Abstract

NKX2-1 is a lung epithelial lineage transcription factor that promotes differentiation and suppresses malignant progression of lung adenocarcinoma. However, Nkx2-1 targets that limit tumor growth and progression remain incompletely understood. Here, we identify direct Nkx2-1 targets whose expression correlates with NKX2-1 activity in human lung adenocarcinoma. We further investigate selenium binding protein 1 (Selenbp1), an Nkx2-1 effector that limits phenotypes associated with lung cancer growth and metastasis. Using loss- and gain-of-function approaches, we show that Nkx2-1 is required and sufficient for Selenbp1expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells. Interestingly, Selenbp1 knockdown also reduced Nkx2-1 expression and Selenbp1 stabilized Nkx2-1 protein levels in a heterologous system, suggesting that these genes function in a positive feedback loop. Selenbp1 inhibits clonal growth and migration and suppresses growth of metastases in an in vivo transplant model. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated deletion of Selenbp1also enhanced primary tumor growth in autochthonous lung adenocarcinoma mouse models. Collectively, our data are consistent with Selenbp1 being a direct target of Nkx2-1, which inhibits lung adenocarcinoma growth in vivo.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma, metastasis, lineage transcription factor, tumor suppressor, tumor growth

Introduction

Lineage-specific transcription factors have emerged as key regulators of cancer growth, progression, and metastasis (1–7). Transcription factors related to Drosophila NK2 are key regulators of organ development and homeostasis (8,9). In lung adenocarcinoma, several transcription factors have been identified that influence tumorigenesis and metastatic ability, including the NK2-related homeobox transcription factor Nkx2-1(3,6,7,10–12). In human lung adenocarcinoma and in genetically engineered mouse models, Nkx2-1 expression is generally high in well-differentiated tumors but is down-regulated in highly-proliferative poorly-differentiated tumor areas (10,12,13). Gain- and loss-of-function experiments suggest that Nkx2-1 limits tumor growth and metastatic ability (10,12–14). Targeted inactivation of Nkx2-1 in normal lung epithelial cells and early neoplasias increases proliferation (13). Thus, Nkx2-1 is a key regulator of multiple cancer-associated phenotypes.

Despite the experimental and clinical data underscoring the importance of NKX2-1 in lung adenocarcinoma, few direct NKX2-1 targets that control these phenotypes have been identified and verified through functional studies. Myosin binding protein H and occludin are both direct NKX2-1 targets that reduce motility and metastatic ability (15,16). However, additional work is required to understand the subsets of NKX2-1 targets that are critical for inhibiting tumor growth and progression in vivo.

Through a global analysis of putative direct Nkx2-1 target genes, we identified Selenium binding protein 1 (Selenbp1/Sbp1) as an effector of the tumor growth suppressive effect of Nkx2-1 in lung adenocarcinoma. Selenbp1 is highly expressed in several adult tissues, including the lung (17–20), and reduced SELENBP1 expression is associated with poor patient outcome in many human cancer types (18,19,21–25). We demonstrate that Selenbp1 inhibits lung adenocarcinoma growth and migration and provide evidence that Selenbp1 and Nkx2–1 may exist in a positive feedback loop. These results suggest that Selenbp1 is an important suppressor of lung tumor growth and progression.

Material and Methods

Human gene expression analysis

Human lung adenocarcinoma TCGA mRNA expression data (26) was downloaded from cBioPortal, and correlations were plotted using cBioPortal (27,28). Correlations from the Directors Challenge human lung adenocarcinoma microarray expression data were plotted using Microsoft Excel (29). Analysis of lung adenocarcinoma survival in KMPlotter (30) indicated that high SELENBP1 (Probe: 214422_s_at) predicts outcomes most significantly in the lung adenocarcinoma subset of patients (Figure 1h). Data was split on the median.

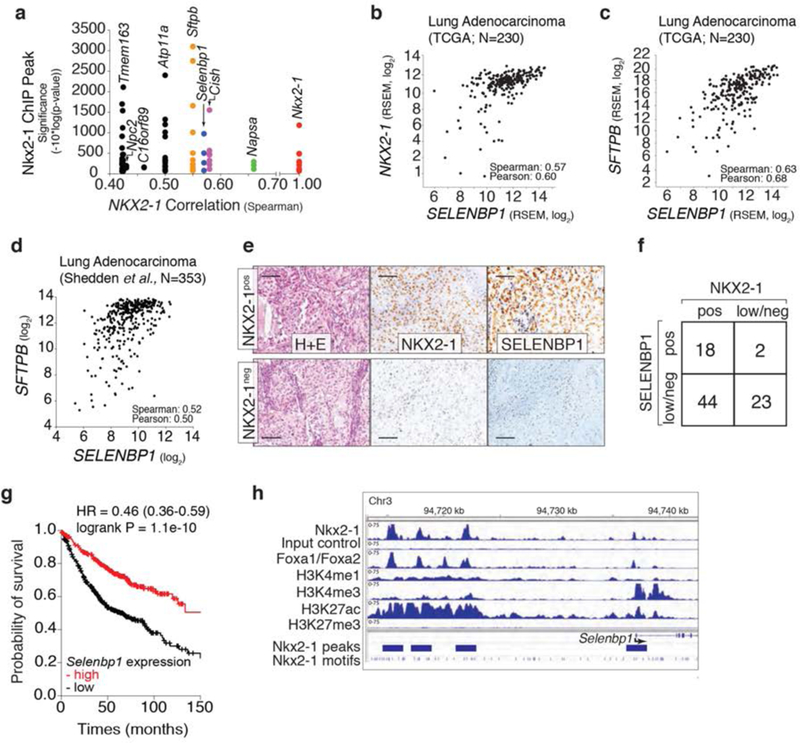

Figure 1: SELENBP1 is an Nkx2-1 target that is co-ordinately expressed with Nkx2-1 in human lung cancer.

a. Selenbpl has multiple proximal Nkx2-1 ChlP-seq peaks and SELENBP1 expression correlates with Nkx2-1 expression in human lung adenocarcinoma. Each dot represents a ChlP-seq peak associated with a particular gene.

b, c. SELENBP1 expression correlates with Nkx2-1 expression (b), and the expression of the Nkx2-1 target gene surfactant protein b (SFTPB)(c) in human lung adenocarcinoma. Each dot represents a tumor.

d. SELENBP1 expression correlates with SFTPB expression in human lung adenocarcinoma. Each dot represents a tumor.

e. Representative immunohistochemical staining of an Nkx2-1positive and an Nkx2-1negativea, human lung adenocarcinoma. Scale bar = 100 μm.

f. SELENBP1 and Nkx2-1 protein levels scored as low/negative (low/neg) or positive (pos) from human lung adenocarcinoma TMA. The relationship between SELENBP1 and Nkx2-1 is statistically significant (calculated using a 2×2 contingency table). * P ≤ 0.05.

g. Lung adenocarcinoma patient outcome stratified by SELENBP1 expression. Analysis of 720 patients from GEO (Affymetrix microarrays), EGA, and TCGA (Szasz etal., 2016). P-value and hazard ratio are indicated.

h. ChlP-seq data for Nkx2-1, Foxa1/Foxa2, and histone marks around Selenbp1 in murine lung tumors.

ChIP-seq analysis

The ChIP-seq datasets were generated previously (13). ChIP-seq peaks with a peak significance above 10−6 were associated with genes using GREAT analysis (31). Peaks were assigned to genes if they were located 20,000 base pairs upstream and 1000 base pairs downstream of the TSS.

Cell lines, lentiviral gene knock-down, and retroviral gene expression

The 394T4, 368T1, and 389T2 cell lines was generated from lung tumors in a lung adenocarcinoma-bearing KrasLSL-G12D/+;p53flox/flox mouse and have been described, and 394T4 TdTomato cell line was generated by transducing the cell lines with MSCV retrovirus containing tdTomato (12,32,33). 389T2.TdTom and 389T2.CFP cell lines were generated by transducing the cell lines with MSCV retrovirus containing tdTomato or CFP fluorescent proteins. Lentiviral vectors were used to knockdown Nkx2-1 in mouse cell lines with a previously verified shRNA(12). Two hairpins (Sigma Aldrich) were validated for knockdown of Selenbp1 in mouse cell lines (TRCN0000101186, TRCN0000101188), and human cell lines (TRCN0000005702, TRCN0000005703). The murine stem cell virus retroviral (MSCV) expression system was used to re-express Nkx2-1, and the fluorescent proteins tdTomato and CFP. Max Diehn’s laboratory kindly shared the human lung cancer cell line H441. Transfection of MSCV retroviral plasmids was used to express GFP, Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 in 293T cells. No Mycoplasma testing was performed on the cell lines, and cells were used for experiments within 3-5 days of thawing.

Histologic preparation and IHC

Tissues were fixed in 4% formalin overnight and transferred to 70% ethanol until paraffin embedding. IHC was performed on 4μ,m section with the ABC Vectastain Kit (Vector Laboratories) using the Cadenza system followed by hematoxylin counterstaining. The following primary antibodies were used Nkx2-1 (Abcam: ab76013), Selenbp1 (Abcam: ab90135), GFP (Cell Signaling: 2956), RFP (Rockland: 600401379), BrdU (BD Pharmingen; 555627). Sections were developed with DAB and counterstained with hematoxylin. For in vivo BrdU labeling, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 50 mg/kg of BrdU 24 hours before analysis. The number of BrdU positive cancer cells was quantifed by IHC and direct counting, taking into account the morphologic feature of cancer cells and excluding areas directly adjacent to necrotic areas. The lung cancer tissue microarray TMA LC20815, containing 208 human patient cores (85 lung adenocarcinoma) was obtained from US Biomax, Inc., and stained for NKX2-1 and SELENBP1 using IHC.

Low density plating

3×103 cells were seeded per 10 cm plate. Mouse cell lines were allowed to grow for one week before quantification.

Low density plating quantification

ImageJ was used to analyze colony number. Each image was changed to 8-bit greyscale, then the threshold was adjusted to 180 pixels. Under the process menu, the image was changed to binary, and then converted to mask. The area for counting was circled with freehand selections. The particles were analyzed with a size limit of 150 pixels to infinity.

RNA-seq analysis

RNA-seq data generated previously from a KrasG12D;p53-deficient;tdTomato-expressing (KPT) tumors (33). This data was aligned with genes identified from ChIP-seq data using a python script, and genes with a log2 fold-change larger than −2 (genes that are downregulated in metastasis) were identified.

Quantitative PCR

qRT-PCR was performed using Sybr green according to standard protocols. Samples were run in triplicate and normalized to GAPDH. The following primers were used to assess RNA levels:

Mouse Nkx2-1: Forward 5’ gatggtacggcgccaacccag 3’ and Reverse 5’ actcatattcatgccgctcgc 3’

Mouse Sftpb: Forward 5’ aaccccacacctctgagaac 3’ and Reverse 5’gtgcaggctgaggcttgt 3’

Mouse Selenbp1: Forward 5’ tcttcaaagatggcttcaacc 3’ and Reverse 5’ ctgccagtcccacacaaata 3’?

Mouse Gapdh: Forward 5’ cagcctcgtcccgtagac 3’ and Reverse 5’ cattgctgacaatcttgagtga 3’

Human NKX2-1: Forward 5’ aggacaccatgaggaacag 3’ and Reverse 5’ cccatgaagcgggagat 3’

Human SELENBP1: Forward 5’ cagcgcttctacaagaacga and Reverse 5’ tgatcaggcctggcattt 3’

Human ACTIN: Forward 5; ccttgcacatgccggag 3’ and Reverse 5’ gcacagagcctcgcctt 3’

Western blotting

For western blotting, denatured protein samples were run on a 4-12% Bis-Tris (NuPage) and transferred onto PVDF membrane. Membranes were immunoblotted using primary antibodies. The following antibodies were used to assess protein levels:

Selenbp1: Abcam: ab90135

Nkx2-1: Abcam: ab76013 (EP1584Y)

Primary antibody incubations were followed by secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2005) and anti-rabbit (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2004) antibodies, and membranes were developed with ECL 2 Western Blotting Substrate (P180196, ThermoScientific Pierce).

BrdU cell culture assay

To assess proliferation 105 cells were plated in each well of a 6 well plate. Twelve hours later, the subconfluent cells were labelled with 10μM BrdU for 2 hours, followed by anti-BrdU staining using the BD APC flow kit according the manufacturer’s instructions.

Migration assay

For migrations assays, cells were plated in triplicate in 10 cm plates, overnight such that confluency was reached the next day. A 200 μl pipette tip was used to initiate the scratch. The gap was monitored over time and the gap measurement/analysis was quantified using ImageJ. Migration assays were also performed in the presence of mitomycin C by seeding 1 million cells in each well of a 6 well plate overnight. Two hours prior to the scratch assay 5 ug/ml of mitomycin C was added to the media. A 200 μl pipette tip was used to initiate the scratch. The gap was monitored over time and the gap measurement/analysis was quantified using ImageJ.

Presto blue assay

Proliferation was assessed using PrestoBlue Cell Viability Reagent (A13261, Invitrogen), with 2×103 cells seeded per well of a 96 well plate.

Cell transplantation and analysis

Six-week-old male B6129SF1/J mice (Jax stock #101043) of similar weights were used for the transplantation experiments. For intravenous transplantation, 1×105 cells were injected into the lateral tail vein (in 200 μl PBS) of B6129SF1/J recipient mice. Mice were analysed 3 weeks after transplantation. For analyses, lungs were examined under a fluorescent dissecting microscope for tdTomatopositive tumor number, and then fixed for IHC. Tumor area relative to total lung area was quantified using ImageJ on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections.

Mouse Strains and tumor induction

KrasLSL-G12D/+, R26LSL-tdTomato, H11LSL-Cas9, and p53flox have been previously described (31,48,78,79). The Lenti-U6sgRNA/PGK-Cre vector was generated as previously described(34). Lenti-U6sgSelenbp1#1/PGK-Cre was co-transfected with packaging vectors (delta8.2 and VSV-G) into 293T cells using TransIT-LT1 (Mirius Bio). The supernatant was collected at 48 and 72 hours, ultracentrifuged at 25,000 rpm for 90 minutes, and resuspended in PBS. Tumors were initiated by intratracheal transduction of mice with Lenti-U6sgSelenbp1#1/PGK-Cre, and tumors were allowed to develop for four months. Two hundred thousand viral particles were injected into KT and KT;Cas9 mice, and Twenty-five thousand particles were injected into KPT and KPT;Cas9 mice. Mice were analyzed by examining the lungs, pleural cavity, liver, kidneys, and spleen under a fluorescent microscope for tumors. Lung tissue was fixed for IHC staining. The Stanford Institute of Medicine Animal Care and Use Committee approved all animal studies and procedures.

Tracking indels by Decomposition (TIDE analysis)

Cutting efficiency was calculated using the free online webtool (35).

Results

Selenbp1 is an Nkx2-1 target in lung adenocarcinoma

To identify candidate Nkx2-1-regulated genes in lung adenocarcinoma, we integrated datasets from human lung adenocarcinoma and a defined mouse lung cancer model. To uncover genes that are likely to be directly regulated by Nkx2-1, we analyzed an Nkx2-1 ChlP-seq dataset generated from oncogenic KrasG12D-driven murine lung tumors (13). We next determined how well the expression of these putative direct Nkx2-1 target genes correlate with NKX2-1 expression in human lung adenocarcinoma (27,28,36). This analysis uncovered several canonical Nkx2-1 target genes including surfactant protein B (Sftpb) and Nkx2-1 itself, as well as several potentially novel Nkx2-1 target genes (Figure 1a). Consistent with the Nkx2-1 ChlP-seq data from mouse tumors, NKX2-1 also bound regions near NAPSA, NPC2, and SELENBP1 in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (H441; ChlP-seq data from (37); (Supplemental Figure 1a)). To initially assess the function of Napsa, Npc2, and Selenbp1 in lung adenocarcinoma cells, we used multiple small hairpin RNAs to stably knockdown each gene in an Nkx2-1pos lung adenocarcinoma cell line derived from the genetically-engineered KrasLSL-G12D;p53flox/flox (KP) mouse model (Supplementary Figure 1b–d)(12,38). Selenbp1 knockdown elicited the most dramatic increase in clonal growth ability when the cells were plated in low-density conditions (Supplemental Figure 1e,f). This data, in combination with the correlation between SELENBP1 and NKX2-1 in human lung adenocarcinoma, focused our additional validation and mechanistic experiments on this novel Nkx2-1-regulated gene.

Analysis of multiple human lung adenocarcinoma gene expression datasets confirmed that SELENBP1 expression correlates with NKX2-1 expression, as well as with the expression of the NKX2-1 target SFTPB (Figure 1b–d, and Supplemental Figure 2a). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on human lung adenocarcinomas uncovered a general correlation between NKX2-1 and SELENBP1 protein expression (Figure 1e,f, and Supplemental Figure 2b). Low SELENBP1 expression occurred in Nkx2-1pos tumors, however NKX2-1low/negative tumors were almost always SELENBP1low/negatlve (Figurele–f, and Supplemental Figure 2b). Higher expression of NKX2-1 in lung adenocarcinoma correlates with better patient outcome (39,40) and we confirmed that higher expression of SELENBP1 was also significantly associated with better patient outcome (Figure 1g).

To further investigate the regulation of Selenbp1 by Nkx2-1, we examined the Nkx2-1 ChIP-seq peaks upstream of Selenbp1 (Figure 1h)(13). One small Nkx2-1-bound peak was located in the promoter region of Selenbp1, while three larger peaks were identified further upstream of Selenbp1 (Figure 1h). We next examined the histone modifications associated with these regions. The Nkx2-1 bound region at the promoter of Selenbp1 was associated with H3K4me3 (a marker of active genes)(41) and H3K27ac (a marker of activity at promoters and enhancers)(42), while the putative enhancer regions were bound by H3K4me1 (a marker of enhancers and promoters) and H3K27ac (a marker of enhancers)(43). H3K27me3 (a marker of Polycomb-mediated gene repression (44,45)) was absent from both the promoter and putative enhancer regions (Figure 1h). Collectively, this suggests that Nkx2-1 likely regulates the expression of Selenbp1 through both its enhancer and promoter regions. Foxa1/Foxa2 also bound the promoter and enhancer regions suggesting co-regulation of Selenbp1 by Nkx2-1 and a Foxa transcription factor (Figure 1h)(46–50). The pattern of chromatin marks around other known Nkx2-1 targets, including Sftpb and Nkx2-1 itself were consistent with the co-ordinate regulation of a large number of genes by these factors (Supplemental Figure 2b,c)(13,51–53).

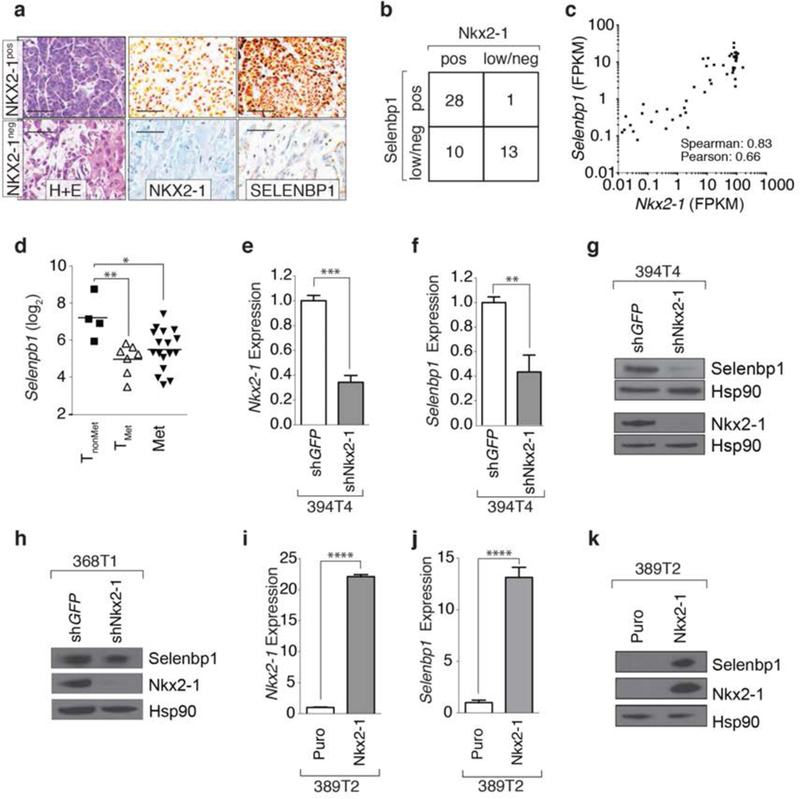

We recently characterized the global gene expression changes that occur in neoplastic cells during tumor progression and metastasis in a KrasG12D-driven, p53-deficient lung adenocarcinoma mouse model (33). As anticipated, the expression of Nkx2-1 and canonical Nkx2-1 target genes correlated with the expression Selenbp1. In fact, Selenbp1 was more than 7-fold lower in pleural disseminated tumor cells and metastases than primary non-metastatic tumors (Supplemental Figure 3 and 4a). Immunohistochemistry for Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 on primary tumors and metastases from KrasLSL-Gl2D/+;p53flox/flox;R26LSL-tdTomato (KPT) mice confirmed that Nkx2-1low/negative areas were most often Selenbp1low/negative. This is consistent with the lower expression of SELENBP1 protein in poorly differentiated human lung adenocarcinomas (Figure 2a,b)(18). The early stage lung tumors that develop in p53-proficient KrasLSL-G12D/+;R26LSL-tdTomato (KT) mice are almost exclusively Nkx2-1pos and were most often Selenbp1pos (Supplemental Figure 4b,c).

Figure 2: Selenbpl and Nkx2-1 expression correlates in murine lung tumors and Nkx2-1 is required and sufficient for Selenbp1 expression.

a. Immunohistochemical staining for Nkx2-1 and Selenbpl on lung tumors from Kra&LSL-G12D/+;p53flox/flox;R26LSL-tdTomato (KPT) mice. H&E staining illustrates less differentiated areas with low Nkx2-1 and Selenbpl expression. Scale bar = 50 μm.

b. Correlation between Nkx2-1 and Selenbpl expression scored as low/negative (low/neg) or positive (pos) in KPT lung tumors quantified by immunohistochemistry. **’* P <0.0001

c. Correlation between Nkx2-1 and Selenbpl expression in tumors from KrasLSL-G12D/+R26LSL-tdTomato(KT) and KPT mice.

d. Selenbpl expression is significantly lower in cell lines derived from metastatic primary lung tumors and métastasés from KP mice. * P <0.05, ** P <0.01

e,f. Stable knockdown of Nkx2-1 reduces Nkx2-1 (e) and Selenbp1 (f) expression in a TnonMet cell line (394T4). Normalized expression relative to shGFP and Gapdh. qRT-PCR mean +/− SD of triplicate wells. *** P <0.001, ** P <0.01.

g,h. Western blot for Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 in cell lines (394T4 and 368T1) with stable knockdown of Nkx2-1. Hsp90 shows loading.

i,j. Re-expression of Nkx2-1 in a TnonMet cell line (389T2) increases Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 expression. Expression relative to Gapdh and normalized to control (Puro) vector. qRT-PCR Mean +/− SD of triplicate wells. ”** P <0.0001.

k. Western blot for Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 in 389T2 cells re-expressing Nkx2-1. Hsp90 shows loading.

The Nkx2-1-bound regions upstream of Selenbp1 are closest to the Selenbp1 transcriptional start site, but these enhancer regions could nonetheless regulate the expression of other nearby genes (Supplemental Figure 3c). Unlike Selenbp1 (Figure 2c), the expression of other genes in proximity of the NKX2-1 bound enhancer regions did not correlate with the expression of Nkx2-1 or Sftpb in cancer cells from different stages of metastatic progression from KT and KPT mice (Supplemental Figure 3a and 4d). The other genes within the same region as SELENBP1 also did not correlate with NKX2-1 expression in human lung adenocarcinoma (Figure 1b–d, Supplemental Figure 3c).

Collectively, these data document a clear correlation between the expression of the transcription factor Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 in lung cancer, which is consistent with our initial identification of Nkx2-1 bound regions proximal to Selenbp1.

Nkx2-1 is required for Selenbp1 expression in lung adenocarcinoma cells

In cell lines generated from the KP lung cancer mouse model, Selenbp1 correlated with Nkx2-1 and Sftpb expression (Supplemental Figure 4e,f). Selenbp1 expression was high in Nkx2-1pos cell lines generated from non-metastatic primary tumors (TnonMet) and low in Nkx2-1negative cell lines generated from metastatic primary tumors (TMet) and metastases (Met)(12)(Figure 2d). To determine whether Nkx2-1 is sufficient and/or required for Selenbp1 expression, we performed gain- and loss-of function experiments with these mouse lung adenocarcinoma cell lines. We stably knocked-down Nkx2-1 using previously validated small hairpin RNAs, in two cell lines derived from non-metastatic primary tumors from the KP mouse model (TnonMet; 394T4 and 368T1)(12). We confirmed knockdown of Nkx2-1 at the RNA and protein levels (Figure 2e,g,h and Supplemental Figure 5a). Down regulation of the canonical Nkx2-1 target gene Sftpb confirmed reduced Nkx2-1 activity in the shNkx2-1 TnonMet cell lines (Supplemental Figure 5b,c). In both TnonMet cell lines, Nkx2-1 knock-down greatly reduced Selenbp1 mRNA and protein (Figure 2f, g, h and Supplemental Figure 5d). To determine whether Nkx2-1 is sufficient to drive Selenbp1 expression, we overexpressed Nkx2-1 in a cell line derived from a metastatic primary tumor (TMet; 389T2)(Figure 2i, j, and k, and Supplemental Figure 5e)(12). Overexpression of Nkx2-1 in these cells induced expression of Selenbp1, as well as the expression of the canonical Nkx2-1 target Sftpb (Figure 2i, j, and k, and Supplemental Figure 5e).

To investigate whether Nkx2-1 is required for SELENBP1 expression in human cell lines, we examined SELENBP1 expression in a published gene expression dataset from a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (H441) with and without Nkx2-1 knockdown (37). Nkx2-1 knockdown resulted in a 4-fold decrease in Nkx2-1 expression and a ~2-fold decrease in SELENBP1 expression (Supplemental 5f-g). SFTPB expression was also ~2-fold lower in Nkx2-1 knockdown H441 cells (Supplemental Figure 5h)(37). These data suggest that Nkx2-1 regulates the expression of Selenbp1 in lung adenocarcinoma.

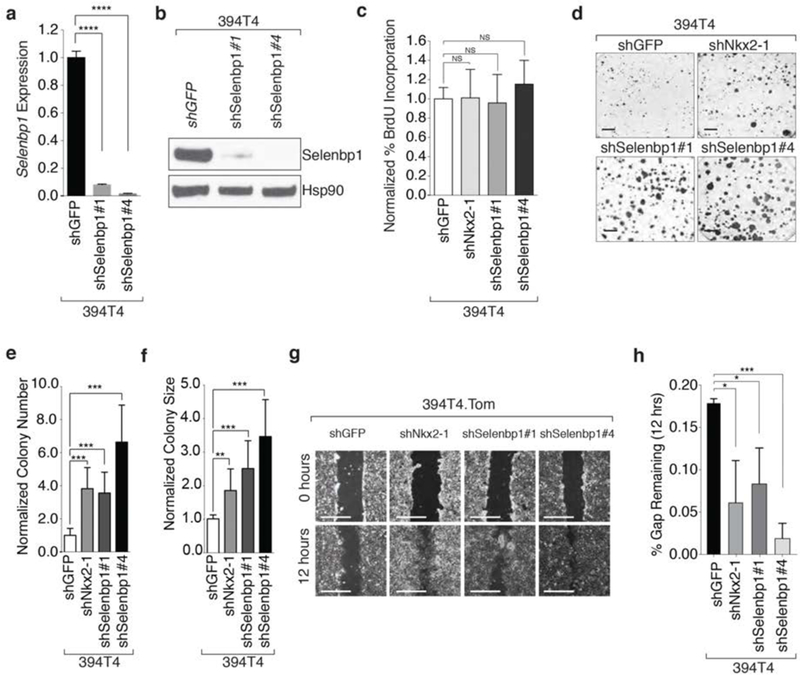

Selenbp1 inhibits clonal growth and migration

To assess the molecular and cellular phenotypes controlled by Selenbp1, we knocked down Selenbp1 with two independent shRNAs in the TnonMet cell lines and confirmed Selenbp1 knockdown at the RNA and protein levels (Figure 3a,b, and Supplemental Figure 5i,j). Using these knockdown cell lines, we performed a series of assays to investigate the function of Selenbpl on proliferation and cell migration. Selenbp1 knockdown had little if any effect on cell growth under standard culture conditions (Figure 3c and Supplemental Figure 5k–o). In contrast, when plated at low-density, Selenbp1 knockdown cells formed significantly larger and considerably more numerous colonies than shGFP control cells (Figure 3d–f).

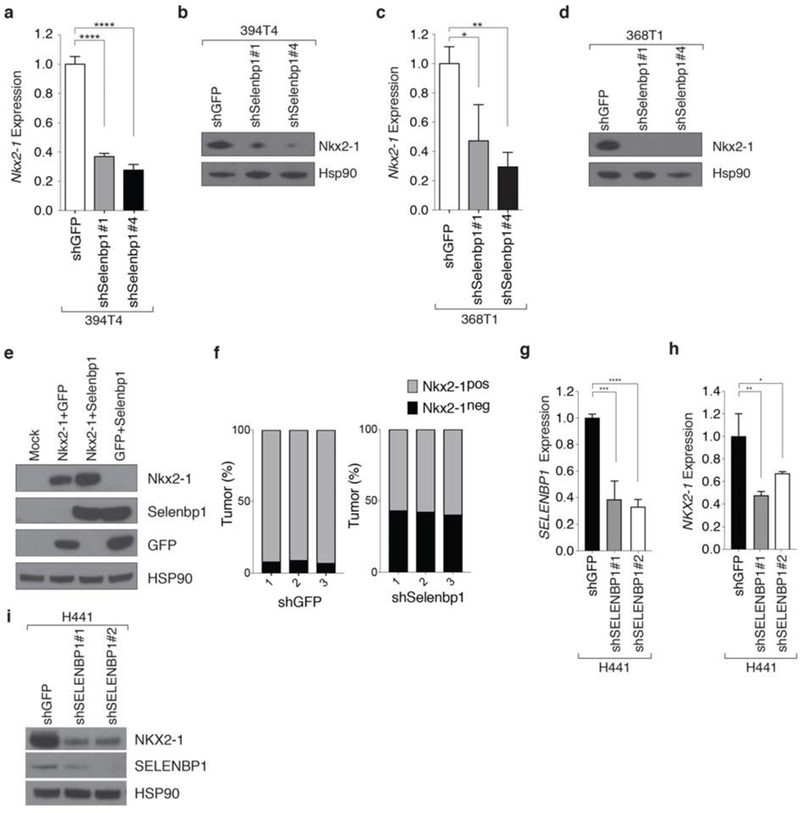

Figure 3: Nkx2-1 and its target Selenbp1 inhibit clonal growth and migratory ability.

a. shRNA-mediated knockdown of Selenbp1 using two hairpins significantly reduces Selenbp1 expression in a TnonMet cell line (394T4). Normalized expression relative to shGFP and Gapdh. qRT-PCR mean +/− SD of triplicate wells. ****< 0 0001.

b. Western blot demonstrating stable knockdown of Selenbp1 394T4 cells. Hsp90 shows loading.

c. BrdU incorporation is not significantly increased by stable knockdown of Nkx2-1 or Selenbp1 in 394T4 cells. Representative of 4 independent experiments.

d. Representative images of low density colony formation of 394T4 cells with stable knockdown of Nkx2-1 or Selenbp1. Scale bar = 1 cm.

e.f. Colony number (e) and size (f) formed by 394T4 cells is significantly increased with stable knockdown of Nkx2-1 or Selenbp1. ** P ≤ 0.01, *** P ≤0.001. Representative of 3 independent experiments.

g. Representative images of scratch assays using the 394T4 cells with knockdown of Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 at 0 and 12 hours after scratching. Scale bar = 5 mm.

h. The TnonMet cell line (394T4) migrates significantly faster with knockdown of Nkx2-1 or Selenbp1. Mean +/− SD of triplicate wells.* P ≤ 0.05, *** P≤0.001.

Several studies have suggested that Nkx2-1 can inhibit migratory ability (7,15,37,54). We used a 2D migration assay to determine whether Nkx2-1 controls the migratory ability of lung adenocarcinoma cells in culture. Nkx2-1 knockdown increased the migratory ability of TnonMet cells, while doxycycline-regulatable induction of Nkx2-1 in a TMet line decreased migratory ability (Figure 3g,h and Supplemental Figure 6a-d). Both cell-intrinsic and secreted factors can influence migration; therefore, we determined whether the effect of Nkx2-1 knockdown on migration was cell autonomous. By performing migration assays with differentially labeled co-cultured control TMet and TMet.Nkx2-1 expressing cells, we found that re-expression of Nkx2-1 reduced migration even in the presence of control cells, consistent with its effect being cell autonomous (Supplemental Figure 6a–d).

Given the effect of Nkx2-1 on migration, we examined whether Selenbp1 also regulates migration in vitro. Selenbp1 knockdown significantly increased migratory ability of TnonMet cells (Figure 3g,h). To rule out that the increased migration of these cells was due to the slight increase in proliferation, we performed additional migration assays in the presence of proliferation inhibitor mitomycin C (Supplemental Figure 6e,f). The migration ability of Selenbp1 knockdown cells was still significantly higher than control cells, confirming that the effect of Selenbp1 on migration is independent of cellular proliferation (Supplemental Figure 6e,f).

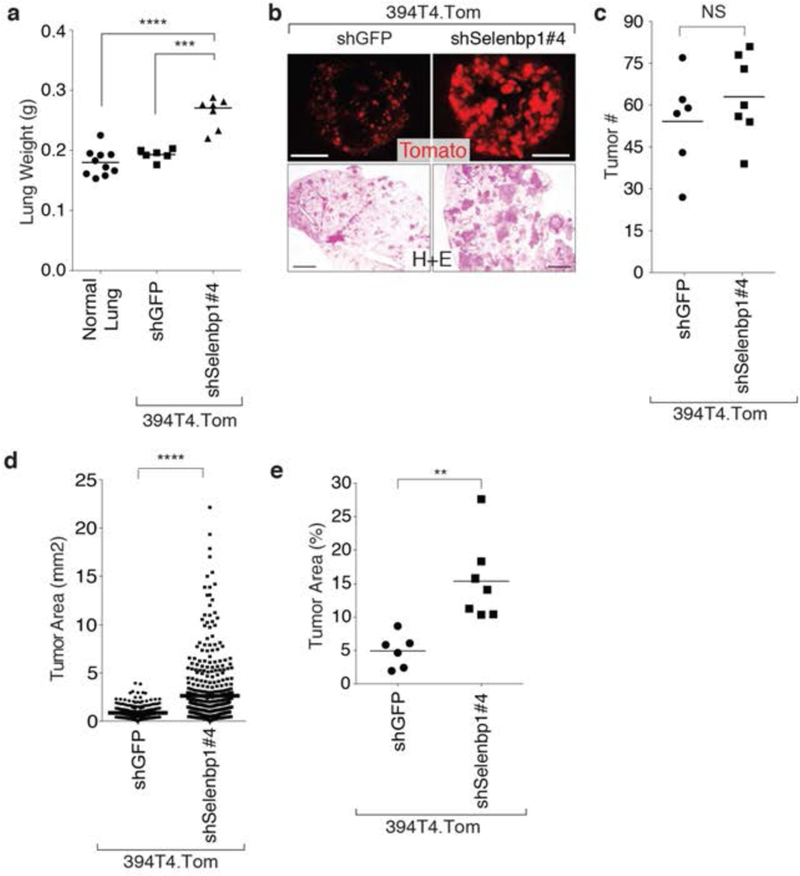

Selenbp1 suppresses tumor growth in vivo

To investigate the importance of Selenbp1 in tumor growth and metastasis in vivo, we intravenously transplanted TnonMet Selenbp1 knockdown and control cells into syngeneic recipient mice (Figure 4a–e). Selenbp1 knockdown significantly increased the total tumor burden as assessed by lung weight and percent tumor area (Figure 4a–e). While Selenbp1 knockdown did not significantly alter tumor number, the tumors that formed were larger suggesting that Selenbp1 inhibits tumor growth (Figure 4c,d,e).

Figure 4: Selenbp1 functions as an anti-metastatic factor.

a. Knockdown of Selenbp1 in an intravenously injected TnonMet cell line (394T4), results in significantly increased lung weight three weeks post-lnjection. Each dot represents a mouse, and the bar is the mean. *** P <0.001,****P <0.0001

b. Increased total tumor mass of a TnonMet, cell line (394T4), with Selenbp1 knockdown is shown by tdTomato fluorescent and H&E images. Fluorescent images, scale bar = 5 mm, H&E images, scale bar = 1mm.

c. Knockdown of Selenbp1 in a TnonMet cell line (394T4), intravenously injected, results in a slight but not significant increase in tumor number. Each dot represents a mouse, and the bar is the mean. NS = not significant.

d. Knockdown of Selenbp1 in a TnonMet cell line (394T4), intravenously injected, induces significantly larger tumors than control cells. Each dot represents a tumor, and the bar is the mean. *** P <0.0001

e. Tumor area is significantly higher after intravenous injection of a TnonMet cell line (394T4) compared to control cells. Each dot represents a mouse, and the bar is the mean. ** P <0.01

Selenbp1 increases Nkx2-1 protein level

In the course of our experiments on the Selenbp1 knockdown cells, we unexpectedly found that knockdown of Selenbp1 resulted in reduced Nkx2-1 expression at both the RNA and protein levels (Figure 5a–d). Given that Nkx2-1 regulates its own mRNA expression, these results could reflect an effect of Selenbp1 on either Nkx2-1 gene expression or Nkx2-1 protein level. To determine whether Selenbp1 can influence Nkx2-1 protein levels in a heterologous system, we expressed Nkx2-1 with and without exogenous Selenbp1 in 293T cells. Both Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 cDNAs were expressed using the 5’ long terminal repeat from the murine stem cell PCMV virus which drives high level constitutive expression. Nkx2-1 protein was consistently higher in the presence of co-expressed Selenbp1 suggesting Selenbp1 may stabilize Nkx2-1 protein (Figure 5e and Supplemental Figure 7a,b). We also examined Nkx2-1 protein expression in the tumors that formed after intravenous injection of control TnonMet and Selenbp1 knockdown cells. Compared to tumors from control cells, many more of the tumors that formed from shSelenbp1 cells were Nkx2-1neg (Figure 5f), This further supports the importance of Selenbp1 in maintaining Nkx2-1 expression.

Figure 5: Selenbp1 functions in a positive feedback loop with Nkx2-1.

a,b. Knockdown of Selenbp1 in the TnonMet cell line (394T4) significantly reduces Nkx2-1 mRNA (a) and protein (b) expression. Normalized gene expression relative to Gapdh. qRT-PCR mean +/− SD of triplicate wells. Hsp90 shows loading.****P <0.0001.

c,d. Knockdown of Selenbp1 in the TnonMet cell line (368T1) significantly reduces Nkx2-1 mRNA (c) and protein (d) expression. Normalized gene expression relative to Gapdh. qRT-PCR mean +/− SD of triplicate wells. Hsp90 shows loading * P <0.05, ** P <0.01.

e. Transient transfection of Selenbp1 increases the level of exogenous Nkx2-1 protein in 293 cells. HSP90 shows loading

f.Quantification of immunohistochemistry for Nkx2-1 expression in shGFP and shSelenbp1 lung tumors (from Figure 4). A higher percentage of Selenbp1 knockdown tumors are Nkx2-1neg compared with control shGFP tumors Data from 3 mice from each group is shown.

g,h. shRNA knockdown of SELENBP1 using two hairpins results in loss of SELENBP1 (f) and Nkx2-1 (g) expression in the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line H441. Normalized expression relative to ACTIN qRT-PCR Mean +/− SD of triplicate wells.* P <0.05, ** P <0.01, *** P <0.001, **** P<0 0001

i.In the human lung adenocarcinoma cell line H441 SELENBP1 knockdown using two hairpins decreases SELENBP1 and Nkx2-1 protein levels. HSP90 shows loading.

To determine if this feedback loop exists in human lung adenocarcinoma, we stably knocked down SELENBP1 with two separate shRNAs in a human lung adenocarcinoma cell line (H441). SELENBP1 knockdown resulted in a significant decrease in Nkx2-1 mRNA and protein expression (Figure 5g,h,i). This supports the possibility of a positive feedback loop between SELENBP1 and Nkx2-1 in lung adenocarcinoma which could contribute to the downregulation of Nkx2-1 during tumor progression.

Selenbp1 suppresses primary tumor growth

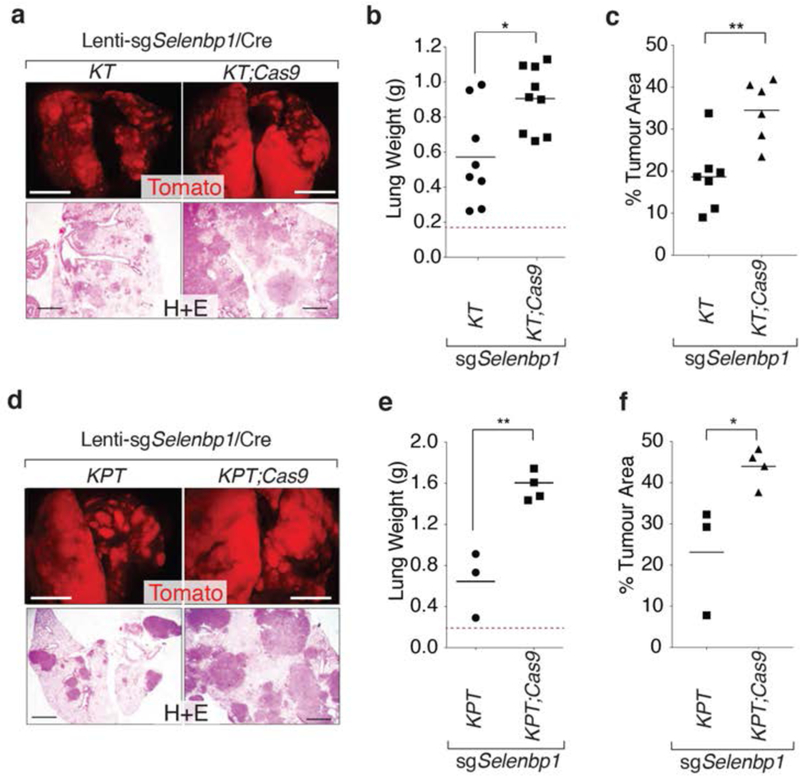

To determine whether Selenbp1 affects tumor growth in vivo, we used somatic CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing to inactivate Selenbp1 in KrasG12D-driven autochthonous lung tumors (34,55). We designed and validated an sgRNA targeting exon 2 of Selenbp1. We generated a lentiviral vector encoding this sgRNA and Cre-recombinase (Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre). We initiated tumors with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre in KrasLSL-G12D/+;R26LSL-tdTomato;H11LSL-Cas9 (KT;Cas9) and control KT mice. Four months after tumor initiation, KT;Cas9 mice had greater total tumor burden than control KT mice, as measured by lung weight and percent tumor area (Figure 6a–c). Lenti-sgSelenbpl/Cre-initiated tumors in KT;Cas9 mice had indels at the expected site in Selenbp1 (Supplemental Figure 8a). A higher proportion of lung tumors in KT;Cas9 mice were Selenbp1neg, compared with KT lung tumors (Supplemental Figure 8b). KT;Cas9 mice had a higher proportion of Selenbp1neg;Nkx2-1neg lung tumors, and a lower number of Selenbp1pos;Nkx2-1pos lung tumors compared with KT mice (Supplemental Figure 8c).

Figure 6: Selenbpl suppresses lung tumor growth.

a,b. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of Selenbp1 in KT;Cas9 mice increases tumor burden. Representative fluorescence dissecting scope and H&E images (a) and lung weight (b) of KTand KT:Cas9 with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre initiated tumors 4 months after initiation. Each dot represents a mouse, and the bar is the mean. Normal lung weight is indicated with a dashed line. * P <0.05. Fluorescent images scale bar = 5 mm, H&E images scale bar = 1 mm.

c. KT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre initiated tumors have greater tumor burden than KT mice. Each dot represents a mouse and the bar is the mean. ** P <0.01.

d,e. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeting of Selenbp1 in KPT;Cas9 mice increases tumor burden. Representative fluorescence dissecting scope and H&E images (d) and lung weight (e) of KPT and KPT;Cas9 with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre initiated tumors 4 months after initiation. Each dot represents a mouse, and the bar is the mean. Normal lung weight is indicated with a dashed line. ** P <0.01. Fluorescent images scale bar = 5 mm, H&E images scale bar = 1mm.

f. KPT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre initiated tumors have greater tumor burden than KPT mice. Each dot represents a mouse and the bar is the mean. * P <0.05

To investigate whether Selenbp1 deficiency could also increase the growth of KrasG12D-driven p53-deficient tumors in vivo, we initiated tumors with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre in KrasLSL-G12D/+;p53fl°x/flox;R26LSL-tdTomato;H11LSL-Cas9 (KPT;Cas9) and control KPT mice. Inactivation of Selenbp1 in KPT;Cas9 mice resulted in significantly larger tumors as measured by lung weight and percent tumor area as compared to control KPT mice (Figure 6d–f). Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre-initiated tumors in KPT;Cas9 mice had indels at the expected site in Selenbp1 and a higher proportion of lung tumors in KPT;Cas9 mice were Selenbp1neg (Supplementary Figure 8a, d). The expression of Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1, quantified by immunohistochemistry, significantly correlated in KPT;Cas9 lung tumors with a higher number of tumors being either Nkx2-1pos;Selenbp1pos or Nkx2-1neg;Selenbp1neg (Supplemental Figure 8e). Inactivation of Selenbp1 also increased the number of Hmga2positive;Nkx2-1negative;Selenbp1negative areas in KPT;Cas9 mice versus KPT mice (Supplemental Figure 8f). High expression of Hmga2 is a marker of poorly differentiated metastatic lung adenocarcinoma (32), and the increased number of Hmga2positive regions in KPT;Cas9 mice suggests that Selenbp1 inactivation may lead not only to increased tumor growth but also to increased tumor progression.

DISCUSSION

These studies were initiated to gain additional insight into the function of the Nkx2-1 transcription factor in lung cancer. Our analysis uncovered Selenbp1 as a tumor suppressive Nkx2-1 target gene. Cell culture assays, transplant experiments, and the analysis of autochthonous mouse models of lung cancer collectively indicate that Selenbp1 suppresses tumor growth in vivo.

Selenbp1 has been identified as a potentially important factor in several different cancer types (17–19,21,56). Our data suggest that Selenbp1 inhibits migration of lung adenocarcinoma cells in culture, which is consistent with its effect on colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines (Figure 3g, h, and Supplemental Figure 6e,f) (18,52). In lung cancer, Selenbp1 also reduced clonal growth, while in prostate cancer Selenbp1 inhibits anchorage-independent growth (57). Finally, using transplant models and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated inactivation in autochthonous mouse models of lung cancer, we show that Selenbp1 suppresses cancer growth in vivo. Functional evidence suggests that SELENBP1 inhibits growth in colorectal cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma and that overexpression of SELENBP1 enhances cisplatin sensitivity of esophageal adenocarcinoma (17,56,58,59). The capacity of Selenbp1 to change multiple phenotypes across numerous cancer types suggests that Selenbp1 plays a broad role in cancer growth and progression. While Selenbp1 expression is mechanistically linked to Nkx2-1 in lung cancer, different factors must control Selenbp1 expression in other cancer types.

The molecular functions of Selenbp1 in cancer are relatively poorly understood. Selenbp1 is expressed widely across many adult tissues and is an alpha-beta protein with several loop regions and one cysteine residue (Cys57)(19). In human liver, breast, and colorectal cancer cell lines, Selenbp1 inhibits glutathione peroxidase 1 (GPX1) enzymatic activity and decreased GPX1 activity correlates with decreased invasiveness (58,60). In prostate cancer cells, Selenbp1 binds to deubiquitinating factors, potentially playing a role in the regulation of ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation. However, whether ubiquitination is decreased or increased with Selenbp1 binding remains unclear (57,61). Most recently, Selenbp1 was identified as a novel human methanethiol oxidase that, when mutated, causes extraoral halitosis (62). Our findings suggest that Selenbp1 may play an important role in stabilizing Nkx2-1 protein. Whether the effect of Selenbp1 on Nkx2-1 protein levels represents a direct biochemical link between these proteins remains unknown. In the shRNA studies in this manuscript both Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 inhibit clonal growth and migration (Figure 3). These data suggest that either the knockdown of Nkx2-1 inhibits these phenotypes through a signaling cascade mediated by the feedback loop between Selenbp1 and Nkx2-1, or that other factors downstream of Selenbp1 induce the phenotypes observed. In human lung adenocarcinomas some of Nkx2-1 positive tumors have low Selenbp1 expression, indicating that Nkx2-1 maybe necessary but not sufficient for endogenous expression of Selenbp1. Understanding the connection between Nkx2-1 and Selenbp1 will be an important area of future study.

Selenium itself has been investigated for nearly half a century as a cancer therapeutic(63–67). Selenium containing proteins include: proteins with nonspecifically incorporated selenium, specific selenium binding proteins (like Selenbp1), and selenocysteine-containing proteins (68). Interestingly, in a mouse model of familial adenomatous polyposis (Apcmin), treatment with an organoselenium compound significantly decreased the development of small intestine and colon tumors (69). In a transgenic mouse model of liver cancer, both selenium deficiency and selenium supplementation suppressed carcinogenesis, suggesting that there may be an ideal level of selenium, and both too much or too little can be anti-tumorigenic. In lung cancer, several studies have examined the role of selenium as a chemopreventative agent (65,70). A recent clinical trial and meta-analysis concluded that selenium supplementation does not decrease lung cancer incidence in an unselected population, but significantly decreases incidence among patients with low baseline selenium (71,72).

Understanding the regulation of Nkx2-1 remains an important question as it serves dual functionality as both an oncogene in some human lung adenocarcinomas and a suppressor of cancer progression in others (3,5,10,12,73). Thus, within these different contexts, a better understanding of the regulators of Nkx2-1 expression could uncover strategies to down-regulate oncogenic Nkx2-1 or increase Nkx2-1 expression to limit tumor growth and progression. Despite its importance in lung cancer and known ability to regulate its own expression, other pathways that control Nkx2-1 expression in lung cancer are not well understood (44,45,69). Several other transcription factors bind to the promoter of Nkx2-1 in lung epithelial cells; however, whether these factors also contribute to the regulation of Nkx2-1 in lung cancer has not been well characterized (6,53,74–76). Our knock-down data suggest that Selenbp1 may positively regulate Nkx2-1. Other factors also act as regulators of Nkx2-1 expression, emphasizing the importance of Nkx2-1 function in development and cancer(77–78). However, Selenbp1 inactivation in vivo appears insufficient to lead to the loss of Nkx2-1 in lung adenomas and early stage lung adenocarcinomas in vivo, suggesting that Selenbp1 downregulation likely contributes to Nkx2-1 downregulation only within certain cellular contexts. Rescue experiments examining how Selenbp1 re-expression in Selenbp1 knockdown cell lines would be beneficial in a deeper understanding of how Selenbp1 impacts the tumor suppressive phenotypes uncovered in this manuscript. Additionally, defined mutant forms of Selenbp1, expressed in knockdown cell lines would provide additional insight into the function of Selenbp1 and into its mechanism of tumor suppression.

KrasG12D-driven Nkx2-1 heterozygous lung tumors in mice can progress to become Nkx2-1-negative mucinous adenocarcinomas, consistent with the development of mucinous lung adenocarcinoma in KrasLSL-G12D/+;Nkx2-1flox/flox mice (13,14,79). Inactivation of Selenbp1 by somatic CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in KrasG12D-driven mouse models, did not induce mucinous adenocarcinoma over the timeframe of our studies. In KT;Cas9 mice with Lenti-sgSelenbp1/Cre-initiated tumors, more than half of Selenbp1neg tumors were also Nkx2-1neg. However, the presence of Selenbp1neg Nkx2-1pos tumors suggests that loss of Selenbp1 alone is not sufficient to lead to complete loss of Nkx2-1 in vivo.

Our data suggest that Nkx2-1-driven expression of Selenbp1 inhibits tumor growth and progression of lung tumors. Selenbp1 may play an important role across cancer types, and future work on the molecular mechanism by which Selenbp1 alters cellular phenotypes associated with tumor growth and metastases will lead to an improved understanding of the mediators of tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Pauline Chu for technical assistance, the Stanford Shared FACS facility for technical support, Sean Dolan and Alexandra Orantes for administrative support, Sebastian Hoersch for help with the Nkx2-1 ChlP-seq analysis, and members of the Winslow laboratory for helpful comments. D.R.C. and I.P.W. were supported by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP). I.P.W. was additionally supported by NIH F31-CA210627 and NIHT32-HG000044. C-H.C. was supported by an American Lung Association Fellowship. E.L.S was supported by a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, a V Foundation Scholar award, and NIH R01-CA212415. This work was supported by NIH R01-CA175336 (to M.M.W.), a V Foundation Scholar award (to M.M.W.), and in part by the Stanford Cancer Institute support grant (NIH P30-CA124435).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Yatabe Y, Horio Y, Takahashi T. ASH1 Gene Is a Specific Therapeutic Target for Lung Cancers with Neuroendocrine Features Cancer Research. American Association for Cancer Research; 2005;65:10680–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garraway LA, Sellers WR. Lineage dependency and lineage-survival oncogenes in human cancer. 2006;6:593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwei KA, Kim YH, Girard L, Kao J, Pacyna-Gengelbach M, Salari K, et al. Genomic profiling identifies TITF1 as a lineage-specific oncogene amplified in lung cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:3635–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nishikawa E, Osada H, Okazaki Y, Arima C, Tomida S, Tatematsu Y, et al. miR-375 is activated by ASH1 and inhibits YAP1 in a lineage-dependent manner in lung cancer Cancer Research. American Association for Cancer Research; 2011;71:6165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yamaguchi T, Hosono Y, Yanagisawa K, Takahashi T. Nkx2-1/TTF-1: An Enigmatic Oncogene that Functions as a Double-Edged Sword for Cancer Cell Survival and Progression. 2013;23:718–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung WKC, Zhao M, Liu Z, Stevens LE, Cao PD, Fang JE, et al. Control of Alveolar Differentiation by the Lineage Transcription Factors GATA6 and HOPX Inhibits Lung Adenocarcinoma Metastasis. 2013;23:725–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CM- C, Gocheva V, Oudin MJ, Bhutkar A, Wang SY, Date SR, et al. Foxa2 and Cdx2 cooperate with Nkx2-1 to inhibit lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Genes & Development. 2015;29:1850–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gehring WJ. Homeo boxes in the study of development. Science. 1987;236:1245–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim Y, Nirenberg M. Drosophila NK-homeobox genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1989;86:7716–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caswell DR, Chuang C-H, Yang D, Chiou S-H, Cheemalavagu S, Kim-Kiselak C, et al. Obligate Progression Precedes Lung Adenocarcinoma Dissemination. Cancer Discovery. 2014;4:781–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nguyen DX, Chiang AC, Zhang XH-F, Kim JY, Kris MG, Ladanyi M, et al. WNT/TCF signaling through LEF1 and HOXB9 mediates lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cell. 2009;138:51–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winslow MM, Dayton TL, Verhaak RGW, Kim-Kiselak C, Snyder EL, Feldser DM, et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. 2011;473:101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Snyder EL, Watanabe H, Magendantz M, Hoersch S, Chen TA, Wang DG, et al. Nkx2-1 Represses a Latent Gastric Differentiation Program in Lung Adenocarcinoma. Molecular Cell. 2013;50:185–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda Y, Tsuchiya T, Hao H, Tompkins DH, Xu Y, Mucenski ML, et al. Kras(G12D) and Nkx2-1 haploinsufficiency induce mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4388–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hosono Y, Yamaguchi T, Mizutani E, Yanagisawa K, Arima C, Tomida S, et al. MYBPH, a transcriptional target of TTF-1, inhibits ROCK1, and reduces cell motility and metastasis. EMBO J. 2012;31:481–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Runkle EA, Rice SJ, Qi J, Masser D, Antonetti DA, Winslow MM, et al. Occludin is a direct target of thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1/Nkx2-1). J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28790–801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pohl NM, Tong C, Fang W, Bi X, Li T, Yang W. Transcriptional Regulation and Biological Functions of Selenium-Binding Protein 1 in Colorectal Cancer In Vitro and in Nude Mouse Xenografts. Navarro A, editor. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen G, Wang H, Miller CT, Thomas DG, Gharib TG, Misek DE, et al. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 expression is associated with poor outcome in lung adenocarcinomas. J Pathol. 2004;202:321–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Raucci R, Colonna G, Guerriero E, Capone F, Accardo M, Castello G, et al. Structural and functional studies of the human selenium binding protein-1 and its involvement in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1814:513–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang PW, Tsui SK, Liew C, Lee CC, Waye MM, Fung KP. Isolation, characterization, and chromosomal mapping of a novel cDNA clone encoding human selenium binding protein. J Cell Biochem. 1997;64:217–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim H, Kang HJ, You KT, Kim SH, Lee KY, Kim TI. Suppression of human selenium-binding protein 1 is a late event in colorectal carcinogenesis and is associated with poor survival. Proteomics. 2006;6:3466–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang S, Li F, Younes M, Liu H, Chen C, Yao Q. Reduced selenium-binding protein 1 in breast cancer correlates with poor survival and resistance to the anti-proliferative effects of selenium. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2013;8:e63702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeng G-Q, Yi H, Zhang P-F, Li X-H, Hu R, Li M-Y, et al. The Function and Significance of SELENBP1 Downregulation in Human Bronchial Epithelial Carcinogenic Process. Kang T, editor. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ha Y-S, Lee GT, Kim Y-H, Kwon SY, Choi SH, Kim T-H, et al. Decreased selenium-binding protein 1 mRNA expression is associated with poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. BioMed Central; 2014;12:288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang C, Wang YE, Zhang P, Liu F, Sung CJ, Steinhoff MM, et al. Progressive loss of selenium-binding protein 1 expression correlates with increasing epithelial proliferation and papillary complexity in ovarian serous borderline tumor and low-grade serous carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:255–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Network TCGAR, Weinstein JN, Collisson EA, Mills GB, Shaw KRM, Ozenberger BA, et al. The Cancer Genome Atlas Pan-Cancer analysis project. Nat Genet. Nature Research; 2013;45:1113–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio Cancer Genomics Portal: An Open Platform for Exploring Multidimensional Cancer Genomics Data: Figure 1. Cancer Discovery. American Association for Cancer Research; 2012;2:401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao J, Aksoy BA, Dogrusoz U, Dresdner G, Gross B, Sumer SO, et al. Integrative Analysis of Complex Cancer Genomics and Clinical Profiles Using the cBioPortal. Science Signaling. NIH Public Access; 2013;6:p11–p11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Director’s Challenge Consortium for the Molecular Classification of Lung Adenocarcinoma, Shedden K, Taylor JMG, Enkemann SA, Tsao M-S, Yeatman TJ, et al. Gene expression-based survival prediction in lung adenocarcinoma: a multi-site, blinded validation study. Nat Med. 2008;14:822–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Győrffy B, Surowiak P, Budczies J, Lánczky A. Online Survival Analysis Software to Assess the Prognostic Value of Biomarkers Using Transcriptomic Data in Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2013;8:e82241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McLean CY, Bristor D, Hiller M, Clarke SL, Schaar BT, Lowe CB, et al. GREAT improves functional interpretation of cis-regulatory regions. Nat Biotechnol. Nature Publishing Group; 2010;28:495–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brady JJ, Chuang C-H, Greenside PG, Rogers ZN, Murray CW, Caswell DR, et al. An Arntl2-Driven Secretome Enables Lung Adenocarcinoma Metastatic Self-Sufficiency. 2016;29:697–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chuang C-H, Greenside PG, Rogers ZN, Brady JJ, Yang D, Ma RK, et al. Molecular definition of a metastatic lung cancer state reveals a targetable CD109–Janus kinase–Stat axis. Nat Med. 2017;23:291–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiou S-H, Winters IP, Wang J, Naranjo S, Dudgeon C, Tamburini FB, et al. Pancreatic cancer modeling using retrograde viral vector delivery and in vivo CRISPR/Cas9-mediated somatic genome editing. Genes & Development. 2015;29:1576–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, van Steensel B. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Network TCGAR. Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature Publishing Group; 2014;511:543–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Isogaya K, Koinuma D, Tsutsumi S, Saito R-A, Miyazawa K, Aburatani H, et al. A Smad3 and TTF-1/Nkx2-1 complex regulates Smad4-independent gene expression. 2014;24:994–1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jackson EL. The Differential Effects of Mutant p53 Alleles on Advanced Murine Lung Cancer. Cancer Research. 2005;65:10280–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schilsky JB, Ni A, Ahn L, Datta S, Travis WD, Kris MG, et al. Prognostic impact of TTF-1 expression in patients with stage IV lung adenocarcinomas. Lung Cancer. 2017;108:205–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berghmans T, Paesmans M, Mascaux C, Martin B, Meert AP, Haller A, et al. Thyroid transcription factor 1--a new prognostic factor in lung cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1673–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Wysocka J. Methylation of Lysine 4 on Histone H3: Intricacy of Writing and Reading a Single Epigenetic Mark: Molecular Cell. Molecular Cell. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3K27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010;107:21931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Calo E, Wysocka J. Modification of Enhancer Chromatin: What, How, and Why? Molecular Cell. Elsevier; 2013;49:825–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Morey L, Helin K. Polycomb group protein-mediated repression of transcription. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 2010;35:323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ferrari KJ, Scelfo A, Jammula S, Cuomo A, Barozzi I, Stützer A, et al. Polycomb-Dependent H3K27me1 and H3K27me2 Regulate Active Transcription and Enhancer Fidelity. Molecular Cell. 2014;53:49–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikeda K, Shaw-White JR, Wert SE, Whitsett JA. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3 activates transcription of thyroid transcription factor 1 in respiratory epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:3626–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeFelice M, Silberschmidt D, DiLauro R, Xu Y, Wert SE, Weaver TE, et al. TTF-1 phosphorylation is required for peripheral lung morphogenesis, perinatal survival, and tissue-specific gene expression. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:35574–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Martis PC. C/EBP is required for lung maturation at birth. Development. 2006; 133:1155–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maeda Y, Dave V, Whitsett JA. Transcriptional Control of Lung Morphogenesis. Physiological Reviews. 2007;87:219–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Watanabe H, Francis JM, Woo MS, Etemad B, Lin W, Fries DF, et al. Integrated cistromic and expression analysis of amplified Nkx2-1 in lung adenocarcinoma identifies LMO3 as a functional transcriptional target. Genes & Development. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oguchi H, Kimura S. Multiple Transcripts Encoded by the Thyroid-Specific Enhancer-Binding Protein (T/EBP)/Thyroid-Specific Transcription Factor-1 (TTF-1) Gene: Evidence of Autoregulation 1. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1999–2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakazato M, Endo T, Saito T, Harii N, Onaya T. Transcription of the Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 (TTF-1) Gene from a Newly Defined Start Site: Positive Regulation by TTF-1 in the Thyroid. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;238:748–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boggaram V Thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1/Nkx2.1/TITF1) gene regulation in the lung. Clinical Science. 2009;116:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saito RA, Watabe T, Horiguchi K, Kohyama T, Saitoh M, Nagase T, et al. Thyroid Transcription Factor-1 Inhibits Transforming Growth Factor--Mediated Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition in Lung Adenocarcinoma Cells. Cancer Research. 2009;69:2783–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rogers ZN, McFarland CD, Winters IP, Naranjo S, Chuang C-H, Petrov D, et al. A quantitative and multiplexed approach to uncover the fitness landscape of tumor suppression in vivo. Nat Meth. Nature Research; 2017;14:737–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ansong E, Ying Q, Ekoue DN, Deaton R, Hall AR, Kajdacsy-Balla A, et al. Evidence That Selenium Binding Protein 1 Is a Tumor Suppressor in Prostate Cancer. PLoS ONE [Internet]. Public Library of Science; 2015;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jee-Yeong Jeong J-RZCGLFAJS. Human selenium binding protein-1 (hSP56) is a negative regulator of HIF-1α and suppresses the malignant characteristics of prostate cancer cells. BMB Reports. Korean Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2014;47:411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang C, Ding G, Gu C, Zhou J, Kuang M, Ji Y, et al. Decreased selenium-binding protein 1 enhances glutathione peroxidase 1 activity and downregulates HIF-1α to promote hepatocellular carcinoma invasiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:3042–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silvers AL, Lin L, Bass AJ, Chen G, Wang Z, Thomas DG, et al. Decreased Selenium-Binding Protein 1 in Esophageal Adenocarcinoma Results from Posttranscriptional and Epigenetic Regulation and Affects Chemosensitivity Clin Cancer Res. American Association for Cancer Research; 2010;16:2009–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fang W, Goldberg ML, Pohl NM, Bi X, Tong C, Xiong B, et al. Functional and physical interaction between the selenium-binding protein 1 (SBP1) and the glutathione peroxidase 1 selenoprotein. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1360–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeong J-Y, Wang Y, Sytkowski AJ. Human selenium binding protein-1 (hSP56) interacts with VDU1 in a selenium-dependent manner. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;379:583–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pol A, Renkema GH, Tangerman A, Winkel EG, Engelke UF, de Brouwer APM, et al. Mutations in SELENBP1, encoding a novel human methanethiol oxidase, cause extraoral halitosis Nat Genet. Nature Publishing Group; 2017;2:748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shamberger RJ. Relationship of selenium to cancer. I. Inhibitory effect of selenium on carcinogenesis. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;44:931–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shamberger RJ, Frost DV. Possible protective effect of selenium against human cancer. Can Med Assoc J. Canadian Medical Association; 1969;100:682. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark LC, Combs GF, Turnbull BW, Slate EH, Chalker DK, Chow J, et al. Effects of selenium supplementation for cancer prevention in patients with carcinoma of the skin. A randomized controlled trial. Nutritional Prevention of Cancer Study Group. JAMA. 1996;276:1957–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lippman SM, Klein EA, Goodman PJ, Lucia MS, Thompson IM, Ford LG, et al. Effect of selenium and vitamin E on risk of prostate cancer and other cancers: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2009;301:39–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karp DD, Lee SJ, Keller SM, Wright GS, Aisner S, Belinsky SA, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III chemoprevention trial of selenium supplementation in patients with resected stage I non-small-cell lung cancer: ECOG 5597. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31:4179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Behne D, Kyriakopoulos A. Mammalian Selenium-Containing Proteins. Annu Rev Nutr. 2001;21:453–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rao CV, Cooma I, Rodriguez JGR, Simi B, El-Bayoumy K, Reddy BS. Chemoprevention of familial adenomatous polyposis development in the APCmin mouse model by 1,4-phenylene bis(methylene)selenocyanate Carcinogenesis. Oxford University Press; 2000;21:617–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Patterson BH, Levander OA. Naturally occurring selenium compounds in cancer chemoprevention trials: a workshop summary. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1997. pages 63–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Reid ME, Duffield-Lillico AJ, Garland L, Turnbull BW, Clark LC, Marshall JR. Selenium supplementation and lung cancer incidence: an update of the nutritional prevention of cancer trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002; 11:1285–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fritz H, Kennedy D, Fergusson D, Fernandes R, Cooley K, Seely A, et al. Selenium and Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta Analysis. Zhivotovsky B, editor. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e26259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Clarke N, Biscocho J, Kwei KA, Davidson JM, Sridhar S, Gong X, et al. Integrative Genomics Implicates EGFR as a Downstream Mediator in Nkx2-1 Amplified Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. PLoS ONE. Public Library of Science; 2015;10:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shaw-White JR, Bruno MD, Whitsett JA. GATA-6 activates transcription of thyroid transcription factor-1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2658–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li C, Ling X, Yuan B, Minoo P. A novel DNA element mediates transcription of Nkx2.1 by Sp1 and Sp3 in pulmonary epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1490:213–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kang Y, Hebron H, Ozbun L, Mariano J, Minoo P, Jakowlew SB. Nkx2.1 transcription factor in lung cells and a transforming growth factor-?1 heterozygous mouse model of lung carcinogenesis Mol Carcinog. Wiley Subscription Services, Inc., A Wiley Company; 2004;40:212–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Herriges MJ, Tischfield DJ, Cui Z, Morley MP, Han Y, Babu A, et al. The NANCI-Nkx2.1 gene duplex buffers Nkx2.1 expression to maintain lung development and homeostasis. Genes & Development. Cold Spring Harbor Lab; 2017;31:889–903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mu D The complexity of thyroid transcription factor 1 with both pro-and anti-oncogenic activities J Biol Chem. American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology; 2013;288:24992–5000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Finberg KE, Sequist LV, Joshi VA, Muzikansky A, Miller JM, Han M, et al. Mucinous differentiation correlates with absence of EGFR mutation and presence of KRAS mutation in lung adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features. J Mol Diagn. 2007;9:320–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.