Introduction:

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) is a high-resolution imaging modality that uses backscattered light to produce cross-sectional images of biological tissue with micro-meter resolution. The first paper published using the term optical coherence tomography appeared in 1991 and arose as a collaboration between the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Harvard University.1 The high spatial resolution makes it an optimal modality for imaging pathologies which affect individual tissue layers and evaluating microfeatures of therapeutic devices. The first in vivo application of OCT was the imaging of the anterior segment of the human eye, an ideal target for this technology since the transparency of the ocular media allows for non-invasive imaging of important eye structures, such as the cornea and the retina.2 A few years later, the integration of fiber optic technologies into OCT systems enabled the development of intravascular imaging catheters for the in vivo visualization of coronary arteries and in situ stents in high resolution.3

The underlying physics is analogous to ultrasound. The time delays and intensity of optical echoes are measured to create tissue microstructural images as a function of depth. Intravascular OCT uses coherent light in the near-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum, as the use of relatively longer wavelengths enables a deeper penetration (typically 1 to 3 mm) into highly scattering media. Combining optical interferometry with coherence gating, OCT detects single-scattered light from biological tissues, generating images with an axial resolution of 10–15 µm or better. The coherence gating and the interferometric detection process offers orders of magnitude superior sensitivity as compared to traditional confocal gating. OCT systems can detect a backscattered signal that is less than 1:1010 of the incident power. In addition, the high dynamic range results in a modality with optimal image contrast which has utility for numerous medical and biological applications. Intravascular OCT requires the use of an optical fiber and an imaging element (i.e., a small focusing lens) to illuminate and collect backscattered light from the artery wall, while rotating and pulling back the catheter optics at high speed through the lumen of an artery. Recent technological advancements, enabling acquisitions at higher frame rates (150 frames per second or more), have boosted the use of intravascular OCT for the clinical imaging of coronary arteries.4, 5 The rapid imaging speed enables a safe and efficient acquisition of volumetric OCT data over arterial segments longer than 50 mm, during a short injection of contrast media for 3 seconds or less. The use of contrast or other flush media (e.g., saline or a mixture of the two) is necessary as the red blood cells are highly scattering particles and need to be displaced from the artery lumen to clear the imaging field-of-view.

The feasibility of intravascular OCT for the clinical imaging of coronary arteries was successfully demonstrated in 2002.6, 7 These earlier investigations highlighted the superior ability of OCT to interrogate the morphological features of coronary plaques (e.g., thin cap fibroatheromas) and implanted stents in comparison to intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) modality. The US Food and Drug Administration approved the use of catheter-based OCT for coronary utilization in 2009. It is estimated that the current number of OCT-guided endovascular interventions surpasses 100,000/year, with continued growth in procedure volume and scientific publications.8 OCT has been widely adopted for numerous imaging applications in the coronaries and is demonstrated to be safe in an unselected and heterogenous group of patients in varying clinical settings.9 The higher resolution enables a much more accurate assessment of the artery lumen geometry and arterial stenoses with respect to other imaging modalities. OCT vividly delineates the vessel wall pathology, including plaque type morphology, composition, rupture and erosion, as well as the vessel wall interaction with therapeutic devices, such as coronary stents, previously unseen using other techniques.10 When compared to angioscopy (direct visualization of the vascular lumen with a catheter instrumented with fiber optics and a small camera), OCT identification of thrombus was shown to be superior to conventional imaging techniques, such as coronary angiography and IVUS.11 OCT has been shown to provide a reliable and detailed assessment of stent underexpansion and other predictors of cardiovascular events, including edge dissections, intraluminal thrombus, thin-cap fibroatheromas and plaque residuals.10, 12 Consensus among many interventional cardiologists has been reached, recommending the use of OCT for the planning and optimization of coronary procedural strategies and incorporation of this technology into the clinical practice guidelines.13 The unique ability to visualize stent apposition and tissue coverage on an individual strut level has been extensively utilized to study the efficacy and safety of newer generations of therapeutic devices, such as drug-eluting intracoronary stents,14, 15 and investigate the mechanisms of stent failure.16 Remarkably, OCT provides an ‘artifact free’ visualization of calcified plaques (i.e., free of saturation, echoing or shadowing artifacts), providing the unique ability to measure calcium distribution, luminal narrowing and plaque thickness, making it an optimal modality for the guidance of complex coronary interventions for calcified lesions.10 More recent clinical trials have demonstrated that the use of OCT affects the physician decision-making process in more than 50% of the coronary procedures17 and, in a large observational study, showed reduced rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events and improved long-term survival, compared to an angiography strategy alone.18 Additional investigations suggest the use of OCT as an effective technique to improve the current strategies for carotid artery stenting, integrating geometrical assessment of carotid stenosis with fine details about plaque characteristics (e.g., tissue type, protrusion, fibrous cap disruption and intraluminal thrombus), not visible with other modalities.19

Catheter-based OCT has been integrated in daily interventional cardiology clinical practice and has rapidly become a key tool for research studies and clinical trials -- investigating the use of novel devices, pharmacological treatments foratherosclerosis20. Over the last decade, OCT has significantly advanced our understanding of vascular pathologies and interventional cardiology techniques. The versatility of this imaging modality has also sparked interest in other fields of endovascular surgery, in particular neurointerventional surgery. OCT techniques and diagnostic principles developed in the coronary circulation can be applied in both the intracranial and extracranial vasculature, and will continue to improve our knowledge of cerebrovascular pathologies and treatment of cerebrovascular diseases.

Historical Review of OCT in Neurointerventional Surgery:

The first description of OCT applied to image a neurovascular implant was done in a preclinical setting, where ex vivo, benchtop OCT imaging was performed on saccular aneurysms from a canine model that had been coiled.21 This work demonstrated that OCT images correlated with histological findings in regard to tissue thickness growing over the surface of the coils, therefore identifying the potential to study the aneurysm healing response to an implanted device. A decade later, using the same venous pouch saccular aneurysm model in the canine carotid artery, in vivo OCT was deployed to study flow diverter (FD) implants using the commercial system approved for coronary artery imaging.22 OCT revealed that apposition of the device to the vessel wall and thrombus formation along the surface of the device could be quantified with high fidelity. Digital subtraction angiography, the gold-standard imaging technique for image-guided neurointerventional surgery, is not reliable for the identification of FD malapposition.23 Importantly, this same report showed a strong relationship of FD-wall apposition, assessed histologically, and early aneurysm occlusion. Subsequently, using the same rabbit model of saccular aneurysms, OCT was used to identify FD malapposition at the level of the aneurysm neck (termed communicating malapposition), which was a strong predictor of failed early aneurysm occlusion.24

Periprocedural thromboembolic events resulting from the implantation of neuroendovascular luminal prostheses remain one of the more prevalent complications in neurointerventional surgery.25 Early identification and treatment of thrombus formation on the surface of the device may assist neurointerventionalists to prevent post-operative sequelae. OCT has been shown to be highly reliable for the imaging of thrombus formation on the FD surface, particularly at the origin of jailed side branches.26 OCT was used in a porcine model to identify the ostial surface area of jailed perforators, which was overestimated by rotational angiography.27 OCT offers the unique ability to define perforator anatomy during procedure planning as well as evaluate the relationship of stents and FDs with the ostia of these critical vessels.28 In addition to providing critical information for procedural planning and guidance, OCT has a role in follow-up imaging to characterize vascular remodeling of the implants. Along the lines of the original application of OCT to study healing response to devices for neurointerventional surgery, in vivo OCT has shown very strong agreement with microscopic histological assessments.29, 30 These data support the concept that cerebrovascular response to neurointerventional devices can be studied in vivo with the precision and accuracy of microscopic evaluation. For example, identifying areas where the devices remain exposed to the blood flow could guide decisions about continuing antiplatelet therapy, the duration of which currently has no broadly accepted consensus.

There have been a few clinical case reports of intravascular OCT in neurointerventional surgery demonstrating the ability to characterize treatment of intracranial atherosclerotic disease,31 vascular remodeling pursuant to stent-assisted aneurysm coiling,32 and delineating pathophysiology traumatic aneurysms of the cervical carotid33. However, intravascular OCT as applied to neurointerventional surgery has largely been limited to studying neurovascular devices in preclinical peripheral vascular models, human cadavers with special preparation,28, 34 or clinical cases involving the extracranial circulation. This is due to the OCT catheter profile and stiffness that are both much higher than devices intended for the tortuous cerebral vasculature. Recently, attempts to perform OCT imaging of a paraophthalmic aneurysm treated with an FD was abandoned due to difficulties navigating the device past the internal carotid artery siphon, with only the proximal aspect of the device ultimately imaged.35 Moreover, the construct of the device that uses a torque wire to spin the lens at high rotational speeds is susceptible to severe imaging artifacts (non-uniform rotational distortion) or even breakage when the pull-back occurs in a highly tortuous path. Recognizing these deficiencies, a smaller profile OCT imaging device was conceived for neuroendovascular procedures36 and deployed in 3 patients.37 Although intracranial navigation was possible, imaging data presented was limited to the extracranial internal carotid artery.

Lessons learned from applications of OCT in clinical coronary and peripheral vascular applications, combined with the research for neurointerventional surgery herein described, present the significant potential to study cerebrovascular pathology, guide treatment and evaluate vascular response to medical devices; however, to realize this potential an imaging device specifically designed for intracranial arterial anatomy is necessary. Despite decades of investment in research on the pathophysiology of intracranial atherosclerosis and brain aneurysms, many questions remain unanswered due in part to somewhat artificial animal models and limited vessel-wall imaging in patients. These questions, such as factors that render aneurysms susceptible to rupture, will require longitudinal clinical research studies with imaging modalities that enable detailed characterization of the pathology. Another application in neurointerventional surgery is emergent large vessel occlusion causing an acute ischemic stroke. Despite the very high success rate in achieving recanalization using mechanical thrombectomy in acute ischemic stroke,38 infrequently technical success of the procedure depends on numerous passes of the device and, even more rarely, the vessel re-occludes. High-resolution OCT that examines the architecture of the vessel wall has the potential to shed light on cerebrovascular disease.

Applications of High-Frequency-OCT for Neurointerventional Surgery:

A dedicated neurovascular OCT device must meet a demanding list of design inputs centered around safe navigation in the highly tortuous cerebrovasculature and provide effective imaging to render interventional guidance all without significantly altering clinical workflow (Table). Recently, our team introduced the use of a novel technology platform, High Frequency OCT (HF-OCT), designed to address these stringent requirements for safety and performance. This next generation system was described at the 15th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neurointerventional Surgery and is specifically designed for neurovascular applications. The prototype tested is deliverable through a standard microcatheter (0.017 inch internal diameter or larger) and allows artifact-free imaging in tortuous anatomy39 (Figure 1). In this challenging anatomy, HF-OCT image quality enabled visualization of the layers of the normal arterial wall (Figure 1B) and the origin of side branches (Figure 1C), with homogenous illumination of the vessel cross-section. With spatial resolution approaching 10 μm, preclinical imaging demonstrates the ability to decipher the details of the relationship between neurovascular devices (i.e., stents and flow-diverters) and the vessel wall, as well as the formation of thrombus at the origin of side branches (Figure 2). Thirteen years ago, benchtop OCT was used for ex vivo imaging of the healing response to embolic coils; today, HF-OCT can be performed in vivo with exceptional image quality of both side-wall and bifurcation aneurysms (Figure 3). As described earlier, angiography alone misses critical findings in coronary interventions that are clearly defined using OCT. Similarly, this may apply to neurointerventional surgery, where the extent of coil herniation into the parent vessel and acute formation of thrombus on the coil surface is not appreciated on DSA but is easily diagnosed using HF-OCT (Figure 3B). The field of view of this new generation HF-OCT technology is capable of imaging in a radius of almost 8 mm (Figure 3C), enabling insights into the wall structure of even giant aneurysms (>15 mm) with a well-placed probe.

Table.

Technical Design Inputs for OCT in Neurointerventional Surgery

| Design Input | Existing OCT Devices | HF-OCT |

|---|---|---|

| Device Profile: Compatible with ≥ 0.017” microcatheter | No | Yes |

| Device Stiffness: Can negotiate tortuous paths | No | Yes |

| Image field-of-view: > 7 mm radius | No | Yes |

| Image in tortuosity: Uniform illumination and free of artifacts | No | Yes |

| Blood clearance: Imaging during standard contrast injection protocol (e.g., 3–5 ml/s for 3 s) | Yes | Yes |

| Pullback length: Image > 8 cm of vessel within 3 s pullback | No | Yes |

Figure 1:

HF-OCT in vivo imaging obtained in a vascular model showing relevant tortuosity comparable to the internal carotid artery. HF-OCT cross-sections show evidence of good quality imaging, including individual vessel wall layers (i.e., a bright intensity internal and external elastic laminae, a low scattering media and the adventitia), homogenous image illumination and absence of artifacts or geometrical distortions. The arrows on the panel (B) inlet point to the internal and external elastic laminae. The cross-sectional image in panel (C) shows the ostium of small branch (approximately 1 mm in size) between 2 and 3 o’clock. The scale-bars of all images correspond to 1 mm; the scale bar on the inlets to 0.5 mm.

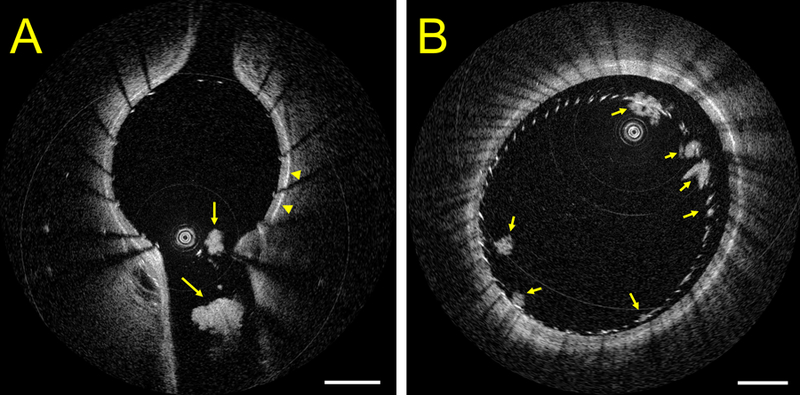

Figure 2:

HF-OCT in vivo imaging of neurovascular stenting (Wingspan, Stryker Neurovascular, Fremont CA) in Panel (A), highlighting the presence of multiple thrombi at the level of the ostium of a side-branch in a pig model with no antiplatelet medication. HF-OCT measurements of the longest thrombus diameter are 0.45 mm and 1.05 mm, respectively. The arrowheads point to the vessel external elastic membrane, illustrating the thickness of the vessel wall. Panel B shows a cross-sectional image of a flow-diverter in the same animal model. A flow-diverter malapposition is visible between 11 and 4 o’clock and HF-OCT imaging reveals the presence of multiple clot accumulations on the surface of the device at different locations (arrows). The image scale bars correspond to 1 mm.

Figure 3:

HF-OCT in vivo imaging of a coiled aneurysm, side-by-side with x-ray imaging, is shown in Panel (A). HF-OCT cross sectional imaging shows accumulation of thrombus on the surface of the coil wires (arrowheads). The three-dimensional HF-OCT rendering on the right shows additional morphological details of the coil wires that are protruding into the parent artery lumen. A close examination reveals that one of the two wires is floating inside the artery lumen, while the second wire is sitting against the wall of the vessel (arrow). Panel (B) shows a second example of HF-OCT in vivo imaging of a coiled aneurysm. HF-OCT cross-sectional imaging depicts a significant amount of intraluminal thrombus protruding into the parent artery lumen that is not visible on DSA. Panel (C) shows an example of a stented common carotid artery (Precise Pro, Cordis), having a lumen diameter of approximately 5.5 mm. Cross-sectional images scale bars correspond to 1 mm. Three-dimensional visualization is obtained by the means of Osirix MD software (version 9.5.2, Pixmeo Sarl 2016). Limited user processing of the HF-OCT data was applied prior to volumetric rendering.

Although the new prototype HF-OCT system addresses the previous limitations of the existing OCT technology, such as near elimination of non-uniform rotational distortion in imaging tortuous paths (Figure 1) and substantive increases in the field of view (Figure 3C), limitations remain. Detection of single-scattered near-infrared light is limited to a maximum tissue penetration depth of 3 mm, which may hinder complete characterization of intracranial atherosclerotic disease or aneurysm wall structure through the parent vessel wall.34 Image quality requires sufficient blood displacement, and if not obtained, blood (or erythrocyte-rich clot) can result in light attenuation and subsequent image degradation. Other well-known artifacts have been previously described, but in general are found to be present only in few images of the vessel segment, are readily identified, and do not impact overall clinical interpretation.5, 10

With full appreciation of these limitations, the benefits provided by HF-OCT have the potential to render a substantive impact in the practice of neurointerventional surgery. In procedural planning where sub-millimeter precision for neurointerventional surgery is critical, precise anatomical and vessel wall pathology understanding as well as sizing will enable improved patient and device selection. Peri-procedurally, HF-OCT can optimize the safety and efficacy of cerebrovascular implants as well as offer prognostic metrics to predict procedure success (e.g., effective aneurysm neck coverage of an intra-saccular or FD device). Finally, in follow-up imaging, the vascular remodeling response to the device can be quantified with near histological precision. In both clinical routine and research, HF-OCT technology represents illuminating progress in the rapid evolution of neurointerventional surgery.

Conclusions

The challenge to engineer implants for the blood vessels of the brain has traditionally been miniaturization to achieve a profile suitable for navigation through the small tortuous cerebrovasculature. Engineers and scientists over the last 3 decades have developed a wide-variety of novel implants that can be used to treat cerebrovascular disease such as acute ischemic stroke and brain aneurysms. However, as device features have entered the micron scale, the ability to see them with traditional x-ray based systems has substantially decreased. High-resolution intravascular imaging holds enormous promise to not only depict these devices, but also the characteristics of the underlying pathology being treated. The advent of HF-OCT could revolutionize the field of neurointerventional surgery enhancing diagnostic accuracy and improving treatment guidance, much like OCT has done and continues to do in coronary artery intervention.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding

This work is in part funded by NIH 1R43NS100163-01A1 and 2R44NS100163-02 (PI: GJU, Co-I: MJG and ASP). The contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosures

G. J. Ughi is an employee of Gentuity LLC. C. W. Liang holds stocks in Gentuity LLC (<$10,000 or 5%) and serves as an advisor. The other authors report no relevant conflicts.

References

- 1.Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science 1991;254:1178–1181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Izatt JA, Hee MR, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Huang D, Schuman JS, et al. Micrometer-scale resolution imaging of the anterior eye in vivo with optical coherence tomography. Arch Ophthalmol 1994;112:1584–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tearney GJ, Brezinski ME, Bouma BE, Boppart SA, Pitris C, Southern JF, et al. In vivo endoscopic optical biopsy with optical coherence tomography. Science 1997;276:2037–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tearney GJ, Waxman S, Shishkov M, Vakoc BJ, Suter MJ, Freilich MI, et al. Three-dimensional coronary artery microscopy by intracoronary optical frequency domain imaging. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging 2008;1:752–761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bezerra HG, Costa MA, Guagliumi G, Rollins AM, Simon DI. Intracoronary optical coherence tomography: A comprehensive review clinical and research applications. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions 2009;2:1035–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang IK, Bouma BE, Kang DH, Park SJ, Park SW, Seung KB, et al. Visualization of coronary atherosclerotic plaques in patients using optical coherence tomography: Comparison with intravascular ultrasound. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002;39:604–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grube E, Gerckens U, Buellesfeld L, Fitzgerald PJ. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Intracoronary imaging with optical coherence tomography: A new high-resolution technology providing striking visualization in the coronary artery. Circulation 2002;106:2409–2410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swanson EA, Fujimoto JG. The ecosystem that powered the translation of oct from fundamental research to clinical and commercial impact. Biomed Opt Express 2017;8:1638–1664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Sijde JN, Karanasos A, van Ditzhuijzen NS, Okamura T, van Geuns RJ, Valgimigli M, et al. Safety of optical coherence tomography in daily practice: A comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;18:467–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tearney GJ, Regar E, Akasaka T, Adriaenssens T, Barlis P, Bezerra HG, et al. Consensus standards for acquisition, measurement, and reporting of intravascular optical coherence tomography studies: A report from the international working group for intravascular optical coherence tomography standardization and validation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:1058–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kubo T, Imanishi T, Takarada S, Kuroi A, Ueno S, Yamano T, et al. Assessment of culprit lesion morphology in acute myocardial infarction: Ability of optical coherence tomography compared with intravascular ultrasound and coronary angioscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:933–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prati F, Guagliumi G, Mintz GS, Costa M, Regar E, Akasaka T, et al. Expert review document part 2: Methodology, terminology and clinical applications of optical coherence tomography for the assessment of interventional procedures. Eur Heart J 2012;33:2513–2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Räber L, Mintz GS, Koskinas KC, Johnson TW, Holm NR, Onuma Y, et al. Clinical use of intracoronary imaging. Part 1: Guidance and optimization of coronary interventions. An expert consensus document of the european association of percutaneous cardiovascular interventions: Endorsed by the chinese society of cardiology. [published online may 22, 2018]. Eur Heart J 2018:https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy1285/5001185. Accessed August 29, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Guagliumi G, Costa MA, Sirbu V, Musumeci G, Bezerra HG, Suzuki N, et al. Strut coverage and late malapposition with paclitaxel-eluting stents compared with bare metal stents in acute myocardial infarction: Optical coherence tomography substudy of the harmonizing outcomes with revascularization and stents in acute myocardial infarction (horizons-ami) trial. Circulation 2011;123:274–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malle C, Tada T, Steigerwald K, Ughi GJ, Schuster T, Nakano M, et al. Tissue characterization after drug-eluting stent implantation using optical coherence tomography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2013;33:1376–1383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adriaenssens T, Joner M, Godschalk TC, Malik N, Alfonso F, Xhepa E, et al. Optical coherence tomography findings in patients with coronary stent thrombosis: A report of the prestige consortium (prevention of late stent thrombosis by an interdisciplinary global european effort). Circulation 2017;136:1007–1021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wijns W, Shite J, Jones MR, Lee SW, Price MJ, Fabbiocchi F, et al. Optical coherence tomography imaging during percutaneous coronary intervention impacts physician decision-making: Ilumien i study. Eur Heart J 2015;36:3346–3355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones DA, Rathod KS, Koganti S, Hamshere S, Astroulakis Z, Lim P, et al. Angiography alone versus angiography plus optical coherence tomography to guide percutaneous coronary intervention: Outcomes from the pan-london pci cohort. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions 2018;11:1313–1321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshimura S, Kawasaki M, Yamada K, Hattori A, Nishigaki K, Minatoguchi S, et al. Oct of human carotid arterial plaques. JACC. Cardiovascular imaging 2011;4:432–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koskinas KC, Ughi GJ, Windecker S, Tearney GJ, Räber L. Intracoronary imaging of coronary atherosclerosis: Validation for diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Eur Heart J 2016;37:524–535a-c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thorell WE, Chow MM, Prayson RA, Shure MA, Jeon SW, Huang D, et al. Optical coherence tomography: A new method to assess aneurysm healing. J Neurosurg 2005;102:348–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van der Marel K, Gounis MJ, Weaver JP, de Korte AM, King RM, Arends JM, et al. Grading of regional apposition after flow-diverter treatment (graft): A comparative evaluation of vasoct and intravascular oct. J Neurointerv Surg 2016;8:847–852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rouchaud A, Ramana C, Brinjikji W, Ding YH, Dai D, Gunderson T, et al. Wall apposition is a key factor for aneurysm occlusion after flow diversion: A histologic evaluation in 41 rabbits. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2016;37:2087–2091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King RM, Brooks OW, Langan ET, Caroff J, Clarencon F, Tamura T, et al. Communicating malapposition of flow diverters assessed with optical coherence tomography correlates with delayed aneurysm occlusion. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:693–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shapiro M, Becske T, Sahlein D, Babb J, Nelson PK. Stent-supported aneurysm coiling: A literature survey of treatment and follow-up. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:159–163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marosfoi M, Clarencon F, Langan ET, King RM, Brooks OW, Tamura T, et al. Acute thrombus formation on phosphorilcholine surface modified flow diverters. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:406–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iosif C, Ponsonnard S, Roussie A, Saleme S, Carles P, Ponomarjova S, et al. Jailed artery ostia modifications after flow-diverting stent deployment at arterial bifurcations: A scanning electron microscopy translational study. Neurosurgery 2016;79:473–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuda Y, Chung J, Keigher K, Lopes D. A comparison between the new low-profile visualized intraluminal support (lvis blue) stent and the flow redirection endoluminal device (fred) in bench-top and cadaver studies. J Neurointerv Surg 2018;10:274–278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuda Y, Chung J, Lopes DK. Analysis of neointima development in flow diverters using optical coherence tomography imaging. Journal of neurointerventional surgery 2018;10:162–167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caroff J, Tamura T, King RM, Lylyk PN, Langan ET, Brooks OW, et al. Phosphorylcholine surface modified flow diverter associated with reduced intimal hyperplasia. [published online march 6, 2018]. J Neurointerv Surg 2018:https://jnis.bmj.com/content/early/2018/2003/2009/neurintsurg-2018-013776.long. Accessed August 29, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Given CA 2nd, Ramsey CN 3rd, Attizzani GF, Jones MR, Brooks WH, Bezerra HG, et al. Optical coherence tomography of the intracranial vasculature and wingspan stent in a patient. J Neurointerv Surg 2015;7:e22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yako R, Matsumoto H, Masuo O, Nakao N. Observation of neointimal coverage around the aneurysm neck after stent-assisted coil embolization by optical frequency domain imaging: Technical case report. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.) 2017;13:285–292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griessenauer CJ, Foreman PM, Deveikis JP, Harrigan MR. Optical coherence tomography of traumatic aneurysms of the internal carotid artery: Report of 2 cases. J Neurosurg 2016;124:305–309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoffmann T, Glasser S, Boese A, Brandstadter K, Kalinski T, Beuing O, et al. Experimental investigation of intravascular oct for imaging of intracranial aneurysms. Int J Comput Assist Radiol Surg 2016;11:231–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Griessenauer CJ, Gupta R, Shi S, Alturki A, Motiei-Langroudi R, Adeeb N, et al. Collar sign in incompletely occluded aneurysms after pipeline embolization: Evaluation with angiography and optical coherence tomography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38:323–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mathews MS, Su J, Heidari E, Linskey ME, Chen Z. Neuro-endovascular optical coherence tomography imaging: Clinical feasibility and applications. Proc SPIE 2011;7883:788341–788347 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews MS, Su J, Heidari E, Levy EI, Linskey ME, Chen Z. Neuroendovascular optical coherence tomography imaging and histological analysis. Neurosurgery 2011;69:430–439 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DWJ, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet 2016;387:1723–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carniato SL, Mehra M, King RM, Wakhloo AK, Gounis MJ. Porcine brachial artery tortuosity for in-vivo evaluation of neuroendovascular devices. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2013;34:E36–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]