Abstract

Despite recent emphasis on the profound importance of the fetal environment in “programming” postnatal development, measurement of offspring development typically begins after birth. Using a novel coding strategy combining direct fetal observation via ultrasound and actocardiography, we investigated the impact of maternal smoking during pregnancy (MSDP) on fetal neurobehavior; we also investigated links between fetal and infant neurobehavior. Participants were 90 pregnant mothers and their infants (52 MSDP-exposed; 51% minorities; ages 18-40). Fetal neurobehavior at baseline and in response to vibro-acoustic stimulus was assessed via ultrasound and actocardiography at M = 35 weeks gestation and coded via the Fetal Neurobehavioral Assessment System (FENS). After delivery, the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale was administered up to 7 times over the first postnatal month. MSDP was associated with increased fetal activity and fetal limb movements. Fetal activity, complex body movements, and cardiac-somatic coupling were associated with infants’ ability to attend to stimuli and to self-regulate over the first postnatal month. Furthermore, differential associations emerged by MSDP group between fetal activity, complex body movements, quality of movement, and coupling and infant attention and self-regulation. The present study adds to a growing literature establishing the validity of fetal neurobehavioral measures in elucidating fetal programming pathways.

Keywords: pregnancy, smoking, maternal, cigarette, fetus, infant, behavior, stress, attention

Maternal smoking during pregnancy (MSDP) remains an intractable public health problem. Despite pervasive medical and societal sanctions against smoking during pregnancy, 10 to 30% of women continue to smoke in the US (Curtin & Matthews, 2016; Tong et al., 2013; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Although national health statistics show rates of 10% based on maternal/birth certificate reports, studies involving biochemical verification and those conducted in poor, young, and less-educated populations reveal rates as high as 25-30% (Bardy et al., 1993; Dietz et al., 2011; Mathews, 2001; Tong et al., 2015). Although rates of spontaneous quitting are increasing, approximately 50% of pregnant smokers continue to smoke into the last trimester (Ockene et al., 2002; Pirie, Lando, Curry, McBride, & Grothaus, 2000; Tong et al., 2013). Further, new and emerging tobacco products including electronic cigarettes and hookah are proliferating among youth and reproductive age women with potential to increase rates of infants born exposed to nicotine/tobacco (England et al., 2016; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; Villanti, Cobb, Cohn, Williams, & Rath, 2015).

MSDP is associated with numerous adverse offspring outcomes. In particular, evidence in support of associations between MSDP and neonatal morbidity and mortality is so strong as to be considered causal by the 2014 Surgeon General’s Report (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Infants exposed to MSDP are at more than double the risk for low birthweight, show an average 200 gram reduction in continuous birth weight, and have 2-4× increased rates of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), the leading cause of death in the first year (Dietz et al., 2010; MacDorman, Cnattingius, Hoffman, Kramer, & Haglund, 1997; Martin et al., 2007; Polakowski, Akinbami, & Mendola, 2009). In addition, suggestive associations have also been shown between MSDP and long-term neurobehavioral deficits in children—particularly, disruptive behaviors/conduct disorder, attention deficits/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and risk for smoking/nicotine dependence (Gaysina et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2018; Ruisch, Dietrich, Glennon, Buitelaar, & Hoekstra, 2018; Shenassa, Papandonatos, Rogers, & Buka, 2015; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Effects of MSDP on long-term neurobehavioral outcomes were initially demonstrated in large birth cohort studies that did not include adequate measures of exposure, maternal factors, context, or offspring phenotypes leaving questions of causality unresolved. Because MSDP cannot be randomly assigned, the field then incorporated genetically-informative designs (e.g., discordant sibling pairs) to address familial confounding. Findings have been inconsistent. Studies using genetically informative designs revealed attenuated or no effects on long-term neurobehavioral outcomes; however, measures of exposure and offspring phenotype were limited (D’Onofrio et al., 2010; Ellingson, Goodnight, Van Hulle, Waldman, & D’Onofrio, 2014; Estabrook et al., 2016; Skoglund, Chen, D’Onofrio, Lichtenstein, & Larsson, 2014). Mechanistic studies with detailed measures of exposure and animal models where exposure is randomly assigned revealed more consistent effects of prenatal nicotine/tobacco on offspring neurobehavior (Estabrook et al., 2016; Hall et al., 2016; Harrod, Lacy, & Morgan, 2012; Wakschlag, Pickett, Cook, Benowitz, & Leventhal, 2002).

Prospective, developmentally sensitive studies are needed with rigorous measures of exposure and context, and coherent measures of behavior and regulation in infancy to delineate early pathways that may cascade to long-term deficits from MSDP (Estabrook et al., 2016; Wakschlag, Leventhal, Pine, Pickett, & Carter, 2006). Our group conducted some of the first studies of associations between MSDP and infant neurobehavior using the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS, behavior exam designed to be sensitive to subtle deficits in substance-exposed infants) and rigorous measures of MSDP including prospective measures of timing, quantity, and biomarkers of exposure (Law et al., 2003; L. Stroud et al., 2009; Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Stroud, Papandonatos, Salisbury, et al., 2016; L. R. Stroud, R. L. Paster, M. S. Goodwin, et al., 2009). We found decreased ability to self-regulate reactions to environmental stimuli (self-regulation/need for external handling), decreased ability to attend to stimuli (attention), and altered motor activity (lethargy) in MSDP-exposed vs. comparison infants (Law et al., 2003; Stroud, Papandonatos, Salisbury, et al., 2016; Stroud, Paster, Papandonatos, et al., 2009). Additional studies have found increased odds of MSDP exposure in NNNS profiles characterized by altered arousal, activity, muscle tone, attention, and signs of stress (Appleton et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2010). Our group also found altered cortisol stress response in MSDP-exposed infants, suggestive of altered biological response to daily stressors (Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014). Studies by other research groups and utilizing alternative neurobehavioral exams have also supported effects of MSDP on infant neurobehavior and cortisol (Eiden et al., 2015; Espy, Fang, Johnson, Stopp, & Wiebe, 2011; Schuetze, Lopez, Granger, & Eiden, 2008; Stroud, Paster, Goodwin, et al., 2009; Yolton et al., 2009). Over the last two decades, a large body of human and animal research has highlighted the profound importance of the fetal environment in “programming” a host of postnatal neurobehavioral and medical outcomes (Alexander, Dasinger, & Intapad, 2015; Barker, 2002; Moisiadis & Matthews, 2014; Xiong & Zhang, 2013). Changes to fetal physiological stress systems are believed to help the infant adapt in the short-term to a stressful postnatal environment, but may predispose offspring to disease over the long-run (Cao-Lei et al., 2017; Maccari et al., 2003; Meaney, Szyf, & Seckl, 2007; Seckl, 1998). For example, our group has shown the importance of programming of biological stress pathways in short and long-term effects of MSDP (Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Stroud, Papandonatos, Shenassa, et al., 2014)

However, despite emphasis on the critical importance of the fetal period in programming of long-term disease and disorders, measurement of offspring behavior in studies of MSDP and other prenatal insults typically begins after birth. Yet, “the explosive rate of growth and development that occurs during the period before birth is unparalleled at any other point in the lifespan. In just 266 days, a single fertilized cell develops into a sentient human newborn infant” (J. DiPietro, 2010). Further, “there is no other period in development in which the proximal environment is so physiologically entangled” with the offspring (J. A. DiPietro, Costigan, & Voegtline, 2015). Ongoing improvements in ultrasound technology and fetal monitoring have allowed understanding of fetal development to progress from delineating structural and organ development to assessing patterns of fetal movements and fetal heart rate (FHR) to elucidating fetal state and neurobehavior (J. A. DiPietro et al., 2010; Groome, Bentz, & Singh, 1995; Nijhuis, Martin, & Prechtl, 1984; Nijhuis, Prechtl, Martin, & Bots, 1982). Fetal neurobehavioral assessment has been defined as comprising four domains: FHR, motor behavior and activity level, behavioral state, and responsiveness to environmental stimuli (J DiPietro, 2001; J. A. DiPietro et al., 2010). Assessment of these domains across gestation is believed to provide information about central nervous system (CNS) function and development (J. A. DiPietro, Bornstein, et al., 2002; Nijhuis, 1986b; Prechtl, 1977). Early in pregnancy, fetal movements appear to be random and uncoordinated (Nasello-Paterson, Natale, & Connors, 1988). As pregnancy advances, fetal movements become increasingly smooth, coordinated, and organized with lengthening and regular periods of rest (quiescence) that lead to observable rest-activity cycles by 28 weeks gestational age (Pillai & James, 1990; Pillai, James, & Parker, 1992; Robertson, Dierker, Sorokin, & Rosen, 1982). As gestation advances, more mature behavioral states can be observed (de Vries, Visser, & Prechtl, 1985, 1988; J. A. DiPietro, Costigan, & Pressman, 2002; Groome et al., 1999). Fetal behavioral states are typically defined by the co-occurrence of somatic movements, eye movements, and specific FHR patterns, and are evident by 32 weeks (Arabin & Riedewald, 1992). Cardiac-somatic coupling--defined as state-independent temporal associations between FHR and fetal movements--also increases over gestation (J DiPietro, 2001; J. A. DiPietro, Hodgson, Costigan, Hilton, & Johnson, 1996).

Characterization of fetal behavior utilizing the four domains has been validated through studies showing continuity over gestation, cross-domain associations, and continuity with postnatal behavior (J. A. DiPietro, Bornstein, et al., 2002; J. A. DiPietro et al., 2010; Gingras & O’Donnell, 1998; Salisbury, Fallone, & Lester, 2005). Specifically, a growing number of studies have shown links between fetal and infant neurobehavior. For example, fetal activity levels are correlated with infant motor activity (J. A. DiPietro et al., 2010) and a higher incidence of fetal cardiac-somatic coupling has been associated with better newborn state regulation and brain auditory evoked potentials (J. A. DiPietro, Bornstein, et al., 2002; J. A. DiPietro et al., 2010), There is evidence of continuity between individual fetal behaviors such as mouthing, yawning, and hand-to-face movements and similar behaviors in newborns (Kurjak et al., 2004). Our group has also demonstrated links between summary measures of fetal neurobehavior and summary measures of infant neurobehavior, as indicated on the NNNS, including links between fetal quality of movement and newborn self-regulation and excitability (subscales of the NNNS; Salisbury et al., 2005). In older infants, DiPietro et al. (2000) showed continuity between third trimester FHR and both infant HR and infant HR variability at 1 year. Fetal movements were also found to predict infant temperament at 2 years of age (J. A. DiPietro, Bornstein, et al., 2002; J. A. DiPietro et al., 1996).

Behavioral continuity from the pre to postnatal period extends to deviations from typical fetal behavior; deviations in the presence, absence, and patterning of behaviors predict newborn compromise. For example, the absence of fetal breathing movements and rhythmic mouthing movements while in a quiescent state predicted compromised newborn outcomes (Nijhuis, 1986a; Pillai & James, 1990, 1991; Pillai et al., 1992). Fetal neurobehavioral patterns distinguish high risk fetuses, including fetuses with CNS deficits, intrauterine growth restriction, fetuses born pre-term, and fetuses exposed to maternal medical conditions (e.g., diabetes, pre-eclampsia; Andonotopo & Kurjak, 2006; J DiPietro, 2001; Kainer, Prechtl, Engele, & Einspieler, 1997; Kisilevsky, Gilmour, Stutzman, Hains, & Brown, 2012; Kiuchi, Nagata, Ikeno, & Terakawa, 2000; Lumbers, Yu, & Crawford, 2003; Pillai et al., 1992; Salisbury, Ponder, Padbury, & Lester, 2009).

Despite important potential for characterizing markers of risk prior to birth and continuity with infant neurobehavior, only a small number of studies have investigated effects of MSDP exposure on fetal neurobehavior. Initial studies focused on acute fetal responses to smoking. These studies showed decreases in felt movements, fetal FHR, and FHR variability and reactivity following acute exposure to smoking (Goodman, Visser, & Dawes, 1984; Graca, Cardoso, Clode, & Calhaz-Jorge, 1991; Lehtovirta, Forss, Rauramo, & Kariniemi, 1983; Thaler, Goodman, & Dawes, 1980). Fetuses also showed greater rates of maladaptive response to the “non-stress test”, a clinical test of fetal well-being (Phelan, 1980) after acute exposure to maternal smoking. In a study by Oncken et al., prior to maternal smoking, 80% of fetuses were reactive to the non-stress test (indicative of fetal well-being); after mothers smoked, only 27% of fetuses were reactive (2002). More recent studies revealed preliminary evidence for chronic dysregulation of fetal behavior in MSDP-exposed fetuses. Zeskind and Gingras showed lower FHR variability and altered autonomic regulation in MSDP-exposed fetuses (2006). Fetal responsiveness to stimuli (stress response) is a key domain of fetal neurobehavior. Fetal stress response is typically elicited by means of a vibro-acoustic stimulus (VAS; a vibratory and acoustic stimulus applied to the maternal abdomen) shown to consistently differentiate healthy and at-risk fetuses (Kisilevsky, Muir, & Low, 1990, 1992; Smith, 1994; Smith, Phelan, Broussard, & Paul, 1988). In a study of behavioral habituation to repeated VAS, Gingras et al. (1998) showed reduced habituation in MSDP-exposed vs. cocaine-exposed and comparison fetuses. Cowperthwaite et al. (2007) further demonstrated altered FHR response to maternal voice recognition in early but not late third trimester MSDP-exposed fetuses.

Salisbury and colleagues developed the Fetal Neurobehavioral Coding System (FENS) to synthesize real-time ultrasound with fetal actocardiography monitoring to characterize fetal neurobehavior and stress response (Grant-Beuttler et al., 2011; Salisbury, 2010; Salisbury et al., 2005). The FENS builds upon prior work involving a single measurement system for physiology or behavioral observation or only components of both, to incorporating observational data from real-time ultrasound on a full repertoire of fetal behaviors with simultaneous measurement of FHR and fetal activity (FA) data from fetal actocardiography. The FENS was designed as a standardized assessment to reveal deficits in high-risk (exposed to maternal medical and psychiatric illness) and substance-exposed fetuses (Salisbury, 2010; Salisbury et al., 2005; Salisbury et al., 2009). Standardized neurobehavioral assessments during gestation and after birth allow for a comprehensive and “seamless” assessment of fetal to infant development in healthy and at-risk infants.

The standardized observation and measurement of neurobehavior from the fetal period through later developmental periods is captured through a lens informed by the conceptual framework of developmental systems theory which posits that development is dependent upon the mutual influences within the maternal-fetal system. (Bertalanffy, 1968; Gottleib, 1991) This includes all levels of shared biology and experience, not simply the shared genetic encoding of proteins, or the impact of maternal biology on the fetus, but also the mother’s experience and responses to the physiology and behaviors of the fetus (Denenberg, 1980; Lecanuet, Fifer, Krasenegor, & Smotherman, 1995). Examining the neurobehavioral system while it is evolving is an opportunity to determine the factors or processes that are most likely to alter developmental trajectories. For example, fetal responses to mild stimuli test the ability of the fetal sensory systems to detect and attend to the stimulus, as well as the physiological and behavioral responses to the demands of the stimulus. Measurement of responses over time reflects fetal attention and arousal system function and maturation, systems that are central to all developmental processes (Krasnegor et al., 1998).

MSDP is just one of many potential influences on this developing system. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the impact of MSDP on comprehensive measures of fetal neurobehavior utilizing the FENS. The FENS was administered in the context of a prospective longitudinal study of MSDP and neonatal neurobehavioral development. Fetal neurobehavior was assessed via ultrasound and actocardiography between 32 and 37 weeks gestation. After delivery, the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale was administered 7 times over the first postnatal month. Thus, the first goal of the present study was to investigate the influence of MSDP on fetal neurobehavior measured by the FENS. Our second goal was to explore links between fetal neurobehavior and evolution of neonatal neurobehavior over the first postnatal month and to investigate potential interactions between MSDP and fetal neurobehavior in predicting neonatal neurodevelopment. Our overarching hypothesis was that fetal behavior and responses to a sensory stimulus, reflecting attention and arousal systems, would be altered by MSDP and be predictive of infant neurobehavioral development over the first postnatal month.

METHOD

Participants

The Behavior and Mood in Babies and Mothers (BAM BAM) study was an intensive, short-term, prospective study of MSDP and fetal and neonatal neurobehavior. Participants were English-speaking, primarily low-income, and racially and ethnically diverse pregnant mothers and their infants recruited from obstetrical offices, health centers, and community postings in southern New England (Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Stroud, Papandonatos, Salisbury, et al., 2016). Pregnant women were enrolled if they were ages 18-40, had no current/prior involvement with child protective services prior to birth, had no illicit drug use besides marijuana (meconium confirmed), or serious medical conditions (e.g., pre-eclampsia, severe obesity). Infants were healthy singletons born >36 weeks gestational age (GA) with no congenital anomalies or serious medical complications. All participants provided written informed consent; all procedures were reviewed and approved by Institutional Review Boards at Women and Infants’ Hospital of Rhode Island and Lifespan Hospitals.

One hundred forty-eight pregnant women aged 18-40 were originally enrolled in the study. Of these, 6 were excluded for regular opiate or cocaine use/positive meconium, 2 for current or prior involvement with child protective services, 5 for serious maternal medical conditions (3 for pre-eclampsia, 1 for severe obesity [BMI=61], 1 for blood clotting disorder), and 6 for delivery <36 weeks. Thirty-nine participants who did not have fetal ultrasound or neonatal neurobehavioral data were also excluded from analyses.

The final analytic sample (n=90) included 52 smokers and 38 biochemically-verified controls. Participants were assigned to the smoking or control group based on maternal report of cigarette use and/or positive cotinine bioassay of maternal saliva (≥10 ng/mL) or meconium nicotine markers (≥10 ng/g).

Procedures

Maternal interviews.

Mothers were interviewed 2-4 times (M = 3.6) over second and third trimesters of pregnancy and at delivery (between 24 and 42 weeks gestation). At each interview, mothers completed the calendar/anchor-based Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) interview regarding cigarette, drug, and alcohol use over pregnancy and three months prior to conception (Robinson, Sobell, Sobell, & Leo, 2014), and a socioeconomic status (SES) interview from which education, occupation, income, and Hollingshead four-factor index of SES were extracted (Gottfried, 1985). Caffeine consumption and hours of environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure were assessed using detailed interviews covering each trimester. Mothers were also interviewed regarding their health and pregnancy history and symptoms of depression (Hamilton, 1960). Maternal saliva for cotinine for verification of smoking status was collected at each interview. Maternal weight was measured in late third trimester (M = 35 weeks).

Delivery.

Information regarding maternal and infant health and medical conditions was extracted by medical chart review. Mothers and study staff collected diapers containing meconium for 3 days post-birth to verify maternal report of MSDP and other drug use.

Fetal Neurobehavioral Assessment.

Fetal behavior and heart rate were obtained using the Fetal Neurobehavioral Coding System (FENS; Salisbury et al., 2005) between 32 and 37 weeks gestational age (M = 35.1, SD = 1.1). There were no differences in gestational age at the ultrasound assessment between smokers and controls (p=ns; Table 1). Ultrasounds were conducted between the hours of 8:00 am and 3:00 pm to account for possible variability in fetal activity levels at different times of the day (Pillai et al., 1992). Participants were asked to fast for 1.5 hours before their scheduled appointment and were given a small meal, standardized for calories and content upon arrival to their appointment.

Table 1.

Maternal and infant characteristics by smoking group and full sample

| Smokers (n=52) | Controls (n=38) | Total (n=90) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)/ % | Mean (SD)/ % | Mean (SD)/ % | |

| Maternal Characteristics | |||

| Maternal age (years) | 24 (4) | 25 (5) | 24 (5) |

| Race/Ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White) | 54% | 42% | 49% |

| Low SES1 | 48% | 19% | 36%** |

| Parity | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Weight gain (pounds)2 | 28 (18) | 31 (17) | 30 (17) |

| Marijuana Use (>1 joint/week or meconium)3 | 4% | 0% | 2% |

| ETS Exposure (hours per week)4 | 22 (27) | 1 (3) | 13 (23) |

| Caffeine Use (>200 mg/day caffeine)5 | 33% | 3% | 20%*** |

| Gestational Medical Condition6 | 17% | 8% | 13% |

| Maternal Depressive Symptoms7 | 5 (6) | 2 (3) | 4 (5)** |

| Gestational Age at Ultrasound (wks) | 35 (1) | 35 (1) | 35 (1) |

| Cigarettes per day8 | 7 (5) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) |

| Maternal saliva cotinine (ng/mL)9 | 93 (105) | 0 (0) | 54 (93) |

| Infant Characteristics | |||

| Sex (% male) | 48% | 63% | 54% |

| Delivery Mode (% vaginal delivery) | 77% | 76% | 77% |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 40 (1) | 40 (1) | 40 (1) |

| Small for gestational age10 | 6% | 0% | 3% |

| Apgar score, 5 minutes | 9 (0.3) | 9 (0.4) | 9 (0.3) |

| Any breast-feeding | 50% | 74% | 60%* |

| ETS Exposure: saliva cotinine (ng/ml)11 | 11 (20) | 1 (2) | 7 (16)** |

NOTE:

p<.05;

p<.01

p<.001.

Based on a score of 4 or 5 on the Hollingshead Index.

Weight gain in pounds between pre-pregnancy and 35±1 weeks.

>1 joint per week or meconium positive for marijuana metabolites.

Hours of ETS exposure per week measured by structured interview.

Equivalent of 2 cups of coffee per day.

e.g., gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes.

Score on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (scores of 0-7 indicate no depression; scores ≥ 8 indicate depressive symptomatology).

Mean cigarettes per day across pregnancy.

Average cotinine level over 3rd trimester.

Birthweight <10th percentile for gestational age.

Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS) exposure measured by infant saliva cotinine (ng/ml)

Women reclined in a semi-recumbent position, in a quiet, darkened room. A 10-minute FHR recording was obtained prior to placement of the ultrasound transducer to ensure limited mechanical interference during baseline FHR assessment. FHR accelerations from baseline during fetal movement, fetal breathing, tone and activity, and amniotic fluid index, are used to obtain a standard Biophysical Profile (BPP) (Manning, Platt, & Sipos, 1980; Manning et al., 1993) and non-Stress test of general fetal health following the guidelines of National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development Workshop Report on Electronic Fetal Monitoring (Macones, Hankins, Spong, Hauth, & Moore, 2008). FENS data were collected by the last author (AS) or a research nurse, both of whom were certified in limited obstetrical ultrasound. Simultaneous measurements of fetal behavior and heart rate were obtained throughout a 40-minute baseline period. A single, 3-second single vibroacoustic stimulus (VAS) (Toitu) was applied to the maternal abdomen during the first period of fetal quiescence accompanied by a non-acceleratory but moderately variable FHR pattern (indicative of active sleep) following the 40-minute baseline period. If the FHR pattern showed low variability indicative of quiet sleep or accelerations as observed during arousals in active sleep or wake, the VAS stimulus was not delivered until a stable baseline FHR was obtained for one minute. Recording continued for 20 minutes post VAS presentation. Additionally, a VAS-stimulus control trial was conducted in the baseline period to control for maternal reaction to the VAS.

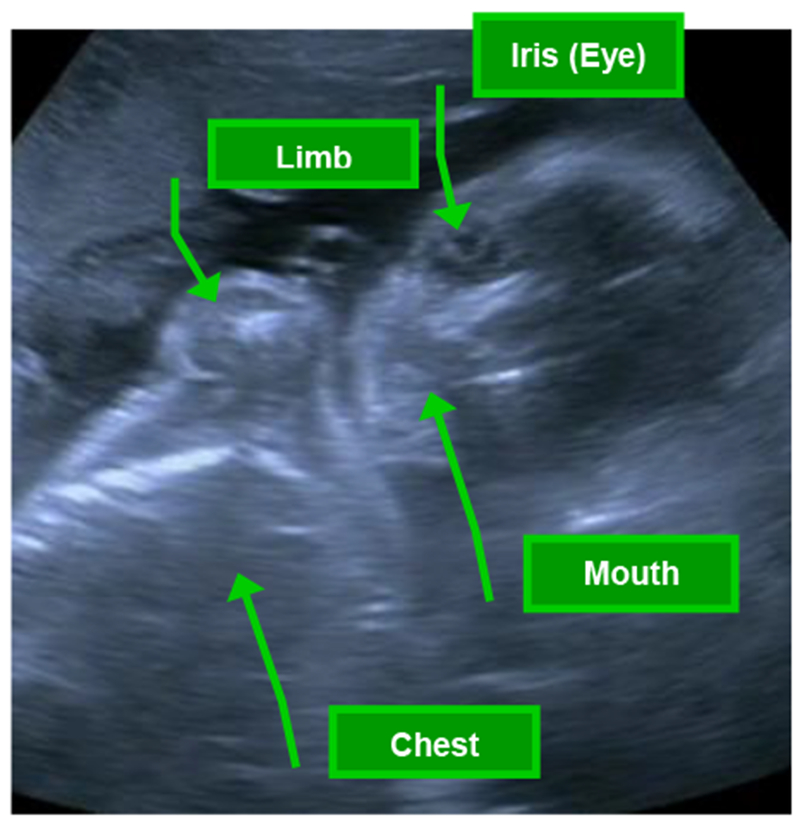

Fetal behaviors were observed using real-time ultrasound (Toshiba diagnostic ultrasound machine, model SSA-340A, Toshiba American Medical, Duluth, GA) with a single 3.50-MHz transducer focused on a longitudinal view of the fetal head, trunk, and upper limbs. Figure 1 highlights the ideal image of the fetus for behavior coding, in which coders have a clear view of fetal head, eye, mouth, and at least one limb, optimizing visualization of fetal body parts involved in the core fetal behaviors coded within the FENS. Ultrasound video was recorded to a media file for later coding of fetal behavior. The ultrasound transducer was removed from the maternal abdomen every seven minutes to minimize continuous ultrasound exposure and to allow for three minutes of FHR monitoring without the second transducer to control for potential signal interference. FHR and movement actograph data were obtained using a Toitu MT325 (company) fetal actocardiograph machine with a wide array trans-abdominal Doppler transducer. The resulting signals were processed through autocorrelation techniques. This monitor has been used extensively and demonstrates high accuracy in the detection of fetal movement compared to ultrasound visualized movements (J. A. DiPietro, Costigan, & Pressman, 1999; Maeda, Tatsumura, & Nakajima, 1991).

Figure 1.

Ideal view of fetus from ultrasound for fetal neurobehavioral coding system (FENS) assessment, in which coders have a clear view of fetal head, eye, mouth, and at least one limb, optimizing visualization of fetal body parts involved in the core coded fetal behaviors.

Infant neurobehavior over the first postnatal month.

The NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS) (B. Lester & E. Tronick, 2004) was utilized to assess infant neurobehavior over the first month and administered by certified examiners blind to MSDP status. The NNNS is a comprehensive assessment of neurobehavioral performance designed to reveal subtle differences in substance-exposed infants (Coyle et al., 2012; Law et al., 2003). The NNNS begins with a pre-examination observation, followed by neurologic and behavioral components (B. M. Lester & E. Z. Tronick, 2004). The exam includes exposure to auditory, visual, social and non-social stimuli and lasts approximately 30 minutes and involves mild stress as the infant is observed and handled during periods of sleep, awake, crying, and non-crying states. Subscales of focus for the present study include: Attention (orientation to animate and inanimate auditory and visual stimuli), Handling (need for external soothing of the infant to maintain a quiet alert state), Lethargy (measure of low levels of motor state and physiologic reactivity), Self-Regulation (ability to self-sooth; measures the infant’s capacity to organize activity, physiology, and state and to respond to positive and negative stimuli), and Quality of Movement (higher scores reflect more mature movement patterns with relatively more smooth vs jerky movements, fewer startles and tremors, and moderate levels of activity and quiescence). The NNNS was administered up to 7 times (M = 6) over the first postnatal month at days 0 (M = 8 hours), 1, 2, 3-4, 5, 11, and 32. Saliva samples were collected at the time of the NNNS and assayed for cotinine to determine infant exposure to nicotine via ETS and/or breast milk.

Fetal Neurobehavioral (FENS) Coding.

The Fetal Neurobehavioral Coding System (Salisbury et al., 2005) incorporates definitions for fetal behaviors following DeVries et al. (de Vries, Visser, & Prechtl, 1982) and stress signs derived from the NNNS (Lester et al., 2004). The presence of specific fetal behaviors was coded from the recorded ultrasound media files using the Mangold INTERACT coding program (Mangold International Inc., Atlanta, GA) by individuals who were certified on the FENS coding system and blinded to the fetus’ MSDP group status. FENS coding is conducted by viewing the recorded ultrasound video to identify the presence of individual fetal behaviors (defined in Table 2) in continuous 10-second epochs. These included: Fetal Breathing Movements (regular and vigorous), hiccups, Mouthing Movements (rhythmic as in sucking, or non-rhythmic as in drinking or general opening/closing), yawning, Isolated Movements (IM) of the head (general, extension, and rotation) and limbs (upper and lower extremities), Complex Body Movements (CBM; including coordinated general body movements and patterned body movements of stretch and backarche), quiescence (absence of spontaneous movements), startles, tremors, and the jerky or smooth quality of observed limb and general body movements. These composite variables, expressed as the total number per minute of the recording, were chosen for analyses as these reduced variables reflect CNS maturation while minimizing the number of variables to be tested. For example, fetal breathing and mouthing movements increase in frequency over gestation and are thought to be preparatory for the transition to the neonatal period when coordination of both breathing and mouthing movements will be required for feeding (Grant-Beuttler et al., 2011). As detailed in Table 2, Fetal Quality of Movement (FQM) is a summary score measuring the relative amount of fetal smooth to jerky movements, startles, tremors, fetal quiescence, and activity which collectively reflect the developmental processes of organized rest-activity patterns and motor control (Pillai & James, 1990; Robertson et al., 1982). FQM is based on the NNNS summary score for neonatal quality of movement (B. Lester & E. Tronick, 2004; B. M. Lester & E. Z. Tronick, 2004). Inter-rater reliability of all fetal behavior coding was assessed by comparing scores of at least 2 coders by intraclass correlations (ICC, type 3) on a randomly selected list of fetuses (10% of coded recordings were dual scored). ICC’s of .76 - .97 were obtained for the individually coded items.

Table 2.

Descriptions of behaviors coded from ultrasound recordings and the derived composite variables

| Composite Variable | Category of Observation | Observed Behavior | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chest Movements | Hiccup | Consists of a jerky, repetitive contraction of the diaphragm (not included in summary variable). | |

| Breathing Movements | Regular | Displacement of the diaphragm with movement of the abdomen; rhythmic or non-rhythmic. | |

| Vigorous | FBM’s that are large enough to move the entire fetus’ body. | ||

| Mouth Movements | Yawning | The timing of a yawn is similar to a stretch that includes prolonged wide opening of the jaws followed by relaxation; often accompanied by a stretch or a subsequent GBM. | |

| Mouthing Movements | Rhythmic | Rhythmical bursts of jaw opening and closing at least 4 times in 10 seconds (sucking). | |

| NonRhythmic | Mouth opening and closing that is isolated or limited to less than 4 at one time, often with tongue protrusion or lapping (drinking). | ||

| Isolated Movements (IM) | Head Movements | Rotation | Movement of the head in the lateral plane for at least at least a 30 degree angle from starting position. |

| Extension | A small head movement that extends upward in the vertical plane. | ||

| Isolated | Small movement of the head that is not an extension or rotation. | ||

| Limb Movements | Smooth | Movement of an upper or lower extremity that is generally fluid. | |

| Jerky | Movement of an upper or lower extremity that is generally forceful and/or abrupt in nature. | ||

| Indeterminate | Lower limb (occasionally upper limb) movement that is suggested by shift in fetal position but cannot be directly observed. | ||

| Hand to Face | The hand slowly touches the face or mouth. | ||

| Tremor | Small rhythmic, jerky movement of an extremity (or chin). | ||

| Fidgeting | Nearly continuous, repetitive and jerky limb movements that are not part of a GBM or other patterned movement. | ||

| Complex Body Movements (CBM) | General Body Movements (GBM) | Smooth | Simultaneous and coordinated movement of 1+ limbs, trunk and head that is fluid and smooth and results in a change of position. |

| Jerky | Simultaneous and coordinated movement of 1+ limbs, trunk and head that involves jerky movements of limbs or entire body. | ||

| Incomplete | Simultaneous movement of head, trunk and limbs that is not fluid or coordinated and does not result in change in position | ||

| Patterned Body Movements | Stretch | A single event including a back extension or upward movement of the shoulder with retroflexion of the head; typically includes a pause at the peak of the movement with subsequent relaxation. | |

| Backarche | Extension of trunk and maintenance in this position for > 1 second. | ||

| Startle | A quick, generalized movement, involving abduction or extension of the limbs with or without movement of the trunk and head, followed by a return to a resting position. | ||

| Other | Quiescence | Absence of all body movements other than FBM or mouthing. | |

| Fetal Quality of Movement (FQM) | A mean summary score of overall movement quality (1-5 scale) derived from scored frequencies of 5 categories of coded behaviors; highest scores indicate overall rest-activity balance, maturity of smooth movements, and absence of startles and tremors. | ||

| FQM-Quiescence | 1-5 score; median %ile score=5, while lowest and highest % = 1. | ||

| FQM-Fetal Movement | 1-5 score; median %ile score=5, while lowest and highest % = 1. | ||

| FQM-Jerky Movements | 1-5 score; Lowest %=5, Median %=3, Highest=1. | ||

| FQM-Tremors | 1-5 score; Lowest %=5, Median %=3, Highest=1. | ||

| FQM-Startles | 1–5 score; Lowest %=5, Median %=3, Highest=1. | ||

NOTE: Observed fetal behaviors that are bolded comprise the associated composite variable.

Fetal Actocardiograph measures; The raw heart rate and activity data (5 samples/second) were examined with artifact rejection algorithms and processed into mean FHR per second of the recording before and after the VAS (J. A. DiPietro et al., 1999; J. A. DiPietro et al., 1996). Fetal movement amplitude from the actocardiograph is calculated by obtaining the square of the amplitude for each sample in which there was movement. The result is then averaged over each second of the file and is a weighted measure of Fetal Activity, in which the seconds of activity that have more samples with higher amplitude have the highest activity level compared to those with only a few samples or with low amplitude measures. The temporal coupling of FHR accelerations with FA bouts (Cardiac-Somatic Coupling) was defined as a FHR excursion (> 5 bpm change) −5 to +15 seconds from the start of a fetal movement. Coupling was summarized as ratio of coupled movements to total movement bouts over baseline and post-VAS observation (J. A. DiPietro et al., 1999; J. A. DiPietro et al., 1996).

Bioassays

Saliva cotinine.

Mother and infant saliva samples were frozen until analysis of cotinine (biomarker for nicotine levels) (Jarvis, Tunstall-Pedoe, Feyerabend, Vesey, & Saloojee, 1987) by Salimetrics LLC using highly-sensitive enzyme immunoassay (HS EIA) with intra and inter-assay coefficients of variation of 6.4% and 6.6%.

Meconium.

Meconium was analyzed for nicotine and cannabinoid markers, opiates, cocaine, and amphetamines via EMIT screens, tandem liquid chromatography mass spectrometry or gas chromatography mass spectroscopy confirmation. Samples from all participants in the final sample were negative for cocaine, opiates, and amphetamines. Based on precedent in the field and sensitivity of the assays, samples with nicotine or cannabinoid markers ≥10 ng/g were considered positive for nicotine and cannabinoids, respectively (Gray et al., 2009).

Potential Confounders

Maternal demographic information: age, race/ethnicity (% Non-Hispanic White), Hollingshead SES (low SES ≥ 4), weight gain over pregnancy (pre-pregnancy to 35±1 weeks); and pregnancy history: gravida and parity, were assessed by maternal report. Maternal medical conditions, e.g., gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes and medications: steroids, antidepressants were assessed by maternal report and medical chart review. Maternal depression was assessed through the 21-item clinician-administered Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton, 1960). Maternal alcohol use was assessed through TLFB interview (Robinson et al., 2014); maternal cannabis use was assessed by TLFB interview and/or meconium. Maternal caffeine use and environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) exposure were assessed by structured interview; infant ETS exposure was assessed by infant saliva cotinine levels. Neonatal characteristics: sex, delivery mode, Apgar, GA at birth, small for GA (SGA; birth weight <10th percentile for GA) were assessed by medical chart review.

Statistical analysis

Two-sample t-, and Chi-square tests were utilized to assess associations of MSDP group with potential confounders (Table 1). A Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) approach was utilized to estimate and test parameters for fetal and infant outcome measures (Tables 2 and 3). GEE is an extremely flexible statistical approach that accounts for correlated repeated measures and allows for inferential analyses for continuous, Poisson and binomial outcomes, and allows for missing data on the outcome measures (Shults et al., 2009; Zeger & Liang, 1986). All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.0 software. To investigate the impact of MSDP on fetal outcomes, MSDP group served as the independent variable; FENS composite variables served as outcome variables in addition to fetal activity and cardiac-somatic coupling from the actocardiograph, with baseline and post-VAS as repeated measures. Potential confounders showing significant associations with MSDP as well as gestational age at the time of the fetal observation session were tested in relation to fetal outcomes. Maternal depression was significantly associated with the majority of fetal outcomes and was thus included in the corresponding GEE models (Table 3). To investigate links between fetal neurobehavior and infant outcomes (NNNS attention, lethargy, handling, self-regulation, and quality of movement over the first postnatal month) in relation to MSDP group, we conducted a series of GEE models with the three composite fetal variables that represent baseline fetal somatic movements (isolated movements, complex body movements, quality of movement) as well as the actocardiographic variables (fetal activity and coupling) at baseline and MSDP as between subjects’ factors and infant age in days at each NNNS exam as the time scale for measuring neurobehavior over the first postnatal month. Potential confounders showing significant associations with MSDP were tested in relation to infant outcomes. Maternal depression was significantly associated with the majority of NNNS outcomes and was thus included in all GEE models. Infant second-hand smoke exposure (ETS) was significantly associated with NNNS attention, handling, and lethargy, and thus included in these GEE models; maternal caffeine use in pregnancy was related to NNNS lethargy and quality of movement and thus included in these GEE models; socioeconomic status was related to handling, self-regulation, and quality of movement and thus included in these GEE models (Table 4).

Table 3.

Effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy on indices of fetal neurobehavior.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fetal Outcome | Source | X2 | Sig. | X2 | Sig. |

| Breathing Movements | Maternal Smoking | 1.80 | 0.180 | 0.97 | 0.325 |

| Stimulus | 0.30 | 0.584 | 0.07 | 0.787 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.01 | 0.940 | 0.00 | 0.997 | |

| Mouthing Movements | Maternal Smoking | 3.43 | 0.064 | 0.62 | 0.430 |

| Stimulus | 0.55 | 0.460 | 0.04 | 0.847 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 1.30 | 0.254 | 0.14 | 0.711 | |

| Isolated Movements | Maternal Smoking | 3.82 | 0.051 | 0.61 | 0.433 |

| Stimulus | 9.79 | 0.002 | 8.87 | 0.003 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.13 | 0.720 | 0.21 | 0.651 | |

| Complex Body Movements | Maternal Smoking | 2.02 | 0.155 | 1.89 | 0.169 |

| Stimulus | 0.13 | 0.714 | 0.29 | 0.590 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.19 | 0.664 | 0.08 | 0.775 | |

| Fetal Quality of Movement | Maternal Smoking | 2.68 | 0.101 | 4.68 | 0.598 |

| Stimulus | 2.15 | 0.142 | 0.87 | 0.112 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.03 | 0.869 | 0.17 | 0.652 | |

| Fetal Activity | Maternal Smoking | 9.63 | 0.002 | 3.80 | 0.051 |

| Stimulus | 3.94 | 0.047 | 4.03 | 0.045 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.20 | 0.652 | 0.15 | 0.697 | |

| Fetal Cardiac-Somatic Coupling | Maternal Smoking | 1.01 | 0.316 | 0.09 | 0.762 |

| Stimulus | 0.02 | 0.885 | 0.06 | 0.803 | |

| Maternal Smoking*Stimulus | 0.24 | 0.625 | 0.10 | 0.748 | |

NOTE: Statistically significant effects and trends are highlighted in bold. Maternal depression severity was included as a covariate in all adjusted models; significant relationships emerged between maternal depression and fetal mouthing movements (X2=10.45, p<.001), isolated movements (X2=4.41, p<.03) and fetal quality of movement (X2=9.7, p<.002).

Table 4.

Fetal neurobehavior and maternal smoking in relation to infant neurobehavior over the first postnatal month, measured by the NICU Network Neurobehavioral Scale (NNNS).

| ATTENTION | HANDLING | LETHARGY | REGULATION | QUALITY OF MOVEMENT | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P | B | SE | P |

| Fetal Isolated Movements | −0.101 | 0.155 | 0.514 | 0.009 | 0.012 | 0.462 | 0.259 | 0.163 | 0.114 | −0.067 | 0.067 | 0.317 | 0.065 | 0.0274 | 0.017 |

| Maternal Smoking | −0.531 | 0.649 | 0.413 | 0.015 | 0.057 | 0.793 | 0.630 | 0.849 | 0.457 | −0.101 | 0.278 | 0.717 | 0.179 | 0.1541 | 0.245 |

| Infant Age | 0.146 | 0.024 | 0.000 | −0.010 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.186 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.057 | 0.0076 | 0.000 |

| Maternal Depression | −0.052 | 0.024 | 0.032 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.854 | 0.087 | 0.040 | 0.030 | −0.005 | 0.009 | 0.569 | 0.000 | 0.0073 | 0.996 |

| Fetal IM*M-Smoking | 0.371 | 0.232 | 0.109 | −0.028 | 0.020 | 0.172 | −0.471 | 0.264 | 0.074 | 0.109 | 0.103 | 0.290 | −0.014 | 0.0388 | 0.726 |

| Fetal Complex Movements | 0.172 | 0.254 | 0.499 | 0.077 | 0.035 | 0.030 | −0.733 | 0.752 | 0.330 | −0.232 | 0.200 | 0.246 | 0.084 | 0.1887 | 0.657 |

| Maternal Smoking | 0.584 | 0.334 | 0.081 | −0.048 | 0.029 | 0.094 | −0.402 | 0.442 | 0.362 | 0.272 | 0.119 | 0.022 | 0.165 | 0.1024 | 0.107 |

| Infant Age | 0.138 | 0.025 | 0.000 | −0.010 | 0.003 | 0.002 | −0.186 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.056 | 0.0077 | 0.000 |

| Maternal Depression | −0.050 | 0.024 | 0.036 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.838 | 0.093 | 0.039 | 0.018 | −0.007 | 0.009 | 0.427 | 0.005 | 0.0074 | 0.538 |

| Fetal CBM*M-Smoking | −1.125 | 1.135 | 0.322 | −0.040 | 0.178 | 0.823 | −1.446 | 1.323 | 0.274 | −0.972 | 0.410 | 0.018 | −0.264 | 0.4602 | 0.567 |

| Fetal Quality of Movement | 0.061 | 0.305 | 0.842 | −0.001 | 0.034 | 0.986 | −0.281 | 0.390 | 0.471 | 0.064 | 0.141 | 0.647 | −0.216 | 0.1225 | 0.078 |

| Maternal Smoking | 4.620 | 1.793 | 0.010 | −0.158 | 0.281 | 0.574 | −6.468 | 2.029 | 0.001 | 0.393 | 0.862 | 0.649 | −1.393 | 0.6517 | 0.033 |

| Maternal Depression | −0.048 | 0.024 | 0.050 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.631 | 0.083 | 0.040 | 0.040 | −0.003 | 0.009 | 0.787 | 0.055 | 0.0074 | 0.000 |

| Infant Age | 0.135 | 0.024 | 0.000 | −0.009 | 0.003 | 0.005 | −0.186 | 0.029 | 0.000 | 0.073 | 0.012 | 0.000 | −0.001 | 0.0078 | 0.941 |

| FQM *M-Smoking | −0.997 | 0.436 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.068 | 0.639 | 1.406 | 0.489 | 0.004 | −0.049 | 0.208 | 0.815 | 0.366 | 0.1523 | 0.016 |

| Fetal Activity | −0.001 | 0.000 | 0.030 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.057 |

| Maternal Smoking | 0.783 | 0.231 | 0.001 | −0.061 | 0.027 | 0.025 | −0.439 | 0.309 | 0.155 | 0.210 | 0.121 | 0.084 | 0.250 | 0.103 | 0.015 |

| Infant Age | 0.162 | 0.021 | 0.000 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.187 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.074 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.057 | 0.007 | 0.000 |

| Maternal Depression | −0.039 | 0.020 | 0.056 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.645 | 0.109 | 0.031 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 0.978 | 0.003 | 0.009 | 0.733 |

| Fetal Activity*M-Smoking | −0.001 | 0.001 | 0.037 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.774 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.457 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.043 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.222 |

| Fetal Coupling Index | 1.169 | 0.561 | 0.037 | −0.240 | 0.075 | 0.001 | −1.336 | 0.750 | 0.075 | 0.551 | 0.311 | 0.076 | −0.571 | 0.1887 | 0.002 |

| Maternal Smoking | −0.185 | 0.610 | 0.761 | −0.175 | 0.065 | 0.007 | 0.069 | 0.795 | 0.931 | 0.256 | 0.281 | 0.363 | −0.213 | 0.1782 | 0.231 |

| Maternal Depression | −0.061 | 0.019 | 0.002 | −0.002 | 0.003 | 0.507 | 0.139 | 0.031 | 0.000 | −0.007 | 0.010 | 0.502 | 0.057 | 0.0071 | 0.000 |

| Infant Age | 0.160 | 0.022 | 0.000 | −0.011 | 0.003 | 0.001 | −0.184 | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.075 | 0.011 | 0.000 | 0.008 | 0.0083 | 0.343 |

| Fetal Coupling*M-Smoking | 1.246 | 1.025 | 0.224 | 0.230 | 0.104 | 0.027 | −0.634 | 1.274 | 0.619 | −0.126 | 0.485 | 0.795 | 0.698 | 0.3172 | 0.028 |

NOTE: P values highlighted in red, bold indicate statistically significant main or interactive effects of fetal neurobehavior and/or maternal smoking. P values highlighted in black bold indicate statistically significant effects of covariates. Models represent Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) parameters for models predicting infant neurobehavior over the first postnatal month from fetal neurobehavioral scales and maternal smoking group. Infant second-hand smoke exposure (ETS) was included as a covariate in the Attention, Handling, Lethargy, and Quality of Movement models; maternal caffeine use was included in the Lethargy model. NNNS Attention is a measure of orientation to animate and inanimate auditory and visual stimuli. NNNS Handling is a measure of need for intervention from the NNNS examiner to soothe the infant and assist the infant in maintaining a quiet, alert state. NNNS Lethargy is a measure of infant lethargic behavior or low levels of motor, state and physiologic reactivity. NNNS Self-Regulation measures the infant’s capacity to organize activity, physiology, and state and response to positive and negative stimuli. NNNS Quality of Movement is a measure of maturity of movement patterns, relative proportion of smooth versus jerky movements, startles and tremors, and levels of activity and quiescence. Maternal Smoking=maternal smoking during pregnancy group. Infant Age: modeled in postnatal days. Maternal Depression=score on 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale.

RESULTS

Sample characteristics

The sample included 90 mothers (mean age 24, SD = 5) and their healthy infant offspring (46% female). The sample was racially/ethnically diverse (51% minorities: 18% African American, 20% Hispanic and 13% Multiracial/Other; 49% Non-Hispanic White) and skewed toward low socioeconomic status (58% had household annual income <$30,000; 53% had a high school education or less). Pregnant smokers reported smoking a mean of 7 ± 5 cigarettes per day across pregnancy, with average cigarettes per day of 10 ± 7, 6 ± 5, and 5 ± 5 over first, second, and third trimesters. Mean saliva cotinine levels over pregnancy ranged from 61-113 ng/ml (SD’s = 69-127). Descriptive statistics for the overall sample and stratified by MSDP group are presented in Table 1. Pregnant smokers were more likely to be low socio-economic status (48% vs. 19%, p < .01), report high caffeine use (>200 mg/day; 33% vs. 3%, p < .001), and reported higher depressive symptoms relative to controls (5 vs 2 symptoms; p = .001), although levels of depressive symptoms for both groups were in the normative (non-depressed) range (Zimmerman, Martinez, Young, Chelminski, & Dalrymple, 2013). MSDP-exposed infants were less likely to be breast-fed (50% vs. 74%, p < .05) and had higher saliva cotinine levels (M ‘s = 11 vs. 1 ng/ml, p < .01).

Associations between maternal smoking group and fetal neurobehavioral scales

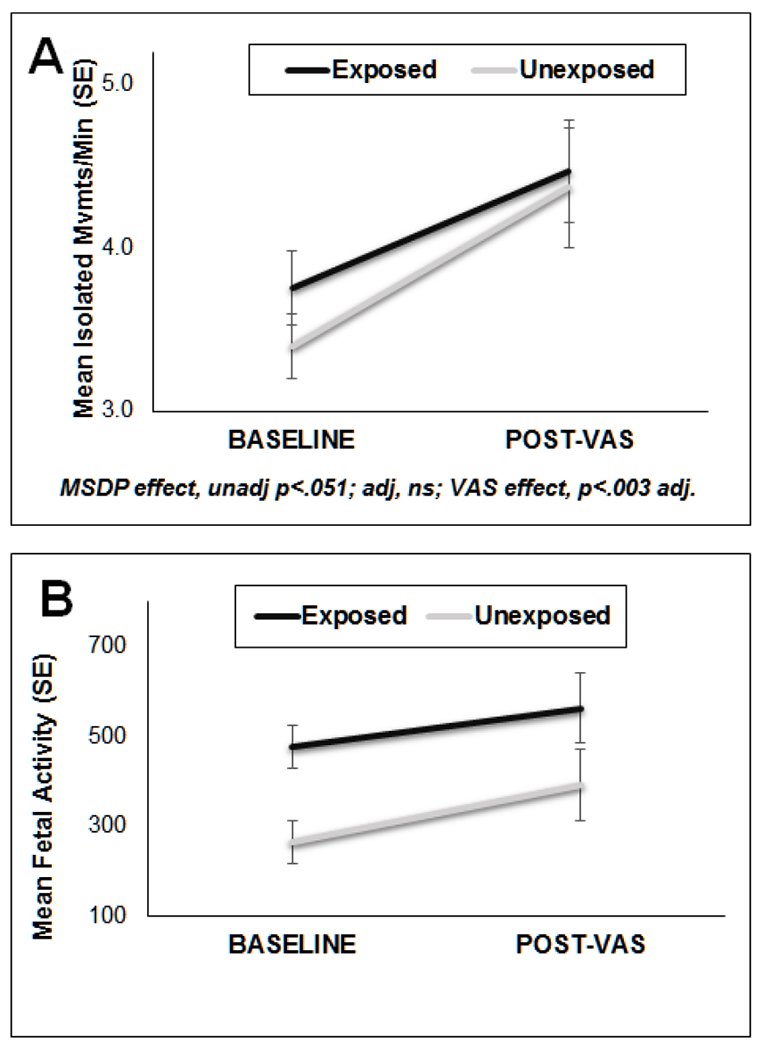

Associations between MSDP and fetal neurobehavioral scales measured at baseline and in response to a vibroacoustic stimulus (VAS) are presented in Table 3. As shown in Figures 2A and 2b, we found main effects of MSDP group and VAS versus baseline. Fetuses in the MSDP group showed more IMs (unadjusted p = .051) and increased fetal activity (unadjusted p = .0002; adjusted p = .051). We also found significant increases in both fetal IMs and fetal activity in response to the VAS relative to baseline (ps < .05); however, there were no significant differences in response to the VAS by smoking group. No significant associations between MSDP and fetal breathing or mouthing movements, CBMs, FQM, or fetal cardiac-somatic coupling emerged, nor were there significant changes in fetal CBMs, FQM, or coupling in response to the VAS.

Figure 2.

Effects of maternal smoking during pregnancy (exposed vs unexposed) on (A) fetal isolated movements, and (B) fetal activity.

NOTE: Although isolated movements and fetal activity increased following the VAS, there were no smoking group by time interactions. VAS=Vibro-acoustic stimulus. MSDP=Maternal Smoking During Pregnancy.

Associations between fetal and infant neurobehavior in relation to maternal smoking

Associations between the fetal neurobehavioral scales and infant neurobehavioral development (indexed by NNNS Lethargy, Attention, Handling, Self-Regulation, and Quality of Movement over the first postnatal month) in relation to MSDP group are presented in Table 4.

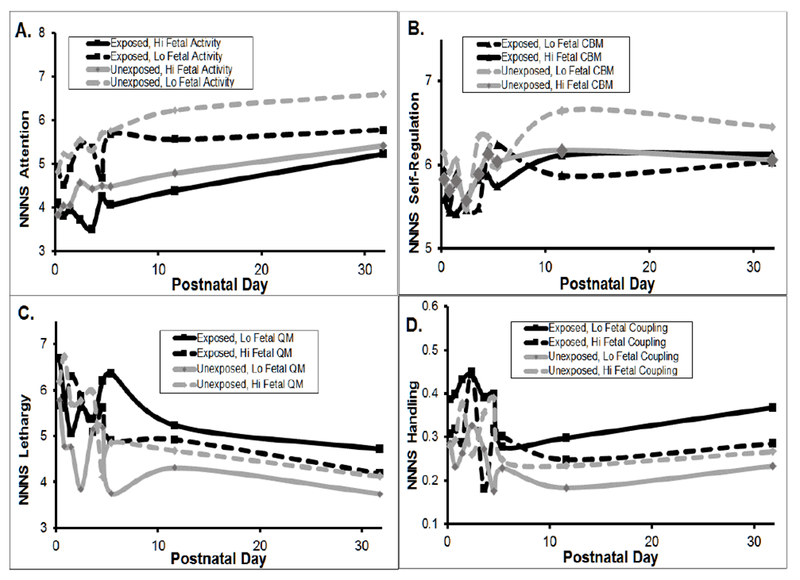

Higher amounts of fetal activity were significantly associated with very small but statistically significant decreases in infant attention and self-regulation and increases in lethargy and handling scores over the first postnatal month (ps ≤ .03). Higher fetal activity was associated with lower attention and self-regulation in the unexposed infants relative to the MSDP-exposed infants. Newborn attention was chosen to graphically depict these associations over age, plotted by MSDP-exposure group and stratified by high versus low fetal activity (divided at the 60th percentile) in Figure 3A; which demonstrates that newborns with high fetal activity showed worse attention scores, with a more pronounced impact for unexposed infants.

Figure 3.

Associations between fetal neurobehavioral indices and infant neurobehavioral scales over the first postnatal month in relation to maternal smoking group: (a) Fetal Activity and NNNS Attention, (b) Fetal Complex Body Movements (CBMs) and NNNS Self-Regulation, (c) Fetal Quality of Movement (QM) and NNNS Lethargy, (d) Fetal Cardiac-Somatic Coupling and NNNS Handling.

NOTE: The NNNS was administered up to 7 times over the first postnatal month at days 0 (M = 8 hours), 1, 2, 3-4, 5, 11, and 32. Fetal activity, CBMs, FQM, and coupling were modeled continuously but are presented by Hi and Lo based on the 60th percentile split for ease of visual display.

More fetal IMs was associated with higher newborn quality of movement scores overall. More fetal CBMs were significantly related to increased handling scores over the first postnatal month (p < .03). More fetal CBMs were associated with lower newborn self-regulation scores in the unexposed infants relative to the MSDP-exposed infants (p < .018), Associations between fetal CBMs (represented as low versus high CBMs, divided at the 60th percentile) and infant self-regulation over the first postnatal month are shown in Figure 3B for MSDP-exposed and unexposed groups.

There were significant maternal smoking group by FQM associations with newborn attention, lethargy, and quality of movement scores (ps ≤ .02). Higher FQM scores were associated with lower attention scores in the unexposed group, relative to the exposed group, and higher newborn quality of movement and lethargy scores. The impact of high versus low FQM on newborn lethargy scores by MSDP-exposure group are depicted in Figure 3C; this figure demonstrates that lower FQM (drawn in the solid lines) was associated with increased lethargy in the MSDP-exposed group, but lower lethargy scores in the unexposed group.

Higher rates of fetal coupling were significantly associated with higher newborn attention, decreased need for handling, and lower quality of movement overall (ps ≤ .04). However, there were differences in these relationships between MSDP-groups. Higher rates of fetal coupling were associated with higher newborn quality of movement and higher handling scores in the unexposed relative to the exposed infants (ps<.03). The associations between fetal coupling and newborn handling are complex and are therefore represented in Figure 3D, dichotomized by high versus low coupling. Specifically, low fetal coupling (solid lines) was associated with increased need for external handling in the MSDP-exposed but not the unexposed infants.

Maternal depression severity was related to the NNNS attention and lethargy scores across multiple fetal neurobehavior models (ps ≤ .05); increased maternal depression was associated with diminished attention and higher lethargy over the first postnatal month.

DISCUSSION

Exposure to MSDP is one of the most common prenatal insults in the world, with suggestive links to long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes including disruptive behaviors and attention deficits (Levin & Slotkin, 1998; Slotkin, 1998; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2014). Developmentally sensitive studies of behavior and regulation in infancy have begun to delineate early pathways that may cascade to long-term deficits from MSDP. However, although fetal programming has been posited as a key mechanism underlying effects of multiple prenatal exposures including MSDP on offspring development, measurement of offspring development typically begins after birth. In the present study, we found associations between MSDP and neurobehavior measured in the fetus as well as longitudinal pathways linking fetal and infant neurobehavior in relation to MSDP. Results add to the growing literature highlighting the value and promise of direct measures of fetal neurobehavior for elucidating bidirectional relationships between maternal exposures and offspring development.

A notable innovation in the present study is our measurement of fetal neurobehavior using both ultrasonography and actocardiography, followed by a novel fetal neurobehavioral coding strategy incorporating both ultrasound images and fetal heart rate and activity. Utilizing the fetal neurobehavioral assessment system (FENS), we found that MSDP-exposed fetuses were more active and that this activity was more likely to be smaller, isolated head and limb movements (versus complex body movements; CBMs) relative to unexposed fetuses. Increases in activity and isolated movements between exposed and unexposed fetuses suggest differences in CNS maturation or differences in overall fetal state and rest-activity patterns related to maternal smoking exposure. Increases in isolated movements could limit the experience of the fetus to the full repertoire of coordinated movement patterns. From a developmental systems perspective (Bertalanffy, 1968; Gottleib, 1991), these fetuses may have lower spatial summation of sensory and motor experiences, which may have downstream effects on later development (Neil, Chee-Ruiter, Scheier, Lewkowicz, & Shimojo, 2006). Increases in fetal activity are also consistent with prior studies showing increased arousal and activity in MSDP-exposed newborns (Law et al., 2003). Effects of maternal smoking on indices of FENS fetal behavior add to a growing body of literature highlighting the promise of fetal behavioral assessment for revealing pre-birth markers of risk from prenatal exposures. Although we found overall increases in activity in response to the vibro-acoustic stimulus (VAS), MSDP group did not differentially influence response to the VAS. Lack of differential response to the VAS by MSDP group was corroborated by one prior small study of prenatal smoking (n = 22) vs cocaine-exposed (n = 12) vs comparison (n = 32) fetuses, which showed no impact of maternal smoking on initial blink-startle response to the VAS, although a trend toward decreased behavioral habituation to repeated VAS testing in smoking-exposed fetuses emerged (Gingras & O’Donnell, 1998).

Our focus on fetal neurobehavior has been guided by a developmental cascades framework. This framework suggests that alterations in one system, domain or level at an early time point may spread to other systems, domains and levels over time, leading to compounding or attenuating risk and consequences(Davies, Manning, & Cicchetti, 2013; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Lester et al. propose that the impact of prenatal substance exposure on child neurobehavior may include both direct effects of prenatal exposure on child neurobehavior (behavioral teratology model) and indirect effects via impact of exposure on early behavioral mediators (mediator/developmental processes model (Lester et al., 2009)). Investigating effects of prenatal substance exposure, Lester et al. found (a) indirect effects in which prenatal substance use altered newborn neurobehavior (NNNS performance at one month) leading to altered neurobehavior at 4 months, leading to altered neurobehavior at 3 years then 7 years, and (b) direct effects of prenatal exposure on age 7 neurobehavior. Indirect effects remained significant after controlling for direct effects (Lester et al., 2009). Subtle alterations in fetal and newborn neurobehavior may, over time, and in the context of stressed and vulnerable families, lead to alterations in early neurobehavioral phenotypes leading to alterations in long-term outcomes. Conversely, identification of subtle alterations in fetal and newborn neurobehavior may allow targeted early interventions to reverse an insidious developmental cascade leading to more salutary outcomes.

Detailed characterization of the maternal phenotype is another strength of the study. MSDP was measured prospectively with biochemical verification, (non)use of illicit drugs was also biochemically confirmed, key covariates were measured by interview and medical chart review. An additional strength is the primarily low-income, racially/ethnically diverse sample. Similar to our prior studies of infant neurobehavior, effects of MSDP on fetal neurobehavior were evident at relatively low average levels of smoking (seven cigarettes per day in the present study), and in the absence of significant differences in birth weight (SGA) between MSDP-exposed and unexposed groups (Law et al., 2003; Stroud, Paster, Papandonatos, et al., 2009). These findings are consistent with animal models, which have revealed that in contrast to non-specific prenatal insults, which are brain-sparing at the expense of somatic growth, prenatal nicotine exposure specifically targets the central nervous system even at relatively low levels of nicotine exposure and in the absence of effects on somatic growth (Slotkin, 1998, 2004; Slotkin, Southard, Adam, Cousins, & Seidler, 2004; Slotkin, Tate, Cousins, & Seidler, 2002). In particular, prenatal nicotine and prenatal tobacco smoke exposure have been shown to disrupt nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and cell-signaling pathways in the brain, and lead to neurobehavioral outcomes that mimic known outcomes from MSDP, including altered motor activity (Hall et al., 2016; Levin & Slotkin, 1998; Slotkin, 1998).

Highlighting the predictive validity of the FENS coding system, we found significant associations between fetal behavioral scales and infant neurobehavior over the first postnatal month. Increased fetal activity was significantly associated with decreased infant attention, decreased self-regulation, increased lethargy and a higher need for handling over the first postnatal month. Attention scores on the NNNS indicate the ability to attend to social and non-social, auditory and visual stimuli. Self-regulation scores measure abilities and difficulties in maintaining a quiet awake state throughout the NNNS examination and in self-soothing during stress (hand to mouth, sucking on hand, or attending to objects around them when fussy or crying with a return to a calm state). Higher lethargy on the NNNS is indicative of more depressed and under-aroused infants. Need for examiner handling indicates the level of support/interventions needed from the NNNS examiner to maintain a quiet alert state throughout the exam (need for examiner soothing). Thus, increased fetal activity was associated with a newborn profile of increased difficulty in self-regulating, under-arousal, and decreased attention over the first postnatal month. Increased fetal CBMs were related to increased need for handling, whereas increased fetal coupling was significantly associated with higher newborn attention and decreased need for handling over the first postnatal month. Associations between fetal activity, movements, and autonomic-movement coupling with indices of postnatal behavioral (dys)regulation highlights the important impact of fetal experience on postnatal neurobehavioral development. Longer term studies are needed to determine pathways linking fetal behavior, newborn behavior and ultimately infant and child neurobehavioral development.

We also demonstrated that MSDP moderated associations between fetal and infant neurobehavior. Specifically, associations between fetal activity and fetal CBMs with infant attention and self-regulation were most pronounced in the unexposed versus the MSDP-exposed group. MSDP-exposed newborns showed decreased self-regulation and attention regardless of fetal activity and CBMs, whereas for unexposed offspring, increased activity and decreased CBMs were associated with improved self-regulation and attention. Diminished associations between fetal and infant neurobehavior in MSDP-exposed infants points to a potentially disruptive impact of prenatal substance exposure on typical developmental trajectories. In contrast, decreased fetal quality of movement and cardiac-somatic coupling showed stronger associations with decreased newborn attention, increased need for examiner handling, and increased lethargy in exposed versus unexposed offspring. These findings suggest that for fetal autonomic dysregulation and fetal quality of motor movement (e.g., smoothness versus jerkiness, coordination), MSDP potentiates the impact of fetal experience and dysregulation on postnatal neurobehavioral development. Results extend prior findings of links between fetal quality of movement (smooth versus jerky behaviors) and newborn self-regulation and excitability measured at 1-2 days post-delivery (subscales of the NNNS; Salisbury et al., 2005). Interactions between maternal behavior (smoking) and fetal behaviors (activity, movement, autonomic regulation) in predicting postnatal neurobehavioral development highlight the complexities and bidirectional nature of maternal and fetal experience in determining pathways to behavioral regulation in infancy.

Given the complexity of these findings, replication in a larger cohort is needed, particularly with respect to interactions between fetal behavior and MSDP. In addition, the present study focused on group differences between MSDP-exposed and unexposed fetuses and infants. However, within the MSDP group, there was high variability in maternal smoking and nicotine levels, highlighting the potential utility of continuous analytic approaches to investigate the quantitative impact of smoking/nicotine on fetal and infant neurobehavior. Future studies within the present cohort and complementary cohorts are needed to investigate dose-response relationships between levels of MSDP/nicotine and offspring outcomes. An additional limitation of the present study was that fetal behavior was measured at one time point over gestation. In ongoing work by our group, we are investigating patterns of fetal behavior across gestation. Indeed, Cowperthwaite et al. found altered fetal heart rate response to maternal voice in smoking-exposed fetuses examined before 37 weeks gestational age, but no differences in fetuses older than 37 weeks gestation (Cowperthwaite et al., 2007). The present study focused on post-birth behavioral development during the first postnatal month only. Also critical for future work in this area is to investigate links between fetal behavior and longer-term infant and child neurobehavioral development. Our study did not include a genetically-sensitive design (e.g. discordant sibling pairs) or molecular genetic measures, although links between MSDP, epigenetic regulation of candidate genes in the placenta, and infant neurobehavioral and neuroendocrine development have been reported in this cohort (Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Stroud, Papandonatos, Salisbury, et al., 2016). Finally, although significant confounders were included in our statistical models, MSDP groups differed in socio-economic status, depressive symptoms, and caffeine use. It remains possible that effects of MSDP on fetal behavior and interactions with MSDP are also related to group differences in these maternal characteristics or other unmeasured confounders.

Based on this preliminary study, we propose a number of future research directions in this area. First, most studies of fetal programming to date have focused on a single exposure (e.g., stress, depression, substance use, environmental toxin). However, prenatal exposures, and indeed, high risk behaviors typically do not occur in isolation (Meader et al., 2016; Noble, Paul, Turon, & Oldmeadow, 2015). For example, in the present study, mothers who smoked during pregnancy also showed higher levels of depression, increased caffeine use and were of lower socio-economic status versus mothers who did not smoke during pregnancy. Mothers who smoke and smoke more have also shown decreased feelings of attachment to their fetuses (Alhusen, Gross, Hayat, Woods, & Sharps, 2012; Lindgren, 2001; Magee et al., 2014). Smoking and nicotine have also been associated with changes in appetite, nutrition, and nutrient absorption, all of which impact the maternal-fetal unit and may also influence fetal and infant neurobehavioral development (Jo, Talmage, & Role, 2002; Slotkin, 1998; Stojakovic, Espinosa, Farhad, & Lutfy, 2017). In larger epidemiologic studies, mothers who smoke during pregnancy are more likely to use other substances such as marijuana and alcohol, to have unplanned pregnancies, and to have increased relationship problems (Pickett, Wilkinson, & Wakschlag, 2009). In the present study, we found independent effects of both maternal smoking and maternal depression on fetal and infant neurobehavior. In a prior, 40-year longitudinal study, we found additive effects of maternal smoking and maternal stress (cortisol levels) on offspring nicotine dependence (Stroud, Papandonatos, Shenassa, et al., 2014). Similarly, Clark et al. found independent effects of prenatal tobacco and prenatal stress in predicting executive control at age five, which along with difficult temperament predicted elevated levels of disruptive behavior (Clark, Espy, & Wakschlag, 2016). Larger samples selected across the continuum of multiple exposures are needed to investigate complex interactions and additive effects of multiple exposures on trajectories of offspring development.

Relatedly, because of the nature of the majority of prenatal exposures, random experiments in humans are not ethical. Prenatal exposures—especially those related to maternal behavior—are necessarily confounded with genetic and personality factors that lead to the maternal behaviors. Thus, novel and genetically-informed designs and statistical approaches as well as translational synthesis across human and animal studies (where random assignment is possible) are needed to infer causality across potential confounds. The field of MSDP has incorporated genetically sensitive designs such as discordant sibling pairs, co-twin control, adoption, and in vitro fertilization, as well as propensity modeling approaches (Bidwell et al., 2016; D’Onofrio, Class, Lahey, & Larsson, 2014; Fang et al., 2010). However, to our knowledge, few studies of maternal prenatal psychopathology and stress have incorporated these approaches. Future studies with novel designs and statistical approaches are needed to improve causal inferences in studies of prenatal programming and child psychopathology.

In addition, the advent of three- and four-dimensional ultrasound technologies allows for increased precision of measurement through synthesis of images in 3 axial planes (3D) and over time (4D) (Bornstein, Monteagudo, Santos, Keeler, & Timor-Tritsch, 2010; Monteagudo & Timor-Tritsch, 2009; Timor-Tritsch & Monteagudo, 2007). It is also possible to measure fetal facial expressions and affect with greatly increased precision (Kurjak et al., 2008). Future studies are needed to harness 3D and 4D ultrasound technology to investigate bidirectional links between maternal environment and fetal neurobehavioral development over gestation and in relation to infant and child development. Also needed are studies to harness emerging fetal electrocardiogram technology to more precisely measure timing and variability in fetal cardiac function at baseline and in response to maternal and fetal stimuli (Graatsma, Jacod, van Egmond, Mulder, & Visser, 2009). Future studies could synthesize novel technologies combined with repeated fetal assessment and longer-term follow up using measures and tasks with developmental coherence between pre and postnatal development. Such studies will allow for a more sophisticated understanding of the impact and mechanistic pathways underlying prenatal perturbations (such as maternal smoking) on the developing maternal-fetal unit and on postnatal child development.

Also critical are studies of the differential impact of prenatal exposures on developmental trajectories of male versus female fetuses. Although sex differences in fetal behavior and autonomic regulation have generally been absent or subtle in prior literature, there is evidence that fetal sex may moderate associations between maternal endocrine function and fetal development and between fetal and infant development (J. A. DiPietro, Costigan, Kivlighan, Chen, & Laudenslager, 2011; Doyle et al., 2015). Sex differences have been documented in human and animal models at multiple steps within fetal programming pathways including maternal-fetal glucocorticoid regulation, placental structure and function, and in offspring neurodevelopmental outcomes following prenatal perturbations (Bale, 2011; J. A. DiPietro et al., 2011; Nugent & Bale, 2015; Rosenfeld, 2015; Sandman, Glynn, & Davis, 2013). Sandman and colleagues have proposed an early-life viability-later-life vulnerabilty trade-off for males and females. While males are at greater risk for mortality and morbidity during the fetal period and in early life following prenatal adversity (viability), females show adaptive flexibility, which allows for increased early survival, but may also lead to vulnerability in later life—with particular risk for a reactive endophenotype linked to risk for mood disorders (Sandman et al., 2013). Although fetal sex was tested as a covariate in the present study, we did not stratify results by sex given the already complex nature of our findings. Studies powered to investigate interactions of exposures, fetal experience and development, and offspring sex are needed to better elucidate sex-specific developmental trajectories leading to known sex differences in child psychopathology.

Another future direction that is already being explored in prenatal programming studies is incorporation of genetic and epigenetic mediators as well as large-scale ‘omics analyses into prospective prenatal exposure cohorts which include rigorous phenotypic measures across development. Our group has begun to investigate epigenetic regulation of candidate stress genes in the placenta as mediators and moderators of effects of prenatal exposures on infant neurodevelopment (Stroud, Papandonatos, Parade, et al., 2016; Stroud, Papandonatos, Rodriguez, et al., 2014; Stroud, Papandonatos, Salisbury, et al., 2016). The placenta controls fetal development and environment through multiple critical functions: (a) mediating nutrient and waste exchange, (b) regulating interaction with the maternal immune system, (c) serving as an endocrine organ producing hormones and growth factors necessary for fetal development, and (d) regulating fetal exposure to intrinsic and exogenous exposures, including tobacco constituents (Banister et al., 2011; Maccani & Marsit, 2009; Novakovic & Saffery, 2012). Because the placenta may both regulate and be regulated by maternal exposures, characterization of epigenetic alterations in the placenta may elucidate mechanisms by which MSDP and other prenatal exposures influence offspring neurobehavior and may also reveal biomarkers of perinatal exposures and future behavioral risk (Hogg, Price, Hanna, & Robinson, 2012; Lester, Conradt, & Marsit, 2014). As prenatal cohort studies move toward large-scale ‘omics analyses, unbiased, big data approaches will need to be balanced with hypothesis-driven, theoretical approaches and rigorous measures of maternal and offspring phenotypes if the field is to move forward to make an impact on child psychopathology and treatment.

Conclusions

We found associations between MSDP and increased fetal behavioral activity, measured via a novel fetal neurobehavioral coding system combining ultrasonography and actocardiography. Further, fetal activity, complex movements, quality of movement and autonomic regulation were significantly associated with newborn neurobehavioral development over the first postnatal month, with evidence for differential associations between fetal and infant neurobehavior by maternal smoking group. Results add to a growing literature highlighting the importance of direct measurement of the fetus in studies of prenatal exposures and prenatal programming. Future studies involving the measurement of fetal behavior throughout critical gestational periods and the careful measurement of multiple prenatal exposures are needed.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DA019558 and R01 DA036999 to L.R.S.) and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Clinical Innovator Award to L.R.S. We gratefully acknowledge the families who contributed to this study and the Maternal-Infant Studies Laboratory staff for their assistance with data collection. We are also grateful to Cheryl Boyce, Nicolette Borek, Program Officers, for their support of this work and this field.

Contributor Information

Laura R. Stroud, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University

Meaghan McCallum, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, Brown University.

Amy Salisbury, Department of Pediatrics, Warren Alpert Medical School, Brown University.

REFERENCES

- Alexander BT, Dasinger JH, & Intapad S (2015). Fetal programming and cardiovascular pathology. Compr Physiol, 5(2), 997–1025. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alhusen JL, Gross D, Hayat MJ, Woods AB, & Sharps PW (2012). The influence of maternal-fetal attachment and health practices on neonatal outcomes in low-income, urban women. Res Nurs Health, 35(2), 112–120. doi: 10.1002/nur.21464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andonotopo W, & Kurjak A (2006). The assessment of fetal behavior of growth restricted fetuses by 4D sonography. J Perinat Med, 34(6), 471–478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appleton AA, Murphy MA, Koestler DC, Lesseur C, Paquette AG, Padbury JF, … Marsit CJ. (2016). Prenatal Programming of Infant Neurobehaviour in a Healthy Population. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 30(4), 367–375. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arabin B, & Riedewald S (1992). An attempt to quantify characteristics of behavioral states. Am J Perinatol, 9(2), 115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bale TL (2011). Sex differences in prenatal epigenetic programming of stress pathways. Stress, 14(4), 348–356. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2011.586447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banister CE, Koestler DC, Maccani MA, Padbury JF, Houseman EA, & Marsit CJ (2011). Infant growth restriction is associated with distinct patterns of DNA methylation in human placentas. Epigenetics, 6(7), 920–927. doi: 10.4161/epi.6.7.16079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]