Abstract

Bacterial infections cause a major burden of disease worldwide. Sepsis and septic shock are life-threatening complications of infections. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis initiates the release of endogenous glucocorticoids that modulate the host stress response and acute inflammation during septic shock. It is an ongoing controversial debate, if therapeutic manipulations of the HPA axis could benefit the clinical situation in the context of shock. Here, we have studied Long Evans rats with hypophysectomy followed by endotoxic shock. The shock-associated lethality was substantially higher in hypophysectomized rats as compared to control mice after cranial sham surgery (7-day survival rates: 27% vs. 89%). Fluorimetric bead-based assays were used to quantify the release of >20 cytokines and chemokines. The surgical removal of the pituitary gland resulted in greatly increased plasma concentrations of mediators such as IL-1α/IL-1β (10–12-fold), TNFα (19-fold), IL-6 (111-fold), IL-10 (10-fold) as well as the Th1 cytokines, Interferon-γ (8-fold), IL-12 (4-fold) and IL-18 (9-fold) after intra-peritoneal lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injections. In contrast, MIP-1a and Leptin were negatively associated with hypophysectomy. The Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13, as well as G-CSF, VEGF, IP-10 and RANTES were not significantly affected. The gene expression of the IL-6/IL-12 family cytokine, IL-27p28 was profoundly increased after pituitary gland removal followed by endotoxic shock. A dose-dependent reduction of LPS/ TLR4-induced IL-27p28 release by glucococorticoids was observed in cultured rodent macrophages (C57BL/6J) as well as in vivo.

This study reveals that the neuroendocrine influences of the HPA axis on the shock-associated inflammatory response are more selective and complex than previously known. These findings will be helpful to predict some of the consequences of therapeutic manipulations of the HPA in the context of sepsis and septic shock.

Keywords: Immunology, Inflammation, Cytokines, Sepsis, Neurobiology, Infection

1. Introduction

Bacterial infections remain leading causes of morbidity and mortality around the globe [1,2]. Sepsis and septic shock are dangerous to life complications of uncontrolled infections. It is extrapolated from epidemiologic studies that around 20 million people worldwide are affected by sepsis annually [3,4]. Mortality rates are ranging around 30e50% [4]. There are no FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of sepsis or septic shock. The growing concerns for evolving antibiotic resistances are enlarging the important demand for a better understanding of the molecular host response to infections that result in shock. Bacterial pathogens are sensed by pattern recognitions receptors to elicit immune responses [5]. Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) are cell wall components of gram-negative bacteria acting as endotoxin. LPS ligates with Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) for triggering a strong inflammatory response [4]. This acute inflammation includes up-regulated gene expression and release of cytokines and chemokines [5]. It is well established that the release of these inflammatory mediators needs to be tightly controlled to balance protective anti-microbial effector functions against excessive tissue destruction and organ dysfunction. For instance, excessive release of cytokines such as IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IL-12, IL-18, Interferon-γ and IL-27 have been associated with detrimental outcomes in experimental sepsis models, while blockade or genetic deficiency is protective [4,6].

The nature and intensities of inflammatory responses are modulated by the neuroendocrine system of the central nervous system [7]. The pituitary gland is a neuroendocrine organ and secretes several hormones including adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) [7]. In the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, ACTH transmits an activating signal for the secretion of glucocorticoids to the adrenal glands [7,8]. A dysfunction of the pituitary gland with inadequate endogenous cortisol production is a common phenomenon during the stress response of human sepsis [9]. It has been a long and still ongoing debate of controversy, if therapeutic manipulations of the HPA axis (e.g. low-dose glucocorticoid infusions) are beneficial during human sepsis [10,11]. At the same time, the pleiotropic role of the pituitary gland for regulating the septic shock-associated inflammatory response including cytokine/chemokine release patterns remain an understudied area of sepsis research.

In this report, we demonstrate that surgical removal of the pituitary gland in rats results in a greatly increased susceptibility during endotoxin-induced shock along with a distinct dysregulation of cytokine release patterns.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Animal studies were in accordance with the U.S. National Institutes of Health guidelines and the Federation of European Laboratory Animal Science Associations guidelines, directive 2010/63/ EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of the European Union. Long Evans rats (males, >70 g body weight) were purchased from Taconic Biosciences including rats with the surgical modification of hypophysectomy and the corresponding sham surgery. C57BL/6J mice (males, >6 weeks of age) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories. All animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment, a temperature controlled light/dark cycle and with free access to food and water.

For endotoxic shock, the animals were weighed directly before intra-peritoneal injection in the lower right quadrant of the abdomen with Lipopolysaccharide from Escherichia coli (0111:B4; Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in sterile phosphate buffered saline (Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific). At the end of the experiments, venous blood was collected in EDTA (5–10 mM) tubes and plasma obtained by centrifugation (2,000 g, 10 min, 4 °C) followed by storage at —80 °C until analysis.

2.2. Quantification of mediators

A MILLIPLEX MAP rat cytokine/chemokine magnetic bead panel kit (Millipore) was used as a premixed multiplexed bead-based immunoassay. The analytes were IL-1α, IL1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12p70, IL-13, IL-17, IL-18, TNFα, IFNγ, KC (CXCL1), MCP-1 (CCL2), MIP-1α (CCL3), RANTES (CCL5), IP-10 (CXCL10), Eotaxin (CCL11), G-CSF, GM-CSF, VEGF and Leptin. The cell-free EDTA plasma samples were thawed on ice after cryopreservation and diluted 10-fold in assay diluent. The assay was performed according to the instructions of the manufacturer using an Aurum vacuum manifold (BioRad) for the washing steps. The samples were analyzed on the Luminex xMAP/Bioplex-200 System with BioPlex Manager Software 5.0. CXCL1 measurements were excluded because of values in the saturation phase above the highest standards.

Cortisol and mouse IL-27p28 (R&D Systems) were quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s protocols with sample dilution to fit into the standard range. The absorbance of standards and samples were measured using a SpectraMax 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

2.3. Reverse transcription and real-time PCR

Spleen tissues were homogenized, total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol method and RNA was quantified using a Nano-Quant Infinite M200 (Tecan) microvolume spectrophotometer. The cDNA was generated by mixing RNA samples with TaqMan reverse transcription reagents (Applied Biosystems) followed by conversion in a GeneAmp 9700 thermocycler (Applied Biosystems; 25 °C for 10 min, 48 °C for 30 min, 95 °C for 5 min). PCR reactions were run using the SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) in a 750 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems; 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 40 cycles: 95 °C for 10s, 60 °C for 60 s, 72 °C for 10 s, followed by acqusition of melting curves). The 2−∆∆Ct algorithm including normalization to GAPDH house-keeping gene expression was employed for the calculation of relative quantitative results. The primer sequences (Invitrogen) were as following: rat GAPDH forward primer 5′-CGGCAAGTTCAACGGCACAGTCA-3′, rat GAPDH reverse primer 5′-CTTTCCAGAGGGGCCATCCACAG-3′, rat IL-27p28 forward primer 5′-ATCTCCCCAATGTTTCCCTGACCT-3′, rat IL-27p28 reverse primer 5′-CCACAGCTGCTCCCTCTCTGAG-3’ [12].

2.4. Cell cultures

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) and thioglycollate-elicited peritoneal macrophages (PEM) were isolated from C57BL/6J mice as described by us before [6,13]. The cells were cultured in sterile 24-well tissue culture plates using RPMI 1640 medium containing 0.1% BSA and 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The macrophages were allowed at least 2 h for adherence before addition of glucocorticoids or Lipopolysaccharides (Escherichia coli, serotype O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich). Hydrocortisone was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and methylprednisolone, prednisolone, dexamethasone (APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC, Schaumburg, IL) were used as pharmaceutical-grade drugs.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The data represent the numbers of animals per group as indicated in the figure legends. The cell culture data is representative of at least 2–3 independent experiments each performed in duplicate wells. GraphPad Prism 8.0.0 was used for statistical analyses. Values are depicted as mean with error bars representing S.E.M. The statistical significance was determined using either the one-way ANOVA test or for survival curves the Logrank (Mantel-Cox) test. We considered differences significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

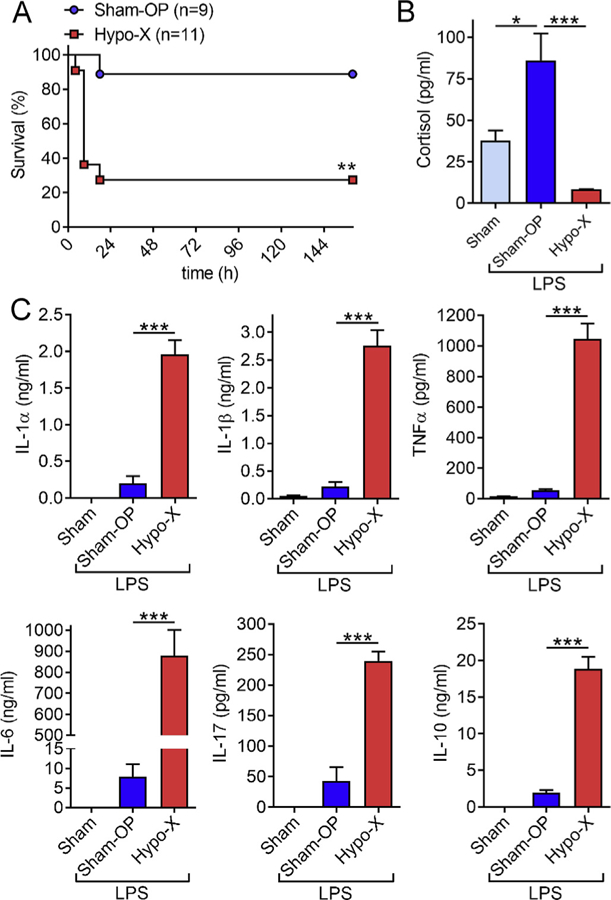

3.1. The pituitary gland protects from lethality of endotoxic shock

To study the role of the pituitary gland in shock, we investigated rats after surgical removal of the pituitary glands. These hypophysectomized rats (Hypo-X) were compared to rats after cranial sham surgery (Sham-OP) during endotoxic shock. In fact, the hypophysectomized rats displayed rapid worsening of clinical shock symptoms (data not shown) together with early shock-associated mortality and a survival rate of only 27% as compared to 89% in the Sham-OP control group after intra-peritoneal LPS injections (Fig. 1A). Endogenous plasma cortisol concentrations were increased in Sham-OP mice after LPS as compared to healthy untreated Sham rats without LPS (Fig. 1B). However, cortisol was barely detectable in hypophysectomized rats, which was in accordance with the expected disruption of the HPA axis and ACTH-dependent regulatory circuit (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

The pituitary gland protects from mortality and excessive release of inflammatory cytokines during endotoxic shock. (A) Hypophysectomy (Hypo-X, n = 11) or sham surgery (Sham-OP, n = 9) was performed in male Long Evans rats. After several weeks of recovery from the surgery, the rats received intra-peritoneal injections of LPS (5 mg/kg body weight) and survival was monitored for 7 days. (B) Endogenous cortisol concentrations in EDTA plasma were detected by ELISA at 6 h after LPS injection (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.) in rats after sham surgery (Sham-OP; n = 9) or hypophysectomy (Hypo-X; n = 8). Healthy untreated control rats (Sham; n = 5) received neither surgery nor LPS. (C) Rats of the three indicated groups received intra-peritoneal injection of LPS (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.) followed by collection of EDTA plasma 6 h later. The plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6, IL-17 and anti-inflammatory IL-10 were quantified by multiplexed bead based assays (Luminex-200). Dimensional units are either ng/ml or pg/ml as indicated on y-axes. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001.

3.2. Hypophysectomy results in a multiplication of inflammatory cytokines during endotoxic shock

Next, we studied the plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory IL-1α, IL-1β, TNFα, IL-6 and IL-17 together with anti-inflammatory IL-10. In the plasma of specific pathogen-free housed untreated healthy sham Long Evans rats all cytokines were virtually absent from plasma (Fig. 1C). While cytokine inductions were readily observed in Sham-OP rats in response to LPS, the levels of these mediators were substantially and significantly higher in hypophysectomized rats after 6 h (Fig. 1C). In detail, the relative increases between Sham-OP and Hypo-X groups were 6-fold for IL-17, 10-fold for both IL-1α and IL-10, 13-fold for IL-1β, 19-fold for TNFα and IL-6 was 111-fold increased. IL-6 was also the most abundant cytokine at the studied time point with concentrations of 879 ± 325 ng/ml in rats devoid of a pituitary gland (Fig. 1C). An early 6 h time point was chosen because shock-associated death of hypophysectomized rats started to occur shortly thereafter (≥9 h, Fig. 1A).

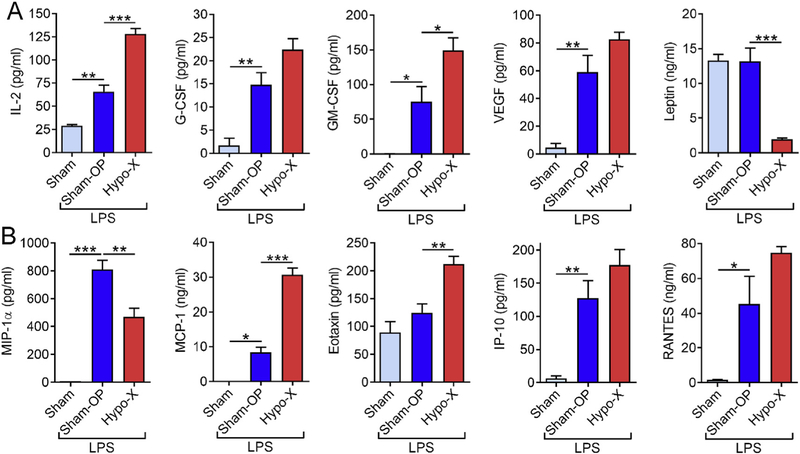

3.3. Differential effects of the pituitary gland on chemokines and growth factors

As the pituitary gland controls several growth hormones, we desired to specifically study its effects on hematopoietic growth factors. There was a moderate significant increase in plasma concentrations of T-cell trophic IL-2 and myeloid-cell trophic GM-CSF in rats after hypophysectomy (Hypo-X) as compared to sham operated rats (Sham-OP) during LPS-induced shock (Fig. 2A). On the other hand, the amounts of G-CSF and VEGF were inducible by LPS, whereas no differences were observed in dependency of the pituitary gland (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, the concentrations of the pleiotropic hormone Leptin were 7-fold reduced in hypophysectomized rats (Fig. 2A, upper right graph). This observation is reconciled by reports that have identified normal pituitary cells (i.e. outside of fat tissues) as a source of Leptin [14].

Fig. 2.

Influence of the pituitary gland on the release of growth factors and chemokines during endotoxic shock. Long Evans rats after hypophysectomy (Hypo-X; n = 8) or sham surgery (Sham-OP; n = 9) were challenged with LPS (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.) and untreated healthy rats (Sham; n = 5) served as additional controls for baseline mediator levels. (A) The growth factors IL-2, G-CSF, GM-CSF, VEGF and Leptin were detected 6 h after LPS injections in EDTA plasma by multiplexed bead-based assays. (B) The chemokines MIP-1, MCP-1, Eotaxin, IP-10 and RANTES were evaluated 6 h after LPS injections in EDTA plasma by multiplexed bead-based assays (Luminex-200). Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

The concentrations of the C-C motif chemokine, MIP-1α were also reduced in endotoxemic Hypo-X rats as compared to endotoxemic Sham-OP rats (Fig. 2B). In contrast, the C-C motif chemokines, MCP-1 and Eotaxin were positively affected by removal of the hypophysis (Fig. 2B). The C-X-C motif chemokines, IP-10 and the C-C motif chemokine RANTES were not significantly altered, altogether indicating that the effects of the pituitary gland on chemokines can be quite diverse and independent of their structural categorization.

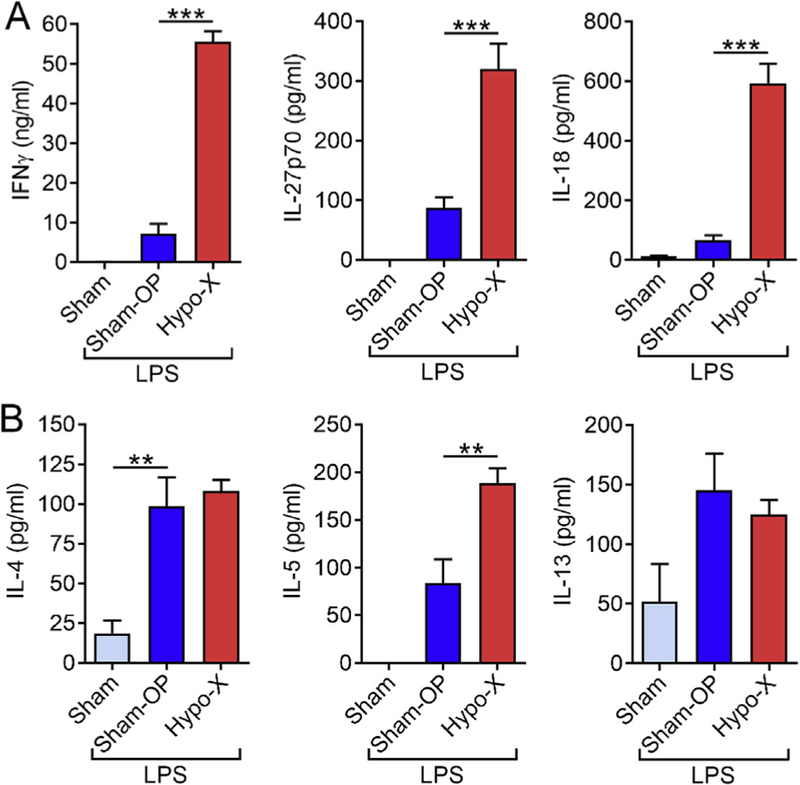

3.4. Preference of the pituitary gland for confining Th1 cytokines versus Th2 cytokines

Interferon-γ (IFNγ) is a mainly pro-inflammatory mediator and Th1 signature cytokine. IFNγ was found to be abundantly present (55 ± 7.1 ng/ml) and 8-fold up-regulated in hypophysectomized rats over controls during endotoxic shock (Fig. 3A). The IFNγ-inducing Th1 cytokines, IL-12p70 (4-fold) and IL-18 (9-fold) were also substantially higher after removal of the pituitary gland followed by systemic LPS challenge (Fig. 3A). In contrast, the absolute amounts of Th2 cytokines in plasma such as IL-4, IL-5 and IL13 were much lower during endotoxemia (Fig. 3B). While IL-4 and IL-13 were not affected by removal of the pituitary gland, only a moderate 2-fold increase of IL-5 was noted (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Th1 and Th2 cytokine release during endotoxic shock in dependency of the pituitary gland. Long Evans rats underwent hypophysectomy (Hypo-X; n = 8) or sham surgery (Sham-OP; n = 9). Both groups received injections with LPS (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.), while untreated healthy rats (Sham; n = 5) were used as negative controls. (A) The Th1 cytokines IFNγ, IL-12 and IL-18 were measured 6 h after LPS in EDTA plasma by multiplex bead-based assays. (B) The Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 were determined after 6 h by multiplexed bead-based assays (Luminex-200). Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

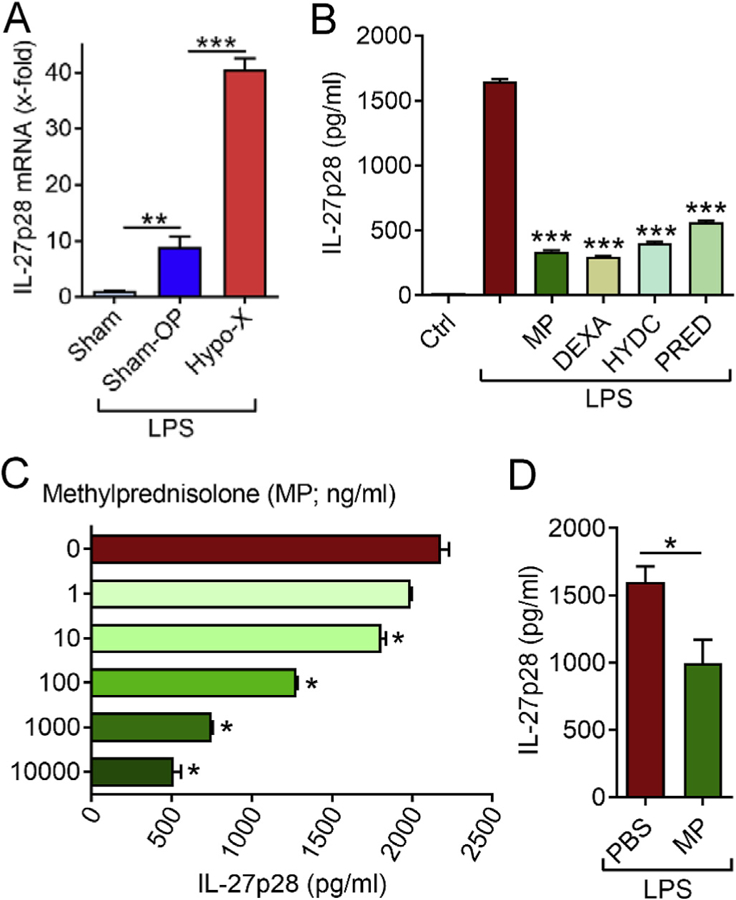

3.5. Gene expression of IL-27p28 is controlled by the pituitary gland and glucocorticoids

Finally, we turned our attention to IL-27, which has been a focus of interest to our laboratory in the past [6,13,15–17]. IL-27 (p28/ EBI3) is a macrophage-derived, heterodimeric cytokine of the IL-6/ IL-12 cytokine family with immune-regulatory functions [17]. In the absence of specific and reliable rat immunoassays, we studied gene expression of mRNA for p28 of IL-27 in spleen tissue of rats by qPCR. We have reported before that macrophages in spleen are the major source of IL-27p28 in mice after endotoxic shock [6]. In fact, IL-27p28 mRNA was 10-fold up-regulated in cranial Sham-OP rats after LPS i.p. as compared to healthy untreated rats (Fig. 4A). Moreover, hypophysectomy resulted in even much higher IL-27p28 gene expression after 6 h (Fig. 4A), when spleen tissue was isolated from the same rats as data shown in Figs. 1B–3. A potential regulation of IL-27 by the pituitary-adrenal-glucocorticoid axis has not been studied before. To test the hypothesis if increased IL-27p28 gene expression is related to the deficiency in cortisol release after hypophysectomy (Fig. 1B), we sought to incubate macrophages with LPS in combination with glucocorticoids. To allow a specific immunoassay detection of IL-27p28 protein, we used macrophages from C57BL/6J mice. A pre-treatment with high-doses of methylprednisolone, dexamethasone, hydrocortisone or prednisone consistently diminished the release of IL-27p28 from LPS-activated macrophages (Fig. 4B). In dose-response studies, lower doses (<100 ng/ml) of methylprednisolone showed less inhibitory effects (Fig. 4C). Finally, we tested the responsiveness of IL-27p28 gene expression in live C57BL/6J mice, when pre-treated with an injection of methyplprednisolone followed by LPS i.p. and collection of plasma. Methylprednisolone significantly suppressed the release of IL-27p28. This observation would be consistent with the concept that the pituitary gland (via ACTH release) controls endogenous glucocorticoid release (Fig. 1B), and glucocorticoids limit the gene expression of IL-27p28 and multiple other mediators in endotoxin-induced shock.

Fig. 4.

Regulation of IL-27p28 by the pituitary gland and glucocorticoids. (A) The spleens were isolated for qPCR of IL-27p28 mRNA from Long Evans rats 6 h after LPS (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.) of the groups hypophysectomy (Hypo-X; n = 8), sham surgery (Sham-OP; n = 9) or healthy controls (Sham; n = 5; no LPS). (B) Macrophages (C57BL6/J derived PEM) were pre-treated for 2 h with methylprednisolone (MP; 1 μg/ ml), dexamethasone (DEXA; 1 μg/ml), hydrocortisone (HYDC; 1 μg/ml) or prednisone (PRED; 1 μg/ml) followed by addition of LPS (1 μg/ml). After 8 h the supernatants were collected and IL-27p28 quantified by ELISA. Untreated macrophages (Ctrl) and macrophages with LPS alone were used as controls. (C) Macrophages (C57BL6/J derived BMDM) were pre-incubated for 4 h with increasing doses of methylprednisolone (MP; 0–10,000 ng/ml) before addition of LPS (1 μg/ml) and detection of IL-27p28 after 12 h. (D) IL-27p28 in plasma of C57BL/6J mice after 2 h of pre-treatment with methylprednisolone (n = 5; 200 μg/mouse i.p.) or saline (n = 3; PBS i.p.) followed by LPS injection (10 mg/kg body weight i.p.) and blood collection after 6 h, ELISA. Error bars represent SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

For the first time, our study has characterized how the presence of multiple inflammatory mediators is dependent on the pituitary gland during endotoxemia. Our data that hypophysectomy in rats greatly increases the susceptibility and mortality during LPS-induced shock is consistent with previous findings in hypophysectomized or adrenalectomized mice [8,18,19]. The pituitary gland in rats is required for conferring protection against the lethal sequelae during gram-negative infection with Salmonella typhimurium [20]. This higher susceptibility of hypophysectomized rats to Salmonella typhimurium was attributed to a lower bactericidal activity of macrophages and was rescued by recombinant IFNγ [20].

The massive amplification of pro-inflammatory cytokine release such as IL-1β, TNFα and IL-6 provides an explanation for decreased survival associated with hypophysectomy (Fig. 1A and C). TNFα was 19-fold higher than in Sham-OP mice (Fig. 1C), while anti-TNFα antibody blockade is known to protect against shock-associated lethality [21]. In clinical studies, anti-TNFα strategies have not been successful presumably because much of the TNFα release has already occurred within the first few hours before diagnosis is established and treatment can be initiated [22,23]. On the other hand, one report has also described that macrophages of rats after hypophysectomy produce less TNFa after LPS in vitro [24], which is in contrast to our findings.

We also observed much higher LPS-induced IL-10 plasma concentrations in the absence of pituitary glands, which is believed to partially counteract and limit the detrimental effects of the amplified pro-inflammatory cytokines. In fact, IL-10 protects mice from endotoxin mediated lethality [25]. Furthermore, a pituitary-derived cytokine, MIF, is secreted by anterior pituitary cells and enhances lethality during endotoxic shock [26]. MIF deficiency as a consequence of hypophysectomy could be another mechanism poised to ameliorate the detrimental effects of exuberant pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The only two mediators negatively affected by hypophysectomy were MIP-1α and Leptin (Fig. 2). MIP-1α increases the inflammatory response to hemorrhagic shock [27]. Thus, lower levels of MIP-1α may somewhat reduce shock severity. Leptin was initially described as an anti-obesity hormone but also has clear neuroendocrine and immune functions [14]. The pituitary itself may be a source of Leptin [14], which would explain its decline after hypophysectomy (Fig. 2).

Th1 signature cytokines such as IFNγ, IL-12 and IL-18 were substantially increased by pituitary gland removal, while neither the Th2 cytokines, IL-4 and IL-13 were affected during endotoxic shock (Fig. 3).The enhanced levels of Th1 cytokines most likely contribute to higher mortality. For example, IFNγ receptor deficient mice are more resistant to endotoxic shock [28].

Heterodimeric IL-27 (p28/EBI3) is an immune-regulatory cytokine of the IL-6/IL-12 family [17]. Similar to IL-6 and IL-12 in plasma, we have observed an increase in splenic gene expression of IL-27p28 in hypophysectomized rats after LPS injections (Fig. 4A). Unlike for many other inflammatory mediators, it has not been clearly established before if the production of macrophage-derived IL-27 is controlled by glucocorticoids. Our data clearly suggest that pretreatment of cultured macrophages or C57BL/6J mice decreases the release of IL-27p28 in response to LPS. Smaller effects were seen with lower doses (Fig. 4C) or when glucocorticoids were added simultaneously with LPS (data not shown). Altogether, these finding suggest that a disruption of the HPA axis with reduced endogenous cortisol levels is a major mechanism for enhanced IL-27p28 gene expression associated with hypophysectomy and shock. In this context, the chronic reduction of endogenous cortisol may be of some importance as we did not observe acute efficacy of the glucocorticoid antagonist, mifepristone (RU-486) during endotoxic shock in an earlier study [15]. As IL-27 also acts as an inducer of IL-10 from various T cell subsets [17], its down-regulation by glucocorticoids may have mixed results in terms of pro-inflammatory versus anti-inflammatory categories.

In summary, this study reveals that a disruption of the HPA axis during endotoxic shock has more complex and selective effects on inflammatory mediator profiles as previously known. These results may be helpful during further discussions on the usefulness of glucocorticoids to ameliorate the tissue destructive and organ damaging effects of infection-associated inflammation that contribute to the lethality of septic shock.

Acknowledgments

MB thanks Peter A. Ward, Ulrich Walter and Heiko Mühl for constant support and mentorship. We cordially thank Erica Cadigan for secretarial assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01HL141513, 1R01HL139641 to MB), the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (01EO1503 to MB), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO3482/3–1, BO3482/4–1 to MB), a Marie Curie Career Integration Grant of the European Union (Project 334486 to MB) and a Clinical Research Fellowship of the European Hematology Association (to MB). The authors are responsible for the content of this publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Transparency document

Transparency document related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.12.101.

References

- [1].G.B.D.C.o.D. Collaborators, Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016, Lancet 390 (2017) 1151–1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Allegranzi B, Nejad S. Bagheri, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, Pittet D, Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis, Lancet 377 (2011) 228–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Adhikari NK, Fowler RA, Bhagwanjee S, Rubenfeld GD, Critical care and the global burden of critical illness in adults, Lancet 376 (2010) 1339–1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Bosmann M, Ward PA, The inflammatory response in sepsis, Trends Immunol 34 (2013) 129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Takeuchi O, Akira S, Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation, Cell 140 (2010) 805–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Bosmann M, Russkamp NF, Strobl B, Roewe J, Balouzian L, Pache F, Radsak MP, van Rooijen N, Zetoune FS, Sarma JV, Nunez G, Muller M, Murray PJ, Ward PA, Interruption of macrophage-derived IL-27(p28) production by IL-10 during sepsis requires STAT3 but not SOCS3, J. Immunol 193 (2014) 5668–5677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Webster JI, Tonelli L, Sternberg EM, Neuroendocrine regulation of immunity, Annu. Rev. Immunol 20 (2002) 125–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Webster JI, Sternberg EM, Role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, glucocorticoids and glucocorticoid receptors in toxic sequelae of exposure to bacterial and viral products, J. Endocrinol 181 (2004) 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sam S, Corbridge TC, Mokhlesi B, Comellas AP, Molitch ME, Cortisol levels and mortality in severe sepsis, Clin. Endocrinol 60 (2004) 29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Prigent H, Maxime V, Annane D, Clinical review: corticotherapy in sepsis, Crit. Care 8 (2004) 122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Sprung CL, Annane D, Keh D, Moreno R, Singer M, Freivogel K, Weiss YG, Benbenishty J, Kalenka A, Forst H, Laterre PF, Reinhart K, Cuthbertson BH, Payen D, Briegel J, Group CS, Hydrocortisone therapy for patients with septic shock, N. Engl. J. Med 358 (2008) 111–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Saito F, Ohno Y, Morisawa K, Kamakura M, Fukushima A, Taniguchi T, Role of IL-27-producing dendritic [corrected] cells in Th1-immunity polarization in Lewis rats, Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 338 (2005) 1773–1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bosmann M, Haggadone MD, Hemmila MR, Zetoune FS, Sarma JV, Ward PA, Complement activation product C5a is a selective suppressor of TLR4-induced, but not TLR3-induced, production of IL-27(p28) from macrophages, J. Immunol 188 (2012) 5086–5093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Popovic V, Damjanovic S, Dieguez C, Casanueva FF, Leptin and the pituitary, Pituitary 4 (2001) 7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Roewe J, Higer M, Riehl DR, Gericke A, Radsak MP, Bosmann M, Neuroendocrine modulation of IL-27 in macrophages, J. Immunol 199 (2017) 2503–2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Bosmann M, Strobl B, Kichler N, Rigler D, Grailer JJ, Pache F, Murray PJ, Muller M, Ward PA, Tyrosine kinase 2 promotes sepsis-associated lethality by facilitating production of interleukin-27, J. Leukoc. Biol 96 (2014) 123–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Bosmann M, Ward PA, Modulation of inflammation by interleukin-27, J. Leukoc. Biol 94 (2013) 1159–1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Bosmann M, Meta F, Ruemmler R, Haggadone MD, Sarma JV, Zetoune FS, Ward PA, Regulation of IL-17 family members by adrenal hormones during experimental sepsis in mice, Am. J. Pathol 182 (2013) 1124–1130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Silverstein R, Turley BR, Christoffersen CA, Johnson DC, Morrison DC, Hydrazine sulfate protects D-galactosamine-sensitized mice against endotoxin and tumor necrosis factor/cachectin lethality: evidence of a role for the pituitary, J. Exp. Med 173 (1991) 357–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Edwards CK 3rd, Yunger LM, Lorence RM, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, The pituitary gland is required for protection against lethal effects of Salmonella typhimurium, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 88 (1991) 2274–2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tracey KJ, Fong Y, Hesse DG, Manogue KR, Lee AT, Kuo GC, Lowry SF, A Cerami, Anti-cachectin/TNF monoclonal antibodies prevent septic shock during lethal bacteraemia, Nature 330 (1987) 662–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bosmann M, Russkamp NF, Ward PA, Fingerprinting of the TLR4-induced acute inflammatory response, Exp. Mol. Pathol 93 (2012) 319–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Marshall JC, Why have clinical trials in sepsis failed? Trends Mol. Med 20 (2014) 195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Edwards CK 3rd, Lorence RM, Dunham DM, Arkins S, Yunger LM, Greager JA, Walter RJ, Dantzer R, Kelley KW, Hypophysectomy inhibits the synthesis of tumor necrosis factor alpha by rat macrophages: partial restoration by exogenous growth hormone or interferon gamma, Endocrinology 128 (1991) 989, 986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Howard M, Muchamuel T, Andrade S, Menon S, Interleukin 10 protects mice from lethal endotoxemia, J. Exp. Med 177 (1993) 1205–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bernhagen J, Calandra T, Mitchell RA, Martin SB, Tracey KJ, Voelter W, Manogue KR, Cerami A, Bucala R, MIF is a pituitary-derived cytokine that potentiates lethal endotoxaemia, Nature 365 (1993) 756–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hsieh CH, Frink M, Hsieh YC, Kan WH, Hsu JT, Schwacha MG, Choudhry MA, Chaudry IH, The role of MIP-1 alpha in the development of systemic inflammatory response and organ injury following trauma hemorrhage, J. Immunol 181 (2008) 2806–2812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Car BD, Eng VM, Schnyder B, Ozmen L, Huang S, Gallay P, Heumann D, Aguet M, Ryffel B, Interferon gamma receptor deficient mice are resistant to endotoxic shock, J. Exp. Med 179 (1994) 1437–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]