Abstract

Background:

There are limited data examining the risk of prostate cancer (PCa) in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Objective:

To compare the incidence of PCa between men with and those without IBD.

Design, setting, and participants:

This was a retrospective, matched-cohort study involving a single academic medical center and conducted from 1996 to 2017. Male patients with IBD (cases = 1033) were randomly matched 1:9 by age and race to men without IBD (controls = 9306). All patients had undergone at least one prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening test.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis:

Kaplan-Meier and multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, stratified by age and race, evaluated the relationship between IBD and the incidence of any PCa and clinically significant PCa (Gleason grade group ≥2). A mixed-effect regression model assessed the association of IBD with PSA level.

Results and limitations:

PCa incidence at 10 yr was 4.4% among men with IBD and 0.65% among controls (hazard ratio [HR] 4.84 [3.34–7.02] [3.19–6.69], p < 0.001). Clinically significant PCa incidence at 10 yr was 2.4% for men with IBD and 0.42% for controls (HR4.04 [2.52–6.48], p < 0.001). After approximately age 60, PSA values were higher among patients with IBD (fixed-effect interaction of age and patient group: p = 0.004). Results are limited by the retrospective nature of the analysis and lack of external validity. Conclusions: Men with IBD had higher rates of clinically significant PCa when compared with age- and race-matched controls.

Patient summary:

This study of over 10 000 men treated at a large medical center suggests that men with inflammatory bowel disease may be at a higher risk of prostate cancer than the general population.

Keywords: Prostatic neoplasm, Prostate-specific antigen, Inflammatory bowel diseases

1. Introduction

While recommendations regarding screening for prostate cancer (PCa) with a serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test are controversial, several guideline panels support a shared decision-making approach [1]. Notably, the United States Preventative Services Task Force has acknowledged a need for additional research to inform screening recommendations for men at an increased risk of death from PCa, such as African Americans and those with a strong family history [2]. In general, it is important to better understand and quantify the risk of clinically significant PCa among vulnerable populations.

Epidemiologic studies have noted an association between chronic inflammation and PCa [3,4]. Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a common chronic inflammatory condition comprising Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [5]. Patients with IBD have an increased risk of gastrointestinal malignancy, as well as certain extraintestinal malignancies [6,7]. There are limited data describing the risk of PCa in men with IBD and no reports comparing PSA levels in men with and without IBD. Therefore, we performed a retrospective cohort study comparing the incidence of any and clinically significant PCa between men with and those without IBD who underwent PSA screening at a large academic medical center.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patient cohort

After obtaining internal review board approval, the Northwestern Medicine administrative dataset repository was queried for adult male patients who presented to any clinic within the Northwestern Medicine network from July 1996 through June 2014. All patients underwent at least one PSA screening test. We matched 1033 patients who had ever been diagnosed with IBD (cases) 1:9 to a randomly selected group of 9306 non-IBD patients (controls) by 10-yr age groupings (age defined at first PSA test) and race. IBD diagnosis was determined by International Classification of Disease-9 (ICD-9) codes (555 for CD and 556 for UC). Follow-up time for all patients was the duration between a patient’s first PSA test and last physician encounter. We conducted a random 5% chart review of the entire cohort to ensure accuracy.

2.2. Outcomes

The primary outcomes were a diagnosis of PCa (ICD-9 code 185) and a diagnosis of clinically significant PCa, defined as a Gleason score of ≤7 (Gleason grade groups 2–5) [8]. PCa diagnosis was confirmed by a chart review. Gleason score was determined from biopsy or surgical pathology if available. The secondary outcome was screening serum PSA value (Current Procedural Terminology code 84153) stratified by age range. If a patient was diagnosed with PCa, subsequent PSA tests were excluded. The incidence of metastatic disease (N+ or M + ) was also assessed by a chart review.

2.3. Covariates

Initial PSA value and the number of PSA tests were included in multivariable analyses. A history of abnormal rectal examination was determined by ICD-9 coding for an abnormal digital rectal examination (796.4) and/or prostate induration (600.10 and 600.11). Among patients with IBD, IBD-related covariates, including duration of disease (≤20 or <20 yr), history of bowel resection, and use of immunomodulatory medications such as infliximab, adalimumab, and vedolizumab, were determined by a chart review.

2.4. Statistical analysis

The number of abnormal rectal examinations, cases of any PCa, and cases of clinically significant PCa were compared between control and IBD groups over a standardized follow-up period of 5 yr. PCa incidences were calculated using Kaplan-Meier analyses. Hazard ratios (HRs) were generated using multivariable Cox models, stratified by the criteria used for patient matching (ie,10-yr age groups and race). Covariates that were time-dependent (ie total number of PSA tests and a history of an abnormal rectal examination) were allowed to vary over the study period [9]. Interaction analyses were used to examine the impact of several key variables (ie, the number of PSA results, baseline serum PSA value, and age at first PSA test) on the association of IBD with any PCa and clinically significant PCa.

We performed a sensitivity analysis of the IBD-PCa association excluding IBD cases in which a definitive diagnosis date—and therefore a history of IBD prior to PCa diagnosis in applicable patients—could not be confirmed. Crude incidences of PCa and clinically significant PCa per 100 000 person-years were compared between controls and cases. Last, Cox analyses for the outcomes of any PC and clinically significant PCa were also performed among men with IBD only, with the inclusion of IBD-related covariates.

To assess the association of IBD with PSA value, we fitted a mixed-effect regression model. If a patient underwent more than one PSA test, each observation was included. The model contained fixed effects for time, age, and IBD status, plus random effects for intercept and time from the first observation. To evaluate whether the effect of IBD status on the serum PSA level was dependent on age, we used a likelihood ratio test to evaluate the fixed-effect interaction of age and group (ie, control or IBD). While all PSA values were included in the mixed model, exclusively initial PSA values from each patient were used to represent PSA estimates graphically by age and IBD status. Mixed regression analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4. All other analyses were completed with Stata 14 with p < 0.05 being considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

The median age of both case and control groups at first PSA measurement was 53 yr (Table 1). Of the patients, 74% were white. Median follow-up time was longer for cases (6.5 yr) than for controls (4.7 yr). At 5 yr of follow-up, the median number of PSA tests was 2 for both groups. Moreover, after 5 yr, 355 control patients and 58 patients with IBD were noted to have abnormal rectal examinations.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients in IBD and control groups

| Characteristics | Controls | IBD |

|---|---|---|

| Total, n | 9306 | 1033 |

| Age (yr), median (IQR) | 53 (46–61) | 53 (46–62) |

| Age group (yr), n (%) | ||

| <40 | 630 (6.8) | 70 (8.0) |

| 40–49 | 2602 (28.0) | 288 (27.9) |

| 50–59 | 3304 (35.5) | 366 (34.7) |

| 60–69 | 1978 (21.3) | 221 (21.4) |

| 70+ | 792 (8.5) | 47 (8.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 6899 (74.1) | 767 (74.3) |

| Black | 757 (8.1) | 85 (8.2) |

| Asian | 72 (0.8) | 8 (0.8) |

| Other | 579 (6.2) | 66 (6.4) |

| Declined/unknown | 998 (10.7) | 107 (10.3) |

| Number of PSA results at 5-yr follow-up, median (IQR) | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) |

| Number of abnormal rectal examinations at 5-yr follow-up | 355 | 58 |

| Number of prostate cancer cases at 5-yr follow-up | 29 | 30 |

| Number of clinically significant prostate cancer cases at 5-yr follow-up | 17 | 16 |

| Follow-up time among patients without prostate cancer (yr), (IQR) | 4.7 (0.7–9.0) | 6.5 (2.5–10.5) |

IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; IQR = interquartile range; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

3.2. Dataset validation

Clinical variables for 455 patients (5%) were confirmed via a chart review. One discrepancy (0.2%) was observed in the date of PCa diagnosis, two discrepancies in the date of first PSA test (0.4%), and three discrepancies in patients who had undergone prostate biopsy (0.6%). However, there were no discrepancies in PCa diagnosis, Gleason score, CD or UC diagnosis, age at first PSA, and PSA values. Given minimal discrepancies, no adjustments were felt to be necessary.

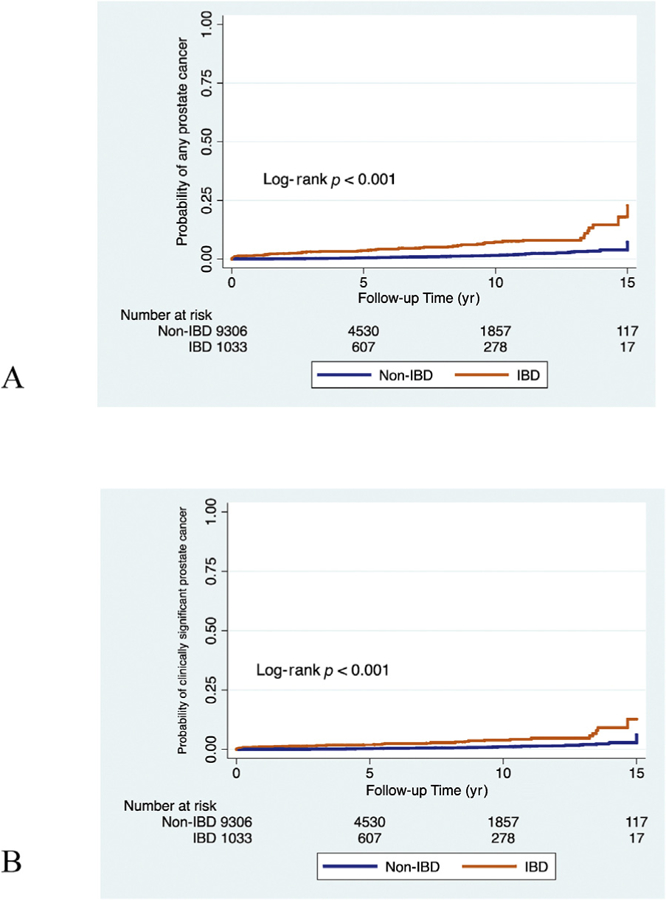

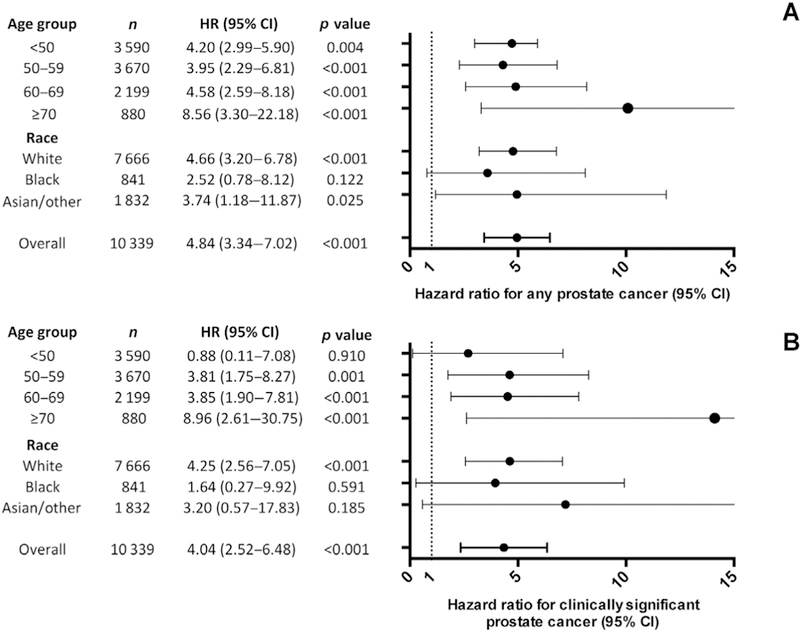

3.3. Association between IBD and PCa

The 5- and 10-yr incidences of any PCa were 2.8% and 4.4% for cases and 0.25% and 0.65% for controls, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001; Fig. 1). The incidences of clinically significant PCa were 1.6% and 2.4% for cases and 0.17% and 0.42% for controls at 5 and 10 yr, respectively (log-rank p < 0.001). In multivariable Cox proportional hazard models, IBD was associated with any PCa (HR 4.84 [3.34–7.02], p < 0.001; Fig. 2) and clinically significant PCa (HR 4.04 [2.52–6.48], p < 0.001). When Cox analyses were repeated excluding patients with IBD whose diagnosis date could not be determined, IBD was still associated with any PCa (HR 4.44 [2.98–6.62], p < 0.001; Supplementary Table 1) and clinically significant PCa (HR 3.72 [2.15–6.42], p < 0.001). In total, six men without IBD and three with IBD were diagnosed with metastatic PCa (N+ or M +). The incidences at 10 yr were 0.19% for cases 0.03% for controls (log-rank p = 0.061).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier failure curves for (A) any prostate cancer and (B) clinically significant prostate cancer, stratified by IBD status. IBD = inflammatory bowel disease.

Fig. 2.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazard models of the association of IBD with (A) any prostate cancer and (B) clinically significant prostate cancer, stratified by 10-yr age groups and race. Models included number of PSA tests, baseline PSA value continuous by 1 ng/ml, and history of abnormal rectal examination or nodular prostate. CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

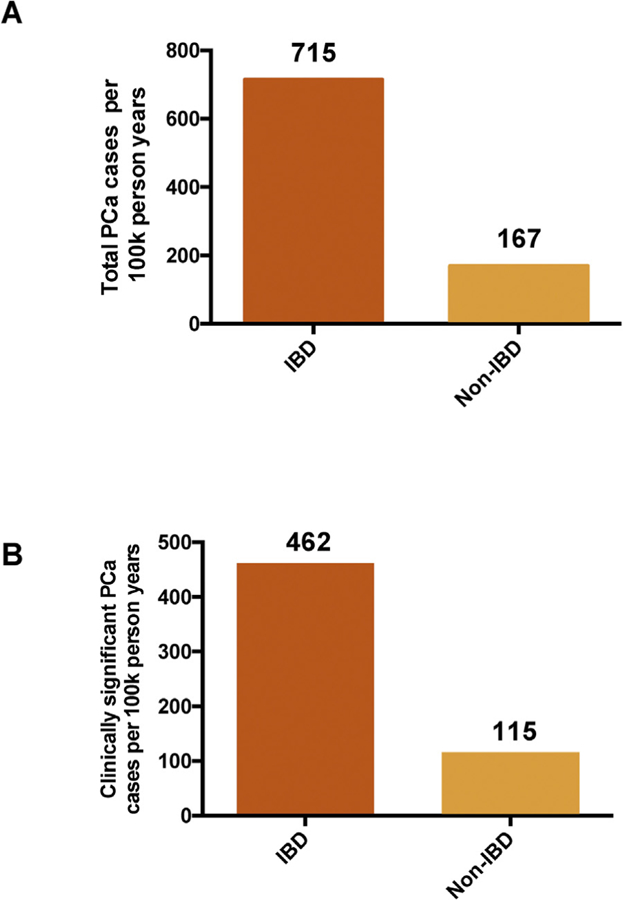

The crude incidences of any PCa were 715 cases in patients with IBD and 167 cases among controls per 100 000 person-years (Fig. 3). The incidences of clinically significant PCa were 462 cases in patients with IBD and 115 cases among controls per 100 000 person-years.

Fig. 3.

Incidence of (A) any prostate cancer and (B) clinically significant prostate cancer per 100 000 person-years, stratified by IBD status. IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; PCa = prostate cancer; 100k = 100 000.

3.4. Interaction analyses

There was no interaction between IBD and the number of PSA tests (p = 0.5), age (p = 0.2), or baseline PSA value (p = 0.5) for a diagnosis of any PCa (Supplementary Fig. 1). This was similar for a diagnosis of clinically significant PCa.

3.5. IBD characteristics and PCa

Among patients with IBD, disease duration of >20 yr (p = 0.6), use of biologic medications (p = 0.6), a history of bowel resection (p = 0.4), and a diagnosis of UC versus CD (p = 0.6) were not associated with a diagnosis of any PCa (Supplementary Table 2). There was similarly no significant association with clinically significant PCa (p = 0.2, p = 0.7, p = 0.6, and p = 0.3, respectively).

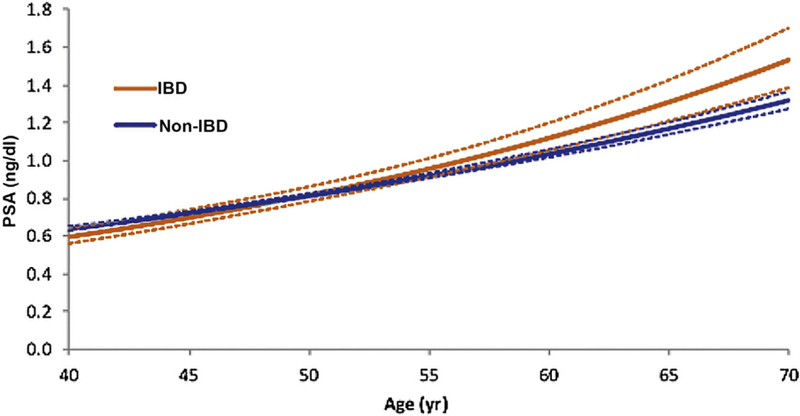

3.6. PSA values by IBD status

A total of 27 221 PSA measurements were assessed for men without IBD and 3357 for men with IBD. There was a slight trend toward a higher number of PSA tests and higher PSA values among patients with IBD (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). Overall, 80.3% of men without IBD and 76.3% with IBD underwent one to four PSA tests. While PSA estimates were similar in younger patients, age-specific PSA values were significantly higher in patients with IBD in older age, starting at approximately age 60 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3). The impact of older age on the relationship between IBD status and PSA level is reflected by the fixed-effect interaction of age and IBD status (p = 0.004).

Fig. 4.

Initial PSA value by age and IBD status estimated by longitudinal mixed-effect regression. IBD = inflammatory bowel disease; PSA= prostate-specific antigen.

4. Discussion

The prevalence of PCa and the morbidity associated with both PCa and its treatment necessitate shared decision making regarding PSA-based screening. Factors influencing either the risk of PCa or serum PSA values may have implications for the shared decision-making process. In this retrospective, matched-cohort analysis, IBD was associated with a substantially increased risk of any and clinically significant PCa among a screened population. Further, older men with IBD had higher serum PSA levels than matched controls.

Two recent population-based series noted an association between PCa and UC [10,11]. Neither detected an association between PCa and CD. Importantly, both cohorts had a greater number of older patients (ie, age >40 yr) with UC than with CD. As the risk of PCa increases with age, cohort composition may have influenced the results of these studies. In contrast, a meta-analysis of population-based studies including >12 000 patients found no increased incidence of PCa among patients with IBD [7]. This series did not report PCa screening patterns, and seven of eight included studies were performed before the PSA screening era [12]. Further, this meta-analysis included adult patients of all ages, rather than patients of a representative age range for PCa screening.

Our study reports an increased risk of any PCa among men with IBD who were in an appropriate age group to be considered for PCa screening. Importantly, our study is the first to demonstrate an increased risk of clinically significant PCa for men with IBD, as previous investigations did not assess PCa incidence by grade. This is relevant for a cohort of men with a chronic illness. Such patients may already be subjected to frequent healthcare encounters, and a diagnosis of low-grade PCa may lead to unnecessary additional treatment or observation. However, men with higher-grade PCa often benefit from treatment in terms of survival and prevention of metastatic disease [13]. Although we did not find any association between IBD and metastatic PCa, this analysis was limited by the number of cases.

We attempted to explain our findings regarding the increased incidence of PCa by further assessing the trends in PSA values. Our results indicate that with increasing age, there was a growing disparity in median PSA levels between cases and controls. While the incidence of PCa may have contributed to discrepancies in PSA values, prostatic inflammation is also known to elevate serum PSA levels. The link between prostatitis and PSA is thought to be due to disruption of the cellular architecture of the prostate [14]. Subsequent repetitive tissue destruction and regeneration may play a role in the development of PCa [15].

The local inflammation observed in IBD frequently (CD) or invariably (UC) involves the rectum. IBD also exerts a systemic inflammatory effect, causing elevations of serum acute-phase reactants, such as C-reactive protein [16]. Indeed, elevations in acute-phase reactants have previously been associated with higher PSA values [17]. It is conceivable that the local or systemic inflammatory state resulting from IBD may lead to chronic prostatic inflammation and, in some cases, eventual development of PCa. Future work discerning a mechanistic connection between IBD-related inflammation, PSA levels, and incident PCa is warranted.

It is also possible that reduced immune surveillance— rather than excessive inflammation—could provide a link between IBD and PCa. Immunomodulatory treatments used to mitigate the autoimmune activity of IBD have been associated with an increased risk of extraintestinal malignancy [18]. In our study, we did not detect an increased risk of PCa among men with IBD on immunomodulatory medications. However, a limitation of our analysis was not accounting for the duration of medication use. While the potential role of immunomodulatory medications is intriguing, there is currently insufficient evidence to demonstrate a link between these drugs and PCa [19].

PCa and IBD each have a significant genetic predisposition [20,21]. Genome-wide association studies have identified numerous susceptibility alleles for IBD and PCa [22,23]. Shared risk alleles could partially explain the association between IBD and PCa. A notable example is folate hydrolase 1 (FOLH1) or prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA). FOLH1/PSMA is upregulated in IBD. Inhibition of FOLH1/PSMA has ameliorated the evidence of colitis in mice [24]. FOLH1/PSMA is also overexpressed in PCa [25]. The recent work by Kaittanis et al. [26] found that FOLH1/PSMA induced phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3 K) signaling, a known pathogenic pathway in PCa. In preclinical models, inhibition of FOLH1/PSMA decreased PI3 K signaling and led to tumor regression. FOLH1/PSMA is a robust illustration of the potential for shared genetic susceptibility between IBD and PCa.

It is conceivable that high rates of PCa among IBD patients may result from greater outcome ascertainment in the IBD group, as patients with IBD commonly have frequent encounters with healthcare providers [27]. Additionally, based on the nature of the disease, men with IBD would be more likely to undergo rectal examinations. Indeed, we noted more abnormal rectal examinations among men with IBD. In interaction analyses, we report that the relationship of IBD and PCa was not highly dependent on the number of PSA screening tests. However, in our study, we were not able to directly measure healthcare utilization or its effect on the primary outcome. The significance of contact with healthcare providers remains an important question underlying the association between IBD and PCa, which requires further investigation.

The risk of PCa increases with age. Further, previous studies have found that subtle elevations in PSA above the age-specific median level are predictive of increased rates of PCa and advanced PCa [28]. In our study, interaction analyses demonstrated that the association between IBD and PCa does not appear to be highly dependent on older age or PSA values. These findings highlight the important role of investigating the benefits and harms of PCa screening in high-risk populations. Future studies should seek to determine the appropriate age to begin discussing PCa screening and interpretations of PSA values among patients with IBD.

Strengths of our study include cohort size and distribution over a representative age range, and longitudinal follow-up of all patients over a period of nearly 21 yr. A random chart review of our data demonstrated minimal discrepancies in the primary outcomes. Importantly, the findings of our study were highly statistically significant, even after adjustment for pertinent covariates.

Our study has several limitations. The analyses were retrospective and thus cannot account for unmeasured variables, such as disease location in IBD, markers of IBD severity (ie, C-reactive protein), family history of PCa, and socioeconomic data. The study assessed patients seen at an academic medical center, which limits its external validity. We report PCa diagnosis but not morbidity or mortality related to PCa and its treatments. Nevertheless, stratification by Gleason grade group allowed us to identify clinically significant PCa by tumor grade. We were further not able to determine a surrogate covariate representing healthcare utilization such as the number of physician office visits over time [27]. We also acknowledge that some patients may have received PSA tests outside of the Northwestern health system, which may explain why some men were elderly (>70 yr) at the start of their PSA testing. However, this would not alter the primary outcome of incident PCa.

5. Conclusions

In a retrospective matched-cohort study, men with IBD who underwent PSA-based PCa screening had higher rates of any and clinically significant PCa when compared with age- and race-matched men without IBD. These findings warrant future prospective investigation to better understand the relationship between IBD and PCa.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosures: Shilajit D. Kundu certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: None.

Funding/Support and role of the sponsor: None.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2018.11.039.

References

- [1].Carter HB. American Urological Association (AUA) guideline on prostate cancer detection: process and rationale. BJU Int 2013;112:543–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Owens DK, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 2018;319:1901–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Platz EA, De Marzo AM. Epidemiology of inflammation and prostate cancer. J Urol 2004;171:S36–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dennis LK, Lynch CF, Torner JC. Epidemiologic association between prostatitis and prostate cancer. Urology 2002;60:78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:1424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yadav S, Singh S, Harmsen WS, Edakkanambeth Varayil J, Tremaine WJ, Loftus EV Jr. Effect of medications on risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases: a population-based cohort study from Olmsted County, Minnesota. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pedersen N, Duricova D, Elkjaer M, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Jess T. Risk of extra-intestinal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of population-based cohort studies. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:1480–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Epstein JI, Egevad L, Amin MB, et al. The 2014 International Society of Urological Pathology (ISUP) Consensus Conference on Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: definition of grading patterns and proposal for a new grading system. Am J Surg Pathol 2016;40:244–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zhang Z, Reinikainen J, Adeleke KA, Pieterse ME, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM. Time-varying covariates and coefficients in Cox regression models. Ann Transl Med 2018;6:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jung YS, Han M, Park S, Kim WH, Cheon JH. Cancer risk in the early stages of inflammatory bowel disease in Korean patients: a nation-wide population-based study. J Crohns Colitis 2017;11:954–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Jess T, Horvath-Puho E, Fallingborg J, Rasmussen HH, Jacobsen BA. Cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease according to patient phenotype and treatment: a Danish population-based cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1869–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Potosky AL, Miller BA, Albertsen PC, Kramer BS. The role of increasing detection in the rising incidence of prostate cancer. JAMA 1995;273:548–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Bill-Axelson A, Holmberg L, Garmo H, et al. Radical prostatectomy or watchful waiting in early prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 2014;370:932–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Irani J, Levillain P, Goujon JM, Bon D, Dore B, Aubert J. Inflammation in benign prostatic hyperplasia: correlation with prostate specific antigen value. J Urol 1997;157:1301–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Sfanos KS, De Marzo AM. Prostate cancer and inflammation: the evidence. Histopathology 2012;60:199–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Vermeire S, Van Assche G, Rutgeerts P. C-reactive protein as a marker for inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2004;10:661–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McDonald AC, Vira MA, Vidal AC, Gan W, Freedland SJ, Taioli E. Association between systemic inflammatory markers and serum prostate-specific antigen in men without prostatic disease—the 2001–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Prostate 2014;74:561–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Biancone L, Onali S, Petruzziello C, Calabrese E, Pallone F. Cancer and immunomodulators in inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:674–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Nyboe Andersen N, Pasternak B, Basit S, et al. Association between tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonists and risk of cancer in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA 2014;311:2406–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Laharie D, Debeugny S, Peeters M, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease in spouses and their offspring. Gastroenterology 2001;120:816–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bratt O, Drevin L, Akre O, Garmo H, Stattin P. Family history and probability of prostate cancer, differentiated by risk category: a nationwide population-based study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016:108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Teerlink CC, Thibodeau SN, McDonnell SK, et al. Association analysis of 9,560 prostate cancer cases from the International Consortium of Prostate Cancer Genetics confirms the role of reported prostate cancer associated SNPs for familial disease. Hum Genet 2014;133:347–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Franke A, McGovern DPB, Barrett JC, et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis increases to 71 the number of confirmed Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet 2010;42:1118–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rais R, Jiang W, Zhai H, et al. FOLH1/GCPII is elevated in IBD patients, and its inhibition ameliorates murine IBD abnormalities. JCI Insight 2016:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang T, Song B, Zhu W, et al. An ileal Crohn’s disease gene signature based on whole human genome expression profiles of disease unaffected ileal mucosal biopsies. PLoS One 2012;7:e37139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kaittanis C, Andreou C, Hieronymus H, et al. Prostate-specific membrane antigen cleavage of vitamin B9 stimulates oncogenic signaling through metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Exp Med 2018;215:159–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Kappelman MD, Porter CQ, Galanko JA, et al. Utilization of health-care resources by U.S. children and adults with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2011;17:62–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Catalona WJ, Smith DS, Ornstein DK. Prostate cancer detection in men with serum PSA concentrations of 2.6 to 4.0 ng/mL and benign prostate examination. Enhancement of specificity with free PSA measurements. JAMA 1997;277:1452–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.