Abstract

The microbiome is defined as the total of cellular microorganisms of baczerial, viral or e. g., parasite origin living on the surface of a body. Within the anatomical areas of otorhinolaryngology, a significant divergence and variance can be demonstrated. For ear, nose, throat, larynx and cutis different interactions of microbiome and common factors like age, diet and live style factors (e. g., smoking) have been detected in recent years. Besides, new insights hint at a passible pathognomic role of the microbiome towards diseases in the ENT area. This review article resumes the present findings of this rapidly devloping scientific area.

Key words: Microbiome, sinusitis, head and neck cancer, otitis

Abbrevations

- CRS

chronic rhinosinusitis

- OUT

operational taxonomic unit

- MALDI-TOF

Matrix assisted laser ionization mass spectrometry – time of flight

- Teff

effector T cells

- Treg

regulatory T cells

1. Introduction and Definition

The microbiome is defined as the total of all microorganisms living on humans or other creatures (e. g. earthworms, reptiles, cows). The composition of the microorganisms is locally very different. It includes bacteria (planktonic and as biofilm), viruses, fungi, and all other types of microorganisms (archaea, amoebas, flagellates, bacteriophages etc.). Organisms where the interaction with the microbiome is inhibited artificially, remain physiologically immature regarding important regulatory mechanisms such as immune defense and are very prone to pathogens 1 . Beside systematic effects of this kind, the microbiome influences the epithelial function of the organism on all body surfaces, also in the field of otorhinolaryngology.

Because of different local environments, the microbiome varies on skin and mucosa but also in different areas of the head and neck. Furthermore, the composition of the microorganisms modifies reactively due to aging process, diseases, and also depending on therapies. It may cause several diseases or favor their development. Those diseases may also include malignant diseases.

The human microbiome is identified by advanced sequencing of the DNA and includes pathogen as well as commensal microbes. Individual differences are considered as being responsible for the susceptibility of patients and their risk to develop diseases. The susceptibility is influenced by various factors such as nutrition, metabolism, detoxification, hormone status, immune tolerance, and in particular inflammation processes 2 3 4 5 .

The human microbiome is in the focus of intensive research and it is still not fully understood. Since December 2007, the US American Human Microbiome Project (https://hmpdacc.org/), initiated by the National Institute of Health, investigates the sequencing of all genomes of microorganisms living on humans. The investigation is based on specimens from mouth, pharynx and nose, skin, gastrointestinal tract, and female urogenital tract. A specific registry was established to facilitate the cooperation between the single groups 3 .

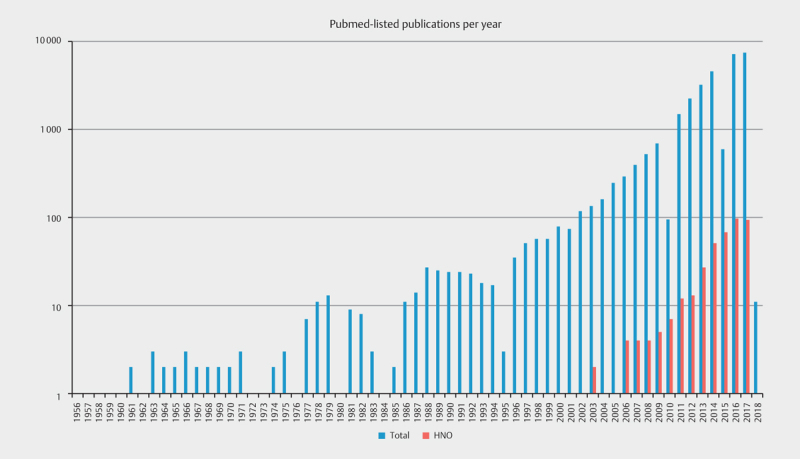

Since 2008, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) examines separately the oral microbiome. It already includes more than 600 microorganisms. At the same time, also the microbiomes of other defined areas of the body are evaluated. With the background of those intensive scientific investigations, the specific literature on the significance of the microbiome has increased exponentially during the last years. Currently more than 30,000 publications are found in this field, among those 400 specifically for the discipline of otorhinolaryngology. Even if many aspects regarding the microbiome are still not clarified, relevant basic knowledge is now available on all sub-specialties of otorhinolaryngology.

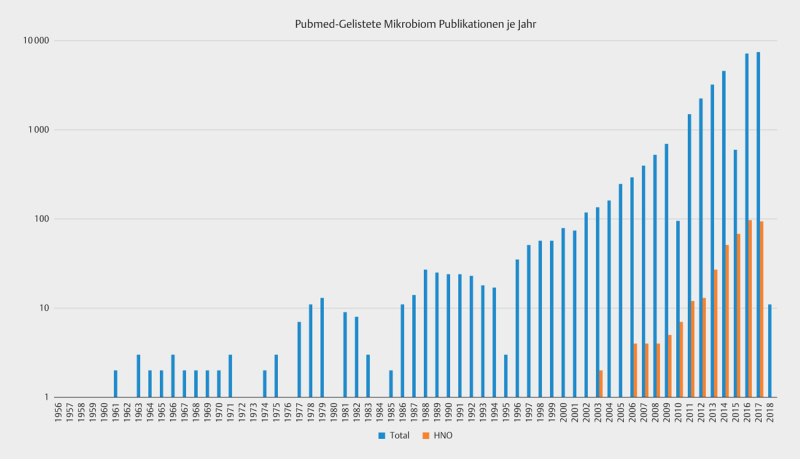

Peer-reviewed publications on “microbiome” increased enormously. Fig. 1 describes the number of publications listed under www.pubmed.com in comparison with publications that are relevant for the field of otorhinolaryngology. This aspect was defined by entering the key words of “microbiome AND (rhinology or otology or otitis or nose or sinus or (head and neck) or laryngology)”. Of course this list cannot be complete due to the heterogeneity of the discipline. Already the number of the references of this review article illustrates this fact. Fig. 1 , however, demonstrates a similar, dynamically increasing development in otorhinolaryngology with 274 publications in the field of rhinology, 153 in the field of laryngology/oncology, and 124 in the field of otology. Even an intensive research of the literature makes obvious that currently the practical consequences of those articles for the clinic are very limited, because of the low rate of comparability due to rapid technical developments as well as numerous influencing factors. However, for basic research and the development of new therapeutic approaches they might be highly interesting.

Fig. 1.

Number of publications listed in pubmed with the key words of “microbiome“ (total) or (microbiome AND (Rhinology or otology or otitis or nose or sinus or (head and neck) or laryngology); classified here as “ENT” (last retrieved on October 1, 2017).

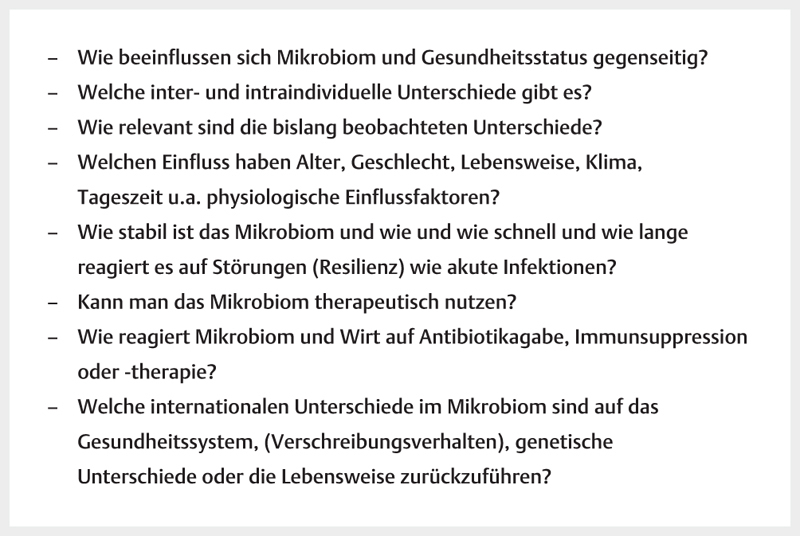

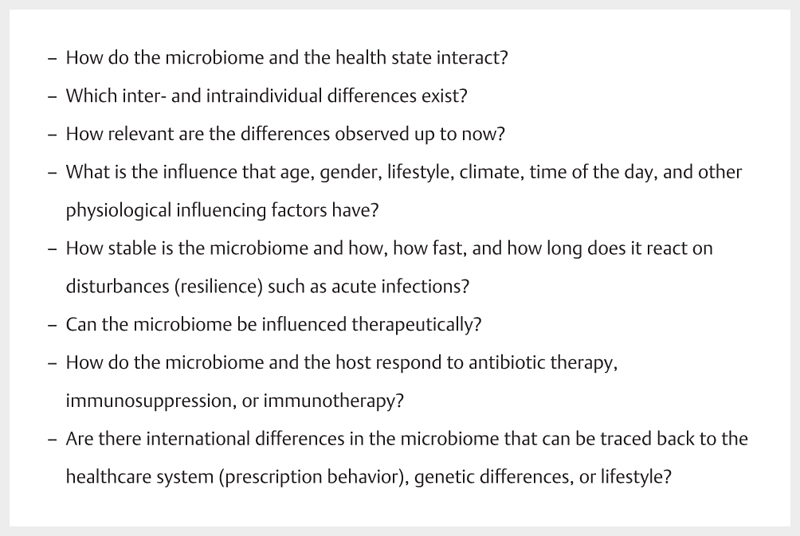

Working on the microbiome, several questions have been defined after the development of first technical standards, based on the knowledge of the interactive networking influence of microbiome and host. Fig. 2 summarizes the aspects that will be discussed in the following.

Fig. 2.

Open questions on the significance of the microbiome.

The human microbiome data portal, available under https://hmpdacc.org/ contains the current state of research on the microbiome including data of healthy individuals. In detail, the buccal mucosa ranks second regarding most hits, followed by gingiva (ranking 5 th ), nasal cavity (7 th ), dorsum of the tongue (9 th ), nares (10 th ), palatal tonsils (11 th ), right (12 th ) or left (15 th ) retroauricular fold, hard palate (13 th ), pharynx (14 th ), saliva (16 th ), nasopharynx (23 rd ), and oral cavity (34 th ). Hereby the available reference data are also classified according to technical aspects.

2. Terminology

For better understanding of the following paragraphs, but also the international literature, some terms will be introduced here as technical terms:

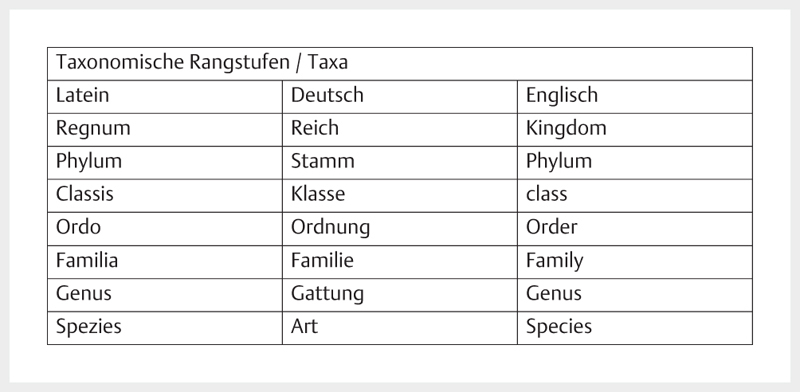

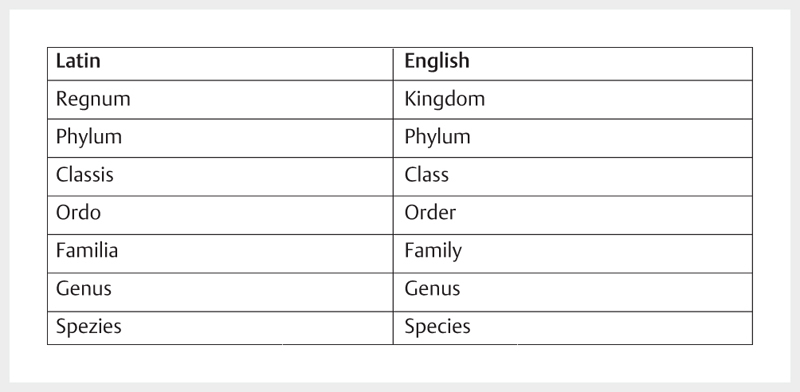

Taxon/taxa is the umbrella term for one/several groups of living beings that can be differentiated from other organisms due to common characteristics. With regard to the microbiome, this term is used for the level of microorganisms ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Taxonomic classification in the international use.

Modifications of the microbiome are generally reported as alpha and beta diversity. Alpha diversity describes the level of different types of microorganisms that are found in an individual or an examined area of this individual. Alpha diversity represents a measure for the biodiversity of a habitat. This expression was introduced by the ecologist Robert Whittaker in 1960.

For example, the oral cavity disposes of the highest alpha diversity of the gastrointestinal tract with more than 1,000 different bacterial species including aerobe and anaerobe species.

The beta diversity is the variability between individuals of the same habitat with regard to the identified microorganisms. This term was well introduced by Robert Whittaker and characterizes the measure of the difference in the biodiversity.

Gamma diversity is a measure of the species diversity in a landscape, beginning with about 1,000 ha up to about 1,000,000 ha; together with the epsilon diversity describing the biodiversity of several landscapes in one geographic region, they play a role in biological literature but not in the field of medicine.

The relationship between a modified microbiome and a specific disease is called dysbiosis, probably originating from a bacterium that uses an ecological niche as “alpha bug” 2 . Dysbiosis-related inflammations cause carcinogenesis via different metabolic pathways in the same way as chemical carcinogens like acetaldehyde and N nitrate compounds.

2.1 Taxomomy of bacteria

In the context of microbiome examinations, the classification of bacteria is performed based on the appearance, physiology, and phylogenetics. For description of the bacteria, their names were defined according to the requirements of the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (ICNB) revised in 1980. Each term is based on stored type material that is the basis for classifying a bacterium to a taxon.

A microorganism is clearly defined based on its stored type material as identifiable taxon. The term and classification are subject to scientific modifications. The current taxa are published in the respective version of Bergley’s Manual of Systemic Bacteriology 6 .

3. General Factors Influencing the Microbiome

Traditional culture procedures only allow isolating and characterizing a very low percentage of the microorganisms of a microbiome. Those procedures have been replaced by culture-independent DNA-based sequencing methods.

3.1 Procedure of a microbiome study

In the context of microbiome trials, those techniques are applied nearly exclusively. They amplify and sequence the genetic information of small subunits of ribosomal RNA (16 S-rRNA) for taxonomic characterization. The ribosomal nucleic acids are part of the bacterial ribosomes that build proteins of the according genetic information. They are sequenced in order to identify and clearly differentiate different types of bacteria. 16 S-rRNA is highly conserved with regard to genetic information and thus appropriate for taxonomic classification.

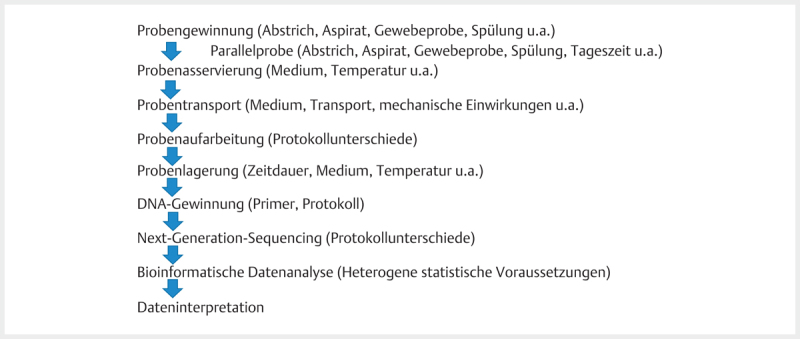

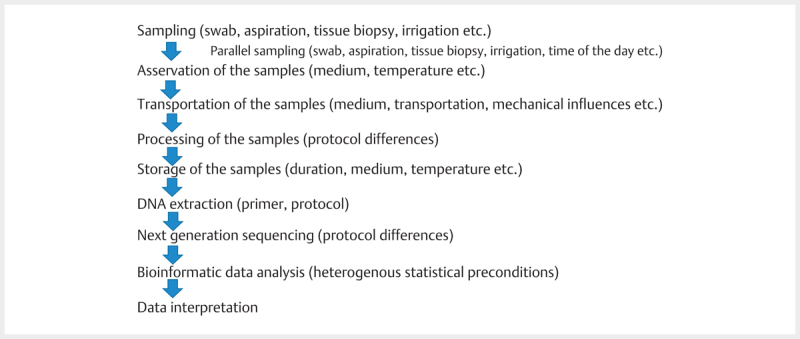

The general procedure of a microbiome trial should be standardized ( Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Procedure of a microbiome study with possible influencing factors (modified according to 7 ).

The collected tissue specimens are frozen and stabilized without contaminations, the DNA is extracted and sequenced by means of amplification to 10 5 sequences rRNA or replicated to 10 7 sequences as metagenomics by means of a shotgun PCR, also called shotgun metagenomics. On the one hand, the diversity of the specimen is evaluated with the detection of rare or excessive quantities (abundance) of specific microbes, also comparing the structures, as well as the matrix of the microorganisms that were found.

The sequencing methods with broad spectrum (chain-termination method/Sanger sequencing, pyrosequencing, sequencing-by-synthesis) vary according to technical features such as the maximum read length of the sequence, number of sequences, time per run, and throughput volume. Hereby, conventional sequencing by means of Sanger sequencing that is relatively time-consuming and allows the analysis of smaller DNA molecules plays the role of confirmation technique. Nowadays, methods of the second generation are applied for time-effective analysis because they replicate much faster. In the context of the references included in this article, the majority used the pyrosequencing technique.

3.2 Sampling technique and technical aspects

For sample collection, several procedures were and are applied, sometimes even parallel. Many published data are based on smears, tissue biopsies, aspirates, irrigation etc. As gold standard of sampling and post-processing, the protocols published in 2013 by the Human Microbiome Project were applied. Meanwhile, those protocols have been regionally developed as well as the biostatistical and bioinformatic evaluation so that the comparability of the presented results is limited and contradictions have to be questioned methodically. The complexity of interactions between microbiome and host, but also the microorganisms involved in the microbiome, has complicated research significantly. The improved availability of next-generation sequencing techniques, also based on research of proteomics and genomics, allows more and more research groups assessing parameters of the microbiome. The evaluation, however, is so complex that the results are reduced to the diversity of the microbiome. In this context, bioinformatics have to develop in order to report data gained by cooperation of patient/physician/microbiologist in a way that is free of false-negative errors.

All the technical steps described in Fig. 4 for determination of the microbiome have an impact on the outcome.

Each step in the procedure may change the quantity and the quality of the extracted DNA. Contamination is a relevant problem because of the sensitivity of subsequent procedures. However, investigations on the technical impact of different influencing factors provide contradictory statements: Storage at room temperature significantly modified the microbiome of stool in one study 8 , in another it did not relevantly change 9 , while storage of the specimens at −80+°C for different durations showed lower effects on the diversity 10 11 . On the other hand, the vaginal microbiome seems to be more stable 12 . ENT-specific trials are rare. For the laryngeal microbiome a comparability for swab- and biopsy-based studies could be revealed in an animal model of pigs 13 . The same findings appeared in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) with 36 identified bacterial species in the tissue and 30.6 specimens taken by a swab 14 .

In order to meet those diverse influencing factors, several efforts have been undertaken to standardize the procedure of microbiome trials. Available online under http://microbiome-standards.org/#SOPS , international experts provided standard operating procedures (SOP). Those SOPs give valuable hints for a standardized procedure regarding sampling (e. g. of saliva or buccal swabs). This problem has already been discussed in several journals 15 , even in the internal guideline on the publication of microbiome data 16 . There are different software packages that can evaluate biostatistically the complex data structure of microbiome data (low number of detected bacteria with at the same time high number of different species, high homology of the evaluated bacteria with 97% matches and same phyla), such as QIIME 17 18 19 20 21 , MOTHUR 22 23 , RDP tools 24 25 26 27 , and VAMPS 28 . Based on the matches with the selected primers, operational taxonomic units (OTU) are identified. Comparing 16 s RNA gene amplification – the current gold standard – and MALDI-TOF (matrix assisted laser ionization mass spectrometry – time of flight), the examination of a microbiome regarding Streptococcus viridans by means of MALDI-TOF achieved a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 100%. The authors recommended to apply different assessment procedures in parallel, which, however, would eliminate the advantage of time efficiency of the sequencing methods of the second generation 29 . In contrast, MALDI-TOF supports the identification of Gram-positive bacteria (here: Corynebacteria) when conventional 16 s RNA sequencing failed 30 . So MALDI-TOF increased the detection rate to 92.49% compared to 85.89% by means of conventional microbiological examination 31 .

A comparative evaluation of the same specimens on 3 different industrial sequencing platforms could identify further relevant deviations in the data analysis 32 . While the profiles of the microbiome composition were similar, the average abundance of the species depending on the platform, the used database, and the bioinformatics analysis seemed different. Detailed assessment of the bioinformatic analysis criticized especially the high number of false-positive detections 33 . Even the reference literature has an impact on the presented final result, but less than the one of the above-mentioned parameters 34 .

In summary, the comparability of microbiome data is generally considered as being limited which also applies to the data presented in the following 35 . With this background, efforts have to be supported unconditionally regarding a standardized reporting of the original articles under methodical aspects.

3.3 General influencing factors

Gender, age, geographic location, climate, culture, and lifestyle are general influencing factors on the diversity of the microbiome that are discussed in the literature. But also different percentage distributions of various bacteria at different times of the day were reported 36 . Alternatively, microbiome-associations are explained by host-related factors such as smoking, alcohol, diet, obesity, physical (in)activity, and polymorphism in important human oncogenes. Some factors with significance for the interpretation of the “normal” microbiome will be discussed more in detail.

3.1.1 Age

During the development of an adolescent to an adult animal, the nasal microbiome seems to mature. In an animal model of pigs, it was possible to identify that in the comparison of newborns to animals of 2–3 weeks of age the alpha diversity increased and characteristic taxa could be detected 37 .

In a murine model, the comparison of young, middle-aged, and old mice revealed significant changes of the microbiome, even after contact with Streptococcus pneumoniae (added by local rinsing of the upper respiratory tract). Resident Staphylococci and Haemophilus were sensible against Streptococcus. Furthermore, the colonization with Streptococcus pneumoniae increased with age and the mucociliary clearance seemed to be less effective 38 .

Regarding chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS), an age-related reduction of S100 proteins was considered as being the origin for a modified microbiome with development of CRS at higher age 39 . This probably provides an approach for a specific endotype of CRS in higher ages.

Age-related effects can also be found in the oropharynx. The microbiome in older people is characterized by an increased abundance of Streptococci, especially Streptococcus salivarius, but not Streptococcus pneumoniae 40 .

In comparison to younger people of the same gender, the microbiome of the stomach in 100-year-old people revealed another composition with consecutively increased plasma levels of IL6 and IL8. Generally, the biodiversity reduces with higher ages with a tendency to increase optionally pathogenic bacteria. Bacteria rather decrease, that are relevant for the metabolism of enterocytes of the gut because of their production of short-chain fatty acids (e. g. butyrate) 41 .

Meanwhile, age effects have become a therapeutic objective via intervention of the microbiome: a tryptophan-reduced diet was applied in mice in order to delay premature aging by increasing the diversity of the microbiome 42 . The positive effect of the tryptophan diet is expected to be influencing the B cell differentiation. In the microbiome, an accumulation of Akkermansia was achieved, which is a species that is often detected in healthy individuals and that is particularly negatively influenced by the aging process of the host 43 .

3.3.2 Gender

Data on gender-specific differences in the context of the microbiome are currently considered as being less reliable although some studies could identify gender-specific differences in nutrition known for the gastrointestinal tract because of the role assignment. Bacteroides, Ruminococci, Eubacteria, and Blautiae were found more often in males and Treponemen in females 44 45 . It is assumed that the observed gender differences are a consequence of different lifestyles and nutrition.

3.3.3 Smoking

Cigarette smoke is supposed to increase the permeability of the epithelial barrier against microorganisms and thus contribute to proneness to infection. The origin might be a dysbiotic microbiome that triggers for example carcinogenesis in the area of the larynx and lung.

Investigations on the effect of smoking show, independently from the selected technique, that smoke modifies the composition of oral bacteria 46 47 , especially of favorable aerobic species 48 . Furthermore, bacteria may activate the carcinogen nitrosamine 49 50 . Smoking makes the oral cavity more susceptible to proliferation of pathologic bacterial species 51 . Accordingly, the alpha diversity of the subgingival microbiome was significantly reduced in smokers. The analysis of the beta diversity also revealed differences of smokers compared to patients with chronic periodontitis of other genesis 52 . Similar changes that, however, were only detected on one side, were obvious in the nasopharynx 47 and the saliva 47 . In contrast, effects on the nasal microbiome could not be revealed 53 .

Analysis of the exhaled air 54 showed 3 relevant modifications: increased pro-inflammatory markers were detected as a hint to increased free oxygen radicals. They revealed changes in the endogenous metabolism. Second, exogenous components were found 55 . Finally, also here an interaction between the microbiome and the host was obvious. While 12 metabolites could help differentiating smokers from absolute non-smokers, only the metabolites of eucalyptol and benzyl alcohol even revealed differences in the exhaled air between active and former smokers 54 .

Regarding biopsies of the lung, 2 taxa with disproportionate relative abundance, i. e. Variovorax and Streptococcus, were found 56 . Specific for the occurrence of squamous cell carcinomas, more Acidovorax could be revealed in comparison to control tissue.

Also passive smoking changes the microbiome 57 . The microbiome of the nasopharynx and oropharynx of children depends on the smoking behavior of the mother. The detection rate of Streptococcus pneumoniae is significantly increased in active and passive smokers while Haemophilus influenzae seems to be unchanged.

3.4 Nutrition

3.4.1 Probiotics

Probiotics are preparations that contain viable microorganisms. Even if general understanding mostly focuses on oral, systemic application – e. g. eating yoghurt cultures to strengthen the intestinal flora – probiotics are not limited to this application but they can also be applied locally in the field of otorhinolaryngology or be relevant for it. For example a reduction of respiratory infections due to probiotics is discussed.

The application as food supplement is best evaluated. Via food, the composition of the intestinal microbiome of humans can be modulated effectively and in a reproducible way within 24–48 h 58 . This also represents an approach for application of probiotics 59 to e. g. stimulate the immune defense. Probiotics include unusable carbohydrates, among them fibers, resistant starch and non-starch polysaccharides, that are not enzymatically digested. Those substances are fermented by the commensal microbiome in the area of the colon/terminal ileum to propionate, butyrate, and acetate 59 . Probiotics influence the composition and activity of the intestinal microbiome and can improve well-being and health of the host 60 . The highest evidence for probiotic effects is available for fructans of the inulin type (fructo-oligosaccharides, inulin, and oligo-fructose) as well as for galacto-oligosaccharides 61 . Those probiotics shall promote the growth of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria 62 . In an animal model a modified composition of the intestinal microbiome could be achieved as well as a reduction of the body weight by feeding short-chain fatty acids 63 .

ENT-specifically, an exemplary investigation was performed topically by inoculating Staphylococcus epidermidis with and without Staphylococcus aureus in a mouse model with sinusitis to find out whether the nasal microbiome can be influenced positively 64 . After 3 days of application, more goblet cells were found under inoculation with Staphylococcus aureus alone. Additional inoculation with Staphylococcus epidermidis attenuated this effect significantly while inoculation with Staphylococcus epidermidis alone achieved similar and lower detection rates than control. The concept is based on the assumption that Staphylococcus epidermidis may competitively inhibit the biofilm development by Staphylococcus aureus, for example via inhibitory serine protease EPS. In a pilot study, it could also be demonstrated that Staphylococcus aureus in human carriers can be suppressed by additional inoculation with Staphylococcus epidermidis 65 . This pilot study shows interesting technological approaches, for example also in the context for MRSA eradication by means of antibiotics.

For the oropharynx, it could be revealed that an earlier exposition to Streptococcus salivarius may impede in vitro the cell adherence of Pneumococci 66 . Further probiotic therapeutic approaches are described below in the context of the respective microbiome that should be influenced.

3.4.2 Alcohol

Tobacco and alcohol abuse are significant risk factor for developing head and neck cancer 67 , and it is assumed that microbes mediate those risk factors. So the bacterium Neisseria that is often found on the oral mucosa disposes of alcohol dehydrogenase that transforms ethanol to the carcinogenic acetaldehyde 68 . However, the respective studies for the field of malignant diseases of the oral cavity are based mainly on tissue based examinations with older technologies 50 . Alcohol addiction seems to be associated with determined alterations of the gastrointestinal microbiome that can be found in the stool 69 . The quantity of Klebsiella increases while Coprococcus, Faecalibacterium praunitzii, and Clostridiales decrease. Additionally, alterations are found that can also be observed in liver cirrhosis. They include the reduction of Aciaminococcus and an increase of various Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria.

3.5 Antibiotic therapy

A short-term effect of antibiotic therapy on the microbiome can be expected. After 5 days of oral application of amoxicillin with clavulanic acid a significantly reduced bacterial concentration could be revealed 70 . In particular, also the Bifidobacteria concentration in the stool was reduced. While this effect could be expected at that time, a follow-up examination 2 months after antibiotic therapy revealed a persisting alteration of the microbiome. So otherwise healthy individuals still had an abundance of Bifidobacteria that was reduced to 60% of the original value. An older investigation showed an increased resilience of the gastrointestinal microbiome compared to amoxicillin alone 71 , but it confirms changes more than 2 months after antibiotic therapy.

Antibiotic treatment in early childhood is associated with a higher risk to develop asthma later. So an antibiotic therapy at the ages of 0–2 years increases the risk to develop asthma at the age of 7.5 significantly (odds ratio 1.75; 95% confidence interval of 1.40–2.17) while multiple antibiotic therapies increase this risk even further (e. g. 4 or more therapies: odds radio 2.82, 95% confidence interval of 2.19–3.63). With the background that children suffering from atopic disease currently receive about 1.9 times as frequently antibiotic than children without atopy 72 , the prescribing behavior of ENT specialists should be questioned critically.

3.6 Vaccination

Vaccination against Haemophilus influenzae does not relevantly modify the microbiome of the nasopharynx. This seems to indicate a directed elimination of the target 73 . In the context of a prospective, placebo-controlled study 74 before and in parallel to vaccination against influenza, the oral application of Lactobacillus casei 431 showed no changes in the response rate by serum conversion, while the duration of respiratory complaints was shorter when the probiotic was applied (average±standard deviation: 6.4±6.1 vs. 7.3±9.7 d, P=0.0059). Since the influence of vaccination on the microbiome has been evaluated clearly less frequently, methodical weaknesses cannot be excluded.

4. Microbiome in Otorhinolaryngology

4.1 Ear

Despite the common pathophysiology of adenoids and chronic otitis media with effusion, the microbiomes are totally different. In otitis media with effusion, Alloiococcus otitidis (23% average relative abundance), Haemophilus (22%), Moraxella (5%), and Streptococcus (5%) were found while the detection of Alloiococcus and Haemophilus correlated inversely and Haemophilus occurred more frequently in bilateral otitis media with effusion 75 . As bacterial pathogens, in addition Turicella and Pseudomonas were found increasingly in the age group older than 24 months 76 . Whereas Turicella and Actinobacteria were more rarely associated with severe conductive hearing loss, Haemophilus seems to be clearly more often causal 76 . Similar microbiomes were detected in Australian children originating from aborigines 77 . In contrast, significant differences could be found between the microbiome of otitis media with effusion and the one of the palatine tonsil 78 . According to other investigations, pseudomonas dominated the microbiome of the middle ear with a detection rate of 82.7% 78 . Genetic differences could be described as possible causal influencing factor for different characteristic microbiomes 79 .

4.2 Nasopharynx

Hyperplasia of the adenoids is one of the most frequent reasons to present a child to an ENT-specialist. The colonization of the nasopharynx in children was already described above with regard to the pathophysiological correlation with chronic otitis media with effusion. Pseudomonas, Streptococci, Fusobacteria, and Pasteurellaceae dominate the microbiome of adenoids 78 .

Adenoids are frequently associated with acute rhinosinusitis 80 . Accordingly, adenotomy was approved as possible therapy of chronic rhinosinusitis in children 80 . An explanation for the interactive influencing of adenoids and paranasal sinuses in children is the detection of biofilm on the adenoid surface 81 82 . A prospective observational study in children between the ages of 1 and 12 years revealed a high association between the microbiome on adenoids, their center, as well as the middle nasal meatus. This shows that recurrent infections of the paranasal sinuses and the nasopharynx in our pediatric patients may be explained on a bacteriological basis by the re-distribution of certain microbiomes. Furthermore, the clinical success of adenotomy in patients with concomitant acute rhinosinusitis can be explained 83 . In the area of adenoids, mainly Haemophilus, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus are found 80 .

However, no significant correlation between the colonization of the adenoid surface and the detection of microbes in the center of adenoids could be revealed in other studies 83 84 so that the association of the superficial microbiome and the microbiome of adenoid tissue cannot be confirmed.

Former premature children have a stronger heterogeneity of the nasopharyngeal microbiome than normal children of the same age. Hereby, Proteobacteria were increased and Firmicutes were reduced. These differences persisted despite infection with a rhinovirus which was interpreted as a hint to persisting immune modulation regarding inflammations of the respiratory tract after premature delivery 85 .

In the nasopharyngeal microbiome of children with asthma between 6 and 18 years Moraxella, Staphylococcus, Dolosigranulum, Corynebacterium, Prevotella, Streptococcus, Haemophilus, Fusobacterium, and Neisseriaceae were found in 86% of all microbiome examinations. Different seasons could not reveal relevant differences of the alpha and beta diversity. But the relative percentage of Haemophilus, Moraxella, Staphylococcus, and Corynebacterium varied between summer and fall as well as within the evaluated age groups 86 .

Finally, an acute viral infection with human rhinovirus or respiratory syncytial virus changed the profile of the nasopharyngeal microbiome in an evaluation of n=123 healthy children regarding the bacterial composition 87 . So in summary, the microbiome of the nasopharynx has to be considered as highly variable.

Because of possible pathophysiological correlations between acute viral infection of the upper airways with the nasopharynx as possible reservoir and the risk to develop pediatric bronchial asthma 88 , further investigations on the microbiome of the nasopharynx were conducted. Prospectively, an initial colonization with Staphylococcus or Corynebacterium before stable colonization with Alloiococcus or Moraxella could be detected in 234 children. Virus associated changes could be found due to the transient detection of Streptococcus, Moraxella, or Haemophilus. An early asymptomatic colonization with Streptococcus turned out to be a significant predictor for later development of bronchial asthma 89 .

In cases of pediatric pneumonia acquired in the population, investigations revealed bacterial genesis in 95.13% and only in 0.72% viral genesis based on the microbiome. Most frequently, Paramyxoviridae, Herpesviridae, Anelloviridae, and Polyomaviridae were detected 90 . An extensive assessment of the viruses in the nasopharynx revealed a viral origin of about 1/7 of all microbiomes in more than 700,000 microbiome data of 210 patients. Paramyxoviridae, Picornaviridae, and Orthomyxoviridae were detected and additionally a new rhinovirus C was found 91 . These evaluations on the viral components of the microbiome indicate a high and nearly unknown percentage that interacts closely with the bacterial microbiome.

Regarding therapy of the nasopharyngeal microbiome, another publication is available. According to this study, Pneumococci were found in the microbiome of about 25% of the examined adults. An intranasal application of Pneumococci in adults with high diversity of the nasopharynx led more often to subsequent pneumococcal colonization 92 , which then favored an increased diversity of the microbiome.

4.3 Nose and paranasal sinuses

The endonasal microbiome is highly variable 93 . Therefore the nasal microbiome is significantly different from the less diversified microbiome of the lower airways. However, reports exist about significant cohort differences 93 . In this context, also intraindividual differences of the microbiome of the middle nasal passage, the middle turbinate, and the inferior turbinate were found 93 . Aerobic bacteria are observed more frequently in the nasal cavity with about 80% of the microorganisms compared to anaerobes 94 .

In all patients who underwent surgery for control or for CRS, also fungi could be found in the nose 95 . The alpha diversity of the fungi was slightly lower in the controls compared to CRS (8.18 vs. 12.14, respectively). After surgery of the nasal cavity, the alpha diversity decreased, which was mainly associated with a reduction of Fusarium and Neocosmospora.

With regard to therapeutic change of the nasal microbiome, a double-blind cross-over study was performed: a mixture of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria was applied once in healthy individuals without detecting side effects or changes of the commensal bacterial as well as selected cytokines (including IL8 and IL15) 96 .

4.3.1 Allergic rhinitis

In addition to the traditional hypothesis that hygiene promotes allergic sensitization, the microbiome/microflora hypothesis was established 97 . Disturbance of the gastrointestinal microbiome interferes with immune mechanisms of the tolerance development. In this way, the increased incidence of allergic diseases 98 99 and bronchial asthma 100 might be explained. It is based on investigations according to which a reduced diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiome is associated with a higher prevalence of allergic diseases in schoolchildren 98 99 .

However, the exact mechanism is currently not clear. The hypothesis is supported by the detection of pathophysiological relations between a disturbed gastrointestinal microbiome and the occurrence of asthma 101 102 103 . One possibility of influencing the local and systemic inflammation of the respiratory tract 104 is the formation of short-chain fatty acids that are built by fermentation of fibers by intestinal bacteria 105 106 . The increased risk of developing bronchial asthma after antibiotic therapy in early childhood was already mentioned.

4.3.2 Microbiome and chronic rhinosinusitis

The microbiome of patients with CRS varies enormously. There are probably significant differences in the composition of CRS without nasal polyposis (CRSsNP) and with nasal polyposis (CRSwNP) 93 . CRSsNP seems to be characterized by a microbiome with reduced diversification as well as anaerobic enhancement 93 . Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and Fusobacterium are measured in increased quantities. CRSwNP, however, is characterized by increased percentages of Staphylococcus, Alloiococcus, and Corynebacterium. Hereby, the detected variations are significantly different from the microbiome of patients with allergic rhinitis.

In the middle nasal meatus of patients with rhinosinusitis mainly Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Propionibacterium acnes were found 107 . Also in the maxillary sinus predominantly aerobic bacteria (about 60%) were detected. Most frequently, Streptococci (28.8%) and Prevotella (17.8%) were found. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and Staphylococcus aureus, however, were identified in less than 10% of the specimens 94 . The variance between the patients seems to be higher than in the different nasal regions. In particular, the middle nasal meatus reflects representatively the microbiome of the entire nose and paranasal sinuses (compared to nostrils, maxillary sinus, frontal sinus, sphenoid sinus). However, it overestimates the incidence of Corynebacterium 108 .

4.4 Oral cavity

The subgingival microbiome of Chinese twins is exemplary for the high variety characterized by 18 phyla and 179 genu 109 . Caries was associated with a high percentage of Actinobacteria and the reduced detection of Fusobacteria. In adults, more often Treponemen were found, but these seem to be typical for adult periodontitis. Further marker of periodontitis were Spirochetes, Synergistetes, Firmicutes, and Chloroflexi whereas Actinobacteria, especially Actinomyces, was attributed a rather protective value 110 . Since very recent data consider reduction of alpha diversity as hint for periodontitis without mentioning specific microorganisms, the scientific discussion seems to be controversial 111 . Twin studies indicate that the genetic influence on the oral microbiome is subordinate to the environment, in particular nutrition 109 . Pregnancy also has a subordinate impact on the composition of the subgingival microbiome 112 . In contrast, a genetic disposition for caries seems to favor this disease in a higher measure than the microbiome of the dental plaque 113 . Nonetheless, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Actinomyces, Granulicatella, Leptotrichia, and Thiomonas 114 , Streptococcus, Granulicatella, and Actinomyces 115 , and Streptococcus and Veillonella (in children younger than 30 months) 116 were frequently found with simultaneously present caries. More favorable and without caries detection is probably a microbiome containing Leptotrichia, Selenomonas, Fusobacterium, Capnocytophaga, or Porphyromonas 116 .

4.4.1 Microbiome of saliva

Saliva contains an extremely high number of microorganisms 117 118 including Streptococcus, Dialister, and Veillonella 119 . Comparing the saliva of different ages, the alpha diversity in children seems to be higher while the absolute abundance in adults is higher with similar composition of the taxa 120 . The central healthy microbiome of saliva encompassed the taxa of Streptococcus, Prevotella, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Porphyromonas, Gemella, Rothia, Granulicatella, Fusobacterium, Actinomyces, Veillonella, and Aggregatibacter 120 or Streptococcus, Prevotella, Haemophilus, Lactobacillus, and Veillonella 121 , respectively. Lower percentages of Neisseria, Aggregatibacter (Proteobacteria), Haemophilus (Firmicutes), and Leptotrichia (Fusobacteria) could be detected in patients with squamous cell carcinomas of the oral cavity or the oropharynx 121 . Higher rates of Neisseria, Aggregatibacter, Haemophilus, or Leptotrichia, however, indicated a possible tumor development. A higher sugar percentage in the mouth, e. g. in the context of diabetes mellitus type II, reduces the absolute abundance of microorganisms in the saliva and shifts the relative abundance in adolescents 122 . Only some studies could confirm a correlation with caries 123 , other could not 124 . However, there seems to be an association with poor oral hygiene 125 .

Technically, the circadian rhythms of immunoglobulin A production in the saliva is important. Regarding sampling, aspiration turned out to be superior to swabs 126 . Furthermore, also the detection of different bacteria such as Firmicutes including Streptococcus and Gemella, and Bacteroidetes including Prevotella 127 is subject to variation. Accordingly, the times of the day when sampling is performed should be reported in studies on the microbiome of saliva.

From a technical point of view, it is of fundamental importance to perform an investigation on the re-test-reliability of the microbiome data of saliva 128 . Sampling performed every 2 months over one year revealed significantly different absolute frequencies of the detected taxa, even on the level of phyla, and interindividual differences regarding the composition of the microbiome with significantly different alpha diversity. Also the pH value of the saliva varied in the course of the year 128 . Those data relativize the interpretations of differences in the microbiome (also of other areas), while the authors allot the observed effects to the seasons. Specimens that were taken in shorter intervals of e. g. one week, seem to be more stable with regard to their reliability 129 . Because of the stronger influence of the environment of the individual compared to genetics 130 , the suggestion was made to take this fact into account for recruiting control groups.

More than 70% of the DNA in the saliva can be allotted to bacteria, only less than 1% belongs to viruses 131 . The salivary microbiome is increasingly examined in the context of systemic diseases, e. g. in order to diagnose more easily autoimmune diseases 132 or for early cancer diagnosis 133 . So the microbiome in M. Behcet patients seems to be less diverse with a high abundance of Haemophilus parainfluenzae, but a clear reduction of Alloprevotella rava and genu Leptotrichia 134 .

The application of amoxicillin for 5 days increased the relative abundance of Veillonellaceae, Actinomycetaceae, Neisseriaceae, Prevotellaceae, and Porphyromonadaceae while Streptococcaceae and Gemellaceae decreased. In contrast, the application of azithromycin led to an increase of Bifidobacteriales and Veillonellaceae while Clostridiales, Neisseriaceae, and Erysipelotrichaceae were reduced 119 .

For stimulation of the immune defense, possibly the intake of Lactobacillus kunkeei YB38 is useful because it increased the immunoglobulin A secretion in the saliva in a mouse model 135 . In contrast, the oral intake of Lactobacillus paracasei F19 had no influence on the incidence of caries in children between 4 and 13 months 136 . The regular application of commercially available probiotics reduced the detection of fungi significantly, especially Candida albicans 137 , but the clinical relevance is not yet confirmed. At the same time, the alpha diversity of the salivary microbiome seems to increase when probiotics are applied 138 . Another aspect of the interventional study investigated the influence of xylitol or sorbitol containing chewing gum on the microbiome. Children were asked to eat about 6 g per day as chewing gum for 5 weeks. While xylitol reduced Streptococci detectable by means of culture, sorbitol led to a significant decrease of Veillonella atypica in the salivary microbiome 139 .

4.5 Pharyngeal space

Streptococci dominate the microbiome of healthy tonsils with a relative abundance of almost 70% 78 . In the pharynx, this dominance is not so high with about 50%, followed by Fusobacteria (about 8%) and Prevotella (about 7%) 140 141 142 . Within Waldeyer’s tonsillar ring, sampling reveals a high variance only due to the exact location (e. g. posterior pharyngeal wall versus palatine tonsil) 143 .

Tonsillar hyperplasia in children leads to the detection of Streptococcus (21.5%), Neisseria (13.5%), Prevotella (12.0%), Haemophilus (10.2%), Porphyromonas (9.0%), Gemella (8.6%), and Fusobacteria (6.4%) 144 145 . Children suffering from PFAPA syndrome (periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis) have a different microbiome on their palatine tonsil. It is characterized by an increased detection and increased relative abundance of Cyanobacteria to the detriment of the relative abundance of Streptococci 146 .

In cases of chronic tonsillitis, the culture-based identification of pathogens is successful only in about 60% 147 148 . Anaerobes are found in about 40–60% of the patients at the surface and in nearly 50% within the palatine tonsil 143 147 . Most frequently, Porphyromonas is found. Chronic tonsillitis in adults seems to be associated with Fusobacterium necrophorum, Streptococcus intermedius, and Prevotella melaninogenica/histicola 144 145 .

An interventional study on the influence of gargling with benzethonium chloride in patients with halitosis could not reveal any changes of the tonsillar microbiome 149 .

4.5.1 Excursion: Microbiome and immune system

The basis of the functional significance of the microbiome in the pathogenesis of different immune mediated diseases is the modulation of the innate as well as adaptive immunity due to the microbiome and vice versa the influence of immune cells on the microbiome 150 . The microbiome influences the immunity especially via interleukin 18 and 22 mediated signaling pathways 151 152 . In addition, microbiome and B and T cells may influence each other and thus the microbiome can have an influence on the adaptive immune system 150 .

In this context it should be mentioned as an example, that women show a higher correlation between tonsillectomy and the occurrence of sarcoidosis (odds ratio: 3.30; 95% confidence interval 0.88–12.39) compared to males (odds ratio: 1.26; 95% confidence interval 0.10–16.52) 153 . This indicates a possible influence of the pharyngeal microbiome on the development of autoimmune diseases in a similar way as the data on the effectiveness of chemotherapies with different microbiomes (see below).

4.6 Larynx

The laryngeal microbiome is significantly different from the one of the pharynx 140 . Primarily, consistent Firmicutes, Proteobacteria, and Bacteroidetes are reported 154 . More detailed investigations also state incidences: the detected phyla encompass Firmicutes (54%), Fusobacteria (17%), Bacteroidetes (15%), Proteobacteria (11%), and Actinobacteria (3%). The identified genu include Streptococcus (36%), Fusobacterium (15%), Prevotella (12%), Neisseria (6%), and Gemella (4%) 140 .

Another investigation of the same group revealed a broad variance of the taxa with different percentages 155 . The phyla Firmicutes (46.4%), Bacteroidetes (18.7%), Fusobacteria (16.9%), Proteobacteria (13.0%), and Actinobacteria (2.4%) could be found which confirmed earlier results. The genu Streptococcus (41.7%), Helicobacter (2.6%), and Haemophilus (2.3%) showed a similar dominance. In comparison to the location of the vocal folds, the microbiome of the false vocal folds is not significantly different 13 . Technically, the results of biopsies and swabs were similar so that less invasive techniques for studies and control tissues are justified 13 .

4.7 Trachea

In newborns, Acinetobacter can be reliably detected as part of the tracheal microbiome 156 . So the general assumption that the airways of newborns and especially the trachea are sterile seems to be disproved. A reduced alpha diversity of the tracheal microbiome indicates an increased risk to develop a specific chronic pulmonary disease, i. e. bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Likewise, the oral and tracheal diversity in intubated patients was reduced. Often the taxa detected by means of sequencing could not be identified by means of culturing 157 . Intubated patients with pneumonia had a better prognosis with a relative abundance of <4.6% of Pseudomonas and <70.8% of Staphylococci 158 . Tracheostomized patients often showed Haemophilus in the microbiome in cases of infection. This increase occurred to the detriment of Acinetobacter, Corynebacterium, and Pseudomonas. In the context of infection, alpha and beta diversity decrease significantly 159 .

4.8 Esophagus

4.8.1 Gastro-esophageal reflux

An investigation revealed that reflux has no impact on the laryngeal microbiome 160 . The application of proton pump inhibitors in newborns with gastro-esophageal reflux 161 neither changed significantly the alpha nor the beta diversity but representatives of the genu Lactobacillus and Stenotrophomonas decreased to the detriment of Haemophilus. After therapy interruption, the alpha and beta diversity re-increased together with the relative abundance of the phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria. In this way, the microbiome reflects the age and the diet.

4.8.2Neoplasms

Squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas are the most frequently occurring malignant neoplasm in the area of the esophagus. The development of an adenocarcinoma seems to be favored by gastro-esophageal reflux that also influences the complex microbiome of the esophagus and is possibly a co-factor of the pathophysiology of Barrett’s esophagus 162 . The relative risk to develop an adenocarcinoma amounts to 30–400 in gastro-esophageal reflux patients 163 .

The normal microbiome of the esophagus seems to be characterized by Gram-positive bacteria (phylum Firmicutes, especially with genus Streptococcus) 164 . Reflux as well as Barrett’s esophagus changed this image in favor of more Gram-negative anaerobes of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, and Spirochetes). In addition, the relative incidence of taxa seems to be more important for the pathophysiology than the absolute quantity of bacteria. So more frequently, Veillonellae (19%), Prevotellae (12%), Neisseriae (4%), and Fusobacteria (9%) were detected in the context of reflux disease or Barrett’s esophagus.

In order to better examine the impact of gastro-esophageal reflux for example also on the risk to develop ENT-specific cancer, data material from the NordASCo cohort 165 is currently evaluated. A total of 945,153 patients with gastro-esophageal reflux from Scandinavian countries were assessed, 48,433 (5.1%) of them underwent surgical intervention for reflux control.

5. Head and Neck Cancer and its Treatment

5.1 Carcinogenesis

Currently it is assumed that about 20% of all cancer diseases are caused by microbial pathogens 166 . In otorhinolaryngology, e.g.the role of human papillomavirus is acknowledged. A shift within the microbiome may additionally favor carcinogenesis via chronic inflammations because protecting factors such as protective microbial peptides are missing, toxins accumulate or pathogens proliferate. Even after the development of malignant neoplasms, the microbiome plays an important role. Microorganisms or their metabolites may have an oncogenetic effect, favor tumor growth, provide growth factors, and develop pro-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects that weaken the endogenous mechanisms of tumor defense.

However, it is a problem to differentiate tumor-associated, rather accompanying changes from those with causal relation. So an increased risk of cancer was proven in dependence of antibiotic application 167 . The risk to develop malignant neoplasms in the area of the oral cavity and the pharynx increases to the relative risk of 1.38 (1.17–1.64; age and gender adapted)in cases of 6 or more prescriptions of antibiotics. In the larynx, the risk to develop neoplasms was even higher with 1.45 (1.08–1.94).

Changes of the oral microbiome are strongly associated with the occurrence of tumors of the oral cavity 168 . A meta-analysis of 8 studies revealed an increased risk of 2.63 (95% confidence interval: 1.68–4.14) to develop malignant neoplasm of the head and neck in cases of periodontitis 169 . Since – as described above – it is associated with changes of the oral microbiome, also differences in the occurrence of head and neck tumors can be expected.

Accordingly, a case control study using specimens of the pharynx, larynx, and also metastases of head and neck tumors showed a lower alpha diversity in tumors compared to normal mucosa of the same location 170 .

Comparing the normal mucosa between the location of the primary tumor as well as a metastasis, the beta diversity reveals significant differences but also between the primary tumor and the metastasis, the beta diversity was clearly different. In comparison to the physiological microbiome of the oral cavity, the tumor microbiome is characterized by the increased incidence of Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Spirochetes, and Fusobacteria with decrease of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria. Primary tumor of the larynx and pharynx revealed an increased colonization with Fusobacteria and decrease of Firmicutes. Finally, Fusobacteria also increased in metastases and especially the percentage of the species Streptococci from the phylum of Firmicutes decreased. Additionally, the detection rate of Proteobacteria was higher.

Furthermore, the risk to develop a lymphoma is explained based on microbiome-assisted approaches. Scandinavian investigations indicate a seropositivity with Borrelia burgdorferi 171 172 . MALT lymphomas in different non-gastro-intestinal organs revealed Chlamydophila psittaci 173 174 .

5.2 Microbiome and checkpoint inhibitors

Approved for treatment of head and neck cancer or in the testing phase are currently antibodies that inhibit PD1 (programmed cell death protein 1, also CD279) or CTLA4 (cytotoxic T lymphocyte associated antigen 4) 175 . PD1 or checkpoint inhibitors were approved for Germany only in the last months (such as Nivolumab). Others are expecting approval here and are already approved by the FDA for treatment of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck (such as Pembrolizumab) 176 . PD1 is expressed by activated T lymphocytes, B cells, natural killer T cells (NKT), and Treg cells 177 . They belong to the family of CD28 co-receptors 178 . Hereby, the ligands PD1 and PD2 bind to those receptors; apparently only PD1 is expressed by tumor cells beside antigen presenting cells (e. g. macrophages 179 , 180 ). Furthermore, the expression of PDL1 in some squamous cell carcinomas (skin 181 ) is associated with the tumor stage while the expression of PDL2 is rather determined by the tumor size and the differentiation 181 .

The ligands of PD1 and PDL1 are located in the tumor environment and help that the tumor cells escape from the immune reaction of the host 182 183 . The blockade of this binding causes a clear increase of interferon gamma (IFN-gamma) 184 and thus a significant change of the microenvironment around the tumor. The production of IFN-gamma can be influenced by the intestinal microbiome 185 . Ruminococcus (Gram-negative) as well as Alistipes (Gram-positive) are associated with IFN-gamma production. In contrast, a microbiome enhanced with Lactobacillus can nearly inhibit this IFN-gamma production. Investigations in an animal model of mice indicate that the microbiome may strengthen the effectiveness of anti-PDL1 therapy. Hereby, a microbiome with a high percentage of Bifidobacter shows an improved response.

CTLA4, however, is a global immune defense (checkpoint) to modulate immune responses by down-regulation of CD4+ T effector (Teff) cells and enhanced Treg cell activity 182 183 . Even via this mechanism, the microbiome seems to influence the response of cancer therapies. Mice that are without bacterial colonization or after antibiotic therapy, only show low effects of anti-CTLA4 therapy 186 . Reversely, the CTLA4 treatment modifies the microbiome 186 . Finally, an immune-triggered colitis under CTLA4 therapy with Ipilimumab can be avoided by Bacteroides phlilym enhancement 187 . Furthermore, oral therapy with the antibiotic vancomycin improves CTLA4 immunotherapy 186 .

In an animal model of genetically identical mice with melanoma induction, clearly different response rates on the different microbiome of animals of 2 different breeders could be explained and traced back to the positive effect of Bifidobacteria. The application of Bifidobacteria in animals with poorer response could improve tumor control and IFN-gamma production 188 .

So the microbiome may be considered as biomarker for the therapy response or an approach to positively influence the effectiveness of a therapy.

5.3 Outlook

The treatment of the microbiome opens a completely new field of therapeutic options depending on the material used. Stool transplantation for treatment of Clostridium difficile was classified as treatment with a pharmaceutic by the Federal Institute for Pharmaceutics and Medical Products (Bundesinsitut für Arzneimittel und Medizinprodukte, BfArM) even if a reproducible production of stool according to current pharmacological understanding is currently not possible. So here, a grey area exists that has to be considered critically with regard to probiotic therapies – also in the head and neck. The discussion of modifying the microbiome even by “only” one single antibiotic application helps questioning the prescription behavior under this aspect. Based on the current German guidelines for tonisllectomy, 5-6 antibiotic therapies are previously required, however, in the future data assessment evaluating secondary damage of the microbiome with their impact on the host are reasonable and may help to verify a possibly earlier intervention. Because of the interactions between host and microbiome, also independent from a disease and currently limited knowledge, the microbiome turned out to be an unscheduled parameter of future therapies.

Footnotes

Interessenkonflikt Der Autor gibt an, dass Honorare für Vortragstätigkeiten für die Firmen Pohl-Boskamp, Essex Pharma und Happersberger Otopront gezahlt wurden und er an der Durchführung von Drittmittel-Studien nach AMG für Allakos, Sanofi und GlaxoSmithKline beteiligt war bzw. ist.

Literatur

- 1.Smith K, McCoy K D, Macpherson A J. Use of axenic animals in studying the adaptation of mammals to their commensal intestinal microbiota. Semin Immunol. 2007;19:59–69. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sears C L, Pardoll D M. Perspective: alpha-bugs, their microbial partners, and the link to colon cancer. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:306–311. doi: 10.1093/jinfdis/jiq061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu L, Baker S S, Gill C et al. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology. 2013;57:601–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu Q, Gao R, Wu W et al. The role of gut microbiota in the pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:1285–1300. doi: 10.1007/s13277-013-0684-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheflin A M, Whitney A K, Weir T L. Cancer-promoting effects of microbial dysbiosis. Curr Oncol Rep. 2014;16:406. doi: 10.1007/s11912-014-0406-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boone D R, Castenholz R W, Garrity G M . Springer; 2001. Bergey's Manual ® of Systematic Bacteriology . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stallmach A, Vehreschild MJG T. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG; 2016. Mikrobiom: Wissensstand und Perspektiven. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roesch L F, Casella G, Simell O et al. Influence of fecal sample storage on bacterial community diversity. Open Microbiol J. 2009;3:40–46. doi: 10.2174/1874285800903010040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tal M, Verbrugghe A, Gomez D E et al. The effect of storage at ambient temperature on the feline fecal microbiota. BMC. Vet Res. 2017;13:256. doi: 10.1186/s12917-017-1188-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll I M, Ringel-Kulka T, Siddle J P et al. Characterization of the fecal microbiota using high-throughput sequencing reveals a stable microbial community during storage. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46953. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kia E, Wagner Mackenzie B, Middleton D et al. Integrity of the Human Faecal Microbiota following Long-Term Sample Storage. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0163666. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bai G, Gajer P, Nandy M et al. Comparison of storage conditions for human vaginal microbiome studies. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36934. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanshew A S, Jette M E, Tadayon S et al. A comparison of sampling methods for examining the laryngeal microbiome. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174765. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bassiouni A, Cleland E J, Psaltis A J et al. Sinonasal microbiome sampling: a comparison of techniques. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0123216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumar R, Eipers P, Little R B et al. Getting started with microbiome analysis: sample acquisition to bioinformatics. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2014;82:18 18 11–18 18 29. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg1808s82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodrich J K, Di Rienzi S C, Poole A C et al. Conducting a microbiome study. Cell. 2014;158:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Navas-Molina J A, Peralta-Sanchez J M, Gonzalez A et al. Advancing our understanding of the human microbiome using QIIME. Methods Enzymol. 2013;531:371–444. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407863-5.00019-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caporaso J G, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Walters W A et al. Using QIIME to analyze 16S rRNA gene sequences from microbial communities. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2012;Chapter 1:Unit 1E 5. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc01e05s27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leray M, Knowlton N. Visualizing Patterns of Marine Eukaryotic Diversity from Metabarcoding Data Using QIIME. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1452:219–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-3774-5_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawley B, Tannock G W. Analysis of 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequences Using the QIIME Software Package. Methods Mol Biol. 2017;1537:153–163. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6685-1_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schloss P D, Westcott S L, Ryabin T et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–7541. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang S, Liebner S, Alawi M et al. Taxonomic database and cut-off value for processing mcrA gene 454 pyrosequencing data by MOTHUR. J Microbiol Methods. 2014;103:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N et al. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:82–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Lilburn T G et al. The RDP-II (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:173–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole J R, Chai B, Farris R J et al. The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D294–D296. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bacci G, Bani A, Bazzicalupo M et al. Evaluation of the Performances of Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) Classifier for Taxonomic Assignment of 16S rRNA Metabarcoding Sequences Generated from Illumina-Solexa NGS. J Genomics. 2015;3:36–39. doi: 10.7150/jgen.9204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huse S M, Mark Welch D B, Voorhis A et al. VAMPS: a website for visualization and analysis of microbial population structures. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Suzuk Yildiz S, Kaskatepe B, Altinok S et al. [Comparison of MALDI-TOF and 16S rRNA methods in identification of viridans group streptococci] Mikrobiyol Bul. 2017;51:1–9. doi: 10.5578/mb.46504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barberis C, Almuzara M, Join-Lambert O et al. Comparison of the Bruker MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry system and conventional phenotypic methods for identification of Gram-positive rods. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Funke G, von Graevenitz A, Clarridge J E, 3rd et al. Clinical microbiology of coryneform bacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1997;10:125–159. doi: 10.1128/cmr.10.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allali I, Arnold J W, Roach J et al. A comparison of sequencing platforms and bioinformatics pipelines for compositional analysis of the gut microbiome. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17:194. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1101-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawinkel S, Mattiello F, Bijnens L et al. A broken promise: microbiome differential abundance methods do not control the false discovery rate. Brief Bioinform. 2017 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lemos L N, Fulthorpe R R, Triplett E W et al. Rethinking microbial diversity analysis in the high throughput sequencing era. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;86:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stulberg E, Fravel D, Proctor L M et al. An assessment of US microbiome research. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:15015. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2015.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spor A, Koren O, Ley R. Unravelling the effects of the environment and host genotype on the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:279–290. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slifierz M J, Friendship R M, Weese J S. Longitudinal study of the early-life fecal and nasal microbiotas of the domestic pig. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:184. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0512-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thevaranjan N, Whelan F J, Puchta A et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae Colonization Disrupts the Microbial Community within the Upper Respiratory Tract of Aging Mice. Infect Immun. 2016;84:906–916. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01275-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renteria A E, Mfuna Endam L, Desrosiers M. Do Aging Factors Influence the Clinical Presentation and Management of Chronic Rhinosinusitis? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156:598–605. doi: 10.1177/0194599817691258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whelan F J, Verschoor C P, Stearns J C et al. The loss of topography in the microbial communities of the upper respiratory tract in the elderly. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11:513–521. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-351OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Biagi E, Nylund L, Candela M et al. Through ageing, and beyond: gut microbiota and inflammatory status in seniors and centenarians. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10667. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Beek A A, Hugenholtz F, Meijer B et al. Frontline Science: Tryptophan restriction arrests B cell development and enhances microbial diversity in WT and prematurely aging Ercc1-/Delta7 mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2017;101:811–821. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1HI0216-062RR. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneeberger M, Everard A, Gomez-Valades A G et al. Akkermansia muciniphila inversely correlates with the onset of inflammation, altered adipose tissue metabolism and metabolic disorders during obesity in mice. Sci Rep. 2015;5:16643. doi: 10.1038/srep16643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez A, Luckey D, Taneja V. The gut microbiome in autoimmunity: Sex matters. Clin Immunol. 2015;159:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C et al. Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:1027–1033. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.2.1027-1033.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J, Peters B A, Dominianni C et al. Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults. ISME J. 2016;10:2435–2446. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Charlson E S, Chen J, Custers-Allen R et al. Disordered microbial communities in the upper respiratory tract of cigarette smokers. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee J, Taneja V, Vassallo R. Cigarette smoking and inflammation: cellular and molecular mechanisms. J Dent Res. 2012;91:142–149. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verna L, Whysner J, Williams G M. N-nitrosodiethylamine mechanistic data and risk assessment: bioactivation, DNA-adduct formation, mutagenicity, and tumor initiation. Pharmacol Ther. 1996;71:57–81. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(96)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang L, Ganly I. The oral microbiome and oral cancer. Clin Lab Med. 2014;34:711–719. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labriola A, Needleman I, Moles D R. Systematic review of the effect of smoking on nonsurgical periodontal therapy. Periodontol 2000. 2005;37:124–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2004.03793.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coretti L, Cuomo M, Florio E et al. Subgingival dysbiosis in smoker and nonsmoker patients with chronic periodontitis. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:2007–2014. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2017.6269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yu G, Phillips S, Gail M H et al. The effect of cigarette smoking on the oral and nasal microbiota. Microbiome. 2017;5:3. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0226-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Peralbo-Molina A, Calderon-Santiago M, Jurado-Gamez B et al. Exhaled breath condensate to discriminate individuals with different smoking habits by GC-TOF/MS. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1421. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-01564-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Filipiak W, Ruzsanyi V, Mochalski P et al. Dependence of exhaled breath composition on exogenous factors, smoking habits and exposure to air pollutants. J Breath Res. 2012;6:36008. doi: 10.1088/1752-7155/6/3/036008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Falana K, Knight R, Martin C R et al. Short Course in the Microbiome. J Circ Biomark. 2015;4:8. doi: 10.5772/61257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenberg D, Givon-Lavi N, Broides A et al. The contribution of smoking and exposure to tobacco smoke to Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae carriage in children and their mothers. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:897–903. doi: 10.1086/500935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turnbaugh P J, Backhed F, Fulton L et al. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaczmarek J L, Musaad S M, Holscher H D. Time of day and eating behaviors are associated with the composition and function of the human gastrointestinal microbiota. Am J Clin Nutr. 2017;106:1220–1231. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.117.156380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson G R, Roberfroid M B. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota: introducing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr. 1995;125:1401–1412. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Staudacher H M, Whelan K. Altered gastrointestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome and its modification by diet: probiotics, prebiotics and the low FODMAP diet. Proc Nutr Soc. 2016;75:306–318. doi: 10.1017/S0029665116000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walsh C J, Guinane C M, O'Toole P W et al. Beneficial modulation of the gut microbiota. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4120–4130. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Goncalves D et al. Microbiota-generated metabolites promote metabolic benefits via gut-brain neural circuits. Cell. 2014;156:84–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cleland E J, Drilling A, Bassiouni A et al. Probiotic manipulation of the chronic rhinosinusitis microbiome. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:309–314. doi: 10.1002/alr.21279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Manning J, Dunne E M, Wescombe P A et al. Investigation of Streptococcus salivarius-mediated inhibition of pneumococcal adherence to pharyngeal epithelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 2016;16:225. doi: 10.1186/s12866-016-0843-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Cancer Research Fund / American Institute for Cancer Research. Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. Washington DC: AICR 2007. Nachlesbar unter http://www.aicr.org/assets/docs/pdf/reports/Second_Expert_Report.pdf; ISBN: 978-0-9722522-2-5

- 68.Muto M, Hitomi Y, Ohtsu A et al. Acetaldehyde production by non-pathogenic Neisseria in human oral microflora: implications for carcinogenesis in upper aerodigestive tract. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:342–350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dubinkina V B, Tyakht A V, Odintsova V Y et al. Links of gut microbiota composition with alcohol dependence syndrome and alcoholic liver disease. Microbiome. 2017;5:141. doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0359-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mangin I, Leveque C, Magne F et al. Long-term changes in human colonic Bifidobacterium populations induced by a 5-day oral amoxicillin-clavulanic acid treatment. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.De La Cochetiere M F, Durand T, Lepage P et al. Resilience of the dominant human fecal microbiota upon short-course antibiotic challenge. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5588–5592. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5588-5592.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pols DH J, Nielen MM J, Bohnen A M et al. Atopic children and use of prescribed medication: A comprehensive study in general practice. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0182664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0182664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Feazel L M, Santorico S A, Robertson C E et al. Effects of Vaccination with 10-Valent Pneumococcal Non-Typeable Haemophilus influenza Protein D Conjugate Vaccine (PHiD-CV) on the Nasopharyngeal Microbiome of Kenyan Toddlers. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128064. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jespersen L, Tarnow I, Eskesen D et al. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L. casei 431 on immune response to influenza vaccination and upper respiratory tract infections in healthy adult volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101:1188–1196. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.103531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chan C L, Wabnitz D, Bardy J J et al. The microbiome of otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope. 2016;126:2844–2851. doi: 10.1002/lary.26128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Krueger A, Val S, Perez-Losada M et al. Relationship of the Middle Ear Effusion Microbiome to Secretory Mucin Production in Pediatric Patients With Chronic Otitis Media. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36:635–640. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jervis-Bardy J, Rogers G B, Morris P S et al. The microbiome of otitis media with effusion in Indigenous Australian children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:1548–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu C M, Cosetti M K, Aziz M et al. The otologic microbiome: a study of the bacterial microbiota in a pediatric patient with chronic serous otitis media using 16SrRNA gene-based pyrosequencing. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:664–668. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Santos-Cortez R L, Hutchinson D S, Ajami N J et al. Middle ear microbiome differences in indigenous Filipinos with chronic otitis media due to a duplication in the A2ML1 gene. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:97. doi: 10.1186/s40249-016-0189-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fokkens W J, Lund V J, Mullol Jet al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2012Rhinol Suppl 2012233p preceding table of contents, 1-298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zuliani G, Carron M, Gurrola J et al. Identification of adenoid biofilms in chronic rhinosinusitis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:1613–1617. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2006.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Beule A G, Hosemann W.[Bacterial biofilms] Laryngorhinootologie 200786886–895.quiz 896–889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Subtil J, Rodrigues J C, Reis L et al. Adenoid bacterial colonization in a paediatric population. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;274:1933–1938. doi: 10.1007/s00405-017-4493-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Taylan I, Ozcan I, Mumcuoglu I et al. Comparison of the surface and core bacteria in tonsillar and adenoid tissue with Beta-lactamase production. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]