Abstract

Rotational grazing is a recommended practice for grazing livestock, but little is known about its benefits with respect to grazing horses. The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of continuous (CON) and rotational (ROT) grazing on forage nutrient composition and whether those concentrations influenced circulating glucose and insulin concentrations in the grazing horse. Twelve mature Standardbred mares were paired by age and weight and randomly assigned to 1 replicate of either a 1.5 ha cool-season grass CON or ROT system for a total of 3 mares in each system. Mares on CON were allowed to graze the entire system at all times, whereas mares on ROT were given access to a 0.4 ha pasture section and stress lot where they were confined during inclement weather and slow forage growth. Blood and feces from horses and forage from each system were sampled over one 24-h period in June, August, and October. Blood was assessed for plasma glucose (GLU) and serum insulin (INS), feces for pH, and forage for nutritional composition. Data were analyzed by ANOVA with repeated measures with significance set at P < 0.05. There were no treatment differences for water and ethanol soluble carbohydrates (WSC and ESC, respectively), starch, ADF, and NDF, but CP was lower in ROT compared to CON (P = 0.04). With respect to month, WSC were highest in June compared to August and October, whereas ESC were highest in June compared to only August. Starch was lower in October than in June and August. Concentrations of ADF and NDF were lowest in October compared to June and August. Crude protein was higher in October than June and August. Plasma GLU and serum INS were affected by season and time of day but not grazing system. For all horses, GLU was highest in August (105.6 ± 1.3 mg/dL), whereas INS was highest in October (0.21 ± 0.02 μg/L; P < 0.0001). Fecal pH only varied by season and was highest in August (7.06; P < 0.0001). Few consistent correlations between grazing systems were found with the exception of INS with ESC (R = 0.32 to 0.39; P < 0.04) and INS and GLU with ADF and NDF in August and October (R = −0.31 to −0.48; P < 0.04). In conclusion, grazing system did not affect the forage carbohydrate concentrations or GLU or INS in horses; however, season did have an effect on both forage nutrient content and glucose metabolism in horses.

Keywords: carbohydrate, continuous grazing, equine, glucose, insulin, rotational grazing

INTRODUCTION

Rotational grazing has long been a recommended practice over continuous grazing due to environmental and animal benefits observed in cattle production (Voisin, 1959; Heady, 1961). Heady (1970) described continuous grazing as unrestricted livestock access to the entire range throughout the whole grazing season, whereas rotational grazing regularly moves a group of animals from one pasture to another, allowing forage time to rest and regrow. Little research has been carried out on rotational grazing of horses in regards to forage and equine impacts.

Horses allowed to graze continuously tend to regraze short immature plants while leaving plants in eliminative areas to mature (Odberg and Francis-Smith, 1976). Perennial cool-season grasses store reserve soluble carbohydrates (like sugars and fructans) in the base of the stem (White, 1973), so the repeated close grazing observed in continuously grazed pastures theoretically exposes horses to these regions high in soluble carbohydrates. However, taller swards in clipped pastures have been shown to have higher soluble carbohydrates (including starch) than short swards (Siciliano, 2015). White (1973) concluded that grazing can be more detrimental to pastures than clipping due to animals’ selective grazing patterns. Proper rotational grazing should leave a sufficient amount of ungrazed forage to allow for quick recovery and high productivity.

Data are scarce as to how grazing management of horse pastures affects soluble carbohydrates concentrations of forages. The objective of this study was to investigate the effects of continuous and rotational grazing on the nutritional composition of forages and their effects on plasma glucose and insulin concentrations and fecal pH in the horses. We hypothesized that taller grasses in the rotational grazing system would have higher fiber and lower sugar and starch concentrations than the continuously grazed grasses, which would reduce the glycemic and insulinemic responses, therefore creating a more neutral fecal pH in rotationally grazed horses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The use of animals in this project was approved by the Rutgers University’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol #04-005. The study was conducted at the Rutgers University Ryders Lane Best Management Practice Demonstration Horse Farm in New Brunswick, NJ, on June 10 to 11 (spring), August 12 to 13 (summer), and October 14 to 15 (fall) of 2015 as a companion study to Kenny (2016).

Grazing Systems

Two 1.5 ha continuous grazing systems (CON) and two 1.5 ha rotational grazing systems (ROT) were developed in 2013 with horses assigned to the systems on August 1, 2014. All systems were seeded with “Jesup” MaxQ novel endophyte tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea; Pennington Seed, Madison, GA) at 7.9 kg/ha, “Camas” Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) at 12.9 kg/ha, and “Potomac” orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata) at 8.2 kg/ha (both from Chamberlin & Barclay, Cranbury, NJ). Each CON was equipped with a water source, shade shelter, and hay feeders. Each ROT was equipped with a 0.16 ha stress lot (dry lot) enclosed with a permanent wood fence that contained a run-in shed, automatic waterer, and hay feeders. Additionally, each ROT was connected to 4 smaller 0.35 ha (0.86 acre) pastures separated by 3-strand electric tape in fiberglass posts. Throughout the project, recommended pasture management practices were followed as they relate to each system (Foulk et al., 2004; Burk et al., 2011). Specifically, for the ROT system, horses were grazed when forage was taller than 15.2 cm and removed from pasture when reached 7.6 cm (Henning et al., 2000; Undersander et al., 2002).

Horses

Twelve mature (14 ± 2 yr) Standardbred mares (initial weight: 535.8 ± 14.2 kg, initial body condition score: 6.1 ± 0.3) were used for this study. Mares were paired by age and weight and randomly assigned to either a CON or ROT for a total of 3 mares in each system and a stocking density of 0.52 ha per horse. Mares remained on the systems permanently since August 2014 with the exception of being stalled overnight prior to sampling, for routine pre-veterinary care, or when fertilizing fields. Mares on CON had access to the full grazing area 24 h/d. Prior to each trial, ROT horses were grazing at least 8 d continuously and they grazed the same pasture within their replicated system for each of the 3 seasonal trials.

Sampling

Prior to each trial, mares were individually stalled overnight and offered water and moderate quality mixed grass hay (Table 1) in order to obtain a baseline sample from each horse the following morning. Sampling of blood, feces, and forage was performed every 4 h starting at 0800; horses were placed back in their respective pastures and sampling continued to the following morning for a total of 7 sample times.

Table 1.

Nutrient composition of hay (DM basis) provided overnight prior to each sampling period in June, August, and October1

| Nutrient2 | June | August | October |

|---|---|---|---|

| DM, % | 91.4 | 93.5 | 90.7 |

| DE, Mcal/kg | 2.12 | 1.83 | 2.2 |

| WSC, % | 14.8 | 4.1 | 7.9 |

| ESC, % | 7.3 | 3.8 | 6.7 |

| Starch, % | 0.4 | 1.0 | 0.5 |

| ADF, % | 39.6 | 49.0 | 37.6 |

| NDF, % | 61.9 | 70.2 | 55.4 |

| CP, % | 9.3 | 8.2 | 14.4 |

1Analyses were performed by Equi-Analytical, Inc., Ithaca, NY.

2WSC, water soluble carbohydrates; ESC, ethanol soluble carbohydrates.

Blood

Indwelling jugular catheters with extension sets were inserted and secured in each horse between 0530 and 0800 on the first day of the study. Following catheterization, baseline blood samples were taken at 0800 and then at 1200, 1600, 2000, 0000, 0400, and 0800 the following day. To take samples, 10 cc of waste was removed from the extension set, 40 cc of whole blood was removed, and then 10 to 20 cc of heparinized saline flush was inserted into the extension set. Whole blood was immediately transferred into Vacutainer tubes containing either EDTA or sodium heparin for collection of plasma or an empty tube for collection of serum. Tubes containing a coagulant were inverted several times. All blood tubes were placed on ice and transported to the lab (approximately 5 min drive) immediately after each sample collection. For the collection of plasma, whole blood was centrifuged at 3,700 rpm for 5 min. For the collection of serum, whole blood was allowed to sit at room temperature for 45 min prior to being centrifuged at 3,700 rpm for 10 min. Plasma and serum were harvested from the glass tubes, placed in microcentrifuge tubes, and stored at −80 °C until analysis. Plasma glucose (GLU) was analyzed using a colorimetric assay (Glucose C-2, Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA) and serum insulin (INS) by enzyme-linked immunoassay (Insulin ELISA, Mercodia, Winston-Salem, NC).

Forage

Forage was also sampled at each of the 7 sample periods in each trial to evaluate the diurnal patterns of carbohydrate concentrations. Forage in ROT was hand clipped to a height of 10.2 cm at all sample times. Forage in CON was sampled just above ground level to reflect the grazing pattern of the horses in that system. The 0800 baseline samples were randomly selected in the entire grazing area. The remaining forage samples were taken in areas where the horses were observed grazing at the time of sampling. For each forage sample 8 to 12 different sites were collected and combined for 1 individual sample in each replicated pasture. In the event that horses were resting in loafing lots or under shade shelters, forage was sampled in areas where they last grazed. Forage was immediately stored on dry ice and shipped to a commercial laboratory (Equi-Analytical, Inc., Ithaca, NY) for nutrient analysis including DM, DE, CP, ADF, NDF, water soluble carbohydrates (WSC), ethanol soluble carbohydrates (ESC), starch, calcium (Ca), and phosphorous (P) using standard wet chemistry for forage analysis.

Sward height was measured on the day of sampling (±4 d) by randomly walking and dropping a Styrofoam plate down a meter stick and recording the height where it rested on the forage, as described by Burk et al. (2011), with 100 measurements taken per CON and 25 measurements taken per each pasture section within ROT systems.

Weather

Weather data were tracked using the Rutgers Historical Monthly Station Data website (Rutgers Office of the State Climatologist, http://climate.rutgers.edu/stateclim_v1/monthlydata) for the New Brunswick station and included monthly average temperature and average precipitation. Daily average temperature, minimum and maximum temperature on the days of sampling, precipitation, and relative humidity were also tracked using the New Jersey Climate and Weather network data website (http://www.njweather.org/data).

Feces

Freshly voided feces were collected from each horse ±1 h around each collection time. Fecal samples were transported to the lab and analyzed for fecal pH. First, the pH meter was calibrated to a pH of 4 and 7. Next, 20 g of feces were added to 20 mL of dH2O in a 45-mL plastic conical tube and mixed thoroughly by vortexing. The pH probe was inserted and a reading was taken. The probe was cleaned, dried, and reinserted for a second reading. Duplicate samples were averaged for each horse at each sample time.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures using the MIXED procedure with the REPEATED statement in SAS (version 9.2, SAS Inst., Cary, NC). The model included sample time, month, grazing system treatment, and their interactions. A Tukey’s post hoc test was used to determine differences between the main effects. Relationships between variables within each month and grazing system were evaluated using Pearson’s product-moment correlation. Data were checked for normalcy using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Results were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as means ± standard error (SE).

RESULTS

Weather Data

Average temperature during the sampling days was similar to historical averages. While there was no precipitation on any of the sampling days, monthly precipitation was higher than historical average for the New Brunswick weather station by 6 and 2 cm in June and October, respectively, and 9 cm lower in August. Average temperature and relative humidity were different between each of the 3 sampling days (P < 0.0001; Table 2) with June being the warmest sampling day followed by August and then October. The sampling day in June also had the lowest variation of daytime vs. nighttime temperatures with only a 10 °C difference, whereas August and October were similar in variation with a 14.4 °C and 15.6 °C difference, respectively.

Table 2.

Average daily temperature, relative humidity, and precipitation1 during 24-h sampling periods compared to historical averages2

| Month | Temperature, °C | Relative humidity, % | Precipitation, cm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample day | Historical average | Daily range | Sample day | Historical average | Monthly total | Historical average | |

| June | 23.9 ± 0.2a | 21.0 | 18.3–28.3 | 62.8 ± 0.9a | NA | 15.6 | 9.9 |

| August | 22.7 ± 0.3b | 22.8 | 15.0–29.4 | 68.5 ± 1.1b | NA | 3.1 | 11.9 |

| October | 12.8 ± 0.3c | 12.9 | 5.0–20.6 | 74.7 ± 1.0c | NA | 10.9 | 8.9 |

1There was no precipitation on the sampling days; therefore, average monthly precipitation is presented and compared to monthly historical average.

2Weather data obtained for the New Brunswick Station through the Office of the New Jersey State Climatologist website (http://climate.rutgers.edu/stateclim_v1/monthlydata) and (https://www.njweather.org/data).

a–cMeans within column for Temperature and Relative humidity with unlike superscripts differ (P < 0.05)

Forage Sward Height

Average sward heights on each sample day within each system are presented in Table 3. Overall, sward heights were consistently higher in ROT than CON (P = 0.02), and within each of the months, June had the largest difference between ROT and CON (13.6 cm; P < 0.0001) followed by August (10.0 cm; P < 0.0001) and October (5.3 cm; P = 0.008). With respect to month, both grazing systems had the highest sward height in June followed by August and October (P < 0.0001).

Table 3.

Nutrient composition of forages (DM basis) in the rotational (ROT) and continuous (CON) grazing systems sampled in June, August, and October1,2

| Measure3 | Trt average | June | August | October | SEM | Trt4 | Month | Trt * month | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ROT | CON | ROT | Average | CON | ROT | Average | CON | ROT | Average | |||||

| SH, cm | 8.9a | 18.5b | 10.5c | 24.1d | 17.3e | 8.9c | 18.9d | 13.9f | 7.3c | 12.6d | 10.0g | 1.0 | 0.02 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| DM, % | 25.5 | 25.3 | 25.2 | 26.0 | 25.6 | 26.2 | 26.0 | 26.5 | 25.1 | 23.0 | 24.2 | 1.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| DE, Mcal/kg | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 0.02 | NS | NS | NS |

| WSC, % | 11.2 | 12.9 | 12.8 | 14.0 | 13.4e | 10.8 | 11.7 | 11.3f | 9.9 | 12.9 | 11.4f | 0.7 | NS | <0.0001 | NS |

| ESC, % | 8.0 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 9.6 | 9.4e | 7.6 | 8.6 | 8.1f | 7.3c | 10.2d | 8.7ef | 0.5 | NS | 0.01 | 0.008 |

| Starch, % | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.0 | 2.0e | 3.5c | 1.8d | 2.7f | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1g | 0.4 | NS | <0.0001 | 0.008 |

| ADF, % | 30.6 | 32.9 | 30.6c | 35.7d | 33.2e | 31.5 | 33.6 | 32.5e | 29.8 | 29.3 | 29.6f | 0.8 | NS | <0.0001 | 0.002 |

| NDF, % | 52.9 | 56.3 | 53.9c | 60.1d | 57.0e | 54.6 | 57.2 | 55.9e | 50.1 | 51.6 | 50.9f | 1.0 | NS | <0.0001 | 0.008 |

| CP, % | 20.8a | 16.5b | 18.5 | 12.7 | 15.6e | 16.1 | 15.1 | 17.6e | 24.0 | 21.7 | 22.9f | 0.7 | 0.04 | 0.0005 | NS |

1Analyses were performed by Equi-Analytical, Inc., Ithaca, NY.

2Data represent mean ± standard error of 7 samples taken throughout the day from each of the replicated systems for a total n = 14 per system per month.

3SH, sward height; WSC, water soluble carbohydrates; ESC, ethanol soluble carbohydrates.

4NS = not significant.

a,bWithin a row, means between treatments with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

c,dWithin a row, means between treatments within a month with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

e–gWithin a row, means between months with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

Forage Carbohydrates and Protein

Nutrient composition of forages (on a DM basis) in CON and ROT sampled in June, August, and October are shown in Table 3. Grazing horses within CON or ROT had no effect on concentrations of DM, DE, WSC, ESC, Starch, ADF, and NDF in forages. However, there was an effect of grazing system on CP whereby forages in ROT were consistently lower in CP compared to forages in CON (P = 0.04).

With respect to month, there was a main effect on WSC, ESC, starch, ADF, NDF, and CP (P < 0.01) and a month by treatment interaction for ESC, starch, ADF, and NDF (P < 0.002). Concentrations of WSC were highest in both systems in June compared to August and October (P < 0.0001), whereas ESC were highest in June compared to August only (P = 0.012). Within the month of October, forages in ROT were higher in ESC than CON (P = 0.008). Starch was highest in August followed by June and then October (P < 0.0001). Within the month of August, starch concentrations in CON were higher than in ROT (P = 0.008). Concentrations of ADF and NDF were similar in June and August, but were lower in October (P < 0.0001). Within June, forages in ROT were higher in ADF and NDF than CON (P = 0.008). Concentrations of CP in forages was similar in June and August, and peaked in October (P = 0.0005).

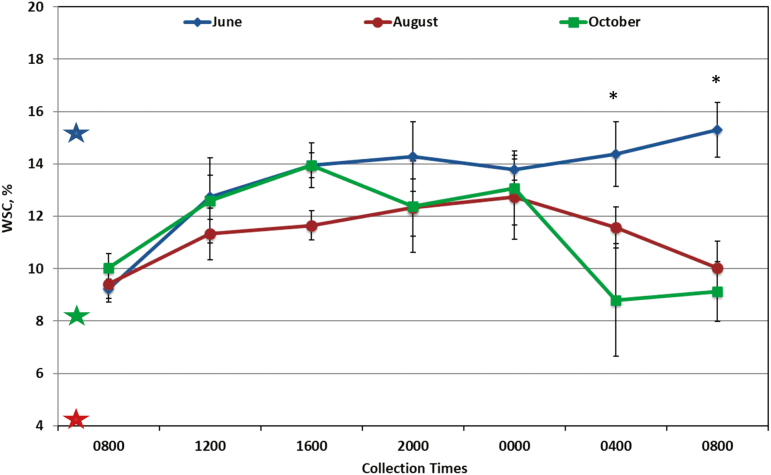

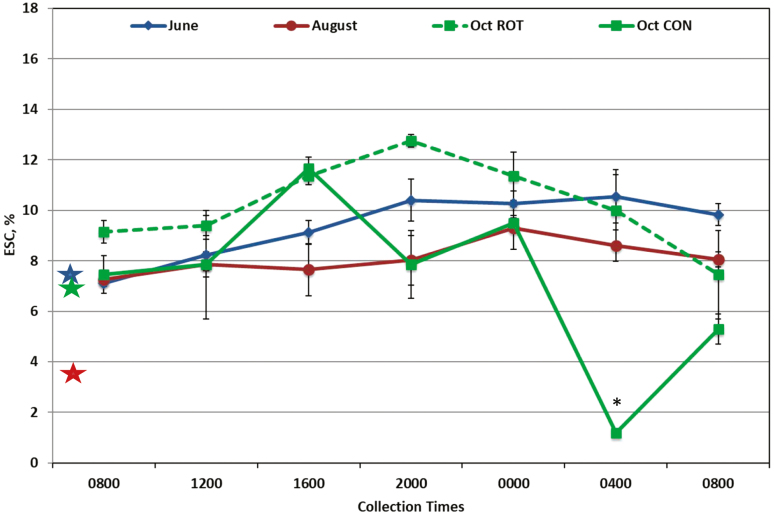

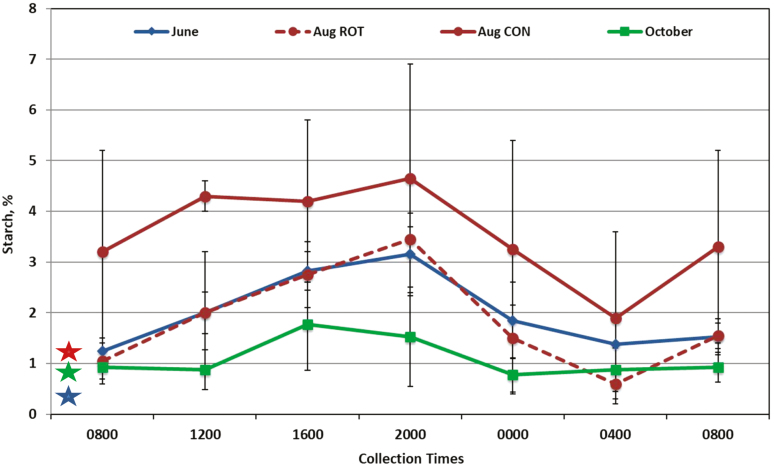

Time of day had an effect on concentrations of WSC (Fig. 1; P < 0.0001), ESC (Fig. 2; P = 0.001), starch (Fig. 3; P = 0.001), and NDF (data not shown; P < 0.03) in forages in both systems. Concentrations of WSC were lowest at both 0800 samples and 0400 compared to other sampling times (P < 0.01). Concentrations of ESC peaked at 0000 and were higher than 0400 and both 0800 samples (P < 0.04). Starch was lower at 0400 than 1600 and 2000 (P < 0.05). Concentrations of NDF were highest at 0800 and differed from the lowest concentration at 2000 (P = 0.05). Concentrations of ADF and CP did not differ by time of day. A time of day by month interaction was observed for WSC (P = 0.004), ESC (P = 0.0005), and NDF (P = 0.006). In October, the concentration of WSC was highest at 1600 and the final 0800 sample (P < 0.05; Fig. 1). In June, ESC remained higher at the final 2 sample times (0400 and 0800, P < 0.05; Fig. 2) than the previous samples, whereas in October, ESC was highest at 1600 compared to the last 2 samples at 0400 and 0800 (P < 0.05). For NDF concentrations, 0800 and 1200 was lower in October than in June and August (data not shown, P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Percentage of water soluble carbohydrates (WSC) in forage sampled in June, August, and October (n = 4 per sample time, treatments were combined due to no significant differences). Colored stars represent WSC in hay fed overnight to horses corresponding to the month of same color. Significance was found for sample and month (P < 0.0001); interactions were found for sample by month (P = 0.004) and treatment by sample (P = 0.036). * June is different than October (0800, June is different than both August and October) at P < 0.05.

Figure 2.

Percentage of ethanol soluble carbohydrates (ESC) in forage sampled in June, August (n = 4 per sample time, treatments were combined due to no significant differences), and October [rotational (ROT) and continuous (CON) treatments remain due to a significance (P = 0.01)]. Colored stars represent ESC in hay fed overnight to horses corresponding to the month of same color. Significance was found for sample (P = 0.001) and month (P = 0.01); interactions were found for sample by month (P = 0.0005) and treatment by month (P = 0.008). * Treatments were different within October at P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Percentage of starch in forage sampled in June and October (n = 4 per sample time, treatments were combined due to no significant differences) and August [rotational (ROT) and continuous (CON) treatments remain due to a significance (P = 0.05)]. Colored stars represent starch in hay fed overnight to horses corresponding to the month of same color. Significance was found for sample (P = 0.001) and month (P < 0.0001); interactions were found for treatment by month (P = 0.008).

Blood Glucose and Insulin

There was no effect of grazing system on GLU and INS concentrations in horses (Table 4). With respect to month, GLU was highest in horses in August (P < 0.0001), whereas INS was highest in horses in October (P < 0.0001). Within October, INS was higher in ROT horses compared to CON (P < 0.0001). Further investigation revealed 1 horse in ROT was hyperinsulinemic (>30 mU/L) in October, but did not have a change in weight or body condition or test as an outlier so was left in the analysis.

Table 4.

Mean plasma glucose, serum insulin, and fecal pH in horses grazing either a continuous (CON) or rotational (ROT) grazing system sampled in June, August, and October1

| Month | Trt average | June | August | October | SEM | Trt2 | Month | Trt * month | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CON | ROT | CON | ROT | Average | CON | ROT | Average | CON | ROT | Average | |||||

| Glucose, mg/dL | 96.6 | 94.6 | 92.1 | 89.1 | 90.6e | 106.0 | 105.3 | 105.6f | 91.8 | 89.4 | 90.6e | 1.5 | NS | < 0.0001 | NS |

| Insulin, μg/L | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.14 | 0.13e | 0.09 | 0.17 | 0.13e | 0.14a | 0.28b | 0.21f | 0.04 | NS | < 0.0001 | < 0.0001 |

| Fecal pH | 6.6 | 6.8 | 6.3a | 6.6b | 6.4e | 7.1 | 7.0 | 7.1f | 6.6 | 6.7 | 6.6g | 0.1 | NS | < 0.0001 | 0.005 |

1Data represent mean ± standard error of 7 samples taken throughout the day from each horse in the replicated systems for a total n = 42 per system per month.

2NS = not significant.

a,bWithin a row, means between treatments within a month with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

e–gWithin a row, means between months with different superscripts differ (P < 0.05).

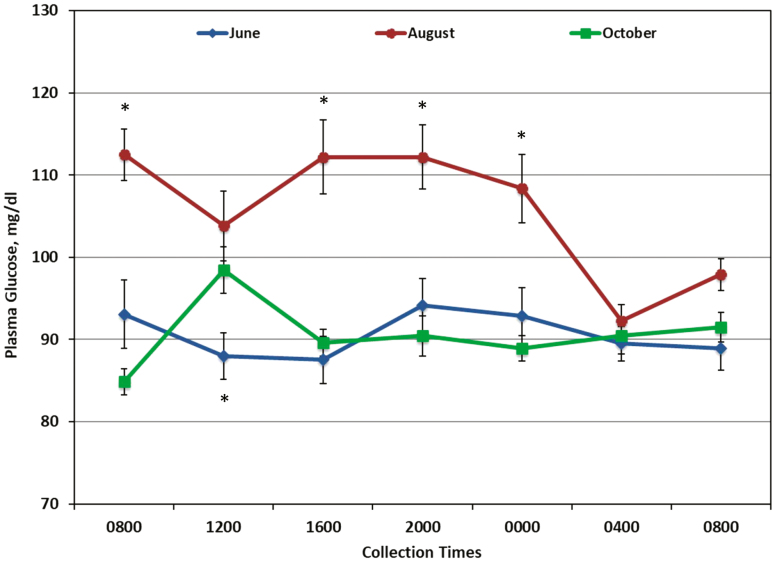

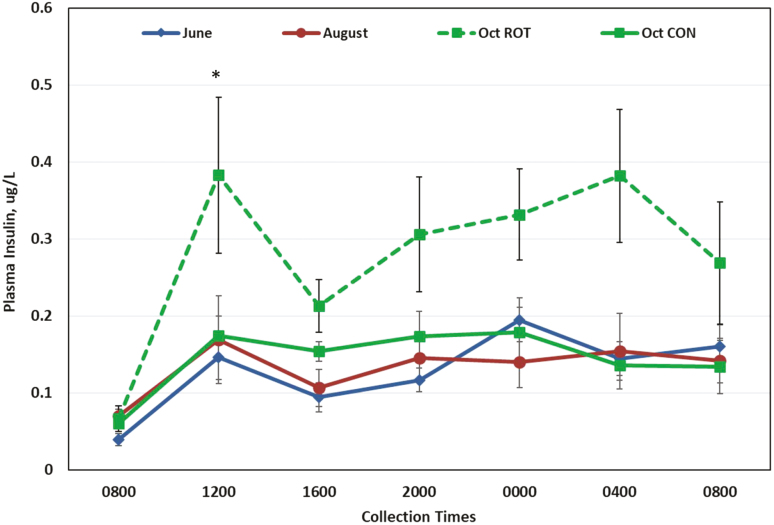

Time of day had an effect on circulating concentrations of GLU (P = 0.01, Fig. 4) and INS (P < 0.0001, Fig. 5) in horses. Plasma GLU was lowest at 0400 (90.8 ± 1.9 mg/dL; P < 0.015) compared to all other sample times with the exception of the last sample at 0800. Serum INS was lowest at the initial sample at 0800 (0.057 ± 0.028 μg/L; P < 0.0001), followed by 1600 (0.128 ± 0.028 μg/L; P < 0.015).

Figure 4.

Concentrations of plasma glucose of horses grazing a rotational grazing system (ROT) or continuous grazing system (CON) sampled in June, August, and October (n = 12 per sample time per month). No treatment differences were observed, so data were combined for presentation. An effect of sample time (P = 0.01) and month (P < 0.0001) was observed; interactions were found for sample time by month (P < 0.0001). * Plasma glucose was different (P < 0.05) in August than in June and October (except for 1200, where only June and August are different).

Figure 5.

Concentrations of serum insulin of horses grazing a rotational grazing system (ROT) or continuous grazing system (CON) sampled in June, August, and October (n = 12 per sample time per month). No treatment differences were observed in June and August, so data were combined for presentation. *Plasma insulin was higher in ROT than CON in October (P = 0.03). There was an effect of sample time (P < 0.0001) and month (P < 0.0001); interactions were found for sample time * month (P = 0.03), sample time * treatment (P = 0.0008), and treatment * month (P < 0.0001).

Fecal pH

Fecal pH for horses in ROT and CON in June, August, and October is shown in Table 4. Overall, fecal pH of horses did not differ between grazing systems. However, fecal pH of horses was affected by month (P < 0.0001) with fecal pH rising to their highest in August and then declining again in October. Within June, fecal pH was higher for horses in ROT compared to horses in CON (P < 0.05). Further investigation revealed that in June, 5 of the 6 horses in CON compared to only 2 out of 6 horses in ROT had fecal pH that fell below 6.0. There was no effect of time of day on fecal pH (data not shown).

Correlations

Significant correlations between GLU, INS, fecal pH, and forage nutrient concentration within each grazing system and month are shown in Table 5. There were few consistent patterns of significance within or between each grazing system with the exception of the positive correlation of INS with ESC (P < 0.04). There were also negative correlations between INS and GLU with ADF and NDF in August and October (P < 0.04). Also of interest was the positive correlation of CP with INS, GLU, and fecal pH mostly in CON in October when CP was highest (P < 0.03), however also with GLU in ROT (P = 0.0002). Other correlations were found but not consistent across all months or grazing systems.

Table 5.

Significant correlations between blood components and forage nutrient concentrations within each month and grazing system1,2

| June | August | October | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y | X | R | P | Y | X | R | P | Y | X | R | P | |

| CON | INS | ESC | 0.39 | 0.01 | INS | ESC | 0.32 | 0.04 | INS | ADF | −0.41 | 0.007 |

| GLU | Starch | 0.31 | 0.05 | GLU | ESC | −0.43 | 0.004 | INS | CP | 0.50 | 0.001 | |

| pH | WSC | 0.38 | 0.05 | GLU | Starch | 0.32 | 0.04 | |||||

| GLU | NDF | −0.32 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| GLU | CP | 0.35 | 0.02 | |||||||||

| pH | ADF | −0.42 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| pH | CP | 0.42 | 0.03 | |||||||||

| ROT | INS | ESC | 0.39 | 0.01 | INS | WSC | 0.45 | 0.003 | ||||

| INS | ADF | −0.31 | 0.05 | INS | ESC | 0.38 | 0.01 | |||||

| GLU | Starch | 0.34 | 0.03 | INS | ADF | −0.31 | 0.05 | |||||

| GLU | CP | −0.32 | 0.04 | GLU | ADF | −0.48 | 0.001 | |||||

| GLU | NDF | −0.46 | 0.002 | |||||||||

| GLU | CP | 0.55 | 0.0002 | |||||||||

| pH | WSC | −0.36 | 0.04 | |||||||||

| pH | ESC | −0.40 | 0.03 |

1Horse was included in the model to test for significance, if not significant, then it was removed from the model.

2Blood or fecal component (Y), forage nutrient concentration (X), correlation coefficient (R), P-value (P), rotational grazing system (ROT), continuous grazing system (CON), plasma glucose (GLU; n = 42), plasma insulin (INS; n = 42), and fecal pH (pH; n = 27), with water soluble carbohydrates (WSC; n = 42), ethanol soluble carbohydrates (ESC; n = 42), starch (n = 42), acid detergent fiber (ADF; n = 42), neutral detergent fiber (NDF; n = 42), and crude protein (CP; n = 42).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this study was to investigate whether managing grazing horses within a continuous or rotational grazing system across different seasons influenced forage carbohydrates and how those forage carbohydrates in turn affected the grazing horse’s glycemic and insulinemic responses. The main finding from this study was that taller grass heights associated with rotational grazing did not result in lower concentrations of soluble carbohydrates (WSC, ESC, and starch), and higher concentrations of structural carbohydrates (ADF and NDF) but did result in lower concentrations of CP in available forage. The lack of differences in nutrient composition between systems appears to be consistent with their lack of influences on GLU and fecal pH in horses across seasons. There was, however, a positive correlation between ESC and INS observed in multiple months within systems which may indicate that under certain conditions, soluble carbohydrates in the grasses can affect the glycemic response of the horse, particularly insulin response. This last finding has particular relevance to discussions of restricting intake of nonstructural carbohydrates to less than 10% of the diet (Frank et al., 2010b) for horses that are at risk for developing equine metabolic syndrome, with a major clinical sign in those horses being hyperinsulinemia. In fact, after further review of our INS data, we found 1 horse in the rotational grazing system had developed hyperinsulinemia (>30 mU/L; Frank et al., 2010b) by October of our study.

Effect of Grazing System

Horses are selective grazers and if allowed to graze forages continuously, they will repeatedly regraze and/or overgraze plants resulting in shorter, often defoliated swards (Archer, 1973; Fleurance et al., 2001) while leaving other ungrazed areas as “eliminative” or “latrine” areas. In the current study, a difference in the forage sward height of the 2 systems was evident with the continuously grazed pastures having shorter sward heights than the rotationally grazed pastures on our sample days. In a typical grazing season for the U.S. Northeast, continuously stocked fields will be grazed as soon as the forage is tall enough to be grasped by the horse’s lips and incisors. However, in rotational grazing systems, forage is rested and allowed to grow until the recommended height of 15.2 cm or higher (Henning et al., 2000; Undersander et al., 2002) before grazing. Due to a long, cold winter resulting in slow forage growth, the horses in the ROT were not allowed to graze until early June when the targeted sward height was obtained.

Pre-graze sward height values reported by Burk et al. (2011) for a rotational grazing system were 28.2 ± 2.8 cm and 18.3 ± 3.3 cm in years 1 and 2, respectively. Values from the current study are similar, with ROT pre-graze sward heights ranging from about 12 to 24 cm during the sampling months with CON heights approximately half of ROT. However, taller sward heights and more available forage per hectare do not necessarily equate to a higher plane of nutrition for horses. As grasses mature, their nutritional quality generally declines (Evans, 1995). Chatterton et al. (2006) observed that as oat forage matures, its CP and simple sugars (glucose, fructose, and sucrose) decrease while starch and fiber fractions increase. We also observed a decline in CP within the taller grasses in the rotational grazing systems compared to the shorter grasses within the continuously grazed system. Chatterton et al. (2006) found that fructans and nonstructural carbohydrates (NSC = simple sugars + starch + fructans) followed a less predictable pattern across 2 plantings, and this was attributed to the fructan concentrations being impacted by environmental conditions more than maturity. This was also investigated by Siciliano (2015) by examining grazing preference and NSC with pre-grazing sward heights clipped to either a short, medium, or long height (12.1, 21.0, and 31.8 ± 1.5 cm, respectively). This study cannot be used as a direct comparison to the current study due to the fact that clipping and grazing create different stresses on the plant. As reviewed by White (1973), grazing reduces plant vigor more than clipping due to unequal removal of leaf mass. Ungrazed tillers will reallocate carbohydrate stores to facilitate regrowth of the grazed tillers, slowing down growth of the ungrazed tillers and the plant as a whole. Additionally, forage heights that are artificially created by mowing do not represent the normal nutrition composition patterns of plant maturity. For example, the composition of 12 cm-tall grass would be different if it was mowed down from 36 cm, 12 cm of original new growth in the spring, or forage that was mowed to 6 cm and regrew back to 12 cm. Nevertheless, the previous study found NSC concentrations in the short, medium, and long grasses to increase with sward height (18.7, 26.9, and 30.5 ± 1.5%, respectively). They also found that horses spent more time grazing the forage as sward height increased (8.8, 19.7, and 31.5 ± 3.5 min, respectively; Siciliano, 2015). This leads us to believe that taller forage would also create a larger glucose and insulin response. However, a companion study by Siciliano et al. (2017) found that only serum insulin concentrations were greater in horses grazing the taller swards, which could be due to the horses eating more dry matter during the grazing period. Even though the current study did not find effects of grazing system on circulating concentrations of glucose or insulin, there were correlations for insulin and soluble carbohydrate concentrations. We believe that our current study would more likely represent natural growth and regrowth of the grasses and their maturity vs. the artificially clipped grasses in the previous studies.

In a preliminary report comparing grazing systems of warm and cool-season grasses, Daniel et al. (2015) stated that rotational grazing of horses was associated with better forage quality, evidenced by higher concentrations of digestible energy (DE) and soluble carbohydrates (WSC, and sugar), and lower levels of fiber fractions (ADF, NDF, and lignin) compared to continuous grazing. The average concentrations over the 2 yr of the project for WSC and sugars were about half or less of the concentrations in the current study. This difference could be attributed to the fact that their pastures were a mix of warm-season and cool-season forages. That study did not reference sward height, but a companion report by Virostek et al. (2015) did examine botanical composition and forage biomass and found that both were similar between rotational and continuously grazed systems. It is important to note 3 main differences between these studies and the current study. First, the previous studies took place in Tennessee where the climate is warmer, and the pastures contained a high proportion of Bermudagrass (Cynodon dactylon), which is a warm-season grass that accumulates starch instead of sugars. However, starch was not reported in their study. Secondly, the previous studies used a stocking density of 0.60 ha per horse unlike the current study which used 0.52 ha per horse. Therefore, overgrazing might not have occurred to the same extent in the previous studies as in the current study. Third, the current study sampled where the horses were grazing during that sample time, and not an entire representation of the field including both roughs and lawns in the continuous system.

It has been shown that as plants mature, they generally decrease in simple sugars and CP content and increase in fiber content (Chatterton et al., 2006). As plants produce seed heads, the starch content may increase as well (Chatterton et al., 2006); however, in the current study we did not observe a difference in starch in the taller ROT swards. In June, when sward heights were tallest in both systems and seed heads might have been present in the ROT system, the starch was not different between systems. The lower CP found in the ROT systems was an interesting observation that supports previous findings that forage quality declines as it grows taller and more mature.

Effect of Season

In the present study, we repeated our sampling during 3 mo, June (spring), August (summer), and October (fall) to explore how season might affect forage carbohydrates and equine metabolism across the 2 grazing systems. Despite forage having higher concentrations of WSC and ESC in June, the concentrations were apparently not high enough to elicit changes in GLU and INS in the horses. Horses in the current study had higher GLU in August and higher INS in October, which did not follow the same pattern as the soluble carbohydrate concentrations in the grasses. McIntosh (2007) observed highest WSC and starch concentrations in Virginia tall fescue (F. arundinacea) pastures in April compared to May, August, October, and January. That is similar to what Frank et al. (2010a) found in Tennessee with ESC and Hoffman et al. (2001) with hydrolyzable carbohydrates (sugars plus starches) in northern Virginia. In April, McIntosh (2007) also found significant impacts on the insulin and glucose concentrations of grazing horses which were attributed to the effects of ambient temperature, solar radiation, and humidity on soluble carbohydrate concentrations. However, Frank et al. (2010a) only found increases in glucose and insulin in September when ESC was at its second peak. It is not known if a similar pattern exists in the Northeast United States because sufficient forage was not available for grazing in April or May due to the late spring growing conditions. It has been shown that the seasonal variation of carbohydrates in grasses differs widely among grass species; some are lowest about a month after growth; however, others decrease right after the seed ripens (White, 1973).

April temperatures in Virginia (McIntosh, 2007) were about 13 °C lower than June in the current study, suggesting 1 reason for the significantly higher ESC content of the forage (18.9% in McIntosh vs. 9.4% in current study analyzed by the same lab). Our sugar concentrations are closer to what McIntosh found in May (10.2%) in that study; however, temperatures were still much higher during June in the current study. The weather data in June in the current study closely matched Chatterton’s (1989) warmer temperatures of 15 °C in the overnight and 25 °C in the daytime. Chatterton (1989) concluded that cooler ambient temperatures can cause an increase in the forage accumulation of NSC. This was found to be the case in a study in October and November in northern Virginia (Hoffman et al., 2001), but was not found in the current study. October had cooler average, as well as minimum and maximum temperatures than August by about 10 °C; however, the WSC and ESC were not significantly different from August and starch was less than half of August values.

Previous studies have determined that circadian and seasonal variation of carbohydrates in forage is subject to “ideal” conditions and vary due to light intensity, temperature, soil, and water availability (Waite and Boyd, 1953; Fales and Fritz, 2007). In the current study, the average temperature was similar to the area’s historical averages for the sample months. Therefore, climate variables alone make it difficult to compare nutrient content fluctuations in forages across states even if in relative close proximity. This could also explain the different correlations found in the current study compared to previous studies. Previously, a positive correlation was found only in April and May for insulin and sugars, which is the same as ESC in the current study (McIntosh, 2007); however, the current study found INS positively correlates with ESC in one or both grazing systems in all 3 mo of sampling, similar to what was found previously by Frank et al. (2010a). Furthermore, McIntosh (2007) only found glucose to positively correlate with sugars in April, whereas the current study found GLU to positively correlate with either ESC or starch in each month in both systems. The current study also found negative correlations between both GLU and INS and the fiber fractions (ADF and NDF) and positive correlations with CP, which, to the author’s knowledge, is the first time these correlations have been published in grazing horses. These correlations were especially prominent in October when CP was highest and ADF and NDF were lowest. Some previous reports of nutrient effects on glycemic response indicate that with increased amounts of fat and protein, there is a secretion of gut hormones that increase the insulin response and glucose clearance (Vervuert and Coenen, 2006). This was supported by Urschel et al. (2010), who observed that when horses were given equal amounts of glucose, the response curve of insulin and glucose was greater with the addition of whey protein, and even greater with the addition of leucine. However, a few studies report no differences in glucose and insulin response after diets of either corn (low protein) or alfalfa (high protein) (Stull and Rodiek, 1988) or meal feeding with Lucerne chaff (high protein) as compared to oats (low protein) (Harris et al., 2005).

Drought also can affect the NSC content in the grasses. Volaire and Lelièvre (1997) showed that after a 3-mo drought, NSC in orchardgrass reached levels 3 to 4 times those observed in the current study in the fructan component alone. Compared to historical averages, precipitation was 9 cm lower in August in the current study. However, these drought conditions in August were not enough to increase the NSC content significantly.

Fecal pH is often used as an indicator of hindgut pH and thus an indicator of digestive health in grazing horses. It was of particular interest in this study because of reports that dietary carbohydrates may alter microbial fermentation products, leading to a reduction in cecal pH (Willard et al., 1977; Goodson et al., 1988; Radicke et al., 1991) and subsequent increase in digestive disturbances and laminitis (Garner et al., 1978; Longland and Byrd, 2006). The threshold for hindgut acidosis leading to digestive disturbances is believed to be pH < 6.0 (Garner et al., 1978; Geor and Harris, 2007). In previous studies, cecal and colonic pH for horses fed forage-only diets range from 6.7 to 7.1 (Willard et al., 1977; Goodson et al., 1988; Goer and Harris, 2007). In our study, mean fecal pH for horses averaged across both systems ranged from 6.3 to 7.1. Despite some of our horses having lower fecal pH than previously observed in forage-only fed horses, we did not observe any bouts of diarrhea, colic, or laminitis. However, we did observe lower fecal pH in June and October compared to August, owing to the variability of forage nutrients with season.

There were no consistent relationships found between forage carbohydrates and fecal pH in our study. By comparison, a study comparing digestive parameters in horses grazing a cool-season pasture compared to a hay-only diet identified a potential link between forage NSC content and alterations in glucose and insulin characteristics, lactate-producing bacteria, and fecal pH in April only (McIntosh, 2007). In that study, the alterations in metabolic and digestive variables observed in grazing horses may reflect increased intake and digestion of hydrolysable and rapidly fermentable NSC that were present in April in Virginia that were not present in the current study.

Effect of Time of Day

Factors which significantly influence daily variations in soluble carbohydrate fractions not only include ambient temperature and humidity but also solar radiation. It has been well studied that cool-season forages utilize soluble carbohydrates produced from photosynthesis, typically resulting in lowest NSC content in the early morning, which then peaks in the afternoon and declines through the overnight hours as respiration utilizes the soluble carbohydrates (Bowden et al., 1968; Holt and Hilst, 1969; Longland et al., 1999; McIntosh, 2007). We observed similar trends for WSC, ESC, and starch with lower concentrations occurring earlier in the day (0400 and 0800) and then increases in concentration later in the day (2000 and 0000). Due to the every 4-h sampling pattern, it is possible that we missed the peak in forage soluble carbohydrate content which has been shown to be highest in the late afternoon (between 1600 and 1800), especially during the spring months (Longland and Byrd, 2006; McIntosh, 2007). Forage quality values (ESC and WSC) of the pastures were slightly lower than those reported by McIntosh (2007) of tall fescue pastures in Virginia. Even though the current study did not record solar radiation during sampling, the sampling days were similar with ample sun present on each sampling day. This leaves seasonal solar radiation as the only change between months, and the day length did not seem to affect the soluble carbohydrate fractions in the forages.

Time of day had an effect on WSC, ESC, starch, GLU, and INS. The lowest samples for GLU and INS at 0400 and 0800, respectively, corresponded with the lower WSC concentrations. However, there was not a true peak for GLU and INS like one would expect given the peak concentrations of ESC in the forage at 0000. The GLU and INS results also do not follow the same graphical curve as other previous diurnal variation studies using horses on pasture (McIntosh, 2007). However, they are similar to findings by Staniar et al. (2007) from the daylight hours of sampling pasture-kept horses in northern Virginia pasture in May (late spring). Baseline GLU concentrations in the current study are similar to concentrations from horses on pasture only in Staniar et al. (2007) and in other studies investigating meal feeding in stall-kept horses (75 to 98 mg/dL) (Stull and Rodiek, 1988; Williams et al., 2001; Vervuert et al., 2004). When insulin units from the current study are converted (1 to 11 mIU/L, 1 individual reached 18.7 mIU/L at the peak), they are also similar to baseline levels in stalled horses (4 to 6 mIU/L) (Staniar et al., 2007) and grazing horses (7 to 9 μIU/mL) in DeBoer et al. (2018), but they are much lower than baseline concentrations (about 27 mIU/L) found in Staniar et al. (2007) and peak concentrations (20 to 30 mIU/L) found in Siciliano et al. (2017) or DeBoer et al. (2018) (30 to 40 mIU/L spring and 50 to 60 mIU/L fall) for pasture-kept horses.

There are many reasons for the variation in glucose and insulin results among studies including, but not limited to, season, climate, geographic location, grass species, horse breed, study protocols, individual variation, etc. In regards to the differences observed in glucose and insulin in our study compared to the aforementioned studies, the sampling period in Siciliano et al. (2017) was unknown but assumed to be spring in North Carolina on cool-season tall fescue pastures, Staniar et al. (2007) sampled in spring (May) in Northern Virginia on cool-season tall fescue pastures, while DeBoer et al. (2018) sampled in summer (July) and fall (September) in Minnesota on mixed cool-season grasses. These factors will also create variation in soluble carbohydrate concentrations in the forages as was seen in these previous studies as compared to the current study. Two of the studies mentioned above (DeBoer et al. and Siciliano et al.) used a 12-h fast before sample collection, while the current study and Staniar et al. used horses that were on pasture or fed hay prior to sampling. An additional reason for the variation in insulin concentration between studies includes age of horses. It has been shown that older horses have a lower insulin sensitivity than adult horses and therefore higher insulin concentrations (Jacob et al., 2017). The highest insulin concentrations were found in DeBoer et al. (2018) which used horses with an age range of 21 to 28 yr old. The current study used horses with an average age of 14, while Siciliano et al. (2017) used horses between 6 and 12 yr and Staniar et al. (2007) used horses averaging 12 yr, which was more similar to the current study.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that while rotational grazing was effective in increasing sward height, it had minor influences on plant nutrients which ultimately had no apparent glycemic or insulinemic implications for the grazing horse. It is worth noting that the pasture systems had only been grazed for 14 mo by the final sampling date, and pasture degradation by overgrazing is a continuous process that could have greater impact on these variables as it gets more severe over time. A more pronounced result within both grazing systems was the influence of season and time of day on plant carbohydrates. The rising concentrations of soluble carbohydrates in forages throughout the day and the positive association between forage ESC and circulating INS in the horse reinforce the recommendations that horses with metabolic disorders like equine metabolic syndrome should have grazing limited or excluded, regardless of grazing management system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the students and staff volunteers from Rutgers University, University of Maryland, and Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University for their assistance on this project. Funding was provided by the Rutgers University Equine Science Center.

LITERATURE CITED

- Archer M. 1973. The species preferences of grazing horses. Grass Forage Sci. 28:123–128. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2494.1973.tb00732.x [Google Scholar]

- Bowden D. M., Taylor D. K., and Davis W. P.. . 1968. Water-soluble carbohydrates in orchardgrass and mixed forages. Can. J. Plant Sci. 48:9. [Google Scholar]

- Burk A. O., Fiorellino N. M., Shellem T. A., Dwyer M. E., Vough L. R., and Dengler E.. . 2011. Field observations from the University of Maryland’s equine rotational grazing demonstration site: a two year perspective. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 31:302–303 (Abstr.). doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2011.03.132 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton N. J., Harrison P. A., Bennett J. H., and Asay K. H.. . 1989. Carbohydrate partitioning in 185 accessions of graminae grown under warm and cool temperatures. J. Plant Physiol. 143:169–179. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterton N. J., K. A. Watts K. B. Jensen P. A. Harrison, and Horton W. H.. 2006. Nonstructural carbohydrates in oat forage. J. Nutr. 136:2111–2113. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.7.2111S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel A. D., McIntosh B. J., Plunk J. D., Webb M., McIntosh D., and Parks A. G.. . 2015. Effects of rotational grazing on water-soluble carbohydrate and energy content of horse pastures. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 35:385–386 (Abstr.). doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2015.03.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeBoer M. L., Hathaway M. R., Kuhle K. J., Weber P. S. D., Reiter A. S., Sheaffer C. C., Wells M. S., and Martinson K. L.. . 2018. Glucose and insulin response of horses grazing alfalfa, perennial cool-season grass, and teff across seasons. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 68:33–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans J. L. 1995. Forages for horses. In: Barnes R. F., Miller D. A., and Nelson C. J., editors, Forages: the science of grassland agriculture. 5th ed. Iowa State Univ. Press, Iowa City, IA: p. 303–311. [Google Scholar]

- Fales S.L. and Fritz J.O.. 2007. Factors Affecting Forage Quality. In: Barnes R.F., Nelson C.J., Moore K.J., and Collins M. (eds.) Forages; The Science of Grassland Agriculture. Blackwell Publishing, Ames, IA. p. 574–577. [Google Scholar]

- Fleurance G., Duncan P., and Mallevaud B.. . 2001. Daily intake and the selection of feeding sites by horses in heterogeneous wet grasslands. Anim. Res. 50:149–156. doi:10.1051/animres:2001123 [Google Scholar]

- Foulk D. L., Mickel R. C., Chamberlain E. A., Margentino M., and Westendorf M.. . 2004. Agricultural management practices for commercial equine operations. Rutgers Cooperative Extension, New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Frank N., S. B. Elliott K. A. Chameroy F. Tóth N. S. Chumbler, and McClamroch R.. 2010a. Association of season and pasture grazing with blood hormone and metabolite concentrations in horses with presumed pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 24:1167–1175. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0547.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank N., R. J. Geor S. R. Bailey A. E. Durham, and Johnson P. J.; American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine 2010b. Equine metabolic syndrome. J. Vet. Intern. Med. 24:467–475. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garner H. E., J. N. Moore J. H. Johnson L. Clark J. F. Amend L. G. Tritschler J. R. Coffmann R. F. Sprouse D. P. Hutcheson, and Salem C. A.. 1978. Changes in the caecal flora associated with the onset of laminitis. Equine Vet. J. 10:249–252. doi:10.1111/j.2042-3306.1978.tb02273.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geor R. J., and Harris P. A.. . 2007. How to minimize gastrointestinal disease associated with carbohydrate nutrition in horses. Am. Assoc. Equine Pract. Proc. 53:178–185. [Google Scholar]

- Goodson J., W. J. Tyznik J. H. Cline, and Dehority B. A.. 1988. Effects of an abrupt diet change from hay to concentrate on microbial numbers and physical environment in the cecum of the pony. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54:1946–1950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. A., Sillence M., Inglis R., Siever-Kelly C., Friend M., Munn K., and Davidson H.. . 2005. Effect of Lucerne chaff on the rate of intake and glycaemic response to an oat meal. Proc. Equine Nutr. Phys. Symp. 19:151–152. [Google Scholar]

- Heady H. F. 1961. Continuous vs. specialized grazing systems: a review and application to the California annual type. J. Range Mngmt. 14:182–193. [Google Scholar]

- Heady H. F. 1970. Grazing systems: terms and definitions. J. Range Mngmt. 23:59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Henning J., Lacefield G., Rasnake M., Burris R., Johns J., and Turner L.. . 2000. Rotational grazing. Univ. Kentucky, Coop. Exten. Service. ID-143. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman R. M., J. A. Wilson D. S. Kronfeld W. L. Cooper L. A. Lawrence D. Sklan, and Harris P. A.. 2001. Hydrolyzable carbohydrates in pasture, hay, and horse feeds: direct assay and seasonal variation. J. Anim. Sci. 79:500–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt D. A., and Hilst A. R.. . 1969. Daily variation in carbohydrate content of selected forage crops. Agron. J. 61:239. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob S. I., R. J. Geor P. S. D. Weber P. A. Harris, and McCue M. E.. 2017. Effect of age and dietary carbohydrate profiles on glucose and insulin dynamics in horses. Equine Vet. J. 50:249–254. doi: 10.1111/evj.12745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny L. B. 2016. The effects of rotational and continuous grazing on horses, pasture condition, and soil properties. Master Thesis, Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Longland A. C., and Byrd B. M.. . 2006. Pasture nonstructural carbohydrates and equine laminitis. J. Nutr. 136(7 Suppl.):2099S–2102S. doi:10.1093/jn/136.7.2099S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longland A. C., Cairns A. J., and Humphreys M. O.. . 1999. Seasonal and diurnal changes in fructan concentration in Lolium perenne: implications for the grazing management of equines pre-disposed to laminitis. In: Proc. 16th Equine Nutr. Physiol. Soc., Raleigh, NC p. 258–259. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh B. 2007. Circadian and seasonal variation in pasture nonstructural carbohydrates and the physiological response of grazing horses. Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA. [Google Scholar]

- Odberg F. O., and Francis-Smith K.. . 1976. A study on eliminative and grazing behaviour - the use of the field by captive horses. Equine Vet. J. 8:147–149. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1976.tb03326.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radicke S., Kienzle E., and Meyer H.. . 1991. Preileal apparent digestibility of oat and corn starch and consequences for cecal metabolism. In: Proc. 12th Equine Nutr. Physiol. Symp. p. 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Siciliano P. D. 2015. Effect of sward height on grazing preference and pasture NSC concentration. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 35:435. [Google Scholar]

- Siciliano P. D., Gill J. C., and Bowman M. A.. . 2017. Effect of sward height on pasture nonstructural carbohydrate concentrations and blood glucose/insulin profiles in grazing horses. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 57:29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2017.06.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staniar W. B., Cubitt T. A., George L. A., Harris P. A., and Geor R. J.. . 2007. Glucose and insulin responses to different dietary energy sources in Thoroughbred broodmares grazing cool season pasture. Livest. Sci. 111:164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2007.01.148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stull C. L., and Rodiek A. V.. . 1988. Responses of blood glucose, insulin and cortisol concentrations to common equine diets. J. Nutr. 118:206–213. doi: 10.1093/jn/118.2.206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undersander D., Albert B., Cosgrove D., Johnson D., and Peterson P.. . 2002. Pastures for profit: a guide to rotational grazing. Cooperative Extension Publishing, University of Wisonsin-Extension, Madison, WI. [Google Scholar]

- Urschel K. L., Geor R. J., Waterfall H. L., Shoveller A. K., and McCutcheon L. J.. . 2010. Effects of leucine or whey protein addition to an oral glucose solution on serum insulin, plasma glucose and plasma amino acid responses in horses at rest and following exercise. Equine Vet. J. 42(Suppl. 38):347–354. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vervuert I., and Coenen M.. . 2006. Factors affecting glycaemic index of feds for horses. In: Proc. 3rd European Equine Nutr. Health Congress Ghent University, Merelbeke, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Vervuert I., M. Coenen, and Bothe C.. 2004. Effects of corn processing on the glycaemic and insulinaemic responses in horses. J. Anim. Physiol. Anim. Nutr. (Berl) 88:348–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0396.2004.00491.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virostek A. M., McIntosh B., Daniel A., Webb M., and Plunk J. D.. . 2015. The effects of rotational grazing on forage biomass yield and botanical composition of horse pastures. J. Equine Vet. Sci. 35:386 (Abstr.). doi: 10.1016/j.jevs.2015.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Voisin A. 1959. Grass productivity. New York Philosophical Library, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Volaire F., and Lelièvre F.. . 1997. Production, persistence, and water-soluble carbohydrate accumulation in 21 contrasting populations of Dactylis glomerata L. subjected to severe drought in the south of France. Aust. J. Agr. Res. 48:933–944. doi: 10.1071/A97004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waite R., and Boyd J.. . 1953. The water-soluble carbohydrates in grasses 1. Changes occurring during the normal life cycle. Sci. Food Agr. 4:197–200. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.2740040408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White L. M. 1973. Carbohydrate reserves of grasses: a review. J. Range Mngmt. 26:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- Willard J. G., J. C. Willard S. A. Wolfram, and Baker J. P.. 1977. Effect of diet on cecal pH and feeding behavior of horses. J. Anim. Sci. 45:87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C. A., D. S. Kronfeld W. B. Staniar, and Harris P. A.. 2001. Plasma glucose and insulin responses of Thoroughbred mares fed a meal high in starch and sugar or fat and fiber. J. Anim. Sci. 79:2196–2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]