1. Biologicals and new treatment options of stratified medicine

The design of biological pharmaceutics is based on a profound mechanistic understanding of disease processes. Generally they consist of large-molecular substances that were synthesized by living organisms. Most commonly, biologics mediate their effects via selective binding of cytokines or their specific receptors 1 . In this introduction, first development and classification, biochemical specifics, immunological effects, current trends and finally characteristic side effects will be described.

1.1 Biological medical substances: definition

The European Medical Agency (EMA) defines biologics (or biological medicinal products) as biopharmaceutical medicinal products that are applied in vivo as biological medicinal substance and will usually be applied as therapeutic agents. Furthermore, they include biotechnologically produced active substances, e. g., therapeutic antibodies and recombinant proteins but also vaccines and allergens, blood and plasma products as well as recombinantly produced alternatives 2 . In the daily language of life-science and medicine, the term of biologics was established mainly for therapeutic antibodies and rarely also for recombinant therapeutic proteins.

1.2 Development and historical milestones

Based on mechanistic studies, molecular biology and genetic basic research, therapeutic target structures were developed in the 1990ies and validated in animal models as well as in human translational models before clinical testing. By means of a procedure developed by Milstein and Köhler (Nobel Prize for Medicine in 1984) 3 , therapeutic antibodies may be produced by immortalized hybrid B cells from myeloma cell cultures for nearly every target structure. Further biotechnological procedures allowed synthesizing, validating, and approving new biopharmaceutics, e. g., recombinant insulins (first approval by the FDA in 1982) 4 . This development was further fueled by the transfusion scandals of the 1980ies, accidental transmission of HIV or HCV to hemophilia patients and the contamination by Creutzfeld-Jakob in the context of pituitary extracts for growth hormone substitution. Also recombinant coagulation factors 5 6 and growth hormone (approval by the FDA in 1985) 7 8 were produced by means of biotechnology.

1.3 First biologicals, hybrid molecules, and concept-related advantages and disadvantages

In particular for usage in oncology and autoimmunity, promising monoclonal neutralizing antibodies have been constructed, fusion proteins with binding capacity (etanercept), with or without intrinsic activity (IL-4 mutein), receptor antagonists, bi- and trispecific antibodies that may bind different target structures and at the same time activate for example T cells. In the former dual immunological conception of Th1/Th2 inflammations 9 10 , recombinant cytokines were intended to restore the inflammatory balance, e. g., by application of recombinant IL-12 in cases of asthma 11 or e. g., IL-10 12 and IL-11 13 for psoriasis. In contrast as for example to interferon therapy for treatment of multiple sclerosis or viral hepatitis, those trials did not reach their endpoints consistently and sometimes showed relevant side effects. Hence, these therapeutic approaches have not been pursued.

Beside the possible variety of biologically potentially applicable therapeutic proteins, at the same time a high range of biotechnological expression systems has been developed 14 . After initial prokaryotic systems, successively eukaryotic expression systems have been developed that made available also larger and glycosylated proteins with complex tertiary and quaternary structure in reproducibly high and therapeutic quality. Even with regard to optimization of therapeutic antibodies to target epitopes and the development of extraction processes, enormous pioneering work was done 15 16 17 18 19 .

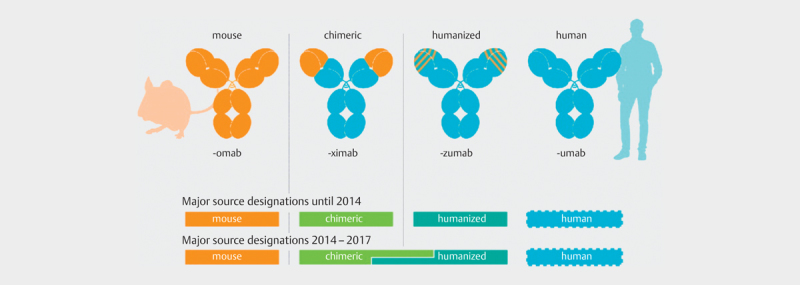

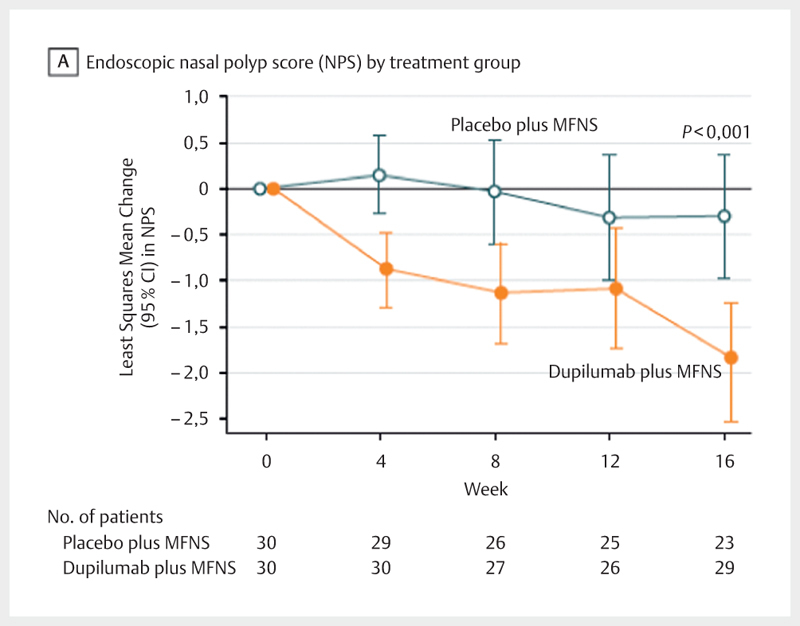

While biologically active human insulin has a molecular weight of approx. 5,000 Daltons, the growth hormone somatotropin has a molecular weight of about 22,000 Daltons 20 . A monoclonal antibody has about 150,000 Daltons; for comparison, the molecular weight of acetylsalicylic acid is approx. 180 Daltons. The first therapeutic antibodies were developed as chimeric proteins with relatively high murine or other xenobiological portions and increasingly humanized. This led to a significantly improved tolerance, effectiveness, and safety for the patients. This development is also reflected in the nomenclature of the biologics: The anti-CEA antibody arcitumomab approved in 1996 was only murine, the therapeutic TNF-α antibody Infliximab, approved in 1999, was a chimeric antibody, the herceptin antibody trastuzumab and the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab were humanized antibodies, and the TNF-α antibody adalimumab was completely human ( Fig. 1 and 21 ).

Fig. 1.

Depiction of the international non-proprietary names (INN) for the development of humanized and human antibodies (Creative Common Licence, cited from 21 , Paul W.H.I. Parren et al., 2017, mABS).

1.4 Immunogenicity

Beside an intended immunological effect, usually an undesired immunological reaction occurs on biologically active and mostly exogenous substances in the recipient or host organism, which is called immunogenicity. The murine or xenobiological portions on the one hand and the glycosylation pattern on the other hand determine significantly the immunogenicity of the active biological substance. This leads to for example ADAs (anti-drug antibodies) that at best are neutralizing and lead to ineffectiveness of the applied biological drug, but also potentially to immunological phenomena such as autoimmune hemolysis, cytokine release syndrome, mast cell activation, immune complex hypersensitivity and serum disease. Examples in this context are the relatively high rates of reactions against infliximab or rituximab, which consist of a significant murine proportion 22 23 . Finally, those biologically active substances are complex, large, biotechnologically produced pharmaceutics. Methodological details during production as well as cooling, light, pH, transportation, and application may lead to small molecular changes with potential alterations, such as loss of effectiveness, molecular aggregates, and increased immunogenicity. Furthermore, cross-reacting epitopes may lead to fatal anaphylaxis, especially when the antigens share amino acid sequences with IgE epitopes, e. g., cetuximab.

1.5 Anaphylaxis against biologics: the example of cetuximab

In 2003, the EGF receptor antibody cetuximab was approved in the USA (FDA) and in 2004 in Europe (at that time: EMEA), first for the treatment of advanced colon cancer. Since the publication of pivotal trials on combination therapy, it is also applied for advanced head and neck carcinomas 24 25 26 . Already during approval studies in the early 2000ies, regional differences became apparent in the USA with regard to the incidence of anaphylactic reactions. In 2007, O’Neil could show that the first administration of the drug had a global probability of less than 3% to develop anaphylactic reactions. In the middle southeast of the USA, however, e. g., in Virginia, this rate amounted to up to 20% 27 28 . This reaction is of completely different nature compared to the relatively frequent cutaneous reactions 29 . In 2013, Platt-Mills and colleagues could clarify the mechanism of sensitization and association with tick bites and allergy against red meat 30 31 . The regional distribution of a tick species, the so-called lone-star tick, leads to the development of galactose-alpha-1.3-galactose (alpha-GAL) specific IgE antibodies after tick bite. Alpha-GAL is a nearly ubiquitously expressed oligosaccharide of glycoproteins of the cell surface in all non-primate mammalians, prosimians, and new world monkeys. In primates (old world monkeys and humans), about 1% of the circulating IgG pool correspond to alpha-GAL antibodies, and alpha-GAL is a relevant biological obstacle of a simple xenotransplantation 32 . Since 2014, commercial test systems are available that can be applied to determine specific IgE against alpha-GAL. The exclusion of sensitization to avoid anaphylactic reactions prior to application of humanized antibodies can be life-saving for patients with high-risk profiles. High-risk patients are individuals with many tick bites (e. g., forestry professionals), with cat allergy, and pork-cat syndrome 33 . The determination of alpha-GAL in this high-risk cohort is a showcase of personalized medicine according to the WHO definition: avoiding side effects by specific characterization of patients.

1.6 Intended immunological effects and temporary immune phenomena

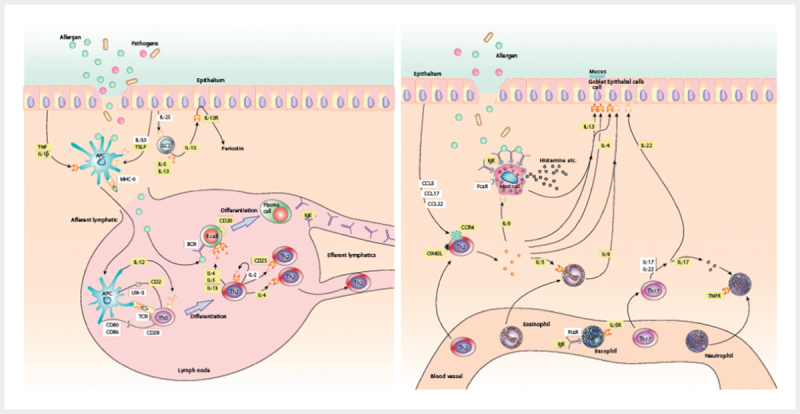

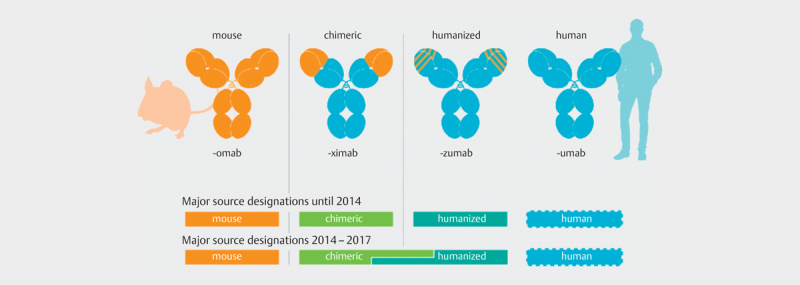

The effect that is inherent to most therapeutic antibodies is the impact on immunological processes, e. g., by antagonizing or eliminating messenger substances of the inflammation cascade (e. g., anti TNFα, anti-IL-1, anti-IL-5) ( Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

On the left, a mucosal immune reaction against allergens under the influence of further pathogens in the sense of sensitization. Hereby, alarmines (IL-25, IL-33, and TSLP), proinflammatory cytokines (e. g., IL-4, IL-5, IL-13), antigen-presenting cells (APC), innate lymphoid cells (ILC) as well as T helper cells and B cells are depicted. On the right, the situation of a re-exposition is displayed involving mast cells as well as cellular late stage reaction with the influx of eosinophilic granulocytes and T helper cells under secretion of multiple cytokines and use of intercellular signaling pathways (according to 1 , Boyman et al., Allergy, 2015). The mechanistic characterization of these different inflammatory pathways allows a targeted therapy by e. g., therapeutic antibodies for the processes in the epithelium as well as in the subepithelial stroma (licensed by RightsLink/John Wiley and Sons).

The transition from undesired to intended immunological effects is fluid. Bi- or even trispecific antibodies such as for example catumaxomab that are applied for advanced oncologic diseases such as malignant ascites and hereby bind to the Fc receptor and to the activating T cell receptor CD3 and to the epithelial cell adhesion molecule EpCAM, activate the immune system in a targeted way and beside the antineoplastic main effect, they generate an inflammatory co-activation by cytokine release, however, with significant side effects.

Another intended effect is the inhibition of regulatory immunological processes on T cell level in vivo by checkpoint kinase inhibitors such as the inhibition of CTLA-4 by ipilimumab as well as inhibition of PD-1 by nivolumab or pembrolizumab (overview to be found in 34 ).

In some cases, autoimmune phenomena or side effects caused by biologics, as for example rituximab, are causally co-treated de facto on B cell level by further continuously administering the same drug 35 .

1.7 Biosimilars

The complexity and size of the molecules, their different expression systems and production processes do not allow real generics of biological products even after expiration of patent protection. Therefore, the concept of biosimilars was developed 36 . Ledford 37 defined biosimilars as an inexact copy of a reference substance. The major question from the immunological point of view is: How similar do biosimilars have to be compared to the original substance, or more bluntly: how similar is similar? The instrumental definition of the EMA considers a biosimilar as highly similar to the original substance in all relevant aspects, i. e., effective mechanism, safety, production process. In the European Union, at least one clinical trial is required from the manufacturers of biosimilars to document the biological equivalence which implicates a relevant switchability of the biosimilar with the originator substance. In addition, extensive immunogenicity data and data on the production process have to be made available. From this regulatory context it is mandatory for the manufacturers to commit themselves to permanent pharmacovigilance and extensive quality management. If the biological equivalence is confirmed, the biosimilar may be introduced onto the market under the INN name. Based on this certified equivalence, the approval authorities can allow an extrapolation, i. e., based on the available data, it is assumed that the biosimilar works also in all other approved indications, equivalently to the originator substance 38 39 . The switchability and the extrapolation are the aspects that are controversially discussed among Immunologists because the majority of patients with autoimmune diseases receive this medication in addition to other immunomodulatory treatments. Thus, the evaluation of the induction of ADAs and the switchability are particularly complex. On the basis of the data that are currently available for the approval authorities, however, the possibility of switching the approved biosimilars is assumed 38 . Pharmaceutics that are very similar to an originator substance but that do not pass this regulatory process (e. g., in the EU controlled by the EMA, in the USA by the FDA), are called intended copies. Those drugs can be purchased for example in emerging countries but they are not approved in the EU.

Biobetters are substances that dispose of more favorable properties for therapy due to small selective changes leading to altered physico-chemical properties, changed binding capacities, or modified degradation or clearance. One example in this context are insulins that have a longer-lasting effects or pegylated antibodies that increase for example the bio-availability due to binding with polyethylene glycol (PEG) 40 .

1.8 Small molecules and DNAzyme

Those pharmaceutics have also been developed with a rational design based on mechanistic studies, but contrary to prevailing assumption, they are no biologics. Many of the small molecules often act as tyrosine kinase inhibitors and require certain genetic subtypes or expression of markers for successful therapy. In this way, they are of particular significance for precision medicine. However, because of their physico-chemical properties, their approach is completely different and so they are typical pharmaceutics, generally with a size of up to 800 Daltons. They have been established especially in the field of clinical oncology. Activating EGFR mutations are found in 10–15% of the patients with lung cancer (e. g., non-smokers, adenocarcinomas) that are therefore suitable for treatment with gefitinib 41 . Inhibitors of janus kinases (so-called JAK inhibitors), which mediate the activity of cytokine receptors as cytoplasmatic tyrosine kinase, can be applied as e. g., the small molecule tofacitinib in autoimmune diseases 42 and possibly also as supporting immune modulator in the allergen specific immune therapy 43 . As selective chloride channel enhancers, the substances ivacaftor and lumacaftor are a new and promising therapeutic option for patients with cystic fibrosis and a delta F508 mutation of the CFTR gene and lead to a reduction of pulmonary exacerbation 44 45 .

A topical effect induced by DNAzymes that are targeted for example effectively and specifically against the Th2 transcription factor GATA3 and thus inhibit all downstream immuno-pathological Th2 reactions 46 is also mechanistically elegant but according to the definition they are no biologics.

1.9 Costs

The global market for biologics in 2020 is estimated to amount to 350 billion Euro 47 . In 2016, in Germany biological drugs were prescribed for around 6.4 billion Euro within the statutory healthcare system, corresponding to 19% of the overall turnover of all drugs and 2.5% of all prescriptions 49 . Possible cost reductions by biosimilars are estimated to approx. 20–30% because the regulatory obstacles for approval and pharmacovigilance are very high. Currently, 28 biosimilars are approved for application in the EU. It should be noted that cost reductions by competition are possible in particular where several biosimilars are approved whereby the market shares of biosimilars do not necessarily correlate with the prizes 49 .

This calculation however does not include the increasing incidence of prescriptions because the multitude of new molecules as well as the increasing number of indications and a corresponding market penetration can be observed. For the EU and the USA, IMS Health expects possible economies of 50–100 billion US$ between 2016 and 2020 by application of biosimilars.

2. Rhinology: Epidemiology and pathophysiological concepts

Rhinology deals with diseases of the outer and inner nose, the paranasal sinuses as well as the frontobase and their surgical and conservative therapy. As outpost and door of the airways, the nose in this context is an organ that has esthetic, functional, and immunological tasks and works as sensory, filter, and reaction organ 50 .

2.1 Physiology of the nasal mucosa and the integrated mucosal immune system

The nasal mucosa is a first-line of defense. The preservation of the physical integrity by the respiratory mucosa as active and passive barrier, which is at the same time the location of innate and adaptive immune response, the complex function of the mucociliary clearance, the permanent confrontation with particulate and soluble substances such as antigens, allergens, and pathogens result in the according nosology and pathology known to every ENT specialist 51 . Rational understanding of the inflammatory and protective mechanisms led to the definition of new therapeutic target structure and concepts (see review article 52 ).

The respiratory epithelium that is found in the respiratory region of the nose and the paranasal sinuses as well as partially in the nasopharynx is a pseudostratified epithelium. The ciliary function contributes to transporting mucus, possible noxious substances, and particles that have been inhaled in direction of the ostia or the mouth, respectively, whereby pathologies of the ciliary apparatus fundamentally alter the physiology of the airways 53 . The cilia have multiple functions; it could be shown among others that they are chemosensory. At the same time, the intact respiratory epithelium is the basis for functionally intact defense 54 55 . At transition points to enhanced mechanical use, e. g., in the pharynx, the epithelium merges into a stratified squamous epithelium. In this epithelium, goblet cells are found that produce mucins. These mucins play an elementary role in the unspecific mucosal immunity; they contribute to the barrier function, interact in an antimicrobial way with multiple antimicrobial peptides and defensins 56 , develop a highly flexible and complex mucin-interactome 57 , and act synergistically with inflammatory cytokines, e. g., IL-1β 58 . Submucous glands produce nasal lining secretions, these consist of both, a transsudative (vasomotor) and a secretory layer. In the luminal secretory layer, substances with an unspecific antimicrobial activity are found, such as e. g., lysozyme, lactoferrin and defensins as well as adaptive mucosal antibodies of the IgA type (IgA1 and IgA2) 59 and the secretory component, which ensures the biostability of secretory mucosal IgA 60 . In addition, also IgM and IgG are found. IgA is induced by interaction with commensals and external influences and may additionally neutralize exotoxins as well as pathogens and transport sIgA commensals through the epithelium in luminal direction. Mucosal IgA has multiple functions of immune exclusion due to various affinities 61 and thus it contributes relevantly to the mucosal immunity of the respiratory mucosa and determines an active antigen-specific protection at this important external border of the upper airways, which is the most exposed external surface of the human body in relation to the covered surface.

Beside protective humoral mechanisms, also a synergistically acting cellular compartment is found in the upper airway mucosa. This involves tissue macrophages, eosinophilic, neutrophilic granulocytes, basophils, and mast cells, that act according to stimuli and pathology. Intraepithelial lymphocytes of the CD4 and CD8 type act in an antigen specific and adaptive manner. Together with submucous lymphocyte infiltrates of the lamina propria and special, functionally adapted NALT regions with adapted M cells and dome areas, γδT cells 62 , innate lymphoid cells (ILC) 63 as well as NKT cells may induce tolerogenic, allergic, or cytotoxic immune responses 64 65 . Furthermore, the pharyngeal tonsil, which usually should involute by school age, is part of the integrated mucosal system in the nasopharynx. Beside T cell infiltrates in e. g., allergic rhinitis or chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, also areas of local IgE production by B cells 66 as well as dendritic cells 67 68 exist. Together with macrophage-like dendritic CD11+CD14+CD68 cells, those professional, antigen presenting, partly immature CD1+CD11+ cells form a dense network for regulation of adaptive immune responses 69 and express especially in atopics the highly affine IgE receptor FcεRI as well as costimulatory molecules such as CD80, CD86, and CD40 70 . There is evidence, that apart from lymphoepithelial areas respiratory epithelium adapts functionally to existing immunological conditions. Hereby, it is modified by inflammatory stimuli such as e. g., IFNγ or IL-4 in its transcriptome and consecutively functional properties. This leads for example to a defective barrier function due to reduced expression of tight junction proteins 71 . However, the epithelium is acting as an immunointerface in the initiation and maintenance of e. g., allergic inflammation. This involves inflammatory cytokines such as TSLP 72 , IL-25 73 , or IL-24 74 and epithelial alarmins such as IL-33, that contribute mucosal inflammation 75 . In the full picture of chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis of the western subtype, predominantly a type 2 inflammation is found with eosinophilic infiltrates, local expression of IL-5, IL-13, and the presence of IgE 76 77 78 (see also chapter 2.4 in 52 ).

2.2 United Airways

The functional and physiological connection of the upper and the lower airways is a daily experience in the treatment of ENT patients. The association of clinically severe courses of e. g., chronic sinusitis with chronic bronchitis and asthma or allergic rhinitis and asthma can be identified in daily practice as well as in the epidemiological perspective.

In 2002, a prospective longitudinal population cohort from Denmark convincingly revealed for the first time the correlation between allergic rhinitis and allergic asthma in people suffering from allergy to pollen 79 . Previous trials, even performed in well-structured national cohorts 80 were able to show associations but they used non-adjusted datasets.

In 2008, Shaaban and colleagues 81 examined more than 6,460 patients in a European longitudinal cohort study in 14 European countries that patients with allergic rhinitis had a approx. four-fold risk to develop bronchial asthma within the observation period of nearly 9 years. The adjusted relative risk amounted to 3.53 (95% CI: 2.11–5.91) for allergic rhinitis and – that is also a relevant result – to 2.71 (95% CI: 1.64–4.46) for non-allergic rhinitis.

Even in cases of chronic rhinosinusitis, the association with asthma has been investigated epidemiologically 82 and mechanistically apart from the typical Vidal or Samter triad. Depending on the sample, the percentage of asthmatic patients in the patient cohort with CRS amounts to 25–70% 83 84 . A research team from the UK analyzed a clinical cohort with 57 patients suffering from CRSwNP with regard to pulmonary function, bronchial hyperreactivity, and exhaled nitrogen monoxide (FeNO). In this context, 3 clinical groups with different phenomena could be identified. However, these groups were not different regarding the severity of their nasal symptoms 85 . Not only in cases of allergic asthma, but also in cases of non-allergic asthma and COPD, an association to pathologies of the nose and the paranasal sinuses could be demonstrated. Patients with non-allergic asthma and COPD had a higher symptom burden in the validated SNOT-20 questionnaire as well as increased concentrations of inflammatory cytokines in nasal lining secretions, e. g., IFNγ and G-CSF, but also eotaxin and MCP-1 86 .

The didactically and functionally interesting concept of the “atopic march” 87 fits well in such most likely T cell mediated disease concepts based on the assumption of antigen-specific inflammatory T cells migration.

In the early 2000ies, Braunstahl conducted segmental-bronchial and nasal allergen challenges and could show that a segmental bronchial allergen provocation leads to infiltration of IL-5 producing cells and of eosinophils in the nasal mucosa 88 . Nasal allergen provocation again leads to increased expression of epithelial (ICAM-1) and vascular (VCAM-1) adhesion molecules in the bronchial mucosa correlating with the number of locally expressed eosinophils 89 . Also infiltrates with basophils and mast cells could be revealed 90 . Despite the elegant study design, the major weakness of those studies is that the cellular source of the pro-eosinophilic IL-5 was neither functionally nor morphologically determined.

The interactions between the upper and lower airways are far from being only based on immunological mechanisms. The research team of Baroody and Naclerio could show that the nasal mucosa of patients suffering from allergic asthma can only poorly condition the air, i. e., warming it up and moistening it 91 92 .

2.3 Entities and epidemiology of diseases of the nasal mucosa and the paranasal sinuses

2.3.1 Infections

The most frequent origin of upper airway diseases is an acute viral infection with respiratory viruses; primarily bacterial rhinosinusitis is comparably rare. The etiology of chronic rhinitis and chronic rhinosinusitis is complex and it is mostly unclear if in the sense of “first hit hypothesis” at the beginning of the inflammatory cascade viral, fungal, or bacterial infections must be assumed. Also the role of allergies, local or systemic, is not finally investigated.

The common viral cold, coryza, is the most frequently occurring infectious disease at all. Because of difficult distinction, Eccles considers it more as a cultural concept than a clearly defined clinical entity 93 . Meanwhile, 99 serotypes of human rhinoviruses have been phylogenetically examined 94 and completely sequenced 95 . The variability of those viruses is very high and thus rather difficult for the immune system: beside the variety of antigens and the specific virulence of the pathogens, also the pathogen-host interactions determine the pathogenicity and penetrance. One example is the genetic association of bronchial rhinovirus infections and childhood asthma 96 .

In vitro, a Th2 microenvironment leads to an increased infection rate with human rhinoviruses under the influence of the cytokine IL-13 by upregulating the epithelial adhesion factor ICAM-1 97 . In patient cohorts, this supposedly simple correlation remained unconfirmed up to now. However, it could be revealed that children with asthma have a clearly longer-lasting postviral hyperreagibility of the airways 98 . An afebrile rhinovirus infection may become an exacerbation of chronic rhinosinusitis or exacerbated asthma 99 100 . Probably, rhinoviruses are responsible for about 50% of respiratory infections, beside influenza, adenoviruses, coronaviruses, and RSV (respiratory syncytial virus). In particular influenza viruses are accessible for vaccination strategies 101 .

The early infection with RSV is also considered as risk factor for the development of allergic asthma 102 103 . Developments of vaccination strategies for coronaviruses and RSV are relevant especially for high risk populations in the sense of stratified prevention. For prophylaxis of RSV pneumonia in susceptible children (e. g., premature children), the biologic pavilizumab is available as secondary preventive, passively immunizing antibody (Guideline in Pediatrics 104 ).

The role of viral infections of the upper airways regarding genesis and exacerbation, is currently only insufficiently understood; in vitro models show in particular an induction of co-stimulating signals 105 in the epithelium and for example the synergistic impact in the Th2 microenvironment on pendrins, which contribute among others to dyscrinia and secretion in cases of chronic rhinosinusitis 106 .

Acute bacterial superinfections of viral sinusitis occur in about 2% of uncomplicated cases 107 108 109 . The most frequent pathogens for simple acute bacterial rhinosinusitis without preexisting chronic rhinosinusitis are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catharrhalis, and Staphylococcus aureus. In the context of preexisting infection with rhinoviruses, an increased adhesion of different bacteria could be shown among others for Staphylococcus aureus 110 .

Under the influence of IL-4, an altered function neutrophil granulocytes has been described in atopy 111 , in that bacterial superinfection can be easily explained mechanistically in the model. The microbial interactions in chronic rhinosinusitis, however, are complex. On one hand, biofilms play a relevant role 112 , on the other hand, the microbiome in the investigated patient population is probably iatrogenically altered and limited in its diversity in favor of single species. So Abreu et al. revealed a loss of lactic acid bacteria in favor of Corynebacterium tuberculostearium 113 . Choi and colleagues could identify colonization with Staphylococcus aureus 114 . Since especially severe cases of CRS with nasal polyposis are associated with the presence of specific IgE against S. aureus enterotoxin and also the colonization of the mucosa with S. aureus is accompanied with nasal polyposis, tissue eosinophilia, and a Th2 microenvironment 115 , the question of cause and effect has to be asked. Actually, S. aureus IgE is also found in severe adult asthma 116 and the involvement of superantigens in atopic eczema is documented clinically as well as experimentally 117 . Hence it is very difficult to estimate the role of a complex microbiome in these heterogenic cohorts that are often pretreated with antibiotics. Data on the exacerbation by bacterial superinfection in CRS are incomplete. Therapeutic microbiome interventions, e. g., as microbiota transfer may be promising tools in personalized medicine 118 , however, this topic has not been published in rhinology up to now.

2.3.2 Tobacco smoke

In epidemiological studies, tobacco smoke could be consistently shown as independent risk factor for sinusitis (OR 1.7: 95% CI: 1.6–1.9) 119 , an overview is found in Beule’s contribution 120 .

2.3.3 Allergies

Worldwide, between 10 and 40% of all people are affected by allergic rhinitis 121 122 . Since many years, the epidemiology of allergic rhinitis is investigated on the basis of consistently structured international patient cohorts, mainly according to the ISAAC standard (International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood 123 ), that are further supported by population-based representative cohort studies. Unanimously, the picture of a globally increasing prevalence of respiratory allergies developed since the 1980ies that at least in Europe reached a high-level plateau in the last years. Approx. 500 million people probably suffer from allergic rhinitis worldwide; the socio-economic consequences are enormous (see overview in 122 ). In Germany, the data of the study on adult health (DEGS1) reveal a lifetime prevalence for allergic diseases of about 30% 124 . In the context of population-related sampling with more than 7,000 blood tests of adults, at least 48% of the patients had allergic sensitization, hereby a total of 33.6% of the participants were sensitized against aeroallergens 125 . These percentages were confirmed by the Robert Koch Institut (RKI) in the general study on adult health in Germany from 2014 (“Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland 2014” (GEDA study) enrolling 23,000 randomly selected individuals. The RKI reports about an “allergy tsunami”: the 12-month prevalence for allergic diseases amounted to approx. 28% 126 . In the USA, also up to 30% of the population suffer from allergic rhinitis, about 60% of them cannot adequately control their symptoms by treatment with antihistamines or topical steroids 127 . In Germany, only about 10% of the patients are treated in compliance with the according guidelines 128 . The only causal therapeutic option for treatment of allergic rhinitis is specific immunotherapy 122 129 , which shows an excellently documented clinical effectiveness and safety as subcutaneous 130 as well as sublingual immunotherapy 131 132 133 . Furthermore, its effect is downstream preventive on the development of allergic bronchial asthma 134 135 136 (see also chapter 2.5).

2.3.4 Chronic rhinitis

Comparably reliable epidemiological data on chronic rhinitis in adolescents are found due to the Isle of Wight birth cohort that is also the association of different clusters on the risk to develop asthma 137 . It is not easy to clinically and terminologically distinguish chronic rhinitis as differential diagnosis from chronic rhinosinusitis. Recent reports define the specific consensus, however, in contrast to allergic rhinitis sound data are not available 138 139 . In the context of non-allergic chronic rhinitis, several subtypes are defined such as non-allergic rhinitis with eosinophilia (NARES) 140 , hormonal rhinopathy, rhinitis with neurogenic inflammation 141 (which is possibly a specific endotype, see chapter 2.4), and idiopathic rhinitis (which is still called vasomotor rhinitis in English-speaking countries). Those subtypes can be treated selectively with topical nasal steroids, e. g., ipratropium bromide (off-label use in Germany) or capsaicin (if available).

2.3.5 Chronic rhinosinusitis

The category of chronic rhinosinusitis defines inflammatory diseases of the nose and the paranasal sinuses with durations of more than 12 weeks. The EPOS2 guideline from 2012 107 defines chronic rhinosinusitis as a disease of the nose and the paranasal sinuses of at least 12 weeks duration characterized by more than 2 of the following symptoms: a) nasal obstruction, b) rhinorrhea, c) pressure sensation or facial pains, d) hyposmia or anosmia, while either at least nasal obstruction or rhinorrhea should be present as obligatory symptoms. Clinically, either endoscopic signs of nasal polyposis, mucopurulent discharge from the middle nasal meatus and/or CT morphological signs of mucosal alterations in the osteomeatal unit or the paranasal sinuses should be found. This definition taken from the European position paper has been increasingly accepted in the last years. Furthermore, independent from the etiology and pathogenesis of the disease, chronic rhinosinusitis was classified into chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP) and chronic rhinosinusitis without (lat.: sine) nasal polyposis (CRSsNP) 107 142 .

It is difficult to perform methodically and regionally consistent evaluations of the epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis. On one hand, significant regional differences are found regarding the identical assessment methods, on the other hand, there are various approaches for assessment, for example in the context of medical diagnosis and – which is meanwhile generally established in epidemiological methods – questionnaires and/or the assessment of the disease-related quality of life. A comprehensive overview can be found in 120 . The most consistent assessment by means of standardized questionnaires in the context of the “Global Allergy and Asthma Network of Excellence” (GA2LEN) was uniquely performed for chronic rhinosinusitis 119 and in a combined way for asthma associated with chronic rhinosinusitis 82 .

Hereby, the first trial with more than 57,000 returned questionnaires from 12 different European countries with patients between the ages of 15 and 75 years could reveal a global prevalence of 10.9% (interval: 6.9–27.1%) according to the definition of European guidelines. Those data were confirmed among others by an American study with a global prevalence of CRS of 11.9% 143 . The second trial 82 additionally investigated the association with asthma in this dataset. Despite the heterogeneity in the prevalence of CRS between the single regions in Europe, the association between CRS and asthma was comparable over all centers and age groups (adjusted OR: 3.47; 95% CI: 3.20–3.76). Patients who had allergic rhinitis beside the symptoms of CRS had an additionally increased risk to be affected from asthma (adjusted OR: 11.85; 95% CI: 10.57–13.17). In non-allergic individuals, however, an association to so-called late-onset asthma was found. CRS is accompanied by a clearly reduced quality of life and has a high socio-economic relevance 144 .

AERD (aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease), is associated with rather severe course of disease 107 . A recent meta-analysis 145 reported about a 7–15% prevalence of AERD in asthmatic individuals and an increased prevalence in severe cases. In about 8.7% of the cases, patients with CRS showed symptoms of AERD, patients with confirmed CRSwNP had those symptoms in approx. 9.7%. According to EPOS3 107 , about 15% of the patients with CRS had AERD. Zhang et al. could demonstrate that specific IgE against S. aureus enterotoxin is expressed disproportionately frequently in those patients 146 .

Important, although less frequent differential diagnoses are autoimmune system diseases with involvement of the nasal mucosa and the paranasal sinuses. In this context, in particular vasculitis has to be pointed out. Depending on the stage, its clinical image may appear similar to chronic rhinosinusitis 147 148 . Recently, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) performed changes of the definitions, in particular GPA (formerly called Wegener’s granulomatosis 149 ) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly called Churg-Strauss vasculitis) must be mentioned. The diagnostic criteria of GPA of the European League against Rheumatism (EULAR) and the ACR are currently being revised based on the current “Diagnostic and Classification Criteria in Vasculitis Study” (DCVAS) 150 . Regarding the treatment of GPA with rituximab, meanwhile a recommendation degree A has been stated 151 . From a mechanistic point of view, also eosinophilic GPA (EGPA) is an interesting target for antibodies that target IL-5 or its receptor as recently investigated in clinical studies 152 (see chapter 4.2 below).

Cystic fibrosis (also: mucoviscidosis) is the most frequent autosomal-recessively inherited genetic disease (1:2,000 live births) and is associated with a dysfunction of membraneous chloride channels (CFTR, cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator) that leads to modified mucus composition in the airways and the gastrointestinal tract. In the airways, the viscous mucus that can only hardly be mobilized leads to recurrent, opportunistic, and often life-threatening broncho-pulmonary and upper-airway infections. In cases of missing enzyme substitution, the altered function in the gastrointestinal tract results in malnutrition syndromes due to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Nearly 2,000 mutations of the CFTR gene are known, so the phenotypes can vary considerably (an overview can be found in 44 45 ). In at least 25–40% of all patients, sinonasal polyposis is found 107 153 . Phenotypically, histological subtypes are observed depending on the sample, with rather neutrophilic or eosinophilic inflammation patterns 154 155 . Regarding the treatment of CF, new selective therapies with small molecules could be established (see above, chapter 1.8).

More rarely, the Kartagener syndrome 156 is found, which is the prototype of ciliary dyskinesia 53 that is obligatorily associated with nasal polyps beside bronchiectasis and situs inversus. The polyps may also contain eosinophilic infiltrates, interestingly also a clearly reduced expression of NO synthetase in the tissue is found 157 . These findings correspond a priori to the low exhaled NO values in the diagnosis 158 . In exhalations, the use of an eNose may differentiate between healthy patients, Kartagener syndrome, and cystic fibrosis with or without chronic infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa 159 . In this way, it is an interesting new tool for potential endotyping.

2.4 Endotypes of chronic airway inflammations

The phenotypic definition of chronic sinusitis with our without nasal polyposis does not give any hint to the molecular developmental mechanism, it cannot predict the therapeutic outcome, and does not contribute to the allocation of optimal therapy, i. e., for example conservative standard therapy with or without surgery 142 160 . A sound mechanistic understanding, however, is the basis for a targeted, ideally precise and personalized therapy. Hypothesis-driven research in immunology and inflammation of the past 30 years has identified the association of allergic airway diseases with phenotypically predominant eosinophilia to the Th2 diseases mainly on the basis of the also didactically elegant Th1/Th2 model 9 10 . In nasal polyps this was first shown by Bachert 76 , further intensified investigations revealed cytokine patterns 77 and also the involved T cell clones 161 followed. However, for example in Asian cohorts, distinct IL-17 associated inflammatory pattern were 162 . Interestingly, mucosal inflammatory patterns have revealed a transition to a more “western” cytokine profile over time, probably associated with socio-cultural transition 163 . Furthermore, patients were diagnosed with CRSwNP in central China in whom none of the expected or “classic” cytokine microenvironments was dominant, i. e., neither Th1 nor Th2 nor Th17 inflammation 164 . Even in special types of CRS, e. g., cystic fibrosis, other inflammatory signatures are found 161 165 . The presence of different infiltrates correlates with the response to the therapy. So Wen 166 could show that nasal polyposis with predominantly neutrophilic infiltrates does not clinically respond to oral steroid treatment. Mucin-1 expression, however, could be identified as marker for a response to steroids 167 .

The Th2-associated pathophysiology in inflammatory airway diseases in the western world led accordingly to biomedical therapy concepts which address mainly cytokines from the Th2 microenvironment (see chapter 4.2, clinical studies). Apart from the question if those new therapy procedures are affordable, a concept has been developed in the context of personalized medicine that describes endotypes. First described by Anderson 168 , this concept was intended to result in a more selective and mechanistically rational therapeutic procedure. Regarding the definition of endotypes, for example genetic, mechanistic, histological, or functional properties are classified in order to define different and mechanistically coherent entities 169 . In a simplified way, Wenzel described endoyptes as a “molecular phenotype” 170 . In the last years several position papers of highly reputed authors discussed this concept: at least – and this is a great progress – a European multicenter analysis and merely data-related study is now available for chronic rhinosinusitis 171 .

For this cohort in the GA2LEN network, initially 917 patients from 8 European countries (respectively 10 European University Hospitals) were enrolled. Finally tissue could be gained with adequate quality and quantity from 173 patients with CRS and 89 controls. Based on a pre-defined biomarker selection, all specimens were characterized and assigned to 10 different groups by hypothesis-free analysis. Inflammatory parameters (MPO, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8), type 2 inflammation markers (IgE, ECP, IL-5, and albumin), in the 3 rd group IL-17, TNF-α, and IL-22, and additionally in 2 further groups IFNγ, TGFβ 1 , S. aureus enterotoxin IgE were examined in the context of a hierarchic cluster analysis. The resulting 10 clusters were compared to clinical phenotypes and appeared mechanistically and clinically plausible in order to depict coherent subtypes. IL-5 negative groups clinically showed mainly chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis and without asthma whereas the IL-5 positive groups, which also had a high systemic and local IgE level, contained a high percentage of asthma-affected patients. Patients who had particularly high IgE values as well as specific IgE against S. aureus enterotoxin generally suffered from chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis and nearly all of them from comorbid bronchial asthma. However, unfortunately this trial has one relevant weakness: Even if further clinical data have been assessed, they are not included, i. e., data on standardized symptom scores and/or disease-related quality of life. Ideally, also more than the initially 900 patients could and should have been included in the analysis, however, cautiously 3 axiomatic statements can be made that would have to be verified in real-life clinical data and pivotal clinical trials:

The more severe chronic rhinosinusitis affects a patient in Europe, the more mechanistically probable is an eosinophilic inflammation that is associated with a quantitative involvement of IL-5, IgE and IgE against S. aureus enterotoxin, depending on the severity.

Different inflammatory patterns can exist in parallel: in addition to Th2 cytokines and IL-5, generic-inflammatory activation of IL-6 and IL-8 is found in single clusters, furthermore IFNγ and depending on this IL-17 with IL-22, or IL-22 alone.

Functional endoscopic sinus surgery can only be one element among others for treatment of this complex inflammatory disease involving the upper and lower airways and should ideally be accompanied by rational anti-inflammatory measures.

Beside those Th2-associated endotypes, probably neurogenic inflammatory endotypes exist in the phenotype of non-allergic inflammation that responds well to capsaicin therapy 141 . The terminological inexactness becomes apparent for example in the context of hormonally induced pregnancy rhinopathy: there is a very distinct hormonal pathomechanism that is sufficient for endotype definition, however, the disease can be defined only phenotypically in the patient.

The elaboration of endotypes of the upper airways is developing and there are many aspects where no adequate terminological consensus has been found yet 172 173 . Even more significant is the data deficit which has to be met in the near future.

2.5 Stratified downstream prevention

The early involvement of the nose in cases of respiratory diseases makes the upper airways a potential proxy for the lower airways and an interesting tertiary-preventive lever.

Allergen-specific immunotherapy (AIT) as classic personalized therapy is the working horse in clinical allergy. In contrast to the ongoing administration of therapeutic antibodies that may be considered as disease response modifiers, there is compelling data on the disease modifying effects of AIT and based on these properties can be utilized as an instrument in downstream prevention.

By means of the randomized, controlled and open Preventive Allergy Treatment Study (PAT Study) with 183 children it could be shown for allergic rhinitis that the children who had received a 3-year specific immunotherapy (SIT) against birch and/or grass pollen suffered significantly less from allergic asthma after 5 years of therapy onset (OR: 2.68: 1.3–5.7) 135 . Ten years after therapy onset, even more favorable outcomes were found in the immunotherapy group with an odds ratio of 4.6; 95% CI: 1.5–13.7 not to develop asthma 134 .

These data could be confirmed by analyses of retrospectively evaluated healthcare data from East Germany that included datasets of 118,754 patients between 2006 and 2012. In allergic patients who had received AIT, a lower number of newly diagnosed asthma cases was observed in comparison to allergic individuals who had not received AIT. The relative risk after regression analysis amounted to 60% (RR, 0.60; 95% CI: 0.42–0.84), but the non-adjusted risk did not vary 174 .

With publication of the Grass-Asthma-Prevention Study (GAP Study), for the first time a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial revealed a downstream preventive effect with regard to asthma symptoms for the specific allergen immunotherapy. In this European trial, 812 children were randomized with a high-dose grass pollen tablet therapy for 3 years. The study did not reach its primary endpoint, i. e., time to onset of asthma resp. wheeze based on pre-defined criteria that included reversibility of obstruction after beta-2-agonist administration. However, consistently and significantly less asthma symptoms and less consumption of asthma medication could be shown in the verum group (OR: 0.66, p<0.036) 136 .

In contrast to the specific immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis, the data on chronic rhinosinusitis have to be evaluated in a much more heterogenic way and the cohorts for interventions are generally smaller. In this context, in particular healthcare studies are interesting. Retrospective data of the National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom show that late surgery of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis may often lead to severe and recurrent cases as well as to bronchial asthma. Market research data seem to support these statements 175 176 . A study encompassing prospective data of a national British audit reports that especially patients who suffered from allergies and asthma underwent surgery particularly late. This may be due to the slow process of symptom adaptation as well as to possibly conservative therapy attitudes. However, the data reveal that patients who underwent surgery at early disease stages have a better symptom control and disease-related quality of life in the context of follow-up examinations after 12 and 60 months 177 . Furthermore, patients who had undergone surgery at an earlier time cause less subsequent healthcare expenses 178 .

Whether this conclusion proofs correct and early surgery really protects patients with chronic rhinosinusitis against recurrent disease courses and against comorbid asthma can only be demonstrated by means of consistent data from randomized interventional studies, cohort, and healthcare data. Only such data allow suggesting treatment recommendations for stratified prevention approaches in the sense of personalized medicine.

3. State-of-the-art

The existing S2k guideline for the treatment of Rhinosinusitis for German-speaking countries was revised in 2017 179 . The European position paper EPOS that had been revised in 2012 in its 3 rd edition basically corresponds to a European guideline regarding the dimension and the scientific claim and encompasses acute as well as chronic rhinosinusitis. For allergic rhinitis, the extensive document entitled “Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma” is referenced as standard manual in the area of the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI). An important milestone for causal therapy of allergic rhinitis is the German guideline on specific immunotherapy published in 2014 129 .

The significance of functional endoscopic sinus surgery for therapy of CRS is estimated as very high. This is supported on one hand by the data of healthcare systems with limited access to high-quality surgical care and on the other hand by merely rational mechanistic reflections of the pathological anatomy of the osteomeatal unit 180 181 . Hereby, surgical therapy should be performed in all cases where conservative therapy only allows insufficient control of the CRS symptoms and when endoscopy and/or imaging defines a confirmed pathological correlate as curative surgical objective. Despite 2 recently published meta-analyses, the currently available evidence is unsatisfactory 182 183 because the meta-analyses can only evaluate high-quality standardized studies, which are currently not available.

Based on the existing evidences (level 1a) for 2 main pillars of conservative therapy of chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyposis, the European guideline EPOS3 recommends (recommendation grade A) to apply topical nasal steroids and nasal rinsing with saline solution. For patients suffering from chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyposis, topical nasal and oral steroids are recommended as conservative treatment, in EPOS3 data from meta-analyses are provided that support this recommendation 107 .

A clear recommendation in favor of topical therapy is found in an evidence-based review published by Rudmik 184 . Furthermore, 2 recent meta-analyses of the Cochrane Society are available regarding topical steroids after a meta-analysis had been withdrawn because of the availability of new data published by Kalish 185 . In 2016, Chong presented a meta-analysis that could include 18 randomized, controlled trials with a pool of 2,738 patients. The authors of the meta-analysis criticize that in the context of trials on topical nasal steroids a moderate effect on symptoms such as nasal obstruction and the overall severity of the disease could be measured in pooled datasets but the overall quality of the evidence, in relation to the number of studies and patients, was only moderate or even poor and the follow-up periods were too short. In addition, the disease-associated quality of life had not been sufficiently taken into account 186 . In a second meta-analysis, nearly the same group of authors compared different intranasal topical steroids. Based on the available trials, however, no recommendation could be given for single substances or application modalities 187 .

In the European position paper, a large variety of therapies achieves the recommendation levels of C or D (not recommended). Based on the recent meta-analyses and also the confirmatory trials with biologics, the next revision will most probably implement new recommendations.

Without any doubt, the currently guideline-based therapy treats many patients in an adequate way, especially in such a well-structured and accessible healthcare system as it is found in Germany. However, data from phenotyping studies show that the therapy responses are very heterogenic regarding surgical as well as conservative therapy approaches and that some patients do not benefit at all 160 . Based on an algorithm with non-supervised machine learning, Soler and colleagues tried to predictively identify these groups. This was partially successful in a pilot study, but it led to clinical groups that were not attributable by known and intuitively understood features and that additionally completely lack of an – at least currently known – distinct pathophysiological correlate. Nonetheless, such cohorts have to be evaluated and reproduced in order to prospectively verify a possible usability also in algorithms. In summary of endoscopic and radiological findings with systematic eosinophilia in a cohort of more than 1,700 Japanese patients, a scoring system entitled JESREC (Japanese Epidemiological Survey of Refractory Eosinophilic Chronic Rhinosinusitis) provided a cut-off value that allows describing a diagnostic criterion for eosinophilic CRSwNP and an increased risk for recurrences 188 . These results should be reproduced on an international level with a modified score, if needed. One weakness of the trial is that it could not be verified to what extent the pretreatment with steroids has an effect on the applicability of these tests because patients who had been pretreated with steroids were excluded from the study.

A so-called “unmet clinical need” of the current guideline-based therapy results because of different reasons. On one hand, it has become clear that assumedly more than 20% of the patients can only partially or not at all control their symptoms despite guideline-based, adequate, effective, and safe therapy 189 . In addition, the percentage of recurrences seems to have been underestimated for years. In the United Kingdom, the rate of surgical revisions amounts to 19.1% for CRS and 20.6% for CRSwNP in a 5-years interval and has not improved despite optimized surgical techniques and the availability of further-developed topical steroids 190 . In single cohorts, up to 80% of the patients with CRSwNP develop recurrences 84 .

It is highly probable that the patients will have to be informed more realistically; however, better characterized clinical cohorts will be needed. Further, it is completely unclear to which percentage for example missing cooperation and suboptimal compliance regarding the topical steroid intake amount in case of severe courses 191 . The lack of disease control in these epidemiologically and socio-economically relevant cohorts of chronic patients with severe or persisting allergic rhinitis and/or chronic rhinosinusitis is a factor that is currently not adequately quantified. A rather relevant percentage of those patients will probably have to be classified as SCUAD (severe chronic upper airway disease) with multifactorial underlying disease processes 192 .

In this context, stratified medicine may allow individual therapy and downstream prevention. Possible measures are pathophysiologically rational and targeted interventions with biologicals.

4. Biologicals in clinical trials with rhinological diseases

4.1 Allergic rhinitis

4.1.1 Trials with omalizumab

The until now last and fifth human immunoglobulin class IgE was discovered in 1967 after a scientific race competion of Johansson and Bennich against Kimishige and Teruko Ishizaka. Ishizaka called it immunoglobulin E 193 , but was not able to isolate and characterize it. Reagin of the Prausnitz-Küster reaction that had not been identified up to that time was characterized by Bennich and Johansson 194 and the association to asthma was revealed in the same year 195 . The IgE mediated sensitization against an allergen is the pathomechanistic basis of modern allergology and completes the concept created by Pirquet that allergy is a specific hypersensitivity reaction 196 .

Omalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against IgE and was approved by the FDA in 2003 and by the European Medical Agency (former EMEA) in 2005 for therapy of severe allergic asthma. Mechanistic studies on causal treatment of allergic disease did not meet the expectations first because further allergic reactions occurred despite the effective pharmacological antagonism and elimination of IgE from the serum.

In a double-blind and placebo-controlled trial with a cohort of 536 patients, Casale could demonstrate the dose-related effect of omalizumab as monotherapy for patients with allergic rhinitis against ragweed 197 . In 2003, this effect could be confirmed for perennial allergens 198 .

Mechanistically interesting was the combination of omalizumab with allergen-specific immunotherapy. Hereby, omalizumab could clearly reduce the incidence and severity of the side effects in the phase of increased dosing in particular in the context of accelerated dose increase of the allergen for effective and tolerogenic maintenance dosage, so-called rush-immunotherapy. Kopp applied omalizumab in a pediatric cohort and could observe in vitro a reduced release of leukotrienes in children who received immunotherapy against pollen under the protection of omalizumab 199 .

In the context of a trial of the Immune Tolerance Network of the National Institute of Health (USA), Casale conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled 4-arm study with a rush immunotherapy against ragweed pollen in combination with and without omalizumab as well as a double placebo group. In each arm 39-40 patients were randomized. From a total of 159 patients, 123 completed the trial that started preseasonally, included the pollen season, and lasted for 21 weeks. The primary endpoint of the study was the comparison of the seasonal symptom score between the group with combined application of omalizumab and allergen immunotherapy and the group with immunotherapy alone. The primary endpoint could be achieved when the effect size was relatively low (0.61 vs. 0.85, p=0.12). Furthermore, a post-hoc analysis could show that the application of omalizumab significantly reduced the incidence of systemic allergic reactions by 80% during rush immunotherapy; however, with 25.6% the rate was extremely high in the group of immunotherapy without omalizumab and was based on a blinded self-assessments of the patients. The increased effectiveness of the combined application of omalizumab with immunotherapy was explained by the fact that omalizumab was further therapeutically administered at the time of pollen occurrence. If the effect of immunotherapy was better in the group treated with the combined therapy beyond the time of systemic elimination of omalizumab, cannot be stated based on the published data.

In vitro specimens of a total of n=36 individuals from the same patient cohort, were investigated in further mechanistic studies by Klunker et al. Hereby, a validated facilitated antigen binding (FAB) assay was measured for assessment of the serum inhibitory activity against IgE binding to B cells. In the group of patients who underwent combined therapy and in the group with omalizumab, binding of IgE was inhibited of nearly 100%, even beyond the pollen season. The group with immunotherapy alone reached an inhibition of 50%. Mechanistically, it could be shown that allergen-specific IgE was no longer available in both therapy arms with omalizumab. Interestingly, the serum-inhibitory effect could be maintained up to 42 weeks after treatment and was even more pronounced in the group with combined treatment 200 .

In clinical routine, the combined application of omalizumab plus allergen could be established in Europe, in particular for patients who require an increased safety profile regarding specific immunotherapy. This concerns for example the presence of severe bronchial asthma, urticaria, severe food allergies 202 , or pre-existing anaphylaxia. Hereby it must be taken into consideration that not all these applications are in-label. A sound review article is found under 203 .

4.1.2 Trials with VAK694

The induction of regulatory T cells that express the transcription factor Foxp3 and other subtypes, e. g., Tr1 cells, is considered a mechanistic key event of specific immunotherapy 204 . Actually, monitoring of this T cell conversion to regulatory populations is extremely difficult and in humans it is only possibly by extensive ex vivo examinations 205 206 . Antigen-specific monitoring is only performed via flow cytometric analyses with tetramers or ELISpots 207 208 . Mechanistic studies on specific immunotherapy could show that the induction of regulatory T cells is associated with the secretion of inhibitory cytokines such as TGF-β 1 and IL-10; IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 secreting T cells are reduced 209 210 211 212 . While IL-5 mainly contributes to eosinophilia in allergic inflammation as pro-eosinophilic cytokine, IL-4 and IL-13 induce the production of IgE in B cells and have direct proinflammatory effects on the respiratory epithelium 74 , mucous secretion as well as goblet cell hyperplasia of allergic inflammation of the airways 213 . On this basis, the concept of combined specific immunotherapy with human anti IL-4 antibodies was developed. The antibody VAK694 is a fully human antibody directed against the cytokine IL-4 and was applied in patients in the context of an exploratory, double-blind, placebo-controlled 3-arm study. Primary endpoint of the trial was the cutaneous allergen-specific late-stage reaction as antigen-specific surrogate for T cell suppression 12 months after therapy in vivo. Explorative surrogate endpoint was the antigen-specific production of IL-4 in ELISpots in vitro. Furthermore, the T cell populations were characterized by flow cytometry. The study was designed as proof-of-concept trial and not sufficiently powered for detection of symptom differences between the therapy groups in the pollen season. The primary endpoint, tolerance in the cutaneous late phase response compared to standard therapy, i. e., specific immunotherapy alone, was not achieved because standard therapy alone reached a suppression of the allergen-induced late phase response in the skin of more than 90% although a subeffective dosage of the allergen had been chosen. The proof of concept was achieved in vitro: a sustainable suppression of allergen-specific IL-4 producing cells could be shown 12 months after the end of combined therapy and in comparison to immunotherapy alone as well as placebo. This effect, however, did not translate into the clinical endpoint, the cutaneous late phase reaction 215 . If the combination of anti-IL-4 with specific immunotherapy is pursued, remains unclear because the development of VAK694 was stopped.

4.2 Chronic rhinosinusitis

4.2.1 Omalizumab

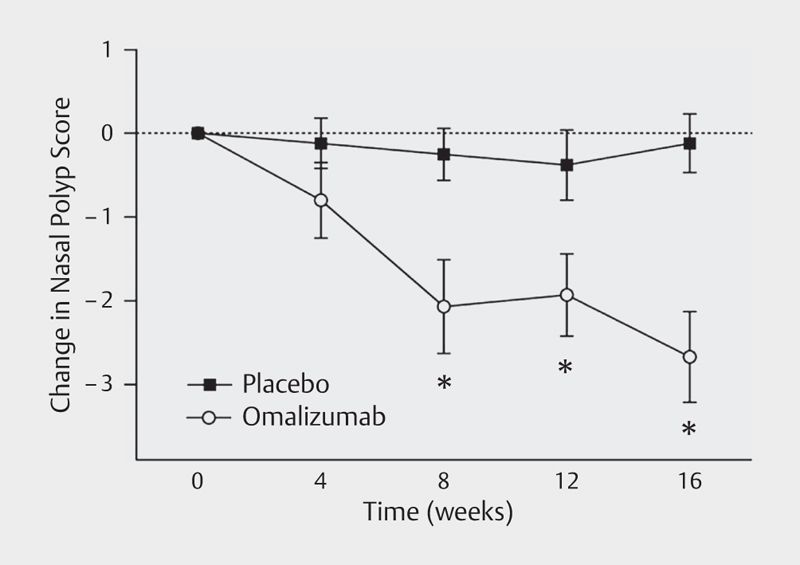

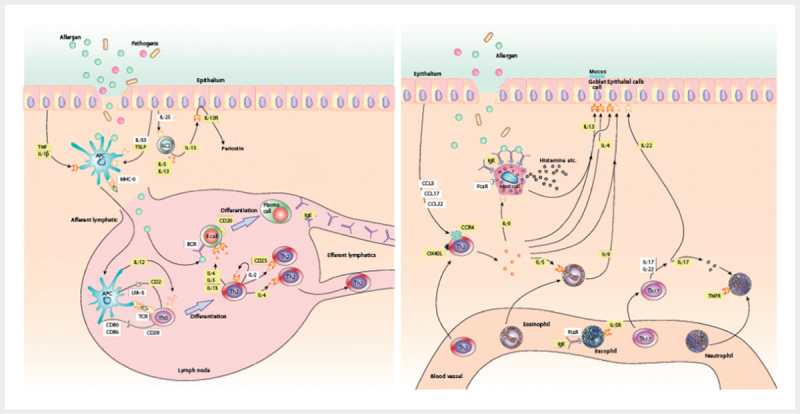

The role of IgE in asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis as well as parasite defense was described already very early 216 . In 1970, IgE was found for the first time in tissue homogenates in nasal polyposis 217 , and Whiteside examined it in 1975 218 regarding local lymphocytes and the correlation with systemic IgE levels and atopy. Already at that time, the question of local IgE production in nasal polyps was addressed which became a relevant research issue in the pathophysiology of CRS. In 2001, Bachert could show that the proportion of IgE in the tissue correlates with local eosinophilic infiltrates 78 . In the early 2000ies, the association with specific IgE against S. aureus enterotoxin 146 219 was discovered, in particular in severe cases, which was another hint to pathophysiologic involvement of IgE. In 2005, Gevaert could document the local IgE synthesis in the tissue 66 . From here, it was a logic consequence to investigate the therapeutic application of omalizumab in patients with CRSwNP in clinical trials. First case reports and retrospective case series were published by Penn 220 , Guglielmo 221 , and Vennera 222 , mainly in patients who were treated in-label with omalizumab because of their severe asthma. Pinto and colleagues were the first research group that published a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The study could reveal no superiority of the verum arm compared to placebo. This was also due to the inclusion criteria because in this study patients with as well as without nasal polyposis were included 223 . A placebo-controlled follow-up trial published by Gevaert in 2013 with application of omalizumab in patients with CRSwNP and comorbid asthma over a treatment period of 16 weeks, could consistently observe a reduction of the nasal polyp score (−2.67; P=0.001) as well as the nasal symptom score and the disease-related quality of life in comparison to placebo 224 ( Fig. 3 ). Further studies in the context of this indication have already been completed according to the study registries (NCT01066104), at the time of manuscript submission the results have not been published. Subsequent studies on CRS have been registered as actively recruiting, among others under clinicaltrials.gov .

Fig. 3.

Change of the nasal polyp score under the treatment with omalizumab vs. placebo (according to 224 , Gevaert P., JACI 2013, licensed by RightsLink/Elsevier).

Paradoxically, in the initial phase of the treatment with omalizumab, a transient increase of the overall IgE is observed because of the development of biologically inactive but measurable IgE antibody complexes. Only after about 16 weeks, the pharmaco-dynamic response can be measured adequately in the serum. Pharmaco-dynamic investigations under omalizumab treatment additionally show that the de novo IgE synthesis decreases of about 50% per year with the treatment with omalizumab 225 . This observation can be explained by a possible change of the IgE homeostasis because of negative feedback mechanisms that involve the low-affine IgE receptor. Thus it is justified to assume a possible timely limitation of therapy and withdrawal trials. For this purpose, long-term data would have to be evaluated in order to define rational therapy corridors.

4.2. 2 Reslizumab

The pathophysiological role of IL-5 in CRSwNP of western type was described early 76 77 . A therapeutic antagonism seemed to be obvious. The first trial in humans and actual milestone trial of CRSwNP was published by Gevaert in 2006. In this first double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, a total of 24 patients with bilateral CRSwNP received a single dose of the humanized anti-IL-5 antibody reslizumab or placebo. The effect on systemic eosinophils in the blood and ECP concentrations in the serum could be pharmaco-dynamically measured up to 8 weeks. Only half of the patients treated with the real substance showed a therapeutic effect on the endoscopically revealed polyp scores. In a post-hoc analysis, Gevaert and colleagues could demonstrate that the responders were those patients who had high IL-5 concentrations in nasal secretion at the time of treatment onset. By means of a regression analysis, a cut-off value for IL-5>40 pg/ml in nasal lining secretions could be defined that could predict a positive therapy outcome after reslizumab application (odds ratio: 21.0; 95% CI: 1.5-293.3; P=0.009). A multicenter study with reslizumab conducted in the USA investigated the effectiveness of poorly controlled eosinophilic bronchial asthma. Interestingly, reslizumab was more effective in the subgroup of asthma patients with known CRSwNP compared to asthma patients without polyposis 226 . This subtyping corresponded quasi to an indirect endotyping. Another trial on CRS with reslizumab has been registered as recruiting at the time of manuscript submission under clinicaltrials.gov .

4.2.3 Mepolizumab

After first successful studies on the treatment of eosinophilic asthma 227 228 , Gevaert conducted a 2:1 randomized pilot study of 8 weeks duration with 2 therapeutic applications (750 mg i. v., each) of the humanized anti-IL-5 antibody mepolizumab. Compared to the dosage that is currently approved in the EU for eosinophilic asthma (100 mg s.c.), this is a rather high dose that was however well tolerated and showed a reduction of the polyp size in the majority of the patients, which could be consistently documented by radiological assessment. Interestingly, in contrast to the reslizumab investigation, local IL-5 concentration in nasal lining secretions did not predict the therapeutic outcome in this trial 229 .

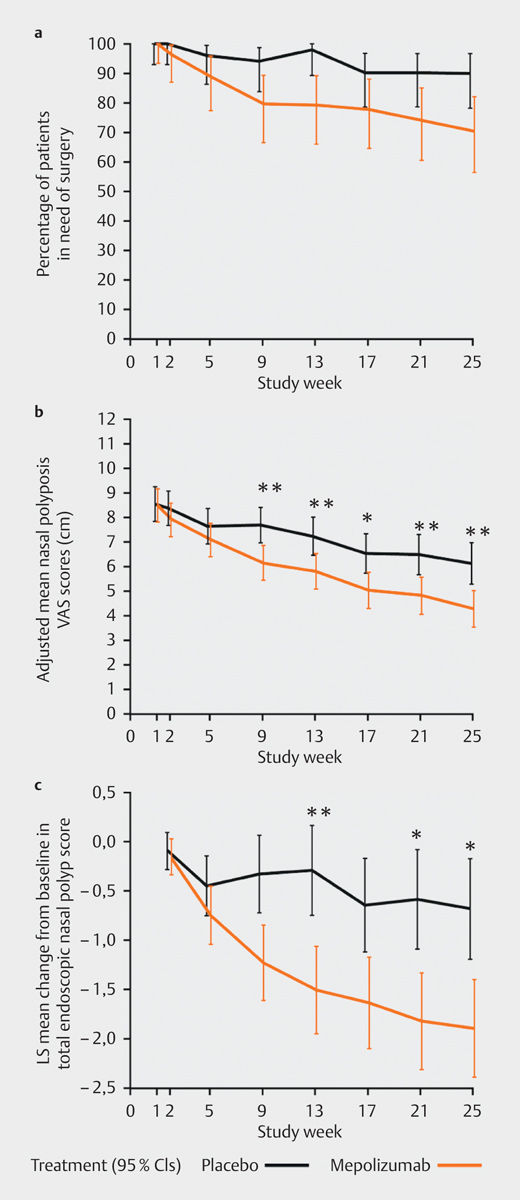

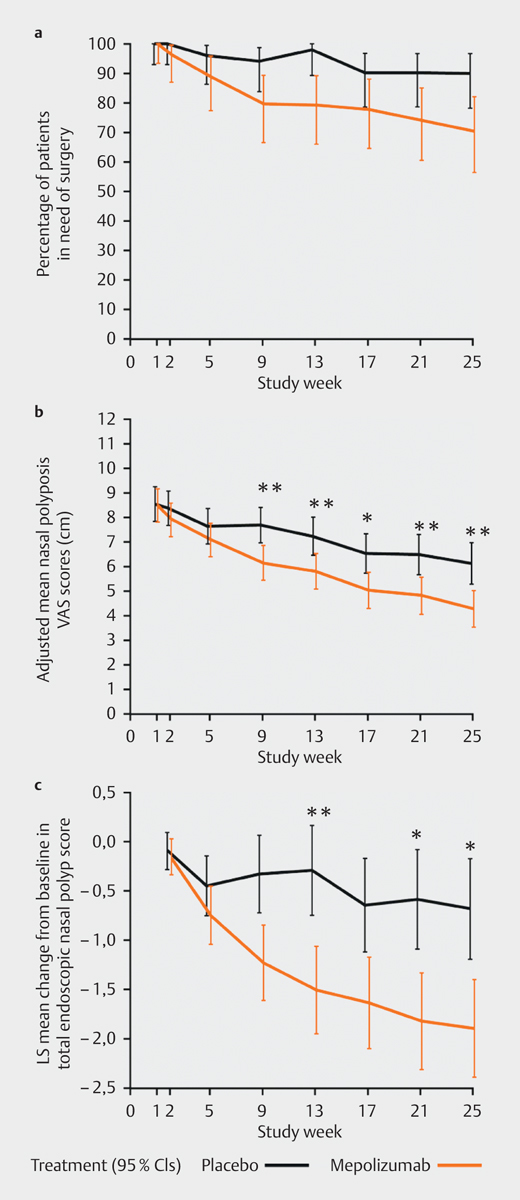

In 2017, Bachert and colleagues published a European multicenter confirmatory phase-II/III-study on mepolizumab for therapy of CRSwNP. In this study that had been initiated in 2009, 105 patients from all over Europe with severe therapy-refractory CRSwNP with indication for surgical therapy were randomized 1:1 either for 750 mg mepolizumab or placebo and received their treatment 6 times in 4 weeks as add-on therapy to topical nasal steroids. The primary endpoint was defined as indication or need of surgical therapy of CRSwNP 25 weeks after therapy initiation. 25 weeks after randomization, 30% of the patients with mepolizumab did no longer need surgical therapy (ITT, 16 [30%] vs. 5 [10%]; P=0.006). Consistently, also the VAS scores reduced in the verum group (− 1.8 in week 25; ITT 95% CI: 22.9–20.8; P=0.001) as well as the SNOT-22 test and in the post-hoc analysis even the endoscopic polyp scores ( Fig. 4 ). Also in this trial, mepolizumab was well tolerated despite the relatively high dosage. In the verum group, smelling based on VAS improved, unfortunately, different smell tests were applied in the trial so that this important parameter cannot be systematically included in the analysis 230 .

Fig. 4.

Effectiveness of mepolizumab vs. placebo in CRSwNP: consistent reduction of the need for surgery, VAS scores and the endoscopic polyp score (according to 230 ; Bachert C., JACI 2017, licensed by RightsLink/Elsevier).

4.2.4 Benralizumab

Similar to mepolizumab and reslizumab, benralizumab functionally inactivates the mediation of biological, mainly pro-eosinophilic effects of IL-5 by binding the therapeutic humanized antibody to the IL-5-alpha subunit of the IL-5 receptor (overview in 231 ). For CRS, no trials are currently available. At the time of manuscript submission, one study on CRS was registered as active and not recruiting under clinicaltrials.gov .

4.2.5 Dupilumab

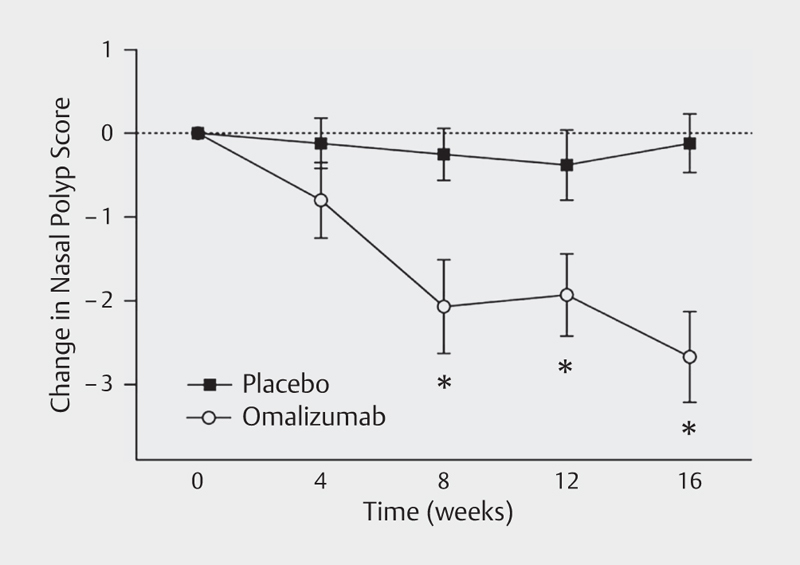

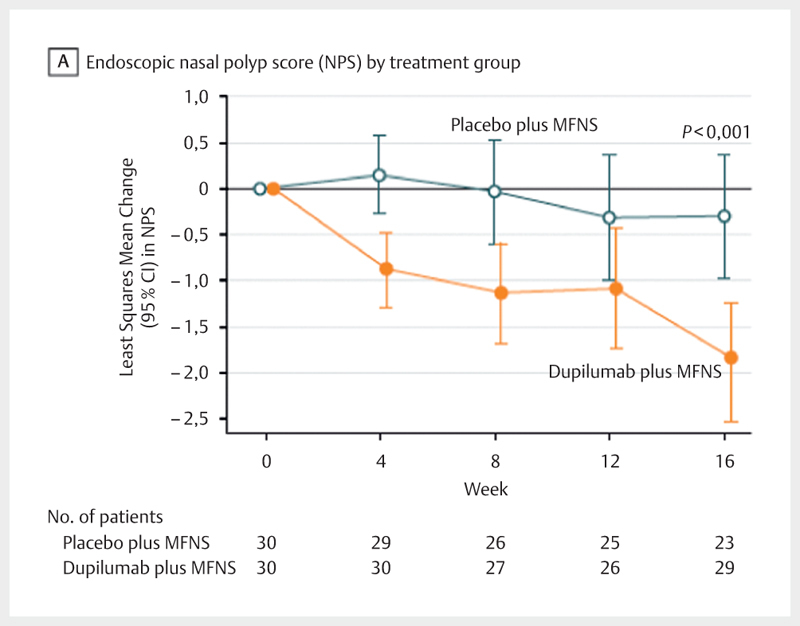

The fully human antibody binds the common alpha-subunit of the IL-4 and IL-13 receptor and thus interrupts the pleiotropic Th2 signals into immunological compartments. The high effectiveness in cases of eosinophilic asthma 232 and in particular in the treatment of atopic eczema was convincingly described with pivotal trials 233 234 . Regarding the indication of CRS, an international consortium around Bachert and colleagues investigated dupilumab vs. placebo as add-on therapy of topical nasal steroids in 60 patients in a phase-II/III-study over 16 weeks. In the endoscopic polyp score, a difference of − 1.6 of verum (95% CI: − 2.4 to − 0.7); P<0.001) could be shown in comparison to placebo. This effect was consistent to a reduction of the CT-morphologically determined Lund-MacKay score and the SNOT-22 ( Fig. 5 ).

Fig. 5.

Change of the nasal polyp score under the treatment with dupilumab vs. placebo (according to 232 ; Bachert C., JAMA 2016, licensed by RightsLink/American Medical Association).

In 2017, dupilumab was approved for treatment of atopic eczema in the USA by the FDA, the approval for the EU was recommended by the EMA.

Other target structures for therapeutic antibodies are currently investigated. In this context, for example anti-TSLP and anti-Siglec-8 should be mentioned. For further possibilities of cytokine modulation, furthermore a test substance PF-06817024 in this indication is evaluated (source: clinicaltrials.gov ).

4.3 Examples of rare indications

For patients suffering from eosinophilic GPA (Churg-Strauss vasculitis), which is often associated with an involvement of the upper airways in the sense of CRSwNP, Wechsler evaluated the application of mepolizumab in a multicenter trial. In this study, 136 patients were randomized. The percentage of patients with remission was significantly higher in the group treated with mepolizumab (32 vs. 3%; odds ratio: 16.74; 95% CI: 3.61–77.56; P<0.001), in the verum group, the consumption of systemic steroids could be clearly reduced in more than 40% of the patients. The recurrence of sinonasal symptoms was complained by 35% of the patients of the mepolizumab group vs. 51% of the placebo group within one year. The profile of side effects and the steroid-saving effects allow the statement that mepolizumab is an interesting therapeutic alternative 152 .

For cystic fibrosis, new and successfully tested substances were approved with chloride channel enhancers (see chapter 1.8).

4.4 Biomarkers

A true personalization of the above-mentioned and very expensive therapy by means of biomarkers could meet the requirements of precision medicine to make available the adequate therapy at the right time of the disease for every patient in the best way possible. However, in particular the implementation of these markers turns out to be much more difficult. This is also due to the missing protection by patents and the resulting only low commercial interest. Apart from comprehensive clinical work-up of patients with CRS (see also the revised German guideline 179 ), simple markers are a good working basis.

4.4.1 Eosinophils in full blood and overall IgE: simple inflammatory markers

Especially in “western” inflammation profiles of CRSwNP, the eosinophils as well as the overall IgE in the serum are excellent global and derivative markers of Th2 inflammation 235 that are ubiquitously established without any special request and have also been investigated partially in prospective trials such as for example the JESREC cohort (see above) 188 . Also ECP is a promising marker but not easily available 140 . Larger investigations on the sensitivity and specificity are necessary.

4.4.2 Exploratory biomarkers

This field opens an enormous spectrum of possibilities for stratified therapy, however, the number of identified potential markers does not at all correspond to the state of validation, which was recently shown also for the relatively well standardized AIT 236 , nonetheless the new markers are scientifically interesting and would have to be verified. On an experimental level, for example new possibilities are seen based on the expression of DPP10 (dipeptidyl peptidase 10) as marker for AERD 237 , transglutaminase-2 (TGM2) expression in the tissue as possible marker of AERD-negative endotype 238 , and also the WNT signaling 239 . A comprehensive overview of possible local and systemic biomarkers in the airways is found in 240 .

A notable example for a Th2-associated biomarker is periostin. The expression in patients with asthma correlated with the successful response to therapy with the anti-IL-13 antibody lebrikizumab 241 . Unfortunately, those very promising data could not be confirmed in the pivotal LAVOLTA trial 242 243 . It must be discussed if this fact is due to a selection bias of the sample or the biomarker itself. In a post-hoc biomarker trial, Bachert and his research group investigated local and systemic expressions of periostin in different therapy modalities. In this context, it became obvious that the periostin expression reflects the local and systemic eosinophilic load and was reduced in serum and nasal secretion after application of systemic steroids as well as after application of mepolizumab and omalizumab in CRSwNP 244 . However, now prospective studies are required.

Even where the expression of the local pathophysiological factor would be expected, the results are very heterogenic. Thus, a trial on the treatment of CRSwNP with reslizumab could predict the therapeutic outcome based on the local expression of IL-5; in the context of treatment with mepolizumab, this correlation could not be shown (see above chapter 4.1) 229 245 .

It is unlikely in the authors’s view that only single markers will determine the biomarker situation. It may be speculated that ENT specialists will have to implement the complex data of the findings gained by hypothesis-free analyses and to make therapeutic and even surgical decisions for example supported by algorithms.

4.4.3 Molecular allergology