The pace of technological advancements in the intensive care unit (ICU) challenges clinicians’ ability to manage ethical and decision-making challenges near the end of life. Modern medicine has advanced to the point where we can support multiple organ systems simultaneously and sustain life when the benefits of treatments to overall survival and quality of life are not always clear. Physiological and technological limits no longer always tell us when to stop and clinicians and families are now forced to take over the role that was once played by nature to make decisions as to whether and when life-sustaining therapies should be withdrawn or withheld.

Unfortunately, we often don’t do a very good job of making these tough decisions even when patients can participate in the discussion. Patients often lack decision-making capacity during their ICU stay, clinicians and families struggle to balance the inherently imperfect practice of substituted judgment with their own views on the best interests of the patient. Advance care planning can facilitate this process, but even with the best advance care planning it is often a complex and uncertain process.

Recent evidence indicates that we are not negotiating this complex process well.1,2 Life-sustaining therapies are increasingly provided at the end of life in a way that confers no survival benefit and can cause harm. Older Americans with advanced dementia have experienced a doubling in the use of mechanical ventilation and a rise in ICU admission from 17 to 38% of those hospitalized in the last 30 days of life without substantial survival benefit.1,2 A recent cluster-randomized trial suggests that systematically increasing ICU admissions for older adults confers no mortality benefit3 and other studies have shown a trend towards harm4,5. Hospitals with higher frequency of ICU use have higher costs and greater use of invasive procedures without improvement in mortality5. Overly aggressive, non-beneficial treatments are associated with reduced quality of life near death and lower perceptions of quality of care. 6–10 Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression are more likely amongst caregivers of patients who experience overly aggressive treatments.11–15 The ethical challenges inherent to considering the burdens and benefits of life sustaining therapies near the end of life care, especially in the ICU, can be highly contentious and challenging.16,17

In the high-stakes environments of the ICU, clinician moral distress, originally defined by Jameton18 as the inability to act according to an individual’s ethical beliefs due to structural or hierarchical constraints, can be particularly prevalent.19 While nurses have recognized the importance of ethical climate and moral distress for decades,20 awareness of physician moral distress is a newer area of inquiry,21,22 perhaps reflecting the growing tensions that have arisen as a result of shifts in societal expectations surrounding autonomy and declines in physician power.23 While moral distress can occur in all areas of health care, perceived futile care is a particularly difficult and common ethical challenge in the ICU that frequently leads to clinician moral distress.21,24

Moral distress is an ethical root cause of clinician burnout,25 an urgent problem that affects more than half of US physicians.26 Clinician burnout is linked to poor clinician well being, job dissatisfaction, and job turnover.27–29 Burnout amongst medical students contributes to unprofessional behavior and declines in empathy.30–32 Clinician burnout has negative effects on patient care including reduced patient satisfaction, quality of care, patient rapport, and patient safety with higher rates of medical errors.33–35

Interventions to mitigate clinician moral distress and burnout tend to focus on the individual clinicians.36–39 Cultivating mindfulness and resilience are important and necessary steps to alleviate moral distress, but must be integrated with interventions that target broader cultural norms that influence clinician behavior and integrity. Though some have described the need to consider organizational and systems factors, little is known about the precise systemic inflection points and levers that influence moral distress and burnout.40 In particular, ethical climate, defined as “individual perceptions of the organization that influences attitudes and behavior and serves as a reference for employee behavior”41, should be recognized as an important contributor that either alleviates or exacerbates moral distress.

In this issue of BMJ Quality and Safety, Van den Bulcke and colleagues report the development and validation of the Ethical Decision-Making Climate Questionnaire (EDMCQ).42 This is an important step in allowing us to understand and subsequently design and evaluate interventions that modify an ICU’s ethical climate to alleviate clinician moral distress and burnout and improve the patient and families’ experience. The authors developed this 35-question self-assessment instrument through a modified Delphi method that created a theoretical framework for ethical decision-making. The instrument was subsequently validated in 68 ICUs in 13 European countries and the United States. The ethical decision-making domains included within the EDMCQ are interdisciplinary collaboration and communication, leadership by physicians, and ethical climate. Though moral distress can manifest in many different ways, the EDMCQ allows us to specifically measure aspects of ethical climate as they relate to moral distress due to decision-making surrounding intensity of ICU care.

A clinician’s decisions do not occur in a vacuum, but are instead embedded in a cultural milieu influenced by national policy, financial incentives, resource pressures, patient and family factors, and institutional leadership. Policy changes and systemic interventions can have unintended consequences that further disrupt this interconnected ecosystem.43 In a recent qualitative study, one of us (E.D.) found that an institution’s ethical priority influenced the way physicians conceptualized autonomy and beneficence which consequently influenced communication practices surrounding resuscitation decision-making near the end of life.44 The study also revealed the importance of systemic factors such as institutional cultural norms that contributed to inappropriately aggressive care at the end of life in the US.45 This study and others highlight the importance of understanding and intervening upon these institutional and ethical norms to mitigate overly aggressive care.46,47 We have previously hypothesized that interventions may be more effective if they target the attitudes, beliefs and culture that underlie communication practices rather than only the practices themselves.45

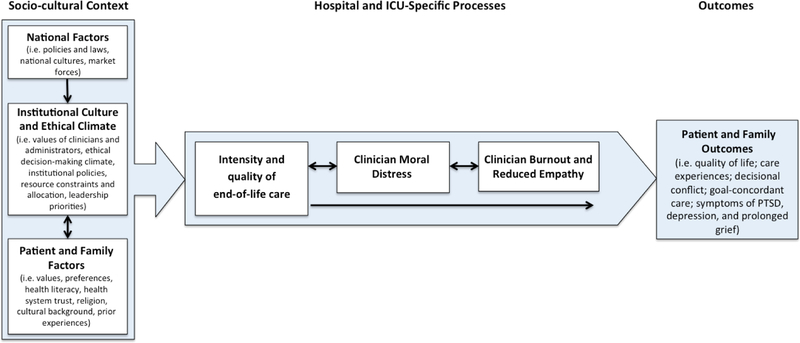

We propose a conceptual framework (Figure 1) highlighting the importance of institutional culture and, in particular, of institutional ethical climate, which influences intensity of end-of-life care in the ICU and hospital setting, which subsequently contributes to clinician moral distress and burnout. We hypothesize that this causal pathway from ethical climate, to intensity of care, and subsequent moral distress and burnout result in substantive effects on patient and family outcomes including quality of life, experience of care, and presence of symptoms of PTSD, depression, and prolonged bereavement. As such, the importance of the EDMCQ is its ability to measure, guide, and evaluate interventions on the ethical decision-making climate, providing the potential to improve patient, family, and clinician outcomes.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model describing the relationship between ethical climate, clinician moral distress and burnout, and patient and family outcomes. The EDMCQ focuses on institutional culture and ethical climate and its influence on Institutional norms, which influence the intensity of end of life care.

Multiple qualitative and quantitative studies in the nursing literature have found that a positive ethical climate facilitated less moral distress amongst nurses.48–50 Given that in the ICU, clinical decision-making is at the nexus of ethical challenges surrounding life-sustaining therapies near the end of life and a crucial moment for shifts in care trajectory, ethical decision-making climate is a key aspect of ICU ethical climate. The EDMCQ homes in on this critical facet of ethical climate that specifically links ethical climate with ICU treatment decisions at the end of life.

The EDMCQ scale is a valuable addition and update to existing ethical climate scales, the most prominent being the Olsen Hospital Ethical Climate Survey (HECS), which was designed and validated in the nursing literature.51 The HECS is a measure of ethical climate amongst nurses and focuses on factors related to nurses’ relationships with actors within the hospital system such as nurse peers, patients, managers, hospital administrators and physicians. The EDMCQ focuses on physicians and nurses as well as unit physician leadership, which all have profound effects on both ethical climate and ethical decision-making climate.

Given that physicians are often in positions of power in the hospital, involvement of and measurements that include physicians are important to an assessment of ethical culture. Studies using the HECS in physicians and nurses have shown that physicians generally rated ethical climate more positively than nurses,52 highlighting the power differential and affirming the importance of the EDMCQ’s focus on inter-professional (particularly nurse-physician) trust, collaboration, and communication. In particular, the EDMCQ’s emphasis on the hearing the voices of all members of the team highlights the importance of the moral agency to speak up as being an important part of fostering positive ethical climates and alleviate moral distress.53,54 Furthermore, the EDMCQ’s emphasis on interdisciplinary collaboration and communication is important as unit dysfunction and intra-team discordance exacerbates moral distress amongst members of the ICU team.19

The paper by Van den Bulcke and colleagues has some important strengths and weaknesses. In terms of strengths, this is a large and well-conducted study that included 3610 nurses and 1137 physicians working in 68 adult ICUs across Europe and the United States. The authors used a careful modified Delphi approach to develop a survey with strong face validity and they used rigorous and state-of-the-art exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to determine the structure of the ethical decision-making climate concept. This report also has some important weaknesses. First, the 68 ICUs represent a convenience sample of ICUs that were willing to participate, though it is difficult to know how this might affect the findings. Second, the reports of ICU clinicians on their own ethical decision-making climate will undoubtedly be influenced by some degree of reporting bias as well as by the fact that ICU clinicians may have limitations in their ability to observe the ethical norms in which they practice. Given these strengths and weaknesses, the EDMCQ is an important new measurement tool that should undergo additional validation as well as be compared with other methods to understand and assess the ethical decision-making climates in our ICUs.

We believe there has been insufficient recognition of moral distress as a key contributor to clinician burnout and poor well-being. Clinician burnout is a topic that has garnered significant interest and attention over the past several years.34,55,56 In light of this crisis of clinician burnout, there is an urgent need to look to systemic and cultural root causes of burnout. One of the barriers to focusing on institutional culture and systems change is that it is difficult to measure culture. The EDMCQ helps advance the field by providing ways to measure ethical decision-making climate, thus facilitating future descriptive and intervention studies focusing on institutional and ethical culture to improve patient and family outcomes. Another benefit of the EDMCQ and other instruments that focus on the more humanistic aspects of medicine57 is that it draws attention to an institutional prioritization of ethics and ethical climate amongst clinicians and administrators.58 The EDMCQ is an important step in improving the ethical decision-making climate of ICUs around intensity of end-of-life care and understanding its subsequent impact on the patient and family experience.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the NIH under Award Number KL2TR001870. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Teno J, Gozalo P, Khandelwal N, et al. Association of Increasing Use of Mechanical Ventilation Among Nursing Home Residents With Advanced Dementia and Intensive Care Unit Beds. JAMA Intern Med 2016:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teno JM, Gozalo PL, Bynum JPW, et al. Change in End-of-Life Care for Medicare Beneficiaries: Site of Death, Place of Care, and Health Care Transitions in 2000, 2005, and 2009. J Am Med Assoc 2013;309(5):470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boumendil A, Angus DC, Guitonneau A, Menn A, Aegerter P. Variability of Intensive Care Admission Decisions for the Very Elderly. PLoS One 2012;7(4):e34387. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidet B, Leblanc G, Simon T, et al. Mortality Among Critically Ill Elderly Patients in France. J Am Med Assoc 2017:1–10. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13889. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang D, Shapiro M. Association Between Intensive Care Unit Utilization During Hospitalization and Costs, Use of Invasive Procedures, and Mortality. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176(10):1492–1499. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huynh TN, Kleerup EC, Wiley JF, et al. The frequency and cost of treatment perceived to be futile in critical care. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173(20):1887–1894. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earle CC, Neville B a, Landrum MB, Ayanian JZ, Block SD, Weeks JC. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol 2004;22(2):315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prigerson H, Bao Y, Shah M, et al. Chemotherapy Use, Performance Status, and Quality of Life at the End of Life. JAMA Oncol 2015;1(6):778–784. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family Perspectives on Aggressive Cancer Care Near the End of Life. J Am Med Assoc 2016;315(3):284–292. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wright AA, Ray A, Mack JW, et al. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. J Am Med Assoc 2008;300(14):1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zanten SAVDB Van, Dongelmans DA, Dettling-ihnenfeldt D. Caregiver Strain and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms of Informal Caregivers of Intensive Care Unit Survivors. Rehabil Psychol 2016;61(2):173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haines K, Denehy L, Skinner EH, Warrillow S, Berney S. Psychosocial Outcomes in Informal Caregivers of the Critically Ill: A Systematic Review. Crit Care Med 2015;43(5):1112–1120. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andresen M, Guic E, Orellana A, Jose M, Castro R. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in close relatives of intensive care unit patients: Prevalence data resemble that of earthquake survivors. J Crit Care 2015;30(5):1152.e7–1152.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Probst DR, Gustin JL, Goodman LF, Lorenz A, Gregorio SMW. ICU versus Non-ICU Hospital Death: Family Member Complicated Grief, Posttraumatic Stress, and Depressive Symptoms. J Palliat Med 2016;19(4):387–393. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright A a, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA 2008;300(14):1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An Official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/SCCM Policy Statement : Responding to Requests for Potentially Inappropriate Treatments in Intensive Care Units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191(11):1318–1330. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201504-0750ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneiderman LJ, Jecker NS. Wrong Medicine: Doctors, Patients, and Futile Treatment 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jameton A Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bruce CR, Miller SM, Zimmerman JL. A Qualitative Study Exploring Moral Distress in the ICU Team: The Importance of Unit Functionality and Intrateam Dynamics. Crit Care Med 2014;(3):1–9. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schluter J, Winch S, Holzhauser K, Henderson A. Nurses’ Moral Sensitivity and Hospital Ethical Climate: A Literature Review. Nurs Ethics 2008;15(3):304–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dzeng E, Colaianni A, Roland M, et al. Moral Distress Amongst American Physician Trainees Regarding Futile Treatments at the End of Life: A Qualitative Study. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31(1):93–99. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3505-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houston S, Casanova M a., Leveille M, et al. The intensity and frequency of moral distress among different healthcare disciplines. J Clin Ethics 2013;24(2):98–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starr P The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. Basic Books; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mobley MJ, Rady MY, Verheijde JL, Patel B, Larson JS. The relationship between moral distress and perception of futile care in the critical care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007;23(5):256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rushton C, Batcheller J, Schroeder K, Donohue P. Burnout and Resilience Among Nurses Practicing in High-Intensity Settings. Am J Crit Care 2015;24(5):412–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T, Sinsky C, et al. Burnout Among Health Care Professionals: A Call to Explore and Address This Underrecognized Threat to Safe, High-Quality Care. National Academy of Medicine https://nam.edu/burnout-among-health-care-professionals-a-call-to-explore-and-address-this-underrecognized-threat-to-safe-high-quality-care/. Accessed March 12, 2018.

- 27.Shanafelt T, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and Satisfaction With Work-Life Balance Among US Physicians Relative to the General US Population. Arch Intern Med 2012;172(18):1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shanafelt T, Sloan J, Satele D, Balch C. Why Do Surgeons Consider Leaving Practice? J Am Coll Surg 2011;212(3):421–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shanafelt T, Balch C, Bechamps G, et al. Burnout and Career Satisfaction Among American Surgeons. Ann Surg 2009;250(3):463–471. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ac4dfd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brazeau CMLR, Schroeder R, Rovi S, Boyd L. Relationships between medical student burnout, empathy, and professionalism climate. Acad Med 2010;85(10):S33–S36. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4c47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas MR, Dyrbye LN, Huntington JL, et al. How do distress and well-being relate to medical student empathy? A multicenter study. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22(2):177–183. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0039-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dyrbye LN, Massie FS, Eacker A, et al. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. Jama 2010;304(11):1173–1180. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open 2017;7. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dzau VJ, Kirch DG, Nasca TJ. To Care Is Human — Collectively Confronting the Clinician-Burnout Crisis. N Engl J Med 2018;178(4):312–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, et al. The Relationship Between Professional Burnout and Quality and Safety in Healthcare: A Meta-Analysis. J Gen Intern Med 2016;32(4):475–482. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3886-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rushton CH. Principled moral outrage: an antidote to moral distress? AACN Adv Crit Care 2013;24(1):82–89. doi: 10.1097/NCI.0b013e31827b7746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rushton CH, Sellers DE, Heller KS, Spring B, Dossey BM, Halifax J. Impact of a contemplative end-of-life training program: being with dying. Palliat Support Care 2009;7(4):405–414. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rushton CH, Kaszniak AW, Halifax JS. Addressing moral distress: application of a framework to palliative care practice. J Palliat Med 2013;16(9):1080–1088. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rushton C, Reder E, Hall B, Comello K, Sellers D, Hutton N. Interdisciplinary Interventions To Improve Pediatric Palliative Care and Reduce Health Care Professional Suffering. J Palliat Med 2006;9(4):922–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Back AL, Steinhauser KE, Kamal AH, Jackson VA. Building Resilience for Palliative Care Clinicians: An Approach to Burnout Prevention Based on Individual Skills and Workplace Factors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52(2):284–291. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson L Hospital nurses’ perceptions of the ethical climate of their work setting. J 1998;30(4):345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bulcke B Van Den, Piers R, Jensen HI, et al. Ethical decision-making climate in the ICU : theoretical framework and validation of a self-assessment tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2018;(February):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kaufman S And a Time to Die: How American Hospitals Shape the End of Life. first Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dzeng E, Colaianni A, Roland M, et al. Influence of Institutional Culture and Policies on Do-Not-Resuscitate Decision Making at the End of Life. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(5):812–819. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dzeng E, Dohan D, Curtis JR, Smith TJ, Colaianni A, Ritchie CS. Homing in on the Social : System-Level Influences on Overly Aggressive Treatments at the End of Life. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55(2):282–289.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnato AE, Tate JA, Rodriguez KL, Zickmund SL, Arnold RM. Norms of Decision Making in the ICU: A Case Study of Two Academic Medical Centers at the Extremes of End-of-life Treatment Intensity. Intensive Care Med 2012;38(11):1886–1896. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2661-6.Norms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelley AS, Bollens-Lund E, Covinsky KE, Skinner J, Morrison S. Prospective Identification of Patients at Risk for Unwarrented Variation in Treatment. J Palliat Med 2018;21(1):44–54. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2017.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Corley MC, Minick P, Elswick RK, Jacobs M. Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nurs Ethics 2005;12(4):381–390. doi: 10.1191/0969733005ne809oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pauly B, Varcoe C, Storch J, Newton L. Registered Nurses ‘ Perceptions of Moral Distress and Ethical Climate. Nurs Ethics 2009;16(5):561–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Atabay G, Cangarli BG, Penbek S. Impact of ethical climate on moral distress revisited: Multidimensional view. Nurs Ethics 2014;(156):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Olson L Hospital Nurses’ Perceptions of the Ethical Climate of Their Work Setting. J Nurs Scholarsh 1998;30(4):345–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bartholdson C, Sandeberg M, Lutzen K, Blomgren K, Pergert P. Healthcare professionals’ perceptions of the ethical climate in paediatric cancer care. Nurs Ethics 2016;23(8):877–888. doi: 10.1177/0969733015587778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yerramilli D On cultivating the courage to speak up: the critical role of attendings in the moral development of physicians in training. Hastings Cent Rep 2014;44(5):30–32. doi: 10.1002/hast.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robinson EM, Lee SM, Zollfrank A, Jurchak M, Frost D, Grace P. Enhancing moral agency: clinical ethics residency for nurses. Hastings Cent Rep 2014;44(5):12–20. doi: 10.1002/hast.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From Triple to Quadruple Aim: Care of the Patient. Ann Fam Med 2014;12(6):573–576. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713.Center. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler CN. A Critical Care Societies Collaborative Statement: Burnout Syndrome in Critical Care Health-care Professionals A Call for Action. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2016;194(1):106–113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0708ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beach MC, Topazian R, Chan KS, Sugarman J, Geller G. Climate of Respect Evaluation in ICUs: Development of an Instrument (ICU-CORE). Crit Care Med 2018:1–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hafferty FW. Beyond Curriculum Reform: Confronting Medicine’s Hidden Curriculum. Acad Med 1998;73(4):403–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]