., 2014; Yoshida, Fennell, Swingley, & Werker, 2009). It is thus unclear whether visible speech contributes to early lexical representations.

The influence of visible speech has never been explored within a word-learning context, which raises the question of whether visible speech information is included in lexical representations as they become established. It is well known that by 12 to 14 months, infants can learn new words in the auditory modality and can link novel phonetically distinct words with novel objects following limited exposure in a laboratory setting (MacKenzie, Graham, & Curtin, 2011; Werker, Cohen, Lloyd, Casasola, Stager, 1998). Still unknown is whether words learned in the auditory modality have a representational format that contains, or is accessible from, visible speech information, and whether learning can occur solely on the basis of visible speech information.

The present study is the first to examine the use of auditory and visible speech information during the formation of new lexical representations. The purpose of the present study is twofold: 1) to determine whether 18-month-old infants are able to learn and recognize word-referent mappings using visible speech information and, if so, whether performance is similar to that observed in the auditory modality, and 2) whether lexical representations are bisensory and enable recognition from the other sensory modality specifying the same word, even when the word has never been experienced in this other modality when learning word-referent mappings (for example, from the visual mode if learning is in the auditory mode, from the auditory if learning is in the visual mode). In the present study, word learning is evaluated in 18-month-old infants (Experiment 1) with a standard word-learning task (Havy et al., 2014; Yoshida, Fennell, Swingley, & Werker, 2009) consisting of the presentation of two novel objects each paired with one of two different novel words (for example, object 1 - /kaj/ and object 2 - /ruw/). At test, the task is to identify which of the two objects presented simultaneously is being named. The presentation of the word during learning and during the lexical recognition task is manipulated to test two ‘same modality’ and two ‘cross-modality’ conditions. In the ‘same modality’ conditions, participants learn the words in one modality and are tested in the same modality (either auditory, i.e., acoustic presentation of the word, or visual, i.e., model articulating the word in silence). In the ‘cross-modality’ conditions, participants learn the words in one modality (either auditory or visual) and are tested in the other modality (visual if learning was in the auditory mode, auditory if learning was in the visual mode). If learning modality matters, we should observe differences in word-learning performance after an auditory versus a visual learning experience. If lexical representations are bisensory, recognition should be possible in one or both cross-modal conditions. To ascertain the overall sensitivity of the task, a group of adults is tested (Experiment 2) in a similar paradigm. Given the literature on audio-visual speech perception in adults (Barutchu et al., 2008; Brancazio, 2004; Buchwald et al., 2009; Fort et al., 2010; 2013; Mattys et al., 2002) and adults’ capacity to learn new auditory word forms in a similar paradigm (Havy, Serres, & Nazzi, 2014), we expect adults to reliably use visible speech during word learning.

Experiment 1.

Method

Participants

Thirty-two infants from monolingual English-speaking families participated in this experiment at the University of xxx. An additional 18 infants were tested but their data were not included due to fussiness/crying (n = 9), calibration issues (n = 6) or technical problems with data recording (n = 3). Sixteen infants (8 males, 8 females; M = 18 months, 5 days, range: 17 months, 11 days – 18 months, 14 days) formed the auditory learning group. Another sixteen infants (9 males, 7 females; M = 17 months, 22 days; range: 17 months, 6 days – 18 months, 9 days) formed the visual learning group. No statistical differences were found for production vocabulary size (MacArthur-Bates Short Form Vocabulary Checklist: Level II Form A) between the auditory learning group (M = 24 words, SD = 18) and the visual learning group (M = 27 words, SD = 17), t < 1. For both groups, lexical recognition was tested across the following two conditions: 1) ‘same modality’, in which testing was done in the same modality as the one used in the learning process and, 2) ‘cross-modality’, in which testing was done in a different modality than the one used during learning.

Stimuli

Speech stimuli

The speech stimuli consisted of four pairs of novel English-sounding words with a CVG (consonant – vowel – glide) structure: /ka/-/ruw/, /gow/-/fij/, /vuw/-/tej/, /pow/-/rij/. The phonetic distance of these pseudo-words was tightly controlled to ensure high contrast in both the auditory and visual modalities between words within each pair. The phonetic distinctions involved a contrast of several features on each segment of the CVG words: the manner, place and voicing for the consonant (considered to be the most informative at the lexical level, Nespor et al., 2003), the backness, height and roundness for the vowel, and the place and roundness for the glide. Each contrast was included on the basis of phoneme confusability matrices and is reliably discriminable in the auditory and visual modes by adults (Binnie, Montgomery, & Jackson, 1974; Jackson, Montgomery, & Binnie, 1976) and infants (Desjardins & Werker, 2004; Kuhl & Meltzoff, 1982; Patterson & Werker, 2003; Pons et al., 2009; Tsuji & Cristia, 2014; Werker & Curtin, 2005). Due to the limited number of vowel contrasts affording maximal distinctiveness in both auditory and visual modalities, the vowel contrast /o/-/i/was used twice.

The pseudo-words were produced by a native English-speaking female in a tightly controlled frame, /ha/ + pseudo-word, in order to maintain consistent word durations (M = 1250 ms, SD = 52 ms, range = 1150–1275 ms). This frame was used during all presentations of each word in all phases of the experiment so as to ensure that infants begin attending to the speech information prior to the onset of the word of interest in both auditory and visual conditions and are therefore likely to process the initial information in the words. This frame was particularly important in the visual condition as the visible speech information is often available before the auditory speech information and sometimes before infants engage in selective attention. Six exemplars of each pseudo-word were recorded in order to highlight the relevant differences between pseudo-words (Rost & McMurray, 2009).

Speech stimuli were video-recorded with an AK-HC 1500G Panasonic professional highdefinition video-camera at approximately 60 frames per second and used to create three media sequences: an audio-visual sequence, an auditory sequence (acoustic presentation of the word with the video stream removed) and a visual sequence (model articulating the word with the sound stream removed). Mean video length was 2450 ms (SD = 52 ms, range = 2250–2475 ms), including 600 ms of silent black display before the onset of the articulatory gesture and again after the end of the word. Auditory stimuli were edited to ensure similar sound pressure levels across stimuli (60 dB).

Object stimuli

Four pairs of novel objects were created (using Photoshop and Final Cut Pro). Within each pair, the two objects differed by color and shape and were easily discriminable. In order to facilitate interest and learning, each object was animated to rotate along its vertical axis. The size of each object on screen was approximately 407 (horizontal) × 315 (vertical) mm.

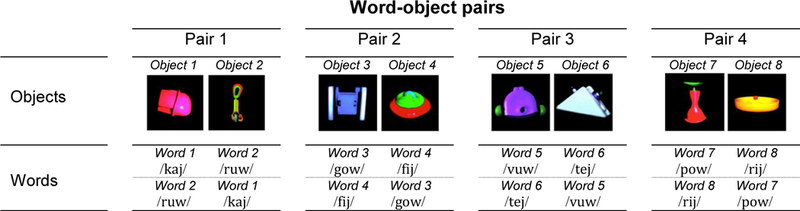

Each pair of objects was randomly assigned to a unique pair of pseudo-words (see Figure 1) (e.g., pair 1: objects 1 and 2 with words 1 and 2; pair 2: objects 3 and 4 with words 3 and 4; pair 3: objects 5 and 6 with words 5 and 6; pair 4: objects 7 and 8 with words 7 and 8).

Figure 1.

The four word-object pairs used. For each pair, the word-object association is counterbalanced across all participants.

Apparatus

The monitor on which the stimuli were presented was a 46-inch LCD NEC TV with a resolution of 1024 × 768 pixels per inch and a refresh-rate of 60 Hz. The eye-tracker was a stand-alone corneal-reflection Tobii 1750 (Tobii Technology, Stockholm, Sweden) using a sampling rate of 60 Hz. PsyScope was used for presentation of the stimuli. Tobii Studio Analysis software was used for storing the eye tracking data, and determining looking behavior.

Procedure

Participants were tested individually in a dimly lit sound-attenuated laboratory suite at the University of xxx. During the study session, infants were seated on their parents’ laps at a viewing distance of 60 cm from the monitor and eye-tracker. In order to prevent parental influence on infant behavior, parents wore opaque glasses and were instructed not to speak or point during the experiment.

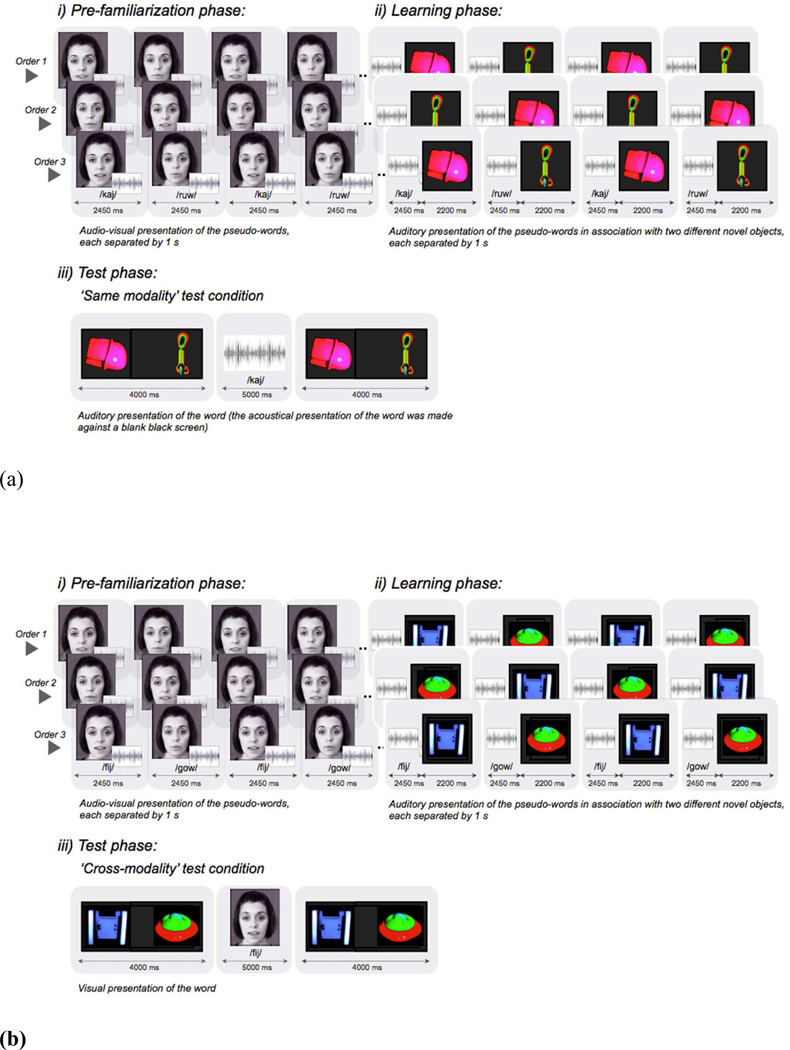

The procedure began with a 5-point calibration in which a bouncing ball appeared at the four corners and in the center of the monitor in a series of individual events. After calibration, all participants heard and saw all eight pseudo-words and all eight novel objects described above. Each participant had the opportunity to learn four word-object pairings across four different trials. For each trial, two word-object pairings were presented in the following order: a pre-familiarization phase, a learning phase and a test phase (see Figure 2). For each trial, pre-familiarization and learning phases formed one sequence that was repeated three times, each time with variations in the order of word and word-object presentations. A test phase immediately followed the sequence of pre-familiarization and learning phases. The end of each test phase marked the end of each trial.

Figure 2.

This figure illustrates the auditory word-learning condition. Phases (i) and (ii) are each presented three times before the test phase (iii). In the ‘same modality’ test conditions, each infant received two objects labeled in the same modality as training (a). In the ‘cross-modality’ test conditions, the two objects were labeled in the other modality (b). The waveforms representing the sounds heard, and the text depicting pseudo-words, are included for illustration only.

During the pre-familiarization phase, the participant was introduced to two words in the audio-visual modality (i.e., they heard and saw the model speak the word). This pre-familiarization phase was intended to provide an implicit reminder for all participants across all conditions that speech is both audible and visible, and to facilitate word learning.

For the learning phase, the same two words introduced in the pre-familiarization phase were presented in association with two novel objects. One group received the words in the auditory modality (hear the word and see a black screen) and the other group received the words in the visual modality (see the model articulating the word without hearing the auditory signal). The objects appeared at the center of the screen for 2200 ms. The presentation of the word immediately preceded the presentation of the object to which it was assigned. The sequential presentation of the word first and then the object was meant to ensure initial interest in the objects remained similar across both the auditory and the visual learning conditions. Indeed, infants of the same age display equal attention to familiar objects which are preceded by their auditory name or corresponding iconic gesture (involving hand or facial movements, e.g., opening and closing the mouth to represent a fish) (Sheehan, Namy, & Mills, 2007; Suanda, Walton, Broesch, Kolkin, & Namy, 2013). The sequential word object presentation used in the present study was also expected to prevent interference and facilitate word-object associative learning (Althaus & Plunkett, 2015). There was a delay of one second between the presentations of each word-object pairing. During both the pre-familiarization and the learning phase, words appeared twice in alternation. Because there were three repetitions of each of these phases, participants experienced each word twelve times, six times in a multimodal format (audio-visual presentation of the word) with no object present and six times in a unimodal format (either auditory or visual presentation of the word) in association with an object, prior to entering the test phase.

During the test phase, participants viewed the same objects as those presented during the learning phase. The object pairs first appeared simultaneously on the screen in silence during a pre-naming period. The pre-naming period lasted 4 seconds so as to give infants enough time to look at both objects (White & Morgan, 2008). The objects then disappeared for 5 seconds during which time one of the objects was labeled twice, using two of the exemplars from the pre-familiarization and learning phases. Depending on the condition for each test trial, words were presented either in their auditory form against a black screen or in their visual form in silence. Next, the objects reappeared, each on the same side of the screen as shown previously, during a post-naming period for an additional 4 seconds in silence. Pre-naming and post-naming periods captured visual preferences before and after the object was labeled, respectively.

Two types of test conditions were created in order to test lexical recognition in different modalities. The ‘same modality’ test condition tested word recognition within the same modality as the one used in the learning process (auditory if learning was in the auditory mode, visual if learning was in the visual mode). The ‘cross-modality’ test condition tested word recognition in the other modality (visual if learning was in the auditory mode, auditory if learning was in the visual mode). All participants received two ‘same modality’ and two ‘cross-modality’ test trials, each with different object pairs. Specifically, two of the four word-object pairs were used for two ‘same modality’ test trials and the remaining two word-object pairs were used for two ‘cross-modality’ test trials.

Across the participants, sixteen protocols were tested. The specific word-object pairs used for ‘same modality’ versus ‘cross-modality’ test trials, as well as the order (1st to 4th position) of test trials (‘same modality’ and ‘cross-modality’) were counterbalanced. Word-object pairings (half of the protocols: word 1-object 1, word 2-object 2, other half: word 2-object 1, word 1-object 2, see Figure 1), and the side (left versus right side of the screen) of object appearance at test (half of the protocols: object 1: left – object 2: right, other half: object 1: right – object 2: left) were also balanced. Objects served equally often as the target and as the distractor with the constraint of no more than two targets on the same side within the same protocol.

Before each protocol and between each of the four study trials, animated cartoons were displayed in order to maintain infants’ interest. Cartoons consisted of colorful bears and monkeys moving across the screen and were accompanied by non-speech sounds. The procedure lasted approximately 15–17 minutes in total.

Measures

Eye-tracking data consisted of an average of overall gaze fixation, using only those times when both eyes could be simultaneously tracked. Data were analyzed with respect to two areas of interest, defined by dividing the screen into two equal parts - one corresponding to the side with the target and the other with the distractor. Based on a measure commonly used in 2-choice word-learning and word recognition tasks (Havy et al., 2014; Mani & Plunkett, 2007; Swingley & Aslin, 2000), we considered the percentage of target looking time, that is, the amount of time spent looking at the target object (T) divided by the amount of time spent looking at the target object plus the distractor (T+D). Labeling effects were evaluated by comparing data from pre- and post-naming periods for each trial; this yielded up to 8 data points per infant. Comparison was performed on the entire 4 seconds of each period so as to give enough time for lexical recognition, especially because some information of newly learned words needs more than 2 seconds to be processed (e.g., vowels, Havy, Serres, & Nazzi, 2014). To ensure that this minimum was met, trials in which infants did not look at the monitor for more than 50% during the pre-familiarization and learning phases (auditory learning: 5/64 trials; visual learning: 4/64 trials) were excluded from the analyses. On the remaining trials, trials in which infants did not look at both objects at test during the pre-naming period (auditory learning: 2/64 trials; visual learning: 5/64 trials) or did not look at the monitor during the post-naming period (auditory learning: 2/64 trials; visual learning: 3/64 trials) were excluded from the analyses. Visual-test trials in which infants did not look at the model during the visual-only naming period, were also excluded (auditory learning: 1/32 trials; visual learning: 5/32 trials): these were actually some of the same trials in which infants did not look at the object or monitor during pre- and post-naming periods respectively.

Predictions

It was expected that if infants linked the word with the object, they would look to the named object during the post-naming period of the test phase.

Results

To assess the contribution of learning and test conditions to infants’ performance, we ran a linear mixed effects model, using the percentage of target looking time per trial and per child as the dependent measure. Data were log transformed to reduce skewness at the extremes of the distribution (DeCoster, 2001). As fixed effects, we entered the learning groups (auditory versus visual), test conditions (‘same modality’ versus ‘cross-modality’) and test periods (pre-naming versus post-naming) as well as all interactions between these factors. As random effects, we entered effects of participants and items on intercepts and effects of participants on the slopes of the test condition and test period effects. Random effects on intercepts and slopes were included so as to control for Type I error rate (Barr, Levy, Scheepers, & Tily, 2013). To estimate goodness of fit, we performed pairwise model comparisons with (full model) vs. without the effect of interest where the model without the effect of interest included all other effects. Models were fitted using maximum likelihood estimation and comparisons were made using −2 log -likelihood ratio tests (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008; Jaeger, 2008). These analyses yield Chi-squared statistics (χ2(df) = x, p = z) as indicators of main effects and interactions, where χ2 values correspond to the difference in the −2 log-likelihood values of the two models and df values correspond to the difference in the number of parameters. T-tests were also performed to evaluate mean proportions of looking times (averaged over the trials of each condition) against chance (set at 50% since each response involved a choice between two equally probable possibilities).

The analysis revealed that the inclusion of labeling and learning effects as well as the interaction between these effects was warranted by a significant improvement in model fit to data: labeling, χ2(4, N = 32) = 9.27, p = .05; learning, χ2(4, N = 32) = 10.21, p = .04; learning x labeling, χ2(2, N = 32) = 5.93, p = .05. There was a reliable increase of target looking preference after the presentation of the word in the auditory learning group only: auditory, χ2(1, N = 16) = 6.41, p = .01; visual, χ2 < 1. Inclusion of all other fixed and random effects did not yield any significant improvement in model fit, suggesting that little of the individual variance remained to be explained (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Table showing the results of a maximum likelihood estimated model predicting infants’ performance. Parameter estimates include the mean performance (Mean) in the different conditions, the estimated coefficient (Estimate) of the fixed effects, the Variance of random effects and Chi-square statistics (χ2). Chi-square statistics are associated with pairwise model comparisons with (full model) versus without the effect of interest. Planned comparisons test naming effects (test period: pre-naming versus post-naming) in each learning (auditory versus visual) and test (same modality versus cross-modality) condition.

| Parameters | Parameters estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | ||

| FIXED EFFECTS | ||||

| Main effects and interactions | ||||

| Learning | – | 07.02 (04.95) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 10.21, p = .04 | |

| Test condition | – | −01.93 (03.90) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 04.66, p = .32 | |

| Test period | – | 06.01 (03.66) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 09.27, p = .05 | |

| Test period* learning | – | 13.12 (07.22) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 05.93, p = .05 | |

| Test period* test condition | – | −10.84 (06.04) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 03.67, p = .16 | |

| Test period* learning* test condition | – | 00.33 (14.36) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Variance(SD) | Chi-square statistics | |||

| RANDOM EFFECTS | ||||

| Subjects on intercepts | – | 00.88 (00.47) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Items on intercepts | – | 00.01 (00.01) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Subjects on the slope of the test condition | – | 00.92 (00.59) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Subjects on the slope of the test period | – | 00.69 (00.51) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Mean (SD) | Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | ||

| PLANNED COMPARISONS | ||||

| Auditory | ||||

| Overall | Pre-naming | 52.28 (12.16) | 12.54 (04.38) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 06.41, p =.01 |

| Post-naming | 64.85 (14.51) | |||

| Same modality | Pre-naming | 51.02 (23.49) | 18.55 (06.71) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 06.14, p =.01 |

| Post-naming | 68.93 (23.08) | |||

| Cross-modality | Pre-naming | 53.64 (14.08) | 07.08 (03.10) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 05.16, p =.02 |

| Post-naming | 60.78 (20.58) | |||

| Visual | ||||

| Overall | Pre-naming | 51.14 (16.96) | −00.44 (06.09) | χ2 < 1 |

| Post-naming | 50.58 (19.11) | |||

| Same modality | Pre-naming | 49.13 (28.19) | 04.95 (05.69) | χ2 < 1 |

| Post-naming | 54.07 (30.80) | |||

| Cross-modality | Pre-naming | 53.14 (25.89) | −06.03 (06.99) | χ2 < 1 |

| Post-naming | 47.09 (24.82) | |||

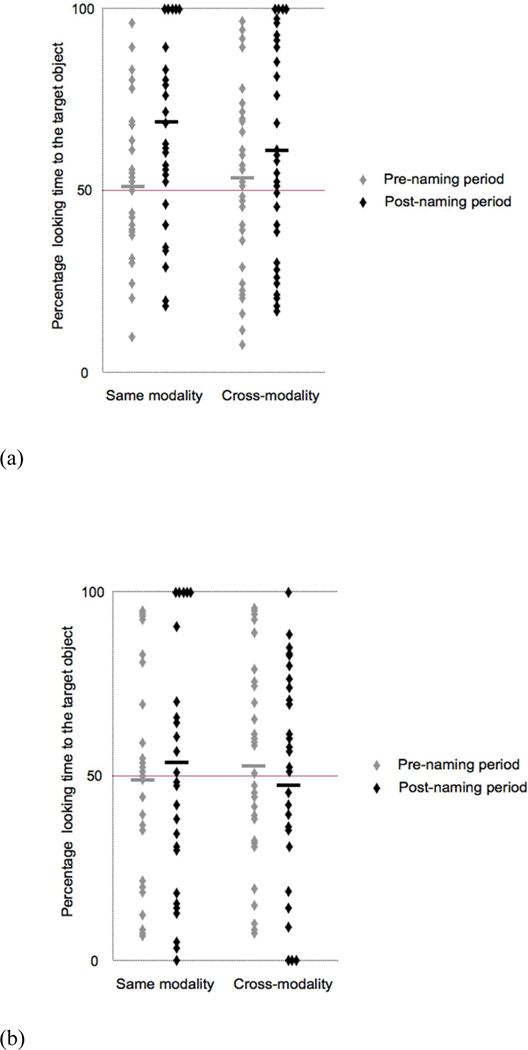

Overall, infants in the auditory learning group spent 52.28% (SD = 12.16%), t < 1, and 64.85% (SD = 14.51%), t(15) = 4.49, p < .01, d = 2.32, of their time looking at the target object before and after naming, respectively, with similar labeling effects in the ‘same modality’: pre-naming (M = 51.02%, SD = 23.49%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 68.93%, SD = 23.08%), t(15) = 3.42, p < .01, d = 1.77; and ‘cross-modality’ conditions: pre-naming (M = 53.54%, SD = 14.08%), t(15) = 1.20, p = .25, d = .62; post-naming (M = 60.78%, SD = 20.59%), t(15) = 2.24, p = .04, d = 1.16, (see Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Mean percentages of looking times at test in 18-month-old infants. Each data point represents individual data for (a) the auditory learning group and (b) the visual learning group in the pre-naming and post-naming periods of the two ‘same modality’ and the two ‘cross-modality’ test trials. Each participant contributes to eight data points: two for the pre-naming and two for the post-naming period of the ‘same modality’ test trials and two for the pre-naming and two for the post-naming period for the ‘cross modality’ test trials. The bold horizontal lines represent mean performance in each condition.

Infants in the visual learning group spent 51.14% (SD = 16.96%), t < 1, and 50.58% (SD = 19.11%), t < 1, of their time looking at the target object before and after naming, respectively, which was at chance in both cases. This pattern was the same for both ‘same modality’: pre-naming (M = 49.13%, SD = 28.19%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 54.07%, SD = 30.80%), t < 1; and ‘cross-modality’ conditions: pre-naming (M = 53.14%, SD = 25.89%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 47.09%, SD = 24.82%), t < 1, (see Figure 3b).

Altogether, this pattern of results indicates that infants were able to learn the words more easily in the auditory modality than in the visual modality. It also shows that after auditory learning, infants successfully recognized the named object regardless of the modality of testing (auditory versus visual). Lexical recognition is thus not constrained to the modality of testing when learning occurs in the auditory mode.

Discussion

The dual purposes of Experiment 1 were to evaluate 18-month-old infants’ capacity to leam new words based on either acoustic or visible speech information, and to determine whether infants show lexical recognition in a modality different from the one serving the learning process (auditory versus visual).

The pattern of results indicates that 18-month-olds are able to quickly learn new words based on auditory information. These results are consistent with previous research (for a review, Werker & Curtin, 2005). Moreover, the present results show that after auditory learning, infants of this age successfully recognize the object named at test even when paired with the presentation of the word in the visual-only modality, i.e., with a silent talking face producing the word. This indicates that words learned in the auditory modality have a representational format that is not specified exclusively by the modality of learning but instead includes sufficient information to support lexical recognition in the visual modality as well.

In sharp contrast, infants receiving training in the visual modality had difficulty identifying the named object at test, and performed at chance. This pattern of difficulty was observed both when lexical recognition was tested in the visual modality (the same modality as the one serving the learning process) and when tested in the auditory modality. Thus, while infants showed cross-sensory recognition of the word form that was paired with the object when the word was learned auditorily, they did not do so when the word was first presented visually.

Experiment 2.

We know that adults have better audio-visual speech perception capacities than infants. For example, visual information has been shown to boost lexical access of known words in many studies that have examined any aspect of audio-visual processing of lexical items in adults (Barutchu, et al., 2008; Brancazio, 2004; Buchwald et al., 2009; Fort et al., 2010). In a recent study, children failed to show a boost in lexical access with the presentation of visual information (Fort et al., 2012). Here, we test adults in the present paradigm so that we can ascertain the nature of the differences between infant and adult performance in the task. Since visual information does facilitate lexical access for adults (Fort et al., 2010), we expect adults to learn novel words based on visible speech information in our task.

Method

Participants

Forty-four English-speaking students from the University of xxx participated in the study. Twelve adults were excluded from the analysis, due to difficulty with calibration in the eye-tracker (n = 2), technical issues with data recording (n = 3), technical issues with the loudspeaker (n = 1) or vision problems requiring strong correction (n = 6). Sixteen adults (5 males and 11 females; M = 22 years, range = 18–24 years) formed the auditory learning group and another sixteen adults (6 males, 10 females; M = 21 years, range = 18–22 years) formed the visual learning group. As in Experiment 1, in both groups’ lexical recognition was tested both in the same modality as the one serving the learning process and in the other modality.

Stimuli, procedure and measures

The stimuli, procedure and measures were the same as described in Experiment 1. Participants did not receive any particular instruction and were just asked to look at the screen. Trials in which participants did not look at the monitor for more than 50% during the pre-familiarization and learning phases (auditory learning: 1/64 trials; visual learning: 0/64 trials) were excluded from the analyses. On the remaining trials, trials in which participants did not look at both objects during the pre-naming period (auditory learning: 2/64 trials, visual learning: 1/64 trials) or did not look at the screen during the post-naming period (auditory learning: 2/64 trials, visual learning: 2/64 trials) were excluded from the analyses. We also removed visual test trials in which participants did not look at the model (auditory learning: 2/32 trials, visual learning: 1/32 trials).

Results

Using the same metric as in Experiment 1, looking time data were entered in a linear mixed effects model, taking as fixed effects, the learning groups (auditory versus visual), test conditions (‘same modality’ versus ‘cross-modality’) and test periods (pre-naming versus post-naming) as well as all interactions between these factors, and as random effects, effects of participants and items on intercepts and effects of participants on the slopes of the test condition and test period effects. The analysis revealed that the inclusion of labeling effect yielded a significant improvement in model fit to data: labeling, χ2(4, N = 32) = 38.92, p < .01. There was a reliable increase in target looking times during the post-naming period. Inclusion of all other fixed and random effects did not yield any significant improvement in model fit, suggesting that little of the individual variance remained to be explained (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Table showing the results of a maximum likelihood estimated model predicting adults’ performance. Parameter estimates include the mean performance (Mean) in the different conditions, the estimated coefficient (Estimate) of the fixed effects, the Variance of random effects and Chi-square statistics (χ2). Chi-square statistics are associated with pairwise model comparisons with (full model) versus without the effect of interest, where the model without the effect of interest includes all other effects. Planned comparisons test naming effects (test period: pre-naming versus post-naming) in each learning (auditory versus visual) and test (same modality versus cross-modality) condition.

| Parameters | Parameters estimates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | ||

| FIXED EFFECTS | ||||

| Main effects and interactions | ||||

| Learning | – | 01.99 (03.63) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 01.38, p= .85 | |

| Test condition | – | −00.93 (00.81) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 01.18, p= .88 | |

| Test period | – | 18.49 (03.81) | χ2(4, N = 32) = 38.92, p < .01 | |

| Test period* learning | – | −03.01 (06.34) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Test period* test condition | – | −04.63 (06.01) | χ2< 1 | |

| Test period* learning* test condition | – | −04.98 (12.67) | χ2< 1 | |

| Variance (SD) | Chi-square statistics | |||

| RANDOM EFFECTS | ||||

| Subjects on intercepts | – | 00.01 (00.01) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Items on intercepts | – | 00.48 (00.84) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Subjects on the slope of the test condition | – | 00.01 (00.01) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Subjects on the slope of the test period | – | 00.17 (00.73) | χ2 < 1 | |

| Mean (SD) | Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | ||

| PLANNED COMPARISONS | ||||

| Auditory | ||||

| Overall | Pre-naming | 50.41 (10.23) | 16.21 (04.89) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 09.53, p< .01 |

| Post-naming | 66.61 (20.38) | |||

| Same modality | Pre-naming | 49.77 (18.69) | 17.14 (06.84) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 07.27, p < .01 |

| Post-naming | 68.71 (23.71) | |||

| Cross-modality | Pre-naming | 51.04 (18.07) | 13.44 (07.70) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 04.13, p < .04 |

| Post-naming | 64.51 (26.37) | |||

| Visual | ||||

| Overall | Pre-naming | 47.62 (04.68) | 20.42 (04.68) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 14.53, p < .01 |

| Post-naming | 68.65 (16.78) | |||

| Same modality | Pre-naming | 45.53 (13.34) | 21.29 (05.39) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 12.49, p < .01 |

| Post-naming | 66.82 (24.62) | |||

| Cross-modality | Pre-naming | 49.71 (15.44) | 20.77 (04.63) | χ2(1, N = 16) = 16.80, p < .01 |

| Post-naming | 70.48 (15.98) | |||

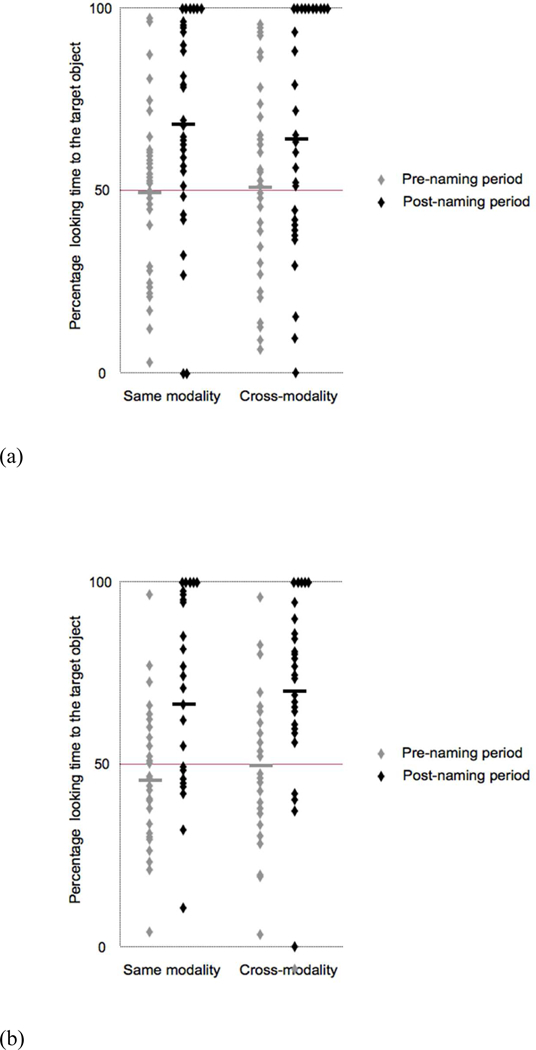

Overall, adults in the auditory learning group did not show a preference for either object before naming (M = 50.41%, SD = 10.23%), t < 1, but showed a preference for the target object after naming (M =66.61%, SD = 20.38%), t(15) = 3.45, p < .01, d = 1.78. Adults devoted greater attention to the target object upon naming in both the ‘same modality’: pre-naming (M = 49.77%, SD = 18.69%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 68.71%, SD = 23.71%), t(15) = 3.26, p < .01, d = 1.68; and the ‘cross-modality’ conditions: pre-naming (M = 51.04%, SD = 18.07%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 64.51%, SD = 26.37%), t(15) = 2.25, p = .04, d = 1.16, (see Figure 4a).

Figure 4.

Mean percentages of looking times at test in adults. Each data point represents individual data for (a) the auditory learning group and (b) the visual learning group in the pre-naming and post-naming periods of the two ‘same modality’ and the two ‘crossmodality’ test trials. Each participant contributes to eight data points: two for the pre-naming and two for the post-naming period of the ‘same modality’ test trials and two for the pre-naming and two for the post-naming period for the ‘cross modality’ test trials. The bold horizontal lines represent mean performance in each condition.

Adults in the visual learning group demonstrated a similar pattern of looking behavior. There was no preference for either object before naming (M = 47.62%, SD = 4.68%), t(15) = −1.24, p = .23, d = .64, but a significant preference for the target object after naming (M = 68.65%, SD = 16.78%), t(15) = 4.75, p < .01, d = 2.45. The magnitude of the effect was similar in the ‘same modality’: pre-naming (M = 45.53%, SD = 13.34%), t(15) = −1.11, p = .29, d = .57; post-naming (M = 66.82%, SD = 24.62%), t(15) = 2.81, p = .01, d = 1.45; and ‘cross-modality’ conditions: pre-naming (M = 49.71%, SD = 15.44%), t < 1; post-naming (M = 70.48%, SD = 15.98%), t(15) = 5.42, p < .01, d = 2.79, (see Figure 4b).

Altogether, these results indicate that adults are able to recognize a referent for a word, regardless of the modality of lexical learning (auditory versus visual), and irrespective of the correspondence between the modalities of learning and of testing.

To further evaluate differences between adults’ and infants’ performances, we ran a linear mixed effects model, taking as fixed effects, the ages (infant versus adult), the learning groups (auditory versus visual), test conditions (‘same modality’ versus ‘cross-modality’) and test periods (pre-naming versus post-naming) as well as all interactions between these factors, and as random effects, participants’ and items’ estimated intercepts and effects of participants on the slopes of the test condition and test period effects (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Table showing the results of a maximum likelihood estimated model predicting developmental changes in performance. Parameter estimates include the estimated coefficient (Estimate) of the fixed effects, the Variance of random effects and Chi-square statistics (χ2). Chi-square statistics are associated with pairwise model comparisons with (full model) versus without the effect of interest, where the model without the effect of interest includes all other effects. Planned comparisons test age-related differences in naming effects (age* test period), in each learning (auditory versus visual) and test (same modality versus cross-modality) condition.

| Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|

| Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | |

| FIXED EFFECTS | ||

| Main effects and interactions | ||

| Learning | 04.69 (02.59) | χ2(8, N = 64) = 13.15, p < .11 |

| Test condition | −00.45 (02.51) | χ2(8, N = 64) = 01.01, p < .99 |

| Test period | 12.31 (02.39) | χ2(8, N = 64) = 39.99, p < .01 |

| Age | 02.19 (02.68) | χ2(8, N = 64) = 06.88, p < .55 |

| Age* learning | −05.21 (05.13) | χ2(4, N = 64) = 07.11, p < .13 |

| Age* test condition | 03.39 (05.00) | χ2(4, N = 64) = 03.39, p < .49 |

| Age* test period | 12.68 (04.39) | χ2(4, N = 64) = 09.32, p < .05 |

| Age* test period* learning | 17.97 (09.61) | χ2(2, N = 64) = 06.11, p < .04 |

| Age* test period* test condition | 07.83 (08.31) | χ2 < 1 |

| Age* test period* learning* test condition | 05.31 (16.47) | χ2< 1 |

| Variance (SD) | Chi-square statistics | |

| RANDOM EFFECTS | ||

| Subjects on intercepts | 00.01 (00.01) | χ2 < 1 |

| Items on intercepts | 00.63 (00.54) | χ2 < 1 |

| Subjects on the slope of the test condition | 00.42 (00.38) | χ2 < 1 |

| Subjects on the slope of the test period | 00.49 (00.58) | χ2 < 1 |

| Estimate (SE) | Chi-square statistics | |

| PLANNED COMPARISONS | ||

| Auditory | ||

| Overall | 03.61 (06.41) | χ2 < 1 |

| Same modality | 01.12 (10.22) | χ2 < 1 |

| Cross-modality | 06.20 (09.08) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 01.29, p = .52 |

| Visual | ||

| Overall | 21.31 (05.98) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 12.95, p < .01 |

| Same modality | 15.53 (08.89) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 05.82, p = .05 |

| Cross-modality | 26.83 (08.97) | χ2(2, N = 32) = 12.43, p < .01 |

The analyses revealed that the inclusion of labeling effect as well as the age x labeling interaction and the age x labeling x learning interaction yielded a significant improvement in model fit to data: labeling, χ2(8, N = 64) = 39.99, p < .01; age x labeling, χ2(4, N = 64) = 9.32, p = .05; age x labeling x learning, χ2(2, N = 64) = 6.11, p = .04. There was an overall increase in target looking time during the post-naming period that was sharper in adults, especially in the visual learning condition: auditory, χ2<1; visual, χ2(2, N = 32) = 12.95, p < .01. Inclusion of all other fixed and random effects did not yield any significant improvement in model fit, suggesting that little of the individual variance remained to be explained (see Table 3).

Discussion

Experiment 2 was designed to provide an adult standard for comparison to the pattern found for the infants in Experiment 1. More specifically, the dual purposes of Experiment 2 were to 1) determine whether adults are able to learn new lexical mappings based on visible speech information and whether performance is similar to that observed in situations involving only auditory speech information, and 2) determine whether lexical recognition is tightly specified by the modality of learning or whether it has a representational format that contains, or is accessible from, a different modality.

In convergence with the literature, the present results reveal that when lexical learning and access were provided in the auditory modality, adults were able to identify the target object and make a stable lexical decision upon naming. Performance was similar when learning was limited to the presentation of the word with visible speech information only. Interestingly, performance was not sensitive to the modality of testing (auditory versus visual). Adults performed equally well when tested in the same modality as the one serving the learning process as they did when tested in a different modality.

General discussion

The purpose of the present study was to further our understanding of the effect of modality on newly established lexical representations and to determine whether infants and adults show the same capabilities. To address these questions, we evaluated both 18-month-olds’ and adults? capacity to use acoustic and visible speech information when learning a new word in a laboratory setting, and to recognize that word in either modality.

The results revealed that after an auditory learning phase, infants and adults successfully identified which of the two objects was named at test. In convergence with the literature, this indicates that infants and adults are able to learn new auditory word forms after only a short exposure (Havy et al., 2014; MacKenzie et al., 2011; Werker et al., 1998). Adults were also able to identify the named object after learning in the visual modality. This finding supports the view that, in adulthood, visible speech information plays an important role at the lexical level (Barutchu et al., 2008; Brancazio, 2004; Fort et al., 2010).

However, and in sharp contrast with infant performance in the auditory learning group, infants in the visual learning group performed at chance. This suggests that during lexical acquisition, infants have difficulty using visible speech information alone to form new lexical mappings, at least when taught and tested in this lexical learning task. This pattern is consistent with literature showing that children are more likely than adults to favor auditory over visual information. For example, in the McGurk illusion, children show greater auditory capture of conflicting audio-visual information, while adults show a more integrated percept (“the McGurk effect;” see Desjardins, & Werker, 2004; McGurk & MacDonald, 1976; Sekiyama & Burnham, 2008). Furthermore, there is no reliable evidence, prior to adulthood, of a lexical boost from the use of visual input to identify sounds of words embedded in noise (Fort et al., 2012). Our results are thus consistent with the view that visual speech may influence pre-lexical units (sounds, sound combinations, pseudo-words with no associated meaning) more than lexical units (word forms with meaning) in infants (Fort et al., 2012; Jerger et al., 2014).

The second thrust of our study was to determine whether lexical recognition is constrained by the modality in which the word form was learned, or whether it is instead multimodal, or at least auditory and visual. To address this question, we examined infants’ and adults’ capacity to learn a label in one modality (either auditory or visual) and then to recognize it in another modality (visual if learning in the auditory mode, auditory if learning in the visual mode). The results showed that after auditory or visual learning, adults performed well whether lexical recognition was in the same modality or in a modality different from the one serving the learning process. Interestingly, there was no asymmetry in performance. This pattern of results suggests that adult lexical representations allow recognition in both the auditory and visual domains. Similar to adults, infants were able to recognize a word based on the visible speech information after auditory learning; however, they failed to recognize a word based on its auditory information after having experienced the word visually during the learning phase. Thus, it may be the case that in early development the modality of lexical learning is more constrained than the modality of lexical access: auditory learning allows both auditory and visual access and does so with greater ease than visual learning.

These results, which show for the first time that infants have some degree of cross-modal access (from auditory to visual) to a newly established lexical representation, raise a number of questions for further study. Our results are consistent with the view that (a) a word form has a single lexical representation containing abstract or multisensory information, as well as the view that (b) a word form has two modality-specific lexical representations, with a mechanism assuring the transfer of information across these modalities. Parallel to these two positions are two views concerning lexical processing: (a) that auditory and visual speech are processed using a common lexical recognition system (Buchwald et al., 2009; Kim, Davis, & Krins, 2004), and (b) that there exist two modality-specific lexical systems (Fort et al., 2013; Tye-Murray, Sommers, & Spehar, 2007; for a review see Buchwald et al., 2009). This latter account is supported by recent evidence that adults show frequency and neighborhood effects specific to the acoustic domain and different ones specific to the visual domain, with audio-visual word recognition arising from the overlap between the two domains (Fort et al., 2013; Mattys et al., 2002; Tye-Murray et al., 2007). Whether lexical representations consist of a single versus two modality-specific representations and whether there is a developmental transition from one to the other is an important question for further study.

In the present study, adults were able to use either the auditory-only or the visible-only speech information when learning new word-object pairs. Yet, infants in the same testing conditions failed to demonstrate word-object learning when presented with visible-only speech information. Altogether, these data point towards auditory dominance in word learning at an early stage of lexical learning. However, it is unclear whether the auditory dominance that we see in infants’ performance disappears in adulthood due to increasing sensitivity to visible speech information or is still present but obscured due to the nature of the task used in this study. For example, there is evidence that adults do not consistently attend to visible speech information to identify the fine phonetic detail of familiar word forms in complex identification tasks (Samuel & Lieblich, 2014). Perhaps if phonetically similar words had been used in the present study, or the task had been made more difficult in some other way, evidence for auditory dominance would also have been seen in word learning.

Along these lines, it is useful to consider whether a particular aspect of our design enabled adults to show equal facility at learning new word-object associations when the words were presented only with visible speech as they did when the words were presented only with auditory speech. During the pre-familiarization phase of our study, participants were given an audio-visual presentation of the pseudo-words. While during this phase the words were not paired with objects, this pre-familiarization may have helped establish a bimodal word form representation, which then facilitated later word- object mapping. Indeed, previous studies have shown that a short audio-visual exposure improves subsequent unisensory processing in adults (e.g., for voice and face recognition of a talking face: Von Kriegstein, et al., 2008; non-native speech perception: Hazan, Sennema, Faulkner, Ortega-Llebaria, & Chung, 2006; word learning: Bernstein, Auer, Eberhardt, & Jiang, 2013). Arguably, it could similarly have done so in this study.

An important question for future research then, will be to ascertain whether visible speech can create, or be stored in, newly established lexical representations when they are taught through solely visible speech input. In fact, we might also ask whether a multimodal experience of the words is necessary to form multimodal lexical representations and if so, whether that experience must be specific to the lexical context or may have a general effect such that any word presented multimodally could foster a multimodal representation of any subsequent (same or different) word presented unimodally.

Similarly, it will be of importance in future research to determine whether infants can transfer from an auditory word learning situation to recognition in the visual-only modality without pre-familiarization with an auditory-visual presentation of the word. Perhaps that pre-familiarization experience left a trace that helped direct the auditory to visual transfer at test. However, if it was just the pre-familiarization phase that accounted for all of the results in this study, it should also have provided a benefit for learning the word-object association in the visual-only condition in the infants, and it did not. In addition, infants at this age can learn to associate visually presented hand gestures with objects (Suanda, et al, 2013). Thus, it is not simply the visual modality that they fail to use in the present study. Rather, they systematically fail to establish an acoustic-phonetic representation of the word-object mapping when the word is presented only through visible speech. Further studies are needed to determine when in development infants can reliably use the pairing of visible-only speech information with objects to form new lexical representations, as our adult participants did. In this regards, preliminary data indicate that 30-month-old children are able to learn words based on visible speech information (Havy & Zesiger, 2015). However, after having experienced the words visually, children only show recognition in the visual modality. Future studies will have to explore whether the observed change is modulated by task demands or reveals a developmental transition in the format of lexical representations.

Finally, as is always the case with a negative findings in infant research, it will be of import in future work to see if evidence of learning words based on visible speech can be seen if different testing methods are used. For example, perhaps a more indirect measure, such as reaction time, pupil dilation, or an ERP signature, could reveal word learning from visible speech even at 18 months of age, and/or transfer from a visual to an auditory word at 30 months of age.

One interesting area for further study is to investigate whether the pattern of results obtained in this study varies as a function of the properties of different languages or of different cultures. For instance, native Japanese speakers are less susceptible to visual influence in a McGurk task than native English speakers (Sekiyama, & Burnham, 2008), arguably because it is less acceptable to look at interlocutors’ mouths when they are speaking. Similar crosslinguistic differences may be found in the use of visible speech input during adult word learning. On the other hand, if there are languages and cultures in which adults show even stronger visual influences on speech perception than are reported in English, perhaps children will be able to use visible speech to establish lexical representations at an earlier age in those cultures.

Contributor Information

Mélanie Havy, University of British Columbia and Université de Genève.

Afra Foroud, University of British Columbia.

Laurel Fais, University of British Columbia.

Janet F. Werker, University of British Columbia

References

- Althaus N, & Plunkett K (2015). Timing matters: The impact of label synchrony on infant categorization. Cognition, 139, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baart M, Bortfeld H, & Vroomen J (2015). Phonetic matching of auditory and visual speech develops during childhood: Evidence from sine-wave speech. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 129, 157–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baayen RH, Davidson DJ, & Bates DM (2008). Mixed-effects modeling with crossed random effects for subjects and items. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 390–412. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr DJ, Levy R, Scheepers C, & Tily HJ (2013). Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. Journal of memory and language, 68, 255–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barutchu A, Crewther SG, Kiely P, Murphy MJ, & Crewther DP (2008). When /b/ill with /g/ill becomes /d/ill: Evidence for a lexical effect in audiovisual speech perception. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 20, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.05.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein LE, Auer ET Jr., Eberhardt SP, & Jiang J (2013). Auditory perceptual learning for speech perception can be enhanced by audiovisual training. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binnie CA, Montgomery AA, & Jackson PL (1974). Auditory and visual contributions to the perception of consonants. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 17, 619–630. doi: 10.1044/jshr.1704.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancazio L (2004). Lexical influences in audiovisual speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 30, 445–463. doi: 10.1037/0096-1523.30.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow D, Dehaene-Lambertz G, Mattout J, Soares C, Gliga T, Baillet S, & Jean-Mangin F (2009). Hearing faces: how the infant brain matches the face it sees with the speech it hears. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 21, 905–921. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald A, Winters SJ, & Pisoni DB (2009). Visual speech primes open-set recognition of auditory words. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24, 580–610. doi: 10.1080/01690960802536357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham D, & Dodd B (2004). Auditory-visual speech integration by prelinguistic infants: Perception of an emergent consonant in the McGurk effect. Developmental Psychobiology, 45, 204–220. doi: 10.1002/dev.20032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell R (2008). The processing of audio-visual speech: Empirical and neural bases. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B, 363, 1001–1010. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCoster J (2001). Transforming and restructuring data. From http://www.stathelp.com/notes.html

- Desjardins R, & Werker JF (2004). Is the integration of heard and seen speech mandatory for infants? Developmental Psychobiology, 45, 187–203. doi: 10.1002/dev.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort M, Kandel S, Chipot J, Savariaux C, Granjon L, & Spinelli E (2013). Seeing the initial articulatory gestures of a word triggers lexical access. Language and Cognitive Processes, 28, 1207–1223. doi: 10.1080/01690965.2012.701758. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fort M, Spinelli E, Savariaux C, & Kandel S, (2010). The word superiority effect in audiovisual speech perception. Speech Communication 52, 525–532. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6393(98)00051-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fort M, Spinelli E, Savariaux C, & Kandel S (2012). Audiovisual vowel monitoring and the word superiority effect in children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 36, 457–467. doi: 10.1177/0165025412447752. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Havy M, Serres J, & Nazzi T (2014). A consonant/vowel asymmetry in word-form processing: Evidence in childhood and in adulthood. Language and Speech, 57, 254–281. doi: 10.1177/0023830913507693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havy M, & Zesiger P (2015). Sensory format of lexical representations in 30-month-old infants. BUCLD 40, Boston, Massachusetts, November 13th-15th, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hazan V, Sennema A, Faulkner A, Ortega-Llebaria M, & Chung H (2006). The use of visual cues in the perception of non-native consonant contrasts. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119, 1740–1751. doi: 10.1121/1.2166611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson PL, Montgomery AA, & Binnie CA (1976). Perceptual dimensions underlying vowel lipreading performance. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 19, 796–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger TF (2008). Categorical data analysis: Away from ANOVAs (transformation or not) and towards logit mixed models. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 434–446. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger S, Damian MF, Spence MJ, Tye-Murray N, & Abdi H (2009). Developmental shifts in children’s sensitivity to visual speech: A new multimodal picture–word task. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102, 40–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerger S, Damian MF, Tye-Murray N, & Abdi H (2014). Children use visual speech to compensate for non-intact auditory speech. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 126, 295–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2014.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Davis C, & Krins P (2004). Amodal processing of visual speech as revealed by priming. Cognition, 93, B39–B47. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhl PK, & Meltzoff A (1982). The bimodal perception of speech in infancy. Science, 218, 1138–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnerenko E, Tomalski P, Ballieux H, Ribeiro H, Potton A, Axelsson EL, ... & Moore DG (2013). Brain responses to audiovisual speech mismatch in infants are associated with individual differences in looking behavior. European Journal of Neuroscience, 38, 3363–3369. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalonde K, & Holt RF (2015). Preschoolers benefit from visually salient speech cues. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58, 135–150. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-H-13-0343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKenzie H, Graham SA, & Curtin S (2011). 12-month-olds privilege words over other linguistic sounds in an associative learning task. Developmental Science, 14, 249–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2010.00975.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maidment DW, Kang HJ, Stewart HJ, & Amitay S (2014). Audiovisual integration in children listening to spectrally degraded speech. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 58, 61–68. doi: 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-14-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani N & Plunkett K (2007). Phonological specificity of vowels and consonants in early lexical representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 57, 252–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2007.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mattys SL, Bernstein LE, & Auer ET Jr. (2002). Stimulus-based lexical distinctiveness as a general word-recognition mechanism. Perception and Psychophysics, 64, 667–679. doi: 10.3758/BF03194734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGurk H, & MacDonald J (1976). Hearing lips and seeing voices. Nature, 264, 746–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, & Nicely PE (1955). An analysis of perceptual confusions among some English consonants. Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 27, 338–445. [Google Scholar]

- Nath AR, Fava EE, & Beauchamp MS (2011). Neural correlates of interindividual differences in children’s audiovisual speech perception. Journal of Neuroscience, 31, 13963–13971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUR0SCI.2605-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazzi T, Floccia C, Moquet B, & Butler J (2009). Bias for consonantal information over vocalic information in 30-month-olds: Cross-linguistic evidence from French and English. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102, 522–537. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nespor M, Peña M, & Mehler J (2003). On the different roles of vowels and consonants in speech processing and language acquisition. Lingue e Linguaggio, 2, 221–247. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrand R, Blumstein SE, & Morgan JL (2011). When hearing lips and seeing voices becomes perceiving speech: Auditory-visual integration in lexical access. In Carlson L, Holscher C, & Shipley T (Eds.), Proceedings of the 33rd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society (pp. 1376–1381). Austin, TX: Cognitive Science Society. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson ML, & Werker JF (2003). Two-month-old infants match phonetic information in lips and voice. Developmental Science, 6, 191–196. doi: 10.1111/1467-7687.00271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pons F, Lewkowicz DJ, Soto-Faraco S, & Sebastián-Gallés N (2009). Narrowing of intersensory speech perception in infancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 106, 10598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robert-Ribes J, Schwartz J-L, Lallouache T, & Escudier P (1998). Complementary and synergy in bimodal speech: Auditory, visual and audiovisual identification of French oral vowels. Journal of Acoustical Society of America, 103, 3677–3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost GC, & McMurray B (2009). Speaker variability augments phonological processing in early word learning. Developmental Science, 12, 339–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel AG, & Lieblich J (2014). Visual speech acts differently than lexical context in supporting speech perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 40, 1479. doi: 10.1037/a0036656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiyama K, & Burnham D (2008). Impact of language on development of auditory-visual speech perception. Developmental Science, 11, 306–320. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan EA, Namy LL, & Mills DL (2007). Developmental changes in neural activity to familiar words and gestures. Brain and Language, 101, 246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto-Faraco S, Calabresi M, Navarra J, Werker JF, & Lewkowicz DJ (2012). Development of audiovisual speech perception In Bremner A, Lewkowicz D and Spence C (Eds). Multisensory development, (pp. 435–452). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Streri A, Coulon M, Marie J, & Yeung HH (2015). Developmental change in infants’ detection of visual faces that match auditory vowels. Infancy. In press. doi: 10.1111/infa.12104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suanda SH, Walton KM, Broesch T, Kolkin L, & Namy LL (2013). Why two-year-olds fail to learn gestures as object labels: Evidence from looking time and forced-choice measures. Language Learning and Development, 9, 50–65. doi: 10.1080/15475441.2012.723189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumby WH, & Pollack I (1954). Visual contribution to speech intelligibility in noise. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 26, 212–215. [Google Scholar]

- Swingley D, & Aslin RN (2000). Spoken word recognition and lexical representation in very young children. Cognition, 76, 147–166. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(00)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teinonen T, Aslin RN, Alku P, & Csibra G (2008). Visual speech contributes to phonetic learning in 6-month-old infants. Cognition, 108, 850–855. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji S, & Cristia A (2014). Perceptual attunement in vowels: A meta-analysis. Developmental psychobiology, 56, 179–191. doi: 10.1002/dev.21179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye-Murray N, Sommers M, & Spehar B (2007). Auditory and visual lexical neighborhoods in audiovisual speech perception. Trends in Amplification, 11, 233–242. doi: 10.1177/1084713807307409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Kriegstein K, Dogan O, Grüter M, Giraud AL, Kell C, Grüter T, ... & Kiebel SJ (2008). Simulation of talking faces in the human brain improves auditory speech recognition. Proceedings of the National Academy Sciences, 105, 6747–6752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weikum WM, Vouloumanos A, Navarra J, Soto-Faraco S, Sebastian-Galles N, & Werker JF (2007). Visual language discrimination in infancy. Science, 316, 1159–1159. doi: 10.1126/science.1137686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, Cohen LB, Lloyd VL, Casasola M, & Stager CL (1998). Acquisition of word–object associations by 14-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1289–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werker JF, & Curtin S (2005). PRIMIR: A developmental framework of infant speech processing. Language Learning and Development, 1, 197–234. doi: 10.1207/s15473341lld0102_4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White KS, & Morgan JL (2008). Sub-segmental detail in early lexical representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 59, 114–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2008.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida KA, Fennell CT, Swingley D, & Werker JF (2009). Fourteen-month-old infants learn similar sounding words. Developmental Science, 12, 412–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00789.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]