Abstract

In all but eight states, Medicare supplemental coverage (or Medigap) plans may deny coverage or charge higher premiums on the basis of preexisting health conditions. This may particularly affect chronically ill or high-need Medicare Advantage enrollees who switch to traditional Medicare and subsequently discover that they are unable to purchase affordable Medigap coverage. We found that in states with no Medigap consumer protections, high-need Medicare Advantage enrollees had a 16.9-percentage-point higher reenrollment rate in Medicare Advantage in the year after switching to traditional Medicare, compared to high-need enrollees in states with strong Medigap consumer protections—namely, guaranteed issue and community rating (charging all enrollees the same premium regardless of health condition). Expanding protections in the Medigap market may increase consumers’ access to this type of supplemental coverage.

Medigap is an optional form of private supplemental coverage that covers cost sharing for traditional Medicare beneficiaries. Medigap plans are offered by private insurance companies, and their benefits are tightly regulated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). About 25 percent of all traditional Medicare beneficiaries are enrolled in a Medigap plan each year, with substantial variation across states.1 While Medigap plays an important role in covering out-of-pocket spending for Medicare enrollees, the private insurers that offer Medigap policies may place restrictions on enrollees who have preexisting health conditions. Only eight states require community rating (charging all enrollees the same premium regardless of disease) in Medigap (Alaska, one of these states, was excluded from the study as explained below). Of these eight states, four also require guaranteed issue (in which all enrollees must be offered coverage irrespective of their health status).1

Medicare Advantage (MA) is an alternative to traditional Medicare.2 In MA, a private insurer receives capitated payments from CMS to finance most Medicare-covered services that a beneficiary requires within a year. MA plans may put several restrictions on access to care for enrollees (such as narrow networks and prior authorization), but they may also provide additional benefits not available in traditional Medicare (such as gym memberships and dental care).3 A beneficiary may not enroll in both Medigap and MA at the same time because coverage would be duplicative. However, Medigap enrollees may enroll in a stand-alone Part D drug plan without losing Medigap coverage. Unlike Medigap, MA is required to offer both guaranteed issue and community rating to its beneficiaries. MA plans also tend to have lower premiums than Medigap plans, with more than half of MA plans having no premium,4 compared to a national average Medigap monthly premium of $180.5

During beneficiaries’ first twelve months of Medicare eligibility, beginning at age sixty-five, federal law requires insurers to offer guaranteed issue for Medigap plans without restrictions for preexisting conditions or any other sociodemo-graphic factor. Insurers are also prohibited from charging higher premiums for preexisting conditions. However, in most states they are not required to cover cost sharing for those conditions for up to six months after enrollment.1 Additional federal protections permit beneficiaries to enroll in Medigap plans when they move to a new area, if their old plan ceases operation, or within the first year of enrollment in MA. After the first year of enrollment in MA, however, there are no other federal protections for beneficiaries who switch from MA into traditional Medicare.

For beneficiaries younger than age sixty-five who are eligible for Medicare on the basis of disability, most states do not require guaranteed issue or restrict medical underwriting (the setting of premiums based on health status) regarding Medigap.6 Those who are fully dually eligible for Medicaid and Medicare are not permitted to enroll in Medigap, but they are offered guaranteed issue in nine states upon losing Medicaid coverage.1 Partially dually eligible enrollees who do not receive full dual benefits may opt into Medigap plans, and several states elect to pay for enrollee Medigap premiums.

Once enrolled in Medigap, enrollees may opt to drop out of a Medigap plan if they become dually eligible, decide that the Medigap monthly premiums outweigh the cost they would face with standard cost sharing, are unable to afford the premiums, or simply prefer to do so.

MA enrollees who experience adverse health events or who have greater needs switch from MA into traditional Medicare at higher rates.7–10 These higher-need enrollees are more likely to face restrictions in enrolling in, and have to pay higher premiums for, Medigap plans—which may lead them to reenroll in MA. Past work has found some associations between increased Medigap premiums and MA penetration, but not in the post-Affordable Care Act (ACA) environment and without a focus on the state policy differences.11,12 In this study we assessed whether state variation in consumer protections in the Medigap market was associated with reenrollment in MA.

Study Data And Methods

Using the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File, we identified all MA beneficiaries in 2014 who switched to traditional Medicare in 2015. Among these switchers, we identified those who reenrolled in MA in 2016. We excluded decedents (n = 321,640), people who moved during the time period because they have additional enrollment opportunities (n = 47,766), those whose MA plans became unavailable in their markets (n = 5,138), and residents of Alaska (828) because of that state’s low rate of MA enrollment. We also excluded enrollees who did not have twelve months of MA coverage in 2014 (n = 2,008,727), because Medicare allows a twelve-month shopping period during which enrollees may still enroll in Medigap with guaranteed issue. From our analysis of comparing reenrollment across guaranteed-issue and community-rating states, we excluded people younger than age sixty-five (n = 3,037,863) and those who are dually eligible (n = 570,669), because they face different Medigap enrollment rules than other Medicare beneficiaries do. We included these two populations in our analyses of switching from MA to traditional Medicare and in separate models that looked at reenrollment regardless of state policies. Our final sample included 9,853,589 beneficiaries.

Defining High-Need Enrollees

We classified enrollees as high need if they had two or more complex chronic conditions, six or more chronic conditions, any diagnoses indicative of frailty, or dependency in activities of daily living in 2014, as measured in Medicare Provider Analysis and Review inpatient claims, Minimum Data Set nursing home assessments, Outcome and Assessment Information Set home health assessments, and Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility Patient Assessment Instrument skilled rehabilitation data.13 The last three sources report complete data for MA enrollees, while the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review file reports hospitalizations for MA enrollees admitted to hospitals that receive disproportionate share hospital or medical education payments,14 which account for more than 90 percent of hospital discharges of MA enrollees. While we might not have accounted for all MA enrollees with chronic illness in our analysis, this definition of need has been strongly associated with future hospitalizations13 and switching out of MA.10

Analysis

Our primary outcome was MA reenrollment in 2016 after a 2015 switch to traditional Medicare. We modeled both switching to traditional Medicare and reenrollment in MA using a linear probability model at the patient level, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, state MA penetration, high-need status, and rural residence.

Alaska (excluded from this study), Minnesota, Vermont, and Washington require community rating protections in Medigap enrollment. Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and New York have both community rating and guaranteed issue. We included a categorical variable designating whether a state had no protections, community rating only, or both community rating and guaranteed issue.

We ran sensitivity analyses that restricted our analysis to the Northeast (where most consumer-protection states are located) and for each state separately to quantify variation across states.

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, only four states protected against preexisting condition exclusions by having guaranteed issue, and only eight states required community rating (Alaska was excluded from our study, as explained above). These states may differ from the remaining states in ways that we could not observe in our data. For example, Vermont has relatively low MA enrollment, and Minnesota has a greater number of Medicare Cost plans (which allow beneficiaries the flexibility to see out-of-network providers), which may have affected our estimates.

Second, we lacked data about why beneficiaries initially switched from MA. Additionally, we could not determine who applied for, received, or was denied Medigap coverage. Thus, our analysis could not demonstrate a causal link between state Medigap policies and reenrollment. If there is state variation in Medicare Provider Analysis and Review reporting of MA enrollees, then it may also have affected our definition of high need.

Third, we lacked data on how much Medigap or MA premiums cost in each state, so there may have been variation in these two premium costs across markets that could have influenced enrollee behavior. It is possible that Medigap premiums are higher in states with consumer protections, which could affect the likelihood of exiting MA to purchase a Medigap plan.

Study Results

Approximately 5 percent of all MA enrollees in 2014 switched to traditional Medicare in 2015 (exhibit 1). Of these beneficiaries, 42 percent reenrolled in MA in 2016. Those who initially switched were less likely to be white, more likely to be younger and to be dually eligible with Medicaid, and more often lived in rural areas, compared to those who did not initially switch. Enrollees in states with guaranteed issue and community rating had lower rates of switching from MA to traditional Medicare than those in states without protection (4.5 percent of non-high-need and 7.5 percent of high-need beneficiaries switched to traditional Medicare in states without protection, compared to 4.0 percent and 6.2 percent, respectively, in guaranteed-issue and community-rating states) (online appendix exhibit A1).15

Exhibit 1.

Characteristics of beneficiaries by whether or not they switched from Medicare Advantage (MA) in 2014 to traditional Medicare in 2015, and the enrollment choice in 2016 of those who switched

| Switched from MA to traditional Medicare in 2015 | Reenrolled in MA in 2016 after switching to traditional Medicare in 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | No | Yes | |

| Number of beneficiaries | 12,653,211 | 638,701 | 370,884 | 267,817 |

| Percent of beneficiaries | 95 | 5 | 58 | 42 |

| Mean age (years) | 71 | 70 | 70 | 70 |

| Female (%) | 57 | 58 | 57 | 59 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 80 | 79 | 80 | 78 |

| Black | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 |

| Other or unknown | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| Asian | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Hispanic | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 |

| Native American or American Indian | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Dually eligible for Medicaid (%) | 18 | 25 | 24 | 26 |

| Mean state MA penetration (%) | 33 | 31 | 30 | 32 |

| Rural (%) | 17 | 22 | 25 | 18 |

| High need (%) | 6 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2014–16 from the Master Beneficiary Summary File. NOTES The two columns for “Reenrolled in MA” are components of the “yes” column under “Switched from MA to traditional Medicare in 2015.” “High need” is defined in the text.

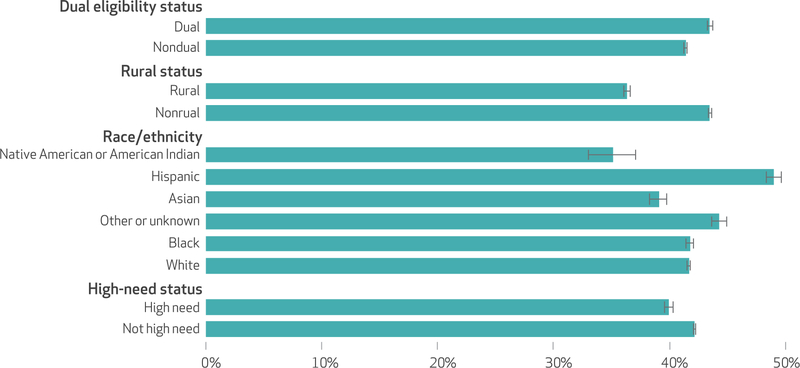

When we adjusted for other beneficiary characteristics, we found that 6.3 percent of dually eligible beneficiaries switched, compared to 4.5 percent of beneficiaries who were not dually eligible (appendix exhibit A2).15 Additionally, 7.9 percent of high-need beneficiaries switched, compared to 4.6 percent of non-high-need beneficiaries. Of those who switched, 40.0 percent of high-need beneficiaries and 43.5 percent of dually eligible beneficiaries reenrolled in MA in the following year, while 42.2 percent of non-high-need beneficiaries and 41.4 percent of non-dually eligible beneficiaries reenrolled, respectively (exhibit 2). Enrollees in rural ZIP codes had a 7.2-percentage-point lower probability of reenrolling. A 10 percent increase in state MA penetration was associated with a 4.7-percentage-point increase in the probability of reenrolling in the next year (appendix exhibit A5).15

Exhibit 2. Adjusted percent of beneficiaries who reenrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2016 after having switched to traditional Medicare in 2015, by beneficiary characteristics.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2014–16 from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. NOTES The percentages shown are means across states, adjusted for patient characteristics using a linear probability model. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. All differences are significant (p < 0:001) using robust standard errors. Dual eligibility refers to eligibility for and enrollment in both Medicare and Medicaid.

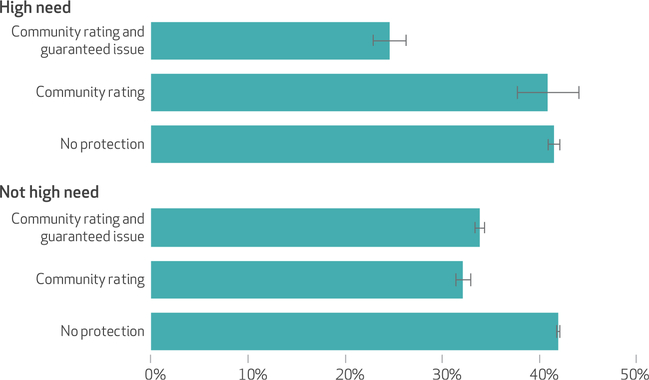

Non-high-need enrollees in states with both guaranteed issue and community rating were 8.0 percentage points less likely to reenroll in MA, compared to enrollees in states without those protections (exhibit 3). In states without the protections, high-need enrollees had a 16.9-percentage-point higher probability of reenrolling than they did in states with both protections. The interaction term between high-need status and state protections was significant (p < 0:01), which indicates that the difference in state protection status is disproportionally associated with reenrollment among high-need enrollees. There was no significant difference in reenrollment between states with only community rating and those with no protection.

Exhibit 3. Adjusted percent of beneficiaries who reenrolled in Medicare Advantage in 2016 after having switched to traditional Medicare in 2015, by beneficiary high-need status and state community-rating and guaranteed-issue status.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data for 2014–16 from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. NOTES The percentages shown are means across states, adjusted for patient characteristics using a linear probability model. The error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. “Guaranteed issue” is when a state mandates that coverage be offered despite the presence of a preexisting condition. “Community rating” is when people with a preexisting condition cannot be charged a higher premium than others of the same age. “No protection” refers to states with neither guaranteed issue nor community rating. Minnesota, Vermont, and Washington have community rating alone. Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, and New York have both community rating and guaranteed issue. The difference between community rating and guaranteed issue and nonprotection status is significant for both high-need and non-high-need enrollees (p < 0:01). The interaction between state protection status and high-need status is also significant (p < 0:01). A separate model was fit for guaranteed issue and for community rating.

There was substantial state variation in reenrollment in MA, ranging from 5.8 percent in Connecticut to 74.3 percent in Utah (appendix exhibit A4).15 In all seven guaranteed-issue or community-rating states, reenrollment was significantly lower among high-need people, while in most states the difference between people with and without high need was not significant. In a sensitivity analysis that examined only states in the Northeast, where most states with protections are located, we found that these results held. The sensitivity analysis and full model outputs are in the appendix.15

Discussion

High-need and dually eligible enrollees switched from MA to traditional Medicare at higher rates and were less likely to reenroll in MA in the following year, compared to non-dually eligible and non-high-need enrollees. In states with consumer protections for guaranteed issue and community rating for Medigap insurance, high-need beneficiaries were substantially less likely to reenroll in MA, compared to high-need beneficiaries in states without those protections. Unexpectedly, we found that switching to traditional Medicare was more common in states that lacked guaranteed-issue or community-rating policies.15 This finding may suggest that beneficiaries who exit MA may be unaware of the lack of guaranteed issue and community rating of Medigap in these states. However, our study could not identify the mechanisms for this phenomenon.

MA enrollees might not realize that in most states, if they switch to traditional Medicare, they might not be able to get Medigap coverage. Enrollees with higher health care needs are both more likely to leave MA and more likely to be denied access to Medigap coverage. These enrollees may then face out-of-pocket payments in traditional Medicare without any limits, causing financial burden and prompting reenrollment in MA. While we cannot demonstrate a causal link between a state’s consumer protections for preexisting conditions and Medigap reenrollment, we identified an association between living in a state with protections that require guaranteed issue of Medigap coverage and remaining in traditional Medicare after exiting MA. We did not find large differences between states with community rating only and those without community rating. It may be that guaranteed issue is more important to ensure access to enrollment for beneficiaries. The states with community rating only may also have heterogeneous MA markets that may differ from those of other states.

We found that dually eligible enrollees had higher levels of switching from MA than non-dually eligible enrollees. However, 43.5 percent of them also chose to reenroll in the program after a switch. As people who are fully dually eligible do not face cost sharing in traditional Medicare, reenrollment in this population may be driven more by preferences than by cost constraints.

Recent changes in the Medigap market have granted Medigap plans more flexibility in the benefits that they offer and allow some Medigap plans to institute network requirements.16,17 However, if beneficiaries with greater health care needs are unable to enroll in these plans, then the potential of these benefits may be limited.

Medicare beneficiaries with complex care needs often face a higher burden of costs and may benefit from a greater continuity of care. In most states these enrollees may face significant barriers to enrollment in Medigap that may increase their exposure to high out-of-pocket spending and lead to disruptions in the continuity of care if they need to switch between MA and traditional Medicare. To address these concerns, more states could pass legislation to require guaranteed issue regardless of preexisting conditions or Medigap insurance or require community rating of premiums. These protections were required nationally for commercial insurance plans under the Affordable Care Act but were not extended to Medigap plans. Additionally, in most states, even if an enrollee with a preexisting condition such as cancer does enroll in Medigap, they might not be able to receive any benefits to cover this condition during the first six months of enrollment. Shifting Medigap enrollment protections to be in line with those afforded in MA enrollment and under the ACA could therefore alleviate the financial burden faced by Medicare beneficiaries with complex conditions. It is important to note that even if an enrollee has access to a Medigap plan, premiums are substantially higher in Medigap than in MA, which may place further limits on Medicare choices for lower-income enrollees. Furthermore, outside of several surveys, there are currently limited data available in public or research files to determine whether a given enrollee is enrolled in a Medigap plan. As a result, there are no national individual-level administrative data that can be used to determine the types of people who enroll in Medigap and what barriers enrollees might face.

Conclusion

We found that in states without consumer protections in the Medigap market, high-need MA enrollees had a 16.9-percentage-point higher reenrollment rate in MA after switching from it to traditional Medicare, compared to high-need enrollees in states with guaranteed issue and community rating for Medigap. Policy makers should consider consumer protections in the Medigap market that ensure adequate access to coverage for high-need Medicare beneficiaries.▪

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this article was presented at the AcademyHealth National Health Policy Conference in Washington, D.C., February 4, 2019. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (NIA) (Grant No.P01AG027296). David Meyers was additionally supported by an NIA T32 predoctoral training grant. Vincent Mor is chair of the Independent Quality Committee at HCR ManorCare; chair of the Scientific Advisory Board and a consultant at NaviHealth, Inc.; and a former director of PointRight, Inc., where he holds less than 1 percent equity.

Contributor Information

David J. Meyers, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health, in Providence, Rhode Island..

Amal N. Trivedi, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health..

Vincent Mor, Department of Health Services, Policy, and Practice at the Brown University School of Public Health..

NOTES

- 1.Boccuti C, Jacobson G, Orgera K, Neuman T. Medigap enrollment and consumer protections vary across states [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. July 11 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medigap-enrollment-and-consumer-protections-vary-across-states/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neuman P, Jacobson GA. Medicare Advantage checkup. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(22):2163–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cooper AL, Trivedi AN. Fitness memberships and favorable selection in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):150–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobson G, Damico A, Neuman T. A dozen facts about Medicare Advantage [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. November 13 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/a-dozen-facts-about-medicare-advantage/ [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Trends in Medigap enrollment, 2010 to 2015. MedPAC Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2017. February 13 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.medpac.gov/-blog-/trends-in-medigap-enrollment-2010-to-2015/2017/02/13/trends-in-medigap-enrollment-2010-to-2015 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang JT, Jacobson GA, Neuman T, Desmond KA, Rice T. Medigap: spotlight on enrollment, premiums, and recent trends [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2013. April [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/04/8412-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahman M, Keohane L, Trivedi AN, Mor V. High-cost patients had substantial rates of leaving Medicare Advantage and joining traditional Medicare. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(10):1675–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Q, Trivedi AN, Galarraga O, Chernew ME, Weiner DE, Mor V. Medicare Advantage ratings and voluntary disenrollment among patients with end-stage renal disease. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(1): 70–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg EM, Trivedi AN, Mor V, Jung HY, Rahman M. Favorable risk selection in Medicare Advantage: trends in mortality and plan exits among nursing home beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(6): 736–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meyers DJ, Belanger E, Joyce N, McHugh J, Rahman M, Mor V. Analysis of drivers of disenrollment and plan switching among Medicare Advantage beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2019. February 25 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLaughlin CG, Chernew M, Taylor EF. Medigap premiums and Medicare HMO enrollment. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1445–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rice T, Snyder RE, Kominski G, Pourat N. Who switches from Medigap to Medicare HMOs? Health Serv Res. 2002;37(2):273–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bélanger E, Silver B, Meyers DJ, Rahman M, Kumar A, Kosar C, et al. A retrospective study of administrative data to identify high-need Medicare beneficiaries at risk of dying and being hospitalized. J Gen Intern Med. 2019. January 2 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS manual system: pub 100–04 Medicare claims processing [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2007. July 20 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R1311CP.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 16.Hawkins K, Parker PM, Hommer CE, Bhattarai GR, Huang J, Wells TS, et al. Evaluation of a high-risk case management pilot program for Medicare beneficiaries with Medigap coverage. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18(2):93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moeller P Standard Medigap plans are learning some new tricks. PBS NewsHour [serial on the Internet]. 2017. September 13 [cited 2019 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/economy/standard-medigap-plans-learning-new-tricks [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.