Abstract

Background

The study is intended to fill the knowledge gap about the neuropsychology and neuromotor developmental outcomes, and identify the perinatal risk factors for late preterm infants (LPIs 34~36 weeks GA) born with uncomplicated vaginal birth at the age of 24 to 30 months.

Methods

The parents/guardians of 102 late preterm infants and 153 term infants, from 14 community health centers participated in this study. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (M-CHAT) questionnaire, the Chinese version of Gesell Development Diagnosis Scale (GDDS), and the Sensory Integration Schedule (SIS), a neurological examination for motor disorders (MD) were carried out. Infants screening positive to the M-CHAT were referred to specialist autism clinics.

Results

Forty-six LPIs (45.1%) scored low in GDDS. Nine LPIs (8.8%) scored positive on M-Chat. 8.8% of LPIs (9 out of 102) were diagnosed MD (p < 0.05). Compared with their full-term peers, LPIs had statistically lower scores in GDDS and the Child Sensory Integration Checklist. LPIs who had positive results on M-CHAT showed unbalanced abilities in every part of GDDS. Risk factors of twin pregnancies, pregnancy induced hypertension and premature rupture of membranes had negative correlation with GDDS (all p < 0.05). Birth weight and gestational age were positively correlated with GDDS.

Conclusions

LPIs shall be given special attention as compared to normal deliveries, as they are at increased risk of neurodevelopment impairment, despite being born with no major problems. Some perinatal factors such as twin pregnancies, and pregnancy induced hypertension etc. have negative effects on their neurodevelopment. Regular neurodevelopmental follow- up and early intervention can benefit their long term outcomes.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12883-019-1336-0) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Late preterm infants, Motor disorders, Autism spectrum disorders

Background

Over the past 2 decades, incidence of late preterm infants (LPIs), defined as those born between 34 + 0 and 36 + 6 weeks of gestation, have become more prevalent [1]. According to the recent literature, LPIs account for approximately 84% of preterm births [2]. A survey of 80 hospitals in China in 2005 showed that 62.6% of preterm infants hospitalized in neonatal units were LPIs [3]. Social concerns have long focused on neurodevelopment of extremely preterm and extremely low birth-weight infants but LPIs are left unfocused. Many neuropsychological and behavior problems have been reported with these children such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), anxiety, and depression [4–6], however neurodevelopment of LPIs has attracted less attention. LPIs, unlike extremely preterm infants, are usually assumed to grow healthily like normal full term infants, and the follow up checkups are focused only on the physical milestones hence the psychological and behavioral development is overlooked. In recent years, studies have looked into development of recognition, social development, emotional integrity, and behaviors etc. but systematical studies are not quantitative [7]. Findings with LPIs’ neurodevelopmental outcomes are mixed. Some researchers suggested that there is no consistent significant difference between late-preterm and full-term children from ages 4 to 15 years [8]. Other studies found that late preterm birth may be a risk factor for neurodevelopmental disorders, especially at entering school age [9–12].

The aim of this study is to explore the outcomes of neuro-motor and psycho-behavior development among LPIs aged 24~30 months. We hypothesize that, there would be significantly higher rate of motor disorders, positive M-CHAT screens and inferior cognition, among LPIs than that of full term infants.

Methods

Participants

There are six districts within Xi’an city of Shaanxi province, China. Two of which were randomly selected for this study comprising of 14 community health service centers. The ethics committee of Xi’an Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital approved the study and the statement of informed consent. According to the demographic data, 158 LPIs were eligible for inclusion (all of the children born between 34+ 0 and 36+ 6 weeks of gestation during Oct.1st, 2011 to Sep.30th, 2013). Out of whom, 30 LPIs’ mothers declined to participate in the study and 26 LPIs were unable to be contacted. So, only 102 parents/guardians of LPIs were interviewed on site with informed consent. One hundred fifty-three term infants (defined as 37–42 weeks’ gestational age and of birth weight between 2.5–4 kg) were randomly recruited as the control group during the same period and from the same geographical region.

Assessment

Questionnaires regarding information about perinatal factors, and social, educational and economic states were completed by the participants’ mothers. Developmental assessment was performed by pediatric neurologists. At the time of the assessment the examiners were unaware of the fact about which of the children were born preterm. The source and references of the questionnaire are provided as an Additional file 1.

Chinese version of Gesell development diagnosis scale (GDDS)

There are five domains in Chinese version of the Gesell Development Diagnosis Scale (GDDS) [13] including domains of adaptability, gross motor, fine motor, language and social-emotional responses. The development quotient (DQ) of each domain were calculated for each participant. According to the full-scale DQ, the development of infants was classified as follow: normal (DQ ≥ 85), deficient (DQ < 75) and borderline (75 ≤ ~ < 85). DQ in any single domain falling below 75 was also considered as deficient within this field.

Modified checklist for autism (M-CHAT)

The Modified Checklist for Autism (M-CHAT) is a 23-item parent questionnaire for early identification of behaviors associated with autistic children aged 18–30 months [14]. Infants who fail 2 or more items of 2,7,9,13,14,15, or ≥ 3 items overall, are screened positive for risk of ASD or other developmental disorders. Infants positive on the screen had a follow-up check, and were assessed by a developmental pediatrician for a clinical diagnosis of autism.

The sensory integration schedule (SIS)

This tool uses parental observations to measure and assess children’s sensory symptoms from 0 to 12 years of age. It was revised by Dr. Zheng Xin-Xiong in Taiwan in 1985 according to the Sensory Integration Theory by Ayres, an American psychologist, but allowing for the Chinese cultural background, and is now used in China [15, 16]. It has seven sections comprising of 64 items. Raw scores are converted into standardized T-scores, which can then be used to classify the sensory integration ability as normal (T score equals 50 ± 5) and abnormal (T score < 45). In this study, only four sections were examined including vestibular balance, Cranial nerves suppression, tactile defunctness and proprioception, as these are the only sections pertinent to infants aged 24–30 months.

Motor delay and cerebral palsy

Infants in the study underwent a neurological examination, with cerebral palsy being diagnosed according to standard criteria [17]. Motor developmental age falling behind 3 months of the corresponding milestone or a DQ of gross motor in GDDS of < 75 can be confirmed as motor delay. Both motor delay and cerebral palsy are classified as motor disorders.

Statistical analyses

Statistical data was processed using the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 18.0 for Windows. The descriptive data were presented by ±SD. The rate of screening positive was compared between two groups using Chi-Square tests and Fisher’s exact probability. A t-test for two independent samples was used to compare the means of the groups. The association of multiple factors including birth weight, gestational age and risk factors of perinatal period to GDDS and SIS was analyzed by Person’s correlation analysis.

Results

The feature of the study population

Table 1 outlines the characteristic of the two groups. There was no significant difference between two groups regarding gender, birth weight (BW), delivery mode, and maternal education

Table 1.

The characteristic features of the study population

| Group1 | Group2 | × 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 102 | N = 153 | |||

| Male, n (%) | 68(66.7) | 94(61.4) | 0.075 | 0.784 |

| GA(weeks) -mean (SD) | 35.5 (1.02) | 39.6(1.13) | − 22.76a | < 0.001 |

| BW(gram) -mean (SD) | 2796 (4820) | 3465(415) | −0.996 a | 0.321 |

| Deliver mode, n (%) | 0.075 | 0.784 | ||

| Natural labor | 35(34.3) | 56(36.6) | ||

| Caesarean section | 67(65.7) | 97(63.4) | ||

| Perinatal risk factors, n (%) | 65(63.7) | 0 (0) | < 0.001b | |

| Maternal education, n (%) | < 0.001 | 0.986 | ||

| Completion of University | 59(57.8) | 88(57.5) | ||

| Completion of Secondary school | 43(42.2) | 65(42.5) |

at-test, b Fisher’s exact probability test. Significance = < 0.05

Developmental outcomes in late-preterm and full-term children at ages 24 to 30 months

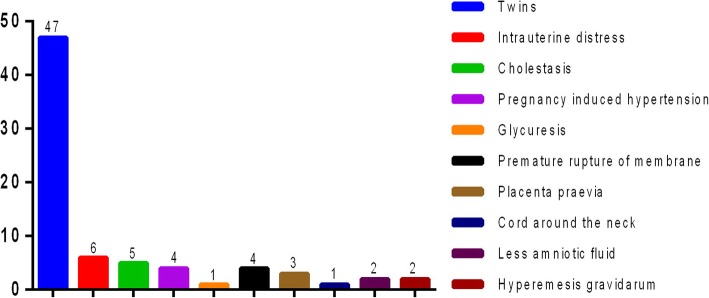

Comparisons of the neurodevelopment outcomes are summarized in Table 2. Two LPIs were found with CP and seven had motor delay compared to one motor delay in group 2. The rates of MD, true positive screen of M-chat, abnormity in GDDS and SIS were statistically higher than those of group 2. Furthermore, seven twins among the LPIs (7/9) were found to have positive screen of M-chat. Figure 1 shows the perinatal risk factors for developmental abnormality in LPIs.

Table 2.

Rate of developmental abnormalities in the two groups

| Group1 N (%) 102 | Group2 N (%) 153 | x2 value | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | 9 (8.8) | 1 (0.65) | < 0.001a | |

| Rate of positive screen of M-chat | 9(8.8) | 0 (0) | 0.029 a | |

| Abnormity in GDDS | 46 (45.1) | 3 (5.8) | 24.557 | < 0.001 |

| Abnormity in CSIC | 30 (29.4) | 5 (3.3) | 7.686 | 0.006 |

aFisher’s exact probability test

Fig. 1.

Distribution of perinatal risk factors in group 1

Comparison of GDDS and the child sensory integration checklist between the two groups

Tables 3 and 4 outline the scores of GDDS and the Child Sensory Integration of the two groups. LPIs presented inferior abilities in all the regions of GDDS and much lower level in the Child Sensory Integration compared with group 2 (p < 0.05). Although the difference between the two groups in the category of proprioception was not statistically significant (p > 0.05), but LPIs still showed a low mean score in this category.

Table 3.

Comparison of scores of GDDS between the two groups (Mean score and SD)

| Group1 n = 102 | Group2 n = 153 | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | 76.91(14.42) | 88.12(11.43) | −4.874 | < 0.001 |

| Gross motor | 84.57(13.33) | 90.59(9.85) | −2.881 | 0.005 |

| Fine motor | 79.23(11.90) | 88.77(11.75) | −4.727 | < 0.001 |

| Language | 78.72(16.43) | 86.83(10.41) | −3.241 | 0.001 |

| personal-social | 78.91(14.34) | 90.15(10.97) | −4.946 | < 0.001 |

| Vestibular balance | 52.83(12.00) | 61.12(9.28) | −4.356 | < 0.001 |

| Inhibition troubles of nervous system | 51.14(11.54) | 57.23(8.42) | −3.375 | 0.001 |

| tactile defunctness | 54.71(7.75) | 58.75(9.71) | − 2.806 | 0.006 |

| proprioception | 56.06(9.28) | 58.96(7.67) | −1.942 | 0.054 |

Table 4.

Comparison of scores of SIS between the two groups (Mean score and SD)

| Group1 n = 102 | Group2 n = 153 | T | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vestibular balance | 52.83(12.00) | 61.12(9.28) | −4.356 | < 0.001 |

| Inhibition troubles of nervous system | 51.14(11.54) | 57.23(8.42) | −3.375 | 0.001 |

| tactile defunctness | 54.71(7.75) | 58.75(9.71) | −2.806 | 0.006 |

| proprioception | 56.06(9.28) | 58.96(7.67) | −1.942 | 0.054 |

Correlation of gestational age (GA), birth weight (BW) and the perinatal factors with various functional regions of GDDS and the child sensory integration checklist

The results of Person’s correlation analysis indicated that among perinatal risk factors, twins are associated with a statistically significant reduction in vestibular balance scores of SIS (r = − 0.203, p = 0.041). Pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH) is associated with adaptability and language problems (r = − 0.234, − 0.198, p = 0.018, 0.046), premature rupture of membrane (PROM) is associated with gross motor, fine motor and social-emotional problems according to GDDS (r = − 0.265, − 0.209, − 0.231, p = 0.007, 0.035, 0.020). With the increased BW and GA, scores in all the regions of GDDS, vestibular balance, Physiological inhibition of cranial nerve and SIS ascend accordingly. (r = 0.436,0.382,0.466, 0.327, 0.443, 0.249, 0.215; 0.393, 0.293, 0.406, 0.219, 0.369, 0.234, 0.260. p = < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001, 0.002, 0.008; < 0.001, < 0.001, < 0.001,0.006, < 0.001, 0.004, 0.001). The same thing can also be found between GA and tactile defunctness (r = 0.204, p = 0.010).

DQ in various functional regions of GDDS for LPIs with positive screen of M-chat

LPIs that screened positive for ASD showed a disequilibrium trend in various regions of GDDS. They showed much lower DQ in adaptability, language and personal-social categories (Table 5).

Table 5.

Distribution of scores in GDDS of LPIs with positive M-chat screening

| Item | Mean Score and SD | The minimum and the peak | Distribution of scores | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| > 75 | 75–55 | 54–40 | < 40 | |||

| Adaptability | 56.89(9.71) | [39, 70] | 0 | 2 | 6 | 1 |

| Gross Motor | 76.11(13.88) | [44, 88] | 8 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Fine Motor | 67.11(9.68) | [50, 84] | 3 | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Language | 56.44(10.39) | [37, 67] | 0 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| personal-social | 62.00(9.42) | [47, 79] | 1 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

Discussion

In our study, LPIs presented negative neuropsychologic and behavior results: 8.8% of LPIs screened true positive on M-chat for ASD at 2 years, which was similar to the 4% ~ 8% for very preterm and extremely preterm infants observed in previous studies [18–20]. Data from the 2010 American CDC surveillance year revealed the overall prevalence of ASD reaching 14.7/1000 (one in 68 children aged 8 years) [21], however risk of ASD for LPIs was 2 to 4 times greater than that for term infants. According to the reports by Guy et al. and Hwang et al., about 2.4 and 1.3%, LPIs screened true positive for ASD respectively [22, 23]. As there has been little previous investigation about the development of ASD in the LPIs population, the cause of the variation seen in positive ASD screening rates in LPIs remains unclear. The investigation methods, sample size and age of children may be factors affecting the different rates, however most importantly, many of these studies suggest a higher risk of ASD in LPIs. The etiology of ASD in late preterm twins is still poorly understood. One reason for this may be aberrant brain development playing a part in the development of ASD [18], another reason may be genetic and shared environmental factors contributing to the increased risk of ASD for twin LPIs [24–26]. Therefore, twin LPIs in particular, should receive more attention on their neuropsychological development. LPIs with positive ASD, showed unevenly distributed abilities in GDDS. Impairments in cognition greatly influence a child’s future social life and even the academic performance [27], therefore early screening for ASD and early intervention are important for these children.

Sensory Integration Dysfunction (SID) includes difficulties in receiving and processing stimuli from different senses [28]. It has been confirmed that SID is associated with white matter damage, adverse circumstance stimulation in NICU including repeated pain stimuli, and separation from parents [29]. In this study however, LPIs had none of the above factors, but they still showed problems related to vestibular balance, nervous system inhibition, and tactile defunctness, suggesting sensory modulation defect. Mitchell et al., reported the sensory modulation defect as being more common in preterm infants under 3 years [30] and our results suggested a similar conclusion, implying that LPIs may have behavioral problems in school age needing additional academic assistance [31, 32]. The study by Olean et al., showed that 82% (59/72) of preterm infants with gestational age of < 30 weeks had abnormal sensory reactivity [33]; which our study showed to be in 29.4% of LPIs, therefore the sensory integration development of LPIs should not be neglected.

Recognition deficit is common in preterm infants and show significant correlation with low gestation and low birth weight. A study shows the “dose-response” effect of GA on later development [34]. Similar results can also be found in our study: scores in each region of GDDS were statistically lower than those of term infants. Abnormal motor development was also more common in Group 1. All of these indicate high risk of cognitive and motor developmental problems for LPIs. LPIs seemed to have a diagnosis of a development delay in the first 3 years of life with poor cognitive performance [35, 36]. Although most LPIs in this study were born without complications and had no history of neonatal diseases or experience of complex medical intervention, and seemed to show no major problems in the post-neonatal period, even then the development of recognition, motor, and social-emotion was not good as compared to term infants. A study conducted by Ozkan et al. has reported that socioeconomic risk factors were important biological risk factors in the development of children aged 3 months to 5 years [37]. Multiple factors i.e. twin pregnancy, GA, BW, PIH and PROM were found to be correlated to LPIs’ cognitive development and sensory modulation in this study. We can therefore safely conclude that an immature brain, in addition to perinatal risk factors, likely plays a crucial role in their inferior neurodevelopment. Thus LPIs, unlike term infants, shall be given more attention as preterm infants and shall be assessed and monitored for neurodevelopment impairment.

Conclusion

In accordance with the results of the study, we have arrived at following conclusions: firstly, LPIs born with no major problems can still have increased risk of ASD, MD, SID and recognition defects. Secondly, LPIs (especially twins) may benefit from regular follow up during the first 3 years of life, for early detection of possible disorders and timely intervention could help to avoid poorer long-term outcomes. Thirdly, conservative management styles hoping for normal development can be detrimental for LPIs, therefore it is important to educate parents regarding the normal development of a child. Fourthly, some developmental domains and perinatal risk factors were identified in the study to have no significant difference; so, a longer period of follow up and a larger sample size may reveal more definitive outcomes. And finally, this study will contribute to fill the knowledge gap about the neurological and behavioral out comes of the late preterm infants, who were previously considered as normal deliveries and were not given special attention as preterm infants. So, this study clearly differentiates and emphasizes the importance of understanding about LPIs to be considered for special attention like preterm infants.

Additional file

Questionnaire sources. (DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgements

We thank the staff of Lianhu and Beilin District Maternal and Child Health Station. They help us collect important individual information about study subjects and introduce us to the staff of community health service centers. We also address our sincere thanks to the staff of 14 community health service centers. They help us call up infants to participate our investigation and assist our work.

Abbreviations

- ADHD

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

- ASD

Autism spectrum disorders

- BW

Birth weight

- DQ

Development quotient

- GA

Gestational age

- GDDS

Gesell Development Diagnosis Scale

- LPIs

Late preterm infants

- M-CHAT

The modified checklist for autism in toddlers

- MD

Motor disorders

- SID

Sensory Integration Dysfunction

- SIS

Sensory Integration Schedule

Authors’ contributions

JY and BHS designed the study and did analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript, MCH, CHC, and WYY did conception and acquisition of data and analysis of data. All of the authors have given approval of the final version of the manuscript to be published, and agreed to be accountable.

Funding

This work was supported by the Project of Xi’an Health and Family Planning Commission, grant number: 2013039. The funding body has no participation or influence in design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The relevant data and materials are stored and saved with the author and the Hospital medical affairs department and is available on demand. All questionnaires used in this study are referenced both in manuscript as well as in the supplementary files.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Medical and Biological Research Ethics Review Committee of Xi’an Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital approved the study and the statement of informed consent beforehand, reference number: 2011012. All the participants i.e. the parents/guardians of the children consented willingly to participate by signing the written consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

You Jia and Bilal Haider Shamsi contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Jia You, Email: stonebroken2008@126.com.

Bilal Haider Shamsi, Email: drhydi@outlook.com.

Mei-chen Hao, Email: 1577502161@qq.com.

Chun-Hong Cao, Email: caochunhong2008@163.com.

Wu-Yue Yang, Email: ywy19860509@126.com.

References

- 1.Jennifer E, McGowan RN, Fiona A, et al. Early childhood development of late-preterm infants: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2011;127:1111–1124. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giovanni M, Chiara N. The case of late preterm birth: sliding forwards the critical window for cognitive outcome risk. Transl Pediatr. 2015;4:214–218. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2224-4336.2015.06.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong TAO, Xiao-yu ZHOU. Clinical problems in late preterm infants. J Perinat Med. 2013;16(3):189–191. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hack M, Taylor HG, Schluchter M, et al. Behavioral outcomes of extremely low birth weight children at age 8 years. Behav Pediatr. 2009;30:122–130. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31819e6a16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson PJ, De Luca CR, Hutchinson E, et al. Attention problems in a representative sample of extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2011;36:57–73. doi: 10.1080/87565641.2011.540538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott MN, Taylor HG, Fristad MA, et al. Behavior disorders in extremely preterm/extremely low birth weight children in kindergarten. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33:202–213. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3182475287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tao H, Zhou XY. Clinic problems in late preterm infants. Chin J Perinat Med. 2013;16(3):189–191. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurka MJ, Lo J, et al. Long-term cognition, achievement, socioemotional, and behavioral development of healthy late-preterm infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164:525–532. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson S, Matthews R, Draper ES, et al. Early emergence of delayed social competence in infants born late and moderately preterm. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36:690–699. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nepomnyaschy L, Hegyi T, Ostfeld BM, et al. Developmental outcomes of late-preterm infants at 2 and 4 years. Matern Child Health. 2012;16:1612–1624. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0853-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caravale B, Mirante N, Vagnoni C, et al. Change in cognitive abilities over time during preschool age in low risk preterm children. Early Hum Dev. 2012;88:363–367. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinonen K, Eriksson JG, Lahti J, et al. Late preterm birth and neurocognitive performance in late adulthood: a birth cohort study. Pediatrics. 2015;135:818–825. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang YF. Rating Scales For Children’s Developmental Behavior and Mental Health [M] Version 1, Beijing: People's Medical Publishing House, 2016:71.

- 14.Dumont-Mathieu T, Fein D. Screening for autism in young children: the modified checklist for autism in toddlers (M-CHAT) and other measures. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2005;11(3):253–262. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng X. How to help children with learning difficulties [M] Version2. Beijing: Jiuzhou Publishing House; 2004. pp. 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mailloux Zoe, Miller-Kuhaneck Heather. Evolution of a Theory: How Measurement Has Shaped Ayres Sensory Integration®. American Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2014;68(5):495. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2014.013656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richards CL, Malouin F. Cerebral palsy: definition, assessment and rehabilitation. Hand book Clin Neurol. 2013;111:183–195. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52891-9.00018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H, et al. The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2000;41:645–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2000.tb02345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson S, Hollis C, Kochhar P, et al. Autism spectrum disorders in extremely preterm children. Pediat. 2010;154:525–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Treyvaud K, Ure A, Doyle LW, et al. Psychiatric outcomes at age seven for very preterm children: rates and predictors Child Psychol. Psychiatr. 2013;54:772–779. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2010 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Prevalence of autism Spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years — autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;28:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guy A, Seaton SE, Boyle EM, et al. Infants born late/moderately preterm are at increased risk for a positive autism screen at 2 years of age. Pediat. 2015;166:269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang YS, Weng SF, Cho CY, et al. Prevalence of autism in Taiwanese children born prematurely: a nationwide population-based study. Res Dev Disabi. 2013;34:2462–2468. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2013.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hallmayer J, Cleveland S, Torres A. Genetic heritability and shared environmental factors among twin pairs with autism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1095–1102. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ronald A, Larsson H, Anckarsäter H, et al. A twin study of autism symptoms in Sweden. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sven S, Paul L, Ralf KH. The familial risk of autism. AMA. 2014;311:1770–1777. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huhtala M, Korja R, Lehtonen L, et al. Associations between parental psychological well-being and socio-emotional development in 5-year-old preterm children. Early Human Development. 2014;90:119–124. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Al-Heizan MO, AlAbdulwahab SS, Kachanathu SJ, et al. Sensory processing dysfunction among Saudi children with and without autism. PhysTherSci. 2015;27(5):1313–1316. doi: 10.1589/jpts.27.1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tinka B, Kim JO, Harrie NL, et al. Sensory modulation in preterm children: theoretical perspective and systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):1–23. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0170828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell A, Moore E, Roberts E, et al. Sensory processing disorder in children ages birth–3 years born prematurely: a systematic review[J] Am J Occup Ther. 2015;69(1):1–11. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2015.013755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Polić B, Bubić A, Meštrović J, et al. Emotional and behavioral outcomes and quality of life in school-age children born as late preterm: retrospective cohort study. Croat Med J. 2017;58(5):332–41. doi: 10.3325/cmj.2017.58.332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shah Prachi, Kaciroti Niko, Richards Blair, Oh Wonjung, Lumeng Julie C. Developmental Outcomes of Late Preterm Infants From Infancy to Kindergarten. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20153496. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chorna O, Solomon JE, Slaughter JC, Stark AR, Maitre NL. Abnormal sensory reactivity in preterm infants during the first year correlates with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years of age. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2014;99:475–479. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gwenden D, Jing C, Candace C, et al. Early developmental outcomes predicted by gestational age from 35 to 41 weeks [J] Early Hum Dev. 2016;12(103):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brogna C, Romeo DM, Cervesi C, Scrofani L, et al. Prognostic value of the qualitative assessments of general movements in late-preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 2013;89:1063–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Talge NM, Holzman C, Wang J, et al. Late-preterm birth and its association with cognitive and socioemotional outcomes at 6 years of age. Pediatrics. 2010;126:1124–1131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ozkan M, Senel S, Arslan EA, et al. The socioeconomic and biological risk factors for developmental delay in early childhood. Eur J Pediatr. 2012;171(12):1815–1821. doi: 10.1007/s00431-012-1826-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Questionnaire sources. (DOCX 14 kb)

Data Availability Statement

The relevant data and materials are stored and saved with the author and the Hospital medical affairs department and is available on demand. All questionnaires used in this study are referenced both in manuscript as well as in the supplementary files.