Abstract

Friends tend to be more similar than non-friends (i.e., homophily) in body image concerns and disordered eating behaviors. These similarities may be accounted for by similarities in eating disorder risk factors and correlates. The current study sought to replicate findings of homophily for eating pathology using social network analysis and to test if similarity in eating pathology is present above and beyond homophily for eating disorder risk factors and correlates. College students (n = 89) majoring in nutrition completed a social network assessment and measures of eating pathology (i.e., body dissatisfaction, binge eating, restricting, excessive exercise), negative affect, and perfectionism. Homophily for eating pathology, negative affect, and perfectionism were tested as predictors of friendship ties using exponential random graph modeling, adjusting for gender, year in school, and body mass index. Results did not support homophily for eating pathology. However, restricting was associated with a lower likelihood of friendship ties. Homophily was present for perfectionism, but not for negative affect. Results suggest that eating pathology may influence the propensity to form friendships and account for previous findings of homophily in the literature. Homophily for perfectionism may have also driven previous findings for homophily. More longitudinal work using social network analysis is needed to understand the role that personality plays in peer influences on eating pathology.

Keywords: body dissatisfaction, eating disorders, restricting, excessive exercise, peer influence, social network analysis

Friends tend to share similar body-related attitudes (Badaly, 2013; Paxton, Schutz, Wertheim, & Muir, 1999; Rayner, Schniering, Rapee, Taylor, & Hutchinson, 2013; Woelders, Larsen, Scholte, Cillessen, & Engels, 2010), dieting attitudes and behavior (Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Paxton et al., 1999; Woelders et al., 2010), and disordered eating behaviors (Badaly, 2013) such as binge eating (Crandall, 1988; Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Rayner et al., 2013; Zalta & Keel, 2006) and unhealthy weight control behaviors (Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Paxton et al., 1999). Given this observed similarity, called homophily, friends are posited to influence eating pathology through socialization processes (Keel & Forney, 2013; Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999). However, most work that directly assesses friends’ disordered eating attitudes and behaviors has not adjusted for similarities in affect and personality. Given that individuals tend to select friends who are similar on a host of demographic features (Bahns, Crandall, Gillath, & Preacher, 2017; McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001), findings of homophily in regards to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors may be an artifact of homophily for other features, including negative affect and perfectionism. Additionally, much of previous research has failed to adjust for endogenous, self-organizing features of social networks, including features such as transitivity and the nonindependence of friendship ties. The current study sought to 1) replicate previous findings of homophily regarding body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors using social network analysis and 2) test if homophily for negative affect and perfectionism may account for observed homophily in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating.

Negative affect is a well-replicated risk factor for eating pathology (Jacobi, Hayward, de Zwaan, Kraemer, & Agras, 2004; Stice, 2002). One study of adolescent girls found that friends tend to be dissimilar on negative affect (Rayner et al., 2013). However, other studies have found that depressive symptoms tend to be similar among friends relative to non-friends (Schaefer, Simpkins, Vest, & Price, 2011) and spread through social networks (Rosenquist, Fowler, & Christakis, 2011). Negative affect represents an important third variable that may explain homophily in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors. Two studies to date have investigated similarity in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors above and beyond similarity in negative affect or depressive symptoms in girls. These studies found that friends exhibit similarity in body dissatisfaction above and beyond negative affect and depressive symptoms, but observed conflicting patterns for dieting and binge eating (Paxton et al., 1999; Rayner et al., 2013). One explanation for discrepant findings may be the assessment of depressive symptoms (Paxton et al., 1999) compared to negative affect (Rayner et al., 2013). A second explanation for discrepant findings may be differences in the statistical analysis; Paxton and colleagues looked at mean scores for friend groups whereas Rayner and colleagues took a social network approach and modeled friendship ties (i.e., connections between people). The social network approach, as described below, is a more rigorous approach that allows for the modeling of endogenous influences in friendship formation and the consideration of multiple homophily influences.

Perfectionism is a well-established correlate of eating pathology (Jacobi et al., 2004; Limburg, Watson, Hagger, & Egan, 2017) that may also play a role in friendship selection. Homophily is present for many of the Big 5 personality traits (Bahns et al., 2017; Noë, Whitaker, & Allen, 2016; Selfhout et al., 2010); however, less is known about homophily for perfectionism. One study found that selected peers were more similar on perfectionism relative to non-selected peers and non-peers (Zalta & Keel, 2006). However, this study did not investigate similarity in both personality and eating pathology simultaneously. Additionally, this study was limited by its use of group means, which do not allow for the consideration of endogenous self-organizing principles in understanding friendship formations as described below. The current study builds upon this prior work by simultaneously examining similarity in perfectionism and eating pathology using a social network approach.

In addition to ruling out possible third variable explanations for homophily, it is important to examine homophily for body image concerns and disordered eating behaviors above and beyond other social influences (Rayner et al., 2013; Simone, Long, & Lockhart, 2018). In particular, social network theorists propose that social networks have endogenous self-organizing features (Lusher & Robins, 2013; Robins, Pattison, Kalish, & Lusher, 2007). One of these self-organizing features is transitivity, or the tendency of an individual to know the friend of a friend. Social network analysis models the friendship ties (‘edges’) of individuals (‘nodes’) in the context of a social network (i.e., friends’ friends). Exponential-family random graph modeling (ERGM) is a type of social network analysis that uses both the structure of the network and individual differences (‘attributes’) of individuals in the network to predict the presence or absence of a friendship tie. This modeling approach can examine both if attributes increase the likelihood of being in a friendship dyad, as might happen if binge eating is linked with popularity (Crandall, 1988), as well as examine if individuals tend to be in friendships with peers who are similar on these attributes (homophily). Adjusting for these attribute effects is important in accurately understanding patterns of homophily. On average, any given individual is most likely to be friends with someone who is popular and has more friendship ties. Thus, if individuals who engage in binge eating are more popular, then by chance, individuals would be more likely to be friends with others who engage in binge eating. Thus, we might falsely conclude that friends tend to be similar in binge eating (homophily), rather than the more accurate conclusion that people who binge eat tend to have more friends (individual differences associated with increased friendship ties).

Only one study to date has used ERGM to examine homophily for disordered eating in adults (K. R. Becker, Stojek, Clifton, & Miller, 2018). In this study, the authors found that women with higher eating pathology levels were less likely to have connections with other women in their social sorority. Additionally, the more dissimilar the two women were on eating pathology, the more likely the women were to be connected to each other. That is, the opposite of homophily was found for eating pathology. The authors also examined binge-eating frequency; a woman’s binge-eating frequency was not related to her tendency to have connections, nor was there evidence of homophily for binge-eating. These findings were discordant with expected findings given the existing literature and call for replication using similar methodology.

The current study sought to replicate previous findings that friends exhibit similarity regarding body dissatisfaction and disordered eating using a newer statistical approach, ERGM, in a sample of college students studying nutrition. By the nature of their coursework, these students are likely to be engaged in conversations about eating and weight. We hypothesized that friends would exhibit similarity regarding body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors. We focused on the disordered eating behaviors of binge eating, restricting, and excessive exercise in order to replicate previous findings of similarity for binge eating (Crandall, 1988; Zalta & Keel, 2006) and restrictive behaviors (Meyer & Waller, 2001) and to examine the compensatory behavior with the highest prevalence (excessive exercise; Luce, Crowther, & Pole, 2008). The second aim of the study was to examine how similarity in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors predict friendship ties, above and beyond negative affect and perfectionism. We hypothesized that homophily for body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors would exist above and beyond homophily for negative affect and perfectionism. The current study represents a stringent test of existing models of peer influence of disordered eating. If statistical methodology or affect and personality account for previous findings regarding peer influence on eating pathology, then theoretical models, and thus prevention models, will need to be revised accordingly.

Materials and Methods

Participants

All undergraduate students majoring in nutrition at a mid-sized public university were invited to participate. Of the 200 eligible students, 99 completed measures of the social network. A sample of 83 women and 6 men completed both the network questionnaire and questionnaire assessments and were included in the current analysis. Most participants identified as White/Caucasian (n = 82, 92%) and none identified as Hispanic. Five individuals did not answer items about race and ethnicity. Participants had a mean (SD) age of 20.38 (1.31) years. Participants spanned the range of academic years; 15% (n = 13) identified as first year students, 20% (n = 18) identified as sophomores, 26% (n = 23) identified as juniors, 35% (n = 31) identified as seniors and 4% identified as 5th year seniors (n = 4). Less than 10% (n = 8) of participants reported a lifetime history of eating disorder treatment.

Procedures

Participants were recruited using two methods. First, students were recruited through the department undergraduate research participant pool and offered extra credit as compensation. Second, students were recruited via the department listserv and offered $10 compensation for completing questionnaires. All data collection occurred within the same academic semester. All participants provided informed consent before participating, and the Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Network Measure

Participants were given a roster of all undergraduate nutrition majors and asked to select “which of the following members of the nutrition major you consider to be your friends (check as many as apply). Friends, defined as someone who you spend most of your time with, or seek advice from, in the major.” An undirected network was calculated such that if i selected j as a friend, both ij and ji were equivalently coded as having a friendship tie.

Demographics

Participants completed demographics questionnaires including items about year in school, race/ethnicity, age, height, weight, and lifetime treatment for an eating disorder. Body mass index was calculated from self-reported height and weight and calculated in kg/m2.

Eating Pathology

Eating pathology was assessed using the Eating Pathology Symptom Inventory (EPSI; Forbush et al., 2013). The EPSI comprises eight subscales that assess different eating pathology symptoms. Current analyses use the Body Dissatisfaction (7 items), Binge Eating (8 items), Excessive Exercise (5 items), and Restricting (6 items) subscales. The Body Dissatisfaction, Excessive Exercise, and Restricting subscales discriminate between individuals with eating disorders and community members (Forbush et al., 2013) and all four subscales demonstrate the expected convergent validity with other eating pathology measures (Forbush et al., 2013). Reported 2 to 4-week test-retest reliability was good in a college sample (Forbush et al., 2013). Internal consistency was acceptable for all subscales in the current study (Cronbach’s alpha = .80 - .87).

Negative Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson & Clark, 1999) assessed negative affect over “the past few weeks.” The Negative Affect scale comprises 10 items such as “irritable” and asks participants to rate the frequency with which they experienced the emotion on a scale from 1 to 5, with 5 being “extremely.” The Negative Affect subscale has previously demonstrated convergent validity with depressive symptoms and general distress (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). The Negative Affect subscale prospectively predicts binge eating and dietary restriction, supporting its relevance for eating pathology (Dakanalis et al., 2014). Internal consistency was good, Cronbach’s alpha = .84.

Perfectionism

The Reactivity to Mistakes subscale of the Measure of Constructs Underlying Perfectionism (M-CUP) was used to assess maladaptive perfectionism (Stairs, Smith, Zapolski, Combs, & Settles, 2012). This subscale consists of seven items and measures the tendency to experience negative affect after perceiving one has made a mistake. The scale has a large correlation with the Eating Disorder Inventory-Perfectionism subscale (Stairs et al., 2012), which has previously been shown to predict the onset of and maintenance of eating pathology (Holland, Bodell, & Keel, 2013). The scale’s convergent validity is supported by associations with maladaptive conscientiousness (Stairs et al., 2012). Test-retest reliability ranged from .65 to .77 across time intervals of 1 to 13 weeks (Stairs et al., 2012). Internal consistency was good, Cronbach’s alpha = .93.

Data Analysis Plan

Associations between key study variables were examined using Pearson correlations (see Table 1). Missing data for personality variables were imputed for four individuals using the average of five iterations of the multiple imputation procedure in SPSS. Missing data for gender was imputed for four individuals using the same procedures.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics of Key Study Variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. BMI | -- | ||||||

| 2. Body Dissatisfaction | −.03 | -- | |||||

| 3. Binge Eating | .04 | 41*** | -- | ||||

| 4. Restricting | −.31** | .50*** | .08 | -- | |||

| 5. Excessive Exercise | .06 | .51*** | .33** | .32** | -- | ||

| 6. Negative Affect | −.02 | .45*** | .22* | .39*** | .33** | -- | |

| 7. Perfectionism | −.04 | .52*** | .28** | .46*** | .41 *** | .58*** | -- |

| Mean | 22.16 | 12.39 | 10.18 | 5.53 | 9.54 | 21.29 | 21.93 |

| SD | 2.79 | 5.92 | 4.75 | 3.75 | 4.49 | 6.20 | 7.07 |

Note: Body Dissatisfaction, Binge Eating, Restricting, and Excessive Exercise come from the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory; Negative Affect is assessed using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule- Expanded Version; Perfectionism is assessed using the Reactivity to Mistakes subscale from the Measure of Constructs Underlying Perfectionism; BMI = Body Mass Index;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Exponential-Family Random Graph Models

To test hypotheses that similarity on eating pathology and personality is associated with the greater likelihood of a friendship tie, we estimated Exponential-Family Random Graph Models (ERGM) using the package ergm in R (Hunter, Handcock, Butts, Goodreau, & Morris, 2008). All models were estimated using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) maximum likelihood. After 1000 burn ins, models used 10,000 samples to estimate parameters. All models were examined for degeneracy using MCMC diagnostics in the ergm package. Goodness of fit was assessed by examining simulations of the observed network generated from the estimated parameters (degree, edgewise shared partners, minimum geodesic distance; Hunter, Goodreau, & Handcock, 2008). Goodness of fit plots are available upon request from the authors.

Endogenous Organizing Factors

In testing study hypotheses, we first estimated a model with theoretically relevant endogenous and exogenous characteristics in addition to eating pathology. Friendship tie density was modeled using the edges command. Parameter estimates indicate the log-odds of a tie when all other parameters are at zero. Transitivity, or the tendency to form friendship triads, was modeled using geometrically-weighted edgewise shared partner distribution (gwesp) with a fixed coefficient of .693 (Koskinen & Daraganova, 2013). A positive coefficient indicates greater centralization of ties.

Exogenous Organizing Factors: Attribute Effects for Covariates

Attribute effects of gender and BMI on the tendency to form friendships were tested using nodefactor and nodecov, respectively. Because “male” was coded as higher than “female,” a positive nodefactor indicates males are more likely to have a friendship tie than females. Nodecov is calculated as the sum of attributes for each friendship tie in the network. A higher value indicates a greater tendency for individuals with higher levels of an attribute to have a friendship tie. Testing for attribute effects rules out the possibility that observed homophily is a statistical artifact of individuals with an attribute being more likely to form friendships in general, rather than being more likely to form friendships with similar others (Goodreau, Handcock, Hunter, Butts, & Morris, 2008; Robins & Daraganova, 2013).

Exogenous Organizing Factors: Homophily Effects for Covariates

Given evidence that friendship ties are formed on the basis of gender and BMI (Christakis & Fowler, 2007; McPherson et al., 2001), homophily for gender and homophily for BMI were modeled using nodematch and absdiff, respectively. A positive coefficient for nodematch indicates individuals who share an attribute (i.e., gender) are more likely to have ties than individuals who do not share an attribute. In absdiff, homophily is tested using the absolute difference of two individuals’ scores; negative parameter estimates indicate that the more similar two individuals are, the more likely they have a friendship tie. Nodefactor and nodematch also were used to adjust for attribute effects and homophily due to year in school.

Exogenous Organizing Factors: Testing Key Study Hypotheses

In Model 1, nodecov and absdiff were used to test for attribute effects and homophily for the eating pathology variables, respectively. In Model 2, we added nodecov and absdiff terms for perfectionism and negative affect to examine if homophily in eating pathology explained additional variance in friendship ties above and beyond homophily in personality and affect. The pattern of results was the same with outliers brought in.

Results

Table 1 displays associations between our variables of interest. BMI was negatively associated with restricting such that those with the lowest BMI reported engaging in the most dietary restriction. BMI was not correlated with any other eating pathology variables. Most eating pathology variables were positively associated with one another with medium to large effect sizes; however, binge eating was not associated with restricting. Finally, both negative affect and perfectionism were positively associated with the eating pathology variables.

Second, we examined the nutrition student network. In a network of 89 individuals, we observed 208 friendship ties, for an overall density of 0.05. This indicates a 5% chance that any two individuals were friends. This density value is comparable to reported densities in samples of high schools (e.g, .07; Rayner et al., 2013). Each person had an average of 4.45 friends.

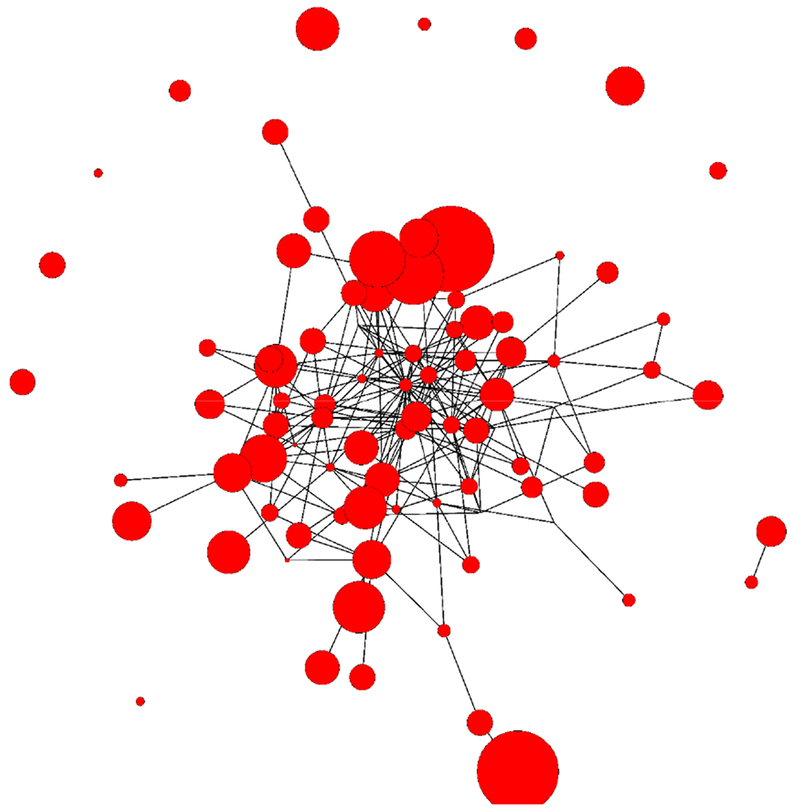

Transitivity, or the tendency of y to know z if x knows y and z, was 0.18, indicating there is almost a 20% chance that y is friends with z if x is friends with y and z. A random graph (i.e., no evidence of endogenous or exogenous influences) would have a transitivity value close to its density (Borgatti, Everett, & Johnson, 2013). A visual display of the network is found in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Display of friendship ties and restricting scores in a network of nutrition students. Circles represent individuals whereas lines represent friendship ties. The size of the circle corresponds to the individual’s restricting score.

Predicting Friendship Ties from Eating Pathology

Model fit statistics and parameters are presented in Table 2. The initial model with self-organizing influences, attribute effects, and homophily for year in school, gender, BMI, body dissatisfaction, restricting, binge eating, and excessive exercise failed to converge. Homophily for gender was dropped from the model given that relatively few men were included in the sample. The model converged without a term modeling homophily for gender. Results are presented without a homophily effect for gender; the pattern of the results was the same when including a homophily for gender term without an attribute effect for gender.

Table 2.

Cross-sectional Exponential Random Graph Models Predicting Friendship Ties Based on Homophily for Eating Pathology and Personality

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimate(SE) | Estimate(SE) | |

| Endogenous Organizing Factors | ||

| Edges | 3.02(1.34)* | 3.62(1.43)* |

| GWESP | 0.31(0.09)*** | 0.29(0.08)*** |

| Exogenous Organizing Factors | ||

| Attribute Effects | ||

| Gender | 0.86(0.29)** | 0.85(0.29)** |

| Year in School | ||

| Sophomore | 0.19(0.23) | 0.19(0.24) |

| Junior | 0.34(0.23) | 0.38(0.23) |

| Senior | 0.95(0.24)*** | 1.02(0.24)*** |

| 5th Year Senior | 0.88(0.32)** | 0.97(0.33)** |

| BMI | −0.17(0.03)*** | −0.17(0.03)*** |

| Body Dissatisfaction | 0.002(0.01) | 0.01(0.01) |

| Restricting | −0.06(0.02)** | −0.06(0.02)** |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.02(0.01)† | 0.03(0.01)* |

| Binge Eating | −0.004(0.01) | −0.004(0.01) |

| Negative Affect | −0.02(0.01) | |

| Perfectionism | −0.004(0.01) | |

| Homophily Effects | ||

| Year in School | 0.41(0.19)* | 0.41(0.19)* |

| BMI | −0.01(0.04) | −0.01(0.04) |

| Body Dissatisfaction | 0.01(0.02) | 0.01(0.02) |

| Restricting | −0.04(0.03) | −0.04(0.03) |

| Excessive Exercise | 0.02(0.02) | 0.02(0.02) |

| Binge Eating | −0.02(0.01) | −0.02(0.02) |

| Negative Affect | 0.02(0.02) | |

| Perfectionism | −0.04(0.01)* | |

| Fit Statistics | ||

| Negative Log Likelihood | −692.10 | −686.68 |

| AIC | 1420 | 1417 |

Note: GWESP = geometrically-weighted edgewise shared partner distribution; BMI = Body mass index; Perfectionism is assessed using the Reactivity to Mistakes subscale from the Measure of Constructs Underlying Perfectionism (M-CUP);

p <. 10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

The edges term was significant (p = .02), indicating the overall log-odds of a tie when all other parameters are zero. Transitivity explained significant variance (p < .001) in friendship ties, indicating a tendency for friendship triads to form. Men were more likely than women to be in a friendship dyad (p = .003). Senior (p < .001) and 5th year senior (p = .01) students were more likely to be in friendships than first year students, whereas sophomore (p = .40) and junior students (p = .13) were not significantly more likely to be in friendships than first year students. Participants were more likely to be friends with their same year classmates relative to classmates in different years (p = .03). Having a lower BMI was associated with a greater likelihood of a friendship tie (p < .001), whereas there was not evidence for homophily regarding BMI (p = .79). That is, friends did not tend to have more similar BMIs than non-friends.

Regarding eating pathology, lower restricting scores (p = .004) were associated with greater likelihood of a friendship tie. Figure 1 displays the network with restricting scores indicated by the size of the nodes. Body dissatisfaction (p = .86), binge eating (p = .76), and excessive exercise (p = .07) scores were not associated with the likelihood of friendship ties. No significant homophily effects were observed for any eating pathology variables (p’s > .14).

Predicting Friendship Ties from Eating Pathology, Negative Affect and Perfectionism

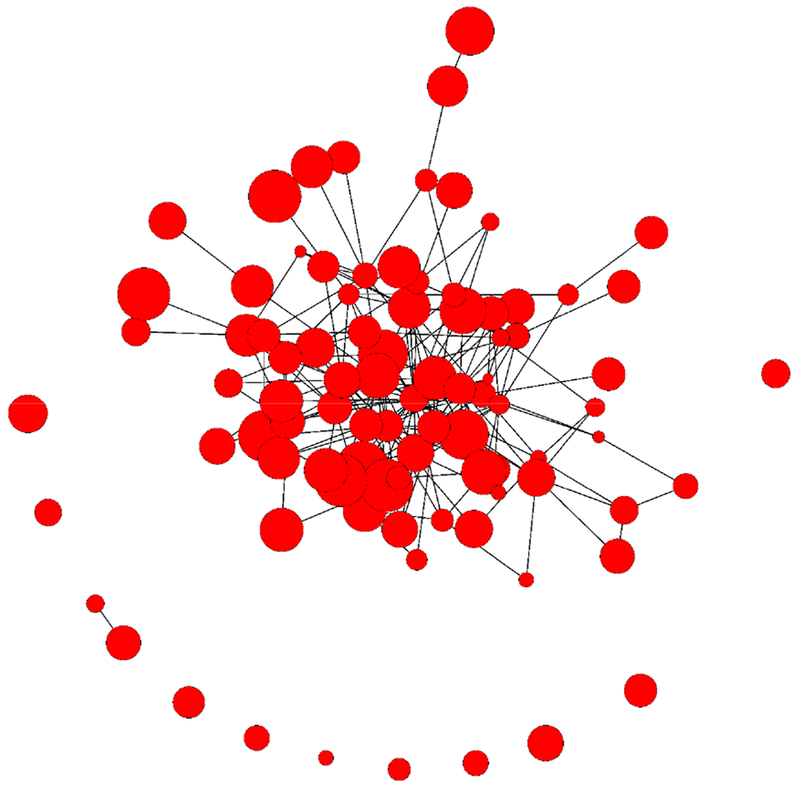

Model 2 added attribute effects and homophily effects for negative affect and perfectionism. The addition of these terms did not significantly improve model fit, X2(4) = 5.42, p = .25; change in AIC = 3. Higher restricting scores continued to be associated with a lower likelihood of friendship ties (p = .008) and higher excessive exercise scores were associated with a greater likelihood of friendship ties (p = .04). Neither negative affect nor homophily for negative affect were associated with a greater likelihood of friend ties (p’s > .12). Although level of perfectionism was not associated with the likelihood of friendship ties (p = .64), there was a significant effect for homophily for perfectionism (p = .006), indicating friends tended to be more similar on perfectionism than non-friends. Figure 2 displays the network with perfectionism scores indicated by the size of the nodes.

Figure 2.

Display of friendship ties and perfectionism scores in a network of nutrition students. Circles represent individuals whereas lines represent friendship ties. The size of the circle corresponds to the individuals’ perfectionism score.

Discussion

The current study sought to replicate previous findings of homophily among friends in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors and to test if homophily among friends in negative affect and perfectionism explained homophily among friends in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating behaviors. Our findings failed to replicate previous studies that found similarity among friends (relative to non-friends) for body dissatisfaction (Paxton et al., 1999; Rayner et al., 2013; Woelders et al., 2010), restricting (Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Paxton et al., 1999; Woelders et al., 2010), and binge eating (Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Rayner et al., 2013; Zalta & Keel, 2006). Instead, we observed that some disordered eating behaviors were associated with the tendency to be part of a friendship dyad, with those high in restricting less likely to report friendships within the nutrition major. There was no evidence of similarity among friends in regard to body dissatisfaction or other aspects of eating pathology, consistent with recent research using ERGM (K. R. Becker et al., 2018). Because we did not observe homophily for eating pathology, we could not test our hypothesis that homophily for eating pathology would be present above and beyond homophily for personality. We did, however, observe homophily for perfectionism (Zalta & Keel, 2006), suggesting similarities in perfectionism may be related to the tendency to form friendships.

We observed that individuals high in restricting were less likely to be in friendship dyads relative to those lower in restricting, replicating previous research suggesting girls and women lower in dieting (Rayner et al., 2013) and eating pathology (K. R. Becker et al., 2018) are more likely to be in friendship dyads. Difficulties in forming and maintaining friendships may lead to the development of disordered eating behaviors as way to cope with psychosocial stressors (Monterubio, Fitzsimmons-Craft, & Wilfley, 2015), or engaging in weight loss behaviors may be a strategy to increase likeability and popularity (Lieberman, Gauvin, Bukowski, & White, 2001; Shroff & Thompson, 2006; Simone et al., 2018). More longitudinal research incorporating objective data from peers is needed to understand the relationship between social functioning and engagement in restricting behaviors. In contrast to findings regarding restricting behaviors, we observed a tentative finding that individuals high in excessive exercise were more likely to form friendships. Previous work suggests that women who are more connected to “powerful” individuals in their social network endorse greater compulsive exercise (Patterson & Goodson, 2017). It may be that a strong commitment to exercise is valued in young adults. However, as this effect was only detectable when adjusting for personality, this result needs replicated.

Adding to the growing literature on homophily in personality (Noë et al., 2016; Selfhout et al., 2010), we observed homophily for perfectionism (Zalta & Keel, 2006). It may be that previous findings of homophily for eating pathology could be accounted for by third variables, such as personality. Although this study was unable to replicate effects of homophily for eating pathology, findings provide partial support for a model in which peers select friends based on similarity in personality. Once within selected friend groups, peer influences may lead to an increase in body image concerns or disordered eating over time through socialization processes (Keel & Forney, 2013; Meyer & Waller, 2001). Because this study was limited to a single point in time, we were unable to observe if socialization occurred. The hypothesis that socialization for disordered eating behaviors only occurs within peers matched on eating disorder correlates, such as perfectionism, should be in tested in a longitudinal design. We were unable to find evidence of homophily or heterophily for negative affect (Rayner et al., 2013), perhaps due to our cross-sectional design.

Our failure to replicate homophily findings for eating pathology may reflect differences in populations, measurement, and methodology. Previous work using social network analysis has found significant selection effects for body dissatisfaction (Rayner et al., 2013) and disordered eating behaviors (Rayner et al., 2013; Simone et al., 2018) in adolescents. Different features may be more salient in forming friendships in mixed gender groups of young adults. Previous work using social network analysis in college women suggests that friends are dissimilar on eating pathology (K. R. Becker et al., 2018), and it may be that disordered eating behaviors are stigmatized in college students. This may be particularly true in our sample of nutrition students. It is also likely that students have friends outside of their college major. Thus, the current study was unlikely to have observed any given individual’s total social network. In contrast, studies of girls enrolled in elementary and high school may have been more likely to capture the entire relevant social network and thus been able to detect patterns of homophily (Paxton et al., 1999; Rayner et al., 2013; Simone et al., 2018; Woelders et al., 2010). Other college friends, friends from high school, and family members may have more influence on individuals’ eating behaviors, and should be investigated in future work.

In addition to differences in population, we used a different eating pathology questionnaire relative to previous work. The EPSI was developed to have a reproducible factor structure and high discriminate validity (Forbush et al., 2013). Thus, the discrepant findings may reflect a difference in what constructs questionnaires are assessing (Rayner et al., 2013; Zalta & Keel, 2006). For example, the Eating Disorder Inventory-Bulimia subscale assesses both binge eating and compensatory behaviors (Garner, Olmstead, & Polivy, 1983), whereas the EPSI assesses binge eating and compensatory behaviors in separate scales. However, this explanation for discordant findings seems unlikely given some similarities between our findings and previous work using ERGM in adults (K. R. Becker et al., 2018). Much of the work supporting similarity among friends has not accounted for the endogenous self-organizing features of social networks or the impact of individual differences on friendship formations. Thus, our discrepant results may reflect more stringent statistical methodology. Indeed, without the inclusion of terms modeling the influence of eating pathology on friendship tie formation, results would have erroneously supported homophily for restricting (Estimate = −.08, p < .001). Relatedly, we failed to replicate previous results of homophily for BMI (Christakis & Fowler, 2007). This may reflect our use of self-reported, rather than measured, height and weight. Additionally, our sample likely had a lower prevalence of overweight/obesity in our sample (13.4%) relative to previous work in adults across the lifespan (Christakis & Fowler, 2007).

The current study benefited from many methodological strengths, including the use of measures with strong psychometric properties and the social network approach. The social network approach does not rely on perceptions of peers, reducing self-report bias (Jorgensen, Forney, Hall, & Giles, 2018). By adjusting for attribute effects of eating pathology on the tendency to form friendships, we took a stringent statistical approach. The study is not without limitations, including a relatively low participation rate. Nutrition students may not be representative of the general population; however, this student population does not tend to differ in disordered eating attitudes and behaviors relative to other students (Rocks, Pelly, Slater, & Martin, 2017; Yu & Tan, 2016) and we observed mean scores on the EPSI comparable to or lower than other college samples (Forbush, Wildes, & Hunt, 2014; Kilwein, Goodman, Looby, & De Young, 2016). We also relied on self-reported BMI. Given these students’ future professions, it is unknown to what extent social desirability influenced their responses. Finally, we were limited to cross-sectional analysis and are unable to speak to selection or socialization effects over time. Should future research support socialization effects, peer prevention programs, like the Body Project (C. B. Becker, Smith, & Ciao, 2006; Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008), may be fruitful within student populations that may frequently discuss eating and weight control behaviors.

Taken together, the current study contributes to a growing literature using social network analysis to understand eating pathology among friends. We did not find evidence for homophily above and beyond self-organizing principles or the impact of eating pathology on friendship formation. Instead, we found that students who endorsed higher levels of restricting behaviors were less likely to have friendship ties. Thus, this study highlights the importance of methodology for studying peer influences. In particular, the use of social network analysis, inclusion of eating disorder risk factors and correlates, and examination of the influence of disordered eating behaviors on the likelihood to form friendships are all important considerations. Given observed similarity among friends for perfectionism, future research on peer influences for eating pathology would benefit from a better understanding of the role of personality in friendship formation. Findings that disordered eating behaviors are associated with the presence or absence of friendship ties highlight the importance of measuring psychosocial functioning when studying peer influences on eating pathology in order to have a more accurate picture of social processes at play. Pending future replication of this work, psychosocial models of eating disorder risk may benefit from greater inclusion of social functioning as risk and/or maintenance factors and may need to be revised to more accurately represent the role of peers in eating disorder risk.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Forney’s research time was supported by F31MH105082 from the National Institute of Mental Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest: none

References

- Badaly D (2013). Peer similarity and influence for weight-related outcomes in adolescence: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 1218–1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahns AJ, Crandall CS, Gillath O, & Preacher KJ (2017). Similarity in relationships as niche construction: Choice, stability, and influence within dyads in a free choice environment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(2), 329–355. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker KR, Stojek MM, Clifton A, & Miller JD (2018). Disordered eating in college sorority women: A social network analysis of a subset of members from a single sorority chapter. Appetite, 128, 180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2018.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker CB, Smith LM, & Ciao AC (2006). Peer-facilitated eating disorder prevention: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(4), 550–555. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.550 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borgatti SP, Everett MG, & Johnson JC (2013). Characterizing whole networks. Analyzing social networks (pp. 149–162). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis NA, & Fowler JH (2007). The spread of obesity in a large social network over 32 years. New England Journal of Medicine, 357, 370–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa066082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crandall CS (1988). Social contagion of binge eating. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(4), 588–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dakanalis A, Timko CA, Carra G, Clerici M, Zanetti MA, Riva G, & Caccialanza R (2014). Testing the original and the extended dual-pathway model of lack of control over eating in adolescent girls. A two-year longitudinal study. Appetite, 82, 180–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Wildes JE, & Hunt TK (2014). Gender norms, psychometric properties, and validity for the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(1), 85–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbush KT, Wildes JE, Pollack LO, Dunbar D, Luo J, Patterson K, … Stone A (2013). Development and validation of the Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory (EPSI). Psychological Assessment, 25(3), 859–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner DDM, Olmstead MP, & Polivy J (1983). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2(2), 15–34. doi: 10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:23.0.CO;2-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Handcock MS, Hunter DR, Butts CT, & Morris M (2008). A statnet tutorial. Journal of Statistical Software, 24(9), 1–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland LA, Bodell LP, & Keel PK (2013). Psychological factors predict eating disorder onset and maintenance at 10-year follow-up. European Eating Disorders Review, 21(5), 405–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DR, Goodreau SM, & Handcock MS (2008). Goodness of fit of social network model. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 103(481), 248–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DR, Handcock MS, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, & Morris M (2008). Ergm: A package to fit, simulate and diagnose exponential-family models for networks. Journal of Statistical Software, 24(3), nihpa54860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson DM, & Rapee RM (2007). Do friends share similar body image and eating problems? The role of social networks and peer influences in early adolescence. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45(7), 1557–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, & Agras WS (2004). Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin, 130(1), 19–65. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen T, Forney KJ, Hall JA, & Giles SM (2018). Using modern methods for missing data analysis with the social relations model: A bridge to social network analysis. Social Networks, 54, 26–40. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2017.11.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, & Forney KJ (2013). Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(5), 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilwein TM, Goodman EL, Looby A, & De Young KP (2016). Nonmedical prescription stimulant use for suppressing appetite and controlling body weight is uniquely associated with more severe eating disorder symptomatology. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(8), 813–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen J, & Daraganova G (2013). Exponential random graph model fundamentals In Lusher D, Koskinen J & Robins G (Eds.), Exponential random graph models for social networks: Theories, methods, and applications (pp. 49–76). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman M, Gauvin L, Bukowski WM, & White DR (2001). Interpersonal influence and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls: The role of peer modeling, social reinforcement, and body-related teasing. Eating Behaviors, 2(3), 215–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limburg K, Watson HJ, Hagger MS, & Egan SJ (2017). The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(10), 1301–1326. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luce KH, Crowther JH, & Pole M (2008). Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q): Norms for undergraduate women. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(3), 273–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusher D, & Robins G (2013). Formation of social network structure In Lusher D, Koskinen J & Robins G (Eds.), Exponential random graph models for social networks: Theories, methods, and applications (pp. 16–28). New Yoork, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 415–444. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer C, & Waller G (2001). Social convergence of disturbed eating attitudes in young adult women. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 189(2), 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monterubio GE, Fitzsimmons-Craft EE, & Wilfley DE (2015). Interpersonal dysfunction as a risk factor for eating disorders In Wade TD (Ed.), Encyclopedia of feeding and eating disorders (pp. 1–4). Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Noë N, Whitaker RM, & Allen SM (2016). (2016). Personality homophily and the local network characteristics of Facebook Paper presented at the 2016 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Advances in Social Networks Analysis and Mining (ASONAM), San Francisco, CA: 386–393. doi: 10.1109/ASONAM.2016.7752263 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson MS, & Goodson P (2017). Using social network analysis to better understand compulsive exercise behavior among a sample of sorority members. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 14(5), 360–367. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2016-0336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Schutz HK, Wertheim EH, & Muir SL (1999). Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108(2), 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner KE, Schniering CA, Rapee RM, Taylor A, & Hutchinson DM (2013). Adolescent girls’ friendship networks, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: Examining selection and socialization processes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(1), 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, & Daraganova G (2013). Social selection, dyadic covariates, and geospatial effects In Lusher D, Koskinen J & Robins G (Eds.), Exponential random graph models for social networks: Theories, methods, and applications (pp. 91–101). New York, New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Robins G, Pattison P, Kalish Y, & Lusher D (2007). An introduction to exponential random graph (p*) models for social networks. Social Networks, 29(2), 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Rocks T, Pelly F, Slater G, & Martin LA (2017). Eating attitudes and behaviours of students enrolled in undergraduate nutrition and dietetics degrees. Nutrition & Dietetics, 74(4), 381–387. doi: 10.1111/1747-0080.12298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenquist JN, Fowler JH, & Christakis NA (2011). Social network determinants of depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 16(3), 273–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer DR, Simpkins SD, Vest AE, & Price CD (2011). The contribution of extracurricular activities to adolescent friendships: New insights through social network analysis. Developmental Psychology, 47(4), 1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selfhout M, Burk W, Branje S, Denissen J, Van Aken M, & Meeus W (2010). Emerging late adolescent friendship networks and big five personality traits: A social network approach. Journal of Personality, 78(2), 509–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shroff H, & Thompson JK (2006). Peer influences, body-image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. Journal of Health Psychology, 11(4), 533–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone M, Long E, & Lockhart G (2018). The dynamic relationship between unhealthy weight control and adolescent friendships: A social network approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(7), 1373–1384. doi: 10.1007/s10964-017-0796-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stairs AM, Smith GT, Zapolski TC, Combs JL, & Settles RE (2012). Clarifying the construct of perfectionism. Assessment, 19(2), 146–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Spoor S, Presnell K, & Shaw H (2008). Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, & Tantleff-Dunn S (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark LA, & Tellegen A (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, & Clark LA (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Unpublished Manual, University of Iowa-Iowa City, Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Woelders LC, Larsen JK, Scholte RH, Cillessen AH, & Engels RC (2010). Friendship group influences on body dissatisfaction and dieting among adolescent girls: A prospective study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 47(5), 456–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, & Tan M (2016). Disordered eating behaviors and food addiction among nutrition major college students. Nutrients, 8(11), 673. doi: 10.3390/nu8110673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zalta AK, & Keel PK (2006). Peer influence on bulimic symptoms in college students. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(1), 185–189. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.1.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]