Abstract

Background & Aims

Several studies have shown that bone marrow-derived committed myelomonocytic cells can repopulate diseased livers by fusing with host hepatocytes and can restore normal liver function. These data suggest that myelomonocyte transplantation could be a promising approach for targeted and well-tolerated cell therapy aimed at liver regeneration. We sought to determine whether bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells could be effective for liver reconstitution in newborn mice knock-out for glucose-6-phosphatase-α.

Methods

Bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells obtained from adult wild type mice were transplanted in newborn knockout mice. Tissues of control and treated mice were frozen for histochemical analysis, or paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological examination or analyzed by immunohistochemistry or fluorescent in situ hybridization.

Results

Histological sections of livers of treated knock-out mice revealed areas of regenerating tissue consisting of hepatocytes of normal appearance and partial recovery of normal architecture as early as 1 week after myelomonocytic cells transplant. FISH analysis with X and Y chromosome paints indicated fusion between infused cells and host hepatocytes. Glucose-6-phosphatase activity was detected in treated mice with improved profiles of liver functional parameters.

Conclusions

Our data indicate that bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cell transplant may represent an effective way to achieve liver reconstitution of highly degenerated livers in newborn animals.

Keywords: Glucose-6-phosphatase-α, Hematopoietic stem cells, Myelomonocytes, Cell fusion, Null mice

Introduction

Cell-based gene transfer is emerging as an achievable strategy for liver repopulation and represents one promising approach to treat liver diseases alternative to liver transplantation. Bone-marrow derived stem cells, such as hematopoietic and mesenchymal cells, possess the ability to give rise to functional hepatocytes mediating repair of liver damages [1,2]. Many animal models are being used to evaluate liver repopulation ability of bone-marrow-derived engrafted stem cells. Hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) have received a lot of attention after the demonstration that transplanted HSC can repopulate the liver of mice affected by fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase deficiency and lead to normal liver functions [3]. It was shown that liver reconstitution by HSCs arise from fusion between host hepatocytes and bone marrow-derived committed myelomonocytic cells (BMM) [4–6]. Liver engraftment is achieved when HSC-derived hepatocytes have a proliferative/survival advantage. This is the case when the host hepatocytes are defective as a consequence of genetic lesions, or when HSC transplant is performed during the fetal period, when the host liver is rapidly proliferating and differentiating [1]. This approach provides potential for targeted and well tolerated cell therapy aimed at liver regeneration. However, the fusion resulting in bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes (BMH) has a low frequency and it is a slow event in adult mice [7].

Many hereditary disorders precociously affect specific organs and the results of studies on newborn and adolescent mice support the concept that early gene transfer may be an important strategy for preventing the damages caused by the onset of the disease. Newborn gene transfer with viral vectors has been reported to be an effective therapy both in the liver and in the nervous system [8–15]. We have previously shown that newborns are particularly susceptible to lentiviral-mediated, liver targeted, gene delivery [16]. We found that very low doses of HIV-2-GFP could infect and be expressed in newborn mice and the efficiency of transduction was much greater in the newborn than in the adult mouse. The proliferative activity of newborn liver cells may be an important factor for the elevated virus transduction efficiency.

Based on this information, we sought to determine whether the BMM-mediated gene transfer could be effective in liver reconstitution of newborn mice with large liver damage. We utilized a mouse strain (G6pc−/−) knock out for the gene G6PC, which encodes glucose-6-phosphatase-α [17,18], a key enzyme in the glucose metabolism expressed primarily in the liver and kidney [19]. G6PC inactivation occurs in humans affected by the autosomal recessive disorder Glycogen Storage Disease Type 1a (GSD-1a) [20]. G6pc−/− mice show a very severe phenotype of disturbed glucose homeostasis. In fact most of G6pc−/− mice die shortly after birth and the liver lesions are mostly irreversible at 2 weeks of age [8].

We infused BMMs derived from wild type mice into newborn G6pc−/− mice. We show here that cell fusion between BMMs and host hepatocytes can be detected in the liver of treated mice as early as 2 weeks after BMM injection. We also show that Glucose-6-Phospatase (G6Pase) enzymatic activity is detectable in treated G6pc−/− mouse livers with concomitant improved profiles of liver functional parameters at 2- to 3-weeks from the treatment. Our data suggest that BMM transplant may represent an effective way to achieve reconstitution of highly degenerated livers in newborn animals.

Materials and methods

Mouse strains and animal husbandry

G6pc−/− strain mice have been previously described [8]. Transplant donors were G6pc+/+ mice, transgenic ROSA-26 mice [21], or transgenic GFP mice ((C57Bl/6-Tg(ACTB-EGFP)1 Osb/J mice (GFP-Tg)) [22]. Gepc−/− mice were routinely genotyped by PCR analysis using oligonucleotides to determine the presence of the wt allele (PCR1: 5′-AAGTCCOCTGGCCATGCCATGGG-3′ and 5′-CCAAGCATCCTGTGATGCTAACTC-3′, amplifying a fragment of 264 bp spanning across exon 3) and the mutant allele (PCR2: 5′-ATACCTTGATCCGGCTACCTGCC-3′ and 5′-CATTTGCACTGCCGGTAGAACTCC-3′ amplifying a fragment of 667 bp spanning across the neomycin gene). All animal studies were approved by the Internal Ethical Animal Experimentation Committee and carried out at the Animal Facility of the National Institute for Cancer Research (Genova, Italy).

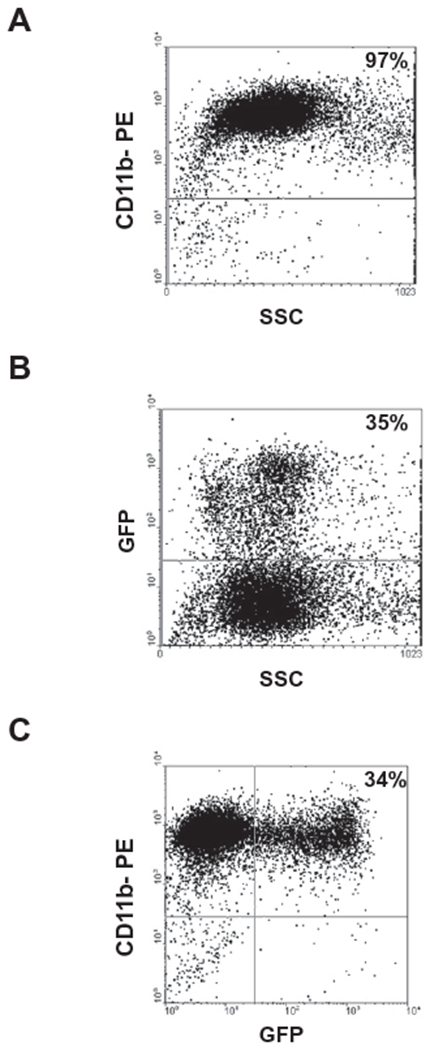

Preparation of bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells

Donor mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation, the fur saturated with 70% alcohol, and the animal moved into a sterile, laminar flow hood. Bone marrow cells were harvested from both femora and tibias by flushing contents into a collection tube using a 27-gauge needle and PBS. Bone marrow mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll Histopaque gradient centrifugation. Myelomonocytic cells were purified by incubation with CD11b MicroBeads (MACS Miltenyi Biotec, Milano, Italy), as described by the manufacturer. Purity of cell suspension was assessed by flow cytometry (Fig. 1A) after labeling cells with a PE conjugated anti-CD11b (MAC 1) antibody (BD, Milano, Italy). Purity of BMMs derived from the bone marrow of GFP-Tg transgenic mice was assessed by FACS analysis for two-color staining of CD11b+ and GFP+. Only bright cells were considered positive. The representative experiment shown in Fig. 1 shows that about 35% of purified CD11b cells were GFP positive (Fig 1B and C). The range of positivity among four independent determinations was 22–50%. Green fluorescence (FL1-H channel) was detected in logarithmic amplification (four decade log scale). CellQuest software (BD, Milano, Italy) was utilized for both data acquisition and post-acquisition analysis. BMMs were resuspended at a final concentration of 5 × 105 cells/μl and injected into the temporal vein (t.v.) of newborn G6pc−/− mice or into the median liver lobe of 5-day-old mice. For prenatal treatments, heterozygous G6pc+/− mice were bred and single 14/15-day-old fetuses were injected with 105 cells/5 μl. Intrauterine injections were performed through a ventral laparatomy and exposure of the uterine horns, as previously described [23]. After surgery, females were allowed to deliver normally.

Fig. 1. Isolation and CD11b expression of mouse bone marrow cells.

Myelomonocytic cells were purified from murine bone marrow cells by incubation with CD11 b (MAC-1) MicroBeads (as described in Materials and methods). (A) Purity of cell suspension was assessed by flow cytometric analysis after labeling cells for an individual staining with a PE-conjugated antibody against CD11b. (B) Myelomonocytic cells were purified from the bone marrow of GFP-Tg mice and purity of cell suspension was assessed by flow cytometric analysis for GFP+ expression. (C) Dot plot for two-color staining of CD11b+ and GFP+ is shown.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH)

Histological mouse liver sections (10 μm) were deparaffinized with three xylene washings, rehydrated in a graded ethanol series, and placed in double-distilled water. After digestion with 0.45 mg/ml Collagenase II (Invitrogen Life Science, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 20 min, the specimens were dehydrated in alcohol. Whole mouse chromosome paint probes specific for X and Y, labeled with Cyanine3 (Cy3) and fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC), respectively, (Cambio STAR-FISH, Cambridge, UK), were denatured at 65 °C for 10min and applied to the sections according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were hybridized for 16 h at 37 °C in a humidified chamber. Post-hybridization washes included preheated 2× SSC buffer and 0.1× SSC buffer for 5min each at 45 °C. The sections were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). For HNF1 detection, mouse liver sections were treated as described above. Following detection of the X chromosome, sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody rabbit polyclonal anti-HNF1 (1:10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Slides were washed three times with PBS and incubated with secondary antibody anti-rabbit Alexa 488 (Invitrogen Life Science, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E1000 epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Histology and immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in 4% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 5 μm sections. Tissue sections were then deparaffinized, rehydrated, and either stained with hematoxylin/eosin or specific antibodies. Endogenous peroxidases were blocked with 10 min incubation in 3% H2O2 in water, while antigen retrieval was obtained by boiling the slides for 15 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.5). After blocking non-specific sites with 10% normal goat serum for 40 min at RT, tissue sections were incubated 1 h with the appropriate primary antibody. After a 30 min reaction with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Bio-SPA, Milano, Italy), slides were washed with TBS (0.05 M Tris pH 7.6; 0.15 M NaCl; 0.05% Tween 20) and incubated for 10 min with strep-tavidin conjugated with HRP or AP (Bio-SPA, Milano, Italy). The reaction was then revealed with DAB (Bio-Optica, Milano, Italy) or NBT-BCIP, respectively (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). For double staining, the first antibody reaction was developed with NBT/BCIP, while the second was revealed with DAB.

The following primary antibodies were used: purified rabbit anti-GFP (1:800, RDI, Flanders, NJ, USA); rabbit polyclonal anti-β-galactosidase (1:750, Abcam, Cambridge, UK); rabbit anti-mouse albumin (1:200, AbDSerotec, Kidlington, UK). Slides were mounted with Eukitt (Bio-Optica, Milano, Italy) and observed with an Olympus BX51 microscope. Images were captured with a Camedia Olympus Photocamera.

Phenotype analysis

For G6Pase histochemical assay, cryostat sections were incubated for 10 min at room temperature in 40 mM Tris–maleate buffer, pH 6.5, 300 mM sucrose, 10 mM glucose-6-P, 3.6 mM Pb(NP3)2. Sections were rinsed in 300 mM aqueous sucrose solution for 1 min, lead sulfide was developed in a 1:100 diluted aqueous solution of 27% ammonium sulfide solution for 1 min and then rinsed in 300 mM aqueous sucrose solution for 1 min. Microsomes were prepared from frozen portions of livers collected from wt or treated and untreated G6Pase−/− mice, as previously described [17,24]. For the phosphohydrolase assay, appropriate amounts of microsomal proteins were incubated at 30 °C for 10min in a reaction mixture (100 μl) containing 50 mM sodium cacodylate buffer, pH 6.5, 10 mM G6P, and 2 mM EDTA. Sample absorbance was determined at 280 nm and was related to the amount of phosphate released using a standard curve constructed with a stock of inorganic phosphate solution. Mouse blood samples were collected by tail tip bleeding. Alternatively, mice were anesthetized and blood was drawn from the left ventricle with a syringe. Urine was collected at the time of necropsy with a 1 ml syringe by puncturing the bladder. Glucose levels were analyzed with Accu-chek Aviva (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). Serum triglycerides and cholesterol levels were analyzed using Kits purchased from Thermo Electron (Victoria, Australia). Serum alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels were determined using IDTox ALT Enzyme Assay Kit and IDTox AST Enzyme Assay Kit IdLABS Biotechnologies (London, ON, Canada). Urine albumin levels were analyzed using a Kit obtained from Bethyl Laboratories (Montgomery, TX, USA). Serum creatinine levels were determined with a Kit purchased from Assay Designs (Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Histochemical detection of β-galactosidase activity

Twenty micron-thick liver frozen sections were fixed in 2.5% gluteraldehyde Grade I (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Luis, MO, USA) in PBS for 5 min in ice, rinsed with PBS and incubated for 48h at 37 °c in PBS containing 5 mM K4[Fe(CN)6], 5 mM K3[Fe(CN)6], 2 mM MgCl2, 0.01% Triton, 1.5 mg/ml X-gal (5-Brom-4-Cloro-3-Indolyl β-d-galactopyranoside) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Luis, MO, USA). Slides were rinsed with H2O, counterstained with nuclear fast red, dried, mounted, and observed with an Olympus BX51 microscope. Six randomly collected sections were examined for each animal with a Leica DM LB2 microscope equipped with a 40× objective. Images were captured with a Leica DFC320 camera and transferred to an Apple eMac computer. The cell counter plugin of ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) was used to calculate the percentage of β-galactosidase-positive cells as a function of the total cell number in the microscopic fields.

Results

We performed BMMs transplantation in 48–72 h old G6pc−/− mice to determine whether hematopoietic stem cells can reconstitute liver functions. Bone marrow cells were obtained from femora and tibias of 8- to 9-week-old congenic wt male and newborn G6pc−/− mice were used as recipients. Bone marrow-derived CD11b+(MAC-1) cells were purified by incubation with CD11b MicroBeads. Purified cells were injected into the temporal vein (t.v.) of newborn G6pc−/− mice. Control G6pc−/− mice were injected with saline solution. G6pc+/+ control and G6pc−/− treated mice were sacrificed at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks of age. Untreated G6pc−/− mice were not analyzed at 4 weeks of age since 80% of them died within 10 days after birth and only 5% survived until 3 weeks of age. Tissues were paraffin-embedded and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for histological examination, or frozen for histochemical and phosphohydrolase assays. Blood and urine were collected for analysis of other liver functional parameters.

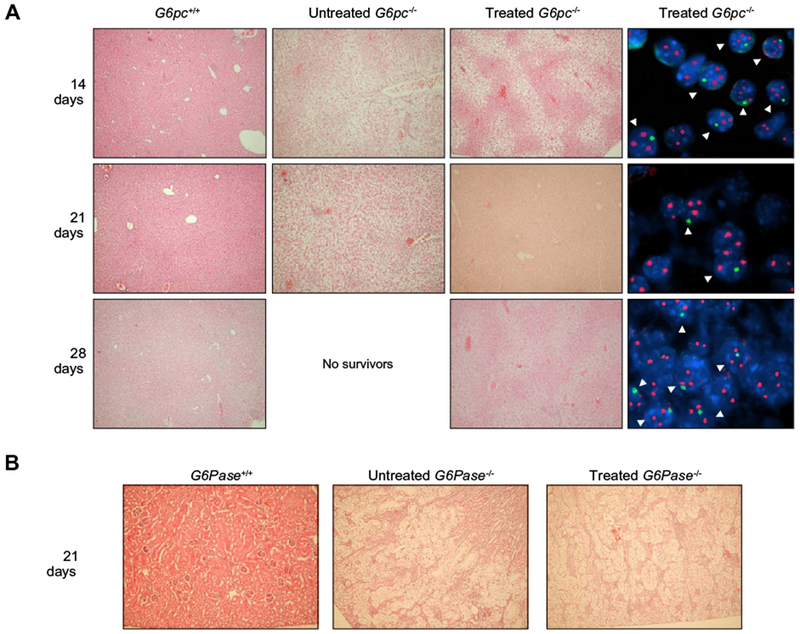

Fig. 2A shows the histological appearance of livers from wt and untreated or treated G6pc−/− mice at different times after birth. G6pc−/− mice had marked glycogen deposits in the hepatocytes. The glycogen storage in the cells destroys the normal architecture of the liver with enlargement of sinusoids. On the other hand, glycogen storage in the liver was considerably decreased after BMM infusion. Histological sections of livers of G6pc−/− treated mice revealed large areas of regenerating tissue consisting of hepatocytes of normal appearance and partial recovery of normal architecture.

Fig. 2. Histological analyses of tissues from G6pc−/− mice after BMM transplantation.

(A) G6pc−/− mice were transplanted with CD11b cells selected from the bone marrow of congenic G6pc+/+ mice. At 14 (n = 8), 21 (n = 10), and 28 (n = 7) days after treatment, mice were sacrificed and the livers processed. Control G6pc+/+ mice were sacrificed at 14 (n = 2), 21 (n = 2), and 28 (n = 2) days. Untreated G6pc−/− mice were sacrificed at 14 (n = 2) and 21 (n = 2). A very limited number of G6pc−/− could be analyzed since only 5% survived beyond 2 weeks of age and, due to their short lifespan, livers could not be collected beyond 3 weeks of age. Hematoxylin/eosin staining of livers of G6pc+/+ or untreated G6pc−/− mice is shown in the two left panels (20× magnification). Serial sections of livers from treated G6pc−/− mice were stained with hematoxylin/eosin (20× magnification) or analyzed with fluorescent in situ hybridization for detection of X and Y chromosome-positive nuclei (100× magnification). Representative results are shown for each time point in the two right panels. X chromosome signals are red and Y chromosome signals are green. (B) Hematoxylin- and eosin-stained kidneys from age-matched G6pc+/+ (n = 2), untreated G6pc−/− (n = 2), and BMM-treated G6pc−/− (n = 4) mice are shown. In the untreated G6pc−/− and BMM-treated G6pc−/− mice, the renal tubular epithelial cells are markedly enlarged by glycogen deposition, resulting in the compression of glomeruli. Glycogen deposits in renal epithelial cells are seen as clear areas. 40× magnification.

Cell fusion is one of the mechanisms by which committed myelomonocytic cells give rise to hepatocytes [4–6]. Serial sections corresponding to areas of regenerating livers of treated mice were deparaffinized and FISH with X and Y chromosome paints was performed to determine whether the normal appearing hepatocytes in treated G6pc−/− mice were derived by fusion between myelomonocytic cells and host hepatocytes. Sections were counterstained with DAPI mounting medium. Male mice were used as donors of BMMs. Therefore, if cell fusion occurred, female recipients should show hepatocytes with nuclei containing three X chromosomes and one Y chromosome. Between 20% and 40% of female hepatocytes/liver section examined also contained a Y chromosome, indicating that cell fusion had taken place (Fig. 2A). The areas of regenerating tissue appeared more extensive as the mice grew older, suggesting fused cell proliferation. However, the possibility that newly fused BMMs contribute to this pattern cannot be ruled out.

No improvement was observed in the kidneys of treated mice (Fig. 2B). In control and treated G6pc−/− mice, heavy glycogen accumulation is evident in tubular epithelial cells with compression of glomeruli, affecting the normal architecture of the kidney with enlargement of tubules, indicating that BMM transplant does not correct kidney dysfunctions.

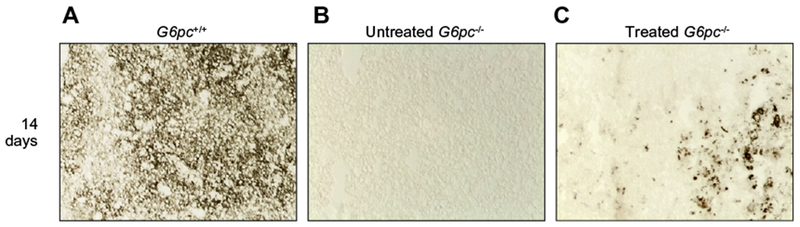

To assess whether there was restoration of G6Pase activity, we performed histochemical detection of G6Pase in liver tissues of treated animals. Activity of G6Pase was detectable throughout the areas of liver regeneration in treated mice, in contrast to the untreated G6pc−/− mouse liver for which staining was negative (Fig. 3). These results indicate that functional G6Pase is present in liver areas where regeneration is detected.

Fig. 3. Qualitative histochemical analysis of G6Pase activity.

To evaluate the G6Pase activity, liver cryostat sections were treated as described in Material and methods. Colored lead sulfide was developed with ammonium sulfide. Representative results are shown. Liver sections were from (A) G6pc+/+, (B) untreated G6pc−/− and (C) treated G6pc−/− mice.

We analyzed liver tissues of treated animals for G6Pase activity by performing a phosphohydrolase assay. Microsomes were prepared from frozen portions of livers collected from wt and treated or untreated G6Pase−/− mice. As shown in Table 1, Glu-6-P phosphohydrolase activity in the liver of treated animals reached 8.6% of the activity in the livers of G6Pase+/+ mice at day 21 post-injection.

Table 1.

Hepatic G6Pase activity, plasma glucose, cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT, AST, creatinine, and urine albumin levels in G6Pase−/− mice after BMM transplantation.

| Untreated |

Treated |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 days | 14 days | 7 days | 14 days | 21 days | |

| G6Pasea | 1.5 ± 0.2 (4) | 2.1 ± 0.1 (4) | 4.6 ± 2.1 (4) | 10.2 ± 2.4 (4) | 14.4 ± 3.3 (4) |

| Glucoseb | 16 ± 2 (4) | 14 ± 2 (4) | 40 ± 2 (6) | 58 ± 2 (6) | 75 ± 4 (6) |

| Cholesterolc | 289 ± 16 (4) | 320 ± 20 (4) | 200 ± 4 (6) | 163 ± 9 (6) | 166 ± 10 (6) |

| Triglyceridesd | 355 ± 37 (4) | 453 ± 42 (4) | 293 ± 25 (6) | 230 ± 20 (6) | 192 ± 8 (6) |

| ALTe | 68 ± 11 (4) | 96.5 ± 28 (4) | 79 ± 3 (4) | 62 ± 3 (4) | 53 ± 4 (4) |

| ASTf | 625 ± 36 (4) | 591 ± 42 (4) | 505 ± 47 (4) | 469 ± 25 (4) | 315 ± 32 (4) |

| Albuming | 1.53 ± 0.08 (4) | 1.34 ± 0.09 (4) | 1.55 ± 0.06 (4) | 1.69 ± 0.08 (4) | 1.59 ± 0.04 (4) |

| Creatinineh | 1.0 ± 0.09 (4) | 1.18 ± 0.07 (4) | 0.93 ± 0.1 (4) | 1.2 ± 0.09 (4) | 1.0 ± 0.08 (4) |

Metabolic functions were analyzed in treated and untreated G6pc−/− mice. The number of mice analyzed is indicated in parenthesis. Each value represents the mean of the indicated number of animals ± SD.

Normal values were 168 ± 8 nmol/min/mg protein and were determined in 4 wt mice.

Normal values were 120 ± 10 mg/dl and were determined in 8 wt mice.

Normal values were 126 ± 8 mg/dl and were determined in 8 wt mice.

Normal values were 72 ± 5 mg/dl and were determined in 8 wt mice.

Normal values were 27.5 ± 3.5 U/L and were determined in 4 wt mice.

Normal values were 56 ± 8 U/L and were determined in 4 wt mice.

Normal values were 0.13 ± 0.01 mg/ml and were determined in 4 wt mice.

Normal values were 0.223 ± 0.01 mg/ml and were determined in 4 wt mice.

We further assessed the recovery of liver functions in treated mice by evaluating the plasma glucose levels and other metabolism indicators. As a result of a lack of the G6Pase enzyme, blood lipids in knockout mice are high. Therefore, we determined serum cholesterol and triglycerides. Finally, we measured ALT and AST serum levels. As shown in Table 1, improvement of glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, ALT, and AST levels was detectable in treated animals. Plasma glucose levels reached 63% of the normal level by 3 weeks of age, concomitant with further improvement of the other liver functional parameters (Table 1). Thus, as a consequence of liver repopulation by normal BMMs, treated animals showed some correction of liver dysfunctions. On the other hand, serum creatinine levels remained high indicating that BMM transplant did not correct kidney damage. This is further indicated by the high levels of albumin in the urine of treated mice, since the renal dysfunction in GSD1a causes glomerular hyperfiltration and proteinuria [18].

Experiments were performed to explore whether other routes of injection could be effective in inducing liver reconstitution. G6pc−/− mice (n = 4) were injected with BMMs directly into the liver (i.h.) at 5 days of age. A comparison between the injected median lobe (Fig. 4B and E) and the untreated adjacent lobe (Fig. 4A and D) of the livers of two treated mice is shown. Normal looking hepatocytes are present in the treated lobe and completely absent in the untreated one. Moreover, cell fusion could be detected in liver sections from the treated lobes (Fig. 4C and F). We also performed injection of BMMs in uterus at 14/15 days of gestation (n = 3). Large histological normal liver areas were present in treated 3-week-old G6pc−/− mice (Fig. 4G and H). Fusion between hepatocytes and BMMs could be detected (Fig. 4I). While injection into the temporal vein leads to a homogeneous distribution of donor cells throughout the liver tissue, intrauterine or intrahepatic injection leads to colonization of BMMs mainly at the site of injection. This is documented by the images shown in Fig. 4, demonstrating that only the lobe that received the BMMs shows presence of normal hepatocytes and strong reduction of glycogen accumulation.

Fig. 4. Injection of BMMs into livers of newborn and prenatal G6pc−/− mice.

Five-day-old G6pc−/− mice (n = 4) were treated by BMM injection directly into the liver median lobe (i.h.). Representative results obtained with livers of two treated mice are shown. Liver reconstitution can be appreciated in the treated liver median lobe (B and E) in comparison with an adjacent untreated lobe (A and D). In the treated areas, cell fusion can be detected (C and F), (arrowheads). Alternatively, BMMs were injected into the livers of 14/15-day-old fetuses (i.u.). Three pregnant females were utilized for intrauterine injections. Three G6pc−/− mice were born alive and analyzed at 3 weeks of age. (G and H) Hematoxylin/eosin staining of liver sections of two treated G6pc−/− mice are shown. Histologically normal liver areas are evident in animals injected at 15 days of gestation, where cell fusion can be visualized (I). (C, F, and I) 100× magnification.

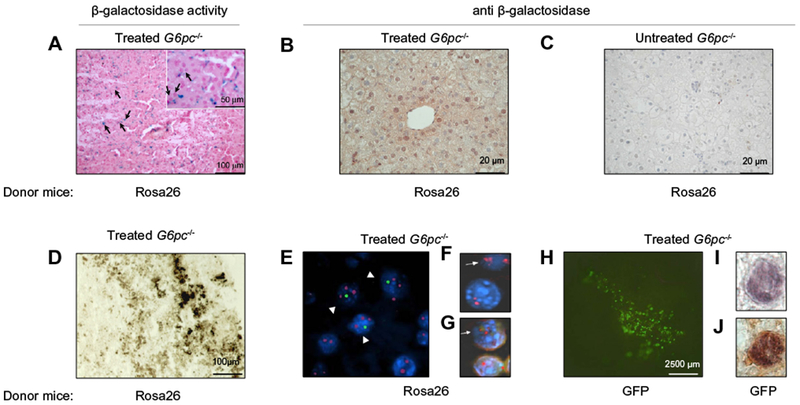

In an attempt to quantify the hepatic engraftment, newborn G6pc−/− mice were injected into the temporal vein with BMMs from Rosa26 or GFP-Tg transgenic mice, expressing in all tissues the LacZ or the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene, respectively, [21,22]. Animals were sacrificed after 2 weeks and analyzed for β-galactosidase (β-gal) activity or GFP expression. We analyzed liver serial sections of two G6pc−/− mice treated with Rosa 26-derived BMMs for the presence of β-gal-positive cells using histochemical staining. We observed the presence of β-gal-positive normal looking hepatocytes (Fig. 5A, black arrows) as well as other β-gal positive cells with different morphology that may be donor BMMs that have not fused with the host hepatocytes. The presence of β-gal positive, normal looking hepatocytes was confirmed by immunohistochemical detection of the enzyme (Fig. 5B) or by G6Pase activity in liver sections from the same treated mouse (Fig. 5D). FISH analysis with X and Y chromosome paints was performed and one of these livers is shown in Fig. 5E. Fusion between female hepatocytes and male donor cells (XXXY) is indicated by arrowheads. Immunofluorescence analysis of tissue sections with anti-HNF1, a hepatocyte marker [25], showed nuclear positivity of fused cells (Fig. 5F and G, arrows) demonstrating that these cells are functional hepatocytes.

Fig. 5. Liver repopulation by Rosa 26- and GFP-Tg-derived BMMs.

G6pc−/− mice were injected into the temporal vein with BMMs derived from Rosa26 mice (n = 7) (A–G) or with BMMs derived from GFP-transgenic mice (n = 10) (H–J). A) Normal looking hepatocytes (black arrows) are visible after staining for β-galactosidase (visualized by the blue precipitate of X-gal) or (B) after immunostaining with anti-β-galactosidase antibody at 2 weeks after treatment. (C) A liver section from an untreated G6pc−/− mouse immunostained with anti-β-galactosidase antibody. (D) Histochemical analysis of G6Pase activity in a liver section from a mouse infused with BMMs derived from Rosa26 and (E) FISH analysis for X and Y chromosome detection in a liver section from the same animal. Presence of fused cells is indicated by arrowheads. (F) A liver section from a G6pc−/− mouse treated with BMMs derived from Rosa26 mice was analyzed by fluorescent in situ hybridization for detection of the X chromosome. A fused cell showing three X chromosomes is indicated by an arrow. (G) The same section was analyzed by immunofluorescence with an antibody anti-HNF1. A fused cell showing positivity for HNF1 is indicated by an arrow. (H) Whole mount of a liver from a 2-week-old G6pc−/− mouse with GFP-derived BMMs showing presence of fluorescent cells. (I) GFP-positive hepatocytes stained with anti-GFP and (J) double-stained with anti-albumin. (E, F, G, I, and J) 100× magnification.

β-Gal-positive, normal looking hepatocytes were counted in the areas of the liver where regeneration could be observed. Six randomly collected sections obtained from two animals treated with Rosa26-derived BMMs were analyzed. The percentage of β-gal-positive cells was calculated as a function of the total number of cells in the microscopic fields visualized by nuclear red. About 15% of the hepatocytes present in the liver sections analyzed from one mouse and 9% from the other animal stained positive for β-gal.

Similar experiments were performed using BMMs obtained from GFP-Tg mice (Fig. 5H). Engraftments of livers by GFP-positive normally appearing epithelial cells were detected in sections of livers from treated animals. Double immunohistochemistry with anti-GFP and anti-albumin antibodies demonstrated the hepatocytes nature of GFP-positive cells (Fig. 5I and J). To evaluate the frequency of repopulating BMMs in the whole treated livers, we analyzed liver serial sections of G6pc−/− mice treated with GFP-Tg-derived BMMs by double immunohistochemistry with anti-GFP and anti-albumin antibodies. Twenty randomly collected sections from livers of three G6pc−/− treated mice and five fields/section were analyzed for a total of 2.5 × 104 cells per mouse (Table 2). The percentage of GFP-positive cells was calculated as a function of the total number of cells in the microscopic field visualized by hematoxylin. We found that an average of 0.28% of liver cells stained positive for GFP. In these experiments, we engrafted BMMs from C57Bl mice into 129SvJ mice. Data obtained at 2 weeks after such an allogeneic transplantation are superimposable with data obtained under syngeneic conditions in terms of presence of normal looking hepatocytes, cell fusion and G6Pase activity. Hence, there appears to be little allograft rejection consistent with the notion that a minimal immune reactivity is expected from such young animals. Moreover, we engrafted BMMs across minor histocompatibility barriers, further limiting rejection. Therefore, less than one percent of the liver cell population is constituted by BMM-derived hepatocytes.

Table 2.

Quantification of GFP positive cells after BMMs transplantation.

| Mouse identification numbera | Days after injection | Average number of GFP+ cells/fieldb | % donor cellsc | Total GFP+ cellsd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 13 | 0.9 | 0.23 | 2.4×104 |

| 2 | 16 | 0.8 | 0.32 | 1.6×105 |

| 3 | 17 | 0.71 | 0.29 | 1.4×105 |

CD11+ bone marrow cells derived from GFP-Tg mice were injected into the temporal vein ot 2-day-old G6Pase−/− mice.

Liver specimens were analyzed by immunohistochemistry for GFP. At least 20 randomly collected nonsequential sections from livers of three different G6Pase−/− treated mice were analyzed. Cell count was performed on at least five fields/section for a total of 100 fields/animal.

The percentage of GFP-positive cells was calculated as a function of the total number of cells in the microscopic field visualized using a 40× objective. The average number of hepatocytes/field was 253.7 ± 68 and was calculated by analyzing three fields of 6 different G6Pase−/− liver samples stained with hematoxylin/eosin.

The total number of GFP-positive cells in the liver of mice was determined by assuming as 1.3 × 107 to 5.0 × 107 the total number of liver cells in a 13- to 17-day-old mouse, respectively [14].

Discussion

We evaluated BMM ability to regenerate the liver of diseased animals. We demonstrate that injection of BMMs into newborn G6pc−/− mice ameliorated liver functions, as indicated by improved liver functional parameters. In newborn mice, where the liver is still proliferating, the grafted BMM caused an early repopulation, inducing regeneration of areas of liver tissue showing a reduced glycogen deposition, normal morphology of hepatocytes, partial recovery of tissue architecture, and G6Pase activity. Unfortunately, BMM treatment did not correct kidney damage and treated mice showed very high levels of serum creatinine and urine albumin, similar to untreated G6pc−/− mice.

Recent works have demonstrated that adult HSCs are capable of repopulating the liver by fusing with host hepatocytes [4–6]. However, fully functional hepatocytes emerge in the adult mouse liver with a quite low frequency and a delayed kinetic. Hepatocytes are first detected 7 weeks after lethal irradiation and bone marrow transplantation and single cells evolved into hepatocytes nodules 11 weeks after transplantation [4,5,26]. It was later demonstrated that myelomonocytic cells are the population of bone marrow cells that produce functional hepatocytes by in vivo fusion [6].

It was interesting to evaluate whether treatment in newborn animals would improve the repopulation efficiencies of transplanted BMMs. Here, we demonstrate that, when the transplant is performed in very young animals, the efficiency of engraftment significantly improves relative to that of adult mice.

Untreated G6Pase−/− mice die shortly after birth unless glucose is administered twice a day [8]. The animals in the present study did not receive any treatment to relieve the severe hypoglycemia in order to single out the effects of BMM treatment on the mouse response. Under these conditions, G6pc−/− mice treated with BMMs survive until 4–5 weeks of age, indicating that cell fusion occurs rather rapidly even though the efficiency of repopulation of the liver by BMMs (<1%), combined with the very severe phenotype displayed by these mice, is not sufficient to cause a total cure of the disease. Biochemical measurement of hepatic enzymatic activity at 3 weeks of age shows restoration of approximately 8.6% of the normal hepatic G6Pase activity. We conclude that the liver activity of G6Pase in these mice is sufficient to prolong life but not to sustain it much beyond 4 weeks of age.

Cellular therapy with stem cells and their progeny is a promising new approach capable of addressing mostly unmet medical needs and may represent an attractive alternative therapeutic approach to treat liver diseases such as acute liver failure and some metabolic disorders, for which successful outcomes have been achieved [1,27–30].

The majority of the preclinical gene transfer work focused on the adult organism. However, evidence exists that gene therapy can be applied to newborns and this application is particularly important in treating metabolic disorders before the organ degeneration associated with the progression of the disease occurs. For example, the therapeutic effect of retroviral vectors in neonatal gene therapy was evaluated in a canine model of mucopolysaccharidosis VII [12,13]. Newborn treatment was further reported to be effective both in the liver and in the nervous system [10,12,14]. Treatment of newborn mice with an adenovirus 5-derived vector corrected the metabolic abnormalities caused by GSD-1a [8,11]. The therapeutic effects were transient but could be prolonged by the combined treatment with AAV vectors [9]. We have previously shown that newborn are particularly susceptible to lentiviral-mediated, liver targeted, gene transfer, demonstrating a much greater efficiency of liver transduction by HIV-2 in newborn mice in comparison with adult recipients [16]. Therefore, these studies indicate that early intervention may be a strategy for efficiently targeting the liver for gene therapy applications.

Previous works on GSD1a therapy in this experimental mouse model have shown that viral vectors can deliver the G6pc gene into the G6pc−/− mouse, restore kidney and/or liver functions and improve the survival of mice to various degrees [8,9,11,15,31,32]. In particular, combined treatment with adeno virus and adeno-associated virus or treatment with recombinant adeno-associated virus-1 [9,11] was particularly effective in extending the life span of mice, demonstrating the efficiency of viral transfer in correcting the genetic defect of the G6pc−/− mice. The present data demonstrate that BMMs are a valid source of cells to target the damaged liver and can have a widespread application because they can regenerate liver tissue damaged by a variety of pathogens. The translation of the murine model to the clinical situation is rather complex and many variables come into play. Before the preclinical model could be applicable to humans, more studies will be necessary such as the evaluation of long term stability of injected cells and the possibility to manipulate BMMs for autologous transplantation. Moreover, the BMM treatment should be combined with therapeutic approaches to ameliorate the patient’s conditions and to compensate for renal defects. It is likely that the availability of multiple therapeutic approaches, based on different technologies, will be the key to tailor a treatment for individual patients. Moreover, any possible application to humans will probably have to be integrated in a complex clinical approach comprising pharmacological/dietary treatments or even a combination of different gene transfer approaches.

Studies using autologous bone marrow cell infusion in patients with cirrhosis provide hope that BM-derived cells may be a valuable resource for cell-based therapies for liver disease. However, the results must be interpreted with some caution, given the limited number of patients enrolled in each trial and limited controls [1]. Other cell types have been investigated for their ability to repair the liver. Hepatocyte transplantation has shown potential for certain liver diseases but one of the main obstacles to the clinical application of hepatocyte transplantation is the limited source, and often low quality, of cells from donor livers. Another source is liver stem cells. However, this population is low in number accounting only for 0.3–0.7% of the liver mass [33]. Bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem cells are available and easy to isolate since they can be obtained from living individuals using a moderately invasive procedure. Therefore, BMMs may have considerable advantages over the use of hepatocytes or their precursors.

Liver engraftment occurs when BMHs have a proliferative advantage. In this respect, normal cells should have a strong selective growth advantage in a diseased liver environment because of their normal metabolic status and ability to fully respond to proliferative program. Moreover, newborn and prenatal hepatocytes are endowed with proliferative activity, which may be an important factor in increasing the efficiency of the treatment. In fact, our study indicates that BMM transplant may be significantly effective in reconstituting highly degenerated livers in newborn and prenatal animals.

Acknowledgements

We thank Paolo Fardin for helpful discussions, Paolo Mele for help with images, Federica Sabatini for help with FACS analysis, and Sara Barzaghi for secretarial assistance. The support and encouragement of the Associazione Italiana Glicogenosi was instrumental and essential for the execution of the present work.

Financial support

This work was supported by grants from Associazione Italiana Glicogenosi and from the Italian Ministry of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors who have taken part in this study declared that they do not have anything to disclose regarding funding or conflict of interest with respect to this manuscript.

References

- [1].Almeida-Porada G, Zanjani ED, Porada CD. Bone marrow stem cells and liver regeneration. Exp Hematol 2010;38:574–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Gilchrist ES, Plevris JN. Bone marrow-derived stem cells in liver repair: 10 years down the line. Liver Transplant 2010;16:118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Lagasse E, Connors H, Al Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, et al. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med 2000;6:1229–1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Vassilopoulos G, Wang PR, Russell DW. Transplanted bone marrow regenerates liver by cell fusion. Nature 2003;422:901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wang X, Willenbring H, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Foster M, Al Dhalimy M, et al. Cell fusion is the principal source of bone-marrow-derived hepatocytes. Nature 2003;422:897–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Willenbring H, Bailey AS, Foster M, Akkari Y, Dorrell C, Olson S, et al. Myelomonocytic cells are sufficient for therapeutic cell fusion in liver. Nat Med 2004;10:744–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Wang X, Montini E, Al Dhalimy M, Lagasse E, Finegold M, Grompe M. Kinetics of liver repopulation after bone marrow transplantation. Am J Pathol 2002;161:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Zingone A, Hiraiwa H, Pan CJ, Lin B, Chen H, Ward JM, et al. Correction of glycogen storage disease type 1a in a mouse model by gene therapy. J Biol Chem 2000;275:828–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ghosh A, Allamarvdasht M, Pan CJ, Sun MS, Mansfield BC, Byrne BJ, et al. Long-term correction of murine glycogen storage disease type Ia by recombinant adeno-associated virus-1-mediated gene transfer. Gene Ther 2006;13:321–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Capotondo A, Cesani M, Pepe S, Fasano S, Gregori S, Tononi L, et al. Safety of arylsulfatase A overexpression for gene therapy of metachromatic leukodystrophy. Hum Gene Ther 2007;18:821–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sun MS, Pan CJ, Shieh JJ, Ghosh A, Chen LY, Mansfield BC, et al. Sustained hepatic and renal glucose-6-phosphatase expression corrects glycogen storage disease type Ia in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2002;11:2155–2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ponder KP, Melniczek JR, Xu L, Weil MA, O’Malley TM, O’Donnell PA, et al. Therapeutic neonatal hepatic gene therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis VII dogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:13102–13107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Xu L, Haskins ME, Melniczek JR, Gao C, Weil MA, O’Malley TM, et al. Transduction of hepatocytes after neonatal delivery of a Moloney murine leukemia virus based retroviral vector results in long-term expression of beta-glucuronidase in mucopolysaccharidosis VII dogs. Mol Ther 2002;5:141–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Park F, Ohashi K, Kay MA. The effect of age on hepatic gene transfer with self-inactivating lentiviral vectors in vivo. Mol Ther 2003;8:314–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Grinshpun A, Condiotti R, Waddington SN, Peer M, Zeig E, Peretz S, et al. Neonatal gene therapy of glycogen storage disease type Ia using a feline immunodeficiency virus-based vector. Mol Ther 2010;18:1592–1598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Salani B, Damonte P, Zingone A, Barbieri O, Chou JY, D’Costa J, et al. Newborn liver gene transfer by an HIV-2-based lentiviral vector. Gene Ther 2005;12:803–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Lei KJ, Chen H, Pan CJ, Ward JM, Mosinger B Jr, Lee EJ, et al. Glucose-6-phosphatase dependent substrate transport in the glycogen storage disease type-1a mouse. Nat Genet 1996;13:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Chou JY, Jun HS, Mansfield BC. Glycogen storage disease type I and G6Pase-beta deficiency: etiology and therapy. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2010;6:676–688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Arion WJ, Wallin BK, Lange AJ, Ballas LM. On the involvement of a glucose 6-phosphate transport system in the function of microsomal glucose 6-phosphatase. Mol Cell Biochem 1975;6:75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chen YT. Glycogen storage diseases In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, editors. The metabolic and molecular basis of inherited disease. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. p. 1521–1551. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Soriano P Generalized lacZ expression with the ROSA26 Cre reporter strain. Nat Genet 1999;21:70–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Okabe M, Ikawa M, Kominami K, Nakanishi T, Nishimune Y. ‘Green mice’ as a source of ubiquitous green cells. FEBS Lett 1997;407:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Barbieri O, Ognio E, Rossi O, Astigiano S, Rossi L. Embryotoxicity of benzo(a)pyrene and some of its synthetic derivatives in Swiss mice. Cancer Res 1986;46:94–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hiraiwa H, Pan CJ, Lin B, Moses SW, Chou JY. Inactivation of the glucose 6-phosphate transporter causes glycogen storage disease type 1b. J Biol Chem 1999;274:5532–5536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Swenson ES, Guest I, Ilic Z, Mazzeo-Helgevold M, Lizardi P, Hardiman C, et al. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-1 as marker of epithelial phenotype reveals marrow-derived hepatocytes, but not duct cells, after liver injury in mice. Stem Cells 2008;26:1768–1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alvarez-Dolado M, Pardal R, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Fike JR, Lee HO, Pfeffer K, et al. Fusion of bone-marrow-derived cells with Purkinje neurons, cardiomyocytes and hepatocytes. Nature 2003;425:968–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Haridass D, Narain N, Ott M. Hepatocyte transplantation: waiting for stem cells. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2008;13:627–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Flohr TR, Bonatti H Jr, Brayman KL, Pruett TL. The use of stem cells in liver disease. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 2009;14:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhao Q, Ren H, Zhu D, Han Z. Stem/progenitor cells in liver injury repair and regeneration. Biol Cell 2009;101:557–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dan YY, Yeoh GC. Liver stem cells: a scientific and clinical perspective. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Koeberl DD, Sun BD, Damodaran TV, Brown T, Millington DS, Benjamin DK Jr, et al. Early, sustained efficacy of adeno-associated virus vector-mediated gene therapy in glycogen storage disease type Ia. Gene ther 2006;13:1281–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Yiu WH, Lee YM, Peng WT, Pan CJ, Mead PA, Mansfield BC, et al. Complete normalization of hepatic G6PC deficiency in murine glycogen storage disease type Ia using gene therapy. Mol Ther 2010;18:1067–1084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dhawan A, Puppi J, Hughes RD, Mitry RR. Human hepatocyte transplantation: current experience and future challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;7:288–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]