Abstract

Introduction:

Primary age-related tauopathy (PART) is a recently described entity that can cause cognitive impairment in the absence of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Here, we compared neuropathological features, tau haplotypes, apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotypes, and cognitive profiles in age-matched subjects with PART and AD pathology.

Methods:

Brain autopsies (n = 183) were conducted on participants 85 years and older from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging and Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center. Participants, normal at enrollment, were followed with periodic cognitive evaluations until death.

Results:

Compared with AD, PART subjects showed significantly slower rates of decline on measures of memory, language, and visuospatial performance. They also showed lower APOE ε4 allele frequency (4.1% vs. 17.6%, P = .0046).

Discussion:

Our observations suggest that PART is separate from AD and its distinction will be important for the clinical management of patients with cognitive impairment and for public health care planning.

Keywords: Primary Age-Related Tauopathy (PART), Alzheimer disease (AD), Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Aging, Dementia, Public Health Planning, Neurofibrillary tangles

1. Introduction

Humankind is in the midst of a longevity revolution that can be traced back to the 1830s [1]. Until the 1950s, much of this increased longevity resulted from declines in infant mortality, but in recent decades, more than 75% of the increase is attributable to years added at the end of life. Because the incidence and prevalence of dementia increase substantially after the age of 65 years [2], one consequence of this longevity revolution has been a striking increase in the number of cases of dementia [3].

Sixty years ago, Roth, Tomlinson, and Corsellis noted the universality of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) in autopsied brains of people older than 85 years, whether they had cognitive impairment or not [4]. This neurofibrillary degeneration has been designated a variety of names [5], most recently “primary age-related tauopathy” (PART), characterized by NFT and tau lesions in the absence of significant β amyloid (Aβ) plaques [6]. The lack of Aβ plaques distinguishes PART neuropathologically from Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [7].

In autopsy studies, PART occurs in 20–25% of individuals older than 90 years [5,8]. The clinical manifestations and cognitive function of individuals with PART are variable with conflicting reports in the current literature. Although some individuals demonstrate no impairment, others show mild cognitive impairment and others meet criteria for dementia [8–10]. To date, rigorous clinical pathological correlations of PART are lacking. NFT changes in PART are usually restricted to the medial temporal lobe, basal forebrain, brainstem, and olfactory areas (Braak stages 0-IV [11]) with a topography similar to cases of mild or intermediate AD pathological change [5]. The NFT in both disorders are identical, sharing both 3 repeat and 4 repeat tau isoforms and 22–25 nm paired helical filamentous ultrastructure [5,6,12]. Even so, the relationship between PART and AD remains unclear.

2. Methods

2.1. Neuropathology (see supplement for additional methods )

We examined 180 consecutive autopsy brains from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) [13–15] of participants aged ≥85 years. Three additional autopsy brains from the Johns Hopkins University Alzheimer Disease Research Center of subjects aged ≥85 years meeting criteria for PART [6] were also included. Among these 183 brains, we identified 42 PART and 130 AD cases. Eleven brains were excluded due to a pathologic diagnosis of neurodegeneration other than PART or AD. Both cohorts have similar autopsy assessments as previously described [13]. A semiquantitative assessment of frequency of neuritic plaques and NFT was made according to Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) criteria [7,16]. Staging of NFT was performed according to Braak [11,17]. Aβ deposition was assessed according to Thal [18]. Fig. 1 shows the histopathology and semiquantitative density of NFT in sparse, moderate, and frequent categories in both PART and AD cases.

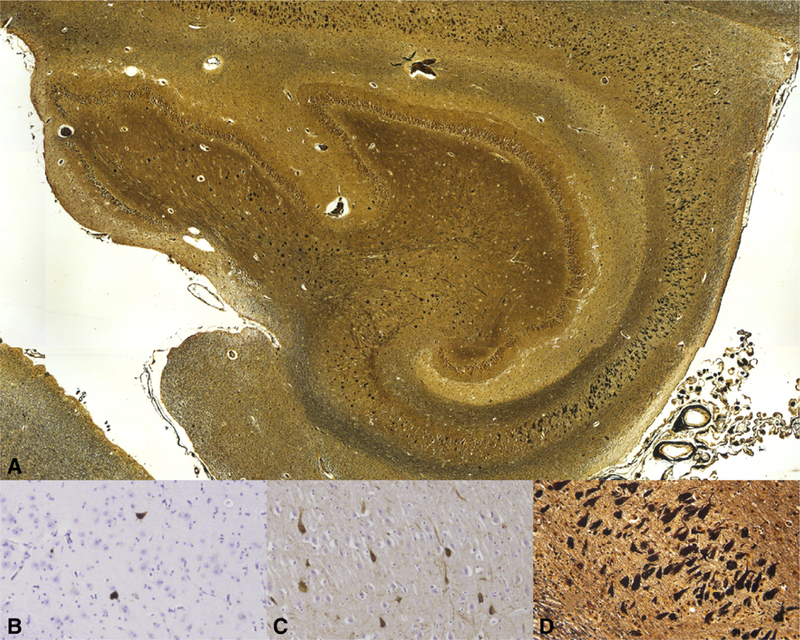

Fig. 1.

Histopathologic features of primary age-related tauopathy (PART). Low-power digitized scanning view micrograph of Hirano Silver-stained hippocampus of 102-year-old female with definite PART (image scanned at 100X) (A). Semiquantitative categorical scoring of neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) densities on PHF-1 immunohistochemistry and Hirano silver, 200 × showing sparse (B), moderate (C), and frequent (D) NFTs.

2.2. Definitions of PART and AD

Classification of PART and AD groups was based on neuropathological examination, independent of their clinical features.

2.2.1. PART

Brains with phosphorylated tau pathology in the form of NFT and/or pathologic neurites in the absence of Aβ neuritic plaques or with only foci of diffuse Aβ plaque morphology as proposed by Crary et. al [6]. PART cases are subdivided into “definite” (CERAD 0, Braak stage ≤ IV, Thai Aβ phase 0) with no Aβ deposition and “possible” (CERAD 0, Braak stage ≤ IV, Thai Aβ phase 1–2) with diffuse Aβ plaques.

2.2.2. AD

Brains containing Aβ deposition with Thai phase ≥1 and neuritic plaques at a frequency of ≥ A according to CERAD [16] with any NFT Braak stage [7,11,17].

PART brains were compared pathologically to 130 brains meeting National Institute on Aging/Alzheimer’s Association criteria for AD neuropathologic change [7].

All brains with pathological diagnoses of PART (N = 42) or AD (N = 130) were examined for tau and Aβ lesions in the cerebral cortex, basal ganglia, brainstem, and cerebellum. All PART participants and an age-matched subset of AD brains (N = 62) spanning neuritic plaque CERAD scores of A (N = 15), B (N = 31), and C (N = 16) were examined for TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) and α-synuclein lesions [19] using immunohistochemistry (Supplementary Table 1) and for vascular lesions. The 62 AD brains were selected with similar CERAD A, B, and C proportions to the entire AD (N = 130) group.

Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotypes [20] were obtained on 37 (88.0%) PART and 94 (71.8%) AD cases. Tau haplotypes [21] were obtained on 34 (81.0%) PART and 66 (50.1%) AD cases.

2.3. Clinical cohorts and cognitive assessment (see supplement for additional methods)

Subjects were enrolled in the BLSA or the Johns Hopkins University Alzheimer Disease Research Center Clinical Cohort and received a full cognitive battery (every two years and on the off year were assessed with a telephone version of the Short Blessed test [15] from 70 years until their 75th birthday). Participants 75 years and older received a full cognitive assessment (Supplementary Table 2) annually until they were untestable or expired. After death, subjects were adjudicated as having normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or dementia, including dementia subtype [22] at a consensus diagnostic meeting by study examiners who were unaware of the neuropathological diagnoses.

Data on cognitive performance were analyzed for a subset of PART (N = 34) and AD (N = 116) cases. We excluded 8 PART cases and 14 AD cases with severe vascular lesions sufficient to cause or contribute to cognitive impairment. The neuropsychological battery tapped a broad range of domains, including memory, executive function, language, visuospatial ability, attention, and global mental status performance.

3. Results (see supplement for details)

3.1. Neuropathology

Among 180 BLSA subjects, 39 (21.7%) met criteria for PART [6] and 130 (72.2%) met neuropathologic criteria for AD [7]. Adding the 3 PART cases from the Johns Hopkins University Alzheimer Disease Research Center provided a total of 42 PART cases. Among them, 38 (90.5%) had definite PART, and only 4 (9.5%) were identified as possible PART [6].

The density and distribution of NFT identified with phosphorylated tau immunohistochemistry in PART across multiple brain regions are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

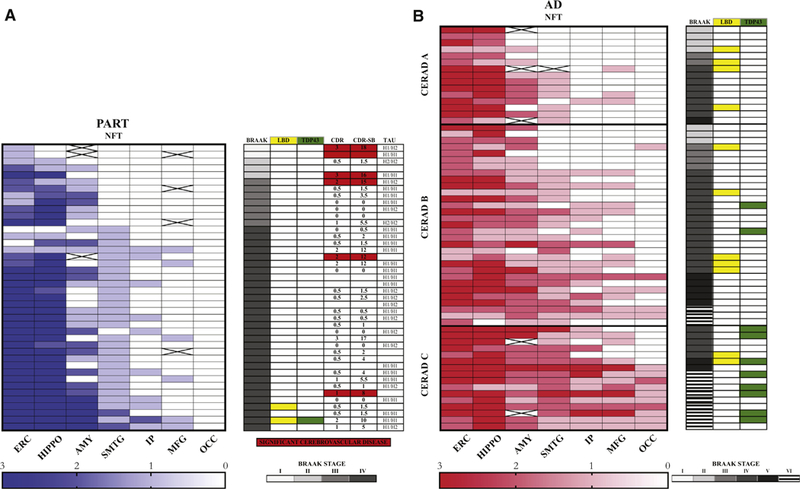

Fig. 2.

Comparison of primary age-related tauopathy (PART) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology and associated neurodegenerative features. Heatmaps showing the semiquantitative densities and distribution of neurofibrillarytangle (NFT) in 42 PART subjects (A—left [blue]) and 62 AD subjects (B—left [Red]). Each row represents a subject with PART or AD. Columns represent brain regions. The densities of NFT, that is, 0: none, 1: sparse, 2: moderate, 3: frequent, are color-coded according to the scales depicted in A-below and B-below. The Braak score, presence of associated Lewy body disease (yellow), and TDP-43 proteinopathy (green) in PART and AD are shown on A-right and B-right, respectively. Clinical dementia rating score (CDR) and Clinical dementia rating score sum of boxes (CDR-SB) and tau haplotypes (TAU) are shown in PART with vascular lesions sufficient to cause or contribute to cognitive impairment (red) or without (white) (A). The CERAD A, B, and C grouping of the AD cases corresponds to sparse, moderate, or frequent neuritic plaques [16] (white = none; X = not examined). Abbreviations: ERC, entorhinal cortex; HIPPO, hippocampus; AMY, amygdala, SMTG, superior and middle temporal gyri, IP, inferior parietal lobule; MFG, middle frontal gyrus; OCC, visual cortex (Brodmann’s areas 17 and 18); CERAD, Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease.

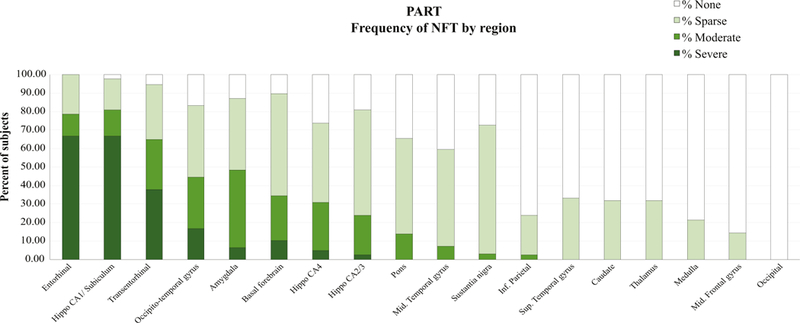

Fig. 3.

Regional distribution and density of neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) throughout the brain in PART (N = 42 subjects). In primary age-related tauopathy (PART), tau lesions in the form of NFTs show a distribution largely limited to the parahippocampal gyrus (entorhinal cortex, transentorhinal cortex, and medial occipitotemporal or fusiform gyrus), hippocampus, amygdala and basal forebrain, with less severe extension to the brainstem and other neocortical regions. The semiquantitative density [16] of NFT is color-coded and is most severe in medial temporal lobe structures.

Only one PART case showed nonphosphorylated TDP-43 histopathology (1 of 37, 2.7%), whereas 10 of 62 (16.1%) age-matched AD cases showed TDP-43 histopathology. The group difference in frequency of TDP-43 pathology did not reach significance (Fischer exact test, P = .066).

Lewy body pathology immunoreactive for α-synuclein [23] was observed in 2 PART subjects (4.8%, 2/42) and 11 age-matched AD subjects (17.7%, 11/62). The difference was not significant (Fisher’s exact test, P = .070).

The APOE ε4 allele frequency in PART was 4.0% and 17.5% in AD (Fisher’s exact, P = .0028), a significant difference. The frequency of the APOE ε2 allele was 12.2% in PART and 5.3% in AD; the difference was not significant (Fisher’s exact, P = .066) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of primary age-related tauopathy, Alzheimer’s disease, and the United States Caucasian population APOE genotypes and allelic distribution

| APOE genotypes and allele frequencies from the BLSA and JHU-ADRC | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| PART(N = 37) |

AD (N = 94) |

*Healthy United States Caucasian population(N = 428) |

|

| Genotype | Percentage | Percentage | Percentage |

| APOE 2/2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| APOE 2/3 | 21.6 | 10.6 | 13 |

| APOE 3/3 | 70.3 | 58.5 | 63 |

| APOE 2/4 | 2.7 | 0 | 13 |

| APOE 3/4 | 5.4 | 26.6 | 21 |

| APOE 4/4 | 0 | 4.3 | 1 |

| Allele | |||

| ε2 | 12.2† | 5.3† | 7 (N = 30) |

| ε3 | 83.8 | 77.1 | 80.4 (N = 344) |

| ε4 | 4‡ | 17.5‡ | 12.6 (N = 54) |

Abbreviations: APOE, apolipoprotein E; AD, Alzheimer’s disease; PART, primary age-related tauopathy; BLSA, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging; JHU-ADRC, Johns Hopkins Alzheimer’s Disease Research center.

NOTE. APOE genotypes and allelic distribution frequencies from the BLSA and JHU-ADRC comparing PART to AD subjects are shown on the left and the healthy United States Caucasian population is shown on the right [24].

Only subsets of subjects were genotyped[25].

(Fisher exact, p = .066).

(Fisher exact, p = .0028).

The frequencies of vascular lesions and tau haplotypes between PART and AD showed no difference (Fisher’s exact test, P = .69 and P = .62, respectively).

3.2. Cognitive assessment

Consensus diagnosis of cognitive impairment was formulated in 16 of 34 cases with PART (47%) versus 90 of 111 (81%) cases with AD pathology P=.0009]. Mean age of onset of cognitive impairment in PART was 88.4 (SD = 4.9) and 86.8 years (SD = 5.6) in AD (t(df = 104) = –1.09, P = .28). Descriptive data for the two samples are in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. Cognitive performance at the baseline is shown in Supplementary Table 5 and performance at last visit and change over time are shown in Supplementary Table 6. Baseline cognitive measure is defined as the first assessment of cognitive performance (before impairment). At the baseline, there were no differences in cognitive performance between the two groups.

At the last visit, AD participants performed worse compared with PART participants in memory (P = .015, .61 SD lower) and trended toward worse performance in language (P = .094, .32 SD lower) and global mental status (P = .084, 1.1 points lower). The mean interval between last cognitive evaluation and death was 8.7 ± 6.7 months for all subjects.

AD participants declined significantly in all 5 domains tested and mental status (Mini-Mental State Examination) (P < .0001 in all cases), while participants with PART declined significantly only in executive function and language (P = .0026; P < .0001, respectively).

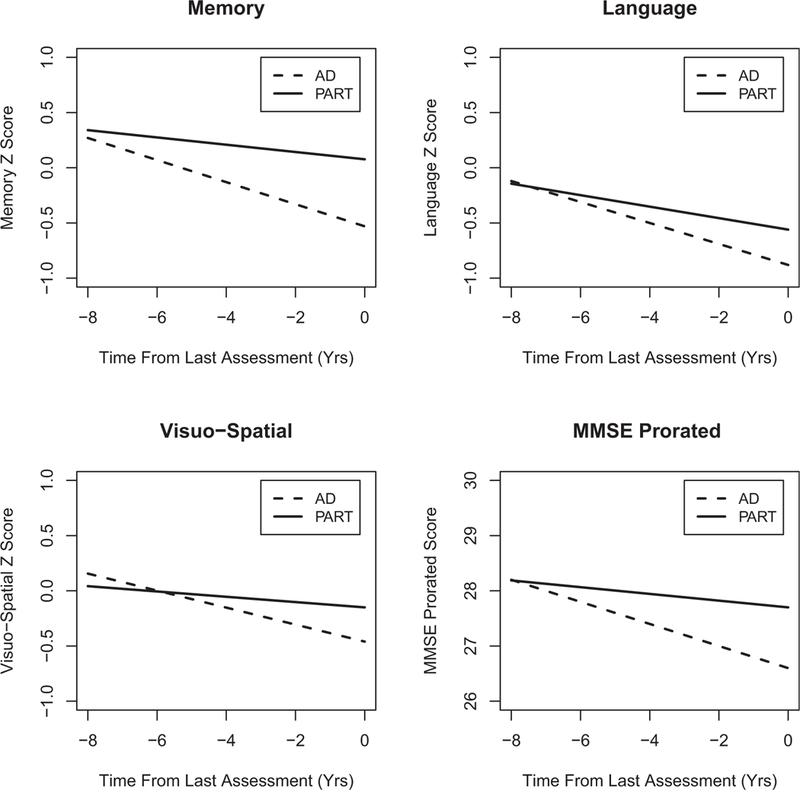

Importantly, AD subjects showed significantly greater rates of longitudinal decline than PART subjects in memory (0.070 SD/per year, P = .0034), language (0.044 SD/per year, P = .0019), visuospatial ability (0.053 SD/per year, P = .0051), and Mini-Mental State Examination (0.14 points/per year, P = .016) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of longitudinal rates of change of cognitive performance in 5 domains. Longitudinal rates of cognitive performance change examined in 5 domains (Memory, Attention, Executive Function, Language, and Visuospatial Ability) and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) were found to show a highly significant difference between subjects with primary age-related tauopathy (PART) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology in memory, language, visuospatial ability, and MMSE raw score (prorated for visual impairment) (P = .0034, P = .0019, P = .0051, and P = .016, respectively). In all these domains, AD subjects showed a faster rate of decline than PART subjects. No difference in longitudinal rates of cognitive performance was seen in attention and executive function domains (P = .33, P = .32, respectively).

3.3. Clinical pathologic correlation

Analysis of semiquantitative NFT densities [16] in PART cases, examining regional densities across all brain and brainstem regions in relation to the last Clinical dementia rating (CDR) evaluation revealed a significant correlation between the presence of NFT in the middle frontal gyrus and higher CDR (Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel Correlation, P = .0037), whereas all other regions examined showed no significant correlation (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

4. Discussion

Results from this study support the hypothesis that PART and AD are distinct nosological entities. The finding that 22% of autopsied subjects older than 85 years in the BLSA meet neuropathological criteria for PART confirms several recent reports demonstrating a high prevalence of tau-related pathology and absence of Ab pathology in a substantial proportion of very old individuals [5,6]. On final clinical assessment, nearly half (47%) of individuals with PART were adjudicated to have cognitive impairment by study examiners blinded to their neuropathologic diagnosis. These data emphasize the need for clarification of the contribution of non-AD pathology to cognitive status in late life, given the rapid growth of this segment of the population.

4.1. PART and AD

The neuropathologic results presented here provide evidence that PART and AD are distinct pathological entities (Fig. 2) and that PART can cause cognitive impairment independently of Aβ deposition [26]. In addition to differences in the stages of neurofibrillary degeneration, PART differs from AD in a lower frequency of ApoE 4, and lower frequency of Lewy bodies and TDP-43 changes. These differences have been previously reported by Josephs et al. [25]. In PART, tau lesions, that is, NFT and neuropil threads, had a distribution limited to the parahippocampal gyrus, hippocampus, amygdala, and basal forebrain, with less severe extension to the brainstem and a few neocortical regions (Fig. 3). We also noted that tau neocortical involvement was seen in a minority of PART cases, most of which exhibited sparse density, consistent with other pathologic studies of PART [5,6]. Our study showed over 60% of definite PART subjects to be Braak stage IV, whereas other series report 5–25 % of definite PART cases to be Braak IV stage or greater [6,25,26]. One possible explanation for this difference is the tissue sampling scheme we used; most of our cases were examined using whole-mount brain sections of the temporal and frontal lobes in addition to smaller standard size block sampling for Braak staging. Furthermore, we included any sampled cortical region with one or more NFT to increase to Braak stage IV; therefore, our threshold for NFTs staging may have been lower than for other studies.

TDP-43 proteinopathy, reported in 30–70% of subjects with pathological AD in prior case series [27], was identified only in a single individual with PART (2.7 %) and present in 16.1% of AD cases in our series. TDP-43 pathology appears as a distinctive feature between these conditions. The lack of significant difference in our study is likely due to the low numbers of subjects in both groups. Our study examined for TDP-43 histopathology using antibody against the native, nonphosphorylated protein, thus ensuring complete visualization of protein localization (i.e. abnormal cytoplasmic aggregation and loss of nuclear localization). Josephs et al. [25] reported 29% frequency of TDP-43 proteinopathy in definite PART subjects; however, this study included a number of subjects with a primary pathologic diagnosis of hippocampal sclerosis [28] and argyrophilic grain disease, which were not included in our study. We did not include cases with primary diagnosis of hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a pathologic terminology focusing on TDP-43 proteinopathy included in frontotemporal lobar degeneration, more precisely redefined as Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 with Sclerosis by Nelson PR et al. [29]. Although our series did include two cases with features of hippocampal sclerosis, these cases included neurofibrillary degeneration as the primary diagnostic feature without the presence of TDP-43 proteinopathy. Although we sampled the left hippocampus only in both of these cases and therefore we cannot rule out TDP-43 proteinopathy occurring in the contralateral hippocampus as previously reported by Nelson PR et al. [30], Elobeid et al. [31]. reported a higher frequency of TDP-43 lesions in PART, which may be explained by other anatomical regions examined and the use of a different antibody. In addition, we did not include subjects who were identified to have argyrophilic grains, a finding that has been reported at a frequency of 16–22% in elderly persons with normal cognitive function [36]. Although previous studies have reported an association of argyrophilic grains with TDP-43 proteinopathy in elderly subjects [32], more recent studies of aged individuals with Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 with Sclerosis were not correlated with argyrophilic grains [33]. As Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 with Sclerosis and argyrophilic grain pathology are described to have a different distribution of tau pathology than that seen in classic AD or PART [33] in which Braak NFT staging is used [38], we excluded these cases from our series.

Furthermore, the low proportion of AD individuals with TDP-43 pathologic inclusions may reflect the low proportion of highest CERAD (CERAD C) and Braak (Braak Vor VI) scores among the evaluated AD cases (Fig. 2). Lewy body pathology was less prevalent in PART than AD (4.8% vs. 17.8%), also showing a trend toward differences between these conditions. The lack of statistical difference may be attributed to the small numbers of observed cases in our study. The prevalence of vascular disease in the AD and PART groups also did not differ significantly.

The finding that the APOE ε4 allele is underrepresented and APOE ε2 overrepresented in PART compared to AD is consistent with previous reports [6]. Interestingly, the 12.2% APOE ε2 allele frequency in PART is substantially higher than the 7% in the United States Caucasian population [24]. Because APOE has a crucial role in cholesterol transport in the brain [35], it is plausible that the different ε4/ε2 ratio between the two groups relates to either different rates of amyloidogenesis [35,36] or Aβ clearance [36] and may contribute to the lack of Aβ pathology in PART. In addition, we and others have shown that the APOE ε4 allele is associated with an earlier onset of amyloid accumulation [37]. The difference in APOE allele frequency between PART and AD supports the conclusion that they are biologically distinct (Table 1). Conversely, tau haplotypes were found to be similar in PART and AD. These results differ from a previous study by Santa Maria et al. [12] but may be explained by the use of different neuropathologic criteria. In the present study, we included all individuals with any tau pathology in the absence of Aβ neuritic plaques, whereas the study by Santa Maria et al. included PART cases with tau lesions limited to Braak regions III-IV, while designating those with tau lesions restricted to Braak 0-II as control subjects. The lack of widespread tau lesions in the neocortex in PART, in contrast to that observed in AD, suggests that Aβ pathology is necessary for significant neocortical tau deposition as suggested by others [38,39].

There were also several differences between the PART and AD groups on neurocognitive performance (Fig. 4). The findings that AD participants had more severe memory impairment and more rapid memory decline than PART participants might be explained by more extensive pathology in the AD group, but tau pathology in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus was extensive in both AD and PART. Previous studies have shown that stereologic measures of NFT and neuronal cell loss in the entorhinal cortex, area 9, and hippocampal CA1 regions correlate with cognitive impairment in AD; however, regional volumes of Aβ do not [40]. In addition, among AD subjects, those identified as having TDP-43 pathologic lesions have been shown to have significantly worse cognitive impairment, with memory dysfunction and significantly more severe hippocampal atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging [27,41]. The low frequency of TDP-43 pathologic inclusions in PART subjects might also explain their less-severe memory impairment. AD subjects also exhibited a greater rate of decline in the visuospatial domain compared with PART subjects, suggesting greater involvement of the parietal and occipital cortices in AD.

Correlative analyses in our study examining the distribution and density of NFT in brain regions of PART subjects compared to last visit CDR performance revealed a strong correlation of NFT in the frontal cortex and a CDR score ≥ 1. These data indicate that the extension of tau lesions beyond the medial temporal lobe into the frontal cortex may account for the clinical progression. These findings are consistent with the observations of Giannakopoulos et al. [40] in AD, in which densities of NFT and regional neuronal loss in the frontal cortex, measured stereologically, were correlated with cognitive decline. Our correlation may have implications for PART staging schema but need to be interpreted with caution due to the relatively small number of subjects examined.

Similarities between PART and AD include the observation that phosphorylated tau lesions have the same topographic distribution in PART and early AD [11,34]. This could argue in favor of PART being an early-stage manifestation of AD and that progression of tau pathology requires the later extension of Aβ pathology. However, Braak et al. [42] have reported that among individuals reaching 90–100 years of age, about 80% develop Aβ pathology but 20% do not, although Neltner et al. [43] reported that 21% of centenarians had no Aβ plaques, whereas 100% had NFTs. These observations are consistent with ours and reinforce the notion that a proportion of the population ≥85 years does not develop Aβ deposition and that PART will not progress to AD.

4.2. PART and SNAP

There are several congruencies between PART and individuals with “suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology” [44,45] who have imaging/biomarker evidence of neurodegeneration without amyloidosis. These similarities include association with normal cognition or mild cognitive impairment, neurodegeneration of mesial temporal lobe structures, absence of Aβ deposits, and underrepresentation of APOE ε4 allele relative to AD. Tau PET scanning [46] in conjunction with other imaging, for example, amyloid and vascular imaging, should allow for further delineation of the overlap of PART as a subset of suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology.

4.3. PART and “normal aging”

Tau lesions of the medial temporal lobe are not limited to older individuals but have also been reported in the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus before 30 years of age [42]. Thus, it is possible that these early tau lesions are indicative of an age-associated neurodegeneration and that PART may represent the continued development of these lesions in some individuals.

Although PART may affect only approximately 22% of the population older than 85 years, the absolute number of individuals in this age group in the United States was ~5.5 million (1.8% of the population) in 2010 and will reach ~ 18 million (4.5%) by 2050. This suggests that by 2050 [47], almost 4 million people in the United States will develop PART, and if approximately half develop cognitive impairment, PART will become a major contributor to disability, even if its clinical course is more benign than AD. Therefore, PART has important implications for public health planning. Moreover, biomarkers that differentiate preclinical AD from PART will be important for prognosis and possible institution of anti-Aβ therapy or other treatments for preventing progression to AD. Further research into the biology of tau-related neurodegeneration independent of AD is warranted.

Supplementary Material

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Systematic Review: The authors searched PubMed for all publications related to delineation of neuropathologic, genetic, and cognitive changes in primary age-related tauopathy (PART) in old individuals. Although some neuropathologic features of PART have recently been defined, detailed specifics of neuropathology, genetic differences, and rates of cognitive change in relation to Alzheimer’s disease have not previously been examined.

Interpretation: In this longitudinal study of participants older than 85 years who came to autopsy, 23% met pathologic criteria for PART [1] and 71% for AD [2]. Rates of longitudinal cognitive decline were significantly greater in AD compared to PART in memory, language, visuospatial ability, and mental status; although tau haplotypes were similar, allele frequencies of APOE ε4 were significantly different.

Future Directions: Forthcoming studies are necessary to clinically define PART, as distinct from AD, to better understand the neurobiology of aging, for clinical management of patients with dementia, and for public health care planning.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Ms. Karen Fisher for helpful preparation of the article. All authors are indebted to the BLSA and JHU-ADRC participants, their families, and NIA and JHU staff.

This work is supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, NIH and the Johns Hopkins University Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (NIA AG05146).

PVR received nonfinancial/financial support from Hall Family Foundation, S.I. Newhouse Foundation and royalties from Book royalties from The 36-Hour Day, Practical Dementia Care, and The Why of Things. JCT is supported by the BrightFocus Foundation and NIH Grant R21AGO55844. OP is supported by the BrightFocus Foundation and the S.I. Newhouse Foundation. WRB,is supported by the S. I. Newhouse Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/joalz.2018.07.215.

References

- [1].Christensen K, Doblhammer G, Rau R, Vaupel JW. Ageing populations: the challenges ahead. Lancet 2009;374:1196–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chene G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S. Incidence of Dementia over Three Decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 2016;374:523–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement 2013;9:63–75.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Tomlinson BE, Blessed G, Roth M. Observations on the brains of non-demented old people. J Neurol Sci 1968;7:331–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Jellinger KA, Alafuzoff I, Attems J, Beach TG, Cairns NJ, Crary JF, et al. PART, a distinct tauopathy, different from classical sporadic Alzheimer disease. Acta neuropathologica 2015;129:757–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I, et al. Primary age-related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta neuropathologica 2014;128:755–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, et al. National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012;8:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Jellinger KA, Bancher C. Senile dementia with tangles (tangle predominant form of senile dementia). Brain Pathol 1998;8:367–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Nelson PT, Abner EL, Schmitt FA, Kryscio RJ, Jicha GA, Santacruz K, et al. Brains with medial temporal lobe neurofibrillary tangles but no neuritic amyloid plaques are a diagnostic dilemma but may have pathogenetic aspects distinct from Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2009;68:774–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Jefferson-George KS, Wolk DA, Lee EB, McMillan CT. Cognitive decline associated with pathological burden in primary age-related tauopathy. Alzheimers Dement 2017;13:1048–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta neuropathologica 1991;82:239–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Santa-Maria I, Haggiagi A, Liu X, Wasserscheid J, Nelson PT, Dewar K, et al. The MAPT H1 haplotype is associated with tangle-predominant dementia. Acta neuropathologica 2012; 124:693–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L, Crain BJ, Pletnikova O, et al. Neuropathologic studies of the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA). J Alzheimer’s Dis 2009; 18:665–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Driscoll I, Resnick SM, Troncoso JC, An Y, O’Brien R, Zonderman AB. Impact of Alzheimer’s pathology on cognitive trajectories in nondemented elderly. Ann Neurol 2006;60:688–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Troncoso JC, Martin LJ, Dal Forno G, Kawas CH. Neuropathology in controls and demented subjects from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neurobiol Aging 1996;17:365–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1991;41:479–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta neuropathologica 2006;112:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002;58:1791–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, Emre M, O’Brien JT, Feldman H, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Hixson JE, Vernier DT. Restriction isotyping of human apolipoprotein E by gene amplification and cleavage with HhaI. J lipid Res 1990; 31:545–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Baker M, Litvan I, Houlden H, Adamson J, Dickson D, Perez-Tur J, et al. Association of an extended haplotype in the tau gene with progressive supranuclear palsy. Hum Mol Genet 1999;8:711–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Baborie A, Sampathu DM, Du Plessis D, Jaros E, et al. A harmonized classification system for FTLD-TDP pathology. Acta neuropathologica 2011;122:111–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Tang MX, Stern Y, Marder K, Bell K, Gurland B, Lantigua R, et al. The APOE-epsilon4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer disease among African Americans, whites, and Hispanics. JAMA 1998;279:751–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Josephs KA, Murray ME, Tosakulwong N, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, Machulda MM, et al. Tau aggregation influences cognition and hippocampal atrophy in the absence of beta-amyloid: a clinico-imaging-pathological study of primary age-related tauopathy (PART). Acta neuropathologica 2017;133:705–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Besser LM, Crary JF, Mock C, Kukull WA. Comparison of symptomatic and asymptomatic persons with primary age-related tauopathy. Neurology 2017;89:1707–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Petrucelli L, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer’s disease staging scheme. Acta neuropathologica 2016;131:571–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta neuropathologica 2013;126:161–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Nelson PT, Trojanowski JQ, Abner EL, Al-Janabi OM, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, et al. “New Old Pathologies”: AD, PART, and Cerebral Age-Related TDP-43 With Sclerosis (CARTS). J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016;75:482–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Nelson PT, Schmitt FA, Lin Y, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Patel E, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis in advanced age: clinical and pathological features. Brain 2011;134:1506–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Elobeid A, Libard S, Leino M, Popova SN, Alafuzoff I. Altered Proteins in the Aging Brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2016;75:316–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Arnold SJ, Dugger BN, Beach TG. TDP-43 deposition in prospectively followed, cognitively normal elderly individuals: correlation with argyrophilic grains but not other concomitant pathologies. Acta neuropathologica 2013;126:51–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Smith VD, Bachstetter AD, Ighodaro E, Roberts K, Abner EL, Fardo DW, et al. Overlapping but distinct TDP-43 and tau pathologic patterns in aged hippocampi. Brain Pathol 2018;28:264–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Braak H, Braak E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol Aging 1995;16:271–8. discussion 8–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Ladu MJ, Reardon C, Van Eldik L, Fagan AM, Bu G, Holtzman D, et al. Lipoproteins in the central nervous system. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2000;903:167–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol 2013; 9:106–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Bilgel M, An Y, Zhou Y, Wong DF, Prince JL, Ferrucci L, et al. Individual estimates of age at detectable amyloid onset for risk factor assessment. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:373–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sperling R, Mormino E, Johnson K. The evolution of preclinical Alzheimer’s disease: implications for prevention trials. Neuron 2014; 84:608–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Jagust WJ, Mormino EC. Lifespan brain activity, beta-amyloid, and Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Cognitive Sciences 2011;15:520–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bussiere T, Bouras C, Kovari E, Perl DP, et al. Tangle and neuron numbers, but not amyloid load, predict cognitive status in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 2003; 60:1495–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Weigand SD, Murray ME, Tosakulwong N, Liesinger AM, et al. TDP-43 is a key player in the clinical features associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Acta neuropathologica 2014; 127:811–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Braak H, Thal DR, Ghebremedhin E, Del Tredici K. Stages of the pathologic process in Alzheimer disease: age categories from 1 to 100 years. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2011;70:960–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Neltner JH, Abner EL, Jicha GA, Schmitt FA, Patel E, Poon LW, et al. Brain pathologies in extreme old age. Neurobiol Aging 2016;37:1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Jack CR Jr, Knopman DS, Weigand SD, Wiste HJ, Vemuri P, Lowe V, et al. An operational approach to National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association criteria for preclinical Alzheimer disease. Ann Neurol 2012;71:765–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Jack CR Jr. PART and SNAP. Acta neuropathologica 2014;128:773–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Villemagne VL, Okamura N. Tau imaging in the study of ageing, Alzheimer’s disease, and other neurodegenerative conditions. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2016;36:43–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].West LA, Cole S, Goodkind D, He W. 65+ in the United States: 2010, Special Studies, Current Population Reports; 2014;. p. 23–212. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.