Ausborn J, Snyder AC, Shevtsova NA, Rybak IA, Rubin JE. State-dependent rhythmogenesis and frequency control in a half-center locomotor CPG. J Neurophysiol 119: 96–117, 2018. First published October 4, 2017; doi:10.1152/jn.00550.2017.

In the originally published version of this article, the time axis labeling was incorrect in panels C–H of Fig. 6, leading to a mismatch between the frequencies shown there and the correct frequencies indicated in the color coding in Fig. 6A. The correction of the time axis in Fig. 6, C–H does not affect any of the conclusions reported in the article.

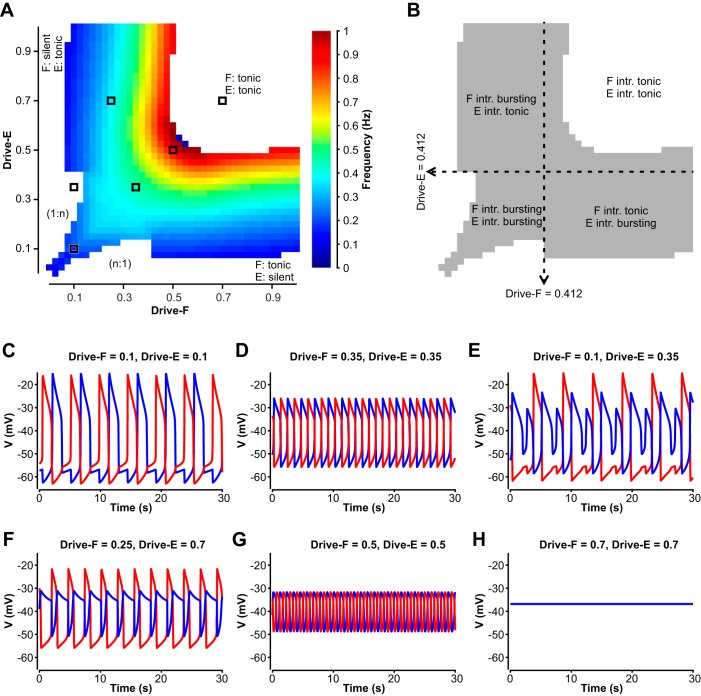

Fig. 6.

Activity regimes depend on drive in the reduced model. A: frequency heat map obtained by independently changing drives to the flexor and extensor half-centers. Only frequencies where the flexor and extensor are rhythmically active in strict alternation (1:1) are color coded. White areas correspond to nonphysiological regimes of burst alternation (1:n or n:1) (example shown in E) and to the states when the flexor and/or extensor are tonically active or silent (example for both tonic shown in H). B: the alternating (1:1) oscillations result from a wide range of drive combinations and underlying intrinsic activity regimes of the flexor and extensor units. Dashed lines indicate where the intrinsic activity state switches from bursting to tonic. C–H: example traces of flexor (red) and extensor (blue) units generated at drive levels indicated by black squares in A, showing network activity at low, symmetric drives demonstrating the gap between two active states (C); intermediate, symmetric drives (D); asymmetric drives yielding nonphysiological (1:n) bursting (E); asymmetric drives yielding network oscillations due to intrinsic bursting in the flexor half-center with the extensor half-center in a tonic mode (F); high, symmetric drives for which the network exhibits half-center oscillations, although both flexor and extensor are intrinsically tonic (G); high symmetric drive yielding tonic network activity (represented by sustained elevated voltage) (H).

In addition, simulations performed after publication led us to realize that Fig. 11, B and D were produced with an outdated parameter set. New figures were generated with the parameter set reported in the article and are qualitatively similar to the ones appearing in the original publication. In particular, the new figures still support the corresponding text in the article, which states that network frequency in this regime was not sensitive to changes in inhibition strength.

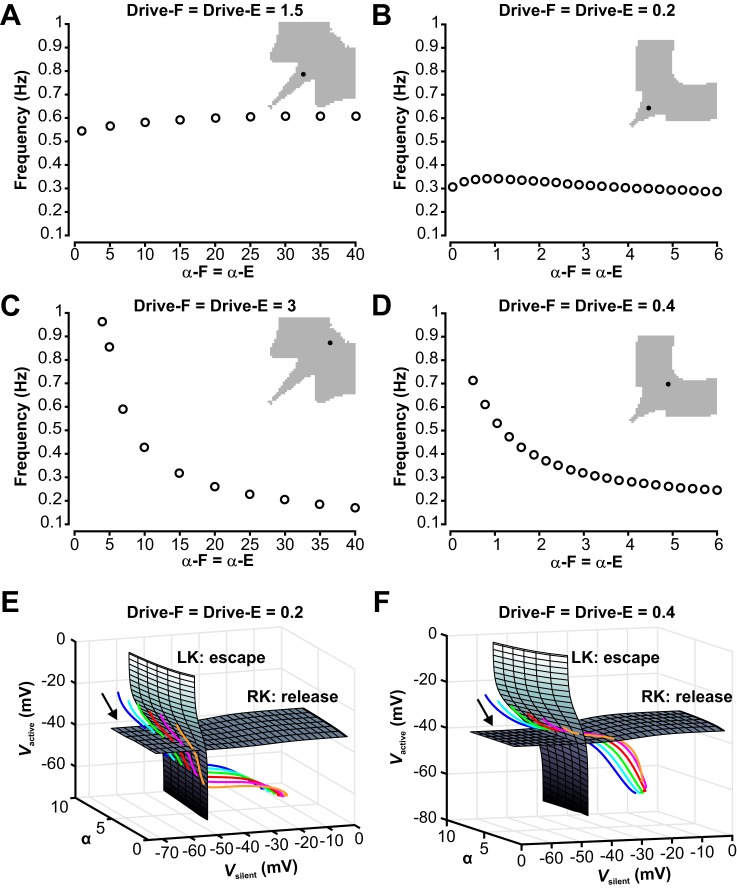

Fig. 11.

Dependence of oscillation frequency on the strength of mutual inhibition between the half-centers in the symmetric regime. A: in the symmetric regime with low drive to both half-centers, frequency is not sensitive to changes in the strength of the reciprocal inhibition for the population model. B: the reduced model also does not show strong frequency modulation with changing inhibition when drive is relatively low and transitions require release. C: the symmetric regime with high drive is highly sensitive to changes in inhibition for the population model. D: the reduced model shows a similarly strong frequency dependency on changes in inhibition when drive is relatively high and transitions occur by escape. E and F: surfaces of left (LK) and right (RK) knees, corresponding to transitions by escape and release, respectively, for the reduced model with low drive (0.2, E) and high drive (0.4, F). Colored curves are trajectories for various levels of inhibition strength α (orange, 1.5; pink, 2.5; red, 3.5; green, 4.5; cyan, 5.5; blue, 6.5). These evolve from upper left to lower right (arrows). E: with low drive, trajectories for all levels of α hit the RK surface before the LK surface, corresponding to transitions by release. F: with high drive, trajectories for all levels of α hit the LK surface before the RK surface, corresponding to transitions by escape.

The corrected figures appear below.