Objective:

We sought to define the MRI findings in the bell clapper deformity (BCD) and to retrospectively evaluate its diagnostic ability.

Methods:

The cases of eight patients who underwent MRI and surgery for acute scrotum between January 2010 and January 2017 were evaluated. We recorded whether hyperintense fluid on T2 weighted images existed between the posterior aspect of the epididymis and the scrotal wall (“split sign”) and investigated if it correlated with BCD in surgical findings.

Results:

In one patient without hydrocele, readers were unable to evaluate the anatomy of the tunica vaginalis. Among seven patients with hydrocele, five had the split sign and all were surgically confirmed as BCD. In two patients with hydrocele but no split sign, one had normal scrotal anatomy and the other had a BCD with a necrotic testis adherent to the scrotal wall.

Conclusion:

The split sign on MRI corresponded well to the lack of fixation of the epididymis to the scrotal wall and detected BCD with high sensitivity (5/6).

Advances in knowledge:

A hyperintense area on T2 weighted image between the posterior aspect of the epididymis and scrotal wall (“split sign”) is a useful MRI finding for diagnosing BCD.

INTRODUCTION

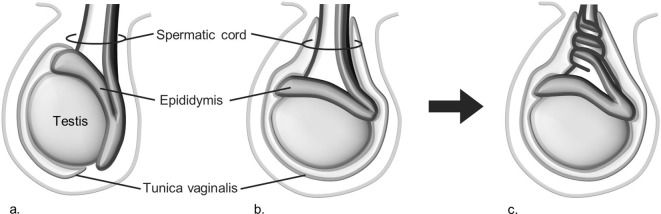

Testicular torsion can occur either extravaginally or intravaginally, each with different etiological factors and susceptible age groups. Extravaginal torsion is seen in the normal foetus and neonate because of the loose attachment of the tunica vaginalis to the internal spermatic fascia.1 After the neonatal period, a fully descended, correctly situated, and properly fixed testis rarely undergoes torsion. However, some scrotal malformations are known to increase the risk of intravaginal testicular torsion. The bell clapper deformity (BCD) is an important risk factor for intravaginal testicular torsion.2,3 In BCD, the tunica vaginalis covers the entire testicle and distal spermatic cord (Figure 1), allowing the testis to swing and rotate freely within the tunica vaginalis.4 This condition is similar to the clapper inside a bell, hence the term.5

Figure 1.

Schema of normal scrotum (a), bell clapper deformity (b), and torsion (c). Note the difference in the attachment site of the tunica vaginalis.

Diagnosing BCD on imaging studies will be helpful in the evaluation of the acute scrotum. However, it is difficult to directly visualize the attachments of the tunica vaginalis and there is currently no study showing the precise imaging findings of BCD.

MRI has recently been used to evaluate the acute scrotum, particularly in cases that are difficult to evaluate by ultrasonography.6–8 MRI has the ability to depict the precise structures of the scrotum with high tissue contrast and enables objective evaluation. The aim of this study was to establish the MRI findings of BCD and retrospectively evaluate their diagnostic ability.

Methods and materials

The Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study and waived the informed consent requirement. All data used for the present study were obtained from electronic medical records and images.

Patient population

22 consecutive patients underwent MRI for acute scrotum between January 2010 and January 2017, and 17 subsequently underwent surgery. Among the 17 patients, 8 were excluded because their operative records did not identify the presence or absence of BCD and 1 was also excluded because of a previous history of orchidopexy. Therefore, 8 patients (median age, 14 y; range, 10–26 y) were included in the present study. Final diagnoses at surgery were testicular torsion (n = 6), appendix testis torsion (n = 1), and segmental testicular infarction (n = 1).

All the patients underwent physical examination and ultrasound imaging. They also underwent MRI since physical examination and ultrasound were unable to confirm their diagnoses or to increase diagnostic certainty before the surgery.

All contralateral testicles were surgically confirmed to have no torsion; however, the presence or absence of BCD was not specified in their operative records. Therefore, we only evaluated the affected testicles.

Data acquisition

MRI was performed with a 1.5 T (Achieva Nova Dual, PHILIPS, Best, The Netherlands; Intera Master, PHILIPS, Best, Netherlands) or 3.0 T scanner (MAGNETOM Skyra, SIEMENS, Erlangen, Germany) Magnetic resonance (MR) system. Patients were scanned in the supine position with a commercially available 15 cm circular surface coil at 1.5 T or a phased-array coil at 3 T, placed on the patient’s pelvis and scrotum. Axial and coronal T2 weighted fast spin-echo images were obtained. The parameters of T2 weighted images (T2WI) were as follows: repetition time, 4000–4641 ms; echo time, 90–99 ms; matrix, 256–320*256–320; section thickness, 3–5 mm with a 0.3–0.5 mm gap; and the field of view, 200 mm.

Diagnostic criteria for BCD on MRI

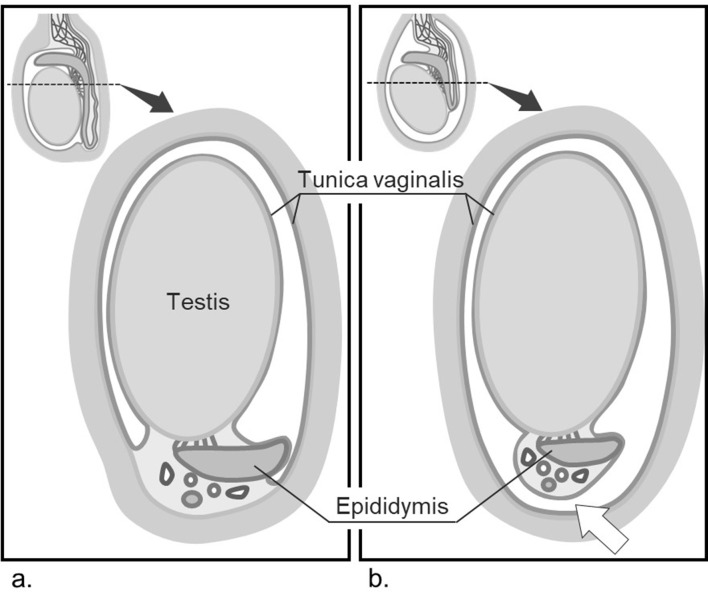

The tunica vaginalis normally envelops the anterior and lateral aspects of the testicle and attaches to the posterolateral aspect of the epididymis and lower pole of the testis.4 The posterior aspect of the epididymis is fixed to the scrotal wall, and thus, fluid will not be able to accumulate between these structures (Figure 2a). However, in BCD, the tunica vaginalis completely encircles the testicle and attaches to the distal spermatic cord.4 The epididymis is not fixed to the scrotal wall, and intravaginal fluid may divide these structures (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Cross-sectional anatomy of normal scrotum (a) and bell clapper deformity (b). In bell clapper deformity, the posterior aspect of epididymis is not fixed to the scrotal wall and intravaginal fluid may exist between these two structures (white arrow).

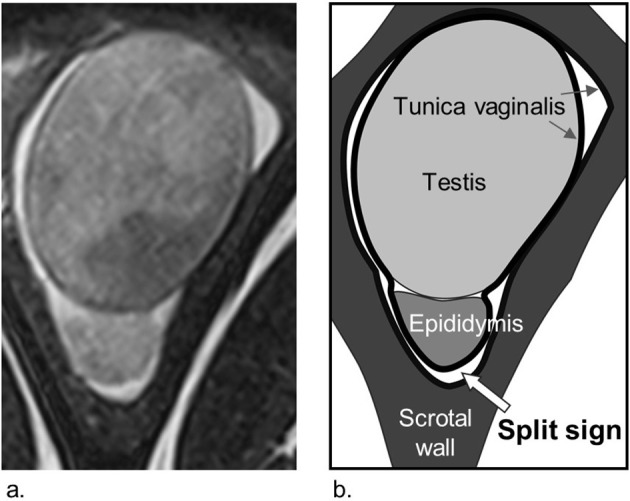

Based on the above-mentioned anatomical features, we speculated that the presence or absence of BCD might be evaluated by MRI as follows: A hyperintense area on T2WI dividing the posterior aspect of the epididymis from the scrotal wall (“split sign”) would suggest that the epididymis is not fixed to the scrotal wall (BCD) (Figure 3). When hydrocele is present, absence of the split sign suggests that the epididymis is fixed to the scrotal wall (no BCD) (Figure 4). When hydrocele is absent, absence of the split sign does not necessarily mean that the epididymis is fixed to the scrotal wall, and BCD cannot be evaluated by the split sign.

Figure 3.

An example of bell clapper deformity with a hydrocele on MRI (a) and schema (b). The split sign (white arrow), hyperintense area on T2WI between the posterior aspect of the epididymis and the scrotal wall, is observed. T2WI, T2 weighted image.

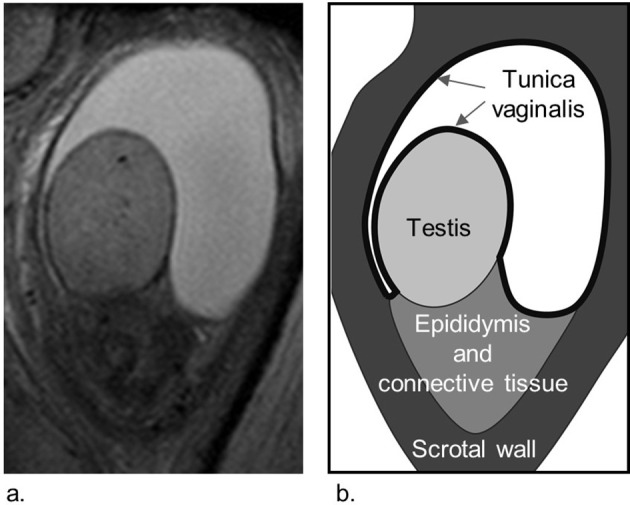

Figure 4.

An example of a normal scrotum with a hydrocele on MRI (a) and schema (b). The split sign is not observed.

Image analysis

All MR images were evaluated by two fellowship-trained radiologists (MK, HN) with 10 years of experience in interpreting pelvic MR images. They were blinded to any clinical information except for the affected side. Both axial and coronal T2WI were reviewed on a PACS monitor. The presence or absence of the split sign on the affected side of the scrotum was decided by consensus and results were compared with surgical findings.

Results

The clinical characteristics, ultrasound findings, MRI findings, and surgical findings of all eight patients are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics, MRI findings, and surgical findings of all eight patients

| Patient | Age (y) | Brief clinical history | Time from onset to MRI | Ultrasound findings | MRI findings | Surgical findings | |||

| Testicular blood flow | Hydrocele | Split sign | Surgical procedures | Diagnosis | Scrotal anatomy of affected side | ||||

| 1 | 14 | Sudden left scrotal pain | 4 h | Absent | + | + | Orchidopexy | Testicular torsion | BCD |

| 2 | 14 | Sudden left scrotal pain | 10 h | Absent | + | + | Orchidopexy | Testicular torsion | BCD |

| 3 | 12 | Left scrotal pain and swelling for two days | 48 h | Preserved | + | + | Orchiectomy | Testicular torsion | BCD |

| 4 | 21 | Right scrotal pain treated for three days as suspected epididymitis | 72 h | Decreased | + | + | Orchiectomy | Testicular torsion | BCD |

| 5 | 26 | Sudden left flank pain | 8 h | Decreased | + | + | Orchidopexy | Testicular torsion | BCD |

| 6 | 15 | Left scrotal pain and treated for a month as suspected epididymitis | 1 month | Decreased | + | – | Orchiectomy | Testicular torsion* | BCD |

| 7 | 10 | Recurring left scrotal pain and left scrotal swelling for a day | 24 h | Preserved | + | – | Excision of appendix testis | Appendix testis torsion | Normal |

| 8 | 19 | Sudden right scrotal pain | 5 h | Preserved | – | n/a | Exploratory surgery | Segmental testicular infarction | Normal |

*, Testicle was necrotic and adherent to the parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis; BCD, bell clapper deformity; n/a, not available.

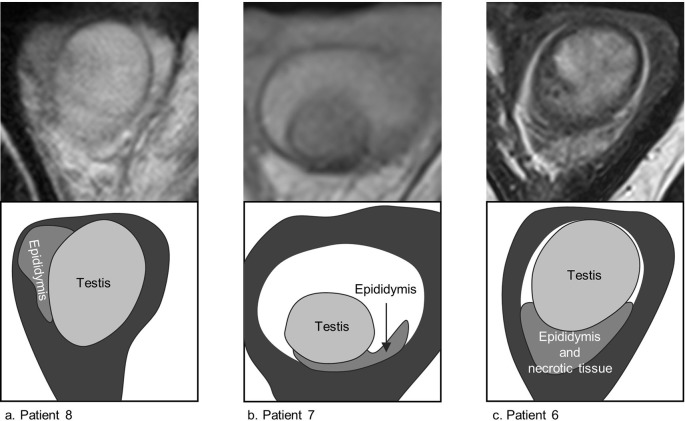

One patient, who had segmental testicular infarction without BCD, did not have a hydrocele (Figure 5a). Readers were unable to determine whether or not BCD was present by the split sign in this patient.

Figure 5.

MR images and schemas of a case with no hydrocele and two cases with no split sign. Patient 8 did not have hydrocele and readers were unable to determine whether BCD was present by the split sign (a). Surgery revealed segmental testicular infarction without BCD. Patient 7 with no split sign was surgically confirmed to have appendix testis torsion without BCD (b). Patient 6 with no split sign had testicular torsion with BCD, whose testicle was necrotic and adherent to the tunica vaginalis (c). BCD, bell clapper deformity.

Seven patients had hydroceles and were suitable for evaluating for the split sign. Five of them had the split sign, and all five patients were surgically confirmed to have testicular torsion with BCD. Of the two patients who did not have the split sign, one was confirmed to have appendix testis torsion without BCD (Figure 5b). The other had testicular torsion and BCD (Figure 5c). In this false-negative case, hyperintense signal was absent between the epididymis and the scrotal wall on T2WI because the testicle was necrotic and adherent to the parietal layer of the tunica vaginalis.

In summary, five out of six patients with BCD had the split sign, and all five patients with the split sign had BCD.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first detailed report on MRI findings of BCD. Resende et al9 and Munden et al10 reported that a reactive hydrocele completely surrounding the testis and epididymis could be of help to diagnose BCD in their reviews on scrotal ultrasound. These findings are considered to be essentially equivalent to the split sign on MRI, but the diagnostic ability compared with the surgical findings has not been verified. Also, Terai et al8 described that BCD could be suggested by an intravaginal effusion pattern on MRI, although they did not investigate the details of the effusion pattern. In the present study, we found that a hyperintense area between the posterior aspect of the epididymis and scrotal wall on T2WI corresponded well to the lack of fixation of these structures. The split sign detected BCD with high sensitivity (5/6).

The results of this study may contribute to the evaluation and management of acute scrotum. Detecting BCD may facilitate diagnosis of intravaginal testicular torsion since the prevalence of BCD in patients with intravaginal testicular torsion is as high as 86%; meanwhile it is reported to be approximately 12–16% in the general population.2,11 Pointing out the presence of BCD will increase confidence in the diagnosis of testicular torsion by combining the well-known MRI findings such as a hypointense area of the testis on T2WI, torsion knot and whirlpool patterns in the spermatic cord, and the lack of enhancement of the testis on contrast-enhanced T1 weighted imaging.6–8 Furthermore, detecting BCD may also help to diagnose intermittent testicular torsion. Intermittent testicular torsion is defined by a history of more than one attack of unilateral scrotal pain of sudden onset and of short duration that resolves spontaneously. Up to 50% of patients with acute testicular torsion have had previous episodes of testicular pain, suggesting intermittent testicular torsion precedes acute torsion.12 Because intermittent testicular torsion may resolve before imaging, the absence of classical imaging findings of testicular torsion can be often misleading.13 In these cases, detecting BCD may increase the possibility of diagnosis, and orchidopexy may then be required to prevent subsequent torsion.

Our study has some limitations. First, there was a low number of patients in this study, especially those without BCD (n = 2), of which only one was suitable for evaluation of the split sign. We therefore cannot calculate the statistically reliable diagnostic ability, especially with regard to specificity and negative predictive value. To more precisely evaluate the diagnostic ability of the split sign, further studies are needed, in larger populations, and especially targeting patients without BCD. Second, in our study, it was difficult to determine whether BCD was present or not without hydrocele. However, since reactive hydrocele formation is common in acute scrotum, many cases of acute scrotum may be suitable for evaluating BCD by the split sign.14

Conclusion

This preliminary study showed that loss of fixation of the epididymis to the scrotal wall, which is a key anatomical feature of BCD, was detected as a “split sign” on T2WI with high sensitivity. The clinical usefulness of diagnosing BCD needs to be evaluated in a larger population in future studies.

Contributor Information

Bunta Tokuda, Email: bunto9@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Maki Kiba, Email: mkiba@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Kaori Yamada, Email: b97b36@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Hitomi Nagano, Email: naganoh@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Hiroshi Miura, Email: miurak@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Mariko Goto, Email: gomari@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

Kei Yamada, Email: kyamada@koto.kpu-m.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kyriazis ID, Dimopoulos J, Sakellaris G, Waldschmidt J, Charissis G. Extravaginal testicular torsion: a clinical entity with unspecified surgical anatomy. Int Braz J Urol 2008; 34: 617–26. doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382008000500011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shittu OB, Idowu OE, Malomo AO, Ajani RSA. Intrascrotal anomalies related to testicular torsion in nigerians: an anatomical study. Afr J Urol 2006; 12: 24–8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Favorito LA, Cavalcante AG, Costa WS. Anatomic aspects of epididymis and tunica vaginalis in patients with testicular torsion. Int Braz J Urol 2004; 30: 420–4. doi: 10.1590/S1677-55382004000500014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin AD, Rushton HG. The prevalence of bell clapper anomaly in the solitary testis in cases of prior perinatal torsion. J Urol 2014; 191: 1573–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dogra V, deformity B-clapper. Bell-Clapper Deformity. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003; 180: 1176–7. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.4.1801176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watanabe Y, Nagayama M, Okumura A, Amoh Y, Suga T, Terai A, et al. MR imaging of testicular torsion: features of testicular hemorrhagic necrosis and clinical outcomes. J Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 26: 100–8. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trambert MA, Mattrey RF, Levine D, Berthoty DP. Subacute scrotal pain: evaluation of torsion versus epididymitis with MR imaging. Radiology 1990; 175: 53–6. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.1.2315504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Terai A, Yoshimura K, Ichioka K, Ueda N, Utsunomiya N, Kohei N, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction magnetic resonance imaging in diagnostics of testicular torsion. Urology 2006; 67: 1278–82. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Resende DdeAQP, Souza LRMFde, Monteiro IdeO, Caldas MHdeS. Scrotal collections: pictorial essay correlating sonographic with magnetic resonance imaging findings. Radiol Bras 2014; 47: 43–8. doi: 10.1590/S0100-39842014000100014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munden MM, Trautwein LM. Scrotal pathology in pediatrics with sonographic imaging. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2000; 29: 181–205. doi: 10.1016/S0363-0188(00)90013-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caesar RE, Kaplan GW. Incidence of the bell-clapper deformity in an autopsy series. Urology 1994; 44: 114–6. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(94)80020-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Creagh TA, McDermott TE, McLean PA, Walsh A. Intermittent torsion of the testis. BMJ 1988; 297: 525–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6647.525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Kandari AM, Kehinde EO, Khudair S, Ibrahim H, ElSheemy MS, Shokeir AA. Intermittent testicular torsion in adults: An overlooked clinical condition. Med Princ Pract 2017; 26: 30–4. doi: 10.1159/000450887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agrawal AM, Tripathi PS, Shankhwar A, Naveen C. Role of ultrasound with color Doppler in acute scrotum management. J Family Med Prim Care 2014; 3: 409–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]