Abstract

A study was conducted to determine the enzymatic kinetic parameters Vmax, KM, and intrinsic clearance (CLint) for the hepatic in vitro production of aflatoxin B1-dihydrodiol (AFB1-dhd) from aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) in four commercial poultry species, ranging in sensitivity to AFB1 from highest (ducks) to lowest (chickens). Significant but small differences were seen for Vmax, while large significant differences were observed for KM. However, the largest inter-species differences were observed for the CLint parameter, with ducks being extraordinarily efficient in converting AFB1 into AFB1-dhd. Since AFB1-dhd is considered the metabolite responsible for the acute toxic effects of AFB1, the high hepatic production of AFB1-dhd from AFB1 in ducks is the possible biochemical explanation for the extraordinary high sensitivity of this poultry species to the adverse effects of AFB1.

Subject terms: Oxidoreductases, Multienzyme complexes

Introduction

Since the discovery of aflatoxins1 after the turkey “X” disease outbreak that killed over 100,000 turkey poults in Britain in 19602, it has been known that there are extremely large differences in sensitivity to aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) among commercial poultry species. The sensitivity to the acute effects of AFB1, expressed as LD50 values, ranges from 0,4 mg/kg in day-old ducklings3 to 6,8 mg/kg in day-old chicks4. The minimum dietary concentration of AFB1 capable of affecting growth in ducks, turkeys, chickens and laying hens is about 50, 200, 500 and 5000 ng/kg when exposed to the toxic diets for 3 to 4 weeks5. The 100-fold difference between ducks and laying hens reflects the extreme tolerance to aflatoxins in adult chickens and the large sensitivity in ducks. Chickens even grow better when there are aflatoxins in their diet6, whereas ducks are so sensitive that they were used as a biological assay for testing feedstuffs7, prior to the development of the modern analytical techniques for aflatoxins.

To become a toxic compound, AFB1 requires biotransformation by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP). Several AFB1 metabolites from mammalian and avian CYPs have been identified including aflatoxins M1, B2a, P1 and Q1, and the electrophilic unstable AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide (AFBO)8. The epoxide can alkylate RNA in vitro9 as well as the N7 position of guanine residues in DNA, forming irreversible adducts10; these adducts eventually cause the transversion G → T at codon 249 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocytes11, leading to hepatic cancer. Chronic exposure to AFB1 causes hepatocellular carcinoma not only in humans but also in such species as rats, primates and ducks8. The AFB1 metabolite responsible for the acute toxic effects of AFB1 has not been clearly identified but one possible candidate is the AFB1-exo-8,9-dihydrodiol (AFB1-dhd) that results from the nucleophilic trapping process of the AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide by water12,13, Fig. 1. AFB1-dhd has been shown to inhibit protein synthesis in vitro14 and its furofuran-ring-opened oxyanionic metabolite (AFB1-hydroxydialdehyde) can form lysine adducts in serum albumin in vivo15,16. Further, an aldehyde reductase with activity toward the AFB1 dialdehyde has been associated with decreased liver toxic effects in rats17. Therefore, the dihydrodiol/dialdehyde forms, which occur in equilibrium at physiological pH17, appear to be responsible for the cytotoxic acute effects of AFB1 exposure. For more than a decade our research group has been looking for biochemical differences in the hepatic biotransformation of AFB1 that could explain the in vivo differences in response to AFB1 among the main poultry species8,18–21. The present study shows for the first-time large differences in the enzymatic kinetic parameters of AFB1-dhd production in liver microsomes that could explain the different in vivo sensitivity to AFB1 of resistant (chickens and quail), sensitive (turkeys) and highly sensitive (ducks) poultry species.

Figure 1.

Biotransformation route of aflatoxin B1 into aflatoxin B1 exo-8,9-dihydrodiol. CYPs: Cytochrome P450. EPHX: Epoxide hydrolase.

Results

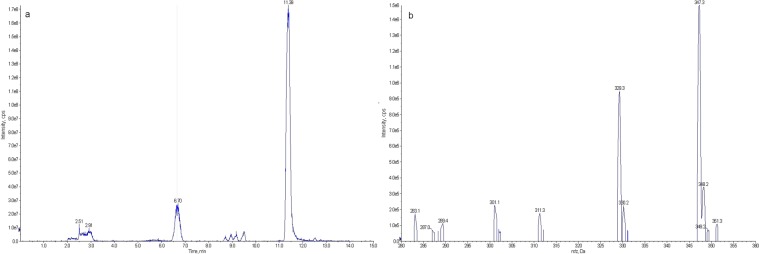

Due to the lack of a commercially available AFB1-dhd standard, a mass spectrometric analysis of the putative AFB1-dhd peak was conducted to determine its monoisotopic mass. The putative peak observed at 6.7 min Fig. 2a corresponded to a compound of 347 Da, which is consistent with the monoisotopic protonated mass of AFB1-dhd Fig. 2b.

Figure 2.

Identification of AFB1-dhd by HPLC-MS. (a) Chromatogram of a microsomal incubation showing the putative AFB1-dhd peak (tR = 6.70) and AFB1 (tR = 11.38). (b) Protonated monoisotopic masses found in the 6.70 min peak: the mass of 347.3 Da corresponds to the mass of AFB1-dhd whereas the mass of 329.3 Da (−18 Da) most likely corresponds to the dehydrated form of AFB1-dhd.

The enzymatic kinetic parameters for AFB1-dhd production by the four poultry species investigated are presented in Fig. 3. Chicken and quail enzymes did not saturate even at the highest AFB1 concentration evaluated (256 μM) Fig. 3a; however, turkey and duck enzymes seemed to become completely saturated with only 56 μM AFB1. The average values for the Vmax were the highest in Rhode Island Red chickens (11.2 ± 1.48 nmol of dhd-AFB1/mg protein/minute) and quail (9.57 ± 3.06 nmol of dhd-AFB1/mg protein/minute), while no differences (P > 0.05) were observed among Ross chickens, turkeys and ducks (5.75 ± 1.95, 5.84 ± 2.07 and 5.55 ± 1.33 nmol of dhd-AFB1/mg protein/minute, respectively) Fig. 3b. Rhode Island Red chicks had a higher Vmax value compared with Ross chickens. Regarding differences by sex, only quail and turkeys showed significant differences between males and females. The average values for KM showed large (P < 0.05) differences, with ducks presenting the lowest KM value by far (3.84 ± 1.01 μM of AFB1), followed by turkeys (49.33 ± 7.66 μM of AFB1), quail (77.79 ± 22.14 μM of AFB1) and the chicken breeds Rhode Island Red and Ross (112.5 ± 33.4 and 131.8 ± 26.2 μM of AFB1, respectively) Fig. 3c. No differences between males and females were found in any species for this enzyme kinetic parameter. Further, no differences between the chicken breeds were found either. Regarding the CLint parameter, very large differences among the species evaluated were observed, with ducks being extraordinarily efficient in converting AFB1 into AFB1-dhd compared to the other poultry species investigated Fig. 3d. CLint values for ducks, turkey, quail and Rhode Island Red and Ross chickens were 1.64 ± 1.00, 0.12 ± 0.04, 0.14 ± 0.08, 0.11 ± 0.02 and 0.05 ± 0.02 mL/mg protein/minute, respectively. No differences between males and females were observed.

Figure 3.

Enzyme kinetic parameters of microsomal in vitro AFB1-dhd production. (a) Saturation curve at AFB1 concentrations of 13.9 to 256 μM (incubations with duck microsomal fraction were done at AFB1 concentrations of 1.23 to 22.6 μM). (b) Maximal velocity (Vmax). (c) Michaelis-Menten constant (KM). (d) Intrinsic clearance (CLint; Vmax/KM). Total mean values with the same letter do not differ significantly. (*) Statistical differences by sex (P < 0.05) were calculated by the Kruskal-Wallis test.

Discussion

Since the discovery of aflatoxins in the early 1960’s it was observed that different animal species exhibit very different adverse effects upon exposure to the toxins. For example, ducklings, pigs and dogs die acutely at dietary concentrations that are well tolerated by humans, chickens and rats22–24. In some animal models, these differences can be explained through a differential hepatic biotransformation of AFB1. For instance, in mice and rats, differences in the ability to trap AFB1 with glutathione (GSH) ultimately determine the degree of AFB1-induced liver damage: while rats develop hepatocellular carcinoma upon chronic exposure to AFB1, mice are resistant. The reason for this differential response lies in the constitutive expression of high levels of an Alpha-class glutathione transferase (GST) that catalyzes the trapping of AFBO in the mouse that is only expressed at low levels in the rat25. Among poultry species exposed chronically to AFB1 the only one that develops liver cancer is the duck26; however, due to the short life-span of commercial poultry, it is actually the acute effects the ones that are more important. For more than a decade our research group has been searching for a biochemical explanation for the differences in susceptibility to AFB1 among the main poultry species. We have found that AFB1 is essentially biotransformed into aflatoxicol and AFB1-dhd by chicken, quail, turkey and duck liver microsomes and that at least four CYPs can bioactivate AFB1 into the epoxide in ducks, whereas CYP2A6 is the main cytochrome responsible for this reaction in chickens, quail and turkeys8,18–21. However, none of these findings could explain the extraordinarily high sensitivity of the duck compared to other poultry.

In the present study we investigated the in vitro kinetic constants Vmax and KM, as well as their ratio, also known as intrinsic clearance. Measurement of CLint has been used to predict the hepatic extraction of a compound27, and it is considered to be a measure of the total amount of enzyme that is coupled to the substrate and engaged in the conversion of the substrate into the product28, in other words it is a means to express enzyme efficiency29. Maximal velocity did not differ significantly between duck and turkey (sensitive species) or Ross chickens (highly resistant species); however, large significant differences in KM were seen among the poultry species studied. Duck presented the lowest value: almost 13 times lower that turkey, 20 times lower than quail and 30 times lower than the chicken breeds. The calculation of the CLint values revealed that duck liver microsomes clear AFB1 as AFB1-dhd at rates between 15 and 33 times higher than chickens. These values are due the low duck KM values for AFB1-dhd production, which means that duck CYPs require very low concentrations of AFB1 to reach maximal velocity. More tolerant or resistant species require higher amounts of AFB1 to reach Vmax, making their CYP enzymes a low performance biotransformation system. Based on these results we propose an order of AFB1 clearance as AFB1-dhd in the poultry species studied as follows: duck ⋙ quail > turkey > chicken (Ross), with values of 1.64, 0.14, 0.12 and 0.05 mL/mg/minute, respectively. In regard to differences between males and females we confirmed previous results obtained in our laboratory, where no significant differences were found by sex.

In summary, the present findings not only provide a biochemical explanation for the large differences in susceptibility to AFB1 between chickens and ducks, but also provide strong evidence that AFB1-dhd is the metabolite responsible for the acute toxicity of AFB1. We hypothesize that the large production of AFB1-dhd by the duck liver is the cause of the mortality and liver lesions observed with dietary concentrations that do not affect other poultry. Further, the large production of AFB1-dhd, which is in turn produced by the AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide, might be related to the fact that ducks are the only poultry species that develop hepatic cancer after AFB1 exposure.

Methods

Reagents

AFB2a, glucose 6-phosphate sodium salt, glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, nicotinamide dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), bicinchoninic acid solution (sodium carbonate, sodium tartrate, sodium bicarbonate and sodium hydroxide 0.1 N pH 11.25), copper sulphate pentahydrate, formic acid, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), sucrose, glycerol, and bovine serum albumin were from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Aflatoxin B1 was from Fermentek Ltd. (Jerusalem, Israel). Sodium chloride and magnesium chloride pentahydrate were purchased from Mallinckrodt Baker (Phillipsburg, NJ, USA). Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate and sodium phosphate dibasic anhydrous were from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Methanol, acetonitrile and water were all HPLC grade.

Microsomal fraction processing

Liver fractions were obtained from 12 healthy birds (6 males and 6 females) from each of the following species and age: seven-week old Ross and Rhode Island Red chickens (Gallus gallus ssp. domesticus), eight-week old turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), eight-week old quails (Coturnix coturnix japonica) and nine-week old Pekin ducks (Anas platyrhynchos ssp. domesticus). The birds were sacrificed by cervical dislocation, and their livers extracted immediately, washed with cold PBS buffer (50 mM phosphates, pH 7.4, NaCl 150 mM), cut into small pieces and stored at −70 °C until processing. The experiment was conducted following the welfare guidelines of the Poultry Research Facility and was approved by the Bioethics Committee, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Zootechnics, National University of Colombia, Bogotá D.C., Colombia (approval document CB-FMVZ-UN-033-18). Frozen liver samples were allowed to thaw, and 2.5 g were minced and homogenized for 1 minute with a tissue homogenizer (Cat X120, Cat Scientific Inc., Paso Robles, CA, USA) with 10 mL of extraction buffer (phosphates 50 mM pH 7.4, EDTA 1 mM, sucrose 250 mM). The homogenates were then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 30 minutes at 4 °C (IEC CL31R Multispeed Centrifuge, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). After this first centrifugation, the supernatants (approximately 10 mL) were transferred into ultracentrifuge tubes kept at 4 °C and centrifuged for 90 minutes at 100,000 × g (Sorval WX Ultra 100 Centrifuge, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). The resulting pellets (corresponding to the microsomal fraction) were resuspended in 3 mL of storage buffer (phosphates 50 mM pH 7.4, EDTA 1 mM, sucrose 250 mM, 20% glycerol), fractioned in microcentrifuge tubes and stored at −70 °C. An aliquot of each sample was taken to determine its protein content by using the bicinchoninic acid protein quantification method according to Redinbaugh and Turley30.

Microsomal incubations

Incubations were carried out in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes kept at 39 °C (the normal average avian body temperature) containing 5 mM glucose 6-phosphate, 0.5 I.U. of glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase, 0.5 mM NADP+, 1 μL of AFB1 in DMSO at concentrations ranging from 1.23 to 256 μM, and 5 μg of microsomal protein. All volumes were completed with incubation buffer (phosphates 50 mM pH 7.4, MgCl 5 mM, EDTA 0.5 mM), and the reaction stopped after 10 minutes with 250 μL of ice-cold acetonitrile. The stopped incubations were centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 minutes and 2 μL of a 1:10 dilution in mobile phase were analyzed by High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) as described below.

Chromatographic conditions (HPLC)

The production of AFB1-dhd in each incubation was quantitated in a Shimadzu Prominence system (Shimadzu Scientific Instruments, Columbia, MD, USA) equipped with a DGU-20A3R degassing unit, two LC-20AD pumps, a SIL-20ACHT autosampler, a CTO-20A column oven, an SPD-20AV UV-Vis detector, an RF-20AXS fluorescence detector, and a CBM-20A bus module, all controlled by “LC Solutions” software. The chromatography was carried out on an Alltech Alltima HP C18, 150 mm × 3.0 mm (Alltech Associates Inc., Deerfield, IL, USA) kept at 40 °C. The mobile phase was a linear gradient of solvent A (water − 0.1% formic acid) and B (acetonitrile:methanol, 1:1–0.1% formic acid), as follows: 0 min: 25% B, 1 min: 25% B, 10 min: 60% B, 10.01 min: 25% B, and 17 min: 25% B. The flow rate was 0.4 mL/min and the fluorescence detector was set at excitation and emission wavelengths of 365 nm and 425 nm, respectively. The in-vial concentration of AFB1-dhd was quantitated using an external standard of AFB2a, since these two compounds share identical spectral properties9. Further, the monoisotopic protonated mass of AFB1-dhd was determined by HPLC-MS by means of a 3200 QTrap mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Toronto, Canada) using a thermospray ionization probe in positive mode and the following settings: probe voltage: 4,800 V, declustering potential: 140 V, entrance potential: 10 V, curtain gas value: 30, collision energy: 81 V and collision cell exit potential: 5 V.

Statistical analysis

The enzymatic parameters KM and Vmax were determined by non-linear regression using the Marquardt method adjusting the data to the Michaelis-Menten enzyme kinetics using the equation: v = Vmax[S]/KM + [S], where v is the enzyme reaction velocity, [S] represents substrate concentration, Vmax represents maximal velocity and KM represents the Michaelis-Menten constant. Intrinsic clearance (CLint) was calculated as the ratio Vmax/KM. Inter-species differences in enzymatic kinetic parameters were determined by using the Kruskal-Wallis test, while nonparametric multiple comparisons were made by using the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner method. All analyses were performed using the Statistical Analysis System software31.

Acknowledgements

Departamento Administrativo de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación, COLCIENCIAS, Convocatoria 647 “Doctorados Nacionales 2014”, Bogotá D.C., Colombia, the International Foundation for Science, Stockholm, Sweden (Grant No. B-3094) and Diamir Ariza (Micotox Ltda., Bogotá D.C., Colombia) for the mass-spectrometric analysis.

Author Contributions

G.J.D. designed the experiments, secured the necessary funding to perform them, analyzed the data, wrote some sections of the article and revised it thoroughly. H.W.M. designed and conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote some sections of the article and revised all references.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Gonzalo J. Diaz and Hansen W. Murcia contributed equally.

References

- 1.van der Zijden ASM, et al. Aspergillus flavus and turkey X disease: Isolation of crystalline form of a toxin responsible for turkey X disease. Nat. 1962;195:1060–1062. doi: 10.1038/1951060a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blount WP. Turkey “X” disease. Turkeys. 1961;9:52–77. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nesbitt BF, O’Kelly J, Sargeant K, Sheridan A. Aspergillus flavus and turkey X disease: Toxic metabolites of aspergillus flavus. Nat. 1962;195:1062–1063. doi: 10.1038/1951062a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith JW, Hamilton PB. Aflatoxicosis in the broiler chicken. Poult. Sci. 1970;49:207–215. doi: 10.3382/ps.0490207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diaz, G. J. Toxicología de las micotoxinas y sus efectos en avicultura comercial. In press (Editorial Acribia, 2019).

- 6.Diaz GJ, Calabrese E, Blaint R. Aflatoxicosis in chickens (gallus gallus): An example of hormesis? Poult. Sci. 2008;87:727–732. doi: 10.3382/ps.2007-00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Armbrecht BH, Fitzhugh OG. Mycotoxins II: The biological assay of aflatoxin in peking white ducklings. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1964;6:421–426. doi: 10.1016/S0041-008X(64)80007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz, G. J. & Murcia, H. W. Biotransformation of aflatoxin B1 and its relationship with the differential toxicological response to aflatoxin in commercial poultry species. In Aflatoxins: Biochemistry and Molecular Biology (ed. Guevara-Gonzalez, R. G.) 3–20, https://www.intechopen.com/books/aflatoxins-biochemistry-and-molecular-biology/biotransformation-of-aflatoxin-b1-and-its-relationship-with-the-differential-toxicological-response- (Intech Publishing, 2011).

- 9.Swenson DH, Miller JA, Miller EC. 2,3-dihydro-2,3-dihydroxy-aflatoxin B1: An acid hydrolysis product of an RNA-aflatoxin B1 adduct formed by hamster and rat liver microsomes in vitro. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1973;53:1260–1267. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(73)90601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guengerich FP, et al. Activation and detoxication of aflatoxin B1. Mutat. Res. 1998;402:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0027-5107(97)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aguilar F, Hussain SP, Cerutti P. Aflatoxin B1 induces de transversion of G → T in codon 249 of the p53 tumor suppressor gene in human hepatocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1993;90:8586–8590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson WW, Harris TM, Guenguerich FP. Kinetics and mechanism of hydrolysis of aflatoxin B1exo-8,9-epoxide and rearrangement of the dihydrodiol. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8213–8220. doi: 10.1021/ja960525k.. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Josephy PD, Guengerich FP, Miners JO. “Phase I” and “Phase II” drug metabolism: Terminology that we should phase out. Drug Metab. Rev. 2005;37:575–580. doi: 10.1080/03602530500251220.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neal GE, Judah DJ, Stirpe F, Patterson DSP. The formation of 2,3-dihydroxy-2,3-dihydro-aflatoxin B1 by the metabolism of aflatoxin B1 by liver microsomes isolated from certain avian and mammalian species and the possible role of this metabolite in the acute toxicity of aflatoxin B1. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1981;58:431–437. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(81)90095-8.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabbioni G, Skipper PL, Büchi G, Tannenbaum SR. Isolation and characterization of the major serum albumin adduct formed by aflatoxin B1in vivo in rats. Carcinog. 1987;8:819–824. doi: 10.1093/carcin/8.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guengerich FP, Arneson KO, Williams KM, Deng Z, Harris TM. Reaction of aflatoxin B1 oxidation products with lysine. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2002;15:780–792. doi: 10.1021/tx010156s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hayes JD, Judah DJ, Neal GE. Resistance to aflatoxin B1 is associated with the expression of a novel aldo-keto reductase which has catalytic activity towards a cytotoxic aldehyde-containing metabolite of the toxin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3887–3894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lozano MC, Diaz GJ. Microsomal and cytosolic biotransformation of aflatoxin B1 in four poultry species. Br. Poult. Sci. 2006;47:734–741. doi: 10.1080/00071660601084390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz JG, Murcia HW, Cepeda SM. Bioactivation of aflatoxin B1 by turkey liver microsomes: responsible cytochrome p450 enzymes. Br. Poult. Sci. 2010;51:828–837. doi: 10.1080/00071668.2010.528752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diaz JG, Murcia HW, Cepeda SM. Cytochrome p450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of aflatoxin B1 in chickens and quail. Poult. Sci. 2010;89:2461–2469. doi: 10.3382/ps.2010-00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz JG, Murcia HW, Cepeda SM, Boermans JH. The role of selected cytochrome p450 enzymes on the bioactivation of aflatoxin B1 by duck liver microsomes. Avian Pathol. 2010;39:279–285. doi: 10.1080/03079457.2010.495109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newberne PM, Butler WH. Acute and chronic effects of aflatoxin on the liver of domestic and laboratory animals: A review. Cancer Res. 1969;29:236–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ngindu A, et al. Outbreak of acute hepatitis caused by aflatoxin poisoning in kenya. The Lancet. 1982;319:1346–1348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(82)92411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patterson DSP. Metabolism as a factor in determining the toxic action of the aflatoxins in different animal species. Food Cosmet. Toxicol. 1973;11:287–294. doi: 10.1016/S0015-6264(73)80496-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esaki H, Kumagai S. Glutathione-S-transferase activity towards aflatoxin epoxide in livers of mastomys and other rodents. Toxicon. 2002;40:941–945. doi: 10.1016/S0041-0101(02)00090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hetzel DJS, Hoffmann D, Van De Ven J, Soeripto S. Mortality rate and liver histopathology in four breeds of ducks following long term exposure to low levels of aflatoxins. Singapore Vet. J. 1984;8:6–14. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rane A, Wilkinson GR, Shand DG. Prediction of hepatic extraction ratio from in vitro measurement of intrinsic clearance. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1977;200:420–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Northrop DB. On the meaning of Km and V/K in enzyme kinetics. J. Chem. Educ. 1998;75:1153–1157. doi: 10.1021/ed075p1153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guengerich, F. P. Analysis and characterization of enzymes and nucleic acids relevant to toxicology. In Hayes’s Principles and Methods of Toxicology Sixth Edition (eds Hayes, A. W. & Kruger, C. L.) 1939, ISBN-13: 978-1842145364 (CRC Press, 2014).

- 30.Redinbaugh MG, Turley RB. Adaptation of the bicinchoninic acid protein assay for the use with microtiter plates and sucrose gradient fractions. Analytical Biochemistry. 1986;153:267–271. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(86)90091-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.SAS Institute Inc. Base SAS 9.4 procedures guide: Statistical procedures, second edition. www.support.sas.com/bookstore (2013).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.