Abstract

Background

Medical record review (MRR) is used to assess the quality and safety in hospitals. It is increasingly used to compare institutions. Therefore, the external reproducibility should be high. In the current study, we evaluated this external reproducibility for the assessment of an adverse event (AE) in a sample of records from two university medical centres in the Netherlands, using the same review method.

Methods

From both hospitals, 40 medical records were randomly chosen from patient files of deceased patients that had been evaluated in the preceding years by the internal review committees. After reviewing by the external committees, we assessed the overall and kappa agreement by comparing the results of both review rounds (once by the own internal committee and once by the external committee). This was calculated for the presence of an AE, preventability and contribution to death.

Results

Kappa for the presence of AEs was moderate (k=0.47). For preventability, the agreement was fair (k=0.39) and poor for contribution to death (k=−0.109).

Conclusion

We still believe that MRR is suitable for the detection of general issues concerning patient safety. However, based on the outcomes of this study, we would advise to be careful when using MRR for benchmarking.

Keywords: medical record review, hospital, reliability, external committee, adverse event, PABAK

Introduction

In many countries worldwide, healthcare inspection increasingly demand information on the quality and safety of patient care in hospitals. Several tools have been implemented by hospitals for the monitoring of their patients’ safety.1 2 A widely used tool is systematic medical record review (MRR). In the Netherlands, hospitals are obliged to either arrange an internal MRR system or take part in a national monitoring programme of care-related harm (performed every 4 years) executed by the Netherlands Institute for health services research (NIVEL).3–5

Hospitals using an MRR system frequently evaluate a subset of records (eg, every 10th admission) to lower the burden of MRR or select cases most likely to contain adverse events (AEs) (eg, only patients who died during hospitalisation). An additional method to lower the burden of MRR for physicians is to use a trigger system, which is executed by nurses in a previously defined set of records. When one or more triggers are found, the record is evaluated by a review committee. The results of this MRR should be reliable and valid because the outcome could lead to changes in care for future patients. Therefore, ideally, results must be both internally and externally reproducible. Internal reproducibility is necessary to obtain support for proposed improvements within a given institution. External reproducibility is necessary to compare results across institutions (benchmarking). However, well-defined criteria guiding the reviewer in how to fulfil a good MRR have not been specified clearly in international literature or guidelines.6–11

In the current study, we focus on the committee judgement and analyse the external reproducibility of the committee judgement on a sample of records from two university hospitals in the Netherlands, using the same review method.

Moreover, we also evaluate the root cause of potentially preventable AEs and their corresponding reproducibility.

Methods

Selection of records

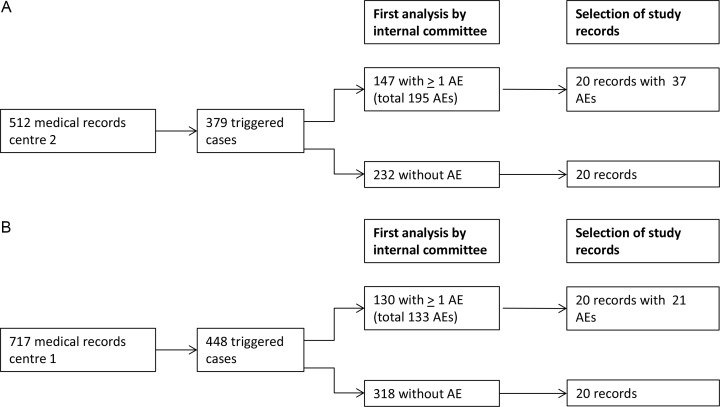

For both hospitals, 40 medical records were extracted from patient files of deceased patients that had been investigated and completed in the preceding 2 years by the internal committees (2014–2016) (hospital 1: 448 out of 717 records, hospital 2: 379 out of 512 records, figure 1A,B). The first step of the selection was as follows: records were selected according to the expertise of the committee members that participated (see section study). Then, the sample was randomly chosen from these departments. The selection of the records was executed by DK using the Excel random generator.

Figure 1.

(A and B) Medical record selection for centres 1 and 2. AEs, adverse events.

Furthermore, 50% of the records were selected out of the group with suitable records with an AE and the other half out of the group without an AE. Records selected for the committee from hospital 1 comprise patients originally treated by cardiology, surgery or internal medicine departments. For the committee from hospital two, they were originally treated by internal medicine, surgery, intensive care unit, cardiology or the neurology department. Since we wanted to investigated the external reliability of the review process only, we selected records in which nurses had found triggers when they were evaluated for the first time by the internal committee.

Study

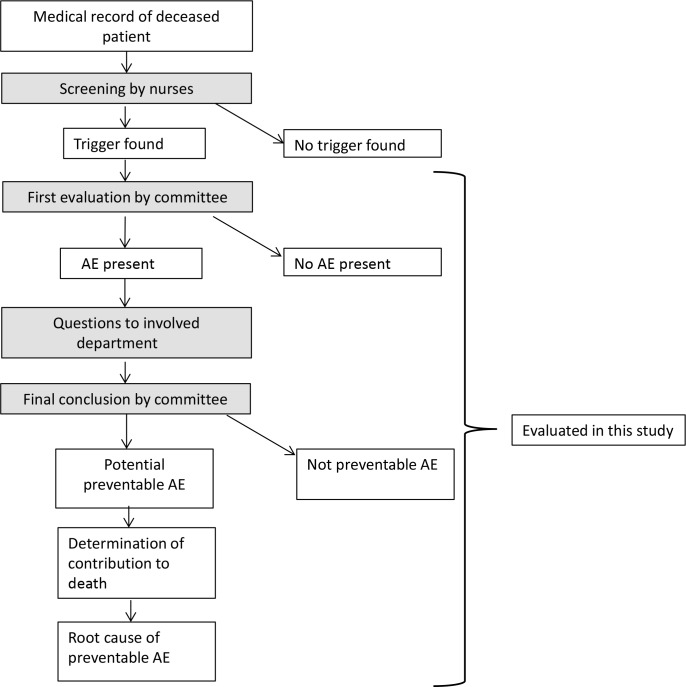

In 2016, we gathered two times for three consecutive days (in 2016) and the selected medical records were evaluated on location by the delegates of the external hospital committee. The committee of centre 1 thus evaluated in this study the records of centre 2 and vice versa. The admission department of the patient determined which specialist would (preferably) investigate a specific record. If this would be, for example, surgery, then a surgeon from the committee would evaluate the record. After these 3 days, the outcome of the evaluation by the delegates was discussed in a consensus meeting in which at least the three delegates were present. This consensus meeting was performed by the committees separately. During this meeting, a conclusion had to be reached on whether an AE had occurred. Furthermore, its potential preventability was assessed and the potential contribution of the AE to the death of the patient was determined. There was no time limitation for the review or the discussion in the committee. Each committee was blinded for the results of the first evaluation of the records by the other committee. The study process is further clarified in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Medical record review procedure. AE, adverse event.

Committees

For hospital 1, the delegates were as follows: an internist, a surgeon, and a cardiologist; there has been an MRR committee in this centre since 2008.

At hospital 2, the delegates were as follows: an internist, cardiothoracic surgeon and a neurologist; they started with MRR, according to the same format as hospital 1, in 2014. All reviewers took part in the national NIVEL studies and were therefore trained in the same fashion.5

During the previous years, both committees used the same review procedure. Previous research showed the results of this internal MRR to be acceptably reliable.12

Training

For the participation in the NIVEL studies, the nurses and physicians followed a 1-day training in small groups (maximum 12 participants) led by one member of the research team and one experienced nurse or physician, respectively. During the training, the study protocol, definitions and review forms were explained and examples of (preventable) AEs were discussed. The reviewers practised with cases and they were provided with a review manual. After 1 month of reviewing, the reviewers had a half-day training session to discuss their problems concerning the review process and definitions and to update the reviewers with the latest insights about the review process. These training sessions were frequently repeated during data collection.

Statistics and analyses

We aimed for a kappa of 0.6 or more, while we expected a kappa of 0.75. With a type 1 error of 0.05 and a type 2 error of 0.20, a sample size of 80 cases was found to be sufficient.13

To evaluate the output of the external review, we performed the following analyses: overall agreement and corresponding kappa agreement with a 95% CI. This was executed for the following variables: the presence of an AE, the presence of a potentially preventable AE and the presence of an AE which had contributed to the death of the patient.

By using cross tabulation, we calculated the observed overall agreement (accuracy) within the four groups (presence, preventability, contribution to death and root cause) with the corresponding 95% CI.

Prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) calculations were done and reported along with kappa, to show how data would have been with equal distributions of positive and negative test results. Finally, corresponding prevalence and bias indices were calculated.14

Furthermore, for every medical record separately, we evaluated the AEs that the committees found. We checked if the same AEs were found as during the first evaluation. If more than one AE was found, we checked if at least the same AE compared with the first evaluation was present. This was also done for preventability of the AEs and the contribution to death of all AEs.

The values of kappa were categorised as follows: the degree of agreement was categorised as poor (κ<0), slight (κ=0.00–0.20), fair (κ=0.21–0.40), moderate (κ=0.41–0.60), substantial (κ=0.61–0.80) or almost perfect (κ=0.81–1.00).15

Definitions

An AE was defined as an unintended outcome caused by the (non-)action of a caregiver and/or the healthcare system resulting in temporary or permanent disability or death of the patient.16

When an AE had been identified, its potential preventability was assessed (subdivided in the categories not preventable and potentially preventable) and the potential contribution of the AE to the death of the patient was determined (subdivided into: no contribution and potential contribution).

Data storage

All results were saved using software provided by Medirede, Clinical File Search V.3 (Mediround BV, 2015).

Data safety

The study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee (of both participating centres). To guarantee privacy, the medical records were only accessible at the centre itself. The selected records were accessible in the digital environment of the hospital. Furthermore, reviewers signed confidentiality contracts.

Results

In all, 80 records in total were reassessed; here, we present the results after review by the other committee. Outcomes for all records were available.

Medical records overall agreement

Table 1 shows the evaluation of the cases regarding the presence of an AE. The overall agreement was 74% and the corresponding kappa 0.48 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.67). PABAK was 0.48 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.67).

Table 1.

Evaluation of the committees regarding the presence of an AE

| AE present (committee 1) | AE not present (committee 1) | ||

| AE present (committee 2) | 34 | 14 | 48 |

| AE not present (committee 2) | 7 | 25 | 32 |

| 41 | 39 | 80 |

AE, adverse event.

Table 2 shows the number of AEs that were found by two teams, the evaluation regarding the potential preventability of this AE. The overall agreement regarding the preventability was therefore 71% and the kappa agreement 0.39 (95% CI 0.08 to 0.69). PABAK was 0.41 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.72).

Table 2.

Evaluation of the committees regarding the potential preventability of the AEs

| AE potentially preventable (committee 1) | AE not preventable (committee 1) | ||

| AE potentially preventable (committee 2) | 8 | 3 | 11 |

| AE not preventable (committee 2) | 7 | 16 | 23 |

| 15 | 19 | 34 |

AEs, adverse events.

Table 3 shows the evaluation of both teams regarding the contribution of the AE to death of the patient. The overall agreement regarding this contribution of the AE was 65% and the corresponding kappa agreement was −0.109 (95% CI −0.24 to 0.02). PABAK was 0.29 (95% CI 0 to 0.61).

Table 3.

Evaluation of the committees regarding the potential contribution of the AEs to death

| AE contributed (committee 1) | AE no contribution (committee 1) | ||

| AE contributed (committee 2) | 22 | 2 | 24 |

| AE no contribution (committee 2) | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| 32 | 2 | 34 |

AEs, adverse events.

Root cause analysis

The total number of cases with a potentially preventable AE according to both committees, hence labelled with a suspected cause, was 4. The overall agreement on this cause was 71%, with a kappa of 0.481 (95% CI 0 to 1).

Discussion

This study shows that, although the overall agreement of a judgement seems promising (as shown in table 1), the agreement of the reviewers for the presence of an AE is moderate with a kappa of 0.47. The agreement for the preventability was fair (k=0.39) and for the contribution of the AEs to death was poor (k=−0.109).17 The calculations of the PABAK show that the prevalence and bias had a negligible effect on the results. Only for the contribution of the AE to the death of the patient, an effect of the prevalence was shown. This indicates that the external reproducibility of MRR is not optimal and needs improvement.18

The NIVEL studies reported comparable results for the agreement between external reviewers. Their kappa agreement ranged between 0.24 and 0.47 for the presence of an AE. For preventability of an AE, the kappa was found to be 0.43. The improvement was explained by more intensified training.3 4

Sharek et al 19 and Landrigan et al 20 also show a moderate agreement for the AE presence and its severity between internal review teams and external review teams. However, the performance of these teams was not evaluated in a second hospital with different cases. This makes a comparison with our study difficult. Finally, Schildmeijer et al 21 showed a comparable agreement for the presence of an AE between teams using the global trigger tool (GTT) method.

Strong points of our study are as follows: the blinding of the two committees for the results of the first review by the other committee. Furthermore, we have chosen two comparable committees from two university hospitals using the same review method, to exclude that the review method itself caused any differences that would be found. Also, this is the first study in which committees of two hospitals review each other’s medical records for the evaluation of the external reproducibility. Contrarily to the NIVEL studies, which only compare results of two external committees, we compared the review of an external with an internal committee as is more common in other studies.19 22 Also, we believe that the reviewers in both committees can be seen as experts, since they evaluate medical records on a regular base (not only for study purposes).23 Furthermore, when we started the study, both teams already performed MRR for at least 3 years. The number of records evaluated by these two committees per year far exceeded the total number of records in the study by Landrigan et al.23 This study showed that the agreement improved when the reviewers gained more experience, which we do not think could be the case for our reviewers since they were already experienced at the start of our study. Obviously, there are also some points for improvement.

In our study, we cannot exclude differences in the performance of the two committees although both of them apply the same review method. Reasons for this could be as follows. First, the clinical background of the reviewers was slightly different. Second, committee 1 gave their final judgement after consulting other committee members who were not involved in scrutinising the 40 cases from the external review. Whereas committee 2 recorded the final judgement after reaching consensus in their group of three members. Finally, centre 2 has been active for a shorter period and aims to detect all AEs, whereas centre 1 with a longer experience focuses on the most severe and preventable AEs. The detection rate of AEs in all records (preventable and not preventable) is therefore much higher in centre 2 than in centre 1 (29% vs 18%).

Also, the number of records in which the root cause of the AE was noted was too small to draw conclusions on the agreement (this is also reflected by the large CI). Furthermore, committee 1 consisted partly of recently retired specialists while the other committee consisted of solely active physicians. Centre 1 chose to use the expertise of retired specialists since they have more time for the investigation of the records compared with presently active specialists who need to review medical records on top of their usual work. At the same time, in centre 2, the active specialists in the committee get dedicated time for their MRR. Additionally, although the committees were instructed to use their common method for review and final decision we cannot exclude any influence of the fact that the review of the 40 cases in the other hospital was done especially for study purposes. Finally, some of the medical records contained more than 1 AE, which made it easier for the external committee to find at least one of these AE; this could have led to an overestimation of the external reproducibility. Most MRR studies call for more research and exploration of possibilities for improving the inter-rater reliability since there is a need for more good quality studies on this topic.9 24–28 However, a recent article by Leistikow endorses otherwise. According to this article, the main reason for the disappointing reproducibility of MRR is because it depends on the values and view of the person who is performing the review.29 30 At the same time, the definitions of an AE and its preventability are changing over time.31 Moreover, we should not only apply traditional medical research methods for evaluating patient safety but also involve behavioural and social sciences. Organisational behaviour research in healthcare, for example, has highlighted the psychological, social, cultural and economic obstacles to a simple implementation of a solution. These sciences can help in understanding the complexity of patient safety.32 33 Combining these approaches could provide a better understanding of the complexity of patient safety and help with the design of interventions that are really beneficial for patients.29

In conclusion, we think that MRR is suitable for the detection of general issues in patient safety and also for the discussion of individual cases. However, the suboptimal reproducibility of MRR reduces its potential for benchmarking. Finally, we think at least a better definition of preventability and also of contribution to death is needed if we want to compare the outcomes between hospitals.

Footnotes

Contributors: DOK was involved in the design, analysis and interpretation of the data and drafting of the article. RR was involved in the design, interpretation of analysis, critical revision of the manuscript. RG, RE, RK and MHP were involved in the interpretation of the data and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Griffin FA. IHI Global Trigger Tool for Measuring Adverse Events : IHI Innovation Series white paper. 2nd edn Cambridge, Massachusetts: Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med 1991;324:370–6. 10.1056/NEJM199102073240604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Adverse events and potentially preventable deaths in Dutch hospitals: results of a retrospective patient record review study. Qual Saf Health Care 2009;18:297–302. 10.1136/qshc.2007.025924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Baines RJ, Langelaan M, de Bruijne MC, et al. Changes in adverse event rates in hospitals over time: a longitudinal retrospective patient record review study. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:290–8. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zegers M, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, et al. Design of a retrospective patient record study on the occurrence of adverse events among patients in Dutch hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res 2007;7 10.1186/1472-6963-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nabhan M, Elraiyah T, Brown DR, et al. What is preventable harm in healthcare? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12 10.1186/1472-6963-12-128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Weingart SN. Finding common ground in the measurement of adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care 2000;12:363–5. 10.1093/intqhc/12.5.363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murff HJ, Patel VL, Hripcsak G, et al. Detecting adverse events for patient safety research: a review of current methodologies. J Biomed Inform 2003;36:131–43. 10.1016/j.jbi.2003.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Unbeck M, Schildmeijer K, Henriksson P, et al. Is detection of adverse events affected by record review methodology? an evaluation of the "Harvard Medical Practice Study" method and the "Global Trigger Tool". Patient Saf Surg 2013;7 10.1186/1754-9493-7-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walshe K. Adverse events in health care: issues in measurement. Qual Health Care 2000;9:47–52. 10.1136/qhc.9.1.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jha AK, Classen DC. Getting moving on patient safety–harnessing electronic data for safer care. N Engl J Med 2011;365:1756–8. 10.1056/NEJMp1109398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klein DO, Rennenberg RJMW, Koopmans RP, et al. Adverse event detection by medical record review is reproducible, but the assessment of their preventability is not. PLoS One 2018;13:e0208087 10.1371/journal.pone.0208087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Walter SD, Eliasziw M, Donner A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med 1998;17:101–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:423–9. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90018-V [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wagner C, Wal G, van der. Voor een goed begrip: bevordering patiëntveiligheid vraagt om heldere definitie. Med Contact 2005;60:1888–91. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Monto AS, Dickson CB, Landis JR. Utilization and acceptability of influenza A/New Jersey/76 virus vaccine in Oakland County, Michigan. J Infect Dis 1977;136:S693–S698. 10.1093/infdis/136.Supplement_3.S693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McHugh ML. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem Med 2012;22:276–82. 10.11613/BM.2012.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sharek PJ, Parry G, Goldmann D, et al. Performance characteristics of a methodology to quantify adverse events over time in hospitalized patients. Health Serv Res 2011;46:654–78. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01156.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Landrigan CP, Parry GJ, Bones CB, et al. Temporal trends in rates of patient harm resulting from medical care. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2124–34. 10.1056/NEJMsa1004404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schildmeijer K, Nilsson L, Arestedt K, et al. Assessment of adverse events in medical care: lack of consistency between experienced teams using the global trigger tool. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:307–14. 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schildmeijer KGI, Nilsson L, Arestedt K, et al. The assessment of adverse events in medical care; lack of consistency between experienced teams using the Global Trigger Tool’. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:271–2. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Landrigan CP, Stockwell D, Toomey SL, et al. Performance of the global assessment of pediatric patient Safety (GAPPS) tool. Pediatrics 2016;137 10.1542/peds.2015-4076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hanskamp-Sebregts M, Zegers M, Vincent C, et al. Measurement of patient safety: a systematic review of the reliability and validity of adverse event detection with record review. BMJ Open 2016;6:e011078 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zegers M, Hesselink G, Geense W, et al. Evidence-based interventions to reduce adverse events in hospitals: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2016;6:e012555 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hofer TP, Bernstein SJ, DeMonner S, et al. Discussion between reviewers does not improve reliability of peer review of hospital quality. Med Care 2000;38:152–61. 10.1097/00005650-200002000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Farup PG. Are measurements of patient safety culture and adverse events valid and reliable? Results from a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15 10.1186/s12913-015-0852-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mattsson TO, Knudsen JL, Lauritsen J, et al. Assessment of the global trigger tool to measure, monitor and evaluate patient safety in cancer patients: reliability concerns are raised. BMJ Qual Saf 2013;22:571–9. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Leistikow I. Aantonen patiëntveiligheid vergt acceptatie van breder wetenschapspalet. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2017;161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leistikow I, Mulder S, Vesseur J, et al. Learning from incidents in healthcare: the journey, not the arrival, matters. BMJ Qual Saf 2017;26:252–6. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vincent C, Amalberti R. Safety in healthcare is a moving target. BMJ Qual Saf 2015;24:539–40. 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ovretveit J. The contribution of new social science research to patient safety. Soc Sci Med 2009;69:1780–3. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Øvretveit J. Understanding and improving patient safety: the psychological, social and cultural dimensions. J Health Organ Manag 2009;23:581–96. 10.1108/14777260911001617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]