Abstract

Objective

To investigate the usefulness of preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) based on mutated allele revealed by sequencing with aneuploidy and linkage analyses (MARSALA) for a pedigree with X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP).

Methods

One pathogenic mutation (c.494G > A) of the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) gene was identified in a pedigree affected by XLRP. Then, PGD was carried out for the couple, of which the wife was an XLRP carrier. Three blastocysts were biopsied and then MARSALA was performed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). Prenatal diagnosis was also carried out to confirm the PGD results.

Results

Three blastocysts were all unaffected. Then, one of the embryos was chosen randomly to be transferred, and the pregnancy was acquired successfully. The results of prenatal diagnosis were consistent with the PGD results. The fetus did not carry RPGR mutation (c.494G > A) and had normal chromosome karyotype. As a result, a healthy baby free of XLRP condition was born.

Conclusion

The PGD method based on MARSALA was established and applied to a family with XLRP successfully. MARSALA will be a valid tool, not only for XLRP families but also for families affected with other monogenetic disorders, to prevent transmission of the genetic disease from parents to offspring.

Keywords: X-linked retinitis pigmentosa, Preimplantation genetic diagnosis, RPGR, Next-generation sequencing, MARSALA

Introduction

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is a heterogeneous set of inherited retinal degenerative diseases affecting 1 in 3000–4000 people worldwide with many disease-causing genes and highly varied clinical consequences [1]. RP is characterized by progressive devolution of the retina resulting in progressive visual loss. Usually, disease duration of RP covers multiple decades. Symptoms include abnormal results of electroretinogram, night blindness, diminishing visual fields, and complete blindness ultimately. The mode of inheritance can be autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, or X-linked manner. To date, X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) accounts for 15% of all RP cases, and represents the most severe subtype of this disease [2, 3]. Among all the related genes, mutations in the retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR) gene and RP2 gene are the most common causes, accounting for over 80% of all XLRP cases [4, 5].

Since XLRP is a genetic disorder without effective treatment, prevention of birth of baby with XLRP is very important. Reproductive technologies including prenatal diagnosis and preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) are crucial methods to reduce the risk of birth of affected baby. PGD has been widely utilized to select unaffected embryo to avoid the transmission of genetic disorders since the first birth of PGD case in 1990 [6–8]. Recently, a new PGD method has been applied to clinics, called mutated allele revealed by sequencing with aneuploidy and linkage analyses (MARSALA), which combines PGD, preimplantation genetic screening (PGS), and linkage analysis in one-step next-generation sequencing (NGS) procedure, thereby increasing success rates of clinical pregnancy and live birth [9, 10]. In this study, we performed MARSALA-PGD for a XLRP carrier couple successfully. To our knowledge, this is the first application of MARSALA-PGD in XLRP, resulting in the birth of a healthy baby.

Materials and methods

Family history

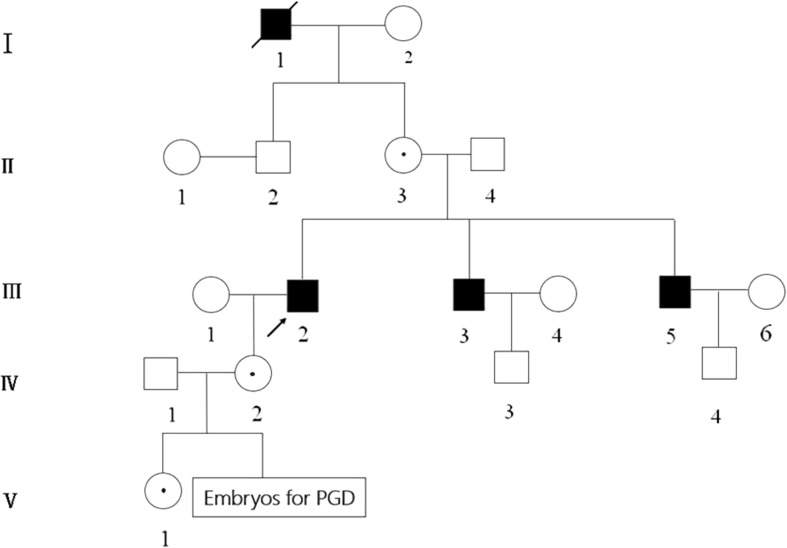

As shown in Fig. 1, the wife (IV2) has a family history of XLRP, whose father (III2) and two uncles (III3,5) suffered with typical XLRP symptoms as blindness and progressive loss of visual field. Molecular diagnosis of these affected individuals showed a mutation (c.494G > A) of the RPGR gene, which could be classified as pathogenic according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) classification principle. And the wife was confirmed to be heterozygous at that position, which indicated she was an XLRP carrier, at risk of giving birth to an affected offspring with XLRP. The daughter of the couple (V1) inherited the mutation from her mother. The informed consent form for PGD treatment was signed by the couple.

Fig. 1.

Pedigree of the family with XLRP. Squares and cycles indicate males and females, respectively. Filled symbols represent affected individuals; open symbols represent unaffected individuals; cycles with a dot represent female carriers. Arrow indicates the proband

Embryo biopsy

In this case, 3 matured oocytes at MII stage were collected after ovarian stimulation and then fertilized by intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI). All blastocysts were utilized for trophectoderm biopsy when the trophectoderm (TE) cell had herniated out of the zona pellucida on day 5 or 6 after fertilization. Biopsied TE cells were washed in PBS (with 0.1% HSA) and transferred to the PCR tube for whole genome amplification (WGA).

WGA and NGS

The whole genome from the biopsied TE cells was amplified with a single cell MALBAC Kit (Yikon Genomics Inc., China) according to the instructions. WGA products were reamplified using primers specific to the mutated region (Table 1). We incubated 8 ng of the MALBAC product from the biopsied cells. The PCR was carried out in a total volume of 50 μl with the following steps: 1 cycle of initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, and 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 40 s, annealing at 55 °C for 40 s, and elongation at 72 °C for 45 s, and an additional elongation at 72 °C for 10 min. Then, the PCR products were mixed with the WGA products for NGS at a low sequencing depth (0.1×). Sequencing library was constructed using the NGS TPM DNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (CWBIO Inc., China). The sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (USA). Following this procedure, the targeted point mutation and chromosome aneuploidy could be simultaneously analyzed in the same NGS run as published previously [9, 10].

Table 1.

Primers and PCR parameters used to amplify the mutated region of RPGR gene

| Fragment | Length (bp) | Forward primer (5′ → 3′) | Reverse primer (5′ → 3′) | Annealing (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPGR-E6 | 213 | GCTTCAGAGCCTGGCTACCT | ACAACATAGAAGTGGGAGATAAC | 55 |

Linkage analyses by MARSALA

To select suitable single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the X chromosome adjacent to the point mutation of patient, we sequenced the genomes of family members, including the disease-carrying wife, her daughter, and affected father, as well as the unaffected husband and the wife’s mother. All SNPs within 1 Mb upstream and 1 Mb downstream of the RPGR gene were called with sequencing depth > 10×. From these sequences, the SNP readouts at the adjacent positions allowed the identification of the disease carrying allele. And then we used a similar strategy to deduce whether the disease-carrying allele is present in each embryo by the informative SNPs readouts from the sequences of each embryo, with a 2× sequencing depth for each MALBAC-amplified DNA sample.

Results

Point mutation detection

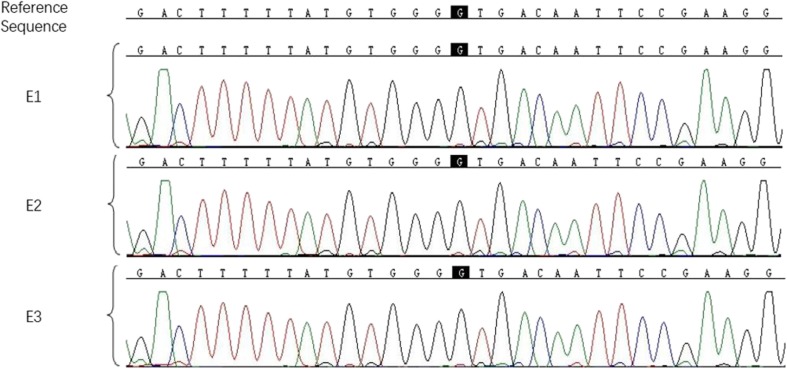

As previously described by Yan et al. [9], the targeted point mutation could be accurately detected by MARSALA. We also performed Sanger sequencing to confirm the MARSALA result. As shown in Fig. 2, all of the three embryos were free of the RPGR mutation (c.494G > A).

Fig. 2.

Sanger sequencing chromatographs of the three embryos. The mutation sites are shown in black background. All of the three embryos (E1,2,3) did not inherit the disease-causing mutation (c.494G > A)

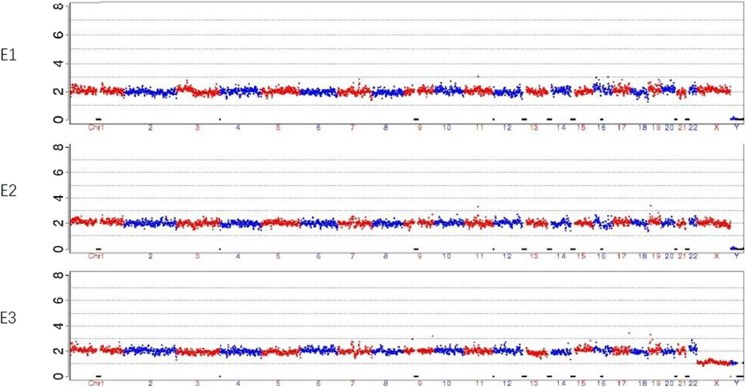

Chromosome aneuploidy screening

MARSALA allows simultaneous detection of both the point mutation and the chromosome aneuploidy in one NGS run. The copy number variations (CNV) data of all chromosomes for each embryo were presented in Fig. 3. All of the three embryos were identified to be normal.

Fig. 3.

CNVs of the three embryos at low sequencing depth of NGS. NGS analysis of the three embryos (E1,2,3) did not reveal any large CNVs or copy number aberrations

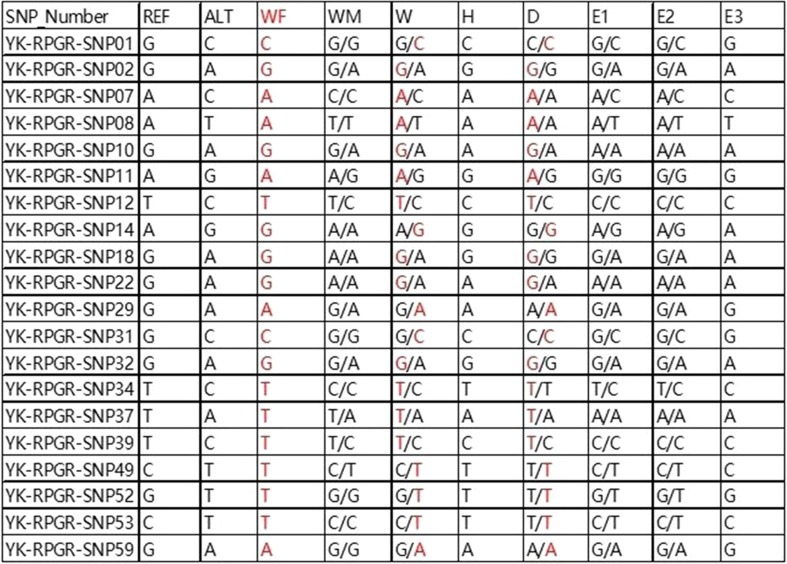

Linkage analysis

After sequencing the genomes of the family members, we adopted 20 SNPs to deduce whether embryos inherited the disease-carrying allele. We focused on the heterozygous SNPs in the X chromosome of the disease-carrying wife, the disease-carrying daughter, and unaffected husband. For instance, the wife was heterozygous A/C on SNP07, the unaffected husband was A/X, while the affected daughter was A/A. We could easily deduce that the allele with base A from her mother must be pathogenic. In the other words, the wife’s allele with base A was disease-causing allele and the allele with base C was wild-type allele. Then, we used this strategy to deduce whether the mutated allele is present in each embryo. It was shown by the results that E1, E2, and E3 all inherited base C from the mother, indicating free of the mutated allele. Figure 4 represents the whole results of linkage analysis based on SNPs. From the results, we could deduce that all of the three embryos did not inherit the maternal pathogenic mutation.

Fig. 4.

Results of linkage analysis of the three embryos. Twenty SNP markers were checked to identify disease-carrying allele in each embryo. None of the three embryos (E1,2,3) were identified as carrying the disease-associated allele. REF, the SNPs of reference allele; ALT, the SNPs of alternative allele; WF, wife’s father (affected individual); WM, wife’s mother; W, wife (carrier); H, husband; D, daughter (carrier). The red bases indicate that the SNPs link with mutant type

Clinical outcome

Based on the above results of MARSALA, all of the three embryos were suitable for transfer, as they were euploidy as well as unaffected with the mutation allele. E1 was transferred, and luteal phase supports were given routinely. Serum β-hCG level was measured at 14 days after embryo transfer. Ultrasound examination at 5 weeks after embryo transfer revealed a single intrauterine gestational sac with normal fetal heartbeat. The level obtained was consistent with a clinical pregnancy. Prenatal diagnosis was performed with Sanger sequencing and karyotype analysis using amniotic fluid cells at 18-week gestation, and the results (data not shown) were consistent with PGD results. A healthy baby girl free of the RPGR maternal mutation and chromosome abnormality was born on July 7, 2017. In one-year follow-up, the girl showed normal growth and development, and ophthalmological examinations were totally normal.

Discussion

XLRP represents the most severe clinical subtype of RP, with lacking effective treatment. For the nature of XLRP as a monogenic inherited disease, PGD is regarded as an ideal option for female carrier with fertility desire to reduce the risk of birth of affected baby.

In previous articles, PGD methods for single-gene disorder diagnosis were mainly carried out by PCR and linkage analysis based on short tandem repeats (STRs) [11, 12]. However, it has been reported that allele drop-out (ADO) and undetected recombination would lead to diagnosis failure and/or misdiagnosis of some cases [13, 14]. Furthermore, STR analysis usually needs to be tailored to the disorder and to the individual family under investigation, which is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Compared with STR analysis, SNP analysis provides much more markers (400–500 SNPs vs 3–8 STR markers) around the mutation, which improves the PGD accuracy [15]. Moreover, aneuploidy detection is considered to be requisite in PGD of monogenic diseases, since a high percentage of aneuploidy in human preimplantation embryos is well-documented and euploid embryos transfer would increase the pregnancy rate [16–18].

In recent years, PGD technology has been developed rapidly. MARSALA and karyomapping are the most representative PGD methods, and both of them can perform linkage analysis based on SNPs and detect aneuploidy simultaneously [9, 10, 17, 19, 20]. Compared with karyomapping methods, MARSALA can detect mutation directly by sequencing and indirectly by linkage analysis with multiple SNPs in one NGS step. Use of enough numbers of SNP markers close to target mutation is an available strategy to maximize the accuracy of identifying the wild-type or mutated allele, even if the direct mutation calling failed. On the other hand, if chromosome homologous recombination results in loss of linkage, the deduced results from the selected SNPs cannot be validated accurately by each other, then direct detection of the mutation sites can help to confirm the diagnosis and avoid the misidentification.

In addition, MARSALA can still correctly diagnose the embryos under the condition of the absence of suitable affected family members, by using the affected embryo as the proband [10]. The PGD result of each embryo can confirm the results of other embryos from the same couple, and the direct mutation detection and indirect linkage analysis also can be verified by each other. It can be said that it is a unique advantage of MARSALA.

MARSALA has already been applied in PGD for autosomal recessive disorder, autosomal dominant disorder, and X-linked recessive disorder, which has helped many couples successfully have their healthy babies free from the monogenetic diseases, such as beta thalassemia, spinal muscular atrophy, hereditary multiple exostoses, and X-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia [9, 10, 20]. In the present work, MARSALA was successfully established and applied to a family with XLRP for PGD to prevent the genetic transmission. To our knowledge, this is the first application of MARSALA-PGD in XLRP. It is expected that MARSALA would enable PGD for all kinds of monogenetic diseases with known pathogenic mutation with high precision, indicating that this method can be applied to clinics effectively.

Acknowledgements

We thank the family for their participation in this study.

Funding information

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (No. 2016J01589, No. 2018J01348).

Compliance with ethical standards

The couple signed informed consent forms for ICSI treatment, PGD, and follow-up. The protocols for this study were evaluated and approved by the Ethics Committee of Fuzhou General Hospital.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hamel C. Retinitis pigmentosa. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:40. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-1-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MU, Rahman MSU, Cao J, Yuan PX. Genetic characterization and disease mechanism of retinitis pigmentosa; current scenario. 3 Biotech. 2017;7(4):251. doi: 10.1007/s13205-017-0878-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anasagasti A, Irigoyen C, Barandika O, López de Munain A, Ruiz-Ederra J. Current mutation discovery approaches in retinitis pigmentosa. Vis Res. 2012;75:117–129. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murga-Zamalloa C, Swaroop A, Khanna H. Multiprotein complexes of retinitis pigmentosa GTPase regulator (RPGR), a ciliary protein mutated in X-linked retinitis pigmentosa (XLRP) Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;664:105–114. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1399-9_13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Megaw RD, Soares DC, Wright AF. RPGR: its role in photoreceptor physiology, human disease, and future therapies. Exp Eye Res. 2015;138:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2015.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Handyside AH, Kontogianni EH, Hardy K, Winston RM. Pregnancies from biopsied human preimplantation embryos sexed by Y-specific DNA amplification. Nature. 1990;344(6268):768–770. doi: 10.1038/344768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heijligers M, van Montfoort A, Meijer-Hoogeveen M, Broekmans F, Bouman K, Homminga I, Dreesen J, Paulussen A, Engelen J, Coonen E, van der Schoot V, van Deursen-Luijten M, Muntjewerff N, Peeters A, van Golde R, van der Hoeven M, Arens Y, de Die-Smulders C. Prenatal follow-up of children born after preimplantation genetic diagnosis between 1995 and 2014. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35:1995–2002. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1286-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulton A, Lewis S, Hui L, Halliday JL. Prenatal and preimplantation genetic diagnosis for single gene disorders: a population-based study from 1977 to 2016. Prenat Diagn. 2018;38:904–910. doi: 10.1002/pd.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan L, Huang L, Xu L, Huang J, Ma F, Zhu X, Tang Y, Liu M, Lian Y, Liu P, Li R, Lu S, Tang F, Qiao J, Xie XS. Live births after simultaneous avoidance of monogenic diseases and chromosome abnormality by next-generation sequencing with linkage analyses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(52):15964–15969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523297113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren Y, Zhi X, Zhu X, Huang J, Lian Y, Li R, Jin H, Zhang Y, Zhang W, Nie Y, Wei Y, Liu Z, Song D, Liu P, Qiao J, Yan L. Clinical applications of MARSALA for preimplantation genetic diagnosis of spinal muscular atrophy. J Genet Genomics. 2016;43(9):541–547. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2016.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vendrell X, Bautista-Llácer R, Alberola TM, García-Mengual E, Pardo M, Urries A, Sánchez J. Pregnancy after PGD for recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa inversa: genetics and preimplantation genetics. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28(9):825–832. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9601-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borgulova I, Putzova M, Soldatova I, Krautova L, Pecnova L, Mika J, Kren R, Potuznikova P, Stejskal D. Preimplantation genetic diagnosis of X-linked diseases examined by indirect linkage analysis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2015;116(9):542–546. doi: 10.4149/bll_2015_103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreesen J, Destouni A, Kourlaba G, Degn B, Mette WC, Carvalho F, Moutou C, Sengupta S, Dhanjal S, Renwick P, Davies S, Kanavakis E, Harton G, Traeger-Synodinos J. Evaluation of PCR-based preimplantation genetic diagnosis applied to monogenic diseases: a collaborative ESHRE PGD consortium study. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22(8):1012–8. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilton L, Thornhill A, Traeger-Synodinos J, Sermon KD, Harper JC. The causes of misdiagnosis and adverse outcomes in PGD. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(5):1221–1228. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altarescu G, Zeevi DA, Zeligson S, Perlberg S, Eldar-Geva T, Margalioth EJ, Levy-Lahad E, Renbaum P. Familial haplotyping and embryo analysis for preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD) using DNA microarrays: a proof of principle study. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30(12):1595–1603. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0044-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng Z, Zhao X, Xu B, Yao N. What should we focus on before preimplantation genetic diagnosis/screening. Arch Med Sci. 2018;14(5):1119–1124. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2018.72790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li G, Niu W, Jin H, Xu J, Song W, Guo Y, Su Y, Sun Y. Importance of embryo aneuploidy screening in preimplantation genetic diagnosis for monogenic diseases using the karyomap gene chip. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):3139. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21094-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Wei D, Zhu Y, Gao Y, Yan J, Chen ZJ. Rates of live birth after mosaic embryo transfer compared with euploid embryo transfer. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;36:165–172. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1322-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Handyside AH, Harton GL, Mariani B, Thornhill AR, Affara N, Shaw MA, Griffin DK. Karyomapping: a universal method for genome wide analysis of genetic disease based on mapping crossovers between parental haplotypes. J Med Genet. 2010;47(10):651–658. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.069971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu H, Shen X, Huang L, Zeng Y, Gao Y, Shao L, Lu B, Zhong Y, Miao B, Xu Y, Wang Y, Li Y, Xiong L, Lu S, Xie XS, Zhou C. Genotyping single-sperm cells by universal MARSALA enables the acquisition of linkage information for combined pre-implantation genetic diagnosis and genome screening. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(6):1071–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1158-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]