African American and Hispanic adolescents experience significantly higher rates of violence victimization compared with White adolescents1–8. This includes greater degrees of child physical abuse4,9, witnessing community violence (e.g., someone being shot)1,9,10, physical assault1, violence severity, and types of violence2,7,11. Such disparities are particularly problematic because of the various harmful sequelae of violence, which include mental, behavioral, and physical health outcomes7,12–16. The number of types of violence reported by adolescents, also referred to as polyvictimization, appears to account for much of the relation between individual types of violence exposure (e.g., child physical abuse) and mental health outcomes11 and may also predict posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms (PTSS) better than sums of exposure to the same type of violence8,11. PTSS, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fifth edition17, include negative alterations in mood, avoidance of reminders of the traumatic event, hyperarousal, and various forms of re-experiencing the traumatic event (e.g., intrusive thoughts or memories). Recent cross-sectional research also indicates that polyvictimization mediates racial/ethnic disparities in depression and PTSS for African American and Hispanic adolescents7. Further, Hispanics and African Americans experience disparities across multiple environmental and contextual factors, such as neighborhood poverty18 or disparate criminal justice involvement19,20, that in turn may increase disparities in violence exposure and related symptoms21–25. Limited research, however, has longitudinally examined the factors that lead to racial/ethnic disparities in violence polyvictimization.

Violence Exposure and Future Risk

One key factor in explaining victimization disparities in adolescence may be that African American and Hispanic adolescents are more likely to experience violence in childhood (e.g., before age 10) compared with White adolescents11. Adolescents exposed to a given type of violence are more likely to experience that type of violence in the future compared with adolescents who have not been exposed26–31. Initial investigations suggest that experiencing violence in one domain also increases the risk of experiencing violence in additional domains31,32. Thus, if African American and Hispanic adolescents experience greater polyvictimization, they may be at risk for experiencing multiple forms of violence in the future, similar to a cascade effect in which early exposure differences may increase the risk of future negative outcomes, altogether altering their developmental trajectory33. Disparities in the initiation of these trajectories may also reflect disparities in the context in which violence exposure occurs, such that earlier violence exposure may reflect neighborhood and familial contexts with heightened risk of violence. Examples include situations in which familial and community resources are low and limit the degree to which families and communities respond to and prevent violence (e.g., improving educational access or involvement in youth activities that reduce violence exposure risk).

Reciprocal Risk with Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms (PTSS) and Delinquency

Potential cascade effects in polyvictimization may be further perpetuated by reciprocal risk patterns in violence exposure and multiple adolescent mental health outcomes. In addition to the effects of polyvictimization on PTSS, PTSS also increase the risk of future violence exposure27,29,34,35, though little research has examined whether PTSS increase the risk of greater polyvictimization specifically. Still, PTSS may increase risk of violence victimization as PTSS may disrupt threat and/or risk detection29,36–38. In turn, PTSS may at least be a marker of behaviors that increase the risk of future victimization for adolescents, which may further racial/ethnic disparities, though this has yet to be tested directly.

Impulsivity and risk recognition symptoms are also present in delinquent behavior39–41, which is also strongly linked to violence polyvictimization42–45. Further, delinquency substantially increases the risk of future violence victimization46,47. Further, biases in perceptions of African American and Hispanic adolescents appears to increase the likelihood of interactions with police and other authority figures, which directly and indirectly can increase delinquent behaviors (e.g., disparities in detention leading to greater exposure to peers with delinquent behavior)19. Such disparities in initial delinquency may further exacerbate the violence exposure and symptom cascades. Relatedly, while similar high-risk behaviors such as substance or alcohol use may also mutually increase victimization risk, delinquency is among the only other mental health or behavioral outcomes across which racial/ethnic disparities consistently occur for African American and Hispanic adolescents40,45,46,48,49. In contrast, African American adolescents frequently report lower rates and Hispanic adolescents often report similar or lower levels of substance and alcohol use compared with White adolescent50–52. Given data on their disparities across race/ethnicity and their roles in predicting violence victimization, PTSS and delinquency may therefore serve as ideal candidates for mediating violence exposure disparities, but this has yet to be tested directly. Further, longitudinal tests of these effects may be ideally suited for adolescence (defined as approximately 10 to 19 years of age53). Violence that occurs prior to adulthood may have stronger effects than when experienced in adulthood54. Additionally, disparities in prior victimization are already present at this developmental epoch1–8. PTSS and delinquency most commonly emerge during adolescence reaching its peak in late adolescence (i.e., 17–19 years of age)55. Finally, disparities in these cascades may be best understood in the context of low-resource familial and environmental environments that may increase risk of initial violence exposure and impede access to recovery resources.

Purpose and Hypotheses

The current study sought to examine the cascade effects among violence polyvictimization, PTSS, and delinquent behavior as mediators of violence exposure disparities among African American and Hispanic adolescents. The study also examined the extent to which indicators of familial and environmental resources accounted for disparities in these cascades—specifically, markers of familial socioeconomic status (poverty and head of household education), caregiver and adolescent perceptions of neighborhood safety, and head of household marital status. Four specific hypotheses were tested:

-

H1:

African American and Hispanic adolescents will evidence greater degrees of violence exposure, including polyvictimization.

-

H2:

PTSS and delinquency will mediate the relationship between polyvictimization and future violence exposure, such that polyvictimization positively predicts PTSS and delinquency, which in turn, positively predict future violence exposure.

-

H3:

Racial/ethnic disparities in polyvictimization and its effects on PTSS and delinquent behavior will mediate disparities in future violence exposure.

-

H4:

Racial/ethnic disparities in environmental and familial factors reflective of low-resource environments will account for disparities in cascades of violence exposure, PTSS, and delinquent behavior.

Method

Procedures

Data were drawn from the National Survey of Adolescents-Replication (NSA-R). The NSA-R was initiated in 2005 with adolescents ages 12 to 17 years using computer-assisted telephone interviewing technology and national household probability sampling with random-digit dialing. Oversampling occurred in urban areas to ensure representation of racial/ethnic groups (49.5% of caregivers reported living in an urban area, with 35.0% and 15.5% reporting living in suburban and rural areas, respectively). Three waves of data were collected and were spaced approximately one year apart, such that adolescents were approximately ages 13 to 18 years at Wave 2 and 14 to 19 years at Wave 3. Additional information regarding sampling and measures have been described previously56. All procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

In total, 3,614 adolescents and their caregivers agreed to participate. After informed consent was obtained, a brief caregiver interview was conducted. Of these caregivers, 2,846 (85.9%) reported being the biological parents of the participants. Then, adolescent assent was obtained. Interviews assessed household characteristics, traumatic event exposure, mental health symptoms, and demographics. During Wave 2 and 3 interviews, assessments of traumatic event exposure and mental health symptoms were repeated and were identical to their Wave 1 counterparts. Attrition occurred at each follow-up interview with 2,511 completing Wave 2 (68.5% retention) and 1,653 completing Wave 3 (45.7% retention). In both cases, most attrition occurred because participants could not be reached for follow-up interviews. Race, PTSS, and violence exposure were all associated with attrition (p-values < .05). At each wave, adolescents participants were compensated $10 for their participation in the interview.

Participants

Analyses of the present study were conducted with the 3,312 adolescents who had completed interviews and self-identified as Hispanic (n = 409, 12.3%), non-Hispanic Black (n = 557, 16.8%), or non-Hispanic White (n = 2,346, 70.8%) during the first wave of data collection. Table 1 contains additional demographic information.

Table 1.

Participant Demographic Information and Descriptive Statistics of Study Variables

| Total Sample | Non-Hispanic Black | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic White | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N or Mean (SD or %) | N or Mean (SD or %) | N or Mean (SD or %) | N or Mean (SD or %) | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1,648 (49.8%) | 268 (48.1%) | 200 (48.9%) | 1,180 (50.3%) |

| Female | 1,664 (50.2%) | 289 (51.9%) | 207 (51.1%) | 1,166 (49.7%) |

| Income CategoryA, B | ||||

| Poverty | 418 (12.6%) | 168 (30.2%) | 73 (17.8%) | 177 (7.5%) |

| Non-poverty | 2,894 (87.4%) | 345 (61.9%) | 308 (75.3%) | 2,008 (85.6%) |

| Age | 14.67 (1.66) | 14.60 (1.65) | 14.62 (1.63) | 14.70 (1.67) |

| Perception of Neighborhood Safety‡ | ||||

| AdolescentA, B | 2.95 (0.99) | 2.70 (1.05) | 2.72 (1.05) | 3.05 (0.95) |

| ParentA, B | 2.47 (0.96) | 1.74 (0.85) | 2.20 (0.92) | 2.70 (0.89) |

| Head of Household Marital StatusA, B | ||||

| Married | 2,358 (71.2%) | 238 (42.7%) | 260 (63.6%) | 1,860 (79.3%) |

| Not Married | 954 (28.8%) | 314 (57.3%) | 149 (36.4%) | 486 (20.7%) |

| Head of Household EducationA, B | ||||

| No formal schooling | 3 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (0.1%) |

| 1st through 7th Grade | 18 (0.5%) | 2 (0.4%) | 11 (2.7%) | 5 (0.2%) |

| Completed 8th Grade | 22 (0.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | 6 (1.5%) | 13 (0.6%) |

| Some High School | 186 (5.6%) | 52 (9.3%) | 36 (8.8%) | 98 (4.2%) |

| High School Graduate | 870 (26.3%) | 196 (35.2%) | 113 (27.6%) | 561 (23.9%) |

| Some College | 952 (28.7%) | 176 (31.6%) | 132 (32.3%) | 644 (27.5%) |

| Four-Year College Graduate | 698 (21.1%) | 78 (14.0%) | 66 (16.1%) | 554 (23.6%) |

| Some Graduate School | 84 (2.5%) | 5 (0.9%) | 12 (2.9%) | 67 (2.9%) |

| Graduate Degree | 467 (14.1%) | 43 (7.7%) | 30 (7.3%) | 394 (16.8%) |

| Any Wave 1 viol. Exp.A, B | 1,638 (49.5%) | 347 (62.3%) | 224 (54.8%) | 1,067 (45.5%) |

| New Wave 2 viol. Exp.A, B | 543 (24.5%) | 116 (35.3%) | 78 (30.4%) | 349 (20.2%) |

| New Wave 3 viol. Exp.A, B | 266 (17.5%) | 55 (28.9%) | 32 (21.9%) | 199 (15.1%) |

| Polyvictimization1 | ||||

| Wave 12, A, B | 1.40 (4.08) | 1.83 (4.51) | 1.71 (5.14) | 1.25 (3.71) |

| Wave 2A, B | 0.42 (0.82) | 0.66 (1.11) | 0.58 (1.15) | 0.36 (0.70) |

| Wave 3A, B | 0.29 (0.55) | 0.52 (0.93) | 0.42 (0.83) | 0.29 (0.44) |

| PTSS1 | ||||

| Wave 1 | 1.64 (8.52) | 1.81 (9.59) | 1.91 (8.84) | 1.55 (8.19) |

| Wave 2A | 2.00 (12.37) | 2.61 (17.78) | 2.36 (12.63) | 1.83 (11.18) |

| Wave 3 | 1.71 (11.19) | 2.03 (13.65) | 2.09 (10.29) | 1.62 (10.86) |

| Delinquency1 | ||||

| Wave 1A, B | 722 (21.8%) | 194 (34.8%) | 114 (27.9%) | 414 (17.6%) |

| Wave 2A | 239 (10.4%) | 53 (16.1%) | 29 (11.3%) | 157 (9.1%) |

| Wave 3A | 149 (9.9%) | 30 (15.8%) | 18 (12.5%) | 101 (8.6%) |

Note: PTSS-Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

Sample sizes vary for polyvictimization, PTSS, and delinquency measures due to attrition across waves of data collection

Wave 1 polyvictimization scores represent lifetime polyvictimization at the wave, whereas Wave 2 and Wave 3 polyvictimization scores represent past-year polyvictimization.

Unadjusted p-values < .01 for comparisons of African American youth to White youth.

Unadjusted p-values < .01 for comparisons of Hispanic youth to White youth.

Measures

Violence exposure and polyvictimization.

Violence exposure was assessed using standardized, highly-structured interviews within the following categories: physical assault, sexual assault, physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessed violence in the home, school, or community. These were further broken down into 22 sub-categories with yes/no items. To increase accuracy of responses, the interview included behaviorally-specific terminology57. Wave 1 interviews assessed lifetime exposure whereas Waves 2 and 3 assessed past-year exposure. This allowed us to examine the effect of any prior exposure on the emergence of new violence victimization. Similar to previous studies on polyvictimization2,5,7,8,11,58–62, event types were then summed. Table 1 includes descriptive information. For additional detailed description of individual traumatic events within each category, see Cisler and colleagues63.

PTSS.

PTSS were assessed utilizing a structured interview of DSM-IV-TR disorder criteria. The interview was adapted from the National Women’ Study PTSD module, which was also used in field trials of DSM-IV criteria64. In this trial, the PTSD module evidenced significant concurrent validity (kappa = .71) with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III, a clinical gold standard for PTSD assessment at the time65. In order to capture wider variability in PTSD compared to discrete diagnostic categories, continuous symptom counts were used. The number of symptoms participants endorsed over the past six-months were then totaled. Table 1 contains additional descriptive information.

Delinquency.

The delinquency interview was based on the Self-Report Delinquency Scale66,67. It assessed domains of physical assault, selling drugs, burglary or robbery, motor vehicle theft, using force to obtain money or things from others, attacking someone with a weapon, and attacking someone with intent to seriously hurt or injure. Wave 1 assessed lifetime and Waves 2 and 3 examined past-year delinquent behavior. Table 1 contains descriptive information.

Adolescent and Caregiver Perceptions of Neighborhood Safety.

Both adolescents and the caregivers interviewed were asked about their perceptions of neighborhood safety. Specifically, caregivers were asked how concerned they were for their child’s safety while in school, in the neighborhood, and the broader community. Responses ranged from 1 (very concerned) to 4 (not at all concerned), such that higher scores reflected higher perceptions of safety. Internal consistency of these items was high (Hispanic α = .82, African American α = .83, White α = .78). Adolescents answered similar questions regarding the degree to which physical assault, sexual assault, and drug abuse were significant problems in their community. Reponses ranged from 1 (a big problem) to 4 (not at all a problem). Internal consistency for this measure was modest (Hispanic α = .62, African American α = .65, White α = .60).

Demographics and Socioeconomic Indicators.

Adolescents reported their gender, age, and race/ethnicity. Income was assessed during the caregiver portion of the survey, with three household income categories: (1) Below $20,000, (2) between $20,000 and $50,000, (3) above $50,000. The first category approximately corresponds with the 2005 U.S. federal poverty level for a four-person household ($19,350) and 200% of the U.S. federal poverty level for a two-person household ($19,140)68, which, respectively, represent the average (Mean = 4.17, Median = 4.00) and smallest household sizes of the adolescents included in the current study. No differences were found between the second and third income groups across violence exposure, mental health symptoms, age, gender, or the primary hypothesized relations (p-values > .05). As a result, these groups were combined and dichotomous groups were utilized to conduct analyses. Head of household marital status was also assessed and was collapsed into two categories for the purposes of analyses—married and not married. Head of household educational attainment was assessed across nine categories ranging from no formal schooling to graduate or professional degree.

Analytic Approach

First, racial/ethnic disparities in each outcome were tested using a path model with dummy-coded race/ethnicity variables (White adolescents were the referent group) as predictors of PTSD symptoms, polyvictimization, and delinquency across all waves with age and gender as control covariates (referred to as Model 1). An additional path model with dichotomized violence exposure variables further examined victimization disparities across each wave.

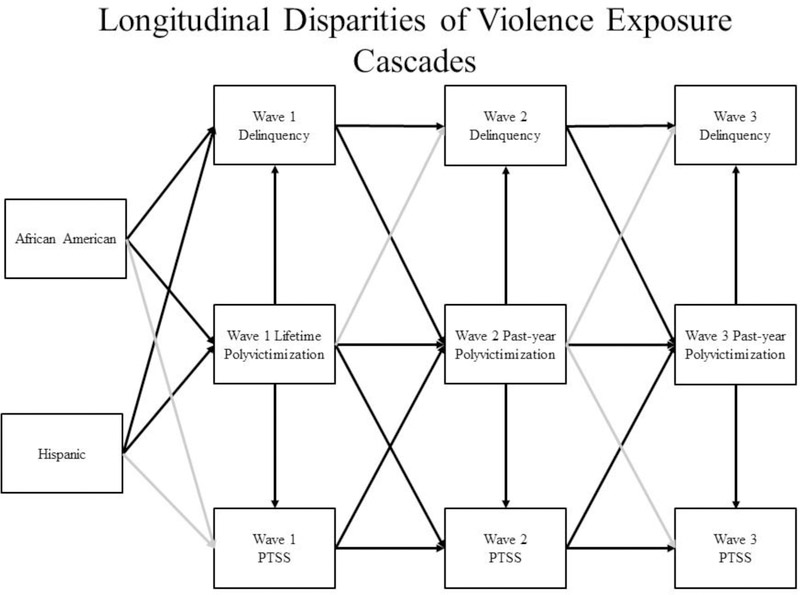

Following this, an autoregressive and cross-lagged structure was constructed utilizing the variables from Model 1. This is referred to as Model 2. For autoregressive paths, earlier wave variables are examined as predictors of subsequent wave variables (e.g., Wave 1 PTSS predicts Wave 2 PTSS, and Wave 2 PTSS predicts Wave 3 PTSS). Cross-lagged paths are similar, except that predictors are also examined longitudinally between symptoms and predictive paths occur in both directions (e.g., Wave 1 delinquency predicts Wave 2 new violence exposure and Wave 1 polyvictimization predicts Wave 2 delinquency). The model differed from typical cross-lagged and autoregressive models in that violence exposure was examined as a within-wave predictor of PTSS and delinquency. This mirrors other cross-lagged studies of PTSS and violence exposure35. Figure 1 shows the model configuration for the cross-lagged and autoregressive model. Following this, environmental (caregiver and child perceptions of neighborhood safety) and familial factors (head of household education, head of household marital status, and household poverty) were added as mediators between race/ethnicity variables and each of the variables in the violence exposure and symptom cascades. This is referred to as Model 3. Gender invariance tests were also conducted and were not significant. As a result, models are presented with male and female adolescents together. The following recommendations by Hu and Bentler69 were used to assess model fit: CFI ≥ .95 and RMSEA ≤ .06. The measure of WRMR < 1.50 was also used as an indicator of acceptable model fit.

Figure 1.

The cross-lagged and autoregressive path model depicting longitudinal disparities in violence exposure cascades. Gray lines depict non-significant paths. Black lines depict significant paths. All significant paths formed part of significant indirect, or mediational, paths. All significant relations displayed here are positive (e.g., higher polyvictimization at Wave 2 predicts higher polyvictimization at Wave 3). The figure is based on a path model examining cascades in violence exposure and related symptoms. PTSS-Posttraumatic stress symptoms.

Given missing data patterns, data were estimated using multiple imputation, which has been previously shown to reduce biases in missing data estimation relative to multiple other estimation methods70. Inverse propensity score weighting was also used to further reduce biases of attrition across waves. The data were also significantly multivariate kurtotic and weighted least squares mean and variance adjusted estimation (WLSMV) was used as this has been shown to be robust against biases from non-normality71.

Results

Model 1: Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Violence Exposure and Related Symptoms

After controlling for age and gender, African American (aOR = 1.90, p < .001) and Hispanic adolescents (aOR = 1.49, p = .001) reported experiencing any prior violence exposure at higher rates at Wave 1 compared with White adolescents. Similar results were found for any past-year violence at Wave 2 for African American (aOR = 2.39, p < .001) and Hispanic adolescents (aOR = 1.62, p = .001) compared with White adolescents. At Wave 3, significantly more African American adolescents (aOR = 2.68, p < .001) but not Hispanic adolescents (aOR = 1.43, p = .059) reported experiencing violence in the past-year relative to White adolescents. African American and Hispanic adolescents also reported experiencing more lifetime polyvictimization at Wave 1 (p-values < .001) and more new polyvictimization at both Waves 2 and 3 (p-values < .01). Additional information regarding differences in violence exposure can be found in Table 1.

Hispanic and African American adolescents reported more PTSS at Wave 2 (p-values < .05) compared with White adolescents, but Wave 1 and 3 differences were not significant (p-values > .05). With regard to delinquency, compared to White adolescents, more Hispanic adolescents reported having engaged in delinquent behavior at Wave 1 and past-year delinquency at Wave 2 (p-values < .05), but did not significantly differ in past-year delinquency at Waves 3 (p = .321). Compared with White adolescents, more African American adolescents reported having engaged in delinquent behavior at each wave (p-values < .01). Table 2 contains additional details regarding racial/ethnic differences in baseline outcomes and Table 3 contains details regarding differences in subsequent waves.

Table 2.

Racial/Ethnic Differences in Baseline Violence Exposure and Related Symptoms with and without Mediators

| Wave 1 Lifetime Polyvictimization | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| African American vs White | .10 | <.001 | .10 | <.001 | .01 | .237 |

| Hispanic vs White | .08 | <.001 | .08 | <.001 | .02 | .613 |

| Age in Years | .21 | .495 | .21 | <.001 | .17 | .019 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | .01 | <.001 | .01 | .493 | −.03 | .024 |

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.05 | .034 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.21 | <.001 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.23 | <.001 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.09 | .012 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.18 | .022 | ||||

| Wave 1 PTSD | ||||||

| African American vs White | .03 | .163 | −.01 | .450 | −.02 | .415 |

| Hispanic vs White | .04 | .071 | .01 | .769 | <.01 | .832 |

| Age in Years | .14 | <.001 | .05 | .008 | .04 | .067 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | .14 | <.001 | .13 | <.001 | .19 | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Lifetime Polyvictimization | .41 | <.001 | .38 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | .01 | .511 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.10 | <.001 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.11 | .005 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | .02 | .471 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.12 | .029 | ||||

| Wave 1 Lifetime Delinquency | ||||||

| African American vs White | .21 | <.001 | .08 | <.001 | .12 | <.001 |

| Hispanic vs White | .12 | <.001 | .16 | <.001 | .06 | .019 |

| Age in Years | .27 | <.001 | .18 | <.001 | .17 | <.001 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −.22 | <.001 | −.23 | <.001 | −.25 | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Lifetime Polyvictimization | .45 | <.001 | .41 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.04 | .191 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.07 | .006 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.17 | .002 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.14 | <.001 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.18 | .015 | ||||

Note: Model 1 examined racial/ethnic differences in violence exposure and symptoms while controlling for only age and gender. Model 2 examined violence exposure and symptom cascades as potential mediators of racial/ethnic differences. Model 3 added familial and contextual variables to Model 2 in order to examine the degree to which these variables explain disparities in the initiation of violence exposure and symptom cascades.

Table 3.

Autoregressive and Cross-lagged Effects of Violence Exposure, Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms, and Delinquency with Covariates

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| African American vs White | .11 | <.001 | .04 | .066 | .03 | .273 |

| Hispanic vs White | .09 | <.001 | .05 | .011 | .04 | .045 |

| Age in Years | .07 | <.001 | −.05 | .027 | −.05 | .024 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −.02 | .409 | <.01 | .850 | −.01 | .599 |

| Wave 1 PTSS | .09 | <.001 | .07 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 1 Delinquency | .16 | <.001 | .15 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 1 Violence Exposure | .30 | <.001 | .29 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.04 | .087 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.05 | .033 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.10 | .056 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.07 | .034 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.16 | .043 | ||||

| Wave 2 PTSS | ||||||

| African American vs White | .07 | .001 | .03 | .167 | .03 | .281 |

| Hispanic vs White | .06 | .021 | .01 | .564 | .01 | .725 |

| Age in Years | .10 | <.001 | .01 | .746 | .01 | .531 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | .15 | <.001 | .10 | <.001 | .11 | <.001 |

| Wave 1 Violence Exposure | .08 | <.001 | .08 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | .26 | <.001 | .33 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 1 PTSS | .47 | <.001 | .46 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | .05 | .167 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | .03 | .314 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | .35 | <.001 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | .15 | .003 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | .49 | <.001 | ||||

| Wave 2 Delinquency | ||||||

| African American vs White | .13 | .007 | −.02 | .741 | −.04 | .448 |

| Hispanic vs White | .08 | .028 | −.01 | .788 | −.02 | .599 |

| Age in Years | .08 | .023 | −.11 | .002 | −.09 | .018 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −.14 | <.001 | −.01 | .898 | <.01 | .952 |

| Wave 1 Violence Exposure | .02 | .700 | <.01 | .952 | ||

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | .16 | <.001 | .19 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 1 Delinquency | .61 | <.001 | .59 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | .08 | .071 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | <.01 | .957 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | .03 | .694 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | .02 | .692 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | .20 | .048 | ||||

| Wave 3 New Violence Exposure | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| African American vs White | .10 | <.001 | .03 | .087 | .02 | .577 |

| Hispanic vs White | .06 | .003 | .01 | .457 | .01 | .679 |

| Age in Years | .01 | .643 | −.04 | .045 | −.05 | .021 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −.03 | .143 | −.03 | .137 | −.06 | .014 |

| Wave 2 PTSS | .19 | <.001 | .24 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 2 Delinquency | .19 | <.001 | .16 | .003 | ||

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | .25 | <.001 | .19 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.08 | .012 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.04 | .121 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.24 | .002 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.10 | .011 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.34 | <.001 | ||||

| Wave 3 PTSS | ||||||

| African American vs White | .01 | .238 | −.04 | .051 | −.07 | .052 |

| Hispanic vs White | .03 | .601 | −.01 | .558 | −.02 | .343 |

| Age in Years | .07 | .016 | .01 | .749 | −.02 | .624 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | .12 | <.001 | .02 | .247 | −.02 | .321 |

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | −.08 | <.001 | −.18 | .048 | ||

| Wave 3 New Violence Exposure | .14 | <.001 | .08 | <.001 | ||

| Wave 2 PTSS | .62 | <.001 | .69 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.09 | .001 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.10 | .005 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.40 | .001 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.21 | .006 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.57 | <.001 | ||||

| Wave 3 Delinquency | ||||||

| African American vs White | .13 | <.001 | .06 | .124 | .03 | .441 |

| Hispanic vs White | .04 | .321 | −.01 | .855 | −.02 | .666 |

| Age in Years | .08 | .040 | .04 | .338 | .03 | .507 |

| Gender (Female vs Male) | −.13 | <.001 | −.05 | .136 | −.08 | .036 |

| Wave 2 New Violence Exposure | −.01 | .873 | −.04 | .413 | ||

| Wave 3 New Violence Exposure | .11 | .003 | .07 | .058 | ||

| Wave 2 Delinquency | .52 | <.001 | .52 | <.001 | ||

| Caregiver Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.11 | .026 | ||||

| Adolescent Perception of Neighborhood Safety | −.04 | .304 | ||||

| Head of Household Marital Status (Married vs Not) | −.32 | <.001 | ||||

| Head of Household Education | −.22 | <.001 | ||||

| Poverty (High vs Low Income) | −.49 | <.001 | ||||

Note: PTSS-Posttraumatic stress symptoms. Estimates were derived from a cross-lagged and auto-regressive path model that is depicted in Figure 1. Model 1 examined racial/ethnic differences in violence exposure and symptoms while controlling for only age and gender. Model 2 examined violence exposure and symptom cascades as potential mediators of racial/ethnic differences. Model 3 added familial and contextual variables to Model 2 in order to examine the degree to which these variables explain disparities in the initiation of violence exposure and symptom cascades.

Model 2: Cross-lagged and Autoregressive Paths

The cross-lagged and autoregressive path model examining mediation across violence exposure cascades evidenced good model fit across most indicators, χ2 = 260.38, df = 13, p <.001, CFI = .97, RMSEA = .08, WRMR = 1.21. After controlling for cross-lagged and autoregressive paths, African American youth no longer evidenced disparities in new polyvictimization in both Waves 1 and 2 (p-values > .05) and Hispanic youth only evidenced disparities in new polyvictimization at Wave 2 (β = .05, p = .011), but not Wave 3 (β = −.01, p = .855). With regard to symptoms, only Wave 1 differences in delinquency remained significant (p-values < .001). Table 2 contains additional information on results for baseline outcomes and Table 3 contains additional information on outcomes at follow-up waves.

At both Wave 2 and Wave 3, new violence exposure was positively predicted by violence exposure, PTSS, and delinquency from the previous wave (p-values < .05). Wave 1, 2, and 3 PTSS were positively predicted by concurrent wave and prior wave violence exposure (p-values < .01) and prior wave PTSS (p-values < .001). Delinquency at Wave 1, 2, and 3 was positively predicted by concurrent-wave violence exposure (p-values < .05) and for Waves 2 and 3, prior wave delinquency (p-values < .001), but not prior wave violence exposure (p-values > .05).

Tests of Indirect Effects in Violence Exposure Cascades.

For both African American and Hispanic adolescents, Wave 1 initial polyvictimization accounted for significant portions of racial/ethnic differences in past-year polyvictimization at Wave 2 (p-values < .001), while Wave 2 differences in past-year polyvictimization accounted for significant portions of racial/ethnic differences in past-year polyvictimization at Wave 3 (p-values < .01). Further, the double mediational path leading in which racial/ethnicity predicted Wave 1 polyvictimization, Wave 1 lifetime polyvictimization predicted Wave 2 past-year polyvictimization, and Wave 2 past-year polyvictimization predicted Wave 3 past-year polyvictimization was also significant for both African American and Hispanic adolescents (p-values < .001).

Examining the role of delinquency in violence disparities, for both Waves 2 and 3, prior wave differences in delinquency appeared to account for a significant portion of differences in past-year polyvictimization (p-values < .001). Additionally, prior wave delinquency and violence exposure evidenced significant indirect effects indirect effects of double and triple mediation (e.g., race/ethnicity predicts Wave 1 polyvictimization, which in turn predicts Wave 1 delinquency, which in turn predicts Wave 2 polyvictimization; p-values < .05). Results with PTSS evidenced a different pattern in that the only significant indirect effects with PTSS involved another mediator that was directly predicted by race/ethnicity (e.g., race/ethnicity predicting polyvictimization at Wave 1, which in turn predicts Wave 1 PTSS, which in turn predicts Wave 2 polyvictimization; p-values < .05). Table 4 outlines direct and indirect pathways and their results.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects (IEs) with and without Family and Neighborhood Mediators of Violence Exposure Cascades.

| IEs of Hispanic Disparities in Wave 2 Violence Exposure | β | p |

|---|---|---|

| Before Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 2) | .05 | <.001 |

| After Adding Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .05 | <.001 |

| Only Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | <.001 |

| Only non-Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | .061 |

| IEs of African American Disparities in Wave 2 Violence Exposure | β | p |

| Before Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 2) | .07 | <.001 |

| After Adding Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .08 | <.001 |

| Only Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .04 | <.001 |

| Only non-Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | .070 |

| IEs of Hispanic Disparities in Wave 3 Violence Exposure | β | p |

| Before Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 2) | .05 | <.001 |

| After Adding Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .05 | .002 |

| Only Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | <.001 |

| Only non-Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | .049 |

| African American Disparities in Wave 3 Violence Exposure | β | p |

| Before Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 2) | .07 | <.001 |

| After Adding Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .09 | <.001 |

| Only Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .03 | <.001 |

| Only non-Family and Neighborhood Mediators (Model 3) | .02 | .045 |

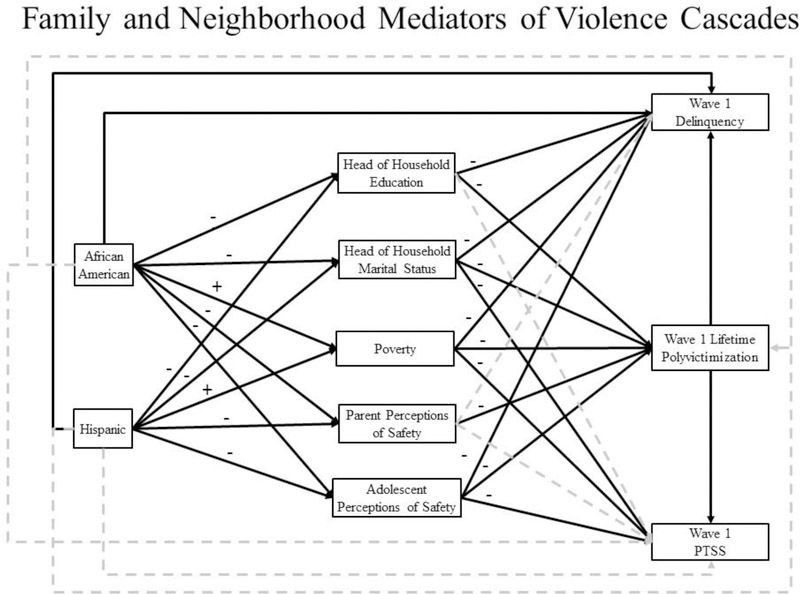

Model 3: Familial and Neighborhood Variables as Mediators of Violence Cascade Disparities

After adding head of household education, head of household marital status, household poverty, and caregiver and adolescent perceptions of neighborhood safety, the model evidenced good fit across most indicators, χ2 = 186.17, df = 13, p <.001, CFI = .98, RMSEA = .06, WRMR = 0.69. Among specific paths, no racial/ethnic differences in violence exposure remained significant (p-values > .05). Examining differences in PTSS, violence exposure and delinquency across each wave, only racial/ethnic differences in Wave 1 delinquency remained significant (p-values < .001). All significant cross-lagged and auto-regressive paths from Model 2 remained significant (p-values < .001). All five familial and neighborhood variables evidenced significant differences, with African American youth and their caregivers reporting greater rates of poverty (p-values < .001) and lower levels of perceived neighborhood safety reported by caregivers and adolescents, lower rates of head of household marriage, and lower head of household education compared with White adolescents and their caregivers (p-values < .001). All five of these variables negatively predicted Wave 1 polyvictimization (p-values < .05). Adolescent perception of safety, head of household education and marital status, and household poverty predicted delinquency (p-values < .01). Similarly, adolescent perception of neighborhood safety, head of household marital status, and household poverty predicted Wave 1 PTSS (p-values < .01). The same pattern emerged for indirect effects of familial and neighborhood variables. Each accounted for a significant portion of racial/ethnic differences in Wave 1 polyvictimization (p-values < .05), while each variable except caregiver perception of neighborhood safety accounted for racial/ethnic differences in Wave 1 delinquency (p-values < .05). Sensitivity analyses were also conducted to examine the robustness of the single mediator effects against potential unexamined confounders. These analyses indicated that a large effect of a confounder would need to be observed before the indirect effects were no longer significant (rho ≥ .35). Individual paths predicting Wave 1 outcomes are contained in Table 2 and Table 3 contains individual paths predicting Wave 2 outcomes. Indirect effects with and without familial and neighborhood variables are in Table 4.

Discussion

Results from the current study largely supported study hypotheses and provide two novel findings regarding violence exposure disparities. First, racial/ethnic differences in violence exposure appear to increase across adolescence and these differences are largely accounted for by prior exposure to violence and its related symptoms, which indicates racial/ethnic disparities occur in a cascade of violence exposure across adolescence. Second, familial and neighborhood context variables appear to account for initial differences in violence exposure and this mediational relation appears to account for racial/ethnic disparities in violence exposure cascades across adolescence. In other words, neighborhood and familial factors appear to be at least markers of contexts that give rise to racial/ethnic disparities in violence exposure that are then subsequently perpetuated by a cascade of violence exposure and related symptoms.

The current manuscript is among the first to simultaneously and prospectively examine how familial and neighborhood differences account for an intersecting combination of racial/ethnic disparities in violence exposure, PTSS, and delinquency. Within these mediational pathways, violence exposure disparities appear to accelerate across adolescence as a result of their impact on mental health outcomes that operate as a feedback loop to further increase violence exposure risk. This conforms with prior work suggesting that prior violence exposure26–32, PTSS27,29,34,35, and delinquency46,47 increase the risk of future violence victimization. These results further expand on prior work by suggesting that these cascades may initiate with differences across neighborhood and familial resource contexts. Importantly, several of these contextual factors have been previously linked to systemic disparities, such as discriminatory housing policies72. Future studies may benefit from more direct assessments of these factors that may explain the contextual and familial differences.

Strengths, Limitations and Future Directions

Notable strengths from the current study include the use of longitudinal data and thorough screening of posttraumatic stress symptoms and violence exposure; however, findings from the current study are tempered by multiple limitations, particularly those related to assessment methodologies. The study relied exclusively on self-report of delinquent behavior, which may result in underreporting by adolescents. Additionally, PTSS may only serve as a marker for many of the mechanisms that lead directly to violence exposure risk. Similarly, neighborhood contextual factors were assessed through caregiver and adolescent report of perceived neighborhood characteristics. Such variables may be inflated by caregiver or adolescent symptomology that may artificially inflate their relations with adolescent variables and PTSS, in particular. Attrition was also significant in this study, but is similar to other longitudinal, phone-based interview studies and multiple techniques were employed to reduce potential biases. Results may not generalize to clinical populations or populations outside the U.S., as the current sample represents a general sample of U.S. adolescents. Moving forward, research may benefit from examining the degree to which the mediational paths found here are equal across racial/ethnic groups. While beyond this scope of this study, which focused on mediational effects, the differential risk of future violence exposure may provide a fuller picture of racial/ethnic disparities.

Conclusion

The current research is among the first to demonstrate that violence exposure cascades longitudinally mediate racial/ethnic disparities in expanding violence exposure across adolescence. Similarly, this study provides novel findings that these disparities may be initiated by earlier differences in neighborhood and familial context differences. Such results are critical for understanding racial/ethnic disparities in violence exposure and related outcomes. This research also provides evidence supporting the need for additional treatment and prevention efforts targeting African American and Hispanic adolescents in order to address expanding disparities in violence exposure and related symptoms. These efforts may need to include both community intervention efforts to reduce violence and improve conditions associated with violence as well as expansion of evidence-based treatments for reducing PTSS and delinquent behavior.

Figure 2.

This shows the potential mediational roles of head of household education, head of household marital status, poverty, caregiver perceptions of safety, and caregiver perceptions of community order and resources. Poverty and head of household marital status were categorical variables with dichotomous coding reflecting poverty (1) vs. non-poverty (0) groups and married (1) vs. not married (0). For all other variables, higher scores represent higher degrees of the construct represented (e.g., higher perceived safety). Positive relations are indicated by ‘+’ and negative relations are indicated by ‘−’ above each significant path. Significant paths are bolded in black and non-significant paths are gray. Additionally, gender and age were also examined as covariates but are not displayed here. The cross-lagged and auto-regressive relationships between violence and related symptoms at follow-up assessments (i.e., the violence and symptom cascades) were also included in this model, but are not displayed here in order to enhance clarity in the mediational roles here. The autoregressive and cross-lagged configuration is the same as the one depicted in Figure 1.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1R01 HD046830-01. Preparation of the manuscript was supported in part by Grant R01DA025616-04S1 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health (NIH) and 1U54GM115458-01 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, NIH. Views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the funding agencies acknowledged. Data will be made available upon request to the corresponding author and original study principal investigators (Kilpatrick & Saunders).

Footnotes

Alternate models were examined in which the direction of the paths were reversed (e.g., Wave 2 PTSS predicting Wave 2 violence exposure), but evidenced poorer model fit. Additionally, models with correlations (i.e., non-directional paths) between all within-wave variables did not significantly improve model fit. Thus, the model with predictive paths from violence exposure to within-wave symptoms was retained.

References

- 1.Crouch JL, Hanson RF, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS. Income, race/ethnicity, and exposure to violence in youth: Results from the national survey of adolescents. J Community Psychol. 2000;28(6):625–641. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Hamby SL, Ormrod R. Polyvictimization: Children’s Exposure to Multiple Types of Violence, Crime, and Abuse. OJJDP Juv Justice Bull. 2011;NCJ235504:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glaser J-P, Van Os J, Portegijs PJ, Myin-Germeys I. Childhood trauma and emotional reactivity to daily life stress in adult frequent attenders of general practitioners. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61(2):229–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oscea Hawkins A, Kmett Danielson C, de Arellano MA, Hanson RF, Ruggiero KJ, Smith DW, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Ethnic/racial differences in the prevalence of injurious spanking and other child physical abuse in a national survey of adolescents. Child Maltreat. 2010;15(3):242–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.López CM, Andrews AR III, Chisolm AM, de Arellano MA, Saunders B, Kilpatrick DG. Racial/ethnic differences in trauma exposure and mental health disorders in adolescents. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2017;23(3):382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hatch SL, Dohrenwend BP. Distribution of Traumatic and Other Stressful Life Events by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, SES and Age: A Review of the Research. Am J Community Psychol. 2007. December 1;40(3–4):313–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews AR III, Jobe-Shields L, Lopez CM, Metzger IW, de Arellano MA, Saunders B, Kilpatrick DG. Polyvictimization, income, and ethnic differences in trauma-related mental health during adolescence. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50(8):1223–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Poly-victimization: A neglected component in child victimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2007;31(1):7–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts AL, Gilman SE, Breslau J, Breslau N, Koenen KC. Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychol Med. 2011;41(01):71–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy AC, Bybee D, Greeson MR. Examining cumulative victimization, community violence exposure, and stigma as contributors to PTSD symptoms among high-risk young women. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(3):284–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Polyvictimization and trauma in a national longitudinal cohort. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(01):149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodman E, Samuelson S, Wilson H. Does psychopathology mediate the pathway from childhood violence exposure to substance use in low-income, urban African American girls? Compr Psychiatry. 2013;54(8):e22–e23. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kilpatrick DG, Ruggiero KJ, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL. Violence and risk of PTSD, major depression, substance abuse/dependence, and comorbidity: results from the National Survey of Adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(4):692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schiff M, Plotnikova M, Dingle K, Williams GM, Najman J, Clavarino A. Does adolescent’s exposure to parental intimate partner conflict and violence predict psychological distress and substance use in young adulthood? A longitudinal study. Child Abuse Negl. 2014;38(12):1945–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goodwin RD, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Childhood abuse and familial violence and the risk of panic attacks and panic disorder in young adulthood. Psychol Med. 2005;35(06):881–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Norman RE, Byambaa M, De R, Butchart A, Scott J, Vos T. The long-term health consequences of child physical abuse, emotional abuse, and neglect: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11):e1001349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Pub; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: sociological contributions. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(1_suppl):S15–S27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop DM, Leiber MJ. Racial and ethnic differences in delinquency and justice system responses. Oxf Handb Juv Crime Juv Justice. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fader JJ, Kurlychek MC, Morgan KA. The color of juvenile justice: Racial disparities in dispositional decisions. Soc Sci Res. 2014;44:126–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santiago CD, Wadsworth ME, Stump J. Socioeconomic status, neighborhood disadvantage, and poverty-related stress: Prospective effects on psychological syndromes among diverse low-income families. J Econ Psychol. 2011;32(2):218–230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J. Neighborhood, Family and Individual Influences on School Physical Victimization. J Youth Adolesc. 2013. October 1;42(10):1596–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baglivio MT, Wolff KT, Epps N, Nelson R. Predicting Adverse Childhood Experiences: The Importance of Neighborhood Context in Youth Trauma Among Delinquent Youth. Crime Delinquency. 2017. February 1;63(2):166–188. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea S, Ahern J, Nandi A, Tracy M, Beard J, Vlahov D. Urban neighborhood poverty and the incidence of depression in a population-based cohort study. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(3):171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain S, Buka SL, Subramanian SV, Molnar BE. Neighborhood Predictors of Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration in Young Adulthood: A Multilevel Study. Am J Public Health. 2010. September;100(9):1737–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casey EA, Nurius PS. Trauma exposure and sexual revictimization risk: Comparisons across single, multiple incident, and multiple perpetrator victimizations. Violence Women. 2005;11(4):505–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ullman SE, Najdowski CJ, Filipas HH. Child sexual abuse, post-traumatic stress disorder, and substance use: Predictors of revictimization in adult sexual assault survivors. J Child Sex Abuse. 2009;18(4):367–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coid J, Petruckevitch A, Feder G, Chung W-S, Richardson J, Moorey S. Relation between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimisation in women: a cross-sectional survey. The Lancet. 2001. August 11;358(9280):450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Lifetime sexual victimization and poor risk perception: Does emotion dysregulation account for the links? J Interpers Violence. 2012;0886260512441081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boney-McCoy S, Finkelhor D. Prior victimization: A risk factor for child sexual abuse and for PTSD-related symptomatology among sexually abused youth. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19(12):1401–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barnes JE, Noll JG, Putnam FW, Trickett PK. Sexual and Physical Revictimization Among Victims of Severe Childhood Sexual Abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2009. July;33(7):412–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Widom CS, Czaja SJ, Dutton MA. Childhood victimization and lifetime revictimization. Child Abuse Negl. 2008. August;32(8):785–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(3):491–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortier MA, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL, Peugh J, DeNardi KA, Gaffey KJ. Severity of child sexual abuse and revictimization: The mediating role of coping and trauma symptoms. Psychol Women Q. 2009;33(3):308–320. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Milan S, Zona K, Acker J, Turcios-Cotto V. Prospective Risk Factors for Adolescent PTSD: Sources of Differential Exposure and Differential Vulnerability. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2013. February 1;41(2):339–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith DW, Davis JL, Fricker-Elhai AE. How Does Trauma Beget Trauma? Cognitions about Risk in Women with Abuse Histories. Child Maltreat. 2004. August 1;9(3):292–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Soler-Baillo JM, Marx BP, Sloan DM. The psychophysiological correlates of risk recognition among victims and non-victims of sexual assault. Behav Res Ther. 2005. February 1;43(2):169–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Messman-Moore TL, Brown AL. Risk Perception, Rape, and Sexual Revictimization: A Prospective Study of College Women. Psychol Women Q. 2006. June 1;30(2):159–172. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Curry LA, Youngblade LM. Negative affect, risk perception, and adolescent risk behavior. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2006. September 1;27(5):468–485. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meier MH, Slutske WS, Arndt S, Cadoret RJ. Impulsive and callous traits are more strongly associated with delinquent behavior in higher risk neighborhoods among boys and girls. J Abnorm Psychol. 2008;117(2):377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.White JL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bartusch DJ, Needles DJ, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Measuring impulsivity and examining its relationship to delinquency. J Abnorm Psychol. 1994;103(2):192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(6):545–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miller HV. Correlates of delinquency and victimization in a sample of Hispanic youth. Int Crim Justice Rev. 2012;1057567712444922. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wood J, Foy DW, Layne C, Pynoos R, James CB. An examination of the relationships between violence exposure, posttraumatic stress symptomatology, and delinquent activity: An “ecopathological” model of delinquent behavior among incarcerated adolescents. J Aggress Maltreatment Trauma. 2002;6(1):127–147. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Ng-Mak DS. Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. J Community Psychol. 2003;31(5):489–512. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Begle AM, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011. July 1;36(7):682–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lambert SF, Ialongo NS, Boyd RC, Cooley MR. Risk factors for community violence exposure in adolescence. Am J Community Psychol. 2005;36(1–2):29–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krohn MD, Schmidt NM, Lizotte AJ, Baldwin JM. The impact of multiple marginality on gang membership and delinquent behavior for Hispanic, African American, and white male adolescents. J Contemp Crim Justice. 2011;27(1):18–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fridrich AH, Flannery DJ. The effects of ethnicity and acculturation on early adolescent delinquency. J Child Fam Stud. 1995;4(1):69–87. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Swendsen J, Burstein M, Case B, Conway KP, Dierker L, He J, Merikangas KR. Use and Abuse of Alcohol and Illicit Drugs in US Adolescents: Results of the National Comorbidity Survey–Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012. April 1;69(4):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. J Adolesc Health. 2012. February;50(2):154–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2017: Overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. 2018; [Google Scholar]

- 53.Age limits and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health. 2003. November;8(9):577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cloitre M, Stolbach BC, Herman JL, van der Kolk B, Pynoos R, Wang J, Petkova E. A developmental approach to complex PTSD: Childhood and adult cumulative trauma as predictors of symptom complexity. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(5):399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menting B, Van Lier PA, Koot HM, Pardini D, Loeber R. Cognitive impulsivity and the development of delinquency from late childhood to early adulthood: Moderating effects of parenting behavior and peer relationships. Dev Psychopathol. 2016;28(1):167–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cisler JM, Amstadter AB, Begle AM, Resnick HS, Danielson CK, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. A prospective examination of the relationships between PTSD, exposure to assaultive violence, and cigarette smoking among a national sample of adolescents. Addict Behav. 2011;36(10):994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kilpatrick DG, Saunders BE. Prevalence and consequences of child victimization: Results from the National Survey of Adolescents, final report. Wash DC US Dep Justice Off Justice Programs [Internet]. 1997. [cited 2017 Mar 30]; Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/abstractdb/AbstractDBDetails.aspx?id=181028

- 58.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA, Hamby SL. Measuring poly-victimization using the Juvenile Victimization Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(11):1297–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Turner HA, Finkelhor D, Ormrod R. Poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38(3):323–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. Lifetime assessment of poly-victimization in a national sample of children and youth. Child Abuse Negl. 2009;33(7):403–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang M-C, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, George DT, Heilig M. Impact of Multiple Types of Childhood Trauma Exposure on Risk of Psychiatric Comorbidity Among Alcoholic Inpatients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012. June 1;36(6):1099–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.de Arellano MA, Andrews AR, Reid-Quiñones K, Vasquez D, Doherty LS, Danielson CK, Rheingold A. Immigration Trauma among Hispanic Youth: Missed by Trauma Assessments and Predictive of Depression and PTSD. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2017;E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cisler JM, Begle AM, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Danielson CK, Saunders BE, Kilpatrick DG. Exposure to interpersonal violence and risk for PTSD, depression, delinquency, and binge drinking among adolescents: Data from the NSA-R. J Trauma Stress. 2012. February 1;25(1):33–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders B, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: data from a national sample. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(1):19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Freedy JR, Pelcovitz D, Resick PA, Roth S, van der Kolk B. The posttraumatic stress disorder field trial: evaluation of the PTSD construct: criteria A through E In: Widiger T, Frances A, Pincus HA, Ross R, First M, Davis W, Kline M, editors. DSM-IV Sourceb. New York: American Psychiatric Press; 1998. p. 803–844. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Elliott DS, Huizinga D. Social class and delinquent behavior in a national youth panel: 1976–1980. Criminology. 1983;21(2):149–177. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Elliott DS, Ageton SS, Huizinga D, Knowles BA, Canter RJ. The prevalence and incidence of delinquent behavior: 1976–1980. National estimates of delinquent behavior by sex, race, social class, and other selected variables. Boulder CO Behav Res Inst [Internet]. 1983. [cited 2017 Sep 14]; Available from: https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/abstractdb/AbstractDBDetails.aspx?id=128841

- 68.Annual update of the HHS poverty guidelines. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. Report No.: Fed Regist 74:8373–8375. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model Multidiscip J. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sterne JAC, White IR, Carlin JB, Spratt M, Royston P, Kenward MG, Wood AM, Carpenter JR. Multiple imputation for missing data in epidemiological and clinical research: potential and pitfalls. BMJ. 2009. June 29;338:b2393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li C-H. Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behav Res Methods. 2016. September 1;48(3):936–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lichter DT, Parisi D, Taquino MC. The geography of exclusion: Race, segregation, and concentrated poverty. Soc Probl. 2012;59(3):364–388. [Google Scholar]