Abstract

Background

Atrial fibrillation (AF) and heart failure (HF) are tightly interrelated. The concurrence of these pathologies can aggravate the pathological process. The geographic and ethnic characteristics of patients may significantly affect the efficacy of different types of therapy and patients' compliance. The objective of this study was to analyze how the features of the course of the diseases and management of HF + AF influence the clinical outcomes.

Methods

The data of 1,003 patients from the first Russian register of patients with chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation (RIF-CHF) were analyzed. The endpoints included hospitalization due to HF worsening, mortality, thromboembolic events, and hemorrhage. Predictors of unfavorable outcomes were analyzed separately for patients with HF and preserved ejection fraction (AF + HFpEF), midrange ejection fraction (AF + HFmrEF), and reduced ejection fraction (AF + HFrEF). Prevalence of HF + AF and compliance with long-term treatment of this pathology during one year were evaluated for each patient.

Results

The study involved 39% AF + HFpEF patients, 15% AF + HFmrEF patients, and 46% AF + HFrEF patients. AF + HFpEF patients were significantly older than patients in two other groups (40.6% of patients were older than ≥75 years vs. 24.8%, respectively, p < 0.001) and had the lowest rate of prior myocardial infarctions (25.3% vs. 46.1%, p < 0.001) and the lowest adherence to rational therapy of HF (27.4% vs. 47.1%, p < 0.001). AF + HFmrEF patients had the highest percentage of cases of HF onset after AF (61.3% vs. 49.2% in other patient groups, p=0.021). Among patients with AF + HFrEF, there was the highest percentage of males (74.2% vs. 41% in other patient groups, p < 0.001) and the highest percentage of ever-smokers (51.9% vs. 29.4% in other patient groups, p < 0.001). A total of 57.2% of patients were rehospitalized for decompensation of chronic heart failure within one year; the risk was the highest for AF + HFmrEF patients (66%, p=0.017). Reduced ejection fraction was associated with the increased risk of cardiovascular mortality (15.5% vs. 5.4% in other patient groups, p < 0.001) rather than ischemic stroke (2.4% vs. 3%, p=0.776). Patients with AF + HFpEF had lower risk to achieve the combination point (stroke + IM + CV death) as compared to patients with AF + HFmrEF and AF + HFrEF (12.7% vs. 22% and 25.5%, p < 0.001). Regression logistic analysis revealed that factors such as demographic characteristics, disease severity, and administered treatment had different effects on the risk of unfavorable outcomes depending on ejection fraction group. The clinical features and symptoms were found to be significant risk factors of cardiovascular mortality in AF + HFmrEF, while therapy characteristics were not associated with it.

Conclusions

Each group of patients with different ejection fractions is characterized by its own pattern of factors associated with the development of unfavorable outcomes. The demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with midrange ejection fraction demonstrate that these patients need to be studied as a separate cohort.

1. Introduction

Atrial fibrillation (AF), the most frequently encountered sustained cardiac arrhythmia, is the key risk factor for transient ischemic attack (TIA), stroke, and heart failure [1]. Its prevalence goes up with age, and population in Russia is aging nowadays. Heart failure (HF) is induced by structural and/or functional cardiac abnormalities and results in decreased cardiac pump function [2]. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure are closely interrelated [3, 4]. There currently is lack of understanding of the association between AF and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF); however, the clinical aspects seem to be rather important [5]. Comorbidity of atrial fibrillation and heart failure (AF + HF) is frequently observed because of the high prevalence of each disease entity, as well as due to shared risk factors and synergistic pathophysiology [6]. As the global population ages, the burden of both disease entities will be getting stronger over time [5]. Since these disease states have similar mechanisms, AF and HF tend to coexist [7–11]. One of the key features of their comorbidity is that each disease entity can trigger and aggravate the course of the other condition. The risk of thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation becomes higher if they have such comorbidities as ischemic heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes [1]. The coexisting AF + HF increase the risk of thromboembolic complications, stroke in particular [1], and may deteriorate the cardiac function. In its turn, it results in aggravation of HF symptoms, thus leading to a self-perpetuating vicious circle [7]. Depending on whether AF or HF is the underlying condition, patient groups differ rather significantly in terms of outcomes and the required therapeutic approach. A patient who developed HF after AF has a more favorable prognosis [12] than a patient who had HF prior to AF [13, 14], probably because AF is a marker of severe course of the disease and can deteriorate the cardiac function [7]. Even this difference alone attests to significant heterogeneity observed in the total cohort of these patients. However, there are other important parameters subdividing patients with AF + HF into the fundamentally different groups.

According to the current clinical practice guidelines for managing patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) (2016), heart failure is divided into three clinical subtypes: HF with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF: EF ≥ 50%), HF with a midrange ejection fraction (HFmrEF: 40 ≤ EF < 49%), and HF with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF: EF < 40%) [7]. These patient cohorts strongly differ in terms of a number of parameters, from the epidemiology and etiology to the current severity and treatment strategies. Many questions regarding the differential treatment strategy are yet to be solved. One of the reasons is that our knowledge of HFpEF and HFmrEF is limited, and the data about these conditions have mainly been obtained from retrospective studies or post hoc analyses of randomized trials [7, 15]. Over the past 2 years, there has been a trend to conduct studies in isolated subgroups of patients having a certain ejection fraction [16–19]. This makes study groups more homogeneous and allows one to draw relevant conclusions. However, studies of this type are not devoid of drawbacks. The most fundamental one is that it is impossible to compare patients with different ejection fractions who are similar in nonmodifiable risk factors, such as area of residence, ethnicity, environment, climate, and family history. This fact prevents evaluation of the contribution of modifiable risk factors (lifestyle, dietary habits, current therapy, and prior therapy) to development and course of the disease. Simultaneous searching for intergroup similarities and differences needs to be conducted to understand the general principles of pathogenesis and the course of comorbid AF + AHF. One of the advantages of nationwide cohort studies as compared to narrowly focused prospective studies having strict inclusion criteria regarding the ejection fraction is that all three patient subtypes are included and can be compared.

There is a gap in understanding of the overall clinical pattern of the course of CHF + AF comorbidity and in selection of the optimal treatment strategies; so, it is very important to perform cross-sectional studies to fill this gap. The high prevalence of AF + CHF offers a unique opportunity for the researchers worldwide both to conduct large-scale prospective randomized clinical trials [20–27] and to collect the populationwide data using registries [1, 2, 28–31]. Each of these designs has its own advantages and drawbacks. Randomized clinical trials allow one to use the “refined” patient subgroups to answer a specific question regarding the treatment approach. Nation- and regionwide cohort studies make it possible to reveal the overall regularities in etiology and pathogenesis, as well as to demonstrate the real-world situation.

Our study was aimed to analyze how the features of the course of diseases and management of CHF + AF influence the clinical outcomes and collecting the data on compliance with clinical guidelines and on the long-term prevalence of this condition in Russia.

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Patient Selection, and Ethical Considerations

The analysis was conducted using the data retrieved from the Russian registry of patients with chronic heart failure and atrial fibrillation (RIF-CHF) that involved the data obtained in a multicenter prospective observational study in patients with CHF + AF (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02790801). Patients were recruited for survey participation at 30 medical centers in 21 provinces of the Russian Federation over the period between February 2015 and January 2016. The patients were selected on a competitive continuous basis. The planned total number of patients to be recruited was ≥1,000. The recruitment was stopped once 1,003 patients had been selected.

All patients had a confirmed diagnosis of CHF + AF comorbidity. The diagnosis of CHF was made according to the local Russian guidelines and corresponded to the ESC 2012 HF Guidelines criteria and ESC 2012 Update of the Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation. The division into ejection fraction groups was conducted with allowance for the 2016 amendments to the Guidelines.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

Age >18 years

- Documented symptomatic chronic heart failure for at least 3 months prior to screening in accordance with the following criteria:

- no additional laboratory verification of the diagnosis is needed at LVEF ≤40%

- at LVEF >40%, the NT-proBNP level ≥300 pg/ml or BNP level ≥100 pg/ml

Hemodynamically stable nonvalvular atrial fibrillation

The exclusion criteria were as follows: transient ischemic attack within 3 days before enrollment; stroke during 14 days before enrollment; myocardial infarction within 14 days before enrollment; thromboembolic complications or thrombosis within 14 days before enrollment; heart failure because of valvular pathology; heart failure induced by infectious agents or infiltrative diseases; alcohol consumption; use of psychoactive drugs; peripartum heart disease; transient conditions; planned heart transplantation; implantation of biventricular pacemaker within 28 days before enrollment; any severe condition limiting patient's life to less than 3 months; HIV infection; alcohol consumption or intake of psychoactive drugs; participation in any experimental study within 30 days before enrollment; and patient being not ready to be contacted by telephone at the end of the follow-up period.

The survey was conducted in compliance with the Good Clinical Practice ensuring that the design, implementation, and communication of data are reliable; that patients' rights are protected; and that the integrity of subjects is maintained by the confidentiality of their data. The study was approved by the Local Ethics Committee of the Federal State Budget Scientific Institution “Research Institute of Cardiology” and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (no. NCT02790801). All patients provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which included their consent for their data to be analyzed and presented.

2.2. Data Collection: Baseline

Patients' life and past medical histories were collected at admission. Parameters to be collected and documented were as follows:

General and demographic characteristics: date of birth, gender, educational status, occupation, residential region, smoking status, dietary habits, weight, height, and physical activity level

Features and course of the disease in the past: dates when the patient was diagnosed with CHF and AF, predominant cardiac diagnosis, frequency of hospitalization over the past year, and past history of surgeries

The current disease status: the reason for the current hospital admission (scheduled follow-up examination, decompensated heart failure, and surgical treatment), symptoms and signs, and blood pressure; instrumented test values (ECG, echocardiography); presence and severity of aortic and mitral regurgitation; and blood chemistry test

Current treatment and patient's response to it: all drugs administered to treat CHF and AF; compliance with the treatment schedules according to the local and international guidelines; and efficacy of heart rate control for patients with permanent atrial fibrillation (maintaining the heart rate at < 100 bpm)

Concomitant diseases

Family history of hypertension, AF, and early-onset IHD

The clinical and laboratory data for each patient were collected 6 and 12 months after study enrollment.

2.3. Data Collection: Endpoints

The primary endpoint was hospitalization due to worsening of heart failure. HF hospitalization was defined as an overnight (or longer) stay in a hospital, with HF being the primary reason.

Secondary endpoints were death from a cardiovascular event (CV mortality), thromboembolic events (overall and for each category), and bleeding (ISTH major or CRNM). The time of event onset was documented for the endpoints. If possible, the follow-up was continued for 12 months.

2.4. Data Collection: Therapy Adherence

Therapy adherence was evaluated by a direct survey. At each of the three visits, patients were asked to provide information regarding the therapy they were currently receiving, as well as the therapy they had been receiving over the previous 6 months.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were presented as absolute frequencies or medians with the interquartile range. The Mann–Whitney U test, or Pearson's χ2 test, or Fisher's exact test and nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test by rank and median multiple comparisons were used depending on type of the data being processed. The Kaplan–Meier model was employed to analyze the achievement of target indicators. All the reported p values were based on two-tailed tests of significance; the p values < 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. STATISTICA 7.0 software (StatSoft, USA) and RStudio software version 1.0.136 (Free Software Foundation, Inc., USA) with R packages version 3.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Austria) were used for the analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

The survey included 1,003 patients with AF + HF. Almost half of them (46.5% of patients) had heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (AF-HFrEF); 38.6 and 15% of patients had heart failure with preserved (AF-HFpEF) and midrange (AF-HFmrEF) ejection fractions, respectively. The data on patient characteristics at baseline are summarized in Table 1–3.

Table 1.

Demographic and anamnestic characteristics of patients included in the study.

| Parameters | Total cohort (n=1003) | AF-HFpEF (n=387) | AF-HFmEF (n=150) | AF-HFrEF (n=466) | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demography and habits | |||||

| Age, years | 68 (60 : 76) | 72 (63 : 78) | 67 (58 : 75) | 66 (58 : 75) | <0.001 |

| The proportion of patients ≥65 years of age | 589 (58.7%) | 270 (69.8%) | 82 (54.7%) | 237 (50.9%) | <0.001 |

| The proportion of patients ≥75 years of age | 310 (30.9%) | 157 (40.6%) | 38 (25.3%) | 115 (24.7%) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 437 (43.6%) | 253 (65.4%) | 64 (42.7%) | 120 (25.8%) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index ≥30 | 360 (35.9%) | 147 (38%) | 62 (41.3%) | 151 (32.4%) | 0.076 |

| Low level of physical activity (exercise less than 30 min/day, no more than 3 times/week) | 570 (56.8%) | 191 (49.4%) | 96 (64%) | 283 (60.7%) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 603 (60.1%) | 295 (76.2%) | 84 (56%) | 224 (48.1%) | <0.001 |

| Quit smoking | 216 (21.5%) | 53 (13.7%) | 38 (25.3%) | 125 (26.8%) | |

| Active smoker | 184 (18.3%) | 39 (10.1%) | 28 (18.7%) | 117 (25.1%) | |

| Comorbidities and pathologies | |||||

| Hypertension, fact | 653 (65.1%) | 263 (68%) | 108 (72%) | 282 (60.5%) | 0.012 |

| Hypertension, duration, years | 14 (10 : 20) | 13 (10 : 20) | 10 (7.5 : 20) | 15 (10 : 20) | 0.916 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 686 (68.4%) | 271 (70%) | 107 (71.3%) | 308 (66.1%) | 0.336 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 247 (24.6%) | 89 (23%) | 38 (25.3%) | 120 (25.8%) | 0.632 |

| Previous stroke/TIA | 158 (15.8%) | 58 (15%) | 22 (14.7%) | 78 (16.7%) | 0.747 |

| Previous myocardial infarct | 382 (38.1%) | 98 (25.3%) | 61 (40.7%) | 223 (47.9%) | <0.001 |

| Vascular disease | 502 (50%) | 157 (40.6%) | 74 (49.3%) | 271 (58.2%) | <0.001 |

| Abnormal renal function | 145 (14.5%) | 45 (11.6%) | 24 (16%) | 76 (16.3%) | 0.123 |

| Abnormal liver function | 101 (10.1%) | 12 (3.1%) | 20 (13.3%) | 69 (14.8%) | <0.001 |

| Family history | |||||

| Family history of coronary artery disease early development | 230 (22.9%) | 78 (20.2%) | 43 (28.7%) | 109 (23.4%) | 0.106 |

| Hypertension in relatives | 516 (51.4%) | 231 (59.7%) | 84 (56%) | 201 (43.1%) | <0.001 |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of AF + HF severity.

| Parameters | Total cohort (n=1003) | AF-HFpEF (n=387) | AF-HFmEF EF (n=150) | AF-HFrEF (n=466) | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHF duration, months | 40 (12 : 96) | 48 (22.5 : 100) | 36 (12 : 72) | 48 (12 : 96) | 0.265 |

| AF duration, months | 48 (15 : 96) | 50 (24 : 108) | 38 (12 : 89) | 40 (12 : 96) | 0.042 |

| Age at AF debut | 62 (54.25 : 70.7) | 64.4 (57.9 : 72.6) | 60.8 (50.88 : 70.22) | 59.9 (51.5 : 68.55) | <0.0001 |

| Age at HF debut | 62.1 (54.7 : 70.1) | 64 (57.5 : 72.9) | 61.65 (54.15 : 70.3) | 60.9 (52.9 : 67.8) | <0.0001 |

| AF debuted after HF | 478 (47.7%) | 197 (50.9%) | 58 (38.7%) | 223 (47.9%) | 0.039 |

| Type of AF | |||||

| Paroxysmal | 276 (27.5%) | 144 (37.2%) | 30 (20%) | 102 (21.9%) | <0.001 |

| Nonparoxysmal | 727 (72.5%) | 243 (62.8%) | 120 (80%) | 364 (78.1%) | |

| Blood pressure | |||||

| Systolic | 130 (120 : 140) | 140 (130 : 150) | 130 (120 : 140) | 120 (110 : 140) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic | 80 (70 : 90) | 80 (80 : 90) | 80 (70 : 90) | 80 (70 : 80) | 0.01 |

| Heart rate | |||||

| Rate (beats/min) | 84 (70 : 100) | 80 (68 : 90) | 85.5 (75.25 : 90.75) | 84 (75 : 97) | 0.226 |

| Rate > 100, n (%) | 327 (32.6%) | 103 (26.6%) | 56 (37.3%) | 168 (36.1%) | 0.005 |

| CHA2DS2-VASc score, Me (IQR) | 4 (3 : 5) | 5 (3 : 6) | 4 (3 : 5) | 4 (2 : 5) | <0.001 |

| HAS-BLED, Me (IQR) | 3 (2 : 4) | 5 (3 : 6) | 4 (3 : 5) | 4 (2 : 5) | <0.001 |

Table 3.

The results of laboratory tests and instrumental examinations of patients at the time of inclusion with the study.

| Parameters | Total cohort (n=1003) | AF-HFpEF (n=387) | AF-HFmEF EF (n=150) | AF-HFrEF (n=466) | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 40 (35 : 58) | 60 (55 : 65) | 43 (40 : 46) | 34 (29 : 37) | <0.0001 |

| Aortic insufficiency | 410 (50.9%) | 166 (42.9%) | 57 (38%) | 187 (40.1%) | 0.529 |

| Mitral insufficiency | 805 (80.3%) | 310 (80.1%) | 123 (82%) | 372 (79.8%) | 0.841 |

| Pulmonary insufficiency | 367 (36.6%) | 135 (34.9%) | 52 (34.7%) | 180 (38.6%) | 0.459 |

| Tricuspidal insufficiency | 766 (76.4%) | 284 (73.4%) | 121 (80.7%) | 361 (77.5%) | 0.153 |

| Left ventricular end diastolic dimension, cm | 5.6 (5 : 6.3) | 5 (4.6 : 5.3) | 5.9 (5.3 : 6.38) | 6.2 (5.7 : 6.91) | <0.0001 |

| Left ventricular end systolic dimension, cm | 4.1 (3.2 : 5.05) | 3.1 (3 : 3.6) | 4.5 (4 : 5) | 5 (4.5 : 5.7) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiothoracic index (%) | 57 (54 : 62) | 56.5 (53 : 61) | 60 (55 : 63) | 57 (55 : 63) | 0.086 |

| Ventricular extrasystoles, total | 122 (17 : 775.5) | 40 (8 : 327.25) | 79 (13 : 1163) | 277 (78.5 : 1319) | 0.029 |

| Laboratory analysis | |||||

| BNP | 300 (158.25 : 602.48) | 245.5 (152.25 : 429.75) | 317.5 (142.25 : 507.15) | 490.5 (186.52 : 941.75) | 0.008 |

| NT-proBNР | 536 (349.5 : 1085) | 562 (425 : 968) | 338 (327 : 353.5) | 1484 (289 : 2866) | 0.01 |

| International normalised ratio | 1.27 (1.04 : 2) | 1.15 (1 : 1.67) | 1.29 (1.1 : 1.9) | 1.42 (1.1 : 2.08) | 0.019 |

| D-dimer | 1.2 (0.35 : 4.75) | 1.38 (0.22 : 109) | 2 (0.24 : 187) | 1.1 (0.49 : 1.65) | 0.048 |

Patients with preserved ejection function were significantly older (median age, 72 years (IQR 63 : 78) vs. 67 years (58 : 75) in the AF-HFmrEF group and 66 years (58 : 75) in the AF-HFrEF group). The percentage of women was the highest (65.4%) in the AF-HFpEF group and the lowest in the AF-HFrEF group (25.8%). Approximately 75% of patients with AF-HFpEF had never smoked, while only 50% of patients in the AF-HFmEF and AF-HFrEF groups were never-smokers (p=0.003).

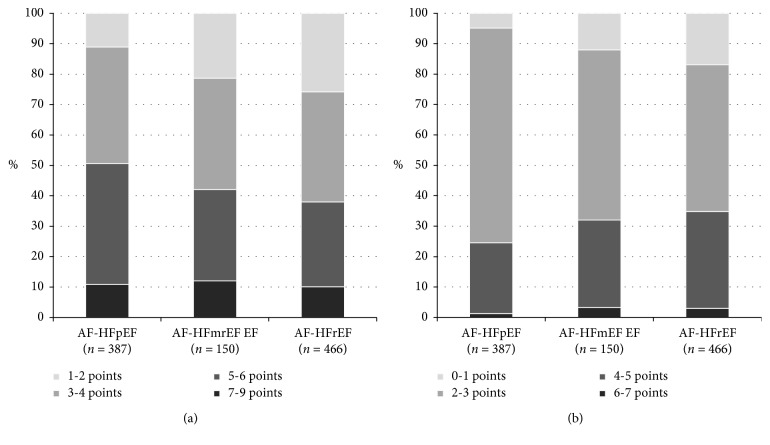

The groups were comparable in terms of previous history of stroke (15, 14.7, and 16.7% in the AF-HFpEF, AF-HFmrEF, and AF-HFrEF groups, respectively; p=0.747) and significantly differed in terms of their history of infarction (25.3, 40.7, and 47.9%, respectively; p < 0.001). While in the AF-HFpEF and AF-HFrEF subgroups, patients developing AF already had CHF (50.9 and 47.9%, respectively), and the percentage of these patients in the AF-HFmrEF group was significantly lower (38.7%; p=0.039). CHF duration was comparable between the groups, while the oldest age of CHF onset was observed for the AF-HFpEF group (64 years; IQR 57.5 : 72.9). Regardless of the oldest age of AF onset (64.4 years; IQR 57.9 : 72.6), patients in the AF-HFpEF subgroup had the longest duration of AF (50 months; IQR 24 : 108). The percentage of patients with paroxysmal AF in the AF-HFpEF group was almost twice as high as that in the other two groups (37.2% vs. 20% in the AF-HFmrEF and 21.9% in the AF-HFrEF group). The rate control strategy was most effective in the AF-HFpEF group: the heart rate was >100 bpm only in 26.6% of patients (p=0.005 as compared to the other two groups). The groups differed in terms of risks of stroke and bleeding (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Risk assessment scales in studied subgroups. (a) CHA2DS2-VASc score. (b) HAS-BLED score.

At baseline, the therapy differed significantly for patients in three subgroups (Table 4). Although the rate control strategy was prevailing in all the three groups, the percentage of patients treated using the rhythm control strategy was the lowest in the AF-HFpEF group (27.9%) and the highest in the AF-HFpEF group (40.6%) (p < 0.001). Chronic anticoagulant therapy was given to 79.3% of patients in the AF-HFmrEF group, 70.8% of patients in the AF-HFpEF group, and 63.3% of patients in the AF-HFrEF group (p < 0.001).

Table 4.

Medications for AF and CHF in studied groups.

| Parameters | Total cohort (n=1003) | AF-HFpEF (n=387) | AF-HFmEF EF (n=150) | AF-HFrEF (n=466) | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment strategy for AF | |||||

| Rhythm control | 339 (33.8%) | 157 (40.6%) | 52 (34.7%) | 130 (27.9%) | <0.001 |

| Rate control | 664 (66.2%) | 230 (59.4%) | 98 (65.3%) | 336 (72.1%) | |

| Rational therapy of CHF | 396 (39.5%) | 106 (27.4%) | 78 (52%) | 212 (45.5%) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 830 (82.8%) | 301 (77.8%) | 136 (90.7%) | 393 (84.3%) | <0.001 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 255 (25.4%) | 123 (31.8%) | 37 (24.7%) | 95 (20.4%) | <0.001 |

| RAS antagonist | 218 (21.7%) | 116 (30%) | 27 (18%) | 75 (16.1%) | <0.001 |

| Aldosterone blocker | 642 (64%) | 164 (42.4%) | 116 (77.3%) | 362 (77.7%) | <0.001 |

| Statin | 606 (60.4%) | 252 (65.1%) | 89 (59.3%) | 265 (56.9%) | 0.046 |

| Diuretic | 883 (88%) | 332 (85.8%) | 131 (87.3%) | 420 (90.1%) | 0.137 |

| Digoxin | 360 (35.9%) | 101 (26.1%) | 53 (35.3%) | 206 (44.2%) | <0.001 |

| Oral anticoagulant (warfarin or/and NOAC) | 688 (68.6%) | 274 (70.8%) | 119 (79.3%) | 295 (63.3%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 403 (40.2%) | 157 (40.6%) | 66 (44%) | 180 (38.6%) | 0.491 |

| NOAC | 335 (33.4%) | 140 (36.2%) | 55 (36.7%) | 140 (30%) | 0.107 |

| Oral antiplatelet, total | 466 (46.5%) | 177 (45.7%) | 61 (40.7%) | 228 (48.9%) | 0.200 |

3.2. One-Year Follow-Up

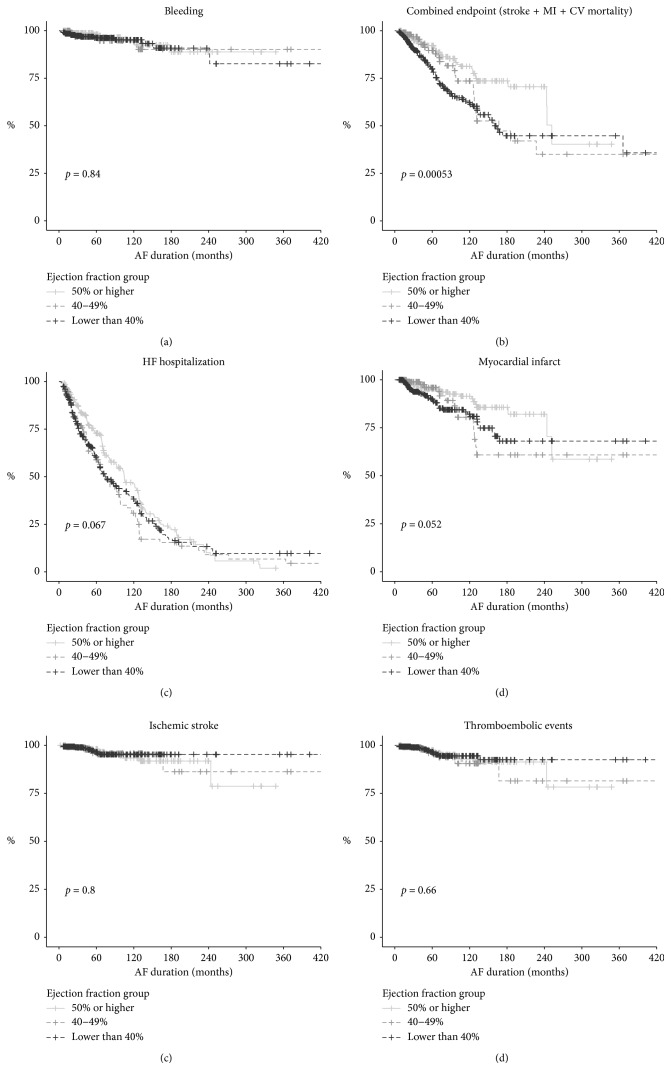

During the one-year follow-up, 574 (57.2%) patients were hospitalized because of decompensated CHF at least once. The maximum frequency of hospitalization was observed for the AF-HFmrEF group (66%); the minimum, for the AF-HFpEF group (52.7%) (Table 5; Figure 2).

Table 5.

Main outcomes in AF-CHF subgroups.

| Endpoints | Total cohort (n=1003) | AF-HFpEF (n=387) | AF-HFmrEF EF (n=150) | AF-HFrEF (n=466) | p level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization for worsening of heart failure | 574 (57.2%) | 204 (52.7%) | 99 (66%) | 271 (58.2%) | 0.017 |

| Cardiovascular mortality | 102 (10.2%) | 16 (4.1%) | 14 (9.3%) | 72 (15.5%) | <0.001 |

| Thromboembolic events | 34 (3.4%) | 14 (3.6%) | 7 (4.7%) | 13 (2.8%) | 0.451 |

| Ischemic stroke | 27 (2.7%) | 12 (3.1%) | 4 (2.7%) | 11 (2.4%) | 0.776 |

| Myocardial infarct | 101 (10.1%) | 26 (6.7%) | 20 (13.3%) | 55 (11.8%) | 0.014 |

| Combined point (stroke, IM, and CV death) | 201 (17%) | 49 (12.7%) | 33 (22%) | 119 (25.5%) | <0.001 |

| Bleeding rate | 39 (3.9%) | 15 (3.9%) | 7 (4.7%) | 17 (3.6%) | 0.815 |

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for the studied subgroups.

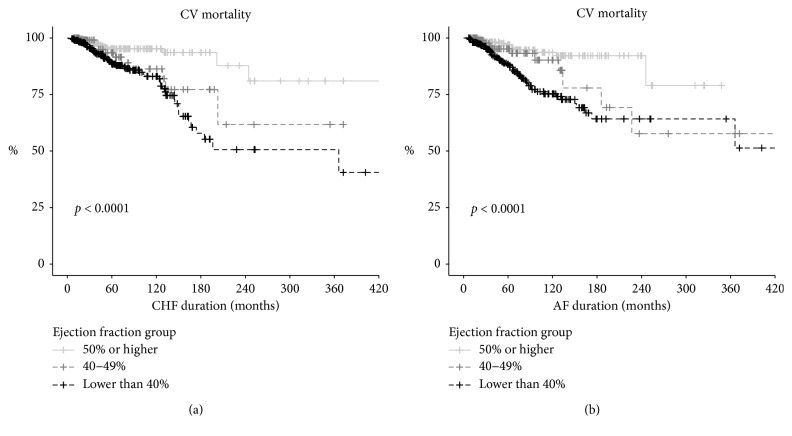

In our cohort, the cardiovascular mortality rate went up as the EF decreased during the first year of follow-up: it was 4.1% in the AF-HFpEF group, 9.3% in the AF-HFmrEF group, and 15.5% in the AF-HFrEF group (p < 0.001). Significant variation in the dynamics of the mortality risk in groups depending on duration of AF and HF is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

CV mortality probability.

The rate of all thromboembolic events in the total cohort was 3.4%; the rate of ischemic stroke was 2.7%. It is noteworthy that some patients (10 (1% of the total cohort)) experienced two different thromboembolic events (e.g., stroke and PATE) during the follow-up period.

The myocardial infarction rate in the total cohort was 101 (10.1%). Most of the infarctions were recurrent (96 out of 101). In patients with myocardial infarction experience, the rate of recurrent myocardial infarction was 25.1%, while the rate of MI among patients having no history of MI was as low as 0.8% (p < 0.001) during the follow-up. The significant variation in the myocardial infarction rate was also observed in the groups of patients with different ejection fractions: the AF-HFpEF patients were characterized by the lowest rate (6.7%).

A total of 39 cases of bleeding (3.9% of the total cohort) were documented during the follow-up: 13 (1.3%) cases of gastrointestinal bleeding, 6 (0.6%) cases of hemoptysis, 5 (0.5%) cases of intracranial hemorrhage, and 14 (1.5%) of cases of bleeding of other locations.

We conducted a search and analysis of factors for the primary and secondary points for three groups: AF-HFrEF, AF-HFmrEF, and AF-HFpEF. An analysis of factors significantly associated with outcomes led to the conclusion that the risk factors for adverse outcomes differ significantly for groups with different EFs (Table 6–8).

Table 6.

Univariate regression logistic analysis of the risk of hospitalization due to decompensation of HF.

| Group of factors | Factor | AF-HFpEF | AF-HFmrEF | AF-HFrEF | |||

| OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | ||

|

| |||||||

| Laboratory tests | LDH | 1.007 (1.004–1.011) | <0.001 | ||||

| Total bilirubin | 1.035 (1.005–1.07) | 0.031 | |||||

| Kreatinin | 1.008 (1.002–1.014) | 0.01 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Demography | Age > 65 years | 2.329 (1.462–3.745) | <0.001 | 1.736 (1.17–2.584) | 0.006 | ||

| Female gender | 1.866 (1.198–2.921) | 0.006 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Habits and lifestyle | Smoking (ever) | 1.852 (1.073–3.236) | 0.028 | ||||

| Bad habits | 2.009 (1.107–3.723) | 0.023 | |||||

| Alcohol usage history | 1.37 (1.038–1.828) | 0.028 | |||||

| Level of physical activity | 0.549 (0.274–1.081) | 0.085 | 0.616 (0.399–0.944) | 0.027 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Symptoms and syndromes | The number of specific signs of HF | 1.482 (1.146–1.946) | 0.003 | ||||

| Increase of venous pressure | 2.383 (1.02–5.847) | 0.048 | |||||

| The number of typical symptoms of HF | 2.275 (1.1–4.844) | 0.028 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Concomitant diseases | Diabetes mellitus | 1.733 (1.048–2.908) | 0.034 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| CV system characteristics | Arterial hypertension | 2.347 (1.524–3.663) | <0.001 | ||||

| Duration of arterial hypertension | 1.03 (1.002–1.061) | 0.044 | |||||

| Degree of tricuspid insufficiency | 1.408 (1.027–1.949) | 0.036 | |||||

| Degree of aortal insufficiency | 1.721 (1.074–2.865) | 0.028 | |||||

| Degree of pulmonary insufficiency | 3.69 (1.46–10.87) | 0.01 | |||||

| Mitral insufficiency | 1.543 (0.937–2.54) | 0.087 | |||||

| Hemodynamically significant coronary artery stenosis | 2.166 (1.276–3.8) | 0.005 | |||||

| Cardiothoracic index (%) | 1.138 (1.047–1.244) | 0.003 | |||||

| Vascular disease | 1.73 (1.126–2.673) | 0.013 | |||||

| Prior stroke or TIA or thromboembolism | 1.866 (1.198–2.921) | 0.006 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Therapy | Regular use of antiarrhythmic drugs | 0.622 (0.393–0.978) | 0.041 | ||||

| Regular use of ACE inhibitors | 0.582 (0.371–0.907) | 0.017 | |||||

| Permanent AF therapy with calcium channel blockers | 0.505 (0.311–0.812) | 0.005 | |||||

| Regular use of angiotensin II receptor blocker | 0.466 (0.288–0.745) | 0.002 | 0.587 (0.331–1.01) | 0.06 | |||

| Regular use of anticoagulants | 0.389 (0.257–0.587) | <0.001 | |||||

| Permanent AF therapy with beta-blockers | 0.279 (0.152–0.496) | <0.001 | |||||

| Rational therapy of HF | 0.409 (0.271–0.611) | <0.001 | |||||

| Regular use of aldosterone antagonist | 0.584 (0.361–0.942) | 0.027 | |||||

| Regular use of NOAC | 0.588 (0.377–0.907) | 0.017 | |||||

| Rate control strategy (versus rhythm control strategy) | 1.779 (1.156–2.747) | 0.009 | 0.283 (0.125–0.599) | 0.001 | |||

|

| |||||||

| AF/HF features | HF developed after AF debut | 2.002 (1.049–3.879) | 0.037 | ||||

| AF duration | 1.005 (1.001–1.01) | 0.022 | |||||

| HF duration | 1.005 (1.002–1.009) | 0.003 | |||||

| EF | 0.958 (0.922–0.995) | 0.026 | |||||

| Persistent form of AF (versus paroxysmal form) | 0.464 (0.296–0.722 | 0.001 | 2.755 (1.451–5.405) | 0.002 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Scales and risks | CHA2DS2-VASc | 1.393 (1.215–1.608) | <0.001 | 1.191 (0.981–1.46) | 0.083 | 1.215 (1.089–1.359) | 0.001 |

| HAS-BLED | 1.461 (1.174–1.836) | 0.001 | 1.196 (1.014–1.414) | 0.035 | |||

Table 7.

Univariate regression logistic analysis of the risk of cardiovascular mortality.

| Group of factors | Factor | AF-HFpEF | AF-HFmrEF | AF-HFrEF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | ||

| Laboratory tests | Total cholesterol | 0.515 (0.291–0.851) | 0.014 | ||||

| International normalised ratio | 2.825 (1.353–7.937) | 0.013 | |||||

| NT-proBNР | 1.001 (1–1.002) | 0.055 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Habits and lifestyle | Balanced diet | 0.355 (0.102–1.279) | 0.099 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Symptoms and syndromes | Anemia | 5.618 (1.799–16.667) | 0.002 | 4.219 (1.156–14.286) | 0.022 | ||

| The number of specific signs of HF (pressure in the jugular veins, gallop rhythm, mixing the top of the jolt, wheezing in the lungs, and congestion in the lungs) | 2.299 (1.441–3.676) | <0.001 | 1.567 (0.924–2.653) | 0.089 | 1.497 (1.163–1.927) | 0.002 | |

| The number of typical symptoms of HF (dyspnea, fatigue, orthopnea, low effort tolerance, fatigue, edema, and apnoea) | 1.961 (1.335–2.941) | 0.001 | 1.346 (1.121–1.629) | 0.002 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Concomitant diseases | Endoscopy presence of erosive ulcerative lesions gastrointestinal mucosa | 2.353 (0.951–5.464) | 0.053 | ||||

| Abnormal liver function | 5.291 (1.425–18.519) | 0.009 | |||||

| Renal disease | 4.184 (1.245–12.5) | 0.013 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| CV system characteristics | Aortic valve insufficiency | 2.907 (0.915–10.101) | 0.075 | ||||

| Arterial hypertension | 2 (1.089–3.891) | 0.032 | |||||

| The duration of arterial hypertension (years) | 1.066 (1.017–1.116) | 0.006 | |||||

| Cardiothoracic index (%) | 1.597 (1.133–2.841) | 0.036 | 1.161 (1.053–1.294) | 0.004 | |||

| History of infarction and/or stroke | 3.521 (1.222–11.494) | 0.024 | |||||

| Degree of pulmonary insufficiency | 2.725 (1.269–5.882) | 0.009 | |||||

| Right atrium enlargement | 3.546 (1.235–14.925) | 0.04 | |||||

| Degree of tricuspid insufficiency | 1.37 (0.983–1.908) | 0.061 | |||||

| Echocardiographic signs of myocardial infarct (cicatricial changes and local conduction disturbance zones) | 3.636 (1.233–10.526) | 0.016 | 1.957 (1.129–3.509) | 0.02 | |||

| Enlarged pulmonary trunk | 2.375 (1.224–4.608) | 0.01 | |||||

| Prior major bleeding | 6.494 (2.174–19.231) | 0.001 | 3.891 (1.073–13.158) | 0.03 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Therapy | Regular use of anticoagulants | 0.389 (0.225–0.666) | 0.001 | ||||

| Regular use of NOAC | 0.42 (0.202–0.806) | 0.013 | |||||

| Regular use of peripheral vasodilators | 4.587 (1.695–11.905) | 0.002 | |||||

| Regular use of statins | 0.254 (0.083–0.724) | 0.011 | 0.627 (0.366–1.08) | 0.089 | |||

| Regular use of ACE inhibitors | 0.22 (0.069–0.84) | 0.015 | |||||

| Permanent AF therapy with beta-blockers | 0.404 (0.213–0.791) | 0.006 | |||||

| Permanent AF therapy with calcium channel blockers | 0.172 (0.009–0.872) | 0.091 | |||||

| Rational therapy of HF | 0.432 (0.238–0.757) | 0.004 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| AF/HF features | HF developed after AF debut | 0.463 (0.209–0.987) | 0.05 | ||||

| Age of AF debut | 1.037 (1.011–1.067) | 0.007 | |||||

| Heart rate more than 100 beats per second | 4.545 (0.917–33.333) | 0.081 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Scales and risks | CHA2DS2-VASc | 1.385 (1.029–1.869) | 0.031 | 1.163 (1.01–1.342) | 0.037 | ||

| HAS-BLED | 2.105 (1.305–3.425) | 0.002 | 1.938 (1.238–3.175) | 0.005 | 1.37 (1.098–1.715) | 0.006 | |

Table 8.

Univariate regression logistic analysis of the risk of myocardial infarction.

| Group of factors | Factor | AF-HFpEF | AF-HFmrEF | AF-HFrEF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | OR (2.5–97.5) | p value | ||

| Laboratory tests | LDH | 1.006 (1.002–1.01) | 0.004 | 1.007 (1.001–1.014) | 0.046 | ||

| Triglycerides | 1.566 (1.11–2.362) | 0.02 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Demography | Age> 65 years | 3.115 (1.044–13.398) | 0.071 | 3.27 (1.099–12.063) | 0.047 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Habits and lifestyle | Level of physical activity | 0.455 (0.173–1.069) | 0.086 | ||||

| Unbalanced diet | 4.714 (1.363–29.721) | 0.038 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Symptoms and syndromes | Signs of arterial hypertension (accent of the second tone on the pulmonary artery and left ventricular hypertrophy) | 3.242 (1.269–9.964) | 0.022 | 10.108 (1.969–185.253) | 0.027 | ||

| Anemia | 1.964 (0.84–4.21) | 0.097 | |||||

| The number of specific signs of HF (pressure in the jugular veins, gallop rhythm, mixing the top of the jolt, wheezing in the lungs, and congestion in the lungs) | 1.87 (1.256–2.754) | 0.002 | 1.962 (1.237–3.208) | 0.005 | |||

|

| |||||||

| Concomitant diseases | Abnormal liver function | 4.417 (1.34–13.764) | 0.011 | ||||

|

| |||||||

| CV system characteristics | Aortic valve insufficiency | 0.418 (0.148–1.045) | 0.082 | 7.368 (2.457–27.37) | 0.001 | 3.427 (1.565–7.683) | 0.002 |

| Vascular disease | 8.226 (3.029–28.777) | <0.001 | |||||

| ECG abnormalities | 10.88 (2.92–70.815) | 0.002 | |||||

| History of infarction and/or stroke | 9.643 (3.547–33.762) | <0.001 | |||||

| History of cardiomyopathy | 1.591 (0.827–2.635) | 0.096 | 1.68 (0.88–2.999) | 0.086 | 1.528 (0.947–2.371) | 0.068 | |

| Pulmonary insufficiency | 6.283 (2.553–17.746) | <0.001 | 2.632 (0.963–7.412) | 0.06 | 0.499 (0.248–0.948) | 0.041 | |

| Right atrium enlargement | 2.632 (0.963–7.412) | 0.06 | 0.499 (0.248–0.948) | 0.041 | |||

| Family history of early ischemic heart disease | 0.256 (0.039–0.972) | 0.08 | 1.911 (1.009–3.569) | 0.044 | |||

| Hemodynamically significant coronary artery stenosis | 3.316 (1.1–9.569) | 0.028 | 2.036 (1.025–3.888) | 0.035 | |||

| History of coronary arteries stenting | 3.311 (1.131–8.591) | 0.019 | 4.727 (1.528–14.174) | 0.006 | 2.043 (0.99–4.011) | 0.044 | |

| Thromboembolism of pulmonary artery | 5.873 (0.809–29.014) | 0.041 | 5.7 (1.041–28.378) | 0.032 | |||

| Degree of tricuspid insufficiency | 1.601 (1.105–2.323) | 0.013 | |||||

| Venous thrombosis of the lower extremities | 4.543 (0.966–16.216) | 0.03 | 9 (0.76–127.873) | 0.078 | |||

| Echocardiographic signs of myocardial infarct (cicatricial changes and local conduction disturbance zones) | 9.509 (3.986–24.457) | <0.001 | 10.51 (2.822–68.395) | 0.002 | 4.459 (2.144–10.482) | <0.001 | |

| Enlarged pulmonary trunk | 4.165 (1.47–11.651) | 0.006 | 9.797 (2.931–39.334) | <0.001 | 2.727 (1.323–5.652) | 0.006 | |

|

| |||||||

| Therapy | Regular use of rivaroxaban | 0.114 (0.006–0.79) | 0.057 | ||||

| Regular use of digoxin | 0.324 (0.072–1.051) | 0.088 | |||||

| Regular use of ACE inhibitors | 0.407 (0.147–1.158) | 0.084 | |||||

| Regular use of ivabradin | 6.313 (1.516–24.687) | 0.007 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| AF/HF features | HF developed after AF debut | 3.154 (1.026–11.799) | 0.058 | 0.471 (0.19–1.101) | 0.089 | ||

| Age of HF debut | 1.051 (1.005–1.101) | 0.033 | 1.045 (0.996–1.102) | 0.082 | |||

| Persistent form of AF | 0.158 (0.009–0.752) | 0.071 | |||||

| Heart rate at rest | 0.382 (0.143–0.945) | 0.043 | |||||

|

| |||||||

| Scales and risks | CHA2DS2-VASc | 1.372 (1.077–1.752) | 0.01 | 1.398 (1.069–1.865) | 0.017 | ||

| HAS-BLED | 1.609 (1.09–2.432) | 0.019 | |||||

The number of specific signs of HF included pressure in the jugular veins, gallop rhythm, mixing the top of the jolt, wheezing in the lungs, and congestion in the lungs. Increase of venous pressure included jugular venous distention, pulmonary edema, pulmonary artery enlargement, and enlarged right heart. The number of typical symptoms of HF included dyspnea, fatigue, orthopnea, low effort tolerance, fatigue, edema, and apnoea. Bad habits included excess weight, diet, sedentary lifestyle, and hypercholesterolemia.

Among the demographic characteristics, gender was a significant predictor only in the HFpEF group. In this group, women were hospitalized significantly more often than men (79.6% vs. 35.1%). However, it is important to mention that the sex ratios in the groups differed significantly: women predominated in the HFpEF group, while only 25% of patients in the HFrEF group were female. Habits and lifestyle were significant for the HFrEF group. Alcohol consumption habits and physical activity level affected the hospitalization frequency. It is interesting that specific symptoms of heart failure were found to be significantly associated with the frequency of rehospitalization for patients with 40% < EF < 50%. However, they were not significant for patients with HFmrEF. The predictors related to echocardiographic and clinical characteristics of the cardiovascular status were subdivided into four groups. Presence and signs of persistent hypertension were significant both for the HFpEF and HFrEF subgroups. Signs of old myocardial infarction and concomitant surgeries were significant only for the HFrEF group. Signs of aortic, tricuspid, and pulmonic regurgitations were found to be predictors for HFpEF. Mitral valve dysfunction was the only factor being significant for patients with HFmrEF.

4. Discussion

The objective of our survey was to identify the features of the course and management of chronic heart failure in patients with atrial fibrillation and to collect the data on compliance with clinical guidelines and on long-term prevalence of this condition in Russia. The primary endpoint in our study was hospitalization because of decompensated heart failure. We demonstrated that the frequency of rehospitalization during the same year was 57.2%. Patients with HFmrEF were hospitalized significantly more often. The mortality, rates of thromboembolic events, and bleeding were selected as secondary endpoints. We found that reduced ejection fraction elevates the risk of cardiovascular mortality, while the risk of ischemic stroke does not increase. Using stroke, myocardial infarction, and CV mortality as a composite endpoint, we revealed that patients with HFpEF have significantly lower risks as compared to those with HFmrEF and HFrEF.

Several epidemiological studies of heart failure have been carried out in Russia. The largest ones are the EPOKHA-CHF (conducted more than a decade ago) [32, 33] and the TOPCAT study [17, 34, 35]. As reported in the EPOKHA-CHF epidemiological study, the prevalence of CHF in Russia is 11.7% of the overall population, and 56.8% of these patients have HFpEF. In our study, only 38.6% of patients had HFpEF. This fact demonstrates that the AF + HF comorbidity is characterized by more severe course of HF. In several U.S. community-based samples from 1990 to 2009, we observed divergent trends of decreasing HFrEF and increasing HFpEF incidence, with stable overall HF incidence and high risk for mortality [36]. In our study, the ratio between AF-HPrEF + AF-HPmrEF vs. AF-HPpEF groups is similar to the ratio in the American cohort. However, in the HPpEF group in our study, women predominate at a ratio of 2 to 1, and in the study by Tsao et al., there are more men by 20%.

We found that adherence to rational therapy of CHF as well as adherence to anticoagulant therapy is the key factors, reducing the risk of rehospitalization and cardiovascular mortality in patients with HFrEF. However, patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) were taking aldosterone antagonists almost twice less often. However, even in this group, therapy adherence was significantly higher than that in the Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF) [37]. The data on using aldosterone antagonist therapy in AF + HFpEF patients are rather controversial. The TOPCAT trial involving 1,765 patients demonstrated that new-onset AF was not influenced by spironolactone. However, the meta-analysis by Neefs et al. [38] involving 5,332 patients with either existing or new-onset AF showed that aldosterone antagonist therapy reduced the risk of development or recurrence of AF. This conclusion was also valid for the AF + HF subgroup. Nevertheless, our findings indicate that patients with AF + HF comorbidity in Russia are prescribed aldosterone antagonist therapy regardless of ejection fraction. In this study, we found that aldosterone antagonist therapy in the HFrEF group significantly reduced the risk of rehospitalization because of subcompensated HF.

The HFmrEF group differed significantly from the other two groups with respect to the primary endpoint. In this group, the percentage of rehospitalized patients was substantially higher. We revealed that each EF group was characterized by its own factors associated with the primary endpoint.

Therapy received by the patients had a substantial effect on hospitalization frequency. For patients with HFrEF, the most important factor was whether or not they received anticoagulant therapy and its type. Rational therapy (RAS antagonist + beta-blocker + aldosterone blocker) substantially reduced the risk of rehospitalization. In the AF-CHF, prospective multicenter trial was found that beta-blockers were associated with significantly lower mortality but not hospitalizations in patients with HFrEF and AF, irrespective of the pattern or burden of AF. These results diverged from an individual patient-level meta-analysis conducted by Kotecha et al. [23], which included data from 10 randomized trials of beta-blockers versus placebo in HFrEF. Rienstra et al's main finding of meta-analysis indicates that the effect of beta-blockers in patients with HF and AF is significantly different from the effect of these drugs in patients with HF and sinus rhythm. Indeed, beta-blockers were not found to have a favorable effect on HF hospitalizations or mortality [26].

Therapy subtypes were found to significantly affect the mortality rate only in the HFrEF group. Similar to the primary endpoint, administration of novel oral anticoagulants, adherence to β-blocker therapy, and rational therapy of HF reduced the risk of mortality during the one-year follow-up.

Cardiovascular indicators were found to be significantly associated with mortality only for the HFpEF and HFrEF groups but not for HFmrEF patients. The only category of factors that was associated with mortality for all three HF groups included laboratory values attesting to renal insufficiency, anemia, and the BNP level. Furthermore, it was found that chronic kidney disease in HFmrEF patients abruptly increases the risk of mortality.

In our study, we revealed no intergroup differences in thromboembolism. By the time of study initiation, the mean risk of thromboembolism assessed using the CHA2DS2-VASc score was significantly higher only in the HFpEF group. This scale was a significant predictor of developing thromboembolism only for this group. An association between HF subtype and thromboembolic events was assessed under actual clinical conditions in the AF-HF substudy of the PREFER trial. The results demonstrated that the HF subtype predicts the residual risk of thromboembolism, and there is an inverse association between LVEF and hard thromboembolic endpoints (ischemic stroke and MACCE).

In this study, we revealed no intergroup difference in the bleeding rate. The low frequency of events did not allow us to analyze the risk factors for bleeding.

Our objective was to study the differences between the EF groups and to identify predictors of unfavorable outcomes using the real-world data. We investigated how the current clinical practice in Russia complies with the international guidelines. The revealed discrepancy was used for the analysis conducted, so that the Russian guidelines could be updated. Our study was the first one in this series and included patients from 23 Russian provinces.

This survey has a number of limitations. Despite the large pool of patients included in it, the groups being compared had some significant baseline differences because of population-wide features of Russian patients. Nevertheless, we have accumulated a large body of real-world data that show the current situation in clinical practice for the local data and can be compared to the data for patients from other countries.

5. Conclusions

All three ejection fraction subgroups are characterized by their own features of the course of AF + HF comorbidity; the risks of unfavorable outcomes differ for these subgroups. Reduced ejection fraction increases the risk of cardiovascular mortality but not the risk of thromboembolic events (such as stroke and systemic embolism). Rational therapy of CHF and adherence to anticoagulant therapy are the key factors reducing the risk of rehospitalization and cardiovascular mortality in patients with HFrEF. The rate control strategy has some advantages related to hospitalization because of decompensated CHF for patients with HFrEF, while the rhythm control strategy is beneficial for patients with HFpEF.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate all Russian local cardiologists for their cooperation and help in organisation of the register: Ageev F. T. (Moscow), Arkhipov M. V. (Ekaterinburg), Barbarash O. L. (Kemerovo), Boldueva S. A. (Saint Petersburg), Borovkova N. Yu. (Nizhny Novgorod), Govorin A. V. (Chita), Golitsyn S. P. (Moscow), Demidov A. A. (Astrakhan), Zubkov S. K. (Smolensk), Kolbasnikov S. V. (Tver), Kuklin S. G. (Irkutsk), Libis R. A. (Orenburg), Matyushin V. G. (Krasnoyarsk), Nevzorova V. A. (Vladivostok), Nedbaykin A. M. (Bryansk), Nikolayeva I. E. (Ufa), Nikulina S. Yu. (Krasnoyarsk), Ostroumova O. D. (Moscow), Stryuk R. I. (Moscow), Urvantseva I. A. (Surgut), Filippenko N. G. (Kursk), Chukayeva I. I. (Moscow), Shalaev S. V. (Tyumen), Schwarz Yu. G. (Saratov), and Shubik Yu. V. (Saint Petersburg).

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Tomlin A. M., Lloyd H. S., Tilyard M. W. Atrial fibrillation in New Zealand primary care: prevalence, risk factors for stroke and the management of thromboembolic risk. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2017;24(3):311–319. doi: 10.1177/2047487316674830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siller-Matula J. M., Pecen L., Patti G., et al. Heart failure subtypes and thromboembolic risk in patients with atrial fibrillation: the PREFER in AF-HF substudy. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;265:141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maisel W. H., Stevenson L. W. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and rationale for therapy. American Journal of Cardiology. 2003;91(1):2–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)03373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zakeri R., Chamberlain A. M., Roger V. L., Redfield M. M. Temporal relationship and prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in heart failure patients with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2013;128(10):1085–1093. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.113.001475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patel R. B., Vaduganathan M., Shah S. J., Butler J. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights into mechanisms and therapeutics. Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2017;176:32–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Deursen V. M., Urso R., Laroche C., et al. et al. Co-morbidities in patients with heart failure: an analysis of the European Heart Failure Pilot Survey. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2014;16(1):103–111. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ponikowski P., Voors A. A., Anker S. D., et al. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. European Heart Journal. 2016;37(27):2129–2200. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirchhof P., Benussi S., Kotecha D., et al. ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. European Heart Journal. 2016;37(38) doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braunschweig F., Cowie M. R., Auricchio A. What are the costs of heart failure? Europace. 2011;13(2):13–17. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wodchis W. P., Bhatia R. S., Leblanc K., Meshkat N., Morra D. A review of the cost of atrial fibrillation. Value in Health. 2012;15(2):240–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Santhanakrishnan R., Wang N., Larson M. G., et al. Atrial fibrillation begets heart failure and vice versa. Circulation. 2016;133(5):484–492. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.018614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smit M. D., Moes M. L., Maass A. H., et al. The importance of whether atrial fibrillation or heart failure develops first. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2012;14(9):1030–1040. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfs097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takagi T., Satake N., Shibata S. The inhibitory action of FR 34235 (A new Ca2+ entry blocker) as compared to nimodipine and nifedipine on the contractile response to norepinephrine, potassium and 5-hydroxytryptamine in rabbit basilar artery. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1983;90(2-3):297–299. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(83)90254-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hoppe U. C., Casares J. M., Eiskjær H., et al. Effect of cardiac resynchronization on the incidence of atrial fibrillation in patients with severe heart failure. Circulation. 2006;114(1):18–25. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.106.614560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Senni M., Paulus W. J., Gavazzi A., et al. New strategies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the importance of targeted therapies for heart failure phenotypes. European Heart Journal. 2014;35(40):2797–2815. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal P., Almarzooq Z. I., Cheung J., et al. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights on a unique clinical phenotype from a nationally-representative United States cohort. International Journal of Cardiology. 2018;266:112–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cikes M., Claggett B., Shah A. M., et al. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6(8):689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lam C. S. P., Rienstra M., Tay W. T., et al. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2017;5(2):92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sobue Y., Watanabe E., Lip G. Y. H., et al. Thromboembolisms in atrial fibrillation and heart failure patients with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) compared to those with a reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) Heart and Vessels. 2017;33(4):403–412. doi: 10.1007/s00380-017-1073-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xiong Q., Lau Y. C., Senoo K., Lane D. A., Hong K., Lip G. Y. H. Non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulants (NOACs) in patients with concomitant atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a systemic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2015;17(11):1192–1200. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Odutayo A., Wong C. X., Hsiao A. J., Hopewell S., Altman D. G., Emdin C. A. Atrial fibrillation and risks of cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and death: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;354 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4482.i4482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kotecha D., Chudasama R., Lane D. A., Kirchhof P., Lip G. Y. H. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure due to reduced versus preserved ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of death and adverse outcomes. International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;203:660–666. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotecha D., Holmes J., Krum H., et al. Efficacy of β blockers in patients with heart failure plus atrial fibrillation: an individual-patient data meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2014;384(9961):2235–2243. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruddox V., Sandven I., Munkhaugen J., Skattebu J., Edvardsen T., Otterstad J. E. Atrial fibrillation and the risk for myocardial infarction, all-cause mortality and heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology. 2017;24(14):1555–1566. doi: 10.1177/2047487317715769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emdin C. A., Wong C. X., Hsiao A. J., et al. Atrial fibrillation as risk factor for cardiovascular disease and death in women compared with men: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2016 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h7013.h7013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rienstra M., Damman K., Mulder B. A., Van Gelder I. C., McMurray J. J. V., Van Veldhuisen D. J. Beta-blockers and outcome in heart failure and atrial fibrillation. JACC: Heart Failure. 2013;1(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng M., Lu X., Huang J., Zhang J., Zhang S., Gu D. The prognostic significance of atrial fibrillation in heart failure with a preserved and reduced left ventricular function: insights from a meta-analysis. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2014;16(12):1317–1322. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cherian T. S., Shrader P., Fonarow G. C., et al. Effect of atrial fibrillation on mortality, stroke risk, and quality-of-life scores in patients with heart failure (from the outcomes Registry for better informed treatment of atrial fibrillation [ORBIT-AF]) American Journal of Cardiology. 2017;119(11):1763–1769. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.02.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goto S., Bhatt D. L., Röther J., et al. Prevalence, clinical profile, and cardiovascular outcomes of atrial fibrillation patients with atherothrombosis. American Heart Journal. 2008;156(5):855–863.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sartipy U., Dahlström U., Fu M., Lund L. H. Atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved, mid-range, and reduced ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2017;5(8):565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bassand J.-P., Accetta G., Camm A. J., et al. Two-year outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation: results from GARFIELD-AF. European Heart Journal. 2016;37(38):2882–2889. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belenkov Y., Mareev V., Ageev F., Danielyan M. First results of national Russian epidemiological study–epidemiological examination of patients with CHF in real-world data–(EPOKHA-O-CHF) Russian Heart Failure Journal (Serdechnaya Nedostatochnost’) 2004;4(3):116–121. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Belenkov Y., Fomin I., Mareev V. First results of Russian epidemiological study of chronic heart failure (EPOKHA-CHF) Russian Heart Failure Journal (Serdechnaya Nedostatochnost’) 2003;4(1):26–30. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pfeffer M. A., Claggett B., Assmann S. F., et al. Regional variation in patients and outcomes in the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist (TOPCAT) trial. Circulation. 2015;131(1):34–42. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.013255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai A. S., Lewis E. F., Li R., et al. Rationale and design of the treatment of preserved cardiac function heart failure with an aldosterone antagonist trial: a randomized, controlled study of spironolactone in patients with symptomatic heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. American Heart Journal. 2011;162(6):966–972. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsao C. W., Lyass A., Enserro D., et al. Temporal trends in the incidence of and mortality associated with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JACC: Heart Failure. 2018;6(8):678–685. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cadrin-Tourigny J., Shohoudi A., Roy D., et al. et al. Decreased mortality with beta-blockers in patients with heart failure and coexisting atrial fibrillation. JACC: Heart Failure. 2017;5(2):99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2016.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neefs J., van den Berg N. W. E., Limpens J., et al. et al. Aldosterone pathway blockade to prevent atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2017;231:155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.