Abstract

• PURPOSE:

Central retinal artery occlusion (CRAO) confers a high risk of acute vascular ischemic events, including stroke and myocardial infarction (MI). Understanding the burden and risk factor profile of these ischemic events can serve as a valuable guide for ophthalmologists in the management and appropriate referral of these patients.

• DESIGN:

Retrospective cross-sectional study.

• METHODS:

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) was queried to identify all inpatient admissions with a diagnosis of CRAO in the United States between the years 2003 and 2014. The primary outcome measure was the incidence of in-hospital acute vascular ischemic events.

• RESULTS:

There were an estimated 17 117 CRAO inpatient admissions. The mean age was 68.4 ± 0.1 years and 53% of patients were female. The incidence of in-hospital stroke and acute MI were 12.9% and 3.7%. The incidence of stroke showed an increasing trend over the years, almost doubling in 2014 in comparison to 2003 (15.3% vs 7.7%). The combined risk of in-hospital stroke, transient ischemic attack, acute MI, or mortality was 19%. Female sex, hypertension, carotid artery stenosis, aortic valve disease, smoking, and alcohol dependence or abuse were positive predictors of in-hospital stroke.

• CONCLUSION:

There is a significant burden of vascular risk factors, associated with an increased risk of in-hospital stroke, acute MI, and death in CRAO patients. The risk of CRAO-associated stroke is highest in women and in those with a history of hypertension, carotid artery stenosis, aortic valve disease, smoking, or alcohol abuse.

CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION (CRAO) IS AN ophthalmic emergency and important cause of sudden-onset vision loss.1 The pathophysiology is predominantly embolic or thrombotic occlusion of the central retinal artery with resultant ischemia. As CRAO shares common risk factors with cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases,2 it is an important clinical indicator of acute vascular ischemic events, including stroke or myocardial infarction (MI).3

At present, there are no effective treatment options known to significantly improve visual outcomes in CRAO patients.4–8 Therefore, the emphasis of clinical management is on prevention of secondary vascular ischemic events. As the risk of stroke is highest in the period immediately following a CRAO,9–12 prompt clinical evaluation to identify the underlying etiology and timely institution of stroke prevention measures is warranted.13

American Academy of Ophthalmology (AAO) guidelines recommend all patients with CRAO be referred to the nearest stroke center.14 In addition, American Heart Association/American Stroke Association (AHA/ASA) guidelines recommend all patients with suspected retinal ischemia undergo immediate brain imaging.15 There is lack of consensus regarding the need for prompt neurologic and cardiovascular evaluation in CRAO patients; approximately 35% of ophthalmologists refer patients with acute CRAO to the emergency department (ED) for immediate evaluation.16 Management practices differ significantly across specialties, with 75% of neurologists pursuing a hospital-based evaluation, while 82% of retina specialists opt for an outpatient evaluation.17

Although immediate ED referral and inpatient evaluation of all CRAO patients may be the safest, most conservative approach, such evaluations may increase the costs related to more frequent hospitalizations. Risk stratification of CRAO patients for future ischemic events and efficient triaging is imperative to ensure that those at high risk undergo emergent evaluation. Such an approach would require clinicians to better understand the risk factor profile and predictors of stroke in CRAO patients.

We conducted a nationwide study on CRAO patients spanning more than a decade (2003–2014) to investigate the following: (1) vascular risk factors and systemic conditions associated with CRAO; (2) the incidence of in-hospital stroke, myocardial infarction, and mortality; (3) temporal trends in the incidence of CRAO-related acute ischemic events; (4) predictors of in-hospital stroke; (5) burden and economic costs associated with inpatient CRAO admissions.

METHODS

• DATA SOURCE AND STUDY POPULATION:

The Nation-wide Inpatient Sample (NIS) was queried for the years 2003–2014, to identify all patients admitted with a diagnosis of CRAO. The NIS is the largest all-payer inpatient database in the United States and is part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The sampling strategy of the NIS changed in 2012, prior to which the database comprised a 20% stratified systematic sample of all US community hospitals, with all discharges retained from those hospitals. In 2012, in an attempt to improve national estimates, the database was redesigned to include a 20% stratified sample of discharges from all hospitals in the HCUP. In 2014, the NIS contained data for approximately 8 million hospital discharges from 44 participating states, representing 98% of the US population. Sampling strata used by the NIS is based on hospital characteristics (eg, urban or rural location, teaching status, and hospital bed size). The data can be weighted according to the NIS sampling frame to generate national estimates.18 Analyses discussed and results represent weighted national estimates. The institutional review board at West Virginia University granted this study exempt status; all data are publicly available and do not include patient identifiers. This study was conducted in adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki and US federal and state laws.

Patients with a diagnosis of CRAO, associated vascular risk factors, comorbidities, and procedures performed during hospitalization were identified using relevant International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes. Charges reported in this study represent the amount that hospitals billed for services during admission. These charges do not reflect how much hospital services actually cost, the specific amounts that hospitals received in payment, or the costs incurred to the patients. Median charge per hospitalization and total charges per year were calculated and inflation-adjusted using the Consumer Price Index for Hospital Services from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics.19

• STATISTICAL ANALYSIS:

Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies with percentages for categorical variables, and mean with standard error of mean (SEM) for continuous variables. Comparisons between groups were made using the independent samples t test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical variables. Univariate and multiple logistic regression models were used to examine the association between vascular risk factors and stroke. The estimated odds ratio (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) from the regression models were presented. All P values were nominal and a value of less than .05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

RESULTS

• DEMOGRAPHICS AND BASELINE CHARACTERISTICS:

The baseline and demographic characteristics are described in Table 1. From 2003 to 2014, there were an estimated 17 117 CRAO admissions. The number of admissions showed an increasing trend over the years, nearly doubling between 2003 and 2014. The mean age was 68.4 ± 0.1 years and most patients were ≥70 years old. Fifty-three percent of patients were female and the majority were white (63.2%), followed by African American (12.1%) and Hispanic (5.7%). There was disparity in the geographic distributions of CRAO admissions, being highest in the South (31.9%). Most patients were publicly insured through Medicare or Medicaid (70%), followed by private insurance (23.1%). The majority of admissions were in urban teaching hospitals (64.2%) and hospitals with a large bed size (69%). The most frequent admission source was the ED (44.4%).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and Baseline Characteristics of Study Patients

| Demographic Characteristics | Results (N = 17 117 Patients) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SEM, years | 68.24 ± 0.12 |

| Age, years | |

| <50 | 1950 (11.4) |

| 50–59 | 2310 (13.5) |

| 60–69 | 3834 (22.4) |

| 70–79 | 4582 (26.8) |

| ≥80 | 4441 (25.9) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 9065 (53) |

| Male | 8043 (47) |

| Race | |

| White | 10 825 (63.2) |

| Black | 2068 (12.1) |

| Hispanic | 969 (5.7) |

| Others | 721 (4.2) |

| Unknown | 2535 (14.8) |

| Primary expected payer | |

| Medicare and Medicaid | 11 987 (70.0) |

| Private insurance | 3947 (23.1) |

| Self-pay | 753 (4.4) |

| No charge | 68 (0.4) |

| Others | 327 (1.9) |

| Region | |

| Northwest | 4173 (24.4) |

| Midwest | 4574 (26.7) |

| South | 5462 (31.9) |

| West | 2908 (17.0) |

| Admission source | |

| Emergency department | 7594 (44.4) |

| Another hospital or health care facility | 1558 (9.1) |

| Non–health care facility | 4187 (24.5) |

| Court or law enforcement | 124 (0.7) |

| Others | 3652 (21.3) |

| Disposition of patient | |

| Home or self-care | 11 831 (69.1) |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 608 (3.6) |

| Skilled nursing or intermediate care facility | 2216 (12.9) |

| Home health care | 2293 (13.4) |

| Against medical advice | 123 (0.7) |

| Bed size of hospital | |

| Small | 1740 (10.2) |

| Medium | 3522 (20.6) |

| Large | 11 807 (69.0) |

| Location and teaching status of hospital | |

| Rural | 1225 (7.2) |

| Urban nonteaching | 4862 (28.4) |

| Urban teaching | 10 983 (64.2) |

| Length of hospital stay, days | |

| Median | 3.0 |

| Mean ± SEM | 4.98 ± 0.06 |

SEM = standard error of mean.

Data are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

• VASCULAR RISK FACTORS AND ASSOCIATED SYSTEMIC DISEASES:

The most common vascular risk factor was hypertension (72.1%), followed by dyslipidemia (50.9%), ischemic heart disease (IHD; 35.2%), diabetes mellitus (DM; 26.0%), carotid artery stenosis (22.1%), smoking (16.4%), atrial fibrillation or flutter (15.7%), congestive heart failure (14.4%), chronic kidney disease (14.9%), left-sided valvular heart disease (12.2%), history of prior cerebrovascular accident or transient ischemic attack (TIA) (8.9%), obesity (8.2%), peripheral vascular disease (7.3%), and end-stage renal disease (3.6%). Malignant hypertension was present in 2.3%; 1.5% of CRAO patients had angina pectoris. Alcohol dependence or abuse was diagnosed in 3.1% of patients. Approximately 2% of patients had a diagnosis of systemic hypercoagulable state and 1.3% had connective tissue diseases. Systemic vasculitides were present in 4.4% of patients, the most common being giant cell arteritis (GCA). Vascular risk factors and associated systemic diseases are summarized in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Vascular Risk Factors and Systemic Diseases in Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

| Vascular Risk Factors and Systemic Diseases | N (%) (N = 17 117 Patients) |

|---|---|

| Hypertension | 12 337 (72.1) |

| Malignant hypertension | 398 (2.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 4447 (26.0) |

| Dyslipidemia | 8712 (50.9) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 6028 (35.2) |

| Angina pectoris | 253 (1.5) |

| Congestive heart failure | 2473 (14.4) |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 2689 (15.7) |

| Carotid artery stenosis or occlusion | 3776 (22.1) |

| Left-sided valvular heart disease | 2088 (12.2) |

| Mitral valve disease | 829 (4.8) |

| Aortic valve disease | 914 (5.3) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1250 (7.3) |

| Smoking | 2800 (16.4) |

| Alcohol dependence or abuse | 531 (3.1) |

| Obesity | 1405 (8.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2557 (14.9) |

| End-stage renal disease | 614 (3.6) |

| Hypercoagulable state | 323 (1.9) |

| Primary hypercoagulable state | 289 (1.7) |

| Secondary hypercoagulable state | 34 (0.2) |

| Sickle cell disease or trait | 64 (0.4) |

| Systemic connective tissue disorders | 215 (1.3) |

| Giant cell arteritis | 676 (3.9) |

| Systemic vasculitis | 755 (4.4) |

| Prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack | 1528 (8.9) |

• INCIDENCE OF IN-HOSPITAL STROKE, MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION, AND MORTALITY:

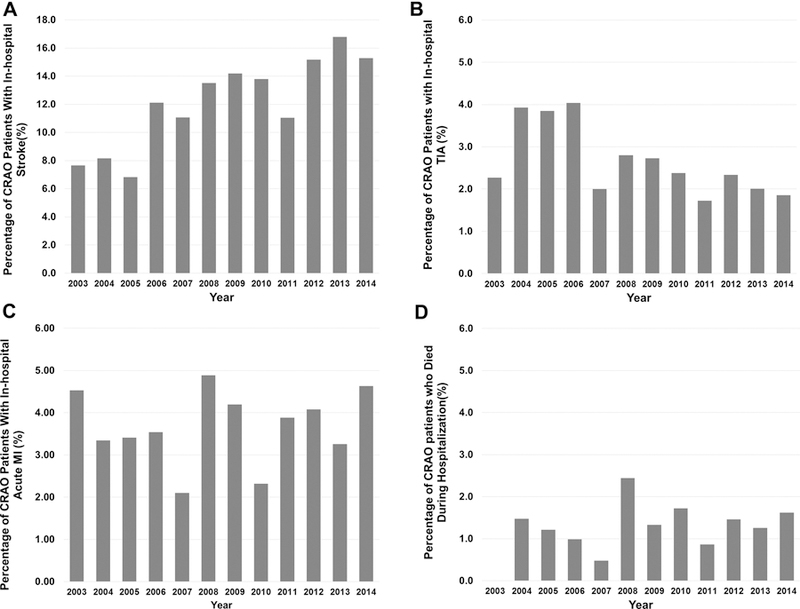

The risk of in-hospital stroke was 12.9%; the vast majority were ischemic in nature. The risk of developing a TIA was much lower (2.5%). During hospital admission, 3.7% of patients developed acute MI and 2.5% underwent a cardiac intervention. Carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and stenting were the most common procedures performed (6.8%). Systemic fibrinolytic therapy was administered in 2.9% of patients. In-hospital mortality was 1.3%. The aggregate risk of in-hospital stroke, TIA, MI, or mortality was 19% (Table 3). Temporal trends of CRAO-associated acute ischemic events are presented in Figure 1 (A-D). The incidence of stroke shows an increasing trend through the years, almost doubling in 2014 in comparison to 2003 (15.3% vs 7.7%).

TABLE 3.

Incidence of In-Hospital Stroke, Acute Myocardial Infarction, or Death in Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

| N (%) (N = 17 117 Patients) |

|

|---|---|

| Stroke | 2202 (12.9) |

| Ischemic stroke | 2080 (12.2) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 142 (0.8) |

| TIA | 428 (2.5) |

| Carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stent | 1157 (6.8) |

| Acute MI | 639 (3.7) |

| Cardiac interventiona | 430 (2.5) |

| Systemic fibrinolytic therapy | 494 (2.9) |

| Died during hospitalization | 222 (1.3) |

| Combined risk of stroke, TIA, MI, or death | 3248 (19.0) |

MI = myocardial infarction; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

Percutaneous coronary intervention; coronary artery bypass grafting.

FIGURE 1.

Temporal trends of in-hospital acute ischemic events in central retinal artery occlusion in the United States population: A) Acute stroke; B) Transient ischemic attack; C) Acute myocardial infarction; D) Died during hospitalization.

• PREDICTORS OF STROKE IN CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION:

Variable selection for the multiple logistic regression model was based on results of the univariate analysis (Table 4) and clinical judgment of the study investigators. Multiple logistic regression analysis detected female sex (OR = 1.19, 95% CI = 1.08–1.30, P = .0003), hypertension (OR = 1.22, 95% CI = 1.10–1.36, P = .0003), carotid artery stenosis (OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.73–2.11, P < .0001), aortic valve disease (OR = 1.65, 95% CI = 1.38–1.97, P < .0001), smoking (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.16–1.47, P < .0001), and alcohol dependence or abuse (OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.09–1.75, P = .006) as positive predictors of stroke (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Predictors of Stroke in Patients With Central Retinal Artery Occlusion Using Univariate and Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI (Lower-Upper) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate Regression Analysis | |||

| Age ≥75 years | 0.91 | 0.83–0.99 | .05 |

| Female | 1.08 | 0.99–1.18 | .09 |

| Prior history of stroke or TIA | 0.34 | 0.22–0.53 | <.0001 |

| Hypertension | 1.28 | 1.15–1.42 | <.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.89 | 0.80–0.99 | .03 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.11 | 1.02–1.22 | .02 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 1.02 | 0.93–1.12 | .65 |

| Congestive heart failure | 1.01 | 0.89–1.14 | .92 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 1.03 | 0.92–1.17 | .59 |

| Carotid artery stenosis or occlusion | 1.96 | 1.78–2.16 | <.0001 |

| Left-sided valvular heart disease | 1.19 | 1.04–1.35 | .01 |

| Mitral valve disease | 1.00 | 0.81–1.23 | .99 |

| Aortic valve disease | 1.51 | 1.26–1.79 | <.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.18 | 0.89–1.56 | .24 |

| Smoking | 1.42 | 1.27–1.58 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol dependence or abuse | 1.50 | 1.20–1.88 | .0004 |

| Obesity | 1.10 | 0.94–1.29 | .22 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0.92 | 0.81–1.05 | .19 |

| End-stage renal disease | 1.16 | 0.92–1.46 | .21 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 1.26 | 0.93–1.71 | .14 |

| Multiple Logistic Regression Analysis | |||

| Age ≥75 years | 0.90 | 0.82–0.99 | .04 |

| Female | 1.19 | 1.08–1.30 | .0003 |

| Hypertension | 1.22 | 1.10–1.36 | .0003 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.99 | 0.91–1.09 | .94 |

| Carotid artery stenosis or occlusion | 1.91 | 1.73–2.11 | <.0001 |

| Aortic valve disease | 1.65 | 1.38–1.97 | <.0001 |

| Smoking | 1.30 | 1.16–1.47 | <.0001 |

| Alcohol dependence or abuse | 1.39 | 1.09–1.75 | .006 |

CI = confidence interval; TIA = transient ischemic attack.

• RESOURCE UTILIZATION:

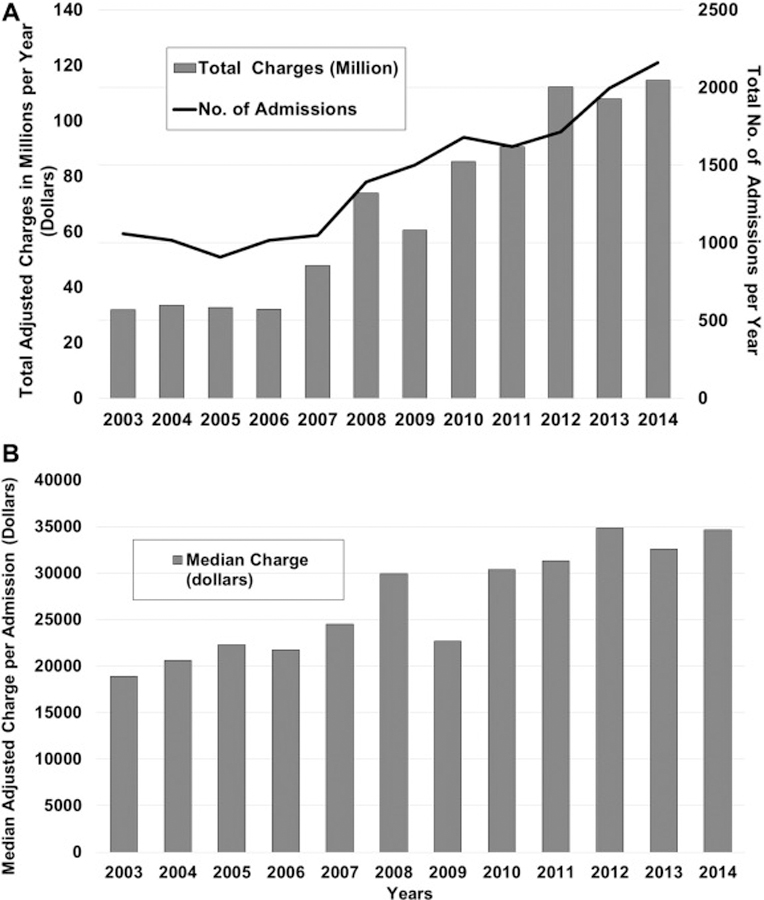

The median length of hospital stay was 3.0 days (mean ± SEM, 4.98 ± 0.06 days). In 2014, median inflation-adjusted charge per CRAO hospitalization was $34 668. Cumulative inflation-adjusted charges of all such hospitalizations totaled approximately $115 million. Median charge per admission and the cumulative charge per year are summarized in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Economic burden associated with central retinal artery occlusion hospitalizations in the United States: A) Total number of admissions and inflation-adjusted charges per year; B) Mean inflation-adjusted charge per hospital admission.

DISCUSSION

CENTRAL RETINAL ARTERY OCCLUSION CONFERS A HIGH risk of acute vascular ischemic events, including stroke and myocardial infarction. At present, considerable variability exists among the reported rates of these ischemic events. This is likely owing to differences in study methodology, with most studies either conducted at single centers or in populations that are demographically different. Therefore, they fail to provide representative data of the US population at large. This study investigates vascular risk factors and the burden of acute vascular ischemic events in the period immediately following a CRAO, while simultaneously identifying predictors of stroke in this patient population.

Consistent with prior studies, hypertension was the most common vascular risk factor associated with CRAO.9,10 Diabetes-associated macrovascular changes, including carotid artery atherosclerosis, are important sources of emboli, whereas microvascular changes such as retinal arteriolar narrowing increase the risk of vascular occlusion.20 In this study, 26% of CRAO patients had DM, consistent with prior reports.2,9,21–23 The percentage of patients with dyslipidemia and IHD in our study population was, respectively, 50.9% and 35.2%, similar to studies conducted in the United States, but substantially higher than reported in a Korean population.21

The carotid artery and heart are the most common sources of emboli in CRAO.2 Atherosclerotic plaques of the carotid artery can release emboli in the bloodstream that can become lodged in the central retinal artery, resulting in retinal ischemia and subsequent vision loss.20 Ischemia is further exacerbated by poor perfusion caused by stenosis.1 Carotid artery stenosis was present in 22.1% of patients, with most prior studies reporting rates between 25% and 40%.2,10,20,24 Cardiac sources of emboli are commonly attributable to underlying atrial fibrillation or valvular heart disease. Atrial fibrillation increases the risk of developing retinal artery occlusion (RAO)25; however, the reported prevalence is variable.10,26 This variability results from differences in detection rates, with longer monitoring strategies associated with higher detection rates.26,27 Since all patients in this study were hospitalized and likely underwent thorough cardiac evaluation, we expect a good atrial fibrillation detection rate in our study. We identified left-sided valvular heart disease in 12.2% of patients (aortic valve disease was most common), similar to previous reports.2,10,28,29 There was a much higher prevalence of carotid artery disease than atrial fibrillation or cardiac valvular disease. This is in contrast to cerebrovascular ischemic diseases, where atrial fibrillation is more common.10,30,31 This distinction is noteworthy from a clinical standpoint, because despite sharing a common pathophysiology, CRAO and ischemic stroke have a discordant risk factor profile.

This study found both smoking and alcohol dependence or abuse to be independent predictors of stroke. These findings emphasize the importance of lifestyle modification strategies as means of secondary stroke prevention in CRAO patients. GCA has been reported in 3.8% of CRAO patients, similar to what we observed.32 In patients ≥65 years, GCA was present in 5.3% of patients and should be ruled out in all elderly CRAO patients.

The association between CRAO and stroke is well established.3,10,21,33–35 Reported incidence of stroke was 27.8% in the Taiwanese population within 3 years34 and 15% in a Korean population.35 Risk is usually highest in the period immediately following a CRAO,10,12,34,36,37 especially in the first 2 weeks.36 This narrow window for stroke prevention necessitates urgent identification of risk factors so that preventive measures may be instituted in a timely manner. While there is general agreement on the increased risk of stroke in CRAO, uncertainty remains regarding the magnitude of this risk. Some groups report this risk as 6%−7%,10,20 while others report it as 37.3%.24 In this study, the risk of in-hospital stroke and TIA were 12.9% and 2.5%. The discrepancy in stroke incidence may arise from variable study designs and criteria for stroke diagnosis. Some studies subjected all CRAO patients to diagnostic brain imaging, likely increasing the odds of detecting silent brain infarcts; others established diagnosis on the basis of symptoms consistent with radiographic findings.20 In a study conducted by Helenius and associates, 24% of patients with ischemic monocular vision loss had acute brain infarcts on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW-MRI); 71% of these infarcts were asymptomatic.38 These findings were concordant with the study by Lee and associates.39 Although silent infracts detected as incidental findings may sometimes be considered clinically insignificant, they more than double the risk of subsequent stroke.40 All CRAO patients with silent brain lesions should undergo etiologic evaluation and management as recommended by the AHA/ASA.41 Another interesting observation of our study is the notable increase in incidence of stroke in CRAO patients over the years. This increase can partly be explained by an aging US population, and the increasing use of DW-MRI in the recent years, which is more sensitive than computed tomography imaging, resulting in higher detection rates.

Prior history of stroke or TIA was not an independent predictor of in-hospital stroke. We postulate that patients with prior cerebral ischemic event may have likely undergone interventions to reduce the risk of future stroke, such as treatment with antiplatelet/anticoagulation therapy, lipid-lowering drugs, lifestyle changes, or CEA. The available NIS data do not permit determination of whether or not such measures were undertaken.

Prior studies demonstrate significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CRAO patients. Incidence of MI in CRAO has been reported to be 21%.20 A recent study reported the mortality risk to be 8% and the combined risk of stroke, MI, or death at 2-year follow-up to be 32%.24 In this study, combined risk of stroke, TIA, MI, and death was 19%. The lower incidence is likely because this study only captures the risk of these events immediately following a CRAO, while others have reported these risks over a longer period of follow-up.

The strengths of this study include its large sample size and nationwide estimates, representative of the entire US population. As this study was conducted in an inpatient setting, we expect the diagnostic approach for identification of risk factors and stroke to be more thorough in comparison to outpatient settings. Limitations of the study include the lack of a control group and potential for misdiagnosis based on ICD-9 codes; however, the large sample size may mitigate or render negligible the risk of such misclassifications. This study did not capture long-term outcomes following discharge, which, although relevant, were beyond the scope of this investigation. Since this study was conducted in a hospital setting, the patient population might differ from that in an outpatient setting. Lastly, it is possible that the hospital course for a subset of patients may have been complicated by other comorbidities, resulting in inflated charges.

In summary, we report a significant burden of acute vascular ischemic events and mortality in the largest study of CRAO patients conducted to date. This study validates CRAO as an important clinical marker for future vascular ischemic events, including stroke and acute MI. The risk of CRAO-associated stroke is highest in women and in those with a history of hypertension, carotid artery stenosis, aortic valve disease, smoking, or alcohol abuse. As the incidence of CRAO associated stroke continues to rise in the United States, in the future the development of a risk prediction model can serve as a valuable and cost-effective adjunct for effective patient triaging and referral to the ED or nearest stoke center. This would ensure that high-risk CRAO patients undergo immediate evaluation within 24 hours, without incurring unnecessary costs on the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING/SUPPORT: NO FUNDING OR GRANT SUPPORT. FINANCIAL DISCLOSURES: THE FOLLOWING AUTHORS HAVE NO financial disclosures: Tahreem A. Mir, Ahmad Z. Arham, Wei Fang, Fahad Alqahtani, Mohamad Alkhouli, Julia Gallo, and David M. Hinkle. All authors attest that they meet the current ICMJE criteria for authorship.

Contributor Information

TAHREEM A. MIR, Department of Ophthalmology & Visual Science, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut, USA, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA

AHMAD Z. ARHAM, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA

WEI FANG, West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute, WVU Health Sciences Center Erma Byrd Biomedical Research Center, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

FAHAD ALQAHTANI, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

MOHAMAD ALKHOULI, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

JULIA GALLO, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA.

DAVID M. HINKLE, West Virginia University School of Medicine, Morgantown, West Virginia, USA

REFERENCES

- 1.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Central retinal artery occlusion: visual outcome. Am J Ophthalmol 2005;140(3):376–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Retinal artery occlusion: associated systemic and ophthalmic abnormalities. Ophthalmology 2009;116(10):1928–1936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Savino PJ, Glaser JS, Cassady J. Retinal stroke. Is the patient at risk? Arch Ophthalmol 1977;95(7):1185–1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schumacher M, Schmidt D, Jurklies B, et al. Central retinal artery occlusion: local intra-arterial fibrinolysis versus conservative treatment, a multicenter randomized trial. Ophthalmology 2010;117(7):1367–1375.e1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CS, Lee AW, Campbell B, et al. Efficacy of intravenous tissue-type plasminogen activator in central retinal artery occlusion: report from a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke 2011;42(8):2229–2234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rumelt S, Dorenboim Y, Rehany U. Aggressive systematic treatment for central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1999;128(6):733–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menzel-Severing J, Siekmann U, Weinberger A, Roessler G, Walter P, Mazinani B. Early hyperbaric oxygen treatment for nonarteritic central retinal artery obstruction. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;153(3):454–459.e452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahn SJ, Kim JM, Hong JH, et al. Efficacy and safety of intra-arterial thrombolysis in central retinal artery occlusion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013;54(12):7746–7755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudkin AK, Lee AW, Chen CS. Vascular risk factors for central retinal artery occlusion. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(4):678–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Callizo J, Feltgen N, Pantenburg S, et al. Cardiovascular risk factors in central retinal artery occlusion: results of a prospective and standardized medical examination. Ophthalmology 2015;122(9):1881–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Douglas DJ, Schuler JJ, Buchbinder D, Dillon BC, Flanigan DP. The association of central retinal artery occlusion and extracranial carotid artery disease. Ann Surg 1988; 208(1):85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park SJ, Choi NK, Yang BR, et al. Risk and risk periods for stroke and acute myocardial infarction in patients with central retinal artery occlusion. Ophthalmology 2015;122(11): 2336–2343.e2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biousse V, Nahab F, Newman NJ. Management of acute retinal ischemia: follow the guidelines! Ophthalmology 2018; 125(10):1597–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen TW, Pulido JS, Folk JC, Hyman L, Flaxel CJ, Adelman RA. Retinal and Ophthalmic Artery Occlusions Preferred Practice Pattern®. Ophthalmology 2017;124(2): P120–P143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2011;42(1):227–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atkins EJ, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. Translation of clinical studies to clinical practice: survey on the treatment of central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2009; 148(1):172–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abel AS, Suresh S, Hussein HM, Carpenter AF, Montezuma SR, Lee MS. Practice patterns after acute embolic retinal artery occlusion. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2017;6(1):37–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), Overview of the National (Nationwide) Inpatient Sample (NIS), Available at: https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed 9 November 2018.

- 19.US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer price index for all urban consumers: hospital services Available at: https://www.bls.gov/cpi. Accessed November 9, 2018.

- 20.Hayreh SS, Zimmerman MB. Ocular arterial occlusive disorders and carotid artery disease. Ophthalmol Retina 2017;1(1):12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hong JH, Sohn SI, Kwak J, et al. Retinal artery occlusion and associated recurrent vascular risk with underlying etiologies. PLoS One 2017;12(6):e0177663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt D, Hetzel A, Geibel-Zehender A, Schulte-Monting J. Systemic diseases in non-inflammatory branch and central retinal artery occlusion–an overview of 416 patients. Eur J Med Res 2007;12(12):595–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leavitt JA, Larson TA, Hodge DO, Gullerud RE. The incidence of central retinal artery occlusion in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Am J Ophthalmol 2011;152(5):820–823 e822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lavin P, Patrylo M, Hollar M, Espaillat KB, Kirshner H, Schrag M. Stroke risk and risk factors in patients with central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2018;196:96–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yen JC, Lin HL, Hsu CA, Li YC, Hsu MH. Atrial fibrillation and coronary artery disease as risk factors of retinal artery occlusion: a nationwide population-based study. Biomed Res Int 2015;2015:374616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Callizo J, Feltgen N, Ammermann A, et al. Atrial fibrillation in retinal vascular occlusion disease and non-arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy. PLoS One 2017;12(8):e0181766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dussault C, Toeg H, Nathan M, Wang ZJ, Roux JF, Secemsky E. Electrocardiographic monitoring for detecting atrial fibrillation after ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8(2):263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomsak RL, Hanson M, Gutman FA. Carotid artery disease and central retinal artery occlusion. Cleve Clin Q 1979; 46(1):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Appen RE, Wray SH, Cogan DG. Central retinal artery occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 1975;79(3):374–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mead GE, Lewis SC, Wardlaw JM, Dennis MS. Comparison of risk factors in patients with transient and prolonged eye and brain ischemic syndromes. Stroke 2002;33(10): 2383–2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson DC, Kappelle LJ, Eliasziw M, Babikian VL, Pearce LA, Barnett HJ. Occurrence of hemispheric and retinal ischemia in atrial fibrillation compared with carotid stenosis. Stroke 2002;33(8):1963–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coisy S, Leruez S, Ebran JM, Pisella PJ, Milea D, Arsene S. [Systemic conditions associated with central and branch retinal artery occlusions]. J Fr Ophtalmol 2013;36(9):748–757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bruno A, Jones WL, Austin JK, Carter S, Qualls C. Vascular outcome in men with asymptomatic retinal cholesterol emboli. A cohort study. Ann Intern Med 1995;122(4):249–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chang YS, Jan RL, Weng SF, et al. Retinal artery occlusion and the 3-year risk of stroke in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Am J Ophthalmol 2012;154(4):645–652.e641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rim TH, Han J, Choi YS, et al. Retinal artery occlusion and the risk of stroke development: twelve-year nationwide cohort study. Stroke 2016;47(2):376–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.French DD, Margo CE, Greenberg PB. Ischemic stroke risk in medicare beneficiaries with central retinal artery occlusion: a retrospective cohort study. Ophthalmol Ther 2018;7(1): 125–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Babikian V, Wijman CA, Koleini B, Malik SN, Goyal N, Matjucha IC. Retinal ischemia and embolism. Etiologies and outcomes based on a prospective study. Cerebrovasc Dis 2001;12(2):108–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helenius J, Arsava EM, Goldstein JN, et al. Concurrent acute brain infarcts in patients with monocular visual loss. Ann Neurol 2012;72(2):286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J, Kim SW, Lee SC, Kwon OW, Kim YD, Byeon SH. Co-occurrence of acute retinal artery occlusion and acute ischemic stroke: diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Ophthalmol 2014;157(6):1231–1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vermeer SE, Longstreth WT Jr, Koudstaal PJ. Silent brain infarcts: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol 2007;6(7): 611–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2018;49(3):e46–e110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]