Abstract

Yoga is an ancient mind body practice. Although yoga has been used as a complementary health approach for enhancing wellness and addressing a variety of health issues, little is known about the impact of yoga on cognitive functioning in adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. We conducted a literature review to examine the impact of yoga on persons with MCI and dementia. Eight studies were identified that reported on yoga as either the primary intervention or one component of a multi-component intervention in samples of persons with MCI or dementia. Results suggest that yoga may have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning, particularly on attention and verbal memory. Further, yoga may affect cognitive functioning through improved sleep, mood, and neural connectivity. There are a number of limitations of the existing studies, including a lack of intervention details, as well as variability in the frequency/duration and components of the yoga interventions. A further complicating issue is the role of various underlying etiologies of cognitive impairment. Despite these limitations, providers may consider recommending yoga to persons with MCI or dementia as a safe and potentially beneficial complementary health approach.

Keywords: yoga, mild cognitive impairment, dementia, mindfulness-based stress reduction, mind-body, aging

Introduction

Yoga is a mind body practice that originated in ancient India and is identified as a complementary health approach by the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health.1 Hatha yoga, the most common branch of yoga practiced in the US, emphasizes physical postures, and usually incorporates breathing and meditation. It includes some of the most well-known styles of yoga practiced in the U.S. (e.g., Anusara, Ashtanga, Bikram, Integral, Iyengar, Kripalu).2 In the US, the popularity of yoga is growing; the number of people practicing yoga doubled in a 10-year period.3 Almost 10% of the population practiced yoga within the last year.3

Yoga is used by many to promote general wellness and disease prevention.4,5 It is also increasingly used as an ancillary treatment for symptoms of various medical conditions, including depression,6 anxiety,7 low back pain,8 asthma,9 hypertension,10 musculoskeletal conditions,11 chronic obstructive pulmonary disease,12 cancer,13 and neurological disorders.14 Yoga has been demonstrated to reduce anxiety,15 depression,6 and pain;8 improve cardiovascular risk factors;16 and improve sleep.17 Along with benefits to mental and physical health, yoga also impacts cognitive functioning. A recent meta-analysis showed that yoga had a significant effect on multiple domains of cognitive functioning among healthy adults, including attention and processing speed, executive function, and memory.18 Hariprasad and colleagues19 conducted a randomized trial of yoga in 87 non-demented older adults living in senior housing. They found that 6 months of yoga (physical postures, breathing, and meditation) resulted in significant improvements in immediate and delayed verbal memory, delayed visual memory, attention, and processing speed.

Nonetheless, little is known about the impact of yoga on cognitive functioning in adults with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia. Further, the burden of cognitive impairment in society is an increasingly important issue. Current treatments focus on reducing associated symptoms, including cognitive impairment, behavioral disturbances, and mood disturbances. No pharmacological treatments have demonstrated convincing effects in delaying disease progression or conversion of MCI to dementia. Despite the demonstrated potential for yoga to have a positive impact on these symptoms, few studies have examined the impact of yoga on older adults with MCI or dementia. In this paper, we review the literature on the impact of yoga on people with MCI and dementia. We then discuss how yoga might impact cognitive functioning and offer future directions.

Methods

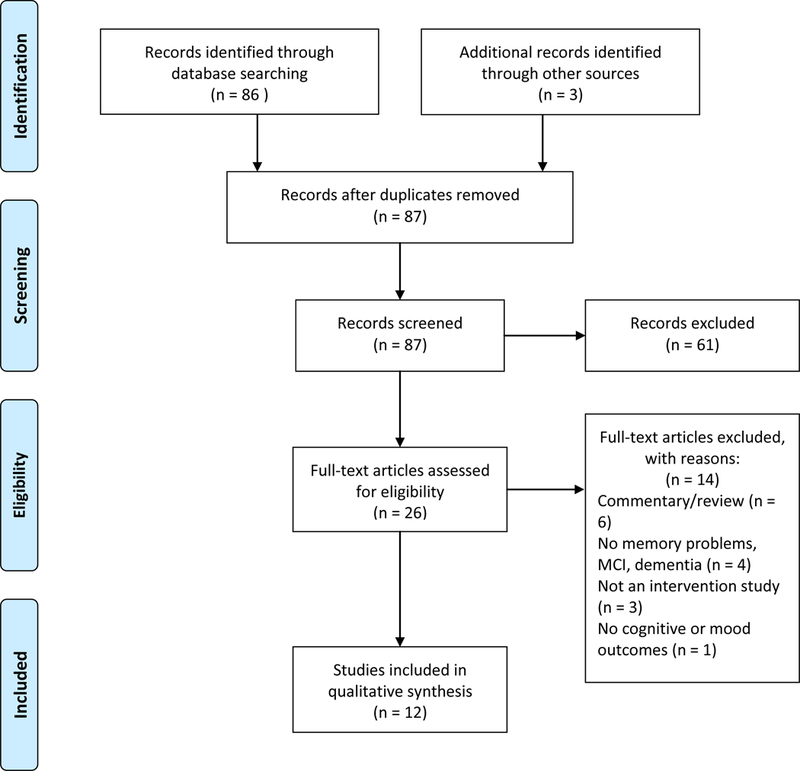

We performed a search of PubMed using the keywords “yoga AND mild cognitive impairment,” “yoga AND dementia,” and “yoga AND Alzheimer’s.” Further, because yoga is an important component of the commonly studied Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, we also searched by “mindfulness-based stress reduction AND mild cognitive impairment,” “mindfulness-based stress reduction AND dementia,” and “mindfulness-based stress reduction AND Alzheimer’s.” A total of 87 articles were identified. Articles were published between 2004 and 2018. Articles were included if they described a yoga intervention and included either cognitive or neuropsychiatric outcomes. Articles were excluded if they were research protocols, reviews, commentaries, included participants without cognitive impairment, or were not intervention studies. We identified 12 publications representing eight trials that described the results of a yoga intervention for individuals with self-reported cognitive impairment, MCI, Alzheimer’s disease (AD), or dementia. Five are quasi-experimental trials (i.e., pre-post studies and non-randomized controlled trials) and three are randomized controlled trials (RCTs). See Figure 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram

Results

Table 1 describes the study and intervention characteristics of three trials that used yoga as the primary intervention. Table 2 provides this information for five multi-component interventions that included yoga. Table 3 provides a summary of intervention outcomes.

Table 1.

Study and yoga intervention characteristics for yoga as the primary intervention.

| Eyre et al.26,46,53 | Fan & Chen20 | Litchke et al.21 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Type/comparison | RCT | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental |

| Sample Size | 81 | 68 | 19 |

| Participants | MCI | Mild to moderate AD patients in long-term care facility | Mild to severe AD |

| Comparison Group | Memory enhancement training | N/A | N/A |

| Yoga Program/Style | Kundalini yoga | Silver yoga/Hatha | LVCY chair yoga |

| Length of Class (in minutes) | 60 | 55 | 30–60 |

| Frequency | 1x/week | 3x/week | 2x/week |

| Duration (in weeks) | 12 | 12 | 10 |

| Home practice | 12 min daily (chanting only) | Not reported | Not reported |

| Adherence | 76.9% adherence to yoga; completed M = 7.13 sessions out of 8 | 90.9% adherence to yoga; 95.5% average attendance rate | 70.3% |

| Yoga Components | |||

| Postures | X | X | X |

| Breathing | X | X | X |

| Relaxation | X | X | X |

| Meditation / mental focus / visualization | X | X | |

| Chanting | X |

AD = Alzheimer’s Disease. CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating. LVCY = Lakshmi Voelker Chair Yoga. MCI = Mild Cognitive Impairment. N/A = not applicable

Table 2.

Study and yoga intervention characteristics for yoga one component of a multi-component intervention.

| Barnes et al.23,24 | Lenze et al.22,47 | Paller et al.25 | Wells et al.27,28 | Wetherell et al.29 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Type/comparison | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental | Quasi-experimental | RCT | RCT |

| Sample size | 12 | 34 | 17* | 14 | 103 |

| Participants | Cognitive impairment/dementia | Subjective cognitive dysfunction | AD, MCI, memory loss due to strokes, frontotemporal dementia, subjective cognitive dysfunction | MCI | Subjective cognitive dysfunction |

| Comparison group | Usual care | None | None | Usual care | Health education |

| Intervention | Integrated movement | MBSR | Mindfulness training | MBSR | MBSR |

| Length of session | 45m | 2.5 h | 1.5 h | 2 h | Not reported |

| # times/week | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| # of weeks | 18 | 8 or 12 + 1 retreat | 8 | 8 + one retreat | 8 + retreat |

| Home practice | 4 individual home sessions | Daily | 30–60 min daily | 30 min daily | Frequency not reported |

| Adherence | 72.2% | Not reported | Not reported | 98.75%; M = 7.9 sessions; 26 min home practice daily | 91.25%; M = 7.3 sessions |

| Intervention Components | Warm up to group, body awareness, chair-based exercises adapted from tai chi, yoga, and Feldenkrais | Mindfulness meditation, gentle yoga | Mindfulness, gentle yoga, loving-kindness practice, meditation | Sitting and walking meditation, body scan, yoga | Mindfulness meditation, gentle yoga |

MCI = mild cognitive impairment. MBSR = Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction. RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Only patient data is presented.

Table 3.

Outcomes of yoga interventions.

| Outcomes | Barnes et al.23,24 (N = 12) |

Eyre et al.26,46,53 (N = 81) |

Fan & Chen20 (N = 68) |

Lenze et al.22,47 (N = 34) |

Litchke et al.21 (N = 19) |

Paller et al.25* (N = 17) |

Wells et al.27,28 (N = 14) |

Wetherell et al.29 (N = 103) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive functioning | + | + | + | NS | + | − | + | |

| Neuropsychiatric symptoms/ mood | + | + | + | − | + | NS | + | |

| Caregiver distress/ burden | + | |||||||

| Quality of life | + | + | NS | |||||

| Physical health measures | + | |||||||

| ADLs | NS | NS | ||||||

| Neural connectivity | + | + | ||||||

| Biomarkers | + | |||||||

| Adverse events | 5** | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported | Not reported | 0 | Not reported |

| Side effects*** | dizziness | Minor muscle strain |

Demonstrated improvement. NS Demonstrated no change.

Demonstrated worsening of symptoms.

ADLs = activities of daily living.

Only patient data is presented.

Adverse events were dizziness/nausea (2 occurrences), legs buckling later in the day, falling forward on hands and knees during class, and hip pain.

Two studies reported no adverse events but did report side effects.

Quasi-experimental trials of yoga:

Fan and Chen20 found significant differences between the yoga and control groups at post-intervention on measures of neuropsychiatric symptoms, cardiopulmonary functioning, flexibility, muscle strength and endurance, and balance. Although they did not control for pre-intervention measurement of these variables, they found no significant differences between the two groups on any of these measures at pre-intervention. Litchke, Hodges, and Reardon21 conducted analyses of change scores from pre- to post-intervention. A significant increase in depressive symptoms was observed, while no significant changes were found on measures of balance, activities of daily living (ADLs), anxiety, or memory.

Quasi-experimental trials of multi-component interventions:

In the first of two studies, Lenze and Wetherell22 found that participants demonstrated significant improvements on measures of immediate (Cohen’s d= 0.83) and delayed verbal memory (Cohen’s d = 0.75), verbal fluency (Cohen’s d =0.20), and executive functioning (Cohen’s d = 0.39) upon completion of the intervention. No differences in outcomes were found based on program length. Barnes and colleagues found that Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIE),23,24 an integrative movement intervention, produced moderate to large effect sizes on measures of cognitive functioning (pre-post dppc2 = 0.76), physical performance (pre-post dppc2 = 0.34), quality of life (pre-post dppc2 = 0.83), caregiver distress (pre-post dppc2 = .21), and caregiver burden (pre-post dppc2 = 0.49). Using change scores from pre-to post-intervention, Paller and colleagues25 found that participants in a mindfulness intervention demonstrated improvements in depressive symptoms, quality of life, executive functioning, and verbal memory.

RCTs of yoga:

Eyre et al26 found that participants in both the yoga and memory enhancement training (MET) groups showed improvements in immediate (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.95; MET: Cohen’s d = 1.06) and delayed recall verbal memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.96; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.59), and immediate (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.54; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.72) and delayed visual memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.48; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.64) upon completion of the intervention. Improvements in immediate recall verbal memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.98; MET: Cohen’s d = 1.18), delayed recall verbal memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.65; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.34-trend), immediate recall visual memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.39; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.82), and delayed recall visual memory (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.75; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.76) were maintained at the 12-week follow-up assessment. However, only yoga participants continued to report improvements in delayed recall verbal memory. Further, only the yoga participants demonstrated significantly greater improvement in executive functioning at both post-intervention (Cohen’s d ranged from 0.41 to 0.71) and 12-week follow-up assessments (Cohen’s d ranged from −0.46 to −0.75 and 0.41–0.71). With respect to mood, both groups demonstrated improvements in apathy (Yoga: Cohen’s d = 0.52; MET: Cohen’s d = 0.89) but only the yoga group demonstrated improvements in depression (Cohen’s d =- 0.62) and resilience (Cohen’s d = 0.40).

RCTs of multi-component interventions:

Wells and colleagues27,28 found that MBSR participants scored worse than the control participants on one measure of attention and executive function (Trail Making Test). The authors hypothesized that this finding was due to order of the testing and fatigue. Trends for improvement were seen in a global measure of cognition for the MBSR group and worsening for the control group. Non-significant trends for improvement with MBSR were also seen in measures of resilience, perceived stress, quality of life, hope and optimism.28 In their second study, Wetherell and Lenze29 reported that MBSR participants experienced improvements in both memory (Cohen’s d = 0.28) and mood (Cohen’s d = −0.46 to −0.48). They also found an interaction with cortisol, with MBSR participants with high levels of baseline cortisol experiencing a significant decline in cortisol relative to participants in the health education intervention.

Safety:

Five of the eight reviewed studies report on the negative effects of yoga. Two studies reported that participants experienced no adverse events.20,28 Two studies reported no adverse events, but stated that there were reports of minor muscle strains22 and one report of dizziness.26 One study reported dizziness/nausea (two occurrences), legs buckling later in day, falling forward on hands and knees during class, and hip pain; none of these were considered serious and they all resolved.23 One study did not explicitly discuss adverse events but there were no participant withdrawals from the intervention due to adverse events.29

Discussion

Evidence thus far suggests that yoga may have small to large beneficial effects on cognitive functioning in persons with self-reported memory problems, MCI, and dementia. This finding is consistent with research including persons without dementia. Gothe and colleagues18 recently conducted a meta-analysis of yoga studies that reported cognitive outcomes. They found significant improvements in cognition after a single yoga session. Studies that examined the impact of longer term yoga found moderate effects on cognition. Effects were strongest for measures of attention, processing speed, and executive function, followed by memory. While this meta-analysis included participants of all ages, an RCT of yoga for older adults also reported consistent findings. Hariprasad et al.19 compared yoga with a waitlist control in a sample of 87 adults living in senior housing. None had a diagnosis of dementia, but almost two thirds had subjective memory complaints. After controlling for education and baseline scores, yoga participants showed significant improvements in immediate and delayed recall of verbal memory, delayed recall of verbal memory, attention, and processing speed. Lin and colleagues30 compared yoga with aerobic exercise in a sample of women with a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder within 5 years of onset. While participants in both conditions experienced improvements in working memory, participants who received yoga also experienced moderate to large improvements in verbal acquisition and attention. Thus, research suggests that yoga may improve attention, processing speed, and verbal memory.

How might yoga impact cognitive functioning?

Sleep:

Sleep disturbance is common in adults with AD, with up to 45% of patients reporting sleep problems.31,32 Problems include insomnia, sleep fragmentation, excessive daytime sleepiness, and phase shifts. Sleep disturbances may also affect cognitive functioning, as memory consolidation processes that occur during sleep are disrupted.33,34 Although none of the studies reviewed here included sleep as an outcome, other studies have found that yoga reduces sleep latency, increases hours spent sleeping, increases feelings of restfulness in the morning, and improves subjective sleep quality.35–37

Further, there is some evidence that yoga-induced improvements in sleep may mediate the effects of yoga on cognition. Janelsins and colleagues38 conducted secondary analyses on data from an RCT of yoga for cancer survivors who were 2–24 months post cancer treatment and had significant sleep disturbance. Results indicated that yoga participants experienced significant improvements in memory complaints with improvements in sleep partially mediating this relationship. Although sleep and memory were both self-reported, findings from this study suggest that the relationships among yoga, sleep, and cognition should be further examined.

Mood:

Neuropsychiatric symptoms, including symptoms of anxiety and depression, are very prevalent in MCI and dementia, with rates ranging from 15–30%.39 It is uncertain if mood disturbances are precursors to the development of dementia, are associated with the diagnosis (i.e., given the high rate of progression from MCI to dementia-50%, the diagnosis of MCI can be anxiety-inducing), are highly comorbid, or a combination of these. This issue is particularly important, as neuropsychiatric symptoms are associated with greater caregiver burnout.40,41 Thus, an intervention that can reduce these symptoms may result in better care and a longer period of remaining in the home.

Seven of the studies reviewed assessed mood and related symptoms, and five found that the interventions produced improvements in symptoms.20,22,23,25,26,29 Overall these studies suggest that yoga can improve mood and neuropsychiatric symptoms in cognitively impaired adults. This is an important issue because these symptoms can severely influence patients’ ADLs and cognitive performance. Yoga may impact mood through downregulation of the hypothalamic axis and sympathetic nervous system as evidenced by decreased cortisol, blood pressure, and inflammatory cytokines.42–44 One of the reviewed studies assessed cortisol before and after an MBSR intervention. They found that individuals with high baseline levels of cortisol experienced a decrease in peak cortisol after completing an MBSR program, while participants who received health education did not experience a significant change in cortisol.29

Increased Default Mode Network (DMN) neural connectivity:

The DMN is a network of brain regions that is active “at rest” when not actively engaged in a task. The DMN is important in memory processing and decreased DMN connectivity may be associated with AD.45 Two studies specifically analyzed fMRI data obtained before and after the intervention. Eyre found that after both the yoga and MET interventions, participants had increased functional connectivity between the anterior and posterior DMN that correlated with improvements in verbal memory and visuo-spatial memory.46 Thus, the neuroimaging findings seen after yoga were comparable to what was seen in MET. Similarly, Wells also found that after MBSR, participants had increased functional connectivity in the DMN, specifically between the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC) and the bilateral medial prefrontal cortex, and between the PCC and the left hippocampus compared with the control group.27

Hippocampal size and function:

The hippocampus shrinks in MCI and AD, and animal studies demonstrate that excessive levels of cortisol damage the hippocampus. Thus, lowering stress and cortisol through yoga may impact hippocampal function/structure. Only one study evaluated the impact of yoga on hippocampal size, and found trends for less hippocampal atrophy in the MBSR group compared with the control group.27 The sample size was small and larger studies are needed to replicate this finding. Yang’s study using 1H_MRS showed that MET but not yoga was associated with decreased choline levels in the bilateral hippocampus. Increases in choline in the hippocampus are seen with normal aging and dementia, so these results demonstrate that a behavioral intervention could reduce such age-related changes. Although the changes were not also seen in the yoga group, the authors argue that additional research is needed to see if this effect exists for yoga given the small sample size and exploratory nature of their study.46

Plasma repressor element 1-silencing transcription (REST) biomarker:

Ashton et al.47 showed that MBSR increased levels of REST compared with placebo, and that increases in REST were associated with reductions in depression and anxiety, which are often associated with stress and AD risk. These results suggest that a behavioral intervention like MBSR may alter plasma levels of a key regulator in the aging brain’s response to stress, with clinically significant effects.

These neuroimaging and biological data support the neuropsychological findings that yoga may improve cognitive functioning. Further, yoga may impact the brain regions most sensitive to MCI and AD.

What modifications might be needed for persons with dementia?

Declining cognitive abilities will impact yoga instruction. Patients with MCI and dementia may have difficulty with attention and carrying out multi-step commands. Thus, individual yoga classes or those with a smaller number of participants are recommended. Having multiple instructors, one to demonstrate the pose and one or more to work directly with individuals, may help dementia patients participate.20 Providing more verbal explanation in addition to the physical demonstration of the pose may be useful.23 Depending upon dementia severity, patients may not remember poses from previous classes. Therefore, the class should be taught as if each pose is new to the participant. If home practice is a goal, having the caregiver present to learn the pose can be useful for increasing practice.23 Similarly, starting with easier poses and gradually building to more complex poses may be helpful.

Baseline level of activity needs to be assessed. Patients who are regularly inactive may need to start with a shorter class length and gradually increase time to build endurance and stamina.21 Further, some individuals will be at greater risk of falls. In these cases, chair yoga is recommended.21,48 Poses can be modified to be performed while seated in order to minimize risk of falls and injury. With these modifications, yoga for cognitively impaired older adults is safe, with only minor safety events reported in the reviewed studies.

What is needed to advance the field?

There are a number of limitations of the existing studies. Yoga interventions are varied and not well described. The style of yoga, components of the intervention, dose (frequency and duration of practice), selection of instructors, and monitoring of intervention fidelity should be consistently included in the description of the intervention.49 Randomized studies with appropriate attention control groups and larger sample sizes are needed. Only three of the studies reviewed were RCTs, and half the studies had fewer than 20 participants. The frequency and length of classes vary greatly from 1 to 3 times a week, from 30 to 150 minutes, and from 8 to 18 weeks. This variability makes it difficult to determine the dose of yoga needed to effect change. Further, the dose may vary depending upon the outcome of interest. For example, a meta-analysis of meditative movement interventions found that the frequency needed to be at least 3 times a week to effect change on sleep.50

A complicating issue for research on yoga in this population is the role of various underlying etiologies of cognitive impairment. Some studies contend that mixed pathologies, including the degenerative components caused by AD and vascular factors, are the most common explanation for cognitive impairment in aging.51 Further work is needed to determine if yoga has a differential effect on cognition based on the underlying pathophysiology of the cognitive impairment. In addition, future research could assess sleep, mood, and neural connectivity to further our understanding of how yoga may affect cognitive functioning.

Summary

Overall, the literature on the effects of yoga in cognitively impaired older adults is limited. Studies suggest that yoga is safe and feasible in adults with MCI and dementia, and may have beneficial effects on cognitive functioning, sleep, neuropsychiatric symptoms and mood, and the brain regions and functions most important to dementia. Further study is warranted. It should be noted that satisfaction with yoga is high22,26 and older adults view it as a credible treatment for improving mood symptoms.52 Given these considerations and the increasing availability of yoga in community settings, clinicians may consider recommending yoga to persons with MCI or dementia.

Acknowledgements:

This work was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (CER-1511-33007) and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (K23AT008406). The sponsor has provided the funds to complete the research. The sponsor is not involved in study design; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, nor the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No disclosures to report.

Contributor Information

Gretchen A. Brenes, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on Gerontology and Geriatric Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Stephanie Sohl, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Rebecca E. Wells, Department of Neurology, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Deanna Befus, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Claudia L. Campos, Department of Internal Medicine, Section on General Internal Medicine, Wake Forest School of Medicine

Suzanne C. Danhauer, Department of Social Sciences and Health Policy, Wake Forest School of Medicine

References Cited

- 1.National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. 2018; https://nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga.

- 2.Satchidananda SS. Integral yoga hatha U.S.A.: Integral Yoga Publications; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, Barnes PM, Nahin RL. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National health statistics reports 2015(79):1–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cramer H, Ward L, Steel A, Lauche R, Dobos G, Zhang Y. Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Yoga Use: Results of a U.S. Nationally Representative Survey. American journal of preventive medicine 2016;50(2):230–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stussman BJ, Black LI, Barnes PM, Clarke TC, Nahin RL. Wellness-related Use of Common Complementary Health Approaches Among Adults: United States, 2012. National health statistics reports 2015(85):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, Dobos G. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depression and anxiety 2013;30(11):1068–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofmann SG, Andreoli G, Carpenter JK, Curtiss J. Effect of Hatha Yoga on Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of evidence-based medicine 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Dobos G. A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga for low back pain. The Clinical journal of pain 2013;29(5):450–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cramer H, Posadzki P, Dobos G, Langhorst J. Yoga for asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 2014;112(6):503–510.e505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagins M, States R, Selfe T, Innes K. Effectiveness of yoga for hypertension: systematic review and meta-analysis. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2013;2013:649836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward L, Stebbings S, Cherkin D, Baxter GD. Yoga for functional ability, pain and psychosocial outcomes in musculoskeletal conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal care 2013;11(4):203–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu XC, Pan L, Hu Q, Dong WP, Yan JH, Dong L. Effects of yoga training in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of thoracic disease 2014;6(6):795–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danhauer SC, Addington EL, Sohl SJ, Chaoul A, Cohen L. Review of yoga therapy during cancer treatment. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 2017;25(4):1357–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mooventhan A, Nivethitha L. Evidence based effects of yoga in neurological disorders. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia 2017;43:61–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cramer H, Lauche R, Anheyer D, et al. Yoga for anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Depression and anxiety 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cramer H, Lauche R, Haller H, Steckhan N, Michalsen A, Dobos G. Effects of yoga on cardiovascular disease risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International journal of cardiology 2014;173(2):170–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mooventhan A, Nivethitha L. Evidence based effects of yoga practice on various health related problems of elderly people: A review. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2017;21(4):1028–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gothe NP, McAuley E. Yoga and Cognition: A Meta-Analysis of Chronic and Acute Effects. Psychosomatic medicine 2015;77(7):784–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hariprasad VR, Koparde V, Sivakumar PT, et al. Randomized clinical trial of yoga-based intervention in residents from elderly homes: Effects on cognitive function. Indian journal of psychiatry 2013;55(Suppl 3):S357–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fan JT, Chen KM. Using silver yoga exercises to promote physical and mental health of elders with dementia in long-term care facilities. International psychogeriatrics / IPA 2011;23(8):1222–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Litchke LG, Hodges JS, Reardon RF. Benefits of Chair Yoga with Mild to Severe Alzheimer’s Disease. Activities, Adaptation & Aging 2012;36(4):317–328. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenze EJ, Hickman S, Hershey T, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for older adults with worry symptoms and co-occurring cognitive dysfunction. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2014;29(10):991–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barnes DE, Mehling W, Wu E, et al. Preventing loss of independence through exercise (PLIE): a pilot clinical trial in older adults with dementia. PloS one 2015;10(2):e0113367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu E, Barnes DE, Ackerman SL, Lee J, Chesney M, Mehling WE. Preventing Loss of Independence through Exercise (PLIE): qualitative analysis of a clinical trial in older adults with dementia. Aging & mental health 2015;19(4):353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paller KA, Creery JD, Florczak SM, et al. Benefits of mindfulness training for patients with progressive cognitive decline and their caregivers. American journal of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias 2015;30(3):257–267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eyre HA, Siddarth P, Acevedo B, et al. A randomized controlled trial of Kundalini yoga in mild cognitive impairment. International psychogeriatrics / IPA 2017;29(4):557–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells RE, Yeh GY, Kerr CE, et al. Meditation’s impact on default mode network and hippocampus in mild cognitive impairment: a pilot study. Neuroscience letters 2013;556:15–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells RE, Kerr CE, Wolkin J, et al. Meditation for adults with mild cognitive impairment: a pilot randomized trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2013;61(4):642–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wetherell JL, Hershey T, Hickman S, et al. Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction for Older Adults With Stress Disorders and Neurocognitive Difficulties: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of clinical psychiatry 2017;78(7):e734–e743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin J, Chan SK, Lee EH, et al. Aerobic exercise and yoga improve neurocognitive function in women with early psychosis. NPJ schizophrenia 2015;1(0):15047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moran M, Lynch CA, Walsh C, Coen R, Coakley D, Lawlor BA. Sleep disturbance in mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep medicine 2005;6(4):347–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCurry SM, Reynolds CF, Ancoli-Israel S, Teri L, Vitiello MV. Treatment of sleep disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease. Sleep medicine reviews 2000;4(6):603–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rauchs G, Harand C, Bertran F, Desgranges B, Eustache F. [Sleep and episodic memory: a review of the literature in young healthy subjects and potential links between sleep changes and memory impairment observed during aging and Alzheimer’s disease]. Revue neurologique 2010;166(11):873–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rauchs G, Schabus M, Parapatics S, et al. Is there a link between sleep changes and memory in Alzheimer’s disease? Neuroreport 2008;19(11):1159–1162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen KM, Chen MH, Chao HC, Hung HM, Lin HS, Li CH. Sleep quality, depression state, and health status of older adults after silver yoga exercises: cluster randomized trial. International journal of nursing studies 2009;46(2):154–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Halpern J, Cohen M, Kennedy G, Reece J, Cahan C, Baharav A. Yoga for improving sleep quality and quality of life for older adults. Alternative therapies in health and medicine 2014;20(3):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manjunath NK, Telles S. Influence of Yoga and Ayurveda on self-rated sleep in a geriatric population. The Indian journal of medical research 2005;121(5):683–690. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janelsins MC, Peppone LJ, Heckler CE, et al. YOCAS(c)(R) Yoga Reduces Self-reported Memory Difficulty in Cancer Survivors in a Nationwide Randomized Clinical Trial: Investigating Relationships Between Memory and Sleep. Integrative cancer therapies 2016;15(3):263–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Hu Z, Jiang Z, Zhou F. Prevalence of anxiety in patients with mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of affective disorders 2018;236:211–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allegri RF, Sarasola D, Serrano CM, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as a predictor of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment 2006;2(1):105–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lou Q, Liu S, Huo YR, Liu M, Liu S, Ji Y. Comprehensive analysis of patient and caregiver predictors for caregiver burden, anxiety and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of clinical nursing 2015;24(17–18):2668–2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Riley KE, Park CL. How does yoga reduce stress? A systematic review of mechanisms of change and guide to future inquiry. Health psychology review 2015;9(3):379–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pascoe MC, Bauer IE. A systematic review of randomised control trials on the effects of yoga on stress measures and mood. Journal of psychiatric research 2015;68:270–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rocha KK, Ribeiro AM, Rocha KC, et al. Improvement in physiological and psychological parameters after 6 months of yoga practice. Consciousness and cognition 2012;21(2):843–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones DT, Machulda MM, Vemuri P, et al. Age-related changes in the default mode network are more advanced in Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2011;77(16):1524–1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eyre HA, Acevedo B, Yang H, et al. Changes in Neural Connectivity and Memory Following a Yoga Intervention for Older Adults: A Pilot Study. Journal of Alzheimer’s disease : JAD 2016;52(2):673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ashton NJ, Hye A, Leckey CA, et al. Plasma REST: a novel candidate biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease is modified by psychological intervention in an at-risk population. Translational psychiatry 2017;7(6):e1148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCaffrey R, Park J, Newman D, Hagen D. The effect of chair yoga in older adults with moderate and severe Alzheimer’s disease. Research in gerontological nursing 2014;7(4):171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman KJ. Guidelines for developing yoga interventions for randomized trials. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM 2012;2012:143271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu WW, Kwong E, Lan XY, Jiang XY. The Effect of a Meditative Movement Intervention on Quality of Sleep in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, NY) 2015;21(9):509–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the american heart association/american stroke association. Stroke 2011;42(9):2672–2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ayers CR, Sorrell JT, Thorp SR, Wetherell JL. Evidence-based psychological treatments for late-life anxiety. Psychology and aging 2007;22(1):8–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang H, Leaver AM, Siddarth P, et al. Neurochemical and Neuroanatomical Plasticity Following Memory Training and Yoga Interventions in Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment. Frontiers in aging neuroscience 2016;8:277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]